Translate this page into:

Ephedra mediated green synthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and evaluation of its antioxidant, antipyretic, anti-asthmatic, and antimicrobial properties

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

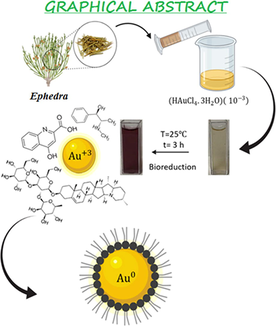

Green biosynthesis of Ephedra-AuNPs. Characterization techniques used to analyze the Ephedra-AuNPs are UV–Visible absorption spectra, FTIR, HRTEM, EDX, XPS, and XRD. Applications of Ephedra-AuNPs in light of antioxidant assay; antipyretic activity, antiasthma activity and antimicrobial activity.

Abstract

The eco-friendly green bio-synthesis of Ephedra-AuNPs was constructed from Ephedra plant extract. The synthesis process was optimized using different volumes of Ephedra-extract, 10-3M (HAuCl4·3H2O) solution, reaction temperature, time, and pH of the solution. Where, 4 mL of Ephedra-extract, 6 mL of 10-3M (HAuCl4·3H2O) solution at 25 °C for 3 h at a pH of 4 are showed the optimum reaction parameters respectively. The characterization of AuNPs was verified by UV–vis. spectrophotometer, FTIR, microscopic techniques (TEM, HRTEM), Zeta potential, and X-ray techniques (XRD, EDX, XPS). The nanoparticles are extremely important materials in emerging the future sustainable technologies for the living beings. The AuNPs were employed in biological assays where ABTS assay used to investigate the antioxidant activity. The in-vivo study of AuNPs was executed to study the anti-pyretic and anti-asthma activities of Ephedra-AuNPs. Ephedra-AuNPs of 1.3 nm to 15.6 nm size were achieved which have as importance as proficient to bind with the biological systems. The Ephedra-AuNPs prepared exploiting Ephedra-extract which is considered to be influential anti-asthma agent and antipyretic agent reduced the fever by 83.3 % at . Further the Ephedra-AuNPs used to scrutinize the anti-bacterial activities for Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria moncytogenes, Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella typhimurium, and anti-fungal activities on Candida albicans, Aspergillus nigra and Aspergillus flavus. The synthesized Ephedra-AuNPs exhibited great potential activities comparable to the standard drugs in case of Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Candida albicans with the zone of inhibition of 25 ± 0.5 nm, 26 ± 0.6 nm and 24 ± 0.7 nm respectively. It is believed that the synthesized Ephedra-AuNPs to be a hopeful option intended for diverse biological applications.

Keywords

Ephedra-extract

Antioxidant

Antipyretic

Antiasthma properties

Antimicrobial studies

1 Introduction

Nanotechnology is materialized as a fastest expanding research thrust for manufacturing, depiction, and manipulation of materials at nano-scale. It leads to structural modifications, execution and its rapid production is captured considerable attention round the globe (Al-Radadi et al., 2022; Narband et al.,2009; Sone et al., 2020). The nanomaterials are well thought-out to be the encouraging entities containing apposite size particles (1 to 100 nm) (Abdullah et al., 2022) to bind with the biological systems. The uniting of nano materials and biological systems leads to the convergence of these technologies and surfaced into a new field nano-biotechnology (Marooufpour et al., 2019; Shah et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2008). The nano-biotechnology attracted extensive research focus due to the applications of nanoparticles, nano-sized materials/devises in the diagnosis of biological systems (Al-Radadi, 2022a; Al-Radadi, 2022b; Al-Radadi & Abu-Dief, 2022; Baptista et al., 2008). The defining characteristic possessions of nanoparticles are the tiny size and a huge surface which grant great concentration to accomplish their chemical physical, magnetic, and optoelectronic properties (Elias E Elemike., 2017; Modena et al., 2019). The controlled experiments of shape and size allocation of nanoparticles endow with desired properties such as biological, optical absorption, thermal, catalytic, electrical conductivity, and melting point etc. in large scale. However, Metal nanoparticles (MNPs) captured worthy importance for their applications in the chemical sensors, photo catalyst pharmaceutical products, chemical industry, medical imaging, medical diagnosis, medical treatment protocols, and drug-gene delivery (Magdalane et al., 2019; Thomas., 2019; Iravani., 2011). Moreover, MNPs explored unique properties, with improved catalytic activities compared to bulk material owing to their highly active facet morphologies (Du et al., 2017; Faisal et al., 2021; Kolhatkar et al., 2013).

Noble-metal (Au, Ag, Pt, Pd)-nanoparticles extensively employed now-a-days in the range of products from cosmetics to medical and pharmaceuticals (Al-Radadi and Al-Youbi, 2018a; Al-Radadi, 2018; Al-Radadi and Al-Youbi, 2018b; Al-Radadi., 2019; Al-Radadi and Adam., 2020). It’s because on account of their precious properties, high stability, biocompatibility, non-toxicity, precise aggregate activities towards tissues, and target cells (Yaqoob et al., 2020). In the recent years, increased population, wealth, and technology made researchers augmented attention on gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) as a consequence of their unique characteristic physicochemical, dispersion, size, shape, biological properties, and their latent therapeutic applications (Al-Radadi., 2022c; Al-Radadi., 2022d; Bai et al., 2020). The fine-tuned AuNPs possess desired physic-chemical properties, explored various effective biomedical applications in drug delivery, bio-imaging, bio-sensors (Daraee et al., 2016; Gurunathan et al., 2014; Sunderam et al., 2019), disease diagnosis, separation sciences, and in pharmaceuticals (Gerber et al., 2013).

The traditional construction of nanoparticles utilize toxic chemicals, time-consuming procedures, high costs, long-range processing, and liberate hazardous byproducts. It generated serious interest to develop eco-friendly processes. The inclination of customizing biological methods by means of microorganisms, and plants using various biotechnology tools were developed. Where, the research on synthesis of nanoparticles by green technology established great success than the physical and chemical techniques. Consequently, researchers, technologists, and chemists, are developing less peril, less energy consumptive (Gour and Jain., 2019), economical effective, and highly stable (Herlekar et al., 2014) chemical products. The eco-friendly approach of nanoparticles connects the nanotechnology with plant biotechnology. Whereas, we used Ephedra-extract for the green production of Ephedra-AuNPs obtain from Au+3. Ephedra is one of the oldest Chinese medicinal herb known as ma-huang belongs to Ephedraceae family, a non-flowering plant related to Gnetales (AtaeiAzimi., 2015; Caveney et al., 2001; Choudhary et al., 2021; Gul et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2019), and is being used for more than 5000 years (Abourashed et al., 2003). There are around 45 species of Ephedra are utilizing throughout the world (Ickert-Bond and Renner., 2016; Lee, 2011; Rydin et al., 2004), these are small shrubs having slight angles contained stripy branches with shrunken membranous leaves. It is generally employed in the treatment of headache, cough, chills, asthma, and bronchitis fever etc. Its volatile oil is antipyretic (Khattabi et al., 2022) and works against Asian influenza virus. The Ephedra is an imperative resource of active components contained pharmaceutical importance such as reducing sugars, cardiac glycosides, flavonoids (catechin equivalent 27.51 mg/g dry extract), phenolics (gallic acid equivalent 131.55 mg/g dry extract), cyclopropyl amino acids, cyanurates (Rustaiyan et al., 2011), tannins (gallic acid equivalent 64.91 mg /g dry extract), proanthocyanins, saponins, polyphenols and essential oils (ben Lamine et al., 2019; Elhadef et al., 2020; Mighri et al., 2019). Ephedra could also produce alkaloids, pseudoephedrine, ephedrine, and nor pseudoephedrine (Parsaeimehr et al., 2010). Explored its medicinal values as anti-diabetic, antimicrobial, high antioxidant activity, antipyretic, analgesic, diuretic, vascular, hypoglycemia, hypolipidemic (Al-Snafi, 2017; Maayan et al., 2017; Rashed., 2021) and anti-cancer effects. In the present study we have synthesized the AuNPs via green synthesis with Ephedra-extract. These nanoparticles are inert, highly selective, and resistant to bacteria. It was observed that the sensitivity and photo physical properties of the manufactured AuNPs were increased and promising antioxidant, anti-asthma, and antipyretic properties along with antibacterial and anti-fungal actions were accomplished (Scheme 1). These nanoparticles are inert, highly selective, and resistant to bacteria. It was observed that the sensitivity and photo physical properties of the manufactured AuNPs were increased and promising antioxidant, anti-asthma, and antipyretic properties in addition with antibacterial and anti-fungal actions were accomplished. The wide range of applications of nanoparticles to noble metals, particularly AuNPs, shows that this is an area worth continuing work (Al-Radadi, 2021a; Al-Radadi., 2022e; Klębowski et al., 2018) in the current global conditions (Scheme 1).

Green synthesis of (Au-NPs) Via Aqueous Extract of Ephedra: Characterization, Antioxidant, Antipyretic, Antiasthma and Antibiotic.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Preparation of Ephedra-extract and biosynthesis of Ephedra-AuNPs

A High class of Ephedra was purchased from a standard spices store and ethanol was acquired from Sigma Aldrich. Ephedra was washed for several times very well to remove the impurities and dust particles before use. Then 50 mL of distilled water followed by 20 mL of ethanol was added to 5 g of Ephedra, and mixed it well. To attain the composition of Ephedra-AuNPs, 4 mL of Ephedra-extract was added to 6 mL of Au. The solution mixture was stirred nearly an hour until the solution turns to the sapphire color. Afterward, the ions were reduced to due to the existence of antioxidants in the Ephedra-extract results in the formation of Ephedra-AuNPs which further confirmed by observing the characteristic ruby red color of the solution.

2.2 Optimization of reaction parameters

Varied factors were studied that influence the assembly of Au-NPs, for instance the quantities of Ephedra-extract, and solution, time duration of reaction, PH, and temperature to specify the optimization limits to the construction of Ephedra-AuNPs. A series of 1 mL to 4 mL of Ephedra-extract were added to a constant volume of 6 mL of solution discretely and kept the reactions at room temperature (25 °C) for about 3 h. to obtain the Ephedra-AuNPs. The influence of volume was studied by reacting diverse volumes (1 mL to 6 mL) of solution to a constant volume of 4 mL of Ephedra-extract individually at room temperature (25 °C) for about 3 h. The effect of reaction time was optimized by monitoring the UV–vis. absorption spectra of Ephedra-AuNPs reaction at the optimized volumes of Ephedra-extract and solution up to 180 min with a regular time intervals of 30 min at room temperature (25 °C). The consequences of reaction temperature was optimized using a set of reactions at various temperatures (15 °C, 20 °C, 25 °C and 30 °C) for about 3 h by means of above optimized reaction clauses to obtain the Ephedra-AuNPs. The pH optimization was assessed in the range of pH 2 to 7 in the individual reactions for 3 h at room temperature (25 °C) with optimum volumes of Ephedra-extract and solution. The resulting compounds were scrutinized by UV–visible spectra then finally corroborated by HRTEM and TEM analysis.

2.3 Characterization of synthesized Au-nanoparticles

Morphology, structure, and vibrational properties of biosynthesized Au-NPs were scrutinized by means of analytical techniques such as UV–Visible spectrophotometer (Cary 100, UV–Vis. spectrometer), Fourier transformed (FT) infrared spectroscopy (Thermo Nico-let 6700), Zeta potential, microscopic techniques [TEM (JEOL/JEM 2100 model, at 90 KV) and HRTEM], and X-ray methods of analysis [EDX (JEOL EDX model-JSM-5610 LV), XPS (PHI 5000 Versa probe II spectrometer), and XRD (XRD-7000, Japan model)] were performed.

2.4 Antioxidant assays

The action of AuNPs and Ephedra-extract at different concentrations in methanol as antioxidants was measured using ABTS method. Ascorbic acid was taken as the reference standard where the reaction was set in a dark room for 30 min. Absorbance of each reaction was recorded separately. The following equation is used to derive the antioxidant activity:

2.5 Antipyretic assays

The antipyretic activity of Ephedra-AuNPs, Ephedra-Gypsum and aspirin were studied. Eight groups of Wistar rats were divided as one control, one standard (aspirin), three Ephedra-Gypsum (8, 16, 32 g/kg doses), and three Ephedra-AuNPs (8, 16, 32 g/kg doses) groups. The animals were fasted for 12 h and the initial body temperature (Tb) was determined. Mice were injected with yeast suspension (1 mL/100 g) to raise its body temperature to induce fever. The testing compound was administered orally for 6 h followed by the equivalent dose of distilled water after the insertion of yeast solution; the rectal temperature was measured for 8 h at 8 body temperatures (TR) time points on each hour (1–8). The pharmacological kinetics were followed as.

The antipyretic study was measured according to the following equation:

Research Ethics: Animals were housed in the animal house of National Research Centre, Cairo, Egypt.

Animal experiments were intended and carried out according to the directions of institutional animal ethical committee.

2.6 Anti-asthmatic assays

Similar to the antipyretic study, The Wistar rats for anti-Asthmatic assays also separated into 8 groups (n = 12): one control, one dexamethasone, three Ephedra-gypsum (8, 16, 32 g/kg doses) and three Ephedra-AuNPs (8, 16, 32 µg/g/day doses) groups.

2.6.1 Asthmatic model preparation and drug treatment

The OVA induced model was employed to evaluate the anti-asthmatic examination. In this model the animals were intraperitoneally sensitized on 0, 7th and 14th days by OVA (100 mg/mL) in 0.9 % saline and make up with Al(OH)3 adjuvant to 1 mL. From 15th day the rats were allowed to inhale 2 % OVA or saline for about 30 min.

2.6.2 Measurement of latent period

The Latent period was observed where the symptoms such as scratching, wheezing, nodding respiration, cough were observed within 5 min after the final exposure to OVA aerosol.

2.6.3 White blood cell and eosinophils analysis

Quite a few white blood cells (WBC) and eosinophils (EOS) were examined where; the anti-coagulated blood was gathered utilizing a heparin-coated tube through a canella embedded into the aorta abdominals.

2.6.4 Measurement of wet and dry weight of lungs

The alteration of wet/dry (W/D) weight proportion of lung resulted commencing the injury of unblemished rodents lungs. The water content in lungs of samples was appraised by a wet/dry weight method. The right lungs were detached and weighed. In an aluminum foil (pre-weighed), the tissue sample was enfolded, dried at 100 °C for four to five days until it gets a constant dry weight, then reweighed (dry weight).

2.7 Antimicrobial activity

2.7.1 Agar-well diffusion method

The antibacterial action of Ephedra-AuNPs was executed by agar well dispersion strategy. A 5 mm range well within the petri-plate was made and brooded 72 h at room temperature for fungal culture and 24 h at 37 °C for bacterial growth. A movement was estimated in the zone of hindrance by ascertaining the breadth in mm. The bacterial strains under investigation were inoculated by spreader and four different concentrations of test samples were appended to the well. There was no inhibition activity occurred against microbial cultures when the test samples were immersed in DMSO indicates the negative effect on the growth of the microbial species.

The microbial strains were obtained from National Research Centre, Cairo, Egypt.

2.7.2 The antibacterial activity

Antibacterial strength of Ephedra-extract and Ephedra-AuNPs was appraised using gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Listeria moncytogenes and gram-negative Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella typhimurium bacterial species.

2.7.3 Antifungal activity

The Ephedra-extract and Ephedra-AuNPs antifungal activity was estimated using three fungal strains which include Candida albicans, Aspergillus nigra, and A. flavus.

3 Results

3.1 Effect of reaction parameters on the construction of Ephedra-AuNPs

The Ephedra-AuNPs were prepared in miscellaneous conditions such as diverse volumes of Ephedra-extract and solution, a range of pH conditions, at diverse temperatures, and time periods. However, the ruby-red color (final change in color) to the solution determine the formation of Ephedra-AuNPs which was monitored by UV–vis. and TEM studies.

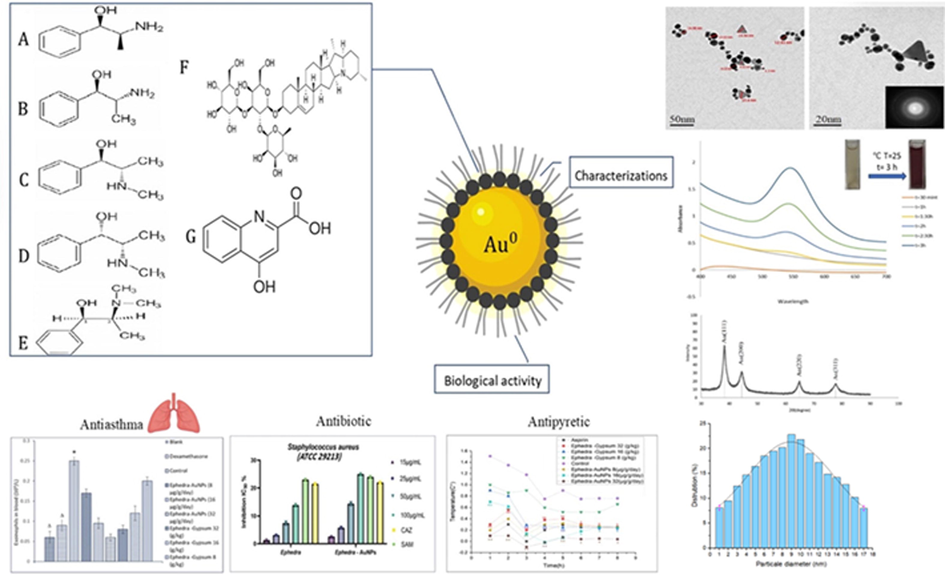

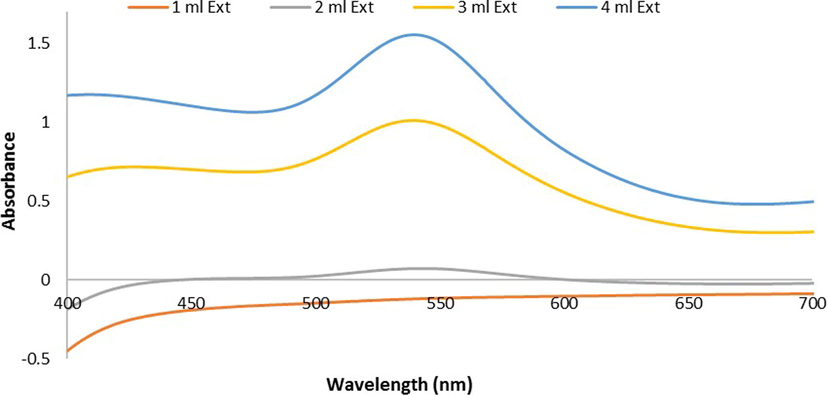

3.1.1 Effect of extract volume

The Ephedra-extract of 1 mL to 4 mL with 6 mL of

reactions was scrutinized for 3 h at RT. The UV–vis. spectra recorded that showed the SPR peak at 549 nm enhanced and become sharper with increase in 1 mL to 4 mL volume of Ephedra-extract (Fig. 1).

U.V-Vis. spectra of Ephedra -AuNPs at different volumes of Ephedra extract (1–4 mL) with 6 mL of (HAuCl4·3H2O)(10−3)M at room temperature 25 °C and after 3 h.

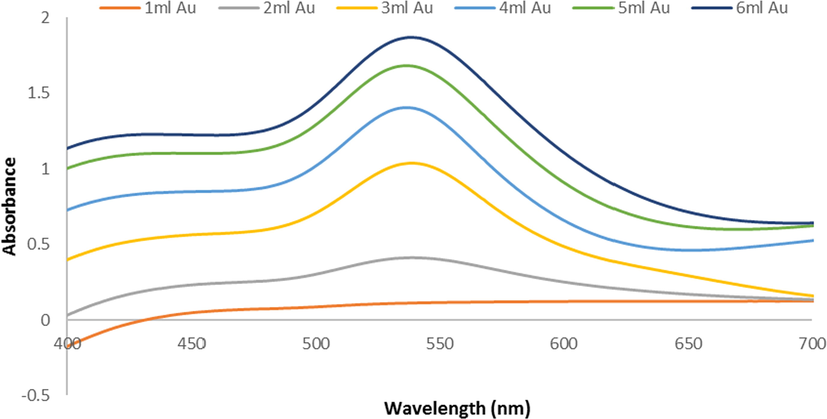

3.1.2 Effect of volume

The

solution volumes ranging from 1 mL to 6 mL were used to react with 4 mL of Ephedra-extract at RT for 3 h. A low intense peak at 540 nm in the UV–vis. analysis observed which shifted to 549 nm upon increasing the

volume from 1 mL to 6 mL. (Fig. 2).

U.V-Vis spectra of Ephedra -AuNPs at different volumes of (1– 6 mL)(HAuCl4·3H2O)(10−3)M with 4 mL of Ephedra extract at room temperature 25 °C and after 3 h.

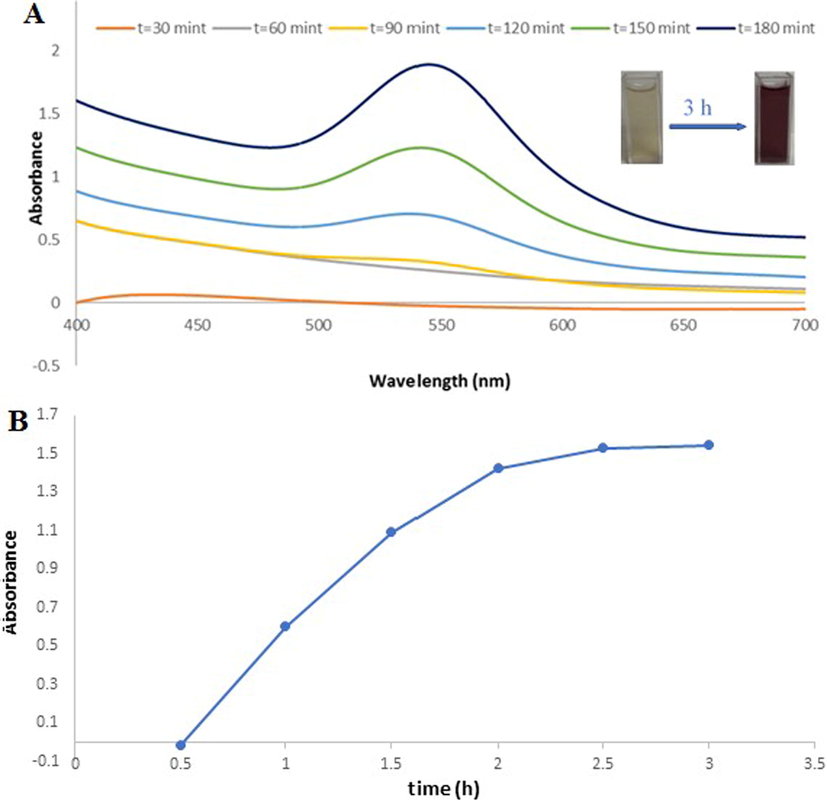

3.1.3 The effect of reaction time

A series of 4 mL Ephedra-extract and 6 mL

solution at room temperature for 3 h reactions were conducted with a regular time intervals of 30 min. and the results were observed in the UV–vis. absorption spectra. It showed that a prominent SPR peak started forming at 540 nm after 90 min. of the reaction and increases its intensity form a sharp peak upon increasing the reaction time up to 3 h (Fig. 3 (A)). Moreover, the absorbance vs reaction time also plotted in order to understand the extension of reaction (Fig. 3 (B)).

(A)U.V-Vis spectra of Ephedra -AuNPs of 6 mL (HAuCl4·3H2O) (10−3)M with 4 mL of Ephedra extract at different time (30–180 min) at 25 °C, (B) Intensity variant within U.V-Vis. spectra of AuNPs as function of time.(0.5–3 h).

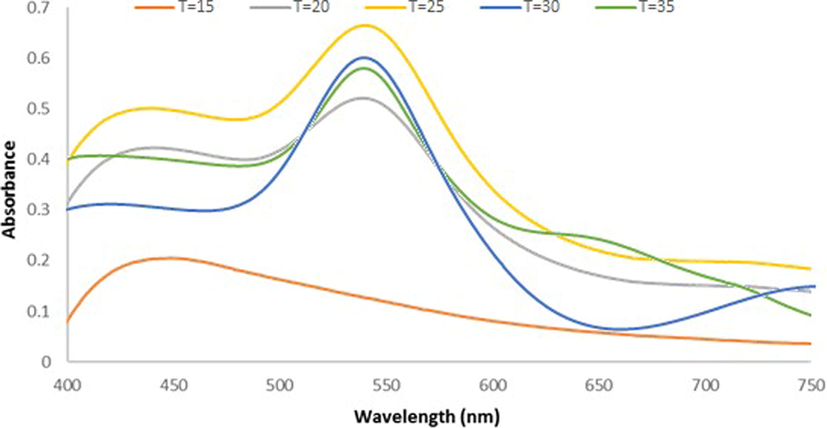

3.1.4 The effect of temperature

The Ephedra-AuNPs were synthesized separately at different temperatures i.e at15 °C, 20 °C, and 25 °C 30 °C, 35 °C and observed the UV–vis. absorption spectra. The reaction at 15 °C obtained a broad peak at 440 nm which upon increasing the reaction temperature started forming a prominent sharp peak at 540 nm at 20 °C that further increases its intensity at 25 °C. When increasing the temperatures again up to 30 °C and 35 °C the Absorbance of the peak decreased Comparing with the previous results, suggested the optimum reaction temperature at 25 °C (Fig. 4).

U.V-vis. spectra for Ephedra -AuNPs of 6 mL (HAuCl4·3H2O) (10−3)M with 4 mL of Ephedra extract at different temperatures (15–35 °C), after 3 h.

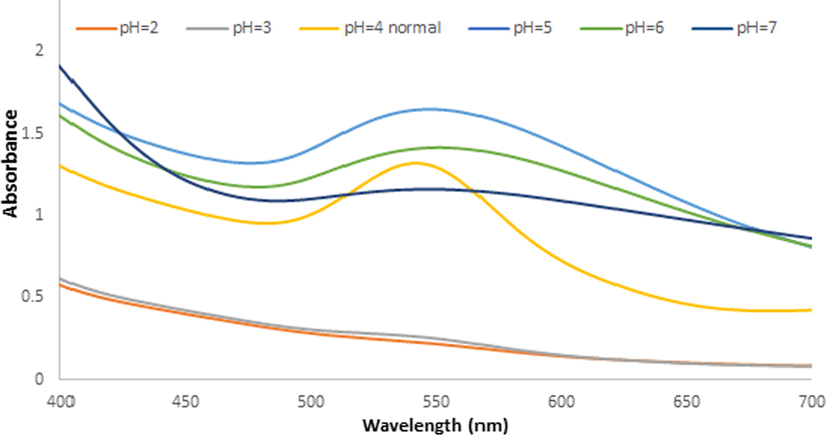

3.1.5 The effect of pH

The Ephedra-AuNPs reaction was performed in the range of pH levels 1–7 along with the above optimized conditions with regular UV–vis. monitoring. The 540 nm peak was observed, where the pH from 1 to 4 the peak intensity was increased. At pH 5 a broad peak formed and continued broadening up to pH 7 along with the decrease in the peak intensity was obtained (Fig. 5). Where, the optimum pH is found to be at pH 4 and is corroborated by TEM images which further confirmed their small size and homogeneous shape as well (Fig. 8 (A)).

U.V-vis. spectra for Ephedra -AuNPs of 6 mL (HAuCl4·3H2O) (10−3)M with 4 mL of Ephedra extract at different PH(2–7) at 5 °C after 3 h.

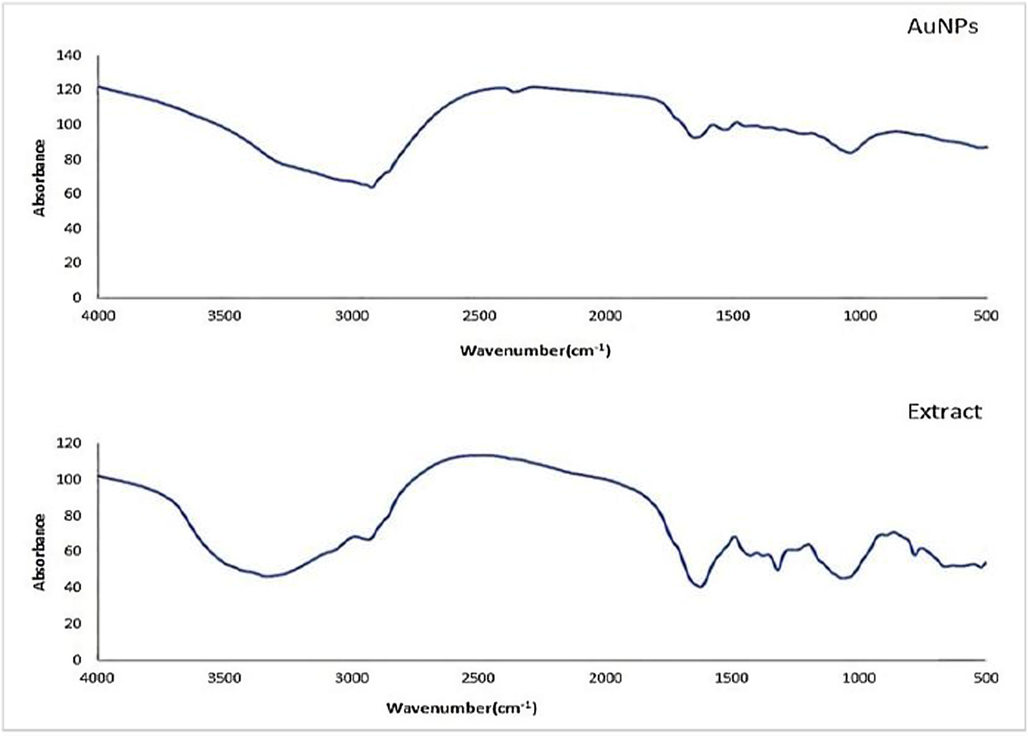

3.2 Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

The FTIR of Ephedra-extract and Ephedra-AuNPs showed a broad-band between 3000 and 3500 cm−1, due to the stretching vibrations of hydrogen bonded (N—H), (O—H), and aromatic C—H groups. The absorption bands at 2920 cm−1, 1610 cm−1, and 1080 cm−1 are due to aliphatic (C—H), (C⚌C), and (C—O) vibrations respectively. The absorption recorded at

are due to the presence of (C⚌N) (unsaturated amine) stretching vibration. The two weak bands at 825

and 600

are due to the aromatic compound in the extract (Fig. 6).

X-ray diffraction pattern of Ephedra extract and Ephedra -AuNPs.

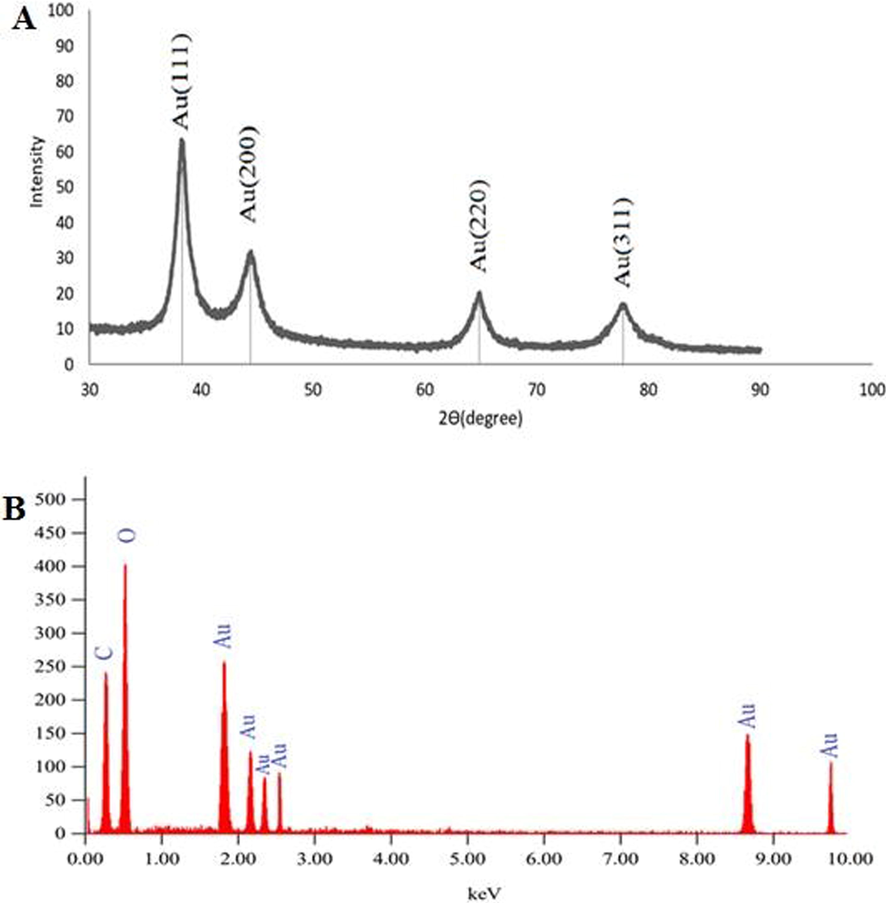

3.3 X-ray diffraction analysis

The Ephedra-AuNPs powder XRD explored four peaks at 38.1°, 44.51°, 64.61°, and 77.82° diffraction angles. The powder pattern and crystallinity were compared, which is in good agreement with the reported green biosynthetic AuNPs (Fig. 7 (A)).

(A)X-ray diffraction pattern of Ephedra extract and Ephedra –AuNPs, (B) EDX image of Ephedra extract mediated AuNPs synthesized.

3.4 EDX analysis

The EDX analysis carried out on dried Ephedra-AuNPs. The characteristic 2 keV signal for Au with other weak carbon and oxygen signals confirmed the presence of these elements (Fig. 7 (B)).

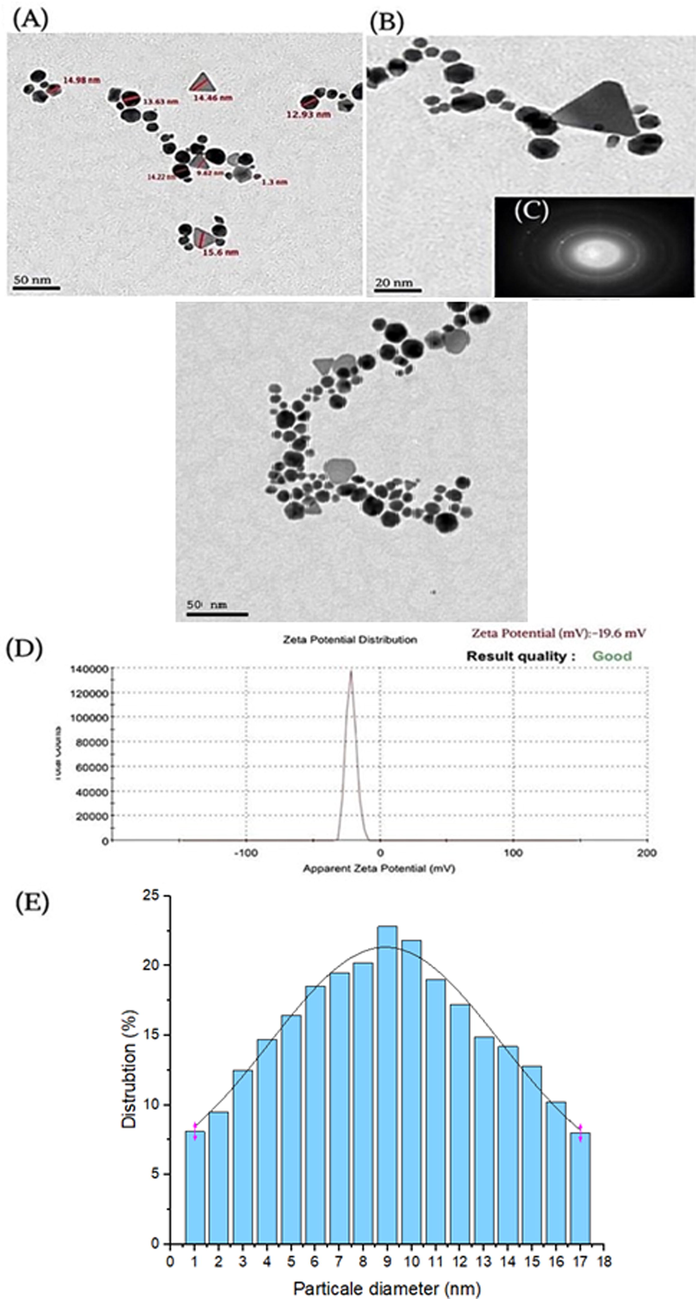

3.5 HRTEM analysis:

The HRTEM (50 nm scale) analysis and size distribution histogram (20 nm scale) and HAADF-STEM studies of the Ephedra-AuNPs confirmed the presence of 1.3 nm to 15.6 nm spherical and triangle morphologies (Fig. 8 (A-C)). The constructed AuNPs obtained −19.6 mV of average zeta potential in a single sharp peak further explored its size and stability, and are not agglomerated (Fig. 8 (D)). The current outcomes are carefully compared, and are consistent to the former reports of AuNPs.

TEM (A), HRTEM images (B), HAAD-STEM images (C), Zeta potential (D) and corresponding size distribution graph of Ephedra -AuNPs (E).

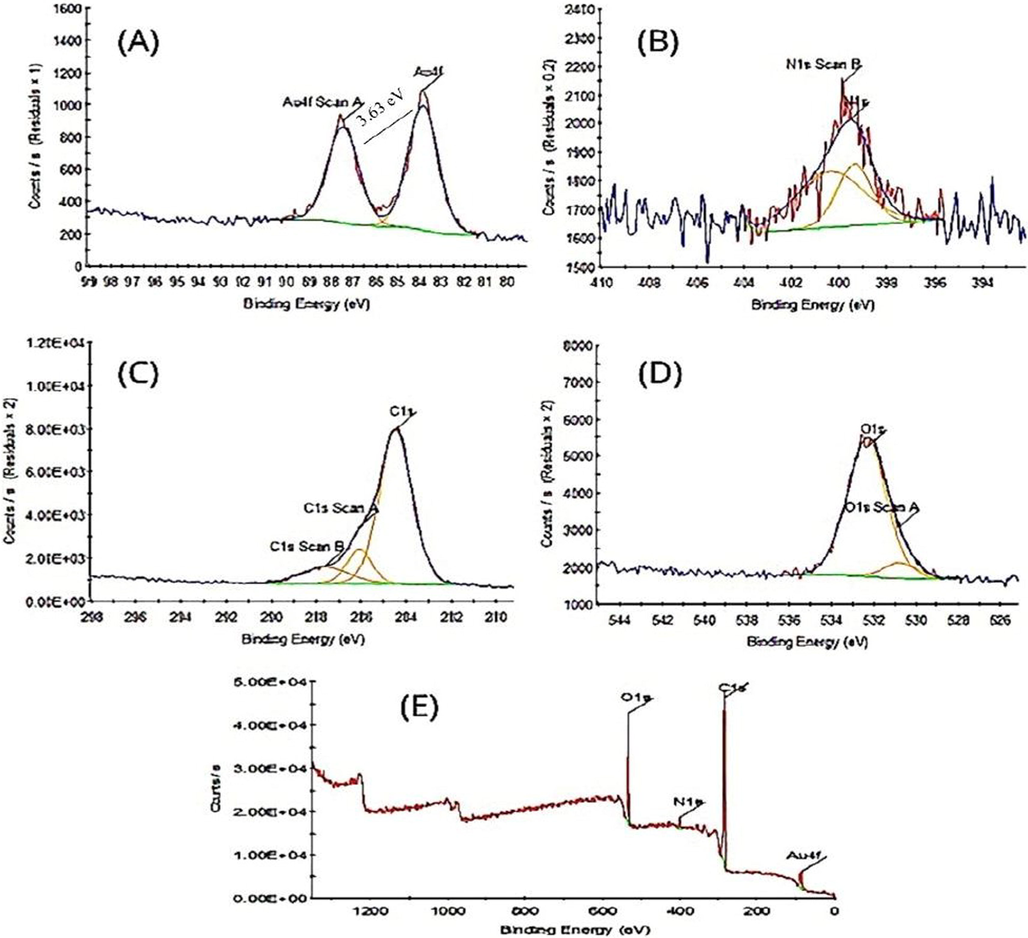

3.6 XPS analysis

The XPS of Ephedra-AuNPs revealed two strong peaks at 83.85 eV and 87.47 eV corresponding to

7/2 and

5/2 with a band gap of 3.63 eV. The intensity of 83.85 eV (4f7/2) peak is higher than the other peak and owing to the domination of metallic gold (

0) than other elements (Fig. 9 (A)) and is good agreement with the previous studies. Where, carbon and oxygen elements were also analyzed (Fig. 9 (B-E)).

XPS analysis showing survey scan (A), (B) N1s, (C) C1s (D) O1s (E) Ephedra -AuNPs.

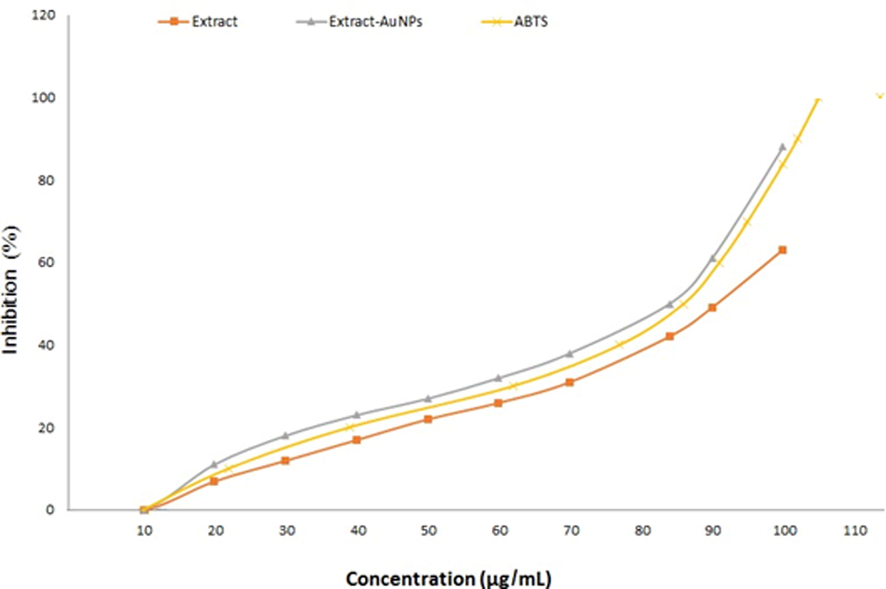

3.7 Antioxidant activity of Au-NPs by ABTS

The compounds Ephedra-extract, ascorbic acid, and Ephedra-AuNPs antioxidant activity was appraised by ABTS assays (Fig. 10) which showed

,

, and

of

values respectively. In fact the radical scavenging action of standard and Ephedra-extract is comparable but when the extract bound to form AuNPs explored improved activity. It was assumed to be the structure, polarity and solubility properties might improve the antioxidant activity in the Ephedra-AuNPs.

The antioxidant activity of the ABTS, Ephedra extract, and Ephedra- AuNPs.

3.8 Antipyretic activity of Ephedra-AuNPs

Oral treatment of Ephdera-AuNPs on various concentrations at doses of

and Ephedra-Gypsum at

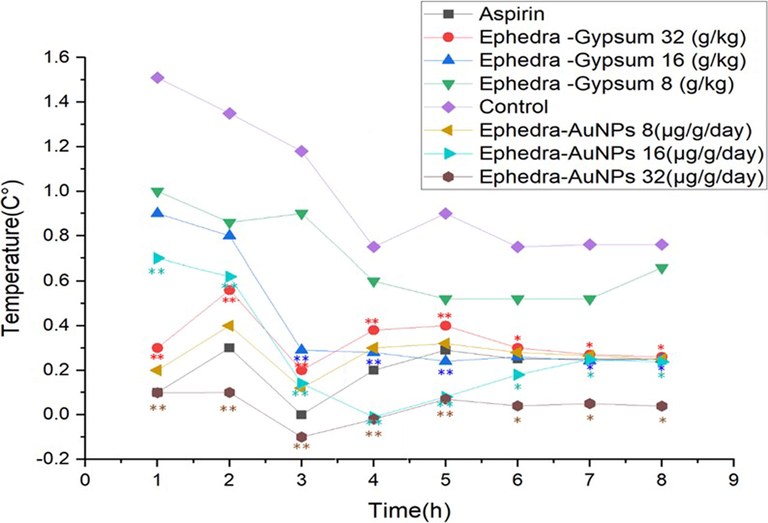

doses were examined (Table 1). A significantly reduced temperature was observed depending on the dose. The antipyretic effect of 32 µg/g/day of Ephdera-AuNPs started from the first hour (p < 0.01) and lasted to 8 h (p < 0.05), while for Ephedra-Gypsum started at 32 g/kg from the first hour (p < 0.01) and lasted to 6 h (p < 0.05). But the effect of 16 µg/g/day of Ephedra-AuNPs started at 3 h (p < 0.01) and lasted for 7 h where, the Ephedra-Gypsum at 16 g/kg, started at 3 h and continued for 5 h (p < 0.05). The effect of the 8 µg/g/day dose of Ephedra-AuNPs started at second hour (p < 0.01) and the effect persisted for 5 h (p < 0.05). Ephedra did not show a significant decrease in temperature. Oral treatment with Ephdera-AuNPs reduced fever index by 61.5 %, 79 % and 83.3 % at doses of 8, 16, and 32 mcg/g/day respectively, whereas, Ephedra-Gypsum reduced it by 63 %, 54 %, and 22 % at 8, 16, and 32 g/kg doses respectively. Perhaps Aspirin (standard drug) reduce the fever index by 80 %. The results suggest the significant antipyretic effect of Ephedra-AuNPs than the standard compound (Fig 0.11). Notes: P*<0.01, compared with the control group.

Treatment groups

n

Dose

Latent period (s)

Increasing (%)

Ephedra-AuNPs

12

8 (µg/g/day)

138 ± 11

36.6

Ephedra-AuNPs

12

16(µg/g/day)

169 ± 15

70.1

Ephedra-AuNPs

12

32(µg/g/day)

211 ± 10

106.4

Ephedra-Gypsum

12

8 (g/kg)

127 ± 20

26.3

Ephedra-Gypsum

12

16 (g/kg)

160 ± 24*

58.9

Ephedra-Gypsum

12

32 (g/kg)

101 ± 33*

192

Control

12

–

101 ± 34

–

Dexamethasone

12

0.75

208 ± 24*

105.9

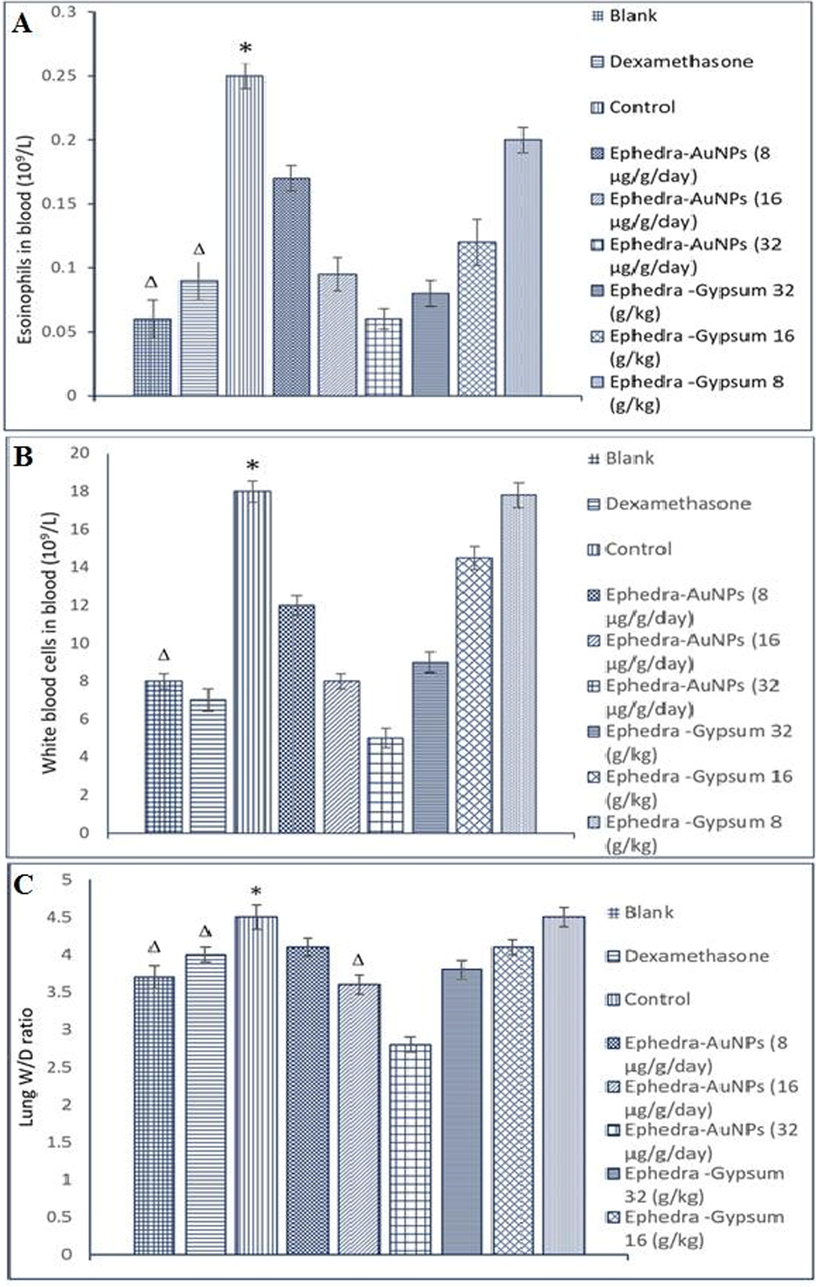

3.9 Antiasthma activity of Ephedra-AuNPs

The Ephedra-AuNPs at doses of

and Ephedra-Gypsum at

doses achieved prolonged latent period by an average of 36.6 %, 70.1 %, and 106.4 %, and Ephedra-Gypsum at 63 %, 54 %, and 22 %, respectively. It is apparent that dexamethasone (

) extended the latent time (P < 0.01) when matched with the control group (Fig. 12).

Antipyretic Activity of Ephedra-AuNPs.Notes: Each point represents the mean ± standard deviation of 6 animals; P∗<0.05, P∗∗<0.01, compared with the control group.

(A) Effects of the of Ephedra-AuNPs on EOS Counts in Asthmatic Rats, (B) Effects of the Ephedra-AuNPs on WBC Counts in Asthmatic Rats, (C) Effects of the Ephedra-Gypsum Extracts on W/D Weight Ratio of Lung in Asthmatic Rats Notes: P*<0.01, compared with the blank group, PΔ < 0.01, compared with the control group.

3.10 Antimicrobial study

3.10.1 The antibacterial activity

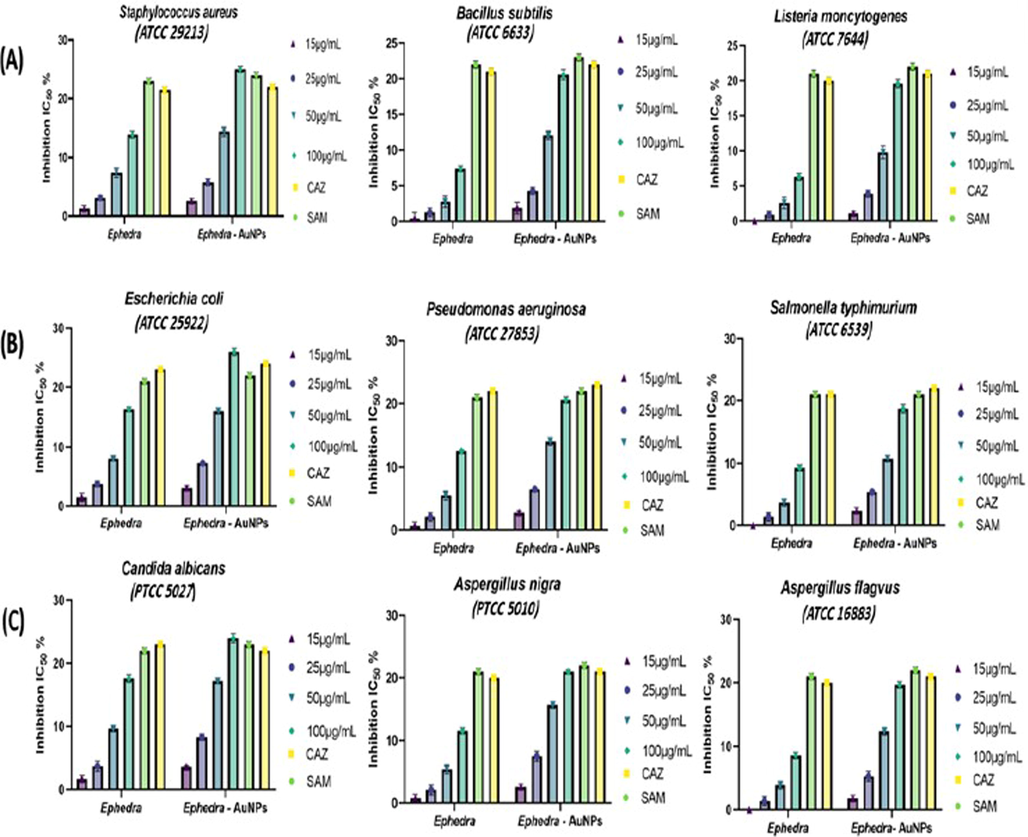

The Ephedra-extract and Ephedra-AuNPs were appended in 15, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL using traditional nutrient agar process and were examined against the species Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213), Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633), Listeria moncytogenes (ATCC 7644), Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853) and Salmonella typhimurium (ATCC 6539) of bacteria. Ceftazidime (CAZ) and Ampicillin-Sulbactam (SAM) were used as Standard Antibiotic (Positive control) and control (Negative control) (Fig. 13). The Ephedra-extract and Ephedra-AuNPs made great contact and considerable activity was displayed (Table 2). (a) The diameter (mm) is included in the measured zone of inhibition. (b) Standard Antibiotic (Positive control) Ceftazidime (CAZ) and Ampicillin-Sulbactam (SAM). (c) Control (Negative control).

(A) Antibacterial Gram-Positive bacteria activity of Ephedra extract and Ephedra-AuNPs, (B) Antibacterial Gram-negative bacteria activity of Ephedra extract and Ephedra-AuNPs and (C) Antifungal activity of Ephedra extract and Ephedra-AuNPs.

pathogenic microbial strains

Microorganisms Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213)

Concentration μg/mL

Ephedra (mma)

Ephedra–AuNPs (mma)

Gram-Positive bacteria

15 μg/mL

1.3 ± 0.5

2.6 ± 0.4

25 μg/mL

3.1 ± 0.4

5.8 ± 0.6

50 μg/mL

7.4 ± 0.8

14.4 ± 0.8

100 μg/mL

13.9 ± 0.6

25 ± 0.5

Standardb SAM Standardb CAZ

23 ± 0.5 21 ± 0.5

24 ± 0.5 22 ± 05

Controlc

0.0 ± 0.0

0.0 ± 0.0

Bacillus subtilis (ATCC 6633)

15 μg/mL

0.4 ± 0.9

1.9 ± 0.8

25 μg/mL

1.3 ± 0.6

4.3 ± 0.5

50 μg/mL

2.8 ± 0.8

12.1 ± 0.6

100 μg/mL

7.4 ± 0.4

20.6 ± 0.7

Standardb SAM Standardb CAZ

22 ± 0.5 21 ± 0.5

23 ± 0.5 22 ± 0.5

Controlc

0.0 ± 0.0

0.0 ± 0.0

Listeria moncytogenes (ATCC 23074)

15 μg/mL

0.0 ± 0.0

1.1 ± 0.3

25 μg/mL

0.9 ± 0.5

3.9 ± 0.5

50 μg/mL

2.6 ± 0.8

9.8 ± 0.9

100 μg/mL

6.3 ± 0.5

19.6 ± 0.6

Standardb SAM Standardb CAZ

21 ± 0.5 20 ± 0.5

22 ± 0.5 21 ± 0.5

Controlc

0.0 ± 0.0

0.0 ± 0.0

Gram-negative bacteria

Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922)

15 μg/mL

1.5 ± 0.7

3.1 ± 0.4

25 μg/mL

3.8 ± 0.5

7.3 ± 0.2

50 μg/mL

8.1 ± 0.3

16 ± 0.5

100 μg/mL

16.3 ± 0.4

26 ± 0.6

Standardb SAM Standardb CAZ

21 ± 0.5 23 ± 0.5

22 ± 0.5 24 ± 0.5

Controlc

0.0 ± 0.0

0.0 ± 0.0

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 27853)

15 μg/mL

0.7 ± 0.6

2.8 ± 0.3

25 μg/mL

2.1 ± 0.7

6.5 ± 0.2

50 μg/mL

5.5 ± 0.7

14.1 ± 0.6

100 μg/mL

12.6 ± 0.2

20.6 ± 0.5

Standardb SAM Standardb CAZ

21 ± 0.5 22 ± 0.5

22 ± 0.5 23 ± 0.5

Controlc

0.0 ± 0.0

0.0 ± 0.0

Salmonella typhimurium (ATCC 6539)

15 μg/mL

0.0 ± 0.0

2.4 ± 0.5

25 μg/mL

1.4 ± 0.7

5.4 ± 0.3

50 μg/mL

3.7 ± 0.6

10.8 ± 0.5

100 μg/mL

9.3 ± 0.5

18.7 ± 0.5

Standardb SAM Standardb CAZ

20 ± 0.5 21 ± 0.5

21 ± 0.5 22 ± 0.5

Controlc

0.0 ± 0.0

0.0 ± 0.0

Fungai

Candida albicans (ATCC 10,231

15 μg/mL

1.7 ± 0.6

3.6 ± 0.2

25 μg/mL

3.7 ± 0.8

8.3 ± 0.5

50 μg/mL

9.7 ± 0.5

17.2 ± 0.4

100 μg/mL

17.6 ± 0.6

24 ± 0.7

Standardb SAM Standardb CAZ

22 ± 0.5 21 ± 0.5

23 ± 0.5 22 ± 0.5

Controlc

0.0 ± 0.0

0.0 ± 0.0

Aspergillus nigra (ATCC 16620)

15 μg/mL

0.8 ± 0.6

2.9 ± 0.4

25 μg/mL

2.1 ± 0.8

7.5 ± 0.8

50 μg/mL

5.4 ± 0.7

15.7 ± 0.5

100 μg/mL

11.6 ± 0.5

21 ± 0.3

Standardb SAM Standardb CAZ

21 ± 0.5

22 ± 0.5

20 ± 0.5

21 ± 0.5

Controlc

0.0 ± 0.0

0.0 ± 0.0

Aspergillus flavus (ATCC 16883)

15 μg/mL

0.0 ± 0.0

1.8 ± 0.5

25 μg/mL

1.4 ± 0.7

5.3 ± 0.8

50 μg/mL

3.9 ± 0.6

12.4 ± 0.6

100 μg/mL

8.6 ± 0.5

19.7 ± 0.5

Standardb SAM Standardb CAZ

21 ± 0.5

22 ± 0.5

20 ± 0.5

21 ± 0.5

Controlc

0.0 ± 0.0

0.0 ± 0.0

3.10.2 Antifungal activity

The Ephedra-extract was severely lethal towards Candida albicans (17.6 ± 0.6) and slightest towards Aspergillus nigra (8.6 ± 0.5) while Ephedra-AuNPs showed extreme activity against Candida albicans (ATCC 10231) was (24 ± 0.7) and least active to Aspergillus nigra (ATCC 16620)(19.7 ± 0.5) (Table 2). The sensitivity of Ephedra-extract and Ephedra-AuNPs against the studied fungal strains is comparable to the SAM, CAZ standard compounds (Fig. 13).

4 Discussions

The Ephedra-AuNPs were constructed from Ephedra-extract and characterized by numerous spectroscopic techniques. The resultant Ephedra-AuNPs used to investigate the biomedical applications. Various reaction parameters of Ephedra-AuNPs synthesis were optimized for instance Ephedra-extract quantity, volume of metal ion , pH, temperature and the reaction time (Al-Radadi., 2022c; Narband et al., 2009; Philip, 2008). Our investigation suggested that for the construction of Ephedra-AuNPs, the required optimum volume of Ephedra-extract is 4 mL and the best suitable volume is 6 mL respectively. It was corroborated using UV–vis. and HRTEM studies where upon increasing the volume of extract from 1 mL to 4 mL the low intense 549 nm peak intensity increased gradually. Similarly the volume fom 1–6 mL also showed intensity augmentation at 549 nm peaks in UV–vis (Al-Radadi., 2021a; Kumar and Gulia., 2021; Nadaf and Kanase., 2019). The visible spectra of Ephedra-AuNPs explored the distinctive peak at max = 549 nm which is a characteristic of metallic nanoscale gold, correlated to the formation of AuNPs (He et al., 2007; Suman et al., 2014; Yuan et al., 2017). It is supported by exploring TEM images where, the formed Ephedra-AuNPs attain 1.3 nm to 15.6 nm respective sizes (Fig. 8 (A)) and are well dispersed without aggregation (Fig. 8 (B)). The HAADF-STEM images (Fig. 8-C) of the Ephedra-AuNPs reveal the ‘Au’ in bright ring structures (Al-Radadi., 2022d). The AuNPs recognized spherical and triangular-shaped, presented poly-disperse characters results a wide SPR peak in the spectra. (Al-Radadi., 2021b; Sunayana et al., 2020; Vijaya Kumar et al., 2018). The AuNPs synthesis reactions performed for different reaction times for 3 h with 4 mL of Ephedra-extract, and 6 mL of solution by a 30 min. time gap between the reactions. The absorbance vs reaction time plot results observed in UV–vis. suggested that, the absorption at 30 min = -0.0191 nm and the reaction was rapid. Therefore, the SPR peaks intensity raised sharply for 2 h until the absorption half-time was 1.0913 cm−1. Then the AuNPs formation reaction slowed and become steady up to 3 h with a sluggish increase in the peak intensity (Fig. 3 (B)) due to the intrusion of already formed Ephedra-AuNPs (Islam et al., 2019; Mahdi et al., 2021; Sarfraz and Khan., 2021). The Ephedra-AuNPs construction might takes 3 h reaction time for its completion. Further the nanoparticles synthesis was examined at different temperatures, 15 °C, 20 °C, 25 °C, 30 °C and 35 °C. The reaction when conducted at 15 °C a broad peak at 440 nm was obtained but upon increasing the reaction temperature to 20 °C and 25 °C a new peak at 540 nm was emerged. It is implicated that there is no reaction happening at 15 °C and doesn’t form any characteristic AuNPs peak. However upon increasing the reaction temperature to 20 °C the peak at 540 nm related to Ephedra-AuNPs product occurred and the peak intensity increased with increase in the reaction temperature to 25 °C. Consequently 25 °C presumed to be the suitable reaction temperature for the development of Ephedra-AuNPs. Moreover, the optimum pH of the solution used for the AuNPs synthesis was also analyzed by probing various reactions at different pH conditions. The pH range was 2–7 where the results suggest that there was no reaction happened when the reaction maintained up to pH 3. Interestingly at pH 4 the product exhibits a prominent characteristic peak at 540 nm indicating the suitability of the pH level for the product formation. Furthermore, when the pH level increases to 5–7 the UV–vis. spectra showed broadening of the peaks along with red shift in the peak position (λmax = 562), and the intensity of the peaks decreased from pH 5–7 (Castro and Vassend., 2018; El-Naggar et al., 2016). The decreased intensity specify the inactivity of the reactions whereas the peak broadening might be due to the hindrance of the reaction molecules by hydrogen bonding interactions with the functional groups present in the constituents of Ephedra-extract.

The FTIR spectrum makes clear the interactions of AuNPs with Ephedra-extract and the formation of Ephedra-AuNPs. It was known that numerous antioxidants exist in the nanoparticles. Where, the regeneration of similar or slight to moderately shifted functional group peaks of Ephedra-extract bio-molecules in the FTIR of the product confirms the desired Ephedra-AuNPs formation. The reduction of the gold ions substantiated by particularly observing the fingerprint region and hydrogen bonded (–OH) peaks in the IR of Ephedra-AuNPs. The stretching vibration band at 1310 occurring in both the compounds correlated to the (C—O) stretching vibration point out the presence of ‘N’ atom that coordinated with the metal gold Au0 resulting AuNPs. The 3000–3500 cm−1 broad band indicates hydrogen bonding interactions results due to the presence of OH, NH, and aromatic C—H functions in the compounds (Awwad and Albiss, 2015; Fazeli-Nasab et al., 2021; Nasar et al., 2022,Nasar et al., 2019). The peak at 1627 cm−1 reflects (C⚌N) functional group. Where, there is a hump at 1670 cm−1 could be due to C⚌O peak. The existence of these peaks proved that the nanoparticles were covered by plant secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, terpenoids, glycosides, Ephedrine derivatives (such as methyl ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, nor pseudoephedrine), tannins, with functional groups such as phenols, ketone, aldehyde, and carboxylic acids. The crystallinity of the produced AuNPs was assessed using XRD powder pattern (Khoshnamvand et al., 2020). The presence of sharp and moderately intense peaks in the powder XRD determined that the Ephedra-AuNPs attain crystalline nature might be owing to the existence of intermolecular interactions of the constituent molecules of Ephedra-extract. Particularly, the band of (1 1 1) plane was adequately strong in contrast to the remaining planes, representing the primary orientation of the constructed Ephedra-AuNPs (Khatami et al., 2018). The surface polarity of the AuNPs was approximated by Zeta potential that determine the nanoparticles colloidal stability (Al-Radadi, 2021b).

The presence of elemental composition was identified by EDX analysis. It substantiate the presence of Au, Carbon and Oxygen spots which further confirm the coordination of organic compounds (phytochemicals) with that of the metal atoms to result the biosynthesized AuNPs (Ekennia et al., 2021). Whereas, XPS survey was displayed sharp peaks for Au0 (85.27 eV), nitrogen (400.29 eV), oxygen (533.07 eV), and carbon (285.48 eV) with inset spectra of Au 4f7/2 and 4f5/2 (Barras et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2007; Riabinina et al., 2011). The peaks appeared for the elements due to the coated bio-molecules of Ephedra contain the elements carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, on the surface of the Au0 particles.

The prime variables engaged in biological activities are free radicals and the reactive oxygen created during anti pathogenic activities. The presence of biologically active oxygen functions (OH or COOH) or other radical active functions in the Ephedra-extract possibly create free radicals that showed comparable anti biological activity (Ilyasov et al., 2018; Re et al., 1999). In fact Ephedra-extract and ascorbic acid showed slight difference in biological actions irrespective of their structure and physical properties. (Lee et al., 2006; Proestos et al., 2013). But the Ephedra-AuNPs determined improved antioxidant activity (Fig. 11) (Al-Nemi et al., 2022; Pu et al., 2019).

The dose dependent antipyretic activity of Ephedra-AuNPs, and Ephedra-Gypsum were studied on Wister rats where Aspirin was used as standard antipyretic drug. A significantly reduced temperature was observed with Ephedra-AuNPs at doses of and compared with of Ephedra-Gypsum. Among the oral doses given, the dose is showed considerable activity up to 83.3 % where the Ephedra-Gypsum exhibited a maximum of 63 % antipyretic activity. Whereas Aspirin was used as a standard drug obtained 84 % antipyretic activity. When compared the two components (Ephedra-AuNPs and Ephedra-Gypsum) the quantity of Ephedra-AuNPs is very less and activity is more efficient than Ephedra-Gypsum (Fig. 11) (Kakiuchi et al., 2011; Tiss et al., 2020). These results proved the quantitative and qualitative activities of synthesized NPs which explored the comparable antipyretic activity with that of Aspirin. The trachea and lungs are the major constituents of the respiratory system which could be influenced by environmental issues. Consequently, the Ephedra-AuNPs further employed for the antiasthma activity study. Ephedra-AuNPs noticeably reduced the yeast-induced febrile response comprise the effect of reducing serum WBC and EOS levels, W/D lung weight ratio, and extending the OVA-induced latent time in the anti-asthma test (Fig. 12) (Sarwar et al., 2019). The Ephedra-AuNPs at a dose of 16, and 32 µg/g/day and the Ephedra-Gypsum at 32 g/kg inhibited the level of EOS and WBC in the blood with a higher percentage than dexamethasone. Also, the Ephedra-AuNPs was given in three doses 8, 16, and 32 µg/g/day to reduce the lung weight which too showed greater efficiency than dexamethasone. The results obtained are due to the size dependent nano-properties of the drug delivery system, and its huge surface area. These studies illustrated the efficiency of synthesized Ephedra-AuNPs as an anti-asthmatic by means of reducing EOS and WBC in the blood, and W/D ratio of lungs and extending the latent period. The antimicrobial activity of Ephedra-AuNPs against bacteria and fungi was evaluated. Ephedra-extract showed a clear inhibition of bacteria at 100 μg/mL (Sunayana et al., 2020), the extract was inhibiting for Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 29213) equal (13.9 ± 0.6) while the inhibition of Ephedra-AuNPs (25 ± 0.5) and the Standard Medicines SAM, CAZ inhibition was (24 ± 0.5, 22 ± 05) (Table 2). Ephedra-extract contains large amounts of natural substances, phenols, flavonoids, alkaloids that have health-promoting benefits for Human (Zang et al., 2013), AuNPs as a good conductor of drugs led to raise the level of inhibition to a higher level than the standards Ephedra-AuNPs with antibacterial potential gave great results better than the standard drug for Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) at (26 ± 0.6), the standards SAM, CAZ was (22 ± 0.5,24 ± 0.5) (Boussena et al., 2022; El-Zayat et al., 2021), and this confirms that the particles of Ephedra-AuNPs were small Size, spherical, and not clumped. The antifungal activity of Ephedra-extract and Ephedra-AuNPs showed effective results for the three series of fungi (Ożarowski et al., 2022), the inhibition of Candida albicans(ATCC 10231) was the best inhibition, the extract inhibit was (17.6 ± 0.6), Ephedra-AuNPs gave inhibition was (24 ± 0.7) and this result was higher than that of SAM and CAZ (Table 2) (Fig. 13). Nanoparticles prepared by green synthesis with Ephedra-extract explored the above anti pathogen activities owing to the phytochemical compounds which exert as capping, reducing, and stabilizers.

5 Future perspectives

The present global anti-microbial medications need to be repurposed and should go through various research clinical trials using diverse reported components which explored promising results. Nano-materials are deemed to be a feasible alternative therapy for several microbial issues. Moreover, the production of nanoparticles preferred for its environment friendly synthesis using plant materials, simple processing and their potential biological applications. The synthesized Ephedra-AuNPs meets the above requirements where it contains a variety of biomolecules which can acts as stabilizing, capping, and reducing agents and could be used as antioxidant, antipyretic, antiasthma and antibacterial (both Gram-positive and Gram-negative), and antifungal agents. It’s resolved to be valuable enough to expand the synthesized material to further studies in light of various synthesis methodologies to scale up the commercialization of gold nanoparticles, valuable properties, and miscellaneous biological applications as well as conduct the research required for the agnostic applications and disease markers. In addition, research should focus on in-vivo explorations so that AuNPs can be exploited further as a medication or carrier for biomedical applications.

6 Conclusion

We fruitfully explored the Ephedra-AuNPs by means of an easy, cost-effictive, energy-economy, and environment-friendly process using Ephedra plant extract. Here, the Ephedra-extract perform as a reducing and capping agent and improved the efficiency of Au owing to its association to form nanoparticles. The accomplished Ephedra-AuNPs were scientifically described by the UV–Vis., FTIR, PXRD, HRTEM, EDX, and XPS analysis. The TEM study exposed the round and triangular figures of Ephedra-AuNPs within 1.3 nm and 15.6 nm size and the XPS investigation corroborated the bioactive functionalities. Ephedra-AuNPs orally treated with different doses to investigate the antipyretic activity on Wister rats where, the Ephedra-AuNPs at a dose of , considerably reduced 83 % of the fever index which is comparably high activity than the standard drug, Aspirin. Similar to the antipyretic activity, the anti-asthmatic study of the Ephedra-AuNPs was performed on the mice. Where, the Ephedra-AuNPs noticeably reduced the yeast-induced febrile response comprise the effect of reducing serum EOS and WBC levels, W/D lung weight ratio, and delaying the OVA-induced latent period (106.4 %) in the anti-asthma test. The anti-fungal and anti-bacterial activities of Ephedra-AuNPs were examined. Where, Gram-positive Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, and Listeria moncytogenes bacteria, and Gram-negative Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Salmonella typhimurium bacteria were treated by 100 μg/mL Ephedra-AuNPs and explored their anti-bacterial activity which illustrated great results superior than the standard drugs SAM and CAZ.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Abdullah, Al-Radadi, N.S., Hussain, T., Faisal, S., Ali Raza Shah, S., 2022. Novel biosynthesis, characterization and bio-catalytic potential of green algae (Spirogyra hyalina) mediated silver nanomaterials. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 29, 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.09.013.

- Untargeted metabolomic profiling and antioxidant capacities of different solvent crude extracts of Ephedra foeminea. Metabolites. 2022;12:451.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Artichoke (Cynarascolymus L.), mediated rapid analysis of silver nanoparticles and their utilisation on the cancer cell treatments. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci.. 2018;15:1818-1829.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of platinum nanoparticles using Saudi’s Dates extract and their usage on the cancer cell treatment. Arabian J. Chem.. 2019;12:330-349.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Facile one-step green synthesis of gold nanoparticles (AuNp) using licorice root extract: antimicrobial and anticancer study against HepG2 cell line. Arabian J. Chem.. 2021;14

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green biosynthesis of flaxseed gold nanoparticles (Au-NPs) as potent anti-cancer agent against breast cancer cells. J. Saudi Chem. Soc.. 2021;25

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Saussurea costus for sustainable and eco-friendlysynthesis of palladium nanoparticles and their biological activities. Arabian J. Chem.. 2022;15(11)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Laboratory scale medicinal plants mediated green synthesis of biocompatible nanomaterials and their versatile biomedical applications. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microwave assisted green synthesis of Fe@Au core–shell NPs magnetic to enhance olive oil efficiency on eradication of helicobacter pylori (life preserver) Arabian J. Chem.. 2022;15(5)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biogenic proficient synthesis of (Au-NPs) via aqueous extract of Red Dragon Pulp and seed oil: Characterization, antioxidant, cytotoxic properties, anti-diabetic anti-inflammatory, anti-Alzheimer and their anti-proliferative potential against cancer cell lines. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2022;29:2836-2855.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Single-step green synthesis of gold conjugated polyphenol nanoparticle using extracts of Saudi’s myrrh: their characterization, molecular docking and essential biological applications. Saudi Pharma. J.. 2022;30(9):1215-1242.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green biosynthesis of Pt-nanoparticles from Anbara fruits: toxic and protective effects on CCl4 induced hepatotoxicity in Wister rats. Arabian J. Chem.. 2020;13:4386-4403.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- One-step synthesis of au nano-assemblies and study of their anticancer activities. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci.. 2018;15:1861-1870.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Environmentally-safe synthesis of gold and silver nano-particles with AL-madinahBarni fruit and their applications in the cancer cell treatments. J. Comput. Theor. Nanosci.. 2018;15:1853-1860.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Radadi, N.S., Abu-Dief, A.M.,2022. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) as a metal nano-therapy: possible mechanisms of antiviral action against COVID-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/24701556.2022.2068585.

- Al-Radadi, N.S., Abdullah, Faisal, S., Alotaibi, A., Ullah, R., Hussain, T., Rizwan, M., Saira, Zaman, N., Iqbal, M., Iqbal, A., Ali, Z., 2022. Zingiberofficinale driven bioproduction of ZnO nanoparticles and their anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, anti-Alzheimer, anti-oxidant, and anti-microbial applications. Inorganic Chemistry Communications 140, 109274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inoche.2022.109274.

- Al-Snafi, A.E.,2017. THERAPEUTIC IMPORTANCE OF EPHEDRA ALATA AND EPHEDRA FOLIATA-A REVIEW. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.376634

- In vitro shoot and callus induction and alkaloid contents of Ephedra intermedia (Schrenket) of Iran. J. Plant Sci. (Sci. Publishing Group). 2015;3:1.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis of colloidal copper hydroxide nanowires using Pistachio leaf extract. Adv. Mater. Lett.. 2015;6:51-54.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The basic properties of gold nanoparticles and their applications in tumor diagnosis and treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gold nanoparticles for the development of clinical diagnosis methods. Anal. Bioanal. Chem.. 2008;391:943-950.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barras, A., Das, M.R., Devarapalli, R.R., Shelke, M. v., Cordier, S., Szunerits, S., Boukherroub, R., 2013. One-pot synthesis of gold nanoparticle/molybdenum cluster/graphene oxide nanocomposite and its photocatalytic activity. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 130–131, 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2012.11.017.

- Ben Lamine, J., Boujbiha, M.A., Dahane, S., Cherifa, A. ben, Khlifi, A., Chahdoura, H., Yakoubi, M.T., Ferchichi, S., el Ayeb, N., Achour, L., 2019. α-Amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitor effects and pancreatic response to diabetes mellitus on Wistar rats of Ephedra alata areal part decoction with immunohistochemical analyses. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 26, 9739–9754. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-019-04339-3.

- Screening of phytochemical, evaluation of phenolic content, antibacterial and antioxydant activities of Ephedra Alata from the Algerian Sahara. J. Appl. Biol. Sci. E. 2022;16:220-229.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ideal counterpart theorizing and the accuracy argument for probabilism. Analysis (United Kingdom). 2018;78:207-216.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New observations on the secondary chemistry of world Ephedra (Ephedraceae) Am. J. Bot.. 2001;88:1199-1208.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Medicinal importance of Ephedra gerardiana in ayurveda and modern sciences: a review. Asian J. Pharm. Pharmacol.. 2021;7:110-117.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Application of gold nanoparticles in biomedical and drug delivery. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2016

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles by Novosphingobium sp. THG-C3 and their antimicrobial potential. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol.. 2017;45:211-217.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles using leaf extracts of Alchornealaxiflora and its tyrosinase inhibition and catalytic studies. Micron. 2021;141

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Elias E Elemike, 2017. Phytosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous leaf extracts of Lippiacitriodora: Antimicrobial, larvicidal and photocatalytic evaluations.

- Elhadef, K., Smaoui, S., ben Hlima, H., Ennouri, K., Fourati, M., ChakchoukMtibaa, A., Ennouri, M., Mellouli, L., 2020. Effects of Ephedra alata extract on the quality of minced beef meat during refrigerated storage: A chemometric approach. Meat Science 170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2020.108246.

- Eco-friendly microwave-assisted green and rapid synthesis of well-stabilized gold and core-shell silver-gold nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2016;136:1128-1136.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer activity of greenly synthesized selenium and zinc composite nanoparticles using ephedra aphylla extract. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1-17.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Faisal, S., Al-Radadi, N.S., Jan, H., Abdullah, Shah, S.A., Shah, S., Rizwan, M., Afsheen, Z., Hussain, Z., Uddin, M.N., Idrees, M., Bibi, N., 2021. Curcuma longa mediated synthesis of copper oxide, nickel oxide and Cu-Ni bimetallic hybrid nanoparticles: Characterization and evaluation for antimicrobial, anti-parasitic and cytotoxic potentials. Coatings 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings11070849.

- Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using an ephedra sinica herb extract with antibacterial properties. J. Med. Bacteriol. Green Synth. Silver. J. Med. Bacteriol.. 2021;10(1, 2):30-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gerber, A., Bundschuh, M., Klingelhofer, D., Groneberg, D.A., 2013. Gold nanoparticles: recent aspects for human toxicology.

- Advances in green synthesis of nanoparticles. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2019

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary phytochemical screening, quantitative analysis of alkaloids, and antioxidant activity of crude plant extracts from Ephedra intermedia Indigenous to Balochistan. Sci. World J.. 2017;2017

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A green chemistry approach for synthesizing biocompatible gold nanoparticles. Nanoscale Res. Lett.. 2014;9:1-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles using the bacteria Rhodopseudomonascapsulata. Mater. Lett.. 2007;61:3984-3987.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plant-mediated green synthesis of iron nanoparticles. J. Nanopart.. 2014;2014:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of gold nanodogbones by the seeded mediated growth method. Nanotechnology. 2007;18

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Gnetales: recent insights on their morphology, reproductive biology, chromosome numbers, biogeography, and divergence times. J. Systemat. Evol. 2016

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Three ABTS•+ radical cation-based approaches for the evaluation of antioxidant activity: fast- and slow-reacting antioxidant behavior. Chem. Pap.. 2018;72:1917-1925.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of metal nanoparticles using plants. Green Chem.. 2011;13:2638-2650.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis and biological activities of gold nanoparticles functionalized with Salix alba. Arabian J. Chem.. 2019;12:2914-2925.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A molecular phylogenetic study of the ephedra distachya/E. sinica complex in Eurasia. Willdenowia. 2011;41:203-215.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Waste-grass-mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles and evaluation of their anticancer, antifungal and antibacterial activity. Green Chem. Lett. Rev.. 2018;11:125-134.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- RP-HPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS qualitative profiling, antioxidant, anti-enzymatic, anti-inflammatory and non-cytotoxic properties of Ephedra alataMonjauzeana. Foods. 2022;11

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Photocatalytic degradation of 4-nitrophenol pollutant and in vitro antioxidant assay of gold nanoparticles synthesized from Apiumgraveolens leaf and stem extracts. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2020;17:2433-2442.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Applications of noble metal-based nanoparticles in medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The convergence of nanotechnology-stem cell, nanotopography-mechanobiology, and biotic-abiotic interfaces: Nanoscale tools for tackling the top killer, arteriosclerosis, strokes, and heart attacks. Nano Select. 2021;2:655-687.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The history of Ephedra (ma-huang) J. Royal College Phys. Edinburgh. 2011;41:78-84.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Selective ABTS radical-scavenging activity of prenylated flavonoids from Cudraniatricuspidata. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006

- [Google Scholar]

- The chloroplast genome of an important herb species, Ephedra sinica (Ephedraceae) Mitochond. DNA Part B: Resour.. 2019;4:3894-3895.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Ephedra foeminea active compounds on cell viability and actin structures in cancer cell lines. J. Med. Plants Res.. 2017;11:690-702.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Improved photocatalytic decomposition of aqueous Rhodamine-B by solar light illuminated hierarchical yttriananosphere decorated ceria nanorods. J. Mater. Res. Technol.. 2019;8:2898-2909.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi, M.A., Mohammed, M.T., Jassim, A.N., Taay, Y.M., 2021. Green synthesis of gold NPs by using dragon fruit: Toxicity and wound healing, in: Journal of Physics: Conference Series. IOP Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1853/1/012039.

- Biological Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Different Groups of Bacteria. In: Nanotechnology in the Life Sciences. Springer Science and Business Media B.V; 2019. p. :63-85.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- LC/MS method development for the determination of the phenolic compounds of Tunisian Ephedra alata hydro-methanolic extract and its fractions and evaluation of their antioxidant activities. S. Afr. J. Bot.. 2019;124:102-110.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesis of gold nanoparticles by Bacillus marisflavi and its potential in catalytic dye degradation. Arabian J. Chem.. 2019;12:4806-4814.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The interaction between gold nanoparticles and cationic and anionic dyes: enhanced UV-visible absorption. PCCP. 2009;11:10513-10518.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical analysis, ephedra procera C. A. Mey. mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparticles, their cytotoxic and antimicrobial potentials. Medicina (Lithuania). 2019;55

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ephedra intermedia mediated synthesis of biogenic silver nanoparticles and their antimicrobial, cytotoxic and hemocompatability evaluations. Inorg. Chem. Commun.. 2022;137

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal properties of chemically defined propolis from various geographical regions. Microorganisms 2022

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study of the antibacterial, antifungal and antioxidant activity and total content of phenolic compounds of cell cultures and wild plants of three endemic species of Ephedra. Molecules. 2010;15:1668-1678.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of gold nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta - Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2008;71:80-85.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant capacity of selected plant extracts and their essential oils. Antioxidants. 2013;2:11-22.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An in vitro comparison of the antioxidant activities of chitosan and green synthesized gold nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2019;211:161-172.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rashed, K., 2021. PHYTOCHEMICAL AND BIOLOGICAL ACTIVITIES OF EPHEDRA ALATA: A REVIEW, www.ijsit.com.

- Re, R., Pellegrini, N., Proteggente, A., Pannala, A., Yang, M., Rice-Evans, C., 1999. Original Contribution ANTIOXIDANT ACTIVITY APPLYING AN IMPROVED ABTS RADICAL CATION DECOLORIZATION ASSAY.

- Control of plasmon resonance of gold nanoparticles via excimer laser irradiation. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process.. 2011;102:153-160.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Total phenols, antioxidant potential and antimicrobial activity of the methanolic extracts of Ephedra laristanica. J. Med. Plants Res.. 2011;5:5713-5717.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rydin, C., Raunsgaard Pedersen, K., Marie Friis, E., 2004. On the evolutionary history of Ephedra: Cretaceous fossils and extant molecules, Royal Botanic Gardens.

- Sarfraz, N., Khan, I., 2021. Plasmonic Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs): Properties, Synthesis and their Advanced Energy, Environmental and Biomedical Applications. Chemistry - An Asian Journal. https://doi.org/10.1002/asia.202001202.

- Sarwar, S., Hanif, M.A., Ayub, M.A., Boakye, Y.D., Agyare, C., 2019. Fenugreek, in: Medicinal Plants of South Asia: Novel Sources for Drug Discovery. Elsevier, pp. 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102659-5.00020-3.

- Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles via biological entities. Materials 2015

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanotechnology in medicine and antibacterial effect of silver nanoparticles. Digest J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2008

- [Google Scholar]

- Biosynthesized CuOnano-platelets: physical properties & enhanced thermal conductivity nanofluidics. Arabian J. Chem.. 2020;13:160-170.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using an aqueous root extract of Morindacitrifolia L. Spectrochim. Acta - Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2014;118:11-16.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles from Vitexnegundo leaf extract to inhibit Lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation through in vitro and in vivo. J. Cluster Sci.. 2020;31:463-477.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In-vitro antimicrobial and anticancer properties of green synthesized gold nanoparticles using Anacardiumoccidentale leaves extract. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2019;26:455-459.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, B. 1; V.B.S.M. 2; P.T.A.A. 1 ; M.S.B. 3 ; M.C.M. 4 ; K.K. 5 ; M.M. 5 , 2019. Antioxidant and Photocatalytic Activity of Aqueous Leaf Extract Mediated Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Passifloraedulis f. flavicarpa 19.

- Tiss, M., Boujbiha, M., Hamden, K., 2020. Ephedra alata extracts exhibits anti-obesity, anti-hyperlipidaemic, anti-hyperglycemia, anti-antipyretic and analgesic effects through the inhibition of lipase, α-amylase and inammation. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-23622/v1.

- Vijaya Kumar, P., Mary Jelastin Kala, S., Prakash, K.S., 2018. Synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Xanthium Strumarium leaves extract and their antimicrobial studies: A green approach. Rasayan Journal of Chemistry 11, 1544–1551. https://doi.org/10.31788/RJC.2018.1144044.

- Gold, silver, and palladium nanoparticles: a chemical tool for biomedical applications. Front. Chem. 2020

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of gold nanoparticles using Citrus maxima peel extract and their catalytic/antibacterial activities. IET Nanobiotechnol.. 2017;11:523-530.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A-type proanthocyanidins from the stems of Ephedra sinica (Ephedraceae) and their antimicrobial activities. Molecules. 2013;18:5172-5189.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]