Translate this page into:

Biodiversity and application prospects of fungal endophytes in the agarwood-producing genera, Aquilaria and Gyrinops (Thymelaeaceae): A review

⁎Corresponding authors at: No. 16, Dongzhimen Southern Street, Beijing 100700, China. huangluqi01@126.com (Luqi Huang), juanliu126@126.com (Juan Liu)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Agarwood is originated from the resinous part of Aquilaria and Gyrinops plants and has been a precious biomaterial for applications in traditional medicine, perfumery, cosmetics, and religious purposes all over the world. In the wild, the formation of agarwood is related to the defense mechanism of the tree in response to physical damage that allows further microbial infestation into its wood, while having the whole tree covered with agarwood would take up a long time, and it rarely happens. For Aquilaria and Gyrinops, the presence of endophytes is mainly found derived from the tree. The isolated endophytes could be important sources of natural products, while some could contribute to the formation of agarwood in the tree, which is safe for the environment and human health. This review summarized the biodiversity of fungal endophytes recorded in Aquilaria and Gyrinops and their potential effects on host trees. Till now, 67 endophytic genera have been isolated from Aquilaria and Gyrinops, and 18 ones were found responsible for the promotion of agarwood formation. Additionally, 92 compounds have been reported to be produced by the agarwood endophytes, and 52 ones displayed biological activities, most of which have anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, and anti-cancer activities. Nevertheless, fungal endophytes are promising agents that deserved to be further studied and scaled up to a commercial level for the production of agarwood oil, but the role of endophytes in the agarwood host trees needs to be furtherly investigated in future studies.

Keywords

Agarwood

Fungal endophytes

Aquilaria

Gyrinops

1 Introduction

Members of the agarwood-producing genera, Aquilaria and Gyrinops, are tropical evergreen trees commonly grown in the lowland forest regions, which are mainly distributed in southeast Asia. Agarwood is a highly valuable fragrance derived from the resinous wood of Aquilaria and Gyrinops trees. The intriguing aroma of agarwood makes it a valuable ingredient that has a long history record in the production of traditional medicines as well as used in religious activities, while at present, it is regarded as a luxury biomaterial in perfumery and cosmeceutical industries (Huang et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2020; Xie et al., 2020). Although all 30 species (21 Aquilaria species and 9 Gyrinops species) are believed to be able to produce agarwood, to date, evidence of agarwood formation was only reported for 14 species of Aquilaria and eight species of Gyrinops (Auri et al., 2021; Compton and Zich, 2002; Hou 1964; Kiet et al., 2005; Lee and Mohamed, 2016; Ng et al., 1997; Subasinghe et al., 2012; Turjaman et al., 2016) (Table 1). The high demand but rare occurrence of agarwood in the wild has led to the over-exploitation of these valuable species in the past, causing the decline in the population size of these agarwood-producing species in the wild. As a consequence, some of these species are classified as “Vulnerable”, “Endangered”, and “Critically Endangered” (IUCN 2022), as well as to aid in conserving the resources, all members of the agarwood-producing genera, Aquilaria and Gyrinops, are currently placed under strict monitoring by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) in Appendix II (UNEP-WCMC, 2022).

Species Name

Distribution*

Basionyms and synonyms

Agarwood production report

Aquilaria apiculata Merr.

Philippines

–

Aquilaria baillonii Pierre ex Lecomte

Cambodia; Viet Nam; Lao People's Democratic Republic

–

Ng et al., 1997

Aquilaria banaensis P.H. Hô

Viet Nam

Aquilaria banaensae

Aquilaria beccariana Tiegh.

Brunei Darussalam; Indonesia; Malaysia

Aquilaria cumingiana var parvifolia; Aquilaria grandifolia; Gyrinops brachyantha; Gyrinopsis grandifolia

Faridah et al., 2009Compton and Zich, 2002Turjaman et al., 2016

Aquilaria brachyantha (Merr.) Hallier f.

Phillipines

Gyrinopsis brachyantha

Aquilaria citrinicarpa (Elmer) Hallier f.

Phillipines

Gyrinopsis citrinicarpa

Aquilaria crassna Pierre ex Lecomte

Cambodia; Viet Nam; Thailand; China; Malaysia

–

Yoswathana, 2013Ng et al., 1997

Aquilaria cumingiana (Decne.) Ridl.

Phillipines; Indonesia; United State; Malaysia

Aquilaria pubescens; Decaisnella cumingiana; Gyrinopsis cumingiana; Gyrinopsis cumingiana var. pubescens; Gyrinopsis decemcostata; Gyrinopsis pubifolia

Turjaman et al., 2016

Aquilaria decemcostata Hallier f.

Phillippines

–

Aquilaria filaria (Oken) Merr.

Indonesia; Phillipines; Papua New Guinea

Aquilaria cuminate; Aquilaria tomentosa; Gyrinopsis acuminate; Pittosporum filarium

Compton and Zich, 2002Turjaman et al., 2016

Aquilaria hirta Ridl.

Indonesia; Malaysia; Singapore; Thailand

Aquilaria moszkowski

Faridah et al., 2009Compton and Zich, 2002Turjaman et al., 2016

Aquilaria khasiana Hallier f.

India

–

Hallier, 1992

Aquilaria malaccensis Lam.

Bangladesh; Bhutan; China; France; India; Indonesia; Lao People's Democratic Republic; Mauritius; Malaysia; Philippines; Viet Nam; Thailand; Sri Lanka

Agallochum malaccense; Aloexylum agallochum; Aquilaria agallocha; Aquilaria ovate; Aquilaria moluccensis; Aquilaria secundaria; Aquilariella malaccense; Aquilariella malaccensis

Chowdhury et al., 2003Broad, 1995Rahayu and Putridan Juliarni, 2007Turjaman et al. 2016

Aquilaria microcarpa Baill.

Brunei Darussalam; Indonesia; Malaysia; Italy

Aquilaria borneensis; Aquilariella borneensis; Aquilariella microcarpa

Santoso et al., 2011Faridah et al., 2009Compton and Zich, 2002Turjaman et al. 2016

Aquilaria parvifolia (Quisumb.) Ding Hou

Philippines

Gyrinopsis parvifolia

Aquilaria rostrata Ridl.

Malaysia; Thailand

–

Faridah et al., 2009

Aquilaria rugosa K.Le-Cong & Kessler

Thailand; Viet Nam

–

Kiet et al., 2005

Aquilaria sinensis (Lour.) Spreng.

China; Thailand; Malaysia; Viet Nam

Agallochum grandiflorum; Agallochum sinense; Aquilaria chinensis; Aquilaria grandiflora; Aquilaria ophispermum; Ophispermum sinense

Liu et al., 2013Liu et al., 2022Ng et al., 1997Zhang et al., 2014

Aquilaria subintegra Ding Hou

Thailand; Malaysia

–

Hou, 1964

Aquilaria urdanetensis (Elmer) Hallier f.

Philippines

Gyrinopsis urdanetense; Gyrinopsis urdanetensis

Aquilaria yunnanensis S.C.Huang

China

–

Sun et al., 2019Zhang et al. 2019

Gyrinops caudata (Gilg) Domke

Indonesia; Papua New Guinea

Aquilaria caudata; Brachythalamus caudatus; Gyrinops audate

Auri et al., 2021

Gyrinops decipiens Ding Hou

Indonesia

–

Turjaman et al. 2016

Gyrinops ledermannii Domke

Indonesia; Papua New Guinea

–

Compton and Zich 2002Turjaman et al. 2016

Gyrinops moluccana (Miq.) Baill.

Indonesia

Aquilaria moluccana; Lachnolepsis moluccana

Turjaman et al. 2016

Gyrinops podocarpa (Gilg) Domke

Indonesia; Papua New Guinea

Aquilaria podocarpus; Brachythalamus podocarpus; Gyrinops ledermannii; Gyrinops podocarpus

Turjaman et al. 2016

Gyrinops salicifolia Ridl.

Indonesia; Papua New Guinea

Gyrinopsis salicifolia

Shao et al., 2016Dong et al., 2019Turjaman et al., 2016

Gyrinops versteegii (Gilg) Domke

Indonesia; Papua New Guinea

Aquilaria versteegii; Brachythalamus versteegii

Faizal et al., 2020Faizal et al., 2022Turjaman et al., 2016Nasution et al., 2020

Gyrinops vidalii P.H.Hô

Thailand; Lao People's Democratic Republic

–

Gyrinops walla Gaertn.

Indonesia; Papua New Guinea; India; Sri Lanka

Aquilaria walla

Subasinghe et al., 2012

Due to the conservation status and low yield of agarwood production in the wild, relying on the natural population as a source of agarwood to meet the increasing market demand is rather unviable (Deng et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2018). Therefore, the domestication of agarwood-producing trees was introduced and mass cultivation coupled with good agriculture practices was promoted (Liu et al., 2013; Persoon and Beek, 2008). In general, agarwood is naturally formed in Aquilaria and Gyrinops trees as a result of self-defense against physical damage or microbial infection on the trees (Soehartono and Newton, 2000; Xu et al., 2013). While physical damage to the tree is to introduce an opening; fungal infection has always been considered to be a key factor in agarwood formation (Rasool and Mohamed, 2016).

Endophytic fungi can live inside plant tissues without any disease symptoms. The evidence of the use of endophytic fungi to induce agarwood formation has been present for a long time, i.e. 1934 (Turjaman et al., 2016; Yoswathana, 2013), while the fungi that show promising results in the production of agarwood are developed into fungal inoculum. To mimic the mechanism of agarwood formation via microbial infestation, endophytic fungi are introduced into the cultivated stands via inoculation technique in hope that the time to form agarwood will be reduced and the yield could be increased at the same time. It is believed that the quality of the agarwood formed relies heavily on the species or strains selected among the different endophytic fungi; thus, research and exploration to discover additional useful endophytic fungi that could warrant better yield and quality of agarwood are still ongoing (Liu et al., 2022). Additionally, the secondary metabolites from endophytic fungi of agarwood lead the way as sources for various pharmacological properties.

In order to provide a comprehensive review of the information on endophytic fungi involved in the formation of agarwood, we mined various published scientific reports and summarized the distribution and biodiversity of fungal endophytes present in Aquilaria and Gyrinops. In addition, the secondary metabolites produced as well as the pharmacological values of these agarwood-related fungal endophytes in Aquilaria and Gyrinops were documented and discussed too. Finally, the effects on the host trees of Aquilaria and Gyrinops by fungal endophytes were discussed. We believe that our review could be useful for researchers to find innovative directions in the research field of agarwood endophytes.

2 Ecological distribution of Aquilaria and Gyrinops species

Aquilaria and Gyrinops species are widely distributed in southeast Asia, especially Indomalesia region (Lee and Mohamed, 2016). Recently, nine from the total of 21 species in the genus Aquilaria genus are known to grow in Malaysia (data from GBIF-Global Biodiversity Information Facility; Lee and Mohamed, 2016; Lee et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2022), including A. beccariana, A. crassna, A. cumingiana, A. hirta, A. malaccensis, A. microcarpa, A. rostrate, A. sinensis, and A. subintegra (Table 1), which is the country with the most species of Aquilaria. And five species of Aquilaria are naturally distributed in Malaysia, including A. beccariana, A. hirta, A. malaccensis, A. microcarpa, and A. rostrate (Lee et al., 2016). The other four are transplanted from China, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Meanwhile, eight of the total of nine species in the Gyrinops genus are known to naturally grow in Indonesia, except for G. vidalii which is only distributed in Thailand and Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Table 1).

At present, the wild resources of Aquilaria and Gyrinops are rather limited. Thus, the reports on agarwood production are confined to 14 species of Aquilaria and eight species of Gyrinops (Table 1). More and more plantation areas are of larger scale, and A. sinensis occupies more than 5245 ha in China, which has the largest plantation size of all the species reported now (Turjaman et al., 2016; Yin et al., 2016). Additionally, A. malaccensis is the most widespread and cultivated species, including 13 countries (Table 1). Thus, A. malaccensis and A. sinensis are the most studied species recently. However, Gyrinops is less planted and studied for its slow-growing features (Lee et al., 2018). Among all the Gyrinops species, G. versteegii is the most popular species in eastern Indonesia, but it is less favored compared to A. malaccensis when it comes to agarwood cultivation in Indonesia (Faizal et al., 2022; Nasution et al., 2020; Turjaman et al., 2016).

3 Biodiversity of fungal endophytes in Aquilaria and Gyrinops

Endophytes are microorganisms that maintain endosymbiotic relationship within plants (Turjaman et al., 2016). At present, studies on endophytic biodiversity on Aquilaria received more attention than that of Gyrinops. Eventually, species that are involved in such studies are mainly those selected as cultivation species, including A. crassna, A. malaccensis, A. microcarpa, A. sinensis, A. subintegra, G. caudata, G. verstegii, and G. walla. However, the biodiversity of fungal endophytes has not been investigated in the other species of Aquilaria and Gyrinops due to the limited plantations, slow-growing features, and difficult species-identification (Hidayat et al., 2021; Lee et al., 2018; Turjaman et al., 2016). Based on our knowledge, a total of 42 fungal families and 67 fungal genera were isolated and identified in these eight agarwood-producing taxa, and 82.8 % of fungal species belonged to Ascomycota (Table 2). Among all the above endophytic genera, Fusarium is the most encountered species recorded in all studied taxa, except for A. microcarpa and G. caudata. a. Distribution percentage = host species number of an isolated fungal genus × 100 % / number of all the reported host species (nine species which include A. crassna, A. malaccensis, A. microcarpa, A. sinensis, A. subintegra, G. walla, G. caudata, and G. verstegii).

Fungal taxa

Host species

Distribution percentagesa

Agarwood-inducing methods

Inducing time

Inducing effects

References

Ascomycota

1. Apiosporaceae

1. Arthrinium

A. subintegra

12.5 %

---

---

---

Monggoot et al., 2017

2. Nigrospora

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Li et al., 2014

2. Ascomycota incertae sedis

3. Gonytrichum

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

3. Aspergillaceae

4. Aspergillus *

G. walla

25.0 %

---

---

---

Vidurangi et al., 2018

A. crassna

Solid inoculation

1 year

Tissue discoloration and resin content improved

(Subasinghe et al., 2019)

---

---

Inducing agarwood formation

Bose, 1938

5. Penicillium *

A. sinensis

25.0 %

Solid inoculation

30 days

Promoting sesquiterpene accumulation

Liu et al., 2022

Infusion

10 months

Promoting the accumulation of active ingredients

Wang et al., 2016

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

A. malaccensis

---

---

---

(Chhipa et al., 2017)

4. Botryosphaeriaceae

6. Endomelanconiopsis

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Chen et al., 2018

7. Diplodia *

Aquilaria sp.

---

---

---

Inducing agar formation

Bose, 1938

8. Lasiodiplodia *

A. sinensis

37.5 %

Inoculating the fermentation broth

2 months

Promoting the agarwood formation

Chen et al., 2017a

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011

Inoculation of solid strains

6 months

Promotion of 34 sesquiterpenes and 4 aromatic compounds

Zhang et al., 2014

Infusion

10 months

Promoting the accumulation of active ingredients

Wang et al., 2016

A. malaccensis

---

---

---

Mohamed et al., 2010

A. crassna

---

---

---

Chi et al., 2016

---

---

---

Wang et al., 2019

9. Botryosphaeria *

A. sinensis

37.5 %

Formic acid and pinhole-infusion

1 ∼ 2 years

Producing high yield and high quality artificial agarwood in a relatively short time

Tian et al., 2013

Infusion

10 months

Promoting the accumulation of active ingredients

Wang et al., 2016

Liquid injection

160 days

Promote the formation of the main components of agarwood and incenses

Feng, 2008

A. crassna

---

---

Inducing agar formation

Bose, 1938

G. walla

---

---

---

Vidurangi et al., 2018

5. Chaetomiaceae

10. Chaetomium *

A. malaccensis

25.0 %

Artificial boring onto the plants

30 days

It is different between the oils obtained from naturally infected and healthy plants with regards to their quality.

Tamuli et al., 2005

A. sinensis

---

---

---

Tian et al., 2013

6. Chaetothyriales incertae sedis

11. Sarcinomyces

G. walla

12.5 %

---

---

---

Vidurangi et al., 2018

7. Cladosporiaceae

12. Cladosporium *

A. sinensis

37.5 %

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

Solid inoculation

30 days

C. cladosporioides promotes the accumulation of agarwood sesquiterpenes and chromones, while C. parahalotolerans could not promote agarwood formation.

Liu et al., 2022

A. malaccensis

---

---

---

Premalatha and Kalra, 2013

A. subintegra

---

---

---

Monggoot et al., 2017

8. Coniothyriaceae

13. Coniothyrium

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011

9. Diaporthaceae

14. Diaporthe

A. sinensis

50.0 %

---

---

---

Chen et al, 2018

A. microcarpa

---

---

---

(Vidurangi et al., 2018)

A. subintegra

---

---

---

Monggoot et al.,2017

G. verstegii

---

---

---

Mega et al., 2016

10. Didymellaceae

15. Epicoccum

A. malaccensis

25.0 %

---

---

---

Bhattacharyya et al, 1952

A. sinensis

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009Cui et al., 2011

16. Leptosphaerulina

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011

11. Didymosphaeriaceae

17. Paraconiothyrium

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011

18. Montagnulaceae

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Wang et al., 2016

12. Dipodascaceae

19. Geotrichum

A. crassna

25.0 %

---

---

---

Chi et al., 2016

A. sinensis

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

20. Galactomyces

A. crassna

12.5 %

---

---

---

Chi et al., 2016

13. Dissoconiaceae

21. Ramichloridium

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Tian et al., 2013

14. Erysiphaceae

22. Ovulariopsis

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

15. Glomerellaceae

23. Colletotrichum

A. crassna

50.0 %

---

---

---

Chi et al, 2016

A. sinensis

---

---

---

Tian et al. 2013

A. subintegra

---

---

---

Monggoot et al., 2017

G. walla

---

---

---

Vidurangi et al., 2018

16. Herpotrichiellaceae

24. Rhinocladiella

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

25. Cladophialophora

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

17. Hypocreaceae

26. Trichoderma *

A. sinensis

50.0 %

---

---

---

Li et al., 2012

Infusion

10 months

Promoting the accumulation of active ingredients

Wang et al., 2016

A. malaccensis

---

---

---

Mohamed et al.,2010

G. versteegii

---

---

Contributing to the formation of agarwood sapwood

Mega et al., 2020

G. walla

---

---

---

Vidurangi et al., 2018

27. Hypocrea *

A. malaccensis

25.0 %

---

---

---

Mohamed et al., 2010

A. sinensis

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011

Liquid injection

160 days

Promoting the transformation of agarwood and speeding up the process of making incense

Feng, 2008

18. Hypocreales incertae sedis

28. Acremonium *

A. microcarpa

37.5 %

---

---

The wood color and terpenoid compounds were changed.

Rahayu and Putridan Juliarni, 2007

G. verstegii

---

---

---

Mega et al., 2016

G. caudata

Fungal-induction with pruning

3–6 months

Showing a considerable effect in wood internal tissue and fragrance.

Auri et al., 2021

29. Cephalosporium

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

30. Verticillium

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Wang et al., 2016

19. Hypocreaceae

31. Diplocladium

G. walla

12.5 %

---

---

---

Subasinghe et al., 2019

20. Lasiosphaeriaceae

32. Fimetariella

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Tao et al., 2011aTao et al., 2011b

21. Mycosphaerellaceae

33. Mycosphaerella (Synonym: Davidiella)

A. sinensis

25.0 %

---

---

---

Tian et al., 2013

A. malaccensis

---

---

---

Premalatha and Kalra, 2013

34. Botryodyplodis * (Synonym: Physalospora)

Aquilaria sp.

---

---

---

Inducing agar formation

Bose, 1938

22. Nectriaceae

35. Cylindrocladium

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Tian et al., 2013

36. Fusarium *

A. crassna

75.0 %

---

---

---

Chi et al., 2016

---

0.5 ∼ 1.5 years

Inducing the formation of agarwood

Nobuchi and Siripatanadilok, 1991

A. sinensis

Formic acid and pinhole-infusion

1 ∼ 2 years

Producing high yield and high quality artificial agarwood in a relatively short time

Tian et al., 2013

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011

Infusion

10 months

Promoting the accumulation of active ingredients

Wang et al., 2016

Inoculating the fermentation broth

2 months

Promoting the agarwood formation at the initial stage

Chen et al., 2017a

A. malaccensis

---

---

---

Mohamed et al., 2010

A. subintegra

---

---

---

Monggoot et al., 2017

G. walla

---

---

---

Vidurangi et al., 2018

Solid inoculation method

1 year

Promoting the tissue discoloration and resin content

Subasinghe et al., 2019

G. versteegii

---

---

Contributing to the formation of agarwood sapwood

Mega et al., 2020

Fungal inoculant formulation

16 months

Producing the agarwood with good quality.

Mega et al., 2016

37. Nectria

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Wang et al., 2016

23. Phyllostictaceae

38. Guignardia

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

24. Pichiaceae

39. Pichia

A. malaccensis

25.0 %

---

---

---

Premalatha and Kalra, 2013

A. sinensis

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011

25. Pleosporaceae

40. Curvularia

A. crassna

37.5 %

---

---

---

Chi et al., 2016

A. malaccensis

---

---

---

Mohamed et al., 2010

G. verstegii

---

---

---

Mega et al., 2016

41. Alternaria

A. malaccensis

25.0 %

---

---

---

Premalatha and Kalra, 2013

A. sinensis

---

---

---

Tian et al., 2013

42. Pleospora

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

43. Cochliobolus

A. malaccensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Mohamed et al., 2010

44. Phoma

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011Tian et al., 2013

26. Saccharomycetaceae

45. Lodderomycetes

A. malaccensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Premalatha and Kalra, 2013

27. Sclerotiniaceae

46. Monilia

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

28. Sporocadaceae

47. Pestalotiopsis *

A. sinensis

25.0 %

Infusion method

6 months

Promoting the agarwood production

Chen et al., 2014Tian et al., 2013

A. subintegra

---

---

---

Monggoot et al., 2017

48. Preussia

A. malaccensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Premalatha and Kalra, 2013

29. Togniniaceae

49. Phaeoacremonium *

A. malaccensis

25.0 %

---

---

---

Premalatha and Kalra, 2013

A. sinensis

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011

Solid inoculation

30 days

Promoting the agarwood sesquiterpene accumulation

Liu et al., 2022

30. Trichocomaceae

50. Sagenomella

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Tian et al., 2013

31. Valsaceae

51. Phomopsis

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Tian et al., 2013

32. Xylariaceae

52. Xylaria *

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011

---

---

---

Tian et al., 2013

Solid inoculation

2 ∼ 8 months

Promoting agilawood accumulation

Cui et al., 2013

53. Nemania

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Tibpromma et al, 2021

54. Nodulisporium

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Tian et al., 2013Wu et al., 2010

33. Massarinaceae

55. Massarina

A. malaccensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Premalatha and Kalra, 2013

Mucoromycota

34. Cunninghamellaceae

56. Cunninghamella

A. malaccensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Mohamed et al., 2010

35. Lichtheimiaceae

57. Rhizomucor

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Cui et al., 2011

36. Mortierellaceae

58. Mortierella

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

37. Mucoraceae

59. Mucor

G. walla

12.5 %

---

---

---

Subasinghe et al., 2019

60. Rhizopus *

G. versteegii

12.5 %

---

---

Promoting the formation of agarwood sapwood

Mega et al., 2020

Mixture of fungal liquid with Fusarium solani

---

Promoting the production of agarwood with best quality

Mega et al., 2016

Basidiomycota

38. Exobasidiaceae

61. Glomerularia

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

39. Fomitopsidaceae

62. Fomitopsis *

A. sinensis

12.5 %

Infusion method

6 months

Promoting the agarwood production

Chen et al., 2017b

40. Meripilaceae

63. Rigidoporus *

A. sinensis

12.5 %

Trunk surface agarwood-inducing technique

2 months

Promoting the agarwood formation

Chen et al., 2018

41. Psathyrellaceae

64. Coprinopsis

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Chen et al., 2018

42. Russulaceae

65. Russula

A. subintegra

12.5 %

---

---

---

Monggoot et al., 2017

Unclassified

66. Mycelia sterilia

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Gong and Guo, 2009

67. Pleosporales

A. sinensis

12.5 %

---

---

---

Chen et al., 2018

It is worth mentioning that there is a discrepancy in the endophytic fungal diversity pattern in Aquilaria trees based on their growing regions, such as A. sinensis, an agarwood-producing species endemic to China that is naturally distributed in three provinces, including Guangdong, Guangxi, and Hainan. It was proposed that the biodiversity of fungal endophytes in A. sinensis might be due to the various geographical locations containing different levels of the atmosphere, light, soil moisture, and nutrient contents. To date, endophytic fungal studies on A. sinensis are abundant and well-documented. It was revealed that the dominant fungal genus from the population in Hainan was Penicillium (Zhang et al., 2009a), while the endophytic fungal diversity for A. sinensis growing in Guangxi was dominated by Fusarium (Huang et al., 2017). The fungal diversity could also be regionally specific, in which two genera, Chaetomium and Pichia, were only identified in A. sinensis of Hainan, but not from those in Guangdong and Guangxi (Chen et al., 2019). Also, the fungal diversity of agarwood derived from A. sinensis showed regional specificity. Lignosphaeria is the dominant fungal genus in agarwood samples produced from Haikou and Wanning in Hainan province. Perenniporia and Pyrigemmula are the dominant fungal genera in agarwood products from Danzhou and Ledong in Hainan province. Phaeoacremonium is the dominant fungal genus in agarwood products collected from Huazhou and Dongguan in Guangdong province.

Furtherly, the variation in microbiome composition is represented by multiple plant host organs, and tissue types (Cregger et al., 2018; Jia et al., 2016). In general, most of the fungal endophytes reside in the root, stem, and leaf at the same time; yet, the leaf tissue contains more fungal species when compared to the root and stem parts. So far, a total of 16 fungal endophytes were discovered commonly present in all three vegetative parts of A. sinensis, including Botryosphaeria, Cephalosporium, Cladophialophora, Epicoccum, Fusarium, Geotrichum, Glomerularia, Gonytrichum, Guignardia, Monilia, Mortierella, Mycelia sterilia, Ovulariopsis, Penicillium, Pleospora, and Rhinocladiella (Gong and Guo, 2009; Tian et al., 2013). On the other hand, four were reported specific to the leaf tissue of A. sinensis, including Alternaria, Cylindrocladium, Phoma, and Phomopsis (Gong and Guo, 2009; Tian et al., 2013), suggesting that these fungal endophytes are only able to survive under certain habitat, which in this event, the requirement for survival was fulfilled in the leaf tissue, but not in the root and stem parts.

At the stem and branch part, fungal endophytes not only colonize the healthy part (white wood), but also can be found in the resinous part (agarwood). Additionally, the diversity of fungal endophytes in resinous wood is much higher than that in the healthy wood of Aquilaria (Chen et al., 2017a); Liu et al., 2022). Based on the studies on A. malaccensis and A. sinensis, it was deduced that the resinous wood of the trees not only contained some of the fungal endophytes which were recorded to be present in both the healthy and resinous wood of the tree, such as Alternaria sp., Hypocrea sp., Lasidiplodia sp., and Trichoderma sp., but also included some of the fungal endophytes which were enriched in the resinous wood, i.e. Cladosporium sp., Curvularia sp., Fusarium sp., Phaeoacremonium sp., and Preussia sp. (Liu et al., 2022; Mohamed et al., 2010; Tian et al., 2013). Endophytic fungi isolated from resinous parts were proven to be good candidates in developing fungal inoculum that could promote agarwood production; however, only a few were evaluated on their efficacies. To date, 18 fungal genera were reported on their capability to promote the formation of agarwood, including Acremonium sp., Aspergillus sp., Botryodyplodias sp., Botryosphaeria sp., Chaetomium sp., Cladosporium sp., Diplodia sp., Fomitopsis sp., Fusarium sp., Hypocrea sp., Lasiodiplodia sp., Penicillium sp., Pestalotiopsis sp., Phaeoacremonium sp., Rhizopus sp., Rigidoporus sp., Trichoderma sp., and Xylaria sp. (Table 2).

Given that the diversity of endophytic fungi in Aquilaria trees could be varied in different regions, little was reported for other agarwood-producing species, especially those from Gyrinops. While the diversity of endophytic fungi in different Aquilaria host parts might be related to the environmental filtering or biotic interaction at the species level which was similar to Populus trees (Cregger et al., 2018). The fungal endophytes that can be identified in the while wood and resinous wood of Aquilaria and Gyrinops could be varied largely. Therefore, it is suggested that studies on endophytic fungi in other agarwood-producing species need to be hastened to uncover the uncertainties.

4 Effects on the host trees of Aquilaria and Gyrinops by endophytes

4.1 Use of fungal endophytes in the promotion of agarwood

In nature, endophytes could maintain endosymbiotic relationship within plants without any harm. However, after the trees of Aquilaria and Gyrinops were wounded, the micro-ecosystem balance was broken, and some of the fungal endophytes might grow fast and could trigger the self-defense reaction of the tree and thus, stimulate the formation of secondary metabolites that protect the host trees against invasions and diseases (Cui et al., 2013; Faizal et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2013). Similarly, the inoculating the isolated endophytes with agarwood promoting ability to the holed trees could quickly induce the phosphorylation of the plant immune reaction and promote agarwood accumulation (Liu et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2013). Therefore, the agarwood produced in the tree is recognized as the product of the tree’s defense response (Xu et al., 2013). Since the work to investigate the relationship between fungi and agarwood-producing trees in the process of agarwood formation started off in the early nineteenth century, for the past two decades, a considerable number of studies provided evidence on the crucial roles of fungi in enhancing agarwood formation (Huang et al., 2013; Mega et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2014). It is believed that endophytes secrete signals that will initiate the defense mechanism of the tree; thus, endophytes promote the formation of agarwood (Chen et al., 2017; Sen et al., 2017). Chemometric analysis revealed that aroma (e.g. dodecane, 4-methyl-, tetracosane) in Fusarium sp. played a direct role in the activation of A. malaccensis tree’s defense and secondary metabolism (Sen et al., 2017). Fungal infection often leads immediately to the increased formation of free fatty acids that trigger oxidative burst and fatty acid oxidation cascades leading to the production of oxylipins such as jasmonates (Sen et al., 2017). And the endophytic strains of Lasiodiplodia theobromae were found to produce jasmonic acid (JA) (Chen et al., 2017). JA is known to be one of the crucial signal transducers that is responsible to induce sesquiterpene and chromone derivative formation in A. sinensis and A. malaccensis (Faizal et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2016). Furthermore, agarwood sesquiterpene accumulation can also be achieved by having Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum to induce phosphorylation of the transcription factors (TFs)-mevalonate (MVA) network in A. sinensis (Liu et al., 2022). Despite studies on the molecular interaction between agarwood-producing trees and fungal endophytes have been constantly reported, the findings are still limited and in-depth research ought to be fostered.

To date, six fungal taxa, i.e. Fusarium sp., Trichoderma sp., Acremonium sp., Curvularia sp., Cunninghamella sp., and Phaeoacremonium sp., were commonly known to be potential agents in promoting agarwood formation in Aquilaria and Gyrinops trees (Blanchette 2003; Hidayat et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022; Mohamed et al., 2010). For the endophytes, Fusarium was most reported when compared to other fungal taxa; while for the host plant, studies on A. sinensis were most abundant (Table 2). In A. sinensis, it is believed that agarwood formed with the aid of Cladorrhinum bulbillosum, Fusarium solani, Gongronella butleri, Humicola grisea, Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum, Rigidoporus vinctus, Saitozyma podzolica, and Tetracladium marchalianum was able to produce high-quality raw material for essential oil production (Chen et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2014). So far, a total of 12 fungal taxa were identified to induce agarwood formation in A. sinensis, including Botryosphaeria, Cladosporium, Fusarium, Fomitopsis, Hypocrea, Lasiodiplodia, Phaeoacremonium, Pestalotiopsis, Penicillium, Rigidoporus, Trichoderma, and Xylaria (Table 2). Three fungal taxa, Aspergillus sp., Botryosphaeria sp., and Fusarium sp. were also reported useful in promoting agarwood formation in A. crassna (Chi et al., 2016), while a mixture of fungi Phialophora sp. and Fusarium sp. applied to A. crassna could result in higher sesquiterpene content compared to the chemical and mechanical treatments (Thanh et al., 2015). Similar to Aquilaria, endophytes in Gyrinops also play an active role in the agarwood development of trees. In Gyrinops walla, the endemic species of Sri Lanka, Aspergillus niger and Fusarium solani have been described to be contributing to agarwood formation; Aspergillus niger is more effective than Fusarium solani in the tree host tissue discoloration and resin content (Subasinghe et al., 2019). On the other hand, three fungal taxa, including Fusarium sp., Rhizopus sp., and Trichoderma sp., were proven effective in the promotion of agarwood in Gyrinops versteegii, a plantation species that is mass cultivated in the western region of Indonesia (Mega et al., 2020; (Faizal et al., 2020)).

4.2 Endophytes improve the ecological adaptability of Aquilaria and Gyrinops

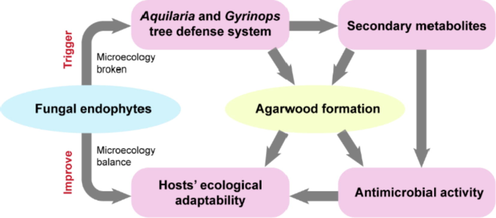

Another function of fungal endophytes of Aquilaria and Gyrinops is improving the ecological adaptability of hosts. Different types of fungi strains could induce the different compounds of Aquilaria and Gyrinops (Monggoot et al., 2017; Mega et al., 2020), which could explain the diversity of agarwood components to increase the resistance to environmental stresses. Similarly, either Aquilaria or Gyrinops grows in certain places with different geographic and climate conditions with certain kinds of fungi, which could promote the ecological adaptability of the host. Consistent with the roles of fungi in the plant defense system, they may be a contributory role in increasing antimicrobial activity, because the resinous site of agarwood tree has a less fungal abundance. When A. malaccensis was infected by Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Cunninghamella bainieri, and Fusarium solani, the abundance of fungi decreased after wounding and the number of target DNA molecules also declined, especially at 6–12 months of post-injury (Mohamed et al., 2014). The lower level of fungal species may be due to the high level of terpenes which are the major components of agarwood and can prevent or control pathogen attacks (Tamuli et al., 2005; Naef, 2011; Zulak and Bohlmann, 2010). Similarly, the agarwood derived from the infected A. sinensis and decayed Gyrinops spp. could show antifungal activity against Candida albicans, Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium solani, and Lasiodiplodia theobromae (Hidayat et al., 2021; Zhang et al. 2014). So it is believed that the fungi can trigger the plant defense system to protect plants from invasions. And the metabolites produced by fungi also can provide protection for the host, which gives plants the ability to be resistant to abiotic and biotic stresses (Chowdhary et al., 2012; Jong 2012; Kharwar et al., 2011; Kumar and Kaushik, 2013; Suryannaryanan et al., 2009). And agarwood endophytes can also produce chemical compositions such as 2-phenylethyl-1H-indol-3-yl-acetate, (2R)-(3-indolyl)-propionic acid, and 9,11-dehyroergosterol peroxide, which displayed phytotoxic activity, cytotoxic activity, and anti-fungi and anti-bacterial activities, resulting in the enhancement of plant ecological adaptability. However, there are also a plenty of compounds, such as benzylacetone, benzaldehyde, palustrol, anisylacetone and chromone derivatives, the ecological functions of which have not been explored. It is possible that the fungal endophyte is one of the factors to resist the invasion of exogenous pathogens and to keep the plant growing well. Thus, we summarized the effects of fungal endophytes on the host trees of Aquilaria and Gyrinops on two sides: inducing the plant defense system and improving their ecological adaptability (Fig. 1).

Effects of endophytes on their agarwood host trees, Aquilaria and Gyrinops.

5 Pharmacological effects of metabolites produced by fungal endophytes derived from Aquilaria and Gyrinops

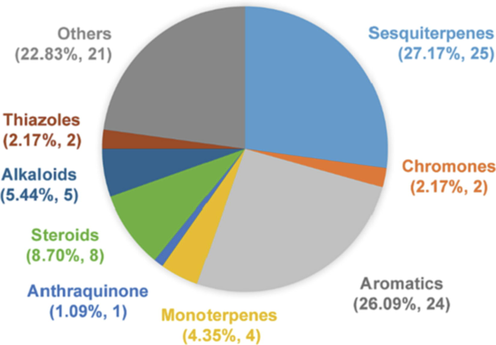

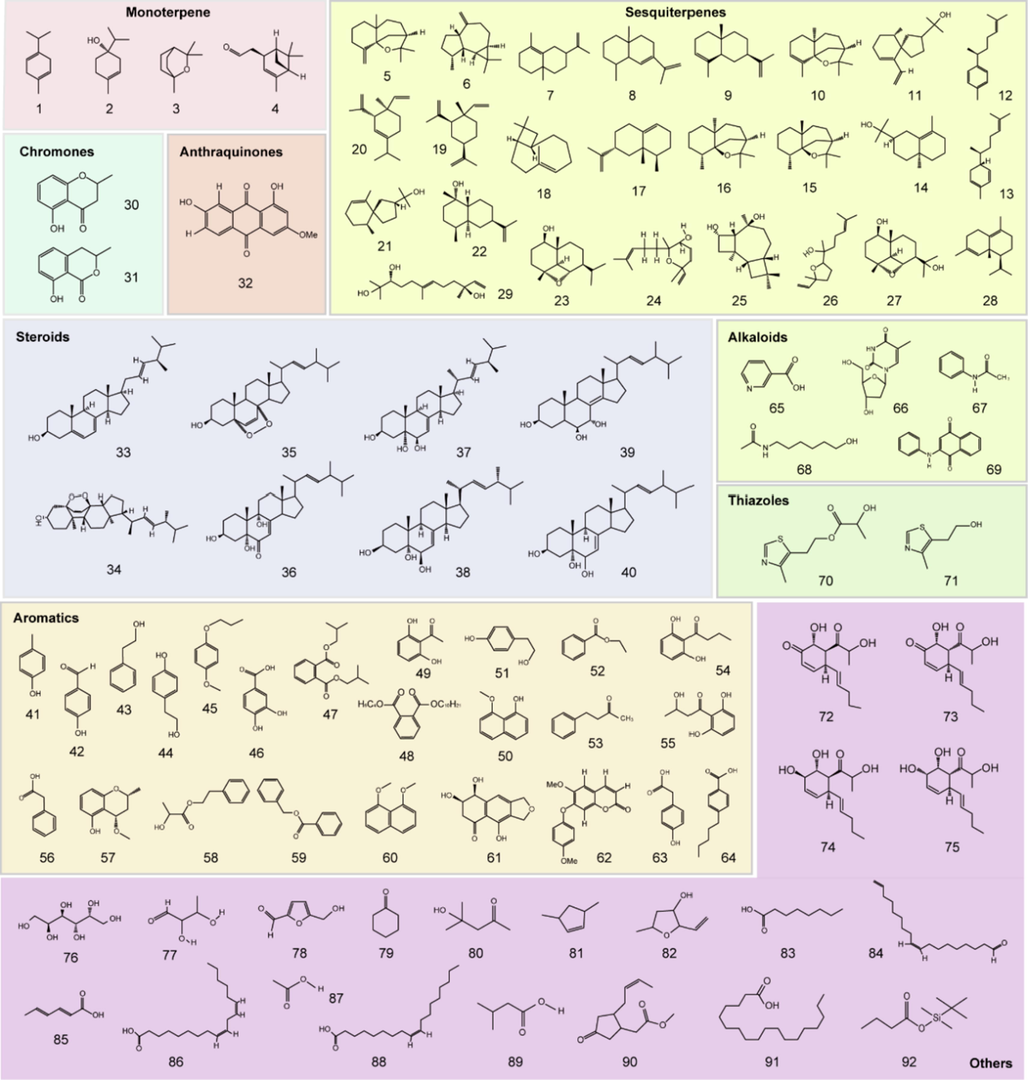

Endophytic fungi can be one of the best-known sources of natural products, while the endophytic fungi present in Aquilaria and Gyrinops tree, in the process of agarwood formation, were also recognized as the new sources of secondary metabolites, which hold pharmaceutical and ecological significance. A total of 92 compounds were recorded from the endophytes of Aquilaria and Gyrinops trees, including terpenoids (40.22 %: containing monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and steroids), aromatics (26.09 %), alkaloids (5.44 %), chromones (2.17 %), and others (Fig. 2, Table 3). Interestingly, some endophytes of Aquilaria and Gyrinops could produce sesquiterpenes which were the important compounds of agarwood (Fig. 3, Table 3). Acremonium sp., Arthrinium sp., Collectotrichum sp., Diaporthe sp., Fimetariella rabenhorstii, Nemania sp., Nigrospora oryzae, and Nodulisporium sp. are responsible for the production of sesquiterpenes (Li et al., 2014; Monggoot et al., 2017; Tao et al., 2011a; Tibpromma et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2009b). Thus, those fungal stains were considered to be the potential materials for fermenting agarwood compounds. Bioactivity: the effects of the fungal endophytes; Pharmacological values: the functions of the compounds produced by the fungi.

The categories of 92 compounds produced by the endophytes of Aquilaria and Gyrinops.

No.

Compounds

Molecular Formula

Pharmacological Values

Fungal Endophytes

Host Plant

References

Monoterpenes

1

γ-Terpinene

C10H16

Trypanocidal effect

Acaricidal activity

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Tibpromma et al., 2021;Zhang et al., 2009b

2

Terpinen-4-ol

C10H18O

---

Arthrinium sp.

Collectotrichum sp.A. subintegra

Monggoot et al., 2017

3

1,8-Cineole

C10H18O

Antibacterial activity

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Wang et al., 2007;Zhang et al., 2009b

4

Bicyclo[3.1.1]hept-3-ene-2-acetaldehyde, 4,6,6-trimethyl,

C12H18O

---

Nemania aquilariae

A. sinensis

Tibpromma et al., 2021

Sesquiterpenes

5

β-Agarofuran

C15H24O

---

Collectotrichum sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Monggoot et al., 2017

6

Alloaromadendrene

C15H24

Anti-oxidant activity

Cytotoxic activity

Anti-feedant activity

Anti-proliferative activityNemania aquilariae

A. sinensis

Baldissera et al.,2016Jesionek et al, 2018Sawant et al., 2007Yu et al.,2014

7

1,2,3,4,4α,5,6,7-Octahydro-4α,8-dimethyl-2-(1-methylethenyl)-naphthalene

C15H24

---

Nemania aquilariae

A. sinensis

Baldissera et al., 2016

8

Z-Eudesma-6,11-diene

C15H24

---

Arthrinium sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Capello et al., 2015Monggoot et al., 2017

9

α-Selinene

C15H24

Anti-cancer activity

Repellent activityNemania aquilariae

A. sinensis

Alakanse et al., 2019Baldissera et al., 2016Mauti et al.,2019

10

α-Agarofuran

C15H24O

Antianxiety activity

Arthrinium sp.

Collectotrichum sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Monggoot et al., 2017Peeraphong et al., 2021Zhang et al., 2004

11

Oxo-agarospirol

C15H24O2

Antioxidant activity

Arthrinium sp.

Collectotrichum sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Capello et al., 2015Monggoot et al., 2017

12

Ar-Curcumene

C15H22

Mosquito larvicides

Anti-inflammatory activity

Anti-ulcer activity

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007Podlogar et al., 2012Yamahara et al.,1992Zhang et al., 2009b

13

Zingiberene

C15H24

Anti-inflammatory activity

Anti-apoptotic effect

Anti-oxidant activity

Anti-cancer activity

Cytotoxicity, Genotoxicity

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007Li et al., 2021Togar et al., 2015Türkez et al., 2014Zhang et al., 2009b

14

10-epi-γ-Eudesmol

C15H26O

Prevention of mosquito-related disease

Collectotrichum sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Capello et al., 2015(Kracht et al., 2019)

15

cis-Dihydroagarofuran

C15H26O

Antimicrobial activity

Diaporthe sp.

A. subintegra

Capello et al., 2015Sadgrove et al., 2015

16

β-Dihydroagarofuran

C15H26O

---

Arthrinium sp.

Collectotrichum sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Capello et al., 2015Monggoot et al., 2017

17

Valencen

C15H24

---

Nemania aquilariae

A. sinensis

Baldissera et al., 2016

18

Z-Caryophyllene

C15H24

---

Arthrinium sp.

Collectotrichum sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Capello et al., 2015Monggoot et al., 2017

19

β-Elemene

C15H24

High cytotoxic activity

Diaporthe sp.

A. subintegra

Capello et al., 2015Monggoot et al., 2017

20

δ-Elemene

C15H24

---

Collectotrichum sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Capello et al., 2015Monggoot et al., 2017

21

Agarospirol

C15H26O

Anti-nociceptive activitiy

Anti-oxidant activity

Collectotrichum sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Capello et al., 2015Monggoot et al., 2017Okugawa et al., 1996

22

rel-(1S,4S,5R,7R,10R)-10-Desmethyl-1-methyl-11-eudesmene

C15H26O

Cytotoxic activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Li et al., 2011

23

Capitulatin B

C15H26O2

---

Nigrospora oryzae

A. sinensis

Zhang et al., 2004

24

6α-Hydroxycyclonerolidol

C15H26O2

Cytotoxic activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Li et al., 2011

25

Frabenol

C15H26O2

---

Fimetariella rabenhorstii

A. sinensis

Tao et al., 2011a

26

6-Methyl-2-(5-methyl-5-vinyltetrahydrofuran-2-yl) hept-5-en-2-ol

C15H26O2

---

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Li et al., 2011

27

11-Hydroxycapitulation B

C15H26O3

---

Nigrospora oryzae

A. sinensis

Zhang et al., 2004

28

δ-Eudesmol

C15H28O

Prevention of mosquito-related disease

Arthrinium sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Capello et al., 2015(Kracht et al., 2019)

29

(3R,6E,10S)-2,6,10-Trimethyl-3-hydroxydodeca-6,11-diene-

C15H28O3

---

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

A. sinensis

Liu et al., 2018

Chromones

30

2,3-Dihydro-5-hydroxy-2-methylchromen-4-one

C10H10O3

Cytotoxic activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Wu et al., 2010

31

Mellein

C10H10O3

Antibacterial activity

Aspergillus sp.

A. sinensis

Peng et al., 2011

Anthraquinones

32

1,7-Dihydroxy-3-methoxyanthraquinone

C15H10O5

Anti-bacterial activity

Unknown fungal strain AL-2

A. malaccensis

Blakeney et al., 2019Shoeb et al., 2010

Steroids

33

Ergosterol

C28H44O

Anti-inflammatory activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Kobori et al., 2007Li et al., 2011

34

Ergosterol peroxide

C28H44O3

Induced apoptosis of cells

Anti-inflammatory activity

Cytotoxic activity

Anti-oxidant activities

Anti-complementary activity

Trypanocidal activity

Antibacterial activity

Anti-proliferative activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Li et al., 2011Takei et al.,2005Kobori et al., 2007Nam et al., 2001Kim et al., 1999Kim et al., 1997Ramos-Ligonio et al., 2012Duarte et al., 2007Nowak et al., 2016

35

5α,8α-Epidioxy-(22E,24R)-ergosta-6,22-dien-3β-ol

C28H44O3

Anti-tumor activity

Fimetariella rabenhorstii

A. sinensis

Li, 2016Plotnikov et al., 2021Tanapichatsakul et al., 2020Nam et al., 2001Kim et al., 1999

36

3β,5α,9α-Trihydroxy-(22E,24R)-ergosta-7,22-dien-6-one

C28H44O3

Anti-tumor activity

Fimetariella rabenhorstii

A. sinensis

Li, 2016Plotnikov et al., 2021Takei et al., 2005

37

Cerevisterol

C28H46O3

Anti-microbial activity

Resistance modifying activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Li et al., 2011Appiah et al., 2020

38

(3β,5α,6β,22E)-Ergosta-7,22-diene-3,5,6-triol

C28H46O3

---

Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum

A. sinensis

Ribeiro et al., 2007

39

3β,6β,7α-Trihydroxy-(24R)-ergosta-8(14),22-diene

C28H46O3

---

Fimetariella rabenhorstii

A. sinensis

Li, 2016Plotnikov et al., 2021

40

3β,5α,6β-Trihydroxy-(22E,24R)-ergosta-7,22-diene

C28H46O3

Anti-tumor activity

Fimetariella rabenhorstii

A. sinensis

Li, 2016Plotnikov et al., 2021Kobori et al., 2007Kim et al.,1997

Aromatics

41

Methylphenol

C7H8O

Antibacterial activity

Fimetariella rabenhorstii

Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum

A. sinensis

Li, 2016Wei et al., 2011

42

p-Hydroxybenzaldehyde

C7H6O2

Anti-oxidative activity

Blood-brain barrier

ToxicityPhaeoacremonium rubrigenum

A. sinensis

Ribeiro et al., 2007Kinjo et al., 2020Borneman et al., 1986Wei et al., 2011

43

Phenylethyl alcohol

C8H10O

Antibacterial

Sedative effects

Antifungal activity

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al.,2007Lilley and Brewer, 1953Oshima and Ito, 2021Boukaew and Prasertsan, 2018Zhang et al., 2009b

44

4-Hydroxyphenyl ethyl alcohol

(Tyrosol; 4-Hydroxy-benzeneethanol)C8H10O2

Nematicide

Antioxidant activity

Anti-inflammatory activity

Fimetariella rabenhorstii

Acremonium sp.

Nodulisporium sp.A. sinensis

Tao et al., 2011bDuarte et al.,2007Li et al.,2018Zhang et al., 2009bLi et al., 2011Wei and Liu, 2007Tao et al., 2011b

45

6-Methoxy-7-O-(p-methoxyphenyl)-coumarin

C17H14O5

---

Unkonw fungal strain AL-2

A. malaccensis

Blakeney et al., 2019

46

3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid

C7H6O4

Antibacterial activity

Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum

A. sinensis

Ribeiro et al., 2007

47

Phthalic acid diisobutyl ester

C16H22O4

Phytotoxicity

Testicular atrophyColletotrichum gloeosporioides

A. sinensis

Appiah et al., 2020Huang et al.,2021Oishi et al.,1980

48

Decyl butyl phthalate

C22H34O4

---

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007

49

1-(2,6-Dihydroxyphenyl) ethanone

C8H8O3

Cytotoxic activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Wu et al., 2010

50

8-Methoxynaphthalen-1-ol

C11H10O2

Antifungal activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Li et al, 2011;Takei et al., 2005

51

p-Hydroxyphenethyl alcohol

C8H10O2

Antibacterial activity

Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum

A. sinensis

Wei et al., 2011

52

Ethyl benzoate

C9H10O2

---

Arthrinium sp.

Collectotrichum sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Monggoot et al., 2017

53

Phenyl butanone

C10H12O

---

Collectotrichum sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Monggoot et al., 2017

54

1-(2,6-Dihydroxyphenyl) butan-1-one

C10H12O3

Cytotoxic activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Wu et al., 2010

55

1-(2,6-Dihydroxyphenyl)-3-hydroxybutan-1-one

C10H12O4

Cytotoxic activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Wu et al., 2010

56

Benzeneacetic acid

C8H8O2

---

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007

57

(2R*,4R*)-3,4-Dihydro-4-methoxy-2-methyl-2H-1-benzopyran-5-ol

C11H14O3

Cytotoxic activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Wu et al., 2010

58

Phenethyl 2-hydroxypropanoate

C11H14O3

---

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

A. sinensis

Liu et al., 2018

59

Benzyl benzoate

C14H12O2

Treatment of scabies

Arthrinium sp.

Diaporthe sp.A. subintegra

Monggoot et al., 2017;Li et al., 2011

60

1,8-Dimethoxynaphthalene

C12H12O2

---

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Li et al., 2011

61

(7R*,8S*)-3,6,7,8-Tetrahydro-4,7,8-trihydroxynaphtho [2,3-

C12H12O5

Cytotoxic activity

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Wu et al, 2010

62

Propyl p-methoxy phenyl ether

C10H14O2

---

Unkonw fungal strain AL-2

A. malaccensis

Shoeb et al., 2010

63

p-Hydroxyphenylacetic acid

C8H8O3

---

Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum

A. sinensis

Ribeiro et al., 2007

64

4-Pentylbenzoic acid

C12H16O2

---

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007

Alkaloids

65

Nicotinic acid

C6H5NO2

Prevention of atherosclerosis and reduce the risk of cardiovascular events

Fimetariella rabenhorstii

A. sinensis

Okugawa et al., 1996(Gille et al., 2008)

66

Thymidine

C10H14N2O5

Anti-cancer activity

Anti-metabolites activityPhaeoacremonium rubrigenum

A. sinensis

Ribeiro et al., 2007Stokes and Lacey, 1978Martin et al., 1980O'Dwyer et al, 1987

67

N-Phenylacetamide

C8H9NO

Cytotoxic activity

Fimetariella rabenhorstii

A. sinensis

Okugawa et al.,1996

68

N-(6-Hydroxyhexyl)-acetamide

C8H17O2N

Antibacterial activity

Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum

A. sinensis

Ribeiro et al., 2007

69

2-Anilino-1,4-naphthoquinone

C16H11NO2

Anti-fungal activity

Fimetariella rabenhorstii

A. sinensis

Okugawa et al.,1996(Leyva et al., 2017)

Thiazoles

70

Colletotricole A

C9H13NO3S

---

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

A. sinensis

Appiah et al., 2020

71

2-(4-Methylthiazol-5-yl)ethyl 2-hydroxypropanoate

C9H13O3NS

---

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

A. sinensis

Appiah et al., 2020

Others

72

Colletotricone A

C14H20O4

Anti-tumour activity

Cytotoxic activityColletotrichum gloeosporioides

A. sinensis

Appiah et al., 2020Kim et al., 2019Liu et al., 2018

73

Colletotricone B

C14H20O4

---

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

A. sinensis

Liu et al., 2018

74

Nigrosporanene A

C14H20O4

Cytotoxicity

Radical scavenging activityColletotrichum gloeosporioides

A. sinensis

Appiah et al., 2020Liu et al., 2018Ma and Qi, 2019

75

Nigrosporanene B

C14H22O4

Radical scavenging activity

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides

A. sinensis

Appiah et al., 2020Liu et al., 2018Ma and Qi, 2019

76

d-Galacitol

C6H14O6

---

Fimetariella rabenhorstii

A. sinensis

Tao et al., 2011b

77

2,3-Dihydroxybutane

C4H8O3

---

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Zhang et al., 2009b

78

5-Hydroxymethylfurfural

C6H6O3

Antibacterial activity

Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum

A. sinensis

Wei et al., 2011

79

Cyclohexanone

C6H10O

---

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Zhang et al., 2009b

80

4-Hydroxy-4-methyl-2-phentanone

C6H12O2

---

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Zhang et al., 2009b

81

3,5-Dimethyl cyclopentenolone

C7H11O2

---

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Zhang et al., 2009b

82

5-Methyl-2-vinyltetrahydrofuran-3-ol

C7H12O2

---

Nodulisporium sp.

A. sinensis

Li et al., 2011

83

Octanoic acid

C8H16O2

Toxicity

Reducing the magnitude of tremor

Anti-tumor activity

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007Viegas et al., 1995Lowell et al., 2019Altinoz et al., 2020

84

(Z)-9,17-Octadecadienal

C18H32O

---

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007

85

Sorbic acid

C6H8O2

Anti-fungal activity

Anti-microbial activity

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007Razavi‐Rohani and Griffiths, 1999Eklund et al., 1983

86

Linoleic acid

C18H32O2

Pro-inflammatory activity

Anti-cancer activity

Cholesterol and blood pressure lowering effects

Epidermal permeability barrier

Anaerobic degradability

Inhibitory effects

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007Young et al., 1998Burns et al., 2018Lalman et al., 2000Elias et al., 1980

87

Acetic acid

C2H4O2

---

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007

88

Oleic acid

C18H34O2

Anti-tumor

Anti-inflammatory

Anti-bactericidal

Vasculoprotective effects

Pro-inflammatory

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007(Carrillo Pérez et al., 2012)

Sales-Campos et al., 2013Speert et al., 1979Massaro et al., 2002Young et al., 1998

89

Isovaleric acid

C5H10O2

Reduces Na+, K+-ATPase activity

Causes colonic smooth muscle relaxation

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007Ribeiro et al., 2007Blakeney et al., 2019

90

Methyl jasmonate

C12H18O3

Against pathogens

Salt stress

Drought stress

Low temperature

Heavy metal stress and toxicities of other elementsLasiodiplodia theobromae

A. sinensis

Han et al., 2014Yu et al., 2018

91

Octadecanoic acid

C18H36O2

---

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007

92

Butanoic acid

C10H22O2Si

---

Acremonium sp.

A. sinensis

Duarte et al., 2007

The structures of 92 compounds produced by the endophytes of Aquilaria and Gyrinops.

Endophytic fungi in agarwood-producing trees can also be a rich source of medicinal agents with various pharmacological properties (Chhipa et al., 2017). The majority of endophytes derived from Aquilaria showed both antimicrobial and antitumor activities simultaneously, including Cladosporium tenuissimum, Coniothyrium nitidae, Epicoccum nigrum, Fusarium equiseti, Fusarium oxysporum, Fusarium solani, Hypocrea lixii, Lasiodiplodia theobromae, Leptosphaerulina chartarum, Paraconiothyrium variabile, Phaeoacremonium rubrigenum, Rhizomucor variabilis, and Xylaria mali (Cui et al., 2011). However, few of them were reported to display only antimicrobial activities, i.e. Phoma herbarum, Geotrichum candium, and Fusarium verticillioides (Chi et al., 2016; Cui et al., 2011). The endophytic fungi, Diaporthe sp. and Colletotrichum sp., which were believed to be responsible for the production of sesquiterpene compounds in Aquilaria trees, were claimed to have antioxidant properties; while the latter taxa also came with anti-inflammatory activities (Monggoot et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016). Although a total of 92 compounds produced by fungal endophytes in Aquilaria were identified so far (Fig. 3), only 52 of them were proven to come with their related biological properties; in general, most of the identified compounds contained anti-inflammatory, anti-bacterial, and anti-cancer properties (Table 3). Compounds produced by all the isolated endophytes from Aquilaria and Gyrinops and their pharmacological values have been shown in Table 3.

6 Conclusion

Endophytes could maintain endosymbiotic relationship within plants at least in one stage of their life cycle (Turjaman et al., 2016). Compared with physical and chemical methods, the use of endophytic fungi has been recognized as a safe method to promote agarwood production for the environment and human health (Tan et al., 2019). Additionally, the endophyte inducing method could be seemed as a prioritized approach to enhance agarwood formation due to its ability to produce the signals associated with continuous agarwood formation and compounds with bioactivity. And the advantages of induced agarwood by endophytes are more pharmaceutical values, higher environmental adaptability, and faster speed of agarwood formation.

To our knowledge, 14 species of Aquilaria and eight of Gyrinops were known to produce agarwood, and different fungal species and abundances were detected because of different planting regions and various species. Fusarium sp. accounted for the largest proportion of Aquilaria and Gyrinops, followed by Colletotrichum sp., Diaporthe sp., and Trichoderma sp. The endophytic fungi spread over various host species with high biodiversity, however, the biodiversity of fungal endophytes distributed in various planting areas is seldom reported, which needs more detailed research. Furtherly, the variation in microbiome composition is represented by multiple A. sinensis tree host organs, and tissue types. The high diversity of fungal endophytes in resinous wood could give some good candidates for developing fungal inoculum that could promote agarwood production.

Various endophytic fungi have been reported to produce metabolites containing sesquiterpenoids and aromatic groups, which are a rich source of medicinal agents to improve the quality and quantity of agarwood. Most of the endophytes from Aquilaria and Gyrinops showed antimicrobial and antitumor activities, and a few fungi that have special abilities, such as the antioxidant activity of Diaporthe sp., and anti-inflammatory activities of Colletotrichum sp. Besides that, some of the secondary metabolites are formed when the fungal endophytes trigger the self-defense reaction of Aquilaria and Gyrinops. In this way, the agarwood fungal endophytes not only protect host trees from microbe invasions and diseases but also activate the accumulation of agarwood. And these compounds produced by the fungal strains are various due to the different species or strains, which might enhance the resistance abilities to various environmental stresses. Conversely, both Aquilaria and Gyrinops trees grow in different places with various geographic and climate conditions and need different sorts of fungi, which could promote the host’s ecological adaptability. In summary, the fungal endophytes on the host trees of Aquilaria and Gyrinops are responsible for activating the plant defense system, strengthening the hosts’ ecological adaptability, and enhancing agarwood production, which may be the reasons why agarwood artificial induction by endophytes has become popular. The mechanism of aroma accumulation and the crucial role of endophytes in the agarwood host trees need to be furtherly explored in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public Welfare Research Institutes (grant no. ZZ13-YQ-093-C1, ZZXT202112), and the CACMS Innovation Fund (Grant No. CI2021A04101).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- α-Selinene from Syzygium aqueum against aromatase P450 in breast carcinoma of postmenopausal women: in silico study. J. Biomed. Pharm. Sci.. 2019;2:1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Caprylic (Octanoic) acid as a potential fatty acid chemotherapeutic for glioblastoma. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids. 2020;159:102142

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial and resistance modifying activities of cerevisterol isolated from Trametes species. Curre. Bioact. Compd.. 2020;16:115-123.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of crown pruning and induction of Acremonium sp. on agarwood formation in Gyrinops caudata in West Papua, Indonesia. Biodivers. J. Biol. Divers.. 2021;22:2604-2611.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro and in vivo action of terpinen-4-ol, γ-terpinene, and α-terpinene against Trypanosoma evansi. Exp. Parasitol.. 2016;162:43-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- On the formation and development of agaru in Aquilaria agallocha. Sci. Cult.. 1952;18:240-243.

- [Google Scholar]

- Branched short-chain fatty acid isovaleric acid causes colonic smooth muscle relaxation via cAMP/PKA pathway. Dig. Dis. Sci.. 2019;64:1171-1181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette, R.A., 2003. Agarwood formation in Aquilaria trees: resin production in nature and how it can be induced in plantation grown trees. In: Notes from presentation at first international agarwood conference, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 10–15.

- Effect of phenolic monomers on ruminal bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.. 1986;52:1331-1339.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory effects of acetophenone or phenylethyl alcohol as fumigant to protect soybean seeds against two aflatoxin-producing fungi. J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2018;55:5123-5132.

- [Google Scholar]

- Differentiating the biological effects of linoleic acid from arachidonic acid in health and disease. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids. 2018;135:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and in vitro cytotoxic and antileishmanial activities of extract and essential oil from leaves of Piper cernuum. Nat. Prod. Commun.. 2015;10:285-288.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antitumor effect of oleic acid; mechanisms of action. a review. Nutr. Hosp.. 2012;27:1860-1865.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trunk surface agarwood-inducing technique with Rigidoporus vinctus: an efficient novel method for agarwood production. PLoS One. 2018;13:0198111.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and identification of endophytic fungi which promote agarwood formation in Aquilaria sinensis. Chin. Pharm. J.. 2014;49(13):1118-1120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Agarwood formation induced by fermentation liquid of Lasiodiplodia theobromae, the dominating fungus in wounded wood of Aquilaria sinensis. Curr. Microbiol.. 2017;74:460-468.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Fomitopsis sp. on promoting agarwood formation and its biological characteristics. Mod. Chin. Med.. 2017;19(8):1097-1101.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of fungi diversity in agarwood wood from Hainan province and Guangdong province. Chin. Pharm. J.. 2019;54:1933-1938.

- [Google Scholar]

- Artificial production of agarwood oil in Aquilaria sp. by fungi: a review. Phytochem. Rev.. 2017;16:835-860.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological characterization of fungi endophytes isolated from agarwood tree Aquilaria crassna Pierre ex Lecomte. Tạp chí Công nghệ Sinh học. 2016;14:149-156.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endophytic fungi and their metabolites isolated from Indian medicinal plant. Phytochem. Rev.. 2012;11:467-485.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Status of agar (Aquilaria agallocha Roxb.) based small-scale cottage industries in Sylhet region of Bangladesh. Bangladesh J. Resour. 2003:1-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gyrinops ledermannii (Thymelaeaceae), being an agarwood-producing species prompts call for further examination of taxonomic implications in the generic delimitation between Aquilaria and Gyrinops. Flora Males. Bull.. 2002;13:61-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Populus holobiont: dissecting the effects of plant niches and genotype on the microbiome. Microbiome 2018:6-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antitumor and antimicrobial activities of endophytic fungi from medicinal parts of Aquilaria sinensis. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 2011;12(5):385-392.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of inoculating fungi on agarwood formation in Aquilaria sinensis. Chin. Sci. Bull.. 2013;58:3280-3287.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of the complete chloroplast genome of Aquilaria sinensis, an endangered agarwood-producing tree. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour.. 2020;5:422-423.

- [Google Scholar]

- Three new 2-(2-phenylethyl) chromone derivatives of agarwood originated from Gyrinops salicifolia. Molecules. 2019;24(3):576.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activity of ergosterol peroxide against Mycobacterium tuberculosis: dependence upon system and medium employed. Phytother. Res.: Int. J. Devoted Pharmacol. Toxicol. Eval. Nat. Prod. Derivatives. 2007;21:601-604.

- [Google Scholar]

- The antimicrobial effect of dissociated and undissociated sorbic acid at different pH levels. J. Appl. Bacteriol.. 1983;54:383-389.

- [Google Scholar]

- The permeability barrier in essential fatty acid deficiency: evidence for a direct role for linoleic acid in barrier function. J. Invest. Dermatol.. 1980;74:230-233.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fusarium solani induces the formation of agarwood in Gyrinops versteegii (Gilg.) Domke branches. Symbiosis. 2020;81:15-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Faizal, A., Esyanti, R.R., Adn′ain, N., Rahmani, S., Azar, A.W.P., Iriawati, Turjaman, M., 2021. Methyl jasmonate and crude extracts of Fusarium solani elicit agarwood compounds in shoot culture of Aquilaria malaccensis Lamk. Heliyon, e06725

- Evaluation of biotic and abiotic stressors to artificially induce agarwood production in Gyrinops versteegii (Gilg.) Domke seedlings. Symbiosis. 2022;86:229-239.

- [Google Scholar]

- Notes on the distribution and ecology of Aquilaria lam. (Thymelaeaceae) in Malaysia. Malaysian Fores.. 2009;72(2):247-259.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary study on endophytic fungi of Aquilaria sinensis. Nanchang: Jiangxi University; 2008.

- Nicotinic acid: pharmacological effects and mechanisms of action. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol.. 2008;48:79-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endophytic fungi from Dracaena cambodiana and Aquilaria sinensis and their antimicrobial activity. Biotechnol.. 2009;8(5):731-736.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Thymelaeacean under ihrer natürlichen Umgrenzung. Meded. Rijks-Herb. 1992;44:1-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of production of sesquiterpenes of Aquilaria sinensis stimulated by Lasiodiplodia theobromae. Chin. J. Chin. Mater. Med.. 2014;39:192-196.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioactive composition, antifungal, antioxidant, and anticancer potential of agarwood essential oil from decaying logs (Gyrinops spp.) of Papua Island (Indonesia). Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical. Science. 2021;11(10):070-078.

- [Google Scholar]

- Notes on some Asiatic species of Aquilaria (Thymelaceae) Blumea. 1964;12(2):285-288.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and screening of endophytic fungi from the resin part of Aquilaria sinensis. Jiangsu Agric. Sci.. 2017;45(20):285-289.

- [Google Scholar]

- Historical records and modern studies on agarwood production method and overall agarwood production method. China J. Chin. Mater. Med.. 2013;38(3):302-306.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phthalic acid esters: Natural sources and biological activities. Toxins. 2021;13(7):495.

- [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. 2022. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2021-3.

- Validated HPTLC method for determination of ledol and alloaromadendrene in the essential oil fractions of Rhododendron tomentosum plants and in vitro cultures and bioautography for their activity screening. J. Chromatogr. B. 2018;1086:63-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- A friendly relationship between endophytic fungi and medicinal plants: a systematic review. Front. Microbiol.. 2016;7:906.

- [Google Scholar]

- Jong, P.L., 2012. Effects of mechanical wounding and infection patterns of Fusarium solani on gaharu formation in Aquilaria malaccensis Lam. Master Dissertation, Faculty of Forestry, Universiti Putra Malaysia.Kalra, R., Kaushik, N., 2017. A review of chemistry, quality and analysis of infected agarwood tree (Aquilaria sp.). Phytochem. Rev. 16, 1045–1079

- Anticancer compounds derived from fungal endophytes: their importance and future challenges. Nat. Prod. Rep.. 2011;28(7):1208-1228.

- [Google Scholar]

- A New Species of Aquilaria (Thymelaeaceae) from Vietnam. Blumea-Biodivers. Evol. Biogeogr. Plants. 2005;50(1):135-141.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticomplementary activity of ergosterol peroxide from Naematoloma fasciculare and reassignment of NMR data. Arch. Pharm. Res.. 1997;20:201-205.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity of ergosterol peroxide (5,8-epidioxy-5α,8α-ergosta-6,22E-dien-3β-ol) in Armillariella mellea. Bull. Kor. Chem. Soc.. 1999;20:819-823.

- [Google Scholar]

- The fungus Colletotrichum as a source for bioactive secondary metabolites. Arch. Pharm. Res.. 2019;42:735-753.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of p-hydroxybenzaldehyde and p-hydroxyacetophenone from non-centrifuged canesugar, kokuto, on serum corticosterone, and liver conditions in chronically stressed mice fed with a high-fat diet. Food Sci. Technol. Res.. 2020;26:501-507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ergosterol peroxide from an edible mushroom suppresses inflammatory responses in RAW264. 7 macrophages and growth of HT29 colon adenocarcinoma cells. Br. J. Pharmacol.. 2007;150:209-219.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discovery of three novel sesquiterpene synthases from Streptomyces chartreusis NRRL 3882 and crystal structure of an α-eudesmol synthase. Journal of biotechnology. 2019;297:71-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discovery of three novel sesquiterpene synthases from Streptomyces chartreusis NRRL 3882 and crystal structure of an α-eudesmol synthase. Journal of biotechnology. 2019;297:71-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Endophytic fungi isolated from oilseed crop Jatropha curcas produces oil and exhibit antifungal activity. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e56202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anaerobic degradation and inhibitory effects of linoleic acid. Water Res.. 2000;34:4220-4228.

- [Google Scholar]

- The origin and domestication of Aquilaria, an important agarwood-producing genus. In: Book: Agarwood. Springer Singapore: Tropical Forestry; 2016. p. :1-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic relatedness of several agarwood-producing taxa (Thymelaeaceae) from Indonesia. Trop. Life Sci. Res.. 2018;29(2):13-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic relationships of Aquilaria and Gyrinops (Thymelaeaceae) revisited: evidence from complete plastid genomes. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. Lond. 2022:boac014.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and studies of the antifungal activity of 2-anilino-/2, 3-dianilino-/2-phenoxy-and 2, 3-diphenoxy-1, 4-naphthoquinones. Research on Chemical Intermediates. 2017;43(3):1813-1827.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study on secondary metabolites of endophytic fungus strain Fusarium solani A2 and Fimetariella rabenhorstii A20 from Aquilariae Lignum Resinatum. Guangdong Pharmaceutical University; 2016. p. :41-45. MS thesis

- Two new octahydro naphthalene derivatives from Trichoderma spirale, an endophytic fungus derived from Aquilaria sinensis. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2012;95(5):805-809.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effect of zingiberene on isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in experimental animals. Hum. Exp. Toxicol.. 2021;40:915-927.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory effects of components from root exudates of Welsh onion against root knot nematodes. PLoS One. 2018;13(7):e0201471.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents of endophytic fungus Nodulisporium sp. A4 from Aquilaria sinensis. Chin. J. Chin. Mat. Med.. 2011;36:3276-3280.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new eudesmane sesquiterpene from Nigrospora oryzae, an endophytic fungus of Aquilaria sinensis. Rec. Nat. Prod.. 2014;8:330-333.

- [Google Scholar]