Translate this page into:

Nanofluids and their application in carbon fibre reinforced plastics: A review of properties, preparation, and usage

⁎Corresponding author. kelvin.yoroo@gmail.com (Kelvin O. Yoro)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Renewed call for the replacement of conventional materials with carbon fibre reinforced plastics (CFRPs) in many high-performance applications is responsible for the current wave of research on minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) strategy in machining. Due to their competitive advantages over conventional materials, polymer matrix composites (PMCs) are now attracting the attention, of researchers, especially in the field of machining. Although most manufacturing methods require less machining, precision machining like milling and drilling call for more research inputs. For this purpose, this review article assesses various aspects of nanofluid preparation and its application in CFRPs. Recent scientific reports on nanofluids with a focus on properties, preparation, and application (including respective methodologies) were analyzed, to contribute to the growing database for future research in this field. This review article shows that cutting temperature and cutting force remain the key determinants of surface finish, while tool wear constitutes a major parameter that machining scientists would like to keep under full control by the use of appropriate cutting fluids. Uncertainties around the quality of nanofluids which is scarcely discussed in the literature is raised in this review, while advocating for more research to unravel it. Furthermore, this review article sheds more light on the machining operations of carbon fiber-reinforced plastics using nanoparticle-laden fluids for a safe and sustainable machining experience. Finally, this review assesses the possibility of achieving excellent CFRP processing using a sustainable approach to fill existing gaps identified in literature like wasted cutting liquids, environmental pollution, and exposure of operators to health hazards.

Keywords

Nanofluids

Machining

Manufacturing

Minimum quantity lubrication

Carbon fibre reinforced polymer

1 Introduction

Researchers have channeled a tremendous amount of energy toward the creation of a safe, sustainable, and effective manufacturing environment; especially for cutting, corrosion control, and machining (Eterigho-Ikelegbe et al., 2021; Medupin et al., 2023). Cutting fluids are important materials that could be used to achieve optimal surface finishes during machining operations. Machinists simply take advantage of an abundant supply of coolants to achieve speedy cooling and lubricating effect as well as a quick removal of chips. However, the need for a high volume of cutting fluids and additional peripheral equipment becomes a huge worry (Madanchi et al., 2019).

Significant effort has been made by scientists in recent times to explore nanofluids and their prospective lubricating potential. Singh et al. (2017) defined lubrication as the process by which wear of either or both surfaces or parts in relative movement to each other is reduced by the abrupt and deliberate introduction of lubricants between the surfaces to remove the pressure generated during the opposing movement. The main objectives of the lubrication were to reduce wear and tear, as well as heat generated due to friction, thereby protecting surfaces against corrosion. Bio-lubricants have been identified as an excellent substitute for synthetic lubricants in the machining of heat-resistive superalloys because they offer the most sustainable mode of machining for both micro and nano-fluids (Sen et al., 2020; Venkatesh et al., 2018). However, of all the lubrication approaches, nano-lubrication has emerged as one of the most sustainable, renewable, and energy-efficient lubrication strategies in machining processes (Zadafiya et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2017; Pal et al., 2021). Different variables, including production time, cost, and energy consumption, are minimized by the use of appropriate cutting fluids (Agapiou, 2018).

While machining quality is said to depend on the speed of cutting, feed rate, properties of materials being cut, and the choice of appropriate cutting fluids also affects the quality of finished surfaces (Rapeti et al., 2016). According to Venkatesh et al (Venkatesh et al., 2018) cutting fluids are effective coolants meant to convey heat away from the tool/workpiece interface during machining. Common coolants (water, mineral oil, synthetic oil, vegetable oil, etc) are used as base oils to perform the same functions. However, they are ineffective in their raw state because of chemical imbalances, and could facilitate the corrosion process (Pimenov et a., 2021). Therefore, nanoparticles-laden base oils are currently investigated to address issues around quick heat removal from the interface between tool and workpiece by leveraging the large surface areas of nanoparticles (NPs).

Nano-cutting fluids are principally fluids containing lower volume concentrations of NPs which are generally used during cutting operations. Pimenov et al (Pimenov et a., 2021) presented findings on the improvements in machining activities achievable with NPs being homogeneously dispersed in base fluids. Given the non-biodegradable nature of most of the conventional cutting fluids currently in use, as well as health-related issues like skin and lung diseases, MQL has emerged as a more environment-friendly option (Padmini et al., 2019). Lubrication failure at higher metal removal and environmental pollution are common problems associated with most conventional coolants. Flood cooling is common with this type of machining. Hence, the machining environment is usually flooded with hazardous chemicals (Ma et al., 2022). This does not align with the SDGs guidelines on responsible production and consumption. In addition, the vibration and noise that often result from certain machinery underscore the need to find suitable alternatives that could help address these challenges. To proffer a solution to these problems, Jia et al. (2020) suggested the use of viscoelastic damping materials for vibratory noise reduction owing to their low densities, high strengths, and high elastic moduli. Furthermore, Feito et al.(2019) identified local delamination as the most challenging impairment associated with machining CFRPs. Zadafiya et al. (2021) reported an approximately 58% reduction in tool wear rate by using a nanofluid of 1% volume concentration in contrast to traditional and dry machining. Other indicators that improve because of the increase in the concentration of NPs include fluid viscosity, thermal conductivity, and density. The challenges encountered with conventional materials in all applications have triggered intense research for the development of both natural and synthetic fiber-reinforced polymer (nano)composite materials to address the aforementioned agelong issues(Abdalla et al., 2010; Arumugam and Ju, 2021; Benzait and Trabzon, 2018; Feldman, 2017; Guo et al., 2020; Guo and Zhang, 2021; Jawahar et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Medupin et al., 2017, 2019; Mensah et al., 2015; Pozegic et al., 2016; Sadare et al., 2022; Salah et al., 2019; Sathyanarayana, 2013; Scholz et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2021; Veeman et al., 2021; Zaaba and Ismail, 2019; Zwawi, 2021; Bokobza, 2019; Kumar et al., 2021; Oleiwi et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2014). Some of these polymer nanocomposites are applied in areas which would require resizing to the design specifications, hence the need for machining with other conventional materials (Mohammed et al., 2015; Jose and Athikalam, 2020).

Furthermore, maintaining the chemical stability of nano-cutting fluids and ensuring its adherence to the sustainable development goals (SDGs) are the major challenge that must be overcome by researchers in the field (Goindi and Sarkar, 2017; Yoro et al., 2021). Zadafiya et al. (2021) have investigated an effective lubrication system that meets sustainability requirements without trading off manufacturing efficiency and product quality. In another study, Wickramasinghe et al. (2021) opined that most vegetable oils have stability issues resulting in poor cooling performance during machining operations. Similarly, Kumar et al. (2023) recently reported that the addition of nanoparticles boosts the lubricating performance of pure oils; adding that the sustainability of machining operations is greatly improved by the reduction of cutting forces, cutting temperature, tool wear, and surface roughness. Despite the recent clamor for a paradigm shift from conventional materials to composites (polymer nanocomposites), there is still a dearth of scientific reports on improving manufacturing activities in polymer structures sectors like housing, and automobile manufacturing.

In this review, we seek to explore insightful information on nano-based cutting fluids for a wide range of applications. We examine the possibility of using non-destructive nano-coolants loaded with NPs in machining operations. Finally, this review explores pioneer and recent research in the field to update stakeholders in the field on machining operations of carbon fiber-reinforced plastics using nanoparticles-laden fluids for safe and sustainable machining experience.

2 Preparation of nano-based cutting fluids

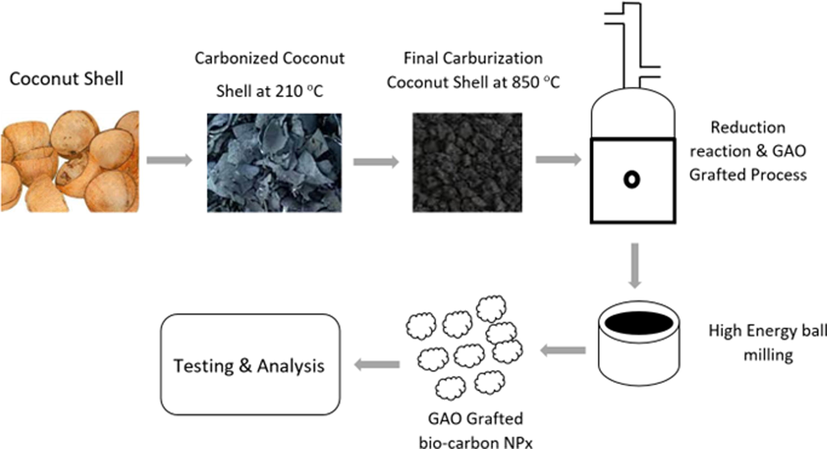

The production economy of nano-coolants plays an important role in determining their acceptability amongst stakeholders in the field (Shahnazar et al., 2016). So far, one-step and two-step methods are the most widely used techniques for the preparation of nano-coolants (Usha and Rao, 2020; Ukoba et al., 2018) Between these two methods, recent research findings reveal that the two-step method is unique and widely accepted because of its cost competitiveness, as well as its adaptability for the wide-ranging production of nano-coolants (Pownraj and Valan Arasu, 2020). The two-step preparation method involves the dispersion of NPs in two rounds of processes. The NPs are then homogeneously distributed in the base oil to form nano-lubricant/coolant. The choice of oils used in this method is often based on cost, good lubrication capacity as well as biodegradability of the resulting wastes (Ni et al., 2021; Makhdoum et al., 2023). The procedure proposed for the synthesis of NPs in this review is summarized in Fig. 1.

Synthesis of GAO-grafted coconut shell carbon nanoparticles. Adapted and modified from (Pownraj and Valan Arasu, 2020).

According to the information provided in Table 1, magnetic mixing and ultrasonic combination were necessary to ensure a uniform distribution of NPs in the base oil. Surfactants were also often used to achieve stability of NPs in the nanosuspension. Of all the reviewed literature summarized in Table 1, only 12% of the authors adopted the one-step methodology for preparing nano-cutting fluids. While magnetic stirring can also lead to significant uniform distribution of microparticles (MPs) in the base oil, it could be grossly inadequate in the case of NPs (Okokpujie and Tartibu, 2020). Therefore, the two-step method of nano-fluid preparation is more favored for the achievement of stable nanosuspension for machining operations.

Reference

Nanoparticles

Base oil type

Preparation Technique

Method

(Singh et al., 2019)

nTiO2

Euphorbia

lathyris oilUltrasonication was utilized to achieve to mix Euphorbia lathyris oil and the NPs in varying percentages and blended with ultrasonic for a period of 1 h.

One-step

(Sen et al., 2020)

nSiO2

Pure palm oil

Between 0.5 and 1.5%, nSiO2 was added to base oil, and afterward ultrasonication process was carried out to achieve uniform dispersion of the NPs in the presence of surfactant to minimize the surface tension and improve silica/pure palm oil nanosuspension.

Two-step

(Pal et al., 2021)

nAl2O3

Vegetable oil

A fixed amount of nAl2O3 plus sunflower vegetable oil was subjected to magnetic stirring for ½ h and then ultrasonicated for ½ h.

Two-step

(Padmini et al., 2019)

nMoS2

Coconut oil

Sesame oil

Canola oilPre-measured quantity of nMoS2 was added to 100 ml of vegetable oil slowly while manually mixing to obtain a uniform suspension. The nanosuspensions were subjected to thorough sonication for 1 h and afterward placed in a bath-type ultra sonicator for another 1 h

Two-step

(Pownraj and Valan Arasu, 2020)

coconut shell carbon

SAE 20 W40

Activated carbon of coconut shell was dispersed in the host oil using a magnetic stirrer for 2 h and afterward final dispersion using a homogenizer at ¾ h 10,000 rpm

Two-step

(Usha and Srinizasa, 2019; Ni et al., 2021)

Soft particle carbon

Fe3O4, Al2O3

Sesame oil

De-ionized waterIntroduction of non-toxic surfactants into sesame oil. The weight of both PEG and SDBS equal that of NPs, hence reduction of surface tension of nanofluids and mixture stability. Magnetic stirring then took place for ½ h, followed closely by ultrasonication for ¾ h in the second step.

Two-step

(Gaurav et al., 2020)

nMoS2

LRT 30 oil (mineral-based)Jojoba oil

(vegetable-based)Dispersion of different concentrations by weight of nMoS2 (0.1%, 0.5%, and 0.9%) in LRT 30 oil and jojoba oil using ultrasonic microprocessor-based vibrator generating pulses of 40 kHz at 100 W

Two-step

(Mirzaasadi et al., 2021; Boyou et al., 2019)

nSiO2

Water-based drilling fluid

nSiO2 was dispersed in two steps, pre- and post-hot rolling at ambient and much higher temperatures (121.11 & 148.88 ◦C) respectively.

Two-step

(Baskaran et al., 2022)

nMoS2

Used cooking oil

Ball milling of oil and nMoS2 for 12 h to allow the nanosuspension to remain homogeneously spaced and distributed.

One-step

(Aramendiz and Imqam, 2019)

nSiO2

nano-grapheneWater-based drilling fluid

300 ml of deionized water was poured into the flask and the NPs were slowly added using a magnetic stirrer. This was followed by an ultrasonication step at 40 kHz and 185 W for 1 h to promote a better dispersion of the NPs.

Two-step

(Sharma et al., 2016)

nTiO2

nAl2O3

nSiO2

vegetable oil–water emulsion

Continuously ultrasonication for 6 h, followed by magnetic stirring to break down nanoparticle aggregates in the base oil.

Two-step

(Dey et al., 2021)

nCeO2

diesel-palm biodiesel blends

A combination of mechanical homogenizer and ultrasonicator and surfactants Span 80, and Tween 80 were used to enhance the stability of the NPs.

Two-step

(Bhaumik et al., 2020)

Graphene and zinc oxide

Glycerol

The mixing of the solution (0.1 wt% graphene oxide and 0.08 wt% zinc oxide plus glycerol followed the common route to magnetic stirring and probe sonication for ¾ h intermittently. The solution was then homogenized using a homogenizer.

Two-step

(Virdi et al., 2020)

nAl2O3

Sunflower oil

Rice bran vegetable oil10 min of magnetic stirring and ½ h of ultrasonication achieved the desired nanosuspension.

Two-step

(Borode et al., 2021)

Al2O3

Graphene nanoplatelet

Followed the procedure described by Virdi et al. (2021) but sonicated for ¾ h instead of ½ h.

Two-step

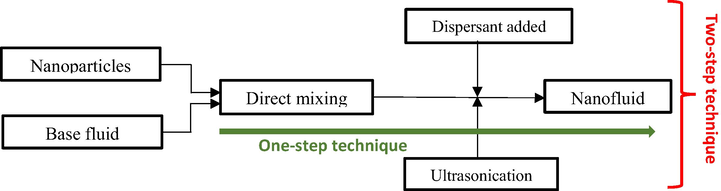

As shown in Table 1, various types of NPs including, metal oxides and other non-metallic materials can be used as nano reinforcements, that could be incorporated into a wide range of base fluids (Sofiah et al., 2021; Urmi et al., 2021). The preparation method is vital to the stability of nanofluid systems, which is needed for the improvement of heat transfer. Therefore, any procedure that would impact the dispersibility of NPs positively, will also support the durability and chemical stability of nanofluids. Some researchers have argued that due to the Brownian motion phenomenon, reduced nano additives favor the stability of nanofluid systems (Kaggwa and Carson, 2019), while others argue that nanofluid chemistry and NP types are more significant to the creation of a steady nanofluid ((Li et al., 2022; Ouabouch et al., 2021). However, in this review, it was discovered that some nanofluids can attain equilibrium without any stabilizers, but could agglomerate up to 250% over s time due to high surface energy). Consequently, we agree that the stability of nanofluid systems is strongly connected to the method of preparation. One-step and two-step preparation methods of nanofluid are schematically described in Fig. 2.

One-step and two-step techniques of nanofluids preparation. Adapted and modified from Mirzaadi et al. (2021).

According to Mirzaadi et al. (2021), the one-step approach involves synthesizing the NPs and producing the nanofluids in one direct process as depicted in Fig. 2. The major advantage of the one-step technique is that the processes occur concurrently. Hence, mitigating issues arising from drying, suspension, and transportation of NPs after synthesis. In addition, the one-step technique significantly reduces the chances of nano additive aggregation (Ali and Salam, 2019). Ali and Salam (2019) further corroborated the findings in the early work by Zhu et al. (Zhu et al., 2004) by alluding to the assertion that pure and uniform NPs are produced by this method. Apart from the challenge of the cost associated with the one-step method, the main drawback is that the residual reactants which help to stabilize the NPs are often left in the nanofluids.

In the two-step method, NPs are synthesized in one stage and dispersed in the base fluid in the second stage through some mechanical processes like mechanical stirring, ultrasonication, and high-pressure homogenization as shown in Fig. 2. It is described as the most cost-effective method for the large-scale preparation of nanofluids. Rapid aggregation of NPs is the main limitation of this method, which is why the formation of surfactants is popular with the two-step method. According to Zhu et al. (2021), the environmental impact of this method is far lesser than the one-step technique. The difference between the two techniques is illustrated in Fig. 2 where ultrasonication and the addition of dispersants are peculiar only to the two-step technique.

3 Pure minimum quantity lubrication of nanofluids

Minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) was introduced to address challenges associated with orthodox lubrication techniques where high-quantity flood coolant is used during the machining operations. This conventional method is plagued with many limitations including the unrestrained spillage of coolant, wet chips with its resulting adverse effect on the cutting tool, allergies to the skin of operators, and disposal issues (Kumar et al., 2023). MQL has a strong influence on the cutting temperature over a wide range of speeds in a machining process, thereby lowering the wear rate of the cutting tool compared to entirely dry machining (Krolczyk et al., 2019). However, lower thermal conductivity cutting fluid, even with the help of MQL cannot fully establish green machining. Recent research findings show that the heat transfer of conventional fluids like oil can be significantly improved by the addition of NPs (Alaboodi et al., 2020), although intensive cooling of tools and chips during machining can be achieved by cryogenic cooling (Bordin et al., 2017; Bermingham et al., 2011).

Nanoparticles are specifically introduced into conventional cutting fluids to enhance the machining process. In a related study, Wickramasinghe et al. (2020) explored the benefits that NPs bring to machining operations. The researchers concluded that NPs are an integral part of effective machining operations. on the other hand, other researchers have reported incessant incidence of scratches and marks on the surfaces of machined parts while using NP-laden cutting fluids for improved thermal stability (Mao et al., 2014; Tran Minh Duc, 2019).

According to Bhardwaj (2020), the use of nanofluids in machining operations was discovered due to the need to control the intense heat generated by microchips at the tool/workpiece interface. Although heat removal is a great achievement in most machining processes, more is needed to understand the remote causes of the defects, as well as the required concentration of nano-additives that will be enough to not only facilitate heat removal but also enhance the surface finish of machined components and conserve cutting fluids.

Virdi et al. (2020) have reported how nanofluids MQL (nMQL) can produce better machining performance of metallic components concerning coefficient of friction, grinding energy, and surface roughness as against pure MQL. Cui et al. (2021) described MQL as an upbeat method to resolve lubrication and cooling challenges for hard-to-machine workpieces, by introducing bio-lubricant with a 10–100 mL/h flow rate into the interface between the workpiece and cutting tool through high-pressure airflow. However, the indiscriminate disposal of coolants still poses a great threat to the environment. Table 2 presents a summary of selected studies on pure and nMQL for sustainable machining.

Reference

Method Deployed

Focus of Study

Machining output measured

Findings

Sustainability perspective

Operations

(Huang et al., 2017)

Nano-MQL

Analysis of the performance of various coolant-lubricant environments.

Surface roughness

Drilling force

Tool wear

Drilling temperatureDrilling force reduced by up to 40% and 82% for pure and nano MQL respectively

Reduction of environmental pollution as well as processing cost of cutting fluid.

Drilling

(Padmini et al., 2019)

Nano-MQL

Performance of vegetable oil-based nano-cutting fluids

Cutting forces

Cutting temperatures

Tool wear

surface roughnessVegetable oil-based nano-cutting fluids have the potential to improve machining performance

Eco-friendly and operator-friendly machining environment.

Turning

(Gaurav et al., 2020)

Nano-MQL

Investigation on jojoba base oil with and without nMoS2

Cutting force

Tool wear

Surface finishUnreinforced and nMoS2, reinforced jojoba oil proved sustainable as a machining alternative.

Clean, healthy, and near-dry working environment, the MQL with jojoba oil is 27% economic compared to commercial mineral oil.

Turning

(Virdi et al., 2020)

Nano-MQL

Investigation of Inconel-718 grinding

Grinding energy

Surface finish

G-ratio

Grinding forceBetter machining performance was achievable due to the high viscosity of sunflower oil and the presence of high saturated fatty acids.

Economic and ecological issues addressed with nano-MQL

Grinding

(Khan et al., 2009)

Pure MQL

Influence of MQL vegetable oil-based cutting fluid on machining

Chip formation modes

Tool wear

Surface finish

Cutting temperatureMQL systems reduce the average chip–tool interface temperature possible compared to wet machining

Reduction in lubricant consumption

Turning

(Sakthi et al., 2021)

Nano-MQL

Study of health hazards associated with traditional machining method.

Metal removal rate

50% coolant reduction during machining and also.

Reduce environmental impact

Turning

MQL offers unique benefits in terms of cost (owing to reduced coolant usage and large disposal saving), as well as ecological and human safety. Several studies have reported MQL in the past (Maruda et al., 2015; Dhar et al.2006). In another study, Tasdelen et al. (Tasdelen et al., 2008) reported that controlled tool wear and shorter chip lengths were attainable with MQL than conventional metal-working fluids (MWFs) in hardened steel drilling. In a separate study, another group of researchers compared the use of MQL with traditional MWFs in AISI 9310 turning in terms of tool life and surface quality (Khan et al., 2009). Both teams concluded that MQL presented better results than the traditional MWFs. However, Zhang et al. (2015) identified surface burning as a major drawback in the MQL grinding of a nickel alloy. As described in the preceding sections of this review study, pure MQL is fast giving way to nMQL because of the latter’s faster and more effective heat removal advantage. The reports point to improved machining performance as all the outputs measured (cutting force, cutting temperature, tool wear, and surface roughness) reduced considerably, compared to conventional machining (Sabarinathan et al., 2020). It can also be deduced from Table 2 that both methods are human and environment-friendly and in agreement with the work of Agapiou et al. (2018).

Table 3 shows the growing acceptability of vegetable oil as a viable replacement for petroleum-based coolants, as well as lends credence to the fact that green machining is one of the most important evolving industrial study areas in recent times.

Reference

Nanoparticles type

Component

Base oil

Focus of study

Findings

Operation (Test)

(Madanchi et al., 2019)

–

metals

Vegetable oil

Cutting fluid strategies on environmentally conscious machining systems

The supply strategy type of cutting fluid has a significant impact

varied

(Pal. Et al., 2021)

Al2O3

AISI 321 stainless steel

Vegetable oil

Assessment of coolant-lubricant environments concerning drilling parameters.

MQL drilling with Al2O3/vegetable-oil-based cutting fluid accomplished better performance as compared to drilling with other techniques.

Drilling

(Agapiou, 2018)

Carbon onion

Steel gear

MWF

Performance evaluation of carbon nano-onions cutting fluids.

Cost reduction in the machining of steel gears with CNO water-based or oil-cutting fluids.

varied

(padmini et al., 2019)

nGraphene

AISI 1040 steel

coconut oil and canola oil

Assessment of vegetable oil-based nano-cutting fluids

Coconut oil-based nanographene cutting fluids are effective in causing a reduction in cutting forces & temperatures, tool wear, and surface roughness.

Turning

(Sun et al., 2021)

Nano silica

Inconel 690

pure palm oil

Performance of minimum quantity nano-green lubricant in milling.

1% silica-deposited palm oil medium performs better concerning all machining responses.

Milling

(Usha and Rao, 2020)

Al2O3

AISI 1045 steel

De-ionized water

Study of the optimal cutting force while turning AISI 1045 steel using nAl2O3 particles.

The significant parameters influencing cutting force are depth of cut, and feed rate followed by MQL flow rate.

Turning

(Ni et al., 2021)

Fe3O4, Al2O3,

CarbonAISI 1045 steel

Sesame oil

Assessment of MQL broaching AISI 1045 steel with NPs reinforced sesame oil.

Carbon nanofluid demonstrated the best results in broaching load, broaching vibration, and surface quality concerning other cutting fluids.

Broaching

(Gaurav et al., 2020)

nMoS2

Titanium alloy

Jojoba oil

Study on vegetable oil mixed with and without nMoS2 in hard machining with MQL.

Jojoba oil, in pure and nano-fluidic conditions, proved a strong and sustainable replacement for commercial mineral oil for MQL turning.

Turning

(Baskaran et al., 2022)

MoS2

SAE 1144 steel

waste cooking oil

Effect of the concentration of nMoS2-laden waste cooking oil coolant in cutting force reduction.

nMoS2 enriched waste cooking oil-based wet machining reduced the cutting force by 27.53% more than the green machining method.

varied

(Dey et al., 2021)

CeO2

metals

palm biodiesel

Combustion-performance-emission characteristics of cerium oxide (CeO2)

Adding nCeO2 to palm biodiesel blends improves the thermal efficiency of the brake and reduces energy consumption in practice.

varied

(Virdi et al., 2020)

0.5% Al2O3

IN718 alloy

Vegetable oils

Investigating forces, surface roughness, grinding energy, and -ratio under MQL, flood

Significant improvement in grinding performance of Inconel-718 alloy with respect to G-Ratio, Grinding Energy, and Surface Roughness.

Grinding

(Bhardwaj, 2020)

Al and Cu

Steel ball

Toluene

Synthesis of 0.025 vol% Al and Cu-based nanofluids by two-step technique.

Nanoparticles with lower density, good conducting properties, and finer particle size positively impact dispersion stability in most of the conventional heat transfer fluids.

Milling

(Cui et al., 2021)

α-Al2O3

Al2O3/TiC micro-composite ceramic

Vegetable oil

Green cutting performance for the bio-inspired microstructure on Al2O3/TiC composite ceramic surface.

Higher transport speed amounted to more adequate lubrication and lower cutting load.

varied

(Sakthi et al., 2021)

Al2O3

magnesium alloy

Varied

Effect of nano additives on Mg alloy during turning operation with MQL

MRR which is influenced by cutting speed, constant feed, and depth of cut and nano additives saves 50% of coolant by the MQL system.

Turning

(Mahmoud et al., 2020)

Inert fibres

Unspecified

Water-Based Muds

Effect of anionic and fiber on cutting carrying capacity of polymeric suspensions.

The cutting carrying capacity of nanosuspensions was increased by increased anionicity owing to improved particle–particle and particle-polymer repulsion forces.

Drilling

(Bhaumik et al., 2020)

Graphene oxide,

ZnOEN21 workpiece

Glycerol

Replacement of non-biodegradable and safe commercial cutting fluids by glycerol-based lubricants.

Carbonaceous nanoparticles additive performed better in respect of machined surface quality.

Turning

(Patole et al., 2021)

MWCNTs

steel AISI 4340.

ethylene glycol

Effect of cutting conditions, and nano coolant on machining parameters.

Feed rate and depth of cut are two major input parameters that influence surface roughness and cutting force during machining.

Turning

(Elsheikh et al., 2021)

Al2O3 and CuO

AISI 4340 alloy

Vegetable oil

nMQL technique for turning of AISI 4340 alloy.

CuO/oil nanofluid improved surface finish and tool wear compared with Al2O3/oil nanofluid.

Turning

(Haq et al., 2021)

unspecified

IN718

Vegetable oil

Machining improvement of face milling of Inconel 718 by using two different lubrication conditions.

Depth of cut is the most significant process parameter influencing SR, temperature, MRR, and power.

Milling

(Mahadi et al., 2017)

Boric Acid Powder

AISI 431 Steel

Palm kernel oil

Performance evaluation of boric acid powder reinforced palm kernel oil for machining.

Boric acid powder-aided lubricant machining outperformed conventional lubricant by 7.21%.

turning

(Ghatge et al., 2018)

TiN/Al2O3/TICN/TiN cutting insert

Duplex Stainless Steel

Coconut and neem oil

Non-biodegradable mineral oil is replaced with vegetable oil as cutting fluid.

Lower tool wear results in low cutting speed and high feed rate.

Turning

4 Factors influencing the performance and qualities of nano-cutting fluids

Having demonstrated the superiority of nano-cutting fluids over dry and water-based machining operations, it is pertinent to touch on the factors influencing the performance of the nanofluids to build a formidable foundation for future research. In this section, a brief review of these elements is done.

Bhardwaj (Bhardwaj, 2020) confirmed, and reported that viscosity is one of the most important factors affecting the dispersion of NPs and the equilibrium of nanosuspension systems. The researcher demonstrated that viscosity increases with a lower density of Al2O3 NPs than with CuO-dispersed nanofluids. This could be attributed to the role smaller particle size plays in the thermal conductivity and stability of nanofluids (Ouabouch et al., 2021). The shape of NPs is also said to affect the stability and thermal conductivity of nanofluids. Particles with cylindrical morphologies have a higher thermal conductivity than nanofluids with spherical particles. In an investigation of the influence of aspect ratio on thermal conductivity and viscosity of nanofluids, Ouabouch et al. (Ouabouch et al., 2021) reported that fibrous nAl2O3 exhibited a greater improvement in thermal conductivity and viscosity than spherical nAl2O3 nanofluids, which could be attributed to the larger surface area common with cylindrical-shaped particles.

The pH values of nanofluids which play an important role in the corrosion of the interface between the tool and workpiece are another factor to consider in formulating nanofluids. This is because of its impact on thermal conductivity and viscosity as well as particle clustering and stability of nanofluids. Fuskele and Sarviya (Fuskele and Sarviya, 2018) presented a close relationship between the stability and electrokinetic properties of nanofluids. researchers concluded that pH control is vital to achieving stability in nanofluids. Another group of researchers further confirmed that nanosuspension enjoys more stability when the pH is further away from its isoelectric point (IEP), where the surface charge of the nanoparticles and the values of the zeta potential is zero (Sharma and Gupta, 2016). The zeta potential typifies the voltage between the surface of the nanoparticles and the adjacent stationary layer of the base fluid (Sezer et al., 2019). As a result of these findings from previous research, we submit in this review that, the pH value of nanofluids is better maintained around the neutral point to forestall possible dissolution of the nanoparticles with the alkaline and acid-triggered corrosion at the heat transfer interface (Gbadimi et al., 2011). In another investigation of the effect of pH on the stability of nanofluids, Sahooli and Sabbaghi (Sahooli and Sabbaghi, 2013) concluded that the best stability and enhancement of thermal conductivity of NPs-laden fluids is achievable only with the optimal pH of the nanosuspension. Borode et al. (Borode et al., 2021) compared the thermal conductivity, density, specific heat, and viscosity of graphene nanoplatelet (GNP) with alumina hybrid nanofluids at different mixing ratios. They observed that the addition of NPs into base fluids improves the cooling ability with less impact on viscosity.

Karmakar et al. (Karmakar et al., 2017) studied the quality and performance of bio-lubricants. They observed that the quality of any nanofluids depends on certain physical properties which include viscosity index, flash point, cloud point, and thermal stability of the nanofluids. Other properties are oxidation stability, shear stability, iodine value as well as the density of the particles-laden base oil. The thermal stability of the nanofluids depends largely on their change in viscosity in response to temperature changes. According to Che (Che, 2014), higher viscosity index and flash point nanofluids can withstand temperature fluctuations during machining operations. Therefore, regardless of the synthesis method, the thermal conductivity of all nanofluids gets enhanced by temperature (Ouabouch et al., 2021).

5 Machining of carbon fibre reinforced plastics: How conventional?

According to Uhlmann et al. (Uhlmann et al., 2014), CFRPs are widely used in manufacturing. The reinforcing fibers get randomly cut and deflected under the action of the cutting edge, thereby causing delamination in the form of fiber overhang and breakout at the machined edges. In recent times, CFRPs have become widely accepted in a range of applications including space engineering and military equipment manufacturing. Hence, they are envisaged to replace conventional materials owing to their low density, high strength and stiffness, good toughness, fatigue creep, wear and corrosion resistance, low friction coefficient, and good dimensional stability (Uhlmann et al., 2014). Although they are often fabricated to near net shapes by techniques like autoclave moulding, compression moulding, or filament winding, post-machining operations like turning, milling, or drilling is often needed to guarantee that the composite parts meet geometrical tolerance, surface quality, and other functional requirements (Che, 2014).

Turning is mostly used to achieve a desired dimensional tolerance on cylindrical surfaces during machining operations. Most studies reported on CFRP composite machining prove that minimizing surface roughness is challenging (Rajasekaran et al., 2011). Various methods such as experimental measurements, theoretical modeling, and fuzzy logic algorithms, have been applied to understand the surface quality and dimensional properties of CFRP components during a turning process. Santhanakrishnan et al. (Santhanakrishnan et al., 1992) presented an experimental investigation involving cutting and tool performance in terms of force responses, tool wear, surface roughness, and chip formation using sintered carbides. Their findings revealed that sintered carbide tools can be used to generate homogenous surface finishes in CFRP machining if flank wear is carefully checked. In another study involving polycrystalline diamond turning, Palanikumar (Palanikumar, 2008) used Taguchi and response surface methodologies to reduce the surface roughness of CFRP. The good surface finish was linked to high cutting speeds, high depths of cut, and low feed rates which are in agreement with the the findings of Lee (Lee, 2001) who experimentally determined that an increased feed rate favors increased surface roughness, while the depth of cut and cutting speed do not have any significant relationship with surface roughness.

In the manufacture of CFRP parts, milling is the most frequently used machining operation (Sarma et al., 2008). It is suited for the accurate machining of complex shapes on CFRP components as a corrective operation to produce well-defined and high-quality surfaces that often require the removal of excess material to control tolerances (Davim and Reis, 2005). The type of reinforcing agents used significantly impacts the machinability of CFRP composite and the possible delamination and burrs with uncut fibers that would occur due to the complexity of the interaction between the end mill and CFRP parts. Also, Kalla et al. (Kalla et al., 2010) suggested an exact forecast of thrust and axial cutting forces as a way of regulating the process parameters to circumvent delamination and reduce burr formation to the barest minimum. Sorrentino and Turchetta (Sorrentino and Turchetta, 2014), in a different study on the milling of CFRP parts, reported that the radial and tangential components of the cutting forces have a direct influence on the feed speed, depth of cut, and chip thickness. They concluded by proposing an experimental model for determining the cutting force components for CFRP milling.

Elgnemi et al. (Elgnemi et al., 2017; 2021) categorized CFRPs as hard-to-cut materials because of the abrasiveness of the reinforcing fillers and the resulting low transverse strength of composite layers leading to demarcation under machining forces. Hygroscopicity is reportedly a major limitation to the application of flood lubrication in the grinding of the composites. Researchers in this field unanimously embrace MQL which has proven to be more sustainable and environment-friendly (but whose moisture could damage the structural integrity of CFRP), or dry machining which impacts both the operators and the environment negatively.

6 Future of nano-based cutting fluids application in CFRPs

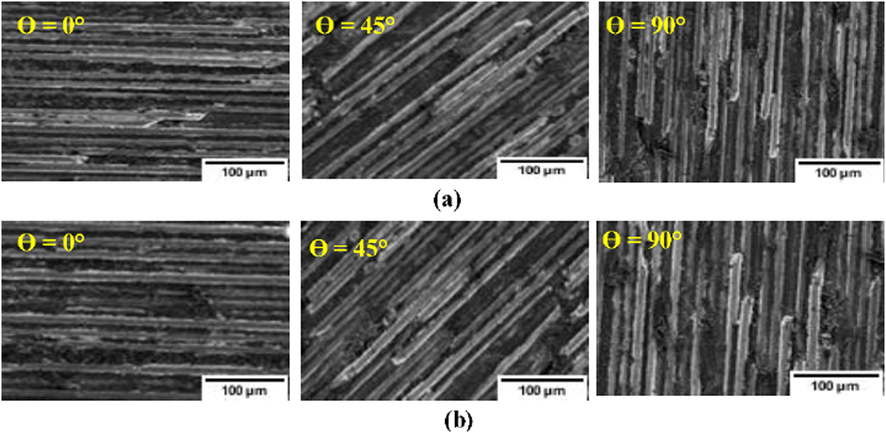

In spite of the reduced machining experience with CFRPs, Gao et al. (Gao et al., 2021) suggested that machining operations such as drilling and milling cannot be eliminated in polymer composite manufacturing, especially during the assembling of parts. Wet machining with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of various displaced fiber orientation angles, comparing the surface finishes obtained in a set of milling operations of CFRPs are presented in Fig. 3.

SEM images of a machined surface obtained after milling operation (a) ACF vegetable oil conditions (b) dry (unlubricated).

Adapted from Elgnemi et al., 2021

The images illustrate surface damage of unidirectional CFRP laminates at 0°, 45o, and 90° displaced fiber orientation angles (FOAs). It can be observed that the surfaces for 45° and 90° orientation are more severely scratched than 0°. A careful comparison of the two sets of images shows that vegetable oil-conditioned milling (Fig. 3(a)) produces better surface finishes than unlubricated surfaces (Fig. 3(b)). Delamination percentage when cutting at TFOAs of 0°, 30° 45°, 60°, and 90° were enhanced by 65%, 91%, 54%, 66%, and 75%, respectively, under vegetable oil conditions. Erturk et al. (Erturk et al., 2021) did a comparative study of the mechanical and machining performance of polymer hybrid and carbon fiber epoxy composite materials. Although their investigation was focused on dry machining, their major conclusions were centered on the reduction in tool life with dry machining. Hence, the overall increase in machining cost. Similarly, Jemielniak (Jemielniak, 2021) gave some insights into recent research on the machining of some difficult-to-cut materials (which include CFRP) for the aerospace industry. They shared the sentiments of previous authors on delamination on hole surfaces being a major failure arising from the drilling of CFRP composites and suggesting high-performance cooling techniques and hybrid cutting processes as a solution to the bottlenecks. Their work covers cryogenic machining, high-pressure cooling, MQL, and cryogenic MQL cooling. Comparisons of the different cooling techniques are presented in Fig. 4. During dry machining, the cutting area temperature could rise from 200 °C to 400 °C, which is higher than the glass transition temperature of the matrix (between 80 °C and 180 °C), resulting in thermal degradation, as well as debonding at the fiber–matrix interface (Jemielniak, 2021).

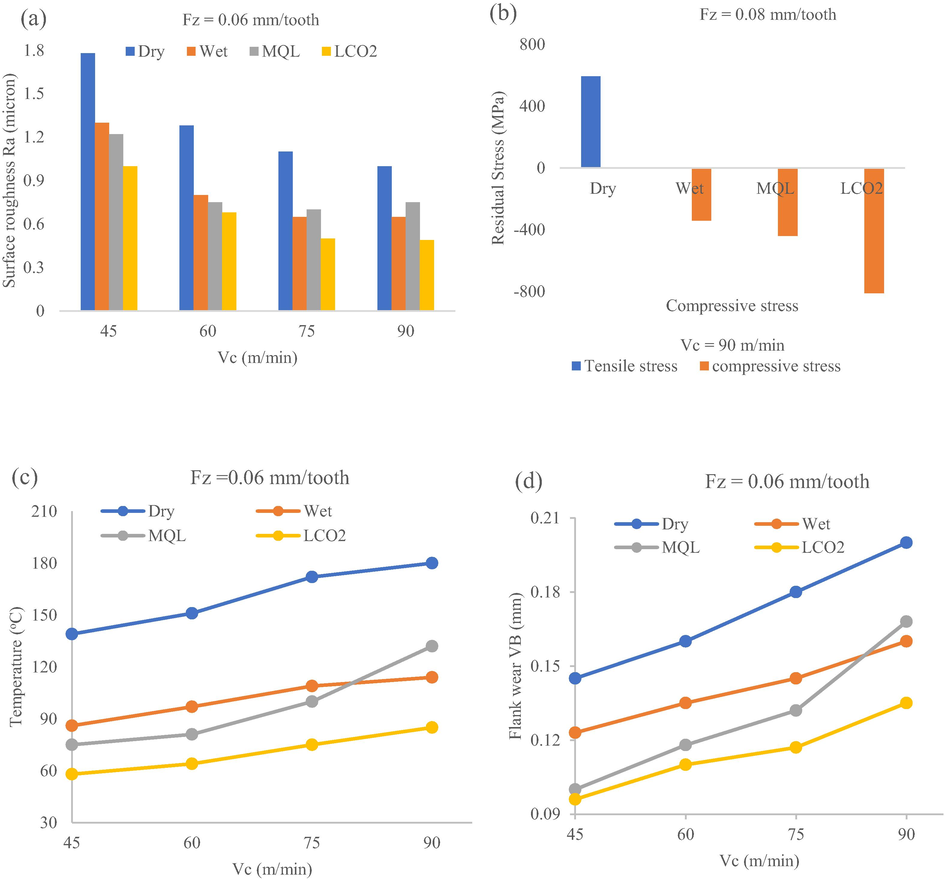

Results of surface toughness (a), residual stress (b), temperature (c), and wear (d) for different cutting approaches. Adapted and modified from (Jemielniak, 2021).

According to the graphical results presented in Fig. 4, the cryogenic approach to the machining of CFRP is more promising for improved surface finishes compared to other approaches. Because the strategy takes the temperature of the workpiece to the sub-zero zone, cutting temperatures are kept down during the machining process, and tool life is thus improved. In the process, the fillers are stiffened and easily cut, avoiding delamination., Comparatively, dry machining only raises the cutting temperature as the speed increases. The residual stress of different approaches also reduce with the use of nanofluids and is the least with the cryogenic approach.

In spite of the superior properties of nano-based cutting fluids as reported in this review, there are several challenges facing the development and application of nanofluid technology. One of the major challenges is the long-term stability of NPs in the nanosuspension. One of the most important requirements of the development of nano-based cutting fluids is to ensure that particles (which naturally aggregate due to certain forces including strong Van der Waals attraction, drag, thermophoresis, Brownian, and electric double layer forces) attain effective separation in the base oil (Zhao et al., 2021). Another problem is the behavior of nanofluids in turbulent flow. The scarcity of research publications in this area of machining makes it difficult to draw any meaningful conclusion that is expected to serve as a guide for future researchers. Nanomaterials are generally not cheap, and the price of NPs is not regulated. According to Kaggwa and Carson (Kaggwa and Carson, 2019), 100 g of Al2O3 and CuO nanoparticles, as of 2019, cost $492 and $80 respectively. This makes cost another important factor in the synthesis and application of nanofluids.

The general application of nanofluids, considered in its early stages, should lead to increased studies on the potential applications of nanofluids. Scientists and chemists actively participate in the characterization of nanofluids for various applications, while materials and mechanical engineers are fascinated by experiments on the application of nanofluids (Yu et al., 2017). However, there is still a missing common ground that provides general guidelines on the preparation and characterization of stable dispersed thermal nanofluids among these researchers of different disciplines.

7 Conclusion

This review evaluated the formulation of nano-based cutting fluids and their application in carbon fiber-reinforced plastics (CFRPs). It provides a summary of current trends in this field by exploring and analyzing the latest published literature in the field. The research efforts in this review examined the different methods of cutting fluid preparation as well as a comparative study of conventional approaches to nanofluid preparation (one-step and two-step methods). The two-step approach is gaining wide acceptance amongst researchers in recent times due to its environmental sustainability potential. The concept of nano Minimum Quantity Lubrication (nMQL) is used for CFRP manufacturing due to the numerous benefits mentioned in recent conversations around the replacement of conventional materials in a wide range of applications. Not only does it reduce the quantity of cutting fluid required for simple drilling, it also promotes the application of CFRPs and motivates future researchers to apply a sustainable approach to manufacturing.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Research Fund (NRF) under the aegis of the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFund), Nigeria, (TETF/ES/DR&D/CE/NRF2020/SETI/113/VOL.1), the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa for funding this research, and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, CA, United States specifically for supporting the open access publication of this research.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Magnetically processed carbon nanotube/epoxy nanocomposites: Morphology, thermal, and mechanical properties. Polym. 2010;51(7):1614-1620.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Performance evaluation of cutting fluids with carbon nano-onions as lubricant additives. Procedia. Manuf.. 2018;26:1429-1440.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Non-Traditional Machining Process of Composite Materials using Renewable Lubricants. Int. J. Recent Technol. & Eng. (IJRTE). 2020;9(1):929-933.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A review on nanofluid: preparation, stability, thermophysical properties, heat transfer characteristics, and application. SN Appl. Sci.. 2019;2(10):1-17.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Water-based drilling fluid formulation using silica and graphene nanoparticles for unconventional shale applications. J. Pet. Sci. & Eng.. 2019;179:742-749.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon nanotubes reinforced with natural/synthetic polymers to mimic the extracellular matrices of bone – a review. Mater. Today Chem.. 2021;20

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of molybdenum disulfide particles’ concentration on waste cooking oil nanofluid coolant in cutting force reduction on machining SAE 1144 steel. Mater. Today: Proceed.. 2022;2–5

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Review of recent research on materials used in polymer–matrix composites for body armor application. J. Compos. Mater.. 2018;52(23):3241-3263.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New observations on tool life, cutting forces, and chip morphology in cryogenic machining Ti-6Al-4V. Int. J. Mach. Tool Manuf.. 2011;51:500e11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of AL and Cu base nanofluids. Mater. Today: Proceed.. 2020;37(Part 2):3139-3142.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nano and micro additive glycerol as a promising alternative to existing non-biodegradable and skin unfriendly synthetic cutting fluids. J. Clean Prod. 2020;263:121383

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bokobza, L., 2019. Natural rubber nanocomposites: A review. In Nanomaterials, 9(1), MDPI AG. Doi: 10.3390/nano9010012.

- Experimental investigation on the feasibility of dry and cryogenic machining as sustainable strategies when turning Ti6Al4V produced by Additive Manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod.. 2017;142:4142e51.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of the thermal conductivity, viscosity, and thermal performance of graphene nanoplatelet-alumina hybrid nanofluid in a differentially heated cavity. Frontiers in Energy Res.. 2021;9:1-15.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Experimental investigation of hole cleaning in directional drilling by using nano-enhanced water-based drilling fluids. J. Pet. Sci. & Eng.. 2019;176:220-231.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Che, D., 2014. Machining of carbon fibre reinforced plastics/polymers: a literature review, 136. Doi: 10.1115/1.4026526.

- Fabrication, transport behaviors and green interrupted cutting performance of bio-inspired microstructure on Al2O3/TiC composite ceramic surface. J. Manuf. Proc.. 2021;75:203-218.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Damage and dimensional precision on milling carbon fiber-reinforced plastics using Design experiments. J. Mater. Process. Technol.. 2005;160(2):160-167.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental investigation on combustion-performance-emission characteristics of nanoparticles added biodiesel blends and tribological behaviour of contaminated lubricant in a diesel engine. Energ. Conv. & Manag.. 2021;244:114508

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) on tool wear and surface roughness in turning AISI-4340 steel. J. Mater. Proc. Technol.. 2006;172(2):299-304.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of atomization-based cutting fluid sprays in milling of carbon fibre reinforced polymer composite. J. Manuf. Proc.. 2017;30:133-140.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Milling performance of CFRP composite and atomised vegetable oil as a function of fibre orientation. Mater.. 2021;14(8)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A new optimized predictive model based on political optimizer for eco-friendly MQL-turning of AISI 4340 alloy with nano-lubricants. J. Manuf. Proc.. 2021;67:562-578.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A comparative study of mechanical and machining performance of polymer hybrid and carbon fibre epoxy composite materials. Polym. & Polym. Compos.. 2021;29(9):S655-S666.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of the machinability of carbon fiber composite materials in function of tool wear and cutting parameters using the artificial neural network approach. Materials. 2019;12:2747.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Natural rubber nanocomposites. J. Macromolec. Sci., Part A: Pure & Appl. Chem.. 2017;54(9)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grindability of carbon fiber reinforced polymer using CNT biological lubricant. Scientif. Rep.. 2021;11(1):1-14.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of jojoba as a pure and nano-fluid base oil in minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) hard-turning of Ti–6Al–4V: A step towards sustainable machining. J. Clean Prod.. 2020;272:122553

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Improvement of machinability using eco-friendly cutting oil in turning duplex stainless steel. Mater. Today: Proceed.. 2018;5(5):12303-12310.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dry machining: a step towards sustainable machining – challenges and future directions. J. Clean. Prod.. 2017;165:1557-1571.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced fatigue and durability of carbon black/natural rubber composites reinforced with graphene oxide and carbon nanotubes. Eng. Fract. Mechanics. 2020;223

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Review of mechanochromic polymers and composites: from material design strategy to advanced electronics application. Compos. Part B: Eng.. 2021;227

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating the effects of nano-fluids based MQL milling of IN718 associated to sustainable productions. J. Clean. Prod.. 2021;310:127463

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Flow-resistance analysis of nano-confined fluids inspired from liquid nano-lubrication: A review. Chinese J. Chem. Eng.. 2017;25(11):1552-1562.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of mechanical properties of CNT-rubber nanocomposites. Mater. Today: Proceed.. 2020;45:7183-7189.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Review of new developments in machining of aerospace materials. J. Machine Eng.. 2021;21(1):22-55.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon nanomaterials: a new sustainable solution to reduce the emerging environmental pollution of turbomachinery noise and vibration. Frontiers in Chemistry. 2020;8:1-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Studies on natural rubber nanocomposites by incorporating zinc oxide modified graphene oxide. J. Rubber Res.. 2020;23(4):311-321.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Developments and future insights of using nanofluids for heat transfer enhancements in thermal systems: a review of recent literature. Int. Nano Lett.. 2019;9(4):277-288.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of Cutting Forces in Helical End Milling Fibre Reinforced Polymers. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf.. 2010;50(10):882-891.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemically modifying vegetable oils to prepare green lubricants. Lubricants. 2017;5(4):1-17.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of minimum quantity lubrication on turning AISI 9310 alloy steel using vegetable oil-based cutting fluid. J. Mater. Proc. Technol.. 2009;209(15–16):5573-5583.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ecological trends in machining as a key factor in sustainable production e A review. J. Clean. Prod.. 2019;218:601-615.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, S., Prasad, L., Patel, V.K., Kumar, V., Kumar, A., Yadav, A., Winczek, J. 2021. Physical and mechanical properties of natural leaf fiber-reinforced epoxy polyester composites, Polym., 13(9). MDPI AG. doi:10.3390/polym13091369.

- State-of-the-art in sustainable machining of different materials using nano minimum quality lubrication (NMQL) Lubric.. 2023;11(64):1-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Precision machining of glass fiber reinforced plastics with respect to tool characteristics. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol.. 2001;17(11):791-798.

- [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z., Xiang, J., Liu, X., Li, X., Li., X., Shan., B. Chen, R., 2022. A combined multiscale modelling and experimental study on surface modification of high-volume micro-nanoparticles with atomic accuracy, Int. J. Extrem. Manuf, 4, (025101 (16pp), Doi: 10.1088/2631-7990/ac529c.

- Improving the thermal and mechanical properties of an alumina-filled silicone rubber composite by incorporating carbon nanotubes. Xinxing Tan Cailiao/New Carbon Mater.. 2020;35(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and application of an environmentally friendly compound lubricant based biological oil for drilling fluids. Arabian J. Chem.. 2022;15(3):103610

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Modelling the impact of cutting fluid strategies on environmentally conscious machining systems. Procedia CIRP. 2019;80:150-155.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Use of boric acid powder aided vegetable oil lubricant in turning AISI 431 steel. Procedia Eng. 2017;184:128-136.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Settling behaviour of fine cuttings in fibre-containing polyanionic fluids for drilling and hole cleaning application. J. Petrol. Sci. & Eng.. 2020;199:108337

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Significance of entropy generation and nanoparticle aggregation on stagnation point flow of nanofluid over stretching sheet with inclined Lorentz force. Arabian J. Chem.. 2023;16(6):104787

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The tribological properties of nanofluid used in minimum quantity lubrication grinding. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2014:1221-1228.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of cooling conditions on the machining process under MQCL and MQL conditions. Tehnicki Vjesnik. 2015;22(4):965-970.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermal and physico-mechanical stability of recycled high-density polyethylene reinforced with oil palm fibres. Eng. Sci. & Technol., an Int. J.. 2017;20(6):1623-1631.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon nanotube reinforced natural rubber nanocomposite for anthropomorphic prosthetic foot purpose, Scientif. Rep.. 2019;9(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable approach for corrosion control in mild steel using plant-based inhibitors: A review. Materials Today Sustainability 2023100373

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon nanotube-reinforced elastomeric nanocomposites: A review. Intl J. Smart & Nano Mater.. 2015;6(4):211-238.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Improving the rheological properties and thermal stability of water-based drilling fluid using biogenic silica nanoparticles. Energ. Rep.. 2021;7:6162-6171.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, L, Ansari, M.N.M., Pua, G., Jawaid, M., Islam, M.S.A., 2015. Review on natural fiber reinforced polymer composite and its applications. Int. J. Polym. Sci., Doi: 10.1155/2015/243947.

- Evaluation of MQL broaching AISI 1045 steel with sesame oil containing nano-particles under best concentration. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021;320:128888

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Performance investigation of the effects of nano-additive-lubricants with cutting parameters on material removal rate of al8112 alloy for advanced manufacturing application. Sustainability (Switzerland). 2020;13(15)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oleiwi, J.K., Hamad, Q.A., Abdulrahman, S.A., 2022. Flexural, impact and max. shear stress properties of fibers composite for prosthetic socket, Mater. Today: Proceed., Doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2021.12.368.

- Stability, thermophysical properties of nanofluids, and applications in solar collectors. A review. 2021;8:659-684.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of green nanocutting fluids on machining performance using minimum quantity lubrication technique. Mater. Today: Proceed.. 2019;18:1435-1449.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Performance evaluation of the minimum quantity lubrication with Al2O3- mixed vegetable-oil-based cutting fluid in drilling of AISI 321 stainless steel. J. Manuf. Proc.. 2021;66:238-249.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Application of taguchi and response surface methodologies for surface roughness in machining glass fibre reinforced plastics by PCD tooling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol.. 2008;36(1):19-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of surface roughness and cutting force under MQL turning using nano fluids. Mater. Today: Proceed.. 2021;45:5684-5688.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Improvement of machinability of Ti and its alloys using cooling-lubrication techniques: A review and future prospect. J. Mater. Res. & Technol.. 2021;2021(11):719-753.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and characterization of low-cost eco-friendly GAO grafted bio–carbon nanoparticle additive for enhancing the lubricant performance. Diamond & Related Materials. 2020;108:107921

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multi-functional carbon fibre composites using carbon nanotubes as an alternative to polymer sizing. Scientif. Rep.. 2016;6

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Application of fuzzy logic for modelling surface roughness in turning CFRP composites using CBN tool. Prod. Eng. Res. Dev.. 2011;5(2):191-199.

- [Google Scholar]

- Performance evaluation of vegetable oil-based nano cutting fluids in machining using grey relational analysis-A step towards sustainable manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod.. 2016;172:2862-2875.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect on tool life by addition of nanoparticles with the cutting fluid. Mater. Today: Proceed.. 2020;33:2940-2954.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lignocellulosic biomass-derived nanocellulose crystals as fillers in membranes for water and wastewater treatment: a review. Membranes. 2022;12(3):320.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- CuO nanofluids: the synthesis and investigation of stability and thermal conductivity. J. Nanofluids. 2013;1:155-160.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sakthi, S., Hariharan, S.R., Mahendran, S., Azhagunambi, R. 2021. Effect of nano additives on magnesium alloy during turning operation with minimum quantity lubrication, Mater. Today: Proceed., doi:10.1016/j.matpr2021.04.238.

- Effective reinforcements for thermoplastics based on carbon nanotubes of oil fly ash. Scientif Rep.. 2019;9(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- investigation into the machining of carbon-fibre-reinforced plastics with cemented carbides. J. Mater. Process. Technol.. 1992;30(3):263-275.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modelling and analysis of cutting force in turning of gfrp composites by CBN tools. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos.. 2008;27(7):711-723.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hübner: C Erratum to: Thermoplastic Nanocomposites with Carbon Nanotubes 2013

- [CrossRef]

- The use of composite materials in modern orthopaedic medicine and prosthetic devices: A review. Compos. Sci. & Technol.. 2011;71(16):1791-1803.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic effect of silica and pure palm oil on the machining performances of Inconel 690: A study for promoting minimum quantity nano doped-green lubricants. J. Clean Prod.. 2020;258:120755

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive review on synthesis, stability, thermophysical properties, and characterization of nanofluids. Powder Technol.. 2019;344:404-431.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhancing lubricant properties by nanoparticle additives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energ. 2016;41(4):3153-3170.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and evaluation of stable nanofluids for heat transfer application: A review. Exp. Thermo. Fluid Sci.. 2016;79:202-212.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of TiO2, Al2O3 and SiO2 Nanoparticle based Cutting Fluids. Mater. Today: Proceed.. 2016;3(6):1890-1898.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sustainability of a non-edible vegetable oil-based bio-lubricant for automotive applications: A review. Proc. Safety & Enviro. Protection. 2017;111:701-713.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Immense impact from small particles: review on stability and thermophysical properties of nanofluids. Sustainable Energy Technol. & Assessments. 2021;48(5):101635

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino, L., Turchetta, S., 2014. Cutting forces in milling of carbon fibre reinforced plastics. 2014.

- Synergistic effect of carbon nanotubes and wood-derived carbon scaffold on natural rubber-based high-performance thermally conductive composites. Compos. Sci. & Technol.. 2021;213

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Studies on minimum quantity lubrication (MQL) and air cooling at drilling. J. Mater Proc Technol. 2008;200(1–3):339-346.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tran Minh Duc, TTL, TQC., 2019. Performance evaluation of MQL parameters using Al2O3 and MoS2 nanofluids in hard turning 90CrSi steel, Lubricants, 7, 1–17. Doi: 10.3390/lubricants7050040.

- Machining of carbon fibre reinforced plastics. Procedia CIRP. 2014;24:19-24.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation methods and challenges of hybrid nanofluids: a review. J. Adv. Res. in Fluid Mechanics & Thermal Sci.. 2021;78(2):56-66.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ukoba, K.O., Eloka-Eboka, A.C., & Inambao, F.L. (2018). Experimental optimization of nanostructured nickel oxide deposited by spray pyrolysis for solar cells application. Available in ukzn-dspace.ukzn.ac.za.

- Optimisation of parameters in turning using herbal based nano cutting fluid with MQL. Materials Today: Proceedings. 2020;22:1535-1544.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable development of carbon nanocomposites: synthesis and classification for environmental remediation. J. Nanomater., Hindawi Limited. 2021

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of nano-based metal working fluids on machining process - A Review. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater Sci. & Eng.. 2018;390(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Performance evaluation of inconel 718 under vegetable oils based nanofluids using minimum quantity lubrication grinding. Mater Today: Proc.. 2020;33:1538-1545.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W., Zhu, Y., Liao, S., Li, J., 2014. Carbon nanotubes reinforced composites for biomedical applications, BioMed Res. Int., Hindawi Publishing Corporation. Doi: 10.1155/2014/518609.

- Recent advances on high performance machining of aerospace materials and composites using vegetable oil-based metal working fluids. J. Clean Prod. 2020;310:127459

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Update on current approaches, challenges, and prospects of modeling and simulation in renewable and sustainable energy systems. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2021;150:111506.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dispersion stability of thermal dispersion stability of thermal nanofluids. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int.. 2017;27:531-542.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermoplastic/natural filler composites: A short review. In J. Physical Sci.. 2019;30:81-99.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recent advancements in nano-lubrication strategies for machining processes considering their health and environmental impacts. J. Manuf. Proc.. 2021;68(PA):481-511.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Experimental evaluation of MoS2 nanoparticles in jet MQL grinding with different types of vegetable oil as base oil. J. Clean. Prod.. 2015;87:930-940.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Two-dimensional (2D) graphene nanosheets as advanced lubricant additives: A critical review and prospect. Mater. Today Comm.. 2021;29:102755

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A novel one-step chemical method for preparation of copper nanofluids. J. Colloid & Interface Sci.. 2004;277(1):100-103.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A review on natural fiber bio-composites, surface modifications and applications. Molecules. 2021;26(2)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coal as a filler in polymer composites: A review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling. 2021;174:105756.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]