Translate this page into:

Synergistic response of PEG coated manganese dioxide nanoparticles conjugated with doxorubicin for breast cancer treatment and MRI application

⁎Corresponding authors. asif3220286@gmail.com (Muhammad Asif), Fakharphy@gmail.com (M. Fakhar-e-Alam),

⁎⁎Corresponding author. l.li2@uq.edu.au (Li Li)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Abstract

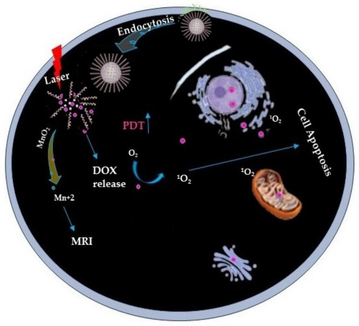

In this research work, we designed a smart biodegradable PEG-coated MnO2 nanoparticles conjugated with doxorubicin (PMnO2-Dox NPs) for dual chemo-photodynamic therapy and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) application. This highly sensitive pH-responsive PMnO2-Dox NPs causes effective drug release under acidic pH environment. PMnO2-Dox NPs not only improves the efficacy of chemo-photodynamic therapy due to synergistic response as well as improved MRI imaging via boosting T1 MRI contrast. Manifold characterization techniques have been employed for materials investigation. Crystallography of PMnO2-Dox NPs were performed by using XRD analysis, which confirmed tetragonal crystal structure with an approximate crystallite size of 20–30 nm. Surface morphology was confirmed via SEM analysis, results indicated the spherical and asymmetric agglomerated nanocluster of PMnO2-Dox NPs. In in vitro bioassay, the anticancer activity of PMnO2-Dox NPs were tested against breast cancer (MCF-7) cell line using MTT test. Moreover, it can also inhibit the growth of primary and secondary cancers without light exposure. Results suggested that PMnO2-Dox NPs not only convenient for cancer treatment via combined chemo-photodynamic therapy but also address the way towards a comprehensive strategy for MRI application via bright contrast agent T1 after overcoming the problem of multidrug resistance (MDR) and synergistic response of therapeutic analysis.

Keywords

PEGylation

MnO2 nanoparticles

Conjugation

Doxorubicin

Chemo-photodynamic therapy and MRI

1 Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) report in 2020, cancer is the second leading cause of death in the world and accounts for 10 million deaths (Sung et al., 2020; Asif et al., 2024). Among them, breast cancer is one of the most prevalent cancers with high mortality (Mohebian et al., 2021; Mettlin, 1999). Breast cancer has a high incidence and mortality rate in Pakistan (one in nine) (Khan et al., 2021). Conventional cancer treatments have been effective in defeating tumors, including surgery, photodynamic therapy (PDT), chemodynamic therapy (CDT), and radiotherapy (RT) (Wu et al., 2019; Bi et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2023). PDT has a non-invasive and remarkable anticancer efficiency (i.e., due to its abundant production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) to kill cancer cells) and minimal side effects as compared to CDT (Zhang et al., 2020). Most importantly, the significant effect of photodynamic therapy could be enhanced by suitable laser irradiation to versatile MnO2 NPs (Zhang et al., 2020).

Among the various types of nanoparticles, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) have received high scientific attention due to their potential applications in various fields, particularly in the medical field (Tatarchuk et al., 2017; Gao et al., 2019; Fakhar-e-Alam et al. 2024; Zhao et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2014). In the past two decades, MNPs, such as MnO2 NPs have catch up much attention in biomedical applications including PDT, chemo-photodynamic therapy, hyperthermia therapy, radiotherapy, MRI guided synergetic photothermal therapy, drug delivery, bio-imaging and MRI contrast enhancement due to their unique physio-chemical and biological properties (Li et al., 2024; Deng et al., 2011; Li et al., 2018; Luong et al., 2011; Daou et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2004).

Recent literature reports that MnO2 NPs have been extensively studied as O2 deliver candidate because of their exceptional physio-chemical and biological properties, and highly sensitive to Hydrogen ion (H+) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which are rich in tumors (Fatima, 2024; Maity et al., 2009; Faraji et al., 2010; Soon et al., 2007). Importantly, MnO2 nanostructure can react with intracellular Glutathione (GSH) to decrease its level and increase the efficiency of PDT (Fan et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2017). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that malignant tumor cells differ from healthy cells in several specific characteristics. Conversely, tumor cells would produce excessive amounts of H2O2 (Kuang et al., 2011; Spyratou et al. 2012). In current, extensive literature it has been reported that mesoporous or solid MnO2 NPs (Yang et al., 2017), core/shell MnO2 NPs (Liang et al., 2018), and MnO2 NSs (Zhao et al., 2014; Fan et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018) readily reduce in a slightly acidic behavior.

Polymer-based nanoparticles have a longer circulation time and are more stable than metal-based NPs. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is a hydrophilic polymer that is highly biodegradable, biocompatible, stable and attractive for drug delivery due to resolving the MDR problem (Kutikov and Song, 2015; Li et al., 2023). Cheng et al. (2020) reported that Dox@H-MnO2-PEG and Dox@H-MnO2-FA show significant results against MRI (T1 contrast agent) in acidic environment (Cheng et al., 2020). Hu et al. (2013) reported that PVP-coated manganese oxide nanoparticles (MnO@PVP NPs) can improve the T1 signal, used to visualize tumor images and also suggested that MnO@PVP NPs are promising candidate for enhancing T1 MRI bright contrast agent in in vitro and in vivo (Hu et al., 2013).

In the current research work, versatile PMnO2-Dox NPs were successfully synthesized and confirmed by essential characterization techniques. To overcome the MDR barrier and inhibit cancer growth by using chemo-photodynamic therapy. The PMnO2-Dox NPs has been developed and applied to MCF-7 cell line. This smart study based on PMnO2-Dox NPs opens new horizons for emerging cancer responsive theranostic for cancer treatment.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Chemicals

Potassium permanganate (KMnO4), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), ethanol(C2H6O), methanol, polyethylene glycol (PEG), 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES), and polyallylamine hydrochloride (PAH) were purchased from Merck (US). Doxorubicin hydrochloride (C27H29NO11.HCl) was gifted from Pinum Pharmacy, Pinum Cancer Hospital Faisalabad, Punjab Medical College University, Punjab Pakistan.

2.2 Synthesis process

2.2.1 Synthesis of MnO2 NPs

MnO2 NPs were synthesized using co-precipitation approach with modified protocol (Du et al., 2023). Briefly, 0.2 M NaOH in 20 mL was added dropwise to 0.5 M KMnO4 in 50 mL at vigorous stirring and then stirred for 24 h until the color turned from purple to dark brown. Finally, the prepared solution was centrifuge at 6000 rpm for 10 min and washed three times with deionized water. Finally, MnO2 NPs were dried in the oven.

2.2.2 Synthesis of MnO2-Dox

MnO2-Dox NPs were synthesized using a slightly modified protocol as follows (Du et al., 2023): 2 mL of APTES was added to 0.1 M MnO2 NPs in 10 mL of methanol and continuously stirred at 60 °C for 5 h. Then, the synthesized sample were washed triplet with deionized water and dried. The aminated MnO2 NPs has been collected. Different concentration (0–5 µg/mL) of Dox were dissolved in 3 mL methanol and 3 mg of aminated MnO2 NPs were added to Dox methanol solution under stirring for 24 h, for each sample of Dox (Lei et al., 2021). To neutralize the HCl, triethylamine was added. Then, the prepared sample were moved to a dialysis bag for dialysis to remove unreacted Dox. The MnO2-Dox NPs sample were collected after dried at 60 °C.

2.2.3 Synthesis of PMnO2-Dox NPs

The PMnO2-Dox were synthesized using filtration approach. The 0.05 g of PEG (Molecular weight (Mw) 5,000 gmol−1) and MnO2-Dox were dissolved in 5 mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and the mixture solution were squeezed 5 min and then filtered through a polycarbonate membrane filter to remove any free PEG. Finally, PEG were coated with MnO2-Dox NPs to obtain PMnO2-Dox.

2.3 Characterization of nanomaterials

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were measured on a “NOVA NANO SEM 430”. The UV–Visible spectrophotometer was used to measure the optical density on the "BK-UV1800PC Double beam Bio-base (China)". The Dox loading efficiency were determined using UV–vis at 385 and ∼490 nm. Fourier transformation infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR Spectrum 2, Perkin Elmer) was utilized to identify the functional groups at the various modes. Then, the vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) analysis were performed on "EDX model, 7200 Flagship" to determine the magnetic properties of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs at room temperature. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) were performed on a "D8 advance Bruker (Germany)" to analyze the atomic structure of a crystal using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154). X-ray photoelectron (XPS) were employed to further verify the formation of PMnO2-Dox NPs using K-alpha X-ray photoelectron spectrophotometer "Thermo Fisher Scientific, UK". Dynamic light scattering (DLS) were performed to determine the size distribution profile of small particles in suspension using Zetasizer Nano ZS "Malvern Instruments Ltd". Finally, flow cytometry were employed on "Agilent Biosciences Inc., Santa Clara, CA" to detect cell apoptosis.

The crystallite size were calculated based on XRD using the Scherer's equation.

2.4 Cell culture

Human breast cancer (MCF-7) cell lines were gifted from the National Institute of Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering (NIBGE) Faisalabad, Pakistan. MCF-7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1 % antibiotics (streptomycin, 100 µ/mL + penicillin) at 37 °C with 5 % carbon dioxide (CO2) in a humidified incubator and for more information see our published articles (Tahir et al., 2024).

2.5 Cell viability assay

The MTT assay were used to calculate the anticancer activity of the samples on MCF-7 cell line. The MCF-7 cells were seeded in 96-microwell plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well and incubated overnight at 37 °C. Then, fresh mediums containing Dox in the concentration range (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 μg/mL), MnO2 NPs, Dox, and PMnO2-Dox NPs in the concentration range (6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100 and 200 μg/mL) were added to the cells and incubated for 48 h. After 48 h, the cells were washed with PBS three times and fresh mediums were added and incubated at 37 °C with 20 μL of MTT for 4 h, following with 100 μL of DMSO addition. The cell intensities were determined at wavelength of 385 and ∼490 nm via Bio Base microplate reader. This study was performed three times. The % cell viability was calculated using the following equation.

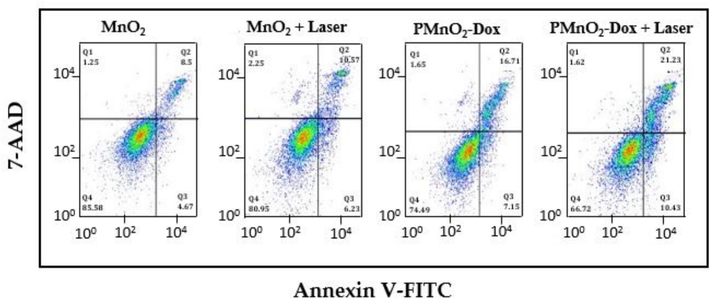

2.6 Quantitative analysis of apoptosis via flow cytometry

MCF-7 cells were seeded in 96-microwell plates overnight at 37 °C. After that, MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs (containing 5 μg/mL Dox) were added to the cells and incubated for 48 h. After 48 h, the cells were washed with PBS, resuspended in 100 μL of binding buffer, and then stained with 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC and 7-AAD. The cells were incubated in the dark for 20 min. Finally, flow cytometry were employed to detect cell apoptosis.

2.7 Dox loading efficiency and capacity

Dox was conjugated into the PMnO2 NPs. For Dox loading, PMnO2 NPs was mixed with different concentrations (0–5 µg/mL) of Dox in the dark overnight. The loading efficiency of DOX increased proportionally with the amount of added doxorubicin, attaining a maximum level of 86.17 %. Finally, the PMnO2-Dox NPs were attained by centrifugation (8000 rpm, 10 min), rapidly washed with water to remove the adsorbed Dox, and then dried at room temperature. The achieved PMnO2-Dox NPs were used for chemo-photodynamic therapy.

The following equations were used to calculate the Dox efficiency and capacity.

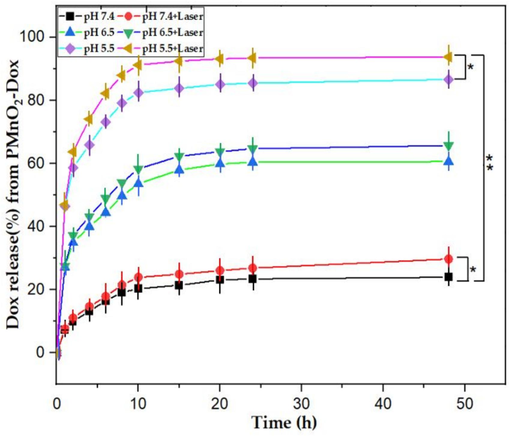

2.8 Dox release from PMnO2-Dox NPs

The kinetics of drug release from PMnO2-Dox NPs surfaces were studied at pH 5.5, 6.5 and 7.4. for drug release experiment, the different concentration of (0–200 µm) PMnO2-Dox NPs were dispersed into 5 mL PBS, then they were stunned and irradiated with or without laser light (dose 80 j/cm2) for 5 min in a certain period. The UV–visible spectrometer was used to measure the drug released.

2.9 Photodynamic performance

MCF-7 cell line were used to study the effects of PDT while applying parameters, 0–200 µg/mL, and light dose 80 j/cm2 as optimum light towards MCF-7 cell model. For the in vitro cell apoptotic induction experiment, A semiconductor diode laser (visible blue light – 440/480 nm range, Starlight pro, Mectron Italy) with a wavelength of 480 nm was used to irradiate/expose the MCF-7 cells through the luminescent bottom of the plate. A fibre-optic (BIOSPEC, TF-D, Russia) was used to transmit the laser beam into the cells in a 6 mm diameter well (area of 0.294 cm). Drug light interval (DLI) for PMnO2-Dox NPs uptake cells was half an hour. The morphology of the treated cells was observed by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). All PDT protocols were adopted as per the recommendation of the animal ethics committee of Government College University Faisalabad (GCUF).

2.10 Chemodynamic therapy performance

MCF-7 cell line was cultured in 96 microwell plates and then incubated for 24 h under recommended protocol of animal/cell ethics committee GC University Faisalabad. After obtaining 70 % cell confluency (about 24 h culturing incubation time). MCF-7 cells were exposed with working solution of various doses of Dox, MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs. After 24 h, treated with concentrations (0–5 µg/mL) Dox, (0–200 µg/mL) concentrations of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs. Drug interval (DI) for Dox, MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs uptake cells was incubated for 48 h. The morphology of the treated cell was observed by electron microscopy (EM).

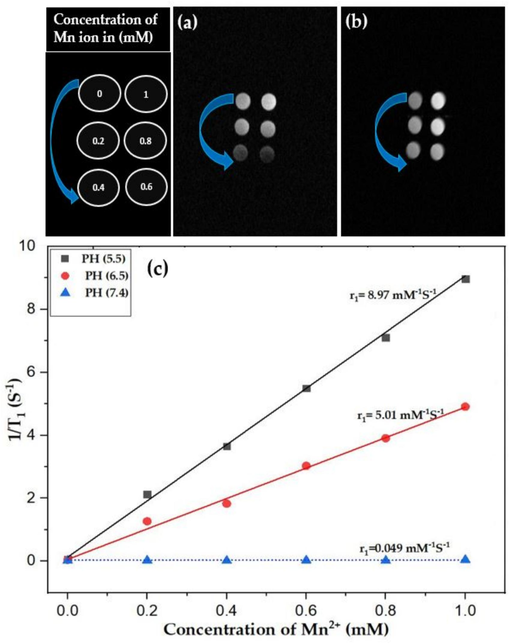

2.11 MRI bright (T1) contrast agent

The magnetic properties of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs were characterized by MRI analysis on “MRI SIGNA” Scanner using 7 Tesla with gradients (450/675 mT/m; relaxation time 3400–4500 T/m/s; echo time 140 µs) were used as standard. MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs in the range of 0–1.0 mM were measured. The relaxations enhancement with varying TR (repetition time), and multi-slice multi-echo (MSME) were applied to estimate T1 and T2 respectively. Same procedure was adopted by our previous published article (Tahir et al., 2024). The algorithm creates a T1 map and extracts the MRI images, displayed high contrast as a bright signal. The tests were performed on equipment at Pinum Cancer Hospital, Punjab Medical College University, Faisalabad, Punjab, Pakistan.

2.12 Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism (version 8.0), with results reported as mean ± SD. As the values of P ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant (denoted by *) and the values of P ≤ 0.01 were considered highly statistically significant (denoted by **).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 The typical features of PMnO2-Dox nanomedicine

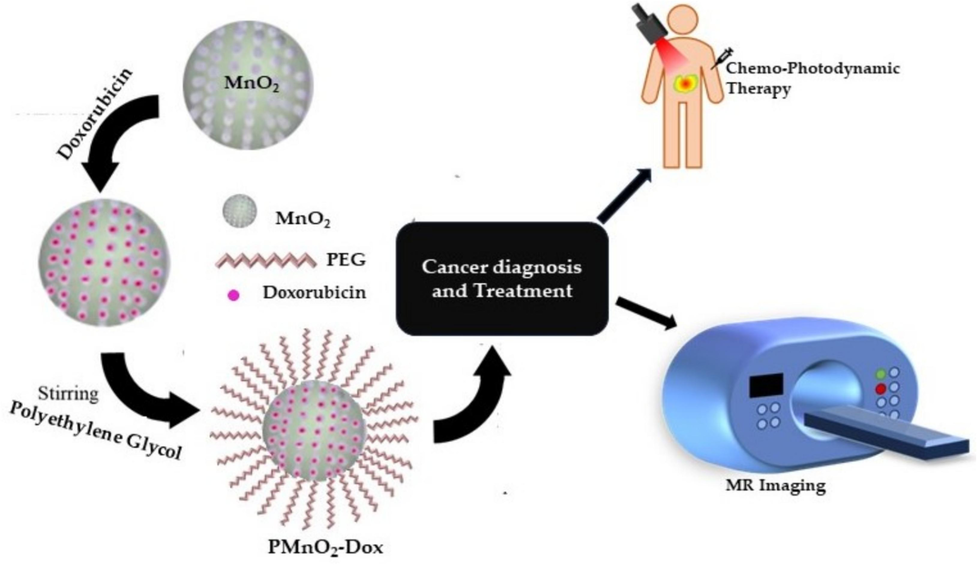

In this study, PMnO2-Dox NPs were constructed through step-by-step coupling and absorption process (Fig. 1). As presented in Fig. 2, the XRD patterns of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs presented strong and typical diffraction peaks at 28.9, 37.7, 42.6, 57.4, 62.1 and 73.1°, corresponding to (1 1 0), (1 0 1), (1 1 1), (2 1 1), (2 2 0) and (3 0 1) crystal planes, respectively. These peaks are attributed to β-MnO2 with tetragonal crystal structure and space group P42/mnm (JCPDS Card No: 024-0735) (Mauri et al., 2020). The additional peaks at 49.8 and 70° in PMnO2-Dox NPs may be attributed to polyethylene glycol. We did not observe other phases of MnO2 except β-MnO2, thus β-MnO2 is the major phases in both MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs. Both have layered structure. The crystallite sizes of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs were estimated to be 25–30 nm respectively, using the Scherer equation.

Schematic diagram of synthesis, chemo-photodynamic therapy and MRI application.

The XRD pattern of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs.

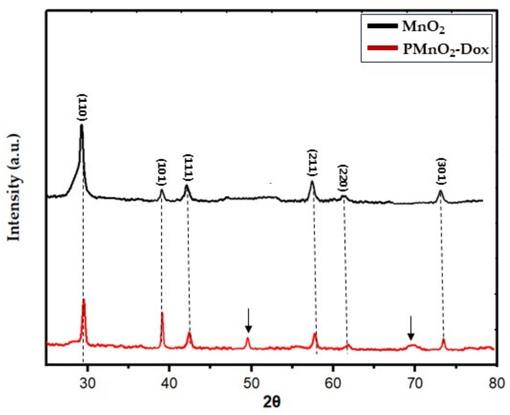

SEM images of MnO2 NPs in Fig. 3(a–b) exhibited that β-MnO2 exhibited the crystallite structure with the size ≈20–30 nm, similar to XRD results. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) is a surface-sensitive quantitative spectroscopic technique that were performed to determine the size distribution profile of small particles in suspension. The hydrodynamic size of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs were measured using DLS analysis. As presented in Fig. 3(c–d), the average size of the nanoparticles was approximately 26.31 ± 0.5 and 29.53 ± 0.67 nm.

The SEM images (a–b) of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs. The DLS images (c–d) of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs.

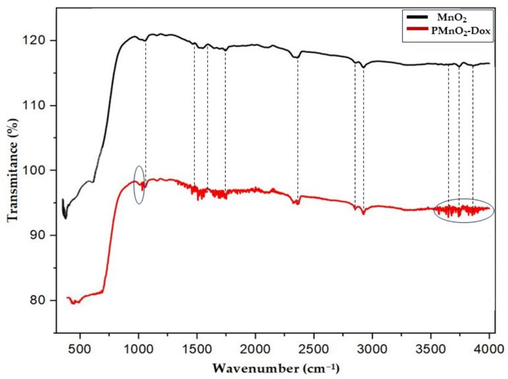

The FTIR spectra of β-MnO2 and PMnO2-Dox NPs were displayed in Fig. 4. The significant absorption bands at 492 and 520 cm−1 were attributed to Mn-O stretching vibrations in MnO6 octahedral in β-MnO2. Compared to β-MnO2, PMnO2-Dox NPs in Fig. 4 showed several new peaks at 1500–2000 cm−1. The absorption peak around ∼1680 and ∼1550 cm−1 were attributed to amide I and II bands, respectively, indicating the presence of Dox in MnO2 NPs. The broad absorption peaks around 3000–3500 cm−1 can be assigned to O—H and N—H stretching vibrations from PEG and Dox, demonstrating that Dox and PEG have been conjugated onto MnO2 NPs.

FTIR of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs.

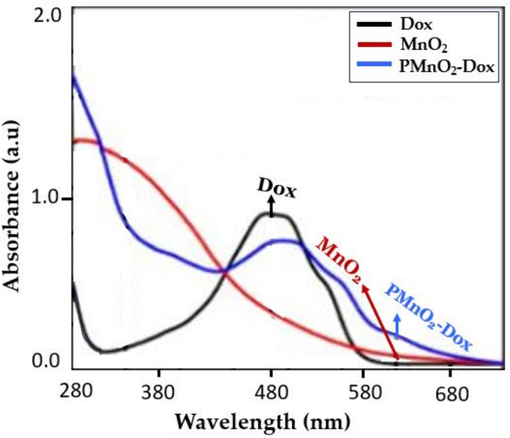

The UV–Visible test was performed to examine the absorption spectra of free Dox, MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs shown in Fig. 5. The appearance of characteristic UV–Visible absorption features of Dox and MnO2 NPs in the range of 480 nm and ∼350–600 nm (i.e., due to the d-d transition of the Mn ion in the tetrahedral structure), respectively indicates the successful loading of Dox in the PMnO2 NPs, As shown in Fig. 5 which are well matched to reported article (Yang et al., 2017).

UV–visible of free Dox, MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs.

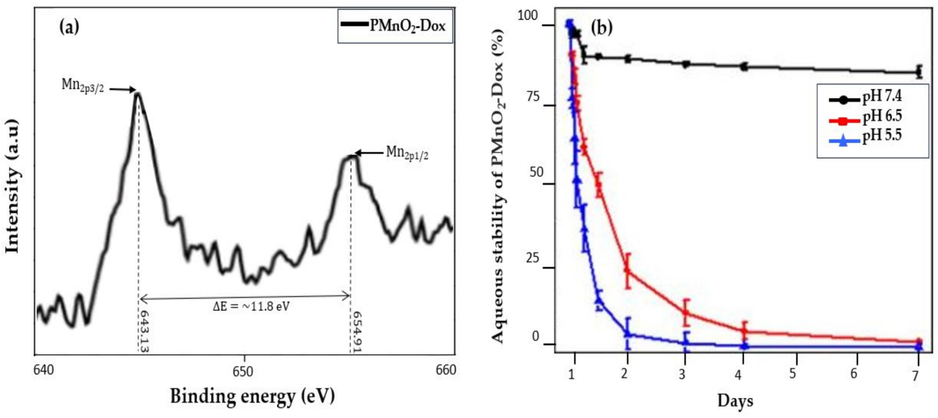

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were used to confirm the formation of PMnO2-Dox NPs. The XPS spectrum showed two distinct peaks at binding energy 643.1 and 654.8 eV which correspond to the Mn2p3/2 and Mn2p1/2 spin–orbit peaks of MnO2 NPs with an average binding energy of ΔE = 11.7 eV, thereby evidencing the successful formation of MnO2 NPs, as shown in Fig. 6(a). The morphology of PMnO2-Dox NPs remained significantly unchanged in a pH 7.4 solution over a period of 3 days, signifying that PMnO2-Dox NPs were stable in a neutral environment. In contrast, PMnO2-Dox NPs displayed a time-dependent degradation pattern in acidic solutions, attributed to the breakdown of MnO2 into Mn2+ ions. The degradation rates were quantified through the decrease in the characteristic absorbance band of MnO2 NPs, as shown in Fig. 6(b). This absorbance band remained stable at pH 7.4 but showed a rapid decline at pH levels of 6.5 and 5.5, thereby further confirming the highly sensitive pH-responsive degradation pattern of PMnO2-Dox NPs.

(a) shows the XPS analysis and (b) shows the aqueous stability of PMnO2-Dox NPs over a period of one week, (n = 3 ± S.D).

3.2 Vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) analysis

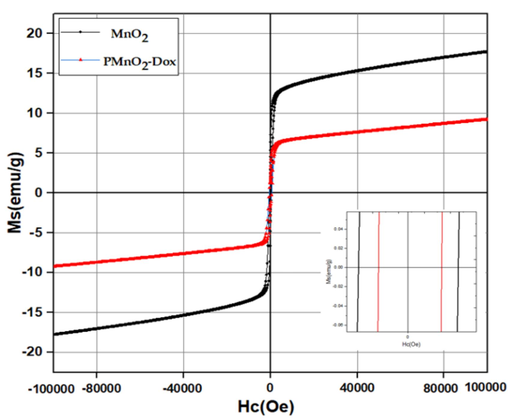

Fig. 7 presented the hysteresis loops of β-MnO2 and PMnO2-Dox NPs. β-MnO2 and PMnO2-Dox NPs presented an S-shaped hysteresis loop with negligible remanence and coercivity, indictive of superparamagnetic nature (Chen et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2017; Ziyaee et al., 2023). VSM data exhibited that the magnetic saturation of PMnO2-Dox NPs is lower than that of β-MnO2, attributed to the presence of the non-magnetic PEG and Dox on the surface of β-MnO2. Though slightly reduced magnetism of the PMnO2-Dox NPs, the superparamagnetic properties of β-MnO2 and PMnO2-Dox NPs make them ideal MRI contrast agents for diagnosis, imaging, and magnetic drug delivery and hyperthermia applications.

Hysteresis loops of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs.

3.3 Prevention and control of Dox release from PMnO2-Dox

Doxorubicin is a clinically approved anticancer drug, which may be loaded into PMnO2-Dox NPs via stirring. As depicted in demonstrated in Fig. 8, the release of Dox was superficial upto 48 h of time of incubation at pH 7.4 due to neutral pH environment base surrounding, but remarkable Dox release trend was noticed in acidic environment (pH 5.5, and 6.5). It has been seen formation of ions and the scarcity of H-bonding between doxorubicin and core shell nanomaterials of MnO2 NPs due to thermal temperature and acidic body environment (Choi et al., 2013). In addition, significant amount of PMnO2-Dox NPs accumulation towards cancerous sites due to low density lipoproteins receptor was noted as compare to healthy cells. Also, polymer coated materials were the basic requirement to overcome MDR which has been adopted in current experimental scheme. Once PMnO2-Dox NPs accumulates at the cancerous site, the release rate of Dox is enhanced. The reason for this enhancement is that cancer cells have a much higher metabolic rate than healthy cells, and the cancer site becomes acidic due to the production of lactic acid. This enhancement in the release of Dox leads to the death of cancer cells through apoptosis, and some cell death attributed to necrosis. In addition, the release of Dox from PMnO2-Dox NPs can be significantly enhanced by laser irradiation which may increase the entire temperature. This was ascribed to the heat produced by the photodynamic effect of MnO2 NPs under visible laser irradiation to decomposition of Dox from PMnO2-Dox NPs. These outcomes confirm that doxorubicin release from PMnO2-Dox NPs could be triggered by the acidic environment of the cancer site and enhanced by visible laser irradiation, thereby improving the therapeutic effect (Yang et al., 2023; Ou et al., 2021).

The Dox release kinetic curves of PMnO2-Dox NPs showing Dox release increases in acidic environment (n = 3 ± S.D), where * is significant for P ≤ 0.05 and ** is highly significant for P ≤ 0.01.

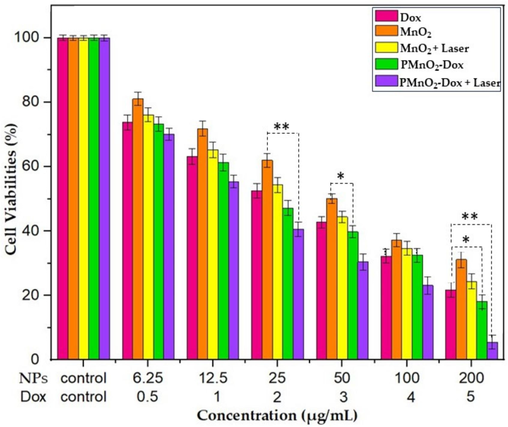

3.4 Photodynamic and chemodynamic performance

The MnO2 NPs at higher concentrations exhibited slightly higher cytotoxicity towards MCF-7 cells, which may be attributed due to the Fenton reaction leading to cancer cell death (Xu et al., 2020). MCF-7 cells were exposed with doxorubicin, MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs with and without laser irradiation under recommended dose of light (80 j/cm2) That experiments demonstrated the concentration-dependent cytotoxicity as depicted in (Fig. 9). The PMnO2-Dox NPs + laser group exhibited a significant cell killing response due to photodynamic activity as compare to toxicity of MnO2 NPs in the absence of light/monotherapy groups due to the synergistic treatment. After 48 h of incubation, satisfactory PDT response while using PMnO2-Dox NPs with effective wavelength of laser trend depicted in (Fig. 9). In addition, Fig. 9 shows that the PMnO2-Dox NPs binds to doxorubicin, indicating that doxorubicin can be successfully delivered into cancer cells for chemotherapy (Zhang et al., 2017; Hu et al., 2013). Overall results showed bare MnO2 NPs, Dox and MnO2 NPs with laser irradiation illustrated superficial response for treatment as comparison of PMnO2-Dox NPs + laser group (Fig. 9). However, the PMnO2-Dox NPs + laser group exhibited obvious marvelous cells death via apoptosis. These results presented that PMnO2-Dox NPs + laser had significantly higher cell death due to synergistic response of chemo-photodynamic and CDT.

Cell viabilities of MCF-7 cells treated by MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs with or without laser irradiation for 48 h, (n = 3 ± S.D). Laser conditions: visible blue light −440/480 nm range, Starlight pro, Mectron Italy, for 10 mins, the concentrations of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs were in the range of 6.25–200 µg/mL. The Dox concentration in PMnO2-Dox NPs corresponded to 5 µg/mL, where * is significant for P ≤ 0.05 and ** is highly significant for P ≤ 0.01.

In this detailed discussion, Bi et al. (2019) reported that MnO2 nanostructure can react with intracellular GSH to decrease its level and increase the efficiency of PDT and remarkable improvement in MRI images. Fan et al. (2016) reported that the nanostructure that is effectively designed inhibits the production of extracellular 1O2 (singlet oxygen) by Ce6, leading to minimal side effects. Upon endocytosis, intracellular GSH degrades MnO2 nanostructure. The nanostructure is degraded, resulting in the synchronous release of Ce6 and depletion of GSH, enabling highly efficient PDT.

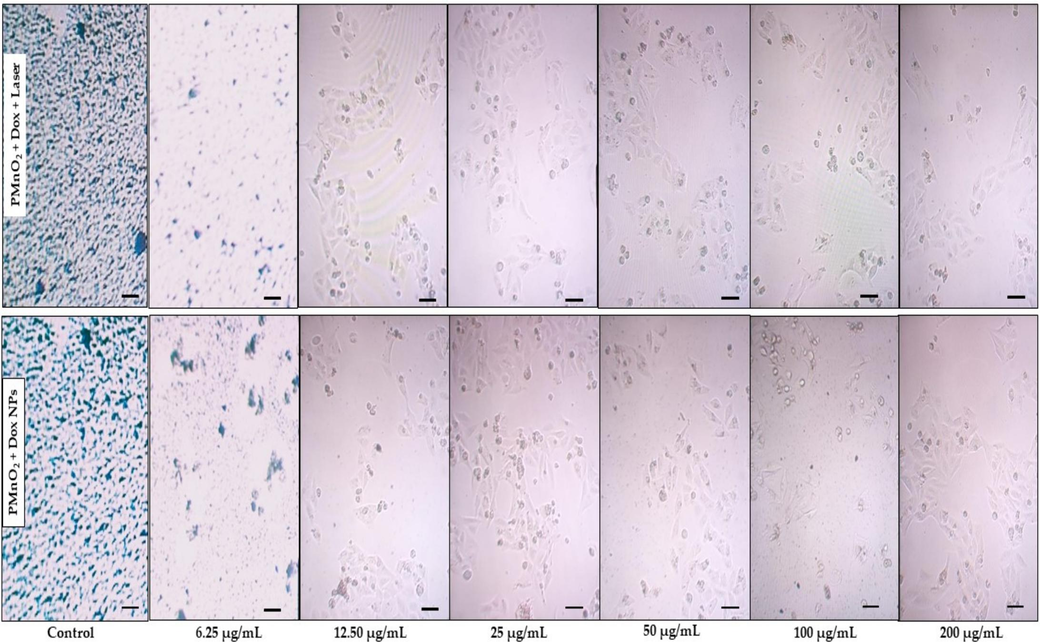

3.5 Cell availability

Encouraged by their PDT and CDT performance, we evaluated the cell viability of Dox, MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs with or without laser irradiation on MCF-7 cells. Cell viabilities of MCF-7 cells were tested at different concentration of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs (0, 6.25, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200 µg/mL) for 48 h. As shown in Fig. 9, all treatment groups exhibited the dose-dependent cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells. By contrast, MnO2 NPs slightly reduced the cell viability of MCF-7 cells under 480 nm laser irradiations, with the IC50 of 17.66 µg/mL. Suggesting a potential light-mediated enhancement of their therapeutic effect. Remarkably, the inclusion of Dox in MnO2 NPs significantly enhanced the cytotoxicity of MCF-7, suggesting a potential light-mediated enhancement of their therapeutic effect, possibly through a CDT mechanism. The inclusion of Dox to PMnO₂ NPs significantly inhibited MCF-7 cell growth with the IC50 of 14.94 µg/mL due to ROS generation from CDT and interfering with DNA replication and inducing apoptosis through chemotherapy. The IC50 values of the DOx, MnO2 NPs, MnO2 NPs+ laser, PMnO2-Dox NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs + laser are given in Table 1. More interestingly, the combination of PMnO₂ and Dox in the treatment of MCF-7 cells under laser irradiation led to most profound reduction in cell viability across all concentrations. Thus, the combinational therapy of Dox with PMnO₂ under laser irradiation offers a multifaceted PDT/CDT/chemotherapy strategy for cancer treatment, potentially reducing associated side effects, drug resistance, and the highest therapeutic efficacy of 94.87 % was obtained at a concentration of 200 µg/mL of PMnO2-Dox NPs with laser irradiation. The morphologies of MCF-7 cells treated by PMnO2-Dox NPs with or without laser irradiation have been further explored. As shown in Fig. 10, cancer cell apoptosis were observed in all PMnO2-Dox NPs with or without laser irradiation. As the concentrations of MnO2 and Dox increased in the treatment, the morphology of MCF-7 cells drastically altered, leading to a drastic reduction in cell viabilities due to apoptosis, and some cell death occurs through necrosis. Under laser irradiation, more apoptosis was observed. These data were consistent with the cell viability. The increased efficiency of PMnO2-Dox NPs with laser irradiation was ascribed to the synergistic effects of PDT, CDT and chemotherapy as demonstrated in Fig. 9.

Name of Materials

Dox

MnO2 NPs

MnO2 NPs + Laser

PMnO2-Dox NPs

PMnO2-Dox NPs+ Laser

IC50 Value (µg/mL)

16.70

24.05

17.66

14.94

14.15

Morphological and apoptotic analysis of MCF-7 cells treated by PMnO2-Dox NPs with and without laser irradiation for 10 min. Scale bar: 100 µm for each display.

Flow cytometry (FC) were employed to quantitatively measure the apoptotic impact of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs. After 48 h of treatment with MnO2 NPs, MnO2 NPs + laser, PMnO2-Dox NPs, and PMnO2-Dox NPs+ laser, the apoptosis rates were determined to be 12.97 ± 1.91, 15.11 ± 1.57, 27.27 ± 2.69, and 29.75 ± 2.37 %, respectively, as shown in Fig. 11. Notably, the apoptosis rate of the PMnO2-Dox NPs+ laser group was substantially greater compared to other groups.

Flow cytometry analysis of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs with and without laser irradiation revealed the apoptosis ratio.

3.6 Magnetic resonace imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs incubated in PBS solution for 4 h were measured using an (MRI SIGNA) 7 T scanner. As shown in Fig. 12(a, b), the MRI bright signal enhanced with the increase of MnO2 concentration from 0–1 mM, determining that manganese is a T1 contrast agent. The MRI experiment was done at different concentration (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 and 1 mM). In comparison with MnO2 NPs, and PMnO2-Dox NPs exhibited reduced T1 relaxation and significantly enhanced signal intensity in T1-weighted images. In vitro and in vivo, these magnetic MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs offer marvelous T1 bright contrast agents for MRI due to the decomposition of MnO2 or induced of Mn2+ ion under acidic condition. In the current study, MnO2 NPs exhibits less brightness than PMnO2-Dox NPs. Hence, PMnO2-Dox NPs can be applied as a T1 bright contrast agent for efficient outcomes. Furthermore, the PMnO2-Dox NPs were employed to calculate the r1 relaxivities under the basic to acidic condition. It can be noted that under varying pHs (7.4, 6.5 and 5.5 pH) conditions, the value of r1 remarkably increased from very first value 0.049–8.97 mM−1S−1 after incubation in 5.5 pH PBS for 4 h, shown in Fig. 12(c). In this discussion, Hu et al. (2013) reported that PVP-coated manganese oxide nanoparticles (MnO@PVP NPs) can improve the T1 signal and utilized to visualize tumor images. In vitro and in vivo analysis of MnO@PVP NPs proposed that are promising candidate for MRI T1 bright contrast agents.

(a–b) shows the MRI images of MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs at different concentration (0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 and 1 mM) and (c) shows the r1 relativities for PMnO2-Dox NPs were 0.049, 5.01 and 8.97 mM−1S−1 at 7.4, 6.5 and 5.5 pH, respectively, (n = 3 ± S.D).

4 Conclusions

The developed PMnO2-Dox NPs for improved chemo-photodynamic therapy and MRI application. Crystallography of PMnO2-Dox were employed by using XRD analysis, which confirmed tetragonal crystal structure. Surface morphology was confirmed via SEM analysis, results indicated the spherical and asymmetric agglomerated nanocluster of PMnO2-Dox NPs. The functional groups and magnetization were confirmed using FTIR and VSM analysis, respectively. MnO2 NPs provided PDT upon laser irradiation, doxorubicin certainly release at the cancer site for chemotherapy due to laser irradiation and pH value reduction of PMnO2-Dox NPs. Associated with previously described MnO2 NPs and PMnO2-Dox NPs exhibits efficient drug loading and release rewards. This highly sensitive pH-responsive of PMnO2-Dox NPs causes effective drug release under acidic pH environment. PMnO2-Dox NPs not only improves the efficacy of chemo-photodynamic therapy due to synergistic response as well as improved MRI imaging via boosting T1 MRI contrast. In addition, it can also inhibit the growth of primary and secondary cancers without light exposure. On the basis of results, it is concluded that PMnO2-Dox NPs not only convenient for cancer treatment via chemo-photodynamic therapy but also address the way towards a comprehensive strategy for MRI application via bright contrast agent T1 after overcoming the problem of MDR and synergistic response of therapeutic analysis.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Muhammad Asif: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Software, Investigation, Validation, Supervision, Project administration. M. Fakhar-e-Alam: Conceptualization, Investigation, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. Mudassir Hassan: Formal analysis, Visualization, Methodology, Resources. Hassan Sardar: Methodology, Resources, Formal analysis. M. Zulqarnian: Software, Resources, Formal analysis. Li Li: Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Asma A. Alothman: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources, Visualization. Asma B. Alangary: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources, Visualization. Saikh Mohammad: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Resources, Visualization.

Acknowledgment

This work was funded by the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSP2024R243) King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Synthesis and characterization of chemically and green-synthesized silver oxide particles for evaluation of antiviral and anticancer activity. Pharmaceuticals. 2024;17(7):908

- [Google Scholar]

- Glutathione and H2O2 consumption promoted photodynamic and chemotherapy based on biodegradable MnO2–Pt@ Au25 nanosheets. Chem. Eng. J.. 2019;356:543-553.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glutathione and H2O2 consumption promoted photodynamic and chemotherapy based on biodegradable MnO2–Pt@Au25 nanosheets. Chem. Eng. J.. 2019;356:543-553.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microwave-hydrothermal crystallization of polymorphic MnO2 for electrochemical energy storage. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2013;117:10770-10779.

- [Google Scholar]

- Break-up of two-dimensional MnO2 nanosheets promotes ultrasensitive pH-triggered theranostics of cancer. Adv. Mater.. 2014;26:7019-7026.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Monodisperse hollow MnO2 with biodegradability for efficient targeted drug delivery. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng.. 2020;6:4985-4992.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer-generated lactic acid: a regulatory, immunosuppressive metabolite? J Pathol.. 2013;230:350-355.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydrothermal synthesis of monodisperse magnetite nanoparticles. Chem. Mater.. 2006;18:4399-4404.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Intracellular glutathione detection using MnO2-nanosheet-modified upconversion nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2011;133:20168-20171.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of C6 cell membrane-coated doxorubicin conjugated manganese dioxide nanoparticles and its targeted therapy application in glioma. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2023;180:106338

- [Google Scholar]

- Antitumor activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles fused with green extract of Nigella sativa. J. Saudi Chem. Soc.. 2024;28(2):101814

- [Google Scholar]

- Intelligent MnO2 nanosheets anchored with upconversion nanoprobes for concurrent pH-/H2O2-responsive UCL imaging and oxygen-elevated synergetic therapy. Adv. Mater.. 2015;27:4155-4161.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A smart photosensitizer-manganese dioxide nanosystem for enhanced photodynamic therapy by reducing glutathione levels in cancer cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2016;55:5477-5482.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic nanoparticles: synthesis, stabilization, functionalization, characterization, and applications. J. Iran. Chem. Soc.. 2010;7:1-37.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Development of a novel fluorescence spectroscopy-based method using layered double hydroxides to study degradation of E. coli in water. J. Mol. Struct.. 2024;1310:138248

- [Google Scholar]

- Intra/extracellular lactic acid exhaustion for synergistic metabolic therapy and immunotherapy of tumors. Adv. Mater.. 2019;31:1904639

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Al-substituted zinc spinel ferrite nanoparticles: preparation and evaluation of structural, electrical, magnetic and photocatalytic properties. Ceram. Int.. 2020;46:14195-14205.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Water-soluble and biocompatible MnO@PVP nanoparticles for MR imaging In Vitro and In Vivo. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol.. 2013;9:976-984.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Better reporting and awareness campaigns needed for breast cancer in Pakistani women. Cancer Manag. Res.. 2021;13:2125-2129.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hydrogen peroxide inducible DNA cross-linking agents: targeted anticancer prodrugs. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2011;133:19278-19281.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biodegradable PEG-based amphiphilic block copolymers for tissue engineering applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng.. 2015;1(7):463-480.

- [Google Scholar]

- A pH-sensitive drug delivery system based on hyaluronic acid co-deliver doxorubicin and aminoferrocene for the combined application of chemotherapy and chemodynamic therapy. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces. 2021;203:111750

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impairing tumor metabolic plasticity via a stable metal-phenolic-based polymeric nanomedicine to suppress colorectal cancer. Adv. Mater.. 2023;35(23):2300548

- [Google Scholar]

- Biomarker-driven molecular imaging probes in radiotherapy. Theranostics. 2024;14(10):4127.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumor-pH-sensitive PLLA-based microsphere with acid cleavable acetal bonds on the backbone for efficient localized chemotherapy. Biomacromolecules. 2018;19(7):3140-3148.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxygen-boosted immunogenic photodynamic therapy with gold nanocages@manganese dioxide to inhibit tumor growth and metastases. Biomaterials. 2018;177:149-160.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Design of carboxylated Fe3O4/poly(styrene-co-acrylic acid) ferrofluids with highly efficient magnetic heating effect. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp.. 2011;384:23-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of magnetite nanoparticles via a solvent-free thermal decomposition route. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.. 2009;321:1256-1259.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MnO nanoparticles embedded in functional polymers as T1 contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.. 2020;3:3787-3797.

- [Google Scholar]

- MnO nanoparticles embedded in functional polymers as T1 contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.. 2020;3:3787-3797.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global breast cancer mortality statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin.. 1999;49:138-144.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer efficiency of curcumin-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles/nanofiber composites for potential postsurgical breast cancer treatment. J. Drug Del. Sci. Technol.. 2021;61:102170

- [Google Scholar]

- MnO2-based nanomotors with active Fenton-like Mn2+ delivery for enhanced chemodynamic therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13:38050-38060.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetics of monodisperse iron oxide nanocrystal formation by “heating-up” process. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2007;129:12571-12584.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biophotonic techniques for manipulation and characterization of drug delivery nanosystems in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett.. 2012;327:111-122.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new sono-chemo sensitizer overcoming tumor hypoxia for augmented sono/chemo-dynamic therapy and robust immune-activating response. Small. 2023;19

- [Google Scholar]

- Monodisperse MFe2O4 (M = Fe Co, Mn) nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2004;126:273-279.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.. 2020;71(2021):209-249.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of gadolinium doped manganese nano spinel ferrites via magnetic hypothermia therapy effect towards MCF-7 breast cancer. Heliyon. 2024;10(3):e24792

- [Google Scholar]

- Spinel ferrite nanoparticles: synthesis, crystal structure, properties, and perspective applications. Springer Proc. Phys.. 2017;195:305-325.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- MnO2-laden black phosphorus for MRI-guided synergistic PDT, PTT, and chemotherapy. Matter 2019

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multifunctional PVCL nanogels with redox-responsiveness enable enhanced MR imaging and ultrasound-promoted tumor chemotherapy. Theranostics. 2020;10(10):4349.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hollow MnO2 as a tumor-microenvironment-responsive biodegradable nano-platform for combination therapy favoring antitumor immune responses. Nat. Commun.. 2017;8:902

- [Google Scholar]

- Hollow MnO2 as a tumor-microenvironment-responsive biodegradable nano-platform for combination therapy favoring antitumor immune responses. Nat. Commun.. 2017;8(1):902

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of acid-driven magnetically imprinted micromotors and selective loading of phycocyanin. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023

- [Google Scholar]

- Oxygen-generating MnO2 nanodots-anchored versatile nanoplatform for combined chemo-photodynamic therapy in hypoxic cancer. Adv. Funct. Mater.. 2018;28:1706375

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tumor environment responsive degradable CuS@mSiO2@MnO2/DOX for MRI guided synergistic chemo-photothermal therapy and chemodynamic therapy. Chem. Eng. J.. 2020;389:124450

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Redox-responsive and drug-embedded silica nanoparticles with unique self-destruction features for efficient gene/drug codelivery. Adv. Funct. Mater.. 2017;27

- [Google Scholar]

- Activatable fluorescence/MRI bimodal platform for tumor cell imaging via MnO2 nanosheet-aptamer nanoprobe. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2014;136:11220-11223.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Modulation of hypoxia in solid tumor microenvironment with MnO2 nanoparticles to enhance photodynamic therapy. Adv. Funct. Mater.. 2016;26:5490-5498.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of MnO2@poly-(DMAEMA-co-IA)-conjugated methotrexate nano-complex for MRI and radiotherapy of breast cancer application. MAGMA. 2023;36:779-795.

- [Google Scholar]