Translate this page into:

Antibacterial effect, efflux pump inhibitory (NorA, TetK and MepA) of Staphylococcus aureus and in silico prediction of α, β and δ-damascone compounds

⁎Corresponding authors. hdmcoutinho@gmail.com (Henrique Douglas Melo Coutinho), joseraduan.jaber@ulpgc.es (José Raduan Jaber), irwin.alencar@urca.br (Irwin Rose Alencar de Menezes)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Objective

The present study aimed to evaluate the antibacterial effect and inhibitory capacity against NorA, TetK and MepA efflux pump of Staphylococcus aureus multiresistant by in vitro and in silico approach of α, β and δ-damascone compounds.

Results

The compounds α, β and δ-damascone showed a clinically relevant effect against S. aureus ATCC 6538 standard strain. A modulating effect was also observed in association with antibiotics against MDR strains. Regarding the inhibition of the efflux pump, the compounds showed a modulating effect with antibiotics, against SA-1199, SA-1199B, SA IS-58 and K2068. Only δ-damascone demonstrated an efflux pump inhibitory effect. Regarding ADME properties, α, β and δ-damascone showed similar physicochemical properties with good pharmacokinetic characteristics, such as lipophilicity, oral bioavailability and low toxicity. In addition, they exhibited the binding energy and Ligand Efficiency (LE) −81.17 (5.4), −77.48(-5.4) and −64.55 (-5.1), which shows good interactions with the critical residues of the MepA receptor.

Conclusions

From the results it is concluded that the compounds α, β and δ-damascone do not have antibacterial activity, but show a modulating effect in association with antibiotics, as well as not showing direct activity on the efflux pump, but they do have a modulating effect with antibiotics and with EtBr (α and β-damascone).

Keywords

Antibacterial

Damascone

Efflux pump

ADME

Molecular docking

1 Introduction

The discovery of antibiotics helps in the treatment and control of infections. However, infections are still one of the biggest causes of mortality. This is due to the emergence of new diseases, the recurrence of diseases that are already under control, as well as microbial resistance. (Kapoor et al., 2017). Microbial resistance is related to microorganisms such as bacteria, fungi, viruses, and parasites. This phenomenon occurs when existing growth in the presence of drugs that would generally have deleterious effects on these microorganisms. This is due to different resistance mechanisms: modification of the drug target, efflux pump, hydrolysis or enzymatic degradation, and impermeability (Founou et al., 2017). With regard to resistant bacteria, the Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) which is commensal, gram-negative and can become an opportunistic pathogen when there are favorable factors, such as failure of tissue barriers or weakness in the immune system (Lee and Zhang, 2015). Escherichia coli (EC) is gram-negative and responsible for complications in the gastrointestinal tract, potentially leading to death (Yingst et al., 2006) as well as urinary tract infections (UTI) (Rayasam et al., 2019). Staphylococcus aureus (SA), is gram-positive, which is present in the human microbiota as a commensal (Lee et al., 2018). However, they can lead to serious infections such as: osteoarticular, skin and soft tissue infections, bacteremia and infective endocarditis (dos Santos et al., 2007; Tong et al., 2015).

Regarding the mechanisms that can lead to resistance in bacteria, the efflux pump are pointed out, which reduces the intracellular concentration of antibiotics (Piddock, 2006) and occurs in gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (Kumar and Pooja Patial, 2016). They are classified into five families: major facilitator superfamily (MSF), resistance nodulation and cell division (RND), ATP binding cassette (ABC), small multidrug resistance family (family-SMR) e multidrug and toxic compound extrusion family (MATE) (Piddock, 2006; Schindler et al., 2013a).

The bacteria resistance in Gram-positive bacteria can be found by the expression of Efflux pumps present in chromosomes or plasmids. The most common efflux pumps found in chromosomes of this bacteria class are NorA, NorB, NorC, MdeA, SepA, MepA, and SdrM, and pumps transfected by plasmids are: qacA /B, qacG, qacH, qacJ and smr (Hassanzadeh et al., 2020, 2017). While for Gram-negative bacteria, we can mention AcrAB–TolC, MexAB–OprM (Pagès et al., 2005) and NorM (Rouquette-loughlin et al., 2003) as the most prevalent efflux pumps that relation to multiresistant phenotypic.

In the search for possible antimicrobial agents with a broad spectrum of activity, there are products of natural origin (da Silva Santos et al., 2017), and secondary metabolites are included because they often act with interaction mechanism, defense and biological properties (Shitan, 2016; Wink, 2010). In this sense, norisopreoids are a class of aromatic compounds, derived from carotenoids, which is composed of ionones and damascones (Litzenburger and Bernhardt, 2016). These have thirteen carbons, and are present in the constitution of the aroma of teas, grapes, roses, tobacco and wine, in addition to flavors and fragrances, being very important in industrial chemical products (Serra, 2015).

Damascones were discovered in the work of (Demole et al., 1970)) (Demole et al., 1970) in the oil of the Bulgarian rose (Rosa damascena Mill), which are known as rose ketones, with applications in the fragrance and cosmetics industry (Gliszczyńska et al., 2016). Chemically, they are isomers of ionones. However, according to the position of the double bond, there are several other isomers, from which the α, β and δ-damascone come with greater economic importance (Surburg and Panten, 2016).

Regarding biological activities, according to research conducted by the Research Institute for Fragrance Materials Inc (RIFM), α-damascone showed no mutagenic activity against E. coli and Salmonella Typhimurium strains (Lapczynski et al., 2007). β-damascone has been shown in in vitro studies to reduce quinone reductase (IP-10) (Gerhäuser et al., 2009), interferon-gamma and pro-inflammatory cytokines (Mueller et al., 2013). There are few studies reported in the literature on δ-damascone and its biological activities. It is reported that it has toxic potential when orally administered to albino rats (Moran et al., 1980); however, when tested on humans in topical applications, there were no sensitization reactions (Lalko et al., 2007).

Accordingly, in silico analyses are used to identify absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion (ADME) properties, as one of the first processes in the discovery of new potentially therapeutic compounds (ALGHAMDI et al., 2020).

Therefore, the present study aimed to evaluate the antibacterial, inhibitory effect of the efflux pump (NorA, TetK and MepA) of Staphylococcus aureus and to evaluate in silico ADME properties of α, β and δ-damascone compounds.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bacterial strains

For the antibacterial activity assays with the standard and multidrug-resistant strains, Staphylococcus aureus (SA-10 and SA ATCC 6538), Escherichia coli (EC-06 and EC ATCC 25922) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA 24 and PA ATCC 9027) bacterial strains were used. Staphylococcus aureus strains used for efflux pump inhibition assays were: SA 1199, AS 1199B (NorA), SA IS-58 (TetK) and SA K2068 (MepA). All strains were initially maintained on blood agar to prove strain type (Laboratorios Difco Ltda., Brazil), then transferred to the stock. They were kept in two stocks: one in Heart Infusion Agar slants (HIA, Difco) at 4 °C, and the other kept in glycerol in a −80 °C freezer.

2.2 Drugs

The substances α-damascone (43052–87-5), β-damascone (23726–91-2) and δ-damascone (57378–68-4), Ethidium bromide (EtBr) were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. For tests with standard and multiresistant strains, antibiotics were used: ampicillin, sulbactam, gentamicin and ciprofloxacin. For the efflux pump inhibition tests, norfloxacin, Carbonyl Cyanide ChloroPhenyl-hydrazone (CCCP) and tetracycline were used.

2.3 Evaluation of antibacterial activity

2.3.1 Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and evaluation of modulating activity

Tests to determine MIC and to evaluate whether the substances modified the action of antibiotics against resistant and multidrug-resistant bacteria, the method proposed by (Coutinho et al., 2008) was used. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.4 Determination of effux pump inhibition (EPI)

To evaluate efflux pump inhibition, the minimum inhibitory concentration assay of all substances (α-damascone, β-damascone, and δ-damascone) was performed, as well as verified the MIC of ethidium bromide and with the antibiotics to confirm the level of resistance corroborating the presence of the pump. The concentrations ranged from 1024 µg/mL to 0.5 µg/mL.

2.4.1 Efflux pump inhibition by a modulating effect

For these experiments, the subinhibitory concentrations (MIC/8) of the test substances and the efflux pump inhibitors (EPIs) were used. In the test, 150 µL of the inoculum plus substance at subinhibitory concentration (MIC/8) were placed, and the volume of the Eppendorf tube was made up to 1.5 mL. For the control, the same inoculum volume of the test was placed and the volume of the eppendorf was made up to 1.5 mL. They were then transferred to 96-well microdilution plates with vertical distribution, characterized by the addition of 100 µL of the Eppendorf tube content to each well. After this step, microdilution of ethidium bromide or antibiotic was performed, with 100 µL in this medium until the penultimate well (1:1). In the last well, it was not added because it was the growth control. The concentrations ranged from 1024 µg/mL to 0.5 µg/mL. After 24 h, the plates were read by visualizing the color change of the medium characterized by the addition of 20 µL resazurin. The reading was determined by the color change of the culture medium from blue to red, indicating the presence of bacterial growth and the permanence in blue, the absence of growth. The reduction in MIC of ethidium bromide or specific antibiotic, in strains carrying an efflux pump, is an indication of efflux pump inhibition. All experiments were performed in triplicate ((Tintino et al., 2016).

2.4.2 Evaluation of MepA inhibition by visualization of fluorescence intensity in the UV transilluminator

For this assay, the S. aureus K-2068 strain was seeded in a BHI Agar culture medium, 24 h before the experiment, at 37 °C. After that time, the test conditions were set where ethidium bromide (EtBr) was added in subinhibitory concentration to all plates except the plate with K-2068 alone without substances. The standard efflux pump inhibitor CCCP was used as a positive control. The three test plates contained α-, β- and δ-damascone in subinhibitory concentrations. Six plates were prepared, namely: control containing only the strain on BHI Agar; negative control with strain in culture medium containing only EtBr; positive control containing the strain + the CCCP inhibitor + EtBr; plates with the test containing the strain, the α-, β-, and δ-damascone + EtBr, on each plate. The substances were added to the plate concomitantly with BHI Agar in its liquid state, and homogenization was performed in a standard way for all plates. Then, the culture medium was allowed to cool and solidify before repeating and sowing again on the newly prepared plates. After sowing K-2068, the plates were kept in an oven for 24 h at 37 °C. Finally, the reading was performed on a UV Transilluminator of plates, and images were acquired with the same magnification and camera settings to compare EtBr fluorescence emission visually (Martins et al., 2010). The fluorescence intensity was measured using Image J software (National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.4.3 Cell viability assay

Cell viability was evaluated by using an MTT assay. The damascone compounds were plated overnight in 96-well plates at 1 × 104 per well. The cells were treated with 0.1 % DMSO for 24 h, and then 20 μL MTT solution (5 mg/mL) was added into each well and incubated for 4 h. The culture supernatant was discarded, and then 100 μL DMSO was added into each well. After mixing well, OD absorbance was recorded at 490 nm by a microplate reader.

2.5 Statistical analysis

The results of the experiments were performed in triplicate and expressed as geometric mean, using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test, using GraphPad 6.0 software. In all analyses, statistical significance level was set at 5 % (p < 0.05).

2.6 Molecular modeling study at the MepA binding site

A molecular docking procedure was executed using the Molegro Virtual Docker (MVD) program. The 3D structure and identification of potential efflux binding pockets of MepA are based on the concordance of study by (de Morais Oliveira-Tintino et al., 2021) (de Morais Oliveira-Tintino et al., 2021), and all damascene (α,β and δ) structures were obtained from PubChem in sdf format.

2.7 In silico ADME prediction

To calculate the physicochemical properties of the α-, β- and δ-damascone compounds, the SwissADME tool, provided by the Swiss Bioinformatics Institute (SIB), was used (Daina et al., 2017).

3 Results

3.1 Determination of Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

The results in Table 1 show that α, β and δ-damascone present MIC of 512, 512 and 812.75 μg/mL, respectively, compared in the strain SA ATCC, while in relation to the other SA-10, EC ATCC, EC −06, PA ATCC and PA-24, exhibited a MIC ≥ 1024 μg/mL. Values represent geometric mean ± S.E.P.M. (standard error of the mean). *clinically relevant statistical value (<1024).

SA ATCC 6538

SA-10

EC ATCC25922

EC-06

PA ATCC 9027

PA-24

α-damascone

512* ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

β-damascone

812,75* ± 0,86

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

δ-damascone

512* ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

3.2 Evaluation of modulating activity

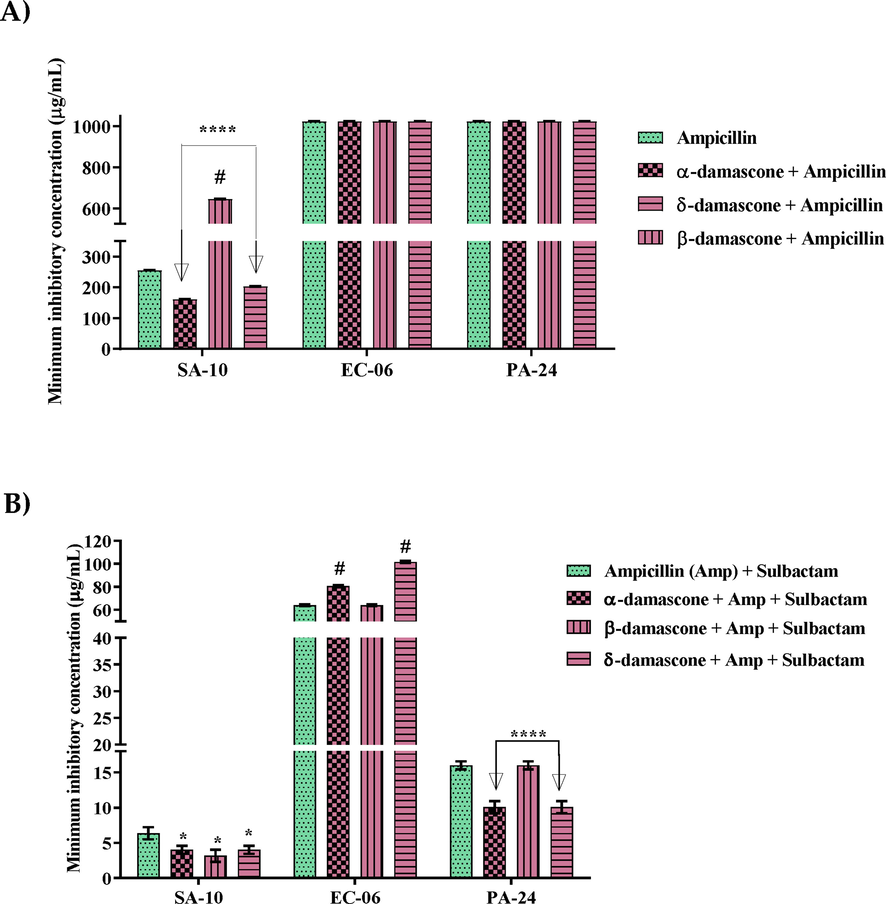

The action of ampicillin, when associated with α- and δ-DA, was modulated against SA-10 (Fig. 1A), with MICs of 161.26 and 203.18 μg/mL, respectively. Unlike the control (ampicillin), which had a MIC of 256 μg/mL. However, β-DA associated with ampicillin showed antagonism, leading to an increase in MIC from 256 to 645.08 μg/mL. Regarding the other strains, the association of ampicillin with the tested compounds did not show significant results.

Capacity of α, β and δ-damascone in inhibiting cell growth of Staphylococcus aureus (SA-10), Escherichia coli (EC-06) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA-24) strains in association with ampicillin (a), ampicillin and sulbactam (b). Values represent the geometric mean ± S.E.P.M. (standard error of the mean). Two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's test. A: Associated with Ampicillin; B: Associated with Ampicillin and Sulbactam. *p < 0.05 vs control; ****: p < 0.0001 vs control; Amp: Ampicillin; ns: not significant *: modulating effect and #: antagonism.

Fig. 1B shows that the association of β-DA with ampicillin and sulbactam modulated its effect against SA-10, with a MIC equal to 3.17 μg/mL, while the control (ampicillin + sulbactam) inhibited the cellular growth of the pathogen with 6 0.34 µg/ml. Against the EC-06 strain, antagonism was observed in relation to the association of α and δ-DA, where there was an increase in the MIC value from 64 μg/mL to 80.63 and 101.594 μg/mL, respectively. However, when ampicillin and sulbactam were associated with α- and δ-DA, it was observed modulation of their effects against PA-24, inhibiting it with MIC equal to 10.07 μg/mL for both, while the control (ampicillin + sulbactam) presented a MIC equal to 16 μg/mL.

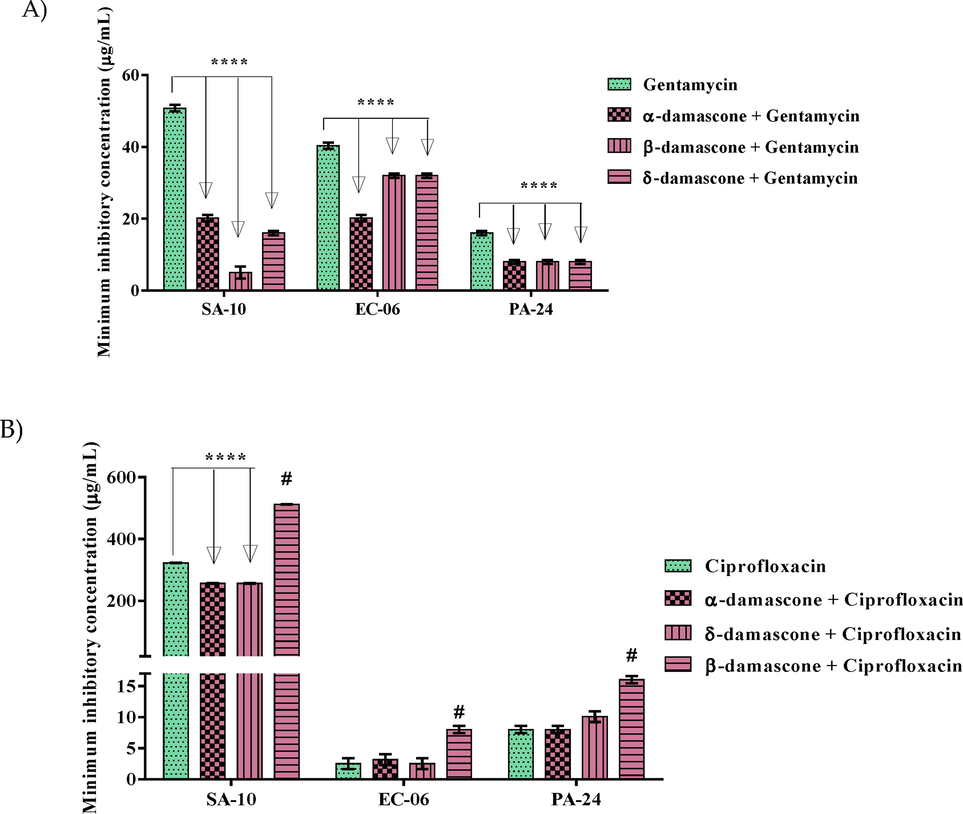

The action of gentamicin was potentiated when combined with the compounds and against all the tested strains (Fig. 2A). Regarding SA-10, the association of gentamicin with α, δ and β-DA showed an reduction of 20.15; 16 and 5.03 μg/mL, respectively, whereas the antibiotic control showed MIC equal to 50.79 μg/mL. However, when tested against strain EC-06, gentamicin in association with α, δ and β-DA, showed inhibition at 20.15 for α-damascone and 32 μg/mL, for δ and β-DA. It is worth noting that the control (gentamicin) inhibited at 40.31 μg/mL. In the evaluation against the PA-24 strain, gentamicin associated with α, δ and β-DA, showed inhibition at 8 μg/mL for the association with the three compounds.

Capacity of α, β and δ-DA in inhibiting the growth of SA-10, EC-06 and PA-24 strains in association with either gentamicin (a) or ciprofloxacin (b). Values represent the geometric mean ± S.E.P.M. (standard error of the mean). Two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's test. *p < 0.05 vs control; ****: p < 0.0001 vs control and #: antagonism.

Fig. 2B shows that the association of ciprofloxacin or ciprofloxacin hydrochloride with α and δ-DA led to a reduction in MIC of 256 μg/mL for both, while the control (ciprofloxacin) had a MIC of 322.53 μg/mL against SA-10. In relation to strains EC-06 and PA-24, α and δ-DA associated with ciprofloxacin did not show significant activity. However, β-damascone presented antagonism against all strains tested, leading to an increase in MIC from 322.54 μg/mL to 512 μg/mL, compared to SA-10, from 2.51 μg/mL to 8 μg/mL against EC-06 and from 8 μg/mL to 16 μg/mL against PA-24.

The results (Table 2) showed that only δ-damascone demonstrated clinically relevant results against SA 1199, SA 1199B and SA K-2068 strains, producing MIC values of 256, 512 and 512 μg/mL, respectively, while the other tested compounds showed MIC ≥ 1024 μg/mL. Values represent geometric mean ± S.E.P.M. (standard error of the mean). *clinically relevant statistical va lue (<1024).

SA 1199

SA 1199B

SA IS-58

SA K-2068

α-damascone

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

β-damascone

≥ 1024 ± 0,86

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

δ-damascone

256 ± 0,577*

512* ± 0,577

≥ 1024 ± 0,577

512* ± 0,577

3.2.1 Efflux pump inhibition by a modulating effect

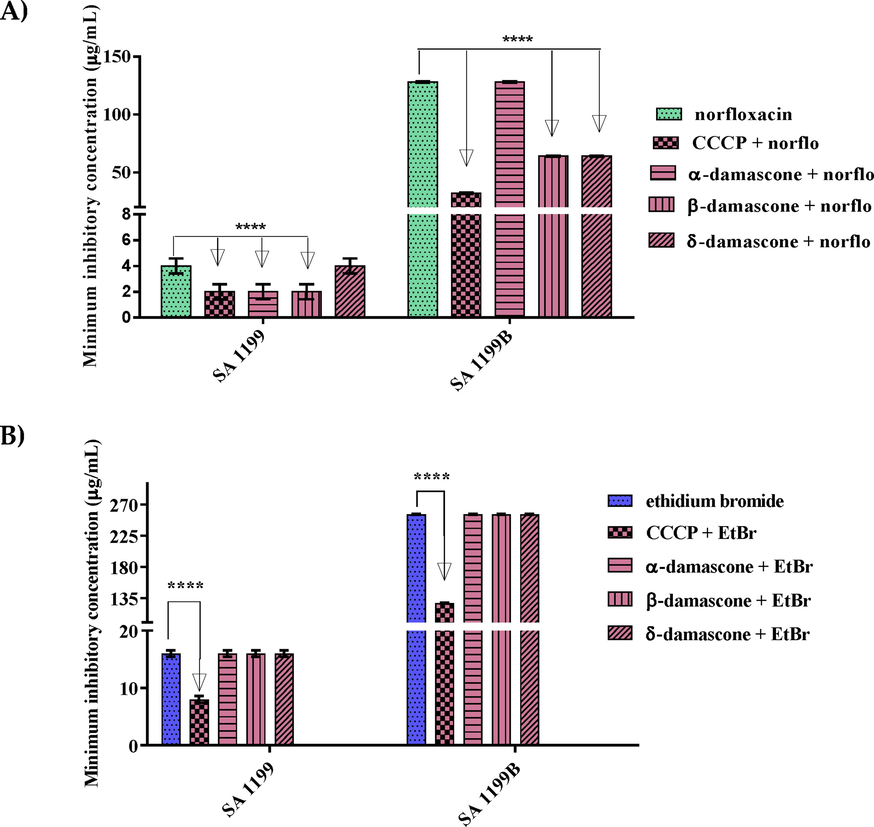

3.2.1.1 Inhibition of the NorA efflux pump

In the evaluation of efflux pump inhibition against the SA-1199 strain, regarding the combination of the tested compounds with norfloxacin, only α- and β-DA showed modulating effect, reducing the MIC from 4 μg/mL to 2 μg/mL. With regard to 1199B, all compounds, except α-DA, led to a reduction in MIC, which was from 128 μg/mL to 64 μg/mL, showing modulating effect (Fig. 3A).

Capacity of α, β and δ-DA in inhibiting the growth of strains in inhibiting the NorA efflux pump, in association with norfloxacin (a) and ethidium bromide (b), against SA strains 1199 and 1199B. Values represent the geometric mean ± S.E.P.M. (standard error of the mean). Two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's test. A:Associated with antibiotic; B:Associated with ethidium bromide. ****p < 0.0001 vs control; CCCP: carbonylcyanide-m-chlorophenylhydrazone; EtBr: ethidium bromide; norflo: norfloxacin.

However, when the compounds were combined at subinhibitory concentrations with ethidium bromide, no compound showed significant MIC reduction against strains SA-1199 and SA-1199B (Fig. 3B).

3.2.1.2 Inhibition of the TetK efflux pump

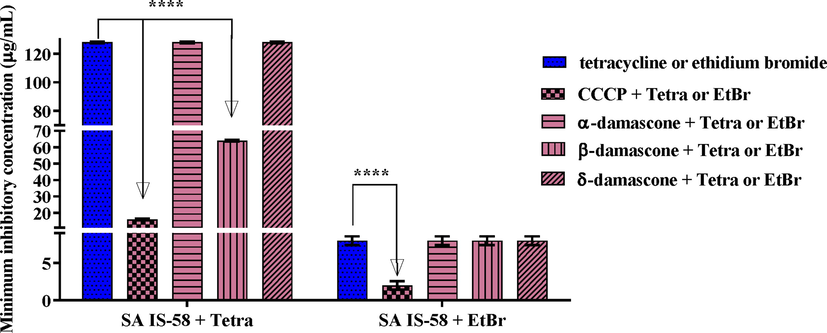

In Fig. 4, when the compounds were combined with tetracycline, only β-DA showed modulating effect with the antibiotic by reducing the MIC values from 128 μg/mL to 64 μg/mL for the first two substances. However, when combined with ethidium bromide, no compound showed modulating effect (Fig. 4B) against the multidrug-resistant strain SA IS-58.

Capacity of α, β and δ-DA in inhibiting the TetK efflux pump, in association with tetracycline or ethidium bromide, against the multidrug-resistant SA strain IS-58. Values represent the geometric mean ± S.E.P.M. (standard error of the mean). Two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's test. A: Associated with antibiotic; B: Associated with ethidium bromide. ****p < 0.0001 vs control; CCCP: carbonylcyanide-m-chlorophenylhydrazone; EtBr: ethidium bromide; Tetra: tetracycline.

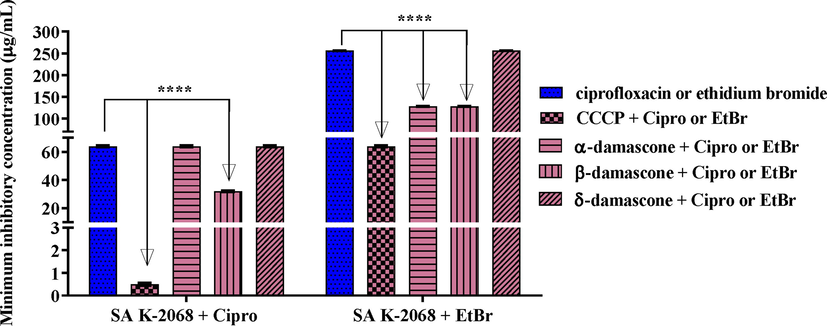

3.2.1.3 Inhibition of the MepA efflux pump

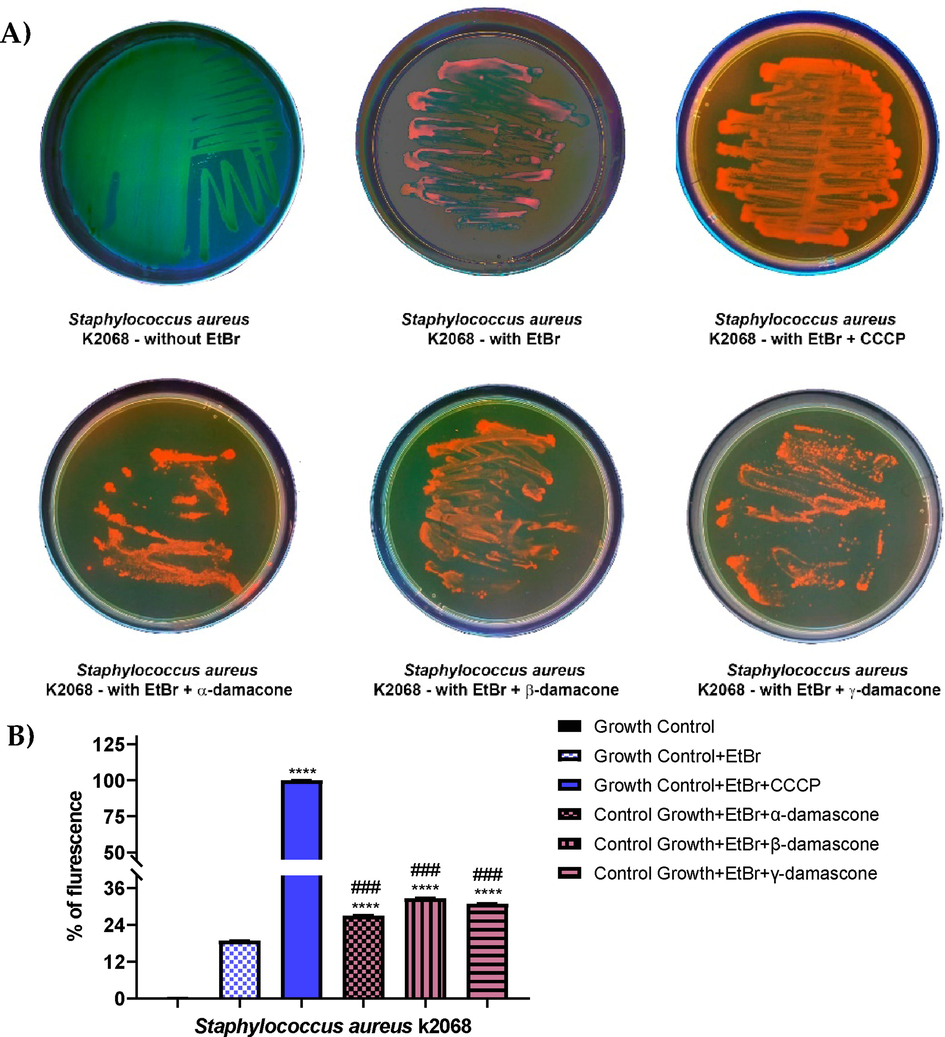

Against SA K-2068, when they were combined with ciprofloxacin and ethidium bromide, only β-DA showed a modulating effect, reducing the MIC for both combinations. The association of ciprofloxacin with β-DA induced a reduction in MIC from 64 μg/mL to 34 μg/mL. Ethidium bromide, in association with α and β-DA, had a decrease in MIC value from 256 μg/mL to 128 μg/mL (Fig. 5). Fig. 6A demonstrates the accumulation of ethidium bromide in the bacteria. This fluorescence color is proportional to an increase in the accumulation of bromide ethidium observed in bacteria. The major fluorescence intensity (intense orange/red color) was observed with CCCP a positive control and classical efflux pump inhibitor, indicating the assay's reproducibility (Fig. 6B). The addition of α-, δ-, and β-damascone demonstrated a significant difference in this intensity compared to the plate containing only EtBr, corroborating the hypothesis that damascone reduces the efficacy of the efflux pump.

Capacity of α, β and δ -DA in inhibiting the MepA efflux pump, in association with ciprofloxacin and ethidium bromide, against the multidrug-resistant strain SA K-2068. Values represent the geometric mean ± S.E.P.M. (standard error of the mean). Two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's test. A: Associated with antibiotic; B: Associated with ethidium bromide. ****p < 0.0001 vs control; CCCP: carbonylcyanide-m-chlorophenylhydrazone; Cipro: ciprofloxacin; EtBr: ethidium bromide.

Inhibiting of the MepA efflux pump by CCCP, α, β and δ -DA. A) Observed fluorescence of plate in the transillumination. B) Percentage of fluorescence. Values represent the mean ± SD. (standard error of triplicate). One-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's test. ****p < 0.0001 vs growth control and ###p < 0.001 vs growth control + EtBr; CCCP: carbonylcyanide-m-chlorophenylhydrazone; DA: Damascone; EtBr: ethidium bromide.

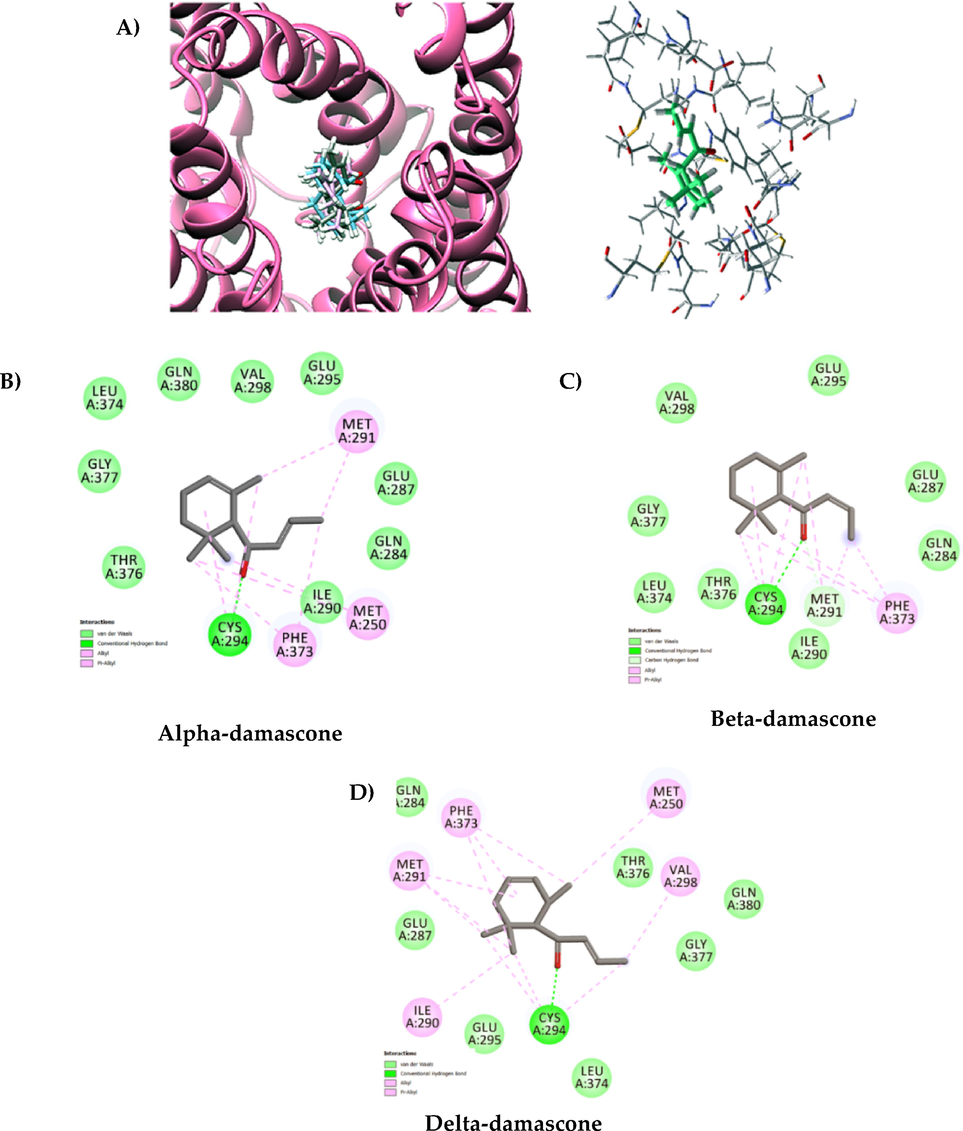

3.3 Molecular docking

The α, β and δ-damascone compounds exhibited the binding energy and Ligand Efficiency (LE) −81.17 (5.4), −77.48(-5.4) and −64.55 (-5.1), respectively, energy which shows good interactions with the critical residues of the MepA receptor. The results show that the interaction with residue in the active site is similar for: Cys294; Gln284; Glu287; Glu295; Gly377; Ile290; Leu374; Met291; Phe373 and Thr376 referring to the receptor. The maps demonstrate that the alkyl, π -alkyl, hydrogen type Van der Waals hydrophobic interaction with the Cys294 residue (Fig. 7B, 7C and 7D) for the derivatives indicate similar modes and corroborate with similarity of the physicochemical properties resulting in acceptable pharmacophore models (Fig. 7A). However, α and β -damascone demonstrate a greater number of Van der Waals bonds ensuring a better geometric fit within the active site (Fig. 7B and 7C). Based on the observations present in the inhibitor activity, Fig. 6, there is concrete evidence to support that hydrogen bonding contributes to more efficient orientation with the receptor binding pocket.

Interaction of α, β and δ-damascone at the MepA receptor. (a) Three-dimensional docked structure of α, β e δ-damascone in MepA receptor. (b) Binding site of MepA receptor complexed with α -damascone. 2D interactions map visualization between ligand and MepA receptor showing conventional hydrogen bonds as dark green dotted lines, Alkyl, and Pi-Alkyl bonds as light pink dotted lines and van der Waals forces of attraction. (c) Alpha-damascone with pocket of interactio with residues Cys294; Gln284; Gln380; Glu287; Glu295; Gly377; Ile290; Leu374; Met250; Met291; Phe373; Thr376 (d) Beta-damascone with pocket of interactio with residues Cys294; Gln284; Glu287; Glu295; Gly377; Ile290; Leu374; Met291; Phe373; Thr376; Val298 E) Delta-damascone with pocket of interactio with residues Cys294; Gln284; Gln380; Glu287; Glu295; Gly377; Ile290; Leu374; Met250; Met291; Phe373; Thr376; Val298.

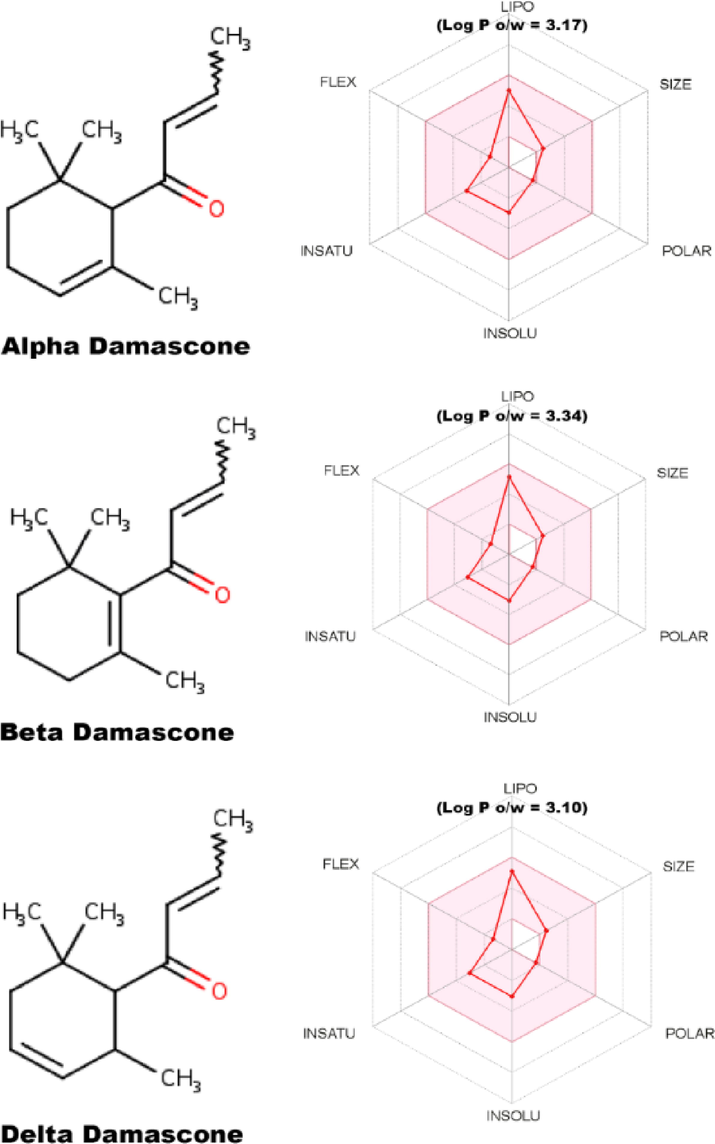

3.4 In silico ADME prediction

The compounds α, β and δ-damascone show great similarity concerning their physicochemical properties (Fig. 8). However, the fat solubility evaluated from log P o/w = 3.17, 3.34 and 3.10 shows significant differences that can be attributed to their demonstrated antibacterial and modulating properties.

ADME properties of α, β, and δ-DA. FLEX: flexibility INSATU: unsaturation INSOLU: insolubility; LogP: lipophilicity; POLAR: polarity and SIZE molecular size.

It was interesting to note that the results of the SWISS ADME predictor values for LogP, molar refractivity and the total polar surface area of these molecules were in excellent agreement with the rules, such as Lipinski, Ghose, Veber, Egan that are used to predict examples of substances with therapeutic potential (Table 3). Thus, the selected properties are well known and directly promote the influence of cellular permeation, bioavailability, and metabolism. The results showed that the high gastrointestinal (GI) absorption and blood–brain barrier permeant does not inhibit cytochromes CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 or act as a P-gp substrate, with the exception of δ-damascone which has the possibility of acting as a CYP2C9 inhibitor. Together, the evidence of good pharmacokinetic characteristics, such as lipophilicity, oral bioavailability, and low toxicity, highlight these molecules as good candidates for the development of new therapeutic agents. GI: gastrintestinal; BBB: Blood–brain barrier; MW:molecular weight; CYP1A2: Citocromo P450 1A2; CYP2C19: Citocromo P450 2C19; CYP2C9: Citocromo P450 2C9; CYP2D6: Citocromo P450 2D6; CYP2D6: Citocromo P40 2D6.

Pharmacokinetics

Compound

Alpha

Beta

Delta

GI absorption

High

High

High

BBB permeant

Yes

Yes

Yes

P-gp substrate

No

No

No

CYP1A2 inhibitor

No

No

No

CYP2C19 inhibitor

No

No

No

CYP2C9 inhibitor

No

No

Yes

CYP2D6 inhibitor

No

No

No

C inhibitor

No

No

No

Log Kp (skin permeation)

−5.17 cm/s

−5.00 cm/s

−5.05 cm/s

Drug-likeness

Alpha

Beta

Delta

Lipinski

Yes; 0 violation

Yes; 0 violation

Yes; 0 violation

Ghose

Yes

Yes

Yes

Veber

Yes

Yes

Yes

Egan

Yes

Yes

Yes

Muegge

No; 2 violations: MW < 200, Heteroatoms < 2

No; 2 violations: MW < 200, Heteroatoms < 2

No; 2 violations: MW < 200, Heteroatoms < 2

Bioavailability Score

0.55

0.55

0.55

4 Discussion

The present study reports, for the first time, the antibacterial activity of α, β and δ -DA and its potential to inhibit the efflux pump, in addition to demonstrating that their pharmacokinetic and physicochemical properties. This investigation showed the possible interaction mechanism using in silico models.

In the association of compounds to ampicillin, α- and δ-DA (Fig. 1A) reduced the MIC against SA-10 strain (p < 0.0001 vs ampicillin). And when associated with ampicillin/sulbactam (Fig. 1B), they showed MIC reduction against the PA-24 strain (p < 0.0001 vs ampicillin + sulbactam), which is a gram-negative bacterium. These bacteria are more resistant because they have an outer membrane formed by a phospholipid bilayer attached to an inner membrane by lipopolysaccharides (Antunes et al., 2017). Ampicillin works by inhibiting bacterial wall synthesis by binding to penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs), which are enzymes that act in the formation of the bacterial cell wall (Rafailidis et al., 2007). Thus, the results suggest that α- and δ-DA act to increase the potential for inhibiting the synthesis of the bacterial wall, as they potentiated the action of ampicillin.

In this context, sulbactam is an inhibitor of β-lactamase enzyme, which in association with ampicillin, acts protecting it against hydrolysis caused by this enzyme (Rafailidis et al., 2007). In the present study, a modulating effect was observed regarding the interaction between ampicillin, sulbactam and β-damascone (Fig. 1B). The results suggest that β-DA may possibly be acting against hydrolysis by β-lactamase and consequently enhancing the activity of ampicillin/sulbactam. Likewise, α and δ-DA in association with ampicillin/sulbactam may be acting to increase their capacity to penetrate the phospholipid bilayer of gram-negative bacteria, such as P. aeruginosa.

The association of gentamicin (Fig. 2A) with all tested compounds (α, β and δ -DA) caused a modulating effect against all strains (p < 0.001 vs gentamicin). Gentamicin, belongs to the class of aminoglycosides that act by binding to certain bacterial ribosomal proteins, impairing their protein synthesis (Donnenberg, 2015; Monteiro et al., 2015). This study suggests that the evaluated compounds have a modulating effect against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial strains.

In the study, as for the compounds associated with ciprofloxacin (Fig. 2B), only α- and δ-DA (p < 0.0001 vs ciprofloxacin) showed a modulating effect against SA-10. Ciprofloxacin belongs to the second-generation fluoroquinolones class, and its action is through the binding of two of the four topoisomerases of bacteria (Adefurin et al., 2011).

In this study, antagonism of the compounds α and δ-damascone was observed, when associated with ampicillin, against the SA-10 strain and of β-damascone when associated with ampicillin + sulbactam, against the EC-06 strain and when associated with ciprofloxacin, against to all strains tested.

Regarding the mechanisms that lead to antagonism, there is still little knowledge. However, the antagonism can be attributed to a combination of bactericidal and bacteriostatic agents, compounds that act on the same target as the microorganism, and chemical interactions between the compounds, which can be direct or indirect (Goñi et al., 2009). Thus, it is suggested that the compounds under study that showed antagonism against the different strains tested may be acting on the same target of the microorganism or causing this effect due to chemical interactions in association with antibiotics.

Due to the emergence of multi-drug resistant bacteria, antimicrobial treatment has become increasingly challenging. Among the main resistance mechanisms, there is the efflux pump, which prevents the accumulation of antibiotics inside the cell (Marquez, 2005; Pereira Carneiro et al., 2019).

The NorA efflux pump transporter of S. aureus confers resistance to several compounds, including fluoroquinolones and the dye ethidium bromide (EtBr), increasing bacterial pathogenicity and, therefore, sparking greater interest in new methods capable of inhibit the pump (Roy et al., 2013). In the present study, in association with norfloxacin (Fig. 3A), α- and δ-DA show effect against SA-1199 (p < 0.0001 vs norfloxacin), while against SA-1199B, significant effects were obtained by β- and δ-damascone. However, none of the compounds has been shown to interfere with the EtBr efflux mechanism (Fig. 3B). Thus, it cannot be affirmed or suggested that they have the capacity to inhibit the NorA efflux pump (Davies and Wright, 1997).

The tetK gene is located in the plasmid of S.aureus, and it is involved in the mechanisms that confer resistance to tetracycline (Schmitz et al., 2001). In the present study, when associated with tetracycline, the compound β-damascone showed modulating effect against the IS-58 strain (p < 0.0001 vs tetracycline). However, although the compounds show no direct action on the NorA or Tetk pump, due to their fat-soluble properties demonstrated in Fig. 4, it is suggested that they may interact in the cell membrane causing an alteration in the transport capacity promoting increased influx of EtBr and antibiotic into the bacterial cell; similar results have already been observed in the literature (Andrade et al., 2017), since this pump presents susceptibility to modifications in its membrane (Tintino et al., 2016).

The MepA protein belongs to the MATE family (Kaatz et al., 2006), exclusive to prokaryotes, and confers resistance to aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones (Lynch, 2006). The results showed that, in the association of α, β and δ-damascone with ciprofloxacin, only β-DA showed a modulating effect (p < 0.0001 vs ciprofloxacin). However, α and β-DA showed MIC reduction with EtBr (p < 0.0001 vs EtBr). This demonstrates the possibility of interference in the operation of the efflux pump, which can be explained by the molecular interactions shown in Fig. 7. Although this is the first work that describes the action of α, β and δ-damascone on the mechanism of bacterial resistance by an efflux pump, others in the literature have already demonstrated that essential oils, safrole and chalcones can interfere with this pump (Almeida et al., 2020; Rezende-Júnior et al., 2020).

EtBr is a dye that emits fluorescence only when intercalated into DNA; the more EtBr is intercalated and trapped in the intracellular environment, the more fluorescence emission will be observed. Otherwise, the lower the intracellular concentration of EtBr, the lower the amount intercalated in DNA and the lower its staining intensity in the UV Transilluminator (Martins et al., 2010; Olmsted and Kearns, 1977). Efflux pumps help reduce the intracellular concentration of EtBr as this is a substrate for efflux pumps. As K-2068 carries the MepA efflux pump, normal pump actuation results in bromide extrusion and little fluorescence emission (Blair et al., 2016; Gibbons et al., 2003). On the other hand, inhibition of this efflux pump will cause retention of EtBr and a consequent increase in this fluorescence in the plate, as observed in the present study. Therefore, these results are correlated with other data obtained in this work, suggesting that these compounds are possible inhibitors of the MepA efflux pump (Fig. 6).

The bioavailability radars shown (Fig. 8) represent a quick assessment of the similarities among the compounds. In it, six considerable physico-chemical properties that are determinant in pharmacokinetics are presented: lipophilicity, size, polarity, solubility, flexibility and saturation. In this context, potential therapeutic agents generally do not advance to the stages of clinical trials, due to flaws in the properties of absorption, distribution, metabolism and elimination (ADME) (Khan et al., 2018). Therefore, these maps demonstrate the capacity of a substance to be considered as a possible candidate drug, that is, one of the first steps carried out (Murugavel et al., 2020). Regarding α, β and δ-DA, they differ with respect to the position of the ring double bond, resulting in the different properties when it comes to their use in aromatic and fragrance products (Surburg and Panten, 2016), but which interfere with the lipophilicity (LogP) and consequently the interaction energy with the receptor. Several in silico studies have shown that hydrophobic regions present at the interaction site of efflux pumps of the MATE family, such as NorA and MepA, are determinants for binding stabilization (Oliveira Brito Pereira Bezerra Martins et al., 2020; Rezende-Júnior et al., 2020; Schindler et al., 2013b). Furthermore, the damascone derivatives (α, β and δ-DA) passed the ADMET screens, demonstrating low probability of drug interactions or toxic adverse effects. Furthermore, the α, β and δ-DA compounds exhibit characteristics of drug-like molecules causing no violations of the Lipinski (Pfizer) filters (Egan et al., 2000; Ghose et al., 1999; Muegge et al., 2001; Pollastri, 2010; Veber et al., 2002).

5 Conclusion

From the results obtained, it is concluded that the compounds α, β and δ-damascone, have direct action against the Gram-positive strain SA ATCC 6538. They also showed modulating activity when associated with some antibiotics.

Regarding the inhibition of the efflux pump, the compounds showed a modulating effect with norfloxacin, against SA-1199 (α and δ-damascone) and SA-1199B (β and δ-damascone), with tretracycline and ciprofloxacin (β- damascone) against SA IS-58 and K2068. Furthermore, the α and β-damascone compounds showed a modulating effect with EtBr against the SA-K2068 strain.

The in silico results showed pharmacokinetic viability necessary for good absorption and low toxicity potential, as for the docking study, related to pharmacodynamics, indicates the derivatives have promising biological activity with favorable binding energy to interact with the proton pump.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the financial support provided with contribution of Nacional Institute of Science and Technology - Ethnobiology, Bioprospecting and Nature Conservation/CNPq/FACEPE; Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel - Brazil (CAPES), Cearense Foundation to Support Scientific and Technological Development (FUNCAP), National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and Financier of Studies and Projects - Brasil (FINEP).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Adefurin, A., Sammons, H., Jacqz-Aigrain, E., Choonara, I., 2011. Ciprofloxacin safety in paediatrics: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child 96, 874–880.

- In silico ADME predictions and in vitro antibacterial evaluation of 2-hydroxy benzothiazole-based 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives. Turk. J. Chem.. 2020;44:1068-1084.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- GC-MS profile and enhancement of antibiotic activity by the essential oil of Ocotea odorífera and Safrole: inhibition of staphylococcus aureus efflux pumps. Antibiotics. 2020;9:247.

- [Google Scholar]

- Menadione (vitamin K) enhances the antibiotic activity of drugs by cell membrane permeabilization mechanism. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2017;24:59-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial electrospun ultrafine fibers from zein containing eucalyptus essential oil/cyclodextrin inclusion complex. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2017;104:874-882.

- [Google Scholar]

- Blair, J., MBio, L.P.-, 2016, undefined, 2016. How to measure export via bacterial multidrug resistance efflux pumps. Am Soc Microbiol 7. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00840-16.

- Enhancement of the antibiotic activity against a multiresistant Escherichia coli by Mentha arvensis L. and chlorpromazine. Chemotherapy. 2008;54:328-330.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Atividade antimicrobiana de óleos essenciais e compostos isolados frente aos agentes patogênicos de origem clínica e alimentar. Rev. Inst. Adolfo Lutz. 2017;76:e1719.

- [Google Scholar]

- SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep.. 2017;7:1-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial resistance to aminoglycoside antibiotics. Trends Microbiol.. 1997;5:234-240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical synthesis, molecular docking and MepA efflux pump inhibitory effect by 1, 8-naphthyridines sulfonamides. Eur. J. Pharma. Sci.. 2021;160:105753

- [Google Scholar]

- Demole, E., Enggist, P., Säuberli, U., Stoll, M., Sz. Kováts, E., 1970. Structure et synthèse de la damascénone (triméthyl‐2, 6, 6‐trans‐crotonoyl‐1‐cyclohexadiène‐1, 3), constituant odorant de l’essence de rose bulgare (rosa damascena Mill. Helv Chim Acta 53, 541–551.

- Donnenberg, M.S., 2015. Enterobacteriaceae, in: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier, pp. 2503–2517.

- Staphylococcus aureus: visitando uma cepa de importância hospitalar. J. Bras. Patol. Med. Lab.. 2007;43:413-423.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of drug absorption using multivariate statistics. J. Med. Chem.. 2000;43:3867-3877.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical and economic impact of antibiotic resistance in developing countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2017;12:1-18.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of 3-hydroxy-β-damascone and related carotenoid-derived aroma compounds as novel potent inducers of Nrf2-mediated phase 2 response with concomitant anti-inflammatory activity. Mol. Nutr. Food Res.. 2009;53:1237-1244.

- [Google Scholar]

- A knowledge-based approach in designing combinatorial or medicinal chemistry libraries for drug discovery. 1. a qualitative and quantitative characterization of known drug databases. J. Comb. Chem.. 1999;1:55-68.

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel inhibitor of multidrug efflux pumps in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2003;51:13-17.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Transformation of β-damascone to (+)-(S)-4-hydroxy-β-damascone by fungal strains and its evaluation as a potential insecticide against aphids Myzus persicae and lesser mealworm Alphitobius diaperinus Panzer. Catal. Commun.. 2016;80:39-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity in the vapour phase of a combination of cinnamon and clove essential oils. Food Chem.. 2009;116:982-989.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanzadeh, S., ganjloo, S., Pourmand, M.R., Mashhadi, R., Ghazvini, K., 2020. Epidemiology of efflux pumps genes mediating resistance among Staphylococcus aureus; A systematic review. Microb Pathog 139, 103850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103850.

- Frequency of efflux pump genes mediating ciprofloxacin and antiseptic resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Microb. Pathog.. 2017;111:71-74.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MepR, a repressor of the Staphylococcus aureus MATE family multidrug efflux pump MepA, is a substrate-responsive regulatory protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother.. 2006;50:1276-1281.

- [Google Scholar]

- Action and resistance mechanisms of antibiotics: a guide for clinicians. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol.. 2017;33:300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile one-pot synthesis, antibacterial activity and in silico ADME prediction of 1-substituted-1H-1,2,3,4-tetrazoles. Chem. Data Collect.. 2018;15–16:107-114.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A review on efflux pump inhibitors of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria from plant sources. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci.. 2016;5:834-855.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fragrance material review on delta-damascone. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2007;45:S205-S210.

- [Google Scholar]

- The hierarchy quorum sensing network in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Protein Cell. 2015;6:26-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selective oxidation of carotenoid-derived aroma compounds by CYP260B1 and CYP267B1 from Sorangium cellulosum So ce56. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2016;100:4447-4457.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efflux systems in bacterial pathogens: an opportunity for therapeutic intervention? an industry view. Biochem. Pharmacol.. 2006;71:949-956.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial efflux systems and efflux pumps inhibitors. Biochimie. 2005;87:1137-1147.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of efflux-mediated multi-drug resistance in bacterial clinical isolates by two simple methods. Methods Mol. Biol.. 2010;642:143-157.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira Brito Pereira Bezerra Martins, A., Wanderley, A.G., Alcântara, I.S., Rodrigues, L.B., Cesário, F.R.A.S., Correia de Oliveira, M.R., Castro, F.F. e, Albuquerque, T.R. de, da Silva, M.S.A., Ribeiro-Filho, J., Coutinho, H.D.M., Menezes, P.P., Quintans-Júnior, L.J., Araújo, A.A. de S., Iriti, M., Almeida, J.R.G. da S., Menezes, I.R.A. de, 2020. Anti-Inflammatory and Physicochemical Characterization of the Croton rhamnifolioides Essential Oil Inclusion Complex in β-Cyclodextrin. Biology (Basel) 9, 114. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology9060114.

- Antibacterial activity of chitosan nanofiber meshes with liposomes immobilized releasing gentamicin. Acta Biomater.. 2015;18:196-205.

- [Google Scholar]

- Acute oral toxicity of selected flavour chemicals. Drug Chem. Toxicol.. 1980;3:249-258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Simple selection criteria for drug-like chemical matter. J. Med. Chem.. 2001;44:1841-1846.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of triterpenoids present in apple peel on inflammatory gene expression associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Food Chem.. 2013;139:339-346.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, structural, spectral and antibacterial activity of 3,3a,4,5-tetrahydro-2H-benzo[g]indazole fused carbothioamide derivatives as antibacterial agents. J. Mol. Struct.. 2020;1222:128961

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanism of ethidium bromide fluorescence enhancement on binding to nucleic acids. Biochemistry. 1977;16:3647-3654.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitors of efflux pumps in gram-negative bacteria. Trends Mol. Med.. 2005;11:382-389.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira Carneiro, J.N., da Cruz, R.P., da Silva, J.C.P., Rocha, J.E., de Freitas, T.S., Sales, D.L., Bezerra, C.F., de Oliveira Almeida, W., da Costa, J.G.M., da Silva, L.E., Amaral, W. do, Rebelo, R.A., Begnini, I.M., Melo Coutinho, H.D., Bezerra Morais-Braga, M.F., 2019. Piper diospyrifolium Kunth.: Chemical analysis and antimicrobial (intrinsic and combined) activities. Microb Pathog 136, 103700. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103700.

- Multidrug-resistance efflux pumps? not just for resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.. 2006;4:629-636.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extraintestinal pathogenic escherichia coli and antimicrobial drug resistance in a maharashtrian drinking water system. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg.. 2019;100:1101-1104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rezende-Júnior, L.M., Andrade, L.M. de S., Leal, A.L.A.B., Mesquita, A.B. de S., Santos, A.L.P. de A. dos, Neto, J. de S.L., Siqueira-Júnior, J.P., Nogueira, C.E.S., Kaatz, G.W., Coutinho, H.D.M., 2020. Chalcones Isolated from Arrabidaea brachypoda Flowers as Inhibitors of NorA and MepA Multidrug Efflux Pumps of Staphylococcus aureus. Antibiotics 9, 351.

- Rouquette-loughlin, C., Dunham, S.A., Kuhn, M., Balthazar, J.T., Shafer, W.M., 2003. The NorM Efflux Pump of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Neisseria meningitidis Recognizes Antimicrobial Cationic Compounds 185, 1101–1106. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.185.3.1101

- NorA efflux pump inhibitory activity of coumarins from Mesua ferrea. Fitoterapia. 2013;90:140-150.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of drug efflux pumps in Staphylococcus aureus: current status of potentiating existing antibiotics. Future Microbiol.. 2013;8:491-507.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mutagenesis and modeling to predict structural and functional characteristics of the Staphylococcus aureus MepA multidrug efflux pump. J. Bacteriol.. 2013;195:523-533.

- [Google Scholar]

- Resistance to tetracycline and distribution of tetracycline resistance genes in European Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2001;47:239-240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in the synthesis of carotenoid-derived flavours and fragrances. Molecules. 2015;20:12817-12840.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Secondary metabolites in plants: transport and self-tolerance mechanisms. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.. 2016;80:1283-1293.

- [Google Scholar]

- Common fragrance and flavor materials: preparation, properties and uses. John Wiley & Sons; 2016.

- Tintino, S.R., Oliveira-Tintino, C.D.M., Campina, F.F., Silva, R.L.P., Costa, M. do S., Menezes, I.R.A., Calixto-Júnior, J.T., Siqueira-Junior, J.P., Coutinho, H.D.M., Leal-Balbino, T.C., 2016. Evaluation of the tannic acid inhibitory effect against the NorA efflux pump of Staphylococcus aureus. Microb Pathog 97, 9–13.

- Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management. Clin. Microbiol. Rev.. 2015;28:603-661.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem.. 2002;45:2615-2623.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Annual Plant Reviews. Functions and Biotechnology of Plant Secondary Metabolites: John Wiley & Sons; 2010.

- Yingst, S.L., Saad, M.D., Felt, S.A., 2006. cdc_16191_DS1(0) 12, 1297–1299.