Methylene Blue biodecolorization and biodegradation by immobilized mixed cultures of Trichoderma viride and Ralstonia pickettii into SA-PVA-Bentonite matrix

⁎Corresponding authors. adi_setyo@chem.its.ac.id (Adi Setyo Purnomo),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

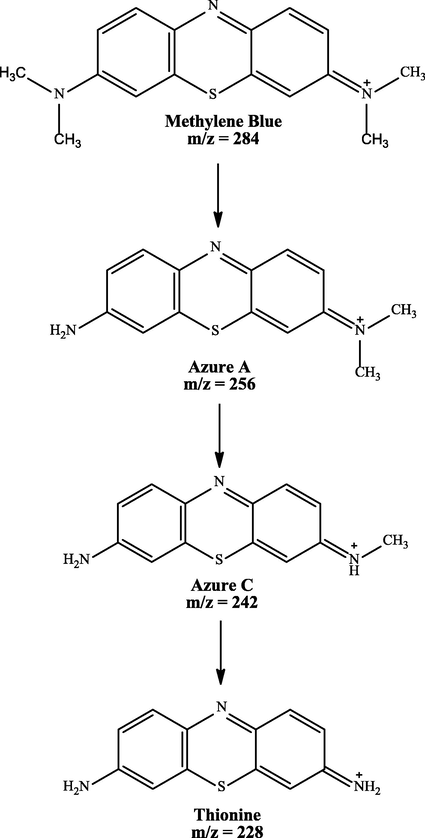

The problem of industrial dye wastewater poses a critical environmental challenge that demands urgent attention. This is because the direct release of synthetic dyes such as Methylene Blue (MB) into water bodies has been found to have adverse effects on the environment. Therefore, this study aimed to propose immobilization of a mixed Trichoderma viride and Ralstonia pickettii culture into Sodium alginate–Polyvinyl Alcohol-Bentonite (SA-PVA-Bentonite) matrix as a development method for MB decolorization and degradation. Immobilization process was carried out using the entrapment method, where bacteria and fungi cells were homogenized into the SA-PVA-Bentonite matrix. The results showed that immobilized culture (IMO Mix) outperformed the free cells in Mineral Salt Medium (MSM), achieving an impressive 97.88% decolorization rate for 48 h at 30 °C. Furthermore, a total of 3 metabolite product degradation were produced including Azure A and C, as well as Thionine by LCMS analysis. SEM-EDX analysis confirmed that culture was agglomerated within the SA-PVA-Bentonite matrix, while FTIR demonstrated the functional groups of the synthesized beads. Meanwhile, the difference in charge of bentonite facilitated the adsorption of MB onto the beads, and mixed culture supported the degradation process. This study presented a potential solution to environmental problems, particularly those related to the industrial sector. Further analysis was required to address the challenges associated with other industrial dye waste.

Keywords

Methylene Blue

Biodecolorization

Ralstonia pickettii

Trichoderma viride

Immobilization

Pollution

- FC RP

-

Free cell R. pickettii

- FC TV

-

Free cell T. viride

- FC Mix

-

Free cell mixed culture of R. pickettii and T. viride

- SA-PVA-Bentonite

-

Sodium Alginate-Polyvinyl Alcohol-Bentonite

- IMO TV

-

Immobilized T. viride

- IMO RP

-

Immobilized R. pickettii

- IMO Mix

-

Immobilized mixed culture of R. pickettii and T. viride

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Water is one of the most crucial components required for the sustenance of living organisms but human activities have led to a decline in the quality, primarily due to industrial activities (Bommavaram et al., 2020). The textile and paper industries are among the major contributors to water pollution, mainly due to their dyeing processes. About 15–30% of the dyes used during the manufacturing process result in wastewater and a decrease in water quality (Alkas et al., 2022; Tunç et al., 2009). Meanwhile, water bodies contaminated with high concentrations of synthetic dyes can lead to the mortality of aquatic organisms. The stable properties of dye wastewater are well-known to limit sunlight penetration, thereby reducing the rate of photosynthesis and causing a decline in the levels of dissolved oxygen (Lellis et al., 2019; Sharifi et al., 2022). The potential health risks associated with the intake of dye-contaminated water in high concentrations include allergies, cancer, and genetic mutations (Lellis et al., 2019).

MB is one of the cationic dyes commonly utilized in the textile and paper coloring industries, and the stable properties make it difficult to degrade naturally (Baguley et al., 2016; Moradi et al., 2021). Several methods such as adsorption, membrane filtration, photo-catalyst oxidation, Non-Thermal Plasma (NTP) catalysis, and coagulation have been developed for the dye waste treatment process (Ahmadzadeh et al., 2015; Dhiman et al., 2022; Liang et al., 2021; Robati et al., 2016). However, these methods are considered less effective due to the large residues produced during the process and the expensive reagent (Azam et al., 2020; Rizqi and Purnomo, 2017a). Adsorption is a simple and effective method that utilizes an adsorbent to remove dye and can degrade inorganic and organic compounds to become less toxic (Agarwal et al., 2016; Mahmood et al., 2022; Rajabi et al., 2016). Considering these factors, biodegradation is considered to be an efficient method for dye waste treatment as it is affordable and more environmentally friendly, utilizing bacteria or fungi to handle the waste (Cheng et al., 2012; Purnomo and Singh, 2017).

Fungi are one type of degrading agent more tolerant to pollutants than bacteria (Evans and Hedger, 2001). Furthermore, Trichoderma viride is a filamentous fungi with great potential in degrading pollutants. Lipsa et al. (2016) reported that T. viride can degrade polyester Polylactic Acid (PLA) and also adsorb heavy metal Pb(II) by forming a composite with Mica type phyllosilicate minerals such as muscovite, biotite, and phlogopite (Luo et al., 2021). This fungus showed great potential for MB biosorption by immobilizing within the Loofa sponge (Saeed et al., 2009). It produced a laccase enzyme that can degrade effluent dyes (Johnnie et al., 2021). Therefore, a modification of the development technique is required to effectively utilize these low-cost fungi agent.

The relationship between bacteria and fungi had been extensively studied since the 1960 s. Bacteria were reported to form a synergistic relationship with fungi in terms of wood decomposition process (Kamei et al., 2012). According to Clausen (1996), several metabolite products produced can increase the growth of fungi. The synergistic relationship increased the decolorization and degradation ability of MB by T. viride. Additionally, a bacteria used as a mixed culture with fungi is Ralstonia pickettii, due to its characteristics namely non-fermenting, gram-negative, aerobic, found in water and soil. It showed the ability to degrade aromatic compounds, such as benzene, cresol, phenol, and toluene (Ryan et al., 2007, 2006). Mahendra & Alvarez-Cohen (2006) reported that R. pickettii PK 01 degraded 50 mg/L 1,4 dioxane through a dioxane transformation process. In mixed culture, R. pickettii reportedly enhanced the ability of some fungi in the DDT degradation process (Purnomo et al., 2020, 2019).

The process of pollutant biodegradation can be carried out with the free cells method but has several shortcomings, such as the used cells being limited in operational stability, reusability, and transfer of substrates into the cells (Ha et al., 2009). Meanwhile, cell immobilization into a matrix is an effective technique for biodegradation, and entrapment is a technique used to trap cells in gels such as alginate, carrageenan, and Polyvinyl lcohol (PVA) (Rodríguez Couto, 2009). Sodium Alginate (SA) is a natural polymer used in immobilization process due to its non-toxic and environmentally friendly properties. However, it has low mechanical durability and the beads are easily destroyed (de-Bashan and Bashan, 2010). To overcome this problem, SA can be mixed with PVA which has non-toxic and good durability properties (Bialik-Wąs et al., 2021). PVA is a synthetic polymer and has a good mechanical strength property. A review study showed that polymeric adsorbents have great applicability under different environmental conditions, such as dye toxic environments (Moradi and Sharma, 2021). Even though the combination of SA-PVA is extensively employed as an immobilization matrix, further refinement is necessary to augment its efficacy (Aljar et al., 2021).

Mineral clay is one of the materials currently attracting significant attention due to its low price, large abundance, and surface area, as well as good adsorption properties. In addition, several studies showed that it is effective in removing cationic dyes due to its negative charge (Aljar et al., 2021; Hosseini et al., 2021). Bentonite is a type of clay mineral that is composed of Si tetrahedral and Al octahedral interconnected layers of hydroxyl groups. Moreover, it is negatively charged and is neutralized by exchangeable cations (Hebbar et al., 2014). Oussalah & Boukerroui (2020) stated that bentonite has a strong affinity for MB dye, hence, the addition into the SA-PVA matrix can increase the adsorption ability and mechanical durability.

Based on the description above, this study was conducted to investigate the effect of R. pickettii and T. viride addition into the SA-PVA-Bentonite matrix on MB degradation and decolorization. Immobilization process improved its ability in MB decolorization process, by comparing within free cell treatment only. The study was also enhanced by the addition of bentonite that supported MB adsorption toward beads. Furthermore, T. viride and R. pickettii had the ability for degrading dye pollutants in sterile conditions, within 48 h of incubation time. Fourier Transform Infra-red (FTIR) and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) characterizations were conducted to investigate the functional group and the morphological visual. Furthermore, the metabolite products that were produced and the biodegradation pathway used by immobilized mixed culture (IMO Mix) were also proposed.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

The materials used include filamentous fungi T. viride and bacterium R. pickettii obtained from Microorganism Chemistry Laboratory of Chemistry Department ITS, Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA, Himedia), Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB, Himedia), Nutrient Agar (NA, Merck), Luria Bertani Broth (LB, Merck), Aqua Demineralization (Aqua DM), 70% Alcohol (SAP Chemical), Bentonite, SA microbiology grade (Himedia), PVA with mass weight 60,000 (PVA, Merck), Glucose (Merck), NH4NO3 (SAP Chemical), K2HPO4 (SAP Chemical), MgSO4·7H2O (SAP Chemical), KH2PO4 (SAP Chemical), and FeSO4·7H2O (SAP Chemical).

2.2 Culture condition

The bacterium culture of R. pickettii was inoculated on NA medium and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Meanwhile, the regenerated culture was taken with an ose needle and inoculated into 20 mL of LB medium. Bacteria inoculum was then activated in a shaker incubator for 24 h at 35 °C, and culture with OD 1 was placed into 180 mL of LB media. Subsequently, the bacterium culture was pre-incubated in a shaker incubator for 48 h at 35 °C (Sariwati et al., 2017; Wahyuni et al., 2017).

Culture of filamentous fungi T. viride was inoculated on PDA medium and incubated for 7 days at 30 °C (Pan et al., 2023). The regenerated fungus was then homogenized with 25 mL of sterile aqua DM. About 1 mL of the homogenate was inoculated into 9 mL of PDB medium, while the inoculum was pre-incubated for 7 days at 30 °C (Rizqi and Purnomo, 2017b).

2.3 Immobilization of mixed culture T. viride and R. pickettii

Immobilization process started with the synthesis of the SA-PVA-Bentonite matrix with a composition of 1:4:1 (%w/v), and the pre-incubated T. viride mycelium and R. pickettii cells were added to the hydrogel matrix, and homogenized. Furthermore, hydrogel IMO Mix was dropped into a 0.4 M CaCl2 followed by constant stirring. The IMO Mix beads formed were immersed in a CaCl2 solution for 24 h, and washed with sterile Aqua DM (Kurade et al., 2019; Oussalah and Boukerroui, 2020; Ramsay et al., 2005).

2.4 Beads characterization

The morphology of the beads produced was characterized through SEM-EDX characterization. Before the process, the beads were dried using a freeze dryer, and placed in the sample holder coated with gold powder (coating stage). Subsequently, the sample was placed into a vacuum chamber and analyzed using SEM.

FTIR characterization was carried out to identified the functional group of the SA-PVA-Bentonite and IMO Mix beads. FTIR analysis also obtained the functional groups on the IMO Mix beads before and after the decolorization process. Before the characterization process, the beads were dried using a freeze dryer and were ground with the addition of KBr. Furthermore, mixture was placed in a mold and hydraulically pressed to form a pellet in the sample holder for FTIR analysis.

2.5 MB biodecolorization test

IMO Mix beads were added into 100 mL of 50 mg/L MB solution in MSM + glucose medium. MB solution containing immobilized beads was then statically incubated for 48 h at 35 °C, pH 5.5. In addition, the decolorized solution was separated from the beads using the decantation method, and MB filtrate obtained was analyzed with the UV–Vis spectrophotometer. As a comparison, the decolorization process was also performed by SA-PVA-Bentonite beads, free cells of R. pickettii, T. viride, and mix of them (FC RP, FC TV, and FC Mix, respectively), as well as immobilized cells of R. pickettii and T. viride (IMO RP and IMO TV, respectively). The calculation of MB removal percentage follows Equation (1), where [A]k is the initial concentration and [A]t is the final concentration of MB treatment.

Some of the filtrate obtained from the decolorization process was also analyzed by Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectroscopy (LCMS). The elution method used was the gradient with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min and 0.4 mL/min in the first three and for the next seven minutes. The mobile phase employed was water and methanol with a ratio of 1:99 for the first three minutes and 39:66 for the remaining seven minutes. Additionally, the column used was an Acclaim TM RSLC 120 C18 type with a size of 2.1 × 100 mm and the temperature was 33 °C. In this study, the kinetics and isothermal adsorption of IMO Mix beads were also examined. The kinetic models used pseudo-first and pseudo-second order, while the adsorption kinetics were analyzed according to Langmuir and Freundlich isotherms.

3 Result and discussion

3.1 Mixed culture of T. viride and R. pickettii immobilization

Mixed culture of T. viride and R. pickettii was immobilized in the SA-PVA-Bentonite matrix for the biosorption and biodegradation processes. The two microbes produce enzymes needed in MB degradation process (Johnnie et al., 2021; Nabilah et al., 2022). In addition, immobilization process was carried out to increase the resistance of the bacterium and fungi to extreme environmental conditions, facilitate their separation from the degraded filtrate, and enable their reuse in multiple cycles (Dzionek et al., 2016; Partovinia and Rasekh, 2018). The entrapment method was an irreversible immobilization technique, where the microbes were trapped by a matrix or a hollow particle. This method was often used because it had a large immobilization capacity, a simple, inexpensive, and efficient diffusion process (Trelles and Rivero, 2013).

SA was one type of natural matrix used in immobilization process. This matrix was environmentally friendly and non-toxic or biocompatible, but had low mechanical strength (de-Bashan and Bashan, 2010). In this study, SA was mixed with PVA to increase its mechanical strength. A proper crosslinking agent was important to form a suitable beads matrix (Lu et al., 2022). In the SA-PVA hydrogel system, alginate formed crosslinks with Ca2+ ions from CaCl2, while PVA formed hydrogen bonds with alginate molecular chains (Hua et al., 2010). However, SA-PVA had been reported to have limitations in the decolorization process due to its low adsorption capacity and selectivity (Aljar et al., 2021). To solve this problem, bentonite was added to the SA-PVA matrix to increase the adsorption capacity. Bentonite is a type of negatively charged clay mineral neutralized in the presence of Na+ ions or K+ ions. These cations were bound to the silicate and could be easily replaced with others through an ion exchange process (Hebbar et al., 2014). The presence of bentonite on matrix system was expected to increase the adsorption ability of MB dye.

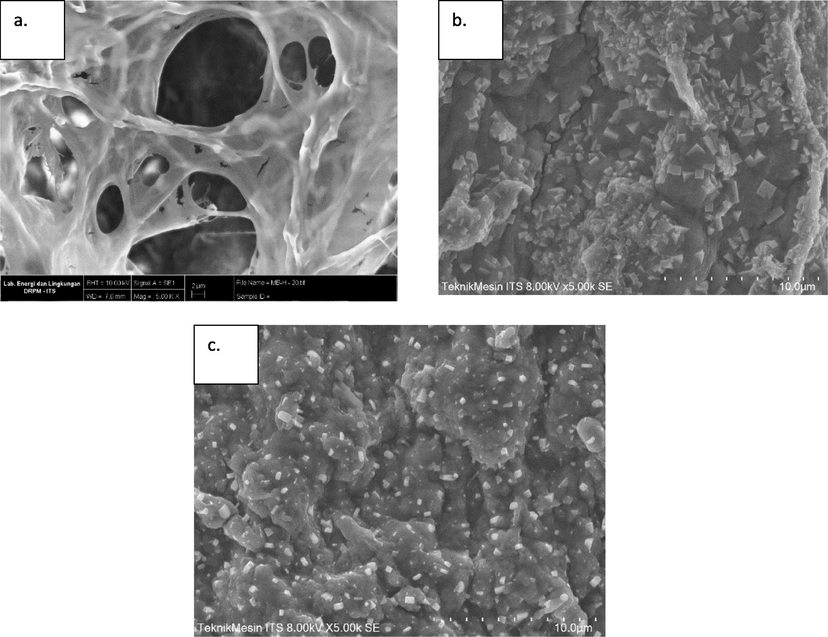

Morphological structure and elemental analysis of the SA-PVA-Bentonite and IMO Mix beads were carried out by SEM-EDX. Before the characterization process, the beads were dried using a freeze-dyer, and the morphological structures are shown in Fig. 1. As indicated in Fig. 1a, SA-PVA-Bentonite beads have a hollow structure with slightly rough walls. This was similar to the results reported by Baigorria et al. (2020) and Xu et al. (2020), where the hollow structure provided more sites, potentially increasing the adsorption ability of the beads. The morphological structure of IMO Mix beads in Fig. 1b showed that there were many small cubes attached to the surface of the beads. Fouad et al. (2011) reported that the cubes represented the morphological structure of PVA. In addition, bentonite dispersed into the SA-PVA hydrogel, culminating in a relatively rough surface (Aljar et al., 2021). T. viride and R. pickettii added into matrix were not visible because their mycelia were well mixed during the homogenization process.

- Morphological structure of a) cross-section SA-PVA-B beads and b) immobilized mixed culture before decolorization c) immobilized mixed culture after decolorization.

Table 2 showed the results of EDX analysis on SA-PVA-Bentonite and IMO Mix beads, where Fe and Mg elements were detected in bentonite structure (Hebbar et al., 2014). Additionally, elements K, S, P, and N were also detected on immobilized IMO Mix beads, indicating the presence of fungi and bacteria. Abostate et al. (2018) and Zyłkiewicz et al. (2019) reported that EDX analysis of MAM bacteria and Aspergillus sp. showed some peaks of elements C, O, P, S, Cl, and K.

| Sample | % Removal | Standard Deviation | Standard Error | Error Percentage (%) | Limit of Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FC RP | 38.2 | 0.48 | 0.28 | 27.76% | 8.26 |

| IMO RP | 96.81 | 0.42 | 0.24 | 24.49% | 7.29 |

| FC TV | 69.49 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 4.08% | 1.21 |

| IMO TV | 88.85 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 11.43% | 3.40 |

| FC Mix | 94.6 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 4.08% | 1.21 |

| IMO Mix | 97.88 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 6.53% | 1.94 |

| SA-PVA-Bentonite | 78.98 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 15.51% | 4.61 |

| Elements | Weight Percentage (Wt%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| SA-PVA-Bentonite | IMO Mix Before Decolorization | IMO Mix After Decolorization | |

| O | 54.26 | 36.78 | 35.73 |

| C | 33.65 | 0.83 | 1.65 |

| Ca | 6.20 | 18.76 | 14.70 |

| Cl | 5.28 | 18.78 | 6.20 |

| Si | 0.54 | 11.63 | 11.13 |

| Al | 0.08 | 5.12 | 5.05 |

| Na | 2.76 | 6.14 | |

| N | 1.55 | 3.92 | |

| Mg | 0.81 | 0.78 | |

| P | 0.48 | 6.30 | |

| S | 0.34 | 1.88 | |

| K | 0.60 | 2.42 | |

| Fe | 1.54 | 4.09 | |

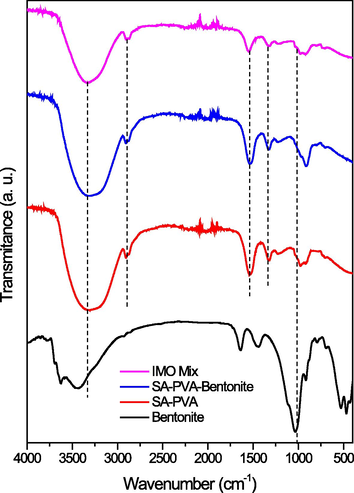

FTIR characterization was carried out to identify the functional groups formed on the beads. Fig. 2 provided clarification that SA-PVA-Bentonite and IMO Mix beads were constructed using SA, PVA, and bentonite. As evidenced in Fig. 2, the SA-PVA-Bentonite and IMO Mix synthesized before the bead formation exhibited a broad peak at 3,344 cm−1, indicating the overlapping-OH stretching of SA, PVA, and bentonite (Baigorria et al., 2020). Furthermore, the appearance of peaks at 1,624, 1,423, and 2,946 cm−1 represented asymmetric and symmetrical –COO as well as –CH stretching from alginate and PVA, respectively (Aljar et al., 2021). The shift of peaks at wave numbers 1,400 cm−1 was related to the presence of hydrogen bonds between the OH groups of PVA and alginate, or alginate and bentonite (Baigorria et al., 2020; Gonzalez et al., 2016). The SiO asymmetric and symmetrical from Si-O-Si of bentonite were represented by 1056 and 784 cm−1 (Baigorria et al., 2020; Belhouchat et al., 2017; Oussalah and Boukerroui, 2020). Therefore, it proved that IMO Mix and SA-PVA-Bentonite beads were consisted of SA, PVA, and bentonite.

- FTIR spectra.

A study showed that there was no significant difference observed in the FTIR analysis of T. viride before and after being loaded with MB (Saeed et al., 2009). The functional groups in the sample included OH, which overlapped with the amine functional group at 3368 cm−1, as well as the carboxyl group and –NH group, represented by peaks at 1654 and 1240 cm−1, respectively. Additionally, FTIR analysis of bacteria provided information about the biomolecules present in the sample. Naumann et al. (1991) classified five spectral windows due to the absorption expressed in lipid (3000–2800 cm−1), protein and peptides (1800–1500 cm−1), mixed region (1500–1200 cm−1, for protein, fatty acid, and phosphate-carrying compounds), Polysaccharides (1200–900 cm−1), and fingerprint region (900–700 cm−1). Therefore, bacteria spectra showed OH, CH, amide, COO–, C-O-C, and C-O (Novais et al., 2019).

3.2 MB biodecolorization

MB biodecolorization process by IMO Mix beads was performed by adding 40 g beads to 50 mg/L MB solution. The process was carried out in MSM with the addition of 0.5% (w/v) glucose. The medium used for the decolorization process was MSM, primarily due to its high mineral salt content, which is crucial for the growth and metabolism of microorganisms. Additionally, MSM is a low-carbon medium, resulting in the microorganisms being compelled to rely on supplementary carbon sources. The introduction of 0.5% glucose (w/v) into the medium served as a starter to facilitate the rapid acclimatization of the microorganisms to their new environment (Sekar and Mahadevan, 2011). MB biodecolorization process was conducted within 48 h, then the decolorized solution was measured with the UV–Vis spectrophotometer.

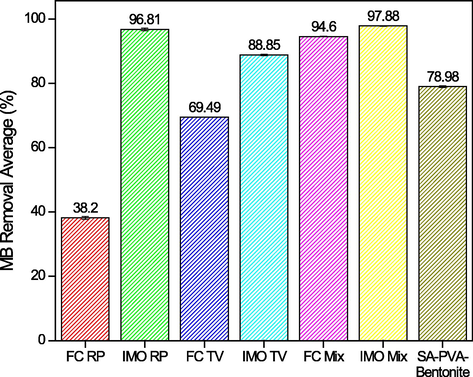

The comparison results of MB decolorization by IMO Mix beads and the other several decolorizing agents are shown in Fig. 3 within their analysis calculation that is shown at Table 1. The overall immobilized microorganisms in the SA-PVA-Bentonite matrix caused a higher MB percent removal compared to the free cell due to the adsorption process mechanism by matrix. Additionally, the adsorption process occurred due to electrostatic interaction between the positive charge on the iminium group (=N+) of MB and the negative charge (–COO, -SiO-) in matrix (SA, PVA, and bentonite) (Aljar et al., 2021; Belhouchat et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2021).

- MB removal percentage.

Fig. 3 showed that the presence of R. pickettiii bacterium in mixed culture enhanced the ability of T. viride to decolorize MB. This was indicated by the increase in MB removal percentage with both free and immobilized cells. R. pickettii had been reported to enhance some ability of fungi in the pollutant degradation process. According to Nabilah et al. (2022), mixed culture decolorized MB up to 89%, while the use of Daedalea dickinsii independently caused only 17% decolorization. Based on Fig. 3, IMO Mix beads had the highest MB removal percentage of 97.88% among the samples tested. Even though the result did not show a significant difference with MB percentage removal of IMO RP, the metabolites product of mixed culture tends to be simpler. This was because the enzymes produced by mixed culture were more varied than the individual culture. Each culture in mixed sample would mutually degrade the intermediate compounds produced in the degradation process of the pollutant (Mawad et al., 2020; Zhang and Zhang, 2022).

MB was attracted by electrostatic interaction and hydrogen bonds toward the beads. The synthesized beads had a negatively charged condition due to the addition of bentonite (Ravi and Pandey, 2019). Bentonite exhibited an OH surface interaction and was capable of cation exchange, leading to its negatively charged state (Lin et al., 2014). Consequently, beads under the category of cationic dye, such as MB, interacted with the beads. In addition, the presence of SA, PVA, bentonite, and MB was supported by the occurrence of hydrogen bonds, as stated by Bialik-Wąs et al. (2021) and Ravi & Pandey (2019). The hydrogen bond arose from the interaction between electronegative atoms, such as F, O, N, and hydrogen.

MB biodecolorization process by IMO Mix was supported by SEM-EDX and FTIR characterization. Fig. 1c showed the morphological structure of IMO Mix beads after the decolorization process. Based on the results, immobilized beads after decolorization had a rougher morphological structure compared to before decolorization, as shown in Fig. 1b. This result was consistent with Ravi & Pandey (2019), where alginate-bentonite beads tend to have rougher morphological structures after MB adsorption process. EDX analysis results of IMO Mix beads after decolorization are shown in Table 2, and the increase in the wt% of C, N, and S indicated the presence of MB adsorbed by immobilized beads. Meanwhile, the decrease in wt% of Ca implied the involvement of Ca2+ ions in the ion exchange process during MB adsorption.

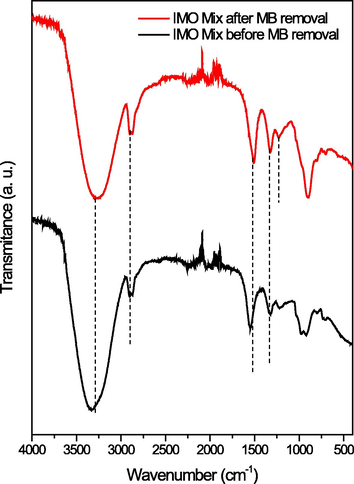

Fig. 4 showed the FTIR spectra of IMO Mix beads before and after decolorization, the shifting peak of –OH stretching from 3358 cm−1 to 3291 cm−1 on the beads after decolorization indicated the involvement of hydrogen bonds between bentonite in the beads and MB. A shift in the wave number of 1636 cm−1 to 1600 cm−1 indicated the presence of the C = C group (Ravi and Pandey, 2019), while the appearance of a peak at 1332 cm−1 indicated the presence of C-N vibration of MB (Liu et al., 2020). These results supported the assumption that there was an interaction between the beads and MB.

- FTIR spectra of immobilized mixed culture before and after decolorization.

3.3 Metabolite product identification

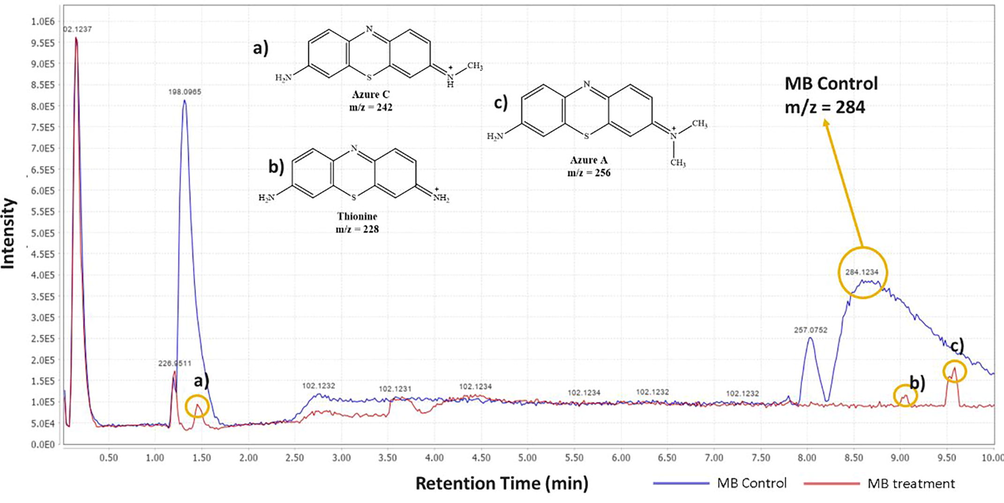

Metabolite products analysis of MB biodegradation product was carried out using LCMS. The instrument was a combination of HPLC and MS, where HPLC played a role in chromatographic separation and produces chromatograms, while MS provided m/z data of detected compounds (Winefordner, 2009). Fig. 5 showed the chromatogram comparison of MB treatment after decolorization and control (MB before decolorization).

- The chromatogram comparison of MB control treatment.

MB peak was found at a retention time (tR) of 8.50 in the treatment and control chromatogram. However, the intensity of peaks in the treatment chromatogram was significantly lower than in the control. This result proved the occurrence of MB degradation process by IMO Mix beads and also supported the previous analysis data by UV–Vis (Cohen et al., 2019). Fig. 5 showed that there were three new peaks in the treatment chromatogram at retention times of 1.47, 9.03, and 9.58, respectively. The three peaks obtained were identified as Azure C (m/z = 242), Thionine (m/z = 228), and Azure A (m/z = 256) (Hisaindee et al., 2013; Kishor et al., 2021; Rauf et al., 2010). In general, the product metabolites of MB biodegradation process are shown in Table 3.

| Retention Time (tR) | m/z | Metabolite Product | Molecular Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.47 | 242 | Azur e C |

|

| 9.03 | 228 | Thionine |

|

| 9.58 | 255 | Azure A |

|

The metabolites produced by several microorganisms showed different results depending on the enzymes released by the microbes. However, some microbes exhibited similar product metabolites. Phanerochaete chrysporium and Bacillus albus MW507057 were also reported to degrade MB using the lignin peroxidase (LiP) enzyme through the demethylation reaction. The biodegradation by these two microorganisms produced Azure A and Thionine as metabolite products (Ferreira et al., 2000; Kishor et al., 2021). Based on the identification performed, MB degradation pathway by immobilized mixed culture of T. viride and R. pickettii involving the demethylase enzyme was proposed, as illustrated in Fig. 6. The degradation pathway began with oxidative demethylation from MB to Azure A and then to Azure C. Subsequently, Azure C was subjected to further demethylation reactions to produce product metabolites of Thionine (Ferreira et al., 2000; Kishor et al., 2021; Purnomo et al., 2010).

- Proposed MB degradation pathway by immobilized mixed culture of T. viride and R. pickettii.

3.4 Adsorption kinetics and isotherms studies

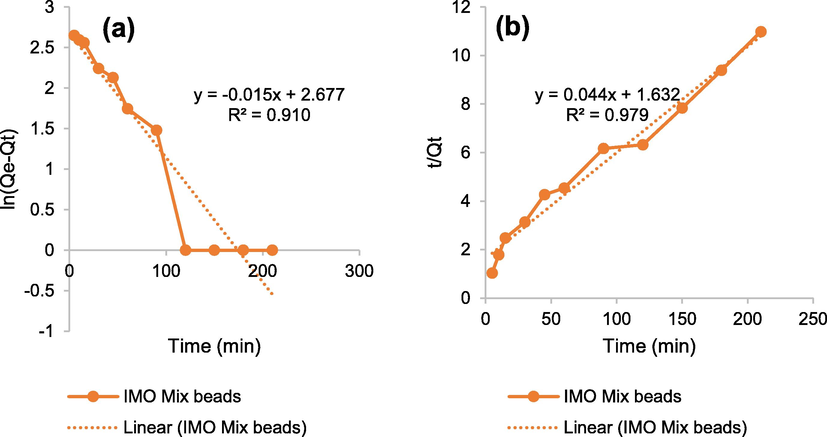

Adsorption kinetics should be analyzed to determine the adsorption rate and equilibrium capacity on the active site and surface area of the adsorbent (Das et al., 2021). In addition, this adsorption kinetics model depended on the physicochemical conditions of the adsorbent. Kinetic studies explain how quickly contaminants were adsorbed on the surface of the adsorbent (Moradi and Daneshmand Sharabaf, 2022). In this study, two models of adsorption kinetics were used to evaluate the kinetics adsorption of IMO Mix beads. It was namely pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second order models which shown by Eq (2) and (3):

Correlation/regression coefficients value (R2) close to 1 was obtained in pseudo-second order (Fig. 7). Meanwhile, R2 of the pseudo-second-order was greater than the pseudo-first-order. Table 4 showed that the regression value and calculated qe were determined to be 0.979 and 22.883 mg/g. The application of the pseudo-second-order kinetic model was based on the concept of chemisorption, where the rate of adsorption was dependent on the capacity (Das et al., 2021).

- Graphic of (a) pseudo-first and (b) pseudo-second order kinetic models.

| Pseudo-first order | Pseudo-second order | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | Slope | Intercept | K1 | qe cal | R2 | Slope | Intercept | K2 | qe cal |

| 0.910 | −0.015 | 2.677 | 0.015 | 0.985 | 0.979 | 0.044 | 1.632 | 0.001 | 22.883 |

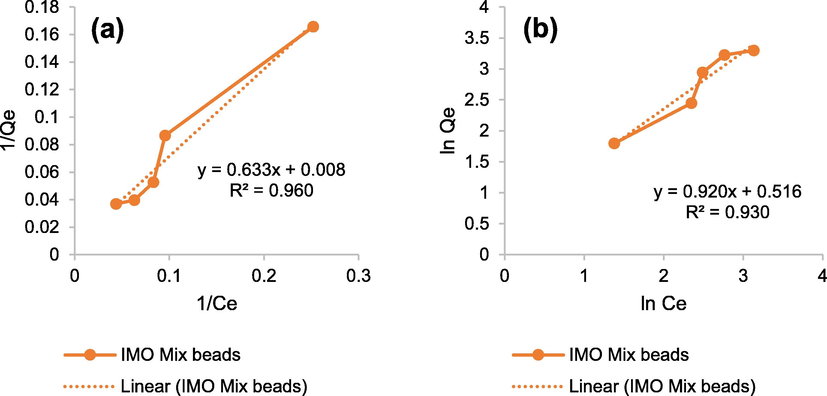

Adsorption isotherms showed the distribution of adsorbate molecules between the solid and liquid phases in solution at equilibrium. Furthermore, it indicated the amount of adsorption as a function of concentration at a constant temperature (Moradi et al., 2022), and the adsorption isotherms used Langmuir and Freundlich models. According to the Langmuir model, the distribution of the adsorbate was in the form of monolayer adsorption on the active site surface of the adsorbent. Meanwhile, the Freundlich model suggested that the adsorption occurred in multiple layers, known as multilayer adsorption (Freundlich and Heller, 1939; Langmuir, 1918). Langmuir and Freundlich model equations can be calculated by using the following equations (4) and (5), respectively:

Fig. 8 and Table 5 found that the R2 of Langmuir isotherm value was close to 1 compared to Freundlich isotherm, and the regression was approximately 0.960. It showed the adsorption distribution of MB in IMO Mix beads occurred in monolayer adsorption. In addition, the maximum adsorption capacity of the beads was also obtained as 120.482 mg/g.

- Graphic of (a) Langmuir and (b) Freundlich adsorption isotherms.

| Langmuir isotherm | Freundlich isotherm | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | Slope | Intercept | KL | qm | R2 | Slope | Intercept | KF | n |

| 0.960 | 0.633 | 0.008 | 0.013 | 120.482 | 0.930 | 0.920 | 0.516 | 3.279 | 1.087 |

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, the synthesis of T. viride and R. pickettii mixed culture immobilized on the SA-PVA-Bentonite matrix (IMO Mix) was successfully performed. The beads produced were then used in MB biodecolorization and biodegradation processes. The results showed that IMO Mix beads decolorized MB up to 97.88% after 48 h incubation period. The metabolites that were produced from the biodegradation process consisted of Azure A and C, as well as Thionine. Those results showed a potential solution for MB removal and environment problem. Further analysis was required to test IMO Mix ability with other industrial dye waste.

Author contributions

BN and AAR investigated the experiment. ASP and DP conceptualized, supervised, and validated the experiment. BN, ASP, DP, and AAR wrote the original draft, as well as reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Directorate of Research, Technology, and Community Service, Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology of Indonesia under the Student Thesis Research Scheme 2022, Number: 084/E5/PG.02.00.PT/2022 with Researcher Contract Number: 1434/PKS/ITS/2022, for funding this study.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Characterization, kinetics and thermodynamics of biosynthesized uranium nanoparticles (UNPs) Artif. Cells, Nanomed., Biotechnol.. 2018;46:147-159.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characteristics of polyaniline/zirconium oxide conductive nanocomposite for dye adsorption application. J. Mol. Liq.. 2016;218:494-498.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cesium selective polymeric membrane sensor based on p-isopropylcalix[6]arene and its application in environmental samples. RSC Adv.. 2015;5:39209-39217.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Environmentally friendly Polyvi nyl alcohol − alginate / bentonite nanocomposite hydrogel beads as efficient adsorbents for removal of toxic Methylene Blue from aqueous solution. Polymers (Basel). 2021;13:4000.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrication of metal-organic framework Universitetet i Oslo-66 (UiO-66) and brown-rot fungus Gloeophyllum trabeum biocomposite (UiO-66 @ GT) and its application for reactive black 5 decolorization. Arab. J. Chem.. 2022;15:104129

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Development of recoverable magnetic mesoporous carbon adsorbent for removal of methyl blue and methyl orange from wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2020;8:104220

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Some Drugs and Herbal Product : IARC Monographs on The Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Lyon: International Agency fro Research on Cancer; 2016.

- Bentonite-composite polyvinyl alcohol/alginate hydrogel beads: preparation, characterization and their use as arsenic removal devices. Environ. Nanotechnol., Monit. Manag.. 2020;14:100364

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Removal of anionic and cationic dyes from aqueous solution with activated organo-bentonite/sodium alginate encapsulated beads. Appl. Clay Sci.. 2017;135:9-15.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of the type of crosslinking agents on the properties of modified sodium alginate/poly(Vinyl alcohol) hydrogels. Molecules. 2021;26:7-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tea residue as a bio - sorbent for the treatment of textile industry effluents. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2020;17:3351-3364.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biodegradation of crystal violet using Burkholderia vietnamiensis C09V immobilized on PVA-sodium alginate-kaolin gel beads. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.. 2012;83:108-114.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial associations with decaying wood: a review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad.. 1996;37:101-107.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tracking the degradation pathway of three model aqueous pollutants in a heterogeneous Fenton process. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2019;7:102987

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Calcium alginate–bentonite/activated biochar composite beads for removal of dye and Biodegradation of dye-loaded composite after use: synthesis, removal, mathematical modeling and biodegradation kinetics. Environ. Technol. Innov.. 2021;24:101955

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- de-Bashan, L.E., Bashan, Y., 2010. Immobilized microalgae for removing pollutants: Review of practical aspects. Bioresour. Technol. 101, 1611–1627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biortech.2009.09.043

- Dhiman, P., Goyal, D., Rana, G., Kumar, A., Sharma, G., Linxin, Kumar, G., 2022. Recent advances on carbon-based nanomaterials supported single-atom photo-catalysts for waste water remediation, Journal of Nanostructure in Chemistry. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40097-022-00511-3.

- Natural carriers in bioremediation: a review. Electron. J. Biotechnol.. 2016;23:28-36.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Degradation of Plant Cell Wall Polymers. In: Gadd G.M., ed. Fungi in Bioremediation. Cambridge University Press; 2001. p. :1-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, V.S., Magalhães, D.B., Kling, S.H., Da Silva Jr., J.G., Bon, E.P.S., 2000. N-Demethylation of Methylene Blue by Lignin Peroxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 84–86, 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1385/ABAB:84-86:1-9:255

- The use of spray-drying to enhance celecoxib solubility. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm.. 2011;37:1463-1472.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The adsorption of cis-and trans-azobenzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 1939;61:2228-2230.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and characterization of poly (vinylalcohol) / bentonite hydrogels for potential wound dressings. Adv. Mater. Lett.. 2016;7:100-150.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biodegradation of coumaphos, chlorferon, and diethylthiophosphate using bacteria immobilized in Ca-alginate gel beads. Bioresour. Technol.. 2009;100:1138-1142.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and evaluation of heavy metal rejection properties of polyetherimide/porous activated bentonite clay nanocomposite membrane. RSC Adv.. 2014;4:47240-47248.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Application of LC-MS to the analysis of advanced oxidation process (AOP) degradation of dye products and reaction mechanisms. Trends Anal. Chem.. 2013;49:31-44.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green electrospun membranes based on chitosan / amino- functionalized nanoclay composite fibers for cationic dye removal : synthesis and kinetic studies. ACS Omega. 2021;6:10816-10827.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- pH-sensitive sodium alginate/poly(vinyl alcohol) hydrogel beads prepared by combined Ca2+ crosslinking and freeze-thawing cycles for controlled release of diclofenac sodium. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2010;46:517-523.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bio efficacy assay of laccase isolated and characterized from trichoderma viride in biodegradation of low density polyethylene (LDPE) and textile industrial effluent dyes. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol.. 2021;15:410-420.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coexisting Curtobacterium bacterium promotes growth of white-rot fungus Stereum sp. Curr. Microbiol.. 2012;64:173-178.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Efficient degradation and detoxification of methylene blue dye by a newly isolated ligninolytic enzyme producing bacterium Bacillus albus MW407057. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2021;206:111947

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Decolorization of textile industry effluent using immobilized consortium cells in upflow fixed bed reactor. J. Clean. Prod.. 2019;213:884-891.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 1918;40:1361-1403.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of textile dyes on health and the environment and bioremediation potential of living organisms. Biotechnol. Res. Innov.. 2019;3:275-290.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Benzene decomposition by non-thermal plasma: a detailed mechanism study by synchrotron radiation photoionization mass spectrometry and theoretical calculations. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2021;420:126584

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biodegradation of naphthalene using a functional biomaterial based on immobilized Bacillus fusiformis (BFN) Biochem. Eng. J.. 2014;90:1-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biodegradation of poly(lactic acid) and some of its based systems with Trichoderma viride. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2016;88:515-526.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Targeted reclaiming cationic dyes from dyeing wastewater with a dithiocarbamate-functionalized material through selective adsorption and efficient desorption. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2020;579:766-777.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A 4arm-PEG macromolecule crosslinked chitosan hydrogels as antibacterial wound dressing. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2022;277:118871

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Trichoderma viride involvement in the sorption of Pb(II) on muscovite, biotite and phlogopite: batch and spectroscopic studies. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2021;401:123249

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kinetics of 1,4-dioxane biodegradation by monooxygenase-expressing bacteria. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2006;40:5435-5442.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of Ag@CdO nanocomposite and their application towards brilliant green dye degradation from wastewater. J. Nanostruct. Chem.. 2022;12:329-341.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Role of bacterial-fungal consortium for enhancement in the degradation of industrial dyes. Curr. Genomics. 2020;21:283-294.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Separation of organic contaminant (dye) using the modified porous metal-organic framework (MIL) Environ. Res.. 2022;214

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Emerging novel polymeric adsorbents for removing dyes from wastewater: a comprehensive review and comparison with other adsorbents. Environ. Res.. 2021;201:111534

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of GO/HEMA, GO/HEMA/TiO2, and GO/Fe3O4/HEMA as novel nanocomposites and their dye removal ability. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater.. 2021;4:1185-1204.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization Agar/GO/ZnO NPs nanocomposite for removal of methylene blue and methyl orange as azo dyes from food industrial effluents. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2022;169:113412

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of Ralstonia pickettii bacterium addition on methylene blue dye biodecolorization by brown-rot fungus Daedalea dickinsii. Heliyon. 2022;8:e08963.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microbiological characterizations by FT-IR spectroscopy. Nature. 1991;351:81-82.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy: unlocking fundamentals and prospects for bacterial strain typing. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.. 2019;38:427-448.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alginate-bentonite beads for efficient adsorption of Methylene Blue dye. Euro-Mediterranean J. Environ. Integr.. 2020;5:31.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory effect of cinnamaldehyde on Fusarium solani and its application in postharvest preservation of sweet potato. Food Chem.. 2023;408:135213

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Review of the immobilized microbial cell systems for bioremediation of petroleum hydrocarbons polluted environments. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2018;48:1-38.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microbe-Assisted Degradation of Aldrin and Dieldrin. In: Singh S., ed. Microbe-Induced Degradation of Pesticides. Environ. Eng. Sci. Cham: Springer; 2017.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Involvement of Fenton reaction in DDT degradation by brown-rot fungi. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad.. 2010;64:560-565.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ralstonia pickettii enhance the DDT biodegradation by Pleurotus eryngii. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2019;29:1424-1433.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic interaction of a Consortium of the brown-rot fungus Fomitopsis pinicola and the Bacterium Ralstonia pickettii for DDT biodegradation. Heliyon. 2020;6:e04027.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of malachite green from aqueous solution by carboxylate group functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes: determination of equilibrium and kinetics parameters. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.. 2016;34:130-138.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Decoloration of textile dyes by alginate-immobilized Trametes versicolor. Chemosphere. 2005;61:956-964.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Photocatalytic degradation of Methylene Blue using a mixed catalyst and product analysis by LC/MS. Chem. Eng. J.. 2010;157:373-378.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ravi, Pandey, L.M., 2019. Enhanced adsorption capacity of designed bentonite and alginate beads for the effective removal of methylene blue. Appl. Clay Sci. 169, 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clay.2018.12.019

- The ability of brown-rot fungus Daealea dickinsii to decolorize and transform Methylene Blue dye. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2017;33:92.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The ability of brown-rot fungus Daedalea dickinsii to decolorize and transform methylene blue dye. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2017;33:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Removal of hazardous dyes-BR 12 and methyl orange using graphene oxide as an adsorbent from aqueous phase. Chem. Eng. J.. 2016;284:687-697.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ralstonia pickettii: a persistent gram-negative nosocomial infectious organism. J. Hosp. Infect.. 2006;62:278-284.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ralstonia pickettii in environmental biotechnology: potential and applications. J. Appl. Microbiol.. 2007;103:754-764.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Immobilization of Trichoderma viride for enhanced methylene blue biosorption: batch and column studies. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2009;168:406-415.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Abilities of Co-cultures of brown-rot fungus Fomitopsis pinicola and Bacillus subtilis on biodegradation of DDT. Curr. Microbiol.. 2017;74:1068-1075.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermokinetic responses of the metabolic activity of Staphylococcus lentus cultivated in a glucose limited mineral salt medium. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.. 2011;104:149-155.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Density functional theory study of dyes removal from colored wastewater by a nano-composite of polysulfone/polyethylene glycol. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2022

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Whole Cell Entrapment Techniques BT - Immobilization of Enzymes and Cells (Third Edition). Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2013. p. :365-374.

- [CrossRef]

- Potential use of cotton plant wastes for the removal of Remazol Black B reactive dye. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of mannanase isolated from corncob waste bacteria. Asian J. Chem.. 2017;29(5):1119-1120.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liquid Chromatography Times of Mass Spectrometry. New Jersey: Wiley Inc Publication; 2009.

- Removal of phosphate from wastewater by modified bentonite entrapped in Ca-alginate beads. J. Environ. Manage.. 2020;260:110130

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T., Zhang, H., 2022. Microbial Consortia Are Needed to Degrade Soil Pollutants. Microorganisms 10, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fmicroorganisms10020261.

- MXene / sodium alginate gel beads for adsorption of Methylene Blue. Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2021;260:124123

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Removal of platinum and palladium from wastewater by means of biosorption on fungi Aspergillus sp. and yeast Saccharomyces sp. Water. 2019;11:1522.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]