Translate this page into:

Antioxidant, α-amylase and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory potential of Mazus pumilus (Japanese Mazus) extract: An in-vitro and in-silico study

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia. ahmadsaheem@gmail.com (Saheem Ahmad), s.ansari@uoh.edu.sa (Saheem Ahmad),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University. Production and hosting by Elsevier.

Abstract

Plant-derived secondary metabolites possess diverse biological activities that are beneficial to humans. Modern medications used for diabetes and Alzheimer’s often cause side effects, prompting reliance on traditional alternatives. Therefore, we aimed to uncover the potential of Mazus pumilus in countering diabetes and Alzheimer’s by in-vitro inhibition of α-amylase and AChE. Additionally, antioxidant activity and phytochemical analyses were performed. Mazus pumilusThe plant was extracted sequentially using n-hexane, ethyl acetate, dichloromethane, methanol, and water. The methanolic fraction, notably, manifested marked antioxidant efficacy against DPPH and ABTS radicals. Subsequently, this extract evinces noteworthy inhibitory attributes against α-amylase and AChE, respectively, in a competitive manner. Moreover, the bioactive phytoconstituents present in the methanolicextracts were determined through GC–MS analysis, and subsequent computational molecular docking studies revealed that these compounds strongly bound to the active site of both α-amylase and AChE. The calculated least binding energies, for α-amylase and AChE, underscore the viability of the molecular interactions. In conclusion, the antioxidant, antidiabetic, and anti-Alzheimer attributes of Mazus pumilus extract likely emanate from the synergistic interplay of its bioactive phytoconstituents. A comprehensive in-vitro and in-vivo study is essential to fully explore the anti-diabetic and anti-Alzheimer potential of secondary metabolites of Mazus pumilus.

Keywords

Oxidative stress

Diabetes

Alzheimer’s

Neurological disorder

Acetylcholinesterase

Secondary metabolites

1 Introduction

Nature has created plant kingdom which is having super power for curing and treating variety of human and animal diseases. These plants produce variety of secondary metabolites that has Fstrong therapeutic properties, offering natural sources for medicines, antioxidants, and dietary supplements, and promoting overall health and well-being (Leicach and Chludil, 2014). Various in-vitro and in-vivo studies suggested that plant extract, fruits, and their secondary metabolites can prevent the diabetes and neurological disorders (Ahmad et al., 2021; Alvi et al., 2019; Caputo et al., 2023; Hashim et al., 2019; P et al., 2011). It is widely acknowledged that plants can provide remedies for diseases and that it is necessary to correctly identify the plant and their secondary metabolites to use it effectively.

Numerous metabolic and neurological illnesses, such as diabetes mellitus (DM) and Alzheimer's disease (AD), are significantly influenced by oxidative stress. (Bhatti et al., 2022). DM, characterized by impaired carbohydrate metabolism and insufficient secretion or action of insulin, resulting in upregulated plasma glucose levels (Waiz et al., 2023). Persistent hyperglycaemia is responsible for the overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and damages macromolecules such as lipids, proteins, and DNA (Waiz et al., 2023). Diabetes is increasing worldwide as more than half a billion people are affected, including men, women, and children. This number is projected to double to 1.3 billion in the next 30 years (Khan et al., 2023; Waiz et al., 2023).

AD is the prevailing manifestation of dementia, characterized by prominent symptoms encompassing memory impairment, aphasia, cognitive decline, visuospatial deficits, and compromised executive function (Alvi et al., 2019). Several recent studies have established that aggregation of β-amyloid (Aβ) peptides and tau-neurofibrillary tangles initiates a cascade of events leading to Alzheimer's disease (Chen et al., 2017; Gulisano et al., 2018; Hampel et al., 2021).Some evidence also suggests that acetylcholinesterase (AChE) may play a key role in developing senile plaques by accelerating Aβ deposition (García-Ayllón et al., 2011; Inestrosa et al., 1996). Elevated activity of this enzyme causes depletion of ACh, which impairs synaptic transmission and disrupts neuronal signalling, resulting in AD (Iqbal et al., 2021). AD's exact cause is unclear, but its pathogenesis is linked to disrupted cholinergic signalling. Inhibiting AChE is a recognized treatment for AD.

On the other hand, individuals with diabetes have a 65 % higher chance of developing Alzheimer's disease than people without the condition. The relationship of hyperglycaemia and insulin anomalies with AD seems so robust that it is frequently considered a neuroendocrine disorder called “diabetes type 3” (H. Ferreira-Vieira et al., 2016). Several mutual pathophysiologies are shared by individuals suffering from chronic DM and AD, such as oxidative stress, inflammation (Haan, 2006), neuronal degeneration, β-amyloid accumulation (Ristow, 2004), phosphorylation of tau protein, and glycogen kinase-3 synthesis (Kroner, 2009).

Antidiabetic medications targeting insulin resistance in brain can potentially prevent AD and dementia. Despite their efficacy, they do not reverse complications and often entail notable side effects (Dey et al., 2002; Wium-Andersen et al., 2019). However, plants and their secondary metabolites possess therapeutic potential against several complications, including diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease (Franco et al., 2002). As an alternative, natural sources are under investigation for dual-action compounds against DM and AD to minimize complications. Approaches addressing oxidative stress, impeding glucose absorption, and inhibiting α-amylase and AChE to modulate ACh synthesis hold promise for the effective management of both conditions..

Mazus pumilus, commonly called Japanese Mazus, is a flowering plant belonging to the Mazaceae family. It has been found in Bhutan, China, India, Pakistan, and Indonesia. This annual plant thrives in wet grasslands, streambanks, and disturbed areas such as cultivated fields and sidewalks, reaching a height of 30 cm. Its flowers, marked with yellow spots in the throat, are a mix of purple and white, blooming throughout the growing season. The herbs hold significant therapeutic value; traditionally, leaves have been used for epileptic seizures (Sharma et al., 2013) and also possess antioxidant (Shahid et al., 2013), anti-inflammatory, anti-nociceptive (Ishtiaq et al., 2018b), antibacterial, antifungal (Safdar et al., 2015), antipyretic (Ishtiaq et al., 2018a), anticancer (Priya and Rao, 2016), and hepatoprotective activities (Ishtiaq et al., 2018b). The herb was also used in constipation and stimulation of menstrual flow. Leaf juice is also used in typhoid fever (Ishtiaq et al., 2018a). Previously, the presence of phytochemicals, such as saponins, tannins, terpenoids, glycosides, sterols, flavonoids, and alkaloids in the methanolic extract of Mazus pumilus has been reported (Ishtiaq et al., 2018b). Within this context, we for the first time, explored the potency of Mazus pumilus extract as a dual inhibitor of α-amylase and AChE. Furthermore, to gain mechanistic insights into their inhibitory actions, we conducted molecular docking investigations on secondary metabolites, identified in methanolic (MeOH) extract of Mazus pumilus using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS).

2 Material and methods

2.1 Chemicals

The chemicals used in this study such as n-hexane, ethyl acetate (EtOAc), dichloromethane (DCM), methanol (MeOH), 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ), ascorbic acid, ferric chloride (FeCl3), ferrous sulfate (FeSO4), pancreatic α-amylase, 5,5′-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), acetylcholine iodide (AChI), 9-amino-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroacridine hydrochloride (tacrine hydrochloride), ABTS, Potassium persulfate (K2S2O8), 3,5-Dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) and acetylcholinesterase (AChE) were procured from reputable sources like Hi-Media Sisco Research Lab and Sigma Aldrich. Notably, every chemical was of an analytical grade.

2.2 Preparation of Mazus pumilus extract

Whole plant of Mazus pumilus was collected from local area around the Integral University, Lucknow, India, in the winter season. The plant was botanically identified and the specimen of the plant (Voucher No. IU/PHAR/HRB/23/22) has been submitted to the herbarium. After that the plant was thoroughly cleaned by washing to remove any filth or dust particles and shed dried for seven days before being ground into a powder. Using Soxhlet apparatus, the dried powder (25 g) was extracted using n-hexane, DCM, EtOAc, MeOH, and water. After filtering, the crude extract was scraped out and kept at The − 20 °C for further use (Hashim et al., 2013). The formula below was used to calculate the % yield of the various extracts:

2.3 Determination of phytochemicals

Mazus pumilus extracts were qualitatively analyzed for phytoconstituents, including phenols, glycosides, and steroids.. Briefly, qualitative analysis of phenols was performed using the ferric chloride (FeCl3) test, in which a few drops of 5 % FeCl3 were added to the extract solution. A dark green or bluish-black color appeared. The presence of glycosides was revealed by the Keller-Killani test. Briefly, in the filtered extract solution, 1.5 mL of glacial acetic acid, 1 drop of 5 % FeCl3, and concentrated H2SO4 were added. A blue solution appeared in the acetic acid layer. Furthermore, the presence of phytochemicals in plant extract was analysed according to the previously described methods (Harborne, 1998; Shaikh and Patil, 2020).

2.4 Free radical scavenging activity

2.4.1 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay

The DPPH assay described by Brand-Williams et al. (Brand-Williams et al., 1995) was used to evaluate the free radical neutralizing ability of Mazus pumilus extract which represents its antioxidant potential. The reference standard, ascorbic acid, serving as a point of comparison. The absorbance was recorded at 517 nm using Eppendorf Bio-Spectrometer kinetic. The equation described below was used to compute the percentage of DPPH inhibition.

2.4.2 ABTS scavenging assay

The 2.45 millimolar (mM) of potassium persulfate was mixed to obtain a 7 mM concentration of ABTS stock solution. The solution was diluted in order to obtain an absorbance of 0.70 at 734 nm (nm) before the experiment. The absorbance was recorded on an Eppendorf Bio-Spectrometer kinetic. The varied concentrations of the extracts [100 µl (μL)] was mix with the 900 μL of working solution of ABTS, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 30 min (Re et al., 1999). Ascorbic acid was used as the reference standard. The percentage inhibition calculation followed the same formula as the DPPH calculation.

2.4.3 Ferric reducing antioxidant power

The standard protocol (Benzie and Strain, 1996) with slight modifications (Alvi et al., 2016) was used to determine the total antioxidant potential. Briefly, 300 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH-3.6), 10 mM of 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ) and 20 mM of ferric chloride (FeCl3) was mixed in a ratio of 10:1:1 to prepare FRAP reagent. 3 mL of FRAP reagent mixed with 100 µL of varied concentration of extract and incubated in dark for 30 min at 37 °C. The Eppendorf Bio-Spectrometer kinetic was used to take optical density (OD) at 593 nm. The standard curve of FeSO4 has been used for reckoning of results, indicated as μmol Fe (II)/g dry weight of Mazus pumilus plant powder.

2.5 Estimation of α-Amylase inhibitory potential of Mazus pumilus

The sequentially extracted Mazus pumilus extract was screened for inhibitory potential against α-amylase using a standard protocol (Akhter et al., 2013). Briefly, PBS buffer (20 mM; pH 6.7) containing 6.7 mM of NaCl was used to prepare the enzyme (5 units/mL). After that varied concentration of standard acarbose or extract were added except in the blank. This mixture was incubated for 20 min at 37 °C. Then the starch solution (0.5 % w/v) was added and further incubated at 37 °C for an additional 15 min. At the end of incubation, DNS reagent was added to the reaction mixture and heated at 100 °C in a water bath for 10 min. The pH of the buffer was measured using Labman pH meter (Model-NU-PH10) Absorbance was taken at 540 nm using Eppendorf Bio-Spectrometer kinetic. The inhibition rate was calculated by using the following equation:

where % reaction = (mean product in sample/mean product in control) × 100.

2.6 Estimation of Anti-Acetylcholinesterase potential

The acetylcholinesterase test was performed according to the method described by Ellman et al. (1961) (Ellman et al., 1961). Briefly, 10 mM DTNB (33 μL), 1 mM AChI (100 μL), 50 mM Tris HCl buffer (767 μL; pH 8.0), and different doses of extract (100 μL) were mixed in a 2 mL cuvette, which is served as blank. The AChE solution (0.28 U/mL, 300 μL) was added in the test reaction by replacing equal volume of buffer. Tacrine was served as the standard. The pH of the buffer was adjusted using Labman pH meter (Model-NU-PH10). The Enzyme activity was monitored on Eppendorf Bio-Spectrometer kinetic for 20 min by taking the absorbance at 405 nm at 1-minute intervals. The following equation was used to compute the percentage of enzyme activity inhibition.

2.7 Elucidation of α-Amylase inhibition mode by the MeOH extract of Mazus pumilus

In order to comprehend the mechanism by which the Mazus pumilus (MeOH extract) inhibits α-amylase activity, the inverse values of velocity and substrate concentration was plotted (Lineweaver-Burk plot) on a graph. The protocol of the reaction was the same as α-amylase inhibition as mentioned in section 2.5. Herein varied concentration of substrate ranging from 0.625 to 5 mg/mL was used to evaluate the effect on Vmax and Km.

2.8 Assessment the mode of inhibition of AChE activity by the MeOH extract of Mazus pumilus

The Mazus pumilus extract was used in the kinetic investigation at three distinct concentrations (0.0, 50, and 100 g/mL of reaction) and at three different substrate concentrations (0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 mM). AChI hydrolysis by AChE in the presence or absence of an inhibitor, was monitored for 20 min at 405 nm. At 1-minute intervals, the absorbance was measured, and the inhibition mode was elucidated with the help of Michaelis-Menten kinetics (Iqbal et al., 2021).

2.9 Gas Chromatography-Mass spectrometry analysis of the MeOH extract

The phytoconstituents present within the MeOH extract, demonstrating the most pronounced inhibitory efficacy against α-amylase and acetylcholinesterase (AChE), were discerned through Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis. Using a Shimadzu QP 2010 Ultra GC–MS instrument, the material was loaded into a Restek column (30 m 0.25 mm) with a film thickness of 0.25 m. The carrier gas's helium flow rate was fixed at 1 mL per minute. To identify the compounds, the mass spectra peaks were matched to the reference National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) libraries.

2.10 ADME and drug-likeness studies of selected ligands

The pharmacokinetic profiling and drug-likeness properties of selected ligands were depicted using the web-based tool Swiss ADME, as defined in earlier studies (Daina et al., 2017). Briefly, the SMILES of compound of the interest was copied from the PubChem database and pasted (contains one molecule per line) with an optional molecule name separated by one space in the given box. Then was clicked on the run to calculate the results.

2.11 Predicted toxicity of the selected compounds

The toxicity assessment was executed using the ProTox-II platform. This online web-based server specializes in predicting the toxicological profiles of small molecules. The analysis was conducted on November 25, 2022. The platform furnishes comprehensive information concerning compound toxicity, encompassing parameters such as LD50, Carcinogenicity, Immunotoxicity, Mutagenicity, Cytotoxicity, and hepatotoxicity (Banerjee et al., 2018).

2.12 Ligand’s structure retrieval and preparation

The 3D structures of the selected compounds were retrieved from the PubChem database. Each substance is listed with an inimitable credentials numeral, namely, CID. The retrieved 3D structure.sdf file was visualized via BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer and saved into the.pdb file format. The retrieved.sdf files were incorporated in the Maestro workspace, and all ligands were minimized with the help of the LigPrep module by applying the OPLS_2005 force field for molecular docking studies. The Epik module was utilized for the possible ionization and tautomerization of selected structures at pH 7.0 +/− 2.0 (David et al., 2018; Sheikh et al., 2023).

2.13 Retrieval and preparation of target protein for docking

The 3D structures of both enzymes (target proteins) were obtained from the PDB database on June 2023 by entering their protein IDs (α-amylase:3BAJ, AChE:1ACJ) (Berman et al., 2000). The retrieved target protein was visualized and examined using the BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 2022. We prepared our docking target protein using the protein preparation wizard's Schrödinger's Maestro module. The assignment of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds), bond orders, addition of hydrogen atoms, optimization and minimization of proteins, removal of water beyond five angstroms from the het group, and conversion of selenomethionines to methionines are important steps in the preparation. Further, pH 7.0 +/− 2.0 were used to fill the loop and then pre-processed with the protein. The OPLS_2005 force field was applied to refine the targeted protein, converging complete heavy atoms to a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.30, with the help of the protein preparation module Maestro v12.8. The SiteMap tool identifies highly potential binding pockets of ligands on proteins.

2.14 Receptor grid generation

The Sitemap tool (Goodford's GRID algorithm) in the Maestro v12.8 module was used to determine the available regions in the target binding site for ligands (Goodford, 1984; Mutlu, 2014). The highest site score and volume to create a grid on the binding site were carefully chosen—a van der Waal's radius scaling of 1.0, with 0.25 partial charges cut-off by default. The receptor grid was generated using the 'pick to identify the ligand molecule’ in the Glide module (Ansari et al., 2022; Patschull et al., 2012).

2.15 Molecular docking studies

To execute the flexible ligand molecular docking studies, we used Maestro’s Glide module to access GC–MS-identified compounds' binding pattern against the target proteins α-amylase and AChE. The previously prepared receptor grid file and prepared ligand file were input into the Glide module of protein–ligand docking, and by leaving all the fields in default mode, the job was submitted. Post molecular docking, the ligand binding position examination and data construction were performed with the help of Maestro 12.8 and Discovery Studio Visualizer 2022 (Accelrys Software Inc. San Diego) software.

2.16 Statistical analysis

For entire biochemical measurements, the experiments were performed in triplicate, and statistics were provided as mean ± SD.

3 Result and discussion

3.1 Phytochemical screening of Mazus pumilus plant extract

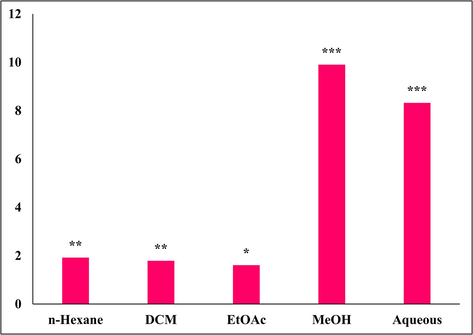

Natural products and their derivatives have long been recognized as valuable reservoirs of therapeutic agents and structural diversity. Fundamentally, the process of discovering new drugs entails identifying novel chemical entities that possess the necessary attributes of druggability and medicinal chemistry. Prior to the emergence of high-throughput screening and the post-genomic era, over 80 % of pharmaceutical compounds consisted either of natural products or were influenced by molecules derived from nature, which also encompassed semi-synthetic analogs (Katiyar et al., 2012). Therefore, in our study, the whole plant of Mazus pumilus was extracted using n-Hexane, EtOAc, DCM,MeOH, and water. The percent yield of extraction is presented in Fig. 1. Initially, qualitative phytochemical analysis was performed to revealed the presence or absence of different class of phytochemicals in the particular extract. Our results demonstrated that the MeOH extract has a rich amount of phenols and flavonoids compared to other extract (Table. 1). A previous study also reported the same in methanolic extracts (Ishtiaq et al., 2018b).

The percentage yield of plant extract. Significance was determined as *p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001 versus zero percent.

n-Hexane

DCM

EtOAc

MeOH

Aqueous

Cardiac glycosides

–

++

+++

+

–

Steroids

–

–

–

+

–

Phenols

++

+

–

+++

++

Flavonoids

+++

+

–

++

+

Tannins

–

–

–

+

+

Saponins

–

–

–

+++

+

Terpenoids

–

++

+

–

–

Quinones

–

–

–

–

–

Coumarins

+++

+++

–

++

+

Phlobatannins

–

–

–

–

–

Anthocynins

–

–

–

+

–

3.2 Determination of antioxidant potential via inhibition of DPPH and ABTS free radical and FRAP assay

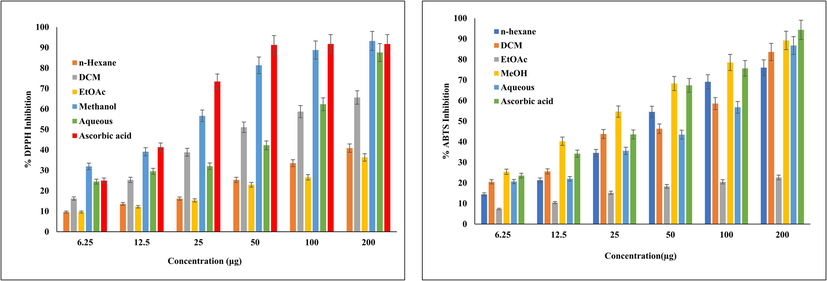

Oxidative stress is responsible for several chronic complications, such as DM (Giacco and Brownlee, 2010). However, Nevertheless, oxidative stress and DM are determinant factors that play significant roles in the development of various diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetic neuropathy, and AD. (Nabi et al., 2021, 2019). In fact, hyperglycaemia also induces oxidative stress and inflammation that causes damage to the tissues (Waiz et al., 2022). Therefore, we investigated the antioxidant potential of sequentially extracted Mazus pumilus extract by inhibiting DPPH, ABTS free radicals, and ferric-reducing ability. The percent inhibition of these free radicals by different Mazus pumilus extracts is shown in Fig. 2. The MeOH extract exhibited significant inhibition of DPPH and ABTS with IC50 values of 19.45 ± 1.32 and 20.54 ± 1.81 µg/mL, respectively (Table 2). Although, the reference standard ascorbic acid IC50 value against DPPH and ABTS were 16.20 ± 1.72 and 22.08 ± 1.02 µg/mL, respectively. Our findings suggestsuggested that the MeOH extract has an almost effect similarsimilar effect compared to that of the standard in inhibiting these free radicals (Table 2). (Table 2). Free radicals possess unpaired electrons through which they interact with and modify lipids, proteins, and DNA, inducing oxidative stress that contributes to several human diseases. Therefore, the utilization of external antioxidants can aid in managing oxidative stress. Plants containing bioactive compounds such as phenols and flavonoids can assist in mitigating oxidative stress. These compounds serve as vital antioxidant components because they can neutralize free radicals by donating hydrogen atoms to them. Moreover, they exhibit favorable structural attributes for scavenging free radicals (Amarowicz et al., 2004). Additionally, the FRAP value was also evaluated and found to be significantly higher in MeOH extract, (378.50 ± 6.98) µmol Fe(II)/g. The remarkable antioxidant potential of the MeOH extract might be attributed to the palpable presence of phenols and flavonoids, which are believed to be the majority of the antioxidant properties of plants (Dai and Mumper, 2010; Hashim et al., 2013). The data is represented as ± SEM. *Microgram/milliliter.

Percent inhibition of DPPH and ABTS radical via different extract of Mazus pumilus. The data are expressed as mean ± SD obtained after three parallel experiment.

Activity

Extract/Standard

IC50 (μg/ml*)

DPPH

n- hexane

NA

DCM

47.50 ± 2.24

EtOAc

NA

MeOH

19.45 ± 1.32

Aqueous

69.21 ± 1.49

Ascorbic acid

16.20 ± 1.72

ABTS

n- hexane

43.96 ± 2.61

DCM

65.34 ± 2.23

EtOAc

NA

MeOH

20.54 ± 1.81

Aqueous

74.66 ± 3.52

Ascorbic acid

22.08 ± 1.02

α-amylase inhibition

n- hexane

NS

DCM

201.83 ± 3.73

EtOAc

NS

MeOH

72.74 ± 2.83

Aqueous

NS

Acarbose

42.79 ± 1.43

Acetylcholinesterase inhibition

n- hexane

NA

DCM

172.75 ± 2.32

EtOAc

NA

MeOH

156.29 ± 4.53

Aqueous

318.89 ± 5.65

Tacrine

3.27 ± 0.34

3.3 Determination of α-amylase and AChE inhibition and kinetics studies

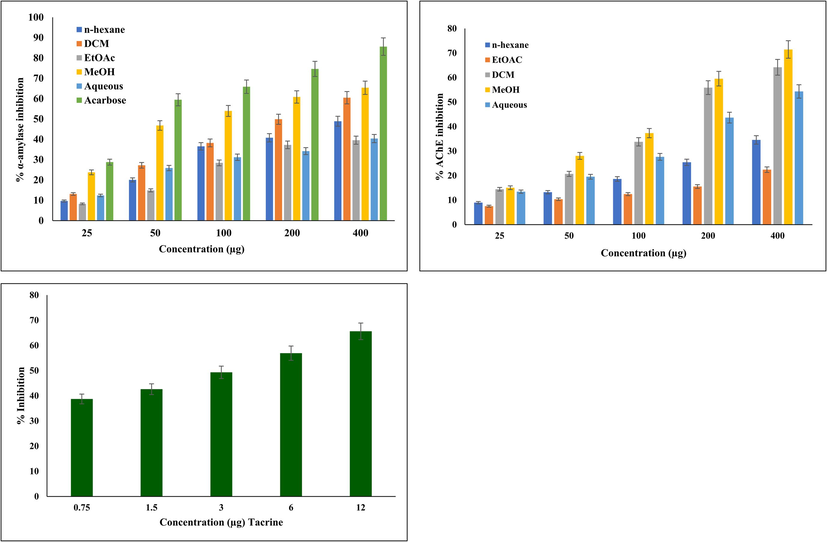

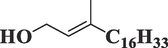

To control hyperglycaemia, a number of therapeutic methods have been developed, in which key enzyme inhibition is widely accepted (Tundis et al., 2010). Altered carbohydrate-metabolizing enzymes (α-amylase and α-glucosidase) are responsible for elevated blood glucose levels in DM patients (Date et al., 2015; Yadav, 2013). α-amylase active at neutral to mildly acidic pH, catalyzes polysaccharide (starch and glycogen) hydrolysis into glucose for digestion. Elevated α-amylase leads to increased sugar levels, and regulating it can reduce hyperglycaemia (Khan et al., 2022) and help to manage further complications, such as diabetic retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy. Epidemiological research has shown that those with DM are more likely to develop AD (Barbagallo, 2014; Silva et al., 2019). The most prevalent and widely accepted treatment strategy for AD is to maintain the ACh level in the post-synaptic neuronal junction via inhibition of AChI, which breaks down ACh into acetate and choline, helps in the accumulation of Aβ, and colocalizes with hyperphosphorylated tau (P-tau) within neurofibrillary tangles (H. Ferreira-Vieira et al., 2016). This study explored the α-amylase and AChE inhibitory potential of various sequentially extracted Mazus pumilus extracts. Our results showed that the MeOH extract had significant inhibitory potential against both α-amylase and AChI. (Table 2). The percent inhibition of α-amylase and AChE by different extracts of Mazus pumilus is presented in Fig. 3. These results are in line with previous studies that reported the remarkable inhibitory potential of these enzymes in more polar plant extracts (Akhter et al., 2013; Iftikhar et al., 2019; Kidane et al., 2018). Hence, the capacity of the MeOHextract to inhibit enzymes could potentially be attributed to the existence of diverse secondary metabolites including phenols, and flavonoids. Undoubtedly, the standard drugs for DM (carbohydrate metabolizing enzyme inhibitors, glinides, sulfonylureas, and thiazolidinediones) (Nathan et al., 2009) and AD (tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine) (H. Ferreira-Vieira et al., 2016) are more effective at lower concentrations. Still, their long-term use causes several adverse effects, including hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and hypoglycaemia (Chaudhury et al., 2017; Colovic et al., 2013). However, numerous studies have reported that antihyperglycemic drugs reduce the risk of dementia (Campbell et al., 2018; Michailidis et al., 2022). Currently, no FDA-approved medication is capable of simultaneously addressing hyperglycaemia and Alzheimer's disease by targeting both α-amylase and AChE. In this context, sequentially extracted Mazus pumilus extracts display notable effects against diabetes and Alzheimer's disease by specifically targeting α-amylase, and AChE holds significant importance.

Percent inhibition graph of α-amylase and AChE by different extract of Mazus pumilus. MeOH extract was found to be most significant when compared to the other solvent extracts. All the experiments were performed in triplicate and data are expressed as mean ± SD..

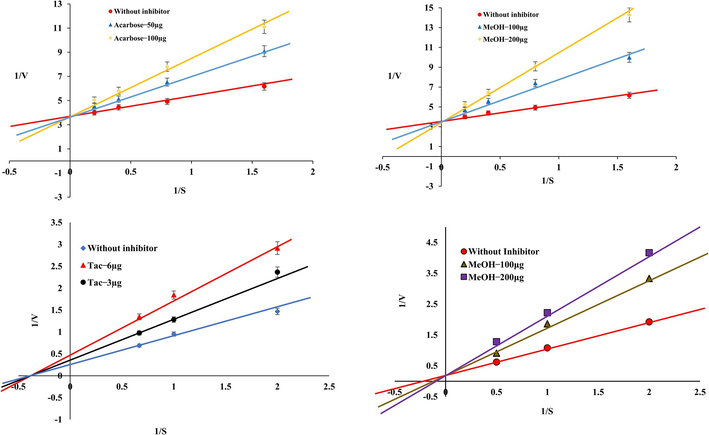

We also investigated enzyme kinetics to unravel the MeOH extract's inhibitory mechanism on α-amylase and AChE. Our findings revealed that the MeOH extract functioned as a competitive inhibitor of α-amylase, similar to the behaviour of the standard acarbose. In the case of AChE, this extract also exhibited competitive inhibition, in contrast to the standard tacrine, which demonstrated a non-competitive nature. This distinction is evident from the Lineweaver–Burk double reciprocal plot of 1/V vs. 1/[S] (Fig. 4). These outcomes were consistent with previous research on standard compounds. It is noteworthy that plant extracts often manifest competitive and non-competitive inhibition due to the presence of diverse bioactive compounds. Non-competitive inhibition is characterized by a decrease in Vmax without affecting Km, distinguishing it from competitive inhibition, where Vmax remains unchanged, and Km increases (Rodriguez and Towns, 2019).

Enzyme Kinetics studies of α-amylase and AChE in the presence or absence of inhibitor.Mazus pumilus The reference drugs acarbose and tacrine was served as reference standard. The inhibition modes were assessed using varying concentrations of substrate and inhibitors, the Lineweaver–Burk plot generated from 1/S vs. 1/V values. These plots indicate that the MeOH extract competitively inhibits α-amylase and AChE activities.

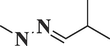

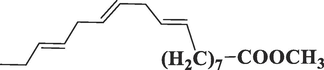

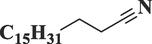

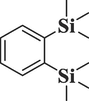

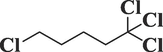

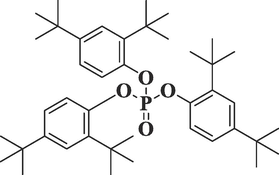

3.4 Identification of compounds via GC–MS analysis

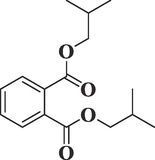

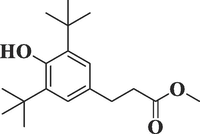

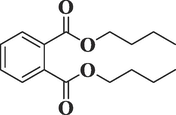

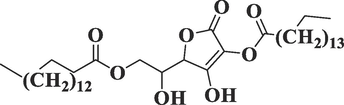

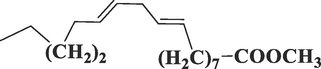

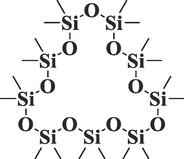

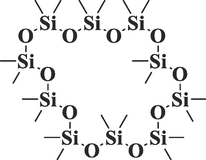

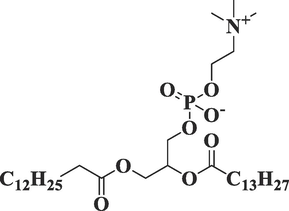

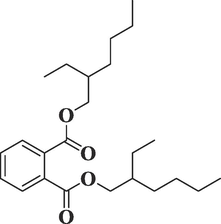

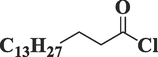

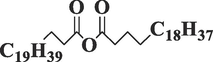

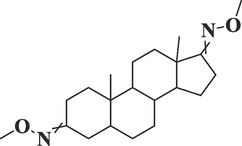

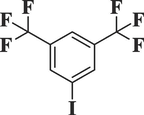

The MeOH extract was also subjected to GC–MS analysis to identify the potential bioactive compounds that might be accountable for the aforementioned observed effects. Initially, 36 compounds were identified (Table3), of which three major compounds (5, 16, and 36) were found with % areas of 26.11, 8.02, and 8.29, respectively (Supplementary file 1). Incredibly, we are the first to uncover the compound detected through GC–MS in the MeOH extract of Mazus pumilus. Mazus pumilus (Table 3). *Retention time.

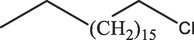

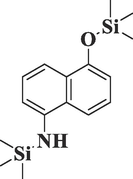

S.No.

PubChem ID

Compounds Name and Structures

Chemical Formula

Molecular Weight

R.T.*

Area %

Class of the compound

1.

567,578

Isobutyraldehyde methylhydrazoneC5H12N2

100

11.156

3.45

Hydrazone

2.

12,391

PentadecaneC15H32

212

20.286

0.69

Aliphatic hydrocarbon

3.

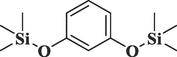

300,668

Resorcinol, 2TMS derivativeC12H22O2Si2

254

22.224

0.57

Phenol

4.

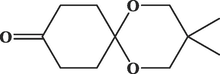

587,968

1,5-Dioxaspiro [5.5] undecan-9-one, 3,3-dimethylC11H18O3

198

22.780

0.74

Spiroacetal

5.

7311

2,4-Di-tert-butylphenolC14H22O

206

23.233

26.11

Phenol

6.

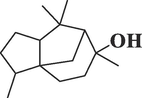

65,575

CedrolC15H26O

222

23.666

1.07

Sesquiterpene

7.

18,815

Octadecane, 1-chloro-C18H37Cl

288

23.815

0.53

Alkyl-halide

8.

627,489

3-tert-Butyl-4-hydroxyanisole, acetateC13H18O3

222

24.642

1.17

Phenol

9.

11,006

HexadecaneC16H34

226

25.499

0.59

Alkane

10.

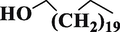

12,620

Behenic alcoholC22H46O

326

30.080

2.43

Fatty alcohol

11.

5,364,523

Eicosen-1-ol, cis-9-C20H40O

296

30.956

2.43

Fatty alcohol

12.

6782

Phthalic acid, diisobutyl esterC16H22O4

278

31.458

3.33

Phthalates

13.

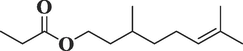

8834

Citronellyl propionateC13H24O2

212

31.833

0.86

Terpenoid

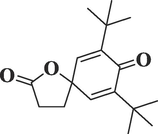

14.

545,303

7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro (4,5) deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dioneC17H24O3

276

32.454

2.79

Spiro

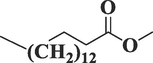

15.

8181

Hexadecanoic acid, methyl esterC17H34O2

270

32.838

2.41

Lipid

16.

62,603

Benzenepropanoic acid, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)

Benzenepropanoic acid, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)

-4-hydroxy-, methyl esterC18H28O3

292

32.937

8.02

Esters

17.

3026

Dibutyl phthalateC16H22O4

278

33.470

2.66

Phthalic acid esters

18.

54,722,209

l-

l-

(+)-Ascorbic acid 2,6-dihexadecanoateC38H68O8

652

33.664

2.54

Ester

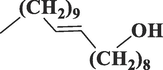

19.

5,284,421

9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)

9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (Z,Z)

-, methyl esterC19H34O2

294

36.203

1.17

Ester

20.

5,367,462

9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, methyl esterC19H32O2

292

36.204

1.73

Ester

21.

5,280,435

PhytolC20H40O

296

36.544

1.63

Terpenoid

22.

110,444

Methyl isostearateC19H38O2

298

36.849

0.82

Ester

23.

68,406

OctacosanolC28H58O

410

38.137

0.58

Alcohol

24.

11,172

Cyclononasiloxane, octadecamethyl-C18H54O9Si9

666

38.261

0.35

Organosilicon

25.

519,601

Cyclodecasiloxane, eicosamethyl-C20H60O10Si10

740

40.646

0.25

Organosilicon

26.

26,197

DimyristoyllecithinC36H72NO8P

677

41.293

0.36

Phospholipid

27.

8343

Bis(2-ethylhexyl)

Bis(2-ethylhexyl)

phthalateC24H38O4

390

43.956

0.59

Phthalates

28.

8206

Palmitoyl chlorideC16H31ClO

274

44.488

1.20

Lipid

29.

566,696

Docosanoic anhydrideC44H86O3

662

47.464

1.95

Lipid

30.

5,497,165

9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)

9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)

-, 2-hydroxy-1,3-propanediyl esterC39H72O5

620

52.864

1.96

Glycerides

31.

91,742,317

Androstane-3,17-dione,

Androstane-3,17-dione,

(5.beta.)C19H28O2

288

55.647

0.33

Steroid

32.

630,970

3–5-di (Trifluoromethyl) iodobenzeneC8H3F6I

340

55.677

0.23

Aromatic Halo-compounds

33.

12,532

OctadecanenitrileC18H35N

265

57.380

0.31

Lipid

34.

519,794

1,2-Bis(trimethylsilyl)

1,2-Bis(trimethylsilyl)

benzeneC12H22Si2

222

58.683

0.12

Organosilane

35.

17,175

Pentane, 1,1,1,5-tetrachloro-C5H8Cl4

208

59.866

0.44

Alkyl-halide

36.

14,572,930

Tris

Tris

(2,4-di-tert-butylphenyl) phosphateC42H63O4P

662

60.166

8.29

Terpenes

3.5 Pharmacokinetic profiling of the detected compounds

Based on our findings, we hypothesize that the bioactive compounds present in the MeOH extract derived from Mazus pumilus, whether acting individually or in synergy, play a significant role in mitigating oxidative damage and impeding the actions of α-amylase and AChE. Nevertheless, the most pivotal phase in drug development involves forecasting the pharmacological attributes of a chemical entity, a process that can be effectively facilitated using diverse AI-based tools (Jiménez-Luna et al., 2020). Among these methodologies, ADMET holds prominence as it aids in pre-emptively assessing pharmacokinetic and toxicological characteristics, thereby preventing the unnecessary expenditure of time, resources, and human effort (Ahmad et al., 2021). This study evaluated drug-like attributes of GC–MS-identified compounds—the assessment of Lipinski's rule of five, bioactivity profile, and ADMET properties (Mahgoub et al., 2022). The five distinct criteria outlined in Lipinski's rule, which include a molecular weight below 500 Da, fewer than five hydrogen bond donors (HBD), fewer than ten hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), and a Log P (partition coefficient between octanol and water) below 5, were individually appraised for each compound. In the early stages, a subset of 19 compounds (s.no. 1,3,4,5,6,8,12,13,14,15,16,17,19,20,22,27,31,34,35,36) exhibited the potential for either high intestinal absorption, blood–brain barrier permeability, or both (Table 4). In which compound no. 15,19,20,22,27 is violated the one of the Lipinski’s rules that is MlogP < 4.15. However, this violation was not sufficient to exclude these compounds from the study. Other compounds that were not found to have any of the above-mentioned potentials were eliminated at this stage.

S.No.

PubChem ID

Log P

HIA

BBB

HBA

HBD

Rotatable Bonds

Violation

1.

567,578

1.65

High

Yes

1

1

2

0

2.

12,391

4.5

Low

No

0

0

12

1

3.

300,668

3.84

High

Yes

2

0

4

0

4.

587,968

2.28

High

Yes

3

0

0

0

5.

7311

3.08

High

Yes

1

1

2

0

6.

65,575

3.03

High

Yes

1

1

0

0

7.

18,815

5.22

Low

No

0

0

16

1

8.

627,489

3.84

High

Yes

1

1

4

0

9.

11,006

4.67

Low

No

0

0

13

1

10.

12,620

5.73

Low

No

1

1

20

1

11.

5,364,523

5.15

Low

No

1

1

17

1

12.

6782

3.31

High

Yes

4

0

8

0

13.

8834

3.57

High

Yes

2

0

8

0

14.

545,303

2.91

High

Yes

3

0

2

0

15.

8181

4.41

High

Yes

2

0

15

1

16.

62,603

3.75

High

Yes

3

1

6

0

17.

3026

2.97

High

Yes

4

0

10

0

18.

54,722,209

7.58

Low

No

8

2

34

2

19.

5,284,421

4.61

High

No

2

0

15

1

20.

5,367,462

4.94

High

Yes

2

0

14

1

21.

5,280,435

4.71

Low

No

1

1

13

1

22.

110,444

5.12

High

No

2

0

16

1

23.

68,406

7.2

Low

No

1

1

26

1

24.

11,172

6.01

Low

No

9

0

0

1

25.

519,601

6.55

Low

No

10

0

0

1

26.

26,197

2.54

Low

No

8

0

36

1

27.

8343

4.77

High

No

4

0

16

1

28.

8206

4.49

Low

No

1

0

14

1

29.

566,696

10.4

Low

No

3

0

42

2

30.

5,497,165

8.8

Low

No

5

1

36

2

31.

91,742,317

4.04

High

Yes

4

0

2

0

32.

630,970

2.43

Low

No

6

0

2

1

33.

12,532

4.64

Low

No

1

0

15

1

34.

519,794

3.27

Low

Yes

0

0

2

0

35.

17,175

2.4

Low

Yes

0

0

4

0

36.

14,572,930

6.93

Low

No

4

0

12

2

3.6 Toxicity assessment of the selected compounds

Furthermore, the Selected compound was subjected to the toxicity assessment using the ProTox-II platform ((Banerjee et al., 2018). Our results depicted that all of the substances fell within the range of Classified LD50 value (Table 5). Furthermore, compounds 1, 7, 16, 18, and 19 were active against carcinogenicity, whereas compounds 6 and 12 demonstrated immunotoxicity—notably, compound 11 displayed hepatotoxicity. In contrast, compounds numbered 5 and 17 were found to be associated with hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and mutagenicity, respectively. As a result, these compounds were disregarded at this point for additional docking investigation.

S.No.

PubChem ID

LD50 (mg/kg)

Toxicity Class

Hepatotoxicity

Carcinogenicity

Immunotoxicity

Mutagenicity

Cytotoxicity

1.

567,578

460

4

Inactive

Active

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

2.

300,668

300

3

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

3.

587,968

10,000

6

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

4.

7311

700

4

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

5.

65,575

1190

4

Active

Inactive

Active

Inactive

Inactive

6.

627,489

25

2

Inactive

Inactive

Active

Inactive

Inactive

7.

6782

10,000

6

Inactive

Active

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

8.

8834

5000

5

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

9.

545,303

900

4

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

10.

8181

5000

5

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

11.

62,603

5000

5

Active

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

12.

3026

3474

5

Inactive

Active

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

13.

5,284,421

20,000

6

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

14.

5,367,462

20,000

6

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

15.

110,444

5000

5

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

16.

8343

1340

4

Inactive

Active

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

17.

91,742,317

1400

4

Inactive

Active

Inactive

Active

Inactive

18.

519,794

1535

4

Inactive

Active

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

19.

17,175

800

4

Inactive

Active

Inactive

Inactive

Inactive

3.7 Molecular docking studies

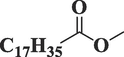

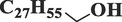

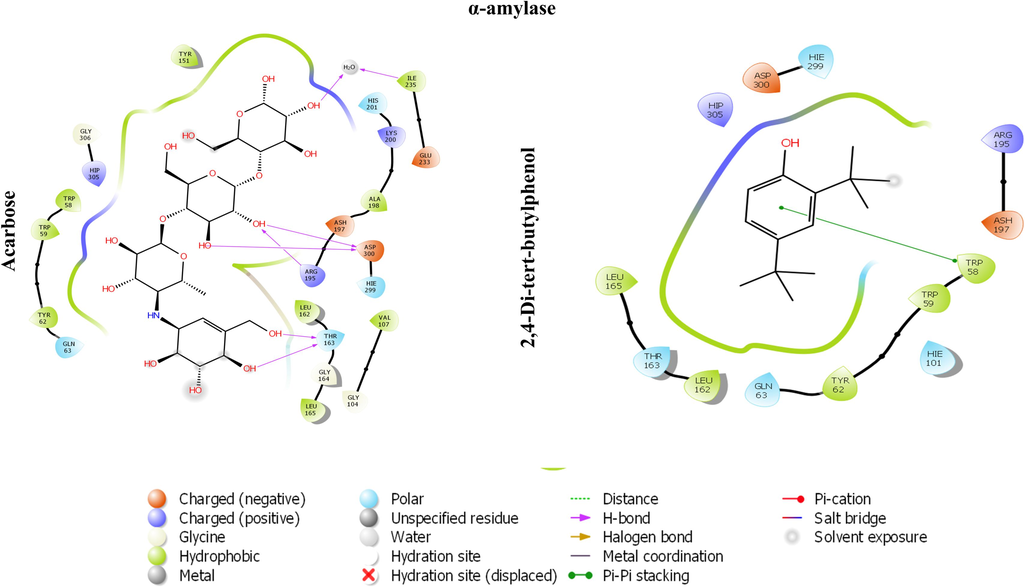

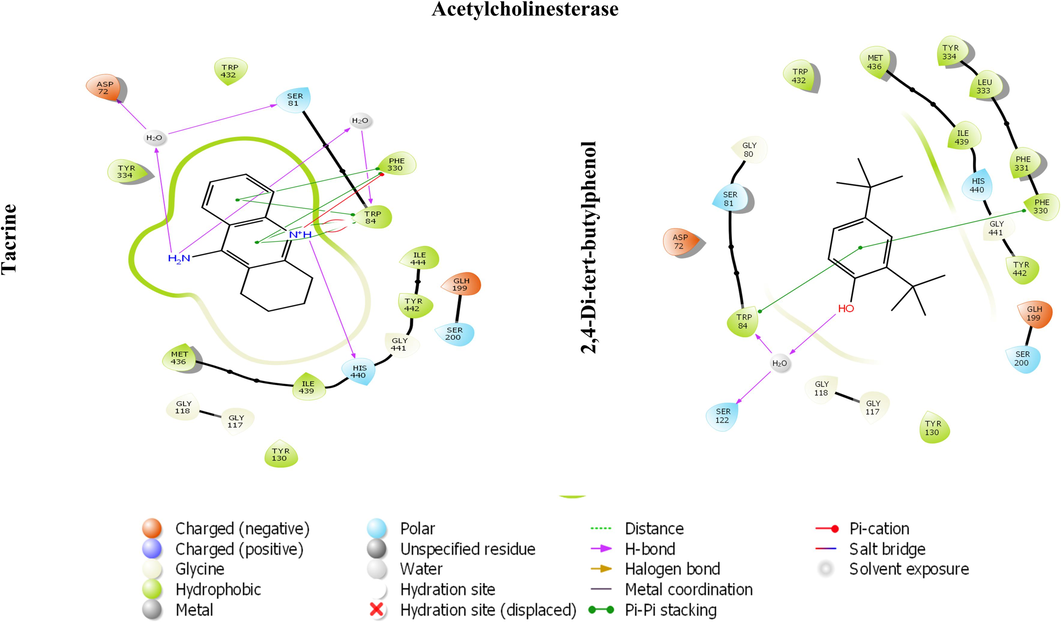

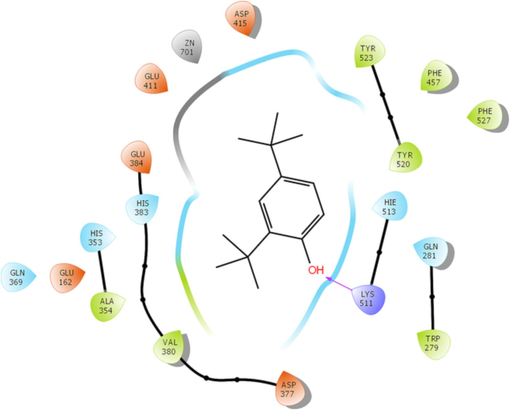

The chosen compounds present in the MeOH extract were docked within the active pocket of α-amylase and AChE. The docking analyses have been widely used to identify the molecular targets of plant extract constituents (Ahmad et al., 2022, 2021).Investigation of the interaction between ligands and a target protein using molecular docking is an essential tool for understanding the underlying processes determining their inhibitory and binding capabilities. In this attempt, we observed that selected compounds occupied the active pocket of the α-amylase and AChE. The binding energy values were ranging from − 0.405 to − 6.109 kcal/mol (Table 6) and − 1.967 to − 8.007 kcal/mol for α-amylase and AChE, respectively. In contrast, the standard drugs acarbose and tacrine showed binding energies of − 7.872 and − 11.519, respectively, for α-amylase and AChE. Our results demonstrated that 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol most efficiently occupied the catalytic sites of α-amylase and AChE, with binding affinities of − 6.109 and − 8.007, respectively (Table 6 and 7). The 13 amino acid residues (ARG195, ASH197, TRP58, TRP59, HIE101, TYR62, GLN63, LEU162, THR163, LEU165, HIP305, ASP300, HIE299) and docked complex of AChE with same ligand was surrounded by 20 residues (MET436, ILE439, HIS440, GLY441, TYR442, GLH199, SER200, TYR130, GLY117, GLY118, SER122, TRP84, ASP72, SER81, GLY80, TRP432, TYR334, LEU333, PHE331, PHE330) (Figs. 5 and 6). The polyhydroxy acarbose molecule was interacted with the ILE 235, ASP 300, and THR 163 amino residues by their active sites of the protein as well as the ligand’s hydroxy groups. On the contrary, 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol ligand was interacted with the TRP 58 residue of amino acid by the pi-electrons and generated pi-pi stacking forces. The tacrine (1,2,3,4-tetrahydroacridin-9-amine) ligand was docked with the acetylcholinesterase protein using Schrodinger. After docking, we found that the active sites of the tacrine molecule, which is used as a ligand, interacted with various amino acid residues by hydrogen bonding, metal coordination, pi-pi stacking, etc. In the docked complex, the ligand has a primary amino group at the C-9 position of tacrine that was bonded to the three amino acid residues (ASP 72, SER 81, and TRP 84) by hydrogen bonding.. Similarly, secondary amine, which is present at the acridin ring of tacrine, was also bonded to the HIS440 residue through hydrogen bonding. Moreover, pi-pi stacking was also observed among the pi-electrons circulation and the PHE 330 and TRP 84 protein residues. In the docked complex of 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol and AChE, we noted only two types of interactions: hydrogen bonding and pi-pi stacking. The SER 112 residue is interacted with the help of hydrogen bonding which is possible by the hydroxyl group, presented at the para-position of the 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol ligand. Moreover, two amino acid residues, TRP 84 and PHE 330, also interacted with the pi-electrons by pi-pi stacking. While all the chosen compounds engaged with the catalytic sites of both target enzymes, leading to the inhibition of their activities, it remains uncertain whether all or only a subset of these compounds contribute to the effective inhibitory action of the extract. Further extending the in-silico study, we have performed the molecular docking with crystal structure of human Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE), PDB ID- 1O8A. ACE play a vital role in the control of blood pressure. Emerging empirical data suggests that pharmacological interventions targeting the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) offer distinctive advantages, not only for individuals’ post-myocardial infarction and those suffering from congestive heart failure, but also for individuals with hypertension concomitant with the cardiometabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus (McFarlane et al., 2003). Our results depicted that 4 compounds occupied the active pocket of ACE in which 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol was the best with highest binding affinity of −6.030 Kcal/mol (Table. 8). The complex structure was stabilized by 18 amino acid residues; TYR523, PHE457, PHE527, TYR520, HIE513, LYS511, GLN281, TRP279, ASP377, VAL380, ALA354, GLU162, HIS353, HIS383, GLU384, GLU411, ZN701, ASP415 (Fig. 7). Nevertheless, the outcomes of our laboratory-based and computational investigations underscore the potential of the MeOH extract from Mazus pumilus to have antidiabetic and anti-Alzheimer properties. *Standard. *Standard.

S. No.

CID

Binding energy

Interacting amino acid

1.

587,968

−6.109

GLU233, HIE299, ASP300, ALA198, ASH197, ARG195, TYR62, TRP59, TRP58, LEU162, THR163, LEU165.

2.

7311

−5.713

ARG195, ASH197, TRP58, TRP59, HIE101, TYR62, GLN63, LEU162, THR163, LEU165, HIP305, ASP300, HIE299.

3.

545,303

−4.854

TYR151, ARG195, ASH197, ALA198, VAL98, HIE101, HIE299, ASP300, TYR62, TRP59, TRP58, LEU165, THR163, LEU162, HIP305.

4.

300,668

−4.395

HIE299, ASP300, GLU233, ILE235, ARG195, ASH197, ALA198, HIS201, LEU162, THR163, LEU165, GLN63, TYR62, GLU60, TRP59, TRP58, HIP305.

5.

8834

−0.698

VAL98, HIE101, ALA198, ASH197, ARG195, LEU162, THR163, LEU165, GLN63, TYR62, TRP59, TRP58, HIP305, ASP300, HIE299, GLU233.

6.

5,284,421

−0.304

HIS201, LYS200, ALA198, ASH197, ARG195, LEU162, LEU165, GLN63, TYR62, GLU60, TRP59, TRP58, HIE101, HIE299, ASP300, GLU233, ILE235, GLU240, TYR151.

7.

110,444

−0.108

HIS201, LYS200, ALA198, ASH197, ARG195, ILE235, GLU233, LEU162, THR163, LEU165, HIE101, GLY104, ILE51, GLN63, TYR62, TRP59, TRP58, HIE299, ASP300, GLU290, TYR151.

8.

5,367,462

−0.275

TYR151, HIS201, LYS200, ALA198, ASH197, ARG195, ILE235, GLU233, LEU162, THR163, GLY164, LEU165, HIE101, GLY104, ALA106, VAL106, ILE51, GLU63, TYR62, HIP305, TRP59, TRP58, ASP300, HIE299.

9.

8181

−0.405

TYR151, HIS201, LYS200, ALA198, ASH197, ARG195, ILE235, GLU233, HIE101, HIE299, ASP300, TRP58, TRP59, GLU60, TYR62, GLN63, LEU165, LEU162.

10.

41774*

−7.872

TYR151, ILE235, GLN233, HIS201, LYS200, ALA198, ASH197, ARG195, ASP300, HIE299, LEU162, THR163, GLY164, LEU165, VAL107, GLY104, GLU63, TYR62, TRP59, TRP58, HIP305, GLY306.

S. No.

CID

Binding energy

Interacting amino acid

1.

587,968

−6.444

TYR334, MET436, PHE330, TRP432, GLH199, SER200, GLY119, GLY118, GLY117, ILE444, TYR442, GLY441, HIS440, ILE439, TYR130, TRP84, SER81, GLY80.

2.

7311

−8.007

MET436, ILE439, HIS440, GLY441, TYR442, GLH199, SER200, TYR130, GLY117, GLY118, SER122, TRP84, ASP72, SER81, GLY80, TRP432, TYR334, LEU333, PHE331, PHE330.

3.

545,303

−5.227

TYR121, PHE330, PHE331, TYR334, GLY335, LEU282, TRP279, SER286, ILE287, PHE288, ARG289, PHE290.

4.

300,668

−5.157

TYR334, LEU333, PHE331, PHE330, TRP432, TYR130, GLH199, SER200, GLY117, GLY118, GLY119, TYR121, SER122, ASP72, TRP84, SER81, GLY80, MET436, ILE439, HIS440, GLY441, TYR442, ILE444.

5.

8834

−3.196

TYR334, LEU333, PHE331, PHE330, GLH199, SER20, TYR121, GLY119, GLY118, GLY117, PHE288, PHE290, TYR442, GLY441, HIS440, ILE439, MET436, TRP84, SER81, GLY80, TRP432.

6.

5,284,421

−3.716

PHE330, PHE331, TYR334, GLY117, GLY118, GLY119, TYR121, SER122, GLN199, SER200, ILE287, PHE288, ARG289, PHE290, LEU282, TRP279, TRP84, ASP72, TRP432, SER81, GLY80, ILE439, HIS440, GLY441, TYR442.

7.

110,444

−2.224

TRP432, GLY80, SER81, TRP84, MET436, ILE439, HIS440, GLY441, TYR442, GLY117, GLY118, GLY119, TYR121, SER122, GLH199, SER200, ALA201, PHE290, ARG289, TRP279, PHE288, ILE287, GLY335, TYR334, PHE331, PHE330.

8.

5,367,462

−1.977

TRP432, PHE330, PHE331, LEU333, TY334, GLY335, ILE287, PHE288, ARG289, PHE290, LEU282, TRP279, SER122, TYR121, GLY119, GLH199, SER200, GLY118, GLY117, TYR442, GLY441, HIS440, ILE439, TRP84, SER81, GLY80.

9.

8181

−1.967

ILE444, TYR442, GLY441, HIS440, ILE439, MET436, TRP84, SER81, GLY80, TRP432, PHE330, PHE331, TYR334, ILE287, PHE288, ARG289, PHE290, LEU282, TRP289, TYR121, GLY119, GLY118, GLY117, ALA201, SER200, GLH199.

10.

1935*

−11.519

TRP432, SER81, PHE330, TRP84, ILE444, TYR442, GLY441, HIS440, ILE439, MET436, GLH199, SER200, GLY119, GLY118, GLY117, TYR130, TYR334, ASP72.

The 2D image represents the in-silico binding pattern of (A) acarbose and (B) 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol within the active pocket of α-amylase crystal structure.

The 2D image represents the in-silico binding pattern of (A) Tacrine and (B) 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol within the active pocket of AChE crystal.

S. No.

CID

Binding energy

Interacting amino acid

1.

587,968

−4.835

TYR520, TYR523, ZN701, ALA354, HIS353, LYS511, HIE513, GLN281, THR282, VAL379, VAL380, HIS383, ASP415, ASP453, LYS454, PHE457, PHE527.

2.

7311

−6.030

TYR523, PHE457, PHE527, TYR520, HIE513, LYS511, GLN281, TRP279, ASP377, VAL380, ALA354, GLU162, HIS353, HIS383, GLU384, GLU411, ZN701, ASP415.

3.

545,303

−5.119

PHE527, TYR520, TYR523, PHE457, THR282, GLN281, TRP279, ASP377, VAL179, VAL380, GLN369, HIS353, LYS511, HIS383, ALA354, HIE 513, GLU162, GLU384, GLU411, HIS387, ZN701, VAL518.

4.

300,668

−4.641

LYS454, TYR523, ASP415, PHE457, TYR520, GLN281, TRP279, HIE513, LYS511, GLN369, HIS353, ALA354, GLU169, ASP377, VAL379, VAL380, HIS383, GLU384, PHE527.

2D image representation of stabilized complex structure of ACE by 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol.

4 Conclusion

Mazus pumilusBased on the results obtained from our in-vitro and in-silico investigations, we have concluded that Mazus pumilus extract and its secondary metabolites could fend against diabetes and Alzheimer by impeding the α-amylase and AChE. Furthermore, it is unequivocally evident that the MeOH extract exhibits robust antioxidant efficacy against DPPH (IC50:19.45 ± 1.32 µg/mL) and ABTS radical (IC50:20.54 ± 1.81 µg/mL).The study was substantiated through molecular docking studies involving compounds identified via GC–MS with the crystal structures of α-amylase and AChE. The binding energies for α-amylase and AChE were ranging from − 0.405 to − 6.109 kcal/mol and − 1.967 to − 8.007 kcal/mol, respectively. Consequently, utilizing the full spectrum of these compounds/extracts could serve as a promising strategy for mitigating oxidative stress and hyperglycaemia, along with addressing Alzheimer's. However, it is imperative to conduct in-vivo investigation to grasp the roles of these extracts and their bioactive components.

Author contribution statement

SA S Alouffi and US conceived and designed research. MW and MSK conducted formal analysis and investigations. MEG, RA, MKA and SA analyzed data. NA SA MSK and MW wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Hail - Saudi Arabia through project number RG- 23 142.

Funding source

This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Hail - Saudi Arabia through project number RG- 23 142.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Identification and evaluation of natural organosulfur compounds as potential dual inhibitors of α-amylase and α-glucosidase activity: an in-silico and in-vitro approach. Med. Chem. Res.. 2021;30:2184-2202.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Target-Based Virtual and Biochemical Screening Against HMG-CoA Reductase Reveals Allium sativum-Derived Organosulfur Compound N-Acetyl Cysteine as a Cardioprotective Agent. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn.. 2022;2022:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant, α-amylase inhibitory and oxidative DNA damage protective property of Boerhaavia diffusa (Linn.) root. South African J. Bot.. 2013;88:265-272.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alvi, S.S., Ahmad, P., Ishrat, M., Iqbal, D., Khan, M.S., 2019. Secondary Metabolites from Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.): Structure, Biochemistry and Therapeutic Implications Against Neurodegenerative Diseases, in: Natural Bio-Active Compounds. Springer Singapore, pp. 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7205-6_1.

- Molecular rationale delineating the role of lycopene as a potent HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor: in vitro and in silico study. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2016;30:2111-2114.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Free-radical scavenging capacity and antioxidant activity of selected plant species from the Canadian prairies. Food Chem.. 2004;84:551-562.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Computational Study Reveals the Inhibitory Effects of Chemical Constituents from Azadirachta indica (Indian Neem) Against Delta and Omicron Variants of SARS-CoV-2. Coronaviruses. 2022;3

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res.. 2018;46:W257-W263.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer’s disease. World J. Diabetes. 2014;5:889.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem.. 1996;239:70-76.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes and related complications: Current therapeutics strategies and future perspectives. Free Radic. Biol. Med.. 2022;184:114-134.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT - Food Sci. Technol.. 1995;28:25-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metformin Use Associated with Reduced Risk of Dementia in Patients with Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis.. 2018;65:1225-1236.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-Cholinesterase and Anti-α-Amylase Activities and Neuroprotective Effects of Carvacrol and p-Cymene and Their Effects on Hydrogen Peroxide Induced Stress in SH-SY5Y Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2023;24:6073.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical Review of Antidiabetic Drugs: Implications for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Management. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne).. 2017;8:6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Amyloid beta: structure, biology and structure-based therapeutic development. Acta Pharmacol. Sin.. 2017;38:1205-1235.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors: Pharmacology and Toxicology. Curr. Neuropharmacol.. 2013;11:315.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J., Mumper, R.J., 2010. Plant Phenolics: Extraction, Analysis and Their Antioxidant and Anticancer Properties. Mol. 2010, Vol. 15, Pages 7313-7352 15, 7313–7352. 10.3390/MOLECULES15107313.

- SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep.. 2017;7:42717.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pancreatic α-Amylase Controls Glucose Assimilation by Duodenal Retrieval through N-Glycan-specific Binding, Endocytosis, and Degradation. J. Biol. Chem.. 2015;290:17439-17450.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular docking analysis of phyto-constituents from Cannabis sativa with pfDHFR. Bioinformation. 2018;14:574-579.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Type 2 Diabetes Alternative Therapies for Type 2 Diabetes. Altern. Med. Rev.. 2002;x 7

- [Google Scholar]

- A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem. Pharmacol.. 1961;7:88-95.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- H. Ferreira-Vieira, T., M. Guimaraes, I., R. Silva, F., M. Ribeiro, F., 2016. Alzheimer’s disease: Targeting the Cholinergic System. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 14, 101–115. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159x13666150716165726.

- Plant α-amylase inhibitors and their interaction with insect α-amylases. Eur. J. Biochem.. 2002;269:397-412.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Revisiting the role of acetylcholinesterase in Alzheimers disease: Cross-talk with β-tau and p-amyloid. Front. Mol. Neurosci.. 2011;4

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative Stress and Diabetic Complications. Circ. Res.. 2010;107:1058-1070.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Drug design by the method of receptor fit. J. Med. Chem.. 1984;27:557-564.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Role of Amyloid-β and Tau Proteins in Alzheimer’s Disease: Confuting the Amyloid Cascade. J. Alzheimer’s Dis.. 2018;64:S611-S631.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Haan, M.N., 2006. Therapy Insight: type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Clin. Pract. Neurol. 2006 23 2, 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpneuro0124.

- The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Psychiatry. 2021;26:5481-5503.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harborne, J.B. (Jeffrey B.., 1998. Phytochemical methods : a guide to modern techniques of plant analysis. Chapman and Hall.

- Phyllanthus virgatus forst extract and it’s partially purified fraction ameliorates oxidative stress and retino-nephropathic architecture in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2019;32:2697-2708.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, A., Khan, M. Salman, Khan, Mohd Sajid, Baig, M.H., Ahmad, S., 2013. Antioxidant and α; ylase inhibitory property of phyllanthus virgatus L.: An in vitro and molecular interaction study. Biomed Res. Int. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/729393.

- Study of Phytochemicals of Melilotus indicus and Alpha-Amylase and Lipase Inhibitory Activities of Its Methanolic Extract and Fractions in Different Solvents. ChemistrySelect. 2019;4:7679-7685.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Acetylcholinesterase Accelerates Assembly of Amyloid-β-Peptides into Alzheimer’s Fibrils: Possible Role of the Peripheral Site of the Enzyme. Neuron. 1996;16:881-891.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, D., Khan, M.S., Waiz, M., Rehman, M.T., Alaidarous, M., Jamal, A., Alothaim, A.S., Alajmi, M.F., Alshehri, B.M., Banawas, S., Alsaweed, M., Madkhali, Y., Algarni, A., Alsagaby, S.A., Alturaiki, W., 2021. Exploring the Binding Pattern of Geraniol with Acetylcholinesterase through In Silico Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulation, and In Vitro Enzyme Inhibition Kinetics Studies. Cells 2021, Vol. 10, Page 3533 10, 3533. https://doi.org/10.3390/CELLS10123533.

- Mazus pumilus (Burm. f.) Steenis; pharmacognosy. Indian J. Tradit. Knowl.. 2018;17:106-112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of anti-nociceptive, anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective effects of methanol extract of Mazus pumilus (Burm. f.) Steenis (Mazaceae) herb. Trop. J. Pharm. Res.. 2018;18:799-807.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Drug discovery with explainable artificial intelligence. Nat. Mach. Intell.. 2020;2:573-584.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Drug discovery from plant sources: An integrated approach. AYU (An Int. q. J. Res. Ayurveda). 2012;33:10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, X-ray diffraction analysis, quantum chemical studies and α -amylase inhibition of probenecid derived S -alkylphthalimide-oxadiazole-benzenesulfonamide hybrids. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem.. 2022;37:1464-1478.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Exploring Probenecid Derived 1,3,4-Oxadiazole-Phthalimide Hybrid as α-Amylase Inhibitor: Synthesis, Structural Investigation, and Molecular Modeling. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16:424.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In Vitro Inhibition of α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase by Extracts from Psiadia punctulata and Meriandra bengalensis. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med.. 2018;2018

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Relationship between Alzheimer’s Disease and Diabetes: Type 3 Diabetes^. Altern. Med. Rev.. 2009;14:373-379.

- [Google Scholar]

- Leicach, S.R., Chludil, H.D., 2014. Plant Secondary Metabolites. pp. 267–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63281-4.00009-4.

- Mahgoub, R.E., Atatreh, N., Ghattas, M.A., 2022. Using filters in virtual screening: A comprehensive guide to minimize errors and maximize efficiency. pp. 99–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.armc.2022.09.002.

- Mechanisms by which angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors prevent diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Cardiol.. 2003;91:30-37.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic Drugs in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2022;23

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In silico molecular modeling and docking studies on the leishmanial tryparedoxin peroxidase. Brazilian Arch. Biol. Technol.. 2014;57:244-252.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Glycation and HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitors: Implication in Diabetes and Associated Complications. Curr. Diabetes Rev.. 2019;15:213-223.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ezetimibe attenuates experimental diabetes and renal pathologies via targeting the advanced glycation, oxidative stress and AGE-RAGE signalling in rats. Arch. Physiol. Biochem.. 2021;1–16

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes: A Consensus Algorithm for the Initiation and Adjustment of Therapy: A consensus statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:193.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- P, S., Zinjarde, S.S., Bhargava, S.Y., Kumar, A.R., 2011. Potent α-amylase inhibitory activity of Indian Ayurvedic medicinal plants. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 11, 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-11-5.

- In Silico Assessment of Potential Druggable Pockets on the Surface of α1-Antitrypsin Conformers. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36612.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of anticancer activity of Mazus pumilus leaf extracts on selected human cancerous cell lines. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res.. 2016;37:185-189.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med.. 1999;26:1231-1237.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Neurodegenetive disorders associated with diabetes mellitus. J. Mol. Med.. 2004;82:510-529.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of student reasoning about Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetics: mixed conceptions of enzyme inhibition. Chem. Educ. Res. Pract.. 2019;20:428-442.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial evaluation of three widespread weeds Mazus japonicus, Fumaria indica and Vicia faba from. Res. Pharm.. 2015;5:1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Shahid, S., Riaz, T., Athar Abbasi, M., Khalid, F., Nadeem Asghar, M., 2013. 593 In Vitro Assessment of Protection from Oxidative Stress by Various Fractions of Mazus pumilus. J.Chem. Soc. Pak 35.

- Shaikh, J.R., Patil, M., 2020. Qualitative tests for preliminary phytochemical screening: An overview. Int. J. Chem. Stud. 8, 603–608. https://doi.org/10.22271/chemi.2020.v8.i2i.8834.

- Ethnomedicinal plants used for treating epilepsy by indigenous communities of sub-Himalayan region of Uttarakhand. India. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2013;150:353-370.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Drug repositioning to discover novel ornithine decarboxylase inhibitors against visceral leishmaniasis. J. Mol. Recognit. 2023

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.V.F., Loures, C.D.M.G., Alves, L.C.V., De Souza, L.C., Borges, K.B.G., Carvalho, M.D.G., 2019. Alzheimer’s disease: risk factors and potentially protective measures. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019 261 26, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12929-019-0524-Y.

- Natural Products as & #945;-Amylase and & #945;-Glucosidase Inhibitors and their Hypoglycaemic Potential in the Treatment of Diabetes: An Update. Mini-Reviews Med. Chem.. 2010;10:315-331.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Potential Dual Inhibitors of Pcsk-9 and Hmg-R From Natural Sources in Cardiovascular Risk Management. EXCLI J.. 2022;21:47-76.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Association of circulatory PCSK-9 with biomarkers of redox imbalance and inflammatory cascades in the prognosis of diabetes and associated complications: a pilot study in the Indian population. Free Radic. Res.. 2023;1–14

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic medication and risk of dementia in patients with type 2 diabetes: a nested case–control study. Eur. J. Endocrinol.. 2019;181:499-507.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Evaluation of Serum Amylase in the Patients of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, with a Possible Correlation with the Pancreatic Functions. J. Clin. DIAGNOSTIC Res. 2013

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105441.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary Data 1

Supplementary Data 1