Translate this page into:

Dioxomolybdenum(VI) chelates of bioinorganic, catalytic, and medicinal relevance: Studies on some cis-dioxomolybdenum(VI) complexes involving O, N-donor 4-oximino-2-pyrazoline-5-one derivatives

*Corresponding author. Tel.: +91 761 2601303; fax: +91 761 2603752 rcmaurya1@gmail.com (R.C. Maurya)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Available online 18 January 2011

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

A new series of five mixed-ligand complexes of dioxomolybdenum(VI) of the general composition [MoO2(L)2(H2O)2], where LH = 4-acetyloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one (aomppH), 3-methyl-1-phenyl-4-propionyloxime-2-pyrazolin-5-one (mppopH), 4-butyryloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one (buomppH), 4-iso-butyryloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one (ibuomppH) or 4-benzoyloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one (bomppH) has been synthesized by the interaction of [MoO2(acac)2] with the said ligands in ethanol medium. The complexes so obtained were characterized by elemental analyses, molar conductance, decomposition temperature and magnetic measurements, thermogravimetric analyses, 1H NMR, IR, mass, and electronic spectral studies. The 3D molecular modeling and analysis for bond lengths and bond angles have also been carried out for one of the representative compound, [MoO2(aomppH)2(H2O)2] (1) to substantiate the proposed structure.

Keywords

Dioxomolybdenum(VI) chelates

O, N-donor oximes

3D Molecular modeling

1 Introduction

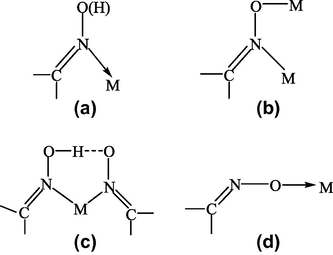

Oxime/oximate metal complexes have been investigated actively since the beginning of the last century of the last millennium (Kukushkin and Pombeiro, 1999). Dimethylglyoxime (or diacetyldioxime) was the first organic reagent to be used in analytical chemistry for the estimation of nickel (Tschugaeft, 1905, 1908). Since then, the analytical application of a number of bidentate chelate ligands like dioximes and aromatic hydroxyl aldoximes have been extensively studied (Diehl, 1940; Banks, 1963). Apart from analytical applications, studies have been conducted on their stability data with a variety of metal ions in aqueous medium and also on their coordination behavior (Mehrotra et al., 1975; Singh et al., 1974). Although, oximes are widely recognized as versatile ligands and their complexes with various transition metals have been studied in detail (Mehrotra et al., 1975; Singh et al., 1974), much remains to understand the type of structures that are formed. In general the oxime function is known (Chakravorty, 1974) to coordinate in four ways as shown in Fig. 1. Coordination modes (a) and (c) are observed most frequently although the oxime group is a poor donor unless it is a part of the chelate ring. Oximes can react either as such or in the form of a conjugate base. This is what is meant by putting the hydrogen atom in (a) in parenthesis. This atom may or may not be present. In (c) one oxime group is present as such while the second group is present as the conjugate base; the single hydrogen atom is then shared in the O–H⋯O bridge.

Various coordination modes of oximes.

The chelating behavior of 4-oximino-2-pyrazoline-5-ones (Shah and Shah, 1981, 1982a,b; Patel and Shah, 1985; Maurya et al., 2003d; Masoud et al., 1986) is well established. They coordinate through the cyclic carbonyl oxygen and oximino nitrogen, thus behaving as bidentate O, N donors. Since the increasing use of coordination compounds in analytical chemistry, pigments, medicine and biochemistry, many investigators have studied these topics, especially the important role of oxime complexes in chemistry (Pande, 1966; Schrazer, 1976; Brown, 1973; Gok and Bekaroglu, 1981; Irez and Bekaroglu, 1983; Gul and Bekaroglu, 1982; Kocak and Bekaroglu, 1985; Ozcan and Mirzaoglu, 1988; Ucan and Mirzaoglu, 1990; Sevindir and Mirzaoglu, 1992; Karatas et al., 1991a; Ucan and Karatas, 1991; Pekacar and Ozcan, 1994, 1995a,b; Mercimek et al., 1995; Karatas and Ucan, 1998; Karatas et al., 1991b; Reddy et al., 2000; Alexandrova et al., 2000; Yildim et al., 2003; Zulfikaroglu et al., 2003).

The coordination compounds of molybdenum can catalyze a variety of industrially important chemical reactions such as olefin epoxidation (Abrantes et al., 2003; Li et al., 2010), isomerization of allyl alcohols (Franczek et al., 2002), and olefin metathesis (Schrock, 2004). The useful role of molybdenum is not restricted to artificial catalysis alone, since it is an essential element in diverse biological systems, as nature has made use of the molybdenum center in various redox enzymes (Collision et al., 1996; Hille, 1996; Enemark et al., 2004). Oxidized forms of these molybdoenzymes, e.g., aldehyde and sulfite oxidases are supposed to contain cis-MoX2 units (X = O, S) coordinated to sulfur, nitrogen and oxygen donor atoms of the protein structure.

The presence of the cis-dioxomolybdenum(VI) cation, [MoO2]+2, in the oxidized form of certain molybdoenzymes (Stiefel, 1979a), has stimulated both the search for new structures in which this moiety is coordinated to ligands containing nitrogen, oxygen and/or sulfur donors and also to the study of their chemicals, spectroscopic, and structural properties (Stiefel, 1979b).

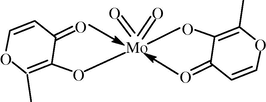

Molybdenum bears some resemblance to vanadium. Both vanadate and molybdate can strongly inhibit protein tyrosine phosphatase activity, thus maintaining tyrosine phosphorylation in protein extracts, although molybdate is less strongly bound in the enzyme active site (Elberg et al., 1995). Molybdate was shown to inactivate glycogen synthase and increase the glycolytic flux in rat hepatocytes (Fillat et al., 1992) and to display synergistic stimulation of glucose uptake in rat adipocytes in the presence of H2O2 (Elberg et al., 1995; Goto et al., 1992), again analogous to in vitro effects of vanadate. Sodium molybdate dihydrate (Na2MoO4·2H2O), 0.4–0.5 g L−1 in drinking water and 0.75–1.25 g Kg−1 in food for 8 weeks in STZ-diabetic rats, led to 75% blood glucose lowering and also normalized plasma triglyceride and non-esterified fatty acid levels, without affecting plasma insulin (Ozcelikay et al., 1996), in STZ-diabetic rats. Thus, in view of these findings efforts are being made to synthesize complexes of MoO22+ containing oxygen and/or nitrogen environment, such as, bis(maltolato)dioxomolybdenum(VI) (BMDOM) complex, [MoO2(ma)2] (Shuter, 1995, Fig. 2).

Structure of BMDOM.

Most molybdenum(VI) complexes contain cis-MoO22+ and an octahedral geometry. Although many precursors are available, [MoO2(acac)2] is a convenient source of MoO22+ (Mohanty and Dash, 1990; Syamal and Maurya, 1989).

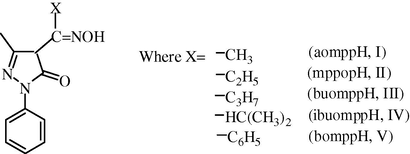

In continuation of interest in the synthesis and characterization of coordination compounds of bioinorganic and medicinal relevance, a study was undertaken of the coordination chemistry of dioxomolybdenum(VI) complexes involving 4-oximino-2-pyrazoline-5-ones, such as, 4-acetyloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (aomppH, I), 3-methyl-1-phenyl-4-propionyloxime-2-pyrazoline-5-one (mppopH, II), 4-butyryloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (buomppH, III), 4-isobutyryloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (ibuomppH, IV), 4-benzoyloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (bomppH, V). The structure of the oxime derivatives used in the present study is shown in Fig. 3.

Structures of various oximes.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

3-Methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one- (Lancaster, UK), benzoyl chloride, acetyl chloride and propionyl chloride, hydroxylamine hydrochloride, acetylacetone, calcium hydroxide (Thomas Baker Chemicals Limited, Mumbai), butyryl chloride, iso-butyryl chloride (Merck, Germany) and Sodium hydroxide (E. Merck India Limited, Mumbai), ammonium molybdate tetrahydrate (Sisco Chem. Industries, Mumbai) were used as supplied. Alcohol was purchased from Bengal Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals Limited, Kolkata. All other chemicals used were of analytical reagent grade.

2.2 Preparation of parent compound

The parent compound bis(acetylacetonato)dioxomolybdenum(VI), [MoO2(acac)2] was prepared by the method of Chen et al. (Chen et al., 1976).

2.3 Preparation of different 4-acyl-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one

They were prepared by the Jensen’s (Jensen, 1959) method with slight modification. Into a one liter 3-necked quick fit flask containing DMF (100 mL) and carrying a dropping funnel, a mechanical stirrer, and a reflux condenser, was placed 3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one (17 g, 0.098 M). A solution was obtained by gentle heating, and benzoyl chloride (12 mL)/acetyl chloride (5.4 mL)/propionyl chloride 8.94 mL)/butyryl chloride (10.33 mL)/isobutyryl chloride (11 mL) was added drop wise within 2–3 min. The reaction was exothermic and the reaction mixtures became a paste. The mixture was allowed to cool and then refluxed with stirring for 1 h on a sand bath, during which period the bright yellow complex formed initially turned yellowish brown. The complex was decomposed by pouring the reaction mixture into chilled dilute hydrochloric acid solution (500 mL, 3 N). A yellowish brown solid settled, which was filtered in a sintered glass crucible, washed with distilled water until the washings were colorless, and dried in air and recrystallized from n-heptane. Some important physical properties are given in the Table 1. bmppH = 4-benzoyl-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one. bumppH = 4-butyryl-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one. amppH = 4-acetyl-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one. pmppH = 3-methyl-1-phenyl-4-propionyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one. Iso-bumppH = 4-iso-butyryl-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one.

Abbreviation

Empirical formula

m.p.

Color

Yield (%)

bmppH

(C17H14N2O2) (278)

90

Yellow

75

bumppH

(C14H16N2O2) (244)

65

Yellow

70

amppH

(C12H12N2O2) (216)

60

Yellow

50

pmppH

(C13H14N2O2) (230)

68

Yellow

60

iso-bumppH

(C14H16N2O2) (244)

57

Yellow

50

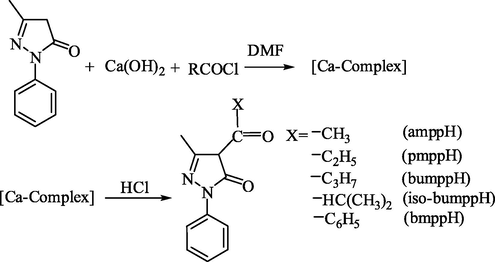

The reaction scheme related to the synthesis of 4-acyl-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one is as follows (Scheme 1.).

Reaction scheme for the synthesis of 4-acyl-3-mthyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one derivatives.

2.4 Preparation of oxime derivatives of bmppH, bumppH, amppH, pmppH, iso-bumppH

These oximes were prepared by following the general method given below: A solution of hydroxylamine hydrochloride (0.347 g, 5 mmol) and sodium hydroxide (0.20 g, 5 mmol) in 40 mL aqueous/ethanol (1:1) was added to a solution of 4-benzoyl-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one (1.39 g, 5 mmol), 4-acetyl-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one (1.08 g, 5 mmol), 3-methyl-1-phenyl-4-propionyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one (1.15 g, 5 mmol), 4-butyryl-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (1.22 g, 5 mmol), or 4-iso-butyryl-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one (1.22 g, 5 mmol) in 20 mL ethanol. The mixture was refluxed for two hours. On cooling a crystalline product was obtained, which was filtered by suction, washed several times with water and finally with ethanol. The oxime of 4-benzoyl-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-one was precipitated by pouring the reaction mixture in excess (150 mL) of distilled water. The characterization data of the oxime derivatives are given in Table 2.

S. No.

Ligand(empirical formula) (F.W.)

Analyses, found/(calcd.), %

Color

Decomposition temp. (°C)

C

H

N

I

aomppH(C12H13N3O2) (231)

62.22 (62.34)

5.52 (5.63)

18.09 (18.18)

Golden brown

170

II

mppopH(C13H15N3O2) (245)

63.47 (63.67)

6.05 (6.12)

17.10 (17.14)

Pale cream

160

III

buomppH(C14H17N3O2) (259)

64.75 (64.86)

6.48 (6.56)

16.18 (16.22)

Daffodil

165

IV

ibuomppH(C14H17N3O2) (259)

64.70 (64.86)

6.48 (6.56)

16.15 (16.22)

Volcano

140

V

bomppH(C17H15N3O2) (293)

69.50 (69.62)

5.06 (5.12)

14.29 (14.33)

Sugar cane color

155

2.5 Preparation of complexes

The oximes derivative, bomppH (0.586 g, 2 mmol), aomppH (0.462 g, 2 mmol), mppopH (0.490 g, 2 mmol), buomppH (0.518 g, 2 mmol) or ibuomppH (0.518 g, 2 mmol) was dissolved by heating in 20 mL of ethanol. To this solution, an ethanolic solution (10 mL) of bis(acetylacetonato)dioxomolybdenum(VI) (0.326 g, 1 mmol) was added. The resulting solution was refluxed for 10–12 h and then concentrated to half of its volume. The resulting precipitate was suction filtered and washed several times using 1:1 ethanol–water and dried in vacuo. The analytical data of the complexes are given in Table 3.

S. No.

Ligands

ν(C⚌O)(pyrazolone)

ν(C⚌N)(oxime)

ν(C⚌N)(pyrazolone)

ν(OH)

ν(N–O)

I

aomppH

1660

1620

1590

3200

1020

II

mppopH

1664

1656

1602

3451

1044

III

bomppH

1685

1620

1590

3040

1020

IV

ibuomppH

1685

1620

1590

3040

1020

V

bomppH

1675

1610

1590

3080

1010

2.6 Analyses

Carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen were determined micro-analytically at the Central Drug Research Institute, SAIF, Lucknow. The metal content in each chelate was determined (Maurya et al., 1993) as follows: A weighed amount (∼200 mg) of the chelate was first decomposed by heating with concentrated nitric acid and then strongly heating the residue over 800 °C for 1 h until a constant weight was obtained. The residue was weighed as MoO3.

2.7 Physical methods

Electronic spectra of the complexes were recorded in dimethylformamide on an ATI Unicam UV-2–100 UV/visible spectrophotometer in our Department. 1H NMR spectra of compounds were recorded in DMSO-d6 at Central Drug. Research Institute, SAIF, Lucknow. The solid-state infrared spectra were recorded in KBr pellets using Perkin–Elmer model 1620 FT-IR spectrophotometer at the Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee and also on FT-IR 8400S SHIMADZU at our own Department. Conductance measurements were done at room temperature in dimethylformamide using a Toshniwal Conductivity Bridge and dip type cell with a smooth platinum electrode of cell constant 1.02. Decomposition temperatures of the oxime derivatives and chelates were recorded using an electrothermal apparatus having the capacity to record temperature up to 360 °C. Thermogravimetric analyses of the samples were done at SAIF, Indian Institute of Technology, Mumbai. Mass spectra were recorded at Sophisticated Analytical Instrumentation Facility, CDRI. Lucknow. Magnetic measurement was performed by the Vibrating Sample Magnetometer method.

2.8 Molecular modeling studies

The 3D molecular modeling of a representative compound was carried out on a CS Chem 3D Ultra Molecular Modeling and Analysis Program (www.cambridgesoft.com). It an interactive graphics program that allows rapid structure building, geometry optimization with minimum energy and molecular display. It has ability to handle transition metal compounds.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Composition and characterization of the oxime derivatives

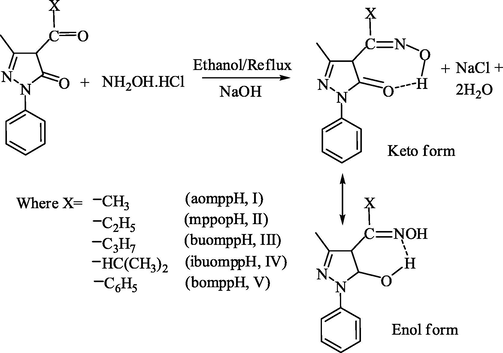

The oxime derivatives used in the present investigation were prepared as shown in reaction scheme given in Scheme 2.

Synthesis of oxime derivatives.

The compositions of the ligands are consistent with the micro-analytical data. The IR spectra of these oximino derivatives have a band at 1660–1685 cm−1, which is assigned to ν(C⚌O) (cyclic) of the pyrazolone skeleton. A strong band at 1610–1656 cm−1 in these derivatives is assigned to v(C⚌N) (oxime). Another strong band observed in all the oxime derivatives at 1590–1602 cm−1 is most probably due to ν(C⚌N) (cyclic) of the pyrazolone skeleton. All the oxime derivatives show medium/broad bands with fine structure in the range 3040–3451 cm−1, which may be due to v(OH) of the oxime group. The observed low value of v(OH) suggests the presence of intramolecular hydrogen bonding in the derivatives. A new band observed at 1010–1044 cm−1 in the oxime derivatives, unlike the parent carbonyl compound, may be assigned to v(N–O). The overall IR results conclude that all the oxime derivatives exist in ketonic form in the solid state as shown in the scheme above.

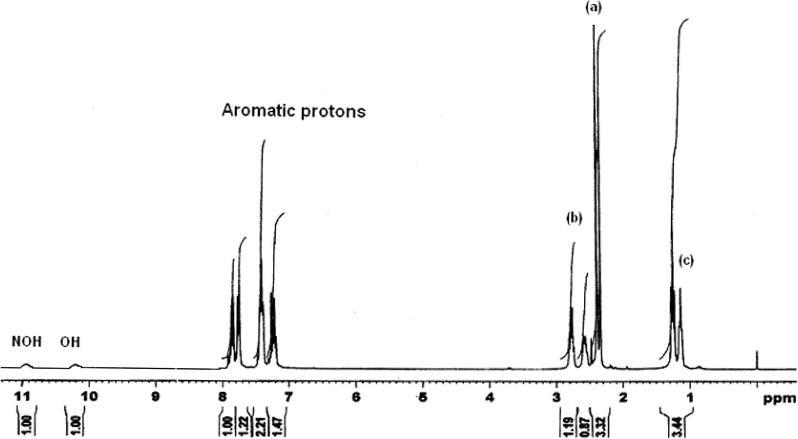

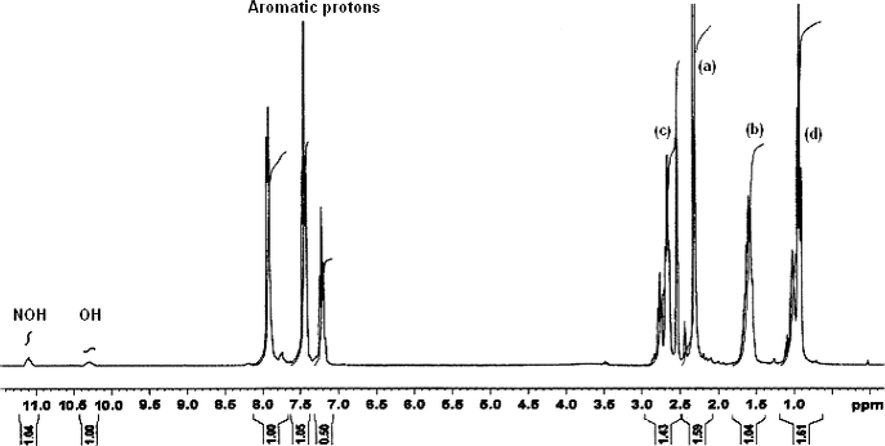

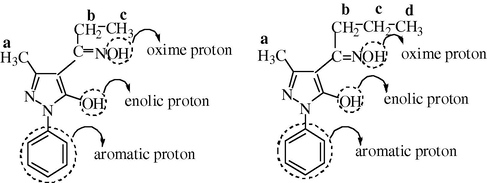

The proton NMR spectra of two representative ligands namely mppopH (II) (Fig. 4) and buomppH (III) (Fig. 5) were recorded in DMSO-d6. The proton signals due to aromatic protons of the phenyl ring in the two ligands displayed as multiplets in the region δ 7.194–7.913 and δ 7.173–7.939 ppm, respectively. The other proton signals in case of ligand (II) at δ 2.740–2.789 (quartet), δ 2.342 (singlet) and at δ 1.051–1.140 (triplet) ppm are most probably due to proton groups, such as –CH2 (b), –CH3 (a), and –CH3 (c), respectively. In case of the ligand (III) proton signals at δ 2.642–2.858 (multiplets), δ 2.317 (singlet), δ 1.576–1.623 (triplet) and δ 0.902–0.927 (triplet) ppm are due to proton groups likely to be –CH2 (c), –CH3 (a), –CH2 (b) and –CH3 (d), respectively. Both the ligands displayed two singlet proton signals at δ 10.240–10.422 and δ 10.986–11.101 ppm most probably due to enolic (OH) (cyclic) and –NOH (oxime), respectively. The indexing of various protons is given in Fig. 6.

1H NMR spectrum of mppopH (II).

1H NMR spectrum of buomppH (III).

Indexing of various protons in ligands II and III.

The presence of a proton signal at δ 10.240–10.422 ppm suggests that the ligand exist in enolic form in DMSO-d6 (solvent used for NMR). Contrary to this, all the ligands exist in ketonic form in the solid state as concluded from the IR spectral studies discussed above.

3.2 Characterization of complexes

The formation of metal chelates can be represented by the following general equation: The driving force for the reaction in order to form these chelates along with the elimination of two molecules of acetylacetone (acacH) is the better donating (Maurya et al., 2003c) capability of the oxime derivatives compared to acetylacetone anion.

The synthesized complexes are colored, non-hygroscopic and air stable solids. They are thermally stable and their decomposition temperatures are given in the Table 4. These are soluble in dimethylformamide and dimethylsulfoxide, and insoluble in all other common organic solvents. Some physical properties of the complexes are also given in Table 4. The formulations of these complexes are based on their elemental analyses, infrared spectra, magnetic measurements, NMR, mass, thermogravimetry, and electronic spectral studies.

S. No.

Complex* (empirical formula) (F.W.)

Analyses, found/(calcD.), %

Color

Decomp. temp. (°C)

Yield (%)

ΛM (Ohm−1 cm2 mol−1)

C

H

N

Mo

1

[MoO2(aomppH)2(H2O)2](C24H28N6O8Mo) (623.94)

46.04 (46.16)

4.29 (4.49)

13.25 (13.46)

15.28 (15.38)

Middle buff

210

50

11.5

2

[MoO2(mppopH)2(H2O)2](C26N32N6O8Mo) (651.94)

47.67 (47.86)

4.82 (4.91)

12.68 (12.88)

14.60 (14.72)

Daffodil

220

60

15.2

3

[MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)2](C28H36N6O8Mo) (679.94)

49.29 (49.42)

5.15 (5.29)

12.15 (12.35)

14.05 (14.11)

Yellow

240

52

14.1

4

[MoO2(ibuomppH)2(H2O)2](C28H36N6O8Mo) (679.94)

49.30 (49.42)

5.12 (5.29)

12.20 (12.35)

14.02 (14.11)

Deep green

220

50

12.4

5

[MoO2(bomppH)2(H2O)2](C34H32N6O8Mo) (747.94)

54.42 (54.55)

4.20 (4.28)

11.13 (11.23)

12.67 (12.83)

Leaf brown

200

52

10.1

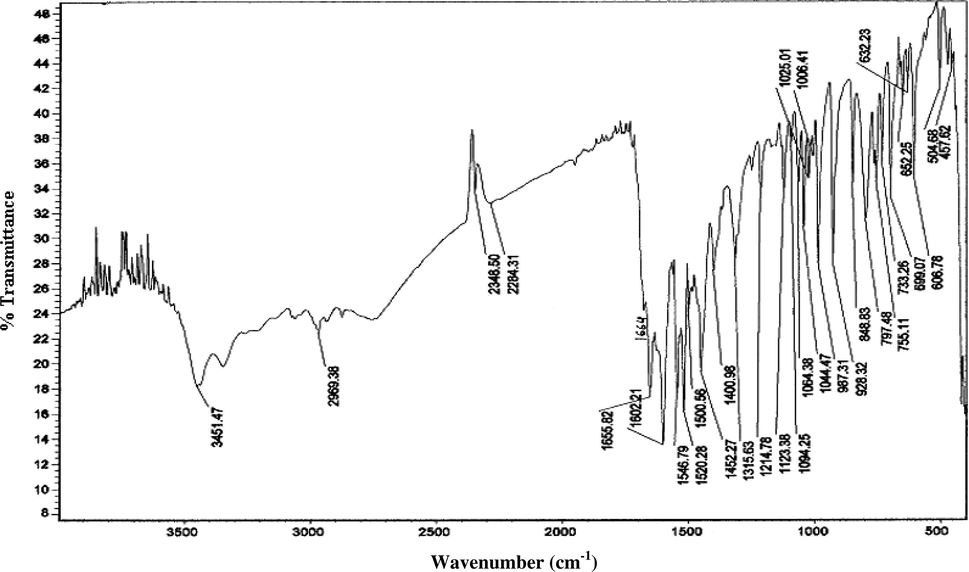

3.3 IR spectral studies

The MoO22+ moiety prefers to form a cis-dioxo grouping due to the maximum utilization of the d-orbital for bonding. The dioxo-configuration is characterized by two infrared active modes of νs(O⚌Mo⚌O) and νas(O⚌Mo⚌O) in C2V symmetry. The trans-MoO22+ moiety would exhibit a single infrared active stretching band of νas(O⚌Mo⚌O). The presence of two infrared bands in the 910–913 and 941–991 cm−1 regions due to νas(O⚌Mo⚌O) and νs(O⚌Mo⚌O), respectively, in the present complexes is strongly indicative of the cis-MoO22+ structures (Syamal and Maurya, 1989; Maurya et al., 1995a).

The coordination of oxime nitrogen is inferred by a shift to lower frequencies57 (Maurya et al., 2003d) in the ν(C⚌N) (Oxime) (1567–1578 cm−1) in all the complexes as compared to that of the free oxime derivatives at 1610–1656 cm−1. This is further supported by shifting of the ν(N–O) to a higher wave number (1073–1091 cm−1) (Yildim et al., 2003; Maurya et al., 2003d; Karatas et al., 1991c) in the complexes as compared to that of the free oxime derivatives appearing at 1010–1044 cm−1. All the oxime derivatives display a band in the region of 1590–1602 cm−1, which may be due to ν(C⚌N2) (pyrazoline ring). This band remains almost unchanged in all the metal chelates. This indicates that the ring nitrogen N2 does not take part in coordination, which is in agreement to our previous observation (Maurya et al., 2003b). The absence of a strong band at 1660–1685 cm−1 due to ν(C⚌O) and the appearance of a new band in the region of 1126–1227 cm−1 assignable to ν(C–O) (enolic), may be taken as diagnostic of coordination of cyclic oxygen to the metal center in the enol form (Kharodawala and Rana, 2003; Maurya et al., 2007) after deprotonation. The coordination of oxime nitrogen and cyclic oxygen is further supported by the appearance of two non-ligand bands at 508–517 and 430–497 cm−1 assignable to ν(M–O) and ν(M–N), respectively (Maurya et al., 2003a).

The IR spectra of all the complexes show a broad band centered at 3375–3437 cm−1. This suggests the presence of coordinated water molecules. A weak band at 1658–1724 cm−1 in the IR spectra of all the complexes can be ascribed to the inter-molecular hydrogen bonded O–H⋯O (between oxime OH group and coordinated water oxygen) bending vibration (Chakravorty, 1974). The important infrared spectral bands of the oxime derivatives and complexes in the present investigation are given in Tables 3 and 5, respectively. The IR spectra of the ligand, mppopH (II), and its complex [MoO2(mppopH)2(H2O)2] (2) are given in Figs. 7 and 8, respectively.

S. No.

Complex

νs(MoO2)

νas(MoO2)

ν(C–O) (Enolic)

ν(C⚌N) (oxime)

ν(C⚌N) (pyrazolone)

ν(OH)

δ(O–H⋯O)

ν(Mo–O)

ν(Mo–N)

ν(N–O)

1

[MoO2(aomppH)2(H2O)2]

950

910

1126

1578

1612

3401

1724

508

430

1091

2

[MoO2(mppopH)2(H2O)2]

941

913

1167

1578

1605

3437

1659

517

497

1079

3

[MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)2]

941

913

1227

1567

1605

3430

1658

512

468

1079

4

[MoO2(ibuomppH)2(H2O)2]

991

912

1221

1571

1608

3432

1708

510

456

1091

5

[MoO2(bomppH)2(H2O)2]

951

912

1164

1569

1599

3375

1686

510

450

1073

IR spectrum of mppopH (II).

![IR spectrum of [MoO2(mppopH)2(H2O)2] (2).](/content/184/2015/8/3/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2011.01.010-fig10.png)

IR spectrum of [MoO2(mppopH)2(H2O)2] (2).

3.4 1H NMR spectral studies

The 1H NMR spectrum of a representative compound [MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)2] (3) (Fig. 9) was recorded in DMSO-d6 to compare its result with the respective ligand. The absence of an enolic proton (cyclic) signal at δ 10.422 in the ligand was found to be absent in the spectrum of this complex. This shows the coordination of enolic oxygen after deprotonation to the metal center in this complex. This is in agreement with the IR spectral results related to the coordination of ligands under discussion. Other proton signals in the complex are δ 2.424 (singlet) –CH3 (a), δ 1.577–1.625 (triplet) –CH2 (b), δ 2.595–2.912 (multiplets) –CH2 (c), δ 0.916–0.969 (triplet) –CH3 (d) and δ 7.268–8.144 (multiples) (aromatic protons).![1HNMR spectrum of [MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)2] (3).](/content/184/2015/8/3/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2011.01.010-fig11.png)

1HNMR spectrum of [MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)2] (3).

Two more proton signals were observed at δ 12.501 and δ 13.173 ppm in this complex, which are most probably due to protons of hydrogen bonded coordinated water molecules, and hydrogen bonded oxime proton (Zulfikaroglu et al., 2003), respectively.

3.5 Electronic spectral studies

Electronic spectra of all the complexes were recorded in 10−3 M in dimethylformamide solutions. The electronic spectral peaks observed in each of the complexes along with their molar extinction coefficient are given in Table 6. The high intensity spectral peak in UV-region in each of the complexes is due to intra-ligand transition. A medium to weak intensity peak near 443–444 nm in complexes (2) and (4) may be due to the ligand to metal charge transfer transitions (LMCT). The nonappearance of the LMCT band in the other three complexes is most probably due to its poor intensity. The electronic spectrum of [MoO2(ibuomppH)2(H2O)2] (4) is given in Fig. 10.

S. No.

Complex

λmax (nm)

ε (l mol−1 cm−1)

Peak assignments

1

[MoO2(aomppH)2(H2O)2]

287

3444

Intra-ligand transition

328

3703

337

3777

348

3851

2

[MoO2(mppopH)2(H2O)2]

282

3461

Intra-ligand transition

307

3500

332

3576

347

3884

355

3730

444

1269

LMCT

3

[MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)2]

296

3513

Intra-ligand transition

335

4054

357

4432

4

[MoO2(ibuomppH)2(H2O)2]

269

1105

Intra-ligand transition

443

194

LMCT

5

[MoO2(bomppH)2(H2O)2]

293

3642

Intra-ligand transition

340

3607

352

3714

![Electronic spectrum of [MoO2(ibuomppH)2(H2O)2] (4).](/content/184/2015/8/3/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2011.01.010-fig12.png)

Electronic spectrum of [MoO2(ibuomppH)2(H2O)2] (4).

3.6 Thermogravimetric studies

The thermogravimetric curves of two representative compounds [MoO2(mppopH)2(H2O)2] (2) (Fig. 11) [MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)2] (3) (Fig. 12) were recorded in the temperature range of 25–1000 °C at the heating rate of 15 °C per minute. The compound (2) shows a weight loss of 5.3% at 300 °C with start of weight loss at 240 °C, corresponding to the elimination of two moles of coordinated water (calcd. weight loss for two mole H2O = 5.52%). It shows a second weight loss of 42.2% at 587 °C corresponding to the elimination of one coordinated oxime ligand group (calcd. weight loss of one oxime ligand group = 42.94%). The final weight loss (obs. = 80.0%) at 778.12 °C corresponds to the elimination of one mole oxime ligand group (calcd. weight loss = 80.37%). The final residue at ∼780 °C (obs. = 20.0%) corresponds to MoO3 (calcd. = 22.07%).![TG curve of [MoO2(mppopH)2(H2O)2] (2).](/content/184/2015/8/3/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2011.01.010-fig13.png)

TG curve of [MoO2(mppopH)2(H2O)2] (2).

![TG curve of [MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)2] (3).](/content/184/2015/8/3/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2011.01.010-fig14.png)

TG curve of [MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)2] (3).

Similar to compound (2), the compound (3) displayed the following three weight losses:

S. No.

% wt. loss (obs.)

% wt. loss (calcd.)

Elimination of

at (°C)

1

5.3

5.29

Two coordinated water molecules

300

2

43.5

43.23

One ligand group

520

3

80.0

81.16

One ligand group

725

The final residue at ∼780 °C (obs. = 21.0%) corresponds to MoO3 (calcd. = 21.03%). As the MoO3 is known to volatilize above 800 °C (melting point 795 °C (Greenwood and Earnshaw, 1984) and loose the weight, the TG plots will never be flat if these were reordered up to 1000 °C. Hence, both the TG plots appeared to be effectively recorded up to 800 °C, and so these are flat after ca. 750 °C.

3.7 Mass spectral studies

The FAB mass spectrum of a representative compound [MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)] (3) (Fig. 13) is recorded on a JEOL SX 102/DA-6000 Mass Spectrometer/Data system using argon/xenon (6 KV, 10 mA) as the FAB gas. The accelerating voltage was 10 KV and the spectrum was recorded at room temperature. m-Nitrobenzyl alcohol (NBA) was used as the matrix. The matrix peaks were supposed to appear at m/z 136, 137, 154, 289, 307 in the absence of any metal ion. If metal ions are present, these peaks may be shifted accordingly.![Mass spectrum of [MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)2] (3).](/content/184/2015/8/3/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2011.01.010-fig15.png)

Mass spectrum of [MoO2(buomppH)2(H2O)2] (3).

The mass spectral peaks observed at 136 and 154 m/z are matrix peaks. The spectral peak observed at 257, 513, 370, 387, 600, and 542 m/z are most probably due to the following types of ion associations:

-

[buomppH]+ (258) − H+ = 257

-

[buomppH]+ (258) + (Mo = O)+ (111.94) = 370

-

[buomppH]+ (258) + [O⚌Mo⚌O]+ (127.94) + H+ = 387

-

2[buomppH]+ (516) − 3H+ = 513

-

[Base peak]+ (600) − ∗[C3H7]+ (43) − ∗[CH3]+ (15) = 542

-

[Molecular ion]+ (643.94) − ∗[C3H7]+ (43) = 600 (Base peak)

∗From butyryl oxime

These results are consistent with the proposed molecular composition of the complex (3).

3.8 Conductance measurements

The molar conductivities of all the complexes in 10−3 M DMF solution are in the range 10.1–15.2 ohm−1 cm2 mol−1 (Table 4) as expected for non-electrolytes (Geary, 1971). Such a non-zero molar conductance value for each of the complexes in the present study is most probably due to the strong donor capacity of DMF, which may lead to the displacement of the anionic ligand and change of electrolyte type.

3.9 3D Molecular modeling and analysis

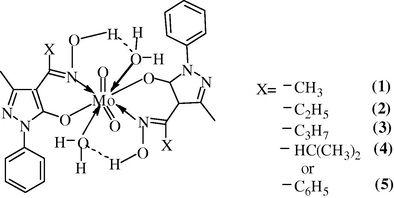

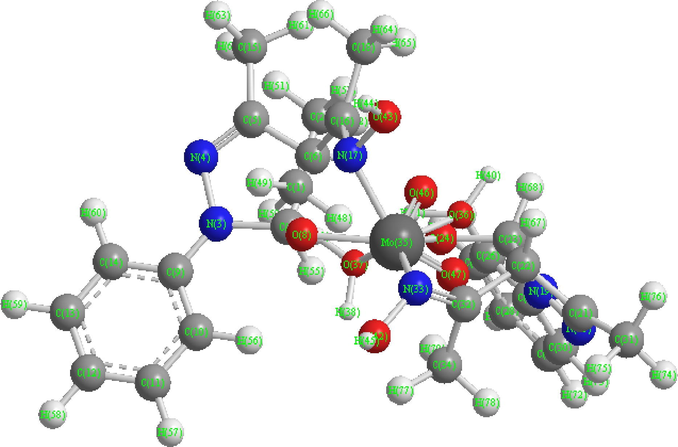

Based on the proposed structures (Fig. 15), the 3D molecular modeling of one of the representative compounds, viz., [MoO2(aomppH)2(H2O)2] (1), was carried out with the CS Chem 3D Ultra Molecular Modeling and Analysis Programme. The details of bond lengths, bond angles as per the 3D structure (Fig. 14) are given in Tables 7 and 8, respectively. For convenience of looking over the different bond lengths and bond angles, the various atoms in the compound in question are numbered in Arabic numerals. In all, 243 measurements of the bond lengths (83 in number), plus the bond angles (160 in number) are listed in the Tables 7 and 8. Except a few cases, optimal values of both the bond lengths and the bond angles are given in the Tables along with the actual ones. The observed bond lengths/bond angles given in the Tables are calculated values as a result of energy optimization in CHEM 3D Ultra [44], while the optimal bond length/optimal bond angle values are the most desirable/favorable (standard) bond lengths/bond angles established by the builder unit of the CHEM 3D. The missing of some values of standard bond lengths/bond angles may be due to the limitations of the software, which we had already noticed in the modeling of other systems (Maurya and Rajput, 2006; Maurya et al., 2008, 2010). In most of the cases, the observed bond lengths and bond angles are close to the optimal values, and thus the proposed structure of compound (1) (and also others) is acceptable (Maurya and Rajput, 2006; Maurya et al., 2008, 2010).

Proposed structure of complexes.

3D structure of compound (1).

S. No.

Atoms

Actual bond length

Optimal bond length

S. No.

Atoms

Actual bond length

Optimal bond length

1

C(2)–H(53)

1.113

1.113

43

C(22)–C(32)

1.497

1.497

2

C(2)–H(52)

1.113

1.113

44

C(22)–C(23)

1.523

1.514

3

C(2)–H(51)

1.113

1.113

45

C(21)–C(31)

1.497

1.497

4

C(1)–H(50)

1.113

1.113

45

C(21)–C(22)

1.497

1.497

5

C(1)–H(49)

1.113

1.113

47

N(20)–C(21)

1.4988

1.26

6

C(1)–H(48)

1.113

1.113

48

N(19)–C(25)

1.266

1.462

7

C(1)–C(2)

1.523

1.523

49

N(19)–C(23)

1.47

1.47

8

O(43)–H(44)

0.942

0.942

50

N(19)–N(20)

1.23

1.426

9

O(42)–H(45)

0.942

0.942

51

C(18)–H(66)

1.113

1.113

10

O(37)–H(39)

0.986

–

52

C(18)–H(65)

1.113

1.113

11

O(37)–H(38)

0.986

–

53

C(18)–H(64)

1.113

1.113

12

O(36)–H(41)

0.986

–

54

N(17)–Mo(35)

1.9741

–

13

O(36)–H(40)

0.986

–

55

N(17)–O(43)

1.316

–

13

Mo(35)–O(47)

1.5353

–

56

C(16)–C(18)

1.497

1.497

15

Mo(35)–O(46)

1.8428

–

57

C(16)–N(17)

1.377

1.377

16

O(36)–Mo(35)

1.8488

–

58

C(15)––H(63)

1.113

1.113

17

Mo(35)–O(37)

1.5202

–

59

C(15)–H(62)

1.113

1.113

18

C(34)–H(79)

1.113

1.113

60

C(15)–H(61)

1.113

1.113

19

C(34)–H(78)

1.113

1.113

61

C(14)–H(60)

1.1

1.1

20

C(34)–H(77)

1.113

1.113

62

C(13)–H(59)

1.1

1.1

21

N(33)–O(42)

1.316

–

63

C(13)–C(14)

1.337

1.42

22

N(33)–Mo(35)

1.976

–

64

C(12)–H(58)

1.1

1.1

23

C(32)–C(34)

1.497

1.497

65

C(12)–C(13)

1.337

1.42

24

C(32)–N(33)

1.6947

1.377

66

C(11)–H(57)

1.1

1.1

25

C(31)–H(76)

1.113

1.113

67

C(11)–C(12)

1.337

1.42

26

C(31)–H(75)

1.113

1.113

68

C(10)–H(56)

1.1

1.1

27

C(31)–H(74)

1.113

1.113

69

C(10)–C(11)

1.337

1.42

28

C(30)–H(73)

1.1

1.1

70

C(9)–C(14)

1.337

1.42

29

C(29)–H(72)

1.1

1.1

71

C(9)–C(10)

1.337

1.42

30

C(29)–C(30)

1.337

1.42

72

O(8)–Mo(35)

1.94

–

31

C(28)–H(71)

1.1

1.1

73

C(7)–H(55)

1.113

1.111

32

C(28)–C(29)

1.337

1.42

74

C(7)–O(8)

1.402

1.391

33

C(27)–H(70)

1.1

1.1

75

C(6)–H(54)

1.113

1.113

34

C(27)–C(28)

1.337

1.42

76

C(6)–C(16)

1.497

1.497

35

C(26)–H(69)

1.1

1.1

77

C(6)–C(7)

1.523

1.514

36

C(26)–C(27)

1.337

1.42

78

C(5)–C(15)

1.497

1.497

37

C(25)–C(30)

1.337

1.42

79

C(5)–C(6)

1.497

1.497

38

C(25)–C(26)

1.337

1.42

80

N(4)–C(5)

1.26

1.26

39

O(24)–Mo(35)

1.94

–

81

N(3)–C(9)

1.266

1.462

40

C(23)–H(68)

1.113

1.111

82

N(3)–C(7)

1.47

1.47

41

C(23)–O(24)

1.402

1.391

83

N(3)–N(4)

1.4219

1.426

42

C(22)–H(67)

1.113

1.113

S. No.

Atoms

Actual bond angles

Optimal bond angles

S. No.

Atoms

Actual bond angles

Optimal bond angles

1

H(53)–C(2)–H(52)

109.5199

109

81

O(47)–Mo(35)–O(24)

36.6947

–

2

H(53)–C(2)–H(51)

109.4619

109

82

O(47)–Mo(35)–N(17)

142.7106

–

3

H(53)–C(2)–C(1)

109.4615

110

83

O(47)–Mo(35)–O(8)

133.1707

–

4

H(52)–C(2)–H(51)

109.4419

109

84

O(46)–Mo(35)–O(37)

70.4451

–

5

H(52)–C(2)–C(1)

109.4416

110

85

O(46)–Mo(35)–O(36)

29.6984

–

6

H(51)–C(2)–C(1)

109.5005

110

86

O(46)–Mo(35)–N(33)

153.3882

–

7

H(50)–C(1)–H(49)

109.5198

109

87

O(46)–Mo(35)–O(24)

30.6141

–

8

H(50)–C(1)–H(48)

109.4619

109

88

O(46)–Mo(35)–N(17)

79.0453

–

9

H(50)–C(1)–C(2)

109.4617

110

89

O(46)–Mo(35)–O(8)

96.5432

–

10

H(49)–C(1)–H(48)

109.442

109

90

O(37)–Mo(35)–O(36)

87.443

–

11

H(49)–C(1)–C(2)

109.4416

110

91

O(37)–Mo(35)–N(33)

131.1412

–

12

H(48)–C(1)–C(2)

109.5003

110

92

O(37)–Mo(35)–O(24)

65.2425

–

13

H(72)–C(29)–C(30)

119.9998

120

93

O(37)–Mo(35)–N(17)

95.5127

–

13

H(72)–C(29)–C(28)

119.9997

120

94

O(37)–Mo(35)–O(8)

50.2039

–

15

C(30)–C(29)–C(28)

120.0004

–

95

O(36)–Mo(35)–N(33)

125.2943

–

16

H(71)–C(28)–C(29)

120.0002

120

96

O(36)–Mo(35)–O(24)

23.4196

–

17

H(71)–C(28)–C(27)

120.0002

120

97

O(36)–Mo(35)–N(17)

101.4075

–

18

C(29)–C(28)–C(27)

119.9996

–

98

O(36)–Mo(35)–O(8)

125.1198

–

19

H(70)–C(27)–C(28)

119.9996

120

99

N(33)–Mo(35)–O(24)

134.9523

–

20

H(70)–C(27)–C(26)

120.0003

120

100

N(33)–Mo(35)–N(17)

109.4999

–

21

C(28)–C(27)–C(26)

120.0001

–

101

N(33)–Mo(35)–O(8)

109.4999

–

22

H(73)–C(30)–C(29)

120

120

102

O(24)–Mo(35)–N(17)

109.5001

–

23

H(73)–C(30)–C(25)

120.0005

120

103

O(24)–Mo(35)–O(8)

109.4999

–

24

C(29)–C(30)–C(25)

119.9995

–

104

N(17)–Mo(35)–O(8)

58.7561

–

25

H(69)–C(26)–C(27)

120.0001

120

105

H(66)–C(18)–H(65)

109.5196

109

26

H(69)–C(26)–C(25)

119.9997

120

106

H(66)–C(18)–H(64)

109.4624

109

27

C(27)–C(26)–C(25)

120.0003

–

107

H(66)–C(18)–C(16)

109.4617

110

28

C(30)–C(25)–C(26)

120.0001

120

108

H(65)–C(18)–H(64)

109.4421

109

29

C(30)–C(25)–N(19)

119.9998

120

109

H(65)–C(18)–C(16)

109.4418

110

30

C(26)–C(25)–N(19)

120.0001

120

110

H(64)–C(18)–C(16)

109.4998

110

31

H(76)–C(31)–H(75)

109.5202

109

111

O(43)–N(17)–Mo(35)

109.5273

–

32

H(76)–C(31)–H(74)

109.4624

109

112

O(43)–N(17)–C(16)

109.5273

–

33

H(76)–C(31)–C(21)

109.4617

110

113

Mo(35)–N(17)–C(16)

109.1575

–

34

H(75)–C(31)–H(74)

109.4417

109

114

H(59)–C(13)–C(14)

120.0003

120

35

H(75)–C(31)–C(21)

109.4415

110

115

H(59)–C(13)–C(12)

119.9996

120

36

H(74)–C(31)–C(21)

109.4999

110

116

C(14)–C(13)–C(12)

120

–

37

C(21)–N(20)–N(19)

114.4919

115

117

H(58)–C(12)–C(13)

120.0002

120

38

C(25)–N(19)–C(23)

124.5

108

118

H(58)–C(12)–C(11)

120.0003

120

39

C(25)–N(19)–N(20)

124.4998

124

119

C(13)–C(12)–C(11)

119.9995

40

C(23)–N(19)–N(20)

111.0002

–

120

H(57)–C(11)–C(12)

119.9995

120

41

H(68)–C(23)–O(24)

108.4689

106.7

121

H(57)–C(11)–C(10)

120

120

42

H(68)–C(23)–C(22)

114.5222

109.39

122

C(12)–C(11)–C(10)

120.0005

–

43

H(68)–C(23)–N(19)

111.7232

107.5

123

H(60)–C(14)–C(13)

119.9999

120

44

O(24)–C(23)–C(22)

107.5002

107.7

124

H(60)–C(14)–C(9)

119.9996

120

45

O(24)–C(23)–N(19)

110.5003

–

125

C(13)–C(14)–C(9)

120.0005

–

46

C(22)–C(23)–N(19)

104

–

126

H(56)–C(10)–C(11)

120.0003

120

47

C(31)–C(21)–C(22)

128.9413

117.2

127

H(56)–C(10)–C(9)

119.9997

120

48

C(31)–C(21)–N(20)

128.941

115.1

128

C(11)–C(10)–C(9)

120

–

49

C(22)–C(21)–N(20)

102.1176

115.1

129

C(18)–C(16)–N(17)

120.0001

120

50

H(79)–C(34)–H(78)

109.5202

109

130

C(18)–C(16)–C(6)

120.0002

117.2

51

H(79)–C(34)–H(77)

109.4617

109

131

N(17)–C(16)–C(6)

119.9997

120

52

H(79)–C(34)–C(32)

109.4617

110

132

Mo(35)–O(8)–C(7)

109.4999

–

53

H(78)–C(34)–H(77)

109.442

109

133

H(55)–C(7)–O(8)

108.4688

106.7

54

H(78)–C(34)–C(32)

109.4417

110

134

H(55)–C(7)–C(6)

114.5224

109.39

55

H(77)–C(34)–C(32)

109.5

110

135

H(55)–C(7)–N(3)

111.7237

107.5

56

H(67)–C(22)–C(32)

107.8496

109.39

136

O(8)–C(7)–C(6)

107.5

107.7

57

H(67)–C(22)–C(23)

112.9886

109.39

137

O(8)–C(7)–N(3)

110.4999

–

58

H(67)–C(22)–C(21)

112.9885

109.39

137

C(6)–C(7)–N(3)

103.9999

–

59

C(32)–C(22)–C(23)

109.47

109.51

139

C(14)–C(9)–C(10)

119.9995

120

60

C(32)–C(22)–C(21)

109.4699

109.51

140

C(14)–C(9)–N(3)

120.0006

120

61

C(23)–C(22)–C(21)

104.0001

109.51

141

C(10)–C(9)–N(3)

120

120

62

H(45)–O(42)–N(33)

120.0002

142

H(63)–C(15)–H(62)

109.5198

109

63

C(34)–C(32)–N(33)

115.4565

120

143

H(63)–C(15)–H(61)

109.4621

109

64

C(34)–C(32)–C(22)

115.4567

117.2

144

H(63)–C(15)–C(5)

109.4618

110

65

N(33)–C(32)–C(22)

129.0868

120

145

H(62)–C(15)–H(61)

109.4423

109

66

H(39)–O(37)–H(38)

120.0001

–

146

H(62)–C(15)–C(5)

109.4415

110

67

H(39)–O(37)–Mo(35)

121.5008

–

147

H(61)–C(15)–C(5)

109.4999

110

68

H(38)–O(37)–Mo(35)

95.5876

–

148

H(54)–C(6)–C(16)

107.8498

109.39

69

H(41)–O(36)–H(40)

120.0004

–

149

H(54)–C(6)–C(7)

112.9885

109.39

70

H(41)–O(36)–Mo(35)

55.2093

–

150

H(54)–C(6)–C(5)

112.9885

109.39

71

H(40)–O(36)–Mo(35)

139.3508

–

151

C(16)–C(6)–C(7)

109.4701

109.51

72

O(42)–N(33)–Mo(35)

120.0284

–

152

C(16)–C(6)–C(5)

109.4698

109.51

73

O(42)–N(33)–C(32)

120.0282

–

153

C(7)–C(6)–C(5)

104.0001

109.51

74

Mo(35)–N(33)–C(32)

59.6129

–

154

C(9)–N(3)–C(7)

126.1086

108

75

Mo(35)–O(24)–C(23)

109.5

–

155

C(9)–N(3)–N(4)

126.1079

124

76

H(44)–O(43)–N(17)

120.0002

–

156

C(7)–N(3)–N(4)

107.7834

–

77

O(47)–Mo(35)–O(46)

65.3054

–

157

C(15)–C(5)–C(6)

124.4999

117.2

78

O(47)–Mo(35)–O(37)

83.0583

–

158

C(15)–C(5)–N(4)

124.5001

115.1

79

O(47)–Mo(35)–O(36)

41.3612

–

159

C(6)–C(5)–N(4)

111

115.1

80

O(47)–Mo(35)–N(33)

98.7039

–

160

C(5)–N(4)–N(3)

113.2158

115

4 Conclusions

The satisfactory analytical data and all the physico-chemical studies presented above suggest that the complexes under this investigation may be formulated as [MoO2(L)2(H2O)2], where LH = 4-acetyloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (aomppH), 3-methyl-1-phenyl-4-propionyloxime-2-pyrazoline-5-one (mppopH), 4-butyryloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (buomppH), 4-isobutyryloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (ibuomppH), 4-benzoyloxime-3-methyl-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one (bomppH). Considering the octa-coordination (Maurya et al., 1995b), tentative structures proposed for these complexes are shown in the Fig. 15.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to Professor R.R. Mishra, Vice-Chancellor, Rani Durgavati University, Jabalpur, MP, India, for the encouragement. Analytical facilities provided by the Central Drug Research Institute, Lucknow, India, and the Sophisticated Instrumentation Centre, Indian Institute of Technology, Roorkee and Mumbai are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Organometallics. 2003;22:2112.

- J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2000;21:5189.

- Analytical Chemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1963.

- Prog. Inorg. Chem.. 1973;18:177.

- Coord. Chem. Rev.. 1974;13:1.

- Inorg. Chem.. 1976;15:2612.

- Chem. Soc. Rev. 1996:25.

- Diehl, H. 1940. The Application of the Dioxime to Analytical Chemistry (G. Fredrick Smith Chemical Co., Columbus, Ohio). Van Nostrand, New York.

- Biochemistry. 1995;34:6218.

- Chem. Rev.. 2004;104:1175.

- Biochem. J.. 1992;282:659.

- Inorg. Chem. Commun.. 2002;5:384.

- Coord. Chem. Rev.. 1971;7:81.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1981;11:611.

- Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992;44:177.

- Chemistry of the Elements. Pergamon Press; 1984. p. 1173

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1982;12:889.

- Chem. Rev.. 1996;96:2757.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1983;13:781.

- Acta Chem. Scand.. 1959;13:1670.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1998;28:383.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1991;21:1031.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1991;21:1031.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1991;21:1031.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 2003;33:1483.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1985;14:89.

- Coord. Chem. Rev.. 1999;181:147.

- J. Mol. Cat. A: Chem.. 2010;322:55.

- Pol. J. Chem.. 1986;60:731-740.

- J. Mol. Struct.. 2006;794:24.

- Polyhedron. 1993;12:2045.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1995;25:437.

- Bull. Chem. Soc., Jpn.. 1995;68:1589.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 2003;33:817.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 2003;33:699.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 2003;33:309.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 2003;33:435.

- Maurya, R.C., Chourasia, J., Martin, M.H., Jhamb, S. 2007. Proceed. Nuclear and Radiochemistry Symposium (NUCAR-2007), Vadodara, India, CA-2, p. 187.

- Indian J. Chem.. 2008;47A:517.

- Int. J. Curr. Chem.. 2010;1:309.

- Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1975;13:91.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1995;25:1571.

- Polyhedron. 1990;9:1011.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1988;18:1559.

- Ozcelikay, A.T., Baker, D.J., Ingemba, L.N., Pottier, A.M., Henquin, J.C., Brichard, S.M. 1996. Am. J. Physiol., 270 (Endocrinol, Metab. 33), E 344.

- Pande, K.C., Patent, U.S., 1966. 3, 352, 672; Chem. Abstr. 1967, 66, 28891C.

- Indian J. Chem.. 1985;24:800.

- Macromol. Rep.. 1994;31:651.

- Macromol. Rep.. 1995;32:1161.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1995;15:859.

- Indian J. Chem. Sec. A.. 2000;39:557.

- Angew. Chem., Int. Ed.. 1976;15:417.

- J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem.. 2004;213:21.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1992;22:851.

- J. Indian Chem. Soc.. 1981;58:851.

- Indian J. Chem.. 1982;21A:176.

- Indian J. Chem.. 1982;21A:312.

- Shuter, E. 1995. M. Sc. Thesis University of British Columbia.

- J. Organomet. Chem. Rev.. 1974;64:145.

- Prog. Inorg. Chem.. 1979;22:1.

- Coughltan M.P., ed. Molybdenum and Molybdenum-Containing Enzymes. Oxford: Pergamen Press; 1979. p. :43.

- Coord. Chem. Rev.. 1989;95:183.

- Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.. 1905;46:144;.

- Ber.. 1908;41:2219.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1991;21:1083.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 1990;20:437.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 2003;33:1253.

- Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Chem.. 2003;33:625.