Translate this page into:

Role of C2 methylation and anion type on the physicochemical and thermal properties of imidazolium-based ionic liquids

⁎Corresponding author. im_sutjahja@itb.ac.id (Inge Magdalena Sutjahja)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

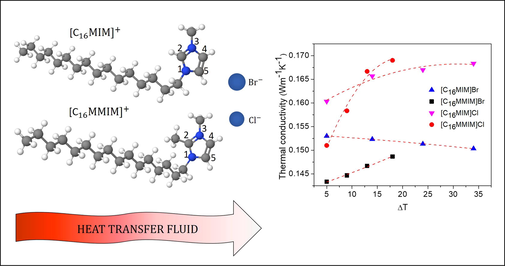

This study focused on the effects of methylation and different anions (Br− and Cl−) on the physicochemical and thermal properties of [C16MIM]X and [C16MMIM]X, belonging to the imidazolium-based ionic liquid (IL) family. The effect of methylation on the transmittance in the fingerprint region of the Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrum was observed as a blue shift, and a new peak associated with the C-N stretching bond was obtained. In contrast, in the functional group region, the frequency shift was related to the change in the vibrational mode from C2-H-X to C2-methyl-X. In general, methylation resulted in an increase in decomposition temperature, an increase in melting temperature, and a decrease in melting enthalpy, leading to a reduction in entropy. The trends observed for the decomposition temperature, melting temperature, and melting enthalpy with different anions depended on the strength of the Brønsted acids and hydrogen bonds of the Br− and Cl− based anions. The thermal conductivity of the methylated ILs increased with an increase in temperature. In contrast, for the non-methylated (protonated) ILs, the thermal conductivity of [C16MIM]Br decreased with an increase in temperature, while the opposite trend was observed for [C16MIM]Cl. The data were compared with those of the short alkyl chain and weakly coordinating anion of NTf2. The analysis was performed considering different phases, the prominent role and different behaviour in the hydrogen bonding at the C2 position of the imidazolium ring upon methylation, and the significant change in viscosity, which can influence the IL structure.

Keywords

Methylation

Imidazolium-based ionic liquid

Thermal properties

Thermal conductivity

Nomenclature

-

entropy (J/(g⋅K)

- Tm

-

melting temperatures (K)

-

melting enthalpy (J/g)

-

thermal conductivity (W/(m⋅K))

- T

-

temperature (K)

- t

-

time (s)

-

heat flux (W/m2)

- ρ

-

density (g/mL)

- Td

-

decomposition temperature (K)

- η

-

viscosity (mPa⋅s)

- σ

-

electrical conductivity (mS/cm)

- ν

-

wavenumber (cm−1)

- I

-

intensity (%)

- {a, b, c} and {A, B, C}

-

regression coefficients for each fitting formula in Eq. (3),(4)

- TES

-

Thermal Energy Storage

- HTF

-

Heat Transfer Fluid

- PCM

-

Phase Change Material

- FT-IR

-

Fourier Transform Infrared

- DSC

-

Differential Scanning Calorimetry

- TG

-

Thermogravimetric

- IL

-

Ionic Liquid

- [C16MIM]

-

1-hexadecyl-3-methylimidazolium

- [C16MMIM]

-

1-hexadecyl-2,3-dimethyl-imidazolium

- [CnMIM]

-

1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium

- [CnMMIM]

-

1-alkyl-2,3-dimethyl imidazolium

Abbreviation

1 Introduction

Ionic liquids (ILs) possess several unique and superior physical properties, such as the low flammability, very low vapour pressure, wide liquidus range, high electrical conductivity and mobility, wide electrochemical window, and high thermal and chemical stabilities, all of which support their use in a wide variety of applications. ILs have been used as green solvents in organic chemistry (Kaur et al., 2022; Singh and Savoy, 2020), azeotropic mixture separation (Bai et al., 2019; Wen et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2018), gas separation (Ren et al., 2018; Sharma et al., 2012), and biomass pre-treatment (Socha et al., 2014). They have been also used as reaction catalysts (Vekariya, 2017), electrolytes in alternative energy generation/storage energy devices (Greer et al., 2020; Jónsson, 2020), and media for thermal energy storage (TES) (Kaur et al., 2022). For TES application, ILs have been proposed as suitable heat transfer fluids (HTFs) (Franca et al., 2018; Minea, 2020; Wadekar, 2017; Wang et al., 2018) and phase change materials (PCMs) that can store or release relatively large amounts of latent heat via solid-liquid or liquid-solid phase transitions (Bai et al., 2011; Das et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2009).

The anion and cation of ILs have a major influence on their structures and physicochemical properties (Fumino et al., 2014; Prykhodko et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2009). In imidazolium-based ILs, cations consist of alkyl chains attached to imidazolium rings, while anion can be simple inorganic ions, complex inorganic molecules, or organic molecules (Sun and Armstrong, 2018). The intermolecular interactions between cation and anion are determined by the complex interplay between the hydrogen bonding, Coulomb forces, and dispersion forces (Fumino et al., 2014). The size (Hunt, 2007; Hunt et al., 2007; Ramya et al., 2015) and charge density (Hunt et al., 2007; Hunt and Gould, 2006) of anion are important factors that qualitatively and quantitatively influence various ionic interactions. These factors subsequently determine the various thermodynamic and transport properties of ILs (Izgorodina et al., 2014, 2011; Sánchez-Badillo et al., 2019).

A common variation in this imidazolium-based cation is the alkyl chain length of the imidazolium cation. The effect of the alkyl chain length on the thermophysical properties is a non-monotonous increase in the melting temperatures (Anggraini et al., 2020; Murray et al., 2010; Serra et al., 2017) and thermal conductivity (Anggraini et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2014), while the glass temperature has an even-odd pattern (Anggraini et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2014), with no clear pattern for the melting enthalpy (Anggraini et al., 2020; Serra et al., 2017). In particular, the long alkyl chains of the imidazolium cation are of significant interest because they can form liquid crystalline phases (Wang et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2010) during the solid-to-liquid phase transition. In addition to their application as PCMs (Bai et al., 2011), the large thermal stability range of this liquid crystal phase allows the use of linear and long alkyl chain imidazolium-based ILs as solvents for chemical reactions as the ordered nature of the solvent might have a catalytic role (Binnemans, 2005). From crystalline solid state at low temperature, increasing the temperature leads to crystal to liquid crystal transition at the melting temperature followed by a liquid crystal to an isotropic liquid at the clearing point. The latter is mainly caused by the van der Waals breakup between the alkyl chains (Xu et al., 2010). Izgorodina et al. (2014) reported that for ionic liquid melting temperatures, the short-length alkyl chain is dominated by cation-anion interactions. Increases in chain length, shifts the dominance toward interactions between chains, with the exact alkyl length depending on the particular combination of cation and anion.

Besides the variation in the length of the alkyl chain of the cation, variations in the cation can be achieved through methylation. A methylation is a form of modification of the imidazolium cation by replacing the hydrogen atom (H) in position 2 (C2), with a methyl group (–CH3) (Endo et al., 2010). Dong et al. (2016) stated that hydrogen atoms bound to carbon at positions C2, C4, and C5 have a more positive charge, whereas those bound to nitrogen atoms at N1 and N3 have more negative charges because of the difference in electronegativity of N and C. C2 is more acidic/positive compared to C4 and C5 because there is a deficit in electrons within the bond, such that any anion will be more strongly bound at C2 (Noack et al., 2010). Due to methylation, the presence of the methyl group prevents any interaction between an anion and the C2 carbon (Izgorodina et al., 2011). Consequently, the anion tends to interact with the carbon at the C4/C5 position. The loss of hydrogen in C2 after methylation leads to a drastic change in physicochemical properties. According to the thermodynamic relation, the entropy (S) is related to the melting temperatures (Tm) and melting enthalpy (Hm) according to:

Thermodynamically, the loss of this hydrogen bonding interaction could be expected to lead to a reduction in the melting temperatures and a decrease in viscosity; however, the opposite is observed experimentally. Some models have been proposed to explain the changes in thermophysical parameters due to methylation. According to entropy theory (Hunt, 2007; Koutsoukos et al., 2022), methylation reduces the anion-cation interaction energy, thus reducing entropy and contributing to the increased phase transition temperatures. Izgorodina et al. (2011) as confirmed by Koutsoukos et al. (2022) concluded that the relatively high potential energy surface of methylated imidazolium ILs, which is far above their thermal energy, is responsible for restricting ion transport in the liquid state. Thus, ion movement is limited to only a small oscillation, thereby inhibiting the overall ion transport. The defect hypothesis of Fumino et al. (2014) assumed that hydrogen bonds can be regarded as ‘‘defects’’ within the Coulomb network of ILs. These defects increase the dynamics of the cation and anion, leading to lower melting temperatures and viscosities. Thus, replacing protons with methyl groups during methylation will reduce the number of hydrogen bonds, and increase the melting temperatures and viscosity. Chen and Lee (2014) proposed a free volume model that explains why the decreased free volume of methylated imidazolium ILs reduces the number of hole carriers for molecular transport, while simultaneously causing a significant increase in viscosity has previously been reported. Through the decrease in entropy due to C2-methylation, this model succeeded in predicting the increase in melting temperatures and correlated with properties such as surface tension, density, refractive index, and electrical conductivity.

For optimum performance of ILs in particular applications that concerning thermal aspect, the thermal conductivity parameter which is related to the ability of a material to transfer heat plays the most important role. In general, the mechanism for the thermal conductivity of a liquid is related to molecular diffusion or collisions between molecules (Kreith, 2011). Similar to the thermophysical parameters mentioned above, as shown in Table 1, the thermal conductivity of imidazolium-based ILs depends on the alkyl chain lengths of the cation and the anion. As seen in Table 1, there is a weak dependence of thermal conductivity on temperature, with a tendency to decrease with increasing temperature. To the best of our knowledge, no study has reported experimental thermal conductivity values for simple anions, such as Cl− and Br−. For a specific type of ILs, besides the dependence on temperature, thermal conductivity also depends on the chemical substance added to the IL to form a stable suspension (Oster et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2011). Thus far, reports on thermal conductivity are limited, perhaps due to the complexity of the measurement, particularly for ILs with a relatively high melting temperature. From theoretical point of view, the development of models to predict the thermal conductivity of ILs were based on topological index method (Balaban, 1982; Chen et al., 2014; Harry, 1947; Hosoya, 1971; Randić, 1975) and reverse non-equilibrium molecular dynamics simulation method (Liu et al., 2012; Sánchez-Badillo et al., 2019). However, the validity of the methods should be proved by the agreement between experimental and calculated data for many thermal conductivities of ILs for various types of cations and anions.

ILs, the length of alkyl chain

Anion (X)

NTf2 (*)

BF4 (**)

PF6 (***)

k (W/(m⋅K))

T (K)

Ref.

k (W/(m⋅K))

T

Ref.

k (W/(m⋅K))

T

Ref.

[C2MIM]

0.130

293

(Ge et al., 2007)

0.130

303

0.129

313

0.129

323

0.129

333

0.129

343

0.128

353

0.1208

273.15

(Fröba et al., 2010)

0.1206

283.15

0.1202

293.15

0.1215

303.15

0.1195

313.15

0.1184

323.15

0.1190

333.15

0.1194

343.15

0.1191

353.15

[C4MIM]

0.128

293

(Ge et al., 2007)

0.169

294.7

(Tomida et al., 2007b)

0.145

293

(de Castro et al., 2010)

0.127

303

0.169

314.8

0.145

303

0.127

313

0.168

334.9

0.145

313

0.126

323

0.144

323

0.125

333

0.143

333

0.124

343

0.143

343

0.124

353

0.143

353

0.1264

296.24

(Liu et al., 2012)

0.145

294.9

(Tomida et al., 2007a)

0.1256

312.77

0.145

315.0

0.1232

332.36

0.144

335.1

[C6MIM]

0.127

293

(Ge et al., 2007)

0.158

293

(de Castro et al., 2010)

0.142

293

(de Castro et al., 2010)

0.127

303

0.157

303

0.141

303

0.127

313

0.156

313

0.141

313

0.126

323

0.155

323

0.139

323

0.125

333

0.153

333

0.139

333

0.125

343

0.152

343

0.138

343

0.125

353

0.151

353

0.138

353

0.1238

273.15

(Fröba et al., 2010)

0.166

294.2

(Tomida et al., 2012)

0.145

294.1

(Tomida et al., 2007a)

0.1224

283.15

0.165

314.3

0.145

315.1

0.1219

293.15

0.164

334.4

0.144

335.2

0.1237

303.15

0.1220

313.15

0.1201

323.15

0.1208

333.15

0.1212

343.15

0.1209

353.15

[C8MIM]

0.128

293

(Ge et al., 2007)

0.164

294.2

(Tomida et al., 2012)

0.145

295.1

(Tomida et al., 2007a)

0.128

303

0.163

314.3

0.145

315.1

0.128

313

0.160

334.4

0.144

335.2

0.126

323

0.126

333

0.125

343

0.126

353

In this paper, we describe an experimental study on the effects of methylation and anion type on the physicochemical and thermal parameters (decomposition and melting temperatures, melting enthalpy, and thermal conductivity) of long-chain imidazolium-based ILs, namely 1-hexadecyl-3-methylimidazolium and 1-hexadecyl-2,3-dimethyl-imidazolium-based cations, with different anions of Br and Cl. To the best of our knowledge, the effect of methylation on the thermal conductivity of imidazolium-based ILs has never been reported before, although a clear difference in thermal conductivity with temperature variation was observed for [C4MIM]NTf2 (Ge et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2012) and [C4MMIM]NTf2 (Liu et al., 2012). The experimental data were compared with those obtained from previous studies, and the analyses were performed based on the available models for ILs with the same or different alkyl chains. A correlation study between the IL structures obtained from previous studies and the thermal property data obtained in this study was performed considering all fundamental interactions associated with the imidazolium IL.

2 Materials and methods

The ILs consisted of 1-hexadecyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide or [C16MIM]Br with chemical formula C20H39BrN2 (molecular weight, MW: 387.44), 1-hexadecyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride or [C16MIM]Cl with chemical formula C20H39ClN2 (MW: 342.99), 1-hexadecyl-2,3-dimethyl-imidazolium bromide or [C16MMIM]Br with chemical formula C21H43BrN2 (MW: 403.48), and 1-hexadecyl-2,3-dimethyl-imidazolium chloride or [C16MMIM]Cl with chemical formula C21H43ClN2 (MW: 359.03). The chemicals were purchased from Wuhu Nuowei Chemistry and each sample had a purity of 98%.

The Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra of the ILs were obtained using a Bruker Tensor-27 FT-IR spectrophotometer at a scanning number of 30, using the KBr sampling method. The thermal analysis is based on thermogravimetric (TG) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements. TG measurement was performed using a TG 209 F1 Libra instrument, while DSC measurement was carried out using PerkinElmer DSC 4000 Series instrument, both under a nitrogen atmosphere (20 mL/min). For TG, samples between 5 and 7 mg were heated from room temperature to 700 K, while for DSC, samples between 3 and 5 mg were heated from 250 K to 470 K, both at a constant heating rate of 5 K/min.

The thermal conductivity measurement was performed using a KS-1 sensor from KD2Pro thermal analyser from Decagon that provides an accuracy value of ± 5%. The device works based on the transient hot-wire method (Healy et al., 1976) to determine the fluid’s thermal properties. The sensor simultaneously acts both as the heating element and the temperature sensor. During the measurement, the temperature (T) vs. time (t) was recorded, and using the heat flux (q), the thermal conductivity could be calculated as (Healy et al., 1976):

In this study, the thermal conductivity (k) of the liquid ILs was measured at a temperature of 3–5 K above the melting transition peak from the DSC curves to ensure the perfect melting of the ILs. Details of the heating system for the present thermal conductivity measurements are described in our previous publication (Anggraini et al., 2021). The thermal conductivity measurements were repeated three times for all samples to ensure the repeatability of the data.

3 Results and discussion

The structures of the ILs used in this study are shown in Fig. 1 (a) for non-methylated (protonated) and Fig. 1 (b) for methylated ILs. The structure was generated using MolView (Smith, 1995).![Chemical structure of: (a) [ C 16 M I M ] + and (b) [ C 16 M M I M ] + cations and the anions ( X - ) consists of B r - or C l - . The blue circle in cation ring indicates the nitrogen atom.](/content/184/2022/15/8/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103963-fig2.png)

Chemical structure of: (a)

and (b)

cations and the anions (

consists of

or

. The blue circle in cation ring indicates the nitrogen atom.

3.1 FT-IR spectra

The resulting FT-IR spectra are presented in Fig. 2 for spectra in the ranges of (a) 400–4000 cm−1, (b) 3000–4000 cm−1, (c) 1500–3000 cm−1, and (d) 400–1500 cm−1, while Table 2 presents the IR peak values.![The FT-IR spectra of [C16MIM]Br (A), [C16MMIM]Br (B), [C16MIM]Cl (C), and [C16MMIM]Cl (D) ILs in the ranges: (a) 400–4000 cm−1, (b) 3000–4000 cm−1, (c) 1500–3000 cm−1, and (d) 400–1500 cm−1.](/content/184/2022/15/8/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103963-fig3.png)

The FT-IR spectra of [C16MIM]Br (A), [C16MMIM]Br (B), [C16MIM]Cl (C), and [C16MMIM]Cl (D) ILs in the ranges: (a) 400–4000 cm−1, (b) 3000–4000 cm−1, (c) 1500–3000 cm−1, and (d) 400–1500 cm−1.

[C16MIM]Br (A)

[C16MMIM]Br (B)

[C16MIM]Cl (C)

[C16MMIM]Cl (D)

Type of vibration *)

(cm−1)

I (%)

(cm−1)

I (%)

(cm−1)

I (%)

(cm−1)

I (%)

3575

85

3585

97

3569

85

3589

72

Ring C2-H-Br/ C2-methyl-Br/ C2-H-Cl/ C2-methyl-Cl str

3468

52

3468

56

3468

53

3468

46

3426

53

3385

73

3412

56

3371

50

3149

72

3110

58

3149

75

3107

49

Ring CH str

3082

46

3053

42

3082

48

3046

38

2927

40

2927

33

2927

40

2927

30

Ring CH3, CH2, CH str

2855

44

2851

36

2855

46

2852

33

1770

100

1785

100

1789

100

1795

100

Ring CH bend

1630

59

1589

58

1638

62

1594

52

Ring CH2(N) and CH3(N) CN str

1574

54

1587

49

1574

54

1587

45

1543

53

1543

53

Ring NC(CH3)N CC str

1471

52

1470

41

1471

52

1470

39

Ring ip asymmetry str, CH3(N)CN str

1171

52

1140

58

1178

53

1146

59

Ring CH2(N) and CH3(N) CN str, CC str

1042

61

1042

63

Ring CH2(N) and CH3(N)CN str

863

61

859

60

Ring NC(H)N CH bend, CCH bend, hexadecyl chain bend

790

60

800

50

802

63

806

54

Ring HCCH asymmetry bend, CH2(N) and CH3(N) CN bend

718

59

723

50

715

59

718

49

From Fig. 2, one can see that the transmittance measured within the fingerprint region (Fig. 2(d)) is marked by the generation of a new peak at 1042 cm−1 for methylated ILs (B, D), associated with the CH2(N) and CH3(N)CN stretching bond as a characteristic of the alkyl chain of cation (Noack et al., 2010). Fig. 2(c) highlights the CH3, CH2, and C-H stretching rings (Bai et al., 2011); one can see the similarity between the transmittance peaks of methylated and protonated ILs. In this case, the peaks at about 1574 cm−1 for protonated ILs (A, C) underwent a blue shift to 1587 cm−1 after methylation (B, D), due to CH2(N) and CH3(N) CN stretching (Noack et al., 2010). The broad peak at 2927 cm−1 is associated with CH3, CH2, and C-H stretching (Bai et al., 2011).

The wavenumber range from 3000 − 4000 cm−1 (Fig. 2(b)) shows the shift in peak that occurred due to methylation and cation–anion interaction. The peak at approximately 3082 cm−1 for protonated ILs (A, C) undergoes a red shift to 3053 cm−1 and 3046 cm−1 for methylated ILs (B and D, respectively). The difference between the spectra before and after methylation, is the broadening in the absorption peak at approximately 3468 cm−1 for protonated ILs (A, C). For the Br anion, a red shift from 3426 to 3385 cm−1 and a blue shift from 3575 to 3582 cm−1 occurred, while slightly greater shifts were observed for the Cl anion; that is, 3412 to 3371 cm−1 and 3569 to 3589 cm−1. It is worth mentioning that methylation eliminated hydrogen bonding at the predominant interaction site at C2 (Haddad et al., 2018). A red shift occurs because of the rearrangement and relocation of the cation-nion interaction at the C4/C5 positions which is related to the electron distribution in the imidazolium ring. An increase in electron density at C4/C5 is evident due to the upfield shift in both the 1H NMR (Haddad et al., 2018; Noack et al., 2010) and 13C NMR spectra (Noack et al., 2010), leading to the inductive effect of the added methyl group and charge transfer via the new hydrogen bond. Nitrogen atoms have higher electronegativity than carbon or hydrogen atoms and therefore withdraw electrons from this system. The blue shift is attributed to a nitrogen atom drawing electrons to itself, which causes an increase in the partial negative charges on the nitrogen atoms, leading to stronger attraction of their bonding partners as indicated by C-N stretching (Noack et al., 2010). Clearly, the red shift indicates the formation of a hydrogen bond, while the blue shift is a result of the charge redistribution along the non-hydrogen-bonded C-H bonds.

3.2 Thermal properties

3.2.1 Decomposition and phase transition behaviour

Fig. 3 shows the characteristic decomposition curves, while Fig. 4 shows the characteristic phase transition behaviour of ILs [C16MIM]Br (A), [C16MMIM]Br (B), [C16MIM]Cl (C), and [C16MMIM]Cl (D).![TG-Differential TG (DTG) curve of [C16MIM]Br (A), [C16MMIM]Br (B), [C16MIM]Cl (C), and [C16MMIM]Cl (D) ILs.](/content/184/2022/15/8/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103963-fig4.png)

TG-Differential TG (DTG) curve of [C16MIM]Br (A), [C16MMIM]Br (B), [C16MIM]Cl (C), and [C16MMIM]Cl (D) ILs.

![DSC thermograms of [C16MIM]Br (A), [C16MMIM]Br (B), [C16MIM]Cl (C), and [C16MMIM]Cl (D) ILs. The arrows show the temperature range for thermal conductivity measurement.](/content/184/2022/15/8/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103963-fig5.png)

DSC thermograms of [C16MIM]Br (A), [C16MMIM]Br (B), [C16MIM]Cl (C), and [C16MMIM]Cl (D) ILs. The arrows show the temperature range for thermal conductivity measurement.

The results of decomposition temperature (Td), melting temperatures (Tm), and melting enthalpies (Hm) and entropy (S) that calculated using Eq. (1) are tabulated in Table 3 that also presents a compilation of the thermophysical parameters of protonated ([CnMIM]X) and methylated ([CnMMIM]X) imidazolium-based-ILs.

ILs

ρa

Tmb

Hmc

Sd

Tde

ηf

σg

T (K)

Ref.

[C2MIM]NTf2

i1.52

258.3

587

ii21.0

i293; ii298

(Noack et al., 2010)

i1.520

ii34

ii8.8

i295; ii293

(Bonĥte et al., 1996)

[C2MMIM]NTf2

i1.49

295.0

639

ii74.0

i293; ii298

(Noack et al., 2010)

i1.495

ii88

ii3.2

i295; ii293

(Bonĥte et al., 1996)

[C3MIM]I

i1.49; ii1.49

i35; ii30

i12.6; ii14.6

i358; ii363

(Izgorodina et al., 2011)

[C3MMIM]I

i1.45; ii1.44

i195; ii148

i1.95; ii2.48

i358; ii363

(Izgorodina et al., 2011)

[C3MIM]BF4

1.24

256

708

103

5.9

298

(Nishida et al., 2003)

[C3MMIM]BF4

1.13

256

715

330

1.7

Room Temp.

(Min et al., 2007)

[C4MIM]I

270

(Nakakoshi et al., 2006)

1.44

201

538

1110

298

(Huddleston et al., 2001)

47

298

(Okoturo and VanderNoot, 2004)

[C4MMIM]I

370.8

77.1*

0.208**

(Endo et al., 2010)

[C4MIM]NTf2

i1.43

186.8

595

ii27.9

i293; ii298

(Noack et al., 2010)

44

298

(Hyun et al., 2002)

51.5

298

(McLean et al., 2002)

i1.4334

ii40.6

i302.80; ii302.93

(Jacquemin et al., 2006)

1.43

712

69

298

(Huddleston et al., 2001)

[C4MMIM]NTf2

i1.42

271

632

ii95.0

i293; ii298

(Noack et al., 2010)

[C4MIM]BF4

1.17

233

1.7

293

(Carda–Broch et al., 2003)

i1.206; ii1.202; iii1.198

i136.2; ii99.6; iii75.3

i2.8; ii3.6; iii4.5

i293; ii298; iii303

(Tokuda et al., 2006)

i1.1975

ii75.4

i302.77; ii303.22

(Jacquemin et al., 2006)

1.12

676

219

298

(Huddleston et al., 2001)

92

298

(Okoturo and VanderNoot, 2004)

1.14

293

(Zhao et al., 2004)

[C4MMIM]BF4

313.1

72.5*

0.232**

(Endo et al., 2010)

1.03

294

674

372

0.7

Room Temp.

(Min et al., 2007)

267.1

41.7

(Fox et al., 2003)

[C4MIM]PF6

285.3

46.8*

0.164**

(Endo et al., 2010)

1.36

312

1.4

293

(Carda–Broch et al., 2003)

i1.36

283

622

i450

i298

(Huddleston et al., 2001)

280.8

46.3

(Fox et al., 2003)

280.03

70.1*

(Troncoso et al., 2006)

i1.373; ii1.368; iii1.365

i354.0; ii249.6; iii182.4

i2.8; ii3.6; iii4.5

i293; ii298; iii303

(Tokuda et al., 2006)

282

42*

(Jin et al., 2008)

276.43

32.4*

(Doman and Marciniak, 2003)

ii1.3620

i209.1

i302.61; ii302.73

(Jacquemin et al., 2006)

283.51

68.97*

(Kabo et al., 2004)

0.32

298.15

327.17

(Fredlake et al., 2004)

[C4MMIM]PF6

293.6

30.2*

0.103**

(Endo et al., 2010)

0.55

298.15

327.21

(Fredlake et al., 2004)

289

2312

296

(Strehmel et al., 2006)

311.8

57.31*

(Henderson et al., 2006)

[C4MIM]Br

57

7.34

373

(Izgorodina et al., 2011)

353

121.9*

0.345**

(Endo et al., 2010)

107.7*

(Nishikawa et al., 2007)

351.35

104.42*

0.297**

(Paulechka, 2007)

[C4MMIM]Br

163

1.75

373

(Izgorodina et al., 2011)

349.66

66.977

(Zhu et al., 2009)

369.8

117.9*

0.319**

(Endo et al., 2010)

365.7

86.8

(Fox et al., 2003)

[C4MIM]Cl

342.3

120.2*

0.351**

(Endo et al., 2010)

i1.08

314

527

i298

(Huddleston et al., 2001)

326.57

59.004

(Zhu et al., 2009)

330

83.0*

(Nishikawa et al., 2007)

341.95

80.48*

(Doman, 2003)

341

148.05*

0.441**

(Yamamuro et al., 2006)

398.1

(Muhammad, 2016)

i40890; ii11000; iii105

i293.0; ii303.0; iii363.0

(Seddon et al., 2002)

i1.0575; ii1.0548; iii1.0465

i256.7; i189.4; iii85.65

i343.15; ii348.15; iii363.15

(Vieira et al., 2019)

[C4MMIM]Cl

372.5

97.5*

0.262**

(Endo et al., 2010)

365.89

76.384

(Zhu et al., 2009)

369.8

97.9

(Fox et al., 2003)

369.0

77.00*

(Henderson et al., 2006)

540

(Muhammad, 2016)

[C6MIM]Cl

i18000; ii6416; iii114

i293.0; ii303.0; iii363.0

(Seddon et al., 2002)

[C8MIM]Cl

i33070; ii10770; iii172

i293.0; ii303.0; iii363.0

(Seddon et al., 2002)

[C16MIM]Br

337.06

152.563

(Zhu et al., 2009)

336.46

144.37

(Bai et al., 2011)

339.0

169.3*

(Bradley et al., 2002)

447

(Li and Chen, 2011)

337.82^

243.17

0.74

523

p.w

[C16MMIM]Br

371.7

126.616

(Zhu et al., 2009)

370.68

121.12

(Bai et al., 2011)

372.86^

145.20

0.40

534

p.w

[C16MIM]Cl

336.44

159

535.7

(Maja et al., 2019)

338

(Li et al., 2005)

339.7

174.1*

(Bradley et al., 2002)

341

(Zhao et al., 2009)

340.38^

235.54

0.71

512

p.w

[C16MMIM]Cl

370.60^

187.16

0.52

521

p.w

Compared to previous studies, Td of [C16MIM]Br and [C16MIM]Cl from the present study are in good agreement with the data of previous studies (Li and Chen, 2011; Maja et al., 2019). The melting temperatures of [C16MIM]Br and [C16MMIM]Br are in agreement with those reported by Bai et al. (2011), Bradley et al. (2002), and Zhu et al. (2009), although the melting enthalpies are slightly higher. For [C16MIM]Cl, the melting temperature was in accordance with Bradley et al. (2002), Li et al. (2005), Maja et al. (2019), and Zhao et al. (2009), although the melting enthalpy in the present work was higher than Bradley et al. (2002) and Maja et al. (2019). As shown in Fig. 4, the DSC thermogram of [C16MMIM]Br shows two endothermic peaks at 367 K (with a large enthalpy) and 270 K (with a small enthalpy), each of which corresponds to the melting enthalpy and solid–solid phase transition. The same phenomenon was not observed in previous studies of the same ILs (Bai et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2009), but was clearly observed in [C18MIM]PF6 and [C14MIM]PF6 ILs (Xu et al., 2012). According to Zhu et al. (2009), the phase transitions of [C16MIM]Br and [C16MMIM]Br are rather simple; they readily crystallise and do not form glasses. On the other hand, [C16MIM]Cl appears to show a more complex phase behaviour than simple melting/crystallisation, with a phase transition that depends on the initial state and cooling rate (Li et al., 2005; Maja et al., 2019). Moreover, a transition from smectic to isotropic liquid phase has already been reported by Bowlas et al. (1996), Bradley et al. (2002), and Zhao et al. (2009) at approximately 220 °C, 222.2 °C, and 185 °C, respectively. We note that our present data do not show any sign for this transition.

The methylation process resulted in several changes in the physicochemical properties, mainly an increase in the melting temperature, decomposition temperature, and viscosity, while decreasing the density, entropy, and electrical conductivity (Table 3). The thermal stability depends on the Brønsted acid strength and decreases with an increase in coordination, nucleophilicity, and hydrophilicity of the anion (Cao and Mu, 2014; Kütt et al., 2011). In addition, the effect of the anion on the melting temperature, enthalpy, viscosity, and electrical conductivity is clear. For example, at 293 K, the viscosity of [C4MIM]X with Cl− was higher than that in the case wherein other anions are used. In addition, as the alkyl chain length increased, the decomposition temperature tended to decrease, while the trend of the density variation was not as clear as that of viscosity. With an increase in temperature, the viscosity and thermal conductivity decreased (Table 1), unlike the electrical conductivity (Izgorodina et al., 2011).

An increase in the decomposition temperature owing to methylation was recorded for all alkyl chain lengths and for different types of anions, which clearly indicated the higher thermal stability of methylated ILs. The decrease in entropy with methylation is consistent with Hunt’s entropy theory (Hunt, 2007) and Fumino’s defect hypothesis (Fumino et al., 2014). From a physical point of view, methylation alters the electron density distribution and, consequently, changes the positions of the interionic interactions, resulting in a more stable and packed molecular network with increased Coulomb interactions and decreased van der Waals interactions (Noack et al., 2010). According to Zahn et al. (2008) based on static quantum chemical and molecular dynamics simulations, strong hydrogen bonding at the C2 position of protonated samples limited the mobility of the anion and results in a lower melting temperature compared to the methylated sample.

For protonated and methylated ILs, the obtained experimental data revealed a higher thermal stability of ILs with Br anion as compared to those with Cl anion, which can be explained considering the strength of the Brønsted acids used and the associated pKa values. Considering HBr and HCl as the Brønsted acids of Br− and Cl−, respectively, HBr is a stronger acid than HCl in various solvents, such as water and dimethyl sulfoxide (Kütt et al., 2011; Trummal et al., 2016). For example, the average values of pKa (water) for HBr and HCl are −8.8 and −5.9, respectively (Trummal et al., 2016). The variation of melting temperatures and enthalpy melting with anions of protonated ILs are also consistent with available models. Generally, the ionic radius of Cl (2.70 Å) is smaller than that of Br (3.12 Å) (Zhang et al., 2006), and the electronegativity of Cl− anion is larger than that of Br− anion (Sanchora et al., 2019). Hence, the hydrogen bonds of ILs containing Cl anion were stronger than those of ILs with Br anion (Sanchora et al., 2019). This implies that ILs with Cl anion have a higher melting temperature than ILs with Br anion. According to Khudozhitkov (2022), stronger hydrogen bonds between the cation and anion lead to a lower heat of fusion. This hypothesis is in accordance with the results of the present study on protonated ILs. The opposite trends for methylated ILs suggest different mechanisms, owing to the replacement of hydrogen with methyl groups, as explained in the previous paragraph.

3.2.2 Thermal conductivity

Fig. 5 show the temperature-dependent thermal conductivities of [C16MIM]Br, [C16MMIM]Br, [C16MIM]Cl, and [C16MMIM]Cl, respectively. In addition, for comparison purposes, the temperature-dependent thermal conductivities of [C4MIM]NTf2 and [C4MMIM]NTf2 from previous studies (Ge et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2012) are also presented here, as shown in Fig. 6.![Temperature-dependent thermal conductivity of: [C16MIM]Br (A), [C16MMIM]Br (B), [C16MIM]Cl (C), and [C16MMIM]Cl (D). The dash red lines represent the results of fitting the data using Eq. (3) and Eq. (4). Open symbols: individual data from three repetitive experiments, closed symbols: the average and standard deviation values.](/content/184/2022/15/8/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103963-fig6.png)

Temperature-dependent thermal conductivity of: [C16MIM]Br (A), [C16MMIM]Br (B), [C16MIM]Cl (C), and [C16MMIM]Cl (D). The dash red lines represent the results of fitting the data using Eq. (3) and Eq. (4). Open symbols: individual data from three repetitive experiments, closed symbols: the average and standard deviation values.

From Figs. 5 and 6, the temperature-dependent thermal conductivities of [C16MIM]Br and [C4MIM]NTf2 revealed a decrease in k with an increase in T, unlike the trend demonstrated by [C16MIM]Cl, [C16MMIM]Br, [C16MMIM]Cl, and [C4MMIM]NTf2. Using the available fitting formula proposed by Coker (2007), the temperature-dependent thermal conductivities of [C16MIM]Br and [C4MIM]NTf2 were fitted using (3), which is commonly used to fit the data for liquid and solid organic compounds that show a decrease in k with an increase in T. The remaining data were fitted using (4), which is used for many inorganic liquids, including water, which show an increase in k with an increase in T.

Regression Coeff.

[C16MIM]Br

Regression Coeff.

[C16MMIM]Br

[C16MIM]Cl

[C16MMIM]Cl

a

0.27

A

0.21

3.48

10−3

7.98

b

3.15

10−4

B

7.32

10−4

7.38

10−4

0.04

c

3.39

10−7

C

1.49

10−6

7.57

10−7

5.27

10−5

1.28

10−8

3.51

10−8

1.95

10−7

6.85

10−7

0.99

0.99

0.97

0.99

Regression Coeff.

[C4MIM]NTf2 (Ge et al., 2007)

[C4MIM]NTf2 (Liu et al., 2012)

Regression Coeff.

[C4MMIM]NTf2 (Liu et al., 2012)

a

0.22

0.22

A

0.26

b

2.87

10−4

2.84

10−4

B

9.26

10−4

c

4.29

10−7

4.56

10−7

C

1.55

10−6

10−7

2.00

10−7

0

0.90

0.89

1.00

The relatively small chi-square (χ2) and R2 parameter values which are close to 1 (Tables 4 and 5), show that the data fitted well, despite the possibility that [C16MIM]Cl and [C16MMIM]Cl might be in the liquid crystalline phase at the selected temperature range for the thermal conductivity measurement.

The thermal conductivity data presented in Figs. 5 and 6 indicated the following: i) the increase in the thermal conductivity of methylated ILs with temperature; ii) the influence of anion on the magnitude and temperature dependence of the thermal conductivity of protonated ILs. Further analysis is provided using the existing simulation or theoretical model for short alkyl chains of imidazolium ILs, considering the cation and anion interactions that contributed to the hydrogen bond, Coulomb interaction, and dispersion force. Previous experimental data have shown that anions contribute more significantly to the cation-anion interaction and the physical and electronic properties of imidazolium ILs (Cao and Mu, 2014; Panja, 2020), which is also supported by the fact that the vibrational modes of these imidazolium-based ILs do not vary substantially with the variation in the alkyl chain length, and it can be concluded that the interaction energies between cation and anion may be approximately similar for these ILs (Panja, 2020).

As shown in Fig. 5, at approximately the same temperature, the thermal conductivity values of [C16MIM]Br and [C16MIM]Cl were higher than those of [C16MMIM]Br and [C16MMIM]Cl. Additionally, the effect of methylation showed an increase in thermal conductivity with temperature. The strong and directional hydrogen bonds at C2 of the protonated ILs stimulate a dominant cation-anion interaction at this position, which might result in a tighter and stronger structure that causes reduced ion mobility, which favours the heat transfer process. The superior role of H2 as the most acidic hydrogen for hydrogen bonding with C2 might be disturbed by its faster dynamics than the hydrogen bonds at other positions of C4 and C5 (Thar et al., 2009). The strong dynamics of the hydrogen bond at C2 influence the ion pair and ion cage dynamics, which in turn affect the diffusion coefficient and transport properties of the ILs (Kohagen et al., 2011). This phenomenon might explain the decrease in thermal conductivity with an increase in temperature of common protonated ILs (Table 1), except for ILs with strongly coordinated anion such as Cl. In methylated ILs, the addition of methyl at the C2 position increases the dispersion force that shields cation-anion interactions at this position (Fumino et al., 2014). With strong hydrogen bonds formed by C4,5-H (Noack et al., 2010) and high transition barriers for ion-pair conformations (Izgorodina et al., 2011), the high viscosity (Table 3) might be responsible for the increase in thermal conductivity with temperature for [C16MMIM]Br, [C16MMIM]Cl, and [C4MMIM]NTf2. The increase in the thermal conductivity with an increase in viscosity is in good agreement with the model proposed by Mohanty (1951), which combines the viscosity theory of a liquid from the solid-state perspective (Andrade, 1934) and the liquid’s thermal conductivity (Osida, 1939). Hence, the ratio between thermal conductivity and viscosity is a constant depending on the molecular weight of the liquid (Prado et al., 2022).

Considering the smaller radius (Sanchora et al., 2019; Vieira et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2006) and stronger ligand field (Margaryan, 1999) of the Cl anion than those of the Br anion, one might expect the hydrogen bond of C2-H-Cl to be stronger than that of C2-H-Br. This is confirmed by the atomic distance calculation, which shows a smaller H-Cl distance than that of H-Br for protonated ILs (Dong et al., 2016). Additionally, a comparison between [C4MIM]Cl, [C4MIM]NTf2, and [C4MIM]BF4 shows that the symmetry and charge density of the anion play an important role in forming a regular network (Hunt et al., 2007; Hunt and Gould, 2006). Neutron diffraction studies indicate that Cl anion prefer to remain in a ring around the H atom, with a decreased affinity for lying above and below the centre of the imidazolium because of its small size and stronger hydrogen bond (Hardacre et al., 2003). This is supported by the relationship between the molecular structures and viscosity, which revealed a strong correlation between the two parameters. In particular, the local aggregation of anion at certain cation sites prevents the movement of ion pairs, which increases the viscosities of the ILs (Jiang et al., 2019). Thus, ILs with strongly coordinated Cl anion are expected to form highly connected liquids with relatively strong interactions compared to those of ILs with weakly coordinated Br anion (Izgorodina et al., 2011). As shown in Fig. 5 (a) and 6 (a), the thermal conductivity of [C16MIM]Br exhibited a trend similar to that of [C4MIM]NTf2 (Ge et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2012). The difference in the local structure and coordination strength explains the higher thermal conductivity of [C16MIM]Cl compared with those of [C16MIM]Br, and the different trends in the thermal conductivity of the two molecules. The thermal conductivity of [C16MIM]Cl increases whereas the thermal conductivity of [C16MIM]Br and [C4MIM]NTf2 decreases with an increase in temperature.

Understanding the correlation between the structure and physicochemical properties of ILs is important for their applications. The effects of the structure are mainly influenced by the anion type, which determines the thermal stability of the ILs (Cao and Mu, 2014; Fadeeva et al., 2020). In addition, the thermal stability of ILs increases with a decrease in chain lengths (Cao and Mu, 2014; Koutsoukos et al., 2022) and after the replacement of C2-H with a methyl group (Huddleston et al., 2001; Koutsoukos et al., 2022; Muhammad, 2016; Noack et al., 2010). The molecular interaction between cation and anion as the main constituent components of ILs are described by a subtle balance of Coulomb forces, hydrogen bonds, and dispersion forces (Fumino et al., 2014; Izgorodina et al., 2014). The results presented in this study demonstrate the relationship between the structural modification of ILs through methylation and the anion type, on the physicochemical and thermal properties, including the thermal conductivity of the long alkyl chain of imidazolium-based ILs. However, these findings do not directly explain the trend of thermal conductivity with temperature. Therefore, advanced computational studies are required because liquid thermal conductivity generally involves complex phenomena. In addition, further experimental studies are needed to investigate the role of anion coordination strength with those of thermophysical parameters, including the thermal conductivity of hydrated ILs. This is because the simulation study showed that the Coulombic network of the ILs with Cl anion is more disturbed by water than that of ILs with BF4 anion (Macchieraldo et al., 2018).

4 Conclusion

The effect of methylation and anion type on physicochemical and thermal properties (decomposition temperature, melting temperature, enthalpy, and thermal conductivity) was characterised for long alkyl chains of imidazolium-based ILs of [C16MIM]X and [C16MMIM]X, for X = Br and Cl. Chemical structure analysis was based on the transmittance of FT-IR spectra. In the fingerprint region (500–1750 cm−1), methylation caused a blue shift from 1574 cm−1 (in protonated ILs) to 1587 cm−1 due to CH2(N) and CH3(N) CN stretching and produced a new peak at a wavelength of 1042 cm−1 associated with the CH2(N) and CH3(N)CN stretching bond. In the functional group region (1750–4000 cm−1), methylation caused a frequency shift at approximately 3468 cm−1 which is related to the change in vibrational type from C2-H-X to C2-methyl-X for both Br and Cl anions due to formation of a hydrogen bond and charge redistribution along the non-hydrogen-bonded C-H bonds.

Methylation resulted in a higher thermal stability, as indicated by the increase in Td, an increase in Tm, and a decrease in Hm, resulting in a reduction in entropy. This reduction revealed that the methylation altered the electron density distribution and consequently changed the positions of the interionic interactions, resulting in a more stable and packed molecular network with increased Coulomb interactions and decreased van der Waals interactions. The variation of Td with the change in anion was attributed to the smaller pKa value of Br-based acids than that of the Cl-based acids according to the Brønsted acid model. The variation in Tm and Hm of protonated ILs was attributed to the stronger hydrogen bond of ILs containing Cl− owing to the smaller ionic radius and larger electronegativity of Cl− as compared to Br−.

Thermal conductivity measurements show some important characteristics: i) an increase in the thermal conductivity of methylated ILs with temperature, and ii) the value and temperature dependence of thermal conductivity strongly depend on the anion. The strong hydrogen bond at C2 of the protonated ILs limits anion mobility and favours the heat conduction process. However, the strong dynamics of the hydrogen bond at C2 disturb the ion-pair interaction, resulting in a decrease in thermal conductivity with increasing temperature of common protonated ILs, including [C16MIM]Br and [C4MIM]NTf2. However, in methylated ILs, the loss of hydrogen bonding at the C2 position of the imidazolium ring increases the dispersion force. In addition to the strong hydrogen bonds formed by C4,5-H, high viscosity might be directly responsible for the increase in thermal conductivity with the increase in temperature in [C16MMIM]Br, [C16MMIM]Cl, and [C4MMIM]NTf2. In addition to the liquid crystalline phase, stronger hydrogen bonding and a higher viscosity in the more compact molecular structure of ILs with Cl anion explained the higher thermal conductivity of [C16MIM]Cl than that of [C16MIM]Br and the increase in its thermal conductivity with temperature. The results of the present study should be confirmed using advanced computational methods by considering the fundamental interactions occurring in the IL.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by PMDSU Batch IV from Kementerian Riset Teknologi Dan Pendidikan Tinggi Republik Indonesia. The authors acknowledge the facilities, scientific and technical support from Advanced Characterization Laboratories Bandung and Advanced Characterization Laboratories Cibinong – Integrated Laboratory of Bioproduct, National Research and Innovation Agency through E- Layanan Sains, Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

References

- Andrade, E.N. da C., 1934. XLI. A theory of the viscosity of liquids.—Part I . The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 17, 497–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/14786443409462409.

- Temperature-dependent thermal conductivity measurement system for various heat transfer fluids. Instru. Mesure Metrol.. 2021;20:195-202.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of anion and alkyl chain length of cation on the thermophysical properties of imidazolium-based ionic liquid. Mater. Today:. Proc.. 2020;7–10

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of nucleators on the thermodynamic properties of seasonal energy storage materials based on ionic liquids. Energy Fuels. 2011;25:1811-1816.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liquid-liquid equilibria for azeotropic mixture of methyl tert-butyl ether and methanol with ionic liquids at different temperatures. J. Chem. Thermodyn.. 2019;132:76-82.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Highly discriminating distance-based topological index. Chem. Phys. Lett.. 1982;89:399-404.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hydrophobic, highly conductive ambient-temperature molten salts. Inorg. Chem.. 1996;35:1168-1178.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Small-angle x-ray scattering studies of liquid crystalline 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium salts. Chem. Mater.. 2002;14:629-635.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive investigation on the thermal stability of 66 ionic liquids by thermogravimetric analysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2014;53:8651-8664.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Solvent properties of the 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate ionic liquid. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.. 2003;375:191-199.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermal conductivity of ionic liquids at atmospheric pressure: database, analysis, and prediction using a topological index method. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2014;53:7224-7232.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Free volume model for the unexpected effect of C2-methylation on the properties of imidazolium ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2014;118:2712-2718.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coates, J., 2006. Interpretation of Infrared Spectra, A Practical Approach, in: Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470027318.a5606.

- Ludwig's applied process design for chemical and petrochemical plants (4nd ed;). Houston: Gulf Professional Publishing:; 2007. p. :103-132.

- State-of-the-art ionic liquid & ionanofluids incorporated with advanced nanomaterials for solar energy applications. J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;336:116563

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermal properties of ionic liquids and IoNanoFluids of imidazolium and pyrrolidinium liquids. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2010;55:653-661.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 1-Octanol/water partition coefficients of 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride+. Chem.—Eur. J.. 2003;9:3033-3041.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- solubility of 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorophosphate in hydrocarbons. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2003;48:451-456.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the hydrogen bonds in ionic liquids and their roles in properties and reactions. Chem. Commun.. 2016;52:6744-6764.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of methylation at the 2 position of the cation ring on phase behaviors and conformational structures of imidazolium-based ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:9201-9208.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Physico-chemical characterization of alkyl-imidazolium protic ionic liquids. J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;297:111305

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Flammability, thermal stability, and phase change characteristics of several trialkylimidazolium salts. Green Chem.. 2003;5:724-727.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermal conductivity of ionic liquids and ionanofluids and their feasibility as heat transfer fluids. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2018;57:6516-6529.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermophysical properties of imidazolium-based ionic liquids. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2004;49:954-964.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermal conductivity of ionic liquids: Measurement and prediction. Int. J. Thermophys.. 2010;31:2059-2077.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Probing molecular interaction in ionic liquids by low frequency spectroscopy: Coulomb energy, hydrogen bonding and dispersion forces. PCCP. 2014;16:21903-21929.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermal conductivities of ionic liquids over the temperature range from 293 K to 353 K. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2007;52:1819-1823.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad, B., Kiefer, J., Brahim, H., Belarbi, E. habib, Villemin, D., Bresson, S., Abbas, O., Rahmouni, M., Paolone, A., Palumbo, O., 2018. Effects of C(2) methylation on thermal behavior and interionic interactions in imidazolium-based ionic liquids with highly symmetric anions. Applied Sciences 8, 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/app8071043.

- Structure of molten 1,3-dimethylimidazolium chloride using neutron diffraction. J. Chem. Phys.. 2003;118:273-278.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural determination of paraffin boiling points. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 1947;69:17-20.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The theory of the transient hot-wire method for measuring thermal conductivity. Phys. B+C. 1976;82:392-408.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, W., Henderson, W.A., Young, V.G., Fox, D.M., Long, C. de; Trulove, P.C. , 2006. Alkyl vs . alkoxy chains on ionic liquid cations. Chemical Communications, 3708–3710. https://doi.org/10.1039/b606381k.

- Topological Index. a newly proposed quantity characterizing the topological nature of structural isomers of saturated hydrocarbons. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn.. 1971;44:2332-2339.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization and comparison of hydrophilic and hydrophobic room temperature ionic liquids incorporating the imidazolium cation. Green Context 2001

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Why does a reduction in hydrogen bonding lead to an increase in viscosity for the 1-Butyl-2,3-dimethyl-imidazolium-based ionic liquids? J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:4844-4853.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The structure of imidazolium-based ionic liquids : insights from ion-pair interactions. Aust. J. Chem.. 2007;60:9-14.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural characterization of the 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ion pair using ab initio methods. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2006;110:2269-2282.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Intermolecular dynamics of room-temperature ionic liquids: Femtosecond optical Kerr effect measurements on 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium bis((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)imides. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2002;106:7579-7585.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Importance of dispersion forces for prediction of thermodynamic and transport properties of some common ionic liquids. PCCP. 2014;16:7209-7221.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the effect of the C2 proton in promoting low viscosities and high conductivities in imidazolium-based ionic liquids: part I. weakly coordinating anions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:14688-14697.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Density and viscosity of several pure and water-saturated ionic liquids. Green Chem.. 2006;8:172-180.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Insight into the relationship between viscosity and hydrogen bond of a series of imidazolium ionic liquids: a molecular dynamics and density functional theory study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2019;58:18848-18854.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Physical properties of ionic liquids consisting of the 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium cation with various anions and the bis (trifluoromethylsulfonyl) imide anion with various cations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:81-92.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ionic liquids as electrolytes for energy storage applications – a modelling perspective. Energy Storage Mater.. 2020;25:827-835.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kabo, G.J., Blokhin, A. v, Paulechka, Y.U., Kabo, A.G., Shymanovich, M.P., Magee, J.W., 2004. Thermodynamic Properties of 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium Hexafluorophosphate in the Condensed State 453–461.

- Diverse applications of ionic liquids: a comprehensive review. J. Mol. Liq.. 2022;351:118556

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structure, hydrogen bond dynamics and phase transition in a model ionic liquid electrolyte. PCCP. 2022;24:6064-6071.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- How hydrogen bonds influence the mobility of imidazolium-based ionic liquids. A combined theoretical and experimental study of 1-n-butyl-3- methylimidazolium bromide. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2011;115:15280-15288.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of the cation structure on the properties of homobaric imidazolium ionic liquids. PCCP. 2022;24:6453-6468.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Principles of heat transfer (7nd ed). Stanford: Cengage Learning; 2011.

- Formation and thermal stabilities research of ionic liquids/α-ZrP antibacterial materials. J. Inorg. Mater. 2011:1193-1198.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Transient phase-induced nucleation in ionic liquid crystals and size-frustrated thickening. Chem. Mater.. 2005;17:250-257.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermal and transport properties of six ionic liquids : an experimental and molecular dynamics study. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2012;51:7242-7254.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hydrophilic ionic liquid mixtures of weakly and strongly coordinating anions with and without water. ACS Omega. 2018;3:8567-8582.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phase transitions in higher-melting imidazolium-based ionic liquids : experiments and advanced data analysis. J. Mol. Liq.. 2019;292:111222

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A.A. Margaryan, 1999, Ligands and Modifiers in Vitreous Materials, Ligands and Modifiers in Vitreous Materials, Chapter 3. https://doi.org/10.1142/4124

- Bimolecular rate constants for diffusion in ionic liquids. Chem. Commun. 2002:1880-1881.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and physicochemical properties of ionic liquids : 1-alkenyl-2,3-dimethylimidazolium tetrafluoroborates. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc.. 2007;28:1562-1566.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Overview of ionic liquids as candidates for new heat transfer fluids. Int. J. Thermophys.. 2020;41

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A relationship between heat conductivity and viscosity of liquids. Nature. 1951;168:42.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermal and kinetic analysis of pure and contaminated ionic liquid: 1-butyl-2.3-dimethylimidazolium chloride (BDMIMCl) Polish J. Chem. Technol.. 2016;18:122-125.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The fluid-mosaic model, homeoviscous adaptation, and ionic liquids: dramatic lowering of the melting point by side-chain unsaturation. Angew. Chem. – Int. Ed.. 2010;49:2755-2758.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal structure of 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium iodide. Chem. Lett.. 2006;35:1400-1401.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Physical and electrochemical properties of 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate for electrolyte. J. Fluorine Chem.. 2003;120:135-141.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Melting and freezing behaviors of prototype ionic liquids, 1-Butyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide and its chloride, studied by using a nano-watt differential scanning. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:4894-4900.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The role of the C2 position in interionic interactions of imidazolium based ionic liquids: A vibrational and NMR spectroscopic study. PCCP. 2010;12:14153-14161.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Temperature dependence of viscosity for room temperature ionic liquids. J. Electroanal. Chem.. 2004;568:167-181.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ionic liquid-based nanofluids (ionanofluids) for thermal applications: an experimental thermophysical characterization. Pure Appl. Chem.. 2019;91:1309-1340.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of anion on physical and electronic property of imidazolium ionic liquids: role of weak interactions. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5:2805-2809.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vibrational Spectroscopy of Ionic Liquids. Chem. Rev.. 2017;117:7053-7112.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Y.U. Paulechka, 2007, Thermodynamic properties of 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium bromide ionic liquids 39, 158–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jct.2006.05.008

- A new relationship on transport properties of nanofluids. evidence with novel magnesium oxide based n-tetradecane nanodispersions. Powder Technol.. 2022;397:117082

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Imidazolium-based protic ionic liquids with perfluorinated anions : influence of chemical structure on thermal properties. J. Mol. Liq.. 2022;345:117782

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular simulations of anion and temperature dependence on structure and dynamics of 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015;119:14800-14806.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- On characterization of molecular branching. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 1975;97:6609-6615.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ionic liquids: functionalization and absorption of SO2. Green Energy Environ.. 2018;3:179-190.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermodynamic, structural and dynamic properties of ionic liquids [C4mim][CF3COO], [C4mim][Br] in the condensed phase, using molecular simulations. RSC Adv.. 2019;9:13677-13695.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of size and electronegativity of halide anions on hydrogen bonds and properties of 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium-based ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2019;123:4948-4963.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Viscosity and density of 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium ionic liquids. ACS Symp. Ser.. 2002;819:34-49.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Solid-liquid equilibrium and heat capacity trend in the alkylimidazolium PF6 series. J. Mol. Liq.. 2017;248:678-687.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P., Park, S.D., Park, K.T., Nam, S.C., Jeong, S.K., Yoon, Y. il, Baek, I.H., 2012. Solubility of carbon dioxide in amine-functionalized ionic liquids: Role of the anions. Chemical Engineering Journal 193–194, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2012.04.015.

- Ionic liquids synthesis and applications: an overview. J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;297:112038

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MOLView: A program for analyzing and displaying atomic structures on the Macintosh personal computer. J. Mol. Graph. 1995

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Efficient biomass pretreatment using ionic liquids derived from lignin and hemicellulose. Appl. Phys. Sci.. 2014;111:3587-3595.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Free radical polymerization of n -butyl methacrylate in ionic liquids. Macromolecules. 2006;39:923-930.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Unexpected hydrogen bond dynamics in imidazolium-based ionic liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:15129-15132.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- How ionic are room-temperature ionic liquids? An indicator of the physicochemical properties. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:19593-19600.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Viscosity and thermal conductivity of 1-hexyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate and 1-Octyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate at pressures up to 20 MPa. Int. J. Thermophys.. 2012;33:959-969.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermal conductivities of [bmim][PF6], [hmim][PF 6], and [omim][PF 6] from 294 to 335 K at pressures up to 20 MPa. Int. J. Thermophys.. 2007;28:1147-1160.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Measurements of thermal conductivity of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate at high pressure. Heat Transfer Asian Res.. 2007;36:361-372.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermodynamic properties of imidazolium-based ionic liquids : densities, heat capacities, and enthalpies of fusion of [bmim][PF6] and [bmim][NTf2] J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2006;51:1856-1859.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Acidity of strong acids in water and dimethyl sulfoxide. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2016;120:3663-3669.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A review of ionic liquids: applications towards catalytic organic transformations. J. Mol. Liq.. 2017;227:44.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of large anions in thermal properties and cation-anion interaction strength of dicationic ionic liquids. J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;298:112077

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Physicochemical characterization of ionic liquid binary mixtures containing 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium as the common cation †. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2019;64:4891-4903.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ionic liquids as heat transfer fluids – an assessment using industrial exchanger geometries. Appl. Therm. Eng.. 2017;111:1581-1587.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gold-ionic liquid nanofluids with preferably tribological properties and thermal conductivity. Nanoscale Res. Lett.. 2011;6:2-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A review on molten-salt-based and ionic-liquid-based nanofluids for medium-to-high temperature heat transfer. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.. 2018;136:1037-1051.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Long-alkyl-chain-derivatized imidazolium salts and ionic liquid crystals with tailor-made properties. RSC Adv.. 2014;4:12476-12481.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liquid-liquid extraction of butanol from heptane + butanol mixture by ionic liquids. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2017;62:4273-4278.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of alkyl chain length and anion size on thermal and structural properties for 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium hexafluorocomplex salts (C xMImAF 6, x = 14, 16 and 18; A = P, As, Sb, Nb and Ta) Dalton Trans.. 2012;41:3494-3502.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of alkyl chain length on properties of 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium fluorohydrogenate ionic liquid crystals. Chem.—Eur. J.. 2010;16:12970-12976.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heat capacity and glass transition of an ionic liquid 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride. Chem. Phys. Lett.. 2006;423:371-375.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Odd-even glass transition temperatures in network-forming ionic glass homologue. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2014;136:1268-1271.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Physical properties of ionic liquids: database and evaluation. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 2006;35:1475-1517.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liquid crystalline phases self-organized from a surfactant-like ionic liquid C16mimCl in ethylammonium nitrate. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:2024-2030.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of room temperature ionic liquids containing the nitrile functionality. Inorg. Chem.. 2004;43:2197-2205.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermodynamical properties of phase change materials based on ionic liquids. Chem. Eng. J.. 2009;147:58-62.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Computer-aided screening of ionic liquids as entrainers for separating methyl acetate and methanol via extractive distillation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2018;57:9656-9664.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

![Temperature-dependent thermal conductivity of: (a) [C4MIM]NTf2 (solid blue circle referred to (Ge et al., 2007); solid black square referred to (Liu et al., 2012)) and (b) [C4MMIM]NTf2 (Liu et al., 2012). The dash red lines represent the result of fitting the data using Eq. (3) and Eq. (4).](/content/184/2022/15/8/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103963-fig7.png)