Translate this page into:

Phytogenic-mediated silver nanoparticles using Persicaria hydropiper extracts and its catalytic activity against multidrug resistant bacteria

⁎Corresponding authors at: Department of Physics, College of Science, Qassim University, Buraydah 51452, Saudi Arabia(Aiyeshah Alhodaib), Department of Microbiology, Kohat University of Science and Technology (KUST), Kohat, 26000, Pakistan(Abdul Rehman). ahdieb@qu.edu.sa (Aiyeshah Alhodaib), abdulrehman@kust.edu.pk (Abdul Rehman)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Multidrug resistance (MDR) is one of the major global threats of this century. So new innovative approaches are needed for the development of existing antibiotics to limit antibacterial resistance. The current study was aimed to utilize extracts of root, stem, and leaves of Persicaria hydropiper for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using standard procedure. Synthesis of AgNPs was evident from the change in color of the solution to dark brownish and then it was further revealed by UV–Vis and Fourier Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR). UV–Vis spectroscopy has revealed absorbance peak at 370 nm while, FTIR spectrum displayed that aromatics amines were used as reducing agent in the fabrication of AgNPs. In addition, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM micrograph) displaying tetrahedron, spherical and oval shapes of synthesized AgNPs whereas, average size of synthesized AgNPs was found in the range of 32–77 nm. Beside this, it was also observed that the potency of antibiotics against MDR bacteria increased after coating with synthesized AgNPs i.e., the potency of Ceftazidime and Ciprofloxacin increased up to 450% and 500% against Bacillus respectively while, the potency of Gentamicin, Vancomycin and Linezolid increased up to 150%, 200% and 58% against Bacillus, Staphylococcus, and Proteus species respectively. Furthermore, it was concluded that utilizing AgNPs in combination with commercially available antibiotics would provide an alternate therapy for the treatment of infectious diseases caused by MDR bacteria.

Keywords

Persicaria hydropiper extracts

Silver nanoparticles

FTIR

SEM

Antimicrobial activity

Multidrug resistant bacteria

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology or nanoscale technology is the field of material science which deals in the synthesis of particles having size below 100 nm. Moreover, these particles have different chemical properties that’s why they have been extensively used in different fields such as optics, mechanics, photo electrochemical sciences, medical sciences, chemical industry, catalysis, drug-gene delivery, energy sciences, electronics and nonlinear optical sciences (Quintanilla-Carvajal et al., 2010). Silver (Ag) is an inorganic compound, available in powder form and under normal condition is insoluble in water. It is extensively used in the formulation of different products such as pigments ceramics, lubricants, adhesives tapes, ointment and batteries (Bharadwaj et al., 2021). Furthermore, silver is a non-toxic and biocompatible semiconductor used in the biological fields i.e., nano-medicine due to their extensive antimicrobial properties (Parveen et al., 2012; Xu, 2020).

Different methods such as chemical, physical, and biological methods are available now-a days to prepare nanoparticles. Chemical and physical methods are effective with respect to time and production rate. However, in chemical methods, different chemicals are used in the production process that may leads to the formation of toxic by-product and hence increase nanoparticles recovery and purification cost. On the other hand, physical methods are highly expensive due to use of energetic radiations that may leads to changes in the physicochemical property of nanoparticles (Viorica et al., 2017). On the other hand, biological methods are safe and cost effective as compared to chemical and physical methods (Xu, 2020). Biological synthesis or green synthesis used naturally occurring reducing agent such as plant extract, microorganisms (yeast, fungi, and bacteria) and biological particles like enzyme, protein, peptides, polysaccharide etc. In literature, different bacterial strains such as Lactococcus lactis (LCLB56-AgNCs) and actinobacteria strain (CGG11n) were reported as cost effective and novel reducing agents for the synthesis of AgNPs (Railean‐Plugaru et al., 2016; Viorica et al., 2017).

During biological synthesis of nanoparticles, different factors are needed to be considered and these include cell culture maintenance, intracellular synthesis, and multi-purification steps. Bioinspired green synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using plants has become a reliable method (Bharadwaj et al., 2021). Plants provide eco-friendly, safe, and beneficial approach for the synthesis of nanoparticle because plants are easily accessible to produce nanoparticles on large scale. In additions, the rate of production is faster as compared to other biological models like algae, fungi, and bacteria (Gurunathan et al., 2015).

Wide varieties of antibiotics are available in market for the treatment of infectious diseases and among them the local branded antibiotics have low potency towards pathogenic microorganisms. Therefore, usage of such antibiotics may lead to antibiotic resistance phenomenon (Gurskis et al., 2010). The bacterial plasmid showed role in the development of antibiotic’s resistance. In 1970 s, antibiotic’s resistance phenomenon was observed only in Enterobacteriaceae family such as Klebsiella pneumonae and Escherichia coli (Horan et al., 2008). It is now observed that most of the organisms which initially didn’t showed resistance to antibiotics, are now become resistance strains e.g., Klebsiella pneumonae and Escherichia coli caused infection in colonization with other pathogenic organisms within hospitalized patients and showed resistance to antibiotics (Akova, 2016).

Persicaria hydropiper is an annual plant of 40–70 cm tall which belongs to the family of Polygonaceae. It is distributed in Asia, Europe, Northern Africa, and Australia (Huq et al., 2014). The plant generally grows in wet areas at water sides in marshes and is usually predominant in agricultural fields. It is also commonly distributed to high land sites with highly organic, moist, or salty areas (Miyazawa and Tamura, 2007). P. hydropiper also has a wide range of traditional uses for medicinal purposes. In Europe, the plant has been used as diuretic and regulates menstrual irregularities (Ayaz et al., 2020). In addition, the whole plant either alone or mixed with other medicinal plants, is also given for menstrual bleeding, hypersensitivity, and hemorrhoids. Several reports on pharmacological properties of P. hydropiper are available to support the ethno-medicinal uses of the plant including antimicrobial, antifungal, anti-parasitic, anti-inflammatory, anti-fertility, anti-cholinesterase, and toxicological effects (Huq et al., 2014).

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) synthesized from the root, stem and leaves extracts of plants has also proven to be used as antimicrobial agent against number of bacterial species (Ahmed et al., 2016; Hernández-Morales et al., 2019). It has also been reported that AgNPs have strong antimicrobial properties against variety of microorganisms as they are small so they can easily penetrate into the cell and destroy synthesis machinery within cell and ultimately caused death of the target organisms (Xu, 2020: Nieto-Maldonado et al., 2022). In addition to this, AgNPs are also used in combination with other pharmaceutical products especially antibiotics to catalyze or enhance their activity against MDR bacterial species (Bankar et al., 2010; Dos Santos et al., 2014: Caloca et al., 2017).

The aim of the current study was to utilize the P. hydropiper root, stem, and leaves extracts for the synthesis of AgNPs and then determined its bio-catalytic potential to enhance the activity of commercially available antibiotics against multi drug resistance (MDR) bacterial species. As reported, extracts of P. hydropiper contained many compounds like flavonoids such as epicatechin, hyperin, isoquercitrin, isorhamnetin, kaempferol, quercetin, quercetrin, rhemnazin and rutein, which had strong antibacterial activity against bacterial species (Hawrył and Waksmundzka-Hajnos, 2011; Khurana et al., 2014). As the phenomenon of multi drug resistance increases day by day, therefore by utilizing AgNPs (fabricated from P. hydropiper extracts) in combination with commercially available antibiotics will provide an alternate therapy for the treatment of bacterial infections caused by MDR bacterial species.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bacterial isolates

In the current study, a total of 6 previously identified bacterial isolates were taken from Khyber Teaching Hospital (KTH), Peshawar, Pakistan. These bacterial species were confirmed in the Microbiology Laboratory, Abasyn University Peshawar. Among them, 03 were Gram positive bacterial isolates i.e., Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp. and Bacillus spp. while 03 were Gram negative bacterial isolates i.e., Pseudomonas spp., Escherichia spp. and Proteus spp.

2.2 Plant collection and identification

The plant species P. hydropiper were collected from district Dir Lower, Malakand Division, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. The plant was identified taxonomically at the Department of Botany, University of Peshawar, Pakistan. A voucher (HUP-3765) of plant was submitted at the Herbarium section, Department of Botany for future reference. The samples were cleaned by removing the dust particles and unwanted materials.

2.3 Drying, grinding and solvent extraction

The plants were spread on newspapers and were kept for shade drying for about one month at room temperature under dust free condition. During this process, the plant samples were turned over time to time. Dried leaves, stem and roots were grinded into fine powder through electrical grinder (Model: FOSS cyclotec 1093, Sweden) (Ahmad et al., 2011). The powdered plant materials were macerated in methanol for 14 days and this process was repeated twice. The solvent was then evaporated by rotary evaporator (Pars Azma Co., type: IN07) at a speed of 150 rpm for 24 h to collect the crude extracts (Aiyelaagbe and Osamudiamen, 2009). The powder was then stored in dark condition at room temperature (25 °C) to prevent the decomposition of extract by light and heat.

2.4 Synthesis and characterization of AgNPs

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) were synthesized by adding 1 ml P. hydropiper crude extract into 10 ml of aqueous solution of silver nitrate using 3 different tubes. These tubes were heated in water bath at 45 °C and then kept for mixing in a rotary shaker (Model: China Hz-300 Laboratory Rotary Shaker) at 37 °C providing speed of 150 rpm for 24 h. Reductions of AgNO3 to silver ions were confirmed by changing in color from yellowish to reddish brown indicated the formation of AgNPS. The reduced solution was filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper and then centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 30 min in a centrifuge (Model: Vision/VS-35SMTi, Korea, Rotor: Bio-Hazard Safety Rotor - Duralumin). The supernatant solution was discarded, and the pellet was obtained from the bottom of the tubes and was then dispersed in distilled water. This process was repeated 3 times to wash of any absorbed substance on the surface of the AgNPS. The solution was then stored at 4 °C in a glass container raped by aluminum foil to prevent day-light effects. These synthesized AgNPs were further subjected to UV–Visible spectroscopy, FTIR analysis and SEM analysis for their characterization.

2.4.1 UV–Visible spectrophotometric study

The UV–Vis spectrophotometric analysis was performed by using PerkinElmer spectrophotometer (UV/Visible-Lambda 45 model, USA) to measure the absorbance of AgNPS synthesized from the leaves, stem, and roots of P. hydropiper at the wavelength range of 200–700 nm. Deionized water was used for dilution of AgNPs solution at the ratio of 1:1. Furthermore, the tubes containing AgNPs solution were kept in UV–Visible spectrophotometer and data were recorded.

2.4.2 Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

The Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) was performed at the Pakistan Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (PCSIR) Laboratory, Peshawar, Pakistan. Each sample contains AgNPs, and extracts were individually freeze dried and the powder was then subjected for analysis using the PerkinElmer FTIR spectrometer (GX Model, USA). The different peaks were examined for the determination of various functional groups by FTIR spectrometer following KBr pellet method.

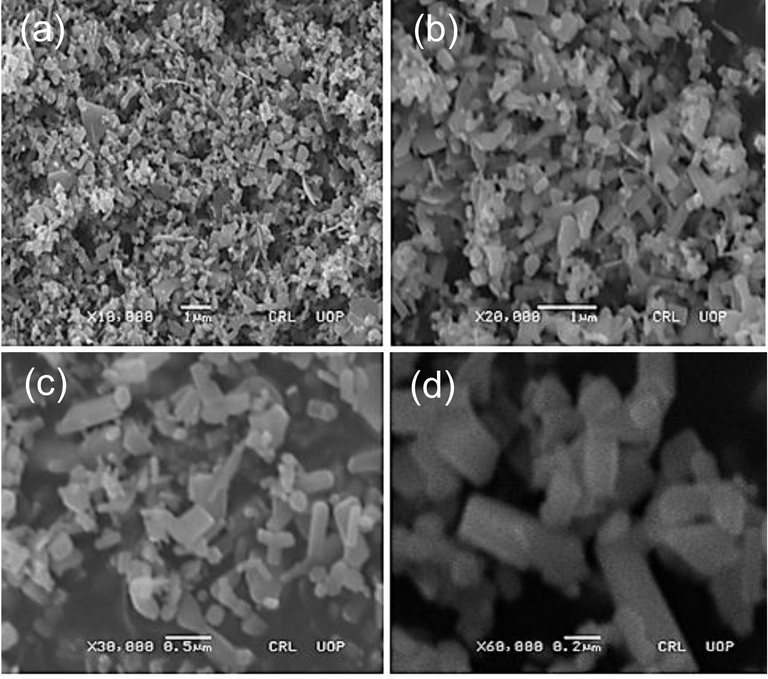

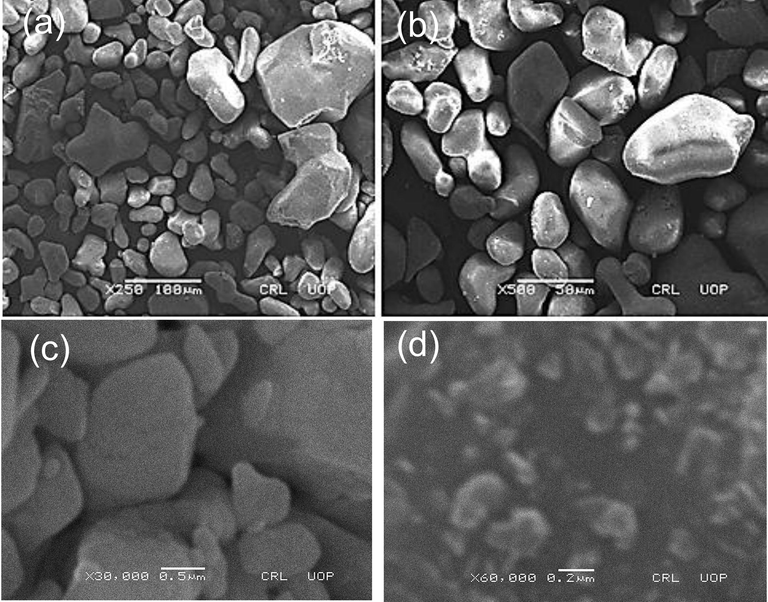

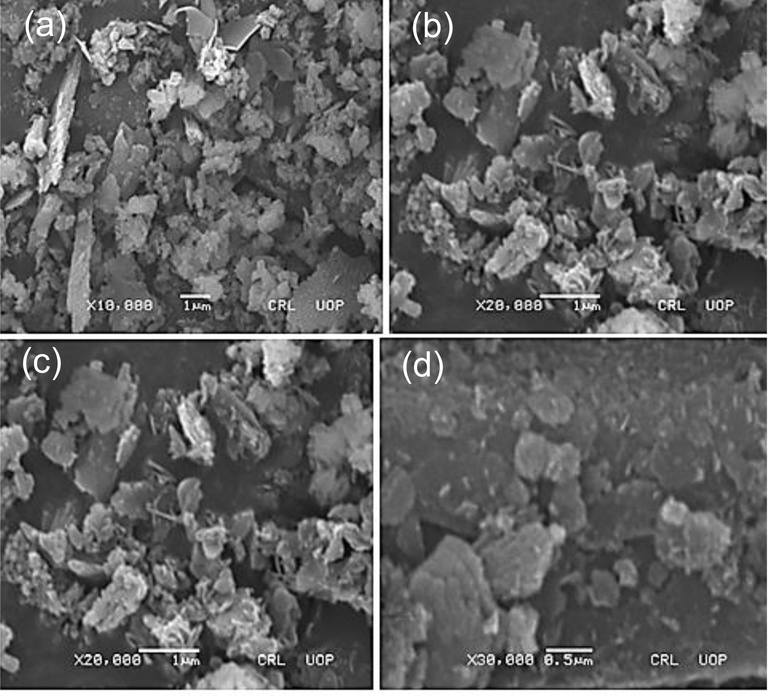

2.4.3 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

To specify the size and morphology of AgNPs, the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to obtain microscopic images of synthesized AgNPs at high resolution and at different magnifications ranging from X250, X500, X30,000, and X60,000. For this purpose, few drops were taken from the precipitate solution containing AgNPs-extracts and then dried on the aluminum foil sheet at room temperature. It was then subjected towards electron microscopy (Philips SEM, CMC-300 KV model, Netherlands) for morphological examination. In SEM, electron beams are triggered on the particles, as a result, electrons interact with the particles and generate signals containing information about particle, which is then detected by detector and then amplified in the form of SEM image.

2.5 Antimicrobial activity

2.5.1 Maintenance of culture

All the identified bacterial isolates were diluted in nutrient broth media with an optical density of 0.45–0.50 at 625 nm and then preserved in 15% (v/v) glycerol at − 80 °C. These bacterial isolates were sub-cultured on nutrient agar media and were incubated for 24 hr at 37 °C. This process was done to get the fresh culture of isolates for further processing.

2.5.2 Bacterial lawn preparation on nutrient agar media

Nutrient agar media (2.8 g per 100 ml) was prepared in separate flasks. Each flask containing media were sterilized using autoclave (Model No. DHWAC07080P) at 121 °C at 15 Psi pressure for 15 min. Media was then poured in the sterilized media plates. Inside Laminar Flow Hood (Model: VS-1300U, China), isolated bacterial colony was taken with sterile loop and was streaked on the media sterile plates. The plates were then incubated for 24 hr at 37 °C.

2.5.3 Confirmation of multidrug resistant (MDR) isolates

The antibiotics susceptibility test was performed using Kirby Bauer disc diffusion method. The bacterial isolates were subjected to different group of antibiotics i.e., Gentamycin (10 μg), Vancomycin (10 μg), Linezolid (10 μg), Ciprofloxacin (10 μg), Ceftazidime (10 μg) and Meropenem (10 μg) to check their susceptibility pattern against tested bacterial isolates. The isolates were categorized as sensitive (S), intermediate (I) and resistance (R) according to their zone of inhibition (Wayne, 2011).

2.5.4 Preparation of antibiotics discs with AgNPS coating

The antibiotics discs having AgNPs coating were prepared in such a way that 20 mg silver nano-powder was dissolved in 1 ml of sterile distilled water. Nano powder suspension was prepared in concentration of 20 μg/µl. Then selected antibiotics discs were placed on dry petri plate under sterile condition. After that, 5 µl nano-powder suspension was pipetted out with a micro-pipette and coated each disc with the prepared suspension. In this way, each antibiotic disc has 100 μg AgNPs. Then the impregnated discs were kept in an oven at 40 °C for at least 15 min to dry. The coated antibiotic discs were used against the tested MDR bacterial isolates.

2.5.5 Disc diffusion assay for combined effects of antibiotics and AgNPs

The coated antibiotics were kept on each MDR bacterial lawn on nutrient agar media. Then nano-coated discs were placed with sterile forceps and gently pressed. The plates were then incubated at 37 °C for 24 hr. The inhibition zones were measured in millimeter as per clinical and laboratory standards institute (CLSI) guidelines.

3 Results

3.1 Characterization of AgNPs

3.1.1 Visual analysis of the synthesized AgNPs

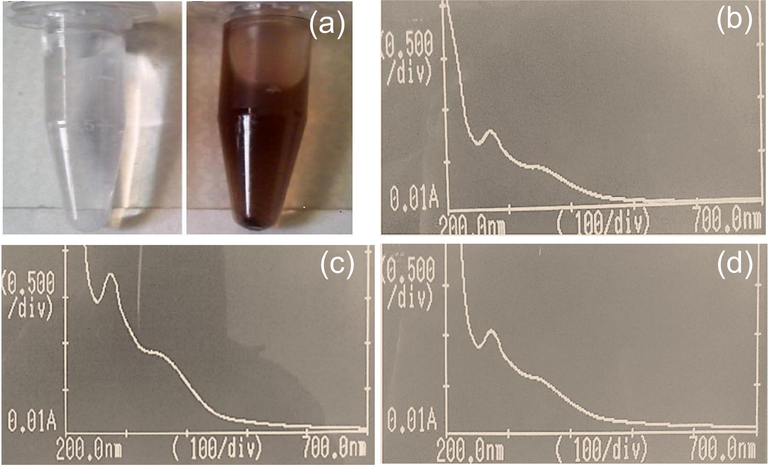

In the present study, visual confirmation of the AgNPs was done by noticing the change in the color of mixture of plant extract and nanoparticle. When AgNO3 was added to plant extracts, the color of the extract changes from yellowish to reddish brownish (Fig. 1a).

(a) Visual confirmation of silver nanoparticles i.e., silver nitrate solution and AgNPs formation; (b) UV–Vis spectrum of AgNPs synthesized from the leaves of P. hydropiper; (c) UV–Vis spectrum of AgNPs synthesized from the stem of P. hydropiper; (d) UV–Vis spectrum of AgNPs synthesized from the roots of P. hydropiper.

3.1.2 UV– vis spectrophotometric analysis of the synthesized AgNPs

In Fig. 1b, 1c and 1d, absorbance (on the vertical axis) is just a measure of the amount of light absorbed. The higher the value, the more of a particular wavelength is being absorbed. It was depicted that the UV–Vis spectrum of AgNPS synthesized from the leaves, stem, and roots of P. hydropiper showed strong absorption (OD) at 370 nm (lambda-max) with no other peak displayed high purity of the synthesized AgNPs.

3.1.3 Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of leaves extracts and AgNPs

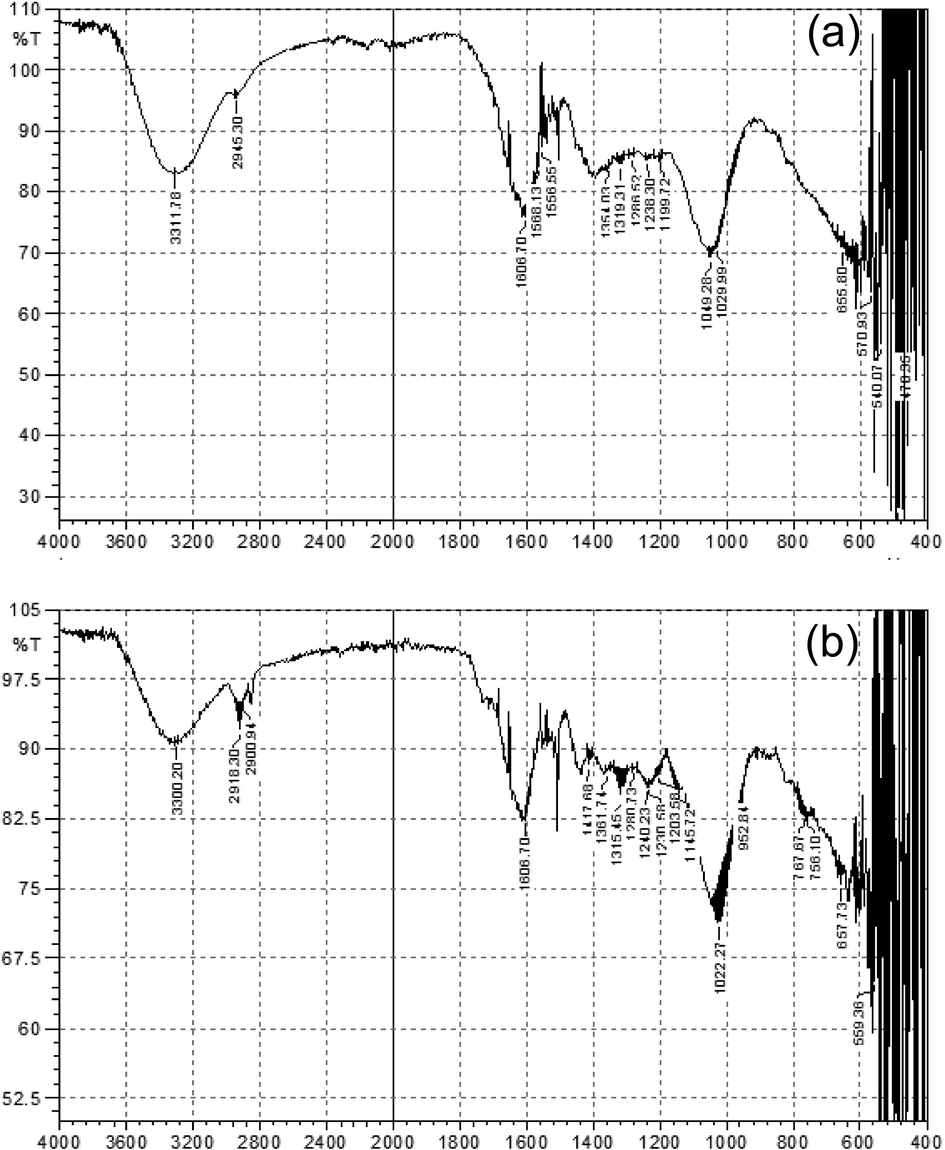

In the FTIR spectrum of the P. hydropiper leaves extract, different absorption peaks were observed indicating the presence of different functional groups i.e., peak value at 3311.78 cm−1 was due to vibration of stretch O-H having carboxylic acid, at 2945.30 cm−1 was due to C-H stretch of alkane, at 1568.13 cm−1, 1556.55 cm−1 and 1606.70 cm−1 were due to C-C stretching having aromatic compounds. Similarly, peak value at 1319.45 cm−1 was due to C-N stretching of aromatics amines, at 1286.52 cm−1 was due to band of C-H of alkyl halides, while peaks values at 1238.38 cm−1 and 1199.72 cm−1 showed C-N stretch in aliphatic amines (Fig. 2a).

(a) FTIR spectrum of P. hydropiper leaves extract; (b) FTIR spectrum of AgNPS synthesized from P. hydropiper leaves extract.

In addition to this, the FTIR spectrum of AgNPS (synthesized from the leaves extract) showed slight variations in wave numbers. The missing waves spectra at 1568.13 cm−1 and 1568.55 cm−1 suggested that the rings aromatics compounds might account for the AgNPS production. A minute change of the wave statistics was perceived at the wider stretch of 3311.78 cm−1 to 3300.20 cm−1, 1049.28 cm−1 to 1022.27 cm−1, 657.73 cm−1 to 655.80 cm−1, while stretches at 2900 cm−1, 1568.13 cm−1, 1556.55 cm−1, 1554.03 cm1, 1417.68 cm−1 and 1049.28 cm−1 were almost disappeared in the FTIR spectrum of AgNPS as shown in (Fig. 2b).

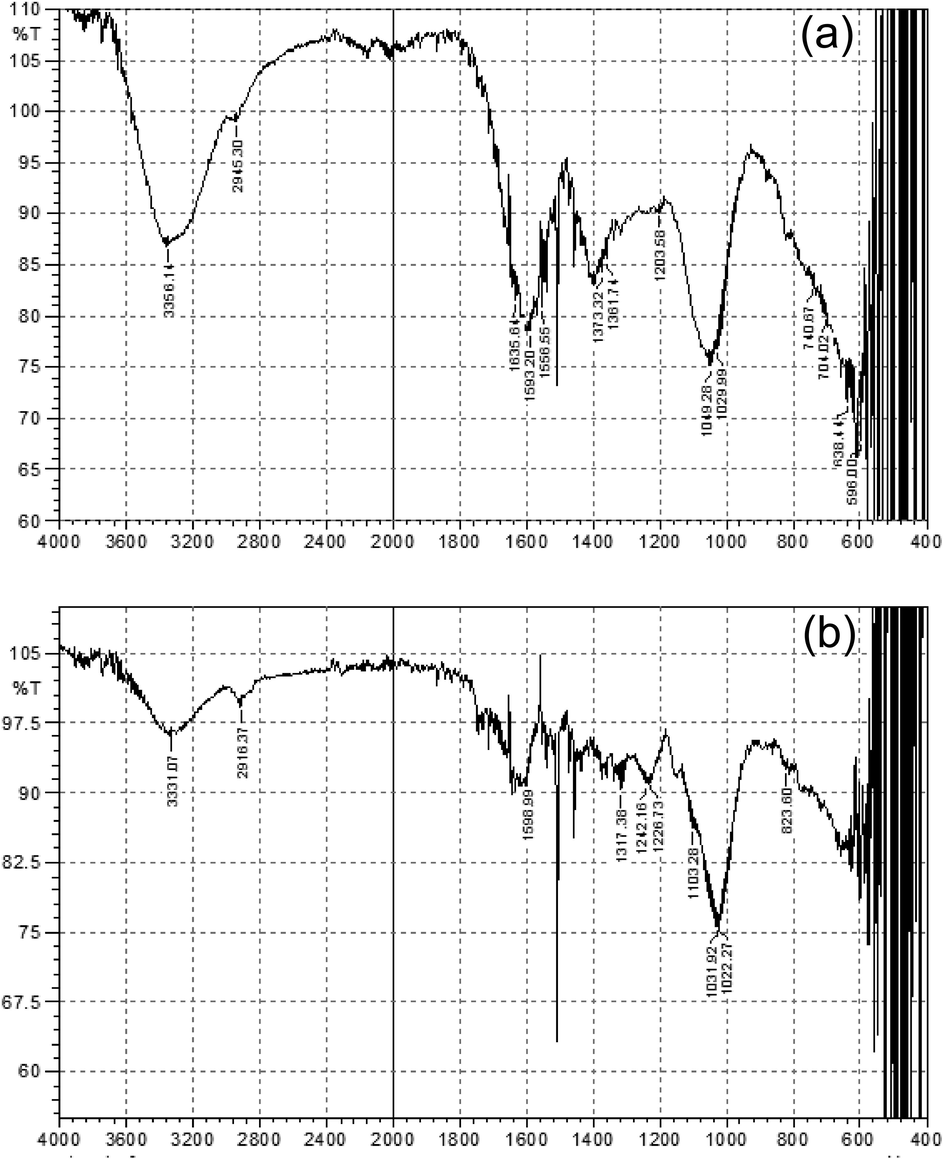

3.1.4 Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of stem extract and AgNPs

In the FTIR spectrum of the P. hydropiper stem extract, absorption peak at 3356.14 cm−1 was due to vibration of stretch N-H having amine and amides groups of proteins, peak value at 2945.30 cm−1 was due to C-H stretch of alkane, while peak at 1635.64 cm−1 displaying N-C bend having amines. Similarly, peaks at 1361.74 cm−1 and 1203.58 cm−1 displaying C-O symmetric stretch of nitro compounds, C-N stretch in aliphatic amines respectively. Moreover, all the three peaks at 1049.28 cm−1, 1029.99 cm−1 and 1199.72 cm−1 showing C-N stretch in aliphatic amines (Fig. 3a).

(a) FTIR spectrum of stem extract; (b) FTIR spectrum of AgNPS synthesized from P. hydropiper stem extract.

Moreover, the FTIR spectrum of AgNPS (fabricated using P. hydropiper stem extract) showed slight variations in wave numbers. Peaks of synthesized AgNPS suggested that the aromatics compounds might account for the AgNPS production. A minute’s change of the wave statistics was perceived at the wider stretch of 3356.14 cm−1 to 3331.07 cm−1, 2945.30 cm−1 to 2916.37 cm−1, 1049.38 cm−1 to 1031.92 cm−1 while, peak at 1556.55 cm−1 almost disappeared in the FTIR spectrum of AgNPS as shown in Fig. 3b.

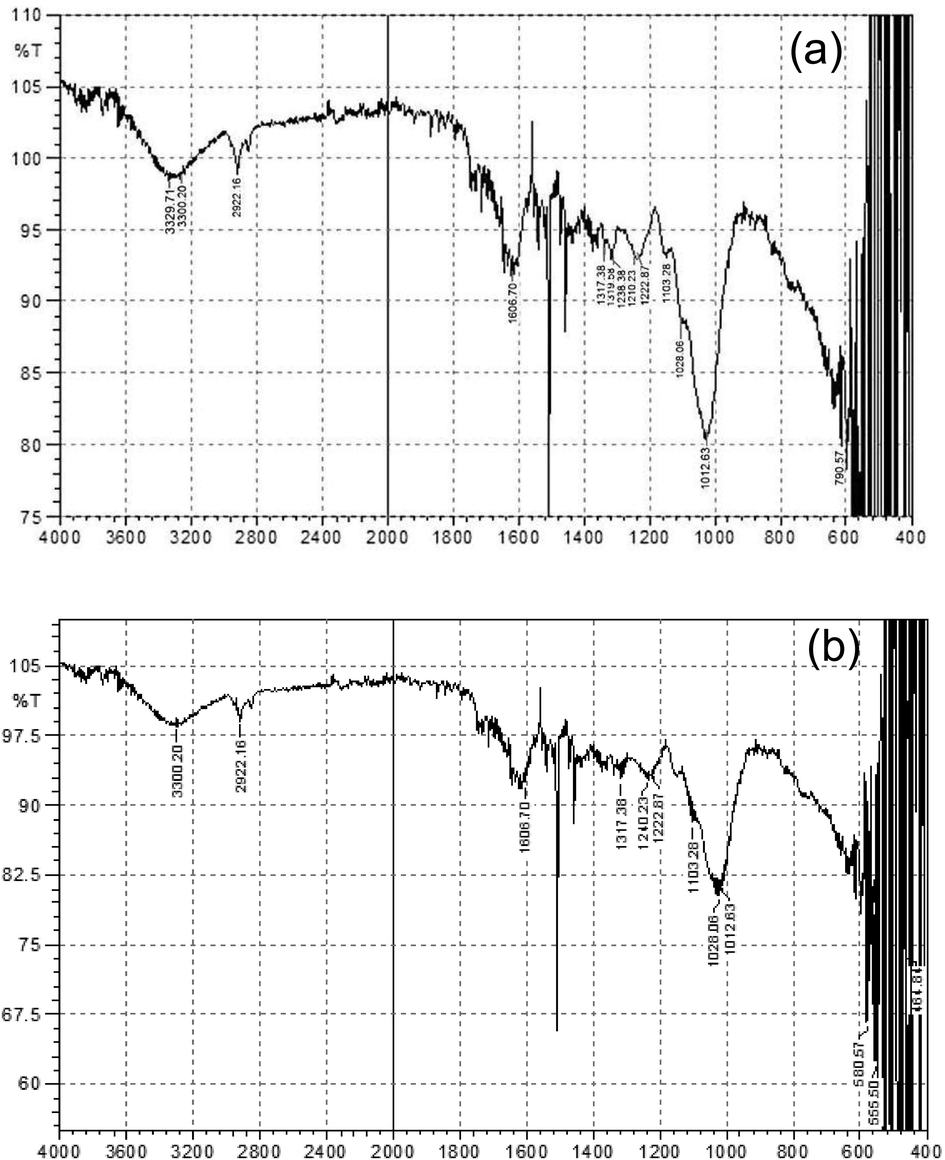

3.1.5 Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of root extract and AgNPs

In the FTIR spectrum of the P. hydropiper roots extract, the absorption peaks at 3329.71 cm−1, 2900.73 cm−1, 1606.70 cm−1, 1319.58 cm−1 and 1238.38 cm−1 were due to vibration of O-H stretch having carboxylic acid, C-H stretch of alkane, C-C stretching having aromatic compounds, C-N stretching of aromatics amines, and C-H alkyl halides respectively as shown in Fig. 4a.

(a) FTIR spectrum of root extract; (b) FTIR spectrum of AgNPS synthesized from P. hydropiper root extract.

On the other hand, FTIR spectrum of AgNPs (fabricated using P. hydropiper roots extracts) displayed slight variations in wave numbers. Peaks of synthesized AgNPS suggested that the aromatics compounds might account for the AgNPS production. Further, a minute’s change of the wave statistics was perceived at the wider stretch of 3329.71 cm−1 to 3311.78 cm−1, 2922.16 cm−1 to 2900.73 cm−1, 1222.87 cm−1 to 1199.17 cm−1 while, peak at 1575.15 cm−1 almost disappeared in the FTIR spectrum of AgNPS as shown in Fig. 4b.

3.1.6 SEM analysis of the synthesized AgNPs

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Philips SEM, CMC-300 KV model, Netherlands) was used to specify the size and morphology of synthesized AgNPS. SEM images of the leaves, stem and root synthesized-AgNPs displaying tetrahedron, spherical and oval shapes which were the characteric shapes of AgNPs (Figs. 5-7). Furthermore, the average size of the leaves, stem and root synthesized-AgNPs was determined by Image-J software and it was 32, 77 and 39 nm respectively.

SEM images of the leaves synthesized AgNPs nanoparticles (a) X10,000; (b) X20,000; (c) X30,000; (d) X60,000.

SEM images of the stem synthesized AgNPs nanoparticles (a) X250; (b) X500; (c) X30,000; (d) X60,000.

SEM images of the roots synthesized AgNPs nanoparticles (a) X10,000; (b) X20,000; (c) X20,000; (d) X30,000.

3.2 Antimicrobial activity

3.2.1 Synergistic activity of leaves synthesized AgNPs and antibiotics against MDR bacteria

Antibiotics such as Gentamycin, Vancomycin, Linezolid, Ciprofloxacin, Ceftazidime and Meropenem coated with AgNPs were tested against MDR bacteria. It was evident from the Table 1 that the potency of antibiotics increased after coating with synthesized AgNPs. In case of Gentamicin the potency increased up to 119% against Pseudomonas, vancomycin up to 200% against Proteus, Linezolid up to 121.4% against E. coli, Ciprofloxacin up to 290% against Bacillus, Ceftazidime up to 320% against Bacillus and Meropenem up to 60% against Staphylococcus. Key: AgNPs = Silver nanoparticles; mm = Millimeter.

Test organisms

Antibiotics with their mean zone of inhibition against test organisms in mm*

Gentamicin

Vancomycin

Linezolid

Ciprofloxacin

Ceftazidime

Meropenem

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Staphylococcus

20 ± 0.7

18 ± 0.3

11

9.5 ± 0.2

3.4 ± 0.1

179

32 ± 0.3

29 ± 0.2

10

15 ± 0.6

9.8 ± 0.0

53

35 ± 0.0

21 ± 0.3

67

40 ± 0.6

25 ± 0.6

60

Streptococcus

21.3 ± 0.0

12 ± 0.2

78

10 ± 0.2

4 ± 0.2

150

29 ± 0.9

22 ± 0.3

32

20 ± 0.2

19 ± 0.7

5

15 ± 0.1

10 ± 0.8

50

22 ± 0.4

20 ± 0.9

10

Bacillus

8.6 ± 0.6

4 ± 0.3

115

16 ± 0.4

9 ± 0.4

78

27 ± 0.0

18 ± 0.6

50

7.80 ± 0.4

2 ± 0.2

290

8.4 ± 0.2

2 ± 0.7

320

11 ± 0.2

7 ± 0.4

57

E. coli

25 ± 0.2

20 ± 0.0

25

15.7 ± 0.2

5.6 ± 0.9

180

31 ± 0.6

14 ± 0.6

121

13 ± 0.9

13 ± 0.7

0

19 ± 0.6

16 ± 0.3

19

23 ± 0.5

19 ± 0.2

21

Proteus

23 ± 0.3

19 ± 0.6

21

09 ± 0.0

3 ± 0.3

200

20 ± 0.2

11.4 ± 0.3

75

19 ± 0.4

10 ± 0.2

90

11 ± 0.5

6 ± 0.4

83

25 ± 0.4

20 ± 0.7

25

Pseudomonas

25 ± 0.3

11.4 ± 0.2

119

16 ± 0.5

15 ± 0.3

7

30 ± 0.3

27 ± 0.4

11

9.6 ± 0.1

3.4 ± 0.4

182

9.7 ± 0.6

3.8 ± 0.2

155

26 ± 0.3

25 ± 0.4

4

3.2.2 Synergistic activity of stem synthesized AgNPs and antibiotics against MDR bacteria

Antibiotics coated with stem synthesized AgNPs were also checked against MDR bacteria. It was observed that the potency of antibiotics increased after coating with synthesized AgNPs. In case of Gentamicin the potency increased up to 150% against Bacillus, vancomycin up to 200% against Staphylococcus, Linezolid up to 57.9% against Proteus, Ciprofloxacin up to 400%, Ceftazidime up to 450% and Meropenem up to 42.9% against Bacillus as shown in Table 2. Key: AgNPs = Silver nanoparticles; mm = Millimeter.

Test organisms

Antibiotics with their mean zone of inhibition against test organisms in mm*

Gentamicin

Vancomycin

Linezolid

Ciprofloxacin

Ceftazidime

Meropenem

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Staphylococcus

30 ± 0.6

18 ± 0.3

67

12 ± 0.2

4 ± 0.2

200

31 ± 0.6

29 ± 0.2

7

13 ± 0.3

9.8 ± 0.0

33

24 ± 0.4

21 ± 0.3

14

29 ± 0.4

25 ± 0.5

16

Streptococcus

18 ± 0.6

12 ± 0.2

50

10 ± 0.4

9 ± 0.4

11

29 ± 0.9

22 ± 0.3

32

23 ± 0.1

19 ± 0.6

21

15 ± 0.0

10 ± 0.5

50

22 ± 0.5

20 ± 0.8

10

Bacillus

10 ± 0.0

4 ± 0.3

150

11 ± 0.4

5.6 ± 0.9

96

23 ± 0.3

18 ± 0.5

28

12 ± 0.6

2 ± 0.2

400

11 ± 0.4

2 ± 0.6

450

10 ± 0.2

7 ± 0.3

43

E. coli

21 ± 0.4

20 ± 0.0

5

8.4 ± 0.9

3 ± 0.3

180

17 ± 0.0

14 ± 0.5

21

15 ± 0.6

13 ± 0.5

15

16 ± 0.1

09 ± 0.1

78

23 ± 0.3

19 ± 0.2

21

Proteus

20 ± 0.7

19 ± 0.6

5

15 ± 0.6

11 ± 0.3

36

18 ± 0.5

11.4 ± 0.3

58

16 ± 0.3

10 ± 0.2

60

9.5 ± 0.3

6 ± 0.3

58

22 ± 0.1

20 ± 0.6

10

Pseudomonas

19 ± 0.1

11.4 ± 0.2

67

19 ± 0.2

4 ± 0.2

375

32 ± 0.3

27 ± 0.3

19

11 ± 0.5

3.4 ± 0.3

224

8 ± 0.4

3.8 ± 0.2

111

26 ± 0.3

25 ± 0.3

4

3.2.3 Synergistic activity of root synthesized AgNPs and antibiotics against MDR bacteria

Roots synthesized AgNPs coated antibiotics were also tested against MDR bacteria. It was found that the potency of antibiotics increased after coating with synthesized AgNPs. In case of Gentamicin the potency increased up to 175% against Bacillus, vancomycin up to 266.7% and Linezolid up to 75.4% against Proteus, Ciprofloxacin up to 500%, Ceftazidime up to 350% and Meropenem up to 57.1% against Bacillus as shown in Table 3. Key: AgNPs = Silver nanoparticles; mm = Millimeter.

Test organisms

Antibiotics with their mean zone of inhibition against test organisms in mm*

Gentamicin

Vancomycin

Linezolid

Ciprofloxacin

Ceftazidime

Meropenem

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Coated with AgNPs

Without coating

Potency Increase (%)

Staphylococcus

28 ± 0.1

18 ± 0.3

56

11 ± 0.3

3.4 ± 0.1

224

30 ± 0.4

29 ± 0.2

3

14 ± 0.1

9.8 ± 0.0

43

23 ± 0.8

21 ± 0.3

7

28 ± 0.2

25 ± 0.5

12

Streptococcus

20 ± 0.5

12 ± 0.1

67

11 ± 0.8

4 ± 0.2

175

23 ± 0.2

22 ± 0.3

5

20 ± 0.6

19 ± 0.0

5

15 ± 0.4

10 ± 0.5

50

24 ± 0.5

20 ± 0.8

20

Bacillus

11 ± 0.4

4 ± 0.3

175

14 ± 0.8

9 ± 0.3

56

26 ± 0.5

18 ± 0.5

44

12 ± 0.8

2 ± 0.2

500

10 ± 0.5

2 ± 0.6

350

11 ± 0.1

7 ± 0.3

57

E. coli

24 ± 0.2

20 ± 0.0

20

18 ± 0.3

5.6 ± 0.8

221

17 ± 0.3

14 ± 0.5

21

13 ± 0.3

13 ± 0.3

0

16 ± 0.3

9.4 ± 0.3

70

23 ± 0.1

19 ± 0.2

21

Proteus

23 ± 0.6

19 ± 0.5

21

11 ± 0.1

3 ± 0.3

267

20 ± 0.8

11.4 ± 0.3

75

17 ± 0.3

10 ± 0.2

70

8.7 ± 0.6

6 ± 0.3

45

21 ± 0.3

20 ± 0.6

5

Pseudomonas

11.4 ± 0.5

9 ± 0.2

27

18 ± 0.6

15 ± 0.3

20

27 ± 0.0

23 ± 0.3

17

21 ± 0.3

3.4 ± 0.9

518

7 ± 0.0

3.8 ± 0.2

84

29 ± 0.4

25 ± 0.3

16

4 Discussion

In this study, AgNPs were synthesized from P. hydropiper leaves, stem, and roots extracts to determine their bio-catalytic potential to enhance the activity of commercially available antibiotics against MDR bacteria. For this purpose, ecofriendly process of green synthesis was used as prescribed by Shaik et al. (2018). Panáček et al. (2006) also accredited green synthesis method in their study as compared to physical and chemical methods for fabrication of AgNPS. In the current study, synthesis of AgNPs from the leaves, stem, and roots of P. hydropiper were visually confirmed by noticing the change in color from yellowish green to reddish brown. Furthermore, it was confirmed by UV–VIS spectroscopy, where a characteristics peak (surface plasmon resonance intensification) of synthesized AgNPs was observed at 370 nm. Krithiga et al. (2015) determined absorption peaks at 420 and 440 nm in their study for Clitoria ternatea and Solanum nigrum based AgNPs respectively. Furthermore, they reported that the lambda max of silver was 346 nm (UV spectrum) while the UV–Visible spectrum of synthesized AgNPs found in the range of 360 nm to 470 nm depending on their shape and size. Nasir et al. (2016) also found absorption peak of AgNPS synthesized from the olive leaves extracts at 419 nm.

Further, FTIR spectroscopy was used for the identification of different functional groups responsible for reducing and stabilizing of silver nanoparticles. The FT-IR spectra were recorded for extract and AgNPS. It was observed that the FTIR spectra of leaves extract displaying different bands representing different functional groups however, the position of functional groups changed in the FTIR spectrum of leaves extracts synthesized AgNPs. Changes were recorded at 3300.20 cm−1 to 3311.78 cm−1, 1029.99 cm−1 to 1022.27 cm−1, 657.73 cm−1 to 655.80 cm−1 whereas the peaks at 2900 cm−1,15 68.13 cm−1, 1556.55 cm−1 1554.03 cm−1,1417.68 cm−1 and 1049.28 cm−1 were almost disappeared. The missing peaks of 1568.13 cm−1, 1556.55 cm−1 and 1568.55 cm−1 in FTIR spectrum of synthesized AgNPS suggested that the rings aromatics compounds might account for the AgNPS production (Fig. 2). Khodadadi et al., (2021) conducted similar study and found two new peaks at 1638 cm-1and 3449 cm−1 confirmed the presence of oxygenated compounds in the FTIR analysis of AgNPs synthesized from the fruit extract of Vaccinium arctostaphylos. In comparison, Maity et al., (2019) also performed FTIR analysis of synthesized AgNPs using mangrove fruit polysaccharide extract and found peaks around 3430 cm−1, 2,910 cm−1, 1600 cm−1, 1450 cm−1, and 1070 cm−1 which confirmed the presence of O-H stretching, aldehydic C-H stretching, C = C group, –COO stretching, and -C-O-C- stretching, respectively (Fig. 2). Another study conducted by Raja et al. (2017) revealed that various functional groups were responsible for reduction of silver nanoparticle in Calliandra haematocephala leaves extracts when analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy.

The FTIR spectrum of AgNPs synthesized from the stem extract displayed changed in the position of functional groups as compared FTIR spectrum of stem extract. Even some of the groups in stem extract FTIR spectrum i.e., 1556.55 cm−1 peak was missed in the FTIR spectrum of AgNPs recommended its production by the rings aromatics compounds (Fig. 3). In comparison, Begum et al. (2009) conducted study on the synthesis of gold (Au) and AgNPs using black tea leaf extracts and also reported the peak bands in the FTIR spectrum of AgNPs at 1697, 1618, 1514, 1332 and 1226 cm−1 which were related with the stretching vibrations for –C = C–C O, –C = C– aromatic, –C–C– aromatic, C–O (esters, ethers) and C–O (polyols), respectively. Balachandar et al., (2019) also found similar changed in the functional group of AgNPs synthesized from the stem extract of Phyllanthus pinnatus. While the FTIR peaks of AgNPS synthesized from the root extract were recorded at different vibration bands displaying O-H stretch having carboxylic acid, C-H stretch of alkane, C-C stretching having aromatic compounds, C-N stretching of aromatics amines and C-H alkyl halides respectively. However, in comparison to FTIR spectrum of root extract, some of the peaks were missed in the FTIR spectrum of AgNPs suggested that the rings aromatics compounds might account for the AgNPS production (Fig. 4). In similar report of Logaranjan et al. (2016), the FTIR analysis observed the peak values of AgNPs at 1587.6 cm−1 (C = C groups or from aromatic rings), 1386.4 cm−1 (geminal methyl), and 1076 cm−1 (ether linkages) indicated the presence of flavanones or terpenoids. Following by another study in which AgNPs was synthesized from the root extract of Phoenix dactylifera where, the FT-IR spectrum revealed peak at 3896 cm−1 indicated the binding of Ag with N-H and or O-H group, the peak band at 1395 to 1658 cm−1 indicated C-H stretching vibrations of alkene whereas the peak at 1129 cm−1 revealed the C-H in plane bending of alkenes, alcohols, carboxylic acids, esters, and ethers respectively (Oves et al., 2018).

In addition, SEM analysis was performed for overall appearance of the sample. The particle dimension and its shape were determined by SEM image-j software for the calculation of size and shapes of synthesized AgNPS. SEM micrograph of AgNPS showed that these nanoparticles present in various shapes (spherical, tetrahedron and oval) and sizes. The size of the AgNPs synthesized from the extracts of leaves, stem, and roots was 32, 77 and 39 nm respectively. Size comparison demonstrates that the manufactured AgNPS were of diverse sizes (Figs. 5-7). These results are correlated with study performed by Somashekarappa (2021), where spherical shaped AgNPs with agglomerated appearance were recorded in the SEM image.

Moreover, in the present study, the synergetic effect of silver nanoparticles coated antibiotics were increased against Gram-positive and Gram-negative multidrug resistance bacteria determined by the disc diffusion assay. It was observed that the potency of antibiotics against tested MDR bacteria increased after coating with leaves, stem, and root synthesized AgNPs (Table 1-3). These results agreed with previous studies indicating that AgNPs fabricated by using Aloe extracts had a high inhibitory action against E. coli (42 mm ZI) at low concentration (Zhang et al., 2010). Similar study was also performed by Gogoi et al. (2006) and found that plant extracts synthesized AgNPS exhibited high inhibitory effects against E. coli (22 mm) and Salmonella (19 mm) while moderate activity was observed against Pseudomonas sp., and Bacillus sp. Furthermore, Boateng and Catanzano (2020) reported that AgNPs coated antibiotics inhibit the bacterial growth at very low concentration than non-coated antibiotics and up till now no side effects were reported for coated antibiotics. Almalah et al. (2019) found similar results against multidrug resistance bacteria using disc diffusion method. It has been stated that the biological activity of AgNPs is constantly related with their antimicrobial properties and hence considered an effective agent, inhibiting the growth of different Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial pathogens (Pryshchepa et al., 2020). AgNPs promotes the efficacy of antibiotics towards the site of action in bacteria, as it increases cell permeability that facilitate the intracellular access of antibiotics and hence greatly affect bacterial cells by altering metabolic pathways, DNA, protein synthesis and the disruption of cell wall and cell membrane (Vazquez-Muñoz et al., 2019; Aabed and Mohammed et al., 2021). Vazquez-Muñoz et al. 2019 suggested that enhancement in antimicrobial activity could be attributed to the NPs-antibiotic combined chemical interaction, however, further studies are still needed to justify this phenomenon. Railean-Plugaru et al. (2016) also conducted similar study and found that the growth of E. coli, Salm. infantis and K. Pneumonia was synergistically inhibited by antibiotics coated with AgNPs. Rafińska et al. (2019) also found synergistic effect of synthesized AgNPs with antibiotics against B. subtilis.

5 Conclusions

It was concluded that phytogenic mediated approach for the synthesis of AgNPS using P. hydropiper extracts was a rapid and effective method. Moreover, synthesized AgNPs displaying excellent synergistic effect to enhance the activity of antibiotics against MDR bacterial species. Absorption peak at 370 nm using UV–VIS spectroscopy confirmed the presence of AgNPs which was further confirmed by FTIR spectrum and SEM analysis. It was concluded that FTIR spectrum at peak values of 1554.03 cm−1, 1556.55 cm−1 and 1568.13 cm−1 confirmed the AgNPs formation while tetrahedron, spherical and oval shape of nanoparticles in SEM images confirmed the characteristic shape of AgNPs. In addition to this catalytic activity of AgNPs to enhance the activity of commercially available antibiotics against MDR bacterial isolates was also determined using disc diffusion assay. It was concluded the potency of antibiotics against MDR bacteria increased after coating with synthesized AgNPs i.e., the potency of Ceftazidime and Ciprofloxacin increased up to 450% and 500% against Bacillus respectively while, the potency of Gentamicin, Vancomycin and Linezolid increased up to 150%, 200% and 58% against Bacillus, Staphylococcus, and Proteus species respectively. Additionally, it is recommended that further research work is needed to use other metals (zinc, gold, and iron) against resistant bacterial and fungal pathogens. While in vivo models of mice should be used to observe phytogenic mediated AgNPs activity against bacterial pathogens.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ghadir Ali: Conceptualization, Methodology. Aftab Khan: . Asim Shahzad: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Aiyeshah Alhodaib: Writing – review & editing. Muhammad Qasim: Writing – review & editing. Iffat Naz: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Abdul Rehman: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision.

Acknowledgements

The researchers would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research, Qassim University for funding the publication of this project.

Ethics approval

Not applicable as no human or animals were involved in this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Insecticidal, brine shrimp cytotoxicity, antifungal and nitric oxide free radical scavenging activities of the aerial parts of Myrsine africana L. Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2011;10(8):1448-1453.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review on plants extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles for antimicrobial applications: a green expertise. J. Adv. Res.. 2016;7(1):17-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical screening for active compounds in Mangifera indica leaves from Ibadan. Oyo State. Plant Sci. Res.. 2009;2(1):11-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance in bloodstream infections. Virulence. 2016;7(3):252-266.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Cinnamomum zeylanicum and their synergistic effect against multi-drug resistance bacteria. J. Nanotechnol. Res.. 2019;1(3):95-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Persicaria hydropiper (L.) Delarbre: A review on traditional uses, bioactive chemical constituents and pharmacological and toxicological activities. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2020;251:112516

- [Google Scholar]

- Banana peel extract mediated novel route for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles. Colloids Surf., A Physicochem. Eng. Asp.. 2010;368(1–3):58-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biogenic synthesis of Au and Ag nanoparticles using aqueous solutions of Black Tea leaf extracts. Colloids Surf. B. 2009;71(1):113-118.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Diospyros malabarica fruit extract and assessments of their antimicrobial, anticancer and catalytic reduction of 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) Nanomaterials. 2021;11(8):1999.

- [Google Scholar]

- Silver and silver nanoparticle-based antimicrobial dressings. Therap. Dressings Wound Healing App. 2020:157-184.

- [Google Scholar]

- Silver nanoparticles: therapeutical uses, toxicity, and safety issues. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2014;103(7):1931-1944.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green fluorescent protein-expressing Escherichia coli as a model system for investigating the antimicrobial activities of silver nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2006;22(22):9322-9328.

- [Google Scholar]

- Economic evaluation of nosocomial infections in pediatric intensive care units in Lithuania. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). 2010;46(11):781-789.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multidimensional effects of biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles in Helicobacter pylori, Helicobacter felis, and human lung (L132) and lung carcinoma A549 cells. Nanoscale Res. Lett.. 2015;10(1):1-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Two-dimensional thin-layer chromatography of selected Polygonum sp. extracts on polar-bonded stationary phases. J. Chromatogr. A. 2011;1218(19):2812-2819.

- [Google Scholar]

- CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care–associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am. J. Infect. Control.. 2008;36(5):309-332.

- [Google Scholar]

- Huq, A.K.M., Jamal, J.A., Stanslas, J., 2014. Ethnobotanical, phytochemical, pharmacological, and toxicological aspects of Persicaria hydropiper (L.) Delarbre. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2014.

- Antibacterial activity of silver: the role of hydrodynamic particle size at nanoscale. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2014;102(10):3361-3368.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of silver nanoparticles synthesized by acidophilic strain of Actinobacteria isolated from the of Picea sitchensis forest soil. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2016;120(5):1250-1263.

- [Google Scholar]

- Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, investigation techniques, and properties. Adv. Colloid. Interf. Sci.. 2020;284:102246

- [Google Scholar]

- Lactococcus lactis as a safe and inexpensive source of bioactive silver composites. Appl. Micro. Biotech.. 2017;101(19):7141-7153.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhancement of antibiotics antimicrobial activity due to the silver nanoparticles impact on the cell membrane. PloS One. 2019;14(11):e0224904

- [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic and antagonistic effects of biogenic silver nanoparticles in combination with antibiotics against some pathogenic microbes. Front. Bio. Biotech.. 2021;9:249.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of Bacillus subtilis response to different forms of silver. Sci. Total. Envir.. 2019;661:120-129.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of the green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using a natural extract of dark or white Salvia hispanica L. seeds and their antibacterial application. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2019;489:952-961.

- [Google Scholar]

- Silver nanoparticles supported on polyethylene glycol/cellulose acetate ultrafiltration membranes: preparation and characterization of composite. Cellulose. 2017;24(11):4997-5012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of copper nanoparticles using different plant extracts and their antibacterial activity. J. Enviro. Chem. Eng.. 2022;4:107130

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaf extracts of Clitoria ternatea and Solanum nigrum and study of its antibacterial effect against common nosocomial pathogens. J. Nanosci.. 2015;2015:2015.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigating the possibility of green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Vaccinium arctostaphlyos extract and evaluating its antibacterial properties. BioMed. Res. Int.. 2021;3:2021.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using mangrove fruit polysaccharide for bacterial growth inhibition. Asi. J. Pharm. Clin. Res.. 2019;12:179-183.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant-mediated synthesis, characterization and bactericidal potential of emerging silver nanoparticles using stem extract of Phyllanthus pinnatus: a recent advance in phytonanotechnology. J. Clus. Sci.. 2019;30(6):1481-1488.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and anticancer activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized from the root hair extract of Phoenix dactylifera. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C. 2018;89:429-443.

- [Google Scholar]

- Shape-and size-controlled synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Aloe vera plant extract and their antimicrobial activity. Nanoscale Res. Lett.. 2016;11(1):1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory compound of tyrosinase activity from the sprout of Polygonum hydropiper L. (Benitade) Biol. Pharm. Bull.. 2007;30(3):595-597.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using olive leaves extract and sorbitol. Iraqi J. Biotechnol.. 2016;15(1)

- [Google Scholar]

- Silver colloid nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, and their antibacterial activity. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110(33):16248-16253.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles from Cassia auriculata leaf extract and in vitro evaluation of antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Appl. Biol. Pharm.. 2012;3(2):222-228.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nano encapsulation: a new trend in food engineering processing. Food Eng. Rev.. 2010;2(1):39-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Calliandra haematocephala leaf extract, their antibacterial activity and hydrogen peroxide sensing capability. Arab. J. Chem.. 2017;10(2):253-261.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant-extract-assisted green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using Origanum vulgare L. extract and their microbicidal activities. Sustainability. 2018;10(4):913.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytonutrient assisted synthesis and stabilization of silver nanoparticles from the leaf extract of Persicaria hydropiper (L.) Delarbre and their antibacterial activity studies. J. Sci. Res.. 2021;65(1)

- [Google Scholar]

- Wayne, P.A., 2011. Clinical and laboratory standards institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

- Silver nanoparticles: synthesis, medical applications and biosafety. Theranostics. 2020;10(20):8996.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synergetic antibacterial effects of silver nanoparticles @ aloe vera prepared via a green method. Nano Biomed. Eng.. 2010;2(4):252-257.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104053.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1