Translate this page into:

General overview to understand the adsorption mechanism of textile dyes and heavy metals on the surface of different clay materials

⁎Corresponding author at: Laboratory of Applied Chemistry and Environment, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science Agadir, Ibnou Zohr University, Agadir, Morocco. mohamed.elhabacha@edu.uiz.ac.ma (Mohamed El-habacha) mohamedelhabacha@gmail.com (Mohamed El-habacha)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University. Production and hosting by Elsevier.

Abstract

Abstract

The clays' high efficiency favors the adsorption of toxic dyes and heavy metals. Different methods of modifying the surface functions of natural clays affect their adsorption capacities remarkably. Understanding the adsorption mechanism of emerging pollutants on the surface of clay materials is crucial. The economic and environmental benefits of clays, as well as their ability to regenerate, indicate that they could be industrially exploitable.

Abstract

The adsorption process is one of the most cost-effective methods for eliminating various types of pollutants from water. Clay minerals can be converted into biosorbents for environmental remediation. This literature review summarizes the different types of natural clays, their crystal structures, classifications, physical and chemical properties, and industrial applications. Also the main results of recent studies on the process and mechanism of adsorption on natural clay materials to eliminate heavy metals and highly emerging toxic dyes. The Langmuir and Freundlich models are the most commonly used isotherms in most previous studies. In addition, the adsorption kinetics of the majority of dyes and heavy metals using natural clays are based on the pseudo-second-order model. High adsorption capacities of 909.09 mg g−1 for synthetic dyes and 179 mg g−1 for heavy metals were observed. This review article suggests that clays can be modified by various methods to improve their adsorption efficiencies by increasing their specific surface areas. The clays' low cost and ability to regenerate show that these materials are environmentally friendly and beneficial for industrial ecology.

Keywords

Adsorption mechanism

Clays

Dyes

Heavy metals

Regeneration

Specific surface area

- SY

-

Sunset Yellow

- NB

-

Nile Blue

- MB

-

Methylene Blue

- BR46

-

Basic Red 46

- BFBN

-

Blue Functionalized Boron Nitride

- RFRN

-

Rose-FRN

- DR23

-

Direct Red 23

- BY28

-

Basic Yellow 28

- AB75

-

Acid Brown 75

- SLV

-

Sodium Leuco-Vat

- TC

-

Tetracycline

- CV

-

Crystal Violet

- TB

-

Toluidine Blue

- MV

-

Methyl Violet

- BD85

-

Direct Blue 85

- BV 16

-

Basic Violet 16

- RR 120

-

Reactive Red 120

- DO34

-

Direct Orange 34

- CR

-

Congo Red

- SAF

-

Safranin

- MO

-

Methyl Orange

- MR

-

Methyl Red

- MG

-

Malachite Green

- BG

-

Blue BG

- YL

-

Yellow 7 GLL

- BB9

-

Basic Blue 9

- BB41

-

Basic blue 41

- Ph

-

Phosphate

- OTC

-

Oxytetracycline

- OG

-

Orange G

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Nowadays, it is necessary to preserve water resources to save humanity and make its existence more secure (Thamarai Selvi and Zahir Hussain, 2022). Today, the greatest problem for the environment and ecosystems is water pollution, which is considered an indispensable element of all socio-economic activities, regardless of the degree of development of countries (Doltade et al., 2022). Increasing industrial activity is putting increasing pressure on the world's freshwater reserves (Miyah et al., 2017). Indeed, these activities generate a wide variety of chemicals that are discharged into the water cycle, endangering the fragile natural equilibrium that has allowed life to develop on Earth (Varol, 2020). The existence of these pollutants, even in small amounts, is very threatening, making humans, aquatic organisms, wildlife, and plants vulnerable to various diseases and even death (Miyah et al., 2021). In addition, it is reported that more than 3 billion people in the world live in areas where water is scarce (Diagboya et al., 2020). According to the report of the World Health Organization (WHO), about 844 million people in the world lack access to clean water (Sarkar et al., 2020). Due to limited economic resources or infrastructure, millions of poor people die each year from diseases caused by unsufficient and poor-quality water (Mohapi et al., 2020). Therefore, the absence or inadequacy of treatment systems leads to the non-biodegradable toxic chemicals' accumulation in the water cycle (Benjelloun et al., 2022). The main organic pollutants are pesticides, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, plasticizers, phenols, polybrominated diphenyl ethers, polychlorinated biphenyls, and drug residues, as well as synthetic dyes produced by the textile industry (Buruga et al., 2019). In addition, other very emerging inorganic contaminants are heavy metals such as arsenic, cadmium, cobalt, mercury, lead, chromium, and many other toxic metal ions including nitrates and phosphates. (Abdullahi et al., 2020; Aloulou et al., 2020; Nabbou et al., 2019; Benhiti et al., 2020). Organic textile dyes are responsible for the toxicity, odor, unpleasant taste, and coloration of the water, degrading water quality and causing the loss of aquatic life (Teo et al., 2022). This situation implies the need to treat colored effluents before they are discharged into the environment (Sriram et al., 2022). The textile industry is one of the industries responsible for high water consumption and generates effluents loaded with recalcitrant organic molecules that are difficult to treat by conventional water purification systems (Munjur et al., 2020). The world's production of dyes is estimated at more than tons per year (de Araújo et al., 2021; El-Gaayda et al., 2021). Furthermore, it is estimated that tons of textile dyes are released into the environment globally each year (de Araújo et al., 2021; El-Gaayda et al., 2021). All the dyes are toxic for their composition and modes of use (Ambika and Srilekha, 2021). They can cause skin diseases in humans and even skin cancers (Tiwari et al., 2022). Thus, the untreated effluents of these dyes are responsible, after their discharge, for the increasing accumulation of recalcitrant substances difficult to biodegrade in water (Tijani et al., 2021). Similarly, heavy metals have toxic effects on organisms when their concentrations exceed specified levels, which can cause various complications in plants and animals. In humans, they cause acute and chronic diseases, such as cancer, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, kidney dysfunction, osteoporosis, and heart failure (Rehman et al., 2021; Alengebawy et al., 2021). The situation is aggravated by the absence or insufficiency of an adequate water treatment system capable of reducing the concentration of toxic substances that present chronic chemical risks. (Eswaran et al., 2021). It can be said that poorly treated wastewater inevitably leads to a deterioration of the water sources quality and, consequently, to a lack of drinking water in many countries (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2021).

Several depollution processes have been developed to protect the environment and offer the possibility of reusing wastewater (Sellaoui et al., 2021). They are different from each other and can be cited as examples: adsorption on commercial activated carbon, electrolysis, flotation, chemical precipitation, ion exchange, membrane filtration (ultrafiltration, nanofiltration, and reverse osmosis), photocatalysis, chemical oxidation, etc (Benjelloun et al., 2021; Miyah et al., 2020; Znad et al., 2018; Iaich et al., 2021; Miyah et al., 2022). Most of these technologies are very expensive, especially when applied to high-throughput effluents (Melhaoui et al., 2021). In addition, some of these processes can produce by-products that are more toxic than the original products (Thotagamuge et al., 2021). The adsorption process is one of the most adopted techniques for the removal of contaminants of different natures, such as textile dyes and heavy metals (Saleem et al., 2019).

On the other hand, for low volume discharges, research was then directed towards less expensive and widely available treatment processes, using adsorbents namely clays, zeolites, fly ash, pyrophyllite, eggshells, snail shells, hydroxyapatite, metal oxides, and nanocomposite materials (Miyah et al., 2017); (Saleem et al., 2019; Fabryanty et al., 2017; Awual et al., 2019; Wei et al., 2021; Romdhane et al., 2020) However, most of these adsorbents are microparticles, and the small contact area requires considerable time to achieve maximum pollutant removal (Cao et al., 2020). As most industries need a fast removal rate to cope with increasing pollutant capacities, there is an urgent need to develop adsorbents that are durable, economical, and offer both high removal rates and high adsorption capacities (Yönten et al., 2020). With the latest trends in environmental sustainability, scientists are focusing on the use of low-cost natural materials to effectively remove harmful substances from wastewater (Miyah et al., 2021; Dabagh et al., 2022). Clay is a natural, non-toxic, abundant, durable, and high-surface area material used in the adsorption process (Jawad and Abdulhameed, 2020). Clay has long been used in crafts such as pottery and various ceramic products used in building construction, such as bricks and tiles (Antonelli et al., 2020). Due to its ability to exchange ions, swell and transform, clay has a wide range of uses in wastewater treatment, the paper industry, paint, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, and the ceramic industry (Sulyman et al., 2021; Luty-Błocho et al., 2021; Kubendiran et al., 2021). Since the rise of the oil refining and petrochemical industries, clay has been used as a catalyst (Vieira et al., 2022).

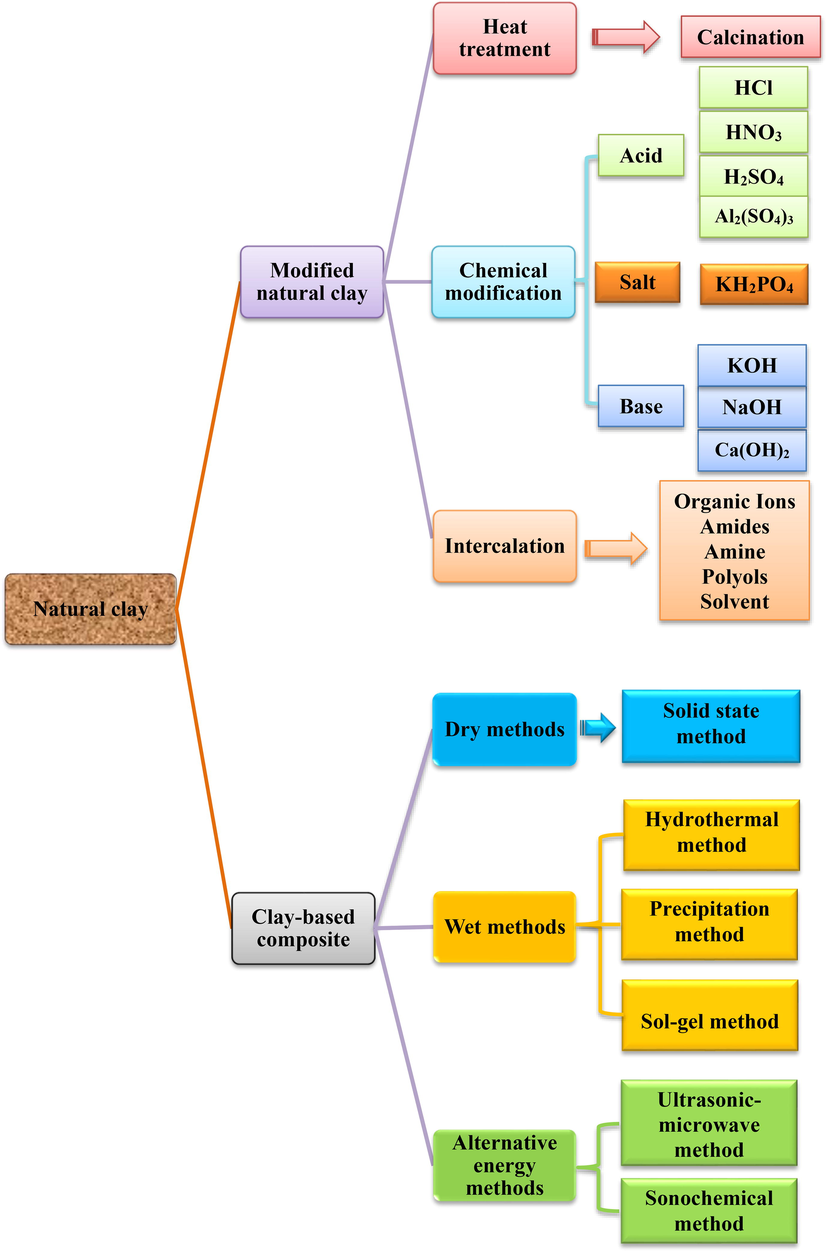

In addition, the clay can be modified to improve its efficiency and adsorption capacities using various treatments, such as thermal treatments (calcination), chemical treatments (acid and basic activation), cationic exchange, grafting of organic compounds (surfactant), or polymer activation, etc (Vieira et al., 2016; Hradil et al., 2020; Gamoudi and Srasra, 2018).

This literature review is devoted to recent research on the use of natural and modified clay materials as effective adsorbents for the treatment of polluted water and highlights the structure, classification, and physicochemical properties of clays and their use in the ceramic industry. In addition, we provide a general overview of the selectivity and sensitivity of interactions between different fillers to understand the adsorption mechanisms of textile dyes and heavy metals on the surface of raw clays or clays subjected to various treatments and modifications, while studying their beneficial effects on adsorption performance, regeneration capacity, cost analysis, and industrial scale applications.

2 Clay minerals: Structure and classification

2.1 Crystal structure of clay minerals

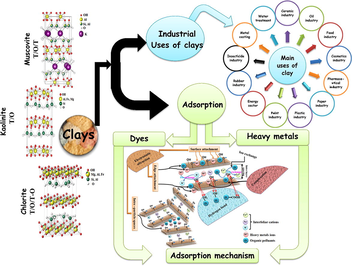

Clays consist of minerals whose particles are essentially lamellar phyllosilicates and stacks of silicate two-dimensional sheets. The lamellar crystal structure is based on two important entities (Fig. 1) (Orta et al., 2020).

-

The siliceous tetrahedral layers SiO4 (T) are arranged in a two-dimensional hexagonal lattice, in which a Si4+ cation is surrounded by four oxygen atoms as shown in Fig. 1a.

-

Alumina (Al), iron (Fe), or magnesium (Mg) octahedron layers are located in the center of the octahedron and are surrounded by six hydroxyl groups or oxygen atoms as shown in Fig. 1b.

- Schematic representation of various clay minerals: tetrahedral layer (a), octahedral layer (b), not charged (c), charged (d), T/O clay minerals (e.g. kaolinite) (e), clay minerals T/O/T example: muscovite (f), clay minerals T/O/T-O example: chlorite (g), projection on the (0 0 1) plane of the structure of fibrous minerals: Sepiolite (h) and Palygorskite (k).

The structural organization of phyllosilicates is based on a framework of oxygen and hydroxyl ions that occupy the tops of octahedral (O2-and OH–) and tetrahedral (O2–) assemblies. In the cavities of these elementary structural units, cations of variable sizes (Si4+, Al3+, Fe3+, Fe2+, Mg2+) are in tetrahedral or octahedral positions (Wal et al., 2021).

These elements are organized along a plane to form octahedral and tetrahedral layers, the number of which determines the thickness of the sheet. The space between two successive parallel sheets is called interlayer space (Fig. 1). This latter can be empty and the sheets are neutral and then linked directly to each other by hydrogen bonds, such as kaolinite (Fig. 1c), or by Van Der Waals bonds, such as talc or pyrophyllite (Lucas, 1962). Where filled by various cations, which can be either dry or hydrated, the most frequent are Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, Na+, and Li+, which form “bridges” from one sheet to the other (Fig. 1d) (Tchieno Melataguia, 2016; Zaid, 2020).

When two cavities out of three of the octahedral layer are occupied by Al3+ or by another trivalent metal ion, the structure is called di-octahedral. When all the octahedral cavities are occupied by bivalent metal ions, the structure is called tri-octahedral (Thiebault, 2020).

2.2 Classification of clays

There are different classifications of clay; the most classical is based on the structure and thickness of the sheet (Table 1). We distinguish three main groups:

Sheet types

Inter-reticular distance

(Å)

Interlayer

cations

Octahedral layer nature

The electrical charge of the sheet

Groups

Formulas

Mineral Species

TO

or

1/17

None or H2O

Dioctahedral

0

Kaolinite

Al2Si2O5(OH)4

Kaolinite, dickite,

nacrite, halloysite

Trioctahedral

Serpentine

(R2+)6Si4O10(OH)8

R2+=Mg2+, Fe2+, Mn2+or Ni2+

Chrysotile,

berthiérine,

amesite, antigorite,

lizardite

TOT

or

2/110

Non-hydrated

Dioctahedral

0,9 – 1,0

Micas

X2Y4-6Z8O20 (OH, F)4

Muscovite,

celadonite,

paragonite,

phengite

Trioctahedral

Phlogopite, annite,

biotite, lepidolite

Dioctahedral

2

Micas hard

Margarite,

chernykhite

Trioctahedral

Clintonite,

kinoshitslite

bityite, anandite

10 to 15

Hydrated and exchangeable

Dioctahedral

0,6 – 0,9

Vermiculite

(Si4)(Al4-pMgp)(Si4-q)O20(OH)4

Vermiculite Dioctaédrique

Trioctahedral

Vermiculite

Trioctaédrique

10 to 18

Hydrated and exchangeable

Dioctahedral

0,2 – 0,6

Smectites

(Al, Mg, Fe)4(Si, Al)8O20(OH)4

•X0.85nH2OMontmorillonite,

beidellite,

nontronite,

volkonskoite

Trioctahedral

(Mg6-zR3+z)(Si8-

yAly)O20(OH)4•XxnH2OSaponite, hectorite,

sauconite

9

None

Dioctahedral

0

Pyrophyllite

TalcAl4(Si8-xAlx)O20-x(OH)4+x

Pyrophyllite,

ferripyrophyllite

Trioctahedral

(Mg6-z-yFe 2+ Fe 3+y)(Si8- xFe3+x)O20+y-x(OH)4-y+x

Talc, willemseite,

kerolite, pimelite

TOT-O

or 2/1/114

In hydroxide form

Dioctahedral

Variable

Chlorites

[(R2+, R3+)6(Si, Al)8O20

(OH)4][

(R2+R3+)6(OH)12]Donbassite

Di, Trioctahedral

Cookeite, sudoite

Trioctahedral

Clinochlore,

pennantite,

chamosite, nimite

2/1In slats

(ribbons)10

Hydrated and exchangeable

Dioctahedral

Variable

Palygorskite

SepioliteSi8O20Mg5(OH)2(H2O)4·4H2O

Attapulgite

Trioctahedral

Si6Mg4O15(OH)26H2O

Sepiolite

Variable

Variable

Variable

Dioctahedral

Variable

Interstratified minerals

variable

Tosudite (smectite-chlorite)

Trioctahedral

Kulkeite

(chlorite-talc)

2.2.1 Phyllite minerals

Phyllite minerals, or phyllosilicates, are minerals of the group of silicates with sheet structures built by the stacking of tetrahedral layers (T) being connected to an octahedral layer (O) by common oxygen atoms or hydroxyl groups. The number of associations of these layers determines the thickness of their structural units, the interfoliar (interlayer space) charge, and the composition of interfoliar elements. The minerals of this type of structure can be classified into subgroups of the type T/O or 1/1, type T/O/T or 2/1, and type T/O/T-O or 2/1/1 (Olaremu, 2021; Han et al., 2019).

2.2.2 Minerals of type 1/1 or 1 T/1O

The sheet consists of a tetrahedral layer and an octahedral layer. The inter-reticular distance is about 7 Å (Fig. 1e). This type corresponds to the kaolinite group.

2.2.3 Minerals of type 2/1 or 2 T/1O

The current classification of clay minerals as 2/1 is based on their crystallochemical composition. Since Stokholm (AIPEA, 1963), the first criterion is a global resultant of this composition, expressed by the interfoliar charge, followed by the di or tri-octahedral character. The origin of the charge (tetrahedral or octahedral substitution), and even the nature of the cation saturating the charge K in micas (Robert and Agronomic Annals, 1975). In their classification project, Méring and Pédro (1969) even make use of finer characteristics, which are the order or the disorder in the isomorphic substitutions or the distribution of the compensating cations (Méring and Pédro, 1969).

The sheet consists of an octahedral layer sandwiched between two tetrahedral layers. The characteristic equidistance varies from 9.4 to 15 Å according to the content of the interleaf. Smectites, vermiculites, and micas are examples of this type (Michel, 1971). Muscovite is a mineral with this structure, belonging to the mica family (Fig. 1f).

2.2.4 Minerals of type 2/1/1 or (2 T/1O)1O

The clay minerals of type 2/1/1 (T/O/T-O) have a crystalline structure identical to the 2/1 except that the interfoliar space is not occupied by compensating cations as in the preceding case (Fig. 1f), but by an octahedral layer, of brucitic nature (Mg(OH)2) or gibbsitic (Al(OH)3) (Delavernhe, 2012). The characteristic equidistance is then about 14 Å. The chlorite groups correspond to this type (Fig. 1g).

2.2.5 Fibrous minerals

Fibrous minerals are characterized by discontinuous clayey sheets (Fig. 1). They are distinguished by their particular structure in pseudo-sheets constituted by continuous planes of oxygen atoms separated between them by two planes containing a compact assembly of oxygen atoms and hydroxyl groups. The stacking of the two discontinuous planes forms entangled octahedrons, creating a ribbon. It is the width of this ribbon that characterizes each family. The oxygens of the continuous plane form the base of the tetrahedron, whose point is constituted by the oxygen of the ribbon. These tetrahedra are occupied at their centers by Si4+ ions. Mg2+ or Al3+ ions occupy the octahedral gaps (Aoun, 2016). The ribbons are terminated by bonds between these cations and water molecules. We distinguish two main families among these fibrous minerals: the sepiolites, which correspond to a ribbon with 8 octahedrons and which comprise essentially Mg as an exchangeable cation, rarely Na (Fig. 1h), and the palygorskites (also called attapulgite) (Fig. 1k), which are constituted of a ribbon with 5 octahedrons and richer in Al than the sepiolite.

2.2.6 Inter-layered minerals

There are, of course, inter-stratified minerals, formed by the regular stacking [(2 T/1O)/ (2 T/1O)] or irregular [(1 T/1O)/ (2 T/1O)] of sheets of two different types. The most common is the case of illite–smectite (I/S), kaolinite-smectite (K/S), and chlorite-vermiculite (Ch/V) (Caner, 2011; Abidi, 2015).

Table 1 below gives the classification of the main groups of clay minerals (Wal et al., 2021; Tchieno Melataguia, 2016; Boucheta, 2017; Clauer, 2005).

2.2.7 Associated minerals

The clay minerals are linked to other non-phyllite compounds. The main ones are grouped in Table 2 (Tankpinou Kiki, 2016; Bouzidi, 2012).

Iron oxides and hydroxides

Feldspars

Carbonates

Quartz

Organic matter

Hematite (Fe2O3)

Magnetite (Fe3O4)

Goethite (FeOOH)Feldspar type

-Potassic (Si3AlO8)K

-Sodic (Si3AlO8)

-Calcic (Si2Al2O8)CaCalcite (CaCO3) Dolomite (Ca,Mg)(CO3)2

Magnesite (MgCO3)

Free silica

- Living components (microflora, roots, pedofauna)

- Plant and animal debris

- Molecular organic matter or humus: sugars, amino acids, fatty acids, alcohols, esters, etc.

-Humic substances: fulvic acid, humic acids, humin.

3 Physico-chemical properties of clays

Clay minerals are characterized by several properties that are related to their chemical composition, their structure and morphology, and also to the physical and chemical conditions in which they are found (Meziti, 2016). These properties can be physical or chemical, they are numerous and widely used for the characterization of clay minerals. The most fundamental important properties in the adsorption processes are the specific surface and the cationic exchange capacity (CEC) (Anouar et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021).

3.1 Clay surfaces charges

The majority of clay minerals are characterized mainly by a non-neutral electrical surface, which is due to both isomorphic substitutions and the environment, leading to two types of charges (Kouadri, 2018; Li et al., 2021).

-

A permanent negative charge on the surface is related to ion substitution in the sheet. This is because the metal cation is replaced by another low-valence metal (Al3+ by Si4+ in the tetrahedral layer, Mg2+ or Fe2+ by Al3+ in the octahedral layer). These substitutions lead to a charge deficit which is compensated for outside the sheet by compensating cations such as Li+, Na+, Ca2+, K+, or Mg2+.

-

A variable charge depends on the pH of the medium. It can be positive or negative and is located at the edge of the sheets. In an acidic medium, positively charged species predominate, while in a basic medium, negatively charged species predominate.

3.2 Specific surface area

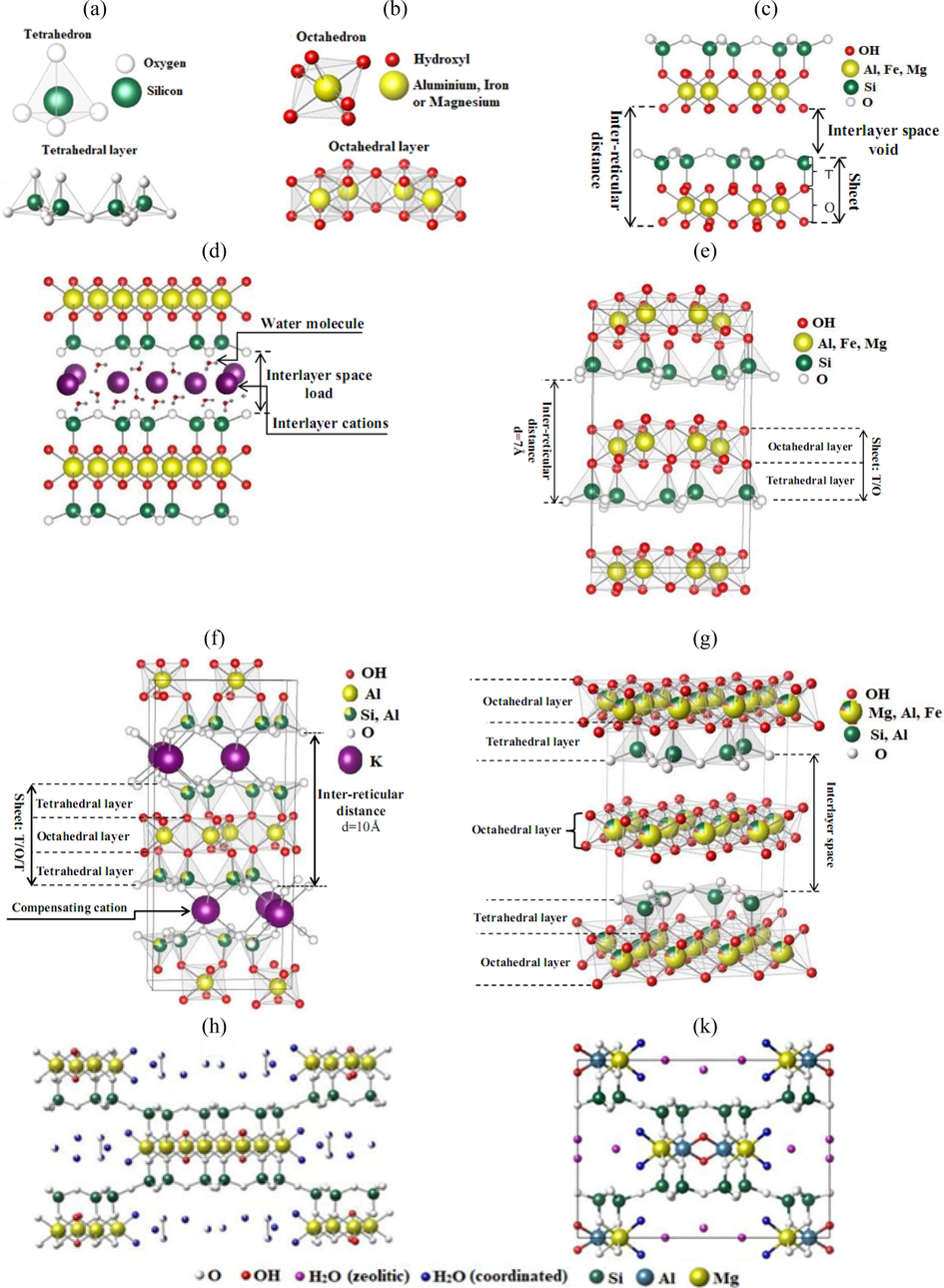

Clays and clay minerals have a small particle size and a complex porous structure with a large specific surface area relative to the volume of the particles, which allows strong physical and chemical interactions with dissolved species. These interactions are due to electrostatic repulsion, crystallinity, and specific adsorption or cation exchange reactions. The highly porous surface that has an attractive force suggests that the binding power will also be high (Uddin, 2017). The surface area of clays is greater than that of minerals of the same size but in different shapes, in addition to the relative surface area increasing with decreasing diameter (Velde, 1995).

The total surface includes the external surface, included between the clay particles, and the internal surface corresponding to the interfoliar space, except for the kaolinite group, which has only an external surface (Fig. 2a) (Mbuyi, 2012). The typical values of the surfaces of the main clay families are provided in Fig. 2b (Berthonneau, 2013).

(a) External and internal clay surfaces (for example, smectite); (b) External, internal, and total specific surfaces of major clay families.

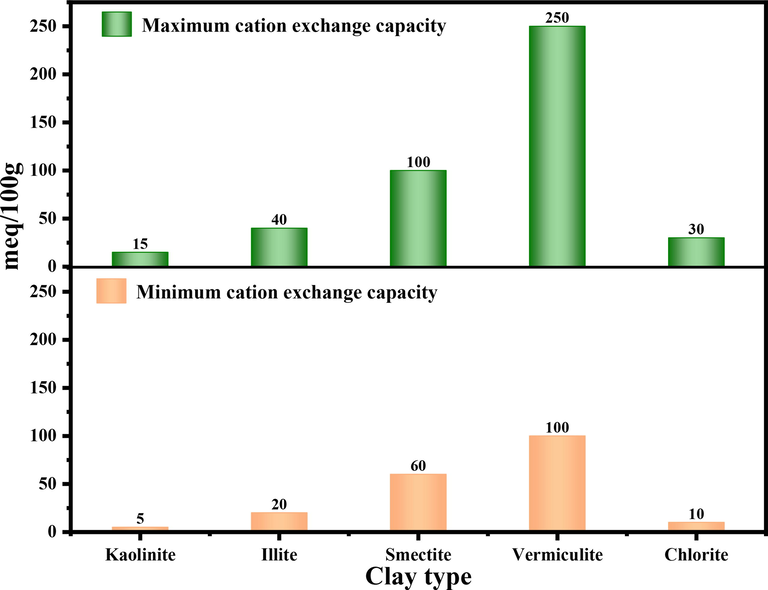

3.3 Cation exchange capacity

One of the most important properties of clay minerals is their cation exchange capacity (CEC). Because of its negative structural charge, clay can reversibly fix some cations in aqueous solutions (Qlihaa et al., 2016). Substitutions of cations of different electrical charges then cause a loss of the electrical neutrality of the sheet. The stability of the crystal structure is then ensured by the presence of compensating cations in the interfoliar space. These ions adsorbed on the surface can be called “ions in exchangeable position”. They can be differentiated into two categories: those strongly bound to the surface like K+ ions and those easily exchangeable with the ions of the solution. The sum in milliequivalent per 100 g of clay of all the cations adsorbed on the surface of the clay is called: Cationic Exchange Capacity (CEC in meq/100 g). The CEC is then a measure of the capacity of the clay to exchange compensating cations, the most common (Li+, Na+, Ca2+, K+, or Mg2+) (Bernard, 2022; Muhammed et al., 2021). The CEC is generally given only for a neutral pH. In addition, the CEC value can be determined by a simple test known as the methylene blue (MB) test (Yukselen and Kaya, 2008). Fig. 3 gives the CEC values for some clay families (Muhammed et al., 2021).

Cation exchange capacities of the main clay families.

4 Industrial uses of clays

Clays and clay minerals are more and more used daily nowadays and are reasonably replacing metals in various fields as cheaper, more efficient, and more environmentally friendly alternatives (A. G. Olaremu, Chemistry Research Journal. 6, 157-168, 2021). Clay has a wide range of industrial uses (Table 3), high geological availability, and large reserves and production facilities. However, the ceramic industry is the main consumer of this raw material (Comin et al., 2021). Treatment of water intended for consumption Treatment of industrial wastewater from painting Orthopedic prostheses Dental restorations Hips and bone grafts Halloysite nanotubes can be loaded with various drugs, including anticancer drugs, antibiotics, analgesics, antihypertensives, anti-inflammatories, and nucleic acid therapeutics. Halloysite nanotubes modified with chitosan oligosaccharides show the ability to enhance the therapeutic effect of the anticancer drug doxorubicin. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Areas of use

Application example

Ref

Ceramic industry

Traditional ceramics

Type

Terracotta

Bricks, tiles, flues, drainage pipes, floor and wall coverings, floor and wall coverings, and pottery

(Martinello et al., 2022; Kieufack et al., 2021)

Earthenware

Sanitary equipment, dishes, and tiles

(Chalouati et al., 2021; Dondi et al., 2021)

Sandstone

Floor tiles, pipes, chemical equipment, and sanitary equipment

Porcelains

Tableware, chemical devices, and electrical insulators

(Arslan, 2021; Pahari et al., 2021)

Ceramics for the environment

Type

Filtres

(Akowanou et al., 2016; Grema et al., 2021; Opafola et al., 2021)

Mineral membranes

Treatment and recovery of textile wastewater

(Ağtaş et al., 2021)

Heterogeneous catalysts

Degradation of the antibiotic sulfathiazole

(Rojas-Mantilla et al., 2021)

Adsorbents

Removal of NO2 and SO2 gases

(Kinoshita et al., 2022)

Bioceramics

Used in the human body

(Kenawy and Khalil, 2020)

Refractory ceramics

Electric furnace, blast furnace, ladle steel, household waste incinerator, glass melting furnace, and rotary cement furnace construction

(Grine et al., 2021)

Water treatment

Categories

Wastewater

Removal of pollutants from water by:

Adsorption process

Clay ceramic filter

(Olaremu et al., 2021)

Industrial process water

Drinking water

Oil industry

Clay was used as a filler and catalyst carrier.

Food Industry

Bio-nanocomposite films for food packaging, storage, and preservation, effective against food spoilage bacteria

(Jayakumar et al., 2021; Tiwari et al., 2021)

Cosmetic industry

High-quality pyrophyllite is used as a base in various face and body powders.

(Ali et al., 2021)

Pharmaceutical industry

(Mobaraki et al., 2021; García-Villén et al., 2021)

Paper industry

Papermaking

(Ali et al., 2021)

Plastic industry

Pyrophyllite is used as a filler in a variety of applications, such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), and high-density polyethylene (HDPE).

Rubber industry

Low-grade pyrophyllite is used as a dusting agent, lubricating molds and preventing surface sticking during manufacturing.

Insecticide industry

Pyrophyllite is used as a carrier in insecticides.

Paint industry

High-quality finely ground pyrophyllite is used in paints as a pigment filler and suspending agent.

Energy domain

Solar and chemical energy conversion

Manufacture of clay-based composites for photocatalysis (photocatalysts).

Energy storage and conversion

Synthesis of Si nanostructures derived from silicate minerals and their composites for application in energy-related fields such as rechargeable batteries, and hydrogen evolution.

Layered nanoclays and their derivatives as electrodes, electrolyte fillers/additives, separators in rechargeable batteries and superconductors, and catalysts in water splitting, CO2 reduction, and oxygen reduction.(Zou et al., 2022; Boutaleb et al., 2021; Wan et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2021)

Metal casting

Make art objects, ornaments, and objects of daily use.

(Eyankware et al., 2021; Nnamele and Egwuonwu, 2020)

Clay materials are characterized by the presence of a significant proportion of fine phyllosilicate particles smaller than 2 μm (Barakan and Aghazadeh, 2021). Due to the sheet structure of these particles, clays are different from other powders used in ceramics. The high specific surface of these minerals and their platelet structure allow clays to form gels, colloidal suspensions, and especially plastic pasted with water (Zaccaron et al., 2021).

The production of silicate ceramics is largely based on this characteristic in that it facilitates the preparation of suspensions (homogeneous and stable) suitable for the casting of malleable pastes (easy to shape), as well as raw parts with good mechanical resistance (Sabatino et al., 2021).

Clays can be modified by different methods summarized in Fig. 10. The synthesis of natural clay-based composites improved electrochemical properties for applications in the field of energy storage and conversion (Lan et al., 2021). Fig. 4 and Table 3 present some uses of clays.

Uses of natural clays in various fields.

5 Removing organic and inorganic pollutants by raw clay

5.1 Removal of dyes with natural clays

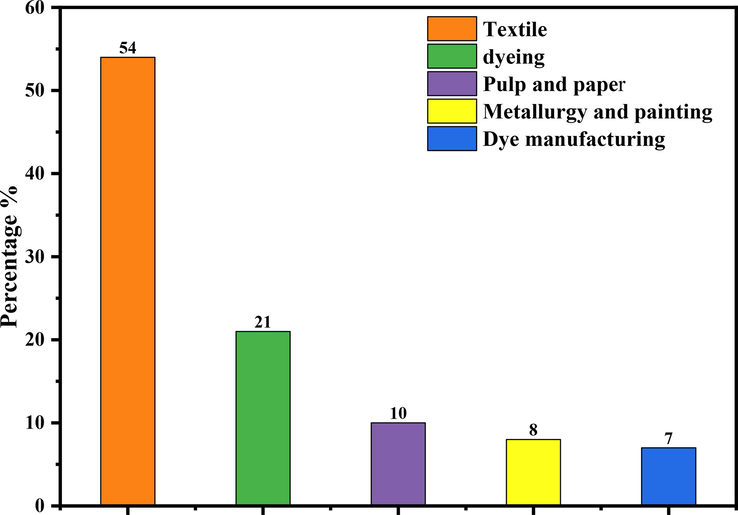

Dyes are organic compounds, an assembly of chromophore groups (NR2, NHR, NH2, COOH, and OH), auxochromes (N2, NO, and NO2), and conjugated aromatic structures (benzene rings, anthracene, perylene, etc.) (Sakin Omer et al., 2018; Bouazza, 2019). Dyes can be divided into three categories according to their core structure: anionic dyes (acidic, reactive, and direct), non-ionic dyes (disperse), and cationic dyes (basic) (Sakin Omer et al., 2018; Elgarahy et al., 2021; Sharma et al., 2021). Fig. 6 shows the main dyes classified according to their application methods on different substrates (Jency et al., 2021; Benkhaya and rabet, 2020). They are widely used in various industries, such as printing, food, cosmetics, leather, paper, and textile industries. (Jency et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021). This industry will lead to excessive wastewater discharges of organic dyes, which are potentially toxic and cause serious pollution to the environment and human health (Sivakumar and Lee, 2022; Qin et al., 2021). The industries responsible for the presence of dye effluents in the environment are presented in Fig. 5 (Boukarma et al., 2021). During the weaving process, approximately 10–15% of the dye is released into the receiving aquatic environment, resulting in highly colored pollutants that are aesthetically unfavorable to the environment (Velusamy et al., 2021). However, most organic dyes are difficult to degrade under natural conditions due to their structural stability and high solubility (Benjelloun et al., 2021; Nath et al., 2018). Therefore, from an ecological and environmental point of view, it is very necessary to eliminate or minimize the concentration of these dyes in wastewater before discharging them into water bodies (Bisaria et al., 2021).

Percentage of industries responsible for the presence of dye effluents in the environment.

Different classes of dyes and their industrial applications and health effects.

Currently, recent studies (Table 4) show that natural clay materials have some advantages in the adsorption of cationic and anionic dyes. The main characteristics and adsorption capacity of some natural clay adsorbents to remove different dyes in water at a laboratory scale are presented in Table 4.

Adsorbent

Adsorbate

Types of dyes

Adsorption capacity

Kinetic model

Adsorption isotherm

Specific surface area (m2/g)

Ref

Iranian natural clay Bushehr

SY

Cationic

67.82 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir12.85

(Esvandi et al., 2020)

NB

Anionic

72.25 mg g−1

Colombian natural bentonite clay

BR 46

Cationic

594 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

47

(Paredes-Quevedo et al., 2021)

Iranian natural clay Isfahan

CV

Cationic

9.37 mg g−1

–

–

40

(Najafi et al., 2021)

Moroccan clay Na-Montmorillonite

TB

Cationic

5.80 mmol g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

77

(El Haouti et al., 2019)

CV

Cationic

5.40 mmol g−1

Iraqi red kaolin clay

MB

Cationic

240.4 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir and

Freundlich35.6

(A. H. Jawad A. S. Abdulhameed, , 2020)

Turkey's raw Sepiolite clay from Eskişehir

DR 23

Anionic

649.37 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

329.7

(Largo et al., 2020)

MB

Cationic

125 mg g−1

Tunisian natural clay from Jebel Romana

BY 28

Cationic

76.92 mg g−1

–

Langmuir

71(Chaari et al., 2019)

Tunisian natural clay from Khledia

AB 75

Anionic

8.33 mg g−1

–

52.2

Tunisian natural clay from Jebel Stah

SLV

Anionic

12.5 mg g−1

–

Langmuir

85

(Chaari et al., 2021)

Chinese natural red clay from Gansu Province

MB

Cationic

112.39 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

57.34

(Wang et al., 2021)

TC

109.35 mg g−1

Chinese natural red clay from Inner Mongolia

MB

Cationic

85.79 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

58.96

TC

93.19 mg g−1

Moroccan red clay from the Tetouan region

MB

Cationic

18.7 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

22.4

(Bentahar et al., 2019)

Moroccan rhassoul clay from the east of the Middle Atlas

166.7 mg g−1

119

Natural bentonite

BV16

Cationic

434.78 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

43.35

(Khalilzadeh Shirazi et al., 2020)

Tunisian natural clay from Tabarka

RR 120

Anionic

1.2 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

47

(Abidi et al., 2019)

Tunisian natural clay from Fouchana

0.8 mg g−1

80

Illitic clay

MB

Cationic

62.5 mg g−1

–

Langmuir

128

(Sakin Omer et al., 2018)

CV

Cationic

330.0 mg g−1

Freundlich

Tunisian raw haloysitic clay from the Nefza region

DO34

Anionic

9.48 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Freundlich

20

(Chaari et al., 2015)

Algerian natural bentonite from Maghnia

MB

Cationic

345.82 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

84

(Oussalah et al., 2019)

CR

Anionic

315 mg g−1

Moroccan natural Safiot Clay

MB

Cationic

68.49 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

-

(El Kassimi et al., 2021)

SAF

Cationic

45.45 mg g−1

Turkey's natural clay from Erzurum Province

MB

Cationic113.63 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

-

(Bingül, 2022)

Iranian natural clay K from Azarshahr

MBCationic

123.5 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

34.66

(H. Aghdasinia H. R. Asiabi, Environ, , 2018)

Iranian natural clay D from Azarshahr

909.09 mg g−1

43.78

Iranian natural clay G (purchased from Tabriz)

833.33 mg g−1

52.85

Moroccan natural clay from the Jorf Arfoud region

MO

Anionic

13.71 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Freundlich

-

(Assimeddine et al., 2020)

MB

Cationic

15.82 mg g−1

Langmuir

Tunisian raw clay from Jebel Louka

MR

Anionic

397 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

37.7

(Romdhane et al., 2020)

Turkey's natural red clay from Oltu/Erzurum region

MG

Cationic

84.75 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Freundlich

41.87

(Sevim et al., 2021)

Tunisian Smectite Clay

CV

Cationic

86.54 mg g−1 (Sono-assisted adsorption)

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir-Freundlich and Toth

74

(Hamza et al., 2018)

Moroccan natural clay from the Agadir region

MB

Cationic

279.95 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

76.971

(Bentahar et al., 2017)

CV

Cationic

231.74 mg g−1

CR

Anionic

61.12 mg g−1

Moroccan natural clay from Fez city

BG

Cationic

101 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

28

(Hicham et al., 2019)

YL

Cationic

127 mg g−1

Brazilian bentonite

MO

Anionic

2.2 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Sips

-

(Fernandes et al., 2020)

MB

Cationic

100 mg g−1

Tunisian natural clay from Djebel Aïdoudi

MB

Cationic

241.96 mg g−1

–

Langmuir

69.00

(Amari et al., 2018)

Saudi natural red clay from the southern region

MB

Cationic

50.25 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

63.15

(Khan, 2020)

Moroccan natural Safiot clay from the Safi region

BB9

Cationic

58.45 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

-

(El Kassimi et al., 2021)

BY28

Cationic

58.89 mg g−1

Pakistani bentonite clay

MG

Cationic

223 mg g−1

pseudo-

first-orderLangmuir

115.99

(Ullah et al., 2021)

Bentonite purchased from Alfa Aesar

149 mg g−1

38.306

Turkey's red mud clay

125 mg g−1

16.796

Moroccan natural Muscovite clay from the Khemisset region

MB

Cationic

59.828 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

–

-

(Amrhar et al., 2021)

Moroccan natural Safiot clay from Safi city

BB9

Cationic

68.49 mg g−1

–

Langmuir

-

(El Kassimi et al., 2020)

BB41

Cationic

128.2 mg g−1

BY28

Cationic

166.67 mg g−1

Iraqi natural clay from Topkhana

MB

Cationic

128.8 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

53.5

(Salh et al., 2020)

Algerian natural bentonite from Maghnia

MV

Cationic

480.79 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

-

(Mahammedi, 2021)

Palygorskite cay

SAF

Cationic

195 mmol kg−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

173

(Sieren et al., 2020)

Sepiolite clay

45 mmol kg−1

250

Kaolin clay

MB

Cationic

83 mg g−1

–

–

-

(Ethaib et al., 2020)

Moroccan bentonite clay from the Nador region

MB

Cationic

60 mg g−1

–

Freundlich

271.81

(Hmeid et al., 2021)

Sepiolite clay

BR46

Cationic

110 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Freundlich and Langmuir

108

(Santos and Boaventura, 2016)

DB85

Anionic

232 mg g−1

pseudo-first-order

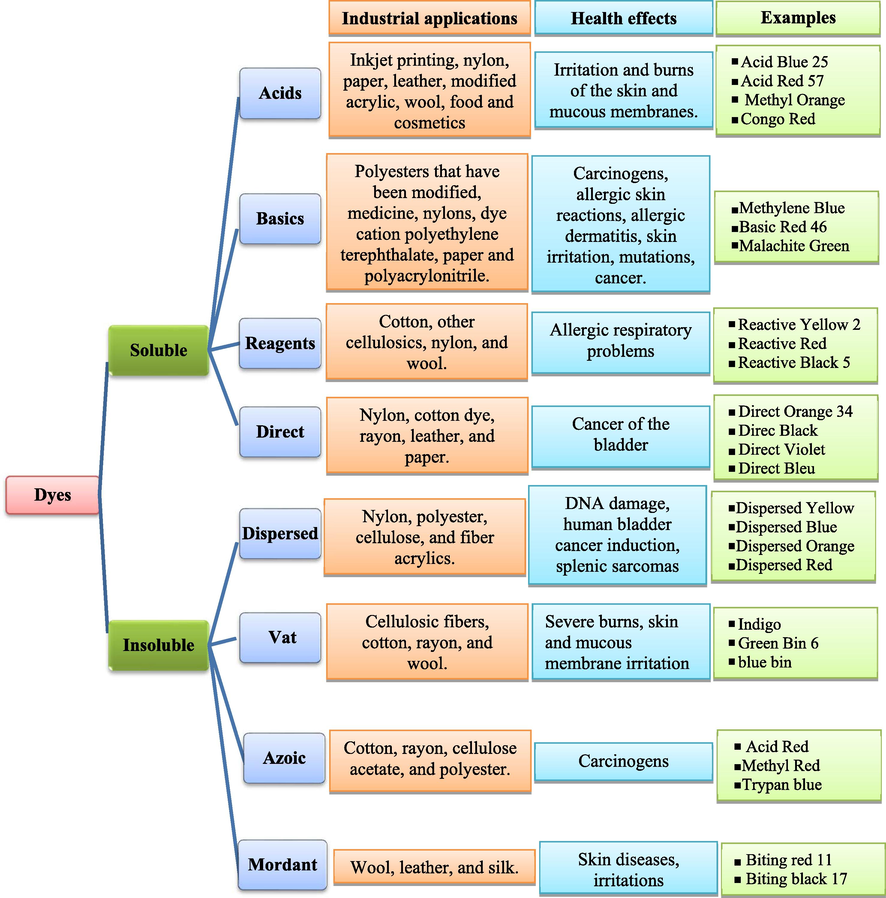

Langmuir

The analysis of the studies reported in this review allowed us to note that the evaluation of the adsorption capacity of the natural clays for the elimination of the dyes must take into account several variables; the properties of the natural clay (specific surface, the capacity of cationic exchange CEC, the mineralogical composition, etc.). The size, shape, and type of the targeted dyes as well as the experimental conditions such as the pH, the dose of adsorbent, the initial concentration of adsorbate, the temperature, the contact time, etc. From the results of the table below, we can see that most of the studies concerned the removal of methylene blue dye (BM), one of the most abundant pollutants in the aquatic environment (Wang et al.,2021).

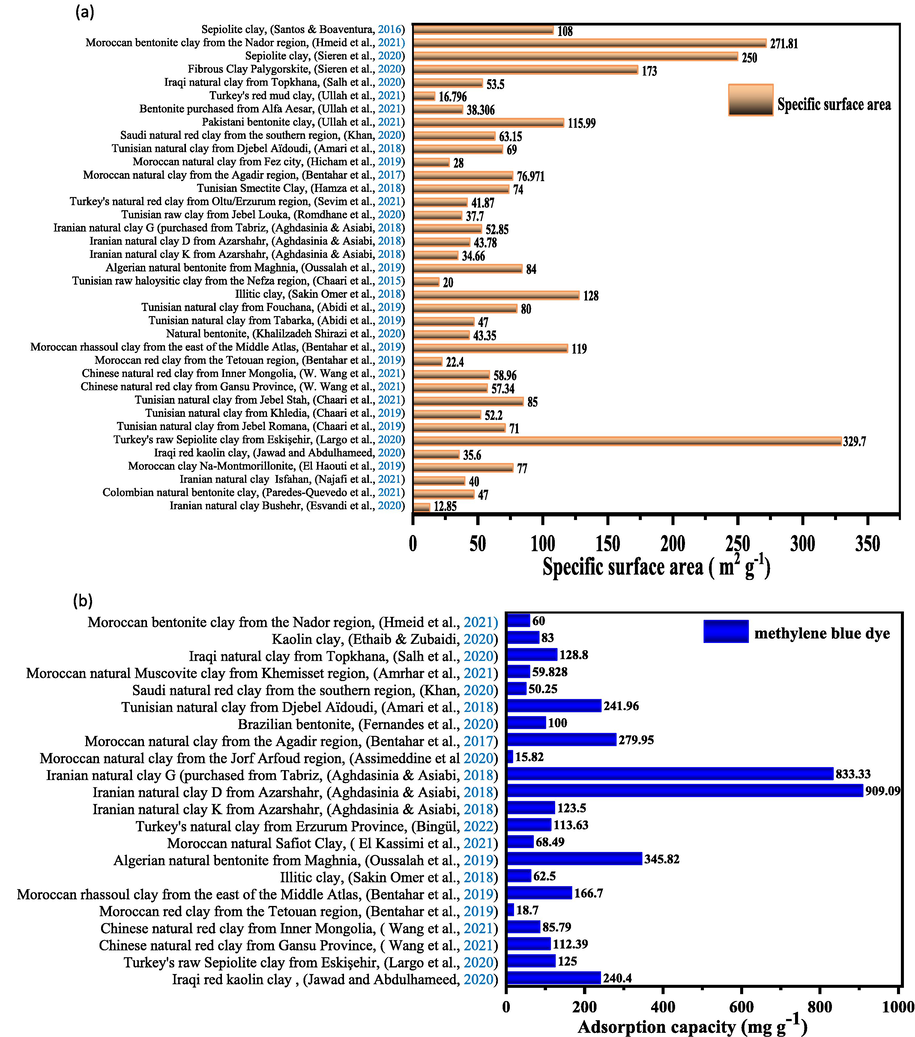

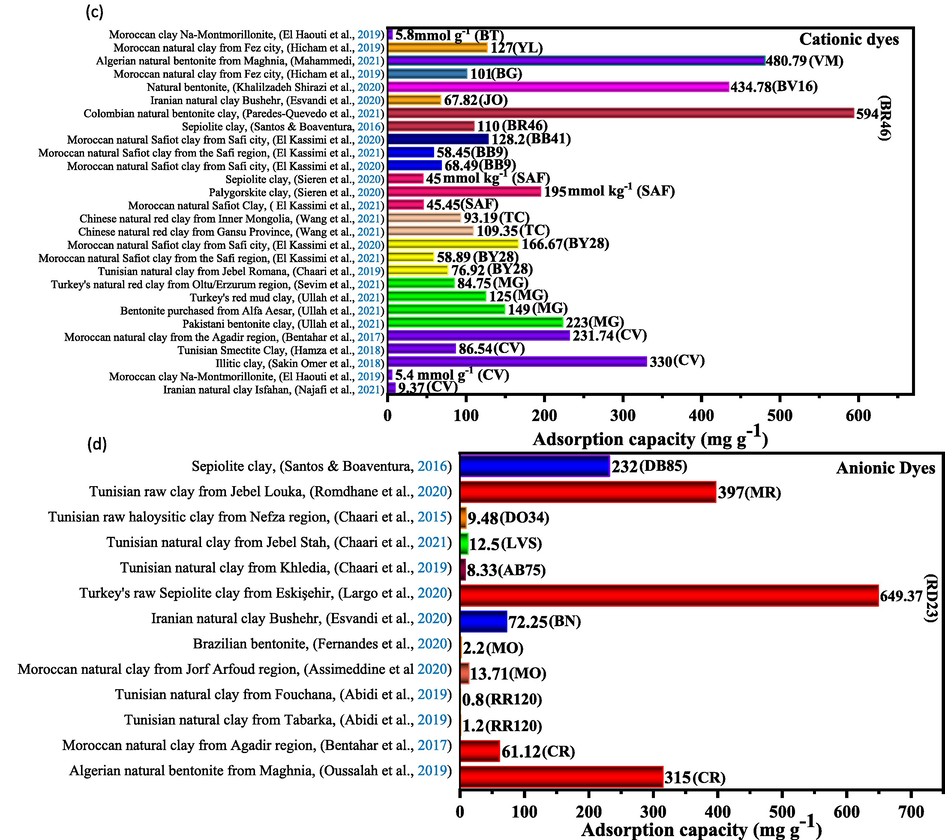

Fig. 7a summarizes the specific surface area values for natural clays, while Fig. 7b, Fig. 7c, and Fig. 7d show the adsorption capacities of BM and some cationic and anionic dyes, respectively.

Comparison of: (a) specific surface values, (b) the adsorption capacities of MB cationic dye, (c) the adsorption capacities of some cationic dyes, (d) the adsorption capacities of some anionic dyes by various natural clays.

Comparison of: (a) specific surface values, (b) the adsorption capacities of MB cationic dye, (c) the adsorption capacities of some cationic dyes, (d) the adsorption capacities of some anionic dyes by various natural clays.

Fig. 7b summarizes a comparison of the removal of the cationic dye BM by various natural clays. It is observed that Iranian natural clay studied by H. Aghdasi et al (Goswami et al., 2021) is characterized by the highest adsorption capacity of BM dye of 909.09 mg g−1. M. Assimeddine et al (Aghdasinia and Asiabi, 2018) obtained the lowest adsorption capacity of 15.82 mg g−1 using natural Moroccan clay. Due to its large specific surface area and high affinity for MB, natural clay is a good adsorbent for MB removal (Assimeddine et al., 2020). In addition, some clays have a net negative charge, which gives them strong cationic adsorption properties (Rafatullah et al., 2010).

The highest specific surface area of the natural Turkish sepiolite clay is about 329.7 m2/g with adsorption capacities of 649.37 mg g−1 for the anionic dye RD23 and 125 mg g−1 for the cationic dye BM (Guaya et al., 2021), while the lowest value of Iranian natural clay is about 12.85 m2/g, and the adsorption capacities of JO cationic dye and BN anionic dye are 67.82 mg g−1 and 72.25 mg g−1, respectively (Largo et al., 2020).

Furthermore, the results indicate that the most appropriate model for the adsorption kinetics of the majority of dyes (cationic or anionic) is the pseudo-second-order model. Furthermore, the authors reported that the adsorption process follows the Langmuir isotherm (Table 4).

5.2 Heavy metals removal

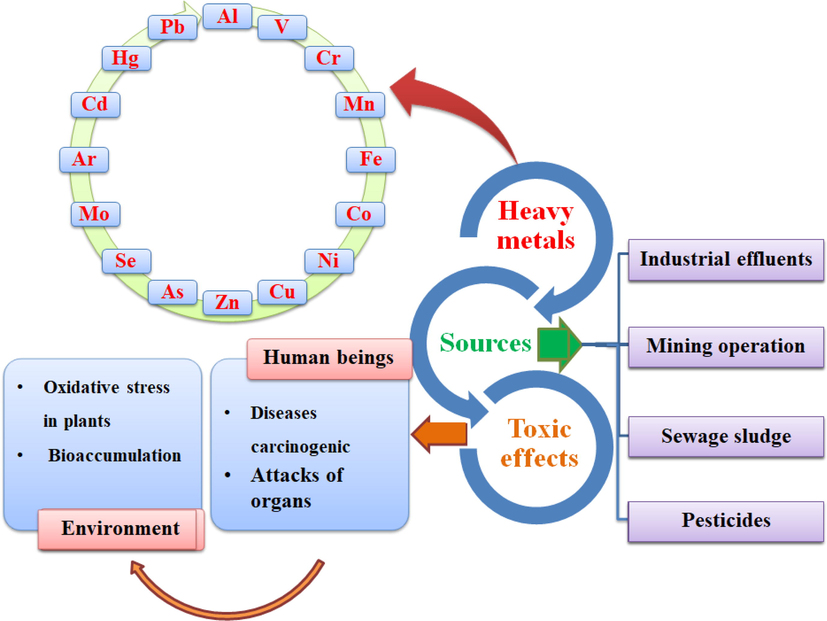

Heavy metals are metallic elements that occur naturally and have a density greater than 5 g cm−3 (Briffa et al., 2020). The most common heavy metals are shown in Fig. 8 below and are widely recognized as bioaccumulative elements from various sources that hurt the environment and human health (Fig. 8) (Izydorczyk et al.,2021; Saravanan et al., 2021; Ait Ichou et al., 2020). The most toxic are chromium (Cr), manganese (Mn), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg) and lead (Pb) (Saravanan et al., 2021). Some low concentrations of heavy metals play a very important role in the human body: The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommends 0.9 mg day−1 of Cu, 0.5 mg day−1 of Ni, 0.05 to 0.2 mg day−1 of Cr, 8 to 11 mg day−1 of Zn, and 8 to 18 mg day−1 of Fe (U.s., 2001). Recent studies are grouped in Table 5 on the removal of heavy metals by adsorption using natural clay as an adsorbent.

Some sources and toxic effects of common heavy metals.

Adsorbent

Heavy metals

pH

Dose

Concentration of M(II)

Time

(min)

Equilibrium temperature

Adsorption capacity

Kinetic model

Adsorption isotherm

Specific surface area

(m2/g)

Ref

Moroccan natural clay from the Tangier - Tetouan - Al Hoceima region

Cd(II)

5.6

3 g/60 mL

100 mg/L

60

–

92 %

–

Langmuir and Freundlich

-

(Es-sahbany et al., 2021)

Moroccan natural clay from

ChaouiaCu(II)

5

0.02 g/40 mL

100 mg/L

90

Room temperature

48.24 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

-

(Barrak et al., 2021)

Pakistani silty clay from Baluchistan

Ni (II)

5

0.6 g

50 μg/L

60

318 K

3.603 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

-

(Samad et al., 2020)

Cd (II)

7

0.4 g

50 μg/L

60

318 K

5.480 mg g−1

Moroccan natural clay from Sale

Cu (II)

8.5

–

100 ppm

85

–

86 %

85.5%

84 %

85%–

Langmuir and Freundlich

-

(Es-sahbany et al., 2021)

Co(II)

8

84

Ni (II)

8

85

Pb (II)

8.5

83

Moroccan natural clay from the northern region

Ni(II)

4

6 g/L

140 mg/L

100

338 K

1.407 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Freundlich

-

(Loutfi et al., 2021)

Tunisian natural clay

from Jebel ChakirCr(III)

5

1 g/L

200 mg/L

120

(22 ± 3 °C)

179 mg g−1

–

–

48.95

(Ghorbel-Abid and Trabelsi-Ayadi, 2015)

Moroccan natural clay from the river “Abu Burq”

Cd (II)

–

2 g/L

200 mg/L

10

(25 ± 2 °C)

5.65 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

–

-

(Es-said et al., 2021)

Ukrainian chamotte clay

Pb (II)

6

1 g

500 mg/L

24 h

Room temperature

11 mg g−1

–

Langmuir

-

(Rakhym et al., 2020)

Moroccan natural clay from the Ouezzane region

Ni(II)

7

3.5 g

100 ppm

2 h

25 °C

2.4 mg g−1

(70–75%)

–

Freundlich and Langmuir

-

(Es-sahbany et al., 2019)

Romanian natural clay from Vladiceni

Pb(II)

7

4.0 g/L

0.40 mmol/L

10

(20 ± 2 °C)

0.098

mmol/g

(97 %)Pseudo-second order

Freundlich

-

(Azamfire et al., 2020)

Hg(II)

2

4.0 g/L

0.40 mmol/L

10

(20 ± 2 °C)

0.059

mmol/g

(55 %)

Iraqi natural clay from Tagaran

Cd (II)

6

0.1 g

100 mg/L

100

20 °C

11.5 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir and Freundlich

51.4

(Aziz et al., 2020)

Bentonite clay

Cr(III)

6

1 g/L

10 mg/L

90

25 °C

151,5 mg/g (95.21%)

Pseudo-second order

Freundlich

15.646

(Ahmadi et al., 2020)

Cr(VI)

3

161.3 mg g−1

(95.74%)

Algerian kaolin clay from Bordj Bou Arreridj region

Cu(II)

7

0.2 g

25 et 50 mg/L

100 mg/L10

3025 °C

52.63 mg g−1 (97.5%)

Pseudo-second order

Temkin

7.5

(Bahah et al., 2020)

Pb(II)

7

0.2 g

25, 50 et 100

mg/L.First minute at all concentrations

25 °C

57.30 mg g−1

(99.95%)

Tunisian natural clay from Jebel El Aidoudi

Cd(II)

6

1 g/L

–

3 h

20 °C

21.93 mg g-1

–

Langmuir

86

(Khalfa et al., 2020)

Zn(II)

20.86 mg g-1

Pb(II)

29.11 mg g-1

Cu(II)

22.30 mg g-1

Algerian natural clay from El Menia

Pb(II)

5–6

1 g

10 mg/L

40

25° C

15.5 mg g-1

Pseudo-second order

Temkin

79.46

(Athman et al., 2020)

Zn(II)

2.10 mg g-1

Langmuir

Cu(II)

7.35 mg g-1

Freundlich

Ni(II)

60

9.80 mg g-1

Freundlich

Nigerian bentonite clay from Afuze

Fe(III)

6

0.05 g

88.52 mg/L

150

303 K

4.2 mg g-1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

-

(Abdullahi et al., 2020)

Zn(II)

3.276 mg/L

2.9 mg g-1

Commercial bentonite clay

Cr(VI)

2

0.04 g

58 ppm

60

25 °C

11.076 mg g−1

–

Scatchard

-

(Altun, 2020)

Egyptian natural clay near the city of Minia

Cr(VI)

5

0.5 g/L

30 mg/L

90

298 K

7.0 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Freundlich

34

(E. A. Ashour M. A. Tony, SN, , 2020)

Natural clay bentonite

Cu(II)

4.6

60 g/L

80 mg/L

–

27 ± 1 °C

99.9%

–

–

-

(Esmaeili et al., 2019)

Zn(II)

13 mg/L

89.2%

Ni(II)

1 mg/L

99.9%

Montmorillonite (MMT)

Ni(II)

2.4

0.1 g/L

100 mg/L

180

25 °C

12.89 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

699

(Gafoor Dhanasekar et al., 2021)

Cu(II)

7.62 mg g-1

Egyptian natural clay from El-Hammam

Fe(II)

1.5

0.1 g

50 mg/L

60

25 ± 1 °C

5.74 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

-

(El-Maghrabi and Mikhail, 2014)

Ni(II)

1.17 mg g−1

Zn(II)

4.33 mg g−1

Saudi natural clay

Pb(II)

6.2

1 g/L

20 mg/L

1 h

–

166 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

28

(Abdel Ghafar et al., 2020)

Moroccan natural clay from the Marrakech region

Cd(II)

–

0.8 g

200 mg/L

120

–

5.25 mg g−1

Pseudo-second order

Langmuir

23.07

(Abbou et al., 2021)

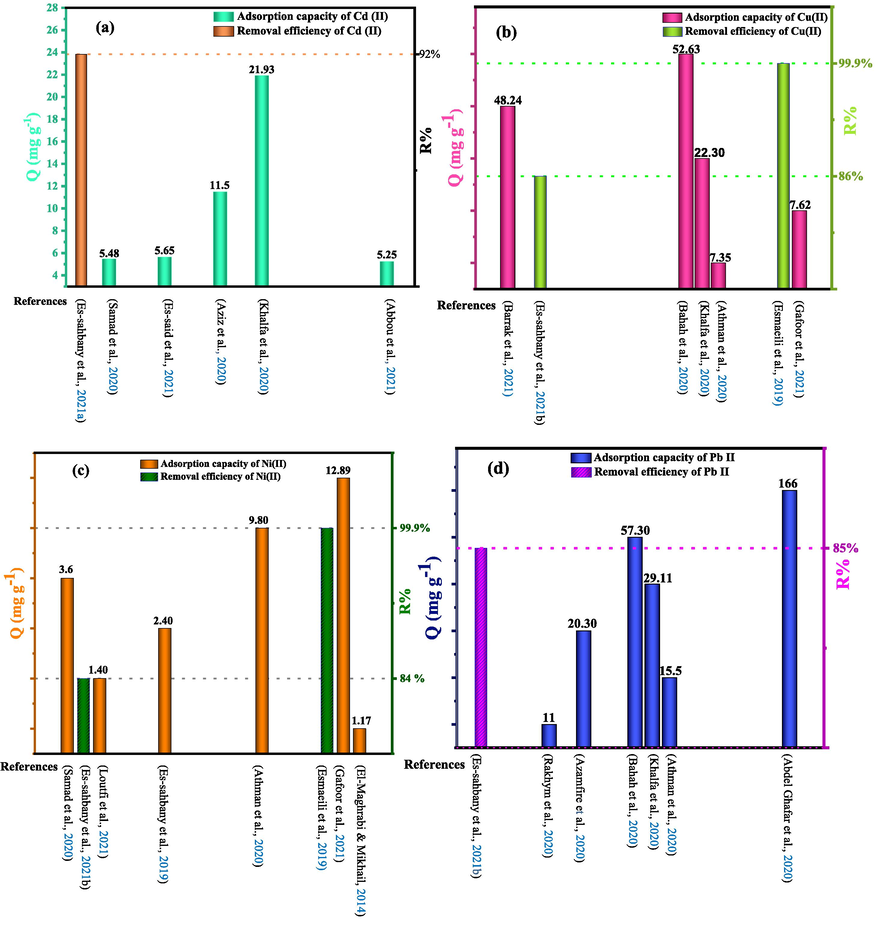

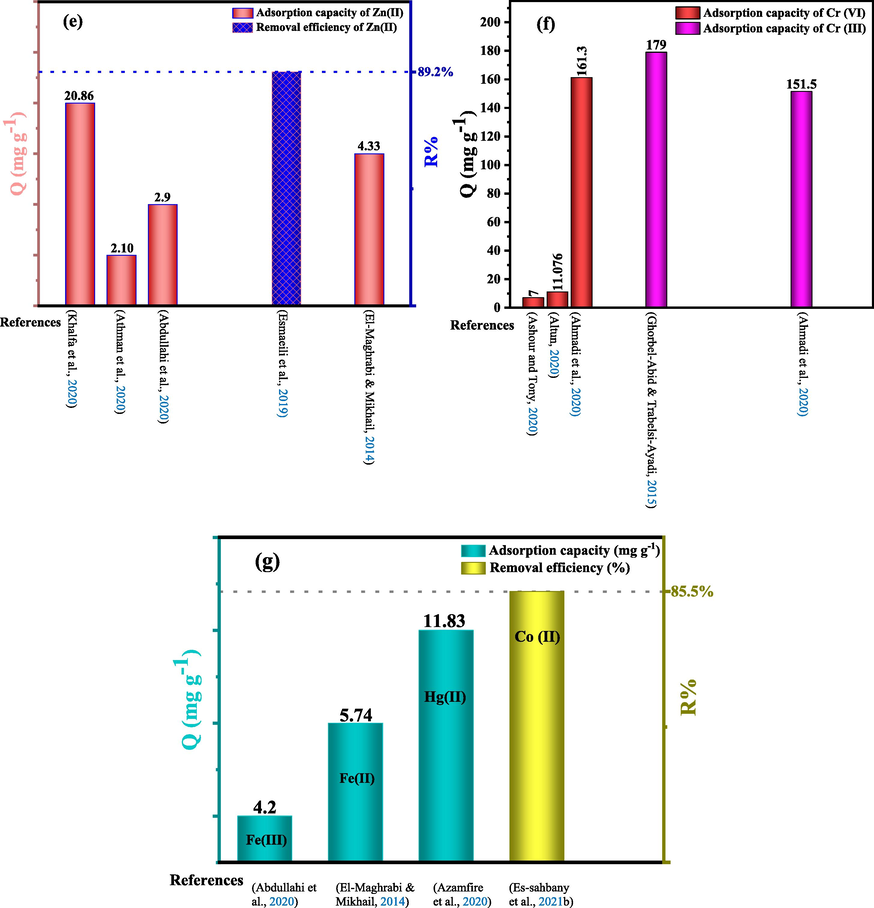

From the recent research results summarized in Table 5 below, it can be seen that natural clay is capable of removing heavy metals to a great extent. Due to their strong tendency to form covalent bonds, clay minerals have a better affinity for heavy metals than alkali and alkaline earth cations (Gahlot et al., 2020). This power also depends on several parameters, namely the specific surface, the cationic exchange capacity (CEC) and the environmental conditions (pH of the solution, contact time, ionic strength, coexisting ions, dose of clay, initial concentration of heavy metals and temperature) (Mao and Gao, 2021). According to the results found, as shown in Table 5, the removal rates of Hg (II) ions by natural Romanian clay at pH = 4.6 and Ni (II) ions by natural bentonite at pH = 2 are 55% and 99.9%, respectively. Table 5 shows that the model best suited to the kinetics of heavy metal adsorption by natural clays is the pseudo-second-order model. Furthermore, the majority of heavy metals also obey the Langmuir isotherm.

Fig. 9 (a-g) shows the adsorption capacity (mg/g) or removal rate (%) of heavy metals listed in Table 6 by various natural clays.

Comparison of some natural clays for the removal of heavy metals, (a) Cadmium (Cd(II)), (b) Copper (Cu(II)), (c) Nickel (Ni(II)), (d) Lead (Pb(II)), (e) Zinc (Zn(II)), (f) Chromium (Cr(III) and Cr(VI)), (g) Iron ((II), Fe(III)), Mercury (Hg(II)) and Cobalt (Co(II)).

Comparison of some natural clays for the removal of heavy metals, (a) Cadmium (Cd(II)), (b) Copper (Cu(II)), (c) Nickel (Ni(II)), (d) Lead (Pb(II)), (e) Zinc (Zn(II)), (f) Chromium (Cr(III) and Cr(VI)), (g) Iron ((II), Fe(III)), Mercury (Hg(II)) and Cobalt (Co(II)).

Natural

Clay

SBET

Clay Natural

(m2/g)

Adsorbate

Adsorption capacity/ efficiency

(mg/g)

(before Modification)

Modification/ methodes

SBET

Clay modifier

(m2/g)

Characterization

Adsorption capacity/ efficiency

(mg/g)

(after Modification)

Ref

Chinese natural red clay from Gansu Province

57.34MB

112.39

Hydrothermal reconstitution

353.63

XRD, SEM, FTIR, BET and

XPS215.68

(Wang et al., 2021)

TC

109.35

209.6

Chinese natural red clay from Inner Mongolia

58.96MB

85.79

348.13

226.40

TC

93.19

230.2

Iranian natural clay from Dashtestan, Bushehr province

–

Cr(VI)

63.69

Chitosan/Clay composite

–

FTIR, AFM,

SEM, VSM, TEM

and XRD80.30

(Foroutan et al., 2020)

Chemical deposition method

Clay/Fe3O4

–

97.08

Chemical precipitation technique

Chitosan /Clay/Fe3O4

–

117.64

Clay industry Best Way Cement Hattar (Pakistan)

8.41

BFBN

25.05

Biocomposite of sodium-alginate with acidified clay

–

SEM, XRD, BET

and TGA25.41

(Kausar et al., 2020)

RFRN

15.90

18.97

Moroccan natural clay from Agouraï city

51.4154

Phenol

10.01

Acidified clay

(Chemical activation)74.4397

XRF, XRD, SEM, BET and FTIR

15.11

(Dehmani et al., 2020)

Algerian halloysite from

Eastern Region64

CV

–

Halloysite was processed at 600 ◦C and then by acid leaching with HCl solutions of different concentrations

H600-0 N

60.5

BET, FTIR, XRD, ICP-AES and BXFM

104.3

(Belkassa et al., 2021)

(Mellouk et al., 2009)

H600- 0.5 N

115.4

194.5

H600-3 N

434.0

158.4

H600-5 N

503.3

145.5

Moroccan natural clay from Chaouia (CH)

–

Cu(II)

48.24

Composite beads(CH@AL)

(Sodium alginate solution + Clay solution) and stirred until hydrogel was obtained. Then was poured dropwise into 500 mL of 0.1 M CaCl2 using a 50 mL syringe to form spherical beads, then left to harden in CaCl2 solution, and finally washed three times and air dried.–

XRD, SEM-EDX and TGA

92.44

(Barrak et al., 2021)

Tunisian natural clay

85

SLV

12.5

Acidified clay H2SO4-clay (6 h) (Chemical activation)

110

XRD, FTIR and SSA

15.45

(Chaari et al., 2021)

Raw clayKaolinite

(KT)Montmorillonite

(MT)

Vermiculite (VT)-

-

-Ph

0–0.24

Zr-modified clay

Zr2.48-KT

Zr2.48-MT

Zr2.48-VT

incorporation of hydroxy complexes of zirconium (dehydroxylation)-

-

-XRD, SEM and zeta potential

9.58

15.50

9.74(Huo et al., 2021)

Kaolinite

14

OTC

24

Intercalation procedure Methoxy-modified kaolinite Interlayer methoxy grafting of kaolinite was carried out through a reflux procedure.

14.75

XRD, FTIR, and XPS

36

(Ashiq et al., 2021)

Natural montmorillonite (Mt)

77

OG

CTAB@Mt

52

XRD, FTIR, BET, TGA/DTA, and SEM -EDS

169.6

(Ouachtak et al., 2021)

6 Clay modification methods

Many researchers have demonstrated that natural clays have an exceptional ability to remove various toxic organic and inorganic pollutants (Table 4 and Table 5). However, to achieve better results, current research is directed towards the development of clay-based adsorbents with a high removal potential of various contaminants and a low cost. Recent experimental studies available in Table 6 below show that the adsorption capacity of natural clay can be improved after specific modifications, which consequently increase more adsorption sites and functional groups to adsorb different environmental pollutants (Barakan and Aghazadeh, 2021). The modification of natural clay is achieved by the use of acids, calcination, polymers or surfactants. These methods give a relatively high adsorption capacity compared to natural clay. For example, clay can be activated by sulfuric acid to increase its specific surface and pore volume. As shown by several authors, the specific surface can be increased from 16.29 m2/g to 24.68 m2/g and the pore volume from 0.056 cm3 g−1 to 0.064 cm3 g−1, which also leads to an increase in the adsorption capacity (Jedli et al., 2018). However, we have noticed that the texture of the modified clay does not change, because in the case of methoxy-modified kaolinite, the specific surface remains almost unchanged kaolinite and methoxy-modified kaolinite, respectively, 14.2 m2/g and 14.75 m2/g, but the pore volume and pore radius vary considerably (Ashiq et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2016).

Fig. 10 below summarizes some methods of activation and modification of natural clays, and Table 6 shows the effect of this modification on the adsorption capacity of various pollutants, as well as the characterization techniques used for raw and activated/modified clays.

Summary of different techniques for modifying natural clays.

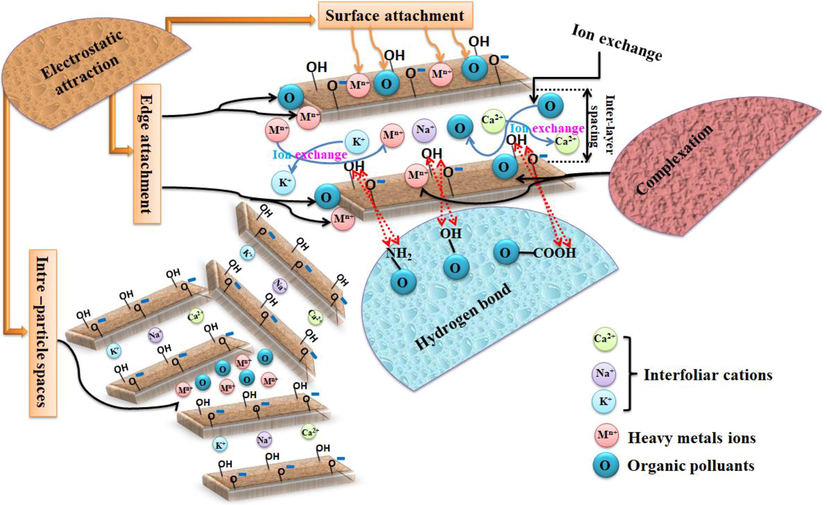

7 Dye and heavy metal adsorption mechanisms on clay

The adsorption process is generally due to several physicochemical forces occurring at the adsorbent-adsorbate interface. The high adsorption performance of dyes and heavy metals obtained by clays could be explained by several adsorption mechanisms, such as electrostatic forces, van der Waals forces, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding, ion exchange, and pore filling. The predominant mechanisms controlling the adsorption of various pollutants by natural and active/modified clays are presented in Fig. 11 (Zhang et al., 2021; Han et al., 2019).

Adsorption mechanism of dyes and heavy metals at different locations on the surface of the clay.

Based on the EDX and FTIR studies, Alorabi et al. (Alorabi et al., 2021) showed that the mechanism by which the cationic crystal violet dye CV was removed by two adsorbents (Saudi natural micro and nanoclays) was of the ion exchange type. Since they observed a decrease of K+ and Ca2+ in both adsorbents, new peaks of N and C appeared in the EDX analytical spectra, and the positions of some peaks in the FTIR spectra were shifted after the adsorption of the CV dye. This confirmed the exchange of K+ and Ca2+ cations by the CV molecules on the surface of the nanoclay. The OH bond peak also shifted to a lower frequency, indicating the formation of hydrogen bonds between the CV dye and the surfaces of both adsorbents.

Es-sahbany et al (Es-sahbany et al., 2022) explained the removal of many bivalent M2+ heavy metal ions (Cu2+, Co2+, Pb2+, and Ni2+) by two adsorption mechanisms: electrostatic attraction and ion exchange. The first one depends on the pH of the aqueous solution, so at low pH, the aqueous solution is rich in hydrogen ions H+, which compete with metal ions M2+ for adsorption sites, limiting the removal of metal ions. Under high pH conditions, OH-adsorbed hydroxyl ions on the clay surface can combine with M2+ ions to improve removal efficiency, supporting the electrostatic attraction mechanism. The second relies on naturally occurring cations (Ca2+, Mg2+, Na+, and K+) in the clay structure, which are exchangeable and can be replaced by M2+ heavy metal ions.

Khan et al (Khan et al., 2021) prepared a nanocomposite (chitosan/alginate/modified clay) as an adsorbent for the removal of cationic (methylene blue, BM) and anionic dyes (acid black 172, AN-172) and Cr (VI). They showed that the adsorption of dyes and metal ions on the nanocomposite occurred rapidly, mainly through electrostatic interaction between the adsorbent and the adsorbate, which they confirmed by FTIR analysis before and after the adsorption process, where the peaks of the adsorbent are shifted after the adsorption of Cr (VI). The C-N peaks of the BM adsorbate and the COO peak of the adsorbent were weakened after adsorption due to the charge neutralization between the N+ group of BM and the COO group of the adsorbent. Similarly, they explained the electrostatic interaction between the sulfonate group of AB-172 and the amino group of the adsorbent by the charge neutralization in which the peaks of the amino and sulfonate groups were weakened, and the appearance of a new peak was responsible for the formation of SO3- and NH3+ by the ionization of the moieties (amino and sulfonate) in water.

8 Clay adsorbent cost comparison

Finding the best low-cost adsorbents capable of removing certain pollutants from water is the subject of many researchers. Many factors control the cost of different adsorbents, such as availability, source, synthesis method, processing conditions, recycling, and stability. Inexpensive adsorbents (mainly natural clays and waste materials) can be modified to increase their adsorption capacity. Efforts can be made to perform a risk assessment, a comparative analysis of the costs associated with the removal of contaminants from water by adsorption. Table 7 below summarizes the comparative cost of different adsorbents.

Adsorbant

Total estimated cost of raw materials used for adsorption

Ref

Treated oil shale ash (TOSA)

2.15 ($ L-1)

(Miyah et al., 2021)

Walnut shells (TWS)

Peanut shells (TPS)0.6968 ($ L-1)

0.6965 ($ L-1) for [MB] = 1 kg/L(Benjelloun et al., 2022)

Biocomposite hydrogel beads

Alginate/Glutaraldehyde/Red Cabbage Extract3.17 ($ kg−1)

(Andreas et al., 2021)

Bentonite clays

0.5–2.2 ($ kg−1)

Graphene oxide (GO)

3.31 ($ g−1)

(Rathour and Bhattacharya, 2018)

Crab Carapace Modified (CCM)

0.561 ($ kg−1) CCM

(Pap et al., 2020)

Biochar

0.35–1.2 $ kg−1

(Han et al., 2019)

Natural clays (montmorillonite, bentonite, etc)

0.04 $ kg−1

Charbon actif

1.8–2.1 $ kg−1

Phosphate natural

0.078 $ kg−1

(Hafdi et al., 2020)

Phosphate natural doped with nickel oxide (NP/NiO)

5.988 $ kg−1

Chitosan

16 $ kg−1

(Momina et al., 2018)

Chitin

10 $ kg−1

A comparison of cost estimates for a number of adsorbents compared with natural clays used in recent studies, as shown in Table 7, shows that natural clays are less expensive and also represent a remarkable potential for remove organic and inorganic pollutants.

9 Regeneration

Regeneration is an important parameter in evaluating the efficiency of an adsorbent suitable for practical applications. It is defined as the recycling or recovery of the sorbent and is crucial in terms of economic sustainability. In addition, the removal of the pollutant-laden adsorbent becomes a secondary pollution problem. Several methods of adsorbent regeneration have been used, including thermal regeneration, chemical regeneration, steam regeneration, pressure swing regeneration, vacuum regeneration, microwave regeneration, ultrasonic regeneration, gamma irradiation, electrochemical and biological regeneration. The regeneration process depends on several parameters such as pH, temperature, time, and cycles required for the treatment. These must be taken into account for the efficient regeneration of the adsorbent. The regeneration of clays is essential in the fight against organic and inorganic pollution, the cost being an important parameter for the development of new adsorbents (Jain et al., 2021). In the case of clays, chemical treatment is widely used because of its low cost and speed of the process, despite its disadvantages of destroying the surface properties of the adsorbent and producing oxidized sludge (Abdullah et al., 2019). Table 8 summarizes some recent studies on the regeneration of clay adsorbents.

Adsorbent

Adsorbates (dyes and heavy metals)

Regeneration method and recovery

Ref

Moroccan muscovite clay

MB

- Thermal regeneration at 500 °C for 3 h, 86.92% recovery after 5 cycles

(Ssouni et al., 2023)

CV

- Thermal regeneration at 500 °C for 3 h, 80.95% recovery after 5 cycles

Tunisian Smectite Clay

CV

- With N2 flow, 79.1% recovery after 5 cycles

- With O2/UV, 75.8% recovery after 5 cycles(Hamza et al., 2018)

Moroccan natural clay

MB

Thermal regeneration at 500 °C for 3 h, about 60% recovery after 5 cycles

(El-Habacha et al., 2023)

Saudi natural red clay

MB

more than 95% recovery after 4 cycles

(Khan, 2020)

Moroccan natural Safiot clay

BB9

35% recovery after 8 cycles

(El Kassimi et al., 2020)

BB41

28% recovery after 8 cycles

Nigerian kaolinite clay

Treated with hydrochloric acid

Fe(III)

0.1 N HCl solution, 42.43 % recovery after 4 cycles

(Dim et al., 2021)

Cr(VI)

0.1 N HCl solution, 48.54 % recovery after 4 cycles

Treated with acetic acid

Fe(III)

0.1 N HCl solution, 39.89 % recovery after 4 cycles

Cr(VI)

0.1 N HCl solution, 40.45 % recovery after 4 cycles

10 Conclusion

Clays are hydrated aluminosilicates of lamellar structure. In nature, clay minerals are often associated with other non-clay substances that can be crystallized (carbonates, quartz, sulfates, organic matter, etc.) or amorphous (amorphous iron hydroxides, silica gels). Due to their physicochemical properties of a high specific surface, swelling, and cation exchange capacity (CEC), clay minerals have very important properties and are widely used in many industrial sectors. In the field of water pollution control, according to various studies reported in this review, different types of natural clay are very effective as adsorbents to remove various types of dyes and heavy metals. According to several studies the illustrated results show that, activated or modified clays have a higher adsorption capacity than raw clays. Therefore, improving the performance of natural clay adsorbents by different modification methods is essential for industrial applications. However, the cost is indeed an important parameter for the comparison and selection of adsorbents. The evaluation of the adsorption capacity of natural clays for the removal of dyes and heavy metals must take into account the properties of the natural clay, the size, nature and shape of the targeted pollutants, the surface defrents modifications performed, as well as the experimental operating conditions. The adsorption mechanism of dyes and heavy metals is mainly related to the specific surface area, ion exchange capacity, electrostatic interactions, hydrogen bonds, and Van Der Waals forces. Raw clays or activated/modified can be regenerated and reused for the adsorption of dyes and heavy metals. For all these points, natural clays, raw or modified, can be considered as good potential adsorbents, less costly and efficient for the elimination of pollutants in wastewater.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohamed El-Habacha: Writing – original draft, review and editing, Youssef Miyah: Review and editing and revision, Salek Lagdali: Review and editing, Guellaa Mahmoudy: Review and editing, Abdelkader Dabagh: Review and editing, Mohamed Chiban: Review and editing, Fouad Sinan: Critical feedback and revision, Soulaiman Iaich: Co-supervision, Writing – original draft, Mohamed Zerbet: Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the Editor and Reviewers for their valuable suggestions related to the redaction of the review.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Journal of the Turkish Chemical Society Section A: Chemistry.. 2021;8:677-692.

- ACS Omega. 2020;5:6834-6845.

- [CrossRef]

- Compos. B Eng.. 2019;162:538-568.

- [CrossRef]

- Chemical Society Section A: Chemistry. 2020:727-744.

- [CrossRef]

- C. R. Chim.. 2019;22:113-125.

- [CrossRef]

- Abidi, N. 2015. PhD Thesis. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01222041.

- Environ. Earth Sci.. 2018;77:218.

- [CrossRef]

- Water Sci. Technol.. 2021;84:1059-1078.

- [CrossRef]

- Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2020;27:14044-14057.

- [CrossRef]

- Desalin. Water Treat.. 2020;178:193-202.

- [CrossRef]

- Akowanou, A. V. O., Aïna, M. P., Groendijk, L., Yao, K. B., 2016. HAL. 72. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03160019.

- Toxics.. 2021;9:42.

- Appl. Sci.. 2021;11:11357.

- [CrossRef]

- Nanomaterials. 2021;11:2789.

- [CrossRef]

- Environ. Technol. Innov.. 2020;18:100794

- J. Chil. Chem. Soc.. 2020;65:4790-4797.

- [CrossRef]

- Appl. Sci.. 2018;8:2302.

- [CrossRef]

- Environmental Advances.. 2021;4:100072

- [CrossRef]

- Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.. 2021;1–26

- [CrossRef]

- J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;329:115579

- [CrossRef]

- J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2019;7:103404

- [CrossRef]

- J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2020;8:104553

- [CrossRef]

- Aoun, M. 2016. PhD thesis, University of the Mentouri brothers of Constantine.

- Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process.. 2021;57:97-111.

- Chemosphere. 2021;276:130079

- [CrossRef]

- SN Appl. Sci.. 2020;2:2042.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Environ. Treat. Tech.. 2020;8:1258-1267.

- Int J Environ Res.. 2020;14:1-14.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Clean. Prod.. 2019;228:778-785.

- [CrossRef]

- Rev. Chim.. 2020;71:37-47.

- Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2020;27:38384-38396.

- [CrossRef]

- Arab. J. Sci. Eng.. 2020;45:205-218.

- [CrossRef]

- Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2021;28:2572-2599.

- [CrossRef]

- Mater. Today:. Proc. 2021

- [CrossRef]

- J. Hazard. Mater.. 2021;415:125656

- [CrossRef]

- Synthesis, Environ Sci Pollut Res.. 2020;27:45767-45774.

- [CrossRef]

- Arab. J. Chem.. 2021;14:103031

- [CrossRef]

- Chemistry Africa.. 2022;375–393

- [CrossRef]

- Inorg. Chem. Commun.. 2020;115:107891

- [CrossRef]

- J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2017;5:5921-5932.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Afr. Earth Sc.. 2019;154:80-88.

- [CrossRef]

- RILEM Technical Letters.. 2022;7:47-57.

- Berthonneau, J. 2013. PhD thesis, University of Aix-Marseille. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00958572.

- J. Mol. Struct.. 2022;1250:131729

- [CrossRef]

- Chemosphere. 2021;284:131263

- [CrossRef]

- Abou-Bekr Belkaid - Tlemcen. 2019 PhD thesis

- Boucheta, A. 2017. PhD Thesis, University Djillali Liabes, Faculty of Sciences Sidi Bel Abbes.

- E3S Web Conf.. 2021;240:02004.

- [CrossRef]

- Polym. Compos.. 2021;42:1648-1658.

- [CrossRef]

- Bouzidi, N. 2012. PhD thesis, Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Saint-Etienne. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00847400.

- Heliyon.. 2020;6:e04691.

- J. Hazard. Mater.. 2019;379:120584

- [CrossRef]

- Caner, L. 2011. PhD thesis, University of Poitiers. (2011). https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00605819.

- Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2020;596:124735

- [CrossRef]

- J. Alloy. Compd.. 2015;647:720-727.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Mol. Struct.. 2019;1179:672-677.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Mol. Struct.. 2021;1223:128944

- [CrossRef]

- Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol.. 2021;18:2323-2335.

- [CrossRef]

- Chemical news.. 2005;285–86:93-98.

- Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol.. 2021;18:1814-1824.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Dispers. Sci. Technol.. 2022;1–10

- [CrossRef]

- Environ. Technol.. 2021;42:2925-2940.

- J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;312:113383

- [CrossRef]

- Delavernhe, L. 2012. PhD thesis, University of Nantes. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00671340.

- Surf. Interfaces. 2020;19:100506

- [CrossRef]

- Arab. J. Chem.. 2021;4:103064

- [CrossRef]

- South African Journal of Chem. Eng.. 2022;40:100-106.

- [CrossRef]

- Resour. Conserv. Recycl.. 2021;168:105271

- [CrossRef]

- J. Mol. Liq.. 2019;290:111139

- [CrossRef]

- J. Saudi Chem. Soc.. 2020;24:527-544.

- [CrossRef]

- Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.. 2021;1–22

- [CrossRef]

- Biointerface Res Appl Chem.. 2021;11:12717-12731.

- J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2021;9:106060

- [CrossRef]

- Cleaner Engineering and Technology.. 2021;4:100209

- [CrossRef]

- Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023

- J. Environ. Earth Sci.. 2014;4:38-46.

- Appl Water Sci. 2019;9:97.

- [CrossRef]

- Mater. Today:. Proc.. 2019;13:866-875.

- [CrossRef]

- Mater. Today:. Proc.. 2021;45:7299-7305.

- [CrossRef]

- Mater. Today:. Proc.. 2021;45:7290-7298.

- [CrossRef]

- Materials Today: Materials Today: Proceedings.. 2022;58:1162-1168.

- [CrossRef]

- Scientific African.. 2021;13:e00960.

- Surf. Interfaces. 2020;21:100754

- [CrossRef]

- Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol.. 2021;36:102140

- [CrossRef]

- IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng.. 2020;928:022030

- [CrossRef]

- RE.. 2021;3

- Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering.. 2017;5:5677-5687.

- [CrossRef]

- Materials.. 2020;13:3600.

- [CrossRef]

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2020;151:355-365.

- [CrossRef]

- Gafoor Dhanasekar, A., Sathees Kumar, Sankaran, Sivaranjani, Sabeena Begum, Zunaithur Rahman, 2021. Materials Today: Proceedings. 37, 2033‑2040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2020.07.500.

- Environmental Nanotechnology Monitoring & Management.. 2020;14:100339

- [CrossRef]

- Appl. Clay Sci.. 2018;165:17-21.

- [CrossRef]

- Pharmaceutics.. 2021;13:1806.

- [CrossRef]

- Arab. J. Chem.. 2015;8:25-31.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Storage Mater.. 2021;44

- [CrossRef]

- European Journal of Engineering and Technology Research.. 2021;6

- Arab. J. Geosci.. 2021;14:1595.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Water Process Eng.. 2021;43:102274

- [CrossRef]

- Environ. Res.. 2020;184:109322

- [CrossRef]

- Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.. 2018;163:365-371.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Hazard. Mater.. 2019;369:780-796.

- [CrossRef]

- Mediterr. J. Chem.. 2019;8:158-167.

- Mor. J. Chem. 2021;9:416-433.

- Appl. Clay Sci.. 2020;185:105412

- [CrossRef]

- Z, Environ. Res.. 2021;194:110685

- [CrossRef]

- Desalin. Water Treat.. 2021;235:251-271.

- Environ. Res.. 2021;197:111050

- [CrossRef]

- Process Saf. Environ. Prot.. 2021;152:441-454.

- [CrossRef]

- Surf. Interfaces. 2020;18:100422

- [CrossRef]

- R. E.k, Food Packaging and Shelf Life.. 2021;30:100727

- [CrossRef]

- J. Pet. Sci. Eng.. 2018;166:476-481.

- [CrossRef]

- Journal of Environmental Treatment Techniques.. 2021;9:218-223.

- J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2021;9:106636

- [CrossRef]

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2020;161:1272-1285.

- [CrossRef]

- Biointerface Res Appl Chem.. 2020;10:5747-5754.

- Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2020;17:2123-2140.

- [CrossRef]

- Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2020;598:124807

- [CrossRef]

- Mater. Res. Express. 2020;7:055507

- [CrossRef]

- Materials Today Sustainability.. 2021;13:100077

- [CrossRef]

- SN Appl. Sci.. 2021;3:856.

- [CrossRef]

- Polymers. 2022;14:164.

- [CrossRef]

- Kouadri, H. 2018. Elaboration, Ph.D. Thesis, University Ferhat Abbas Setif-1. http://dspace.univ-setif.dz:8888/jspui/handle/123456789/3110.

- Monitoring & Management.. 2021;16:100561

- [CrossRef]

- Adv. Sci.. 2021;8:2004036.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;318:114247

- [CrossRef]

- Dyes Pigm.. 2021;190:109322

- [CrossRef]

- Mater. Today:. Proc.. 2021;45:7457-7467.

- [CrossRef]

- Lucas, J. 1962. bulletins and briefs. 23. https://www.persee.fr/doc/sgeol_0080-9020_1962_mon_23_1.

- J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;340:116884

- [CrossRef]

- Arabian Journal of Chemical and Environmental Research.. 2021;8:83-96.

- J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;334:116143

- [CrossRef]

- Geosci. Front.. 2022;13:101151

- [CrossRef]

- Presses univ. de Louvain.. 2012;400

- Scientific World Journal. 2021;2021:e6659902.

- Appl. Clay Sci.. 2009;44:230-236.

- [CrossRef]

- Bulletin of the French Clay Group. 1969;21:1-30.

- Meziti, C. 2016. PhD thesis, University A.Mira-Bejaia, Faculty of Technology.

- Michel, R. 1971. Bulletin of the French Clay Group. 23, 1‑1.

- Journal of the Association of Arab Universities for Basic and Applied Sciences.. 2017;23:20-28.

- [CrossRef]

- Arab Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences.. 2020;27:248-258.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2021;9:106694

- [CrossRef]

- J. Mol. Liq.. 2022;362:119739

- [CrossRef]

- Appl. Sci.. 2021;12:87.

- [CrossRef]

- Crystals. 2020;10:957.

- [CrossRef]

- RSC Adv.. 2018;8:24571-24587.

- [CrossRef]

- J. Pet. Sci. Eng.. 2021;206:109043

- [CrossRef]

- Surf. Interfaces. 2021;26:101412

- [CrossRef]

- J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;319:114356

- C. R. Chim.. 2019;22:105-112.

- J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;344:117822

- [CrossRef]

- Appl Catal B. 2018;227:102-113.

- [CrossRef]

- Awka Journal of Fine and Applied.. 2020;7:117-130.

- Chemistry Research Journal.. 2021;6:157-168.