Translate this page into:

Highly efficient crystalline-amorphous Fe2O3/Fe-OOH oxygen evolution electrocatalysts reconstructed by FeS2 nanoparticles

⁎Corresponding authors at: 1 Hunan Road, Liaocheng City, Shandong Province, China. renxiaozhen@lcu.edu.cn (Xiaozhen Ren), jinchuanyu@lcu.edu.cn (Chuanyu Jin)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

It is crucial to explore the earth-abundant, high-efficient and stable electrocatalysts suitable for accelerating water splitting kinetics of oxygen evolution reaction (OER) in alkaline electrolytes. Herein, FexCo1-xS2 (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1) nanoparticles were fabricated via hydrothermal method and sulfidizing. Remarkably, the FeS2 delivers the most outstanding OER activity among prepared catalysts, with the overpotential of 240 mV for 10 mA/cm2, ultra-low Tafel slope of 45 mV/decades and high stability for 16 h. XRD, SEM, HRTEM, Raman and XPS characteristics before and OER process, TOF and electrochemical results indicate that surface reconstruction, strong combination of Fe-S and uniform dispersion of particles endow FeS2 with excellent catalytic property. The strong combination of Fe-S bond and uniform dispersion of FeS2 facilitates electron transfer. And the reconstructed crystalline-amorphous Fe2O3/FeOOH with rough surface may have a low energy barrier for the elementary reaction of O*→OOH*, which is responsible for boosting the generation of O2. In the practical two-electrode overall water splitting system in 1 M KOH, the FeS2/NF//Pt/C/NF system only needs an ultra-low cell voltage of 1.46 and 1.642 V to generate the current densities of 10 and 50 mA/cm2, respectively.

Keywords

Bimetallic sulfide

Self reconstruction

Crystalline-amorphous

Fe2O3/Fe-OOH

OER

1 Introduction

Hydrogen is widely regarded as a key component in future energy systems just as it is a clean, sustainable and transportable energy carrier (Pomerantseva et al., 2019; Jiao et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2023a; Zhang et al., 2023b). Electrocatalytic water splitting, which can driven by electricity of power grid, solar energy and rechargeable batteries (Rebrov and Gao, 2023; Kang et al., 2021) is extensively considered an environmentally friendly and efficient hydrogen production technology (Suen et al., 2017; Gong et al., 2013; He et al., 2024). Compared with the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), the electrocatalytic efficiency is severely restricted by the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) process because of the slow kinetics and high overpotentials resulting from the complex four-electron transfer (Zhang et al., 2023a; Zhang et al., 2023b; Wang et al., 2020d; Wang et al., 2023d). So, there is a pressing need to explore highly efficient, low-cost and earth-abundant electrocatalysts with fast kinetics and low overpotential for water splitting. Despite noble metal catalysts have proven to be desirable catalysts for OER, the high cost and scarcity of resources seriously limited their wide applications (Ying et al., 2018; Su et al., 2024).

So far, various non-precious materials, including metal oxides (Zhang et al., 2020), phosphate (Li et al., 2022), chalcogenides (Yue et al., 2023), and hydroxides (Peng et al., 2023) have been designed to catalyze the OER, in which Cobalt (Co) or iron (Fe)-based chalcogenides, such as CoFe-Co8FeS8(Wang et al., 2019), Co8FeS8/CoS (Wang et al., 2020a), are excellent candidates towards OER because of their good electronic conductivity and their rich redox properties. Among them, MS2 (M=Fe, Co) deliver high electrocatalytic activity towards OER (Li et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2023c; Xie et al., 2022). Li et al prepared Fe7S8/FeS2/C (Xu et al., 2021) electrocatalysts, in which only 262 mV of overpotentials was required to reach 10 mA/cm2 towards OER. The synthesized FeCoS2/Co4S3/NFG catalysts exhibited enhanced OER catalytic activity, with an overpotential of 276 mV for OER at 10 mA/cm2 (Wang et al., 2023c). Until now, we should also do much research on preparing MS2 (M=Fe, Co) catalysts with improved electrocatalytic performance and reduced energy consumption.

Exploring the real active site during the OER process in alkaline environments is very important for improving the catalytic performance. Recently, a large number of researchers has put forward a view that the prepared electrocatalysts are not real “catalysts”, but “pre-catalysts”, for which their morphology, composition and phase changed dramatically (Chen et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018; Ren et al., 2023). Huang et al (Su et al., 2024) found that the prepared RuO2/Co3O4 had reconstructed to RuO2/CoOOH during the OER process, which showed a low energy barrier for the reaction of O* to *OOH to improve OER performance. Liu et al (Yue et al., 2023) proved that FeS2@FeOOH reconstructed by FeS2 microspheres during the OER process was responsible for the improved OER activity. Also, the high entropy sulfide of FeNiCoCrMnS2 was reconstructed to the metal (oxy)hydroxide during the OER process (Nguyen et al., 2021). Whereas, studying the synergistic effect of Co contents and reconstructing influence on Fe/S catalysts is still rare.

In this study, FexCo1-xS2 (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1) nanoparticles supported on Ni foam were designed, which exhibit excellent OER activity in alkaline environments. The electrochemeical measurements of LSV, CV, EIS, i-t for FexCo1-xS2 catalysts were performed to evaluate the electrocatalytic activity for OER. Remarkably, the FeS2 delivers the most outstanding OER activity among prepared FexCo1-xS2 catalysts. The strong combination of Fe-S bond and uniform dispersion endow FeS2 fast electron transfer. By comparing with XRD, XPS, SEM, TEM and HRTEM, we found that the crystalline-amorphous Fe2O3/Fe-OOH with the rough surface after OER reconstructed by FeS2 supported on Ni foam is the real active site. The reconstructed crystalline-amorphous Fe2O3/Fe-OOH may have a low energy barrier for the elementary reaction of O*→OOH*. Moreover, it only requires the voltage of 1.460 and 1.642 V to generate the current density of 50 and 100 mV/cm2 in a practical two-electrode overall water splitting system. This study may provide a new idea for the research of metal sulfide electrocatalysts toward OER for alkaline water splitting systems.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Samples preparation

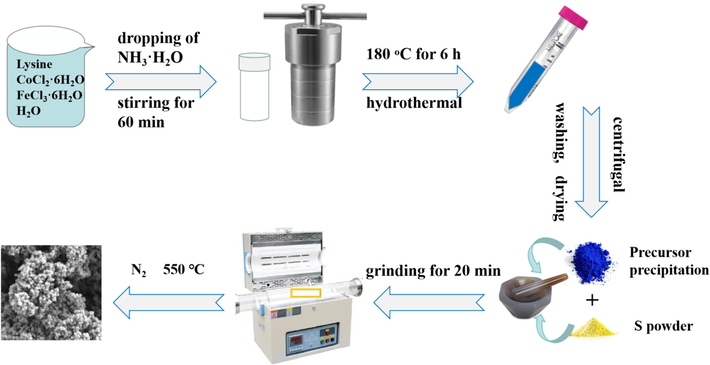

As shown in Scheme 1, for preparing CoS2 nanoparticles: 0.6 g Lysine was added to 75 mL CoCl2 solution (0.05 mol/L) and stirred at 40 °C for 0.5 h in a water bath. 4 mL of ammonia water (32 wt%) was evenly added to the solution within 0.5 h using a peristaltic pump. After stirring the solution for 0.5 h, transfer it into a 100 mL Teflflon-lined autoclave and heat it in an oven at 180 °C for 6 h. After centrifugal, washing and drying for three times, the obtained powder was vacuum-dried overnight at 60 °C. The dried sample was thoroughly mixed with sublimed sulfur at a mass ratio of 1:5, and ground for 10 min. The final CoS2 sample was obtained by calcining the mixed powder at 450 °C in N2 atmosphere for 4 h, with a heating rate of 5 °C/min.

The preparing procedure of the FexCo1-xS2 nanoparticles.

For preparing FexCo1-xS2 nanoparticles: the synthesis process is similar to the above except for changing the amounts of the added salts. For x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1, the amounts of added CoCl2 are 75 mL, 56.25 mL, 37.5 mL, 18.75 mL, and 0 mL while the amounts of added FeCl3 are 0 mL, 18.75 mL, 37.5 mL, 56.25 mL, and 75 mL, and the samples are marked with CoS2, Fe0.25Co0.75S2, Fe0.5Co0.5S2, Fe0.75Co0.25S2, and FeS2, respectively.

2.2 Material characterizations

The surface structure, morphology and interior structure of the synthetic samples were analyzed by emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Zeiss Sigma, Japan) equipped with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) and high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM, FEI Tecnai F30, America). The crystal structures of the samples were investigated using X-ray diffraction (XRD, Smartlab, Rigaku, Japan) with a CuKα radiation source. The elementary composites and surface chemical status of the samples were inspected by performing X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALAB 250xi) and Raman spectroscopy (Raman, Thrmo DXRxi).

2.3 Electrochemical measurements

All the electrochemical measurements were performed by using an electrochemical workstation of Gamry, equipped with a conventional three-electrode cell. In the three-electrode system, Ni foam (1 × 1 cm2) coated with our samples, graphite rod, and Hg/HgO served as working electrode, counter electrode, and reference electrode, respectively. The working electrode was prepared as follow: 10 mg catalysts and 1.0 mg conductive carbon were dispersed onto a mixture of 400 μL isopropanol and 80 μL Nafion solution (5 %, DuPont) with ultrasound for 90 min. After that the prepared homogeneous ink was uniformly dropped onto the pre-treated foam Ni. The conducted potentials in this measuring system were converted to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) potential using the following equation: ERHE=EHg/HgO+0.059 pH+0.098

LSV cures were conducted at a scan rate of 5 mV/s in the range of 0–1 V vs. Hg/HgO with 95 % iR-corrected. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) scanning was carried out in 1 M KOH and was used to inspect the electrochemical double-layer capacitance (Cdl) and the roughness factor (Rf) of the samples according to the equation: Rf = Cdl/60, where 60 represents the assumed 60 uF/cm2 for the double layer capacitance of a smooth surface (Zhang et al., 2013).

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was conducted to collect the Nyquist plots towards OER. To evaluate the OER stability, a chronopotentiometry test was performed for 16 h at a potential of 1.547 vs. RHE.

Also, a two-electrode system was set up for practical overall water splitting. All the two- and three-electrode systems are alkaline solutions with 1.0 M KOH.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Characterization and electrocatalytic performance for OER

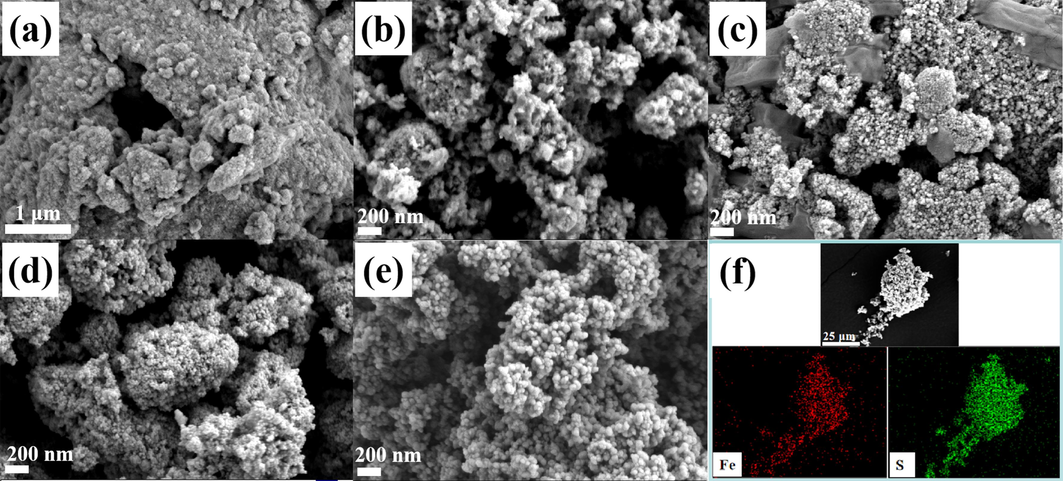

The surface structure and morphologies of CoS2, Fe0.25Co0.75S2, Fe0.5Co0.5S2, Fe0.75Co0.25S2 and FeS2 were investigated by the FESEM, as shown in Fig. 1. All the FexCo1-xS2 (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1) samples are composed of nanoparticles. In Fig. 1a, the CoS2 is made up of very fine nanoparticles. Interestingly, by increasing the x value from 0 to 1 for FexCo1-xS2, the sample became more bigger and uniform, with more smoother surfaces. The uniform particle dispersion is beneficial to electron transport, thereby improving electrochemical performance and reducing resistance for OER (Wang et al., 2022). The elemental mapping of FeS2 in Fig. 1f indicates that the dispersion of S and Fe elements is consistent.

SEM images of (a) CoS2 (b) Fe0.25Co0.75S2 (c) Fe0.5Co0.5S2 (d) Fe0.75Co0.25S2 (e) FeS2 and (f) elemental mapping of FeS2.

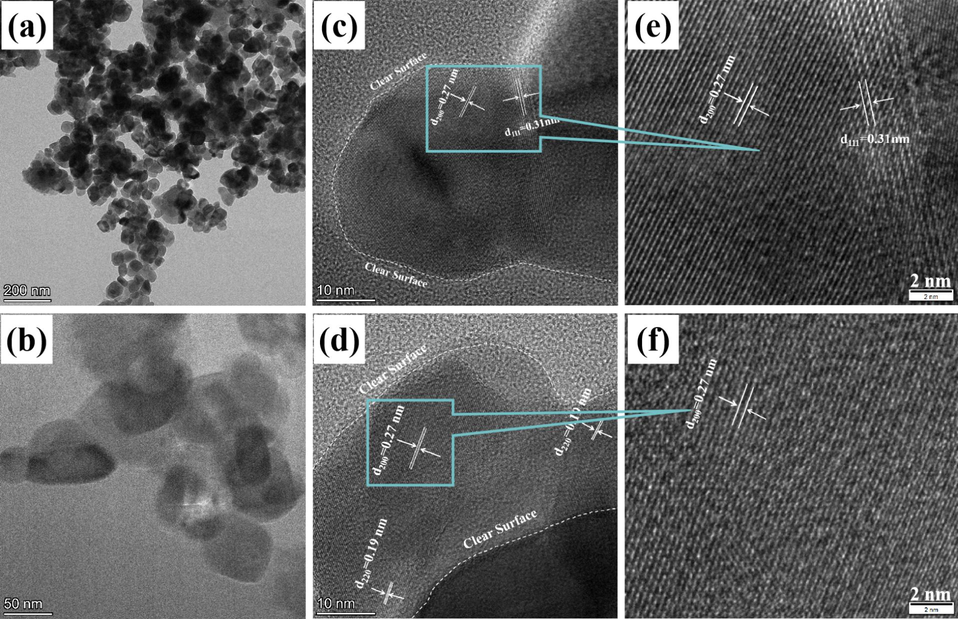

TEM and HRTEM were carried out to inspect the interior structure of the synthetic FeS2 sample, as displayed in Fig. 2. Fig. 2a-2b show that the FeS2 nanoparticles are uniformly dispersed with the size of 50 nm, which is consistent with the results in Fig. 1e-1f. The HRTEM images in Fig. 2c-2f clearly show that the particles have a clear and smooth surface, which will under significant changes during the OER process. Additionally, the determined lattice fringes are 0.27, 0.31, and 0.19 nm, corresponding to the (2 0 0), (1 1 1), and (2 2 0) planes of FeS2 (PDF#71–1680), respectively.

TEM and HRTEM of FeS2 before OER.

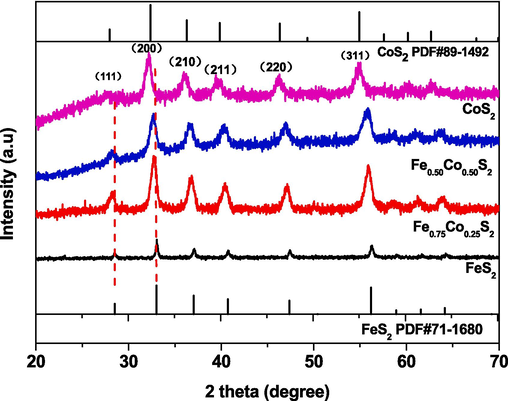

XRD patterns of various samples are shown in Fig. 3. In the patterns of CoS2, the diffraction peaks at 27.878°, 32.300°, 36.237°, 39.835°, 46.329° and 54.938° are attributed to (1 1 1), (2 0 0), (2 1 0), (2 1 1), (2 2 0), and (3 1 1) planes of CoS2 (PDF#89–1492). With increasing the amounts of Fe, all the diffraction peaks shifted towards the large 2θ for the Fe0.5Co0.5S2, Fe0.75Co0.25S2 and FeS2. This phenomenon is attributed to that the radius of Fe is smaller than that of Co. In the patterns FeS2, the (1 1 1), (2 0 0), (2 1 0), (2 1 1), (2 2 0), and (3 1 1) planes match well with the 2θ of 28.516°, 33.045°, 37.079°, 40.768°, 47.431°, 56.278° and belong to FeS2 (PDF#71–1680). The XRD patterns of the samples indicate that we have obtained the pure CoS2, Fe0.5Co0.5S2, Fe0.75Co0.25S2, and FeS2.

XRD patterns of prepared samples.

XPS was performed to inspect the elementary composites and surface chemical status of the samples. The XPS full spectra in Fig. S1a show the obvious Co 2p, Fe 2p and S 2p peaks. The binding energies at 708.0 and 720.8 eV in Fig. S1b are assigned to Fe(II)-S 2p3/2 and Fe(II)-S 2p1/2, respectively, while the peaks at 711.2 and 724 eV consist to Fe(III)-S 2p3/2 and Fe(III)-S 2p1/2 (Guo et al., 2020). Similarly, the XPS spectrum of Co 2p in Fig. S1c all can be decomposed into four peaks, where the binding energies at 778.9 and 798.7 eV belong to Co(II)-S 2p3/2 and Co(II)-S 2p1/2. The other peaks at 782.9 and 803.8 eV are attributed to Co(III)-S 2p3/2 and Co(III)-S 2p1/2, respectively (Fang et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2020). The two peaks at 163.2 and 164.5 eV for the S spectrum in Fig. S1d are assigned to S 2p3/2 and S 2p1/2 from metal sulfide. In addition, the peak at 169.3 eV may be due to the high oxidized sulfur species on the surface of Fe0.25Co0.75S2 samples (Khani and Wipf, 2017). The Raman spectra for CoS2, Co0.25Fe0.75S2 and FeS2 in Fig. S2 show that the peaks at around 386 to 368 cm−1 correspond to Co (Fe)-S bond. Interestingly, the peaks shifted towards lower cm−1, which means the the binding energy became stronger by x increasing for FexCo1-xS2, further effecting their ability for electrons transfer.

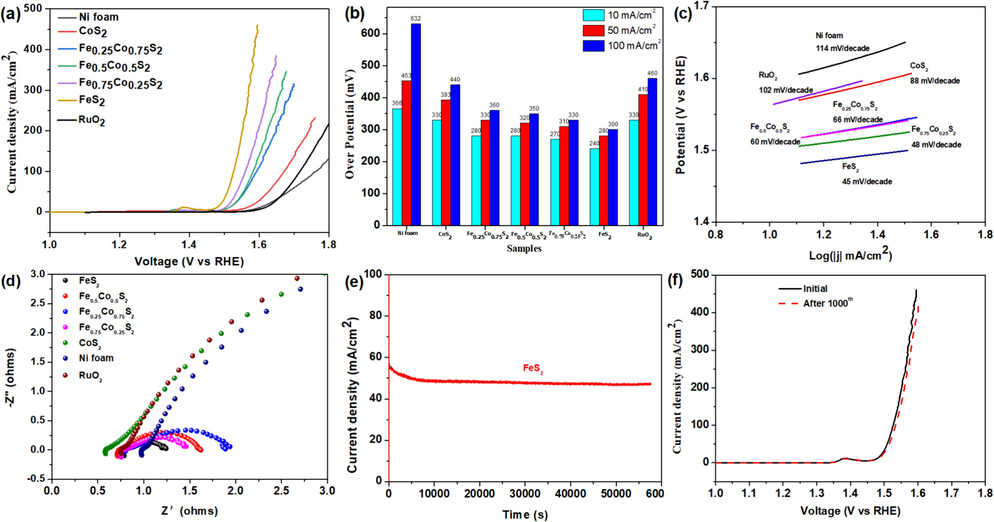

The LSV polarization curve was conducted to probe the OER performance of the various electrocatalysts, as displayed in Fig. 4a, and the corresponding overpotentials at 10, 50, and 100 mA/cm2 were shown in Fig. 4b. The overpotentials of CoS2, Fe0.25Co0.75S2, Fe0.5Co0.5S2, Fe0.75Co0.25S2, and FeS2 at 10, 50, and 100 mA/cm2 are all smaller than that of Ni foam and benchmarking RuO2, indicating the prepared FexCo1-xS2 (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1) samples could act as an excellent catalyst for OER reaction under alkaline condition. Remarkably, the FeS2 delivers the most outstanding OER activity, and it just needs a low overpotentials of 240, 280, and 300 mV to gain the current densities of 10, 50, and 100 mA/cm2, respectively. It is worth noting that the improved OER performance from CoS2 to FeS2 by increasing the x in FexCo1-xS2 may be attributed to the uniform dispersion, the clear and smooth surface and the inherent properties of Fe and Co bimetals, which will be beneficial to electron transport, consistent with the result in Figs. 1-2. On the other hand, the turnover frequency (TOF), acting as the intrinsic activity for the electrocatalysts during the OER process, was calculated with the overpotential of 300 mV and was shown in Supporting Information. The order of the oxygen binding sites for FeS2, Fe0.75Co0.25S2, Fe0.5Co0.5S2, Fe0.25Co0.75S2 and CoS2 are 5.01983 > 4.98769 > 4.95594 > 4.92488 > 4.89366, indicating that FeS2 has the most strongest binding ability among the FexCo1-xS2 samples. So, the TOFs of FeS2, Fe0.75Co0.25S2, Fe0.5Co0.5S2, Fe0.25Co0.75S2, CoS2, and RuO2 are 0.03108, 0.01254, 0.00701, 0.00668, 0.00155, and 0.00154 O2 per s per site, respectively. Astonishingly, the TOF of FeS2 is 20 times more than that of CoS2, confirming the highest intrinsic activity for FeS2.

Electrochemical performances of prepared samples for OER: (a) polarization curve (b) overpotentials at 10, 50, and 100 mA/cm2 (c) Tafel slopes (d) Nyquist plots in the frequency range of 105-0.1 Hz tested in 1 M KOH (e) chronopotentiometry of the FeS2 catalyst performed under a constant potential of 1.547 V vs. RHE for 16 h and (f) polarization curve for FeS2/NF initial and after 1000 cycles after chronopotentiometry for 16 h.

Tafel plots, reflecting the reaction kinetic of OER, were calculated from LSV data, as shown in Fig. 4c. The Tafel slopes of FexCo1-xS2 catalysts are smaller than that of Ni foam and RuO2, indicating that they are easier for overcoming the reaction kinetic process than commercial RuO2. The smallest Tafel slope of 45 mV/decade for FeS2 means it needs overcome the smallest energy barrier during the FexCo1-xS2 samples. Table 1 indicates that the overpotentials at 10 mA/cm2 and the Tafel slopes of prepared Fe0.75Co0.25S2 and FeS2 catalysts are equal to or even lower than that of the most of the reported transition metal/S-based OER electrodes, further implying the competitiveness of prepared electrocatalysts. Similarly, the FeS2 had the smallest Rct value, further demonstrating the most accelerated charge transport kinetics during the OER process, Fig. 4d. Furthermore, the contact angle measurement was conducted to evaluate the penetration of the electrolyte into the FeS2 electrode. The FeS2 electrode exhibits a superhydrophilic behavior, with a contact angle approaching 0° (Fig. S5).

Catalysts

η/mV

10 mA cm−2

Tafel slope

/mV dec-1

References

FeS2

189.5

71

Wang et al., 2021

CoFe-Co8FeS8

290

38

Wang et al., 2019

Co8FeS8/CoS

278

49

Wang et al., 2020a

Fe7S8/FeS2/C

262

48

Xu et al., 2021

FeCoS2/Co4S8/NFG

276

148

Wang et al., 2023c

Ni-Ni3S2@carbon NP

284.7

56

Lin et al., 2019

Co0.3Ni0.3Fe0.2S NPs/C

266

47

Wang et al., 2023a

Ni3S2/MoS2

260

59

Wang et al., 2020b

CoNi2S4@CoS2

259

45

Huang et al., 2019

Co9S8 Hollow Spheres

285

58

Feng et al., 2017

CoS2 HNSs

290

57

Ma et al., 2018

CoMoOS NBs

281

75.4

Xu et al., 2020

Fe1-xS/C

130

55

Wang et al., 2023b

CoS2-FeS2

210

46

Wang et al., 2020c

Fe0.75Co0.25S2

270

48

This work

FeS2

240

45

This work

For practical application, it is crucial to estimate the stability of the electrocatalysts during the OER process. We carried out the chronopotentiometry at 1.547 V vs. RHE to identify the stability of the FeS2 catalyst, Fig. 4e. Notably, the current density remained almost unchanged with an approach of 50 mA/cm2 for 16 h. In addition, As shown in Fig. 4e, the electrocatalytic activity for FeS2 after 1000 CV cycles changed little compared with that of initial LSV.

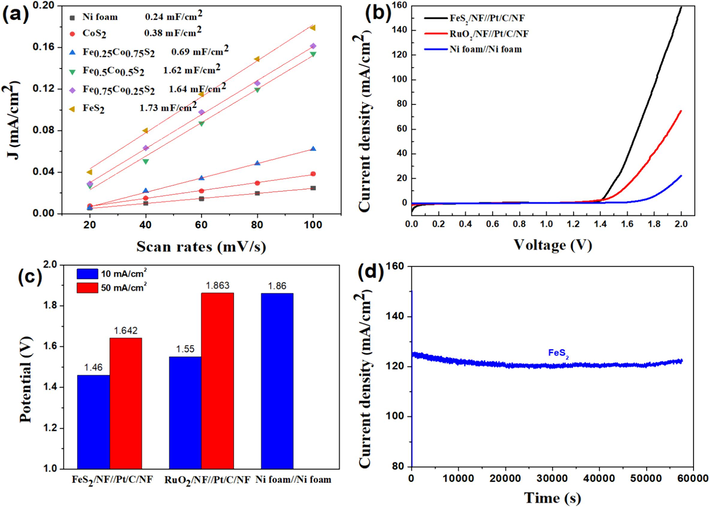

The Cdl and Rf, which can be determined by cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements in the non-Faradic regions, are typically indexed to estimate electrochemical surface area (ECSA). According to the CV measurement for Ni foam, FexCo1-xS2 in Fig. S3 at scan rates of 20, 40, 60, 80, 100 mv/s in 1 M KOH, the Cdl for FeS2 is 1.93 mF/cm2, which is much higher than those of 1.64, 1.62, 0.69, 0.38 and 0.24 mF/cm2 for Fe0.75Co0.25S2, Fe0.5Co0.5S2, Fe0.25Co0.75S2, CoS2 and Ni foam, respectively, indicating that FeS2 possesses the highest ECSA among those various samples and number of active sites, further accelerating the OER process. Moreover, Rf reflects the non-uniformity of the working electrode and a larger Rf means more active surface area for driving the OER process. According to Rf = Cdl/60, the values of Rf for FeS2 is 32.1, higher than that of Fe0.75Co0.25S2 (27.3), Fe0.5Co0.5S2 (27), Fe0.25Co0.75S2 (11.5), CoS2 (6.3) and Ni foam (4) in terms of double-layer capacitance, respectively, implying the most active area for FeS2.

Considering the practical application of two-electrode electrolysis, the overall water splitting for FeS2/NF and Pt/C/NF (FeS2/NF//Pt/C/NF) served as an anode and a cathode was performed in 1 M KOH. Meanwhile, we assembled the RuO2/NF//Pt/C/NF and Ni foam//Ni foam two-electrode systems, displayed in Fig. 5b. Apparently, the FeS2/NF//Pt/C/NF system just required only 1.460 and 1.642 V to generate the current densities of 10 and 50 mA/cm2, respectively, which was much lower than those of RuO2/NF//Pt/C/NF (1.55 and 1.863 V) and Ni foam//Ni foam (1.86 V at 10 mA/cm2) systems, Fig. 5c. Interestingly, the FeS2/NF//Pt/C/NF system remained high stability at 123 mA/cm2 for 16 h, Fig. 5d. All the above results indicates that FeS2/NF//Pt/C/NF two-electrode system possess high catalytic performance and stability toward the practical overall water splitting.

(a) the plots of the current density v.s. scan rates of various samples, (b) the LSV cures, (c) overpotentials at 10 and 50 mA/cm2 for two electrode water splitting of bare Ni foam//Ni foam, RuO2/NF//Pt/C/NF, and FeS2NF//Pt/C/NF systems in 1 M KOH. (d) i-t cures of FeS2 for water splitting at 1.551 V.

3.2 Characterization after OER

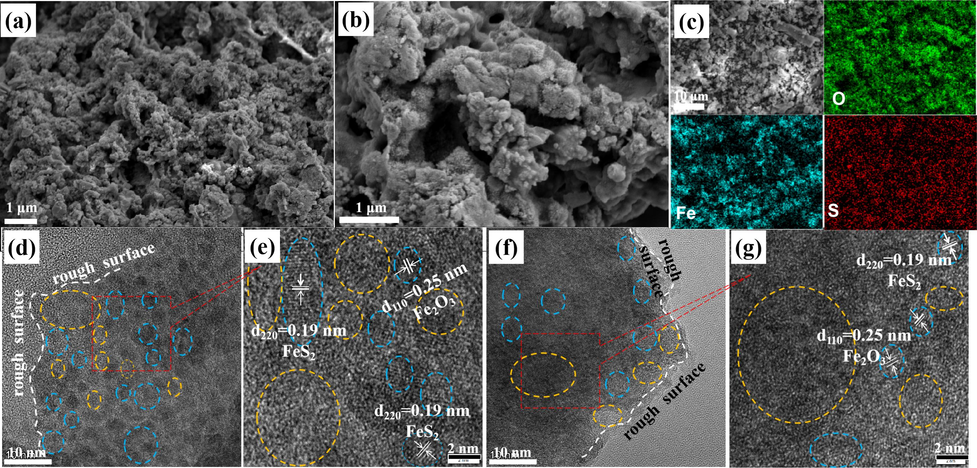

It is very crucial to get insight into the crystal phase, structure and morphology changes after OER for surveying the catalytic capability, stability and active site for OER catalysts. So, the SEM, TEM, HRTEM, XRD, Raman and XPS were performed to characterize the FeS2 catalysts after OER. As shown in Fig. 6a and 6b, the FeS2 samples after OER still kept the morphology of nanoparticles, further implying its stability. Interestingly, the nanoparticles after OER became much smaller, with a more uneven surface. The TEM and HRTEM in Fig. 6d-6 g demonstrated the roughened surface caused by the OER process is very different from the smooth surface in Fig. 2. We also further inspect the diffraction of the catalysts after OER. After magnified in Fig. 6e and 6 g, the single FeS2 catalyst before OER had largely evolved into crystalline Fe2O3 after OER, which could be verified by the (2 2 0) planes of FeS2 and (1 1 0) planed of Fe2O3, matched with the lattice fringes of 0.19 and 0.25 nm, respectively, accompanying with some amorphous phase of FeOOH marked with a yellow circle. In addition, the mapping in Fig. 6c also showed the dispersed Fe, S and O elements.

(a-b) SEM, (c) elemental mapping (d, f) TEM, and (e, g) HRTEM of FeS2 after OER.

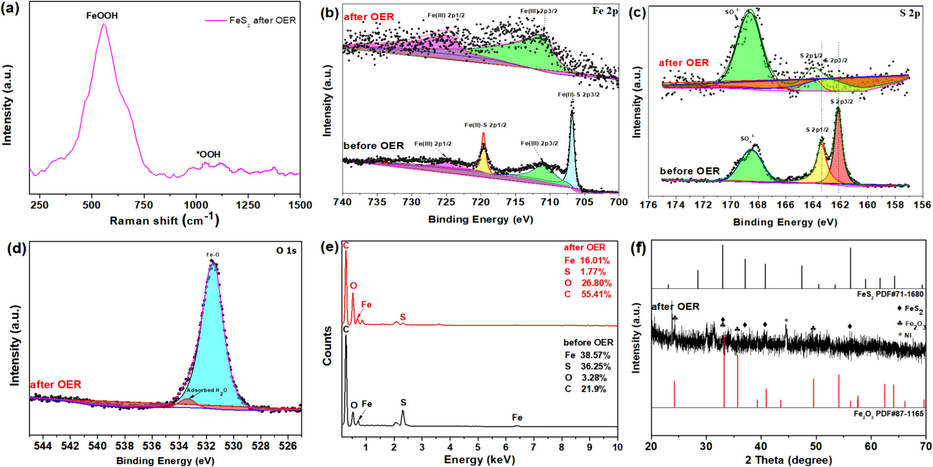

In the Raman spectrum of FeS2 after OER process in Fig. 7a, the peak at 555 cm−1 corresponds to the vibration of FeOOH, implying the formation of amorphous CoOOH, while another broad peak around 1050 cm-1 is the signal peak for *OOH (Moysiadou et al., 2020; Koza et al., 2013). The main peaks of Fe, S and O had changed obviously, as shown in Fig. S4. Comparing with Fe 2p before and after OER, it is obvious that the peaks at 708.0 and 720.8 eV belonging to Fe(II) had almost vanished in Fig. 7b (Guo et al., 2020). Meanwhile, the peaks at 711.2 and 724 eV in Fig. 7c belonging to Fe(III) also shifted to 711.6 and 724.4 eV, which could attribute to Fe-O and Fe-OOH bonds (Chen et al., 2022), further proofing the formation of Fe2O3 and the amorphous phase of Fe-OOH. It happened that the peak intensities at 162.2 and 163.3 eV belonging to S 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 also became weaker and even disappeared for FeS2 after OER, while the peak strength at 168.4 eV attributed to SO42- became stronger after OER (Wang et al., 2017), resulting from the oxidation for FeS2, as displayed in Fig. 7c. The O 2p spectrum after OER can be decomposed into Fe-O or Fe-OOH at 531.7 eV and adsorbed H2O at 533.5 eV, respectively (Abu-Zied and Ali, 2018; Yu et al., 2017), in Fig. 7d.

(a) Raman spectrum of FeS2 after OER process, XPS spectra of (b) Fe 2p (c) S 2p (d) O 1 s (e) the percentages of Fe, S, O, and C, (f) XRD patterns with FeS2 after OER.

The EDX elemental analysis before and after OER was displayed in Fig. 7e. The relative content of S had reduced from 36.25 % to 1.77 % after OER. In contrast, the relative content of O increased from 3.28 % to 26.80 % after OER. In addition, the XRD patterns in Fig. 7f show that the obvious characteristic diffraction peaks for Fe2O3 and FeS2 appeared, indicating that the FeS2 have largely evolved into crystalline Fe2O3, further suggesting the reconstruction of the catalyst. The peak at 44.67° can be attributed to the Ni, because the catalysts were dropped onto the foam Ni. All the above discussion indicates that the FeS2 catalysts with smooth surface and uniform dispersion have largely reconstructed to crystalline-amorphous Fe2O3/Fe-OOH.

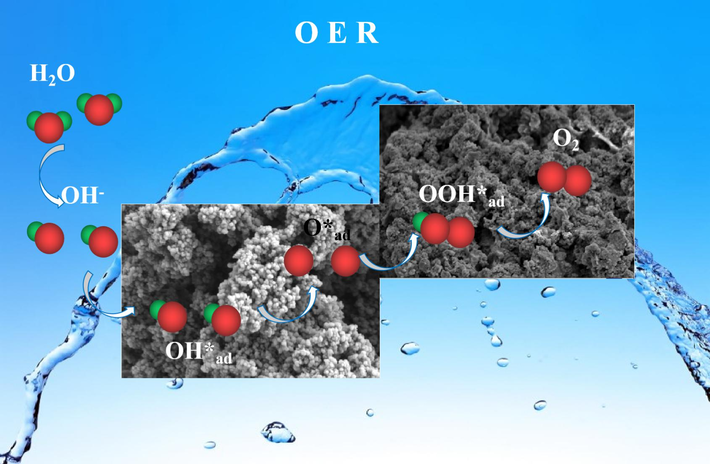

Based on the above discussion, the synergistic effect of Co contents and reconstructing influence on Fe/S catalysts is put forward and is described in Scheme 2. First, the strong combination of Fe-S bond and the uniform dispersion of FeS2 endow it improved charge transfer capability. During OER process, the FeS2 with smooth surface has largely reconstructed to crystalline-amorphous Fe2O3/Fe-OOH with rough surface, which has a energy barrier for elementary reaction of O*→OOH*, further boosting the generation of O2 (Su et al., 2024). As a result, the FeS2 with fast electron transfer and low energy barrier for O*→OOH* exhibits excellent electrocatalytic water splitting capability towards OER.

OER process in FeS2 electrocatalysts.

4 Conclusion

In this study, highly-efficient FexCo1-xS2 (x = 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75 and 1) nanoparticles toward OER in alkaline electrolyte were designed. Remarkably, the FeS2 delivered the most outstanding OER activity among prepared catalysts, with the overpotential of 240 mV for 10 mA/cm2, ultra-low Tafel slope of 45 mV/decades and high stability for 16 h. XRD, SEM, HRTEM, Raman and XPS characteristics before and OER process, TOF and electrochemical results indicate that surface reconstruction, strong combination of F-S bonds and uniform dispersion of particles endow FeS2 with excellent catalytic property. The FeS2 with fast electron transfer and low energy barrier for O*→OOH* exhibits excellent electrocatalytic water splitting capability towards OER This study may provide a new idea for the research of metal sulfide electrocatalysts toward OER for alkaline water splitting systems.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xiaozhen Ren: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Investigation, Funding acquisition. Shanshan Li: Investigation, Formal analysis. Ziyou Li: Methodology, Investigation. Zhenyang Zhang: Methodology. Hanxu Hou: Methodology, Investigation. Yanan Zhou: Methodology, Investigation. Chuanyu Jin: Methodology, Investigation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51904148) and the Undergraduate Innovation Training Program Fund of Liaocheng University (Grant No. cxcy2022247).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Fabrication, characterization and catalytic activity measurements of nano-crystalline Ag-Cr-O catalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2018;457:1126-1135.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A universal strategy to design superior water-splitting electrocatalysts based on fast in situ reconstruction of amorphous nanofilm precursors. Adv. Mater.. 2018;30:1804333.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Trimetallic oxyhydroxides as active sites for large-currentdensity alkaline oxygen evolution and overall water splitting. J. Mater. Sci. Technol.. 2022;110:128-135.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metallic transition metal selenide holey nanosheets for efficient oxygen evolution electrocatalysis. ACS Nano. 2017;11(9):9550-9557.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Facile synthesis of Co9S8 hollow spheres as a high-performance electrocatalyst for the oxygen evolution reaction. ACS Sustain Chem. Eng.. 2017;6:1863-1871.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An Advanced Ni−Fe Layered Double Hydroxide Electrocatalyst for Water Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2013;135(23):8452-8455.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fe–doped Ni2P nanosheets with porous structure for electroreduction of nitrogen to ammonia under ambient conditions. Appl. Catal. b: Environ.. 2020;263:118296

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coupling NiSe2 Nanoparticles with N-Doped Porous Carbon Enables Efficient and Durable Electrocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction at pH Values Ranging from 0 to 14. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.. 2024;7(1):1138-1145.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Welldesigned cobalt-nickel sulfide microspheres with unique peapod-like structure for overall water splitting. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2019;556:401-410.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Design of electrocatalysts for oxygen- and hydrogen-involving energy conversion reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev.. 2015;44:2060-2086.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lithium metal anode with lithium borate layer for enhanced cycling stability of lithium metal batteries. J. Power Sources. 2021;485:229286

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iron oxide nanosheets and pulse-electrodeposited Ni-Co-S nanoflake arrays for high-performance charge storage. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2017;9(8):6967-6978.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Deposition of β-Co(OH)2 Films by Electrochemical Reduction of Tris(ethylenediamine)cobalt(III) in Alkaline Solution. Chem. Mater.. 2013;25(9):1922-1926.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coupling overall water splitting and biomass oxidation via Fe-doped Ni2P@C nanosheets at large current density. Appl. Catal. b: Environ.. 2022;307:121170

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrite FeS2/C nanoparticles as an efficient bi-functional catalyst for overall water splitting. Dalton Trans.. 2018;47:14917-14923.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 2D free-standing nitrogen-doped Ni-Ni3S2 @carbon nanoplates derived from metal-organic frameworks for enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Small. 2019;15:1900348.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phase and composition controlled synthesis of cobalt sulfide hollow nanospheres for electrocatalytic water splitting. Nanoscale. 2018;10:4816-4824.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanism of oxygen evolution catalyzed by cobalt oxyhydroxide: cobalt superoxide species as a key intermediate and dioxygen release as a rate-determining step. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2020;142:11901-11914.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Self-reconstruction of sulfate-containing high entropy sulfide for exceptionally high-performance oxygen evolution reaction clectrocatalyst. Adv. Funct. Mater.. 2021;31:2106229.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical reconstruction of NiFe/NiFeOOH superparamagnetic core/catalytic shell heterostructure for magnetic heating enhancement of oxygen evolution reaction. Small. 2023;19(3):2205665.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Energy storage: The future enabled by nanomaterials. Science. 2019;366:eaan8285.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular Catalysts for OER/ORR in Zn–Air Batteries. Catalysts.. 2023;13:1289.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic effect of surface reconstruction and rGO for FeS2/rGO electrocatalysis with efficient oxygen evolution reaction for water splitting. Arab. J. Chem.. 2023;16:105069

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Surface reconstruction of RuO2/Co3O4 amorphous-crystalline heterointerface for efficient overall water splitting. J. Colloid Interf. Sci.. 2024;658:43-51.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Electrocatalysis for the oxygen evolution reaction: recent development and future perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev.. 2017;46:337-365.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Intercalated Co(OH)2-derived flower-like hybrids composed of cobalt sulfide nanoparticles partially embedded in nitrogen doped carbon nanosheets with superior lithium storage. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017;5:3628-3637.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ternary sulfide nanoparticles anchored in carbon bubble structure for oxygen evolution reaction. Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 2023;968:172314

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heterogeneous CoFe-Co8FeS8 nanoparticles embedded in CNT networks as highly efficient and stable electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction. J. Power Sources. 2019;433:126688

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A microwave-assisted bubble bursting strategy to grow Co8FeS8/CoS heterostructure on rearranged carbon nanotubes as efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. J. Power Sources. 2020;449:227561

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- FeCoS2/Co4S3/N-doped graphene composite as efficient electrocatalysts for overall water splitting. Electrochim. Acta. 2023;441:141790

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Surface self-reconstructed amorphous/crystalline hybrid iron disulfifide for high-effiffifficiency water oxidation electrocatalysis. Dalton Trans.. 2021;50:6333-6342.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Redox bifunctional activities with optical gain of Ni3S2 nanosheets edged with MoS2 for overall water splitting. Appl. Catal. B Environ.. 2020;268:118435

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Visible-light-induced unbalanced charge on NiCoP/TiO2 sensitized system for rapid H2 generation from hydrolysis of ammonia borane. Appl. Catal. b: Environ.. 2020;260:118183

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanoframes of Co3O4-Mo2N Heterointerfaces Enable High-Performance Bifunctionality toward Both Electrocatalytic HER and OER. Adv. Funct. Mater.. 2022;32:2107382.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Completely reconfigured Fe1-xS/C ultra-thin nanocomposite lamellar structure for highly efficient oxygen evolution. Fuel.. 2023;341:127686

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced oxygen and hydrogen evolution performance by carbon-coated CoS2-FeS2 nanosheets. Dalton Trans.. 2020;49:13352-13358.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Research progress on high entropy alloys and high entropy derivatives as OER catalysts. J Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2023;11(1):109080

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Surface reconstruction engineering of cobalt phosphides by Ru inducement to form hollow Ru-RuPx-CoxP pre-electrocatalysts with accelerated oxygen evolution reaction. Nano Energy. 2018;53:270-276.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anchoring stable FeS2 nanoparticles on MXene nanosheets via interface engineering for efficient water splitting. Inorg. Chem. Front.. 2022;9:662-669.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fe7S8/FeS2/C as an effificient catalyst for electrocatalytic water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46:39216-39225.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Three-dimensional open CoMoOx/CoMoSx/CoSx nanobox electrocatalysts for efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Appl. Catal. B Environ.. 2020;265:118605

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Double-layered yolk-shell microspheres with NiCo2S4-Ni9S8-C heterointerfaces as advanced battery-type electrode for hybrid supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J.. 2020;396:125316

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal-organic frameworks derived platinum-cobalt bimetallic nanoparticles in nitrogen-doped hollow porous carbon capsules as a highly active and durable catalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. Appl. Catal. b: Environ.. 2018;225:496-503.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ternary nickel-iron sulfide microflowers as a robust electrocatalyst for bifunctional water splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2017;5:15838-15844.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Highly efficient FeS2@FeOOH core-shell water oxidation electrocatalyst formed by surface reconstruction of FeS2 microspheres supported on Ni foam. Appl. Catal. b: Environ.. 2023;339:123171

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hierarchical wreath-like Au–Co(OH)2 microclusters for water oxidation at neutral pH. Nanoscale. 2013;5:6826-6833.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Cao X, Guo C, 2023. A. Hassan, Y. Zhang, J. Wang. Interface and morphology engineering of Ru-FeCoP hollow nanocages as alkaline electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. J Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 111373. DOi: 10.1016/j.jece.2023.111373.

- Metal Atom-Doped Co3O4 Hierarchical Nanoplates for Electrocatalytic Oxygen Evolution. Adv. Mater.. 2020;32(31):2002235.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Interface engineering on amorphous/crystalline hydroxides/sulfides heterostructure nanoarrays for enhanced solar water splitting. ACS Nano. 2023;17(1):636-647.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2024.105907.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary Data 1

Supplementary Data 1