Translate this page into:

Volatile constituents of Amomum argyrophyllum Ridl. and Amomum dealbatum Roxb. and their antioxidant, tyrosinase inhibitory and cytotoxic activities

⁎Corresponding author at: Center of Chemical Innovation for Sustainability (CIS) and School of Science, and Medicinal Plant Innovation Center of Mae Fah Luang University, Mae Fah Luang University, Thailand. surat.lap@mfu.ac.th (Surat Laphookhieo)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The volatile components from fresh rhizomes and leaves of Amomum argyrophyllum Ridl. and Amomum dealbatum Roxb. were performed using HS-SPME and charac-terized by GC–MS. A total of 49, 47, 49, and 34 compounds were identified from the rhizomes and leaves of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum, respectively. The major components were β-pinene, α-pinene, and o-cymene. The rhizome extracts exhibited total phenolic content of 2.9 ± 0.5 and 2.1 ± 0.6 mg gallic acid equivalents. The IC50 values of DPPH and ABTS were 179.8 ± 3.9 µg/mL, 392.9 ± 2.6 µg/mL, 120.3 ± 2.5 µg/mL, and 328.6 ± 3.3 µg/mL, respectively. The FRAP values were 76.5 ± 7.8 and 84.9 ± 4.4 µM ascorbic acid equivalents. The extracts showed weak antibacterial activity and tyrosinase inhibitory activity of 69.0 ± 3.6 and 53.7 ± 7.4 mg kojic acid equivalents. The cytotoxicity effect was assessed with the MTT assay at 200 µg/mL. The extracts showed no toxicity. In addition, the anti-inflammatory properties of extracts were evaluated, and showed potential to inhibit nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activity.

Keywords

Amomum argryllophitum

Amomum delbatum

Chemical composition

Antioxidant activity

Tyrosinase inhibitory activity

Anti-inflammatory

1 Introduction

Zingiberaceae is one of the essential oil plant families. The genus Amomum belongs to the family Zingiberaceae, with about 180 identified species (Lamxay and Newman, 2012). About 20 species are present in Thailand (Chate and Nuntawong, 2015). Many species of Amomum are used as folk medicine, spice, and a vegetable (Sabulal et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2010). Thai traditional medicine has used some Amomum to treat malaria, stomach disorders, flatulence, and as blood circulation tonic (Chaveerach et al., 2008; Singtothong et al., 2013; Maneenoon et al., 2015). The essential oils of some Amomum have been widely studied for chemical composition, antibacterial, anti-oxidant activities, and also used as antimicrobial agents (Martin et al., 2000; Wannissorn et al., 2005; Sabulal et al., 2006; Bakkali et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008; Kaewsri et al., 2009; Dai et al., 2016; Thinh et al., 2021). Moreover, an alcohol extract of A. subulatum has been reported to contain analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities (Gautam et al., 2016).

Monoterpene, oxygenated monoterpene, sesquiterpenoids, and diarylheptanoids compounds were reported in some Amomum essential oils (Gurudutt et al., 1996; Rout et al., 2003; Sabulal et al., 2006). The chemical composition including, β-pinene, elemol, and α-cadinol were identified as major constituents of the essential oils of A. cannicarpum (Sabulal et al., 2006). In addition, diterpenes, steroid, sesquiterpene and lactone were reported from the rhizome essential oils of A. uliginosum (Chate and Nuntawong, 2015). Recently, the chemical composition of essential oils from leaves, roots, stems, and fruits of A. xanthioides were identified as 38, 43, 28, and 22 compounds, with bornyl acetate (37.21 %), β-elemene (31.71 %), spathoulenol (26.89 %), terpinene-4-ol (10.77 %), and δ-cadinene (10.69 %) as main components, respectively (Thinh et al., 2021). The essential oils from dried fruits of A. tsao-ko consisted mainly of 1,8-cineole (45.24 %). Cytotoxic activities to HepG2, Hela, Bel-7402, SGC-7901 and PC-3 cell lines were investigated by MTT assay. The results showed lowest IC50 value of 31.80 ± 1.18 µg/mL to HepG2 carcinoma cell lines. However, the essential oil exhibited very weak antioxidant activity by DPPH, thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and FRAP assays (Yang et al., 2009). The antimicrobial activity of A. rubidum rhizome essential oils were established by microdilution broth susceptibility assay. The essential oils showed stronger inhibitory effect on Aspergillus niger and Fusarium oxysporum with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 50 µg/mL (Huong et al., 2019). In addition, the essential oils of A. biflorum displayed camphor (17.6 %), α-bisabolol (16.0 %), and camphene (8.2 %) as major components. The essential oils were significantly active against S. aureus with IC50 value of 15.3 ± 0.3 µg/mL and MIC of 30 µg/mL (Singtothong et al., 2013).

Most recently, essential oils extracted from Amomum species showed various pharmacological activities, such as antioxidant, antimicrobial, and cytotoxicity. Nevertheless, some species have been poorly studied. According to the SciFinder Scholar database (Chemical Abstracts Service, Columbus, OH, USA), no essential oil composition investigations or biological activities have been reported for A. argyrophyllum. In the case of A. dealbatum, only antidiarrheal and thrombolytic effect of ethanolic extract of leaves in mice has been investigated by Islam and co-workers in 2019 (Islam et al., 2019. This information led us to investigate the essential oil composition and biological activities (tyrosinase inhibitory, anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic activities) of the EtOAc extract of the rhizomes of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum. In addition, total phenolic contents and antioxidant activities (DPPH, FRAP, and ABTS assays) were also investigated.

2 Experimental

2.1 Plant material

Fresh leaves and rhizomes of A. dealbatum (N: 20.1932°, E: 99.4856°) and A. argyrophyllum (N: 20.1927°, E: 99.4855°) were collected from the Doi Tung Development Project, Chiang Rai Province, Northern Thailand in May 2016. The plant was authenticated by Mr. Martin Van de Bult, a botanist at Doi Tung Development Project, Chiang Rai, Thailand. The voucher specimens (MFU-NPR0201 and MFU-NPR0202) were deposited at the Natural Products Research Laboratory of Mae Fah Luang University.

2.2 Chemicals

Gallic acid, l-ascorbic acid, kojic acid, C8 - C20 n-alkanes standard solution, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,2′ -azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS), 2,4,6-tris(2-pyridyl)-s-triazine (TPTZ), tyrosinase from mushroom, 3,4-dihydroxy-l-phenylalanine (l-DOPA), 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Mueller-Hinton broth was obtained from HiMedia Laboratories (Mumbai, India). Vancomycin hydrochloride was obtained from the EDQM Council of Europe (Strasbourg, France). Gentamycin sulfate and ampicillin sodium salt were obtained from Bio Basic Canada (Markham, ON, Canada). All chemicals and solvents used in this study were of analytical grade.

2.3 Headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME)

The volatile components from leaves and rhizomes of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum were performed using a headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME). The SPME fiber was coated with 50/30 μm divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethyl-siloxane (DVB/CAR/PDMS) (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA). Fresh samples (50 g) were transferred to a 250 mL glass septum bottle, then incubated in a water bath at 45 °C for 30 min. Volatile components were extracted by exposing the SPME fiber to the headspace for 30 min. For each extraction, the SPME fiber was preconditioned for 30 min at 220 °C by inserting into the injection port of GC–MS under helium atmosphere. The inlet temperature for volatile desorption was carried out at 250 °C for 5 min (Pintatum et al., 2020a).

2.4 Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis

An Agilent Technologies, Hewlett Packard model HP6890 gas chromatography with an HP model 5973 mass-selective detector (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for GC–MS analysis. HP-5 ms (5 % phenylpolymethylsiloxane) capillary column (30 m length × 0.25 mm id × 0.25 μm film thickness, Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) and helium carrier gas (99.99 % purity) with a flow rate of 1 mL/min in split mode 1:70 was used. The oven temperature was set at 60 °C and increased at a rate of 3 °C/min to 220 °C. The temperatures of injector and detector were set at 250 °C and 280 °C, respectively. The detections were as follows, mass spectra with an ionization energy of 70 eV, scan a mass of m/z 29–300, and electron multiplier voltage of 1150 V, respectively. The temperatures of ion source and quadrupole were set at 230 °C and 150 °C, respectively (Pintatum et al., 2020a). All identified components were quantified using Kovát retention indices relative to the C8–C20 n-alkanes standard and the mass spectra of individual components with the reference mass spectra via Wiley and National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) database. The volatile constituents were summarized as a percent relative peak area, as shown in Table 1. nd: not detected. Values are the mean percentage of peak areas ± standard deviation (SD), n = 3.

Compound

LRIa

LRIb.

1c

2d

3e

4f

Ident.g

α-Thujene

923

924

0.4 ± 0.0

0.2 ± 0.0

0.2 ± 0.0

0.4 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

α-Pinene

931

939

6.5 ± 0.4

4.3 ± 0.3

23.0 ± 1.4

24.7 ± 1.4

1, 2, 3

Camphene

944

946

10.8 ± 0.5

0.4 ± 0.0

0.6 ± 0.1

0.7 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

β-Pinene

978

974

16.7 ± 2.2

16.7 ± 1.4

45.2 ± 2.1

55.1 ± 2.0

1, 2, 3

Myrcene

987

990

1.3 ± 0.3

0.6 ± 0.1

1.7 ± 0.1

4.2 ± 0.3

1, 2, 3

α-Phellandrene

1002

1002

0.2 ± 0.0

nd

0.1 ± 0.0

0.2 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

δ-3-Carene

1007

1011

nd

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

0.9 ± 0.2

1, 2, 3

α-Terpinene

1013

1017

nd

nd

0.02 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

o-Cymene

1020

1026

1.1 ± 0.1

20.7 ± 1.9

0.1 ± 0.0

0.6 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

Limonene

1024

1029

9.7 ± 0.8

1.9 ± 0.2

3.5 ± 0.1

5.6 ± 0.5

1, 2, 3

(Z)-β-Ocimene

1032

1037

10.6 ± 0.5

2.0 ± 0.1

4.6 ± 0.3

0.8 ± 0.1

1, 2, 3

(E)-β-Ocimene

1043

1050

8.7 ± 0.5

2.4 ± 0.4

4.4 ± 0.3

1.2 ± 0.2

1, 2, 3

γ-Terpinene

1053

1059

0.3 ± 0.1

0.1 ± 0.0

0.05 ± 0.0

0.2 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

Fenchone

1083

1083

0.6 ± 0.1

0.2 ± 0.0

0.3 ± 0.0

0.5 ± 0.1

1, 2, 3

Linalool

1095

1096

nd

0.2 ± 0.0

0.03 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

Fenchol

1108

1118

0.3 ± 0.0

nd

0.03 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

allo-Ocimene

1124

1128

10.0 ± 0.8

1.6 ± 0.4

3.6 ± 0.4

0.5 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

(E)-Pinocarveol

1132

1135

nd

0.2 ± 0.1

nd

0.04 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

neo-allo-Ocimene

1135

1140

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

0.04 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

Camphor

1138

1141

0.2 ± 0.0

nd

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Camphene hydrate

1142

1145

0.03 ± 0.0

nd

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Borneol

1150

1155

0.2 ± 0.0

0.3 ± 0.0

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

(Z)-Pinocamphone

1167

1172

nd

nd

0.1 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

Terpinen-4-ol

1171

1174

0.1 ± 0.0

0.7 ± 0.1

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

p-Cymen-8-ol

1175

1179

nd

0.6 ± 0.1

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

4-Methyleneisophorone

1202

1216

nd

0.3 ± 0.1

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

α-Fenchyl acetate

1214

1218

8.6 ± 0.4

nd

0.6 ± 0.1

nd

1, 2, 3

Thymol methyl ether

1224

1232

0.02 ± 0.0

nd

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

β-Fenchyl acetate

1227

1229

0.6 ± 0.1

nd

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Linalool acetate

1250

1254

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Isobornyl acetate

1279

1283

2.8 ± 0.2

nd

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

Thymol

1283

1289

nd

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

neo-Isoverbanol acetate

1320

1328

nd

nd

0.03 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

δ-Elemene

1330

1335

nd

nd

0.3 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

α-Cubebene

1342

1345

0.2 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

Epizonarene

1358

–

nd

1.1 ± 0.1

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2

α-Ylangene

1363

1375

0.02 ± 0.0

nd

0.02 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

α-Copaene

1368

1376

0.2 ± 0.1

6.4 ± 1.2

2.1 ± 0.3

0.6 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

β-Cubebene

1382

1387

nd

0.2 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

0.04 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

β-Elemene

1384

1389

0.2 ± 0.0

0.7 ± 0.1

0.1 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

Sibirene

1387

1400

nd

0.2 ± 0.0

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Longifolene

1401

1407

nd

nd

0.03 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

(Z)-Caryophyllene

1411

1408

2.2 ± 0.2

9.5 ± 1.5

2.6 ± 0.3

0.6 ± 0.1

1, 2, 3

β-Copaene

1420

1430

nd

nd

0.1 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

γ-Elemene

1425

1434

0.2 ± 0.0

nd

0.1 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

α-Guaiene

1430

1437

0.7 ± 0.2

2.9 ± 0.4

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

Aromadendrene

1435

1439

1.8 ± 0.3

6.0 ± 0.4

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

6,9-Guaiadiene

1440

1442

0.4 ± 0.0

1.0 ± 0.1

0.3 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

α-Humulene

1444

1452

0.2 ± 0.0

0.7 ± 0.1

0.3 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

allo-Aromadendrene

1452

1458

nd

0.6 ± 0.0

0.6 ± 0.1

0.3 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

(E)-Cadina-1(6),4-diene

1454

1461

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Neoclovene

1466

–

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

0.3 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2

Dauca-5,8-diene

1468

1471

nd

0.5 ± 0.1

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Germacrene D

1472

1485

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

1.0 ± 0.1

0.5 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

β-Chamigrene

1475

1476

1.1 ± 0.3

nd

0.4 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

γ-Himachalene

1477

1481

nd

0.9 ± 0.3

0.3 ± 0.0

0.2 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

δ-Selinene

1484

1492

0.3 ± 0.0

1.6 ± 0.2

1.2 ± 0.2

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

(E)-β-Cuaiene

1484

1492

0.3 ± 0.0

0.3 ± 0.1

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Bicyclogermacrene

1487

1500

nd

nd

0.3 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

Isodaucene

1490

1500

0.2 ± 0.0

nd

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Pentadecane

1493

1500

nd

7.1 ± 1.0

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

α-Bulnesene

1497

1509

0.2 ± 0.0

0.6 ± 0.1

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

γ-Patchoulene

1498

1502

nd

nd

0.04 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

(E,E)-α-Farnesene

1500

1505

0.1 ± 0.0

0.5 ± 0.1

nd

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

γ-Cadinene

1505

1513

0.4 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

0.3 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

7-epi-α-Selinene

1508

1520

0.2 ± 0.1

nd

0.3 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

δ-Cadinene

1514

1522

0.2 ± 0.0

0.6 ± 0.2

0.1 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

Dendrolasin

1570

1570

nd

0.2 ± 0.0

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

(E)-Jasmolactone

1571

1578

nd

nd

nd

0.1 ± 0.0

1, 2, 3

Caryophyllene oxide

1573

1583

0.04 ± 0.0

0.2 ± 0.1

0.05 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

Carotol

1593

1594

nd

0.3 ± 0.0

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

1,10-di-epi-Cubenol

1618

1618

0.1 ± 0.0

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Valerianol

1647

1656

0.1 ± 0.0

nd

0.02 ± 0.0

nd

1, 2, 3

Mustakone

1667

1676

nd

0.3 ± 0.1

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Heptadecane

1690

1700

nd

0.6 ± 0.1

nd

nd

1, 2, 3

Number of constituents

49

47

49

34

% of constituents identified

99.5%

96.8%

99.6%

98.8%

Monoterpene hydrocarbons

75.8%

52.1%

87.7%

96.7%

Oxygenated monoterpenes

13.2%

2.1%

0.8%

0.2%

Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons

10.3%

39%

11.3%

2.8%

Oxyganated sesquiterpenes

0.2%

1.1%

0.07%

0.05%

Other compounds

0.5%

5.7%

0.1%

0.3%

2.5 Rhizome extraction

One kilogram of each sample was macerated in ethyl acetate (EtOAc), (3 × 10 L, for 3 days) at room temperature (30 °C). Removal of the solvent at 40 °C under reduced pressure to provide the EtOAc extracts of A. argyrophyllum (18.53 g) and A. dealbatum (19.05 g), respectively. The extracts were stored at 4 °C for further studies.

2.6 Total phenolic content assay

The total phenolic concentration of the EtOAc extracts was determined according to the Folin-Ciocalteu method (Dudonné et al., 2009; Berker et al., 2013). The Folin–Ciocalteu reagent was diluted 10-fold with Milli-Q water. Gallic acid was used as the standard. One mg/mL of extract in ethanol was prepared. An aliquot of 100 µL of extract was pipetted into a test tube, then added 750 µL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, mixed and allowed to stand for 5 min at room temperature. Then, 750 µL of 6 % (w/v) sodium carbonate was added to the reaction mixture. The solution stood at room temperature for 1 hr. The absorbance at 750 nm wavelength was measured using a UV–vis Genesys 30 Visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fitchburg, WI, USA). Gallic acid with a serial dilution of 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 µg/mL was used to generate a standard calibration curve. Total phenolic content in the samples was calculated and expressed as milligram gallic acid equivalents.

2.7 DPPH free radical scavenging assay

The antioxidant activity was determined using a DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) free radical scavenging assay (Liyanaarachchi et al., 2018; Pintatum et al., 2020a, 2020b). The extract was tested at serially diluted concentrations of 5, 10, 25, 50, and 100 µg/mL in methanol. DPPH methanolic solution (6 × 10-5 M, 100 µL) was incubated with 100 µL of the extract in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of the reaction solution was recorded against a blank at wavelength of 517 nm using the microplate reader (Biochrom Asys UVM 340 Microplate Reader, Biochrom, Cambridge, UK). Ascorbic acid at serially diluted concentrations (0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 8 µg/mL in methanol) was used as the positive control. The DPPH radical scavenging activity was expressed as the inhibitory concentration at 50 % (IC50), which was calculated in comparison with the standard ascorbic acid (Li et al., 2016).

2.8 ABTS radical cation scavenging assay

The ABTS radical scavenging activity of extract was determined based on the method described previously (Dudonné et al., 2009; Pintatum et al., 2020a, 2020b) with some modifications. The working solution of ABTS radical cation (ABTS•+) was prepared from the reaction of equal volumes of 7 mM of ABTS with 2.45 mM of potassium persulfate in the dark at room temperature for 16 h before use. The working solution of ABTS•+ was adjusted to the absorbance of 0.70 ± 0.02 at 734 nm with ethanol. The extract was tested at serially diluted concentrations of 50, 100, 150, 200, and 300 µg/mL in ethanol. An aliquot of 20 µL of extract was mixed with 180 µL of ABTS•+ solution and allowed to stand in the dark at room temperature for 5 min, then the absorbance of the reaction solution was measured at 734 nm using the microplate reader (Biochrom Asys UVM 340 Microplate Reader, Biochrom, Cambridge, UK). Serially diluted concentrations of ascorbic acid (1.5, 3, 6, 12, and 25 µg/mL) were used as the positive controls. The ABTS radical cation scavenging activity of extract was expressed as the inhibitory concentration at 50 % (IC50), which was calculated in comparison with the standard ascorbic acid.

2.9 Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

The ferric reducing power of the extract was determined based on the method modified version of the FRAP assay (Dudonné et al., 2009). The working FRAP reagent was prepared daily by mixing 1 vol of 10 mM TPTZ (solution in 40 mM HCl), with 1 vol of 20 mM ferric chloride solution, and 10 volumes of 300 mM acetate buffer, (pH 3.6). The FRAP reagent was warmed up to 37 °C in a water bath. Fifty microliters of extract and 150 µL of deionized water were added to 1.5 mL of FRAP reagent, and then incubated at 37 °C in a water bath for 30 min. The absorbance of the reaction solution was measured at 593 nm using a microplate reader (Biochrom Asys UVM 340 Microplate Reader, Biochrom, Cambridge, UK). Acetate buffer was used as blank. Ascorbic acid with a serial dilution of 50, 100, 200, 300, and 400 µM was used to generate a standard calibration curve. The results were expressed as µM ascorbic acid equivalents (Pintatum et al., 2020a).

2.10 Inhibition of tyrosinase assay

The mushroom tyrosinase inhibition activity of the extract was determined using the method described previously (Gomółka et al., 2021; Li et al., 2019; Pintatum et al., 2020a). The extract was dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 10 mg/mL. An aliquot of 40 µL of extract was mixed with 80 µL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8), and 40 µL of tyrosinase from mushroom, enzyme commission number 1.14.18.1 (48 units/mL). Following the addition of 40 µL of l-DOPA (2.5 mM), and then allowed to stand at room temperature for 30 min. the absorbance of the reaction solution was measured at 490 nm using the microplate reader (Biochrom Asys UVM 340 Microplate Reader, Biochrom, Cambridge, UK). Each sample was accompanied by a blank sample containing all of the components without l-DOPA. Kojic acid was used as a positive control.

2.11 Antibacterial assay

Four Gram-positive bacteria, Bacillus cereus TISTR 687, Staphylococcus epidermidis TISTR 2141, Bacillus subtilis TISTR 1248, and Staphylococcus aureus TISTR 746, and four Gram-negative bacteria, Salmonella typhimurium TISTR 1470, Pseudomonas aeruginosa TISTR 1287, Escherichia coli TISTR 527, and Serratia marcescens TISTR 1354, were obtained from the Microbiological Resources Centre of the Thailand Institute of Scientific and Technological Research. A broth microdilution method was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) (Pintatum et al., 2020a; Singtothong et al., 2013; Wikaningtyas and Sukandar, 2016; Yang et al., 2008). The extract was diluted with DMSO, and then loaded in Mueller-Hinton broth microdilution with serially dilution (twofold). One hundred microliter of microbial culture an approximate of 1.0 × 106 CFU/mL was added into 96-well microtiter plates. The last row was containing only the extract without microorganisms, was used as a negative control. The broth cultures of each strain were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The MIC values were determined as the lowest concentration of the extract that completely inhibits the growth of microorganisms. Vancomycin, gentamycin, and ampicillin were used as the positive controls (Table 2). GAE: gallic acid equivalence; AAE: ascorbic acid equivalence; KAE: kojic acid equivalence; DPPH: 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; ABTS: 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt; FRAP: ferric ion reducing antioxidant power. Values are the mean ± SD, n = 3.

Sample

Total Phenolic Content

(mg GAE)

Antioxidant (IC50, µg/mL)

FRAP

(µM AAE)

Tyrosinase Inhibitory Activity (mg KAE)

DPPH

ABTS

A. argyrophyllum

2.9 ± 0.5

179.8 ± 3.9

392.9 ± 2.6

76.5 ± 7.8

69.0 ± 3.6

A. dealbatum

2.1 ± 0.6

120.3 ± 2.5

328.6 ± 3.3

84.9 ± 4.4

53.7 ± 7.4

Ascorbic acid

–

1.6 ± 0.8

5.2 ± 0.8

–

–

2.12 MTT assay

The cytotoxicity against the human keratinocyte cells (HaCaT) was determined using the MTT assay. Cells were grown in the Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium, supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum, 2 % of sodium bicarbonate (7.5 % solution), 1 % of sodium pyruvate (100 mM) and 1 % of penicillin–streptomycin (10,000 Units/mL). The cells were incubated in a humidified 37 °C, 5 % CO2 incubator, until reaching a subconfluent (approximately 80 %). The HaCaT cells were plated out in 96-well plates containing 100 µL of growth medium with a cell concentration of 2 × 104 cells/well and incubated for 24 h in an incubator. The cells were treated with increasing concentrations of extracts (12.5–200 µg/mL) for 24 h at 37 °C in 5 % CO2, after which 10 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added and incubated the cells for another 4 h. An aliquot 90 µL of 10 % SDS–0.01 M HCl was added in order to solubilize the formazan product. The absorbance was measured at 595 nm after 24 h using a microplate reader (Envision Plate Reader, Perkin Elmer, USA). Withaferin A was used as positive control (Abe et al., 2018; Pintatum et al., 2020b; Septisetyani et al., 2014; Zanette et al., 2011).

2.13 Luciferase assay

The HaCaT cells stably expressing p(NFκB)350-luc was used for this assay. The cells were plated at a density of 105 cells/well in 24-well plates for 24 h recovery period. To determine NFκB dependent transcription, the cells were preincubated for 2 h with a dose range of extract, followed by stimulation with TNFα (2 ng/mL) for 6 h at 37 °C. Then, the cells were lysed in 1 X lysis buffer (25 mM Tris‐phosphate (pH 7.8), 2 mM DTT, 2 mM CDTA, 10 % glycerol, and 1 % Triton X‐100). Luciferase activity was measured by the instructions of the “luciferase assay kit” (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), following 25 μL of lysates were placed in opaque 96 well plates, and then added 50 µL of luciferase substrate (1 mM luciferin or luciferin salt, 3 mM ATP, and 15 mM MgSO4 in 30 mM HEPES buffer, pH 7.8). Bioluminescence was measured by using the Envision multilabel reader (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Withaferin A was used as positive control (Cavin et al., 2007; Bremner et al., 2009; Zanette et al., 2011).

2.14 Statistical analysis

All values given were performed in triplicate and expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD) using Microsoft Excel. The statistical analyses included the Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), the hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA; Ward’s method), and the Principal Components Analysis (PCA) were performed with SPSS version 23.0 package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Significant differences are reported as p-value < 0.05.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Volatile oils composition

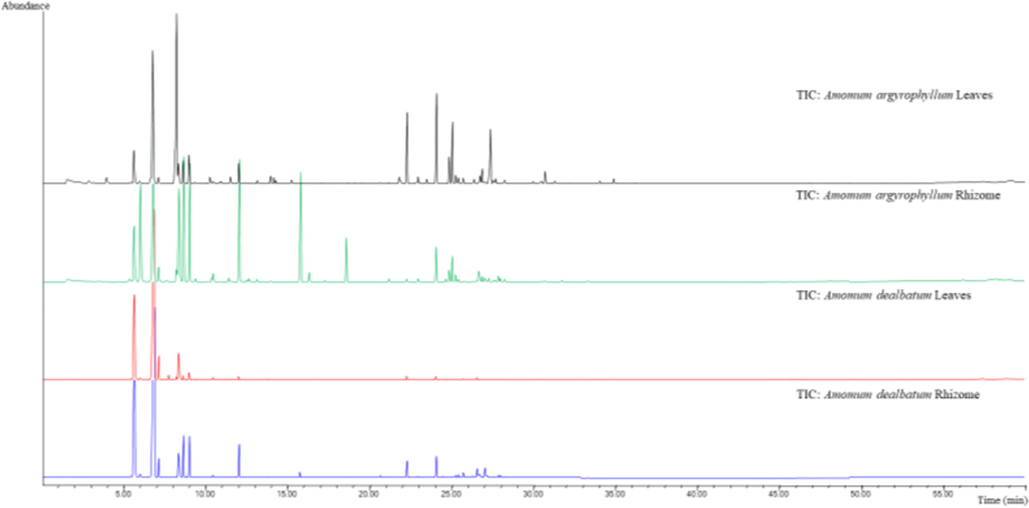

HS-SPME is simple and useful to analyse the volatiles in fragrant plants (Yang et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2012). HS-SPME-GC/MS on HP-5MS column allowed the identification of 49, 47, 49, and 34 components, comprising 99.5 %, 96.8 %, 99.6 %, and 98.8 % of the total peak areas from rhizomes and leaves of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum (Fig. 1), respectively. The chemical compositions of leaves and rhizomes volatiles are shown in (Table 1). The volatiles were dominated by 75.8 %, 52.1 %, 87.7 %, and 96.7 % of monoterpenes, followed by 13.2 %, 2.1 %, 0.8 %, and 0.2 % of oxygenated monoterpenes, 10.3 %, 39.0 %, 11.3 %, and 2.8 % of sesquiterpenes, and 0.2 %, 1.1 %, 0.07 %, and 0.05 % of oxygenated sesquiterpenes, respectively. The major components of leaves and rhizomes of A. argyrophyllum were identified as camphene (0.4 % ± 0.03 %, 10.8 % ± 0.5 %), β-pinene (16.7 % ± 1.4 %, 16.7 % ± 2.2 %), o-cymene (20.7 % ± 1.9 %, 1.1 % ± 0.1 %), limonene (1.9 % ± 0.2 %, 9.7 % ± 0.8 %), (Z)-β-ocimene (2.0 % ± 0.1 %, 10.6 % ± 0.5 %), and (E)-β-ocimene (2.4 % ± 0.4 %, 8.7 % ± 0.5 %). Whereas, the main constituents of A. dealbatum were β-pinene (45.2 % ± 2.1 %, 55.1 % ± 2.0 %), α-pinene (23.0 % ± 1.4 %, 24.7 % ± 1.4 %), limonene (3.5 % ± 0.1 %, 5.6 % ± 0.5 %), (Z)-β-ocimene (4.6 % ± 0.3 %, 0.8 % ± 0.1 %), and (E)-β-ocimene (4.4 % ± 0.3 %, 1.2 % ± 0.2 %), respectively. The other constituents identified in the volatile are compiled in Table 1.

HS-SPME chromatogram of fresh rhizomes and leaves from Amomum argyrophyllum and Amomum dealbatum.

Most of these compounds have already been reported by previous studies in different Amomum species (Ao et al., 2019; Edris, 2007; Kurup et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2008). In comparison with the previous studies, 1,8-cineole (61.3 %), α-terpineol (7.9 %), α-pinene (3.8 %), β-pinene (8.9 %), and allo-aromadendrene (3.2 %) were reported as the main volatile components in A. subulatum (Gurudutt, 1996). In addition, allo-aromadendrene (16.2 %), β-pinene (8.7 %), and (E)-caryophyllene (8.5 %) were reported as major component in the rhizome oil of A. agastyamalayanum, and santolina triene (42.2 %), and α-pinene (17.1 %) were the major constituents in rhizome oil of A. newmanii, respectively (Kurup et al., 2018). Moreover, the main constituents of the essential oil from leaves and root barks of A. villosum were as β-pinene (56.6 %, 34.7 %) and α-pinene (22.0 %, 11.6 %), respectively (Dai et al., 2016). Finally, the major constituents in the leaves of A. maximum were β-pinene (40.8 %), α-pinene (9.7 %), β-elemene (10.9 %) and β-caryophyllene (8.3 %), whereas β-pinene (28.0 %), α-pinene (15.0 %) and β-phellandrene (11.6 %) were the main constituents of the root (Huong et al., 2019). The leaves oil of A. muricarpum presented major constituents as α-pinene (48.4 %), β-pinene (25.9 %) and limonene (7.4 %), while α-pinene (54.7 %), β-pinene (14.3 %) and β-phellandrene (8.3 %) were the major in the roots, respectively (Huong et al., 2019). The results of volatile components in this study had partial agreement with the previous reports. The present results represent the first identification of the volatile constituents of rhizomes and leaves of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum.

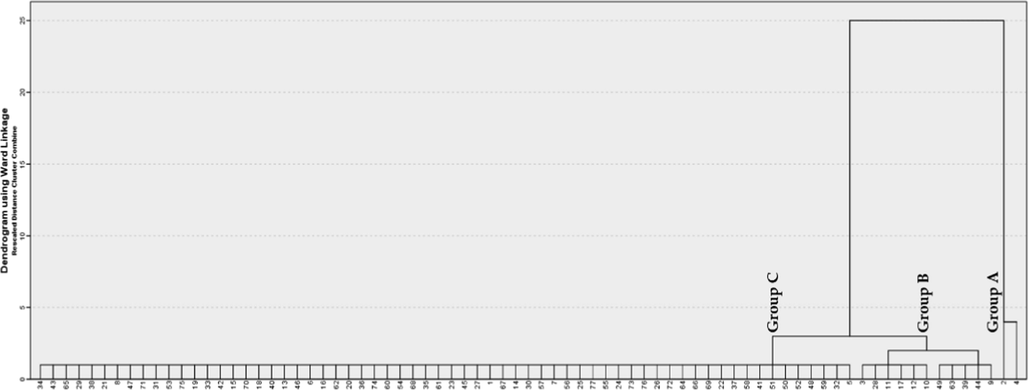

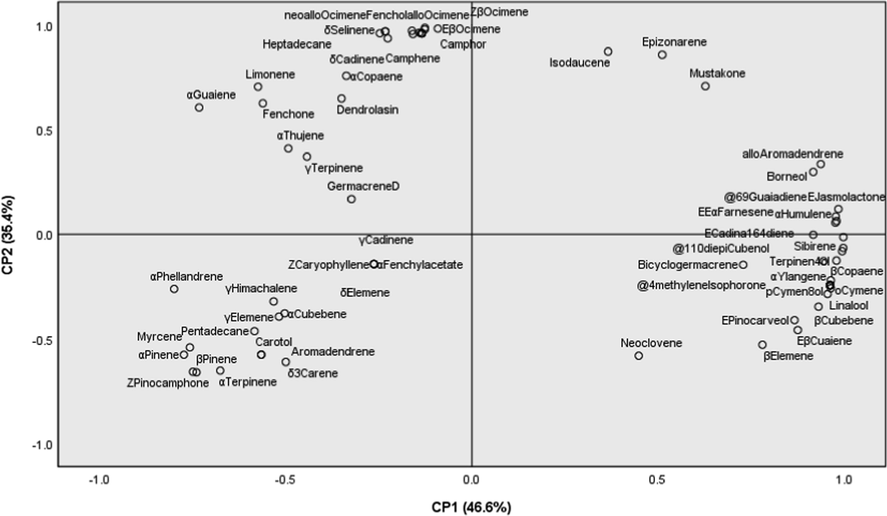

3.2 Statistical analysis of volatile components

In order to study the variability of chemical components within and between the studied populations, the Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) and the Principal Components Analysis (PCA) were carried out. This analysis was employed to provide an overview of chemical components of volatile oil based on GC–MS data. With a dissimilarity 77, the HCA using Ward’s method was indicated in three groups (A, B, and D) according to similarity of their chemical components (Fig. 2). The A group was characterized by the presence of β-pinene and α-pinene as major components. Group B was further indicated into two sub-groups (B1 and B2). Sub-group B1 was characterized by o-cymene, β-copaene, β-cubebene, γ-patchoulene, and α-humulene. Sub-group B2 consisted of limonene, (E)-β-ocimenene, allo-ocimene, (Z)-β-ocimene, thymol methyl ether, and camphene. With a dissimilarity of 64 components in group C. In addition, the PCA was employed to all volatile constituents. Fig. 3 shows a PCA plot of the volatile constituents of rhizomes and leaves of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum. The first principal components (PC1) explained 46.6 % of the variation across the samples, whereas the second principal components (PC2) explained 35.4 % of the variance. The samples exhibited similar major components, with different levels of adulteration. As shown in Fig. 3, the volatile distributions at negative axis were highly influenced by α-pinene, β-pinene, camphene, o-cymene, limonene, β-myrcene, (Z)-β-ocimene, (E)-β-ocimene, allo-ocimene, endo-Fenchyl acetate, caryophyllene, copaene, and aromadendrene, all of which were present in large amounts. The PCA results supported the differentiation of the samples obtained by the HCA analysis. The results indicated that the classification proposed by HCA and PCA is acceptable.

Dendrogram obtained by cluster analysis, representing chemical composition similarity relationships of 77 volatile components from the rhizomes and leaves of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum.

Principal component analysis (PCA) loading plots revealing the compounds present in rhizomes and leaves of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum.

3.3 Total phenolic content and antioxidant activities

The total phenolic content in different extracts of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum rhizomes are shown in Table 2. The total phenolic content of the extract was 2.9 ± 0.5 and 2.1 ± 0.6 mg gallic acid equivalence (mg GAE), respectively. From the results, total phenolic content was found to be lower than previous reports, A. chinense (8.3 mg GAE), A. tsao-ko (7.2 mg GAE), and A. villosum (9.3 mg GAE) (Gan et al., 2010; Butsat and Siriamornpun, 2016).

Antioxidant activities of the extracts were determined using DPPH, ABTS, and FRAP assays, respectively. As indicated in Table 2, the DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activity of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum rhizomes extracts were showed IC50 value of (179.8 ± 3.9 µg/mL, 392.9 ± 2.6 µg/mL) and (120.3 ± 2.5 µg/mL, 328.6 ± 3.3 µg/mL). Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control, with an IC50 value of 1.6 ± 0.8 µg/mL and 5.2 ± 0.8 µg/mL, respectively. For the FRAP value, the extracts showed the lowest reducing ability with FRAP value of 76.5 ± 7.8 µM ascorbic acid equivalence (mM AAE) and 84.9 ± 4.4 µM AAE, respectively. Similarly, some Amomum species exhibited lower antioxidant activity than synthetic antioxidant agents (Yang et al., 2010; Prakash et al., 2012). The A. kravanh and A. subulatum exhibited DPPH radical scavenging activity with IC50 value of 13.8 µg/mL and 431.2 µg/mL, respectively (Shrestha, 2017; Zhang et al., 2020). In addition, A. subulatum also presented an IC50 value of 8.3 µg/mL by DPPH assay (Prakash et al., 2012).

Phenolic compounds are secondary metabolites, which play important roles in neutralizing free radicals and preventing oxidative damage (Pintatum et al., 2020a, 2020b). In this study, the A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum rhizome extracts exhibited weak total phenolic content. This implies why the lowest antioxidant activity was indicated in the extracts. These results are in accordance with previous studies, reporting a correlation between phenolic contents and antioxidant properties (Owen et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2010; Minatel et al., 2016).

3.4 Tyrosinase inhibitory activity

The A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum rhizomes extracts showed weak tyrosinase inhibitory activity at 69.0 ± 3.6 mg kojic acid equivalence (mg KAE) and 53.7 ± 7.4 mg KAE (Table 2). Findings from this study, the lowest of total phenolic content and antioxidant properties would mean the lowest of tyrosinase inhibition ability, as well. The tyrosinase inhibitory effects may have depended on the phenolic compounds and antioxidant properties (Pintatum et al., 2020a, 2020b).

3.5 Antibacterial activity

The antimicrobial activity of the A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum rhizome extracts was investigated using the Mueller-Hinton broth microdilution method against eight types of resistant bacteria. As indicated in Table 3, A. dealbatum rhizomes extracts exhibited the smallest MIC value only to Gram-positive bacteria, Bacillus cereus and Bacillus subtilis in concentrations of 640 µg/mL. Whereas, the extracts showed less activity or were inactive toward the other bacteria strains in concentrations of 1280 µg/mL or more. In this study, vancomycin, gentamicin, and ampicillin were used as standard antibiotics.

Sample

Gram (+) Bacteria

Gram (-) Bacteria

B.

cereus

B.

subtilis

S.

aureus

S.

epidermidis

E.

coli

S.

typhimurium

Ps.

aeruginosa

Serratia

marcescens

A. argyrophyllum

1280

1280

1280

1280

–

1280

1280

–

A. dealbatum

640

640

1280

1280

–

1280

1280

–

Vancomycin

320

160

10

1280

–

–

–

–

Gentamicin

–

–

–

–

160

80

640

160

Ampicillin

–

320

5

320

80

640

1280

160

DMSO

1280

1280

–

1280

1280

–

1280

–

According to some researchers, some Amomum species have a wide variety of secondary metabolites such as tannins, alkaloids and flavonoids (Gurudutt et al., 1996). They play important roles in preventing oxidative damage and antimicrobial properties (Gurudutt et al., 1996; Pintatum et al., 2020a, 2020b). The essential oil isolated from A. subulatum showed good antimicrobial activity against B. pumilus, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, P. aeruginosa, and S. cerevisiae (Agnihotri and Wakode, 2010). In addition, the essential oil of A. tsao-ko also showed strongest antimicrobial activity against S. aureus (Yang et al., 2008). It was clear for the results, because the extracts contained less phenolic content and antioxidant properties. It could be the cause of lowest antimicrobial activity.

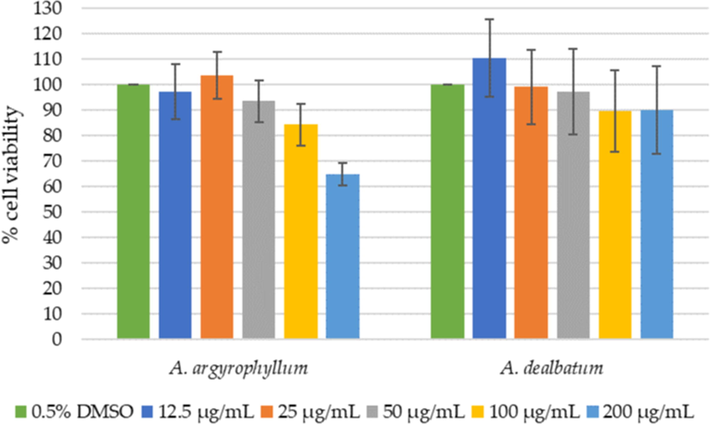

3.6 In vitro cytotoxicity

The crude rhizome extracts of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum were tested to assess cytotoxicity on HaCaT keratinocyte cells using MTT assay. The HaCaT keratinocyte cells were treated with increasing doses of extract, (12.5, 25, 50, 100, and 200 µg/mL) for 24 h. The cytotoxic effects of these extracts are presented in Fig. 4. Percentage of cell viability is reported as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. MTT results showed that exposure to 200 µg/mL concentrations of A. argyrophyllum extract inhibited the growth of cells, with percentages of cell viability of 65.2 ± 4.4 %. Nevertheless, the A. argyrophyllum extract in a concentration range of 12.5 – 100 µg/mL and A. dealbatum extract in all concentrations used did not inhibit the growth of the cell lines. The percentages of viable cells remained above 80 %, it is concluded that A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum does not exert a cytotoxic effect on HaCaT cells.

Relative HaCaT viability (%) by increasing concentrations of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum.

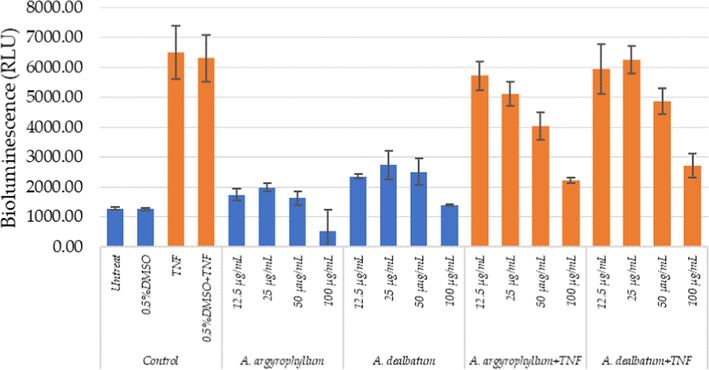

3.7 Anti-inflammatory activity

Anti-inflammatory activity was represented by the inhibitory effects on nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) reporter gene cells in TNF-α treated. The different treatments were applied to the cells. The luciferase reporter gene activity was measured in lysates in presence of ATP/luciferin reagent (Promega, WI, USA). The total emitted bioluminescence (relative light units, RLU) was measured during 30 s (Envision multiplate reader, Perkin Elmer). The result is shown in Fig. 5. The proinflammatory TNF-α increased luciferase gene expression, as compared to the control and extracts without TNF-α. The extracts displayed dose-dependent decreased luciferase gene expression. The extracts showed anti-inflammatory effects on NF-κB activity.

Anti‐inflammatory effects of A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum measured in HaCaT NF‐κB reporter gene cells.

TNF-α is another inflammatory cytokine that plays important role in some pain models, inflammatory, and neuropathic hyperalgesia (Zhang and An, 2007). The extracts and chemical constituents of some Amomum plants have been reported as antioxidant properties, and anti-inflammatory activity. From the previous report, labdane and norlabdane diterpenoids were isolated from the rhizomes of A. villosum. The compounds were evaluated for anti-inflammatory activity using inhibitory effects on nitric oxide (NO) production. The compounds from the rhizomes of A. villosum showed significant inhibition of NO production (Yin et al., 2019). In addition, the compounds isolated from dried fruits of A. tsaoko were also investigated for inhibitory effect on NO production. The compounds exhibited anti-inflammatory activity in a dose-dependent manner (Zhang et al., 2016). The A. compactum extract was examined for potential anti-inflammatory effects on LPS-induced inflammatory models. The measurement of accumulation of nitrite in the culture media. The results revealed that A. compactum extract decreased the production of NO and PGE2 (Lee et al., 2012). The present study A. argyrophyllum and A. dealbatum extracts showed moderate anti-inflammatory NF-κB effects. This could probably be due to the lower phenolic content and the radical scavenging activities.

4 Conclusion

This is the first report of the chemical profiles of the volatile fraction of fresh leaves and rhizomes of A. dealbatum and A. argyrophyllum. Antioxidant, antibacterial, tyrosinase inhibitory, cytotoxic, and anti-inflammatory activities have been studies because of the potential pharmacological and industrial usages. More than 49 compounds have been identified in volatile oils. The extracts are safe to use at 100 μg/mL in 24-h incubations with HaCaT human keratinocyte cells and exhibit moderate activity against bacterial strains and tyrosinase activity. Hence, it can be concluded that these plant extracts have potential value as a source of natural antioxidants, bio-functional additives in pharmaceutical products, and might have a future application.

Funding

This research was funded by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (Grant No. DBG6280007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Thailand Science Research and Innovation Fund (DBG6280007). Partial financial support and the Postdoctoral Fellowship from Mae Fah Luang University to Dr. Aknarin Pintatum were also acknowledged. We thank Mae Fah Luang University and the University of Antwerp for their laboratory facilities.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Citrus peel polymethoxyflavones, sudachitin and nobiletin, induce distinct cellular responses in human keratinocyte HaCaT cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.. 2018;82:2064-2071.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of Essential Oil Components by Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (fourth ed.). Carol Stream, IL, USA: Allured publishing Corporation; 2009. p. :1-804.

- Antimicrobial activity of essential oil and various extracts of fruits of greater cardamom. Indian. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2010;72:657-659.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of volatile oil between the fruits of Amomum villosum Lour. and Amomum villosum Lour. var. xanthioides T. L. Wu et Senjen based on GC-MS and chemometric techniques. Molecules.. 2019;24:1663.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological effects of essential oils – A review. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2008;46:446-475.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modified folin-ciocalteu antioxidant capacity assay for measuring lipophilic antioxidants. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2013;61:4783-4791.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessing medicinal plants from South-Eastern Spain for potential anti-inflammatory effects targeting nuclear factor-Kappa B and other pro-inflammatory mediators. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2009;124:295-305.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of solvent types and extraction times on phenolic and flavonoid contents and antioxidant activity in leaf extracts of Amomum chinense C. Int. Food Res. J.. 2016;23:180-187.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-inflammatory activity of flavonoids from Eupatorium arnottianum. J, Ethnopharmacol.. 2007;112:585-589.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diterpenes and kawalactone from the rhizomes of Amomum uliginosum. J. Koenig. Biochem. Syst. Ecol.. 2015;63:34-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new species of Amomum Roxb. (Zingiberaceae) from Northern Thailand. Taiwania.. 2008;53:6-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition of essential oils of Amomum villosum Lour. Am. J. Essent. Oil.. 2016;4:8-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study of antioxidant properties and total phenolic content of 30 plant extracts of industrial interest using DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, SOD, and ORAC assays. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2009;57:1768-1774.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pharmaceutical and therapeutic potentials of essential oils and their individual volatile constituents: a review. Phytother. Res.. 2007;21:308-323.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of natural antioxidants from traditional chinese medicinal plants associated with treatment of rheumatic disease. Molecules.. 2010;15:5988-5997.

- [Google Scholar]

- Technology, chemistry and bioactive properties of large cardamom (Amomum subulatum Roxb.): an overview. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Biotechnol.. 2016;4:139-149.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of mushroom and murine tyrosinase inhibitors from Achillea biebersteinii Afan. extract. Molecules.. 2021;26:964.

- [Google Scholar]

- Volatile constituents of large cardamom (Amomum subulatum Roxb.) Flavour. Fragr. J.. 1996;11:7-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of oven drying, microwave drying, and silica gel drying methods on the volatile components of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe) by HS-SPME-GC-MS. Dry. Technol.. 2012;30:248-255.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity of essential oil from the rhizomes of Amomum rubidum growing in Vietnam. Am. J. Essent. Oil.. 2019;7:11-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ascertainment of in vivo antidiarrheal and in vitro thrombolytic effect of ethanolic extract of leaves of Amomum dealbatum. J. Appl. Life Sci. Int.. 2019;21:49046.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new record and a new synonym in Amomum Roxb. (Zingiberaceae) in Thailand. Thai For. Bull. (Bot.). 2009;37:32-35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition of rhizome essential oils of Amomum agastyamalayanum and Amomum newmanii from South India. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants.. 2018;21:803-810.

- [Google Scholar]

- A revision of Amomum (Zingiberaceae) in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. Edinb. J. Bot.. 2012;69:99-206.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-inflammatory effects of Amomum compactum on RAW 264.7 cells via induction of heme oxygenase-1. Arch. Pharm. Res.. 2012;35:739-746.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetic potentials of extracts and compounds from Zingiber cassumunar Roxb. rhizome. Ind. Crops. Prod.. 2019;141:111764

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant aromatic butenolides from an insect-associated Aspergillus iizukae. Phytochem. Lett.. 2016;16:134-140.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tyrosinase, elastase, hyaluronidase, inhibitory and antioxidant activity of Sri Lankan medicinal plants for novel cosmeceuticals. Ind. Crops. Prod.. 2018;111:597-605.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethnomedicinal plants used by traditional healers in Phatthalung Province, Peninsular Thailand. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine.. 2015;11:1-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Constituents of Amomum tsao-ko and their radical scavenging and antioxidant activities. JAOCS.. 2000;77:667-673.

- [Google Scholar]

- Minatel, I.O., Borges, C.V., Ferreira, M.I., Gomez, H.A.G., Chen, C.O., Lima, G.P.P., 2016. Phenolic Compounds: Functional Properties, Impact of Processing and Bioavailability. https://www.intecho pen.com/chapters/53128. (accessed 11 October 2021).

- Olive-oil consumption and health: the possible role of antioxidants. Lancet. Oncol.. 2000;1:107-112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical Composition of essential oils from different parts of Zingiber kerrii Craib and their antibacterial, antioxidant, and tyrosinase inhibitory activities. Biomolecules. 2020;10:288.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and cytotoxic activities of four curcuma species and the isolation of compounds from Curcuma aromatica rhizome. Biomolecules. 2020;10:799.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antioxidant activity of large cardamom (leaves of Amomum subulatum) Int. J. Drug. Dev. Res.. 2012;4:175-179.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of the oil of large cardamom (Amomum subulatum Roxb.) growing in Sikkim. J. Essent. Oil Res.. 2003;15:265-266.

- [Google Scholar]

- Composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oil from the fruits of Amomum cannicarpum. Acta. Pharm.. 2006;56:473-480.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of sodium dodecyl sulphate as a formazan solvent and comparison of 3-(4,-5- dimethylthiazo-2-yl)-2,5- diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay with wst-1 assay in mcf-7 cells. Indonesian J. Pharm.. 2014;25:245-254.

- [Google Scholar]

- GC-MS analysis, antibacterial and antioxidant study of Amomum subulatum Roxb. J. Med. Plants.. 2017;5:126-129.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and biological activity of the essential oil of Amomum biflorum. Nat. Prod. Commun.. 2013;8:265-267.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition of essential oil of Amomum xanthioides Wall. ex Baker from Northern Vietnam. Biointerface. Res. Appl. Chem.. 2021;11:12275-12284.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial properties of essential oils from Thai medicinal plants. Fitoterapia. 2005;76:233-236.

- [Google Scholar]

- The antibacterial activity of selected plants towards resistant bacteria isolated from clinical specimens. Asian. Pac. J. Trop. Biomed.. 2016;6:16-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil of Amomum tsao-ko. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2008;88:2111-2116.

- [Google Scholar]

- Volatile phytochemical composition of rhizome of ginger after extraction by headspace solid-phase microextraction, petroleum ether extraction and steam distillation extraction. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol.. 2009;4:136-143.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxic, apoptotic and antioxidant activity of the essential oil of Amomum tsao-ko. Bioresour. Technol.. 2010;101:4205-4211.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-inflammatory and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of labdane and norlabdane diterpenoids from the rhizomes of Amomum villosum. J. Nat. Prod.. 2019;82:2963-2971.

- [Google Scholar]

- Silver nanoparticles exert a long-lasting antiproliferative effect on human keratinocyte HaCaT cell line. Toxicol. In. Vitro.. 2011;25:1053-1060.

- [Google Scholar]

- Screening of chemical composition, anti-arthritis, antitumor and antioxidant capacities of essential oils from four Zingiberaceae herbs. Ind. Crops. Prod.. 2020;149:112342

- [Google Scholar]

- Neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of diphenylheptanes from the fruits of Amomum tsaoko, a Chinese spice. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr.. 2016;71:450-453.

- [Google Scholar]