Translate this page into:

Phytochemical analysis and in vitro and in vivo antioxidant properties of Plagiorhegma dubia Maxim as a medicinal crop for diabetes treatment

⁎Corresponding authors. 15044586210@163.com (Li Li), qingguangx@163.com (Guangqing Xia), zanghao_1984@163.com (Hao Zang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

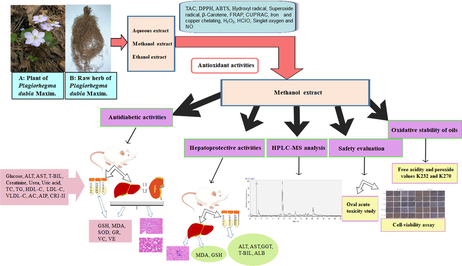

In traditional medicine, Plagiorhegma dubia Maxim (PD) is used to treat diabetes, irritability, insomnia, high fever, and coma. In this study, to identify the components in PD, we first performed three preliminary phytochemical tests, which were all positive for the presence of alkaloids. Next, we evaluated the total alkaloid content and performed 13 different in vitro antioxidant experiments for three solvent extracts of PD. According to the results, the methanol extract was selected for further research. Ultra-performance liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization Orbitrap mass spectrometry was used to identify 41 compounds in the methanol extract. Thirty-eight of these compounds were alkaloids, and the main components were magnoflorine, berberrubine, and betaine. Addition of the methanol extract to cooking oil increased the stability against oxidation and greatly reduced the peroxide value. Cell viability and oral acute toxicity studies in mice indicated that the methanol extract was relatively non-toxic. Histopathological examination and biochemical analysis showed that the methanol extract was protective against liver damage in rats induced by d-galactosamine. The methanol extract also showed a good antidiabetic effect for streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats, where it lowered blood sugar levels and protected vital organs against damage. Lipid profile parameters and oxidative stress parameters also improved. The therapeutic effects towards diabetes and liver damage were attributed to the ability of the three main components in the methanol extract to resist oxidative stress. Our results show that the alkaloid-rich methanol extract of PD is potential candidate for treatment of diseases associated with oxidative imbalances. This understanding of the hepatoprotective effect and antidiabetic activity of PD provides new insight for its use as a substitute for Coptis chinensis and establishes a foundation for development of PD as an economic crop.

Keywords

Plagiorhegma dubia Maxim

Phytochemical analysis

Oxidative stress

Antioxidant activity in vitro

Liver damage

Diabetes mellitus

1 Introduction

Plagiorhegma dubia Maxim (PD) belongs to the genus Plagiorhegma (Berberidaceae) and is a perennial medicinal plant originating in Eastern Asia. It is commonly known as Asian twinleaf. PD is a prevalent ornamental plant because of its fascinating flowers and leaves. The plant is 10–30 cm tall and blooms from May to June. Its branched rhizome has many fibrous roots. PD grows in coniferous forests or in damp places on hillsides (Flora of China Editorial Committee of Chinese Academy of Sciences., 2001). The young stems and leaves are edible and can be used as feed for livestock (Wang et al., 2014). The underground parts of PD are used as medicine, and mainly as a substitute for Coptis chinensis (CC) (Yu et al., 2016). In traditional medicine, PD has functions of heat-clearing and detoxification, drying, purging fire, invigorating the stomach, and relieving diarrhea. It is used to treat diabetes, irritability, insomnia, high fever, coma, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, and other diseases (Jilin Medical Products Administration., 2019); however, convincing scientific evidence is lacking. There is some controversy around the composition of PD. Some believe that the main component is berberine (Jeong and Sivanesan., 2016; Xu et al., 1992; Duke and Ayensu.,1985), while others believe that it mainly contains jatrorrhizine (Arens et al., 1985; Ishikawa et al., 1978; Yu et al., 2003) and magnoflorine (Ishikawa et al., 1978). Apart from a report on the isolation of two lignins from a methanol extract of cultured PD cells (Arens et al., 1985), there have been no reports on its chemical composition. Moreover, there have been no reports on the toxicology of PD in humans.

A substitute for CC is urgently required. Changes in the environment and exploitation of CC have resulted in ecological damage to wild sources of CC. Reserves have decreased sharply and wild CC is on the verge of extinction. Consequently, most CC sold commercially is cultivated. However, the cultivation requirements for CC are also complex in terms of the altitude, temperature, light, and soil, and this has reduced production yields and increased prices (Sheng et al., 2006).

Furthermore, if CC is taken for a long time or in a large amount over a short time, it causes damage to the spleen and stomach. Common side effects in such cases are abdominal pain, nausea, retching, and diarrhea. Additionally, many studies have reported that berberine, a major component of CC, is toxic (Yi et al., 2013). Therefore, a new plant medicine with similar efficacy to CC and reduced side effects is required.

To protect and develop medicinal plant resources, active investigation of new medicinal sources is an important task. A key method for this is combination of pharmacological screening with ethnic or folk medicine knowledge. The research on Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora is a good example of this, and this species is a good substitute for CC. However, Neopicrorhiza scrophulariiflora is endangered in the wild (Rokaya et al., 2020). Therefore, another substitute for CC needs to be identified and evaluated in pharmacological and clinical research.

In the human body, cell metabolism and oxidative stress inevitably generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). Crucial macromolecules, such as lipids, carbohydrates, proteins, and DNA/RNA, are impaired by high levels of ROS. ROS have a vital role in the pathogenic mechanism of countless serious diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, Alzheimer’s disease, and liver disease because free radical production is associated with the occurrence and progression of these diseases. Some studies have found that alkaloids in various medicinal plants can reduce the risk of various diseases because of their antioxidant capacities (Li et al., 2020; Shaghaghi et al., 2019; Koolen et al., 2017). Supplementation with antioxidants can be used to maintain the body’s antioxidant balance. Plants are often studied for identification of safe and effective antioxidants (Zhang et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2021). Various methods are used to assess the antioxidant abilities of plant extracts and isolated compounds. The main methods involve 1) evaluation of the free radical scavenging ability using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH·), 2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS), superoxide radicals, hydroxyl radicals, and β-carotene; 2) evaluation of the scavenging ability for oxidizing substances such as hypochlorous acid (HClO), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), nitric oxide (NO), and singlet oxygen; 3) evaluation of the ability to chelate metals such as iron and copper; and 4) evaluation of the redox capacity using the cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity (CUPRAC) and ferric-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assays. Different methods are used for antioxidant assessments because of distinct antioxidant mechanisms.

Both the levels of antioxidants and lipid peroxidation in animals are affected by disease. Antioxidant levels and lipid peroxidation in animal tissue and serum can be evaluated using decreases in the levels of glutathione, superoxide dismutase, glutathione reductase, vitamin C, vitamin E, and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and increases in the levels of malondialdehyde, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, total bilirubin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) cholesterol (Abdelghffar et al., 2022; Sobeh et al., 2017; Al-Numair et al., 2015). These indicators could be used to explore the therapeutic effect of PD on oxidative stress-related diseases.

The objective of our research was to identify the principal chemical components of PD, and to analyze and identify its other components. We then evaluated the antioxidant capacity of PD in vitro and in vivo. The results provide a scientific basis for PD to replace CC and provide ideas for future in-depth research and development.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals, reagents and biochemical estimation kits

Aspartate aminotransferase assay kit, alanine aminotransferase assay kit, γ-glutamyl transferase assay kit, total bilirubin kit, creatinine assay kit (sarcosine oxidase), uric acid test kit, total cholesterol assay kit, triglyceride assay kit, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol assay kit, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol assay kit, malondialdehyde assay kit (TBA method), reduced glutathione assay kit, glutathion reductases assay kit, vitamin C assay kit (colorimetric method), vitamin E assay kit (colorimetric method), glucose kit (glucose oxidase method), albumin assay kit, urea assay kit, reduced glutathione assay kit and nitric oxide assay kit were acquired from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). Lipid peroxidation MDA assay kit, total Superoxide dismutase assay kit (NBT method) and enhanced BCA protein assay kit were acquired from Beyotime Biotechnology Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). TM3 mouse Leydig cells were purchased from Procell (Wuhan, Hubei, China). d-Galactosamine, streptozotocin, silymarin, and glibenclamide were acquired from Energy Chemicals (Shanghai, China). All solvents were of analytical grade and acquired from Sinopharm (Shanghai, China).

2.2 Plant materials

A sample of the underground parts of PD was acquired (voucher specimen number: 2021–09-08–002) in Tonghua, China (latitude N126°00′40.40′′, longitude E41°44′10.99′′, altitude 503.3 m) in September 2021. The identity of the specimen was confirmed by Prof. Junlin Yu and deposited at the Herbarium of Tonghua Normal University (Tonghua, China).

2.3 Extract preparation

The underground parts of PD were cleaned and washed. They were then partially dried by placing them in a cool ventilated place, and then completely dried in an oven at 45 °C for 30 h. Powdered herb (200 g) was added to a flask with 2 L of solvent (water, methanol, or ethanol) and refluxed for 6 h at the corresponding boiling point. Each extract was filtered using a Buchner funnel and concentrated under reduced pressure at a temperature below 50 °C. All extracts were stored at −20 °C before use.

2.4 Preliminary phytochemical tests for alkaloids

Bertrad’s reagent, Dragendorff’s reagent, and Mayer’s reagent were used to check for the presence of alkaloids in accordance with established methods (Chen et al., 2022).

2.5 Measurement of the total alkaloid content

The total alkaloid content was measured using an established method (Lee et al., 2021). Berberine hydrochloride (1.24–12.36 mg/L) was used as a reference material to construct a standard curve. The absorbance was obtained at 420 nm against a blank sample of chloroform. The mean of three measurements was calculated. The total alkaloid content is expressed in milligrams of berberine hydrochloride equivalents per gram of PD extract.

2.6 Ultra-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

The methanol extract of PD was analyzed using ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC; UltiMate 3000 system, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) with electrospray ionization and Orbitrap mass spectrometry (MS). A Poroshell 120EC-C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 2.7 µm; Agilent, Palo Alto, California, USA) was used for separation. The column temperature was set to 35 °C. The mobile phase was a mixture of 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 100% acetonitrile (solvent B) at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. A linear gradient elution was applied (0–45 min, 95%–0% A; 45–60 min, 0%–95% A). The extract was diluted to 1 mg/mL with methanol and passed through a 0.22-µm filter. The sample injection volume was 5 µL.

The Orbitrap-MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was operated in positive ion mode with a scan range of m/z 50–1000. The capillary voltage was + 3.5 kV. The capillary temperature and auxiliary gas heater temperature were 320 °C and 350 °C, respectively. Data were recorded and analyzed with Xcalibur software (Version 2.2.42, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.7 In vitro antioxidant activity

DPPH·, ABTS, hydroxyl radical, superoxide radical, β-carotene, FRAP, CUPRAC, iron chelation, copper chelation, H2O2, hypochlorous acid, singlet oxygen, and nitric oxide assays were conducted using established methods (Chen et al., 2022; Guo et al., 2022).

2.8 Oxidative stability of oils

The oxidative stabilities of extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) and cold-pressed sunflower oil (CPSO) with added PD were measured using established methods (Chen et al., 2022).

2.9 Cell viability assay

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was used to evaluate the cell-viability against a TM3 cell line (Chen et al., 2022).

2.10 Oral acute toxicity study

An oral acute toxicity study was conducted according to a standard from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD-425). Twenty adult Kunming mice (19–22 g) were divided into two groups (n = 10) with five males and five females in each group. The mice in the healthy control group received vehicle treatment. The methanol extract was dissolved in water to a final volume of 10 mL/kg mouse body weight (BW) and then administered to the mice in the PD group orally in a single dose of 2000 mg/kg PD methanol extract. The mice were then continuously observed for 1 h for behavioral changes and toxicity. Intermittent observations were made for next 6 h, and a final observation was conducted at 24 h. At this stage, the survival rate was calculated and we found that no mice died. All mice were euthanized using isoflurane. On the basis of the study results, two doses (150 and 300 mg/kg) were selected for further study.

2.11 Hepatoprotective experiments

2.11.1 Animals

Adult male Wistar rats (170–200 g) were acquired by Liaoning Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (animal license number SCXK (Liao) 2020–0001; Liaoning, China). Housed rats had free access to food and water under a 12 h light–dark cycle. All rats were reared adaptively for 1 week before starting the experiment. We followed the relevant policies in the Guidelines for the Use of Laboratory Animals developed by Tonghua Normal University. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved the protocol (approval number: 20220043).

2.11.2 Experimental protocol

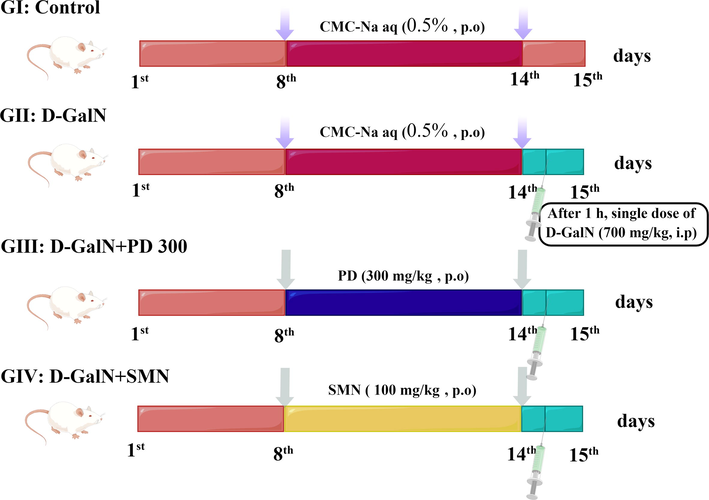

Hepatic injury was induced as described in a previous study (Mondal et al., 2020). Thirty-two rats were randomly divided into four groups (n = 8) (Fig. 1, drawn by figdraw). Each group received a different treatment orally. Group I (control group) rats were treated with 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose sodium. Group II (negative control group) rats were treated with d-galactosamine and 0.5% carboxymethylcellulose sodium. Group III (treatment group) rats were treated with PD (300 mg/kg BW). Group IV (comparison group) rats were treated with silymarin (100 mg/kg BW).

Experimental design of the in vivo liver protection assay for groups I–IV (GI–GIV). G: Group; PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; SMN: Silymarin; D-GalN: D-Galactosamine; CMC-Na: Carboxymethylcellulose sodium; aq: Aqueous solution; p.o: Peros. i.p: Intraperitoneal injection.

All the treatments were performed daily for 7 days. After the last day of treatment, rats in groups II–IV received d-galactosamine (700 mg/kg BW) by intraperitoneal injection. The rats were then fasted for 24 h with access to water. After all the above processes were completed, we found that no rats died after d-galactosamine injection. Next, all rats were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg BW). Abdominal aortic blood was collected, and the hepatic tissue was rapidly excised. After leaving the blood samples at room temperature for 0.5 h, they were centrifuged for 0.25 h at 3000 rpm and 4 °C. The serum was stored at −80 °C. The tissue was washed with normal saline, dried using filter paper, and weighed. A 10% homogenate of the hepatic tissue was prepared using normal saline, centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C, and the supernatant was stored at −80 °C.

2.11.3 Histopathological examination

The hepatic tissues of three rats were selected from each group, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, dehydrated and washed, and embedded in paraffin. After cutting into 4-µm thick sections, hematoxylin and eosin were used for staining. Observations were made using a light microscope. A digital camera was used to record histopathological changes.

2.11.4 Biochemical analyses

Before anesthesia, each rat was weighed. The hepatic tissue weight and BW of each rat were used to calculate the visceral adiposity index (VI) as follows: VI = viscera weight (g)/BW (g) × 100%.

For assessment of biochemical parameters related to liver function, serum samples were analyzed for alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, albumin, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, and total bilirubin. Hepatic samples were analyzed for glutathione and malondialdehyde. All samples were analyzed using commercial kits according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

2.12 Antidiabetic activity

2.12.1 Animals

This details for the animals are given in Section 2.11.1.

2.12.2 Diabetes induction

Diabetes was induced using a previously described method (Xia et al., 2021). Briefly, rats were starved overnight and then injected intraperitoneally with streptozotocin (50 mg/kg BW), which induced diabetes within 72 h by destroying β-cells. A blood sugar level of > 13.8 mmol/L was considered diagnostic of diabetes. If the blood sugar level was < 13.8 mmol/L, more streptozotocin (25 mg/kg) was administered and the blood glucose level was tested again after 48 h. The rats at this stage with blood glucose levels > 13.8 mmol/L were selected for the experiment. At 4 h after injection of streptozotocin, 10% glucose solution was administered orally to avoid streptozotocin-induced hypoglycemia.

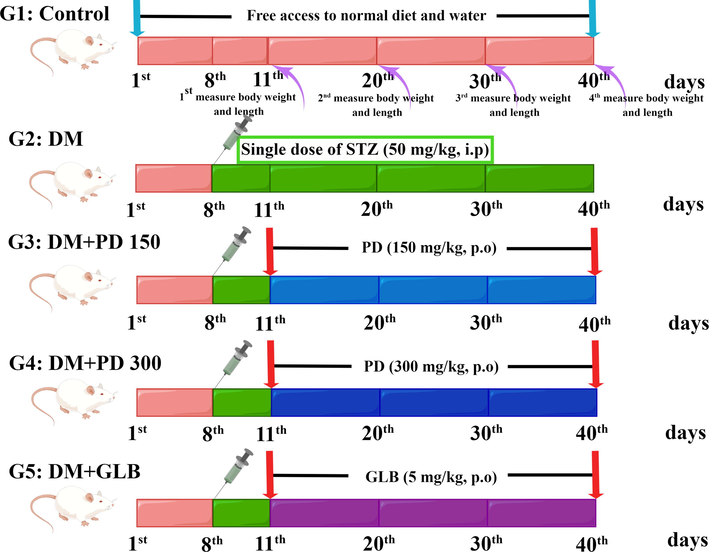

2.12.3 Experimental protocol

Forty rats were randomly divided into five groups (n = 8) (Fig. 2, drawn by figdraw). Each group received a different treatment orally each day for 30 days. The rats in group 1 (control group) were treated with distilled water. The rats in group 2 (diabetes mellitus group) had diabetes induced with streptozotocin (Section 2.12.2) and received distilled water. The rats in group 3 (diabetes + PD150 group) had diabetes induced with streptozotocin (Section 2.12.2) and received 150 mg/kg BW PD daily. The rats in group 4 (diabetes + PD300 group) had diabetes induced with streptozotocin (Section 2.12.2) and received 300 mg/kg BW PD daily. The rats in group 5 (comparison group) had diabetes induced with streptozotocin (Section 2.12.2) and received 5 mg/kg BW glibenclamide daily.

Experimental design of the in vivo antidiabetic assay for groups 1–5 (G1–G5). G: Group; PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; DM: Diabetes mellitus; STZ: Streptozotocin; GLB: Glibenclamide; p.o: Peros. i.p: Intraperitoneal injection.

During treatment, the rats were checked every day for clinical features. After all the above processes were completed, we found that no rats died after streptozotocin injection. At the end of treatment, after fasting for 12 h with access to water, all rats were anaesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg BW). Abdominal aortic blood was collected, and the hepatic and renal tissues were rapidly excised. The blood and tissue samples were treated as described in Section 2.11.2.

2.12.4 Histopathological examination

Histopathological examination was conducted as described in Section 2.11.3.

2.12.5 Biochemical analyses

The VI was calculated as described in Section 2.11.4. The serum glucose level was quantified using a commercial kit. To assess biochemical parameters related to liver function, serum samples were analyzed for alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and total bilirubin using commercial kits. Similarly, to assess biochemical parameters related to kidney function, the levels of creatinine, urea and uric acid in serum were assessed using commercial kits. Serum HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol were measured using commercial kits. VLDL cholesterol, Castelli’s risk indexes I and II, the atherogenic coefficient, and the atherogenic index of plasma were calculated according to established methods (Abdelghffar et al., 2022). For assessment of oxidative stress parameters, the levels of glutathione reductase, malondialdehyde, glutathione, superoxide dismutase, vitamin C, and vitamin E in serum, hepatic and renal tissues were measured using commercial kits.

2.13 Statistical analysis

The data are shown as means with the standard error of the mean. Significant correlations between groups were tested using one-way analysis of variance with post-hoc least significant difference tests. Pearson’s correlation was used to investigate the relationship between antioxidant activity and total alkaloid content. Statistical significance was defined using p-values of 0.05, 0.01, and 0.001 for significant, highly significant, and very highly significant, respectively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Chemical composition

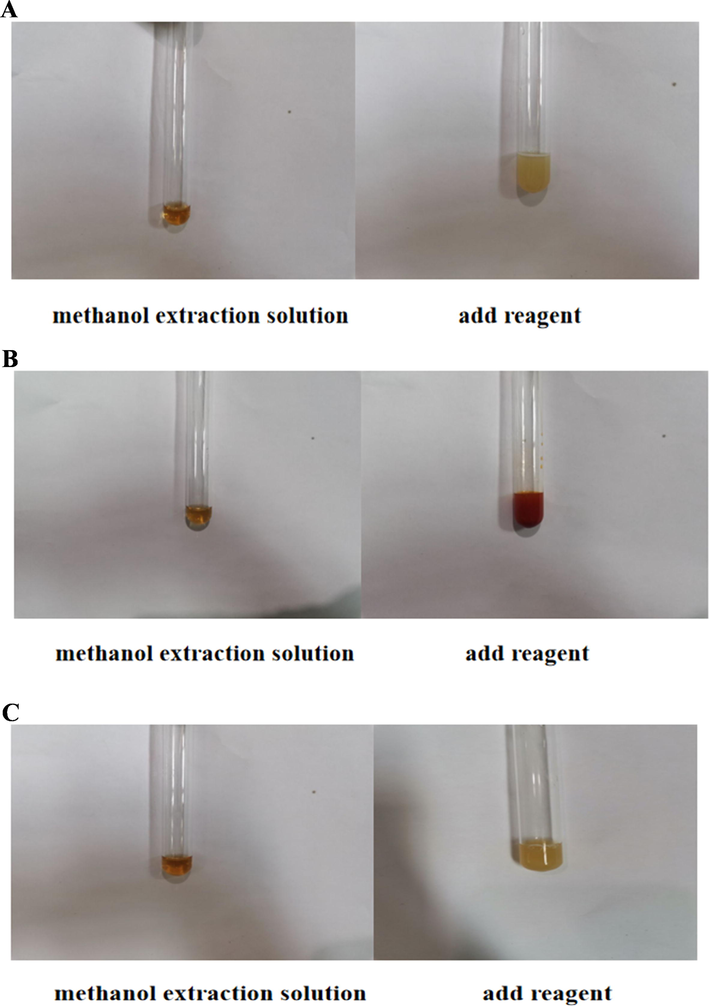

The results from three preliminary phytochemical tests for alkaloids confirmed that PD contained alkaloids (Table 1, Fig. 3). The effects of the three different extraction solvents on the yield of PD were investigated. Methanol gave the highest extraction yield (Table 2). The total alkaloid contents of the three PD extracts were determined by spectrophotometry (Table 2). For the alkaloid content, the methanol extract had the highest total alkaloid content (Table 2). These results show that methanol can extract more alkaloids from PD than the other two solvents. On the basis of these results, the methanol extract was selected for subsequent experiments. (+) indicates presence. a–c Columns with different superscripts indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05). Yield was calculated as % yield = (weight of extract/initial weight of dry sample) × 100. TAC: Total alkaloid content. BHE: Berberine hydrochloride equivalent. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Phytochemical

Type of test

Methanol extraction solutions

Alkaloids

1. Bertrad's reagent

+

2. Dragendorff's reagent

+

3. Mayer's reagent

+

Photographs of the steps in the tests for alkaloids.

Extracting solvents

Yields (%, w/w)

TAC (mg BHE/g extract)

Water

11.7 ± 0.7b

10.9 ± 0.1c

Methanol

13.9 ± 0.3a

25.2 ± 0.1a

Ethanol

9.8 ± 0.5c

24.3 ± 0.1b

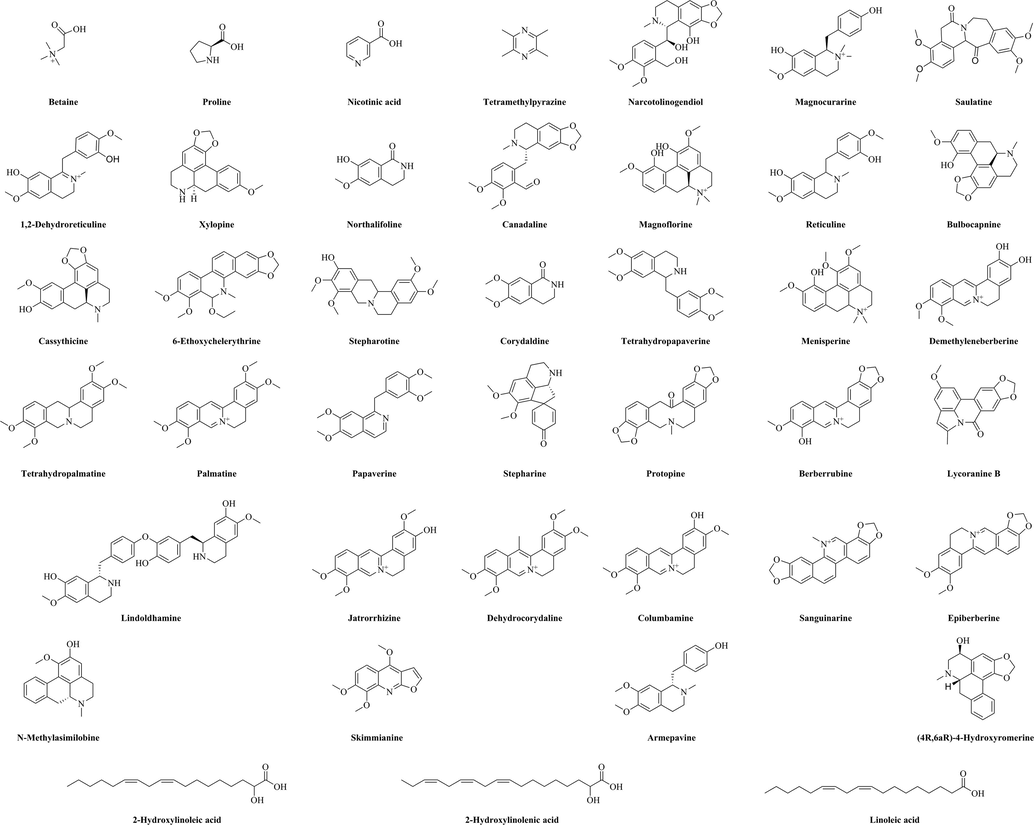

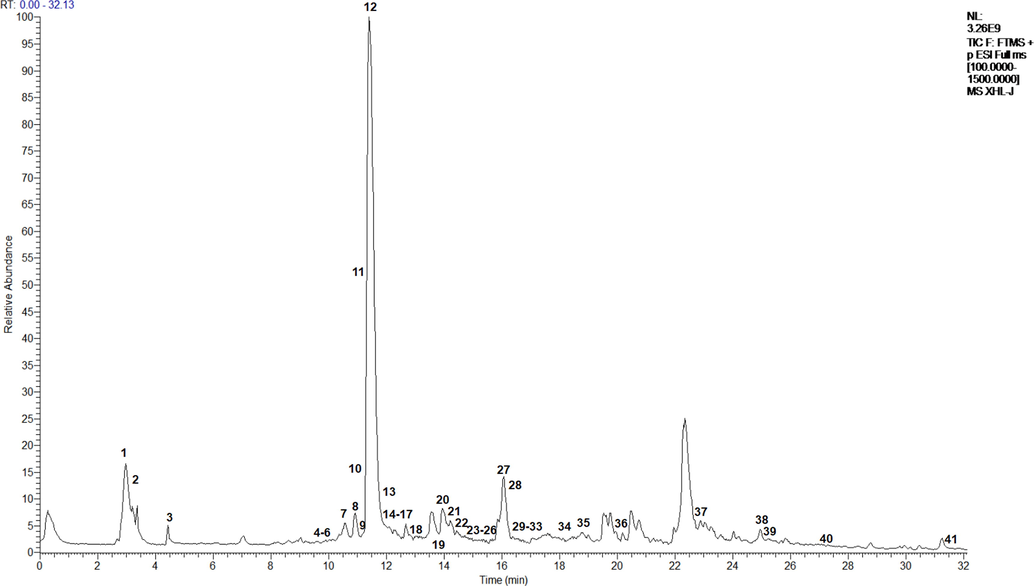

Next, the chemical composition of the methanol extract was investigated using UPLC–electrospray ionization–Orbitrap–MS. From the UPLC-MS data (Table 3), 41 bioactive substances were identified by matching of molecular ions and fragment ions with the literature. The structures of the identified compounds are shown in Fig. 4. The UPLC–MS results obtained in positive ion mode are shown in Fig. 5.

Peak No.

RT (min)

Identification

Molecular formula

Selective ion

Full Scan MS (m/z)

Error (ppm)

MS/MS fragments m/z

Theory

Measured

1

3.01

Betaine

C5H12NO2

[M]+

118.0868

118.0879

−9.3

59.0744, 58.0665

2

3.10

Proline

C5H9NO2

[M + H] +

116.0712

116.0722

−8.6

70.0666, 68.8472

3

4.38

Nicotinic acid

C6H5NO2

[M + H] +

124.0399

124.0408

−7.3

96.0461, 80.0511

4

10.01

Tetramethylpyrazine

C8H12N2

[M]+

137.1079

137.1089

−7.3

136.0233, 121.0414, 94.9452, 55.9358

5

10.13

Narcotolinogendiol

C21H25NO7

[M]+

403.1631

403.1620

2.7

404.1650

6

10.43

Magnocurarine

C19H24NO3

[M]+

314.1756

314.1779

−7.3

269.1201, 237.0937

7

10.59

Saulatine

C22H23NO6

[M + H] +

398.1604

398.1614

−2.5

383.1591, 382.1555, 367.1342

8

10.94

1,2-Dehydroreticuline

C19H22NO4

[M]+

328.1549

328.1571

−6.7

329.1596, 284.1023, 251.0726

9

11.15

Xylopine

C18H17NO3

[M + H] +

296.1287

296.1299

−4.1

281.1074, 280.0989, 103.0919

10

11.21

Northalifoline

C10H11NO3

[M + H] +

194.0817

194.0835

−9.3

177.0569, 163.0795

11

11.27

Canadaline

C21H23NO5

[M + H] +

370.1654

370.1685

−8.4

325.1109

12

11.40

Magnoflorine

C20H24NO4

[M]+

342.1705

342.1726

−6.1

297.1151, 282.0916, 265.0885, 237.0936

13

11.77

Reticuline

C19H23NO4

[M + H] +

330.1705

330.1731

−7.9

299.1309, 192.1039, 175.0773, 143.0511, 137.0612

14

12.12

Bulbocapnine

C19H19NO4

[M + H] +

326.1392

326.1419

−8.3

325.1326, 310.1117

15

12.15

Cassythicine

C19H19NO4

[M + H] +

326.1392

326.1420

−8.6

311.1172, 297.1127

16

12.24

6-Ethoxychelerythrine

C23H23NO5

[M + H] +

394.1654

394.1678

−6.1

362.1390, 347.1151, 330.1127, 318.1125

17

12.78

Stepharotine

C21H25NO5

[M + H] +

372.1811

372.1815

−1.1

356.1521, 340.1572

18

13.07

Corydaldine

C11H13NO3

[M + H] +

208.0974

208.0991

−8.2

163.0217, 151.0769, 120.9822

19

13.78

Tetrahydropapaverine

C20H25NO4

[M]+

343.1784

343.1769

4.4

342.1736, 299.1307, 267.0962, 237.0941

20

13.93

Menisperine

C21H26NO4

[M]+

356.1862

356.1891

−8.1

311.1311, 296.1086, 279.1047

21

14.26

Demethyleneberberine

C19H18NO4

[M]+

324.1236

324.1264

−8.6

308.0968, 280.0999

22

14.60

Tetrahydropalmatine

C21H25NO4

[M + H] +

356.1891

356.1862

8.1

308.9017, 192.1038

23

15.04

Palmatine

C21H22NO4

[M]+

352.1549

352.1583

−9.7

337.1365, 322.1189, 321.1151, 278.5688

24

15.07

Papaverine

C20H21NO4

[M]+

339.1471

339.1457

4.1

340.1495, 323.1195, 163.0879, 69.0714

25

15.44

Stepharine

C18H19NO3

[M]+

297.1365

297.1340

8.4

282.1151, 267.1234

26

15.79

Protopine

C20H19NO5

[M + H] +

354.1341

354.1361

−5.6

353.1545, 190.4528, 163.0977

27

16.07

Berberrubine

C19H16NO4

[M + H] +

323.1158

323.1178

−6.2

322.1105, 308.0949, 294.1162

28

16.20

Lycoranine B

C18H13NO4

[M + H] +

308.0923

308.0945

−7.1

294.1139, 279.1612

29

16.31

Lindoldhamine

C34H36N2O6

[M]+

568.2573

568.2537

6.3

122.0592

30

16.52

Jatrorrhizine

C20H20NO4

[M]+

338.1392

338.1418

−7.7

338.1421, 322.1110, 308.0945, 294.1147

31

16.75

Dehydrocorydaline

C22H24NO4

[M]+

366.1705

366.1730

−6.8

351.1504, 336.1343

32

16.84

Columbamine

C20H20NO4

[M]+

338.1392

338.1418

−7.7

338.1418, 322.1097, 308.0960, 294.1166

33

17.36

Sanguinarine

C20H14NO4

[M]+

332.0923

332.0952

−8.7

304.1008

34

18.45

Berberine

C20H18NO4

[M + H] +

337.1314

337.1341

−8.0

321.1232, 308.1119

35

19.07

N-Methylasimilobine

C18H19NO2

[M]+

281.1416

281.1384

11.4

282.1415

36

20.10

Skimmianine

C14H13NO4

[M + H] +

260.0923

260.0945

−8.5

261.0943, 245.0707, 227.0598

37

22.94

Armepavine

C19H23NO3

[M]+

313.1678

313.1652

8.3

107.0870

38

24.96

(4R,6aR)-4-Hydroxyromerine

C18H17NO3

[M]+

295.1208

295.1214

−2.0

281.1086

39

25.18

2-Hydroxylinoleic acid

C18H32O3

[M + H] +

297.2430

297.2415

5.0

281.1083

40

27.14

2-Hydroxylinolenic acid

C18H30O3

[M + H] +

294.2195

294.2175

6.8

293.2139, 67.0556

41

31.44

Linoleic acid

C18H32O2

[M]+

280.2402

280.2391

3.9

279.2347, 261.2236, 67.0557

Chemical structures of the compounds identified in the methanol extract of Plagiorhegma dubia.

UPLC–MS results acquired in positive ion mode for the methanol extract of Plagiorhegma dubia.

The main component of PD was magnoflorine, followed by berberrubine, and then betaine. Berberine and jatrorrhizine were also identified, but with low contents. These results are consistent with those from a report by Ishikawa (Ishikawa et al., 1978). However, they are inconsistent with previous reports that PD is rich in berberine or jatrorrhizine. It is possible that the results of this study differs from those in some previous studies because those studies used thin-layer chromatography, which is not precise. The use of different developing solvents can also affect the results. Additionally, because the molecular weight and polarity of magnoflorine (an aporphine alkaloid) are very close to those of berberine and jatrorrhizine (protoberberine alkaloids), misinterpretation of the results is possible. Furthermore, samples of the same herb from different origins could have different compositions (Kim et al., 2010). The composition could also be affected by factors such as herb cultivation conditions, harvesting, and processing. All of these factors could lead to researchers to different conclusions.

The main components of CC are berberine, coptisine, epiberberine, berberrubine, jatrorrhizine, and magnoflorine. Apart from coptisine and epiberberine, the same main components were detected in PD. This suggests that PD could be used as a substitute for CC.

In the UPLC–MS results, peak 1 (m/z 118.0879) had a fragment ion at m/z 59.0744 resulting from elimination of −CH2COOH. A fragment ion at m/z 58.0665 originated from the ion at m/z 59.0744, and was related to H loss. These results indicated that peak 1 was betaine (Zengin et al., 2018). Peak 2 with a [M + H]+ ion at m/z 116.0722 was presumed to be proline. The peak at m/z 70.0666 was related to loss of a carboxyl group in the MS2 spectrum (Zengin et al., 2019). Peak 3 had a [M]+ ion at m/z 124.0408 and its main fragment ions were at m/z 96.0461 ([M−CHN]+) and 80.0511 ([M−CHN−OH + H]+). These results were characteristic of nicotinic acid (Zhang et al., 2018). Peak 4 at m/z 137.1089 had a MS2 ions at m/z 121.0414 ([M−CH3]+) and 94.9452 ([M−CH3CN]+), and was identified as tetramethylpyrazine (Ren et al., 2019). The precursor ion [M]+ of peak 5 appeared at m/z 403.1620 and its main fragment ion was at m/z 404.1650 ([M + H]+), which corresponded to narcotolinogendiol (Menéndez-Perdomo et al., 2021). Peak 6 had a [M]+ ion at m/z 314.1779 and its main fragment ions were at m/z 269.1201 ([M−3CH3]+) and 237.0937 ([M−3CH3−2OH + 2H]+). These results were characteristic of magnocurarine (Li et al., 2017). Peak 7 (m/z 398.1614) generated fragment ions at m/z 382.1555 and 367.1342, which were related to loss of –CH3 and –2CH3, respectively. Thus, peak 7 was assigned to saulatine (Li et al., 2011). Peak 8 at m/z 328.1571 had a MS2 ions at m/z 329.1596 ([M + H]+) and 284.1023 ([M−3CH3]+), and was tentatively assigned as 1,2-dehydroreticuline (Menéndez-Perdomo et al., 2021). Peak 9 (m/z 296.1299) was identified as xylopine based on the typical fragment ions at m/z 281.1074 ([M + H−CH3]+) and 280.0989 ([M−CH3]+) (Ferraz et al., 2019). The main fragment ions of peak 10 (m/z 194.0835) appeared at m/z 177.0569 ([M−OH + H]+) and 163.0795 ([M−OH + H−CH2]+), and this peak was assigned as northalifoline (Wu et al., 2017).

Peak 11 at m/z 370.1685 had a MS2 ion at 325.1109 ([M + H−3CH3]+), and was tentatively assigned as canadaline. The main fragment ions of peak 12 (m/z 342.1726) appeared at m/z 297.1151 ([M−H2O−CHN]+) and 282.0916 ([M−H2O−CHN−CH3]+), and this peak was assigned as magnoflorine (Yang et al., 2021). Peak 13 (m/z 330.1731) was identified as reticuline with major MS2 ions at m/z 299.1309 and 192.1039 were for the loss of −2CH3 and −C8H8O2 (Conceição et al., 2020). Peak 14 at m/z 326.1419 had a MS2 ion at m/z 310.1117 ([M−CH3]+), and was tentatively assigned as bulbocapnine in agreement with a previous report (Bougoffa-Sadaoui et al., 2016). Peak 15 (m/z 326.1420) was identified as cassythicine with major MS2 ions at m/z 311.1172 and 297.1127 for the loss of –CH2 and –2CH2 (Ndi et al., 2016). Peak 16 at m/z 394.1678 had MS2 ions at m/z 362.1390 and 347.1151 for the loss of −H−CH2O, and −H−CH2O−CH3, respectively, and was identified as 6-ethoxychelerythrine (Rao et al., 2022). The precursor ion [M]+ of peak 17 appeared at m/z 372.1815 and its main fragment ions were at m/z 356.1521 ([M−CH3]+) and 340.1572 ([M−CH3−OH + H]+), which corresponded to stepharotine. Peak 18 (m/z 208.0991) was identified as corydaldine based on the typical fragment ion at m/z 163.0217 ([M−CO−H−CH3]+) (Kilic et al., 2021). Peak 19 (m/z 343.1769) was identified as tetrahydropapaverine based on the typical fragment ions at m/z 342.1736 ([M−H]+) and 299.1307 ([M−3CH3 + H]+) (Lopes et al., 2022). Peak 20 at m/z 356.1891 had MS2 ions at m/z 311.1311, 296.1086 and 279.1047 for the loss of −3CH3, −4CH3 and −4CH3-OH, respectively, and was identified as menisperine (Jiao et al., 2018).

Peak 21 (m/z 324.1264) gave fragment ions at m/z 308.0968 and 280.0999, which was correlated with the loss of −OH + H and −OH + H−2CH2. These results indicated that peak 21 was demethyleneberberine (Wang et al., 2021). Peak 22 at m/z 356.1862 had a MS2 ion at m/z 308.9017 ([M−H−3CH3]+), and was assigned as tetrahydropalmatine (Cheng et al., 2019). Peak 23 had a [M + H]+ peak at m/z 352.1583 that generated a main fragment ions at m/z 337.1365 and 322.1189, and was related to −CH3 and −2CH3 loss. These results indicated that peak 23 was palmatine (da Silva Mesquita et al., 2022). Peak 24 had a [M]+ peak at m/z 339.1457 that generated a main fragment ions at m/z 340.1495 ([M + H]+) and 323.1195 ([M−CH3−H]+), which was characteristic of papaverine (Elkousy et al., 2021). Peak 25 (m/z 297.1340) was identified as stepharine with major MS2 ions at m/z 282.1151 and 267.1234 for the loss of −CH3 and −2CH3 (Shi et al., 2021). Peak 26 had a [M + H]+ peak at m/z 354.1361 that generated a main fragment ion at m/z 163.0977 ([C9H7O3]+), which was characteristic of protopine (Siatka et al., 2017). Peak 27 at m/z 323.1178 had a MS2 ions at m/z 308.0949 ([M + H−CH3]+) and 294.1162 ([M + H−CHO]+), and was tentatively assigned as berberrubine (Li et al., 2022). The main fragment ions of peak 28 (m/z 308.0945) appeared at m/z 294.1139 ([M + H−CH2]+) and 279.1612 ([M + H−CHO]+), and this peak as lycoranine B (Wang et al., 2009). Peak 29 (m/z 568.2537) was identified as lindoldhamine based on the typical fragment ion at m/z 122.0592 ([C7H6O2]+). Peak 30 (m/z 338.1418) gave fragment ions at m/z 322.1110, 308.0945 and 294.1147, which were correlated with the loss of + H−OH, +H−OH−CH2 and + H−OH−2CH2. These results presumed that peak 30 was jatrorrhizine (Li et al., 2022).

Peak 31 with [M]+ at m/z 366.1730 was identified as dehydrocorydaline based on the typical fragment ions at m/z 351.1504 ([M−CH3]+) and 336.1343 ([M−2CH3]+) (Mei et al., 2022). Peak 32 at m/z 338.1418 had a MS2 ions at m/z 322.1097 ([M + H−OH]+), 308.0960 ([M + H−OH−CH2]+) and 294.1166 ([M + H−OH−2CH2]+), and was tentatively assigned as columbamine (Li et al., 2022). Peak 33 at m/z 332.0952 had a MS2 ion at m/z 304.1008 ([M + H−CHO]+), and was tentatively assigned as sanguinarine (Wu et al., 2019). The main fragment ion of peak 34 (m/z 337.1341) appeared at m/z 321.1232 ([M−CH3]+) and 308.1119 ([M + H−2CH3]+), and this peak was assigned as berberine (Chen et al., 2019). Peak 35 at m/z 281.1384 had a MS2 ion at m/z 282.1415 ([M + H]+), and was assigned as N-Methylasimilobine (Paz et al., 2019). Peak 36 (m/z 260.0945) had MS2 ions at m/z 245.0707 ([M + H−CH3]+) and 227.0598 ([M + H−CH3−H2O]+), and was identified as skimmianine using previously reported data (Karahisar et al., 2019). Peak 37 at m/z 313.1652 had a MS2 ion at m/z 107.0870 ([C7H7O]+), and was tentatively assigned as armepavine in agreement with a previous report (Müller et al., 2021). Peak 38 had a [M]+ peak at m/z 295.1214 that generated a main fragment ion at m/z 281.1086 ([M + H−CH3]+), which was characteristic of (4R,6aR)-4-hydroxyromerine (Cai et al., 2016). Peak 39 (m/z 297.2415) generated fragment ions at m/z 281.1083, which was related to loss of −CH3. Thus, peak 39 was assigned to 2-hydroxylinoleic acid (Kerboua et al., 2021). Peaks 40 and 41 were identified as 2-hydroxylinolenic acid and linoleic acid based on the matching fragment ion ([M−H]+ and [C5H7]+) with references (Kerboua et al., 2021; Yang et al., 2017).

3.2 In vitro antioxidant activity

Free radicals are chemically very active because of their unpaired electrons. Free radicals present in the human body can be beneficial if they are controlled but detrimental when their levels become excessive and they are uncontrolled. The free radical scavenging ability of a compound can be assessed using DPPH· and ABTS assays, β-carotene bleaching experiments, and hydroxyl radical and superoxide radical assays.

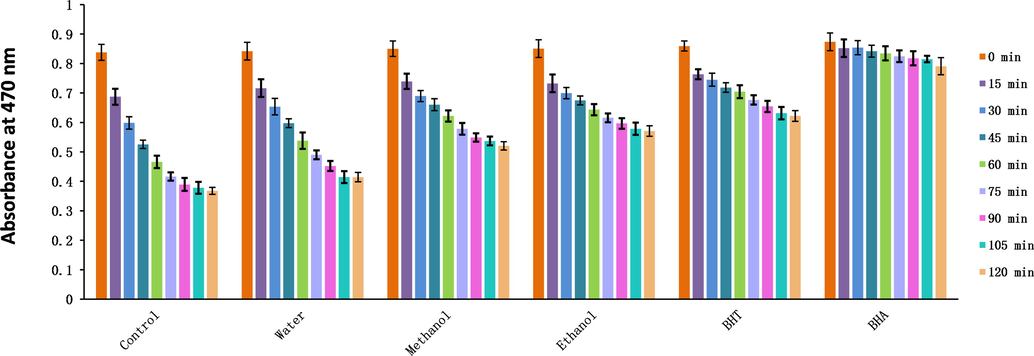

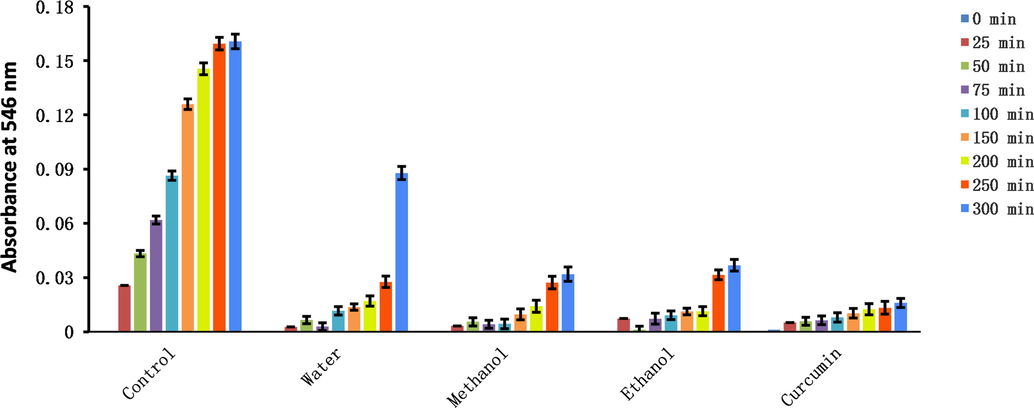

In the present study, the ethanol extract showed the best DPPH· and ABTS scavenging abilities, followed by the methanol extract. The differences between the methanol and ethanol extracts were not significant. Magnoflorine, which was a major component of the methanol extract, has a strong DPPH· scavenging ability (Naseer et al., 2015) and could explain the excellent performance of the methanol extract. A 70% ethanol extract of CC also showed excellent DPPH·, ABTS, and superoxide radical scavenging abilities (Seo et al., 2013, Ban et al., 2011). Among the PD extracts, the aqueous extract had the best hydroxyl radical scavenging ability and the methanol extract had the best superoxide radical scavenging ability (Table 4). The performance of the methanol extract was attributed to its content of berberrubine, which is a powerful hydroxyl radical scavenger (Jang et al., 2009). The aqueous extract of CC also exhibited good hydroxyl radical scavenging ability (Li et al., 2015). The ethanol extract of PD had the strongest ability to inhibit β-carotene bleaching (Table 5, Fig. 6). a-d Columns with different superscripts indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05). DPPH·: 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl; ABTS: 2,2′-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) diammonium salt; HClO: Hypochlorous acid; TE: Trolox equivalent; BHT: Butylated hydroxytoluene; Trolox: 6-Hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid; a-e Columns with different superscripts indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05). AAC: Antioxidant activity coefficient; FRAP: Ferric-reducing antioxidant power; CUPRAC: Cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity; H2O2: Hydrogen peroxide; BHT: Butylated hydroxytoluene; BHA: Butyl hydroxyanisole; EDTANa2: Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt; EDTAE: EDTA equivalent; TE: Trolox equivalent; FAE: Ferulic acid equivalent.

Extracting solvents

DPPH·(mg TE/g extract)

ABTS (mg TE/g extract)

Hydroxyl radical (%, 2500 μg/mL)

Superoxide radical (%, 2143 μg/mL)

HClO (mg TE/g extract)

Singlet oxygen (%, 2000 μg/mL)

Water

12.7 ± 0.8c

133.2 ± 4.8d

47.1 ± 3.5b

0.4 ± 0.0d

13.7 ± 0.2c

25.0 ± 2.4c

Methanol

17.2 ± 1.7c

270.7 ± 25.3c

25.7 ± 2.8c

18.5 ± 1.9b

23.0 ± 1.1b

40.8 ± 3.3b

Ethanol

21.1 ± 2.5c

276.5 ± 24.0c

4.4 ± 0.5d

13.9 ± 1.4c

13.4 ± 0.3c

21.4 ± 1.3c

L-ascorbic acid*

1092.1 ± 44.1a

1031.9 ± 32.3a

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

BHT*

215.1 ± 2.3b

750.0 ± 5.1b

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

Curcumin*

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

45.6 ± 0.8a

N.T.

N.T.

Trolox*

1000.0 ± 11.4a

1000.6 ± 30.3a

98.3 ± 0.2a

N.T.

1000.0 ± 7.8a

N.T.

Ferulic acid*

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

95.3 ± 3.1a

Extracting solvents

FRAP (mg TE/g extract)

CUPRAC (mg TE/g extract)

Iron chelating (%, 2500 μg/mL)

Copper chelating (mg EDTAE/g extract)

H2O2 (mg FAE/g extract)

β-Carotene bleaching AAC

Water

132.5 ± 0.5d

148.5 ± 11.6d

27.7 ± 0.5b

106.8 ± 3.6c

29.3 ± 2.5c

129.8 ± 13.3e

Methanol

155.5 ± 0.5c

168.9 ± 13.6d

21.7 ± 0.6c

168.5 ± 3.4b

107.8 ± 6.7a

331.2 ± 22.6d

Ethanol

148.3 ± 0.5c

197.0 ± 18.3c

7.8 ± 0.6d

<20.8d

88.1 ± 7.2b

602.1 ± 7.2c

L-ascorbic acid*

980.0 ± 10.0a

1400.0 ± 10.0b

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

BHT*

310.3 ± 3.0b

1570.0 ± 10.0a

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

877.7 ± 4.9a

BHA*

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

N.T.

762.0 ± 6.8b

EDTANa2*

N.T.

N.T.

98.5 ± 1.2a

1001.4 ± 45.8a

N.T.

N.T.

Changes in the absorbance of three solvent extracts of Plagiorhegma dubia over time measured using the β-carotene bleaching method. BHT: Butylated hydroxytoluene; BHA: Butyl hydroxyanisole.

Oxidizing substances are irritating, corrosive, and cytotoxic, and can even be carcinogenic. Consequently, it is necessary to identify effective scavengers. Among the three extracts, the methanol extract showed the best scavenging capacities for H2O2, HClO, singlet oxygen, and NO (Tables 4 and 5, Fig. 7).

Changes in absorbance of three solvent extracts of Plagiorhegma dubia over time measured using the nitric oxide scavenging method.

The presence of transition metals in the human body can induce oxidative stress. Transition metals are often bound to biological macromolecules, and hydroxyl radicals can be generated at the binding site. Generated hydroxyl radicals will first directly attack the biomacromolecule to which the transition metal is attached. As an example of transition metals in the human body, iron and copper ions frequently appear in senile plaques in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients (Miller et al., 2006). In the present study, the aqueous extract of PD showed the best ability to chelate iron and the methanol extract of PD showed the best ability to chelate copper (Table 5). Therefore, the PD methanol extract could be used as a copper chelator to inhibit oxidative stress.

The FRAP and CUPRAC assays are important for determining the redox capacity of a sample. In this study, the FRAP assay was carried out under low pH conditions and the CUPRAC assay under neutral conditions. The two assays were performed simultaneously to better reflect the antioxidant ability of the samples. The methanol extract of PD had the highest FRAP value, and the ethanol extract of PD had the highest CUPRAC value (Table 5). The aqueous extract of CC also had good FRAP and CUPRAC values (Meng et al., 2020; Li et al., 2015).

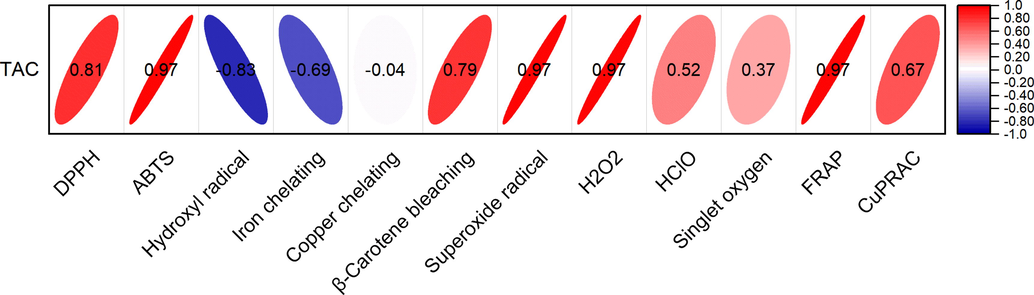

Pearson’s correlations were calculated between the total alkaloid content and antioxidant activities. Except for the hydroxyl radical and metal ion chelation results, all in vitro antioxidant experimental results were highly positively correlated with the total alkaloid content (Fig. 8). Therefore, the antioxidant capacity of PD is derived from the alkaloids it contains.

Pearson’s correlation between the total alkaloid content and antioxidant activities.

After considering the results for the yield, total alkaloid content, and in vitro antioxidant experiments, the methanol extract of PD was selected to study the effect on the oxidative stability of cooking oils, liver injury, and diabetes.

3.3 Oxidative stability of cooking oils

Fried foods are popular because of their sensory characteristics. However, the high temperature applied during frying results in oxidation and polymerization of the oil, and degrades the character of the fried food (Marmesat, et al., 2012). Antioxidants can be added to oils to effectively improve the stability; however, the use of synthetic antioxidants poses risks (Xu et al., 2021). Consequently, natural antioxidants are in demand in the food industry.

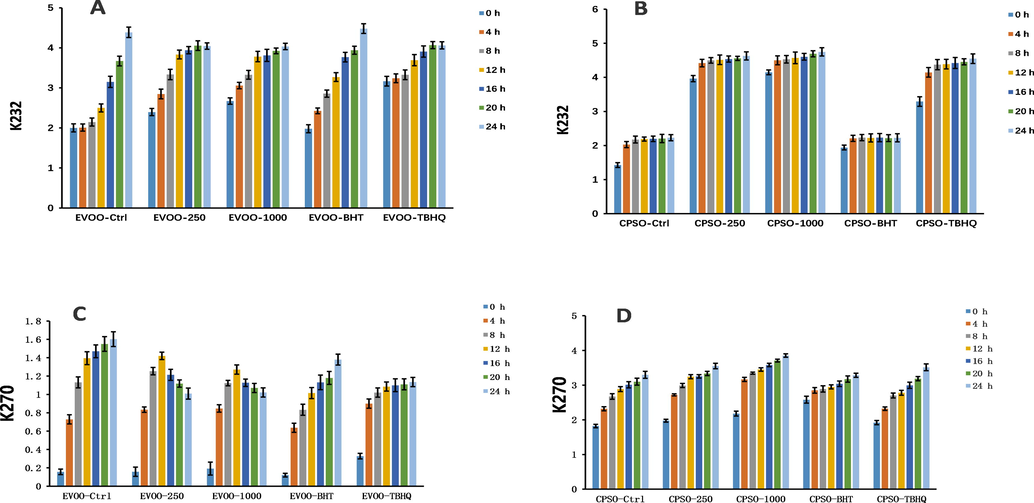

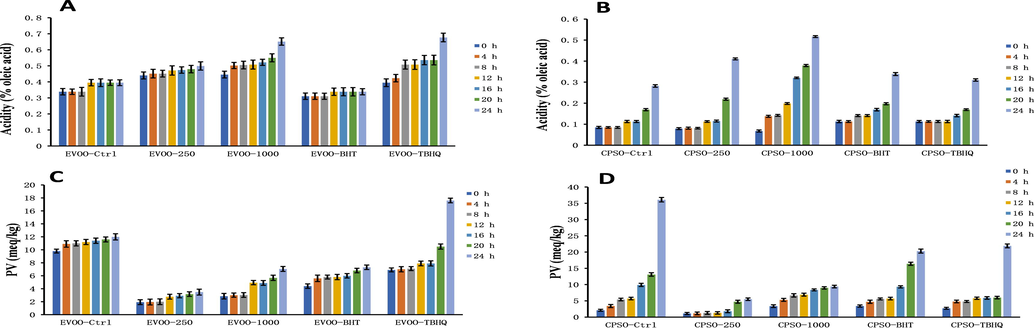

The primary oxidation state of oil is commonly assessed using peroxide and acid values. Additionally, the K232 and K270 values are used to evaluate the degree of lipid primary and secondary oxidation (Malheiro et al., 2013). In the present study showed that addition of the methanol extract of PD at both tested doses to extra virgin olive oil decreased the K270 value, and the effect was comparable to that of tertiary butylhydroquinone (TBHQ) (Fig. 9). Interestingly, addition of PD methanol extract increased the acid values for both oils (Fig. 10). This is because most alkaloids in plants are combined with organic acids to form salts, and only a few weakly alkaline alkaloids exist in a free state. In the experiments to determine the acid value of the oils, alkaloid salts contained in the methanol extract will react with KOH to form alkaloids in a free state, and this will consume KOH. Therefore, the measured acid value will not reflect the true acid value of free fatty acids. For the peroxide value, addition of the PD methanol extract at both tested doses gave excellent results, and the peroxide value was much lower than that of the positive control (Fig. 10).

Changes in the K232 and K270 values over time in extra virgin olive oil (A, C) and cold-pressed sunflower oil (B, D) supplemented with BHT, TBHQ, and two doses of a methanol extract of Plagiorhegma dubia. EVOO: Extra virgin olive oil; CPSO: Cold-pressed sunflower oil; BHT: Butylated hydroxytoluene; TBHQ: Tertiary butylhydroquinone. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3).

Changes in the acidity values and peroxide values over time in extra virgin olive oil (A, C) and cold-pressed sunflower oil (B, D) supplemented with BHT, TBHQ, and two doses of a methanol extract of Plagiorhegma dubia. EVOO: Extra virgin olive oil; CPSO: Cold-pressed sunflower oil; BHT: Butylated hydroxytoluene; TBHQ: Tertiary butylhydroquinone. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3).

In the present study showed that addition of a methanol extract of PD has a good antioxidant effect in cooking oils and a very good effect on reducing the peroxide value. Because the peroxide value of edible fats and oils is a key indicator of food quality (Endo., 2018), the methanol extract of PD should be investigated further for use as an antioxidant in cooking oils.

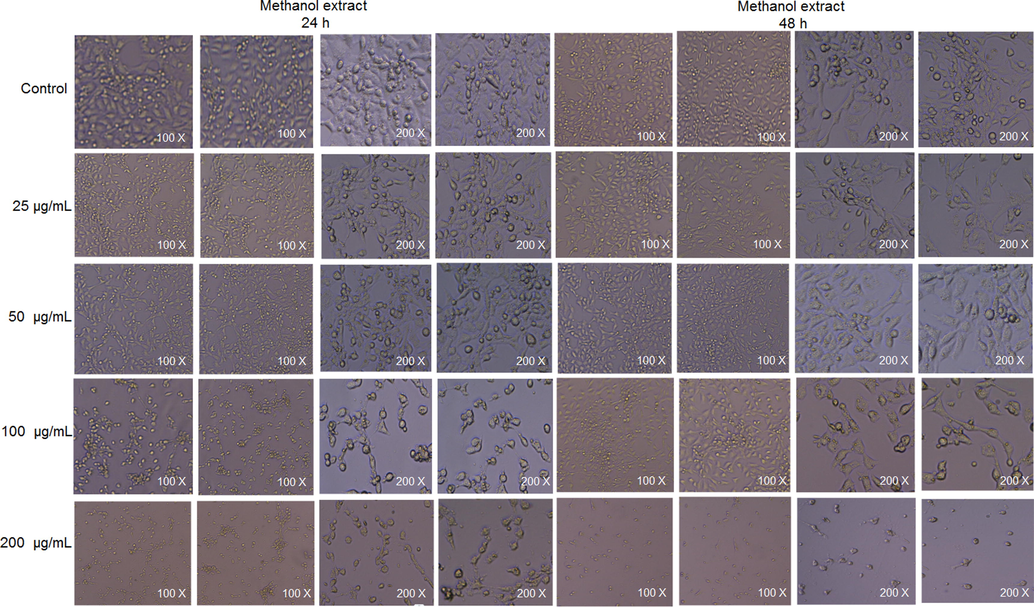

3.4 Cell viability and oral acute toxicity study

The cellular morphology was evaluated after treatment with methanol extracts of PD at different concentrations for 24 or 48 h (Fig. 11). The methanol extract showed minimal cytotoxicity at all four tested concentrations. However, the cytotoxicity did increase slightly over time (Table 6). Overall, these results show that the methanol extract of PD is relatively safe and could be used as an antioxidant in cooking oil. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 5).

Cellular morphology after treatment with methanol extracts of Plagiorhegma dubia at different concentrations for 24 and 48 h.

Methanol extract (μg/mL)

Cell survival rate of TM3 cells (%)

24 h

48 h

0

100.0 ± 1.9a

100.0 ± 1.1a

25

95.4 ± 1.1b

92.2 ± 2.2b

50

93.5 ± 1.4b

90.8 ± 0.9b

100

87.3 ± 1.8c

84.8 ± 2.6c

200

84.7 ± 1.4c

81.7 ± 1.3c

The cytotoxicity of CC is derived from its content of berberine and palmatine, and its toxicity to cells is dose-dependent with the toxicity increasing at higher concentrations. PD also contains these two alkaloids, which is consistent with the results of PD cell experiments. Magnoflorine is the most abundant component in PD, and current research suggests that it is a relatively safe compound that is not toxic to most cells (Xu et al., 2020). Betaine is also a safe natural product (Tsai et al., 2015). Berberrubine is potentially cytotoxic to human renal cell lines (HK-2 and HEK293) (Yang et al., 2016). Therefore, the low cytotoxicity of PD could be explained by the facts that its major components are non-toxic magnoflorine and betaine, and that the contents of the more toxic berberrubine, berberine, and palmatine are relatively low.

In an oral acute toxicity study of the methanol extract of PD, no mice died. These results show that the toxicity of the methanol extract is very low. In a previous study, an acute toxicity test of CC showed that berberine was the most toxic compound, and palmatine was slightly less toxic (Yi et al., 2013). Another study showed that berberine, palmatine, and jatrorrhizine were detected in the brain and heart tissues of mice after oral administration of CC extracts. The concentrations of these compounds in the tissues increased in a non-linear fashion with increases in the dose (Ma et al., 2010). Although PD also contains these three alkaloids, their contents are low and this could explain why no mice died in the oral acute toxicity study. Although berberrubine was detected as a major component in the PD extract, and berberrubine has some toxicity in vitro, it is rapidly converted into non-toxic metabolites after oral administration to rats (Yang et al., 2016).

3.5 Hepatoprotective activity

The liver has important metabolic functions in vertebrates, with its core function being the synthesis of many low and high molecular weight compounds that are needed to maintain normal functioning of the body. When it is damaged by diseases, drugs, viruses, or chemicals, the fluidity of the liver cell membrane decreases and its permeability increases, which results in release of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase. Liver injury can also cause impaired binding and excretion of bilirubin in bile, which can lead to an increase in total bilirubin in blood (Mahmoud et al., 2014).

In this research, rats were injected with d-galactosamine to induce significant liver injury within 24 h. Liver damage was proven by an increase in the mass of the rat liver, increased liver enzyme activity, increased total bilirubin, and decreased albumin levels. d-Galactosamine is an effective hepatotoxic drug that causes liver damage (necrosis and inflammation) very similar to human viral hepatitis (Wills and Asha., 2006). Viral hepatitis is thought to be the main cause of liver cirrhosis and liver cancer (Williams., 2006).

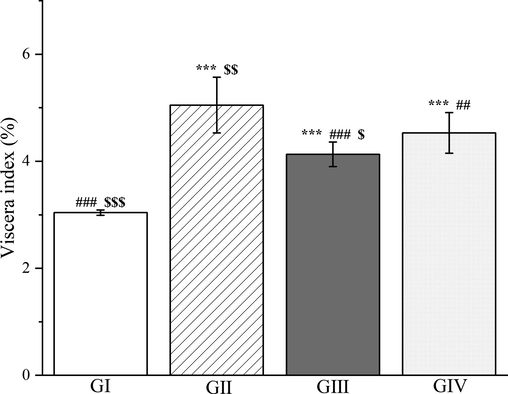

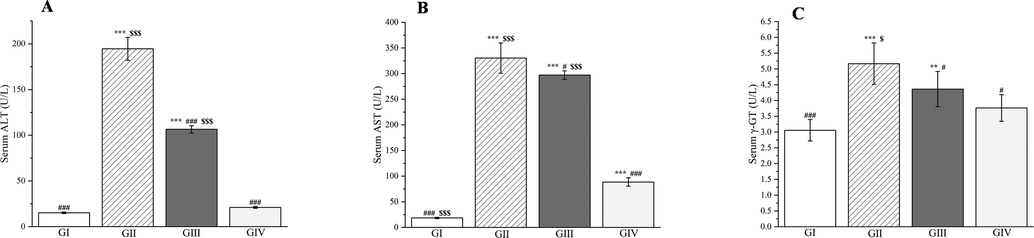

To evaluate the effect of the methanol extract of PD, it was fed to rats daily for 7 days by gavage, and this was followed by d-galactosamine injection. The methanol extract pretreatment significantly reduced in the rats compared with group II (p < 0.001, Fig. 12), and performed significantly better than silymarin (p < 0.05, Fig. 12). The methanol extract pretreatment also significantly decreased the activity of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase by 45.27%, 10.05% and 15.59%, respectively, compared with group II (p < 0.05, Fig. 13). The results here were similar to those obtained with silymarin.

The outcomes of treatment with a Plagiorhegma dubia methanol extract on the hepatic viscera index in rats with liver injury. GI: Control group, GII: D-GalN group, GIII: D-GalN + PD300 group, GIV: D-GalN + SMN group. PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; D-GalN: D-Galactosamine; SMN: Silymarin. Significantly different from the control group at *** p < 0.001. Significantly different from the D-GalN group at ## p < 0.01 and ### p < 0.001. Significantly different from the D-GalN + SMN group at $ p < 0.05, $$ p < 0.01 and $$$ p < 0.001. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8).

Effects of Plagiorhegma dubia on serum alanine aminotransferase (A), aspartate aminotransferase (B), and γ-GT (C) in rats with liver injury. GI: Control group, GII: D-GalN group, GIII: D-GalN + PD300 group, GIV: D-GalN + SMN group. PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; D-GalN: D-Galactosamine; SMN: Silymarin; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; γ-GT: γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase. Significantly different from the control group at ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Significantly different from the D-GalN group at # p < 0.05 and ### p < 0.001. Significantly different from the D-GalN + SMN group at $ p < 0.05 and $$$ p < 0.001. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8).

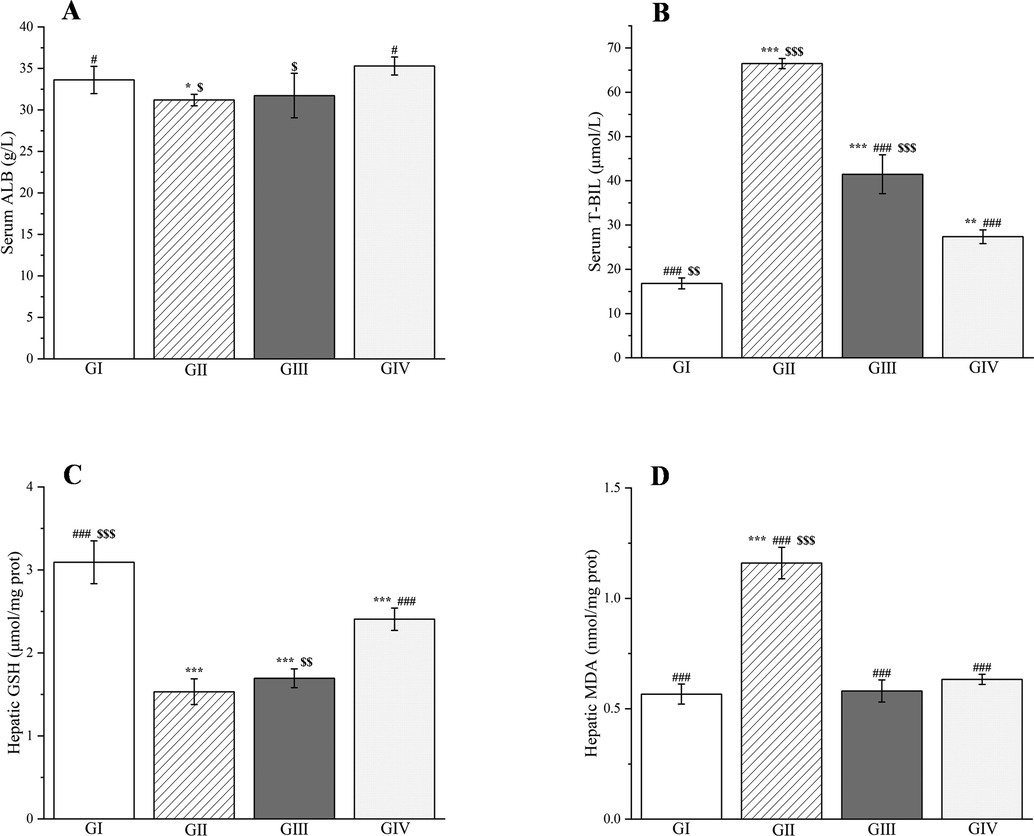

In addition to liver enzymes, the contents of albumin and total bilirubin in serum are also crucial indicators of liver function. This study found that neither silymarin nor the methanol extract significantly altered the albumin levels 24 h after d-galactosamine injection. Only group II showed a significant difference (p < 0.05, Fig. 14A). However, a significant increase in the total bilirubin content was seen in the rats compared with group I (p < 0.001, Fig. 14B). Pretreatment with methanol extract resulted in a 37.62% decrease in the total bilirubin content compared with group II (p < 0.001, Fig. 14B).

Effects of Plagiorhegma dubia on serum albumin (A), total bilirubin (B) and hepatic glutathione (C), malondialdehyde (D) in rats with liver injury. GI: Control group, GII: D-GalN group, GIII: D-GalN + PD300 group, GIV: D-GalN + SMN group. PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; D-GalN: D-Galactosamine; SMN: Silymarin; ALB: Albumin; T-BIL: Total bilirubin; GSH: Glutathione; MDA: Malondialdehyde. Significantly different from the control group at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Significantly different from the D-GalN group at # p < 0.05 and ### p < 0.001. Significantly different from the D-GalN + SMN group at $ p < 0.05, $$ p < 0.01 and $$$ p < 0.001. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8).

As well as inducing liver injury, d-galactosamine injection increased production of ROS and reduced the potency of antioxidants in the body. This resulted in an increase in the malondialdehyde level and a decrease in the glutathione level in the liver (p < 0.001, Fig. 14C and D). Compared with group II, the methanol extract decreased the malondialdehyde level by 49.98%. Similar results were obtained for group I (51.19% reduction) and with silymarin (45.43% reduction). However, the changes in the glutathione levels were not significant (p > 0.05, Fig. 14D).

According to the literature, CC has a good protective effect on carbon tetrachloride-induced liver injury in mice, and it can reduce alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total bilirubin, and malondialdehyde levels, and increase the glutathione level (Meng et al., 2020). Both betaine and berberrubine, the two main components of PD, can be used to treat nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. These compounds effectively reduce alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels in mice fed a high-fat diet (Veskovic et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2022). However, berberrubine has hepatotoxicity, which will increase alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase levels (Wang et al., 2020). This may explain why the effect of the methanol extract of PD on decreasing aspartate aminotransferase levels was not obvious compared with the d-galactosamine-treated group.

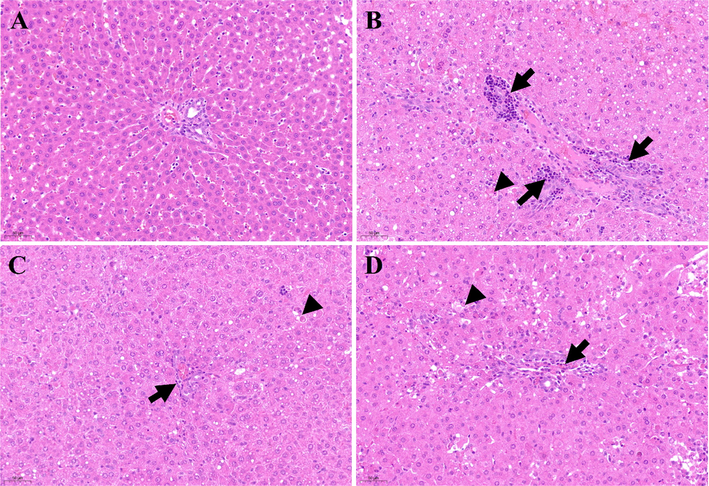

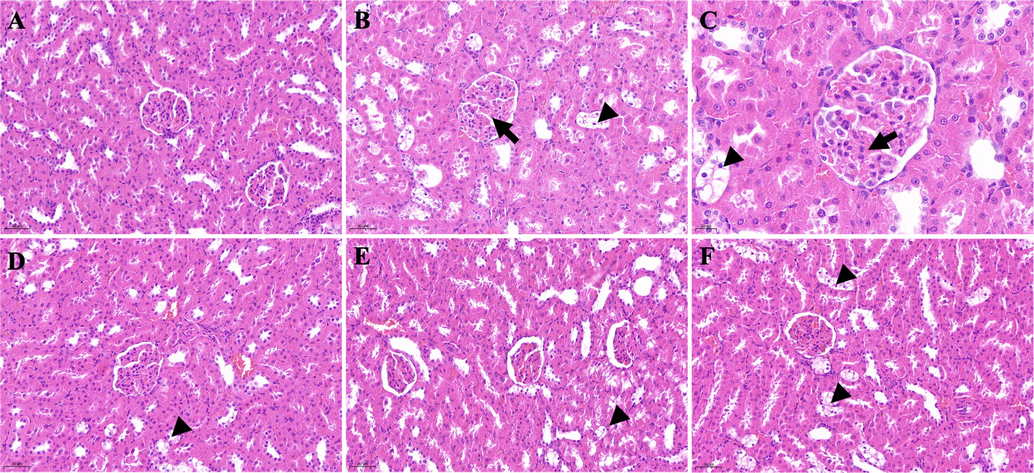

3.6 Histopathological analysis

The livers of rats in group I had a clear histological structure, normal arrangement of hepatocytes, and no inflammatory cell infiltration around the portal area (Fig. 15A). In the rats in group II, the liver tissue structure was disordered, the hepatic cord was not present, the hepatocytes were swollen, the cytoplasm contained lipid droplet-like substances (steatosis), and many inflammatory cells had infiltrated the portal area (Fig. 15B, black arrows). Furthermore, there was scattered single-cell necrosis (Fig. 15B, black arrowhead). Compared with group II, hepatocyte injury in groups III and IV greatly improved. The results for groups III and IV were similar, with both showing a few scattered hepatocytes with mild steatosis and infiltration of few inflammatory cells around the portal area (Fig. 15C and D, black arrows). Single hepatocyte necrosis was still observed in groups III and IV (Fig. 15C and D, black arrowheads). These findings suggest that the methanol extract of PD provided protection when used as a pre-treatment in rats before d-galactosamine injection.

Histological examination of liver sections in different groups (200 × magnification). A: Control group; B: D-GalN group; C: D-GalN + PD300 group; D: D-GalN + SMN group. PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; D-GalN: D-Galactosamine; SMN: Silymarin.

3.7 Antidiabetic activity

Diabetes is the most common metabolic disease worldwide. This disease is characterized by defective insulin secretion or impaired biological action, which both increase blood sugar levels. This has certain effects on the metabolism of essential nutrients in the body. Over time, hyperglycemia can cause chronic damage and dysfunction in multiple tissues, and in particular, in the kidneys, blood vessels, and nerves (Ventura-Sobrevilla et al., 2011). Because synthetic drugs have adverse side effects or contraindications, treatment of diabetes mellitus with herbal and plant-derived compounds has become increasingly important worldwide. The World Health Organization has recommended evaluation of traditional plants and plant-derived compounds for treatment of diabetes (Sellamuthu et al., 2014).

In this research, streptozotocin-induced diabetes in rats was confirmed by increased blood glucose, altered liver and kidney functions, and altered lipid profiles and oxidative stress parameters.

Streptozotocin is a well-known diabetes inducer. Its mechanism of action is selective toxicity to beta cells of the pancreas through the NO free radicals it produces (Moncada et al. 1991).

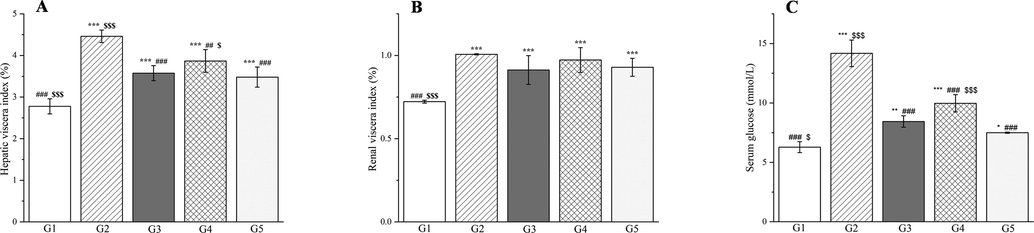

A methanol extract of PD was administered to the rats continuously for 30 days after injection with streptozotocin. Administration of two doses of methanol extract greatly reduced the VI in rats compared with group 2 (group 3 p < 0.001 and group 4 p < 0.01, Fig. 16A), and the results were similar for group 3 and the glibenclamide group (p < 0.05, Fig. 16A). However, the VI did not differ between groups 2–5 (p > 0.05, Fig. 16B). Serum glucose levels were markedly elevated (p < 0.001, Fig. 16C) in group 2 compared with group 1. Meanwhile, the serum glucose levels in groups 3, 4, and 5 were significantly lower (p < 0.001, Fig. 16C) than those in group 2 by 40.47%, 29.65%, and 47.13%, respectively. The effect of the PD extract could be attributed to its content of magnoflorine, betaine, and berberrubine, which can reduce blood sugar levels in humans and rats (Patel et al., 2012; Grizales et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2021). CC can also reduce blood sugar levels (Chandirasegaran et al., 2018).

The outcomes of treatment with a Plagiorhegma dubia methanol extract on the hepatic viscera index (A), renal viscera index (B), and serum glucose (C) in rats with induced diabetes. G1: Control group, G2: DM group, G3: DM + PD150 group, G4: DM + PD300 group, G5: DM + GLB group. PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; DM: Diabetes mellitus; GLB: Glibenclamide. Significantly different from the control group at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM group at ## p < 0.01 and ### p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM + GLB group at $ p < 0.05 and $ p < 0.001. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8).

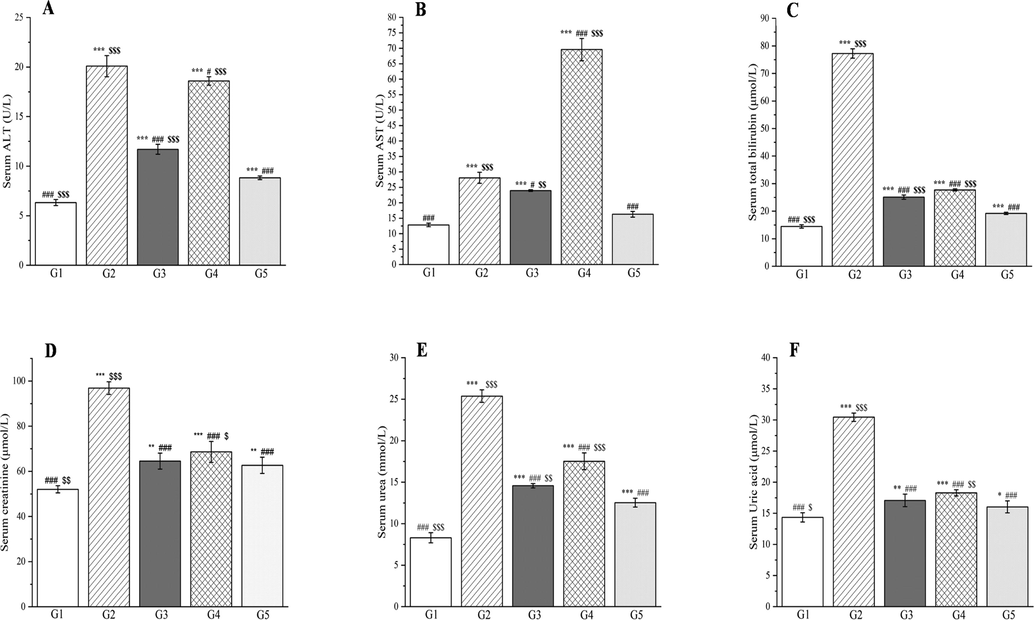

The liver has a critical role in carbohydrate metabolism, glucose uptake and glucose/lipid homeostasis, but diabetes can negatively impact these functions (Kolodziejski et al., 2021). Elevated aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels are characteristic markers of liver injury (Abdallah et al., 2022) and are frequently detected in experimental diabetic rats (Abdelghffar et al., 2022). In the present study, the alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase activities in the group 3 rats were significantly reduced (by 41.76% and 14.77%, respectively) compared with the group 2 rats (p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, Fig. 17A and B). The results in the group 4 rats were even worse, and the aspartate aminotransferase activity was three times that in the group 2 rats. This could also be attributed to the presence of berberrubine in the PD extract. Significantly elevated levels of total bilirubin were observed in rats compared with group I (p < 0.001, Fig. 17C). In groups 3 and 4, reductions in total bilirubin of 67.49% and 64.12%, respectively, were observed compared with group 2 (p < 0.001, Fig. 17C). CC can also reduce alanine aminotransferase, and aspartate aminotransferase levels (Ma et al., 2016).

The outcomes of treatment with a Plagiorhegma dubia methanol extract on serum liver functions and kidney functions in rats with induced diabetes: alanine aminotransferase (A), aspartate aminotransferase (B), total bilirubin (C) and creatinine (D), urea (E), and uric acid (F). G1: Control group, G2: DM group, G3: DM + PD150 group, G4: DM + PD300 group, G5: DM + GLB group. PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; DM: Diabetes mellitus; GLB: Glibenclamide; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: Alanine aminotransferase. Significantly different from the control group at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM group at # p < 0.05 and ### p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM + GLB group at $ p < 0.05, $$ p < 0.01 and $$$ p < 0.001. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8).

Significant elevations of liver enzymes in the rats with induced diabetes mellitus were attributed to streptozotocin-mediated hepatotoxicity (Aldahmash et al., 2016). Therefore, in addition to improving glycemic control, protection of vital organs from damage is an important goal in the treatment of diabetes (Umar et al., 2019). In the present study indicated that treatment with 150 mg/kg BW PD reduced the elevation of liver enzymes in rats with diabetes, improved liver function, and prevented diabetes-induced liver damage.

Diabetic metabolic disorders lead to gluconeogenesis and superfluous protein breakdown and metabolism, this results in hemodynamic variation and glomerular damage, which generates creatinine, urea, and uric acid (Ramachandran et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2018). Compared with group 1, all three markers of renal function in the rats with diabetes were significantly elevated (p < 0.001, Fig. 17D–F). Compared with group 2, the levels of creatinine, urea, and uric acid decreased significantly in groups 3–5 (p < 0.001, Fig. 17D–F). Compared with group 4, the group 3 treatment gave better results that were close to those of the glibenclamide group.

The results obtained with PD treatment could be explained by its content of magnoflorine, which is very effective at reducing urea and creatinine levels in rats with diabetes (Chang et al., 2020). Magnoflorine is also the main component of CC, and CC also reduces the levels of these two kidney injury markers (Yokozawa et al., 2004). In this study, oral treatment with PD at two doses counteracted the renal changes related to metabolic syndrome and reduced the levels of creatinine, urea and uric acid in rats with diabetes, which suggests that PD could be used for treatment of renal injury even in diabetic nephropathy.

Epidemiological surveys have shown that the morbidity and mortality of diabetes are related to atherogenic dyslipidemia and metabolic abnormalities that contribute to macrovascular complications (Ahangarpour et al., 2017). Hyperinsulinemia first induces inactivation of hormone-sensitive lipases, which is followed by excessive deposition of free fatty acids, and promotion of the biosynthesis of LDL cholesterol, VLDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides but a reduction in HDL cholesterol (Movahedian et al., 2010). Castelli’s risk indexes I and II, the atherogenic index of plasma, and the atherogenic coefficient are important factors for determining atherogenic dyslipidemia and cardiovascular risk for predicting the lipid-lowering abilities of drugs (Ighodaro et al., 2017).

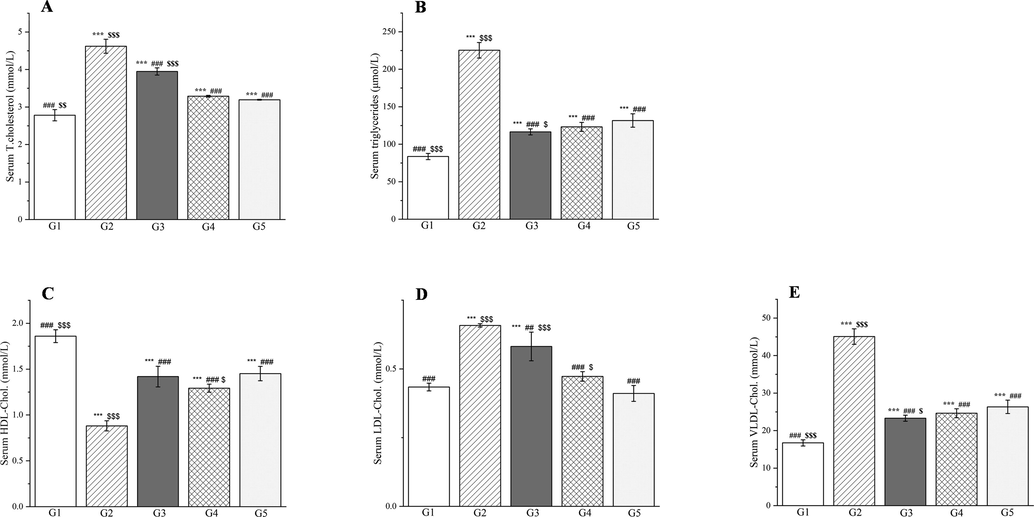

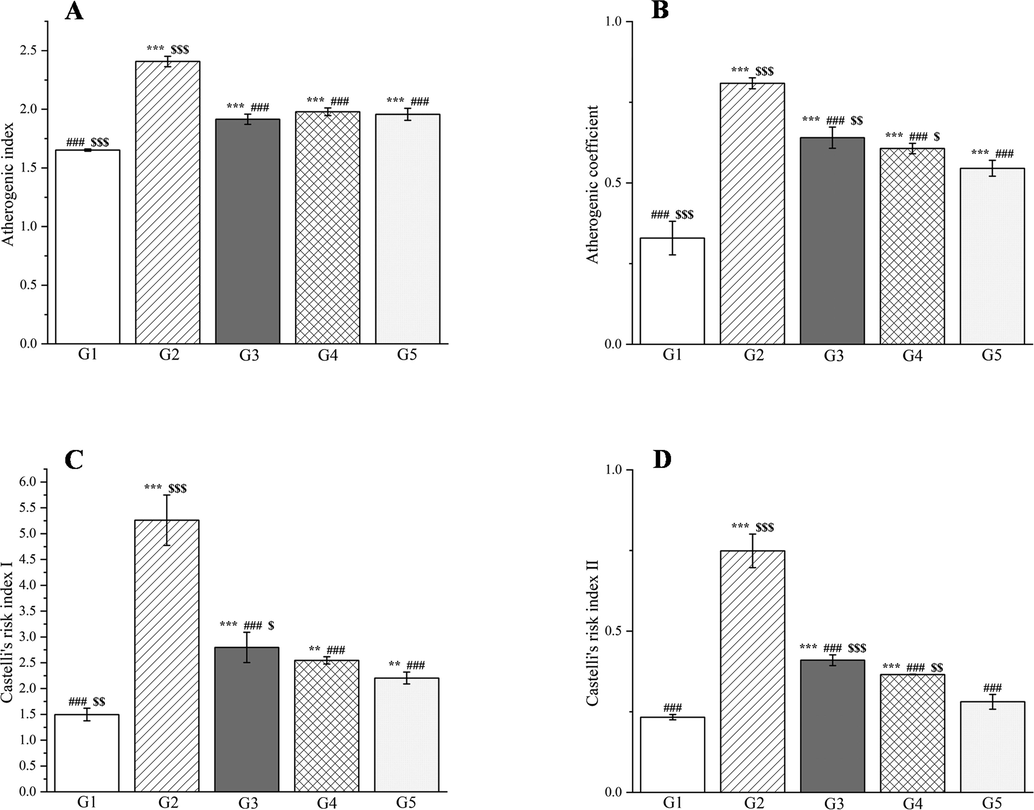

Compared with group 1, group 2 showed significantly elevated serum levels of LDL cholesterol, VLDL cholesterol, triglycerides, total cholesterol, Castelli’s risk indexes I and II, the atherogenic coefficient, and the atherogenic index of plasma (p < 0.001, Figs. 18 and 19). The HDL cholesterol levels decreased significantly in group 2 compared with group 1 (p < 0.001, Fig. 18C). Compared with group 2, groups 3–5 showed significant decreases in the serum levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, VLDL cholesterol, Castelli’s risk indexes I and II, the atherogenic index of plasma, and the atherogenic coefficient (p < 0.01 or p < 0.001, Figs. 18 and 19). The serum levels of HDL cholesterol increased significantly in groups 3–5 compared with group 2 (p < 0.001, Fig. 18C). CC reportedly reduces the levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL cholesterol in mice (He et al., 2016). Magnoflorine, the main component of PD and CC, can increase HDL cholesterol and lower LDL cholesterol, which may be related to its metal chelating ability (Hung et al., 2007).

The outcomes of treatment with a Plagiorhegma dubia methanol extract on the serum lipid profile in rats with induced diabetes: total cholesterol (A), triglycerides (B), HDL cholesterol (C), LDL cholesterol (D), and VLDL cholesterol (E). G1: Control group, G2: DM group, G3: DM + PD150 group, G4: DM + PD300 group, G5: DM + GLB group. PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; DM: Diabetes mellitus; GLB: Glibenclamide; HDL-C: High-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; VLDL-C: Very low density lipoprotein cholesterol. Significantly different from the control group at *** p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM group at ## p < 0.01 and ### p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM + GLB group at $ p < 0.05, $$ p < 0.01 and $$$ p < 0.001. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8).

The outcomes of treatment with a Plagiorhegma dubia methanol extract on the serum atherogenic index of plasma (A), atherogenic coefficient (B), and Castelli’s risk indexes I and II (C and D) in rats with induced diabetes. G1: Control group, G2: DM group, G3: DM + PD150 group, G4: DM + PD300 group, G5: DM + GLB group. PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; DM: Diabetes mellitus; GLB: Glibenclamide; AIP: Atherogenic index of plasma; AC: Atherogenic coefficient; CRI: Castelli’s risk indices. Significantly different from the control group at ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM group at ### p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM + GLB group at $ p < 0.05, $$ p < 0.01 and $$$ p < 0.001. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8).

Severe hyperglycemia increases ROS production, which exacerbates oxidative stress-induced damage to membrane lipids (Luc et al., 2019). Changes in membranes and impaired cell function can result in lipid peroxidation and production of toxic by-products such as malondialdehyde (Grotto et al., 2009). Endogenous antioxidants (glutathione, superoxide dismutase, glutathione reductase, vitamin C, and vitamin E) are effective for defense against damage caused by free radicals (Abd-Allah et al., 2016; Poli et al., 2022).

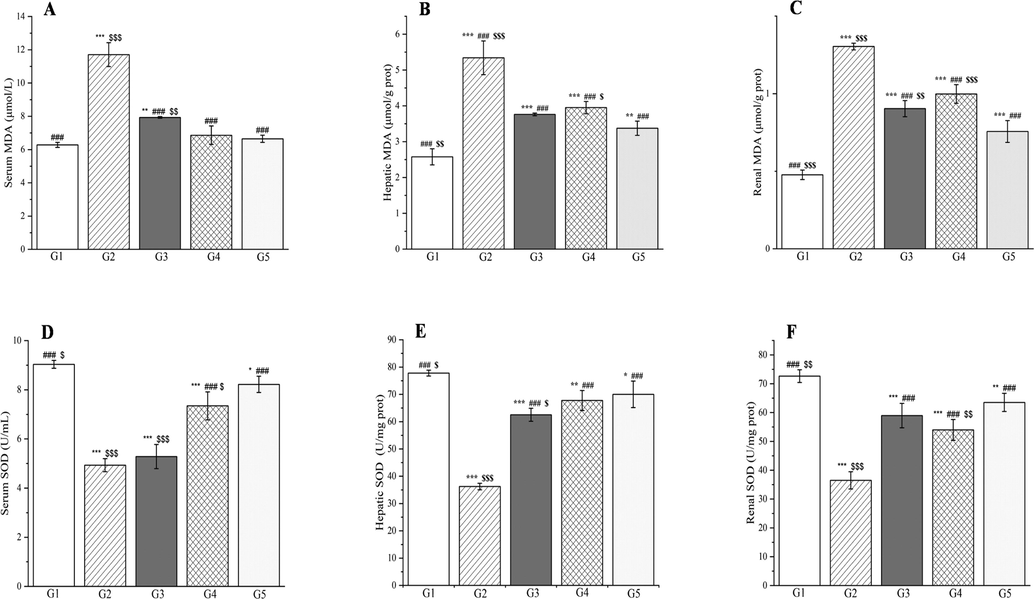

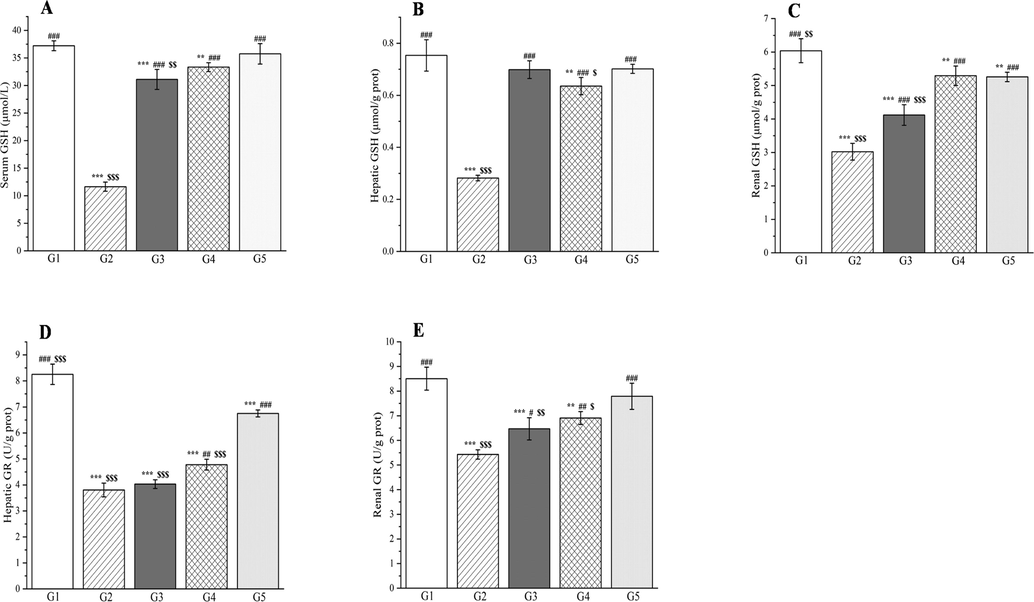

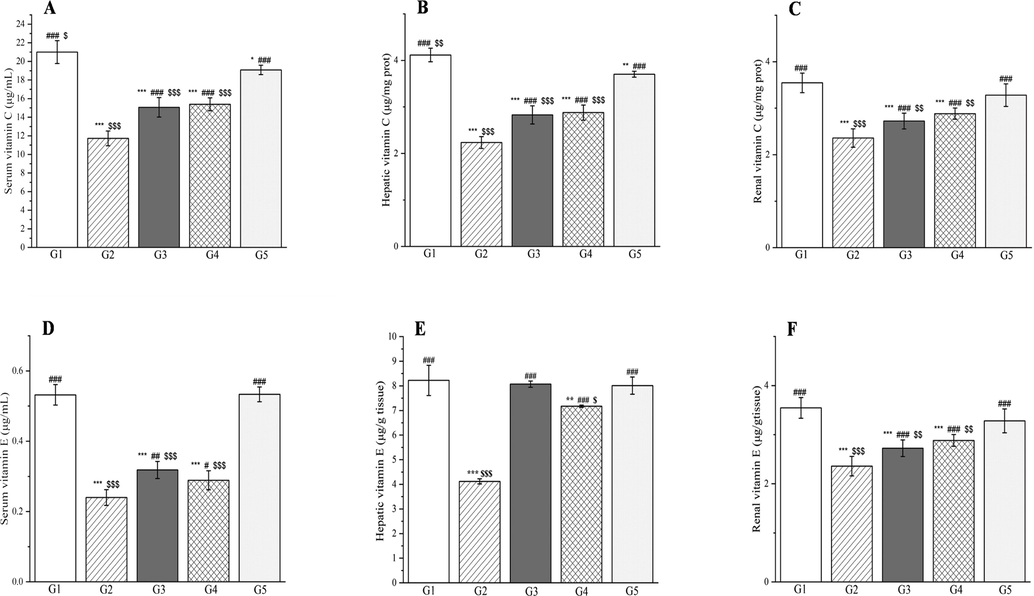

Compared with group 1, group 2 showed significant increases in the malondialdehyde concentrations in the liver, kidneys, and blood (p < 0.001, Fig. 20). By contrast, the glutathione, vitamin C, and vitamin E concentrations, and the superoxide dismutase and glutathione reductase activities showed significant decreases in the liver, kidneys, and blood for these groups (p < 0.001, Figs. 21–22). Compared with group 2, groups 3–5 showed significant decreases in the malondialdehyde concentrations in the liver, kidneys, and blood (p < 0.001, Fig. 20). By contrast, the glutathione, vitamin C, and vitamin E concentrations were significantly elevated in the liver, kidneys, and blood for these groups (p < 0.01 or p < 0.001, Figs. 21 and 22). The superoxide dismutase activities were significantly elevated in the liver and kidneys (p < 0.001, Fig. 20E and F) and the glutathione reductase activities significantly increased in the kidneys (p < 0.05, Fig. 21E).

The outcomes of treatment with a Plagiorhegma dubia methanol extract on serum, hepatic, and renal malondialdehyde and superoxide dismutase levels in rats with induced diabetes. G1: Control group, G2: DM group, G3: DM + PD150 group, G4: DM + PD300 group, G5: DM + GLB group. PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; DM: Diabetes mellitus; GLB: Glibenclamide; MDA: Malondialdehyde; SOD: Superoxide dismutase. Significantly different from the control group at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM group at ### p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM + GLB group at $ p < 0.05, $$ p < 0.01 and $$$ p < 0.001. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8).

The outcomes of treatment with a Plagiorhegma dubia methanol extract on serum, hepatic, and renal glutathione and glutathione reductase levels in rats with induced diabetes. G1: Control group, G2: DM group, G3: DM + PD150 group, G4: DM + PD300 group, G5: DM + GLB group. PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; DM: Diabetes mellitus; GLB: Glibenclamide; GSH: Glutathione; GR: Glutathione reductase. Significantly different from the control group at ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM group at # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01, and ### p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM + GLB group at $ p < 0.05, $$ p < 0.01 and $$$ p < 0.001. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8).

The outcomes of treatment with a Plagiorhegma dubia methanol extract on serum, hepatic, and renal vitamin C and vitamin E levels in rats with induced diabetes. G1: Control group, G2: DM group, G3: DM + PD150 group, G4: DM + PD300 group, G5: DM + GLB group. PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; DM: Diabetes mellitus; GLB: Glibenclamide. Significantly different from the control group at * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 and *** p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM group at # p < 0.05, ## p < 0.01 and ### p < 0.001. Significantly different from the DM + GLB group at $ p < 0.05, $$ p < 0.01 and $$$ p < 0.001. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8).

Compared with the rats in group 1, the rats with induced diabetes showed significant decreases for glutathione, superoxide dismutase, glutathione reductase, vitamin C, and vitamin E in the liver, kidneys, and blood. This may be caused by glycation or accumulation of free radicals and H2O2 produced by streptozotocin resulting in excessive consumption of vitamin C and vitamin E and enzymatic inactivation (Al-Numair et al., 2015; Rajasekaran et al., 2005). Two doses of PD administered orally ameliorated the oxidative stress and ultimately the metabolic disorder in diabetes. This could be attributed to the PD extract’s content of magnoflorine, which could effectively reduce the level of malondialdehyde and increase the level of superoxide dismutase in the rats with induced diabetes (Yadav et al., 2021). CC polysaccharides can reportedly increase superoxide dismutase and glutathione levels and decrease malondialdehyde levels (Jiang et al., 2015).

3.8 Histopathological analysis

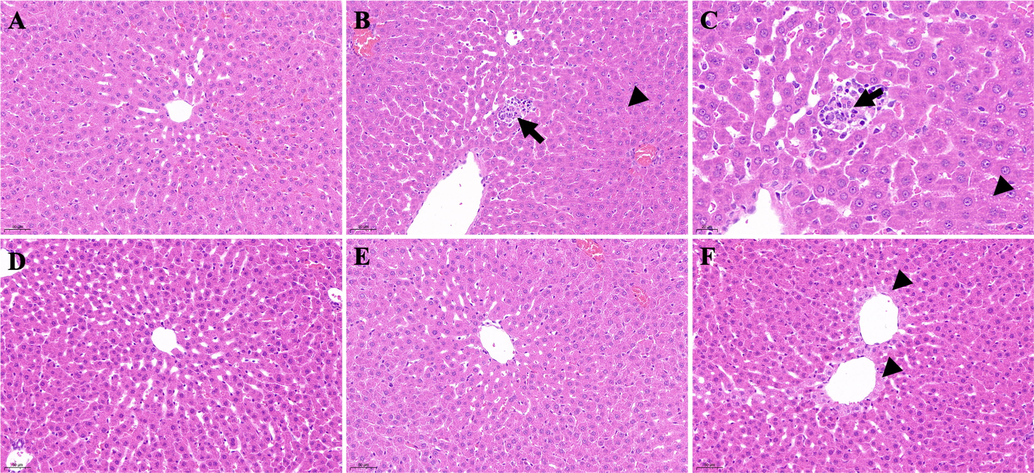

The livers of rats in group 1 had a clear histological structure, regular arrangement of liver cords, and no pathological changes (Fig. 23A). The livers of the group 2 rats showed increased vacuolar-like material in the liver cytoplasm around the central vein of the liver (Fig. 23B–C, black arrowheads), and inflammatory cell infiltrates were observed (Fig. 23B–C, black arrows). In the infiltrates, necrotic hepatocytes were replaced with macrophages. No obvious liver damage was observed in group 5 (Fig. 23D) or group 3 (Fig. 23E), and the liver tissue structure was clear. In group 4, the hepatocytes around the central vein of the liver were slightly enlarged, the cytoplasm was pale and granular, and the nuclei were blurred with only residual outlines or were invisible (Fig. 23F, black arrowheads).

Histological examination of liver sections in different groups. A: Control group (200 × magnification); B: DM group (200 × magnification); C: DM group (400 × magnification); D: DM + GLB group (200 × magnification); E: DM + PD150 group (200 × magnification); F: DM + PD300 group (200 × magnification). PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; DM: Diabetes mellitus; GLB: Glibenclamide.

The kidneys in group 1 had an intact and clear histological structure with no pathological changes (Fig. 24A). In group 2, the glomerular volume of the kidneys increased (Fig. 24B, black arrow), and the surrounding renal tubules became transparent (Fig. 24B, black arrowhead). Observation of the kidneys from group 2 under a high magnification microscope showed that cellular components in the glomerulus increased, the microvessels were congested with blood stasis (Fig. 24C, black arrow), the volume of the renal tubular epithelial cells increased, the cytoplasm was severely vacuolated and became transparent, and the nucleus was located in the center or deviated (Fig. 24C, black arrowhead). Group 5 was similar to group 3 and significantly improved compared with group 2, with occasional vacuolization of tubular epithelial cells (Fig. 24D and E, black arrowheads). Group 4 was not as good as group 3 and the renal tubular epithelial cells were more vacuolated (Fig. 24F, black arrowheads).

Histological examination of kidney sections in different groups. A: Control group (200 × magnification); B: DM group (200 × magnification); C: DM group (400 × magnification); D: DM + GLB group (200 × magnification); E: DM + PD150 group (200 × magnification); F: DM + PD300 group (200 × magnification). PD: Plagiorhegma dubia; DM: Diabetes mellitus; GLB: Glibenclamide.

The above discussion shows that, through the synergy of many alkaloids, PD improves lipid profile parameters and oxidative stress parameters, and increases the content of antioxidants in the body. Therefore, it could be used to treat diseases associated with oxidative imbalances, such as diabetes. This study supports the use of PD as a CC substitute.

In addition to its bioactivity, PD has many advantages over CC. Compared with CC, PD is widely distributed, readily available, and easy to cultivate. Both CC and PD are perennial plants and show little difference in their harvest periods. An important advantage of PD is that it is easier to source large quantities because both the rhizomes and fibrous roots are used in medicinal applications, whereas only the rhizomes of CC are used. Notably, many studies have reported that berberine, a major component of CC, is toxic to human cells but magnoflorine, a major component of PD, is not (Xu et al., 2020). The results from this study on the bioactivity of PD suggest that it is a promising economic crop for further research and development.

4 Conclusions

Among three solvent extracts of PD, the methanol extract had the highest total alkaloid content and best in vitro antioxidant activity. The phytochemical composition and in vivo hepatoprotective and antidiabetic activities of the methanol extract of PD are reported for the first time. UPLC–MS analysis of the methanol extract identified 41 secondary metabolites, including 38 alkaloids and three fatty acids. The main components were magnoflorine, berberrubine, and betaine. Addition of the methanol extract to extra virgin olive oil and cold-pressed sunflower oil increased the oxidative stability by significantly reducing the peroxide value. Cell viability and mouse oral acute toxicity tests showed that the methanol extract was relatively safe. Liver histology results and biochemical parameters indicated that the methanol extract had a hepatoprotective effect on liver injury induced by d-galactosamine. The methanol extract also showed antidiabetic activity, and it could significantly reduce serum glucose in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes, improve liver and kidney function, correct lipid metabolism disorders, and prevent oxidative stress. These findings support the traditional medical applications of PD and provide a scientific basis for its use as a substitute for CC.

Funding

This work was supported by Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Department (No.YDZJ202301ZYTS171; No.YDZJ202201ZYTS186; No.YDZJ202201ZYTS626).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hui Sun: Methodology, Data curation, Investigation. Meihua Chen: Methodology, Software, Investigation. Xu He: Methodology, Investigation. Yue Sun: Investigation. Jiaxin Feng: Investigation. Xin Guo: Investigation Li Li: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Junyi Zhu: Supervision. Guangqing Xia: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision. Hao Zang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gabrielle David, PhD, from Liwen Bianji (Edanz) (www.liwenbianji.cn/) for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript. We thank Professor Junlin Yu from Tonghua Normal University for the collection and identification of the Plagiorhegma dubia.

Declaration of Competing Interest