Translate this page into:

Surface and internal modification of composite ion exchange membranes for removal of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate from polluted groundwater

⁎Corresponding author. mohamedea@edrc.gov.eg (Mohamed E.A. Ali)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Al2O3/chitosan-multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) were created to increase the exchange capacity of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) ion-exchange membranes. The composite membranes were made by mixing Al2O3 nanoparticles into the PVDF cast solution, then applying a thin coating of chitosan functionalized carbon nano tubes (Cs-MWCNTs) to the PVDF membrane surface. The structure and characteristics of the hybrid membranes were described using XRD, SEM, IR, and TG-DTA. The Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membrane beat the other Al2O3-PVDF/Cs, Al2O3-PVDF, and PVDF membranes in terms of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate adsorption. The removal efficiency, pH solution, adsorption capacity, and desorption process of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate anions by Al2O3-PVDF and PVDF membranes were investigated. The removal effectiveness of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate, according to the testing findings, was 94.3, 65.6, and 85.78 %, respectively. The adsorption of MoO42−, PO43−, and NO3− increased as the pH increased initially until the best adsorption was achieved, and then decreased significantly as the pH increased further. The total adsorption capabilities of MoO42−, PO43−, and NO3−for the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membrane were 65.50, 61.22, and 59.77 mg/g, respectively. Using regeneration and reuse experiments for the simultaneous adsorption of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate during three consecutive cycles, the adsorption/desorption of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs was assessed. Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs offer a lot of promise when it comes to eliminating MoO42−, PO43−, and NO3−from actual wastewater samples.

Keywords

Nanocomposite

Ion-exchange membranes

Adsorption

Polluted groundwater

1 Introduction

Over the last decade, the ion-exchange (IE) process has been used for the adsorption of heavy metal ions from polluted water (Pismenskaya and Mareev 2021). Membrane-based water and wastewater treatment technologies are one of the most successful techniques for addressing water quality and scarcity issues (Khodabakhshi et al., 2012, Saidulu et al., 2021). Heavy metal removal by membrane adsorption is a relatively new method that has attracted a lot of interest recently (Chong et al., 2019). A number of studies have looked at the production of adsorptive membranes and their use in the adsorption of specific heavy metals because they have a high removal rate and efficiency, regeneration, appropriate reusability, a compact footprint, and need less space (Qalyoubi et al., 2021). The majority of polymeric materials utilised in IE membrane manufacturing are semi-crystalline polymers with excellent physical and chemical properties (Xin et al., 2016, Siekierka and Bryjak 2022). Among these polymers, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) is a good polymer for use in harsh environments and in the fabrication of microporous hydrophobic membranes for wastewater treatment (Ibrahim et al., 2020). As a result, considerable effort has been devoted to increasing IE capacity through a variety of methods, including physical adsorption or chemical coating of hydrophilic polymer layers, chemical or plasma treatment, graft polymerization of hydrophilic segments onto membrane matrix, and doping of inorganic materials (White et al., 2016, Rijnaarts et al., 2019). The use of low-cost fillers that reinforce polymeric membranes (inorganic or mixed organic and inorganic materials) as a surface modification of IE membranes has all contributed to advances in the adsorption capacity (Falina et al., 2021, Khan et al., 2021, McHugh et al., 2021).

Along with the rapid development of nanotechnology, membrane modification with nanomaterials has gotten a lot of attention because of its benefits, which include strong hydrophilicity, chemical stability, antibacterial properties, a large specific surface area, and high activity in the resulting membranes (Ariono and Wenten 2017, Alabi et al., 2018). Because of their small sizes, huge surface areas, and powerful activities, nanoparticles can boost the mechanical and thermal properties of macromolecule materials (Dzyazko et al., 2017). Different nanomaterials such as SiO2 (Sgreccia et al., 2021), Al2O3 (Zhang et al., 2018), Fe3O4 (Jafari et al., 2017), ZnO(Heidary et al., 2017), TiO2 (Xuan et al., 2019), graphene (Ali 2019), and MWCNTs (Wasim et al., 2017, Talavari et al., 2020) were incorporated into polymeric membranes to enhance their performance. (Hosseini et al., 2014) described how Al2O3 is among the most chemically stable inorganic materials, it is inexpensive, non-toxic, highly abrasive, and resistant to the oxidation/reduction reactions triggered by the chemical cleaning process. The addition of aluminium oxides with varying degrees of hydrophilicity is predicted to aid in the optimization of membrane surface properties and even the embedding process (Zhang et al., 2018, Razmgar et al., 2019).

Conducting polymers (CPs) have recently received a lot of interest from both theoretical and practical perspectives. CPs containing active functional groups can be attached to the polymer chain or physically deposited onto the surfaces of PVDF polymeric membranes in order to boost the ion exchange capacity of the membranes (Ali et al., 2016, Ali et al., 2021). Many hydrophilic polymers, such as chitosan/poly (acrylonitrile), carboxymethyl chitosan/poly (ether sulfone), chitosan/polystyrene, and polyvinyl alcohol/polypropylene, have been coated on various base membranes(Zhang et al., 2008, Ali 2018, Ali et al., 2018).

Chitosan is the hydrophilic polymer of interest in this work for altering the membrane (Ali et al., 2018). Chitosan is hydrophilic, non-toxic, biodegradable, antimicrobial, and biocompatible. It has been commonly used to improve the hydrophilicity of hydrophobic membranes(Alsuhybani et al., 2020). Only a few investigations of hydrophilic polymer coating on PVDF membranes have been published. It could be because PVDF membranes are highly hydrophobic, making coating with hydrophilic polymers challenging.

Carbon nanotubes have become a popular issue due to their exceptional performance (Qiu et al., 2010). MWCNTs cannot be distributed properly in the casting membrane solution system due to their extraordinarily high length-to-diameter ratio and very large specific surface area (Xie et al., 2005). As a result, proper surface modification is required to improve the dispersion of carbon nanotubes in the system. A thermally induced phase separation approach to create dense PVDF/MWCNT membranes with improved surface hydrophilicity and antifouling properties was studied by (Xu et al., 2014). Wang et al. also constructed an in situ mixed dual-layer CNT/PVDF membrane and discovered that the CNT/PVDF membrane had stronger electrical conductivity, higher permeability, and a fundamentally different surface chemical composition (Wang et al., 2015a, 2015b).

The purpose of this research is to combine PVDF with a cationic polymer in order to build a new form of homogeneous ion exchange membrane. This study used a straightforward phase-inversion technique to develop a novel hydrophilic PVDF composite membrane functionalized by A12O3 nanoparticles. The addition of A12O3 nanoparticles to the PVDF composite membrane was predicted to change the surface structure and improve its performance. This work also used a post-treatment to facilitate the growth of chitosan/MWCNTs nanocomposite, revealing the ability of this unique production process to modify PVDF membrane surfaces. In order to avoid MWCNT clumping and construct a network architecture within the PVDF matrix, MWCNT nanoparticles were first loaded onto the surface of chitosan using a simple phase-inversion method. PVDF and modified Chitosan–PVDF membranes were analysed using XRD, SEM, IR, and TGA. In batch investigations, the membrane's potential for phosphate, nitrate, and molybdate sorption was also assessed.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Commercial aluminium oxide NPs (M.wt = 101.96 with a particle size of 6–21 nm) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, and Polyvinylidene fluoride, PVDF, (M.Wt = 44080) produced by Alfa Aesar with a melting point of 155–160 °C was employed as a substrate in this work. Fisher Chemical provided chitosan, multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCNs) were supplied from Merck Chemicals Co., Darmstadt, Germany, and N, N- Dimethylacetamide (DMAC) at a 99.99 % as a solvent was prushed from Aldrich. Sodium nitrate (MW = 84.99), disodium hydrogenphosphate heptahydrate (MW = 268.07), ammonium molybdate (MW = 196.011), and glutaraldehyde (MW = 100.11) were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich. All of the materials and chemicals used in this study were of critical grade clarity.

2.2 Fabrication of nanocomposite Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-CNTs membranes

PVDF casting solution was made by dissolving 18 wt% PVDF polymer in DMAC solvent at 50 °C while stirring constantly until a homogeneous solution was formed. Following that, the stirring was paused to allow the gas bubbles in the dope to escape. At room temperature, the degassed dope solution was cast on a flat, and horizontal glass plate with a knife gap of 100 µm. At 25 °C, the cast film was placed immediately in a coagulation bath of distilled water containing 10% propanol for 30 min. To remove the leftover solvent, the precipitated membrane was taken from the coagulation bath and washed with running water. Finally, the wet membrane was dried in room temperature air for 24 h to yield a dry flat-sheet porous membrane. The Al2O3-PVDF membrane was made in the same manner as before, but with the addition of 0.4 g of Al2O3 NPs in 100 mL of 18% PVDF solution.

To make the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs composite membrane, 1 g of Cs was dissolved in a 2% acetic acid solution, and 50 mL of this solution (1% wt. Cs solution) was applied to the previously constructed Al2O3-PVDF membrane, which prepared previously for 30 min before being crosslinked with glutaraldehyde solution (5 %). The Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membrane was created by dissolving 0.1 g of MWCNTs in the as-prepared Cs solution and depositing it onto the PVDF surface (by making a thin film of Cs-MWCNTs solution using a casting machine). All membranes were rinsed several times with diluted acid and distilled water before drying for 24 h at room temperature in an open atmosphere.

2.3 Membranes characterization

The crystal structure and phase information of the nanocomposites were investigated using an X-ray diffraction pattern (XRD; Bruker-AXS D8 Discover diffractometer, Co-Ka source). The functional groups were determined using a Fourier transform infrared spectrophotometer (FT-IR spectrophotometer, Bruker Vector 22). The surface morphology and interlayer spacing of manufactured samples were examined using a field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, EO FESEM 1530). Thermal analysis (Thermogravimitric TGA and Differential Thermal Analysis DTA), was conceded using (a DT-60H thermal analyzer, Shimadzu, Japan).

2.4 Batch adsorption studies

The effective adsorption of molybdate (MoO42−), phosphate (PO43−), and nitrate (NO3−) on PVDF, Al2O3-PVDF, Al2O3-PVDF/Cs, and Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membranes equilibrated with a salt solution was investigated in batch testing. Around 0.1 g of each membrane was placed in 5 mL of MoO42−, PO43−, or NO3− solution (100 mg/L) in glass bottles. The glass bottles were shaken at room temperature for 24 h with a thermostatic shaker at a speed of 200 rpm to acheive equilibrium in ion transport between the bulk solution and the membrane. The solution was then filtered, and the concentration of PO43− and NO3− was measured with a UV–visible spectrophotometer at 400 nm (phosphate) and 202 nm (nitrate), respectively. The concentration of MoO42− was evaluated using inductively coupled plasma (ICP) atomic emission spectroscopy. Parameters such as solution pH, adsorption capacity, and regeneration are examined using Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs as the most efficient adsorption system. The pH of MoO42−, PO43−, or NO3− containing solutions was adjusted with 0.01 M HCl/NaOH. The following equations were used to calculate the adsorption capacity and removal efficiency:

2.5 Regeneration study

Batch adsorption/desorption investigations were utilised to study the regeneration of MoO42−, PO43− or NO3−-loaded Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs. For 270 min, 0.1 g of the membrane was treated with 100 mL of 100 mg/L MoO42−, PO43− or NO3−- solution at pH 5.0 using a thermostatic shaker at 200 rpm and room temperature. The MoO42−, PO43− or NO3−-loaded Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membrane was washed and dried before being desorbed in a 0.1 mol/L NaOH solution for 270 min. After that, the regenerated Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membrane was rinsed until the solution's pH reached 5.0. In three sequential adsorption/desorption cycles, the regenerated particles were applied using the same procedure. Eq. (3) was used to calculate the elution efficiency (E %) of MoO42−, PO43− or NO3− in each regeneration cycle as follows:

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Nanocomposite membranes characterization

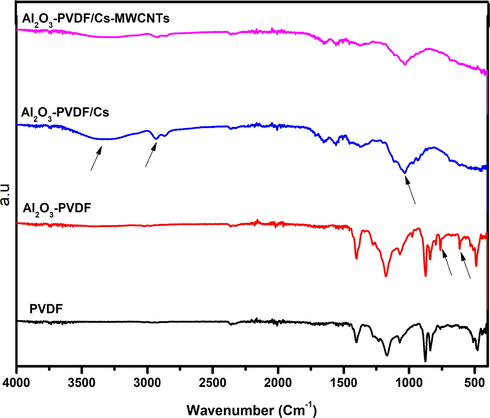

As shown in Fig. 1, AT-FTIR analysis was performed to analyse structural changes in PVDF as Alumina was added, as well as Cs and MWCNTs placed on its surface. Typical peaks of PVDF crystals nearly occurred in the PVDF spectra at 476, 612, 762.3, and 1070 cm−1, and bands at 510 and 838 cm−1 corresponded to -phase PVDF crystals. New peaks were found in the Al2O3-PVDF spectra at 613, 795, and 975 cm−1, which might be attributable to the interaction of PVDF and Al2O3.The AT-FTIR spectrum of pure Cs placed onto PVDF reveals all of the characteristic peaks of Cs at 3306, 2934, 2363, 1716, 1653, 1558, 1373, 1153, 1031, and 934 cm−1, suggesting that the deposition process was effective. The large peak at 3306 cm−1represents the stretching vibration of amino and hydroxyl groups. The C-H vibration causes the absorption peak at 2934 cm−1, whereas the carbonyl and amine stretching groups cause the absorption peaks at 1653 and 1558 cm−1, respectively. Peaks at 1373, 1031, 1153, and 934 cm−1are caused by C-H vibration, carbonyl group, and Cs saccharide structure, respectively(Cao et al., 2009). The absorption peak of pure Cs film, which showed at 3306 and 3934 cm−1 in the spectrum of Cs-MWCNTs composite, is broadened and displaced to 3275 and 2,918 cm−1 in the presence of MWCNTs. This suggests that MWCNTs carboxylic groups interacted with Cs polymer chains, and that hydrogen bonding between Cs chains was partially destructed(Mallakpour and Madani 2016). When compared to the IR spectra of the Cs film, the decrease in the intensity of amine stretching at 1558 cm-1 suggests that amino groups are protonated and interact with the carboxylic group of MWCNTs.

AT-FTIR spectra of the prepared composite membranes.

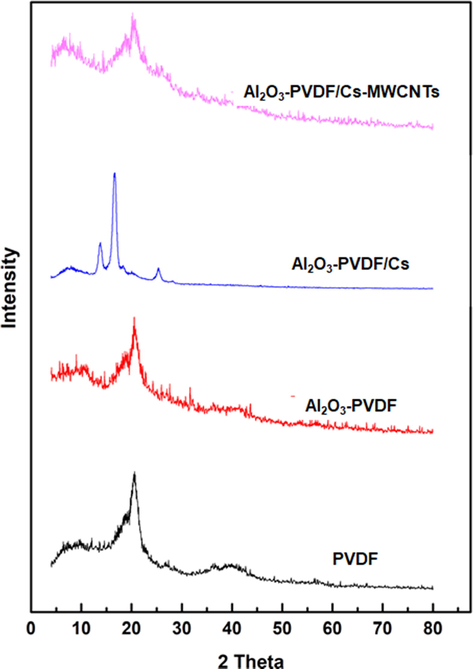

Fig. 2 shows the XRD patterns of PVDF, Al2O3-PVDF, Al2O3-PVDF/Cs, and Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs composite membranes. The emergence of a functional peak at 2 of 20.48° in the PVDF XRD pattern relates to one standard diffraction peak of PVDF (JCPDS No. 38–1638) and indicates the semi-crystalline thermoplastic polymer. The XRD pattern of Al2O3-PVDF exhibits some tiny diffraction peaks of Al2O3 at 25°, 35°, and 37°, indicating the crystallinity of Al2O3 nanoparticles. The XRD pattern of the Cs film revealed two distinct broad diffraction peaks at 13.7 and 16.5, which are typical fingerprints of semi-crystalline chitosan and are connected to a hydrated crystalline structure. The removal of these two peaks in the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs spectrum shows that CNTs caused chitosan film crystallisation.

XRD patterns of the different composite membranes.

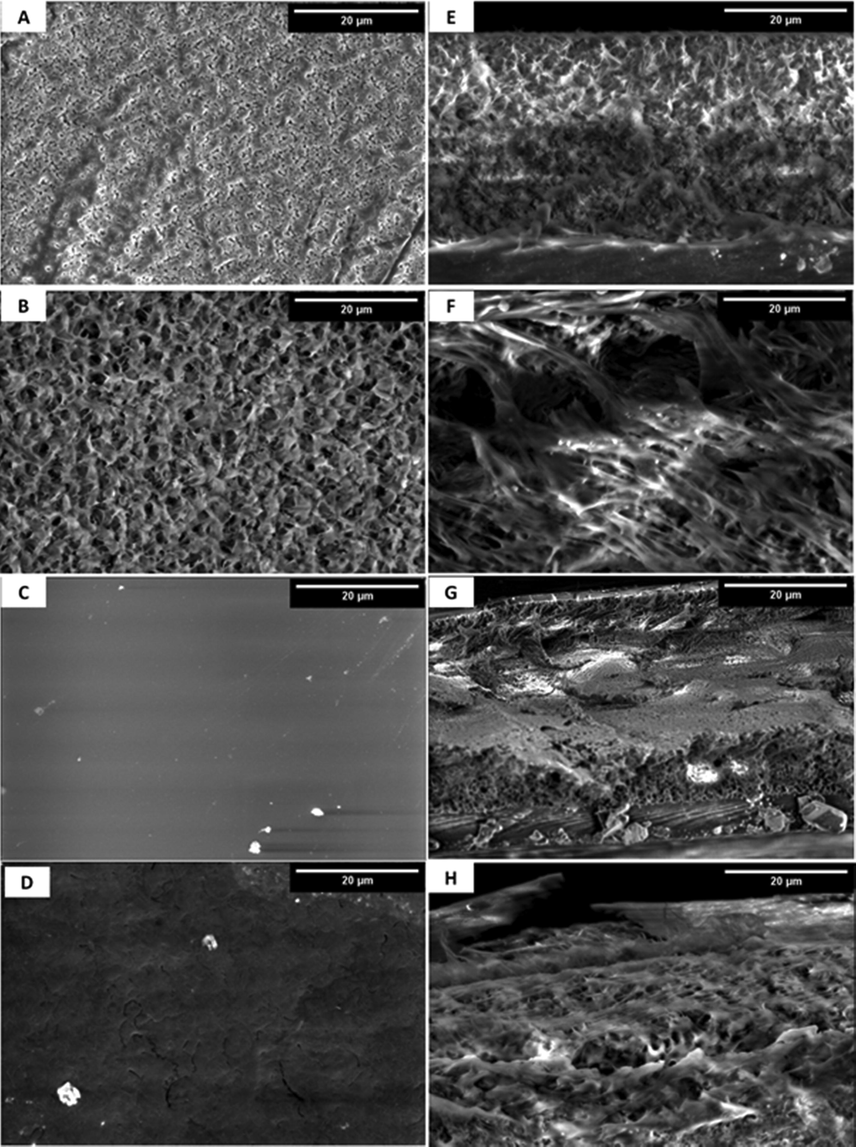

As shown in Fig. 3, surface morphology and cross-sectional structures of unmodified and modified composite membranes were investigated using SEM. Because of the Al2O3 addition, the surface characteristics, inner porous-surface structures, and intrinsic structure of the Al2O3–PVDF composite membrane differ greatly from pure PVDF (Fig. 3a, e), as illustrated in Fig. 3b,f. Both membranes showed typical asymmetric morphology with sponge structure; the latter contained large numbers of micropores. Furthermore, the Al2O3–PVDF composite membrane had well-distributed micropores on the membrane surfaces, and there were significant changes in porosity between the changed and unmodified membranes while keeping the same typical asymmetric shape. Cross-section images of PVDF and Al2O3–PVDF membranes revealed a diversity of interior morphologies. These results indicate that the addition of Al2O3 particles changes the surface, cross-section, and interior pore architectures. As a result, the inclusion of Al2O3 affected the mechanism of PVDF membrane-structure creation, which directly influences the membranes' adsorption capabilities. SEM images show that Al2O3-PVDF/Cs (Fig. 3c,g) and Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNs (Fig. 3d,h) membranes had radically distinct morphologies. When reinforced with MWCNs, SEM images of Al2O3–PVDF/Cs revealed a nonporous and smooth surface that progressed to a semi-porous and chain-like form. These photos reveal that the addition of MWCNTs to CS film led the wrinkle surface to be significantly greater than the Cs surface.

SEM images of A) PVDF, B) Al2O3-PVDF, C) Al2O3-PVDF/Cs, and D) Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs and their cross-sections (E-H), respectively.

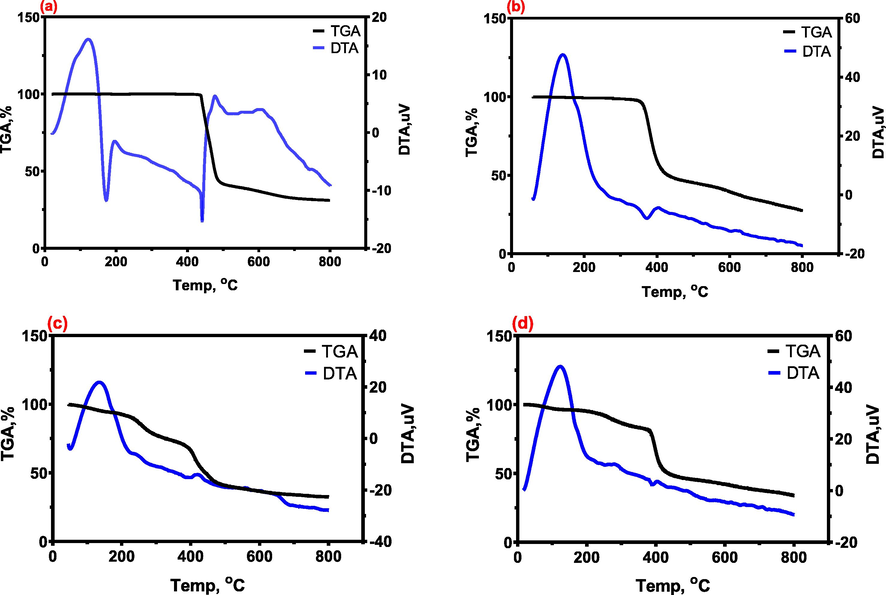

To explore the interactions between membrane components, thermal analysis (TGA-DTA) was performed. The PVDF composite membranes were subjected to thermal analysis (TGA-DTA) to study the interaction between the polymer and the inorganic particles. TGA-DTA is used to investigate the thermal stability of PVDF membranes. To compare thermal stability, the TG curves of pure PVDF, Al2O3-PVDF, Al2O3-PVDF/Cs, and Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs membranes are shown in Fig. 4. For pure PVDF, a two-stage weight loss is documented; the first weight loss (60.06 %) at 441.3 °C should be attributed to the loss of constitutional water in parallel with the transformation to crystalline nature; thus, the released energy is attributable to this transmutation (Hernandez et al., 2000). The oxidative breakdown of the residues is responsible for the second loss stage (441.3–900 °C), which results in a total weight loss of 68.69 %. The differential thermal analysis (DTA) curve has two endothermic peaks that correspond to the weight-loss stages in the TGA curve. The Al2O3-PVDF membrane's TG curve is roughly the same as that of pure PVDF, and there are two deterioration steps at 200–371.97 °C and 371.97–900 °C. Due to dehydration, the DTA curve of Al2O3-PVDF (Fig. 4) exhibits a prominent and broad endothermic peak at temperatures ranging from 180 °C to 371.9 °C. The exothermic peak in the 180 °C temperature range could be generated by the compound changing from amorphous to crystalline and the formation of the matching metal oxides. At around 900 °C, however, there is a difference in weight loss between the PVDF beads (68.69%) and the Al2O3-PVDF (72.62%). The lower thermal stability could be attributed to flaws on the Al2O3-PVDF surface as well as contaminants such as residual metallic catalysts(Ma et al., 2012). This showed that the inclusion of Al2O3 nanoparticles had no effect on crystal formation while having a modest effect on crystal perfection during the creation of PVDF membranes (Lin et al., 2003). However, by incorporating chitosan into the surface of the Al2O3-PVDF membrane (Al2O3-PVDF/Cs), the thermal stability was improved, and a four-stage weight loss was recorded at 50–137 °C, 137–223.5 °C, 223.5–420.78 °C, and finally 420.78–900 °C, with a total weight loss of 67.53 %, which indicates that the existence of MWCNTs could enhance the thermal stability of at high temperatures. This may result from the formation of the electrostatic interaction between MWCNTs and CS lattices, which restricts CS motivation (Li et al., 2012). The combustion of Cs is attributed to a minor exothermic peak in the DTA curve with a maximum weight loss velocity of roughly 420.7 °C due to water (Shao et al., 2011). Furthermore, the thermal stability of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membranes was improved by including MWCNT into chitosan solution, because the TGA curve of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs contains four stages of weight loss: 50–122.99 °C, 122.99–282.99 °C, 282.99–390.47 °C, and 390.47–900 °C, for a total weight loss of TGA study revealed that adding a modest number of MWCNTs to the Cs matrix improved the thermal stability of Cs. The combustion of MWCNTs and Cs is attributed to a minor endothermic peak in the DTA curve with a maximum weight loss velocity of roughly 390.4 °C.

TGA and DTA curves of a) PVDF, b) Al2O3-PVDF, c) Al2O3-PVDF/Cs, and d) Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs with heating rate of 20 °C/min.

3.2 Adsorption of MoO42−, PO43− and NO3−

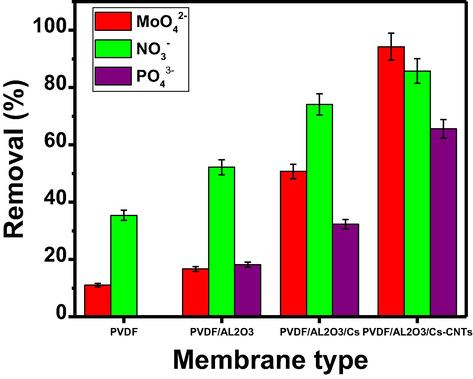

The removal values of different anions (MoO42−, PO43− or NO3− ions) on PVDF, Al2O3-PVDF, Al2O3-PVDF/Cs, and Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membranes are disclosed in Fig. 5. From the results shown in Fig. 5, the order of the adsorption efficiency of the ions on the different membranes was as follows: Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs > Al2O3-PVDF/Cs > Al2O3-PVDF > PVDF. The order of adsorption of ions on the PVDF was as follows: NO3− > MoO42− > PO43−, and on Al2O3-PVDF is: NO3− > PO43− > MoO42−, on Al2O3-PVDF/Cs is NO3− > MoO42− > PO43−. The Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membrane was the most efficient of these membranes for adsorption, and the order of the ions on it was: MoO42− > PO43− > NO3−. The membrane Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs was more efficient in adsorbing different ions due to the presence of active groups such as hydroxy and amino groups on the surface of chitosan, and the high surface area and porosity of carbon nanotubes. The NO3− was more adsorbed than MoO42− and PO43−, perhaps because the monovalent NO3− was easy to absorb on the three membranes, or the size of the NO3− particles was appropriate for the surface of the three membranes, so the adsorption of nitrate was greater than that of MoO42− and PO43−. But with the addition of MWCNTs, the surface area and porosity were increased, and it was easier to bond with MoO42− and PO43− than with NO3−. While on Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membrane, MoO42− was found more adsorbed than PO43− and NO3−. The more adsorbed MoO42− is due to the π-π and electrostatic interactions between the surface of MWCNTs and the molybdate ions. So, the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membrane was used for further studies.

The removal efficiency of MoO42−, PO43− or NO3− on different membranes.

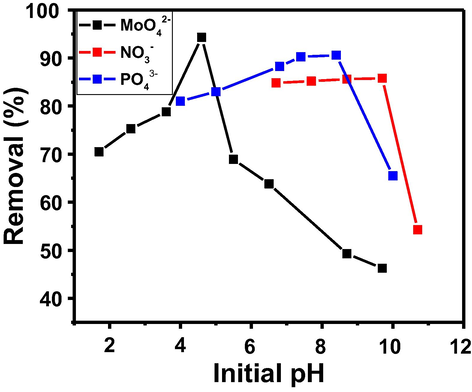

The acidity and alkalinity of the solution played a vital role not only in the dissociation of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate but also in the physicochemical interactions between the solid–liquid interfaces throughout the adsorption experiments. Fig. 6 depicts the effect of different solution pH ranging from 1.7–9.7, 4–10, and 6.7–10.7 on the removal of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate ions on the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membrane. The surface chemistry of the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs is related to the presence of functional groups such as hydroxyl group and nitrogen-containing functional groups, or π electrons on the chitosan layer and high porosity and surface area of MWCNTs (Ali et al., 2020). Depending on the conditions, such as the pH and solvent characteristics, these functional groups can be dissociated or protonated, thereby inducing attractive or repulsive interactions with the ions in the solution (Sun et al., 2017). As the strength of the interactions between ions and functional groups is not the same for all ions, we observe an effect on the preferential adsorption of ions (Ota et al., 2013). For a solution with a lower pH, the negatively charged toxic anions were networked with the positive charge of the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs, causing an increase in the electrostatic interactions. The hindered adverse molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate removal in basic solutions may be ascribed to the electrostatic repulsion of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs and energetic competition by OH− ions. These results suggest that electrostatic attraction is predominantly responsible for adsorption systems (Long et al., 2011).

Effect of solution pH for PVDF/Al2O3/Cs- MWCNTs on the removal percentage of molybdate, phosphate and nitrate ions. (Conditions: Initial concentration: 100 mg/L; Contact time: 240 min; Dose: 100 mg and Volume: 5 mL).

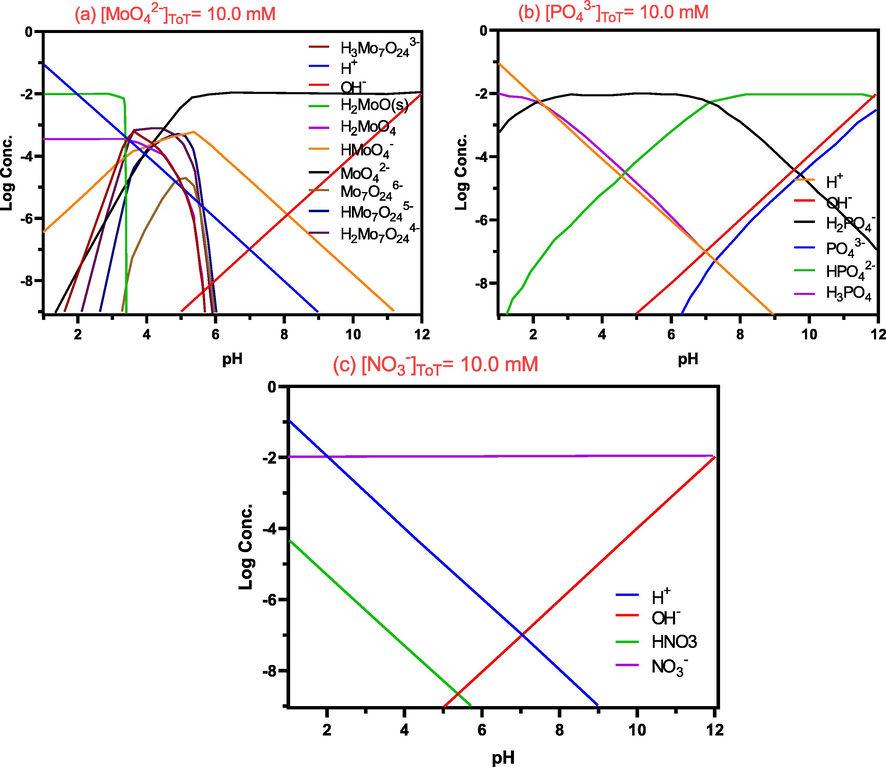

In Mo(VI), as the pH was increased, the percent adsorption increased to a maximum at pH 4.6 and, then decreased with the increasing pH. A similar trend for Mo(VI) adsorption was also observed in other different adsorbents (Namasivayam and Sangeetha 2006). The effect of pH might be related to the molybdenum morphology and the surface charge of the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs. The principal molybdate species altered with the change of pH and molybdate concentration, according to the molybdate speciation curves derived from the MEDUSA software calculation, Fig. 7. In particular, in the pH range of 2.0–10 at 100 mg/L, MoO42− may be converted to other species, such as MoO3(H2O)3, HMoO4− (Fig. 6), which are more suitable for adsorption by electrostatic contact. The aluminium surface's hydroxyl groups can be protonated, resulting in a positively charged surface that can attract and bind negatively charged molybdate ions from the solution (Al-Dalama et al., 2005). Increased pH values resulted in an increase in electrostatic repulsion between negative charge anions and Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs, resulting in a negative charge potential. The predominant mechanism for Mo(VI) adsorption in acid solution was electrostatic interaction (Zhang et al., 2014).

The speciation curves of (a) molybdate, (b) phosphate and (c) nitrate at different pH values.

As seen in Fig. 7, the influence of solution pH on the dissociation of phosphate ions from their various forms follows the sequence of monovalent (H2PO4−, pKa > 2.16), divalent (HPO42−, 7.20 < pKa < 12.35), and trivalent (PO43−, pKa > 12.35)(Wang et al., 2015a, 2015b). In acidic conditions (pH 2–3), it was discovered that the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs had a screening effect on the solution and consumed few adsorbate ions. As shown in Fig. 6, the removal ratio of toxic ions increased as the pH increased from 4 to 7, and the best solution pH range for anion adsorption by Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs was 7.5–8.5. Phosphates are generally found as a monovalent anion in this pH range. When the pH of the solution rises above 7, the phosphate reverts to a divalent state, increasing the electrostatic force of contact with Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs (Rodrigues and da Silva 2010). The phosphate adsorption was expected to decrease gradually as the pH was raised above 8.5. It was also found that as the solution pH rises, the surface of the membrane becomes negatively charged, and the negatively charged phosphate and OH– ions compete for active adsorption sites on the surface of the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs, resulting in electrostatic repulsion and, as a result, decreased adsorption. Furthermore, as the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs surface acquires a greater negative charge, electrostatic repulsion between the anions' adsorbent surfaces occurs (Nehra et al., 2019). Also, the nitrate adsorption increased drastically as the initial pH increased, till reached the best adsorption at pH 9.7, and then drastically decreased with further increases in pH as shown in Fig. 6. This behaviour can be explained by the fact that in a highly acidic solution, the surface of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs would be highly protonated, and the active sites on the surface would be surrounded by H+ ions (Kilpimaa et al., 2015). An increase in electrostatic interactions was observed for a solution with a lower pH, due to positive charges of the adsorbent connecting with negatively charged nitrate anions. Under alkali conditions, the competition between nitrate and OH− becomes stronger at high pH, resulting in decreased adsorption(Mubita et al., 2019).

The repeating adsorption capacity of MoO42−, PO43− and NO3− was measured for conducted 200 mg of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs with10 mL of 500 mg/L of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate solutions for 24 h for three times. The total capacities of MoO42−, NO3− and PO43− were 65.50, 61.22, and 59.77 mg/g, respectively. The Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs have a much higher molybdate adsorption capacity than phosphate and nitrate. Molybdate adsorption capacity on Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs is also higher than ZnCl2 activated carbon (18.9 mg/g).

Table 1 shows a comparison of various adsorbent materials for the adsorption of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate ions from aqueous solutions. The Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs membrane excelled over other adsorbents in terms of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate adsorption. Furthermore, after three consecutive cycles, the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs membrane effectively and selectively adsorbs molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate, highlighting its wide range of applications. For molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate removal, the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs membrane was shown to have a high removal efficiency, low cost, and great re-generation. Furthermore, the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs strong surface reactivity can improve the absorption efficiency of hazardous anions from a variety of water sources.

Adsorbent

Adsorption capacity (mg g−1)

Reference

Molybdate

Phosphate

Nitrate

Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs

65.50

59.77

61.22

Present study

Goethite

25.9

–

–

(Xu et al., 2006)

Industrial Solid Waste Fe(III)/Cr(III) Hydroxide

6.70

–

–

(Namasivayam and Prathap 2006)

ZnCl2 activated carbon

16.54

–

–

(Namasivayam and Sangeetha 2006)

Mg–Al- MAA LDH

–

–

8.89

(Kotp et al., 2019)

Ammonium functionalized MCM-48

–

39.70

34.80

(Hamoudi et al., 2007)

PVDF membrane

–

15.58

9.66

(Gao et al., 2019)

Amine functionalized beads

–

42.95

38.40

(Aswin Kumar and Viswanathan 2018)

MCM-48 silica gel

–

39.70

34.80

(Saad et al., 2007)

Biomass

–

30.20

11.20

(Kilpimaa et al., 2015)

Fe0-activated carbon

–

1.75

4.60

(Khalil et al., 2017)

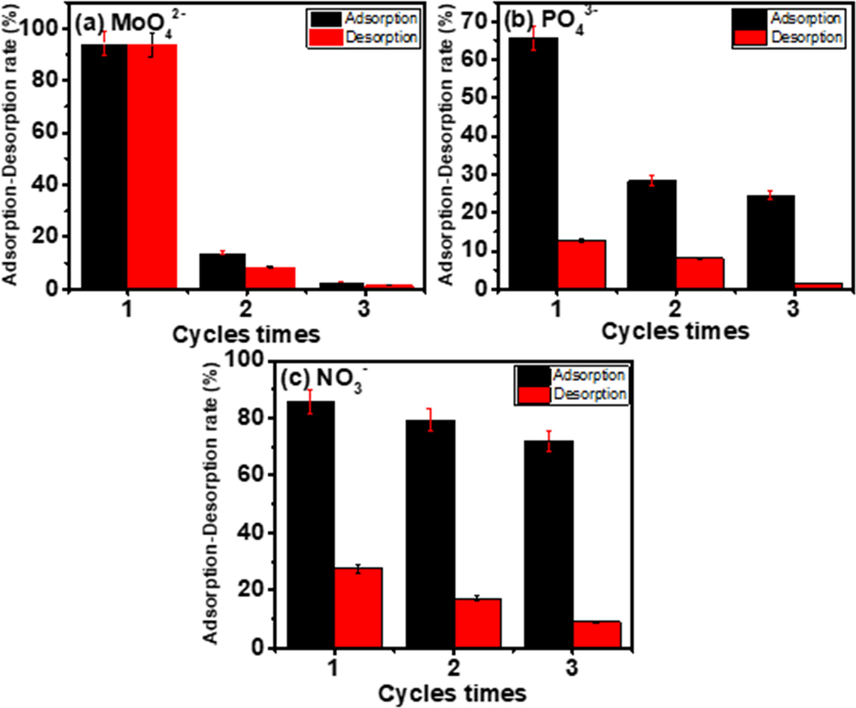

3.3 Regeneration and reuse

It is important to regenerate the spent Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs to make the adsorption process more cost-effective. Over three successive cycles, regeneration and reuse investigations were carried out for the simultaneous adsorption of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate, Fig. 8. In the desorption procedure, a 0.1 M sodium hydroxide solution was chosen as the eluent, and its optimum concentration was determined to be 100 mg/L. As shown in Fig. 8, after the first regeneration of the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs, the adsorption capacities of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate decreased to 85.2%, 56.8%, and 7.5%, respectively. Although the adsorbed molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate anions were not completely eluted by the NaOH solution, the removal efficiency of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs for molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate for the three uses was 2.8%, 24.58%, and 72%, respectively. The molybdate anions had more regeneration using NaOH than phosphate and nitrate. Therefore, Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs are a promising adsorbent for the treatment of actual contaminated water. The regeneration efficiency of the membrane is low due to the adsorbed nitrate or phosphate anions were not completely eluted by the NaOH solution. Also, the original material was covered and filled with adsorbed anions, micropore blockage, and reduced surface area (Wu et al., 2019). To get the best reuse, a number of elutions can be used, and the best one can be chosen. Secondary washing of the adsorbent with an acid such as hydrochloric to reactivate the functional groups of the absorbent and make it more efficient.

Regeneration and reuse studies of (a) molybdate, (b) phosphate and (c) nitrate on PVDF/Al2O3/Cs-MWCNTs membrane.

3.4 Adsorption mechanism

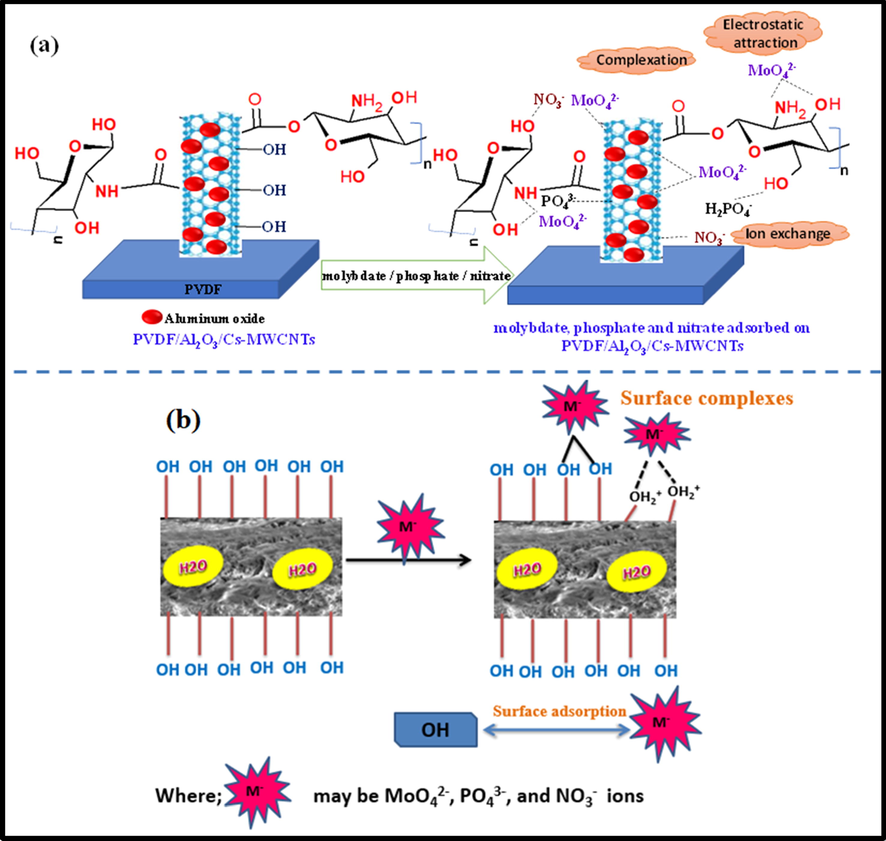

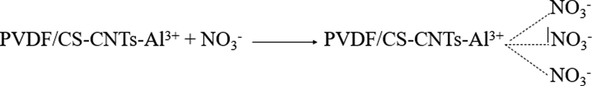

The molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate removal mechanisms are governed by the response of respective metal ions, the porous surface, and surface functional groups of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs. Negatively chartered molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate ions were absorbed by Al2O3, MWCNTs, and amino groups included in the produced membrane via electrostatic force of attraction(Banu et al., 2020). Electrostatic attraction, ion exchange, and surface complexations were used to control the adsorption of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate ions using Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs, Fig. 9(a,b). The ion exchange and electrostatic attraction mechanisms replace the harmful ions in the water with the amine (NH2) and hydroxyl (OH−) ions present in Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs during adsorption (represented as Eqs. (1)–(4)) (Karthikeyan et al., 2021).

(a, b) Schemastic representation mechanism of molybdate, phosphate and nitrate adsorption onto PVDF/Al2O3/Cs-MWCNTs.

The presence of positively charged Al3+ ions in the prepared Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs has a strong tendency to electrostatically attract negatively charged species such as molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate ions. Furthermore, due to their Lewis acid and basic behaviour, Al3+ has a strong attraction for anions and generates surface complexation. As a result, molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate can form surface complexes with Al3+ of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs, resulting in enhanced elimination of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs (Eqs. (1)–(7)) (Khan and Singh 1987, Karthikeyan and Meenakshi 2021).

3.5 Polluted groundwater treatment

El-Saff area is located on the eastern side of the Nile River in Egypt. It is bounded by a lot of sources of contamination, such as the Helwan area, which includes many factories for iron, steel, and cement production; the El-Saff wastewater canal, and polluted agricultural drainage water. The majority of water resources in El Saff area are contaminated by different types of pollutants, which are very serious for people's health, animals, soil, and plants (Gedamy et al., 2012). The high concentrations of Al3+ and Pb2+ ions in the majority of groundwater confirm that there is seepage from surface water systems that contain relatively high soluble metals as well as excess amounts of irrigation water infiltration rich in fertilisers and pesticides to the groundwater system. The relatively high concentrations of boron in El-Saff wastewater canal are due to the discharge of sewage water and industrial waste rich in sodium tetraborate (borax). The primary sources of nitrates in groundwater are the leaching of nitrate salts into the groundwater aquifer from agricultural fertilisation and the seepage of sewage water. The high concentration of ammonia in groundwater is due to the seepage from El Saff wastewater canal at these localities and irrigation return flow rich in ammonium fertilisers such as ammonium phosphate (NH4)3PO4.

The analytical results confirm that Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs can be used to remove the excess of Al3+, B3+, Mo3+, Pb2+, Sr2+, PO43− and NO3− from polluted water resources in the area under investigation. The removal efficiency reached 100% in respect to Al3+, Pb2+ and PO43−, and 50%, 62%, 52.5% and 49% in respect to B3+, Mo3+, Sr2+ and NO3−, respectively, Table 2.

Analytical parameter (mg/l)

Before Treatment

After Treatment

EC

1224

786.8

PH

6.6

7.65

Na+

128

104

K+

8

8

Mg2+

38.8

19.6

Ca2+

41.60

16.64

CO32−

0.00

0.00

HCO3−

146.4

97.6

SO42−

148

116

Cl−

228

152

Al3+

0.04

0.00

B3+

0.8

0.4

Mo3+

2.39

0.9

Pb2+

0.24

0

Sr2+

1.6

0.76

PO43−

1.92

0

NO3−

16.28

8.32

4 Conclusions

The Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs adsorbent was successfully constructed in this study to effectively remove molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate from ground polluted water. Adsorption tests show that the adsorption efficiency of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate is 94.3, 65.6, and 85.78 percent, respectively. The pH of the solution was critical not only in the dissociation of molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate but also in the physicochemical interactions between the solid–liquid interfaces throughout the adsorption investigations. Furthermore, the adsorption experiment findings show that the optimal adsorption conditions for MoO42−, PO43−, and NO3− are about 4.6, 7.4, and 7.7, respectively. Molybdate adsorption capability of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs is greater than that of phosphate and nitrate. The adsorption methods for molybdate, phosphate, and nitrate were comparable and included not only physical electrostatic interactions and complexation adsorption, but also ion exchange between the molybdate/phosphate/nitrate and hydroxyls coated on the adsorbent. The adsorption–desorption cycle experiment supports the Al2O3-PVDF/Cs-MWCNTs adsorbent's good regeneration performance. The strong surface reactivity of Al2O3-PVDF/Cs- MWCNTs is easy to make, has a good application, and is convenient to use in the separation and removal of MoO42−, PO43−, and NO3− from wastewater solutions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all of the staff and colleagues at the Hydrogeochemistry Department, Desert Research Center, Al-Matariya and Hot Laboratories, and Waste Management Center, Egyptian Atomic Energy Authority (EAEA), Cairo, Egypt. The authors would like to thank the Academy of Scientific Research and Technology for their funding through the project No. 4369.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Influence of complexing agents on the adsorption of molybdate and nickel ions on alumina. Appl. Catal. A. 2005;296:49-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review of nanomaterials-assisted ion exchange membranes for electromembrane desalination. npj Clean. Water.. 2018;1:1-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proton Exchange Membrane Based on Graphene Oxide/Polysulfone Hybrid Nano-composite for Simultaneous Generation of Electricity and Wastewater Treatment. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2021;126420

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficient Enrichment of Eu 3+, Tb 3+, La 3+ and Sm 3+ on a Double Core Shell Nano Composite Based Silica. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater.. 2020;30:1537-1552.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and adsorption properties of chitosan-CDTA-GO nanocomposite for removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solutions. Arabian J. Chem.. 2018;11:1107-1116.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of graphene nanosheets by electrochemical exfoliation of a graphite-nanoclay composite electrode: Application for the adsorption of organic dyes. Colloids Surf., A. 2019;570:107-116.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improving the performance of TFC membranes via chelation and surface reaction: applications in water desalination. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2016;4:6620-6629.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chitosan nanoparticles extracted from shrimp shells, application for removal of Fe (II) and Mn (II) from aqueous phases. Sep. Sci. Technol.. 2018;53:2870-2881.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, Characterization, and Evaluation of Evaporated Casting MWCNT/Chitosan Composite Membranes for Water Desalination. J. Chem.. 2020;2020

- [Google Scholar]

- Surface modification of ion-exchange membranes: Methods, characteristics, and performance. J. Appl. Polym. Sci.. 2017;134:45540.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development and reuse of amine-grafted chitosan hybrid beads in the retention of nitrate and phosphate. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2018;63:147-158.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorptive performance of lanthanum encapsulated biopolymer chitosan-kaolin clay hybrid composite for the recovery of nitrate and phosphate from water. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2020;154:188-197.

- [Google Scholar]

- The enhanced mechanical properties of a covalently bound chitosan-multiwalled carbon nanotube nanocomposite. J. Appl. Polym. Sci.. 2009;113:466-472.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorptive membranes for heavy metal removal–A mini review. In: AIP Conference Proceedings, AIP Publishing LLC. 2019.

- [Google Scholar]

- Composite membranes containing nanoparticles of inorganic ion exchangers for electrodialytic desalination of glycerol. Nanoscale Res. Lett.. 2017;12:1-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Permselectivity of cation exchange membranes modified by polyaniline. Membranes.. 2021;11:227.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrafiltration membrane microreactor (MMR) for simultaneous removal of nitrate and phosphate from water. Chem. Eng. J.. 2019;355:238-246.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pollutants detection in water resources at El Saff Area and their impact on human health, Giza Governorate. Egypt. Int. J. of Envir.. 2012;1:1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorptive removal of phosphate and nitrate anions from aqueous solutions using ammonium-functionalized mesoporous silica. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2007;46:8806-8812.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel sulfonated poly phenylene oxide-poly vinylchloride/ZnO cation-exchange membrane applicable in refining of saline liquids. J. Cluster Sci.. 2017;28:1489-1507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of ternary compound Ba3Li2Ti8O20 by the sol–gel process. Mater. Lett.. 2000;45:340-344.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical characterization of mixed matrix heterogeneous cation exchange membrane modified by aluminum oxide nanoparticles: mono/bivalent ionic transportation. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng.. 2014;45:1241-1248.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of novel polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)-Tin (IV) oxide (SnO2) ion exchange mixed matrix membranes for the removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions. Sep. Purif. Technol.. 2020;250:117250

- [Google Scholar]

- Ionic behavior modification of cation exchange ED membranes by using CMC-co-Fe 3 O 4 nanoparticles for heavy metals removal from water. J. Iran. Chem. Soc.. 2017;14:1011-1021.

- [Google Scholar]

- Two-dimensional (2D) Ti3C2Tx MXene nanosheets with superior adsorption behavior for phosphate and nitrate ions from the aqueous environment. Ceram. Int.. 2021;47:732-739.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of sodium alginate@ ZnFe-LDHs functionalized beads: Adsorption properties and mechanistic behaviour of phosphate and nitrate ions from the aqueous environment. Environ. Chem. Ecotoxicol.. 2021;3:42-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimized nano-scale zero-valent iron supported on treated activated carbon for enhanced nitrate and phosphate removal from water. Chem. Eng. J.. 2017;309:349-365.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption thermodynamics of carbofuran on Sn (IV) arsenosilicate in H+, Na+ and Ca2+ forms. Colloids Surf.. 1987;24:33-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of DMEA-Grafted Anion Exchange Membrane for Adsorptive Discharge of Methyl Orange from Wastewaters. Membranes.. 2021;11:166.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation, optimization and characterization of novel ion exchange membranes by blending of chemically modified PVDF and SPPO. Sep. Purif. Technol.. 2012;90:10-21.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physical activation of carbon residue from biomass gasification: Novel sorbent for the removal of phosphates and nitrates from aqueous solution. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.. 2015;21:1354-1364.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development the sorption behavior of nanocomposite Mg/Al LDH by chelating with different monomers. Compos. B Eng.. 2019;175:107131

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of MWCNTs doping on the morphology, structure and properties of chitosan beads. J. Macromol. Sci., Part A. 2012;49:674-679.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of salt additive on the formation of microporous poly (vinylidene fluoride) membranes by phase inversion from LiClO4/water/DMF/PVDF system. Polymer. 2003;44:413-422.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of phosphate from aqueous solution by magnetic Fe–Zr binary oxide. Chem. Eng. J.. 2011;171:448-455.

- [Google Scholar]

- Crystallization and mechanical properties of functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes/polyvinylidene fluoride composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos.. 2012;31:1417-1425.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, structural characterization, and tensile properties of fructose functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes/chitosan nanocomposite films. J. Plast. Film Sheeting. 2016;32:56-73.

- [Google Scholar]

- An Investigation of a (vinylbenzyl) trimethylammonium and N-vinylimidazole-substituted poly (vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) copolymer as an anion-exchange membrane in a lignin-oxidising electrolyser. Membranes.. 2021;11:425.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selective adsorption of nitrate over chloride in microporous carbons. Water Res.. 2019;164:114885

- [Google Scholar]

- Uptake of molybdate by adsorption onto industrial solid waste Fe (III)/Cr (III) hydroxide: kinetic and equilibrium studies. Environ. Technol.. 2006;27:923-932.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of molybdate from water by adsorption onto ZnCl2 activated coir pith carbon. Bioresour. Technol.. 2006;97:1194-1200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metal organic frameworks MIL-100 (Fe) as an efficient adsorptive material for phosphate management. Environ. Res.. 2019;169:229-236.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of nitrate ions from water by activated carbons (ACs)—Influence of surface chemistry of ACs and coexisting chloride and sulfate ions. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2013;276:838-842.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ion-Exchange Membranes and Processes (Volume II) Multidiscip. Digit. Publish. Instit.. 2021;11:816.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent progress and challenges on adsorptive membranes for the removal of pollutants from wastewater. Part I: Fundamentals and classification of membranes. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng.. 2021;3:100086

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and pervaporation property of chitosan membrane with functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2010;49:11667-11675.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and characterization of a novel hydrophilic PVDF/PVA/Al2O3 nanocomposite membrane for removal of As (V) from aqueous solutions. Polym. Compos.. 2019;40:2452-2461.

- [Google Scholar]

- Layer-by-layer coatings on ion exchange membranes: Effect of multilayer charge and hydration on monovalent ion selectivities. J. Membr. Sci.. 2019;570:513-521.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thermodynamic and kinetic investigations of phosphate adsorption onto hydrous niobium oxide prepared by homogeneous solution method. Desalination. 2010;263:29-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of phosphate and nitrate anions on ammonium-functionalized MCM-48: effects of experimental conditions. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2007;311:375-381.

- [Google Scholar]

- A systematic review of moving bed biofilm reactor, membrane bioreactor, and moving bed membrane bioreactor for wastewater treatment: Comparison of research trends, removal mechanisms, and performance. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2021;9:106112

- [Google Scholar]

- Silica Containing Composite Anion Exchange Membranes by Sol-Gel Synthesis: A Short Review. Polymers.. 2021;13:1874.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plasma induced grafting multiwall carbon nanotubes with chitosan for 4, 4′-dichlorobiphenyl removal from aqueous solution. Chem. Eng. J.. 2011;170:498-504.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modified Poly (vinylidene fluoride) by Diethylenetriamine as a Supported Anion Exchange Membrane for Lithium Salt Concentration by Hybrid Capacitive Deionization. Membranes.. 2022;12:103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical bond between chloride ions and surface carboxyl groups on activated carbon. Colloids Surf., A. 2017;530:53-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and characterization of PVDF-filled MWCNT hollow fiber mixed matrix membranes for gas absorption by Al2O3 nanofluid absorbent via gas–liquid membrane contactor. Chem. Eng. Res. Des.. 2020;156:478-494.

- [Google Scholar]

- In-situ combined dual-layer CNT/PVDF membrane for electrically-enhanced fouling resistance. J. Membr. Sci.. 2015;491:37-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorptive removal of phosphate by magnetic Fe3O4@ C@ ZrO2. Colloids Surf., A. 2015;469:100-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decoration of open pore network in Polyvinylidene fluoride/MWCNTs with chitosan for the removal of reactive orange 16 dye. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2017;174:474-483.

- [Google Scholar]

- Highly selective separations of multivalent and monovalent cations in electrodialysis through Nafion membranes coated with polyelectrolyte multilayers. Polymer. 2016;103:478-485.

- [Google Scholar]

- The simultaneous adsorption of nitrate and phosphate by an organic-modified aluminum-manganese bimetal oxide: Adsorption properties and mechanisms. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2019;478:539-551.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dispersion and alignment of carbon nanotubes in polymer matrix: a review. Mater. Sci. Eng.: R: Rep.. 2005;49:89-112.

- [Google Scholar]

- PVDF tactile sensors for detecting contact force and slip: A review. Ferroelectrics. 2016;504:31-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and characterizations of poly (vinylidene fluoride)/oxidized multi-wall carbon nanotube membranes with bi-continuous structure by thermally induced phase separation method. J. Membr. Sci.. 2014;467:142-152.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of molybdate and tetrathiomolybdate onto pyrite and goethite: effect of pH and competitive anions. Chemosphere. 2006;62:1726-1735.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and characterization of organophosphorylated TiO2 modified cation exchange membranes. Chin. J. Environ. Eng.. 2019;13:1282-1291.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and characterization of hydrophilic modification of polypropylene non-woven fabric by dip-coating PVA (polyvinyl alcohol) Sep. Purif. Technol.. 2008;61:276-286.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of molybdate on molybdate-imprinted chitosan/triethanolamine gel beads. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2014;114:514-520.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of Nano-SiO2/Al2O3/ZnO-Blended PVDF Cation-Exchange Membranes with Improved Membrane Permselectivity and Oxidation Stability. Materials.. 2018;11:2465.

- [Google Scholar]