Translate this page into:

Identification of novel diclofenac acid and naproxen bearing hydrazones as 15-LOX inhibitors: Design, synthesis, in vitro evaluation, cytotoxicity, and in silico studies

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Chemistry, Hazara University, Mansehra 23200, Pakistan. obaid_chem@hu.edu.pk (Obaid-ur-Rahman Abid)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Inflammation is the immune system's adaptive response to tissue dysfunction or homeostatic imbalance, inducing fever, pain, physiological and biochemical changes via the cyclooxygenase (COX) and lipoxygenase (LOX) pathways. NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs), such as diclofenac acid and naproxen, are the most common inhibitors of the COX pathway. These drugs, however, are currently being studied as LOX inhibitors as well. Therefore, in the present study, a novel series of diclofenac acid and naproxen-bearing hydrazones 7(a-r) were designed, synthesized, and characterized by different spectroscopic methods like 1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR and HRMS (EI) analysis. All these synthesized compounds were evaluated for their in vitro inhibitory potential against the Soybean 15-lipoxygenase (15-LOX) enzyme. These compounds exhibited varying degrees of inhibitory potential ranging from IC50 4.61 ± 3.21 μM to 193.62 ± 4.68 μM in comparison to standard inhibitors quercetin (IC50 4.84 ± 6.43 μM) and baicalein (IC50 22.46 ± 1.32 μM). The most potent compounds in the series were compounds 7c (IC50 4.61 ± 3.21 μM), and 7f (IC50 6.64 ± 4.31 μM). These compounds were found least cytotoxic and showed 96.42 ± 1.3 % and 94.87 ± 1.6 % viability to cells at 0.25 mM concentration respectively. ADME and in silico studies supported the drug-likeness and binding studies of the molecules with the target enzyme.

Keywords

Diclofenac acid

Naproxen

Hydrazones

LOX inhibitors

Molecular docking studies

1 Introduction

Inflammation is the body's defensive response to infection or injury which is critical for both innate and adaptive immunity. It can be considered as part of the complex biological response of vascular tissues to harmful stimuli such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants (Ricciotti and FitzGerald, 2011). Once the tissue is damaged, membrane phospholipids produce arachidonic acid that gets oxidized either through the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway or the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway (Hanna and Hafez, 2018). COX pathway is mediated by cyclooxygenase enzyme that results in the production of biologically active species including thromboxanes, prostacyclin, and prostaglandins whose elevated levels cause an inflammatory response (Rouzer and Marnett, 2009). LOX pathway is mediated by a family of enzymes called lipoxygenases which convert arachidonic acid into leukotrienes that are the mediator of inflammation and allergic response thus being involved in diseases like asthma, cardiovascular diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes mellitus, carcinoma, bacterial or viral infections that lead to severe inflammation and some types of cancers (Kuhn and Banthiya, 2015; Van et al., 1998).

Lipoxygenases (LOXs) are non-heme iron-containing dioxygenases that catalyze the oxygenation of polyunsaturated fatty acids such as arachidonic acid (Jabbari et al., 2012; Brash, 1999). The crystal structure of different LOXs from microorganisms, plants, and mammals shows non-heme iron with conserved amino acids (Wennman et al., 2016). Several studies about the sequence identity of different LOXs from mammalian and plant origins revealed that maximum sequence identity between these LOXs members occurred in the area of the catalytic domain (Droege et al., 2017; Saura et al., 2017; Minor et al., 1996; Prigge et al., 1997). These significant outcomes attracted the medicinal chemists to soybean lipoxygenase (15-sLOX) which is cheaper and easily accessible than human LOXs to define the mechanisms of inhibition. Further, it was also found that 15-sLOX inhibitors are good inhibitors of human LOXs too (Armstrong et al., 2016).

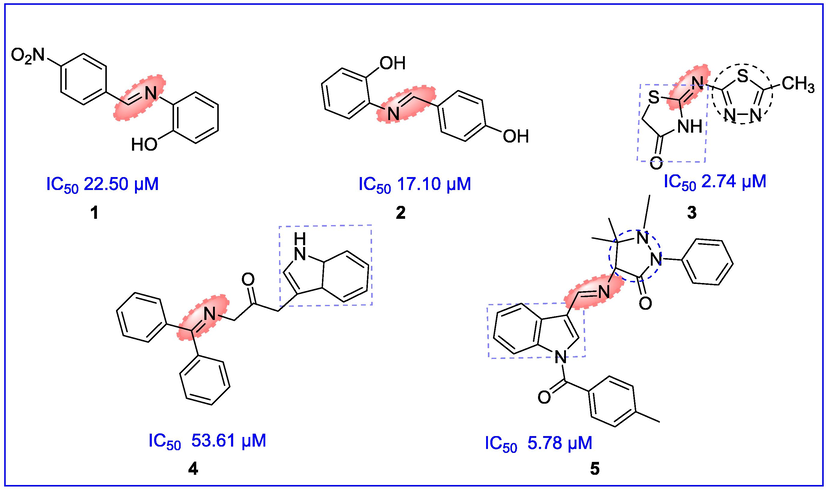

LOXs enzymes that are well conserved amongst mammalian specie, catalyze the production of proinflammatory mediators from arachidonic acids like leukotrienes, and eoxins (Adel et al., 2016; Green et al., 2016; Neves et al., 2020). They are classified according to the peroxidation site of the unsaturated fatty acid into 5-LOX, 12-LOX, and 15-LOX isoforms (Shen et al., 2017). Among these isoforms, 15-lipoxygenase (15-LOX) is one of the main metabolic pathways that alters arachidonic acid into 15-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (15-HETE) and additional pro-inflammatory mediators (Mousavian et al., 2020). 15-LOX and its metabolites have been implicated in various physiological processes including inflammatory, cardiovascular, hyperproliferative, neurodegenerative (like Alzheimer’s disease) and several other diseases (Prismawan et al., 2019; Eleftheriadis et al., 2015; Kayama et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2010; Guo et al., 2019; Checa and Aran, 2020). The literature study revealed that the direct involvement of 15-HETE results in inflammation, induced dysfunction of the retina in diabetic retinopathy, numerous categories of cancers, osteoarthritis, and multiple sclerosis (Singh and Rao, 2018; Elmarakby et al., 2019; Nawaz et al., 2019; Klil-Drori and Ariel, 2013; Safizadeh et al., 2018; Rossi et al., 2010). Quercetin and baicalein are used as 15-LOX inhibitors. Zileuton is the only approved 5-LOX inhibitor (You et al., 2020) that acts by chelating the iron metal located in the active site of the LOX enzyme and its unfavorable pharmacokinetic properties are associated with liver toxicity (Eleftheriadis et al., 2015). Moreover, the increased demand for anti-LOX therapies has enhanced the interest in developing new, safe, and effective LOX inhibitors. Although, various LOXs inhibitors have been reported (Vlag et al., 2019; Hu and Ma, 2018; Mirzaei et al., 2015) that are proved to be challenging to produce potent inhibitors with promising physiochemical properties (Youssif et al., 2019; Liaras et al., 2018; Aslam et al., 2016). Amongst them, imine containing derivatives such as compounds 1 (IC50 22.50 μM), and compound 2 (IC50 17.10 μM) were found potent LOX inhibitors (Omar et al., 2020; Aslam et al., 2016). Some compounds containing heterocycles with C⚌N functionality are common scaffolds as 15-LOX inhibitors, for example, compounds 3 (IC50 2.74 μM) having 1,3,4-thiadiazole-thiazolidinones hybrid with imine moiety and indole containing imine derivatives like compounds 4 and 5 inhibited LOX enzyme with IC50 value 53.61 µM and IC50 5.78 µM respectively (Afifi et al., 2019; Yar et al., 2014; Lamie et al., 2016). (Fig. 1).

Scaffolds reported as LOX inhibitors.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are the most widely used anti-inflammatory drugs to treat a variety of inflammatory diseases including several types of pain related to arthritis (Benbow et al., 2019; Gouda et al., 2016). These drugs inhibit the catalysis of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and prostacyclins through the cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway (Grosser et al., 2017). Recently, it is shown that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) not only inhibit the COX pathway but also LOX pathways (Shahid et al., 2021; Abbas et al., 2020). Diclofenac acid and naproxen belong to this class which has significant medical applications in arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis), pain, gout, joint swelling, ankylosing spondylitis etc (Ammar et al., 2017; Shah et al., 2018; Smith et al., 2017; Goldstein and Cryer, 2015). But, the chronic use of these drugs can adversely produce gastric ulceration and bleeding (Hafeez et al., 2018). This effect is associated with the direct contact of the free carboxylic group with the gastric mucosa (Fiorucci et al., 2001; Mendes et al., 2012) and decrease in the production of prostaglandins in tissue. However, NSAID-associated gastrointestinal complications can be decreased when NSAIDs are administered with gastroprotective agents such as histamine H2-receptor antagonists, prostaglandin E2 analogs, or proton-pump inhibitors (Graham and Chan, 2008; Lanza, 1998). There is still uncertainty as to which of these strategies is more effective or cost-effective. Thus, despite remarkable progress within the last decade, the development of a safe, effective, and inexpensive therapy for treating inflammatory conditions remains a challenge. To optimize the current risk and improve the therapeutic effect, synthetic approaches based on chemical modifications have been adapted. Several studies have described the derivatization of the carboxylate function of representative NSAID with the less acidic groups (Cacciatore et al., 2016; Rajić et al., 2009; Kausar et al., 2021; Muzaffar et al., 2021; Daud et al., 2022).

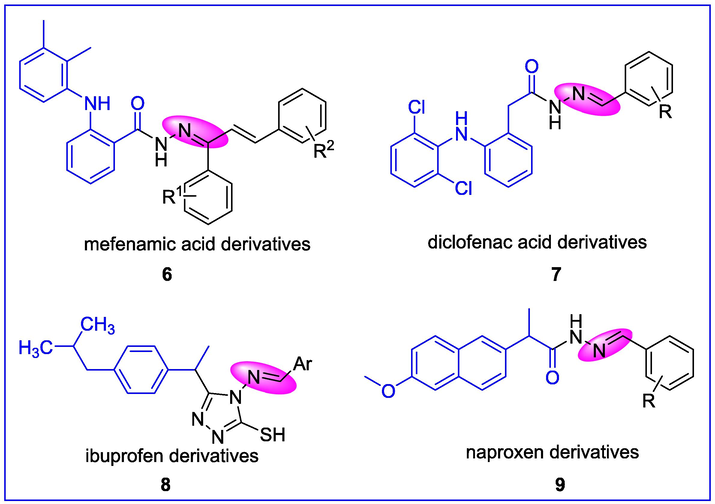

Hydrazones are a class of biologically active organic compounds in the Schiff base family (Raczuk et al., 2022) that have attracted the attention of medicinal chemists due to their wide range of pharmacological properties (Mamta et al., 2019; Pham et al., 2019; Krátký et al., 2017). These compounds are being synthesized as drugs by many researchers to combat diseases with minimal toxicity and maximal effects. Several hydrazone derivatives have been reported to exert notable biological activities (Asghar et al., 2020; Kocabalkanlı et al., 2017; Popiołek et al., 2020; Rahim et al., 2019). Some examples of NSAIDs derivatives 6–9 (Kumar et al., 2015; Bhandari et al., 2008; Sujith et al., 2009; Azizian et al., 2016) are depicted in Fig. 2 as potent anti-inflammatory agents.

NSAIDs derived hydrazones as anti-inflammatory agents.

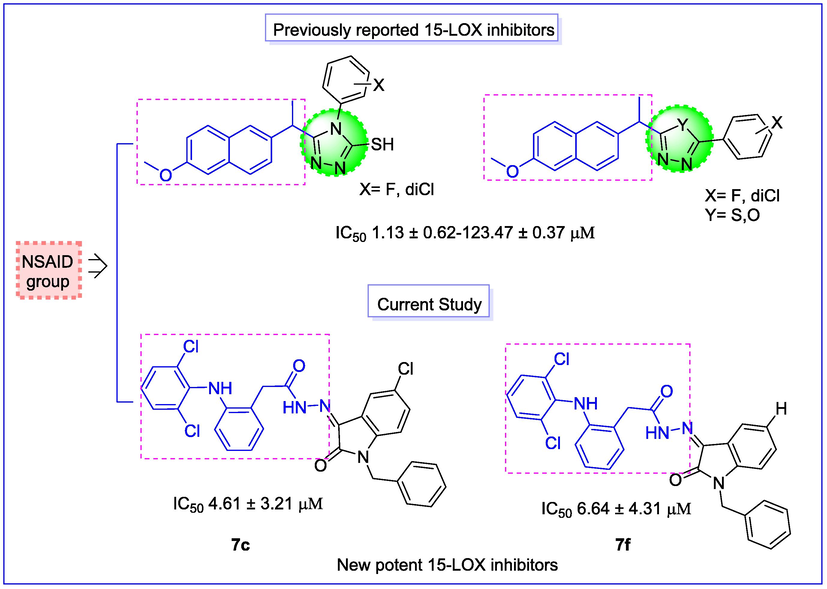

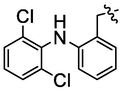

Recently our research group has identified some NSAIDs, including diclofenac acid, naproxen, ibuprofen, and their derivatives as potent 15-LOX inhibitors (Shahid et al., 2021; Sardar, 2022; Daud et al., 2022) Fig. 3.

Rationale of the current work.

In continuation of our previous work, in the present study, we report the synthesis of diclofenac acid and naproxen bearing hydrazones. All the synthesized derivatives were evaluated for 15-LOX inhibition, cytotoxicity, and ADME studies. In silico studies were carried out to find the binding interaction of the synthesized derivatives with the enzyme.

2 Results and discussion

2.1 Chemistry

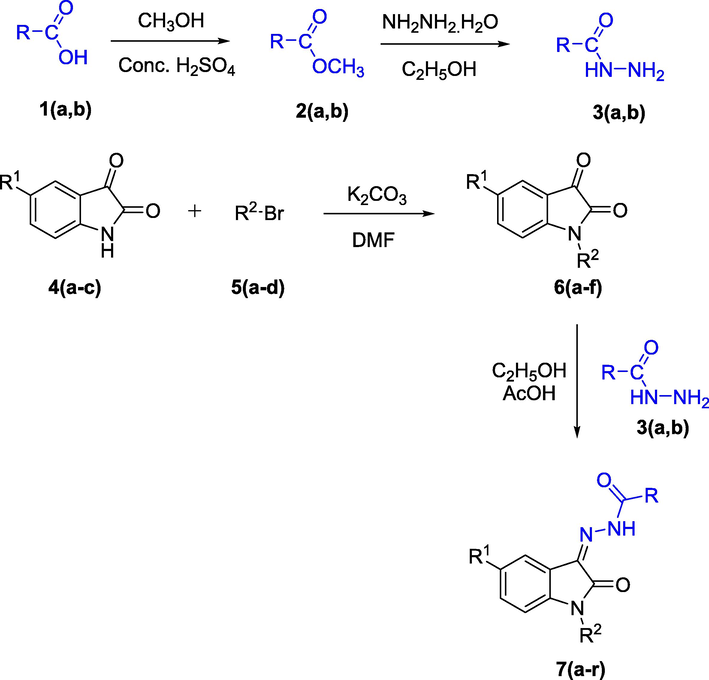

The synthesis of intermediate and target hydrazones 7(a-r) is illustrated in Scheme 1. Firstly, diclofenac acid and naproxen were converted to their hydrazides 3(a,b) via esterification (Ibrahim et al., 2018; Azizian et al., 2016). These products were confirmed through 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, in which the characteristics signal appeared at 9.09 ppm and 9.08 ppm which were assigned to amidic NH, in 1H NMR spectra while peaks at 171.18 ppm and 176.43 ppm in 13C NMR spectra confirmed compound 3(a,b) being synthesized. Then to synthesize intermediate 6(a-f), Isatin 4(a-c) was alkylated by its reaction with alkyl bromides 5(a-d) in the presence of K2CO3 using dimethylformamide (DMF) as a solvent. The synthesis of intermediate 6(a-f) was verified through 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and HRMS (EI) analysis. In the 1H NMR spectra the appearance of peaks at the range of 5.53–1.01 ppm in the up-field region assigned to the N-alkylated protons, confirmed the synthesis of intermediates 6(a-f), while all the aromatic protons appeared in their relevant range. In 13C NMR spectra of the same compounds, the appearance of peaks in the range of 189.1–186.1 ppm and 162.6–158.9 ppm were assigned to the two-carbonyl moiety, i.e., NC⚌O and C⚌O of the isatin ring, respectively, further confirmed the synthesis. Compounds 6(a-f) were further refluxed with hydrazides 3(a, b) in the presence of few drops of glacial acetic acid using ethanol as a solvent to afford hydrazone derivatives 7(a-r). The synthesis of desired hydrazone derivatives 7(a-r) was confirmed through 1H NMR,13C NMR, IR and, HRMS (EI) analysis. In 1H NMR spectra, the appearance of characteristics peaks in the range of 10.27–9.96 ppm was assigned to amidic NH moiety, while an additional peak at the range of 9.93–9.35 ppm in some compounds (7a, 7d, 7i, 7j, 7m, 7r) was assigned to NH group of isatin ring that confirmed the compounds 7(a-r) synthesis. All the aromatic protons appeared in their pertinent range. In 13C NMR spectra of the same series, the peaks that appeared at the characteristics range of 139.8–139.1 ppm were assigned to C⚌N functionality that confirmed the synthesis of hydrazone derivatives 7(a-r). Further confirmation of synthesized compounds was done by IR and HRMS (EI) analysis, which are summarized in the experimental section (see Table 1).

Synthesis of hydrazone derivatives 7(a-r).

S.No

R

R1

R2

S.No

R

R1

R2

7a

Cl

H

7j

Cl

H

7b

Cl

CH3CH2CH2—

7k

Cl

CH3CH2CH2—

7c

Cl

C6H5CH2—

7l

Cl

C6H5CH2

7d

H

H

7m

H

H

7e

H

CH3CH2CH2—

7n

H

CH3CH2CH2—

7f

H

C6H5CH2

7o

H

C6H5CH2

7g

H

CH2⚌CH—CH2—

7p

H

CH2⚌CH—CH2—

7h

H

CH3CH2CH2CH2—

7q

H

CH3CH2CH2CH2—

7i

NO2

H

7r

NO2

H

2.2 Biological evaluation

2.2.1 15-LOX inhibition and SAR

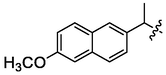

Eighteen diclofenac acid and naproxen-bearing hydrazones 7(a-r) were synthesized and evaluated for in vitro 15-LOX inhibition (Table 2). All derivatives of the whole series exhibited a varying degree of inhibitory potential with IC50 values ranging from 4.61 ± 3.21 μM to 193.62 ± 4.68 μM in comparison to quercetin (IC50 4.84 ± 6.43 μM) and baicalein (IC50 22.46 ± 1.32 μM) as standards. Limited structure–activity relationship (SAR) has been established for all derivatives of the series by incorporating a change at the hydrazide part (R) and slightly altering the substituents at the 5 position (R1) or at the N-substitution of the isatin ring (R2), respectively, as shown in Fig. 4. Data is mean ± sem, n = 3. NA = Not Active.

S.No.

15-LOX IC50 (μM)

Cell viability (%) at 0.25mM

S.No.

15-LOX IC50 (μM)

Cell viability (%) at 0.25mM

7a

12.62 ± 4.19

86.25 ± 1.2

7j

175.52 ± 4.27

70.12 ± 1.4

7b

11.64 ± 5.32

94.23 ± 1.5

7k

27.43 ± 4.39

84.77 ± 1.3

7c

4.61 ± 3.21

96.42 ± 1.3

7l

30.12 ± 6.32

71.57 ± 1.5

7d

22.52 ± 5.37

68.83 ± 1.7

7m

144.84 ± 6.43

78.12 ± 1.5

7e

20.25 ± 6.23

94.23 ± 1.5

7n

138.21 ± 3.31

66.25 ± 1.7

7f

6.64 ± 4.31

94.87 ± 1.6

7o

137.62 ± 5.48

70.12 ± 1.4

7g

55.12 ± 4.3

67.57 ± 1.7

7p

NA

39.3 ± 1.7

7h

34.63 ± 5.35

85.28 ± 1.3

7q

193.62 ± 4.68

74.4 ± 1.3

7i

65.32 ± 4.27

79.3 ± 1.9

7r

NA

52.5 ± 1.6

Quercetin

4.84 ± 6.43

–

–

4.84 ± 6.43

–

Baicalein

22.46 ± 1.32

–

–

22.46 ± 1.32

–

Cyclophosphamide

–

56.5 ± 1.6

–

–

56.5 ± 1.6

Cisplatin

–

51.7 ± 1.7

–

–

51.7 ± 1.7

Curcumin

–

73.9 ± 1.5

–

–

73.9 ± 1.5

General representation of hydrazone derivatives 7(a-r) for SAR analysis.

To simplify and determine SAR for 15-LOX inhibition, all the synthesized hydrazones derivatives 7(a-r) were divided into two categories, based on hydrazide moiety. Moreover, the detailed SAR was also rationalized based on substituent patterns at the indoline ring. Category A comprises nine compounds 7(a-i), where R represents the diclofenac group as the hydrazide part, while category B consists of the remaining nine compounds 7(j-r), representing R as the naproxen group. The variations in the inhibitory potential of these compounds might be due to different substituents at the isatin group and more due to the hydrazide part. Amongst category A, the compound 7c (IC50 4.61 ± 3.21 μM) was found as the most potent inhibitor, having a Cl group at 5-position of the isatin ring (R1) and benzyl group as an N-substituted group (R2). The second most potent compound was compound 7f (IC50 6.64 ± 4.31 μM), having no substituent as R1 but had the same benzyl group as R2. On comparing compound 7c with 7f, a slight change in inhibitory potential was observed that might be considered due to the Cl group and benzyl group. The third most active compound of the series was compound 7b (IC50 11.64 ± 5.32 μM), having the Cl group as R1 and propyl group as R2. The comparison of 7b with 7e (IC50 20.25 ± 6.23 μM) having no substituent at R1 but the same propyl group as R2. This change in inhibitory potential might be due to the presence of the Cl group at R1, which was absent otherwise. By switching to category B, two compounds i.e., compound 7k (IC50 27.43 ± 4.39 μM), and compound 7l (IC50 30.12 ± 6.32 μM) showed moderate activity, while the rest of the compounds showed poor activity. Compounds 7p and 7r showed no inhibition and were considered inactive. The two most active compounds of this category i.e., 7l, and 7k, having Cl group as R1 and propyl and benzyl group as R2, respectively, when compared with category A compounds, 7c (IC50 4.61 ± 3.21 μM) and 7b (IC50 11.64 ± 5.32 μM), having the same substitution pattern at R1 and R2 groups but different R group i.e., hydrazide part, a decrease in inhibitory activity was observed and this decrement was further worsened when the compound 7o (137.62 ± 5.48 μM) of the same category was collated to the category A compound 7f (IC50 6.64 ± 4.31 μM) which was the second most potent compound of the series. So, from these findings, it could be concluded that the derivatives with the chloro substitution at position 5 of the isatin ring (R1) exhibited good inhibitory potential but the variations in inhibitory potential were mainly affected by changing the hydrazide part (R) and also the diclofenac acid derivatives 7(a-i) were found to be more potent than naproxen derivatives 7(j-r). Consequently, these findings were further supported by molecular docking studies in order to understand the binding interactions of synthesized derivatives with the active site of the 15-LOX enzyme.

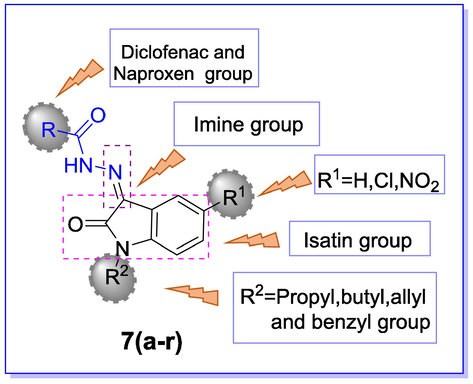

When the findings of our designed analogues were compared to the existing 15-LOX inhibitors, we observed that some of our derivatives outperformed the existing ones. In literature, Thiolox having a thiophene ring with IC50 value 12 µM (Eleftheriadis et al., 2016), NDGA (nordihydroguairetic acid) with IC50 value 11.0 ± 0.7 µM (Jameson et al., 2014), ML351 with IC50 value 200 nM (Rai et al., 2014), an indoline derivative with IC50 53.61 µM (Lai et al., 2010) are heterocyclic and aromatic 15-lipoxygenase inhibitors. In the comparison of these inhibitors some of our synthesized compounds like 7c (IC50 4.61 ± 3.21 μM), 7f (IC50 6.64 ± 4.31 μM), and 7b (IC50 11.64 ± 5.32 μM) showed potent 15-LOX inhibition and were found least cytotoxic and showed 96.42 ± 1.3 %, 94.87 ± 1.6 %, and 94.23 ± 1.5 % viability to cells at 0.25 mM concentration respectively Fig. 5.

Overlap study of synthesized derivatives with existing LOX inhibitors.

2.2.2 Cellular viability studies

Hydrazone derivatives 7(a-r) were screened for their cytotoxicity against MNCs (mononuclear cells) at 0.25 mM concentration, as mentioned in the experimental section. Compounds 7(a-r) exhibited 96.42 ± 1.3 to 39.3 ± 1.7 % cellular viability as determined by the MTT assay. Compound 8c was found to be the least toxic and showed 96.42 ± 1.3 % cell viability, followed by compounds 7f and 7e which exhibited 94.87 ± 1.6 % and 94.23 ± 1.5 % viability, respectively, and were least toxic toward MNCs amongst the series. The highly toxic compound 7p showed 39.3 ± 1.7 % cell viability which means it killed about 61.7 % of cells at 0.25 mM concentration in the assayed conditions and was also inactive against the enzyme 15-LOX. However, all the remaining compounds were less toxic even better than the standard cytotoxic drugs cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, and curcumin. The data altogether revealed that potent inhibitors showed greater cell viability and offered their candidature as lead compounds against 15-LOX viz compounds 7c, 7f, 7a, 7b, and 7e (Table 2).

2.2.3 ADME studies

The drug development processes need optimization of pharmacodynamics and require efficient delivery of drug to the target site and, therefore, are considered essential parameters in what is called ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion) studies. Med Chem Designer software ver. 3.0 was used for the prediction of ADME properties of molecules (Table 3). This has been explained in Lipinski’s rule of five. According to this rule, good oral bioavailability is observed if at least three of the following aspects are obeyed, that is, molecular weight should not be >500 Da; H-bond donors should not be >5; H-bond acceptors should not be >10; logP should not be >5 (Lipinski et al., 1997). Further, there is a close relation between polar surface area, rotatable bonds, and oral bioavailability of the drug. Drugs having a polar surface area <140 Å2 and rotatable bonds <10 are indicators of good orally bioavailable (Veber et al., 2002). The molecular properties of hydrazone derivatives 7(a-r) are given in Table 3. The molecular weights of almost all compounds were in close agreement with the standard value (〈5 0 0). All the compounds followed Lipinski’s rule, having hydrogen bonds <5. Drug lipophilicity defines the potential of molecules to cross cell membranes and bind to proteins, and it is calculated using logP or logD. The high lipophilic drug displays higher ADME properties, and values should be in a logP range between 2 and 4 or a logD between ∼1 and 3 (Waring, 2010). Compounds (7c, 7f, and 7k) represent logP, and logD values >5 have good potential to cross the cell membrane. In summary, several compounds show good lipophilicity and promising ADME profile with promising drug-likeness.

Comp.

MlogP

S+logP

S+logD

M. Wt

M_NO

T_PSA

HBDH

7a

4.268

4.739

4.732

475.738

6

82.6

3

7b

4.871

5.375

5.372

515.819

6

73.8

2

7c

5.427

5.917

5.910

563.863

6

73.8

2

7d

4.060

4.318

4.315

439.296

6

82. 6

3

7e

4.673

4.986

4.984

481.377

6

73.8

2

7f

5.240

5.526

5.524

529.421

6

73.8

2

7g

4.532

4.903

4.898

479.361

6

73.8

2

7h

4.8

5.57

5.567

495.404

6

73.8

2

7i

3.84

4.422

4.405

484.293

9

128.4

3

7j

3.849

4.628

4.616

407.854

6

79.8

2

7k

4.472

5.104

5.094

449.150

6

71.0

1

7l

5.049

5.697

5.688

497.979

6

71.2

1

7m

3.366

3.917

3.910

373.412

6

79.8

2

7n

4.000

4.452

4.447

415.493

6

71.6

1

7o

4.589

5.106

5.101

463.537

6

71.3

1

7p

3.928

4.18

4.174

413.173

6

71.1

1

7q

4.204

4.771

4.767

429.520

6

71.0

1

7r

3.485

3.985

3.972

418.409

9

125.6

2

2.3 Molecular docking

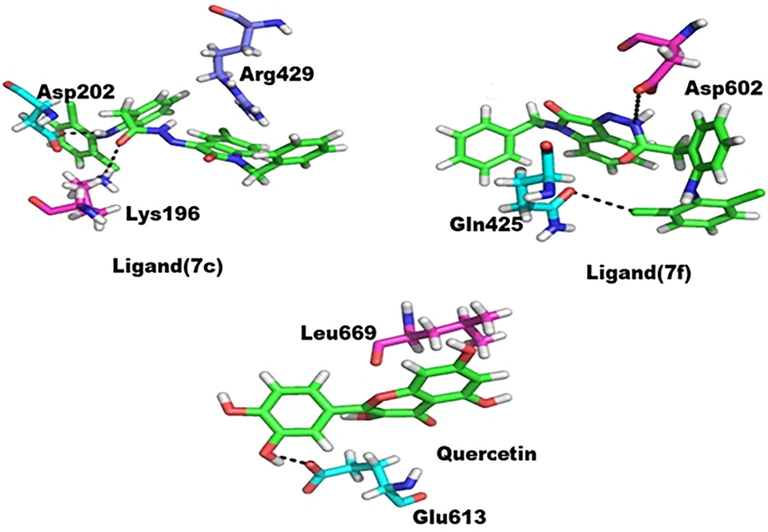

All active hydrazone derivatives 7(a-r) along with quercetin were docked into the active site of the enzyme. Among all the compounds, two compounds and quercetin were found with the best docking scores and ligand interactions. Compound 7c was found better among all the other compounds having the lowest docking score of −7.5186 (IC50 4.61 ± 3.21 μM). The compound formed three strong intermolecular bonds with active site residues of LOX. The nitrogen 12 and oxygen 3 of the compound formed hydrogen bonds with residue Asp202 and Lys196, respectively, as well the π -electrons of aromatic 6-ring formed π interaction with residue Arg429 with several hydrophobic interactions. The greater interaction of this compound may be because of the free π -electron of the terminal 6-ring (benzene). Similarly, because of high electronegativity, nitrogen and oxygen formed hydrogen bonding. The interaction details are given in Table 4 and Fig. 6. The compound 7f was also found with lower docking score of −7.2541 and stronger interaction likewise in in vitro studies. It formed two stronger hydrogen bonds with the enzyme. Cl 7 and nitrogen 18 formed interaction with Gln425 and Asp602, respectively. The compound has high electronegative electron withdrawing chlorine at aromatic ring of hydrazone which formed interaction with enzyme and similarly nitrogen 18 formed similar interaction (Table 4 and Fig. 6). Quercetin was also found with stronger affinity for the enzyme and bound strongly to the active site of enzyme forming two strong intermolecular interactions with lower docking score, i.e., −6.1451. The oxygen 18 of quercetin formed interaction with residue Glu613 and 6-ring with Leu669 (Table 4 and Fig. 6). Hence these three compounds may have the ability to strongly bind to the corresponding active site of enzyme.

Comp.

Docking Score

Interaction details

Ligand

No./position of atom

Receptor

Amino acid residue

Number of amino acid

Interaction

Distance (Å)

Energy (kcal/mol)

7a

−7.0878

O

5

NH2

ARG

429

H-acceptor

2.88

−3.7

7b

−7.1123

6-ring

NH1

ARG

429

π -cation

3.39

−0.6

7c

−7.5186

N

O

6-ring12

3OD1

NZ

NH2ASP

LYS

ARG202

196

429H-donor

H-acceptor

π-cation3.08

3.40

3.67−2.5

−0.8

−1.1

7d

−6.6649

N

9

OD1

ASP

602

H-donor

3.15

−1.5

7e

−6.8701

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

7f

−7.2541

Cl

N7

18OE1

OD1GLN

ASP425

602H-donor

H-donor3.41

2.96−1.1

−7.7

7g

−6.5423

N

18

OD1

Ile

604

H-donor

3.00

−6.7

7h

−6.8824

Cl

13

OE1

GLN

425

H-donor

3.42

−0.9

7i

−6.8492

N

46

OD1

ASP

602

H-donor

2.98

−2.4

7j

−6.4101

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

7k

−7.2115

O

8

NH2

ARG

429

H-acceptor

2.94

−1.1

7l

−6.9030

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

7m

−6.5772

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

7n

−6.6476

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

7o

−6.6652

6-ring

–

NH1

ARG

429

π-cation

4.38

−0.8

7q

−6.4726

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

Quercetin

−6.1451

O

6-ring18

-OE1

CBGLU

LEU613

669H-donor

π–H2.73

3.67−5.4

−1.0

Protein-ligand interaction, purple color shows ligand atoms.

3 Conclusions

In continuation of our studies in search for potential LOX inhibitors, hydrazones of diclofenac acid and naproxen 7(a-r) were designed, synthesized, and characterized with different spectroscopic methods like 1H NMR, 13C NMR, IR and HRMS (EI) analysis. The synthesized compounds were evaluated against the soybean 15-LOX enzyme. Almost all the compounds were found active as 15-LOX inhibitors especially 7c, and 7f, as potent inhibitors. These compounds maintained sufficient blood mononuclear cell viability, and in silico studies supported the drug-ligand interactions. The data collectively suggests the active molecules with the least toxicity are potential ‘lead’ molecules for further studies in the development of anti-LOX properties.

4 Experimental

4.1 General

All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich and Alfa aesar and were of analytical grade. Isatin, 2-(2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl) amino) phenyl) acetic acid (diclofenac acid) and 2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl) propanoic acid (naproxen) were obtained from alfa aesar. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were performed on Avance Bruker AV 400 MHz & 300 MHz (1H NMR) and 100 MHz & 75 MHz (13C NMR) NMR spectrophotometer, in deuterated solvent i.e., DMSO‑d6, while HRMS (EI) was recorded on a Finnegan MAT-311A mass spectrometer. Chemical shift (δ) was reported in ppm relative to TMS as an internal standard. Splitting pattern was reported as singlet (s), broad signal (br s), doublet (d), double of doublet (dd), triplet (t), double of triplet (dt), quartet (q), and multiplet (m). Through thin layer chromatography using TLC, pre-coated silica gel GF-254 aluminium plates (Kieselgel 60, 0.5 mm thick, E. Merck, Germany), and all synthesized compounds were initially confirmed and visualized by a UV lamp at 254 and 365 nm. Melting points of all synthesized compounds were determined in open capillary tubes using the Stuart melting point apparatus (SMP10) and were uncorrected.

4.2 General procedure for the synthesis methyl esters 2(a, b)

The methyl esters 2(a, b) of both drugs i.e., (diclofenac acid and naproxen) were prepared by treating their acids 1(a, b) (0.01 mol) with dry methanol (20 ml) in the presence of few drops of conc. H2SO4. The reaction mixture was refluxed for 6–7 h and monitored through TLC. After completion of the reaction, the excess solvent was evaporated and extracted through DCM and water (1:1.6) mixture to obtain a solid product that was further purified through recrystallization with ethanol.

Methyl 2-(2-(2,6-dichlorophenylamino) phenyl) acetate (2a)

White crystalline solid, Yield 86 %, m.p 98–99 °C; M. formula; C18H13Cl2NO2; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 7.44 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.25 (dd, J = 7.4, 2.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.08 (t, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.98 (td, J = 7.7, 3.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.94 (s, 1H,NH), 6.76 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.22 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 3.86 (s, 2H, CH2), 3.61 (s, 3H, OCH3).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 172.4, 145.0, 143.3, 130.8, 130.6, 129.4, 127.3, 125.4, 123.9, 119.2, 116.2, 52.2, 37.9.

Methyl-2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl) propanoate (2b)

White solid. Yield 82 %, m.p 91–93 °C; M. formula; C15H16O3; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 7.64 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.56 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.2 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.47 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.39 (dd, J = 8.2, 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.13 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H, Ar-H, Ar-H), 6.92 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 3.83 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.78 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, CHCH3), 3.62 (s, 3H, C—OCH3), 1.49 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CHCH3).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 174.4, 157.7, 137.4, 133.2, 129.2, 128.6, 127.3, 126.6, 125.3, 118.7, 105.6, 55.6, 51.9, 43.6, 18.5.

4.3 General method for the synthesis of hydrazides 3(a, b)

To a solution of methyl ester 2(a,b) (0.01 mol) in absolute ethanol (25 ml), hydrazine hydrate (0.02 mol) was added and the reaction mixture was refluxed for about 16–17 h. After completion of the reaction monitored through TLC, it was then concentrated, cooled until the solid product was formed. The solid thus separated out was filtered, dried and recrystallized from absolute ethanol to afford the corresponding hydrazides as intermediate 3(a,b).

2-(2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino)phenyl) acetohydrazide (3a)

White amorphous solid; Rf = 0.16 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 84 % m.p 134–136 °C; M. formula; C14H13Cl2N3O; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 9.09 (s, 1H, NH), 7.44 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.19–7.09 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.98 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.94 (s, 1H, NH), 6.79 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.22 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.28 (s, 2H, NH2), 3.44 (s, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 171.1, 143.6, 143.3, 130.6, 129.4, 129.1, 127.8, 125.4, 123.9, 123.2, 116.9, 38.3.

2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)propane hydrazide (3b)

Brown solid; Rf = 0.18 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 76 %; m.p 138–140 °C; M. formula; C14H16N2O2; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 9.08 (s, 1H, NH), 7.69 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.61 (dd, J = 8.0, 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.49 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.39 (dd, J = 8.0, 2.2 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.13 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H, Ar-H), 6.92 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.22 (s, 2H, NH2), 3.82 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.69 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, CHCH3), 1.45 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H, CHCH3).13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 176.4, 157.7, 139.8, 133.2, 129.1, 128.3, 127.2, 126.6, 125.2, 118.7, 105.6, 55.5, 44.9, 18.12.

4.4 General method for the synthesis of intermediate 6(a-f)

To a solution of isatin/5-chloroisatin (0.002 mol) in DMF, K2CO3 (0.0025 mol) was added gradually upon stirring and the whole mixture was stirred for half an hour. After this, different alkyl bromide 5(a-d) (0.002 mol) was added to the reaction mixture and the reaction mixture was refluxed for another 3–4 h. After completion of the reaction (monitored through TLC), the reaction mixture was poured into distilled water (50 ml). The solid thus formed was filtered, washed with water, and recrystallized using ethanol to afford pure products 6(a-f).

1-propylindoline-2,3-dione (6a)

Reddish solid; Rf = 0.33 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 82 %; m.p 68–70 °C; M. formula; C11H11NO2; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.65 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.60–7.50 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.12 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.28 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2CH3), 1.73–1.68 (m, 2H, NCH2CH2CH3), 1.01 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 3H, NCH2CH2CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 186.9, 160.9, 150.3, 137.2, 127.4, 122.8, 121.7, 116.3, 46.4, 23.5, 11.4. HRMS (EI) calcd for C11H11NO2 [M+]: 189.0790, found 189.0782.

1-benzylindoline-2, 3-dione (6b)

Orange solid; Rf = 0.34 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 74 %; m.p 133–135 °C; M. formula; C15H11NO2; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.91 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.74 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.54 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.27–7.24 (m, 5H, Ar-H), 7.12 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 5.53 (s, 2H, NCH2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 186.8, 162.6, 145.1, 136.8, 131.5, 128.6, 127.7, 127.4, 127.1, 122.8, 121.2, 111.9, 45.4. HRMS (EI) calcd for C15H11NO2 [M+]: 237.0790, found 237.0782.

1-butylindoline-2,3-dione (6c)

Bright orange solid; Rf = 0.38 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 73 %; m.p 93–95 °C. M. formula; C12H13NO2; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.65 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.60–7.50 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.12 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.67 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 2.16–1.05 (m, 2H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.53–1.42 (m, 2H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.04 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 3H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3).13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 187.3, 158.9, 148.9, 137.2, 127.4, 122.8, 121.6, 117.4, 48.1, 29.2, 19.4, 13.6. HRMS (EI) calcd for C12H13NO2 [M+]: 203.0946, found 203.0938.

1-allylindoline-2,3-dione (6d)

Brick red solid; Rf = 0.31 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 78 %; m.p 87–89 °C; M. formula; C11H9NO2; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.91 (d, J = 6.3 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.66 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.40 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.12 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 5.99–5.87 (m, 1H, NCH2CH⚌CH2), 5.18 (d, J = 10.7 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH⚌CH2), 4.90 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH⚌CH2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 189.1, 161.0, 150.9, 138.3, 133.6, 127.2, 122.8, 119.3, 117.7, 111.0, 39.5. HRMS (EI) calcd for C11H9NO2 [M+]: 187.0633, found 187.0625.

5-chloro-1-propylindoline-2,3-dione (6e)

Reddish crystalline solid; Rf = 0.34 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 78 %; m.p 113–115 °C; M. formula; C11H10ClNO2; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.09 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.70 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.59–7.50 (m, 1H, Ar-H), 4.28 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, Ar-H, NCH2CH2CH3), 1.78–1.62 (m, 2H, Ar-H, NCH2CH2CH3), 1.05 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 3H, Ar-H, NCH2CH2CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 186.1, 160.9, 144.3, 132.7, 128.3, 124.8, 122.8, 112.3, 46.3, 23.5, 11.4. HRMS (EI) calcd for C11H10ClNO2 [M+]: 223.0400, found 223.0392.

1-benzyl-5-chloroindoline-2,3-dione (6f)

Orange powder; Rf = 0.33 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 74 %; m.p 144–146 °C; M. formula; C15H10ClNO2; 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.88 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.58–7.49 (m, 1H, Ar-H), 7.37–7.07 (m, 5H, Ar-H), 5.54 (s, 2H, NCH2).13C NMR (75 MHz, CDCl3) δ 186.1, 162.6, 143.8, 136.8, 132.5, 128.5, 128.2, 127.7, 127.4, 124.6, 122.6, 112.4, 45.4. HRMS (EI) calcd for C15H10ClNO2 [M+]: 271.0400, found 271.0390.

4.5 General method for the synthesis hydrazones derivatives 7(a-r)

An equimolar mixture of hydrazides 3(a, b) (0.001 mol) and intermediates (Isatin/substituted Isatin 4(a-c) or N-alkylated Isatin 6(a-f) (0.001 mol)) was refluxed in ethanol in the presence of few drops of glacial acetic acid for about 2–3 h. The completion of the reaction was monitored through TLC. After completion of the reaction, excess solvent was evaporated and the solid separated out was thus filtered, washed with water and recrystallized with ethanol to obtain pure hydrazone derivatives 7(a-r).

N'-(5-chloro-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino)phenyl) acetohydrazide (7a)

Orange solid; Rf = 0.46 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 72 % m.p 222–228 °C. M. Formula; C22H15Cl3N4O2;1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.03 (s, 1H, NH), 9.73 (s, 1H, NH), 7.77 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.62 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.52–7.38 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.26 (s, 1H, NH), 7.12–6.98 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.86 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.67 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.23 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 3.60 (s, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.3, 168.7, 143.6, 143.4, 142.6, 139.1, 130.6, 129.4, 129.2, 129.1, 127.8, 126.2, 125.5, 123.9, 123.3, 122.8, 122.1, 118.5, 116.2, 38.5. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3248 (N—H), 3038 (C—H), 1665 (C⚌O), 1633 (N⚌CH), 672(C—Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C22H15Cl3 N4O2 [M+]: 472.0261 found 472.0253.

N'-(5-chloro-2-oxo-1-propylindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino)phenyl) acetohydrazide (7b)

Orange solid; Rf = 0.45 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 80 %; m.p 169–172 °C; M. formula; C25H21Cl3N4O2; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.12 (s, 1H, NH), 7.89 (d, J = 2.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.60–7.41 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.23 (s, 1H, NH), 7.10–6.98 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.87 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.70 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.26 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.28 (t, J = 4.3 Hz, 2H, CH2CH2CH3), 3.59 (s, 2H, CH2), 1.72–1.60 (m, 2H, CH2CH2CH3), 1.03 (t, J = 6.3 Hz, 3H, CH2CH2CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.4, 163.4, 143.6, 143.4, 139.1, 137.4, 131.4, 130.6, 129.4, 129.1, 127.8, 126.2, 125.5, 123.9, 123.3, 122.9, 122.2, 118.7, 116.7, 43.6, 38.5, 21.3, 11.4. IR (KBr, cm−1)): max 3307 (N—H), 3047 (C—H), 1662 (C⚌O), 1620 (N⚌CH), 671(C—Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C25H21Cl3N4O2 [M+]: 514.0730 found 514.0719.

N'-(1-benzyl-5-chloro-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino)phenyl) acetohydrazide (7c)

Yellow solid; Rf = 0.42 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 76 % m.p 212–219 °C; M. formula; C29H21Cl3N4O2;1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.04 (s, 1H, NH), 7.78 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.62 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 3H, Ar-H), 7.35–7.25 (m, 5H, Ar-H), 7.22 (s, 1H, NH), 7.10–7.05 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.93 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.79 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.30 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.94 (s, 2H, NCH2), 3.68 (s, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.4, 165.9, 143.6, 143.3, 139.2, 137.4, 136.5, 131.3, 130.6, 129.4, 129.1, 128.5, 127.8, 127.5, 127.4, 126.2, 125.4, 123.9, 123.2, 122.5, 122.2, 118.9, 116.4, 44.7, 38.4. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3243 (N—H), 3006 (C—H), 1671 (C⚌O), 1634 (N⚌CH), 648 (C—Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C29H21Cl3N4O2 [M+]: 562.0730 found 562.0718.

2-(2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino)phenyl)-N'-(2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)acetohydrazide (7d)

Yellowish orange solid; Rf = 0.42 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 70 % m.p 238–240 °C; M. formula; C22H16Cl2N4O2; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.27 (s, 1H, NH), 9.93 (s, 1H, NH), 7.85 (d, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.75 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.61 (td, J = 7.4, 1.3 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.47–7.24 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7. 26 (s, 1H, NH), 7.07–6.89 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 6.73 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.26 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 3.63 (s, 2H, CH2).13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 171.1, 168.3, 143.6, 143.4, 139.2, 135.9, 130.6, 129.4, 129.1, 127.8, 126.2, 124.7, 123.7, 122.6, 121.4, 120.2, 119.6, 118.4, 117.4, 38.5. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3242 (N—H), 2997 (C—H), 1660 (C⚌O), 1628 (N⚌CH), 639 (C—Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C22H16Cl2N4O2 [M+]: 438.0650 found 438.0637.

2-(2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino)phenyl)-N'-(2-oxo-1-propylindolin-3-ylidene)aceto hydrazide (7e)

Yellow cotton like solid; Rf = 0.45 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 64 % m.p 140–143 °C; M. formula; C25H22Cl2N4O2; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.04 (s, 1H, NH), 7.79 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.68 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.54–7.35 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.23 (s, 1H, NH), 7.09–7.00 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.92 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.73 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.24 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.28 (t, J = 4.3 Hz, 2H, CH2CH2CH3), 3.64 (s, 2H, CH2), 1.70–1.59 (m, 2H, CH2CH2CH3), 1.06 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H, CH2CH2CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 171.0, 163.5, 143.6, 143.4, 140.1, 137.8, 130.6, 129.4, 129.1, 128.2, 127.83, 125.5, 123.9, 123.3, 122.3, 121.2, 119.3, 117.0, 115.8, 43.6, 38.5, 21.3, 11.4. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3306 (N—H), 2989 (C—H), 1653 (C⚌O), 1638 (N⚌CH), 662 (C—Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C25H22Cl2 N4O2 [M+]: 480.1120 found 480.1107.

N'-(1-benzyl-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino)phenyl)aceto hydrazide (7f)

Light yellow solid; Rf = 0.44 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 70 % m.p 212–219 °C; M. formula; C29H22Cl2N4O2; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.05 (s, 1H, NH), 7.76–7.60 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.41–7.31 (m, 6H, Ar-H), 7.28–7.15 (m, 3H, Ar-H &NH), 7.09–7.04 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.87 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.24 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.96 (s, 2H, NCH2), 3.68 (s, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 171.0, 165.9, 143.6, 143.3, 140.1, 137.8, 136.6, 130.6, 129.4, 129.1, 128.5, 128.1, 127.8, 127.6, 127.4, 125.5, 123.9, 123.3, 121.6, 121.3, 119.4, 116.9, 115.2, 44.7, 38.4. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3230 (N—H), 3014 (C—H), 1685 (C⚌O), 1605 (N⚌CH), 680 (C—Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C29H22Cl2N4O2 [M+]: 528.1120 found 528.1109.

N'-(1-allyl-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino)phenyl)acetohydrazide (7g)

Yellow solid; Rf = 0.42 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 68 % m.p 163–165 °C; M. formula; C25H20Cl2N4O2;1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.05 (s, 1H, NH), 7.91 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.68 (dd, J = 7.2, 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.45 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.35–7.28 (m, 3H, NH & Ar-H), 7.10–7.05 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.93 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.79 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.30 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 5.99–5.87 (m, 1H, NCH2CH⚌CH2), 5.16 (d, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz NCH2CH⚌CH2), 4.90 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH⚌CH2), 3.68 (s, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.4, 163.8, 143.6, 143.3, 140.0, 137.8, 133.2, 130.6, 129.4, 129.1, 128.1, 127.8, 125.4, 123.9, 123.2, 121.9, 121.2, 119.3, 117.5, 116.9, 115.8, 42.3, 38.5. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3238 (N—H), 3082 (C—H), 1668 (C⚌O), 1615 (N⚌CH), 679 (C—Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C25H20Cl2N4O2 [M+]: 478.0963 found 478.0950.

N'-(1-butyl-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino)phenyl)aceto hydrazide (7h)

Light orange micro crystals; Rf = 0.49 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 75 % m.p 158–162 °C; M. formula; C26H24Cl2N4O2; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.04 (s, 1H, NH), 7.90 (dd, J = 6.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.63–7.46 (m, 5H, Ar-H), 7.25 (s, 1H, NH), 7.19–7.02 (m, 2H, Ar- H), 6.92 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.73 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.27 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.34 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 3.61 (s, 2H, CH2), 2.11 (quin, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.62–1.48 (m, 2H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.04 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 171.1, 163.4, 143.6, 143.4, 140.1, 137.9, 130.6, 129.4, 129.1, 128.2, 127.8, 125.5, 123.9, 123.3, 122.3, 121.2, 119.3, 117.4, 115.9, 46.8, 38.5, 29.3, 19.4, 13.5. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3210 (N—H), 3077 (C—H), 1665 (C⚌O), 1626 (N⚌CH), 673 (C—Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C26H24Cl2N4O2 [M+]: 494.1276 found 494.1263.

2-(2-((2,6-dichlorophenyl)amino)phenyl)-N'-(5-nitro-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)acetohydrazide (7i)

Orange solid; Rf = 0.36 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 78 % m.p 192–196 °C; M. formula; C22H15Cl2N5O4; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.13 (s, 1H, NH), 9.89 (s, 1H, NH), 7.99 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.89 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.77 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.44 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.26 (s, 1H, NH), 7.09–6.97 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 6.73 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 6.24 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 3.63(s, 2H, CH2). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 171.0, 168.7, 146.2, 143.6, 143.4, 142.2, 139.1, 130.6, 129.4, 129.1, 127.8, 125.5, 125.2, 123.9, 123.3, 119.8, 119.2, 117.6, 115.7, 38.5. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3253 (N—H), 3010 (C—H), (1645C⚌O), 1610 (N⚌CH), 628 (C-Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C22H15Cl2N5O4 [M+]: 483.0501 found 483.0488.

N'-(5-chloro-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)propanehydrazide (7j)

Yellow solid; Rf = 0.40 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 70 % m.p 230–232 °C. M. formula; C22H18ClN3O3; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.03 (s, 1H, NH), 9.47 (s, 1H, NH), 7.91 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.74–7.66 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.60 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.45 (dd, J = 7.3, 1.9 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.39 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.16–7.11 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 3.84 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.58 (q, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H, CH), 1.34 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H, CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.1, 168.7, 157.7, 142.6, 139.9, 139.4, 133.2, 129.1, 128.9, 128.3, 127.3, 126.6, 126.2, 125.3, 122.8, 122.1, 118.7, 114.2, 105.6, 55.6, 44.1, 18.1. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3271 (N—H), 3098 (C—H), 1677 (C⚌O), 1630 (N⚌CH), 638 (C—Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C22H18ClN3O3 [M+]: 407.1037 found 407.1024.

N'-(5-chloro-2-oxo-1-propylindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2yl)propane hydrazide (7k)

Yellow solid; Rf = 0.50 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 74 % m.p 142–146 °C; M. formula; C25H24ClN3O3; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.09 (s, 1H, NH), 7.77–7.69 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.56–7.46 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.29 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.15–7.08 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 6.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.62 (t, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2), 3.88 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.57 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H, CHCH3), 1.70–1.61 (m, 5H,CH2CH2CH3& CHCH3), 0.92 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H, CH2CH2CH3). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.4, 163.4, 157.7, 139.9, 139.1, 137.9, 133.2, 131.4, 129.1, 128.4, 127.3, 126.6, 126.2, 125.3, 122.9, 122.2, 118.7, 113.3, 105.6, 55.6, 44.1, 43.6, 21.3, 18.1, 11.4. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3235 (N—H), 3011 (C—H), 1671 (C⚌O), 1638 (N⚌CH), 647 (C-Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C25H24ClN3O3 [M+]: 449.1506 found 449.1489.

N'-(1-benzyl-5-chloro-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)propane hydrazide (7l)

Yellow solid; Rf = 0.45(n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 75 % m.p 156–160 °C; M. formula; C29H24ClN3O3; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.01 (s, 1H, NH), 7.97 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.83–7.78 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.75 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.62 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.49–7.43 (m, 6H, Ar-H), 7.18 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.90 (s, 2H, NCH2), 3.87 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.53 (q, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, CHCH3), 1.34 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 3H, CHCH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.3, 165.9, 157.7, 139.8, 139.2, 137.9, 136.5, 133.1, 131.3, 129.1, 128.5, 128.3, 127.7, 127.5, 127.2, 126.6, 126.2, 125.2, 122.5, 122.2, 118.7, 113.3, 105.6, 55.5, 44.7, 44.0, 18.1. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3244 (N—H), 3085 (C—H), 1655 (C⚌O), 1624 (N⚌CH), 666 (C—Cl). HRMS (EI) calcd for C29H24ClN3O3 [M+]: 497.1506 found 497.1491.

2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)-N'-(2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene) propane hydrazide (7m)

Yellow solid; Rf = 0.40 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 71 % m.p 217–220 °C; M. formula; C22H19N3O3; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.03 (s, 1H, NH), 9.69 (s, 1H, NH), 7.96 (dd, J = 7.0, 1.6 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.87 (dd, J = 7.3, 1.9 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.79–7.66 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.51–7.36 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.15–7.13 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 3.83 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.58 (q, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H, CHCH3), 1.33 (s, 3H, CHCH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.4, 168.3, 157.7, 139.9, 139.5, 135.9, 133.2, 129.1, 128.4, 127.3, 126.6, 125.3, 121.7, 121.1, 119.4, 119.0, 118.7, 111.4, 105.6, 55.6, 44.1, 18.1. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3290 (N—H), 3008 (C—H), 1667 (C⚌O), 1640 (N⚌CH). HRMS (EI) calcd for C22H19N3O3 [M+]: 373.1426 found 373.1413.

2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)-N'-(2-oxo-1-propylindolin-3-ylidene)propanehydrazide (7n)

Yellow micro crystals; Rf = 0.43 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 70 % m.p 131–134 °C; M. formula; C25H25N3O3; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.17 (s, 1H, NH), 7.92 (dd, J = 6.0, 1.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.83–7.78 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.72 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.62 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.48 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.36–7.27 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.18 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.23 (t, J = 5.4 Hz, 2H NCH2CH2CH3), 3.87 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.58 (q, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, CHCH3), 1.75–1.65 (m, 2H NCH2CH2CH3), 1.33 (d, J = 5.1 Hz, 3H, CHCH3), 1.00 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 3H, NCH2CH2CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.3, 163.4, 157.7, 140.0, 139.8, 138.4, 133.2, 129.1, 128.3, 128.0, 127.2, 126.6, 125.2, 122.2, 121.2, 119.2, 118.7, 111.7, 105.6, 55.5, 44.0, 43.6, 21.2, 18.1, 11.3. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3257 (N—H), 3082 (C—H), 1674 (C⚌O), 1635 (N⚌CH). HRMS (EI) calcd for C25H25N3O3 [M+]: 415.1896 found 415.1879.

N'-(1-benzyl-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(6-methoxy naphthalen-2-yl)propanehydrazide (7o)

Yellow solid; Rf = 0.43 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 68 % m.p 179–183 °C; M. formula; C29H25N3O3; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.19 (s, 1H, NH), 7.99 (dd, J = 6.3, 1.3 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.73–7.65 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.58 (td, J = 6.7, 1.2 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.49–7.43 (m, 1H, Ar-H), 7.40 (dd, J = 8.3, 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.34–7.24 (m, 5H, Ar-H), 7.13 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.06 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.3 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.94 (s, 2H, NCH2), 3.84 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.57 (q, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H, CHCH3), 1.34 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H, CHCH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.4, 165.9, 157.7, 140.1, 139.9, 138.5, 136.6, 133.2, 129.1, 128.5, 128.4, 128.1, 127.8, 127.6, 127.3, 126.6, 125.3, 121.6, 121.3, 119.4, 118.7, 111.7, 105.6, 55.6, 44.7, 44.1, 18.1. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3232 (N—H), 3063 (C—H), 1656 (C⚌O), 1612 (N⚌CH). HRMS (EI) calcd for C29H25N3O3 [M+]: 463.1896 found 463.1883.

N'-(1-allyl-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(6-methoxy naphthalen-2-yl)propanehydrazide (7p)

Yellow solid; Rf = 0.45 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 64 % m.p 97–99 °C; M. formula; C25H23N3O3; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.08 (s, 1H, NH), 7.93 (dd, J = 6.4, 1.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.75–7.65 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 7.58 (td, J = 6.7, 1.3 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.47–7.37 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.17–7.10 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 5.97–5.89 (m, 1H, NCH2CH⚌CH2), 5.19–5.12 (m, 2H, NCH2CH⚌CH2), 4.89 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH⚌CH2), 3.85 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.57 (q, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, CHCH3), 1.35 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 3H, CHCH3).13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.3, 163.8, 157.0, 140.1, 139.8, 138.5, 133.2, 133.2, 129.1, 128.4, 128.1, 127.3, 126.6, 125.3, 121.9, 121.2, 119.3, 118.74, 117.5, 111.7, 105.6, 55.6, 44.1, 42.3, 18.1. IR (KBr, cm−1): max3256 (N—H), 3030 (C—H), 1681 (C⚌O), 1599 (N⚌CH). HRMS (EI) calcd for C25H23N3O3 [M+]: 413.1739 found 413.1727.

N'-(1-butyl-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)-2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)propane hydrazide (7q)

Yellow solid; Rf = 0.36 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 70 % m.p 94–96 °C; M. formula; C26H27N3O3; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 9.96 (s, 1H, NH), 7.82 (dd, J = 6.4, 1.3 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.75 (dd, J = 6.5, 1.3 Hz, 1H, Ar-H),7.66–7.59 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.51 (td, J = 6.7, 1.2 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.41–7.33 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.13 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 6.99 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 4.34 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 3.83 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.56 (q, J = 6.2 Hz, 1H, CHCH3), 2.11 (quin, J = 6.2 Hz, 2H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3),1.48–1.40 (m, 2H, NCH2CH2CH2CH3), 1.34 (d, J = 5.2 Hz, 3H, CHCH3), 1.04 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 3H, CH2CH2CH2CH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.4, 163.4, 157.7, 140.1, 139.8, 138.5, 133.2, 129.1, 128.4, 128.1, 127.3, 126.6, 125.3, 122.3, 121.2, 119.3, 118.7, 111.8, 105.6, 55.6, 46.8, 44.1, 29.3, 19.4, 18.1, 13.5. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3258 (N—H), 3050 (C—H), 1675 (C⚌O), 1601 (N⚌CH). HRMS (EI) calcd for C26H27N3O3 [M+]: 429.2052 found 429.2039.

2-(6-methoxynaphthalen-2-yl)-N'-(5-nitro-2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)propanehydrazide (7r)

Yellow solid; Rf = 0.39 (n-hexane: ethyl acetate 4:1); Yield 80 % m.p.230–233 °C; M. formula; C22H18N4O5; 1H NMR (300 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 10.03 (s, 1H, NH), 9.35 (s, 1H, NH), 8.33 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 8.14 (dd, J = 7.5,2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.99 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.83–7.78 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 7.72 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.52 (dd, J = 8.4, 2.1 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.34 (d, J = 2.7 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.22 (dd, J = 7.5,2.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 3.87 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.58 (q, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, CHCH3), 1.33 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 3H, CHCH3). 13C NMR (75 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δ 170.3, 168.7, 157.7, 146.2, 142.1, 139.8, 139.3, 133.1, 129.1, 128.3, 127.2, 126.6, 125.5, 125.2, 119.7, 119.1, 118.7, 113.0, 105.6, 55.6, 44.0, 18.1. IR (KBr, cm−1): max 3246 (N—H), 2926 (C—H), 1666 (C⚌O), 1620 (N⚌CH). HRMS (EI) calcd for C22H18N4O5 [M+]: 418.1277 found 418.1268.

4.6 Biological evaluation

4.6.1 15-LOX inhibition assay

The assay was carried out using the previously described method (Sardar, 2022; Kondo et al., 1994). In a total volume of 100 µL of the reaction mixture, 60 µL of borate buffer (200 mM, pH 9.0), 10 µL of test compound or solvent, and 10 µL enzyme solution (soybean 15-LOX) were added, and the contents were incubated for five minutes at 25 °C in the dark. The luminescence was measured using a 96-well plate reader (Synergy HTX, BioTek, USA) in luminescence mode after a 10 µL solution of luminol (3 nM) containing cytochrome c (1 nM) was added to each well. The reaction was started by adding 10 µL of linoleic acid substrate solution. Chemiluminescence was timed between 100 and 300 s. All of the experiments were done in triplicate. As a positive control, quercetin and baicalein were utilized. The % inhibitions of the active substances were obtained after successive dilutions. Using Ez-Fit enzyme kinetics software, the IC50 was calculated.

4.6.2 Cell viability assay

The cell viability assay was carried out as reported earlier (Muzaffar et al., 2021). Mononuclear cells were separated by loading fresh blood taken from healthy volunteers onto lymphocyte separation medium (density 1.077 g/mol) and used in the MTT assay as described (Sardar, 2022).

4.7 Molecular docking

In order to explore the binding modes of newly synthesized compounds in the active site of LOX enzyme, all the compounds were docked into the binding pocket of LOX using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE). The crystal structure of human 15-lipoxygenase (15-LOXh) with PDB code 4NRE was downloaded from protein data bank. The protein structure was prepared using the preparation module of MOE and was subjected for 3D protonation and finally was energy minimized to get a stable conformation of the target protein. All compounds were subjected to MOE for protonation and energy minimization using the default parameters (gradient: 0.05, Force Field: MMFF94X). The default parameters of MOE were used for molecular docking purpose, i.e., Placement: Triangle Matcher, Rescoring-1: London dG, Refinement: Forcefield, Rescoring-2: GBVI/WSA. For each ligand, total ten conformations were allowed to generate, and the top-ranked conformations based on docking score were selected for protein–ligand interaction profile analysis. Ligand interaction and visualization were carried out via Pymol.

Funding

We are thankful to Higher Education Commission Pakistan for funding apart of this work vide project No. 4950 to M. Ashraf and project No. 5720 to O-u-R Abid. This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R95), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia for funding this work through Research Groups Program under grant number R. G.P.1:255/43.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Higher Education Commission Pakistan for funding apart of this work vide project No. 4950 to M. Ashraf and project No. 5720 to O-u-R Abid. The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2022R95), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia for funding this work through Research Groups Program under grant number R. G.P.1:255/43.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Life Sci.. 2020;1:92-97.

- [CrossRef]

- PNAS. 2016;113:4266-4275.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Chem.. 2019;87:821-837.

- [CrossRef]

- Synth. Commun.. 2017;47:1341-1367.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2016;24:1183-1190.

- [CrossRef]

- RSC Advances. 2020;10:19346-19352.

- [CrossRef]

- Med. Chem. Res.. 2016;25:109-115.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Saudi Chem. Soc.. 2016;20:45-48.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Mol. Graph.. 2016;67:127-136.

- [CrossRef]

- Ind. Pharm.. 2019;45:1849-1855.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2008;16:1822-1831.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:23679-23682.

- [CrossRef]

- Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2016;17:1035.

- [CrossRef]

- Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2020;21:9317.

- [CrossRef]

- Arch. Pharm.. 2022;355:2200013.

- [CrossRef]

- Med. Chem. Res.. 2022;31:316-336.

- [CrossRef]

- Biochem.. 2017;56:5065-5074.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Med. Chem.. 2015;58:7850-7862.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Med. Chem.. 2015;58:7850-7862.

- [CrossRef]

- Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2016;122:786-801.

- [CrossRef]

- Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2019;1864:1669-1680.

- [CrossRef]

- Dig. Liver Dis.. 2001;33:35-43.

- [CrossRef]

- Drug Healthc. Patient Saf.. 2015;7:31-41.

- [CrossRef]

- Molecules. 2016;21:201.

- [CrossRef]

- Gastroenterol.. 2008;134:1240-1246.

- [CrossRef]

- Biochem.. 2016;55:2832-2840.

- [CrossRef]

- Trends in Pharmacol. Sci.. 2017;38:733-748.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Med. Chem.. 2019;62:4624-4637.

- [CrossRef]

- Synth. Commun.. 2018;49:1-26.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Adv. Res.. 2018;11:23-32.

- [CrossRef]

- Med. Chem. Comm.. 2018;9:212-225.

- [CrossRef]

- Int. J. Med. Chem.. 2018;2018:1-11.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2012;20:5518-5526.

- [CrossRef]

- Plos One. 2014;9:e104094.

- Bioorg. Chem.. 2021;106:104499

- [CrossRef]

- J. Exp. Med.. 2009;206:1565-1574.

- [CrossRef]

- Prostag. Oth. Lipid M.. 2013;106:16-22.

- [CrossRef]

- Arch. Pharm.. 2017;350:1700010.

- [CrossRef]

- Biosci. Biotech. Biochem.. 1994;58:421-422.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2017;27:5185-5189.

- [CrossRef]

- Biochim. Biophys. Acta.. 2015;1851:308-330.

- [CrossRef]

- Med. Chem. Res.. 2015;24:2580-2590.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2010;20:7349-7353.

- [CrossRef]

- Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2016;123:803-813.

- [CrossRef]

- Am. J. Gastroenterol.. 1998;93:2037-2046.

- [CrossRef]

- Molecules. 2018;23:685.

- [CrossRef]

- Adv. Drug Del. Rev.. 1997;23:3-25.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Chem.. 2019;86:288-295.

- [CrossRef]

- Rev. Bras. Reumatol.. 2012;52:767-782.

- [CrossRef]

- Biochem.. 1996;35:10687-10701.

- [CrossRef]

- ChemPhysChem.. 2015;16:2260-2266.

- [CrossRef]

- Iran J. Basic Med. Sci.. 2020;23:984-989.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Chem.. 2021;107:104525

- [CrossRef]

- Prog. Retin. Eye Res.. 2019;72

- [CrossRef]

- Diabetol. Metab. Syndr.. 2020;12:99.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Chem.. 2020;97:103657

- [CrossRef]

- Molecules. 2019;24:4000.

- [CrossRef]

- Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2020;130:110526

- [CrossRef]

- Biochimie.. 1997;79:629-636.

- [CrossRef]

- Helvetica Chimica Acta. 2019;102:e1900040.

- Molecules. 2022;27:787.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Chem.. 2019;91:103112

- [CrossRef]

- J. Med. Chem.. 2014;57:4035-4048.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem.. 2009;24:1179-1187.

- [CrossRef]

- Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol.. 2011;31:986-1000.

- [CrossRef]

- Br. J. Pharmacol.. 2010;161:555-570.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Lipid. Res.. 2009;50:S29-S34.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Neuroimmunol.. 2018;325:32-42.

- [CrossRef]

- JSCS 2022:101468.

- [CrossRef]

- Chem. - A Eur. J.. 2017;24:962-973.

- [CrossRef]

- Med. Chem.. 2018;14:674-687.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Chem.. 2021;110:104818

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2017;27:3653-3660.

- [CrossRef]

- Prog. Lipid Res.. 2018;73:28-45.

- [CrossRef]

- Cell Chem. Biol.. 2017;24:281-292.

- [CrossRef]

- Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2009;44:3697-3702.

- [CrossRef]

- Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol.. 1998;38:97-120.

- J. Med. Chem.. 2002;45:2615-2623.

- [CrossRef]

- Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2019;174:45-55.

- [CrossRef]

- Expert Opin. Drug Discov.. 2010;5:235-238.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Biol. Chem.. 2016;291:8130-8139.

- [CrossRef]

- Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:922-929.

- [CrossRef]

- J Iran Chem Soc.. 2014;11:369-378.

- [CrossRef]

- Toxicol. Sci.. 2020;175:220-235.

- [CrossRef]

- Bioorg. Chem.. 2019;85:577-584.

- [CrossRef]