Translate this page into:

Exploring the effective components and potential mechanisms of Zukamu granules against acute upper respiratory tract infections by UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap-MS and network pharmacology analysis

⁎Corresponding authors at: Hunan Province Key Laboratory for Antibody-based Drug and Intelligent Delivery System, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Hunan University of Medicine, Huaihua 418000, China (W. Cai), National Institutes for Food and Drug Control, Beijing 100050, China; Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Institute for Drug Control, Urumqi 830054, China (J.B. Yang). yangjianbo@nifdc.org.cn (Jianbo Yang), 20120941161@bucm.edu.cn (Wei Cai)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Acute upper respiratory tract infections (AURTIs) are common diseases of respiratory system, which are caused by adenoviruses and generate the mix of severe clinical presentation. Zukamu granules (ZKMG), a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) prescription within Health Commission of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region possesses anti-influenza virus, antibacterial and anti-inflammatory effects that exerts therapeutic effects in treatment of AURTIs. However, the main effective chemical components and their corresponding action mechanisms have not been clarified. Therefore, ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole Exactive orbitrap tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap MS) and network pharmacology were used to detect and identify potentially effective components in ZKMG as well as uncover their pharmacological mechanisms against AURTIs. As a result, a total of 265 components from all 12 composed herbal medicines were characterized based on self-built database and fragmentation patterns, of which 38 compounds were unambiguously confirmed using reference standards. Then, the compound-target-pathway network was constructed that implied potential therapeutic mechanisms of ZKMG on AURTIs. Compounds noscapine, cryptopine, steviol-19-O-glucoside, N-methylnarcotine, allocryptopine, naringenin, boldine, methyl rosmarinate with related targets EGFR, PTGS2, IL2, MMP9, TNF, AKT1, PIK3CA, F3 were considered as the key components and targets. Besides, the results also indicated that PI3K-Akt, AGE-RAGE, PD-L1, HIF-1 signaling pathways contributed significantly to the therapeutic effects of ZKMG on AURTIs. Overall, ZKMG could have an effect on AURTIs based on multicomponent, multitarget, and multichannel mechanisms of action as well as this method provides guiding significance for the further development of TCM treatment.

Keywords

Zukamu granules

Acute upper respiratory tract infections

Effective components

Mechanisms

UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap-MS

Network pharmacology

1 Introduction

Acute upper respiratory tract infections (AURTIs) are one of the most common respiratory infectious diseases characterized by tonsillitis, pharyngitis, laryngitis, rhinitis, angina and the common cold, which are primarily caused by viruses rather than bacteria, fungi, and helminths (Huang et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2022). It was reported that the global incidence of AURTIs was 17.1 billion worldwide in 2017, which has brought about tremendous socioeconomic burden to public health (James et al., 2018). Although, the majority of AURTIs are slight and self-limited, they could result in undesirable clinical outcomes, as well as their complications might develop into serious diseases and threaten the security of the infected (Huang et al., 2019). The conventional treatment for AURTIs are preliminary medicines that relieve symptoms but do not treat disease infections, such as antipyretic analgesics and antihistamines (Pelzman and Tung, 2021). Antibiotics only for specific AURTIs and validated clinical indications are recommended, but most of antibiotics for common AURTIs are needless and ineffective (Wang et al., 2014; Harris et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2021). Additionally, the inappropriate utilization of antibiotics could lead to the emergence of resistant bacteria and increase treatment difficulties in clinical practice (Alrafiaah et al., 2017). Therefore, it is necessary that new therapeutic drugs are explored for AURTIs treatment.

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has the advantages of low toxicity and less adverse reactions, reversing multidrug resistance and reducing drug dosage, which has been widely considered to be effective method for various diseases because of its characteristics of multicomponents and multitargets (Chen et al., 2021; Kong et al., 2021). It is by using TCM that AURTIs have been cured for more than 1800 years in China and TCM plays a significant role in disease prevention (Zeng et al., 2022). Zukamu granules (ZKMG) as a famous classical formula was first recorded in the Uyghur medical book karibatin kader over 1500 years ago, which was known as the first choice for the treatment of colds in Uighur (Hou et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2021). ZKMG is composed of Kaempferia galanga (KG), Pericarpium papaveris (Papaver somniferum) (PP), Matricaria recutita (MR), Ziziphus jujuba (ZJ), Mentha canadensis (MC), Glycyrrhiza uralensis (GU), Althaea rosea (AL), Nymphaea tetragona (NT), Rheum palmatum (RP), Co rdia dicholoma (CRD) (Zeng et al., 2021). Modern pharmacological studies have revealed that ZKMG exhibits preferable anti-inflammatory anti-oxidant stress, regulation of apoptosis, and analgesic activities, as well as it is widely used for treating AURTIs and lung diseases in clinical studies (Li et al., 2022). Alkaloids in PP, flavonoids in ZJ, saponins in GU and quinones in RP have been primarily regarded as the main components of ZKMG prescription herbs. Besides, these components have been found to possess pharmacological activities against AURTIs (Fiore et al., 2008; Song et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015; Parsaei et al., 2016). However, as a complex TCM prescription, the therapeutic effect of ZKMG is not a function of a single herb as well as active compounds and action mechanism in the treatment of AURTIs remain still unclear because of the multichemical components, multi-pharmacological effects, and multi-action targets of ZKMG, so it is quite necessary to explore the potential pharmacodynamic substances and mechanism, which are related to its therapeutic function.

Apparently, the diversity of the chemical constituents of TCM possibly results in complex interactions between active ingredients and multiple targets in diseases. It is a great challenge that how to comprehensively explore potential effective constituents and mechanisms of action (Huang et al., 2021). Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole-Exactive orbitrap mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Q Exactive Orbitrap-MS) is powerful qualitative analysis technique, which has been developed for rapid characterization of unknown trace components in herbal medicines due to its high sensitivity, high resolution and high selectivity (Wang et al., 2021). Network pharmacology could systematically illustrate complex interactions among drugs, chemical constituents, targets, diseases and pathways, which has been considered to be a reliable approach to predict the pharmacological mechanism of drug treatments for diseases based on the development of systems biology and bioinformatics (Lu et al., 2021).

Therefore, it is a powerful method that UHPLC-MS combined with network pharmacology was used to explore the active ingredients and their potential mechanisms of TCM formula. In this study, a rapid and sensitive UHPLC-Q Exactive Orbitrap-MS method was established to investigate complex chemical compounds of ZKMG and their related mechanisms were explored by network pharmacology analysis. The study has certain guiding significance for clinical use and exploration mechanisms of action of ZKMG in treatment of AURTIs.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials and reagents

Zukamu granules (ZKMG) were provided by Xinjiang Uygur Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (220252, Xinjiang, China). The detailed information of reference standards is listed in Supplementary Table S1. Chromatographic grade methanol and acetonitrile were purchased from Merck (New Jersey, USA). Ultrapure water was prepared with a Milli-Q system (Millipore, Milford, MA, USA). LC-MS grade formic acid was obtained from Fisher Scientific (New Jersey, USA). All other reagents were of analytical grade.

2.2 Sample preparation

Zukamu granules (1 g) were extracted in 50 mL 70% (v/v) aqueous methanol with ultrasonic treatment for 1 h at 30 °C and 40 kHz. The extracting solution was filtered and evaporated (50 °C) using the rotary vacuum evaporator to obtain the residue of ZKMG. Then, 100 mg ZKMG extracts were approximately weighted and dissolved in 1 mL methanol. After centrifugation at 12000 rpm for 20 min, an aliquot (2 μL) of supernatant was injected into the UHPLC-MS system for analysis.

Individual stock solutions of standards (1 mg/mL) were respectively accurately weighted and prepared by dissolving in methanol. Then, the solutions of 38 standards were mixed and serially diluted at a concentration of 10 µg/mL stored at −20 °C before UHPLC-MS analysis.

2.3 UHPLC-MS conditions

Each sample was performed on an Ultimate 3000 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, California, USA) equipped with an Thermo Scientific Syncronis C18 (100 mm × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm) at a temperature of 45 °C. The mobile phases consisted of 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and acetonitrile (B), delivering at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min with the following solvent gradient: 0–2 min, 95–92% A; 2–5 min, 92–85% A; 5–10 min, 85–78% A; 10–12 min, 78–50% A; 12–20 min, 50–35% A; 20–25 min, 35–20% A; 25–26 min, 20–95% A; 26–30 min, 95% A.

The UHPLC system was coupled to a Q-Exactive Orbitrap MS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bremen, Germany), equipped with a heated electrospray ionization source (HESI) in the negative and positive modes for detection with the mass range of m/z 120–1200. For the spray voltage, the positive ion mode was 3.5 kV and the negative ion mode was 3.0 kV. The MS1 spectra were acquired with full MS mode with a resolution of 35,000, and the MS2 spectra resolution was 17,500 conducted in the data-dependent acquisition (DDA) mode. The sheath gas flow rate of 30 arbitrary units and auxiliary gas flow rate of 10 arbitrary units; and the temperatures of the capillary and auxiliary gas heaters were kept at 320 and 350 °C, respectively. The acquisition mode of the stepped normalized collision energy was set to 30, 40, and 60 %. The mass data were analyzed by Xcalibur 4.2 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific, California, USA).

2.4 The UHPLC-MS data analysis of ZKMG

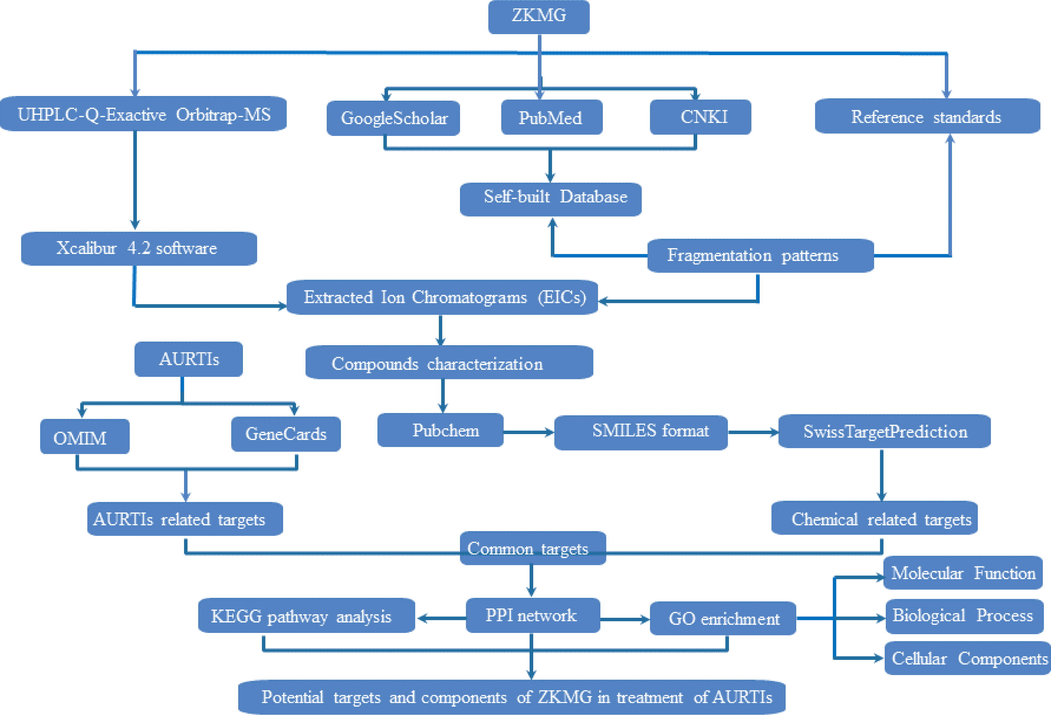

The approaches for identifying chemical composition of ZKMG were divided into three steps. (1) The self-built database based on searching compounds in domestic and international databases or related natural products research literatures, such as GoogleScholar, PubMed and CNKI, was established for consisted herbs of ZKMG including compounds names, molecular formulars, fragment ions and classifications. Besides, the fragmentation pathways of reference standards obtained were investigated to be beneficial for the characterization. (2) The Xcalibur 4.2 software was applied to acquire extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) of possible compounds, theoretical mass, experimental mass, retention times, mass error and detailed MS/MS fragment ions in both negative and positive modes. (3) The data pre-obtained from (1) was extracted in experimental row data in Xcalibur 4.2 software to identify chemical profiles by matching MS/MS fragments. Furthermore, the fragmentation patterns of reference standards were used to characterize unknown components, which possess similar skeleton structures or fragment ions based on the principle of structural similarity (Fig. 1).

The analytical strategy based on UHPLC-MS and network pharmacology for exploring potential pharmacodynamic substance and mechanisms of action of ZKMG on AURTIs.

2.5 Network pharmacology analysis

Firstly, all the identified compounds based on UHPLC-MS were transformed into canonical SMILES through the PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), most recently updated in March 2019. However, a number of compounds were not found in the PubChem, then their structures were imported in SwissTargetPrediction (http://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/, updated in 2019) to obtain SMILES, and the canonical SMILES information was uploaded into the SwissTargetPrediction database in “homo sapiens” species to predict all potential targets of compounds with probability ≥ 0.1 as the screening condition (Daina et al., 2019). Then the target genes obtained were verified by the UniProt protein database (https://www.uniprot.org/, updated in 2022) and converted into corresponding standard gene names (UniProt. 2018). Secondly, the keywords about “AURTIs” as well as relevant diseases “acute pharyngitis”, “acute tonsillitis”, “acute rhinitis”, “acute laryngitis” and “acute angina” were searched to obtain AURTIs related gene targets from Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database (OMIM http://omim.org/, updated in 2018) and GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/, version 5.0), and screen genes with “relevance score” of disease ≥ 30, and the repeated targets were deleted (Amberger et al., 2015; Stelzer et al., 2016). Thirdly, the chemical compounds targets and the diseases targets were imported in bioinformatics website (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/venn/, updated in 2022) to draw a Venn diagram and obtain their common gene targets. Then, the chemical components of ZKMG and its therapeutic targets in AURTIs were introduced into Cytoscape (https://cytoscape.org/, version 3.9.1) to construct the compound-target network (Shannon et al., 2003). Afterwards, the overlapping targets between the compounds targets and the AURTIs related targets were inputted into STRING database (http://string-db.org/, version 11.0) with a high confidence score ≥ 0.9 to construct the protein–protein interaction (PPI) network. The Cytoscape software (version 3.9.1) was used to visualize and analysis interactions in this network according to the network node topological parameter “degree”, it was used for evaluating the importance in the PPI network of a protein (Szklarczyk et al., 2018; Zhuang et al., 2020). Finally, the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID https://david.ncifcrf.gov/, version 6.8) was used for GO enrichment including molecular function (MF), biological process (BP), cellular components (CC), and KEGG pathway analysis (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/, updated in 2022), which provided systematic and comprehensive biological function annotation information. Meanwhile, top 20 enriched pathways of three GO terms (MF, BP, and CC) and KEGG were visualized in a bubble chart as well as three GO terms were drawn together with a bar chart and represented by a box line partition (p < 0.01) (Huang da et al., 2009; Li et al., 2022). Compound-target-pathway networks were constructed by using Cytoscape software (Fig. 1).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization of chemical components of ZKMG

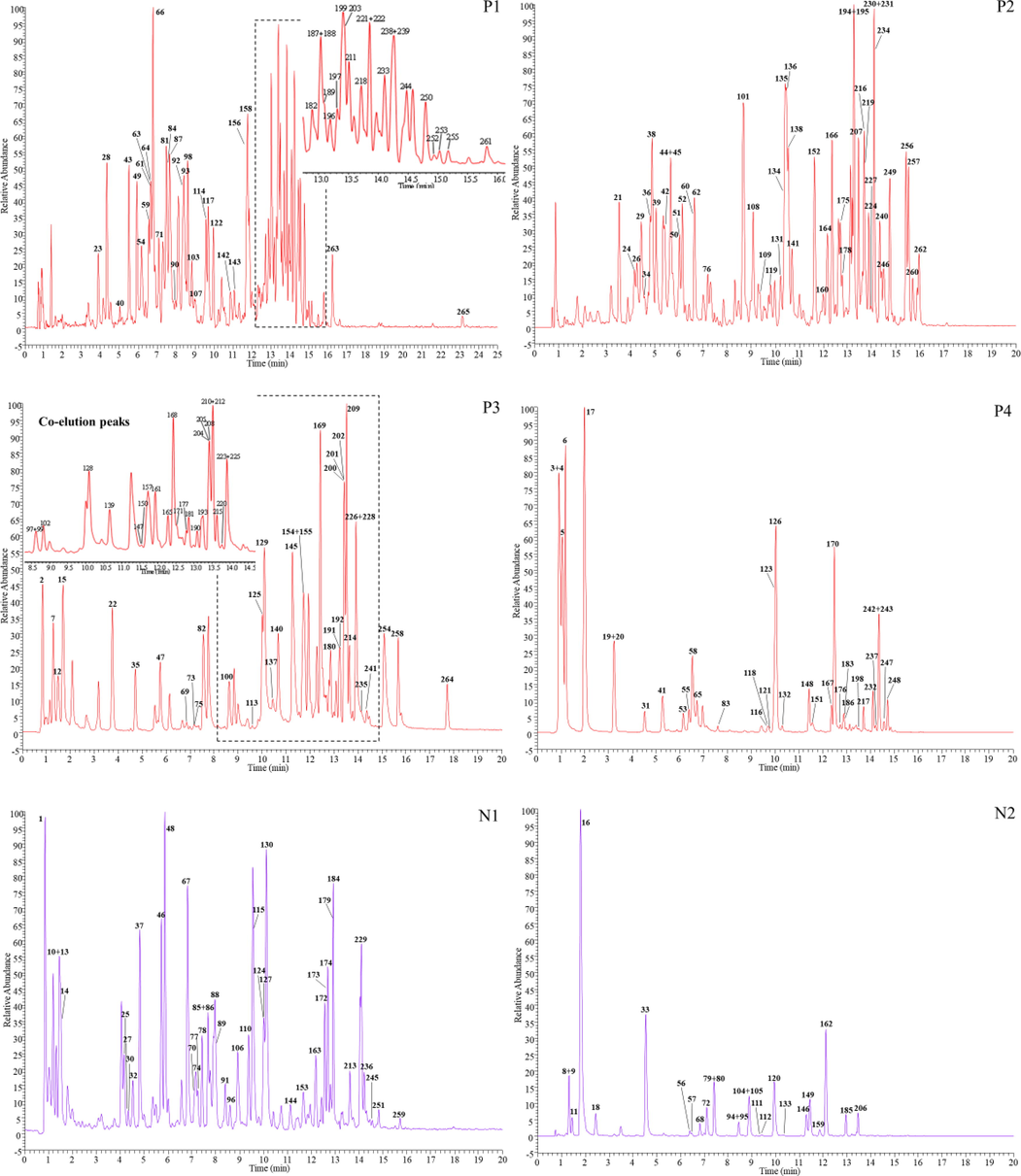

The chemical ingredients of ZKMG were detected and identified by UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap MS in both positive and negative modes to obtain as much information as possible. Totally, 265 compounds were identified from ZKMG based on accurate precursor and product ions and comparing their fragmentation patterns with standards or reported in the literatures, including 46 alkaloids, 92 flavonoids, 28 triterpenoid saponins, 27 phenolic acids, 24 phenylpropanoids, 21 quinones, 13 tannins, 4 amino acids, 4 nucleosides, 2 naphthols, 2 phenols, 2 terpenoids in Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2. The extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) of these compounds in both positive mode and negative ion modes were showed in Fig. 2. And 38 compounds in ZKMG were unambiguously identified by comparison with reference standards. * Compared with standard compounds.

peak

tR

Theoretical Mass m/z

Experimental Mass m/z

Error (ppm)

Formula

Identification

peak

tR

Theoretical Mass m/z

Experimental Mass m/z

Error (ppm)

Formula

Identification

1*

0.84

136.0618

136.0617

−0.68

C5H5N5

adenine

134

10.37

463.0882

463.0888

1.31

C21H20O12

quercetin-7-O-glucoside

2*

0.84

191.0561

191.0553

−4.19

C7H12O6

quinic acid

135

10.41

477.0675

477.0680

1.04

C21H18O13

quercetin-3-O-glucuronide

3

0.90

191.0197

191.0190

−3.80

C6H8O7

citric acid isomer

136*

10.47

463.0882

463.0888

1.32

C21H20O12

isoquercitrin

4*

0.92

133.0142

133.0132

−8.24

C4H6O5

malic acid

137

10.52

447.0933

447.0931

−0.45

C21H20O11

luteolin‐5‐O‐glucoside

5

1.05

191.0197

191.0190

−3.80

C6H8O7

isocitric acid

138

10.55

445.0776

445.0781

1.02

C21H18O11

rhein-8-O-β-D-glucoside

6*

1.18

191.0197

191.0190

−3.75

C6H8O7

citric acid

139*

10.66

447.0933

447.0937

0.91

C21H20O11

cynaroside

7

1.28

331.0671

331.0674

1.03

C13H16O10

1-O-galloylglucose

140

10.66

461.0725

461.0730

0.91

C21H18O12

kaempferol-3-O-β-D-glucuronide

8

1.31

268.1040

268.1038

−1.01

C10H13N5O4

adenosine

141*

10.69

623.1981

623.1988

1.04

C29H36O15

acteoside

9

1.32

132.1019

132.1019

−0.19

C6H13NO2

isoleucine

142

10.87

615.0992

615.1002

1.63

C28H24O16

quercetin-O-galloyl-glucopyranoside

10

1.43

284.0989

284.0987

−0.90

C10H13N5O5

guanosine

143

11.08

623.1618

623.1622

0.76

C28H32O16

isorhamnetin-3-O-nehesperidine

11

1.45

132.1019

132.1019

−0.27

C6H13NO2

leucine

144

11.12

370.1649

370.1646

−0.94

C21H23NO5

allocryptopine

12

1.48

331.0671

331.0674

1.03

C13H16O10

gallic acid-4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

145*

11.26

515.1195

515.1198

0.49

C25H24O12

isochlorogenic acid B

13*

1.49

330.0598

330.0592

−1.72

C10H12N5O6P

adenosine cyclophosphate

146

11.29

340.1543

340.1540

−1.10

C20H21NO4

papaverine

14

1.51

302.1387

302.1383

−1.24

C17H19NO4

morphine N-oxide

147

11.33

579.1719

579.1726

1.07

C27H32O14

naringin

15

1.69

331.0671

331.0674

1.03

C13H16O10

gallic acid-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

148*

11.42

593.1512

593.1517

0.91

C27H30O15

kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside

16

1.80

286.1438

286.1433

−1.61

C17H19NO3

morphine

149

11.44

414.1547

414.1541

−1.57

C22H23NO7

noscapine isomer 1

17*

1.98

169.0142

169.0134

−4.95

C7H6O5

gallic acid

150*

11.55

515.1195

515.1201

1.09

C25H24O12

1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid

18

2.44

166.0863

166.0862

−0.27

C9H11NO2

phenylalanine

151*

11.56

137.0244

137.0235

−7.06

C7H6O3

salicylic acid

19

3.23

179.0350

179.0553

−4.81

C9H8O4

caffeic acid isomer

152

11.63

623.1981

623.1992

1.73

C29H36O15

isoacteoside

20

3.32

197.0455

197.0448

−3.64

C9H10O5

danshensu

153

11.65

400.1391

400.1387

−1.02

C21H21NO7

narcotoline

21

3.51

329.0878

329.0882

1.29

C14H18O9

pseudolaroside B

154*

11.70

515.1195

515.1199

0.72

C25H24O12

isochlorogenic acid A

22

3.75

153.0193

153.0185

−5.76

C7H6O4

protocatechuic acid

155

11.73

491.0831

491.0836

0.97

C22H20O13

isorhamnetin-7-O-glucuronide

23

3.88

153.0557

153.0548

−5.93

C8H10O3

3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol

156

11.73

519.1872

519.1877

1.07

C26H32O11

pinoresinol 4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

24

4.15

451.1246

451.1249

0.78

C21H24O11

catechin‐5‐O‐glucoside

157

11.78

577.1563

577.1569

1.11

C27H30O14

apigenin-7-O-rutinoside

25

4.16

205.0972

205.0971

−0.07

C11H12N2O2

tryptophan

158

11.78

623.1618

623.1619

0.18

C28H32O16

isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside

26

4.25

483.0780

483.0784

0.83

C20H20O14

gallic acid-O-galloyl-glucoside

159

11.85

414.1547

414.1541

−1.42

C22H23NO7

noscapine isomer 2

27

4.33

448.1966

448.1965

−0.14

C23H29NO8

N-methylnorcoclaurine-7-O-glucoside

160

11.90

565.1563

565.1571

1.45

C26H30O14

hydroxyliquiritin apioside

28

4.33

515.1406

515.1411

0.82

C22H28O14

chlorogenic acid-hexoside

161

11.93

447.0933

447.0936

0.64

C21H20O11

luteolin-4′-O-glucoside

29

4.43

311.0409

311.0412

1.21

C13H12O9

caftaric acid

162

12.11

446.1809

446.1802

−1.71

C23H27NO8

narceine

30

4.47

272.1281

272.1277

−1.47

C16H17NO3

DL-demethylcoclaurine

163

12.17

282.1489

282.1485

−1.26

C18H19NO2

O-nornuciferine

31*

4.51

353.0878

353.0880

0.67

C16H18O9

neochlorogenic acid

164

12.17

433.1140

433.1143

0.55

C21H22O10

naringenin-7-O-glucoside

32

4.52

462.2122

462.2115

−1.70

C24H31NO8

N-methylcoclaurine-7-O-glucoside

165

12.28

431.0984

431.0985

0.19

C21H20O10

emodin-1-O-D-glucoside

33

4.54

300.1594

300.1589

−1.83

C18H21NO3

codeine

166

12.36

445.0776

445.0779

0.62

C21H18O11

apigenin-7-O-glucuronide

34

4.58

285.0616

285.0619

1.16

C12H14O8

uralenneoside isomer1

167*

12.37

609.1825

609.1832

1.21

C28H34O15

hesperidin

35

4.71

163.0401

163.0392

−5.63

C9H8O3

coumaric acid

168*

12.43

515.1195

515.1197

0.37

C25H24O12

isochlorogenic acid C

36

4.80

483.0780

483.0784

0.83

C20H20O14

gallic acid-O-galloyl-glucoside

169

12.43

607.1668

607.1674

0.95

C28H32O15

diosmin

37

4.81

448.1966

448.1962

−0.94

C23H29NO8

N-methylnorcoclaurine-4′-O-glucoside

170*

12.48

359.0772

359.0772

−0.09

C18H16O8

rosmarinic acid

38

4.89

285.0616

285.0619

1.05

C12H14O8

uralenneoside isomer 2

171

12.53

491.0831

491.0834

0.66

C22H20O13

isorhamnetin-3-O-glucuronide

39

5.04

451.1246

451.1249

0.72

C21H24O11

catechin‐7‐O‐glucoside

172

12.56

463.1235

463.1233

−0.49

C22H22O11

tectoridin

40

5.21

339.0722

339.0727

1.58

C15H16O9

esculin

173

12.66

639.1920

639.1920

0.09

C29H34O16

aurantio-obtusin-6-O-rutinoside

41

5.27

137.0244

137.0234

−7.28

C7H6O3

4-hydroxybenzoic acid

174

12.69

463.1235

463.1231

−0.82

C22H22O11

homoplantaginin

42

5.40

483.0780

483.0783

0.58

C20H20O14

gallic acid-O-galloyl-glucoside

175

12.71

463.1246

463.1250

0.90

C22H24O11

hesperetin-7-O-β-D-glucoside

43

5.50

515.1406

515.1412

1.05

C22H28O14

chlorogenic acid-hexoside

176

12.74

549.1614

549.1621

1.36

C26H30O13

licuraside

44

5.63

451.1246

451.1249

0.65

C21H24O11

catechin‐4′‐O‐glucoside

177

12.79

431.0984

431.0986

0.53

C21H20O10

aloe-emodin-3-(hydroxymethyl)-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

45

5.65

483.0780

483.0785

0.96

C20H20O14

gallic acid-O-galloyl-glucoside

178

12.79

591.1719

591.1727

1.25

C28H32O14

liquiritigenin-4′-O-(β-D-3-O-acetyl-apiofuranosyl-(1 → 2)-β-d-glucopyranoside

46

5.71

314.1751

314.1747

−1.15

C19H23NO3

lotusine

179

12.80

463.1235

463.1234

−0.10

C22H22O11

diosmetin-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

47

5.74

337.0929

337.0933

1.27

C16H18O8

5-p-coumaroylquinic acid

180

12.85

447.0933

447.0933

0.01

C21H20O11

luteolin-3′-O-glucoside

48

5.86

316.1543

316.1540

−1.00

C18H21NO4

norreticuline

181

12.86

475.0882

475.0885

0.57

C22H20O12

diosmetin-7-O-glucuronide

49

5.92

515.1406

515.1411

0.93

C22H28O14

chlorogenic acid-hexoside

182

12.89

459.1297

459.1302

1.13

C23H24O10

6′-acetylliquiritin

50

6.02

483.0780

483.0786

1.14

C20H20O14

gallic acid-O-galloyl-glucoside

183

12.90

417.1191

417.1195

0.90

C21H22O9

isoliquiritin

51

6.04

451.1246

451.2189

0.85

C21H24O11

catechin-3′-O-glucoside

184

12.92

493.1341

493.1340

−0.17

C23H24O12

aurantio-obtusin-6-O-glucoside

53*

6.14

353.0878

353.0881

0.75

C16H18O9

chlorogenic acid

185

12.96

431.1337

431.1334

−0.69

C22H22O9

ononin

52

6.14

325.0929

325.0931

0.77

C15H18O8

coumaric acid-O-glucoside

186

12.99

417.1191

417.1195

0.97

C21H22O9

neoisoliquiritin

54

6.16

635.0890

635.0895

0.78

C27H24O18

tri-O-galloyl-glucoside

187

13.03

433.0776

433.0779

0.50

C20H18O11

quercetin 3-O-arabinoside

55*

6.37

353.0878

353.0881

0.84

C16H18O9

cryptochlorogenic acid

188

13.04

695.1981

695.2002

−2.09

C35H36O15

licorice-glycoside B

56

6.40

286.1438

286.1436

−0.77

C17H19NO3

coclaurine

189

13.09

725.2087

725.2099

1.64

C36H38O16

licorice-glycoside A

57

6.48

300.1594

300.1592

−0.80

C18H21NO3

N-methylisococlaurine

190

13.09

459.0933

459.0938

1.21

C22H20O11

carboxyl-chrysophanol-O-glucose

58

6.52

291.0146

291.0148

0.55

C13H8O8

brervifolincaboxylic acid

191

13.21

283.0612

283.0607

−1.76

C16H12O5

glycitein

59

6.55

367.1035

367.1041

1.84

C17H20O9

4-feruloylquinic acid

192

13.21

447.0933

447.0935

0.44

C21H20O11

isorhamnetin-3-O-arabinoside

60

6.63

483.0780

483.0785

0.96

C20H20O14

gallic acid-O-galloyl-glucoside

193

13.25

593.1876

593.1881

0.90

C28H34O14

didymin

61

6.63

625.1410

625.1420

1.61

C27H30O17

quercetin-3-O-diglucoside

194

13.27

255.0663

255.0663

0.19

C15H12O4

liquiritigenin

62

6.67

325.0929

325.0933

1.14

C15H18O8

coumaric acid-O-glucoside

195

13.27

373.0929

373.0931

0.59

C19H18O8

methyl rosmarinate

63

6.67

635.0890

635.0898

1.34

C27H24O18

tri-O-galloyl-glucoside

196

13.29

473.1089

473.1090

0.16

C23H22O11

aloe-emodin-8-O-(6-O-acetyl)-glucoside

64

6.67

771.1989

771.2005

2.03

C33H40O21

quercetin-3-O-sophoroside-7-O-rhamnoside

197

13.31

999.4442

999.4453

1.00

C48H72O22

24-hydroxy-licoricesaponin A3

65*

6.71

179.0350

179.0343

−3.87

C9H8O4

caffeic acid

198

13.35

837.3914

837.3927

1.52

C42H62O17

yunganoside K2

66

6.76

635.0890

635.0897

1.06

C27H24O18

tri-O-galloyl-glucoside

199

13.40

489.1038

489.1059

4.25

C23H22O12

luteolin-7-O-6″-ocetylglucoside

67

6.81

328.1543

328.1541

−0.87

C19H21NO4

boldine

200

13.41

407.1348

407.1350

0.48

C20H24O9

torachrysone-8-O-glucoside

68

6.82

344.1856 [M]+

344.1853

−0.88

C20H26NO4+

N-methylreticuline

201*

13.42

285.0405

285.0406

0.45

C15H10O6

luteolin

69

6.85

579.1719

579.1729

1.59

C27H32O14

liquiritigenin-O-diglucuronide

202

13.42

431.0984

431.0985

0.26

C21H20O10

emodin-8-O-D-glucoside

70

7.09

386.1598

386.1597

−0.37

C21H23NO6

glaucamine

203*

13.44

301.0354

301.0356

0.78

C15H10O7

quercetin

71

7.09

711.2141

711.2150

1.10

C32H40O18

glucoliquirtin asioside

204

13.45

415.1035

415.1037

0.66

C21H20O9

chrysophanol-1-O-β-D-glucoside

72*

7.11

342.1699 [M]+

342.1694

−1.62

C20H24NO4+

magnoflorine

205

13.45

253.0506

253.0505

−0.48

C15H10O4

chrysophanol

73

7.15

515.1194

515.1196

0.25

C25H24O12

dicaffeylquinic acid

206

13.46

447.1286

447.1282

−0.77

C22H22O10

calycosin-7-O-β-D-glucoside

74

7.16

314.1750 [M]+

314.1748

−0.86

C19H24NO3+

isolotusine

207

13.46

983.4493

983.4506

1.25

C48H72O21

licoricesaponin A3

75

7.17

337.0928

337.0931

0.56

C16H18O8

3-p-coumaroylquinic acid

208*

13.48

283.0612

283.0611

−0.34

C16H12O5

physcion

76

7.19

325.0928

325.0932

0.95

C15H18O8

coumaric acid-O-glucoside

209

13.50

853.3863

853.3876

1.44

C42H62O18

22-hydroxy-licoricesaponin G2 isomer 1

77

7.24

328.1543

328.1541

−0.59

C19H21NO4

corytuberine

210

13.52

315.0510

315.0513

0.97

C16H12O7

isorhamnetin isomer

78

7.42

153.1273

153.1273

−0.80

C10H16O

camphor

211

13.52

895.3969

895.3982

1.44

C44H64O19

hydroxy acetoxyglycyrrhizin

79

7.42

330.1699

330.1696

−1.29

C19H23NO4

reticuline

212

13.53

415.1035

415.1037

0.59

C21H20O9

chrysophanol-8-O-glucoside

80

7.46

300.1594

300.1592

−0.70

C18H21NO3

N-methylcoclaurine

213

13.62

301.0707

301.0704

−0.88

C16H12O6

tectorigenin

81

7.48

635.0889

635.0896

0.97

C27H24O18

tri-O-galloyl-glucoside

214

13.64

315.0510

315.0515

1.35

C16H12O7

isorhamnetin isomer

82

7.55

337.0928

337.0932

0.92

C16H18O8

4-p-coumaroylquinic acid

215

13.64

853.3863

853.3878

1.74

C42H62O18

22-hydroxy-licoricesaponin G2 isomer 2

83

7.58

593.1511

593.1517

0.91

C27H30O15

vicenin Ⅱ

216

13.70

879.4020

879.4031

1.24

C44H64O18

acetoxy-glycyrrhizic acid

84

7.64

635.0889

635.0895

0.78

C27H24O18

tri-O-galloyl-glucoside

217

13.72

837.3914

837.3924

1.17

C42H62O17

licoricesaponin P2

85

7.67

314.1750

314.1746

−1.43

C19H23NO3

4′-methyl-N-methylcoclaurine

218

13.72

859.3758

859.3742

−1.82

C44H60O17

methyllicorice-saponin Q2 isomer 1

86

7.67

314.1750 [M]+

314.1746

−1.43

C19H24NO3+

magnocurarine

219

13.77

445.1140

445.1145

1.15

C22H22O10

physcion-8-O-β-D-glucoside

87

7.67

639.1567

639.1574

1.06

C28H32O17

isorhamnetin-3,7-O-diglucoside

220

13.78

329.0667

329.0671

1.32

C17H14O7

jaceosidin

88

7.98

328.1543

328.1541

−0.87

C19H21NO4

scoulerine

221*

13.86

271.0612

271.0614

0.75

C15H12O5

naringenin

89

8.02

298.1438

298.1436

−0.74

C18H19NO3

codeinone

222

13.86

835.3758

835.3762

0.46

C42H60O17

yunganoside M

90

8.08

635.0890

635.0898

1.25

C27H24O18

tri-O-galloyl-glucoside

223

13.89

283.0612

283.0613

0.51

C16H12O5

acacetin

91

8.39

356.1492

356.1489

−0.98

C20H21NO5

amurensinine N-oxide A

224

13.89

445.1140

445.1144

0.94

C22H22O10

physcion-1-O-β-D-glucoside

92

8.39

367.1035

367.1045

2.90

C17H20O9

5-feruloylquinic acid

225

13.91

269.0455

269.0457

0.64

C15H10O5

apigenin

93

8.43

635.0890

635.0886

−0.58

C27H24O18

tri-O-galloyl-glucoside

226

13.93

329.0667

329.0669

0.56

C17H14O7

iristectorigenin B

94

8.45

300.1594

300.1591

−1.20

C18H21NO3

6-demethyl-4′-methyl-N-methylcoclaurine

227

13.98

879.4020

879.4040

−1.72

C44H64O18

acetoxy-glycyrrhizic acid

95

8.45

344.1856

344.1852

−1.23

C20H25NO4

codamine

228*

13.99

285.0405

285.0407

0.87

C15H10O6

kaempferol

96

8.60

268.1332

268.1329

−1.03

C17H17NO2

caaverine

229

14.10

301.0707

301.0702

−1.68

C16H12O6

hispidulin

97

8.60

337.0929

337.0935

1.75

C16H18O8

1-p-coumaroylquinic acid

230

14.10

301.0718

301.0721

1.16

C16H14O6

hesperetin

98

8.62

625.1410

625.1417

1.12

C27H30O17

myricetin-3-O-rutinoside

231

14.11

819.3809

819.3823

1.78

C42H60O16

licoricesaponin E2

99*

8.63

163.0401

163.0392

−5.20

C9H8O3

4-coumaric acid

232

14.11

837.3914

837.3922

0.94

C42H62O17

licoricesaponin Q2

100

8.67

579.1719

579.1727

1.28

C27H32O14

liquiritigenin-O-diglucuronide

233

14.11

859.3758

859.3737

−2.39

C44H60O17

methyllicorice-saponin Q2 isomer 2

101

8.68

563.1406

563.1412

0.96

C26H28O14

schaftoside

234

14.11

967.4544

967.4556

1.19

C48H72O20

haoglycyrrhizin isomer 1

102

8.83

459.0933

459.0937

0.94

C22H20O11

carboxyl-chrysophanol-O-glucose

235*

14.14

315.0510

315.0514

1.16

C16H12O7

isorhamnetin

103

8.84

625.1410

625.1417

1.12

C27H30O17

quercetin-7-O-diglucoside

236

14.22

301.0707

301.0705

−0.65

C16H12O6

diosmetin

104

8.87

344.1856

344.1853

−0.97

C20H25NO4

laudanine

237

14.22

837.3914

837.3923

1.08

C42H62O17

uralsaponin N

105

8.89

312.1594

312.1589

−1.54

C19H21NO3

thebaine

238

14.24

863.4071

863.4081

1.17

C44H64O17

acetoxyglycyrrhaldehyde

106

8.91

326.1387

326.1382

−1.45

C19H19NO4

pacodine (7-O-demethylpapaverine)

239

14.27

449.1453

449.1456

0.69

C22H26O10

torachrysone-O-acetylglucoside

107

8.96

367.1035

367.1043

2.24

C17H20O9

3-feruloylquinic acid

240

14.35

255.0663

255.0661

−0.64

C15H12O4

isoliquiritigenin

108

9.08

463.0882

463.0887

0.97

C21H20O12

quercetin-5-O-glucoside

242*

14.36

821.3965

821.3973

0.94

C42H62O16

glycyrrhizic acid

109

9.36

433.1140

433.1143

0.55

C21H22O10

naringenin-4′-O-glucoside

241

14.36

329.0667

329.0668

0.47

C17H14O7

aurantio-obtusin

110

9.37

314.1751

314.1749

−0.45

C19H23NO3

armepavine

243

14.38

837.3914

837.3920

0.72

C42H62O17

hydroxyglycyrrhizin

111

9.40

417.1180

417.1178

−0.43

C21H20O9

daidzin

244

14.48

457.1140

457.1146

1.18

C23H22O10

chrysophanol-O-acetylglucoside

112

9.41

342.1700

342.1698

−0.45

C20H23NO4

tetrahydrocolumbamine

245

14.55

354.1336

354.1335

−0.17

C20H19NO5

pseudoprotopine

113

9.59

579.1719

579.1726

1.07

C27H32O14

liquiritigenin-O-diglucuronide

246

14.55

967.4544

967.4561

1.76

C48H72O20

haoglycyrrhizin isomer 2

114

9.59

621.1097

621.1104

1.01

C27H26O17

apigenin-7-O-diglucuronide

247

14.60

837.3914

837.3924

1.17

C42H62O17

hydroxyglycyrrhizin

115

9.63

326.1387

326.1384

−0.87

C19H19NO4

palaudine (3′-O-demethylpapaverine)

248

14.73

821.3965

821.3975

1.23

C42H62O16

licoricesaponin H2

116

9.67

549.1614

549.1619

1.03

C26H30O13

liquiritin apioside

249

14.76

807.4172

807.4185

1.51

C42H64O15

licoricesaponin B2

117

9.69

595.1668

595.1679

1.79

C27H32O15

eriocitrin

250

14.80

955.4908

955.4923

1.58

C48H76O19

yunganoside C1

118

9.72

417.1191

417.1195

0.83

C21H22O9

neoliquiritin

251

14.82

369.1333

369.1329

−1.07

C21H20O6

gancaonin N

119

9.81

433.1140

433.1144

0.97

C21H22O10

naringenin-5-O-glucoside

252

14.94

955.4908

955.4924

1.70

C48H76O19

yunganoside A1

120

9.94

428.1704

428.1699

−1.21

C23H25NO7

N-methylnarcotine

253

15.03

479.2650

479.2654

0.83

C26H40O8

steviol-19-O-glucoside

121

9.95

549.1614

549.1617

0.69

C26H30O13

isoliquiritin apioside

254

15.10

297.0405

297.0406

0.33

C16H10O6

6-methyl-rhein

122

9.97

517.0412

517.0438

4.86

C26H14O12

1,1,3,4,5,6,8,8′-octahydroxy-9H,9′H-2,2′-bixanthene-9,9′-dione

255

15.17

953.4752

953.4742

−0.96

C48H74O19

yunganoside D1

123

9.98

417.1191

417.1193

0.51

C21H22O9

liquiritin

256*

15.44

283.0248

283.0249

0.31

C15H8O6

rheic acid

124

10.00

370.1649

370.1643

−1.75

C21H23NO5

cryptopine

257

15.54

343.0823

343.0825

0.57

C18H16O7

eupatilin

125*

10.01

609.1461

609.1467

1.02

C27H30O16

rutin

258

15.67

283.0612

283.0613

0.40

C16H12O5

biochanin A

126

10.03

537.1038

537.1040

0.28

C27H22O12

lithospermic acid isomer

259

15.72

369.1333

369.1329

−1.07

C21H20O6

glicoricone

127

10.06

354.1336

354.1336

−0.05

C20H19NO5

protopine

260

15.72

807.4172

807.4184

1.43

C42H64O15

22-dehydrouralsaponin C

128*

10.09

300.9990

300.9991

0.40

C14H6O8

ellagic acid

261

15.83

355.1187

355.1193

1.63

C20H20O6

uralenin

129

10.10

431.0984

431.0985

0.33

C21H20O10

apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucoside

262

15.98

589.1351

589.1359

1.21

C31H26O12

1-methyl-8-hydroxy-9,10-anthraquinone-3-O-(6′-O-cinnamoyl)-glucoside

130

10.12

358.2013

358.2008

−1.24

C21H27NO4

laudanosine

263*

16.27

593.1301

593.1309

1.34

C30H26O13

procyanidin

131*

10.23

463.0882

463.0888

1.32

C21H20O12

hyperoside

264*

17.72

269.0455

269.0458

0.87

C15H10O5

emodin

132

10.29

593.1512

593.1520

1.43

C27H30O15

luteolin-7-O-rutinoside

265*

23.15

469.3323

469.3333

1.95

C30H46O4

18 β-glycyrrhetintic acid

133

10.34

344.1856

344.1855

−0.51

C20H25NO4

tetrahydropapaverine

The high resolution extracted ion chromatograms (EICs) of ZKMG in the positive (P) and negative ion mode (N). P1. m/z 153.0557, 271.0611, 301.0353, 339.0721, 355.1187, 367.1034, 433.0776, 449.1453, 457.1140, 459.1296, 469.3323, 473.1089, 479.2650, 489.1038, 515.1406, 517.0412, 519.1871, 593.1300, 595.1668, 615.0991, 621.1097, 623.1617, 625.1410, 635.0889, 639.1566, 695.1981, 711.2141, 725.2087, 771.1989, 835.3757, 859.3757, 863.4070, 895.3969, 953.4751, 955.4908, 999.4442; P2. m/z 255.0662, 283.0248, 285.0615, 301.0717, 311.0408, 325.0928, 329.0878, 343.0823, 373.0928, 433.1140, 445.0776, 445.1140, 451.1245, 463.0881, 463.1245, 477.0674, 483.0780, 563.1406, 565.1562, 589.1351, 591.1719, 623.1981, 807.4172, 819.3808, 879.4019, 967.4544, 983.4493; P3. m/z 153.0193, 163.0400, 191.0561, 253.0506, 269.0455, 283.0611, 285.0404, 297.0404, 300.9989, 315.0510, 329.0666, 331.0670, 337.0928, 407.1347, 415.1034, 431.0983, 447.0932, 459.0932, 461.0725, 475.0881, 491.0831, 515.1194, 577.1562, 579.1719, 593.1875, 607.1668, 609.1461, 853.3863; P4. m/z 133.0142, 137.0244, 169.0142, 179.0349, 191.0197, 197.0455, 291.0146, 353.0878, 359.0772, 417.1191, 537.1038, 549.1613, 593.1511, 609.1824, 821.3965, 837.3914; N1. m/z136.0617, 153.1273, 205.0971, 268.1332, 272.1281, 282.1488, 284.0989, 298.1437, 301.0706, 302.1386, 314.1750, 314.1761, 316.1543, 326.1386, 328.1543, 330.0597, 354.1335, 356.1492, 358.2012, 369.1332, 370.1648, 386.1598, 400.1390, 448.1965, 462.2122, 463.1234, 493.1340, 639.1919; N2. m/z 132.1019, 166.0862, 268.1040, 286.1437, 300.1594, 312.1594, 330.1699, 340.1543, 342.1699, 344.1856, 414.1547, 417.1180, 428.1703, 431.1336, 446.1809, 447.1285.

3.1.1 Identification of alkaloids

In this study, a total of 46 alkaloids mainly derived from PP were identified, which could be further divided into different alkaloids, including 2 tetrahydroprotoberberines, 5 aporphines, 20 benzyltetrahydroisoquinolines, 5 phthalideisoquinolines, 6 protopines, 5 morphinans, 3 benzylisoquinolines. The proposed fragmentation pathways of each-type representative alkaloids (peaks 88, 72, 56, 153, 144, 16, 146) were observed in Supplementary Figure S3.

3.1.1.1 Identification of tetrahydroprotoberberine alkaloids

Tetrahydroprotoberberine is a four-ring structure, which derived from two isoquinoline rings connected by sharing one nitrogen atom, and its C2, C3, C9, C10 contain oxygen groups (Yang et al., 2016). The peaks 88 and 112 were deemed to be tetrahydroprotoberberine alkaloids because of their MS/MS spectral patterns, which produced characteristic ions by Retro Diels-Alder (RDA) cleavage. They were tentatively identified as scoulerine and tetrahydrocolumbamine based on MS/MS fragmentation pattern of tetrahydroprotoberberine alkaloids. The fragmentation ions of scoulerine and tetrahydrocolumbamine were observed at m/z 178.086 [C10H12O2N]+ and 151.075 [C9H11O2]+ due to RDA fragmentation and cleavage of the B-ring, respectively. Another characteristic ion at m/z 163.060 was indicated by the loss of the methyl radical from the ion at m/z 178.086 (Jeong et al., 2012).

3.1.1.2 Identification of aporphine alkaloids

For aporphine alkaloids, the elimination of CH3NR group as well as lose CH3OH moiety and CO were the characteristic fragmentation patterns. Peak 72 showed precursor ion [M]+ at m/z 342.1699, which produced characteristic ions at m/z 297.111 [M-(CH3)2NH]+, 282.088 [M-(CH3)2NH-CH3]+, 265.085 [M-(CH3)2NH-CH3OH]+. Comparing with reference standards, peak 72 was accurately identified as magnoflorine. Similarly, peaks 67, 77 were pairs of isomers with [M + H]+ ion at m/z 328.1543 and exhibited three major diagnostic fragment ions at m/z 297.111 [M + H-CH3NH2]+, 265.085 [M + H-CH3NH2-CH3OH]+, 237.090 [M + H-CH3NH2-CH3OH-CO]+. Therefore, peaks 67, 77 were respectively determined as boldine and corytuberine according to their retention behavior on the chromatographic column (Conceição et al., 2020). Similarly, peaks 96 and 163 were considered as caaverine and O-nornuciferine.

3.1.1.3 Identification of benzyltetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids

For benzyltetrahydroisoquinoline alkaloids, they were easy to observe the elimination of NRH2, CH3OH groups and other characteristic ions at m/z 175.075 [C11H11O2]+, 161.059 [C10H9O2]+, 121.064 [C8H9O]+, 107.049 [C7H7O]+. Peak 30 with the parent ion [M + H]+ at m/z 272.12811, was easy to produce fragment ions at m/z 255.101 [M + H-NH3]+, 161.059 [M + H-NH3-C6H5O]+, and 107.049 [M + H-C9H11N2O]+. Consequently, it was tentatively determined to be DL-demethylcoclaurine based on the related literature (Oh et al., 2018). Peak 56 showed the [M + H]+ ion at m/z 286.1437, which yielded characteristic ions at m/z 269.117 [M + H-NH3]+, 237.090 [M + H-NH3-CH3OH]+, 175.075 [M + H-NH3-C6H6O]+, so peak 56 was tentatively named coclaurine (Menéndez-Perdomo et al., 2021). Similarly, peaks 27, 32, 37, 46, 57, 74, 80, 85, 86, 94, 110 were successfully identified as N-methylnorcoclaurine-7-O-glucoside, N-methylcoclaurine-7-O-glucoside, N-methylnorcoclaurine-4′-O-glucoside, lotusine, N-methylisococlaurine, isolotusine, N-methylcoclaurine, 4′-methyl-N-methylcoclaurine, magnocurarine, 6-demethyl-4′-methyl-N-methylcoclaurine, armepavine. Peak 130 had a retention time of 10.12 min and the [M]+ ion at m/z 358.2012. The fragmentation ions at m/z 327.158 [M + H-CH3NH2]+, 206.117 [C12H16NO2]+, 189.090 [C12H16NO2-NH3]+, and 151.075[C9H11O2]+ suggested that peak 130 was tentatively inferred to be laudanosine. On the basis of this method, peaks 48, 79, 68, 95, 104, 133 were deduced to be norreticuline, reticuline, N-methylreticuline, codamine, laudanine, tetrahydropapaverine.

3.1.1.4 Identification of phthalideisoquinoline alkaloids

For phthalideisoquinolines, the fragment ions were obtained by the isoquinone after bond cleavage with the phthalide ring as well as the elimination of H2O and OCH3 groups (Menéndez-Perdomo et al., 2021). Peak 153 showed a protonated adduct ion at m/z 400.1390 [M + H]+, which fragmented to [M + H-C10H10O4]+ at m/z 206.081, [M + H-H2O]+ at m/z 382.127 and [M + H-H2O-OCH3]+ at m/z 351.110. Therefore, peak 153 could be considered as narcotoline (Menéndez-Perdomo et al., 2021). Similarly, peaks 120, 149, 159, 162 were identified as N-methylnarcotine, noscapine isomer 1, noscapine isomer 2, narceine.

3.1.1.5 Identification of protopine alkaloids

For protopines, it produced characteristic ions by RDA fragmentation, and subsequent loss of water from the isoquinoline fragment (Jeong et al., 2012). Peak 144 showed the parent ion at m/z 370.1648 [M + H]+, and fragment ions at m/z 352.154 [M + H-H2O]+, 206.081 [C11H12NO3]+, and 188.070 [C11H12NO3-H2O]+. Then, peak 144 was characterized as allocryptopine based on the Orbitrap Traditional Chinese Medicine Library (OTCML). Likewise, peaks 70, 91, 124, 127, 245 were assigned as glaucamine, amurensinine N-oxide A, cryptopine, protopine, pseudoprotopine according to the OTCML database and relevant literature (Oh et al., 2018).

3.1.1.6 Identification of morphinan alkaloids

Peak 16 exhibited a protonated molecular ion at m/z 286.1437 [M + H]+, which fragmented to [M + H-CH2CHNHCH3-CO]+ at m/z 201.090 and [M + H-CH2CHNHCH3-H2O]+ at m/z 211.075. Therefore, this information led to the tentative conclusion that peak 16 was identified as morphine (Menéndez-Perdomo et al., 2021). Peak 33 with [M + H]+ ion at m/z 300.1594, was 14.015 Da (CH2) higher than the mass of the [M + H]+ ion of peak 16 and generated fragment ions at m/z 215.106 [M + H-CH2CHNHCH3-CO]+, 225.090 [M + H-CH2CHNHCH3-H2O]+. Peak 33 was characterized as codeine (Menéndez-Perdomo et al., 2021). Moreover, peaks 14, 89, 105 were respectively considered as morphine N-oxide, codeinone and thebaine (Oh et al., 2018; Menéndez-Perdomo et al., 2021).

3.1.1.7 Identification of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids

The precursor ion of peak 146 at m/z 340.1543 and the fragment ions at m/z 202.085 [C12H12O2N]+ and 324.122 [M + H-CH4]+ were formed by rearrangement of the C3′ and C4′ methoxy groups to a methylenedioxy bridge. Hence, peak 146 was identified as papaverine (Menéndez-Perdomo et al., 2021). Similarly, peaks 106, 115 were considered as pacodine and palaudine, respectively.

3.1.2 Identification of flavonoids

Flavonoids usually consist of the framework C6-C3-C6 that are formed when two phenyl rings (A and B) bind with C3, most of them undergo RDA cleavage (Luo et al., 2019). Totally, 92 flavonoids were characterized including 7 chalcones, 5 flavan-3-ols, 24 flavones, 25 flavonols, 21 flavonones, and 10 isoflavones in ZKMG. The proposed fragmentation pathways of each-type representative flavonoids (peaks 183, 24, 129, 235, 221, 213) were observed in Supplementary Figure S2.

3.1.2.1 Identification of chalcone flavonoids

The chalcones (1,3-diaryl-2-propen-1-ones) mainly derived from GU, which are open chain flavonoids. Peaks 183 and 186 showed the same [M−H]- ion at m/z 417.1191, which further yielded fragment ions at m/z 255.066 [M−H−C6H10O5]- by the elimination of glucosyl group, 135.007 [C7H3O3]- and 119.048 [C8H7O]- obtained due to RDA cleavage of the C-ring. Based on literature, peaks 183 and 186 were respectively identified as isoliquiritin and neoisoliquiritin (Xue et al., 2021). Peak 240 exhibited [M−H]- ion at m/z 255.0662, which generated characteristic ions at m/z 135.007 [C7H3O3]- and 91.017 [C7H3O3-CO2]-, so it was deduced as isoliquiritigenin based on OTCML database. Similarly, peaks 121, 176, 188, 189 were identified as lsoliquiritin apioside, licuraside, licorice-glycoside B, licorice-glycoside A according to the OTCML database and literature (Xue et al., 2021).

3.1.2.2 Identification of flavan-3-ol flavonoids

Peaks 24, 39, 44, 51 eluted at different time with the same precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 451.1245, and the MS2 spectrum showed fragment ions at m/z 289.072 [M−H−C6H10O5]- by a loss of glucose, 245.081 [M−H−C6H10O5−CO2]-, 137.023 [M−H−C6H10O5−C8H8O3]-. Thus, peaks 24, 39, 44, 51 were tentatively identified as catechin-5-O-glucoside, catechin-7-O-glucoside, catechin-4′-O-glucoside, catechin-3′-O-glucoside based on ClogP values. Peak 263 was unambiguously identified as procyanidin in accordance with the reference standard by comparing with retention time and MS/MS fragmentations.

3.1.2.3 Identification of flavone flavonoids

Peak 225 displayed the protonated molecule ion [M−H]- at m/z 269.0455, which subsequent fragment ions at m/z 227.034 [M−H−C2H2O]-, 225.055 [M−H−CO2]-, 201.055 [M−H−C3O2]-, and 151.002 [C7H3O4]- due to RDA cleavage, so peak 225 was assigned as apigenin based on OTCML database. Peak 129 exhibited molecular ion [M−H]- at m/z 431.0983 and the main fragment ion at m/z 269.045 [M−H−C6H10O5]-, which indicated peak 225 as aglycone of peak 129. Therefore, peak 129 was tentatively identified as apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucoside. Likewise, peaks 114, 157, 166 were tentatively characterized as apigenin-7-O-diglucuronide, apigenin 7-O-rutinoside, apigenin-7-O-glucuronide. Peak 201 showed [M−H]- ion at m/z 285.0404, and it could form the fragment ions m/z 241.049 [M−H−CO2]-, 217.049 [M−H−C3O2]-, 199.039 [M−H−C2H2O−CO2]-, 243.029 [M−H−C2H2O]-, 175.039 [M−H−C2H2O−C3O2]-, 133.028 [C8H5O2]- and 151.002 [C7H3O4]- due to RDA cleavage. Thus, peak 201 was accurately identified as luteolin by comparing with the reference standard. Peaks 137, 139, 161, 180 displayed the same precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 447.0932, which produced the fragment ion at m/z 285.040 [M−H−C6H10O5]-. Based on the standard and literature, peaks 137, 139, 161, 180 were respectively assigned as luteolin‐5‐O‐glucoside, cymaroside, luteolin-4′-O-glucoside, luteolin-3′-O-glucoside (Zhao et al., 2019). Similarly, peaks 83, 199, 132, 101, 261, 236, 181, 179, 169, 257, 229, 174, 220, 223 were tentatively characterized as vicenin II, luteolin-7-O-6″-ocetylglucoside, luteolin-7-O-rutinoside, schaftoside, uralenin, diosmetin, diosmetin-7-O-glucuronide, diosmetin-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, diosmin, eupatilin, hispidulin, homoplantaginin, jaceosidin, acacetin based on OTCML database.

3.1.2.4 Identification of flavonol flavonoids

Peak 235 exhibited [M−H]- ion at m/z 315.0510, yielded fragment ions at m/z 300.027 [M−H−CH3]-, 271.024 [M−H−CH3−CHO]- and 151.002 [C7H3O4]- by RDA cleavage. Therefore, peak 235 was identified as isorhamnetin according to the retention time of isorhamnetin reference standard and the comparison with MS2 fragment ions. The protonated molecular ion [M−H]- of peaks 155 and 171 was m/z 491.0831, which could form MS2 fragments at m/z 315.051 [M−H−C6H8O6]- by loss of glucuronide unit and subsequent loss of CH3 at m/z 300.027 [M−H−C6H8O6−CH3]-, so they were respectively assigned as isorhamnetin-7-O-glucuronide and isorhamnetin-3-O-glucuronide by comparing with their structures and chromatographic elution order (Nakamura et al., 2018). Correspondingly, peaks 87, 143, 158, 192, 210, 214 were respectively characterized as isorhamnetin-3,7-O-diglucoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-nehesperidine, isorhamnetin-3-O-rutinoside, isorhamnetin-3-O-arabinoside, isorhamnetin isomer, isorhamnetin isomer. Peak 203 displayed deprotonated molecular ion [M−H]- at m/z 301.0353, which produced characteristic ions at m/z 151.002 [C7H3O4]-, 178.997 [C8H3O5]- due to RDA cleavage. Based on reference standard and MS2 data, peak 203 was identified as quercetin. Likewise, peaks 61, 64, 98, 103, 108, 125, 131, 134, 135, 136, 140, 142, 148, 187, 228 were respectively identified as quercetin-3-O-diglucoside, quercetin-3-O-sophoroside-7-O-rhamnoside, myricetin-3-O-rutinoside, quercetin-7-O-diglucoside, quercetin-5-O-glucoside, rutin, hyperoside, quercetin-7-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-glucuronide, isoquercitrin, kaempferol-3-O-β-D-glucuronide, quercetin-O-galloyl-glucopyranoside, kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside, quercetin 3-O-arabinoside and kaempferol.

3.1.2.5 Identification of flavonone flavonoids

Peak 194 exhibited the precursor [M−H]- ion at m/z 255.0662 and yielded characteristic ions at m/z 135.007 [C7H3O3]-, 91.017 [C7H3O3-CO2]-, and 119.048 [C8H7O]- obtained due to RDA cleavage, suggesting that it was characterized as liquiritigenin by comparison with OTCML database. Moreover, peaks 69, 71, 100, 113, 116, 118, 122, 123, 160, 178, 182 were considered as liquiritigenin-O-diglucuronide, glucoliquirtin asioside, liquiritigenin-O-diglucuronide, liquiritigenin-O-diglucuronide, liquiritin apioside, neoliquiritin, 1,1,3,4,5,6,8,8′-Octahydroxy-9H,9′H-2,2′-bixanthene-9,9′-dione, liquiritin, hydroxyliquiritin apioside, liquiritigenin-4′-O-(β-D-3-O-acetyl-apiofuranosyl-(1 → 2)-β-D-glucopyranoside, 6′-acetylliquiritin in accordance with the reference literatures (Wang et al., 2020; Xue et al., 2021). Peak 221 showed protonated molecular ion at m/z 271.0611, which produced characteristic fragment ions at m/z 151.002 [C7H3O4]-, 119.049 [C8H7O]- due to RDA cleavage. Therefore, peak 221 was identified as naringenin by comparison with reference standard along with the retention and the characteristic product ions. Meanwhile, based on similar fragmentation patterns, peaks 109, 117, 119, 147, 164, 167, 175, 230 were identified as naringenin-4′-O-glucoside, eriocitrin, naringenin-5-O-glucoside, naringin, naringenin-7-O-glucoside, hesperidin, hesperetin-7-O-β-D-glucosidehesperetin.

3.1.2.6 Identification of isoflavone flavonoids

Peak 213 generated the [M + H]+ ion at m/z 301.0706, and the MS2 spectrum showed fragment ions at m/z 286.046 [M + H-CH3]+, 258.054 [M + H-CH3-CO]+, 168.005 [C7H4O5]+, which allowed its identification as tectorigenin by comparison with the OTCML database. Based on similar fragmentation patterns, peaks 111, 172, 185, 191, 206, 226, 251, 258, 259 were respectively deduced as daidzin, tectoridin, ononin, glycitein, calycosin-7-O-β-D-glucoside, iristectorigenin B, Gancaonin N, biochanin A and glicoricone according to OTCML database.

3.1.3 Identification of triterpenoid saponins

In this study, a total of 28 saponins primarily derived from GU were characterized in ZKMG. Saponins are composed of a sapogenin of 3α-hydroxy oleanolic acid and sugar residues, such as glucose (Glc), glucuronic acid (GluA), rhamnose (Rha), and xylose (Xyl), which is mainly regarded as structure of 11-oxo-12-ene, 12-ene skeleton (Cheng et al., 2021). The proposed fragmentation pathway of glycyrrhizic acid (peaks 242) was observed in Supplementary Figure S3.

Peak 242 showed precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 821.3965, and its primary characteristic ions appeared at m/z 351.057 [2GluA-H]-, 193.034 [GluA-H]- and 175.024 [GluA-H2O-H]-. Therefore, it was exactly identified as glycyrrhizic acid by comparing the retention time and fragmentation patterns with reference standard. Peaks 198, 217, 232, 237, 243, 247, which eluting at retention time of 13.35, 13.72, 14.11, 14.22, 14.38, 14.60 min respectively, exhibited the same molecular ion at m/z 837.39142 and the main fragment ions at m/z 351.057 [2GluA-H]-, 193.034 [GluA-H]- and 175.024 [GluA-H2O-H]-. Thus, they were respectively deduced as yunganoside K2, licoricesaponin P2, licoricesaponin Q2, uralsaponin N, hydroxyglycyrrhizin, hydroxyglycyrrhizin based on their MS2 fragmentation behavior, chromatographic retention time, and comparison with the similar known compounds and other reference evidence (Wang et al., 2020). Likewise, peaks 197, 207, 209, 211, 215, 216, 218, 222, 227, 231, 233, 238, 242, 248, 249, 260, 265 were respectively as 24-hydroxy-licoricesaponin A3, licoricesaponin A3, 22-hydroxy-licoricesaponin G2 isomer 1, hydroxy acetoxyglycyrrhizin, 22-hydroxy-licoricesaponin G2 isomer 2, acetoxy-glycyrrhizic acid, methyllicorice-saponin Q2 isomer 1, yunganoside M, acetoxy-glycyrrhizic acid, licoricesaponin E2, methyllicorice-saponin Q2 isomer 2, acetoxyglycyrrhaldehyde, glycyrrhizic acid, licoricesaponin H2, licoricesaponin B2, 22-dehydro uralsaponin C, 18 β-glycyrrhetintic acid according to their similar fragmentation patterns, standard, OTCML database. Peak 255 gave a precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 953.4751, which yielded characteristic fragment ions at m/z 497.115 [2GluA + Rha-H]-, 435.114 [2GluA + Rha-H2O-CO2-H]-, 339.093 [GluA + Rha + H2O-H]-, 321.082 [GluA + Rha-H]-. Compared with the data in literatures, peak 255 was assigned as yunganoside D1 (Ji et al., 2014). Similarly, peak 234, 246, 250, 252 were respectively characterized as haoglycyrrhizin isomer 1, haoglycyrrhizin isomer 2, yunganoside C1, yunganoside A1 based on their analogous fragmentation pathway and published data (Ji et al., 2014; Xue et al., 2021).

3.1.4 Identification of phenolic acids

In this research, a total of 27 phenolic acids were characterized. The proposed fragmentation pathway of ellagic acid (peaks 128) was observed in Supplementary Figure S3. Peak 2, 4, 6, 17, 65, 99, 128, 151 were exactly and respectively identified as quinic acid, malic acid, citric acid, gallic acid, caffeic acid, 4-coumaric acid, ellagic acid and salicylic acid with the reference standards. Peaks 3, 5, 6 indicated the same parent [M−H]- ion at m/z 191.0197, could give main product ions at m/z 173.008 [M−H−H2O]-, 129.018 [M−H−H2O−CO2]-, 111.007 [M−H−2H2O−CO2]-. Based on their chromatographic elution orders, further MS2 fragmentation patterns and reported literature (Al Kadhi et al., 2017). Peaks 7, 12, 15 exhibited the same precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 331.0670, which produced daughter ions at m/z 271.046 [M−H−C2H4O2]-, 211.024 [M−H−2C2H4O2]- and 169.013 [M−H−C6H10O5]- by loss of a glucose moiety. Based on similar fragmentation patterns and chromatographic elution orders, they were respectively identified as 1-O-galloylglucose, gallic acid-4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, gallic acid-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (Jin et al., 2007). Peak 19 showed the similar protonated molecular ion at m/z 179.0349 with peak 65, and yielded characteristic ion at m/z 135.044 [M−H−CO2]-, so it was presumed to be caffeic acid isomer. Peaks 20, 22, 35, 41 were tentatively identified as danshensu, protocatechuic acid, coumaric acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, respectively according to the OTCML database. Peaks 52, 62, 76 with the same protonated molecular ion [M−H]- at m/z 325.0928, were glucose moiety more than peak 35, which produced characteristic ions at m/z 163.039 [M−H−C6H10O5]-, 145.028 [M−H−C6H10O5−H2O]- and 119.049 [M−H−C6H10O5−CO2]-. Their fragment patterns were similar with peak 35, so they were tentatively assigned as coumaric acid-O-glucoside. Peak 126 exhibited [M−H]- ion at m/z 537.1038 and fragment behaviors are similar with lithospermic acid while retention time could not bring into correspondence with standard. Thus, it was tentatively assigned to lithospermic acid isomer. Peak 156 showed precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 519.1871 and yielded characteristic ions at m/z 357.134 [M−H−C6H10O5]-, 151.039 [C8H7O3]-, indicating that peak 156 was inferred as pinoresinol 4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside. Peak 193 generated the quasi-molecular ion [M−H]- at m/z 593.1875 and fragment ions at m/z 309.077 and 285.076. Thus, it was tentatively characterized as didymin. Peak 21 showed protonated molecular ion at m/z 329.0878, and produced fragment ions at m/z 167.034 [M−H−C6H10O5]-, 152.010 [M−H−C6H10O5−CH3]- and 123.044 [M−H−C6H10O5−CO2]-, suggesting that it was pseudolaroside B. Peaks 34 and 38 exhibited the same precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 285.0615, and it could form the fragment ions m/z 153.018 [M−H−C5H8O4]- by loss of an arabinose group and 109.028 [M−H−C5H8O4−CO2]-, suggesting that they were uralenneoside isomers.

3.1.5 Identification of phenylpropanoids

A total of 24 phenylpropanoids comprising of 4 coumaroylquinic acids, 3 feruloylquinic acids, 11 caffeylquinic acids and 6 other type acids were identified in ZKMG extract. The proposed fragmentation pathway of rosmarinic acid (peaks 170) was observed in Supplementary Figure S3. Peaks 31, 53, 55, 141, 145, 150, 154, 168, 170 were exactly identified as neochlorogenic acid, chlorogenic acid, cryptochlorogenic acid, acteoside, isochlorogenic acid B, 1,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, isochlorogenic acid A, isochlorogenic acid C, rosmarinic acid, respectively. Likewise, peak 73 gave precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 515.1194, with the fragment ions at m/z 353.088 [M−H−caffeoyl]-, 191.055 [quinic acid-H]-, 179.034 [caffeic acid-H]-, 135.044 [caffeic acid-H-CO2]-, which were consistent with the corresponding ions of dicaffeoylquinic acids. Therefore, peak 73 was inferred as dicaffeylquinic acid. Peaks 28, 43, 49 with the same parent ion [M−H]- at m/z 515.1406 were a glucose group (C6H10O5 162.052 Da) more than peaks 31, 53, 55 and possessed similar characteristic fragment ions at m/z 173.044 [quinic acid-H-H2O]-, 191.055 [quinic acid-H]-, 179.034 [caffeic acid-H]- and 135.044 [caffeic acid-H-CO2]-. Thus, they were tentatively identified as chlorogenic acid-hexosides. Peaks 47, 75, 82, 97 were found to elute at 5.74, 7.17, 7.55, 8.60 min, with [M−H]- ion at m/z 337.0928, and they could yield characteristic fragment ions at m/z 163.039 [coumaric acid-H]-, 119.048 [coumaric acid-H-CO2]-, 191.055 [quinic acid-H]-, 173.044 [quinic acid-H-H2O]-, suggesting that these compounds might be coumarylquinic acid. Therefore, Peaks 47, 75, 82, 97 were respectively identified as 5-p-coumaroylquinic acid, 3-p-coumaroylquinic acid, 4-p-coumaroylquinic acid, 1-p-coumaroylquinic acid according to their chromatographic elution behavior (Zhao et al., 2014). Peaks 59, 92, 107 were respectively eluted at 6.55, 8.39, 8.96 min with the parent ion [M−H]- at m/z 367.1034 and displayed characteristic secondary fragments at m/z 193.050 [ferulic acid-H]-, 149.059 [ferulic acid-H-CO2]-, 134.036 [ferulic acid-H-CO2-CH3]-, 173.044 [quinic acid-H-H2O]-, suggesting that these compounds might be feruloylquinic acid. Hence, they were tentatively identified as 4-feruloylquinic acid, 5-feruloylquinic acid, 3-feruloylquinic acid based on their chromatographic elution orders, further MS2 fragmentation patterns and reported literature (Zheleva-Dimitrova et al., 2017). Peak 29 with the precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 311.0408, gave characteristic product ions at m/z 149.008 [tartaric acid-H]-, 179.034 [caffeic acid-H]-, 135.044 [caffeic acid-H-CO2]-, suggesting that it was tentatively assigned to caftaric acid according to the OTCML database. Peak 40 was tentatively identified as esculin based on the OTCML database. Peak 195 with the parent ion [M−H]- at m/z 373.0928, was methyl (CH2 14.015 Da) more than peak 170, and produced characteristic ions at m/z 197.045 [M−H−C9H7O3]-, 179.034 [M−H−C9H9O4]-, 161.023 [M−H−C9H9O4−H2O]-, 135.044 [M−H−C9H9O4−CO2]-, which were the same fragment patterns as peak 170. Therefore, it was identified as methyl rosmarinate based on the OTCML database. Peaks 141, 152 both gave precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 623.1981, and yielded fragment ions at m/z 461.166 [M−H−C9H6O3]-, 179.034 [C9H7O4]-, 161.023 [C9H7O4-H2O]-, 135.043 [C9H7O4-CO2]-, suggesting that they were a group of isomers. Peak 141 was confirmed as acteoside by standard, so peak 152 was identified as isoacteoside based on their chromatographic retention behavior.

3.1.6 Identification of anthraquinones

A total of 21 quinones were identified in ZKMG, including 3 rheic acid-types, 3 physcion-types, 3 emodin-types, 6 chrysophanol-types, 3 aurantio-obtusin-types, 2 aloe-emodin-types and 1other compound, which are all derived from RP. The proposed fragmentation pathway of rhein (peak 256) was observed in Supplementary Figure S3.

Peaks 208, 256, 264 were unambiguously attributed to physcion, rheic acid, emodin by comparison with the authentic standards. Rhein as the main anthraquinone in ZKMG, was used to characterize the fragmentation pathways. It exhibited a parent ion [M−H]- at m/z 283.0248, and yielded characteristic product ions at m/z 255.030 [M−H−CO]-, 239.034 [M−H−CO2]-, 211.039 [M−H−CO2−CO]-, 183.044 [M−H−CO2−2CO]-. Based on these fragmentation patterns, peaks 138, 254 were identified as rhein-8-O-β-D-glucoside and 6-methyl-rhein. Physcion showed a precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 283.0611, which produced characteristic ions at m/z 268.037 [M−H−CH3]-, 240.042 [M−H−CH3−CO]-. Therefore, peaks 219, 224 were respectively identified as physcion-8-O-β-D-glucoside and physcion-1-O-β-D-glucoside according to the chromatographic elution orders, similar fragment patterns. Emodin indicated the parent ion [M−H]- at m/z 269.0455, and produced product ions at m/z 241.050 [M−H−CO]-, 225.054 [M−H−CO2]-. Based on these fragmentation patterns, peaks 165, 202 were identified as emodin-1-O-D-glucoside and emodin-8-O-D-glucoside. Likewise, peaks 102, 173, 177, 184, 190, 196, 204, 205, 212, 241, 244, 262 were assigned to carboxyl-chrysophanol-O-glucose, aurantio-obtusin-6-O-rutinoside, aloe-emodin-3-(hydroxymethyl)-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, aurantio-obtusin-6-O-glucoside, carboxyl-chrysophanol-O-glucose, aloe-emodin-8-O-(6-O-acetyl)-glucoside, chrysophanol-1-O-β-D-glucoside, chrysophanol, chrysophanol-8-O-glucoside, aurantio-obtusin, chrysophanol-O-acetylglucoside, 1-Methyl-8-hydroxy-9,10-anthraquinone-3-O-(6′-O-cinnamoyl)-glucoside, respectively, according to the similar fragment patterns.

3.1.7 Identification of tannins

Tannins might exist in ZKMG as they are important compounds found in the crude drug RP. Totally, 13 tannins were identified in ZKMG extract. The proposed fragmentation pathway of tri-O-galloyl-glucoside (peaks 54) was observed in Supplementary Figure S3. Peaks 54, 63, 66, 81, 84, 90, 93 gave the precursor [M−H]- ion at m/z 635.0889, and produced characteristic ions at m/z 483.077 [M−H−C7H4O4]-, 465.067 [M−H−C7H4O4−H2O]-, 313.057 [M−H−2C7H4O4−H2O]-, 169.013 [C7H5O5]-, and 125.023 [C7H5O5-CO2]-, thus they were assigned as tri-O-galloyl-glucoside isomers. According to this method, peaks 26, 36, 42, 45, 50, 60 were identified as gallic acid-O-galloyl-glucoside isomers.

3.1.8 Identification of other compounds

The other compounds including 4 amino acids, 2 naphthols, 2 phenols, 2 terpenoids were detected in ZKMG. The proposed fragmentation pathway of brervifolincaboxylic acid (peak 58) was observed in Supplementary Figure S3. Peaks 1 and 13 were confirmed as adenine and adenosine cyclophosphate, respectively, compared with known reference compounds. Peaks 9 and 11 both showed [M + H]+ at m/z 132.1019, and gave the same MS2 fragmentation ion at m/z 86.096 [M + H-CO-H2O]+, indicating that they were isomers. Consequently, peaks 9 and 11 were respectively characterized as isoleucine, leucine based on chromatographic elution orders. Peak 200 exhibited a precursor ion [M−H]- at m/z 407.1347, and showed the product ions at m/z 245.081[M-H-C6H10O5]- by loss of a glucosyl group, 230.058 [M−H−C6H10O5−CH3]- by elimination of a CH3 radical. Hence, it was identified as torachrysone-8-O-glucoside. Peak 239 with the parent ion [M−H]- at m/z 449.1453, was acetyl (C2H2O 42.010 Da) more than peak 200, and yielded the same fragment ions. Thus, it was tentatively characterized as torachrysone-O-acetylglucoside. Peak 58 showed [M−H]- ion at m/z 291.0146, and gave MS2 fragmentation ions at m/z 247.024 [M−H−CO2]-, 219.029 [M−H−CO2−CO]-, 191.034 [M−H−CO2−2CO]-, 173.023 [M−H−CO2−2CO−H2O]-, suggesting that it was identified as brervifolincaboxylic acid (Chen et al., 2022). Besides, peaks 8, 10, 18, 23, 25, 78, 253 were respectively characterized as adenosine, guanosine, phenylalanine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol, tryptophan, camphor, steviol-19-O-glucoside based on the OTCML database.

3.2 Network pharmacology analysis

3.2.1 Potential bioactive compounds and targets of ZKMG in the treatment of AURTIs

In this study, UHPLC-MS was used to detect a total of 265 chemical components of ZKMG. By searching the Swiss Target Prediction, 836 targets were obtained from identified compounds, and 1317 AURTIs related targets based on OMIM and GeneCards database (Supplementary Table S3). Finally, 120 overlapping targets were obtained by precisely matching the potential targets of the above two steps through the online tool Venny 2.1, suggested that ZKMG would play a role in treating AURTIs associated with these 120 common targets (Supplementary Figure S4).

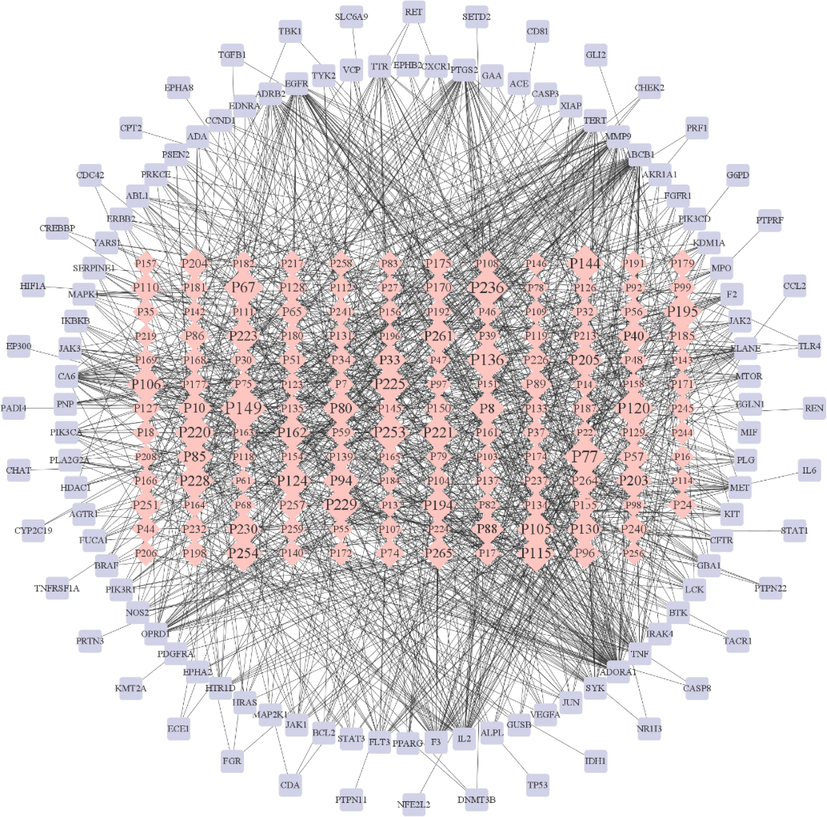

3.2.2 Compound‑target network analysis

The active ingredient potential target network of ZKMG in (Fig. 3). There are 271 nodes and 1117 edges in the network, among which the 155 pink nodes represent the main components of ZKMG, the 116 purple nodes represent the targets of AURTIs, and 1117 edges represent the interactions between the components and the targets of AURTIs. The size of the compounds in the network increases with the number of edges (degree of targets). The fact that the same active ingredient can act on multiple targets and the same target also corresponds to different chemical components were observed from the network, which fully reflect the multicomponent and multitarget characteristics of ZKMG in the treatment of AURTIs. The compounds were screened with a degree and betweenness centrality greater than the mean, such as 18 β-Glycyrrhetintic acid, noscapine, n-methylnarcotine, adenosine, methyl rosmarinate, thebaine, 6-methyl-rhein, which were possibly potential active ingredients of ZKMG in the treatment of AURTIs.

Compound-target network. pink rhombus nodes represent compounds, and purple rectangular nodes represent targets.

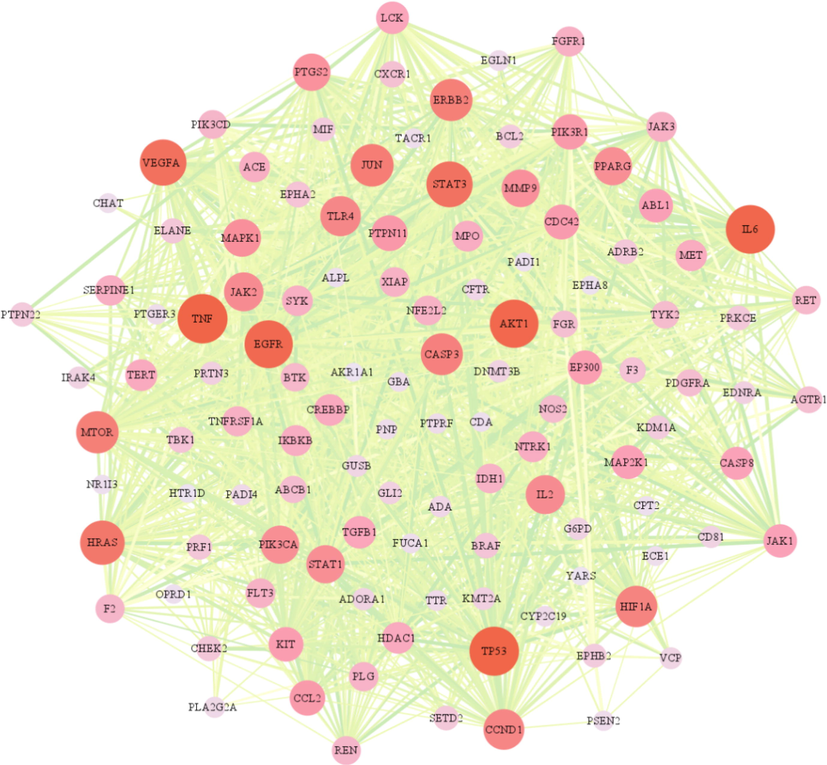

3.2.3 PPI network analysis

STRING analysis was used to compare 120 overlapping targets and produce a PPI network, as well as the visualization was realized by Cytoscape software (Fig. 4). There were 117 nodes and 1562 edges were observed with a combined score of greater than 0.4 (Supplementary Table S4). The size and color of the node reflected the importance of the degree. The larger the degree, the more important the node is in the network, suggesting that it may be a key target of ZKMG in the treatment of AURTIs. The top 10 nodes were selected as the major genes, including TNF, TP53, IL6, AKT1, EGFR, VEGFA, STAT3, HRAS, JUN, ERBB2, which were likely to be the critical genes in the development of AURTIs.

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network.

3.2.4 GO analysis and KEGG pathway analysis

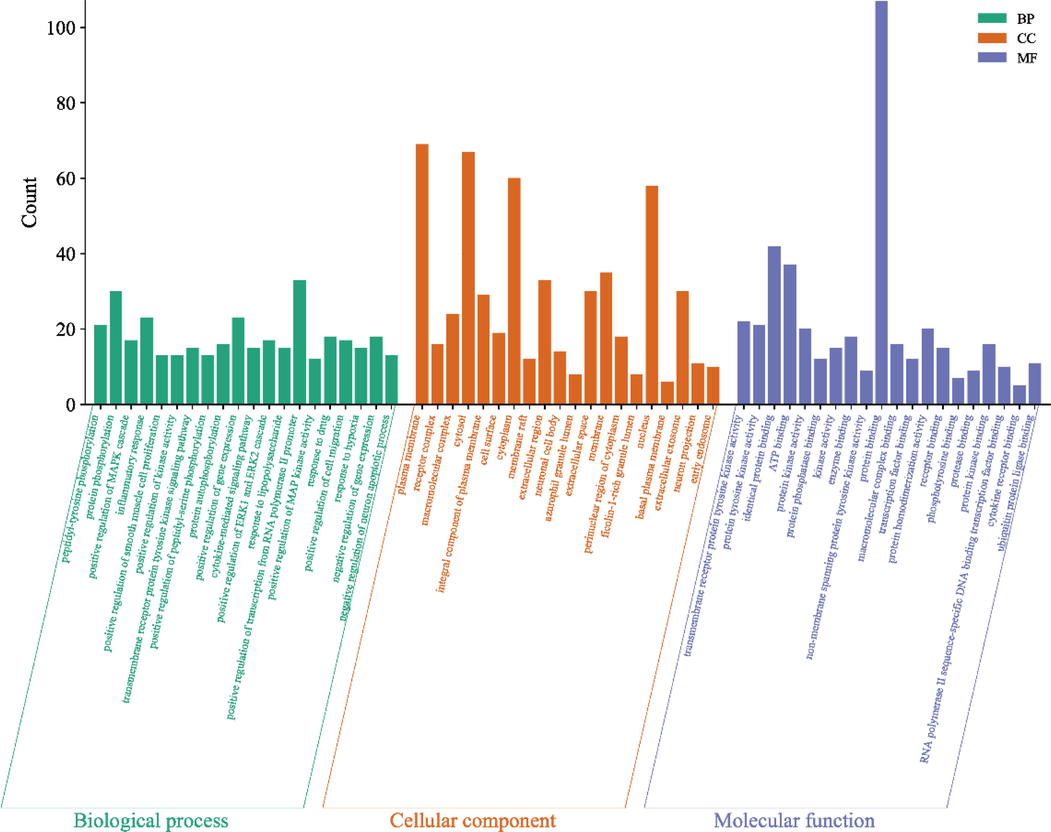

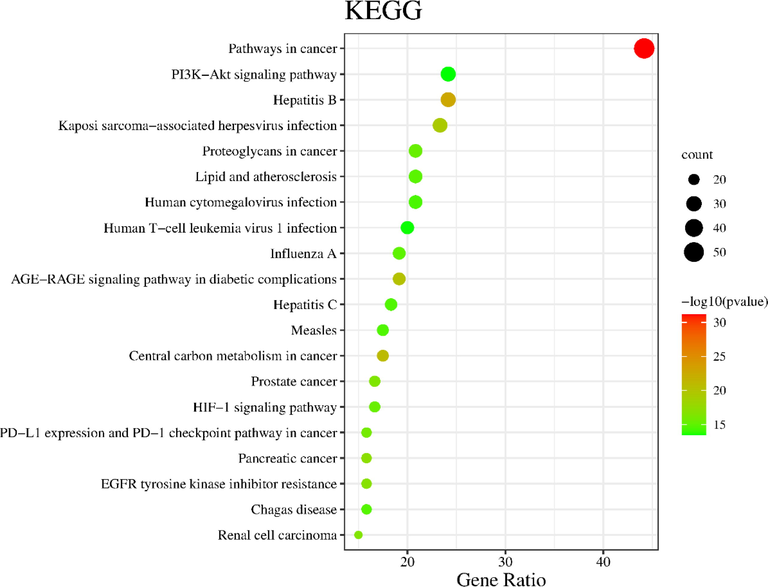

GO function and KEGG pathway analysis of the 120 candidate target genes were posted on the DAVID database to explore the molecular mechanism of ZKMG in treating AURTIs. GO evaluations were illustrated by using biological process (BP), cell component (CC), and molecular function (MF) terms. The results of GO analysis showed that potential target genes were enriched, which involved with 638 pathways, including 505 BPs, 52 CCs and 81 MFs (P<0.05). The top 20 pathways of BP, CC, MF with the highest number of genes involved were shown in the Fig. 5. In BP, the targets mainly involved peptidyl-tyrosine phosphorylation, protein phosphorylation, inflammatory response. In CC, the targets mainly involved plasma membrane, receptor complex, macromolecular complex. In MF, the targets mainly involved transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase activity, protein tyrosine kinase activity, identical protein binding, protein kinase activity (Supplementary Table S5). KEGG pathway annotation indicated that potential target genes were involved in 148 pathways (P<0.05). The top 20 KEGG pathways with the highest number of genes were shown in the Fig. 6, including PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, AGE-RAGE signaling pathway in diabetic complications, PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint pathway in cancer, HIF-1 signaling pathway (Supplementary Table S6).

GO term histograms.

Bubble map of KEGG pathway analysis.

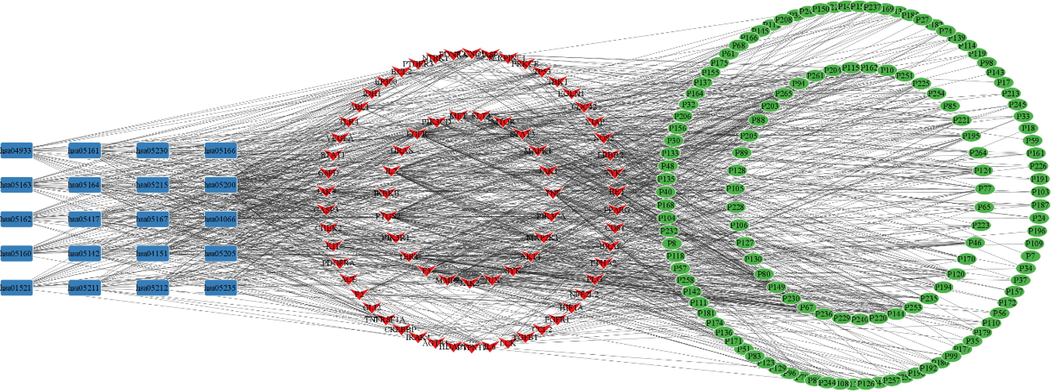

3.2.5 Compound‑target‑pathway network analysis