Translate this page into:

Chemical characterization, antioxidant, antimicrobial, enzyme inhibitory and cytotoxic activities of Illicium lanceolatum essential oils

⁎Corresponding author. tianming.zhao@git.edu.cn (Tianming Zhao),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Illicium lanceolatum is a medicinal and aromatic plant widely distributed in the south of China. The reports on chemical composition and biological activities of its essential oils (EOs) were very limited. In this study, Illicium lanceolatum EOs were extracted by hydro distillation, and analyzed by GC–MS and GC-FID. DPPH radical scavenging assay, ABTS cation radical scavenging assay and ferric reducing/antioxidant power (FRAP) assay were used for antioxidant activity evaluation. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) and minimum microbiocidal concentrations (MMCs) against 9 microorganisms were determined. The inhibitory effects on tyrosinase, α-glucosidase and cholinesterases were evaluated and cytotoxic activities were evaluated using MTT assay. The results revealed 110 identified compounds, with asaricin, eucalyptol, linalool and caryophyllene oxide as major compounds. Eucalyptol was the most abundant compound in the stem, leaf and fruit EOs while asaricin accounted for 50.52 ± 0.33 % in the root EO. Very weak radical scavenging capacities were noticed for all EOs, but the root EO showed moderate antioxidant activity (176.33 ± 4.52 mg TE/g of EO) in the FRAP assay, which could be attributed to asaricin. The root EO displayed better antimicrobial activities than other three EOs, with MIC values as 3.13 mg/mL against three bacteria including Staphylococcus aureus BNCC 186335, Bacillus cereus BNCC 103930 and Listeria monocytogenes BNCC 336877. Camphor and borneol were found to be important antimicrobial compounds. No inhibitory effect on α-glucosidase was found. The leaf EO displayed better acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity (17.79 ± 0.32 mg GE/g of EO) while the root EO showed better tyrosinase (30.34 ± 0.40 mg KAE/g of EO) and butyrylcholinesterase (43.25 ± 1.50 mg GE/g of EO) inhibitory activities. Molecular docking between active compounds and enzymes revealed the main interactions as hydrophobic interaction, hydrogen bond and π-stacking. All EOs displayed weak cytotoxicity to HK-2 cells of normal kidney at six tested concentrations. The leaf EO showed strong anticancer activities to HepG2 cells at the concentration of 500 μg/mL. I. lanceolatum EOs showed promising prospects with possible applications in pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries.

Keywords

Illicium lanceolatum

Essential oil

Antioxidant

Antimicrobial

Enzyme inhibitory

Cytotoxicity

- ABTS

-

2,2′-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)

- AChE

-

acetylcholinesterase

- AE

-

acarbose equivalent

- ATCI

-

acetylthiocholine iodide

- B. cereus

-

Bacillus cereus

- BChE

-

butyrylcholinesterase

- BHT

-

butylated hydroxytoluene

- BTCI

-

butyryl thiocholine iodide

- C. albicans

-

Candida albicans

- DPPH

-

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- DTNB

-

5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)

- E. coli

-

Escherichia coli

- EO

-

essential oil

- FRAP

-

ferric reducing/antioxidant power

- GC-FID

-

gas chromatography-flame ionization detector

- GC–MS

-

gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- GE

-

galanthamine equivalent

- I. lanceolatum

-

Illicium lanceolatum

- KAE

-

kojic acid equivalent

- L. monocytogenes

-

Listeria monocytogenes

- MIC

-

minimum inhibitory concentration

- MMC

-

minimum microbiocidal concentration

- MTT

-

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- P. aeruginosa

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- pNPG

-

p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside

- RI

-

retention index

- S. aureus

-

Staphylococcus aureus

- S. epidermidis

-

Staphylococcus epidermidis

- S. lentus

-

Staphylococcus lentus

- S. typhimurium

-

Salmonella typhimurium

- TE

-

trolox equivalent

- TIC

-

total ion chromatogram

- TPTZ

-

2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine

- Trolox

-

6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

The genus Illicium consists of approximately 40 species which are represented by evergreen trees and shrubs, and 28 of them are distributed in the south, southwest, and east of China (Kubo et al., 2022). The plants of this genus are rich in monoterpenoids, sesquiterpenoids, phenylpropanoids and lignans, and were found to have various biological activities, such as insecticidal, antioxidative, antibacterial, neurotrophic, anti-inflammatory and enzyme inhibitory activities (Liu et al., 2009). Some species of the genus Illicium have been used in traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of traumatic injury, rheumatism and skin inflammation. The fruit of Illicium verum (I. verum) and stem bark of Illicium difengpi are listed officially in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. The fruit of I. verum, known as star anise, could be used for extraction of shikimic acid to produce oseltamivir (Estevez, A.M. and Estevez, R.J., 2012) and is also a commonly-used spice in Chinese and Southeast-Asian food.

Illicium lanceolatum A. C. Smith (I. lanceolatum) is a medicinal and aromatic plant, commonly known as ‘Mangcao’ or ‘Hongduhui’ in Chinese. Its star shaped fruit closely resembles that of I. verum, but it is highly toxic due to the presence of neurotoxic sesquiterpene named anisatin (Mathon et al., 2013). Some analytical methods were established to distinguish these two fruits, such as Vis/NIR hyperspectral imaging combined with chemometrics (Lu et al., 2020) and thermal desorption-GC–MS (Howes et al., 2009). However, its roots and leaves have been used to treat bruises, internal injuries and back pain in folk medicines (Liang et al., 2009). The sterilized aqueous solution produced from the root or branch of I. lanceolatum could be used as injection to relieve pain (Gao et al., 2020). The past decade has seen the extensive studies on the chemical compounds from the fruits, leaves and roots of I. lanceolatum. In particular, sesquiterpenoids have drawn a lot of interest, including seco-prezizaane-type (Liu et al., 2019, 2020; Nie et al., 2021, 2022), germacrane-type (Kubo et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2014), tetranor and santalane-type sesquiterpenoids (Kubo et al., 2015). Essential oils (EOs) (Huang et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2012), monoterpenes (Liu et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2014), flavonoids (Li et al., 2014) and phenylpropanoids (Gui et al., 2014; Nie et al., 2022) were also reported in different parts of I. lanceolatum. In previous studies, the compounds of I. lanceolatum have shown various biological activities, including anti-inflammatory (Gui et al., 2014; Liang et al., 2012), antimicrobial (Kubo et al., 2015) and neuroprotection activities (Liu et al., 2019). In addition to medicinal use, I. lanceolatum can also be used as an ornamental plant. As the demand for this plant is increasing, I. lanceolatum has been cultivated in some provinces in China.

Essential oils are natural oily liquids characterized by unique odors. Due to their many beneficial effects, including antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and enzyme inhibitory properties, essential oils have found increasing uses in pharmaceutical, food and cosmetic industries. Because oxidation can damage various biological molecules and subsequently lead to many diseases, antioxidant activity is one of the mostly studied topics in essential oil research (Shaaban et al., 2012). Antioxidants have been used for the treatment of many diseases to prevent oxidative damage. Antioxidant activities of numerous essential oils have been evaluated and the results have shown that essential oils are good natural sources of antioxidants, such as thyme essential oil (Wei and Shibamoto, 2010). Pathogenic microorganisms cause a lot of diseases in human and lead to natural spoilage in foods. Antibiotics and other synthetic antimicrobial chemicals have been used to control the growth of these microorganisms. However, overuse of these antimicrobial agents could lead to drug resistance. Natural antimicrobial agents including essential oils from medicinal and aromatic plants as safe alternatives have received much attention. For example, oregano essential oil has been used as food additive in food products due to its obvious antimicrobial and antioxidant activity (Rodriguez-Garcia et al., 2016). Enzymes are important targets for developing drugs and evaluation of enzyme inhibition activity could contribute to discovery of potential lead compounds for related diseases. Essential oils have shown various enzyme inhibitory effects in previous studies, such as tyrosinase (Salem et al., 2022), α-glucosidase (Ahamad, 2021) and cholinesterases (Burcul et al., 2020). As one of the biggest causes of mortality in humans, cancer has received much more attention from researchers. Many essential oils have been reported to play an important role in cancer prevention and treatment, and various mechanisms have been unveiled, such as antioxidant, antiproliferative, enhancement of immune function, and synergistic mechanism of volatile constituents (Bhalla et al., 2013).

The different parts of I. lanceolatum, including roots, stems, leaves and fruits, are rich in essential oils. However, the studies on the chemical composition and biological activities of I. lanceolatum EOs are quite limited up to date. The chemical compositions of essential oils from the roots, leaves and fruits of I. lanceolatum originated in Jiangxi province of China were reported in previous studies (Huang et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2012), antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory properties of the root EO were evaluated. Cineole (24.5 %) and D-limonene (18.3 %) were found to be the major components of the I. lanceolatum fruit EO. The leaf EO mainly contained linalool (16.2 %), elemicin (14.9 %) and cineole (14.8 %) while myristicin (17.6 %), α-asarone (17.2 %) and methyl isoeugenol (11.2 %) were the major components of the root EO (Huang et al., 2012). To the best of our knowledge, there is no report on the antioxidant, antimicrobial, enzyme inhibitory and cytotoxic activities of I. lanceolatum EOs.

As second metabolites produced in the plants, chemical composition of essential oils could be affected by environmental conditions, geographic variations, physiological variations and other factors (Figueiredo et al., 2008). The chemical components of essential oils of the same species from different geographical areas may differ significantly. I. lanceolatum collected in the previous studies was from Jiangxi province. The investigation on chemical composition of I. lanceolatum EOs from other locations could contribute to a better understanding of the chemical variety of this species' essential oils.

The current research has been carried out to investigate the chemical composition of essential oils from the roots, stems, leaves and fruits of I. lanceolatum and to evaluate their antioxidant, antimicrobial, enzyme inhibitory and cytotoxic activities. Nine major compounds in the root EO were further evaluated for their antioxidant, antimicrobial and enzyme inhibitory activities. The chemical composition of the stem EO, antioxidant, antimicrobial, enzyme inhibitory and cytotoxic activities of I. lanceolatum EOs were firstly reported in this study. Our results could bring some insights for applications of I. lanceolatum EOs into pharmaceutical and cosmetical industries.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant materials

The roots, stems, leaves and fruits of I. lanceolatum were collected in August 2022 in a village near Guiyang (Latitude 26˚41΄5˝N, longitude 106˚30΄41˝E, altitude 1241 m a.s.l.) and naturally dried at room temperature in the shade for about three weeks before extraction of essential oils. The moisture contents in the roots, stems, leaves and fruits of I. lanceolatum were determined as 7.04 ± 0.15 %, 6.58 ± 0.09 %, 5.42 ± 0.12 % and 6.33 ± 0.08 %, respectively. Associate Prof. Yazhou Zhang from Guizhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine made the identification of this species according to the Flora of China. Voucher specimens (MC015) of this plant were placed at Guizhou Institute of Technology.

2.2 Reagents

DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) and a mixed standard of n-alkanes C7-C30 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. ABTS [2,2′-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic Acid)], TPTZ(2,4,6-Tripyridyl-s-triazine) and Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid) were from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology company. Amphotericin B, gentamycin sulfate, tyrosinase from mushroom, levodopa, kojic acid, p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (pNGP), acarbose, α-glucosidase from yeast, acetylthiocholine iodide (ATCI), butyryl thiocholine iodide (BTCI), 5,5′-Dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), acetylcholinesterase (AChE) from electric eel, butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) from horse serum and galanthamine were purchased from Shanghai Yuanye. For identification and activity evaluation of nine compounds in the root EO, terpinen-4-ol (95 %), linalool (98 %), α-terpineol (96 %) and borneol (98 %) were from Shanghai Yuanye; eucalyptol (99 %), camphene (96 %) and camphor (96 %) were from Shanghai Rhawn; estragole (98 %) was from Shanghai Aladdin; asaricin (98 %) was from Sichuan Weikeqi Biotech.

2.3 Extraction of essential oils

The dried roots, stems and leaves were firstly chopped into small pieces and then ground using a grinder. The dried fruits were directly ground. The powder of each organ was divided into three parts. The hydrodistillations of dry roots (300 g), stems (400 g), leaves (400 g) and fruits (150 g) of I. lanceolatum were performed in Clevenger-type apparatus for 5 h, according to the method listed in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia. The experiments were carried out in triplicates for each organ of I. lanceolatum to obtain three essential oils. 12 essential oils obtained in total were stored at −20 ℃ for further GC–MS and GC-FID analysis. For biological activity evaluation, three essential oils obtained from each organ were combined together to obtain one essential oil for each organ.

2.4 GC–MS and GC-FID analysis

The 12 essential oils from different parts of I. lanceolatum were diluted in n-hexane (1:50, v/v) and analyzed using a TG-5MS capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) on GC–MS (Shimadzu, TQ8040 NX) and GC (Thermo Scientific, Trace 1310) systems, according to the previous method (Zhao et al., 2021) with slight modifications. For GC–MS analysis, column temperature was initially maintained at 50 °C for 3 min, and raised to 140 ℃ at 3 ℃/min and kept for 2 min; then heated to 190 ℃ at 2 ℃/min and maintained for 2 min; finally raised up to 220 ℃ at 10 ℃/min. The carrier gas was helium with a flow rate of 1 mL/min and the injection volume was 1 μL in split mode (1:20). The temperature of injection port, interface and ion source was all set at 250 °C. The mass range was 45–550. A mixed standard of n-alkanes (C7-C30) was analyzed under the same conditions. Identification of each component in the I. lanceolatum EOs was based on the comparison of its calculated retention index and experimental mass spectra with those published in the literature (Adams, 2007) and NIST libraries. The quantification of essential oil components was carried out on GC with FID detector. The column and temperature programming conditions were the same as the GC–MS system. Nitrogen was used as the carrier gas with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. 1 μL of sample solution was injected with the split ratio as 1:20. The temperature of injection port and detector was 250 °C. The identification of asaricin, borneol, camphor, eucalyptol, camphene, estragole, terpinen-4-ol, linalool and α-terpineol were further confirmed by injection of authentic compounds on GC. The relative percentage (%) of each component in essential oils was based on peak area normalization of GC chromatogram.

2.5 Antioxidant activity assays

Three different methods, including DPPH radical scavenging assay, ABTS cation radical scavenging assay and ferric reducing/antioxidant power (FRAP) assay, were employed to evaluate the antioxidant activities of I. lanceolatum EOs. The experiments were conducted according to the previously reported method (Zhao et al., 2021). In brief, essential oil solution of 20 mg/mL in methanol was firstly prepared. For DPPH assay, 6 mL of DPPH in methanol (6 × 10-5 mol/L) was mixed with 150 μL of essential oil solution. The mixed solution was put in the darkness for 30 min and then measured at 515 nm on the UV–vis spectrophotometer (UH5300, HITACHI). For ABTS assay, 50 μL of essential oil solution was mixed with 4 mL of diluted ABTS solution. After 6 min of reaction, the absorbance of mixture was recorded at 734 nm. For FRAP assay, 150 µL of essential oil solution was mixed with 450 µL of methanol, and then 4.5 mL of FRAP reagent. The mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37 ℃ and the absorbance was recorded at 593 nm. The antioxidant activities of nine major compounds in the root EO, including asaricin, borneol, camphor, eucalyptol, camphene, estragole, terpinen-4-ol, linalool and α-terpineol, were further evaluated using FRAP assay. The methanol solutions of Trolox with known concentrations ranging from 25 to 250 mg/L were used for calibration. The antioxidant activity was expressed in mg Trolox equivalent (TE)/g of EO. BHT (butylated hydroxytoluene), a synthetic antioxidant, was used as positive control.

2.6 Antimicrobial activity assays

The pathogenic microorganisms including 5 gram-positive bacteria, 3 gram-negative bacteria and 1 yeast, were purchased from BeNa Culture Collection company (Beijing, China). Bacillus cereus BNCC 103930 (B. cereus), Listeria monocytogenes BNCC 336877 (L. monocytogenes), Staphylococcus aureus BNCC 186335 (S. aureus), Staphylococcus epidermidis BNCC 102555 (S. epidermidis), Staphylococcus lentus BNCC 336683 (S. lentus), Escherichia coli BNCC 133264 (E. coli), Pseudomonas aeruginosa BNCC 337005 (P. aeruginosa) and Salmonella typhimurium BNCC 108207 (S. typhimurium) were cultured in Mueller-Hinton Broth medium. Candida albicans BNCC 186382 (C. albicans) was grown in yeast maltose medium.

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) and minimum microbiocidal concentrations (MMCs) of I. lanceolatum EOs were determined by the previous method with some modifications (Zhao et al., 2021). The concentration of microbial strain suspension was diluted to 105 CFU/mL for bacteria or 103 CFU/mL for yeast. 120 μL of essential oil solutions was firstly added and then serial concentrations were obtained by 2-fold dilution method. After that, 60 μL of diluted strain suspension was added. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 16–24 h for the bacteria and at 28 °C for 48 h for the yeast. The lowest concentrations of essential oils corresponding to the wells in which the mixture remained clear were the MICs. After obtaining the MIC results, 60 μL of the suspension from the wells in which there was no visible growth was spread on nutrient agar plates. For the bacteria, the Petri dishes were incubated at 37 °C for 16–24 h, and for the yeast, they were at 28 °C for 48 h. The lowest essential oil concentrations of the MIC wells in which strains failed to grow were recorded as MMCs. The gentamycin sulfate and amphotericin B were used as positive controls for antibacterial and antifungal tests, respectively. The MICs and MMCs of nine compounds against S. aureus, B. cereus and L. monocytogenes, including asaricin, borneol, camphor, eucalyptol, camphene, estragole, terpinen-4-ol, linalool and α-terpineol, were further determined.

2.7 Enzyme inhibitory activity assays

Tyrosinase, α-glucosidase, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity assays of I. lanceolatum EOs were conducted to evaluate their whitening effect, anti-diabetes effect and improvement effect on neurodegenerative diseases. Essential oil solutions in ethanol of 50 mg/mL were firstly prepared and diluted with buffer solution to the concentrations of 4, 2 and 1 mg/mL before the tests. All the enzymes and substrates were prepared daily, and kept in the ice bath for subsequent experiments. The inhibition effects on tyrosinase and butyrylcholinesterase of nine compounds including asaricin, borneol, camphor, eucalyptol, camphene, estragole, terpinen-4-ol, linalool and α-terpineol were further evaluated.

Tyrosinase inhibition activity assay was conducted according to the previous method (Sharmeen Jugreet et al., 2021) with some modifications. In brief, 110 μL of phosphate buffer (pH6.8) was mixed with 40 μL of tyrosinase solution (110 U/mL) and 10 μL of essential oil solution in a 96-well microplate. After 15 min of incubation at 37 ℃, 40 μL of levodopa (5 mM) was added to start the reaction. After an additional 10 min of incubation at 37 ℃, absorbance was immediately measured at 492 nm using microplate reader (DNM-9606, Perlong, Beijing). A blank solution without essential oil was tested using the same procedure and then inhibition percentages of essential oils were calculated. Kojic acid was used as positive control and the tyrosinase inhibitory activities of essential oils were expressed as mg kojic acid equivalents (KAE)/g of EO.

α-glucosidase inhibitory activity assay was based on the previous method (Hong et al., 2021) with some modifications. 80 μL of phosphate buffer (pH6.8) was mixed with 20 μL of α-glucosidase solution (1 U/mL) and 10 μL of essential oil solution in a 96-well microplate. After 15 min of incubation at 37 ℃, 10 μL of p-NPG (1 mM) was added to initiate the reaction. The reaction lasted for 20 min and stopped by adding 80 μL of sodium carbonate solution (0.2 M). The absorbances were recorded at 405 nm using microplate reader. A blank solution without essential oil was tested using the same method. Acarbose was used as positive control and the results were expressed as mg acarbose equivalents (AE)/g of EO.

Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity assays were carried out following the previous method (Hong et al., 2021) with modifications. 140 μL or 120 μL of Tris-HCl buffer (pH8.0) was firstly added to a 96-well microplate, followed by the addition of 20 μL of DTNB solution (1 mM), 10 μL of essential oil solution and 10 μL of acetylcholinesterase solution (2 U/mL) or 30 μL of butyrylcholinesterase solution (2 U/mL). After 15 min of incubation at 37 ℃, 20 μL of ATCI (1 mM) or BTCI (1 mM) was added to start the reaction. After an additional 15 min of incubation at 37 ℃, absorbance was immediately measured at 405 nm. A blank solution without essential oil was tested using the same method. Galanthamine was used as positive control and the results were expressed as mg galanthamine equivalents (GE)/g of EO.

2.8 Cytotoxic activity assays

Cytotoxic activities of I. lanceolatum EOs were evaluated by using the MTT assay against three cell lines, including HK-2 cells (proximal tubular cell line of normal kidney), HepG2 cells (human liver carcinoma cell line) and MCF-7 cells (human breast cancer cell line). Cytotoxicity assays were conducted according to the previous method (Zhang et al., 2017) with some modifications. Essential oil solutions in DMSO of 100 mg/mL were firstly prepared and six final concentrations (500, 200, 100, 50, 20 and 2 μg/mL) were evaluated for each essential oil. The tested cells were cultured in a humidified 5 % CO2 atmosphere. When the cells were cultivated to the logarithmic growth stage, they were seeded at 1 × 104 cells/well in 100 µL of growth medium and incubated at 37 ℃ for 24 h. The microplates were treated with the essential oil solutions and incubated for 24 h. Then, 20 µL of MTT solution (5 g/L) was added to each well and the microplate were incubated for an additional 4 h. 100 µL of DMSO was added to each well. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm. The percentages of cell viability were calculated by the formula: cell viability (%) = [Asample/A control] × 100 %. Doxorubicin was used as the positive control.

2.9 Molecular docking study

Molecular docking studies of selected compounds with better enzyme inhibitory activities in the root EO were carried out according to a previous method (Sun et al., 2023) with some modifications. The interactions between these compounds and enzymes were simulated using AutoDock Vina 1.1.2 (Trott and Olson, 2010). The protein structures of tyrosinase (Mauracher et al., 2014) and butyrylcholinesterase (Knez et al., 2018) were obtained from the Protein Data Bank database, with PDB ID codes as 4OUA and 6F7Q, respectively. Docking results were given as binding affinity values (kcal/mol). PyMOL and online tool named Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler (PLIP) (Salentin et al., 2015) were used to analyze the interactions between the ligands and the active sites of enzymes.

2.10 Statistical analysis

Hydrodistillation, GC–MS and GC-FID analysis of essential oils were performed in triplicates. For antioxidant, antimicrobial and cytotoxic activity assays, three parallel experiments were performed. For enzyme inhibitory activity assays, four parallel experiments were performed in a 96-well plate. The data were expressed as the mean ± SD. Statistical analysis was performed by use of SPSS 25.0 software. One-way ANOVA analysis was used to evaluate the differences among samples and statistical significance is indicated by a value of p < 0.05.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Chemical composition of I. lanceolatum EOs

I. lanceolatum EOs were light yellow oily liquids. Essential oil yields in different parts of I. lanceolatum ranged from 0.09 % to 1.02 %. The leaves showed the highest essential oil yield (1.02 ± 0.05 %), followed by the fruits (0.30 ± 0.02 %), stems (0.21 ± 0.01 %) and roots (0.09 ± 0.01 %). The results seemed to be much lower than the previous studies (Huang et al., 2012; Liang et al., 2012) in which essential oil yields in the roots and fruits were 0.31 ± 0.03 % and 1.37 ± 0.11 %, respectively.

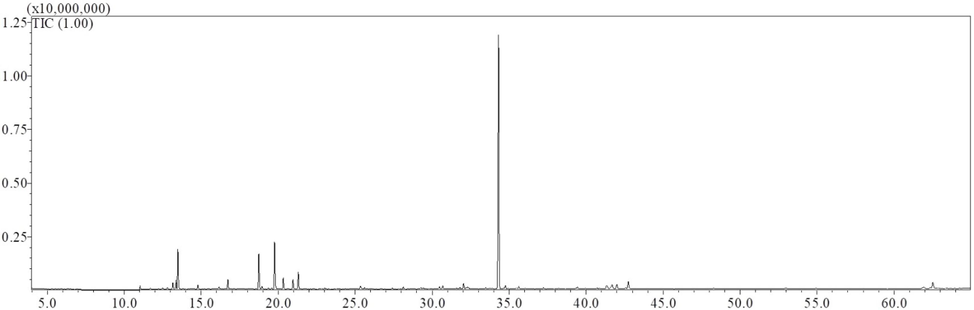

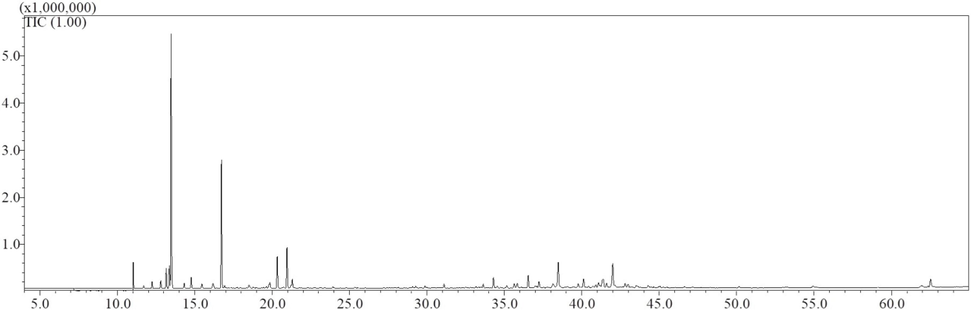

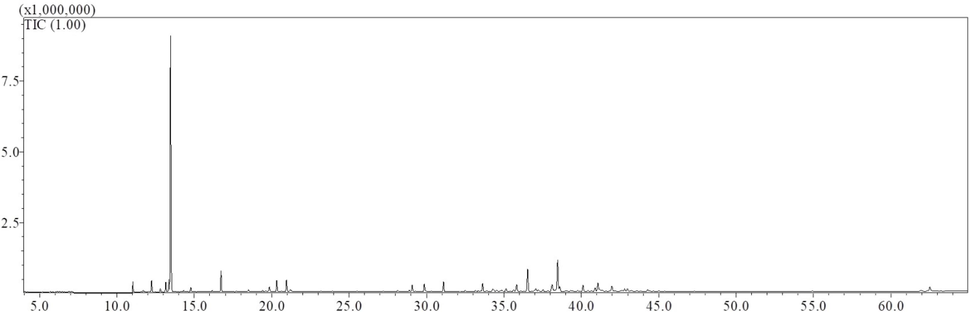

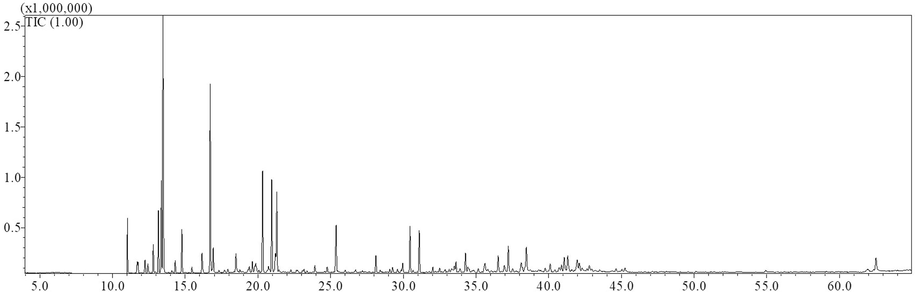

Total ion chromatograms of the root EO, stem EO, leaf EO and fruit EO could be seen in Figs. 1-4. Chemical composition of these four EOs were presented in Table 1. In the essential oils from the roots, stems, leaves and fruits, 45, 63, 57 and 82 chemical compounds were identified, accounting for 91.85 %, 93.19 %, 94.14 % and 92.62 % of the total composition of the essential oils, respectively. The major compounds in the root EO were asaricin (50.52 %), borneol (7.01 %), camphor (5.71 %), eucalyptol (5.44 %) and camphene (3.29 %). The stem EO had eucalyptol (27.63 %), linalool (14.42 %), caryophyllene oxide (6.02 %), α-cadinol (5.30 %) and α-terpineol (4.11 %) as the major compounds. The major compounds in the leaf EO included eucalyptol (42.42 %), caryophyllene oxide (9.77 %), α-calacorene (3.77 %), linalool (3.35 %) and caryophylla-4(12),8(13)-dien-5-ol (3.08 %), while the dominant compounds in the fruit EO were eucalyptol (12.23 %), linalool (10.22 %), terpinen-4-ol (5.02 %), α-terpineol (4.41 %) and α-pinene (4.32 %).In terms of chemical structure, oxygenated monoterpenes dominated in the stem, leaf and fruit EOs, representing 51.84 %, 51.06 % and 40.93 % of the total composition, respectively. However, the most abundant compound in the root EO was asaricin, a phenylpropanoid compound which accounted for 50.52 %. RI.c.: retention index calculated against n-alkane series; RI.l: retention index from literature; MS: mass spectrum; S: identification of chemical compounds by injection their standards on GC; EO: essential oil; nd: not detected.

Total Ion Chromatogram of the root EO of I. lanceolatum.

Total Ion Chromatogram of the stem EO of I. lanceolatum.

Total Ion Chromatogram of the leaf EO of I. lanceolatum.

Total Ion Chromatogram of the fruit EO of I. lanceolatum.

No.

Compound

RI.c

RI.l

Relative percentage(%)

Identification

Root EO

Stem EO

Leaf EO

Fruit EO

1

tricyclene

921

921

0.43 ± 0.01

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

2

α-thujene

926

924

0.03 ± 0.00

0.10 ± 0.00

0.14 ± 0.01

nd

MS, RI

3

α-pinene

932

932

0.94 ± 0.01

2.64 ± 0.04

2.18 ± 0.03

4.32 ± 0.02

MS, RI

4

camphene

947

946

3.29 ± 0.05

0.16 ± 0.00

0.11 ± 0.00

0.21 ± 0.01

MS, RI, S

5

sabinene

972

969

0.15 ± 0.00

0.62 ± 0.01

1.23 ± 0.02

0.36 ± 0.01

MS, RI

6

β-pinene

975

974

0.49 ± 0.01

2.83 ± 0.05

1.53 ± 0.02

3.43 ± 0.13

MS, RI

7

myrcene

991

988

0.17 ± 0.00

0.29 ± 0.01

0.26 ± 0.00

0.54 ± 0.01

MS, RI

8

dehydroxy-trans-linalool oxide

992

991

nd

nd

nd

0.38 ± 0.01

MS, RI

9

α-phellandrene

1003

1002

nd

0.53 ± 0.01

1.28 ± 0.02

0.49 ± 0.02

MS, RI

10

dehydroxy-cis-linalool oxide

1007

1006

nd

nd

nd

0.40 ± 0.01

MS, RI

11

α-terpinene

1016

1014

0.18 ± 0.01

0.55 ± 0.01

0.31 ± 0.01

0.94 ± 0.03

MS, RI

12

p-cymene

1023

1020

0.63 ± 0.01

1.44 ± 0.03

1.01 ± 0.01

2.16 ± 0.07

MS, RI

13

β-phellandrene

1027

1025

0.92 ± 0.03

1.34 ± 0.01

0.64 ± 0.03

3.60 ± 0.09

MS, RI

14

eucalyptol

1030

1026

5.44 ± 0.09

27.63 ± 0.49

42.42 ± 0.66

12.23 ± 0.19

MS, RI, S

15

2-heptyl acetate

1043

1038

nd

nd

nd

0.10 ± 0.01

MS, RI

16

(E)-β-ocimene

1048

1044

nd

0.38 ± 0.01

0.13 ± 0.00

0.46 ± 0.02

MS, RI

17

γ-terpinene

1058

1054

0.48 ± 0.01

0.93 ± 0.01

0.56 ± 0.01

1.76 ± 0.05

MS, RI

18

cis-linalool oxide

1072

1067

nd

0.29 ± 0.01

0.04 ± 0.01

0.19 ± 0.01

MS, RI

19

terpinolene

1087

1086

0.26 ± 0.00

0.57 ± 0.01

0.18 ± 0.00

0.95 ± 0.02

MS, RI

20

linalool

1100

1095

1.47 ± 0.01

14.42 ± 0.20

3.35 ± 0.04

10.22 ± 0.25

MS, RI, S

21

hotrienol

1104

1101

nd

0.24 ± 0.01

nd

1.32 ± 0.04

MS, RI

22

α-fenchol

1112

1114

nd

nd

nd

0.09 ± 0.01

MS, RI

23

cis-p-menth-2-en-1-ol

1121

1118

nd

0.10 ± 0.00

nd

0.15 ± 0.01

MS, RI

24

α-campholenal

1125

1122

nd

nd

nd

0.14 ± 0.00

MS, RI

25

trans-pinocarveol

1137

1135

nd

0.39 ± 0.01

0.35 ± 0.01

1.09 ± 0.02

MS, RI

26

camphor

1142

1141

5.71 ± 0.03

0.07 ± 0.00

nd

0.14 ± 0.00

MS, RI, S

27

camphene hydrate

1147

1145

0.37 ± 0.01

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

28

nerol oxide

1155

1154

nd

nd

nd

0.07 ± 0.01

MS, RI

29

isoborneol

1156

1155

0.12 ± 0.00

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

30

sabina ketone

1157

1154

nd

0.06 ± 0.00

0.18 ± 0.02

0.37 ± 0.01

MS, RI

31

pinocarvone

1161

1160

nd

0.13 ± 0.01

0.13 ± 0.01

0.51 ± 0.01

MS, RI

32

borneol

1164

1165

7.01 ± 0.02

0.26 ± 0.01

nd

0.24 ± 0.01

MS, RI, S

33

δ-terpineol

1166

1162

nd

0.45 ± 0.01

0.75 ± 0.02

0.50 ± 0.01

MS, RI

34

terpinen-4-ol

1176

1174

1.59 ± 0.01

3.10 ± 0.04

1.63 ± 0.02

5.02 ± 0.06

MS, RI, S

35

4-methylacetophenone

1183

1181

nd

0.06 ± 0.01

0.14 ± 0.00

0.09 ± 0.01

MS, RI

36

cryptone

1185

1183

nd

0.11 ± 0.01

nd

0.29 ± 0.01

MS, RI

37

trans-isocarveol

1187

1187

nd

nd

0.04 ± 0.00

0.09 ± 0.00

MS, RI

38

α-terpineol

1190

1186

1.34 ± 0.01

4.11 ± 0.03

1.70 ± 0.02

4.41 ± 0.06

MS, RI, S

39

myrtenal

1195

1195

nd

0.37 ± 0.03

0.40 ± 0.01

1.08 ± 0.03

MS, RI

40

estragole

1197

1195

2.04 ± 0.01

0.69 ± 0.03

nd

3.20 ± 0.04

MS, RI, S

41

trans-carveol

1218

1215

nd

0.05 ± 0.00

nd

0.14 ± 0.00

MS, RI

42

cis-p-mentha-1(7),8-dien-2-ol

1227

1227

nd

nd

nd

0.26 ± 0.01

MS, RI

43

thymol methyl ether

1235

1232

0.09 ± 0.00

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

44

cuminaldehyde

1239

1238

nd

nd

0.10 ± 0.00

0.16 ± 0.01

MS, RI

45

geraniol

1255

1249

nd

0.19 ± 0.01

nd

0.55 ± 0.01

MS, RI

46

phellandral

1273

1272

nd

nd

nd

0.26 ± 0.00

MS, RI

47

bornyl acetate

1286

1284

0.38 ± 0.00

0.04 ± 0.00

0.04 ± 0.01

nd

MS, RI

48

safrole

1287

1285

nd

nd

nd

2.01 ± 0.03

MS, RI

49

p-cymen-7-ol

1290

1289

nd

nd

0.11 ± 0.01

nd

MS, RI

50

thymol

1292

1289

0.10 ± 0.00

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

51

carvacrol

1301

1298

nd

nd

nd

0.06 ± 0.00

MS, RI

52

δ-terpinyl acetate

1317

1316

nd

nd

nd

0.16 ± 0.00

MS, RI

53

α-terpinyl acetate

1349

1346

0.29 ± 0.01

nd

nd

0.86 ± 0.02

MS, RI

54

α-longipinene

1350

1350

nd

0.07 ± 0.00

0.19 ± 0.01

nd

MS, RI

55

cyclosativene

1368

1369

nd

nd

0.15 ± 0.01

nd

MS, RI

56

α-ylangene

1372

1373

nd

0.13 ± 0.00

0.89 ± 0.01

0.13 ± 0.01

MS, RI

57

α-copaene

1376

1374

0.17 ± 0.01

0.15 ± 0.00

0.05 ± 0.00

0.23 ± 0.01

MS, RI

58

geranyl acetate

1384

1379

nd

nd

nd

0.21 ± 0.00

MS, RI

59

sativene

1390

1390

nd

0.25 ± 0.01

1.16 ± 0.02

0.14 ± 0.01

MS, RI

60

β-elemene

1392

1389

nd

nd

nd

0.47 ± 0.01

MS, RI

61

methyleugenol

1404

1403

0.27 ± 0.01

nd

nd

1.88 ± 0.05

MS, RI

62

α-barbatene

1409

1407

0.56 ± 0.00

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

63

β-caryophyllene

1419

1418

nd

0.43 ± 0.01

1.48 ± 0.02

2.28 ± 0.06

MS, RI

64

cis-thujopsene

1431

1429

0.14 ± 0.00

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

65

γ-elemene

1436

1434

0.24 ± 0.01

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

66

β-barbatene

1442

1440

0.91 ± 0.01

nd

nd

0.31 ± 0.01

MS, RI

67

prezizaene

1446

1444

0.27 ± 0.01

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

68

α-guaiene

1450

1445

0.11 ± 0.01

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

69

α-humulene

1453

1452

nd

0.07 ± 0.01

0.13 ± 0.01

0.36 ± 0.01

MS, RI

70

9-epi-(E)-caryophyllene

1460

1464

nd

0.09 ± 0.01

nd

nd

MS, RI

71

cis-muurola-4(14),5-diene

1462

1465

nd

nd

nd

0.23 ± 0.01

MS, RI

72

cadina-1(6),4-diene

1472

1475

nd

nd

nd

0.27 ± 0.01

MS, RI

73

eudesma-2,4,11-triene

1473

1479

nd

0.14 ± 0.01

0.11 ± 0.02

nd

MS, RI

74

β-chamigrene

1476

1476

0.16 ± 0.01

nd

nd

0.12 ± 0.01

MS, RI

75

α-amorphene

1480

1483

nd

0.42 ± 0.02

1.39 ± 0.07

0.55 ± 0.02

MS, RI

76

β-selinene

1486

1489

nd

nd

0.10 ± 0.00

0.28 ± 0.01

MS, RI

77

α-selinene

1495

1498

nd

nd

nd

1.16 ± 0.05

MS, RI

78

asaricin or sarisan

1496

1495

50.52 ± 0.33

0.16 ± 0.01

0.46 ± 0.01

nd

MS, RI, S

79

epizonarene

1499

1501

nd

nd

nd

0.47 ± 0.02

MS, RI

80

(Z)-α-bisabolene

1503

1506

0.12 ± 0.00

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

81

cuparene

1506

1504

0.51 ± 0.01

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

82

δ-amorphene

1507

1511

nd

nd

0.27 ± 0.00

0.18 ± 0.02

MS, RI

83

β-bisabolene

1509

1511

0.12 ± 0.01

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

84

γ-cadinene

1513

1513

nd

nd

nd

0.25 ± 0.01

MS, RI

85

α-dehydro-ar-himachalene

1514

1516

nd

0.33 ± 0.01

0.53 ± 0.03

nd

MS, RI

86

myristicin

1520

1517

0.15 ± 0.00

nd

nd

nd

MS, RI

87

δ-cadinene

1523

1522

0.36 ± 0.00

0.54 ± 0.00

0.29 ± 0.02

0.92 ± 0.04

MS, RI

88

γ-dehydro-ar-himachalene

1527

1530

nd

0.56 ± 0.00

1.12 ± 0.00

0.18 ± 0.01

MS, RI

89

cis-calamenene

1532

1528

nd

nd

nd

0.08 ± 0.01

MS, RI

90

α-calacorene

1542

1544

nd

1.59 ± 0.01

3.77 ± 0.05

0.93 ± 0.05

MS, RI

91

elemicin

1556

1555

0.20 ± 0.01

0.92 ± 0.03

0.97 ± 0.01

1.47 ± 0.07

MS, RI

92

β-calacorene

1563

1564

nd

0.11 ± 0.02

0.32 ± 0.01

0.27 ± 0.02

MS, RI

93

himachalene epoxide

1575

1578

nd

1.15 ± 0.02

1.99 ± 0.02

1.01 ± 0.05

MS, RI

94

spathulenol

1576

1577

0.18 ± 0.01

nd

nd

0.15 ± 0.02

MS, RI

95

caryophyllene oxide

1582

1582

nd

6.02 ± 0.04

9.77 ± 0.07

2.85 ± 0.14

MS, RI

96

β-oplopenone

1608

1607

nd

0.75 ± 0.03

nd

0.30 ± 0.03

MS, RI

97

muurola-4,10(14)-dien-1-ol

1615

1615

nd

1.74 ± 0.03

1.31 ± 0.01

0.96 ± 0.10

MS, RI

98

α-corocalene

1622

1622

nd

0.19 ± 0.01

0.17 ± 0.01

0.21 ± 0.01

MS, RI

99

1-epi-cubenol

1627

1627

0.18 ± 0.01

0.25 ± 0.01

nd

0.40 ± 0.04

MS, RI

100

caryophylla-4(12),8(13)-dien-5-ol

1634

1639

nd

1.57 ± 0.01

3.08 ± 0.02

2.08 ± 0.11

MS, RI

101

6-methyl-6-(3-methylphenyl)-heptan-2-one

1637

1639

nd

0.30 ± 0.01

0.36 ± 0.01

nd

MS, RI

102

τ-cadinol

1639

1638

1.35 ± 0.08

nd

nd

1.74 ± 0.10

MS, RI

103

τ-muurolol

1640

1640

nd

2.27 ± 0.04

nd

nd

MS, RI

104

α-muurolol

1645

1644

nd

0.87 ± 0.02

nd

nd

MS, RI

105

α-cadinol

1653

1652

1.41 ± 0.07

5.30 ± 0.02

1.37 ± 0.01

1.29 ± 0.06

MS, RI

106

alloaromadendrene oxide

1655

1650

nd

0.60 ± 0.02

0.33 ± 0.01

1.47 ± 0.10

MS, RI

107

allohimachalol

1659

1661

nd

nd

nd

0.57 ± 0.03

MS, RI

108

cis-calamenen-10-ol

1666

1660

nd

nd

0.38 ± 0.00

nd

MS, RI

109

cadalene

1673

1675

nd

0.58 ± 0.00

0.61 ± 0.01

0.22 ± 0.01

MS, RI

110

10-nor-calamenen-10-one

1699

1702

nd

0.50 ± 0.03

0.45 ± 0.04

nd

MS, RI

Compounds identified

45

63

57

82

Total identified (%)

91.85

93.19

94.14

92.62

Monoterpene hydrocarbons (%)

7.97

12.38

9.56

19.22

Oxygenated monoterpenes (%)

23.91

51.84

51.06

40.93

Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons (%)

3.67

5.65

12.73

10.24

Oxygenated sesquiterpenes (%)

3.12

20.82

18.59

12.82

Others (%)

53.18

2.50

2.20

9.41

A total of 110 chemical compounds were identified, but only 18 compounds existed in all four essential oils. These 18 compounds accounted for 19.49 %, 67.54 %, 59.79 % and 54.06 % in the root, stem, leaf and fruit EOs, respectively. Five compounds, including eucalyptol, linalool, terpinen-4-ol, α-terpineol and α-cadinol, had the relative percentages of more than 1 % in all four essential oils and could be regarded as representative compounds in I. lanceolatum EOs. In particular, eucalyptol was the most abundant compound in the stem, leaf and fruit EOs. As the most abundant compound in the root EO, asaricin accounted for less than 1 % in the stem and leaf EOs, and even not detected in the fruit EO. Therefore, there were more differences between the root EO and other three EOs.

Of four EOs of I. lanceolatum, the chemical composition of the stem EO was firstly reported. The previous study (Huang et al., 2012) reported myristicin (17.6 %), α-asarone (17.2 %) and methyl isoeugenol (11.2 %) as the major compound in the root EO, which was quite different from our results. α-asarone was not detected and myristicin accounted for only 0.15 % in the current research. However, eucalyptol or 1,8-cineole (24.5 %) was previously reported as the most abundant compound in the fruit EO (Huang et al., 2012), which were in accordance with our results. For leaf EO, linalool (16.2 %), elemicin (14.9 %) and eucalyptol (14.8 %) were major compound in the previous study (Huang et al., 2012) while our study gave eucalyptol (42.42 %), caryophyllene oxide (9.77 %), α-calacorene (3.77 %) and linalool (3.35 %). The geographic location of I. lanceolatum could be the reason for the significant differences in chemical composition of essential oils.

In comparison with other species in the genus Illicium, many compounds in common could be found, such as eucalyptol, estragole, pinene and linalool in the essential oils from I. verum (Li et al., 2020), safrole, myristicin and eucalyptol in the essential oils from I. henryi (Liu et al., 2015). However, significant differences were also observed. Anethole, the most important compound in the I. verum essential oil was not detected in our study. Safrole (54.09 %) and myristicin (22.24 %), which were the major compounds in the I. henryi essential oil, accounted for only 2.01 % and 0.15 % in this study, respectively.

Of chemical compounds of I. lanceolatum EOs, attention should be paid to several compounds with similar structure, including asaricin, myristicin, elemicin and safrole. Myristicin, elemicin and safrole have been extensively studied. Myristicin could be found in nutmeg and parsley, and has shown several promising activities, such as anti-inflammatory, anticancer and insecticidal activities (Seneme et al., 2021). The toxicities of myristicin and elemicin have been reported in some studies, and safrole has been classified as genotoxic carcinogens based on extensive toxicological evidence (Götz et al., 2022). In this work, safrole was found in the fruit EO with relative percentage of 2.01 % and its existence could limit the application of the fruit EO in food industry. Asaricin accounted for 50.52 % in the root EO and has been previously reported in the essential oils of some plants, such as Beilschmiedia miersii (Carvajal et al., 2016) and several Piper species (Soares et al., 2022). Due to its insecticidal activity, this compound has been structurally modified to obtain a series of asaricin analogues (Guo et al., 2016). Many biological activities of this compound remained unknown. As asaricin has a similar structure with myristicin, it is likely to have some degree of toxicity. The root EO of I. lanceolatum could be a natural source of asaricin for further studies. Due to the existence of these toxic compounds, the application of I. lanceolatum essential oils in food industry may be restricted.

3.2 Antioxidant activity of I. lanceolatum EOs

In order to give a comprehensive evaluation on antioxidant activities of I. lanceolatum EOs, three methods with different mechanisms were employed. The antioxidant activity results were displayed in Table 2. In the DPPH assay, the fruit EO had the highest Trolox equivalent value (6.36 ± 0.10 mg TE/g of EO), while the highest Trolox equivalent value (10.24 ± 0.11 mg TE/g of EO) was observed for the root EO in the ABTS assay. In the DPPH and ABTS assays, I. lanceolatum EOs showed very weak radical scavenging capacity when they were compared with BHT. However, the root EO showed moderate antioxidant activity in the FRAP assay, with the Trolox equivalent value as 176.33 ± 4.52 mg TE/g of EO. Other three essential oils displayed very weak antioxidant activity in the FRAP assay. EO: essential oil; *: the unit for its antioxidant activities is mg TE/g of BHT.

Sample

DPPH assay mg TE/g of EO

ABTS assay mg TE/g of EO

FRAP assay mg TE/g of EO

Root EO

3.18 ± 0.15

10.24 ± 0.11

176.33 ± 4.52

Stem EO

1.31 ± 0.06

4.46 ± 0.20

2.48 ± 0.02

Leaf EO

1.06 ± 0.07

4.01 ± 0.16

4.16 ± 0.06

Fruit EO

6.36 ± 0.10

8.97 ± 0.05

14.26 ± 0.29

BHT *

631.56 ± 8.42

1169.81 ± 8.04

642.37 ± 13.35

Strong radical scavenging capacity of essential oil is closely connected with phenolic compounds, like thymol, carvacrol and eugenol, which can react with radicals by donating hydrogen atom (Zeb, 2020). Thymol and carvacrol existed in the root and fruit EOs, however, their relative percentages were only 0.10 % and 0.06 %, respectively. Very low relative percentages of phenolic compounds in the I. lanceolatum EOs could be the reason for their low radical scavenging capacities in the DPPH and ABTS assays.

As the root EO showed moderate antioxidant activity in the FRAP assay, its major compounds were further studied. There were 11 compounds which had the relative percentages of more than 1 % in the root EO. 9 purchased compounds could be in Table 3 and 2 compounds including τ-cadinol (1.35 %) and α-cadinol (1.41 %) were not available. These nine compounds were further evaluated by FRAP assay and results were given in Table 3. Seven compounds, such as borneol and eucalyptol, showed no activities. Camphene had very weak antioxidant activity in the FRAP assay. However, antioxidant activity with 311.76 ± 3.64 mg TE/g of TC was noticed for asaricin which had higher Trolox equivalent value than the root EO. Considering its high relative percentage (50.52 %), this molecule could be the main antioxidant compound in the root EO. Certainly, some other compounds which had lower relative percentages in the root EO could contribute together to the antioxidant activity. Synergistic and antagonistic effects between these compounds could exist. TE: Trolox equivalent; TC: tested compound.

Component

Relative percentage/%

FRAP assay (mg TE/g of TC)

asaricin

50.52 ± 0.33

311.76 ± 3.64

borneol

7.01 ± 0.02

No activity

camphor

5.71 ± 0.03

No activity

eucalyptol

5.44 ± 0.09

No activity

camphene

3.29 ± 0.05

3.21 ± 0.04

estragole

2.04 ± 0.01

No activity

terpinen-4-ol

1.59 ± 0.01

No activity

linalool

1.47 ± 0.01

No activity

α-terpineol

1.34 ± 0.01

No activity

BHT

/

642.37 ± 13.35

The antioxidant activity of asaricin in the FRAP assay was firstly reported in this research, however, antioxidant mechanism of asaricin was still unknown. Subsequent investigations could be performed to find out how asaricin react with ferric and if asaricin could exert real antioxidant protection in the application experiments.

3.3 Antimicrobial activity of I. lanceolatum EOs

Antimicrobial activities of essential oils from the roots, stems, leaves and fruits of I. lanceolatum were evaluated against 5 gram-positive bacteria, 3 gram-negative bacteria and 1 yeast. The MICs and MMCs of four essential oils were determined and presented in Tables 4-6. I. lanceolatum EOs showed some degree of antimicrobial activities against all tested microorganisms, with MIC values ranging from 3.13 to 25 mg/mL. According to the MIC criteria of essential oils (Van Vuuren and Holl, 2017), if the essential oil displayed an MIC of less than 1000 µg/ml, the antimicrobial activity could be considered to be noteworthy; from 101 to 500 μg/mL, the antimicrobial activity was strong; from 500 to 1000 µg/ml, the antimicrobial activity was moderate. In this work, I. lanceolatum EOs showed very weak antibacterial or antifungal activities, which was also confirmed by comparing their MICs with those of gentamycin sulfate or amphotericin B. MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; MMC: minimum microbiocidal concentration; EO: essential oil;

Samples

S. aureus

S. lentus

S. epidermidis

B. cereus

L. monocytogenes

MIC

MMC

MIC

MMC

MIC

MMC

MIC

MMC

MIC

MMC

Root EO

3.13

6.25

12.5

12.5

12.5

25

3.13

3.13

3.13

12.5

Stem EO

6.25

12.5

12.5

25

12.5

25

6.25

6.25

6.25

25

Leaf EO

6.25

12.5

25

>25

12.5

25

6.26

6.25

6.25

25

Fruit EO

3.13

3.13

12.5

12.5

12.5

25

6.25

6.25

6.25

12.5

Gentamycin sulfate

0.00005

0.0001

0.0004

0.0008

0.0004

0.0008

0.0001

0.0001

0.0004

0.0008

Samples

E. coli

P. aeruginosa

S. typhimurium

MIC

MMC

MIC

MMC

MIC

MMC

Root EO

6.25

12.5

25

> 25

6.25

12.5

Stem EO

12.5

25

25

> 25

12.5

25

Leaf EO

25

> 25

25

> 25

12.5

25

Fruit EO

12.5

25

25

25

12.5

12.5

Gentamycin sulfate

0.013

0.025

0.0002

0.0008

0.0008

0.0016

Samples

C. albicans

MIC

MMC

Root EO

12.5

25

Stem EO

12.5

25

Leaf EO

25

>25

Fruit EO

12.5

25

Amphotericin B

0.003

0.006

The root EO showed better antimicrobial activities than other three EOs, with MIC values as 3.13 mg/mL against three gram-positive bacteria including S. aureus, B. cereus and L. monocytogenes. MICs and MMCs of nine major compounds in the root EO against S. aureus, B. cereus and L. monocytogenes were further determined and displayed in Table 7. Two compounds (eucalyptol and estragole) showed no antimicrobial activities against three bacteria. MIC of asaricin against S. aureus was 12.5 mg/mL, which was higher than the MIC of the root EO. Of nine compounds, camphor showed the best antimicrobial activities, followed by borneol. MICs of camphor against three bacteria ranged from 0.78 to 3.13 mg/mL while MICs of borneol ranged from 1.56 to 3.13 mg/mL. These two compounds accounted for 7.01 % and 5.71 % in the root EO, while their highest relative percentage in other three EOs was only 0.26 %. Therefore, camphor and borneol could be the reason for better antibacterial activities of the root EO than other three EOs, and were two important antimicrobial compounds in the root EO. Besides the compounds listed in Table 7, many other compounds in the root EO, such as p-cymene (Marchese et al., 2017), α-pinene, β-pinene (Rivas da Silva et al., 2012) and thymol (Escobar et al., 2020) have been reported with antimicrobial activities. In general, essential oils with high content of thymol and other phenolic compounds have strong antimicrobial activities, as in the case of oregano essential oil. The relative percentage of thymol in the root EO was only 0.10 %, which means little contribution to antimicrobial activity. Only by looking at the antimicrobial activities of these compounds in the root EO, it was difficult to fully explain antimicrobial activity of this essential oil as synergistic and antagonistic effects existed in the essential oils. In previous studies, camphor has been reported to have synergistic antimicrobial effects with Lavandula latifolia essential oil (Karaca et al., 2021), and three essential oils from cinnamon, manuka, and winter savory have demonstrated synergistic antimicrobial activities (Fratini et al., 2019). Synergistic effects could be another factor for better antimicrobial activities of the root EO. MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; MMC: minimum microbiocidal concentration;

Compound

Relative percentages %

S. aureus

B. cereus

L. monocytogenes

MIC

MBC

MIC

MBC

MIC

MBC

asaricin

50.52 ± 0.33

12.5

25

> 12.5

> 12.5

> 12.5

> 12.5

borneol

7.01 ± 0.02

3.13

3.13

1.56

3.13

3.13

12.5

camphor

5.71 ± 0.03

0.78

1.56

1.56

1.56

3.13

3.13

eucalyptol

5.44 ± 0.09

>25

>25

>25

>25

>25

>25

camphene

3.29 ± 0.05

6.25

12.5

3.13

6.25

12.5

12.5

estragole

2.04 ± 0.01

>25

>25

25

>25

>25

>25

terpinen-4-ol

1.59 ± 0.01

12.5

25

12.5

12.5

12.5

25

linalool

1.47 ± 0.01

12.5

25

12.5

25

25

>25

α-terpineol

1.34 ± 0.01

12.5

12.5

6.25

6.25

12.5

12.5

gentamycin sulfate

/

0.00005

0.0001

0.0001

0.0001

0.0004

0.0008

3.4 Enzyme inhibitory activities of I. lanceolatum EOs

Tyrosinase, α-glucosidase, acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of I. lanceolatum EOs were determined to evaluate their whitening effect, anti-diabetes effect and improvement effect on neurodegenerative disease, and the results expressed as mg kojic acid equivalent (KAE)/g of EO, mg acarbose equivalent (AE)/g of EO and mg galanthamine equivalent (GE)/g of EO were presented in Table 8. In the antidiabetic drugs, one important category is α-glucosidase inhibitor, like acarbose and miglitol. Four essential oils showed no inhibitory activity on α-glucosidase, which indicated no potential of I. lanceolatum EOs as antidiabetic agents. However, I. lanceolatum EOs displayed inhibitory activities on other three enzymes. For tyrosinase and butyrylcholinesterase, the highest KAE value (30.34 ± 0.40 mg KAE/g of EO) and GE value (43.25 ± 1.50 mg GE/g of EO) were observed for the root EO, followed by the fruit EO. KAE: kojic acid equivalent; AE: acarbose equivalent; GE: galanthamine equivalent; EO: essential oil.

Sample

Tyrosinase mg KAE/g of EO

α-glucosidase mg AE/g of EO

Acetylcholinesterase mg GE/g of EO

Butyrylcholinesterase mg GE/g of EO

Root EO

30.34 ± 0.40

No activity

4.83 ± 0.16

43.25 ± 1.50

Stem EO

5.39 ± 0.36

No activity

8.39 ± 0.40

28.78 ± 0.84

Leaf EO

9.11 ± 0.17

No activity

17.79 ± 0.32

28.19 ± 1.03

Fruit EO

10.59 ± 0.53

No activity

4.35 ± 0.32

31.16 ± 0.84

The root EO showed better tyrosinase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activities than other three EOs, its nine major compounds were further evaluated and the results could be seen in Table 9. Tyrosinase play an important role in the biogenesis of melanin and tyrosinase inhibitors could find their use in skin-whitening. All nine tested compounds showed tyrosinase inhibitory activities. Asaricin showed the highest KAE value (33.42 ± 2.11 mg KAE/g of TC), followed by estragole (14.68 ± 0.17 KAE/g of TC). Considering its high relative percentage (50.52 %), asaricin could be main contributor to tyrosinase inhibitory activity of the root EO. Estragole has been reported to have skin-whitening effect and compounds synthesized from this molecule showed good tyrosinase inhibitory activity (Motoki et al., 2003). In the previous studies, polyphenols like flavonoids and phenolic acids as natural tyrosinase inhibitor (Zolghadri et al., 2019) have attracted a lot of attention. There were also numerous studies on the tyrosinase inhibitory activities of different essential oils, however, the reports on the tyrosinase inhibitory activities of individual compounds in the essential oils were limited. In this study, tyrosinase inhibitory activities of some compounds like asaricin were firstly reported. Synergistic strategy is often used to improve the inhibitory activities of tyrosinase inhibitors (Zolghadri et al., 2019), the synergistic effect could be one reason for the better tyrosinase inhibitor activity of the root EO. KAE: kojic acid equivalent; GE: galanthamine equivalent; TC: tested compound.

Compound

Relative percentages %

Tyrosinase mg KAE/g of TC

Butyrylcholinesterase mg GE/g of TC

asaricin

50.52 ± 0.33

33.42 ± 2.11

29.01 ± 2.60

borneol

7.01 ± 0.02

7.09 ± 0.24

No activity

camphor

5.71 ± 0.03

6.99 ± 0.55

20.68 ± 0.50

eucalyptol

5.44 ± 0.09

7.12 ± 0.37

7.47 ± 0.29

camphene

3.29 ± 0.05

4.69 ± 0.30

No activity

estragole

2.04 ± 0.01

14.68 ± 0.17

No activity

terpinen-4-ol

1.59 ± 0.01

8.77 ± 0.68

55.58 ± 3.41

linalool

1.47 ± 0.01

7.21 ± 0.85

No activity

α-terpineol

1.34 ± 0.01

9.19 ± 0.94

128.14 ± 2.85

For butyrylcholinesterase, only five tested compounds showed inhibitory activities. α-terpineol showed the best butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity (128.14 ± 2.85 mg GE/g of TC), followed by terpinen-4-ol (55.58 ± 3.41 mg GE/g of TC) and asaricin (29.01 ± 2.60 mg GE/g of TC). Eucalyptol (Costa et al., 2012a), camphor (Costa et al., 2012b) and terpinen-4-ol (Bonesi et al., 2010) have been reported to have butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activities in previous studies. Though α-terpineol and terpinen-4-ol showed higher GE values than the root EO (43.25 ± 1.50 mg GE/g of EO), their relative percentages were only 1.34 % and 1.59 %, respectively, counterbalancing their contribution to the butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of the essential oil. Asaricin, with relative percentage of 50.52 %, was still the most important contributor to the butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of the root EO. Certainly, the activity of the root EO could not be explained by these five compounds. There were other active compounds in the root EOs, like α-pinene and β-pinene (Orhan et al., 2008), which have been reported with activities. On the other hand, there were also the synergistic and antagonistic effects between these compounds.

For acetylcholinesterase, the leaf EO displayed better inhibitory activity (17.79 ± 0.32 mg GE/g of EO) than other three EOs. Chemical compounds of leaf EO were represented by eucalyptol (42.42 %) and caryophyllene oxide (9.77 %). The acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of eucalyptol (or 1,8-cineole) has been reported in many studies (Burcul et al., 2020) and that of caryophyllene oxide was also displayed in previous study (Savelev et al., 2004). In this study, eucalyptol was further evaluated for its acetylcholinesterase inhibition activity, with GE value as 32.59 ± 0.57 mg GE/g of TC. It could be concluded that eucalyptol was important active compound in the leaf EO. If considering both acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activities values, the leaf EO seemed to be a better one which could exert improvement on neurodegenerative diseases.

3.5 Cytotoxic activity of I. lanceolatum EOs

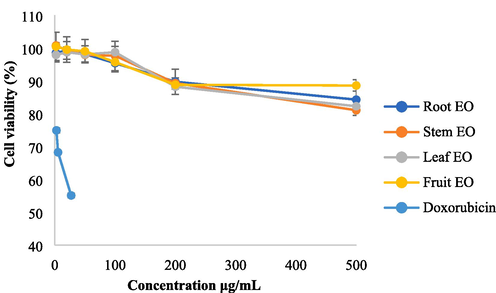

Cytotoxic effects of I. lanceolatum EOs on HK-2 (proximal tubular cell line of normal kidney), MCF-7 (human breast cancer cell line) and HepG2 (human liver carcinoma cell line) cells could be seen in Figs. 5-7, respectively. Doxorubicin was used as the positive control. At concentrations of 2, 20, 50 and 100 μg/mL, the cell viabilities of HK-2 were found to be more than 95 %, which means that I. lanceolatum EOs were nontoxic to HK-2 at these concentrations. When the concentrations reached to 200 μg/mL, the cell viabilities of HK-2 were nearly 90 %. At the concentration of 500 μg/mL, the cell viabilities of HK-2 treated with the fruit EO, were still 88.57 %. The fruit was highly toxic due to the existence of anisatin, however, only weak toxicity to normal kidney cells was observed for the fruit EO at the tested concentrations.

Cytotoxic effects on HK-2 treated with root, stem, leaf and fruit EOs at six concentrations.

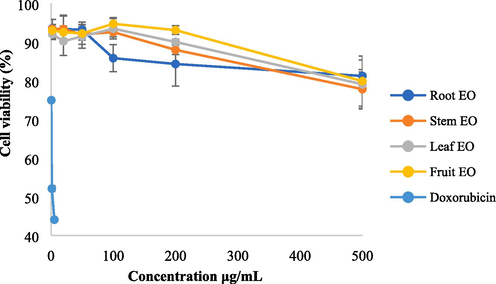

Cytotoxic effects on MCF-7 treated with root, stem, leaf and fruit EOs at six concentrations.

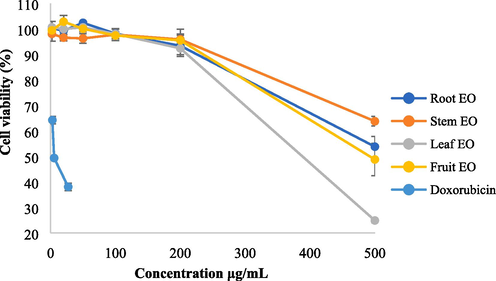

Cytotoxic effects on HepG2 treated with root, stem, leaf and fruit EOs at six concentrations.

As shown in Fig. 6, the cell viabilities of MCF-7 cells ranged from 77.84 % to 94.74 % at six tested concentrations. At the concentration of 500 μg/mL, I. lanceolatum EOs showed some degree of anticancer activities to MCF-7. Compared with doxorubicin which can inhibit almost 50 % of MCF-7 at the concentration of 1.36 μg/mL, anticancer activities to MCF-7 of I. lanceolatum EOs were very weak, indicating no potential as anticancer drugs.

For HepG2 cells treated with the I. lanceolatum EOs at concentrations of 200 μg/mL and below 200 μg/mL, the cell viabilities were more than 92 %. However, when the concentration reached up to 500 μg/mL, anticancer activities to HepG2 cells were observed for all four essential oils. The root and fruit EOs almost inhibited 50 % of HepG2 cells. The leaf EO inhibited even 75 % of HepG2 cells, indicating potential use in anticancer therapy.

A number of studies have been performed on the anticancer activities of the essential oils (Bhalla et al., 2013) and their constituents (Silva et al., 2021). Many compounds in the I. lanceolatum EOs have been reported with anticancer activities to HepG2 cells, such as eucalyptol (Rodenak-Kladniew et al., 2020), linalool (Rodenak-Kladniew et al., 2018), α-pinene (Xu et al., 2018) and β-elemene (Dai et al., 2013). The leaf EO was represented by high percentage of eucalyptol (42.42 %), which could be the reason for its better anticancer activity. Caryophyllene oxide, which accounted for 6.02 %, 9.77 % and 2.85 % in the stem, leaf and fruit EOs, respectively, were found to have no inhibition effects on HepG2 in previous study (Xiu et al., 2022). The synergistic effects between anticancer compounds may exist in the inhibition of HepG2 cells.

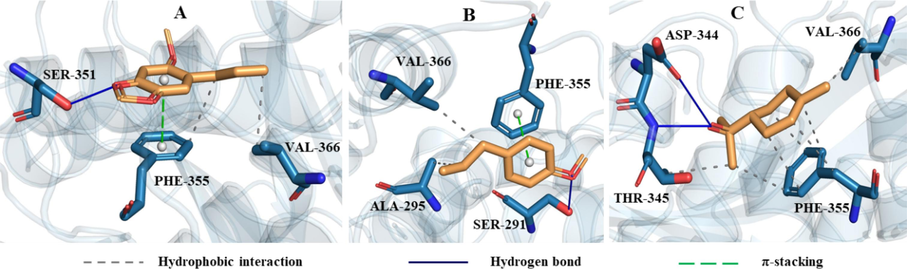

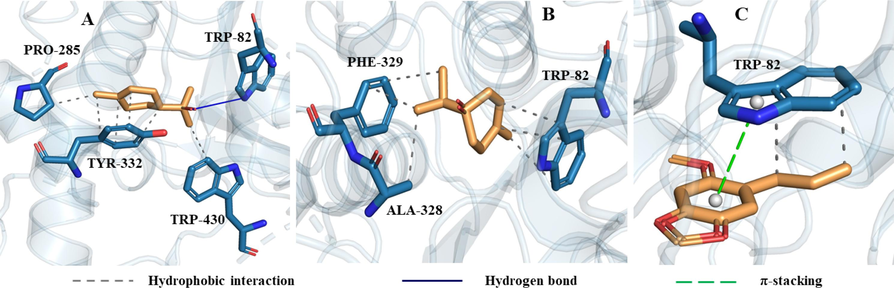

3.6 Molecular docking studies of selected compounds in the root EO

In the root EO, asaricin, estragole and α-terpineol showed better tyrosinase inhibitory activities while α-terpineol, terpinen-4-ol and asaricin showed better butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activities. These compounds were selected for molecular docking to investigate the interactions between ligands and enzymes. The binding affinities (kcal/mol) of these compounds against tyrosinase and butyrylcholinesterase were presented in Table 10. Asaricin showed the lowest binding affinities (-6.3 kcal/mol) with tyrosinase, indicating the strongest inhibitory activity of these three compounds, which was in accordance with the experimental results. The butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of α-terpineol (128.14 ± 2.85 mg GE/g TC) was much higher than those of terpinen-4-ol (55.58 ± 3.41 mg GE/g TC) and asaricin (29.01 ± 2.60 mg GE/g TC), however, no significant differences could be observed among binding affinities of these three compounds (p < 0.05). It is difficult to accurately predict the activity of one molecule only by using binding affinity. Generally, different molecular docking software should be employed together for screening or comparison of active compounds.

No.

Compound

PubChem ID

Binding Affinities (kcal/mol)

Tyrosinase

Butyrylcholinesterase

1

asaricin

95289

−6.3 ± 0.0

−6.0 ± 0.1

2

estragole

8815

−5.7 ± 0.1

/

3

terpinen-4-ol

11230

/

−5.9 ± 0.1

4

α-terpineol

17100

−6.0 ± 0.0

−6.1 ± 0.0

The interactions of asaricin, estragole and α-terpineol with amino acid residues in the binding pocket of tyrosinase could be seen in Fig. 8. The main interactions of asaricin and estragole with tyrosinase were hydrophobic interaction, hydrogen bond and π-stacking. α-terpineol formed two hydrogen bonds with ASP-344 and THR-345, and had hydrophobic interactions with three residues including THR-345, PHE-355 and VAL-366. The interactions of α-terpineol, terpinen-4-ol and asaricin with amino acid residues of butyrylcholinesterase were shown in Fig. 9. α-terpineol formed one hydrogen bond with TRP-82 and had hydrophobic interactions with three residues including PRO-285, TYR-332 and TRP-430. Terpinen-4-ol mainly interacted with butyrylcholinesterase by hydrophobic interaction. Asaricin had hydrophobic and π-stacking interactions with TRP-82. From the interactions of these three compounds, it can be seen that TRP-82 was one of important amino acid residues in the active site of butyrylcholinesterase.

The interactions of tyrosinase with asaricin (A), estragole (B) and α-terpineol (C).

The interactions of butyrylcholinesterase with α-terpineol (A), terpinen-4-ol (B) and asaricin (C).

4 Conclusion

In the present study, chemical compounds and biological activities of essential oils from the roots, stems, leaves and fruits of I. lanceolatum were comprehensively investigated. 110 compounds were identified in these essential oils, representing 91.85 % to 94.84 % of the total compositions. Asaricin was found to be the most abundant compound in the root EO while eucalyptol had the highest relative percentages in other three EOs. I. lanceolatum EOs showed weak radical scavenging capacities, but the root EO displayed moderate reducing ability which was caused by asaricin. I. lanceolatum EOs showed antimicrobial activities against all tested microorganisms. Especially, the root EO showed better antimicrobial activities than other three EOs, with MIC values as 3.13 mg/mL against three bacteria including S. aureus, B. cereus and L. monocytogenes. Camphor and borneol were found to be important antimicrobial compounds in the root EO. For enzyme inhibitory activities, no inhibitory activity on α-glucosidase was observed. The root EO showed better tyrosinase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activities while the leaf EO displayed better acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity. Molecular docking revealed that the main interactions between active compounds (asaricin, estragole, terpinen-4-ol and α-terpineol) and enzymes (tyrosinase and butyrylcholinesterase) were hydrophobic interaction, hydrogen bond and π-stacking. At six tested concentrations, only weak cytotoxicity was observed to HK-2 cells of normal kidney. I. lanceolatum EOs showed very weak anticancer activities to MCF-2 cells but significant anticancer activities to HepG2 cells at the concentration of 500 μg/mL. In this study, antioxidant, antimicrobial, enzyme inhibitory and cytotoxic activities of I. lanceolatum EOs and some compounds were firstly reported. I. lanceolatum EOs was found to be promising with possible applications in pharmaceutical and cosmetic industries.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful for the financial support provided by the Research Center for Microreaction Engineering of Guizhou Colleges and Universities (Grant No. Qian Jiao He KY Zi [2015]339), the High-level Talent Research Funding Project of Guizhou Institute of Technology (XJGC20161206) and the Science and Technology Project of Guizhou Company of China Tobacco Corporation (2022XM14).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tianming Zhao: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Guang Fan: Investigation, Formal analysis. You Tai: Investigation. Xinhe Shu: Investigation. Fu Tian: Investigation, Formal analysis. Shuliang Zou: Software, Investigation. Qin Wu: Software, Investigation, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (4th Edition). Carol Stream: Allured Publishing Corporation; 2007.

- Aroma profile and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of essential oil of Mentha spicata leaves. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants. 2021;24(5):1042.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer activity of essential oils: a review. J. Sci. Food Agric.. 2013;93(15):3643-3653.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of Pinus species essential oils and their constituents. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem.. 2010;25(5):622-628.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Terpenes, phenylpropanoids, sulfur and other essential oil constituents as inhibitors of cholinesterases. Curr. Med. Chem.. 2020;27(26):4297-4343.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal, M.A., Vergara, A.P., Santander, R., Osorio, M.E., 2016. Chemical composition and anti-phytopathogenic activity of the essential oil of Beilschmiedia miersii. Nat Prod Commun. 11(9), 1367-1372. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30807044.

- Supercritical fluid extraction and hydrodistillation for the recovery of bioactive compounds from Lavandula viridis L’Hér. Food Chem.. 2012;135(1):112-121.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical profiling and biological screening of Thymus lotocephalus extracts obtained by supercritical fluid extraction and hydrodistillation. Ind. Crop. Prod.. 2012;36(1):246-256.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of beta-elemene on human hepatoma HepG2 cells. Cancer Cell Int.. 2013;13(1):27.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thymol bioactivity: a review focusing on practical applications. Arab. J. Chem.. 2020;13(12):9243-9269.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A short overview on the medicinal chemistry of (-)-shikimic acid. Mini Rev. Med. Chem.. 2012;12(14):1443-1454.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting secondary metabolite production in plants: volatile components and essential oils. Flavour Fragr. J.. 2008;23(4):213-226.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity of three essential oils (cinnamon, manuka, and winter savory), and their synergic interaction, against Listeria monocytogenes. Flavour Fragr. J.. 2019;34(5):339-348.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hong-Hui-Xiang alleviates pain hypersensitivity in a mouse model of monoarthritis. Pain Res. Manag.. 2020;2020:5626948.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Myristicin and elemicin: potentially toxic alkenylbenzenes in food. Foods. 2022;11:1988.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New phenylpropanoid and other compounds from Illicium lanceolatum with inhibitory activities against LPS-induced NO production in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Fitoterapia. 2014;95:51-57.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iodine-catalyzed oxidative cyclisation for the synthesis of asaricin analogues containing 1,3,4-oxadiazole as insecticidal agents. RSC Adv.. 2016;6:93505-93510.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition, antibacterial, enzyme-inhibitory, and anti-inflammatory activities of essential oil from Hedychium puerense Rhizome. Agronomy-Basel. 2021;11(12):2506.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Distinguishing Chinese star anise from Japanese star anise using thermal desorption-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2009;57(13):5783-5789.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of the volatile components of Illicium verum and I. lanceolatum from East China. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Plants. 2012;15(3):467-475.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic antibacterial combination of Lavandula latifolia Medik. essential oil with camphor. Z Naturforsch C. J. Biosci.. 2021;76(3–4):169-173.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multi-target-directed ligands for treating Alzheimer's disease: Butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors displaying antioxidant and neuroprotective activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2018;156:598-617.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tetranorsesquiterpenoids and santalane-type sesquiterpenoids from Illicium lanceolatum and their antimicrobial activity against the oral pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Nat. Prod.. 2015;78(6):1466-1469.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Germacrane-type sesquiterpenoids from Illicium lanceolatum. Tetrahedron. 2022;109:132673

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents from the fruits of Illicium lanceolatum. Chin. Pharm. J.. 2014;49(08):636-639.

- [Google Scholar]

- Illicium verum essential oil, a potential natural fumigant in preservation of lotus seeds from fungal contamination. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2020;141:111347

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory properties of essential oil from the roots of Illicium lanceolatum. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2012;26(18):1712-1714.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Two new monoterpenes from the fruits of Illicium lanceolatum. Molecules. 2013;18(10):11866-11872.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Investigation on seco-prezizaane sesquiterpenes from fruits of Illicium lanceolatum and their neuroprotection activity. China J. Chinese Mater. Med.. 2019;44(19):4207-4211.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Highly oxidized sesquiterpenes from the fruits of Illicium lanceolatum A. C. Smith. Phytochemistry. 2020;172:112281

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Larvicidal activity of essential oil derived from Illicium henryi Diels (Illiciaceae) leaf. Trop. J. Pharm. Res.. 2015;14(1):111-116.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents of plants from the genus Illicium. Chem. Biodivers.. 2009;6(7):963-989.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Non-destructive discrimination of Illicium verum from poisonous adulterant using Vis/NIR hyperspectral imaging combined with chemometrics. Infrared Phys. Technol.. 2020;111:103509

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Update on monoterpenes as antimicrobial agents: a particular focus on p-cymene. Materials (Basel). 2017;10(8):0947.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of the neurotoxin anisatin in star anise by LC-MS/MS. Food Addit. Contamin.: Part A. 2013;30(9):1598-1605.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Latent and active abPPO4 mushroom tyrosinase cocrystallized with hexatungstotellurate(VI) in a single crystal. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr.. 2014;70(9):2301-2315.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Skin whitening effects of estragole derivatives. J. Oleo Sci.. 2003;52(9):495-498.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Illilanceolide A, a unique seco-prezizaane sesquiterpenoid with 5/5/6 tricyclic scaffold from the fruits of Illicium lanceolatum A. C. Smith. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2021;70:153022

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- seco-Prezizanne sesquiterpenes and prenylated C6–C3 compounds from the fruits of Illicium lanceolatum A. C. Smith. Chem. Biodivers.. 2022;19(1):202100868.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Activity of essential oils and individual components against acetyl- and butyrylcholinesterase. Z. Naturforsch., C: J. Biosci.. 2008;63(7–8):547-553.