Translate this page into:

The ethnobotanical, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of Psidium guajava L.

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Biological Sciences, PMB 2000, Abia State University, Uturu, Abia, Nigeria. amasryal@yahoo.com (Eziuche Amadike Ugbogu)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Psidium guajava L., commonly known as guava is an important tropical food plant with diverse medicinal values. In traditional medicine, it is used in the treatment of various diseases such as diarrhoea, diabetes, rheumatism, ulcers, malaria, cough, and bacterial infections. The aim of this review is to provide up-to-date information on the ethnomedicinal uses, bioactive compounds, and pharmacological activities of P. guajava with greater emphasis on its therapeutic potentials. The bioactive constituents extracted from P. guajava include phytochemicals (gallic acid, casuariin, catechin, chlorogenic acid, rutin, vanillic acid, quercetin, syringic acid, kaempferol, apigenin, cinnamic acid, luteolin, quercetin-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside, morin, ellagic acid, guaijaverin, pedunculoside, asiastic acid, ursolic acid, oleanolic acid, methyl gallate and epicatechin) and essential oils (limonene, trans-caryophyllene, α-humulene, γ-muurolene, selinene, caryophyllene oxide, bisabolol, isocaryophyllene, δ-cadinene, α-copaene, α-cedrene, β-eudesmol, α-pinene, β-pinene, β-myrcene, linalool, α-terpineol and eucalyptol). In vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that P. guajava possesses pharmacological activities such as antidiabetic, antidiarrhoeal, hepatoprotective, anticancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiestrogenic, and antibacterial activities which support its traditional uses. The exhibited pharmacological activities reported may be attributed to the numerous bioactive compounds present in different parts of P. guajava. Based on the beneficial effects of P. guajava as well as its bioactive constituents, it can be exploited in the development of pharmaceutical products and functional foods. However, there is a need for comprehensive studies in clinical trials to establish the safe doses and efficacy of P. guajava for the treatment of several diseases.

Keywords

Phytochemistry

Pharmacological

Psidium guajava

Traditional uses

Toxicity Profile

- P. guajava

-

Psidium guajava

- HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS

-

High-Performance liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization and quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- GC-FID

-

Gas Chromatography/Flame Ionization Detector

- GC–MS

-

Gas chromatography/Mass spectrometry

- HPLC

-

High-Performance liquid chromatography

- HPLC-DAD

-

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode Array Detection.

- UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS

-

Ultra-Performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrospray ionization tandem quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry

- HPLC

-

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

- HPLC-PDA

-

High-Performance liquid chromatography photodiode array detection

- MIC

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- IC50

-

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- CCl4

-

Carbon tetrachloride

- ALT

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- ALP

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- GGT

-

Gamma glutamyl transferase

- DPPH

-

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- NIST

-

National Institute of Science and Technology

- MCF-7 cell

-

Michigan Cancer Foundation-7

- HCT116

-

Human Colorectal carcinoma cell line

- HT29

-

Human Colon cancer cell line

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Globally, medicinal plants and its bioactive constituents are used for the treatment of various diseases. It has been reported that over 80% of the world's population uses medicinal plants or its bioactive compounds for the prevention, management, or treatment of several diseases (Joshi, 2013, Pant, 2014; Ugbogu et al., 2021). Recently, the uses of medicinal plants or their biologically active compounds have attracted the attention of many scientists/researchers because of their use in drug discovery or discovery of natural constituents for therapeutics (Dimmito et al., 2021, Sinan et al., 2021) and in ethnomedicinal uses for the treatment of life-threatening diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and hypertension (Sofowora et al., 2013, WHO, 2019). Psidium guajava is one of the plants used in traditional medicine for the treatment of various diseases.

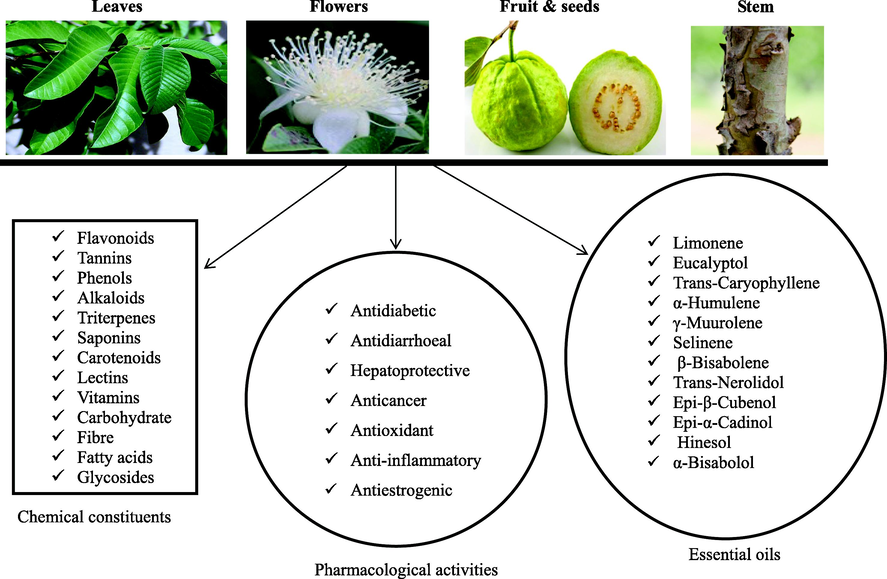

Psidium guajava L. is commonly known as guava. It is a tropical shrub tree and food plant that belongs to the Myrtaceae family (Ravi and Divyashree, 2014). It grows up to 10 m and is widely distributed in many countries. Psidium guajava L. is an economically important food plant with diverse medicinal properties. It has a short trunk, patchy, smooth, and peeling bark. The leaves are fleshy dark green with prominent veins (Morais-Braga et al., 2016a; Naseer et al., 2018). It has white flowers, and the fruit contains pulp and small hard seeds (Morais-Braga et al., 2016a) Fig. 1.

Various parts of P. guajava L., chemical constituents, and pharmacological activities.

In ethnomedicine, the various parts of P. guajava – the stem, bark (Beidokhti et al., 2020), fruits, leaves, and roots (Weli et al., 2019) are used in the treatment of diseases such as diarrhea, rheumatism, and diabetes (Gutiérrez et al., 2008, Morais-Braga et al., 2016b, Díaz-de-Cerio et al., 2017), digestive problems, laryngitis, ulcers, malaria, cough, and bacterial infections (Ravi and Divyashree, 2014, Díaz-de-Cerio et al., 2017), wound healing and pain relief (Metwally et al., 2010). Many natives consume decoction, infusion, and/or boiled preparations of P. guajava either orally or topically depending on the type of illnesses (Díaz-de-Cerio et al., 2017). For instance, P. guajava leaves can be applied on wounds whereas aqueous leaf extract can be orally consumed to lower the blood glucose level in diabetic patients (Gutierrez et al., 2008).

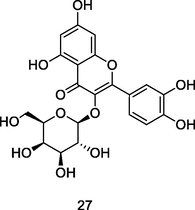

Psidium guajava consists of important chemical constituents such as flavonoids, tannins, phenols, alkaloids, triterpenes, saponins, carotenoids, lectins, vitamins, carbohydrate, fiber fatty acids, and glycosides (Gutiérrez et al., 2008, Weli et al., 2019). The leaves have a plethora of beneficial phenolic compounds such as guaijaverin, quercetin, kaempferol, apigenin, catechin, chlorogenic acid, hyperin, gallic acid, epicatechin, myricetin, caffeic acid, and epigallocatechin gallate (Kumar et al., 2021).

Studies have shown the abundance of the following essential oils; β-bisabolene, caryophyllene oxide, β-copanene, farnesene, longicyclene, humlene, selinene, cardinene, curcumene, β-caryophyllene, pinene, caryophyllene oxide, 1,8-cineeole and limonene in the leaves of P. guajava (Begum et al., 2004, Gutiérrez et al., 2008, De Souza et al., 2017, Weli et al., 2019) Fig. 1. The fruit is a rich source of dietary fibre (pectin), protein, vitamins (A and C), and minerals (iron, phosphorus, and calcium) (Naseer et al., 2018).

In 2009, P. guajava L. was listed in WHO monographs as one of the selected medicinal plants with supported clinical data; however, they reported that there is no information on its uses in pharmacopoeias and internal index components (WHO, 2009).

Pharmacological studies have demonstrated that P. guajava extracts possess antimutagenic, lipid-lowering, analgesic, anti-hyperglycemic effect, anti-inflammatory (Vasconcelos et al., 2017), adaptogenic, antidiabetics (Khan et al., 2013, Zhu et al., 2020), anticestodal, antidiarrheal (Koriem et al., 2019), anti-angiogenesis, hepato-protective (Vijayakumar et al., 2020), antioxidant (Laily et al., 2015, Flores et al., 2015), anticancer (Lin and Lin, 2020), antimicrobial (Silva et al., 2018), cardioprotective, spermatoprotective, anti-hypertensive, antiparasitic, and anticough activities (Gutiérrez et al., 2008, Ravi and Divyashree, 2014, Kumar et al., 2021) Fig. 1. The pharmacological activities exhibited by P. guajava may be attributed to the numerous bioactive compounds present in the plant.

The aim of this study is to comprehensively review past scientific literatures and provide up-to-update information on the ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemical constituents, in vitro and in vivo pharmacological activities of P. guajava.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Search strategy and study selection

In the search of materials for this study, the following search queries or keywords were used “Psidium”, “guajava”, “Psidium guajava”, “Psidium guajava pharmacological”, “Psidium guajava toxicity” and other related words in combination with words related to botanical description, taxonomical grouping, ethnopharmacological uses, phytochemical constituents, bioactive constituents, essential oils and pharmacological activities to find relevant peer-reviewed journals on four scientific databases, namely: PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), ScienceDirect (https://www.sciencedirect.com/), Wiley (https://www.wiley.com/en-us) and Springer (https://www.springer.com/gp). Only papers that were published in English language were used for this study. Chemical structures identified from the plant were searched in NIST Chemistry Webbook, ChemSpider, and PubChem databases. The identified structures were drawn using ChemDraw (version 12.0.2).

3 Botanical description

Psidium guajava is a member of the Myrtaceae family. It is a small tree approximately 10 m high with a characteristic thin, smooth, patchy, and peeling bark (Gutiérrez et al., 2008). Guava trees usually have wide-spreading branches (Flores et al., 2015). The leaves have an elliptical and oval shape with a dark green colour and obtuse-type apex (Kumar et al., 2021). The leaves lie opposite each other and possess a short-petiolate with prominent veins. The plant has numerous stamens and showy, whitish petals. Its flowers are between 4 and 6 white petals and white stamens with yellow anthers (Flores et al., 2015). Guava fruits appear very fleshy. Their shape ranges from a yellowish globose to ovoid berry. Their mesocarp is edible with several small hard white seeds (Gutiérrez et al., 2008). Different cultivars possess varying morphology of the skin of the fruit (Flores et al., 2015).

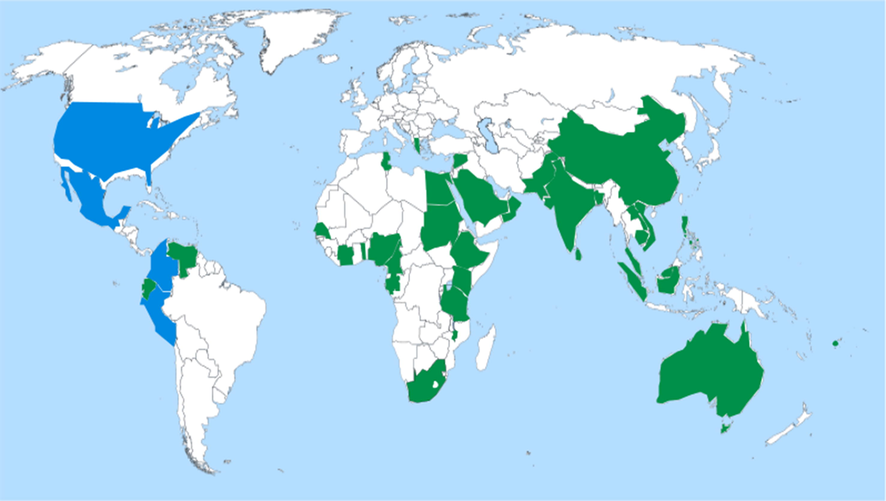

4 Geographical description and taxonomy

The Guava plant is a tropical plant indigenous to the Colombia, Mexico, Peru and United States of America (Gutiérrez et al., 2008; Hirudkar et al., 2020). It is commonly distributed in the regions like India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh (Kumar et al., 2021), Nigeria, South Africa, Malaysia, Bolivia, Cambodia, Cameroon, Philippines, Costa Rica, Senegal, Brazil, Ghana, Haiti, Cuba, Ethiopia, Kenya, Trinidad, Uganda, Namibia, Bangladesh, China and Sri Lanka (Gutierrez et al., 2008; Morais-Braga et al., 2016a; Weli et al., 2019). It is also found in Arabic countries such as Egypt, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Palestine, Sudan, Syria, and Tunisia (Abdelrahim et al., 2002; Qabaha, 2013, Weli et al., 2019) Fig. 2. Aboriginal peoples of the tropical and subtropical regions across the world cultivate the plant as food. It adapts to varying climatic conditions, although it thrives better in dry climates (Gutiérrez et al., 2008).

Map of worldwide distribution of Psidium guajava L., the blue colour shows the native regions like Colombia, Mexico, Peru and United States of America, whereas the green colour represents the introduced countries such as Australia, Bangladesh, Brunei, Cambodia, Cameroon, China, Costa Rica, Cote d'Ivoire, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Fiji, Gabon, Gambia, Greece, Guyana, Haiti, India, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Laos, Malawi, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nigeria, Pakistan, Panama, Philippines, Puerto Rico, Samoa, Senegal, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Thailand, Togo, Uganda, Venezuela, Vietnam, Egypt, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Palestine, Sudan, Syria and Tunisia.

5 Traditional/ethnomedicinal uses

Different countries have unique applications of the various parts (i.e., roots, leaves, bark, stem, and fruits) of the guava plants for medicinal purposes. These parts have been utilized for treating stomach-related diseases, diabetes, diarrhea, and other forms of disease conditions (Kumar et al., 2021). Asian countries have adopted the use of guava leaves to develop traditional medicines for the treatment of diabetes (Kumar et al., 2021). Indonesians use guava leaves, pulp, and seeds for treating respiratory and gastrointestinal disorders, as well as for increasing blood platelets in dengue fever patients (Laily et al., 2015). Also, guava leaves have been used therapeutically due to their antiamoebic, antispasmodic, antidiarrhoeal antiinflammatory, antihypertension, antiobesity, and antidiabetic properties (Chen and Yen, 2007, Hirudkar et al., 2020).

Digestive disorders can be treated using young leaves of the guava plant. Decoction of the young leaves and shoots of the plant possess febrifuge and spasmolytic properties. Natives employ the flowers to cool the body and treat bronchitis, as well as eye sores. The fruit can also serve as a tonic and laxative. Patients with bleeding gums can also receive treatment with the fruit extract (Begum et al., 2002). South Africans use leaves of P. guajava for treating diabetes and hypertension (Oh et al., 2005). In Madagascar, the bark of the plant is used in addition to the leaves for the treatment of diabetes (Beidokhti et al., 2020). Brazilians use P. guajava for treating dental and oral diseases. The leaves and bark peels are consumed, either swallowed or mashed whilst still hot, as a tea formulation to combat thrush.

Nigerians employ decoction of the plant for treating microbial infections. In Mexico, Brazil, Philippine, and Nigeria, P. guajava is used to prepare a poultice for skin and wound applications (Gutiérrez et al., 2008).

Digestive disorders and severe diarrhoea are treated by natives of Nahuatll and Maya origin, as well as Veracruz, using the leaf decoction. Indigenous people of Veracruz use the water leaf extract as a hot tea preparation to control blood glucose level in diabetes patients. Mexicans also handle gastrointestinal and respiratory disturbances using the plant extract– as well as for the treatment of inflammation (Gutiérrez et al., 2008).

Latin Americans and people of the Caribbean use guava for the treatment of diarrhoea and stomach pains (Gutiérrez et al., 2008). In Panama, the guava plant is used for treating dysentery. In Uruguay, formulations are prepared from the decoction of the leaves as a vaginal and uterine wash, especially for cases of leucorrhoea. In Costa Rica, preparations are made from the decoction of the flower buds as therapeutics for inflammation (Gutiérrez et al., 2008).

In Peru, gargles are formulated from the plant for treating gastroenteritis, dysentery, stomach pain, indigestion, inflammations of the mouth and throat. Leaf and bark decoctions of guava plants are also used by Tikuna Indians for treatment of gastrointestinal tract diseases (Gutiérrez et al., 2008). The Indians of the Amazons use decoctions of the plant leaves and bark for treating dysentery, sore throats, vomiting, stomach upsets, vertigo, mouth sores, as well as for regulating menstrual periods (Gutiérrez et al., 2008). West Indians use the leaves and shoots in febrifuge and antispasmodic baths. The Chinese use guava leaves as an antiseptic and anti-diarrhoea agent. Brazilians consume preparations of the plant fruit and leaves for treating anorexia, cholera, diarrhoea, digestive problems, dysentery, gastric insufficiency, inflamed mucous membranes, laryngitis, mouth (swelling), skin problems, sore throat, ulcers, and vaginal discharge (Holetz et al., 2002).

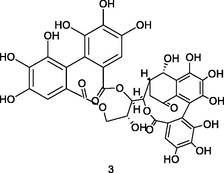

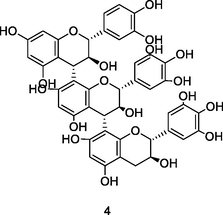

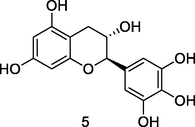

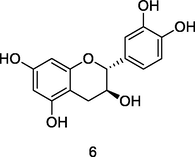

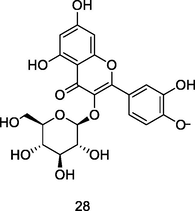

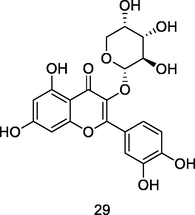

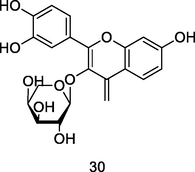

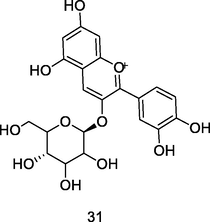

6 Phytochemistry

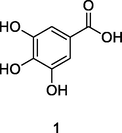

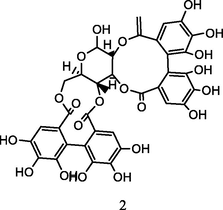

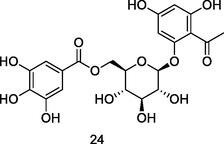

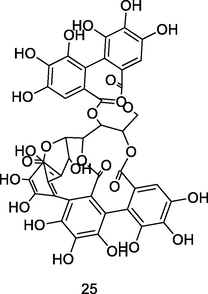

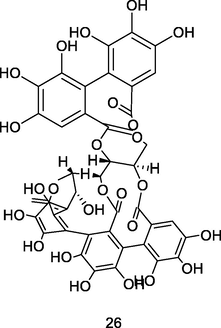

The study of Díaz-de-cerio et al. (2016) reported the presence of 72 phenolic constituents in guava leaves using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization and quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS). De Araújo et al., (2014) quantified the polyphenolic content (gallic acid and catechin) of P. guajava leaves using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Results of the study showed the presence of condensed tannins (catechins) and hydrolysable tannins (gallic acid) in P. guajava leaves (Table 1). Phytochemical studies of P. guajava leaves by Bhagavathy et al. (2018) using gas chromatography and mass spectrometry (GC–MS) confirmed the presence of carotenoids, flavonoids, alkaloids, polyphenols, saponins, tannins, glycosides and sterols. Babatola and Oboh (2021) characterized and quantified the phenolic constituent of guava leaves using HPLC-DAD, the major compounds identified include: chlorogenic acid, rutin, vanillic acid, quercetin, and p-hydroxyl benzoic acid, syringic acid, kaempferol, myricetin, isoquercetin, and apigenin. Bezerra et al. (2018, 2020) analyzed the chemical constituents of two fractions, viz. flavonoid and tannic fractions extracted from P. guajava leaves using UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS. In the flavonoids fraction, reynoutrina (quercetin-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside), guajaverina (quercetin-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside) and Morin), a condensed tannin (Catechin), and two hydrolysable tannins (ellagic acid and guavinoside B), an acetophenone (myrciaphenone B) were identified, whereas in the tannic fraction two flavonoids (quercetin and 2,6-dihydroxy-3-methyl-4-O-(6″-O-galloyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl)-benzophenone), a condensed tannin (catechin), a hydrolysable tannin (guayinoside C), and an elagotonine (vescalagin/Castalagin isomer, (1S*,5S*)-2,2-bis(biphenyl-4-yl)-5- indian-1-yltetrahydrofuran (IV-81)). Hseih et al. (2007) reported the presence of the following phenolic compounds; gallic acid, ferulic acid, and quercetin, in P. guajava leaves. Eidenberger et al. (2013) demonstrated that ethanolic extract of guava leaves contain seven main flavonol-glycosides through semipreparative HPLC analysis. They include; peltatoside quercetin-3-O-arabinoglucoside, hyperoside, quercetin-3-β-O-arabinoglucoside, isoquercetrin, quercetin-3-O-β-glucoside, guaijaverin, and quercetin-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside (Table 1). Flores et al. (2015) identified the following chemical compounds; delphinidin-3-O-glucoside and cyanidin-3-O-glucoside, myricetin-3-O-arabinoside, myricetin-3-O-xyloside, isorhamnetin-3-O-galactopyranoside, myricetin-3-O-glucoside, gallocatechin-(4α-8)-gallocatechol, gallocatechin-(4α-8)-catechin, abscisic acid, turpinionoside A, pinfaensin, pedunculoside, guavenoic acid, madecassiac acid and asiastic acid from guava cultivars (Table 1).

Name of compound

Chemical structure

Method of identification

Pharmacological activity

References

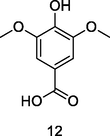

Gallic acid

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography with diode-array detection coupled to electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS) analysis of phenolic fraction of P. guajava leaves using an ultrasound bath and a mixture of ethanol:water 80/20 (v/v) (Díaz-de-cerio et al., 2016)

Anti-inflammatory, Antifungal activities

Alves et al. (2014); De Araújo et al. (2014)

Pedunculagin

HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS analysis of phenolic fraction of P. guajava leaves using an ultrasound bath and a mixture of ethanol:water 80/20 (v/v) (Díaz-de-cerio et al., 2016)

Anti-diabetic activity

Eidenberger et al. (2013)

Casuariin

HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS analysis of phenolic fraction of P. guajava leaves using an ultrasound bath and a mixture of ethanol:water 80/20 (v/v) (Díaz-de-cerio et al., 2016)

Anticoagulant, Anti-hypertensive activities

Dong et al. (1998); Xie et al. (2007)

Prodelphinidin dimer isomer

HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS analysis of phenolic fraction of P. guajava leaves using an ultrasound bath and a mixture of ethanol:water 80/20 (v/v) (Díaz-de-cerio et al., 2016)

Antioxidant activity

Ma et al. (2019)

Gallocatechin

HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS analysis of phenolic fraction of P. guajava leaves using an ultrasound bath and a mixture of ethanol:water 80/20 (v/v) (Díaz-de-cerio et al., 2016)

Anti-aggregation activity

Sohail et al. (2018)

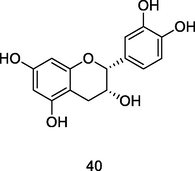

Catechin

HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS analysis of phenolic fraction of P. guajava leaves using an ultrasound bath and a mixture of ethanol:water 80/20 (v/v) (Díaz-de-cerio et al., 2016)

Anti-inflammatory, Antifungal activities

De Araújo et al. (2014); Bezerra et al. (2018)

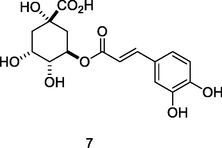

Chlorogenic acid

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Potential anti-inflammatory activity

Bhandarkar et al. (2019)

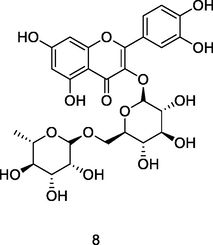

Rutin

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Antitumor, Antimicrobial, Antidiabetic activities

Budzynska et al. (2019); Ghorbani (2017)

Vanillic acid

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Antioxidative activity

Yao et al. (2020)

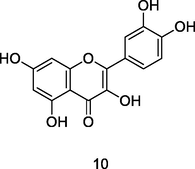

Quercetin

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Anti-hypertensive, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Antidiarrhea activities

Alves et al. (2014); Hirudkar et al. (2020); Marunaka et al. (2017)

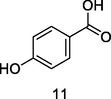

p-hydroxyl benzoic acid

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Anti-inflammatory activity

Banti et al. (2021)

Syringic acid

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Anti-inflammatory, Anti-microbial activities

Liu et al. (2020)

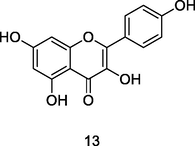

Kaempferol

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Anti-inflammatory, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant activities

Alam et al. (2020); Bezerra et al. (2018)

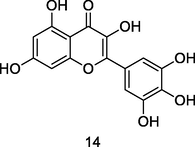

Myricetin

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Cardioprotective activities

Wang et al. (2019)

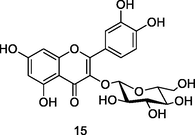

Isoquercetin

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Neuroprotective activities

Dai et al. (2018)

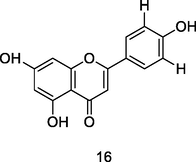

Apigenin

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Anticancer activities

Imran et al. (2020)

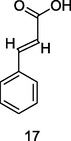

Cinnamic acid

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Anti-inflammatory activities

Karatas et al. (2020)

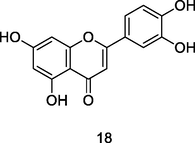

Luteolin

HPLC-DAD analysis using phenolic fraction of guava leaves (Babatola and Oboh, 2021)

Anti-inflammatory, Antifungal activities

Zhang et al. (2018)

Reynoutrina (quercetin-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside)

‘

Ultrafine liquid chromatography coupled to quadruple time-of-flight (UPLC-QTOF) analysis flavonoid fraction of guava leaves (Bezerra et al., 2018)

Anti-inflammatory activities

Yang et al. (2021)

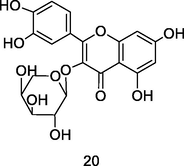

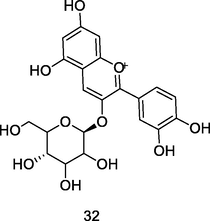

Guajaverina (quercetin-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside)

UPLC-QTOF analysis flavonoid fraction of guava leaves (Bezerra et al., 2018)

Antifungal, Antibacterial activities

Ukwueze et al. (2015)

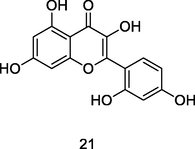

Morin

UPLC-QTOF analysis flavonoid fraction of guava leaves (Bezerra et al., 2018)

Anti-mastitis, Antimicrobial, Antioxidant activities

Jiang et al. (2020)

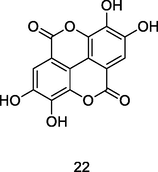

Ellagic acid

UPLC-QTOF analysis flavonoid fraction of guava leaves (Bezerra et al., 2018)

Anti-inflammatory activities

Bensaad et al. (2017)

Guavinoside B

UPLC-QTOF analysis flavonoid fraction of guava leaves (Bezerra et al., 2018)

Hepatoprotective activity

Li et al. (2020)

Myrciaphenone B

UPLC-QTOF analysis flavonoid fraction of guava leaves (Bezerra et al., 2018)

Anti-fungal activities

De Leo et al. (2004)

Vescalagin

UPLC-QTOF analysis flavonoid fraction of guava leaves (Bezerra et al., 2018)

Anticancer activities

Kamada et al. (2018)

Castalagin Isomer

UPLC-QTOF analysis flavonoid fraction of guava leaves (Bezerra et al., 2018)

Anticancer activity

Kamada et al. (2018)

Hyperoside

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled to Ultraviolet light and Mass spectrometry (HPLC/UV/MS) analysis of 80% ethanolic extract of guava leaves (Eidenberger et al., 2013)

Anticancer activity

Qiu et al. (2019)

Quercetin-3-O-β-glucoside

HPLC/UV/MS analysis of 80% ethanolic extract of guava leaves (Eidenberger et al., 2013)

Neuroprotective activities

Magalingam et al. (2016)

Guaijaverin

HPLC/UV/MS analysis of 80% ethanolic extract of guava leaves (Eidenberger et al., 2013)

Antimicrobial activities

Prabu et al. (2006)

Quercetin-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

HPLC/UV/MS analysis of 80% ethanolic extract of guava leaves (Eidenberger et al., 2013)

Anti-inflammatory activity

Kim et al. (2018)

Delphinidin-3-O-glucoside

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography coupled to Photodiode-Array Detection (HPLC-PDA) analysis of guava pulp extracted using CH3OH/H20/formic acid (Flores et al., 2015)

Anticancer activity

Mazewski et al. (2019)

Cyanidin-3-O-glucoside

HPLC-PDA analysis of guava pulp extracted using CH3OH/H20/formic acid (Flores et al., 2015)

Anti-obesity activity

Molonia et al. (2020)

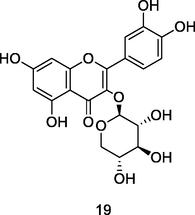

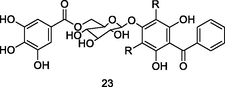

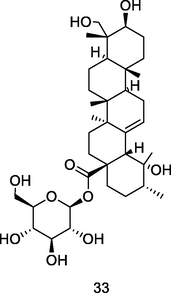

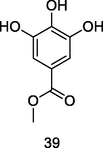

Pedunculoside

HPLC-PDA analysis of guava pulp extracted using CH3OH/H20/formic acid (Flores et al., 2015)

Antihyperlipidemic activities

Liu et al. (2018)

Madecassiac acid

HPLC-PDA analysis of guava pulp extracted using CH3OH/H20/formic acid (Flores et al., 2015)

Anticancer activities

Valdeira et al. (2019)

Asiastic acid

HPLC-PDA analysis of guava pulp extracted using CH3OH/H20/formic acid (Flores et al., 2015)

Anti-inflammatory activities

Hao et al. (2017)

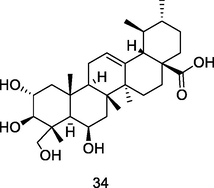

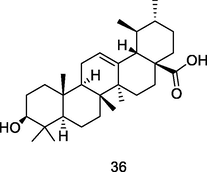

Ursolic acid

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis of fresh ethanol leaf extract of P. guajava (Begum et al., 2004)

Anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antidiabetic, antioxidant, and antibacterial activities

Hsieh et al. (2007); Mlala et al. (2019)

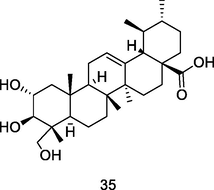

Oleanolic acid

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis of fresh ethanol leaf extract of P. guajava (Begum et al., 2004)

Antitumor, Anti-diabetic, Antimicrobial, Hepatoprotective actiivities

Hsieh et al. (2007); Ayeleso et al. (2017)

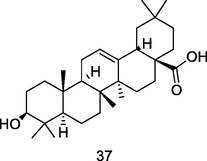

Beta-sitosterol glucoside

Thin layer chromatography (TLC) analysis of ethanol leaf extract of P. guajava (Begum et al., 2002)

Anticancer, apoptogenic activity

Vo et al. (2020); Dolai et al. (2016)

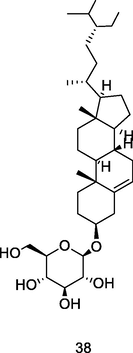

Methyl gallate

HPLC-UV analysis of leaf extract of P. guajava (Farag et al., 2020)

Antileishmanial,antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial and anti-tumor activities

Dias et al. (2020); Anzoise et al. (2018)

Epicatechin

HPLC–DAD of hydroethanolic or aqueous extract of P. guajava leaves (Morais-Braga et al., 2017)

Anticoagulant, Pro-fibrinolytic, enzyme-inhibitory activities

Sinegre et al. (2019); Wu et al. (2019)

Procyanidin

HPLC-DAD-ESI-QTOF-MS analysis of phenolic fraction of P. guajava leaves using an ultrasound bath and a mixture of ethanol:water 80/20 (v/v) (Díaz-de-cerio et al., 2016)

Antioxidant activity

Hsieh et al. (2007); Ma et al. (2019)

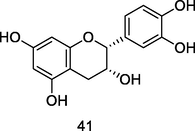

Protocatechuic acid

LC-HRMS-MS with the OLE Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) analysis of P. guajava leaf decoction (Lorena et al., 2022)

Antioxidative, Neuroprotective, Anti-atherosclerotic activities

Krzysztoforska et al. (2019); Zheng et al. (2020)

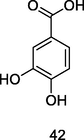

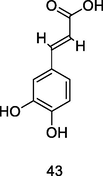

Caffeic acid

HPLC–DAD of hydroethanolic or aqueous extract of P. guajava leaves (Morais-Braga et al., 2017)

Neuroprotective, enzyme-inhibitory activities

Habtemariam (2017); Zhang et al. (2019); Maruyama et al. (2018)

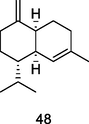

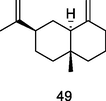

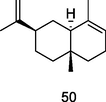

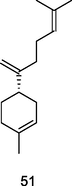

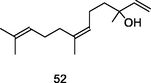

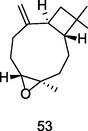

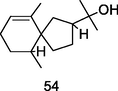

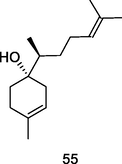

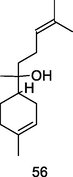

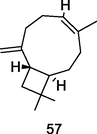

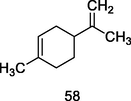

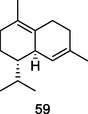

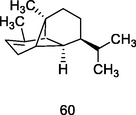

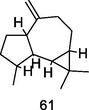

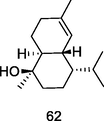

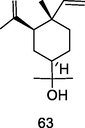

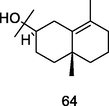

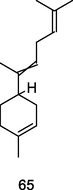

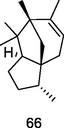

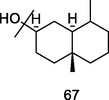

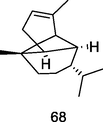

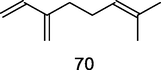

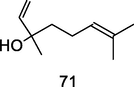

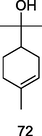

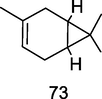

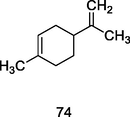

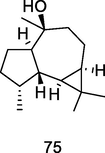

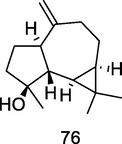

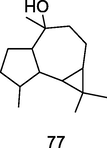

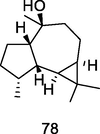

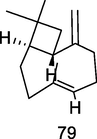

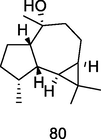

The chemical constituents present in the essential oil of P. guajava include; α-pinene, β-pinene, β-myrcene, linalool, α-terpineol, δ-3-carene, limonene, eucalyptol, trans-caryophyllene, α-humulene, γ-muurolene, β-selinene, α-selinene, α-bisabolene β-bisabolene, trans-nerolidol, epi-β-cubenol, epi-α-cadinol, hinesol, 14-hydroxy-9-epi-(e)-caryophyllene, β-bisabolol, α-bisabolol, iso-caryophyllene, veridiflorene, β-caryophyllene, farnesene, dl-limonene, δ-cadinene, α-copaene, β-copaene, aromadendene, elemol, scadinol, 1,8-cineole, trans-calamenene, junipene, α-gurjunene, cis-ocimene, β-ocimene, aromadendene, α-muurolene, δ-cadinol, β-eudesmol, γ-eudesmol, α-cedrene, Ɗ-Limoene, globulol, viridiflorol, cubenol, tau-muurolol, cis-lanceol, α-acorenol, epiglobulol, spathulenol, ledol and caryophyllene oxide (De Souza et al., 2018; Weli et al., 2019; Hassan et al., 2020) (Table 2).

Name of compound

Chemical structure

Method of identification

Pharamacological activity

References

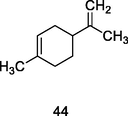

Limonene

Gas chromatography coupled to Flame ionized detector or Gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC-FID/GC–MS) of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Antitumor, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anticancer activities

De Souza et al. (2017); Mukhtar et al. (2018)

Eucalyptol

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Retinoprotective activity

Kim et al. (2020); Hassan et al. (2020)

Trans-Caryophyllene

GC-FID/GC–MS) of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Antileishmanial, antischistosomal, antifungal activities

De Souza et al. (2017)

α-Humulene

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Antiinflammatory

De Souza et al. (2017); Hassan et al. (2020)

γ-Muurolene

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Antifungal, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities

Doan et al. (2021)

β-Selinene

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Trypanocidal activity

De Souza et al. (2017); Fernandes et al. (2021); Hassan et al. (2020)

α-Selinene

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Antifungal activity

De Souza et al. (2017); Oladeji et al. (2020)

β-Bisabolene

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Cytotoxic activity

Yeo et al. (2016); Hassan et al. (2020)

Trans-Nerolidol

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Antifungal activity

De Souza et al. (2017); Hassan et al. (2020)

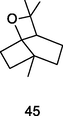

Caryophyllene oxide

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Antifungal and antibacterial activity

Policegoudra et al. (2012); Hassan et al. (2020)

Hinesol

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Antitumor activity

De Souza et al. (2017); Guo et al. (2019)

β-Bisabolol

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Antimicrobial, antitumor activities

De Souza et al. (2017)

α-Bisabolol

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Antimicrobial, antitumor activities

De Souza et al. (2017)

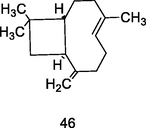

Isocaryophyllene

Gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (Weli et al., 2019)

Anticancer

Legault and Pichette (2010)

dl-limonene

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (Weli et al., 2019)

Antiaflatoxigenic activity

Singh et al. (2010)

δ-cadinene

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (Weli et al., 2019)

Larvicidal, Anticancer activities

Govindarajan et al. (2016); Hui et al. (2015);

α-copaene

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (Weli et al., 2019)

Attractant activity

Kendra et al. (2017); Hassan et al. (2020)

Aromadendrene

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (Weli et al., 2019)

Insecticidal activity

Hassan et al. (2020); Giuliani et al. (2020)

δ-cadinol

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate (Weli et al., 2019)

Anti-mildew

Su et al. (2015); Hassan et al. (2020)

Elemol

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Immunosuppressive activity

Yang et al. (2015)

γ-Eudesmol

GC-FID/GC–MS of P. guajava hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Cytotoxic activity

Britto et al. (2012); Hassan et al. (2020)

α-Bisabolene

GC-FID/GC–MS) of P. guajava hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Anti-cancer

Yeo et al. (2016)

α-Cedrene

GC-FID/GC–MS) of P. guajava hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Potential anti-obesity activity

Kim et al. (2015)

β-Eudesmol

GC-FID/GC–MS) of P. guajava hydrolate (De Souza et al., 2018)

Anti-allergic, anticancer, anti-angiogenic activities

Han et al. (2017); Narahara et al. (2020); Acharya et al. (2021)

Copaene

GC–MS analysis of methanolic extract of P. guajava leaves (Bhagavathy et al., 2018)

Cytotoxic activity

Türkez et al. (2014)

α-Pinene

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Antioxodant, anti-inflamatory, anticancer, pro-osteogenic activities

Zhao et al. (2018); Min et al. (2020);

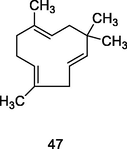

β-Myrcene

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Anxiolytic, antioxidant, anti-ageing, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, genotoxic activities

Surendran et al. (2021); Orlando et al. (2019)

Linalool

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, anti-hyperlipidemic, antinoceptive, analgesic, anxiolytic activities

Sabogal-Guáqueta et al. (2019)

α-Terpineol

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Cytotoxic, antitumor, antidiarrheal,

Negreiros et al. (2021); Dos Santos Negreiros et al. (2019)

δ-3 carene

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Sleep-enhancing, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anxiolytic activities

Woo et al. (2019); Shu et al. (2019)

Ɗ-Limoene

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Antioxidant, antidiabetic, anticancer, anti-inflammatory

Anandakumar et al. (2021); Seo et al. (2020)

Epiglobulol

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Antimicrobial activity

Kim and Shin (2004)

Spathulenol

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative activities

do Nascimento et al. (2018); Ziaei et al. (2011); Lou et al. (2019)

Globulol

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Potential antimicrobial activity

Tan et al. (2008)

Viridiflorol

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial activities

Trevizan et al. (2016)

β-Caryophyllene

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Neuroprotective, anticancer, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, wound-healing, antimicrobial activities

Scandiffio et al. (2020); Koyama et al. (2019); Yoo and Jwa (2018)

Ledol

GC–MS analysis of P. guajava leaves hydrolate extracted with hexane (Hassan et al., 2020)

Antitumor activity

Cianfaglione et al. (2017)

7 Pharmacological activities of P. guajava

7.1 Antidiabetic activity

Several researchers have investigated the antidiabetic potential of P. guajava (Huang et al., 2011, Khan et al., 2013, Luo et al., 2019, Zhu et al., 2020; Uuh-Narvaez et al., 2021). Rai et al. (2009, 2010) reported that raw fruit peels and aqueous unripe fruit peels extracts of P. guajava exhibited hypoglycaemic effect in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Supplementation of 125 and 250 mg/kg of guava fruit for 4 weeks in streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetic rats reduced blood glucose levels (Huang et al., 2011). Ojewole (2005) observed that the aqueous P. guajava leaf extracts have a hypoglycaemic effect in diabetic rats (Table 3). Rajpat and Kumar (2021) revealed that 200 mg/kg ethanolic extract of P. guajava leaves extract reduced blood glucose levels in diabetic mice. Shen et al. (2008) posited that guava leaf aqueous extract reduces blood glucose level and accelerates plasma insulin level. Oral administration of 300 mg/kg body weight/day of P. guajava leaf extract for 30 days to STZ-induced diabetes rats decreased blood glucose levels (Subramanian et al., 2009).

Doses

Experimental models

Observation

Effects

References

Psidium guajava dissolved in 125 μL tryptic soy broth

Streptococcus salivarius, Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus sanguinis and Streptococcus sobrinus

Inhibitory activity (500–100 μg/mL) against all Streptococcus species used.

Antibacterial activity

Silva et al. (2018)

1000, 500, 250 and 125 μg/ml of essential oils extracted from Psidium guajava

Enterococcus faecalis, S. aureus, Streptococcus aureus, E. coli, Haemophilus influenzae and P. aeruginosa

Inhibitory activity against Enterococcus faecalis and Streptococcus aureus.

Antibacterial activity

Weli et al. (2019)

25, 50, 100 and 150 μgml−1

E. coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Salmonella typhimurium

40 μgml−1 induced a 90% inhibition of Klebsiella spp. and 30% inhibition of Proteus spp.

Antibacterial activity

Pelegrini et al. (2008)

1024 μg/mL of Psidium guajava extracts

E. coli, P. aeruginosa and S. aureus

Extract produced an MIC value of 256 μg/mL against S. aureus

Antibacterial activity

Morais-Braga et al. (2016a,b)

Chemical constituents isolated from Psidium guajava

S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and Mycobacterium Smegmatis

Psidinone extracted showed inhibitory activity with MIC values of 16, 8, and 0.5 μM respectively.

Antibacterial activity

Huang et al. (2021)

Dilutions of methanol, chloroform and hexane extracts of Psidium guajava

Agrobacterium tumefaciens

IC50 values; 65.02 μg/mL, 160.7 μg/mL and 337.4 μg/mL for hexane, chloroform and methanol extracts

Antitumor activity

Ashraf et al. (2016)

0.5 mL dilutions of methanol, chloroform and hexane extracts ofPsidium guajava

Brine shrimp; Artemia salina nauplii

IC50 values of 32.18 μg/mL, 41.05 μg/mL 63.81 μg/mL for hexane, chloroform and methanol extracts

Anticancer activity

Ashraf et al. (2016)

16,384 μg/mL of Psidium guajava

Fungal strains of C. albicans and C. tropicals

IC50 value of 3235.94 μg/mL

Antifungal activity

Morais-Braga et al. (2015)

1000 to 5 μg mL−1 of concentrated Psidium guajava

C. albicans, C. krusei, C. glabrata

Antifungal activity against C. glabrata with MIC value of 80 μg/mL

Antifungal activity

Fernandes et al. (2014)

250, 500 and 1000 μg/mL of Psidium guajava

3 × 104 per millilitre of Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigote

Hydroethanolic extract of Psidium guajava led to death of mammalian cells at 76.30%

Antiparasitic activity

Machado et al. (2018)

75 mg/kg of ethanolic extract of Psidium guajava

2x105 Giardia lamblia cysts /0.1 mL intraesophageally in rats

Extract produced a percentage reduction in trophozoite count

Antiparasitic activity

Khedr et al. (2021)

8, 40 and 200 μg/ml of guava seed polysaccharides

2 × 105 cells/ml of MCF-7 cells

Extracts at the concentration (40 and 200 μg/mL) inhibited MCF-7 cell viability.

Anticancer activity

Lin and Lin (2020)

800 to 6.25 μg/mL of lycopene extracted from Psidium guajava.

2 × 105 cells/ml of MCF-7 cells

Extract at the concentration (5.964 μg/mL) inhibited MCF-7 cell viability.

Anticancer activity

dos Santos et al. (2017)

20 to 100 μM of compounds separated from Psidium guajava

HCT116 and HT29 cells

After 72 h of administration compound extracted inhibited growth of cells at 81.4% with IC50 value of 60 μM

Anticancer activity

Zhu et al. (2020)

10 to 100 mg/mL of methanol, hexane and chloroform of Psidium guajava extracts

KBM5, SCC4 and U266

Hexane extract showed maximum inhibitory activity against cancer cells with IC50 value less than 30 mg/mL

Anticancer activity

Ashraf et al. (2016)

50 mg/kg of water and fractionated extracts of Psidium guajava

0.3 mol L−1 of Citric acid aerosol in cognizant guinea pigs

After 30mins of administration antitussive activity becomes prominent with suppression of cough

Antitussive activity

Khawas et al. (2018)

1,2,5 g/kg of Psidium guajava leaf extract

30 μmol of capsaicin induced in rats and guinea pigs

Doses suppressed cough by 16%, 35% and 54% respectively after 10 mins

Anticough activity

Jaiarj et al. (1999)

12.5, 25 and 50 mg/kg of extracts fractionated from P. guajava

0.3 mg/kg of 17 β-estradiol in female Wistar rats

Administration of extracts inhibited the proliferative effect of 17 β-estradiol on the uterus.

Anti-estrogenic activity

Bazioli et al. (2020)

125 and 250 mg/kg of P. guajava

55 mg/kg of STZ in male Sprague–Dawley rats

Reduction of blood glucose levels and amelioration of STZ-induced weight loss

Anti-diabetic activity

Huang et al. (2011)

300 mg/kg of P. guajava extracts

50 mg/kg of STZ in rats

Increase in levels of glycosylated hemoglobin, insulin, glucose and restoration of normal hexokinase activity

Anti-diabetic activity

Khan et al. (2013)

Doses of flavonoids extracted from guava leaves

40 mg/kg of STZ in rats

Regulation of fasting blood glucose levels

Anti-diabetic activity

Zhu et al. (2020)

25, 50 mg/kg of P. guajava extract

55 mg/kg of STZ in female Sprague–Dawley rats

Reduction of blood glucose levels

Anti-diabetic activity

Soman et al. (2013)

200 mg/kg of P. guajava extract

70 mg/kg of STZ in rats

Reduction of blood glucose levels

Anti-diabetic activity

Rajpat and Kumar (2021)

1.00, 0.50 and 0.75 g/kg of ethanolic P. guajava extract

100 mg/kg of alloxan tetrahydrate in Wistar rats

Reduction of blood glucose levels

Anti-diabetic activity

Mazumdar et al. (2015)

200 mg/kg of guava leaf extracts

40 mg/kg of STZ in rats

Increase in levels of antioxidants and insulin signalling genes

Anti-diabetic activity

Jayachandran et al. (2020)

300 mg/kg of ethanolic extract of P. guajava

1.5 mL/kg of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)

Decrease in serum levels of ALT, AST, and ALP

Hepatoprotective activity

Vijayakumar et al. (2020)

250 and 500 mg/kg of Psidium guajava and P. cattleianum extracts

Single dose of paracetamol (600 mg/kg)

Decrease in serum levels of AST, ALT, and ALP

Hepatoprotective activity

Saber et al. (2018)

0.2 mL of guava leaf solution

1 mL of 0.2mM 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) ethanolic solution

Production of an antioxidant content value of 201.71 mg BHA eqv · g−1

Antioxidant activity

Laily et al. (2015)

50 μL aliquot of P. guajava sample

150 μL of 400μM DPPH

High antioxidant activity in DPPH and ABTS assays

Antioxidant activity

Flores et al. (2015)

1 mL of chloroform, methanolic and hexane extracts of P. guajava

4 mL of 0.1 mM DPPH

High antioxidative activity of methanolic extract

Antioxidant activity

Ashraf et al. (2016)

200 μL of essential oils derived from P. guajava

50 μL of 1 mM DPPH

Reduction of DPPH radical.

Antioxidant activity

Lee et al. (2012)

100 μL of solution silver nanoparticles from P. guajava

200 μL of 100 μM DPPH methanol solution

Antioxidant activity increased in dose dependent manner

Antioxidant activity

Wang et al. (2018)

100 μL guava extract solution

100 μL of 0.5 mmo1/L DPPH solution

Presence of poly phenols induced good antioxidant activity

Antioxidant activity

Tan et al. (2020)

90 μL of 1000–50 μg/mL P. guajavaextracts and fractions

2.7 mL of Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) reagent

Flavonoid fraction showed highest antioxidant with lowest EC50 value

Antioxidant activity

Sobral-Souza et al. (2018)

50 μL of P. guajava leaf fractions

1 mL of 0.1 mM DPPH

Methanolic extract showed the most antioxidant activity

Antioxidant activity

Zahin et al. (2017)

Water extract (WE-PGL) and sulfate polysaccharide (PS-PGL) fraction of P. guajava

DPPH radicals

PS-PGL produced IC50 value of 0.02 mg/mL whilst WE-PGL produced 0.11 mg/mL against hydroxyl radical

Antioxidant activity

Kim et al. (2016)

25, 50 and 100 mg/kg of lycopene extracted from guava leaves

50 μL of a Carrageenan suspension in Swiss mice

Extract at high doses inhibited formation of edema

Anti-inflammatory activity

Vasconcelos et al. (2017)

50–200 mg/kg of P. guajava extract

0.1 mL of a carrageenan suspension in rats

Inhibition of edema

Anti-inflammatory activity

Olajide et al. (1999)

50 and 100 mg/kg of P. guajava extracts

Lactose containing diet in mice

Reversal of abnormalities in serum electrolytes and urine levels

Antidiarrheal activity

Koriem et al. (2019)

100, 200, 400 mg/kg of P. guajava extracts

1 mL of 3.29 × 109 CFU/ml of Escherichia coli in rats

Reduction in number and weight of stools

Antidiarrheal activity

Hirudkar et al. (2020)

250 mg/kg, 500 mg/kg and 750 mg/kg of P. guajava extracts

2 mL of castor oil in rats

Reduced number of wetted feaces and drop in frequency of stooling

Antidiarrheal activity

Mazumdar et al. (2015)

Uuh-Narvaez et al. (2021) posited that 10 mg/kg of edible parts P. guajava administered to diabetic rodents demonstrated high antihyperglycemic activity. Mazumdar et al. (2015) showed that ethanolic extracts of P. guajava administered to alloxan-induced diabetic rats reduced the blood glucose concentration. Jayachandran et al. (2020) investigated the activity of 200 mg/kg b.w of P. guajava extract against the insulin signalling proteins of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and reported antidiabetic activity of P. guajava because of its regulation of insulin signalling pathway genes.

Beidokhti et al. (2020) stated that leaf and bark extracts of P. guajava effectively improved glucose uptake in muscle cells and inhibited α-amylase, respectively. Yang et al. (2020) reported that guava leaf extract reduced fasting plasma glucose, fasting insulin, and insulin resistance in KK-Ay diabetic mice. P guajava leaves extract decreased fasting blood glucose, lipid level, and altered glucose metabolism in STZ-induced diabetic rats (Khan et al., 2013, Xu et al., 2020) (Table 3).

Supplementation of flavonoids extracted from P. guajava markedly reduced fasting plasma glucose, glucose tolerance, and insulin resistance in diabetic mice (Zhu et al., 2020). Luo et al. (2019) opined that polysaccharide from guava leave exhibited anti-diabetic effects in STZ-induced diabetic mice. Shabbir et al. (2020) reported blood glucose level reduction potential of polyphenol extracted from guava pulp, seeds, and leaves in diabetic mice. These antidiabetic activities could be due to the ability of P. guajava to increase levels of glycogen synthase and decrease in the activity of the enzyme; glycogen phosphorylase (Tella et al., 2019).

7.2 Hepatoprotective activity

Vijayakumar et al. (2020) assessed the hepatoprotective effect of P. guajava against carbon tetrachloride-induced damage in rats. Hepatotoxicity was induced in the liver by the administration of 1.5 mL/kg of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4) in rats. Daily oral administration of the extract for 21 days decreased the CCl4 induced increase in serum levels of liver biomarkers (ALT, AST, ALP, and GGT). A similar result was observed by Roy and Das (2010). Saber et al. (2018) studied the effects of P. guajava in combination with P. cattleianum against paracetamol-induced toxicity in rats. The pre-administration of the extract at 250 and 500 mg/kg reduced elevated levels of liver enzymes ameliorating hepatotoxicity. The hepatoprotective effects of aqueous unripe P. guajava fruit peel extract in STZ-induced diabetic rats were evaluated by Rai et al. (2010). They observed a significant decrease in ALP, AST, ALT, indicating hepatoprotective effects of unripe P. guajava fruit peel. P. guajava extract treatment at the doses of 100, 200, and 300 mg/kg, bw and 20 mg/kg of quercetin fraction decreased lipid metabolism in CCl4-induced hepatotoxic rats (Vijayakumar et al., 2018). Li et al. (2021) reported that triterpenoid-enriched guava leaf extract reduced serum ALT and AST levels, and hepatic ROS and MDA in acetaminophen-exposed C57BL/6 male mice. Li et al. (2020) posited that 100 mg/kg/day of Guavinoside B extracted from guava fruit markedly improved serum and hepatic biochemical parameters in acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice (Table 3).

7.3 Antioxidant activity

Scientific studies have reported the antioxidant activities of P. guajava (Laily et al., 2015, Flores et al., 2015, Li et al., 2015; Ashraf et al., 2016). Tan et al., (2020) investigated the antioxidative properties of extracts derived from red and white P. guajava fruits through different drying processes. Findings from this study revealed maximum antioxidant activity in red P. guajava powders extracted by vacuum drying compared to other drying methods. Sobral-Souza et al. (2018) reported the antioxidative ability of flavonoids extracted from extracts of P. guajava.

Luo et al. (2019) opined that polysaccharide from guava leaves exhibited antioxidant activities by increasing the total antioxidant activity and superoxide dismutase (SOD) enzyme and lower MDA activities in STZ-induced diabetic mice. Methanolic leaf extract of P. guajava fraction showed antioxidant activity (Khedr et al., 2021).

Zahin et al. (2017) revealed that P. guajava fractionated in methanol possesses maximum antioxidant activity compared to other solvents; petrol, benzene, acetone, and ethyl acetate. Kim et al. (2016) evaluated the antioxidative properties of polysaccharides extracted from P. guajava using hydroxyl radical and 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH). Results from the study of Kim et al. (2016) showed that the extract possesses strong antioxidant activity against hydroxyl radicals. Wang et al. (2018) observed strong antioxidant ability of silver nanoparticles extracted from P. guajava. Lee et al. (2012) reported moderate antioxidant activities of essential oil (EO) extracted from guava leaves. Feng et al. (2015) examined the antioxidative effects of compounds isolated from P. guajava. Results from this study revealed guavinoside C, guavinoside F, quercetin, quercetin-3-O-a-L-arabinofuranoside and quercetin-3-O-a-L-arabinopyranoside showed strong antioxidant activity using DPPH assay. The antioxidant activity of P. guajava extracts might be due to the presence of high phenolic compounds (Hartati et al., 2020) (Table 3).

7.4 Anti-inflammatory activity

Vasconcelos et al. (2017) investigated the anti-inflammatory activity of lycopene extracted from guava and lycopene purified from guava against carrageenan-induced paw edema. Edema in experimental rats was induced using a single injection of 50 μL of a carrageenan suspension. 25, 50, and 100 mg/kg of lycopene extracted from guava were administered alongside indomethacin. Findings from this study revealed the inhibition of edema by extract at a high dose (50 mg/kg). Olajide et al. (1999) evaluated the anti-inflammatory activity of rats against Carrageenan-induced rat paw edema. Rats were pre-administered P. guajava extracts at doses between 50 and 200 mg/kg. Results revealed the significant inhibitory activity of P. guajava on edema formation processes (Table 3).

7.5 Antidiarrhoeal activity

Koriem et al. (2019) assessed the antidiarrhoeal activity of P. guajava extracts against lactose-containing diet-induced osmotic diarrhoea in rats (Table 3). Rats in treatment groups were administered 50 and 100 mg/kg of P. guajava extracts daily for 1 month. Desmopressin was used as the standard drug. Administration of extract revealed a return to normal volume of urine excretion and serum electrolytes. Lipid peroxidation was reduced, emphasizing the extract’s antidiarrheal activity. Hirudkar et al. (2020) evaluated the antidiarrhoeal effect of P. guajava extracts against enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in rats. Diarrhoea was induced in rats by administration of 1 mL of 3.29 × 109 CFU/ml of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Findings from this study revealed the administration of the extract at 100, 200, 400 mg/kg induced a reduction in the total number of diarrhoeal stools, a decline in the weight of stools, and reduced mean defecation rate of stools in treatment groups. A reversal in declined values of WBC, Hb, and platelets also indicated the antidiarrhoeal ability of the extract. Mazumdar et al. (2015) examined the effect of ethanolic extract of P. guajava on castor oil-induced diarrhoea in rats. Doses of 250 mg/kg, 500 mg/kg, and 750 mg/kg of the plant’s extract were administered and 2 mg/kg of loperamide was used as a standard drug. Mazumdar et al. (2015) reported that the administration of extract induced a reduction in defecation frequency and the number of wetted faeces. Lutterodt (1992) assessed the propulsion rates in the small intestine of microlax induced diarrhoea in rats. Leaf extract of P. guajava at doses ranging from 50 to 400 mg/kg p.o. produced anti-diarrhoeal effect against castor oil-induced diarrhoea in rats and mice (Ojewole et al., 2008). P. guajava exhibited anti-inflammatory activity (Jang et al., 2014). El-Ahmady et al. (2013) reported that P. guajava leaf oil has anti-inflammatory activity. Results showed the extract exhibits a similar inhibition rate compared to the standard drug, morphine sulphate injection used (Table 3).

7.6 Antibacterial activity

Abdelrahim et al. (2002) stated that the aqueous bark and methanolic extracts of P. guajava possess anti-bacterial activity. Dutta et al. (2020) reported that benzyl isocyanate obtained from methanol extract of P. guajava leaves inhibited S. aureus. P. guajava leaves extract reduced virulence of P. aeruginosa, C. violaceum, S. aureus and S. marcescens (Patel et al. 2019) (Table 3). Essential oil of the senescent leaves of P. guajava inhibited human pathogenic bacteria and plant pathogenic fungi, namely C. lunata and F. chlamydosporum (Chaturvedi et al., 2021).

Silva et al. (2018) showed that extracts of P. guajava exhibited antibacterial activity against bacterial species; Streptococcus salivarius, Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus mitis, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Streptococcus sobrinus. Weli et al. (2019) studied the antibacterial activity of essential oils derived from P. guajava against; Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus. Findings revealed P. guajava possesses significant antibacterial activity at all tested doses; 125, 250, 500 and 1000 μg/ml against tested doses. Pelegrini et al. (2008) revealed that the extracts of P. guajava inhibited the growth of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Morais-Braga et al. (2016b) showed strong activity against Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphyloccocus aureus. The extract showed strong activity against Staphyloccocus aureus exhibiting a MIC value of 256 μg/mL. Huang et al. (2021) showed that chemical constituents isolated from P. guajava inhibited Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Mycobacterium Smegmatis (Table 3).

7.7 Anticough activity

Jaiarj et al. (1999) investigated the anticough mechanism of P. guajava leaf extracts in rats and guinea pigs. A dose of 30 μmol of capsaicin was used to induce cough in rats and guinea pigs (Table 3). Animals in treatment groups were intraperitoneally administered extracts at 1, 2 and 5 g/kg. Findings from this study revealed the suppression of cough in a dose-dependent manner by the extracts. This result emphasizes the therapeutic effect of P. guajava on this disorder.

7.8 Anticancer activity

Lin and Lin (2020) evaluated the anticancer activity of guava seed polysaccharides on MCF-7 cells. Findings from this study revealed the inhibition of MCF-7 cell viability significantly in a dose-dependent manner. dos Santos et al. (2017) investigated the anticancer activity of extracts obtained from red P. guajava. dos Santos et al. (2017) revealed the inhibitory activity of lycopene-rich extract of P. guajava with IC50 value of 29.85 at 5.964 μg/mL. In another study, Zhu et al. (2019) identified compounds exhibiting anticancer activity against HCT116 and HT29 cells. Ashraf et al. (2016) showed the maximum inhibitory activity of P. guajava against cancer cells with IC50 value of less than 30 mg/mL (Table 3). The anticancer activity of P. guajava might be due to the presence of bioactive components; tetracosane, vitamin E, and g-sitosterol (Ryu et al., 2021) (Table 3).

7.9 Antiestrogenic activity

Bazioli et al. (2020) investigated the antiestrogenic effects of extracts fractionated from P. guajava. In vitro and in vivo studies were carried out on 17-β-estradiol inoculated in MCF7 BUS cells and female Wistar rats respectively. 1 × 104 cell mL−1 of MCF7 BUS cells in the presence of 10-9M 17 β-estradiol were treated with 0.3, 0.6, 1.25, and 2.5 μg/mL of fractionated P. guajava extracts. Experimental rats were inoculated with 0.3 mg/kg of 17-β-estradiol and treated with 12.5, 25, and 50 mg/kg of extracts fractionated from P. guajava for 3 days. Results from both in vitro and in vivo assays revealed inhibition of the proliferative activity of 17-β-estradiol upon administration of extracts suggesting its antiproliferative activity (Table 3).

7.10 Toxicological evaluation

Legba et al. (2019) reported that P. guajava does not have any toxic effect on the liver and kidney of Wistar rats. Manekeng et al. (2019) evaluated the possible toxicological effects of methanolic extracts of P. guajava. Findings from this study revealed no mortality from the administration of extracts at 5000 mg/kg on experimental rats (Table 3). Evaluations of haematological parameters showed no significant differences in levels of white blood cells, lymphocytes, monocytes, granulocytes, haemoglobin, haematocrit, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration and mean corpuscular haemoglobin except platelet levels in experimental male rats at 1000 mg/kg. Observation of serum biochemical parameters showed a significant decrease in total protein levels, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total cholesterol, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Manekeng et al. (2019) also reported no significant injuries observed from histopathological evaluations of kidneys of male experimental rats. Information gathered from this study emphasizes the low-toxic nature of P. guajava.

8 Conclusion

This study revealed that many researchers have conducted in-depth in vivo and in vitro studies to validate the acclaimed use of P. guajava in disease prevention, management, and treatment. In their studies, they reported that P. guajava has antioxidant and heptoprotective activities and can be used in the treatment of plethora of health abnormalities such as cough, cancer, bacterial infection, diarrhoea, inflammation, and diabetes. The health-promoting capacity of P. guajava has been linked to the presence of vital phytochemicals, essential oils, and biological active components present in the plant. Based on the beneficial effects of P. guajava as well as its bioactive constituents, it can be exploited in the development of pharmaceutical products and functional foods. However, there is need for comprehensive studies in clinical trials to establish the safe doses and efficacy of P. guajava for the treatment of several diseases.

Funding

No specific funding was provided for this work.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Antimicrobial activity of Psidium guajava L. Fitoterapia. 2002;73(7–8):713-715.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic potential and pharmacological activities of β-eudesmol. Chem Biol Drug Des.. 2021;97(4):984-996.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kaempferol as a Dietary Anti-Inflammatory Agent: Current Therapeutic Standing. Molecules. 2020;25(18):4073.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal activity of phenolic compounds identified in flowers from North Eastern Portugal against Candida species. Future Microbiol.. 2014;9(2):139-146.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- D-limonene: A multifunctional compound with potent therapeutic effects. J Food Biochem.. 2021;45(1):e13566

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Potential usefulness of methyl gallate in the treatment of experimental colitis. Inflammopharmacology.. 2018;26(3):839-849.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition, antioxidant, antitumor, anticancer and cytotoxic effects of Psidium guajava leaf extracts. Pharm. Biol.. 2016;54(10):1971-1981.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oleanolic Acid and Its Derivatives: Biological Activities and Therapeutic Potential in Chronic Diseases. Molecules. 2017;22(11):1915.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Extract of varieties of guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaf modulate angiotensin-1-converting enzyme gene expression in cyclosporine-induced hypertensive rats. Phytomed. Plus.. 2021;1(4):100045

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Banti, C.N., Giannoulis, A.D., Kourkoumelis, N., Owczarzak, A.M., Kubicki, M., Hadjikakou, 2021. S.K. Silver(I) compounds of the anti-inflammatory agents salicylic acid and p-hydroxyl-benzoic acid which modulate cell function. J. Inorg. Biochem. 142,132-144. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2014.10.005.

- Anti-estrogenic activity of guajadial fraction, from guava leaves (Psidium guajava L.) Molecules. 2020;25(7):1525.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Triterpenoids from the leaves of Psidium guajava. Phytochemistry. 2002;61(4):399-403.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents from the leaves of Psidium guajava. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2004;18(2):135-140.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the antidiabetic potential of Psidium guajava L. (Myrtaceae) using assays for α-glucosidase, α-amylase, muscle glucose uptake, liver glucose production, and triglyceride accumulation in adipocytes. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2020;257:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-inflammatory potential of ellagic acid, gallic acid and punicalagin A&B isolated from Punica granatum. BMC Compl. Altern. Med.. 2017;17(1):47.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bezerra, C. F., Rocha, J. E., Do Nascimento Silva, M. K., De Freitas, T. S., De Sousa, A. K., Carneiro, J. N. P., Leal, A. L. A. B., Lucas Dos Santos, A. T., Da Cruz, R. P., Rodrigues, A. S., Sales, D. L., Coutinho, H. D. M., Ribeiro, P. R. V., De Brito, E. S., Da Costa, J. G. M., De Menezes, I. R. A., Almeida, W. D. O., Morais-Braga, M. F. B., 2020. UPLC-MS-ESI-QTOF analysis and anti-candida activity of fractions from Psidium guajava L. South Afr. J. Bot., 131, 421-427.

- Analysis by UPLC-MS-QTOF and antifungal activity of guava (Psidium guajava L.) Food. Chem. Toxicol.. 2018;119:122-132.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of glucosyl transferase inhibitors from Psidium guajava against Streptococcus mutans in dental caries. J. Trad. Comp. Med.. 2018;1–14

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chlorogenic acid attenuates high-carbohydrate, high-fat diet–induced cardiovascular, liver, and metabolic changes in rats. Nutr. Res.. 2019;1–40

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro and in vivo antitumor effects of the essential oil from the leaves of Guatteria friesiana. Planta Med.. 2012;78(5):409-414.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rutin as neuroprotective agent: from bench to bedside. Curr. Med. Chem.. 2019;26(27):5152-5164.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of senescent leaves of guava (Psidium guajava L.) Nat. Prod. Res.. 2021;35(8):1393-1397.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity and free radical-scavenging capacity of extracts from guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaves. Food Chem.. 2007;101:686-694.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxic essential oils from Eryngium campestre and Eryngium amethystinum (Apiaceae) growing in central Italy. Chem Biodivers.. 2017;14(7)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isoquercetin attenuates oxidative stress and neuronal apoptosis after ischemia/reperfusion injury via Nrf2-mediated inhibition of the NOX4/ROS/NF-κB pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact.. 2018;284:32-40.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Quantification of polyphenols and evaluation of antimicrobial, analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of aqueous and acetone-water extracts of Libidibia ferrea, Parapiptadenia rigida and Psidium guajava. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2014;28(156):88-96.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phenolic compounds from Baseonema acuminatum leaves: isolation and antimicrobial activity. Planta. Med.. 2004;70(9):841-846.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Essential oil of Psidium guajava: Influence of genotypes and environment. Sci. Hortic.. 2017;216:38-44.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Methyl gallate: Selective antileishmanial activity correlates with host-cell directed effects. Chem. Biol. Interact.. 2020;320:109026

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Health effects of Psidium guajava L. leaves: An overview of the Last Decade. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2017;18(4):897

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Determination of guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaf phenolic compounds using HPLC-DAD-QTOF-MS. J. Funct. Foods.. 2016;376–388

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An overview on plants cannabinoids endorsed with cardiovascular effects. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2021;142:111963

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- do Nascimento, K.F., Moreira, F.M.F., Alencar Santos, J., Kassuya, C.A.L., Croda, J.H.R., Cardoso, C.A.L., Vieira, M.D.C., Góis Ruiz, A.L.T., Ann Foglio, M., de Carvalho, J.E., Formagio, A.S.N., 2018. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiproliferative and antimycobacterial activities of the essential oil of Psidium guineense Sw. and spathulenol. J Ethnopharmacol. 210, 351-358. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2017.08.030.

- Chemical composition and anti-inflammatory activity of the essential oil from the leaves of Limnocitrus littoralis (Miq.) Swingle from Vietnam. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2021;35(9):1550-1554.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Apoptogenic effects of β-sitosterol glucoside from Castanopsis indica leaves. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2016;30(4):482-485.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of tannins from Geum japonicum on the catalytic activity of thrombin and factor Xa of blood coagulation cascade. J. Nat. Prod.. 1998;61(11):1356-1360.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos Negreiros, P., da Costa, D. S., da Silva, V. G., de Carvalho Lima, I. B., Nunes, D. B., de Melo Sousa, F. B., de Souza Lopes Araújo, T., Medeiros, J., Dos Santos, R. F., de Cássia Meneses Oliveira, R., 2019. Antidiarrheal activity of α-terpineol in miceAntidiarrheal activity of α-terpineol in mice. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019 Feb;110:631-640. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.11.131.

- Lycopene-rich extract from red guava (Psidium guajava L.) displays cytotoxic effect against human breast adenocarcinoma cell line MCF-7 via an apoptotic-like pathway. Food Res. Int.. 2018;105:184-196.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Benzyl isocyanate isolated from the leaves of Psidium guajava inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation. Biofouling. 2020;36(8):1000-1017.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase activity by flavonol glycosides of guava (Psidium guajava L.): A key to the beneficial effects of guava in type II diabetes mellitus. Fitoterapia. 2013;89(1):74-79.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activity of some medicinal plants’ crude juices. Biotechnol. Reports. 2020;28:e00536

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxic and antioxidant constituents from the leaves of Psidium guajava. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2015;25(10):2193-2198.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and biological activities of essential oil from flowers of Psidium guajava (Myrtaceae) Braz. J. Biol.. 2021;81(3):728-736.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Psidium guajava L. spray dried extracts. Ind. Crops Prod.. 2014;60:39-44.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of seven cultivars of guava (Psidium guajava) fruits. Food Chem.. 2015;170:327-335.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms of antidiabetic effects of flavonoid rutin. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017;96:305-312.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anatomical investigation and GC/MS analysis of 'Coco de Mer', Lodoicea maldivica (Arecaceae) Chem Biodivers.. 2020;17(11):e2000707

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- δ-Cadinene, calarene and δ-4-carene from Kadsura heteroclita essential oil as novel larvicides against malaria, dengue and filariasis mosquitoes. Comb. Chem. High. Throughput Screen. 2016;19(7):565-571.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The antitumor effect of hinesol, extract from Atractylodes lancea (Thunb.) DC. by proliferation, inhibition, and apoptosis induction via MEK / ERK and NF - κ B pathway in non – small cell lung cancer cell lines A549 and NCI - H1299. J. Cell. Biochem.. 2019;1–8

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Psidium guajava: A review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2008;117:1-27.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective Effects of Caffeic Acid and the Alzheimer's Brain: An Update. Mini Rev. Med. Chem.. 2017;17(8):667-674.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- β-eudesmol suppresses allergic reactions via inhibiting mast cell degranulation. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol.. 2017;44(2):257-265.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Asiatic acid inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory response in human gingival fibroblasts. Int. Immunopharmacol.. 2017;50:313-318.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal guava (Psidium guajava L. “Crystal”): evaluation of in vitro antioxidant capacities and phytochemical content. Sci. World J. 2020

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative chemical profiles of the essential oils from different varieties of Psidium guajava L. Molecules. 2020;26(1):119.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The antidiarrhoeal evaluation of Psidium guajava L. against enteropathogenic Escherichia coli induced infectious diarrhoea. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2020;251(112561)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Screening of Some Plants Used in the Brazilian Folk Medicine for the Treatment of Infectious Diseases. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2002;97(7):1027-1031.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preventive effects of guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaves and its active compounds against α-dicarbonyl compounds-induced blood coagulation. Food Chem.. 2007;103(2):528-535.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antihyperglycemic and antioxidative potential of Psidium guajava fruit in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2011;49(9):2189-2195.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents of Psidium guajava leaves and their antibacterial activity. Phytochemistry.. 2021;186:112746

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- δ-Cadinene inhibits the growth of ovarian cancer cells via caspase-dependent apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol.. 2015;8(6):6046-6056.

- [Google Scholar]

- Imran, M., Aslam, Gondal, T., Atif, M., Shahbaz, M., Batool, Qaisarani, T., Hanif, Mughal, M., Salehi, B., Martorell, M., Sharifi-Rad, J., 2020. Apigenin as an anticancer agent. Phytother. Res. 34(8), 1812-1828. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6647.

- Anticough and antimicrobial activities of Psidium guajava Linn. leaf extract. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 1999;67(2):203-212.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-inflammatory effects of an ethanolic extract of guava (Psidium guajava L.) leaves in vitro and in vivo. J. Med. Food. 2014;17(6):678-685.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guava leaves extract ameliorates STZ induced diabetes mellitus via activation of PI3K/AKT signaling in skeletal muscle of rats. Mol Biol Rep. 2020;47(4):2793-2799.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Morin alleviates LPS-induced mastitis by inhibiting the PI3K/AKT, MAPK, NF-κB and NLRP3 signaling pathway and protecting the integrity of blood-milk barrier. Int. Immunopharmacol.. 2020;78:105972

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition, in vitro antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of the essential oils of Ocimum gratissimum, O. Sanctum and their major constituents. Indian J. Pharm. Sci.. 2013;75:457-462.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Castalagin and vescalagin purified from leaves of Syzygium samarangense (Blume) Merrill & L.M. Perry: Dual inhibitory activity against PARP1 and DNA topoisomerase II. Fitoterapia.. 2018;129:94-101.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Karatas, O., Balci, Yuce, H., Taskan, M.M., Gevrek, F., Alkan, C., Isiker, Kara, G., Temiz, C., 2020. Cinnamic acid decreases periodontal inflammation and alveolar bone loss in experimental periodontitis. J. Periodontal. Res. 55(5), 676-685. doi: 10.1111/jre.12754.

- α-Copaene is an attractant, synergistic with quercivorol, for improved detection of Euwallacea nr. fornicatus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) PLoS One.. 2017;12(6):e0179416

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective effect of Psidium guajava leaf extract on altered carbohydrate metabolism in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J. Diet Suppl.. 2013;10(4):335-344.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical profile of a polysaccharide from Psidium guajava leaves and it's in vivo antitussive activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2018;109:681-686.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Psidium guajava Linn leaf ethanolic extract: In vivo giardicidal potential with ultrastructural damage, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2021;28(1):427-439.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Volatile constituents from the leaves of Callicarpa japonica Thunb. and their antibacterial activities. J Agric Food Chem.. 2004;52(4):781-787.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eucalyptol Inhibits Amyloid- β -Induced Barrier Dysfunction in Glucose-Exposed Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells and Diabetic Eyes. Antioxidants. 2020;9(1000):1-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quercetin-3-O-α-l-arabinopyranoside protects against retinal cell death via blue light-induced damage in human RPE cells and Balb-c mice. Food Funct.. 2018;9(4):2171-2183.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective effects of polysaccharides from Psidium guajava leaves against oxidative stresses. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2016;91:804-811.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In vivo absorption and disposition of α-cedrene, a sesquiterpene constituent of cedarwood oil, in female and male rats. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet.. 2015;30(2):168-173.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antidiarrheal and protein conservative activities of Psidium guajava in diarrheal rats. J. Integr. Med.. 2019;17(1):57-65.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beta-caryophyllene enhances wound healing through multiple routes. PLoS One. 2019;14(12):e0216104

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pharmacological effects of protocatechuic acid and its therapeutic potential in neurodegenerative diseases: Review on the basis of in vitro and in vivo studies in rodents and humans. Nutr. Neurosci.. 2019;22(2):72-82.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guava (Psidium guajava L.) Leaves : Nutritional composition, phytochemical profile, and health-promoting bioactivities. Foods. 2021;10(752):1-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- The potency of guava Psidium Guajava (L.) leaves as a functional immunostimulatory ingredient. Procedia Chem.. 2015;14:301-307.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activities of essential oil of Psidium Guajava L. leaves. APCBEE Procedia.. 2012;2:86-91.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Potentiating effect of β-caryophyllene on anticancer activity of α-humulene, isocaryophyllene and paclitaxel. J. Pharm. Pharmacol.. 2010;59(12):1643-1647.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toxicological Characterization of Six Plants of the Beninese Pharmacopoeia Used in the Treatment of Salmonellosis. J. Toxicol.. 2019;3530659

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective effects of red guava on inflammation and oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Molecules. 2015;20(12):22341-22350.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guavinoside B from Psidium guajava alleviates acetaminophen-induced liver injury via regulating the Nrf2 and JNK signaling pathways. Food Funct.. 2020;11(9):8297-8308.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical characterization and hepatoprotective effects of a standardized triterpenoid-enriched guava leaf extract. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2021;69(12):3626-3637.