Translate this page into:

A review on catalytic reduction/degradation of organic pollution through silver-based hydrogels

⁎Corresponding author. ghasemzadeh@qom-iau.ac.ir (Mohammad Ali Ghasemzadeh)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Various challenging pollutants are produced in the environment by organic materials of diverse industries including leather, paint, and textile. Nowadays, it is vital to develop efficient manners regarding the fundamental issues and removing pollutants. Such pollutants can be effectively removed from the environment through heterogeneous catalysts. Recently, a huge deal of interest has been attracted by hydrogel-based metal catalysts as heterogeneous and efficient catalysts. In this regard, silver with its unique features is suitable for environmental remediation. Hence, the present review deals with summarizing the present advances in the synthesis of silver-based hydrogel catalysts, as well as their applications for environmental remediation. Some advantages have been proposed using silver-based hydrogel catalysts suggested including high catalytic ability, reusability, easy work-up, and simple synthesis.

Keywords

Ag-based hydrogel catalyst

Organic pollutant

Environmental remediation

Silver nanoparticles

Hydrogel

1 Introduction

Various industries have been expanded with the advancement of technology increasing pollution. Several organic pollutants enter water and the environment and cause harmful impacts from different factories like paint, textile, leather, etc. Indeed, aquatic systems and human health are affected by the incidence of these organic pollutants since it is difficult to eliminate these pollutants from the environment (Prabakar et al., 2018). Moreover, organic pollutants are toxic heavily thus harmful to the environment and humans such as organic dyes (Methyl red, Rhodamine B, and methylene blue (MB), antibiotics, herbicides, phenols compounds, phthalate esters, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Feng et al., 2021). Nowadays, organic waste has attracted a huge deal of attention because widespread diseases for humans and aquatic animals, high resistance, and long life and durability are caused by its discharge into water and land. Among these compounds are toxic nitro compounds causing water pollution (Oyewo et al., 2020). One of the most introduced nitro compounds is 4-Nitrophenol (4-NP) causing severe pollution in the environment owing to its high chemical stability and toxicity (Formenti et al., 2019; Sargin, 2019). Organic dyes are complex molecules with higher resistance to heat and detergents and lead to dyes on fabrics or materials. Furthermore, they are the key part of industrial processes for various yields. Most organic dyes possess numerous features including little water solubility and biodegradability. The dyes are occasionally poisonous and known as hazardous, mutagenic, or teratogenic (Nicewicz and Nguyen, 2013; Carvalho et al., 2008). Various kinds of materials and thus numerous methods can be used to remedy the environment (Li et al., 2019). Since some organic pollutants contain complex compounds and possess low reactivity and high volatility, their elimination is a key and controversial challenge for researchers (Ali Mansoori et al., 2008; Pathakoti et al., 2018).

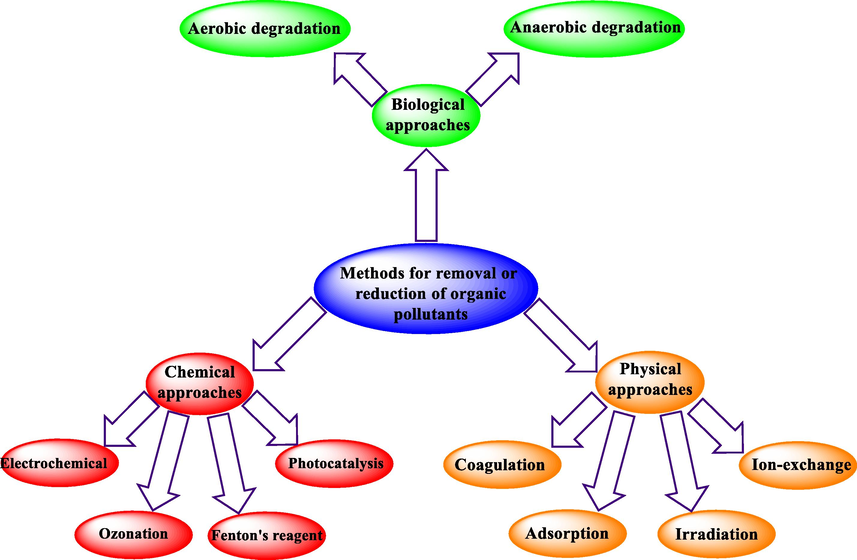

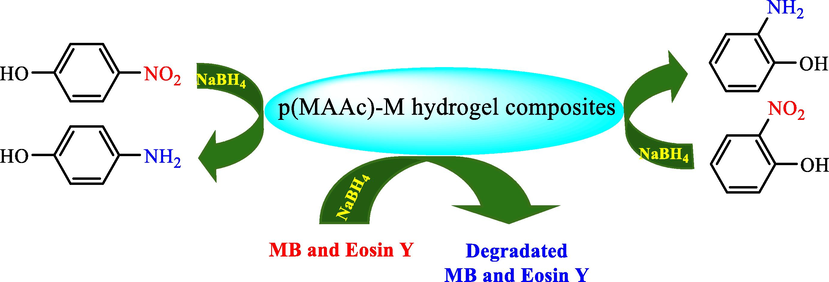

Selecting an eco-friendly and effective method to eliminate environmental pollution is one of the essential tasks. Nanoparticles with certain physical and chemical properties are among the promising compounds for remediation of the environment from pollution (Baruah and Dutta, 2009; Yadav et al., 2021). Numerous approaches have been proposed to remove or reduce organic pollutants, such as biological, physical, and chemical approaches (Scheme 1) (Karpińska and Kotowska, 2019; Ali et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2018). Some approaches presented in Scheme 1 are not useful and practical owing to their disadvantages like higher cost, energy consumption, and the production of dangerous by-products.

Multiple methods for the elimination or reduction of inorganic/organic pollutants.

According to several recent studies, homogenous or heterogeneous catalysts are very effective to remove organic pollutants from the environment (Abdelwahab and Morsy, 2018; Liu et al., 2020; Dayanidhi et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020; Kalkan Erdoğan and Inter, 2020; Biswas and Banerjee, 2014; Cong et al., 2012). Metal nanoparticles (MNPs) or metal complexes can be the base for homogenous or heterogeneous catalysts utilized for environmental applications (Das et al., 2019; Veisi et al., 2019; Gürbüz et al., 2021; Amir et al., 2015; Amir et al., 2016; Veisi et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2015; Nasrollahzadeh et al., 2020). Homogeneous catalysts are not commonly used owing to their disadvantages, and most importantly their separation problem from the reaction mixture. Therefore, the use of heterogeneous catalysts has been interesting as a result of their numerous advantages, such as wide availability of various supports, insolubility in solvents, high stability, and most importantly, the capability for recycling and reusing the reaction mixture (Akintelu et al., 2020; Védrine, 2017; Gao et al., 2017). Nowadays, a huge deal of attention has been attracted by nanotechnology as a result of its various applications. Indeed, nanotechnology represents particles with the size of 1 to 100 nm. Nanoparticles (NPs) possess exceptional physical and chemical properties, such as higher reactivity and large surface area to volume ratios because of their specific nanoscale size (Qin et al., 1899; Dadashi et al., 2021). Different metal nanoparticles (MNPs) like Au, Pd, Cu, and silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) can be used for the effective removal of pollutants from the environment (Aranaz et al., 2019; Fu et al., 2019; Hasan et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020).

Hydrogels are three-dimensional polymeric materials with crosslinked hydrophilic networks. The presence of numerous functional groups in the polymer chains interacted through either bonding or intermolecular forces with each other forms a chemically stable network system (Gulrez, 2015). These hydrophilic structures can absorb substantial amount of water or biological fluids, in which cross linking improves physical integrity of hydrogels as well as their insolubility in water. Hydrogels have strengthened their position among other supporting carrier systems due to several advantages such as simple in-situ synthesis, providing high stability to MNPs, and facile recycling of catalyst materials without any noticeable leaching (Shi et al., 2008; Sahiner et al., 2010). Furthermore, these 3D viscoelastic porous matrices with the range of 1–10 nm pore diameters represent a high permeability for reactant molecules through their network, which facilitates the accessibility to the active sites within the polymeric system. They also closely mimic natural living tissue more than any other type of synthetic biomaterials, owing to their high soft consistency and water content (Caló and Khutoryanskiy, 2015). Because of these attractive properties, hydrogels have received significant attention in drug delivery, chemical sensors, catalyst, and optics (Slaughter et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2020; Niu et al., 2018; West and Hubbell, 1995; Gwon et al., 2020; Vashist et al., 2014; George et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2017).

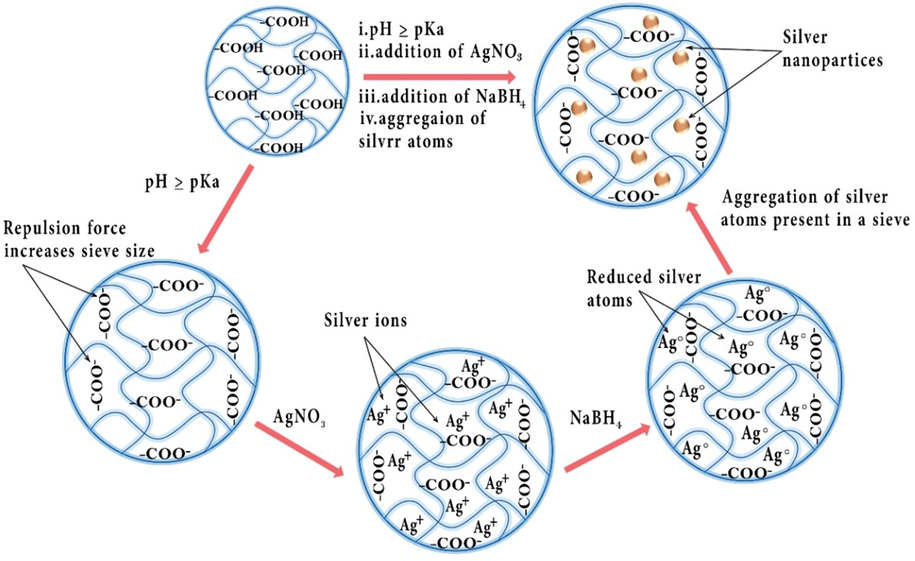

Ag-based hydrogels or Ag NPs are extensively used in different reactions particularly the removal of pollutants from the environment, because of their exceptional features (Xin et al., 2019). H2O presence in the hydrogel structures facilitates ion transformation and results better Ag+ and Ag NPs loading (Tang et al., 2018). On the other hand, many non-structurally modified hydrogels contain different functional groups that better coordinate Ag+ and Ag NPs (Iqbal et al., 2020). Also, the pore size of the hydrogels, which has a direct effect on the performance of the associated catalysts, is easily adjustable during synthesis. All of these advantages make hydrogels a better choice than other substrates such as zeolites (Kanan et al., 2000), carbon based material (Taka et al., 2020), etc. for loading Ag NPs. Indeed, noteworthy properties of Ag NPs have been well recognized including antibacterial, antiviral, and antifungal activity (Murthy et al., 2008; Fan et al., 2021; Leng et al., 2019; Montazer et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2019; Malik et al., 2020). Thus, they can be utilized as water purifiers. Ag NPs can join various other constituents like metal oxides and polymers and establish the general properties of the resultant nanocomposite. There are two common methods employed for the synthesis of Ag NPs-incorporated hydrogels including (A) in-situ crosslinking pre-formed Ag NPs in aqueous solutions with the hydrogel copolymers and (B) physically embedded Ag NPs in pre-formed hydrogel systems (Li et al., 2022). The hydrogels prepared via the first strategy typically exhibits good thermal stability and biocompatibility alongside a negligible metal leaching (Niu et al., 2018; Li et al., 2022). On contrary, synthesizing Ag-based hydrogels via physically entrapping metal nanoparticles leads to the formation of hydrogels with higher mechanical stability (Xie et al., 2018). It is demonstrated that the catalytic activity of MNPs in Ag-based hydrogels is modulated by a thermodynamic transition occurring within the carrier system (Lu et al., 2006). The swelling and the shrinking of the hydrogel shell in various temperatures leads to the fluctuating distance of the Ag NPs and varying the diffusion of reactants through the network. At low temperatures (T < 30 °C), the MNPs incorporated in the hydrogel are suspended in water, where the reagents can freely reach to the nanoparticles. On the other hand, the network shrinks at high temperatures and the catalytic activity of the nanoparticles is significantly declined. It is demonstrated that the size and stability of Ag NPs are determined by the hydrogel network structure (Lu et al., 2006; Mohan et al., 2006). For example, an increase of the cross-linker density in the polymeric system leads to the formation of Ag NPs with smaller sizes and increased total surface area (Lu et al., 2006). The free space (porosity), affected by the cross-linker density, within the hydrogel network can also control the aggregation of the silver nanoparticles (Mohan et al., 2006). The Ag NPs are generally incorporated into the hydrogel system via the interaction of the Ag+ ions with various metal-binding functionalities in the hydrogel chains. Highly cross-linked hydrogels diminishes the reduction rate of silver ions by the reducing agent, e.g., NaBH4, mainly due to the restriction of the penetration capacity of the solute (Mohan et al., 2006). Nevertheless, it has been shown that the close proximity of metal chelating units in the hydrogels with high cross-linker density leads to the higher stabilization of the Ag NPs.

2 Classification of hydrogels

Hydrogels are divided into numerous types based on their preparation manner, ionic charge, and physical structure properties. They can be homo-polymer hydrogels, co-polymer hydrogels, multi-polymer hydrogels, or interpenetrating network hydrogels, depending on how they're made. Homo-polymer hydrogels are cross linked networks of hydrophilic monomer units of one kind, co-polymer hydrogels, on the other hand, are made by cross linking chains made up of two co-monomer units, at least one of which must be hydrophilic in order for them to swell in water. Three or more co-monomers react together to form multi-polymer hydrogels. Finally, interpenetrating network hydrogels can be made in one of two ways: in a premade network or in solution. The most typical strategy is to polymerize one monomer within a various cross linked hydrogel network. The monomer polymerizes to form a polymer or a second cross linked network that is intermeshed with the first network.

Hydrogels can also be categorized in a variety of ways. Ionic hydrogels with ionic charges on the backbone polymers are classed as: (A) uncharged; (B) anionic hydrogels (containing only negative charges); (C) cationic hydrogels (having only positive charges); or (D) ampholytic hydrogels (having both positive and negative charges). The net charge on these last gels could be negative, positive, or neutral.

Hydrogels can be characterized as either (A) amorphous hydrogels (with covalent cross-links) or (B) semi-crystalline hydrogels, depending on the physicochemical structural properties of the network (may or may not have covalent cross-links). The macromolecular chains in amorphous hydrogels are randomly organized. Self-assembled regions of organized macromolecular chains characterize semi-crystalline hydrogels (crystallites) (Zhao et al., 2020; Niu et al., 2018).

3 Preparation of hydrogels

Small multifunctional molecules, such as monomers and oligomers, are frequently brought together and react to form a network structure to make covalently cross-linked hydrogels. Large polymer molecules can sometimes be cross-linked with small multifunctional molecules. The reaction of two chemical groups on two distinct molecules, which can be initiated by catalysts, photo-polymerization, or radiation cross-linking, can produce such cross-linking.

Free radical reactions are used in a variety of ways to make cross-linked hydrogels. The first entails a copolymerization-cross-linking reaction involving one or more monomers and one multifunctional monomer present in small amounts. Two water-soluble polymers can be cross-linked together using a similar mechanism that involves the generation of free radicals on both polymer molecules, which combine to create the cross-link. These reactions are known as free radical polymerization or cross-linking reactions, and they can be triggered by the decomposition of peroxides or azo compounds, or by the use of ionizing radiation or ultraviolet (UV) light. Ionizing radiation manners use gamma rays, X-rays, or electron beams to excite a polymer and cause free radical reactions to generate a cross linked structure. These free radical reactions, which normally take place in the absence of oxygen or air (note: some polymers are damaged by radiation, especially in air), result in the rapid development of a three-dimensional network (Zhao et al., 2020).

Chemical cross-linking is another method that involves reacting a linear or branched polymer directly with a di-functional or multi-functional low-molecular-weight cross-linking agent. Through its di- or multi-functional groups, this agent frequently connects two higher-molecular-weight chains. There are several well-known processes for joining hydrophilic polymers together or with cross-linkers to generate hydrogels, including some newer techniques that are gaining traction, such as the Michael addition of dithiol compounds with di-vinyl compounds (Tang et al., 2018). A related technique involves the cross-linking of a tiny bi-functional molecule with linear polymeric chains that have pendant or terminal reactive groups such as –OH, –NH2, NCO, or –COOH. Enzymes can also be used to cross-link natural polymers like proteins in a similar way.

In the present review, the main advantageous and properties of silver-based hydrogel in advancing the novel, safe, and efficient catalysts are described. We gathered the recent signs of advances in preparing Ag-based hydrogels as well as their application to remedy environmental pollution.

4 Ag-based hydrogels in the removal of environmental pollutants

In this section, the recent cases of silver-based hydrogel as heterogeneous catalysts to remedy environmental pollutants are summarized.

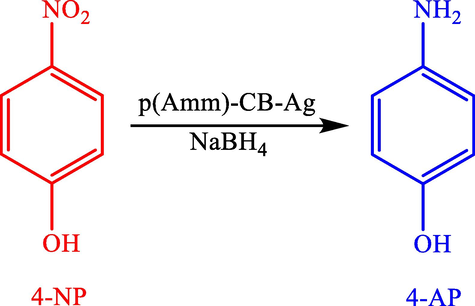

A simple route was reported by Sahiner et al. (2012), to prepare a composite hydrogel on the basis of acrylamide-chicken biochar (AAm)-CB and use it as a template in preparing the silver MNPs (Sahiner et al., 2013). Using the synthesized silver nanoparticles as impressive stable and catalysts, 4-nitrophenol (4-NP) to 4-aminophenol (4-AP) is reduced (Scheme 2). Moreover, the catalyst was reused 5 successive times.

Reduction of 4-NP to 4-AP by p(Amm)-CB-Ag.

A scalable, facile, and enviremently-friendly technique was developed by Ai and Jiang (2013) to fabricate Ag-entraped alginate hydrogels (Ag@AHs) (Ai and Jiang, 2013). In this synthetic approach, Ag ions acting as a crosslinker of polysaccharide chains induced the alginate gelation to ensure the successful formation of uniformly distributed metallic silver nanoparticles with simulated solar light irradiation. Ag@AHs was used as a potential catalyst to reduce 4-NP to 4-AP with NaBH4 in an aqueous solution. Moreover, the prepared catalyst was simply separated and reused.

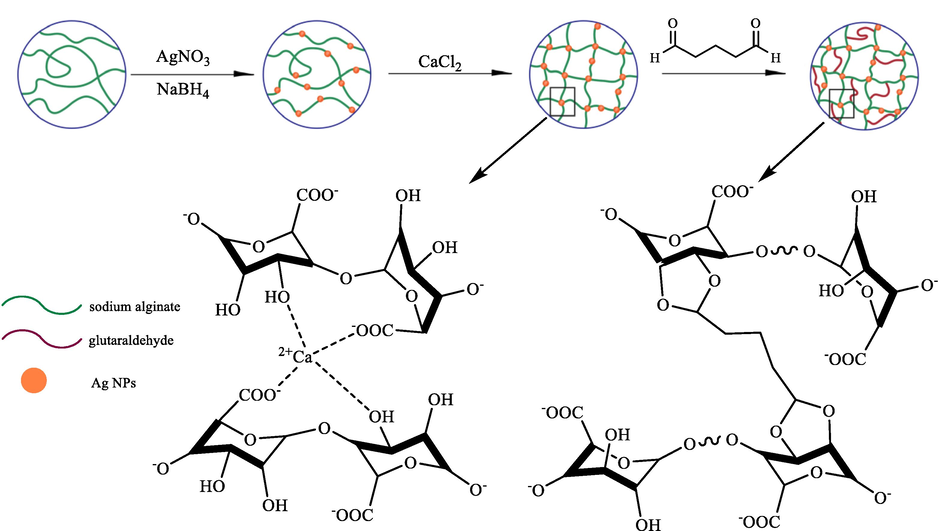

Xiao et al. (2014) proposed an economic and simple manner to prepare a segregative and stabilized heterogeneous catalyst through glutaraldehyde as the crosslinking agent, silver nanoparticles as the active component, and alginate as the stabilizer (Fig. 1) (Huang et al., 2014). Decent prowess was demonstrated by the Ag nanoparticle-loaded glutaraldehyde-crosslinked calcium alginate (Ag/CA@GTA) separable catalyst in the 4-NP degradation as a toxic environmental pollutant within the sodium borohydride in aqueous media. This manner included considerable features like an easy operation without the use of dangerous reagents, straightforward work-up, cost-effective and high yields.

The synthesis of the Ag/CA@GTA hydrogel beads.

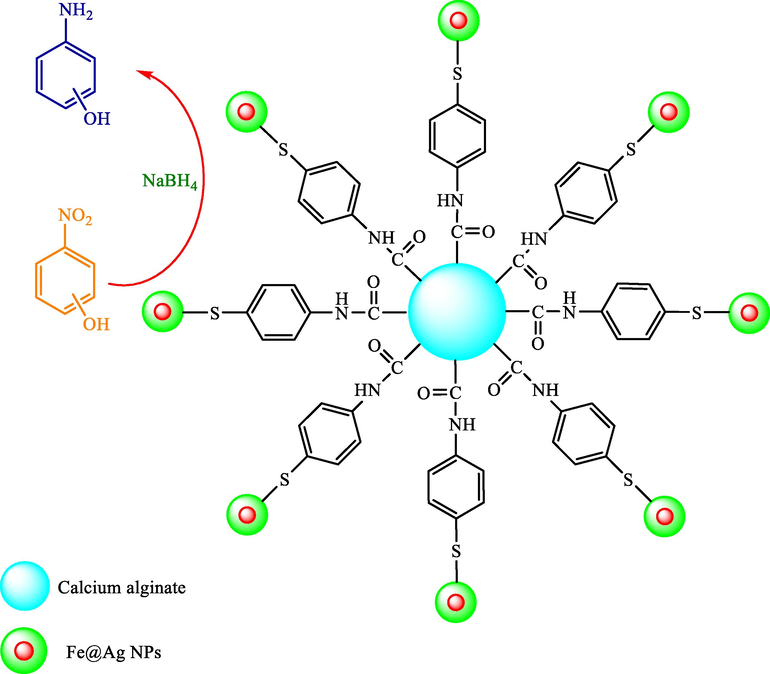

In the same year, a new highly recyclable and efficient catalyst was synthesized by Gupta et al. based on Ag@Fe bimetallic NPs including paminothiophenol (ATP) functionalized calcium alginate (Ag@Fe-ATP-CA) beads (Scheme 3) (Gupta et al., 2014). To perform catalytic features of 2-NP and 4-NP, Ag@Fe-ATP-CA catalyst was prepared while existing NaBH4. They also investigated the impacts of different variables like the concentration of NaBH4, the catalyst dosage, as well as temperature. The catalytic reduction rates of 2-NP and 4-NP compounds were found as the sequence: 4-nitrophenol > 2-nitrophenol.

A possible mechanism for the NP compounds’ catalytic degradation with recyclable Fe@Ag-ATP-CA catalyst.

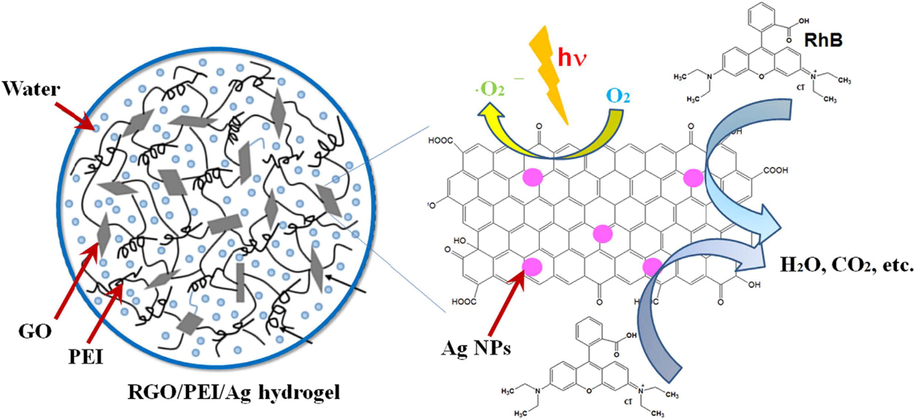

In 2015, new reduced graphene oxide-based Ag NPs-comprising composite hydrogels were prepared successfully by the Li research group via the simultaneous reduction of noble metal precursors and GO within the GO gel matrix (Jiao et al., 2015). The hydrogels created formerly included a network structure of crosslinked nanosheets. Their technique was oriented by the in situ co-degradation of Ag (CH3CO2) and GO within the hydrogel matrix to create reduced graphene oxide (RGO) based composite gel. Ag NPs were also simultaneously stabilized within the gel composite system. It was found that as-formed Ag NPs were uniformly and homogeneously dispersed on the RGO nanosheets’ surface within the composite gel. The catalytic prowess of the resultant RGO-based Ag NPs comprising composite hydrogel matrix was also assessed in the reduction of MB and Rhodamine B (Fig. 2).

The catalytic reduction of RGO/PEI/silver gel on dye solution. Reproduced with permission from ref. (Jiao et al., 2015).

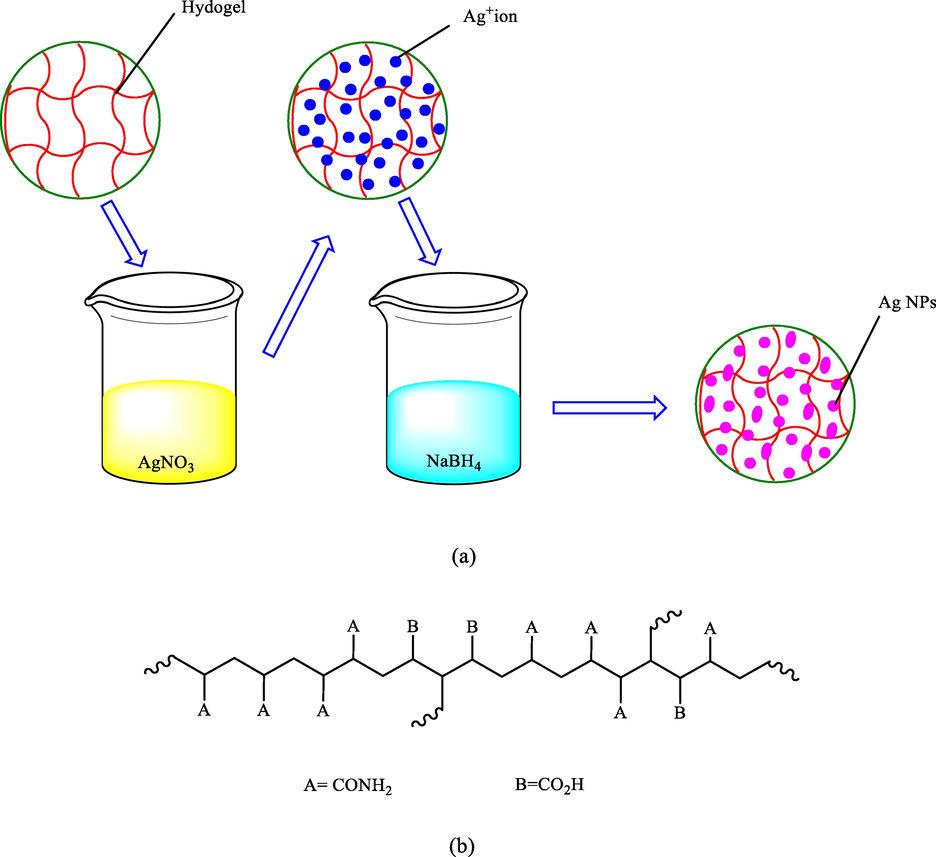

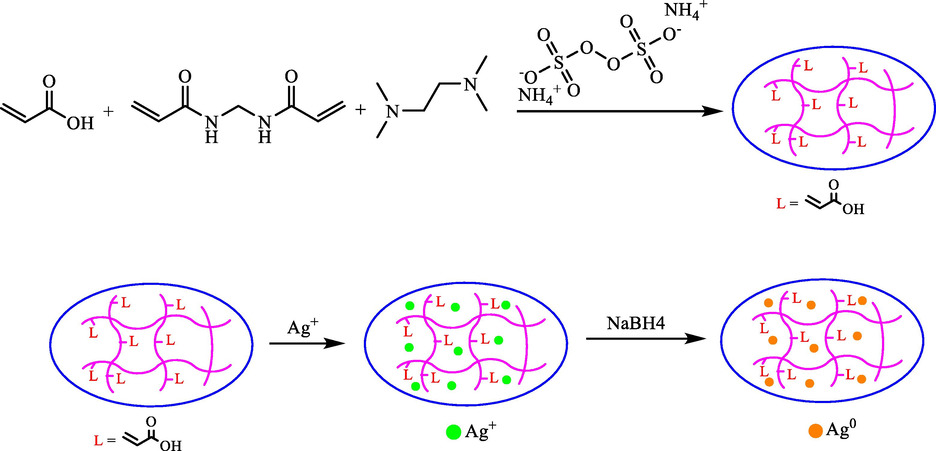

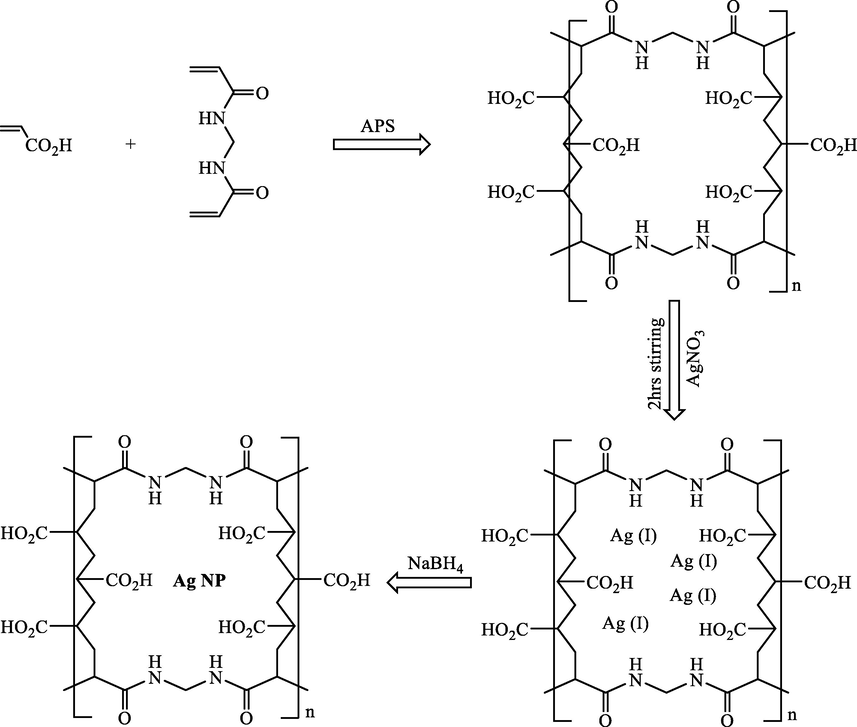

In the same year, a simple procedure was reported by Gao et al. for the in-situ synthesizing the catalytically active Ag NPs in hydrogel networks (He et al., 2015). By the electronegativity of the carboxyl and amide groups on the poly (acrylamide-co-acrylic acid) chains poly (AAm-co-AA), robust binding of the silver ions was achieved making the ions uniformly distributed inside the hydrogels. The silver ions on the polymer networks were reduced to Ag NPs by immersing the silver-loaded hydrogels in sodium borohydride solution (Scheme 4). Superior catalytic activity was demonstrated by the prepared hydrogel catalyst in reducing 4-NP via sodium borohydride.

(a) The formation of silver nanoparticles in the hydrogel network and (b) chain structure of the poly(AAm-co-AA).

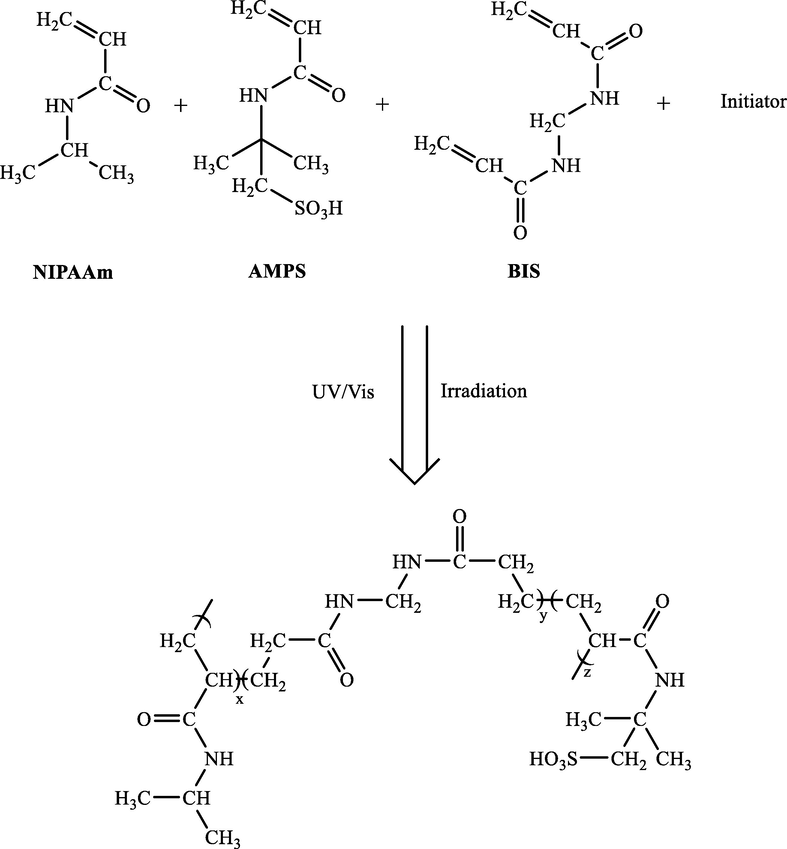

Wang and et al. also developed a simple and efficient method to prepare thermosensitive poly(NIPAAm-co-AMPS) hydrogels via copolymerizing 2-acrylamido-2-methyl 1-propane sulfonic acid (AMPS) and N-isopropyl acrylamide (NIPAAm) using N, N′-methylene bis (acrylamide) (BIS) as a cross linker (Scheme 5) (Wang et al., 2016). To obtain uniformly distributed Ag NPs within hydrogel networks as nanoreactors by in situ reductions of silver nitrate, sodium borohydride was applied as a reducing agent. The catalytic performance of Ag-NPs-poly (NIPAAm-co-AMPS) as a versatile nanocatalyst was studied for reducing 4-NP in an aqueous solution.

The preparation of NIPAAm-co-AMPS hydrogel.

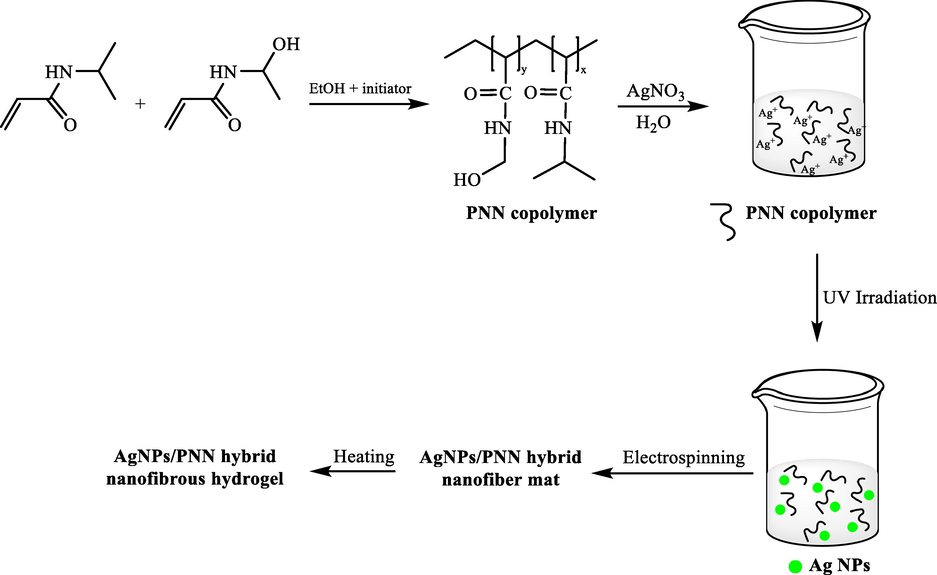

Ag NPs loaded thermoresponsive nanofibrous hydrogel were made with Zha et al. (2017) with electrospinning the aqueous solution comprising the metal NPs and poly ((N-isopropyl acrylamide)–co-(N-hydroxymethyl acrylamide)) copolymer (PNN copolymer), after heat treatment (Scheme 6) (Wang et al., 2017). Negative effects of the stabilizer or the residual reductant were avoided on their performances for the synthesis of the silver nanoparticles < 5 nm size by reducing silver ions in the spinning solution through UV irradiation. The high catalytic prowess was represented by the prepared AgNPs/PNN hybrid nanofibrous hydrogel in the reduction of 4NP to 4-AP via sodium borohydride. Moreover, the aforementioned nanocatalysts can be recycled simply from the reaction mixture at least 4 times with no considerable catalytic activity loss.

The synthesis of AgNPS-PNN hybrid nanofibrous hydrogel.

Ghorbanloo et al. presented a simple model for polyacrylic acid p(AA) hydrogels through radical polymerization. Then, using the p(AA) hydrogels as templates for in situ preparation of Ag NPs, p(AA)‐Ag composites were prepared (Scheme 7) (Ghorbanloo et al., 2018). The catalytic activity was displayed with the synthesized composites in the degradation of 4-NP to 4-AP, as well as oxidation of primary alcohols under the green process. This protocol has considerable benefits including easy separation of the catalyst, high yields, short reaction time, and relatively low temperature.

Schematic presentation of p(AA) preparation and synthesis of Ag NPs within p(AA) hydrogels.

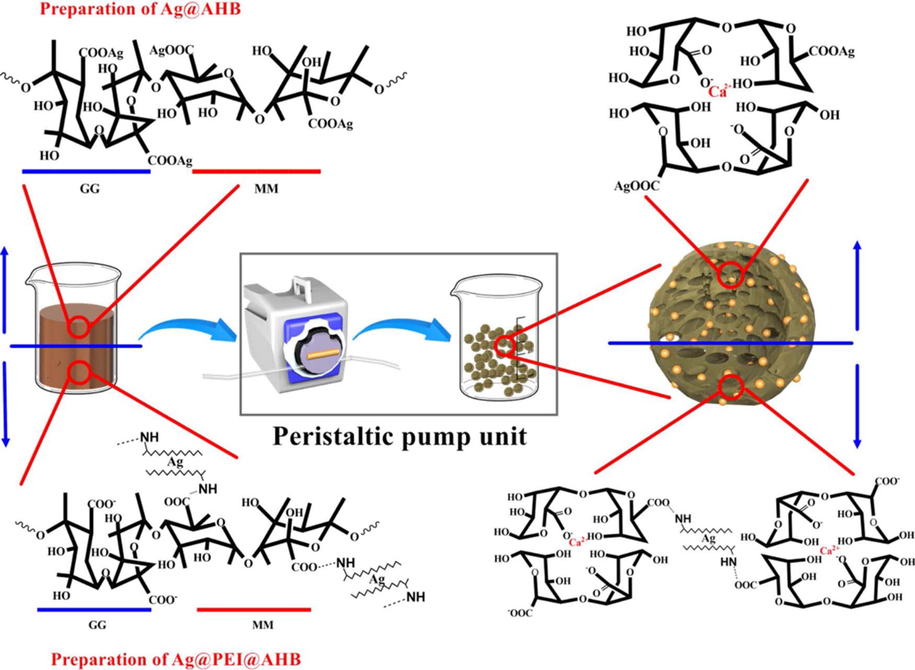

A simple and facile method was designed by Zhai et al. (2017) to synthesize 3D silver/ polyethylene imine/ alginate hydrogel beads (Ag@PEI@AHB) (Fig. 3) (Gao et al., 2018). Using polyethylene imine, the growth of nano-silver particles was reduced and limited. Good Ag NPs dispersion was achieved using an alginate microsphere as the catalyst carrier. They investigated the catalytic performance of Ag@PEI@AHB in the 4-NP-4-AP reduction. Moreover, the Ag@PEI@AHB could be reutilized 10 times with no catalytic activity loss.

The rough flowchart to prepare composite silver-alginate hydrogel beads. Reproduced with permission from ref. (Gao et al., 2018).

Tang et al. (2018) used a simple two-step route to synthesize a cellulose hydrogel containing cube-like Ag@AgCl (Tang et al., 2018). The cross-linker of the cellulose hydrogel served as the Cl source during the reaction process. Furthermore, the hydrogel network had a key role in controlling Ag@AgCl particles morphology. This synthesis process required no additional templates, surfactants, special equipment, or reducing agents. They used Ag@AgCl particles as a highly recyclable and efficient catalyst in reducing methyl orange (MO) under visible light irradiation.

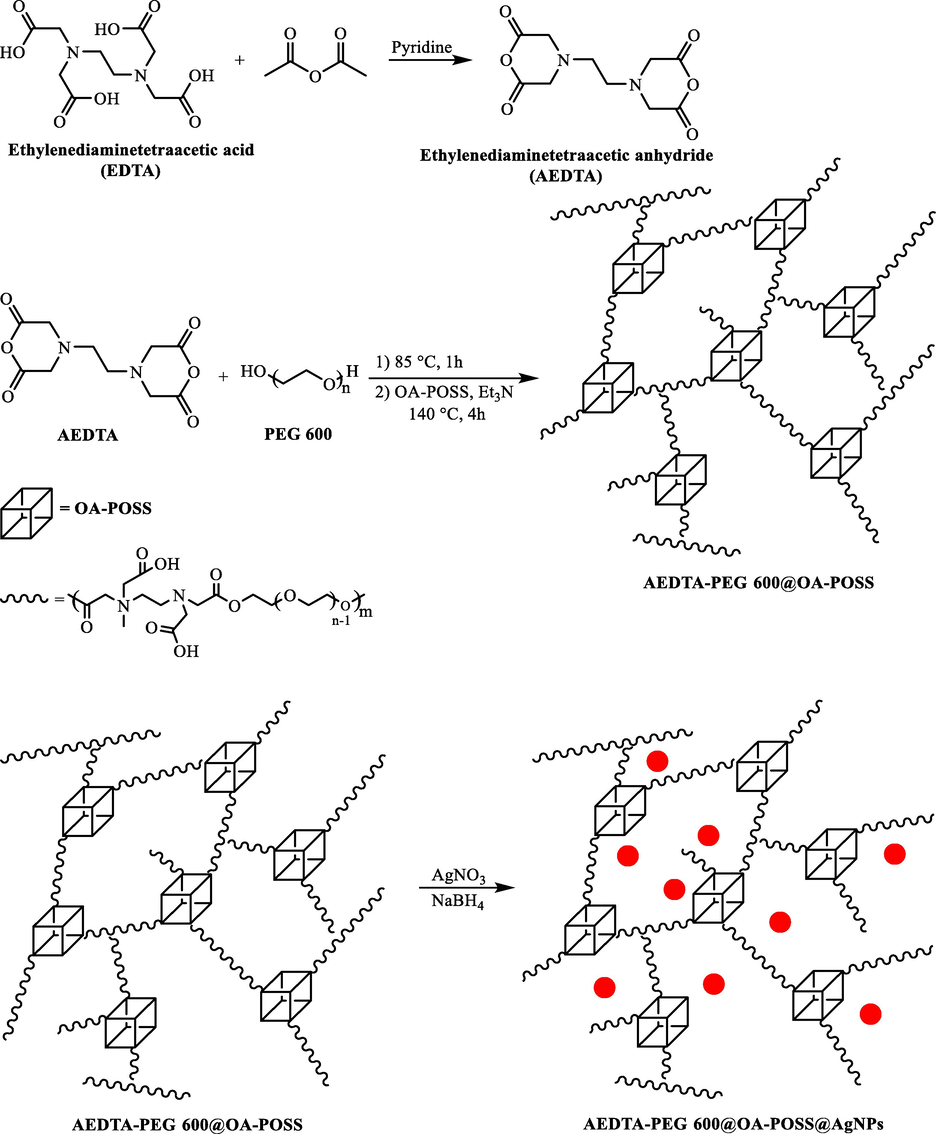

Ag NPs supported on polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (OA‐POSS) nanocrosslinked poly (ethylene glycol)‐based hydrogels (PEG600‐POSS/Ag NPs) was synthesized for the first time by Arsalani et al. (2018) as novel nanohybrid catalysts (Scheme 8) (Kazeminava et al., 2018). Excellent catalytic activity for reducing 4‐NP to 4‐AP was demonstrated by the prepared PEG600‐POSS/Ag NPs in water in the existence of borohydride at room temperature.

The preparation of AEDTA-PEG600@OA-POSS@AgNPs.

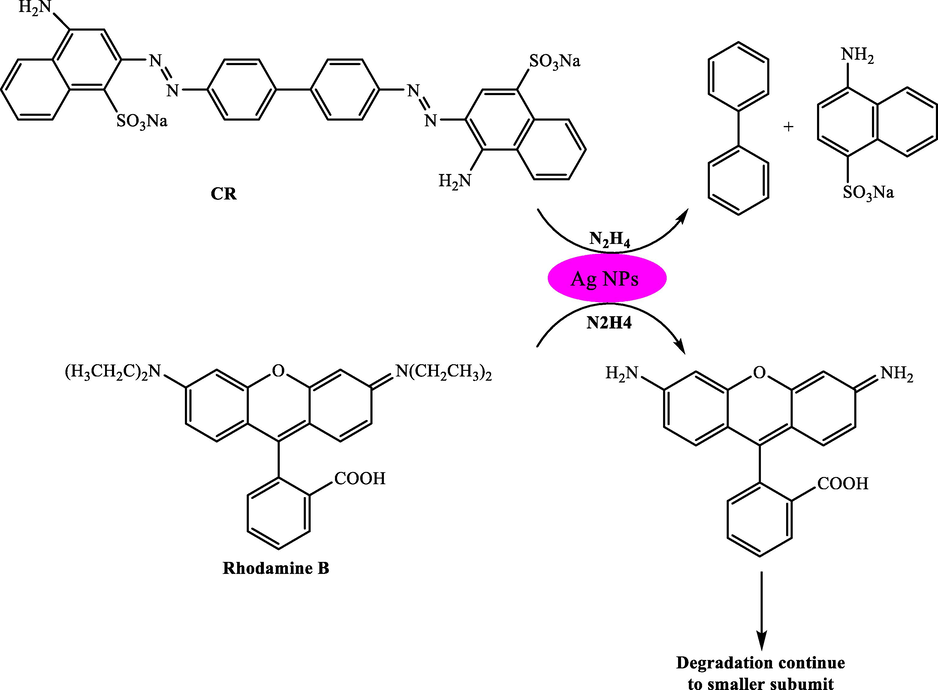

A simple technique was presented by Saruchi and Kumar (2019), to synthesize carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC)-based hydrogel with grafting of p(AA) chains while existing ammonium persulphate–N, N-methylene bis acrylamide (MBA) as initiator cross-linker system (Saruchi, 2019). To biosynthesize Ag NPs, an aqueous extract of Diospyros discolor leaves extract and polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was used and imbibed in the hydrogel. The created CMC-silver nanoparticles hydrogel was used in the reduction of Congo red (CR) and rhodamine B dyes. CR and Rhodamine B dyes had the degradation of 5 and 14 times quicker compared to the hydrazine (Scheme 9).

Degradation of CR and rhodamine B in the presence of hydrazine and silver nanoparticles.

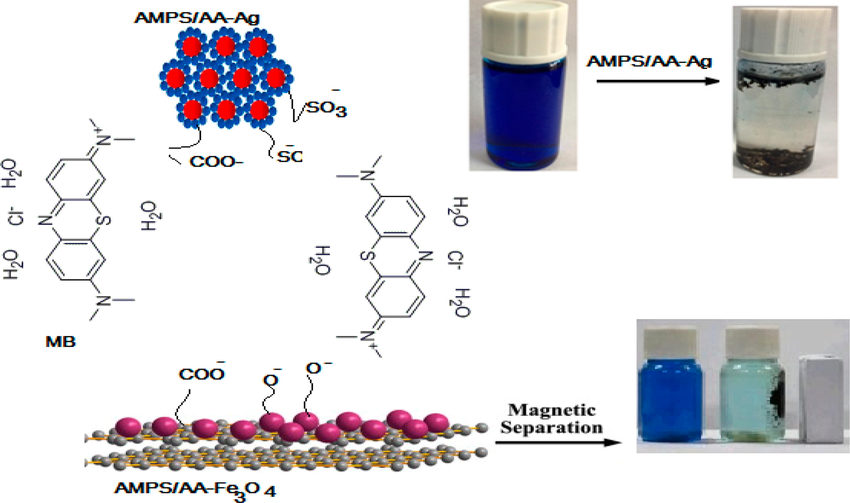

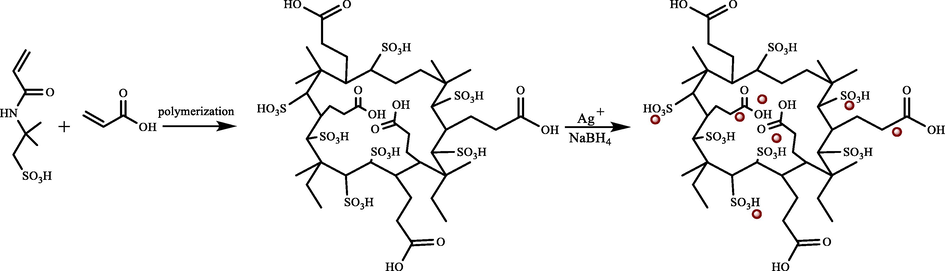

Atta et al. provided a simple method (2019) to synthesize ionic crosslinked 2-acrylamido-2-methyl propane sulfonic acid-co-acrylic acid hydrogel (AMPS/AA). Using an in situ technique, they synthesized AMPS/AA and its silver (AMPS/AA-Ag) and Fe3O4 (AMPS/AA-Fe3O4) composites (Atta et al., 2019). Potential catalytic performance was represented by the synthesized AMPS/AA-Ag and AMPS/AA-Fe3O4 composites to remove MB (Fig. 4).

The MB adsorption mechanism utilizing AMPS/AA composites. Reproduced with permission from ref. (Atta et al., 2019).

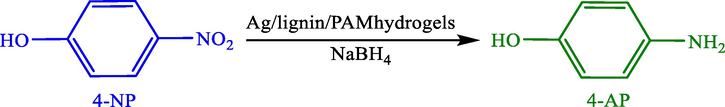

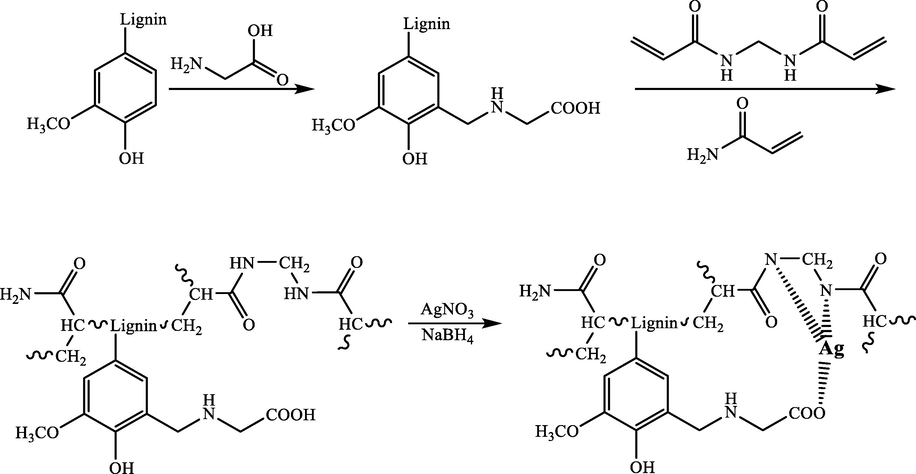

Zhai et al. (2019) synthesized three-dimensional silver/lignin/polyacrylamide hydrogels (Ag/lignin/PAM) successfully through a rapid and convenient assembly procedure (Gao et al., 2019). The excellent catalytic prowess was displayed by Ag/lignin/PAM hydrogels in the reduction of 4-NP. They found that silver ions can homogeneously disperse by abundant amino groups in the catalyst carrier while limiting the growth of Ag NPs in the reduction procedure with NaBH4 (Scheme 10). The catalytic process was accomplished in about 5 min utilizing this catalyst at room temperature. Without considerable loss in catalytic activity, they could reuse catalyst 10 times.

Reduction of 4-NP in the attendance of Ag/lignin/PAMhydrogels.

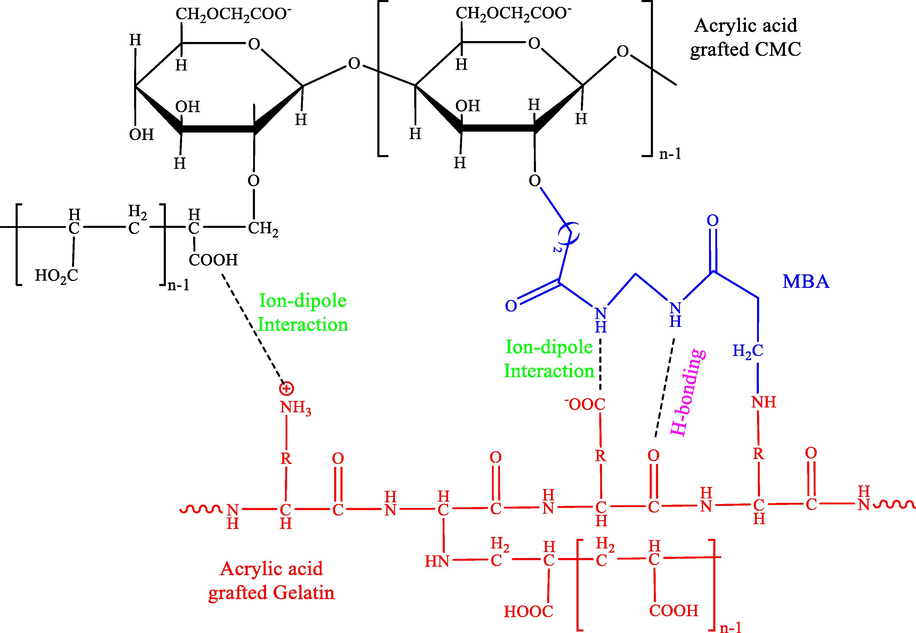

Kumar et al. also reported a facile route to synthesize Ag-doped hybrid hydrogel of gelatin and carboxymethyl cellulose by grafting of p(AA) (CGH-Ag) chains while existing ammonium persulphate as initiator and MBA as cross-linker in the aqueous medium through microwave irradiation technique (Scheme 11) (Sethi et al., 2019). They found the good activity of the CGH-Ag NPs in the reduction of rhodamine B and CR.

The diagram of cross-linked CMC and gelatin grafted p(AA).

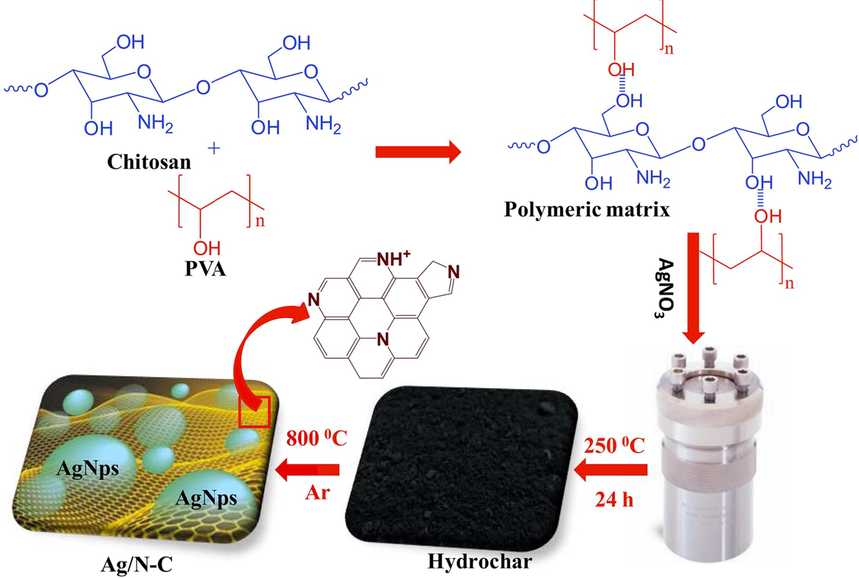

In 2019, a simple procedure was reported by Alshehri’s group to fabricate Ag NPs into the N-doped carbon matrix with a strong coupling interface and uniform dispersion. This is one of the main policies to enhance the catalytic activity of the nanocomposite (Alhokbany et al., 173 (2019)). To fabricate highly porous Ag NPs embedded into the N-doped carbon (Ag/N–C) nanocomposite, the chitosan-based hydrogel was used (Fig. 5). Under visible light, the prepared Ag/N–C nanocomposite was used to reduce 4-NP to 4-AP. According to their results, 98% of 4-NP was successfully reduced to 4-AP within 40 min suggesting an active catalyst.

The preparation manners for Ag/N–C and hydrochar nanocomposite. Reproduced with permission from ref. (Alhokbany et al., 173 (2019).).

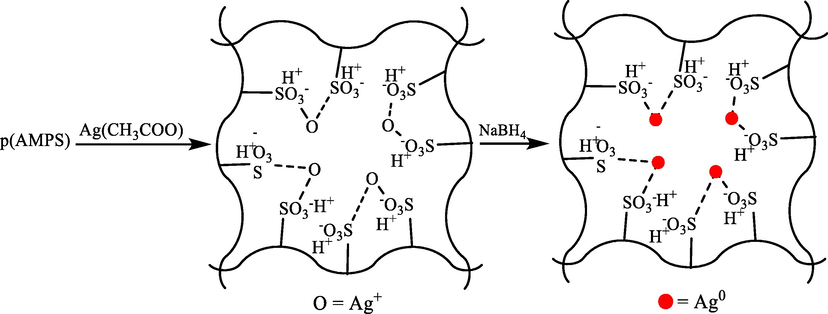

Poly(2-acrylamido-2-methyl-1-propane sulfonic acid) (p(AMPS)) hydrogels were prepared with Ghorbanloo and Nazari (2019) through the free radical polymerization reaction method under soft reaction circumstances (Ghorbanloo and Nazari, 2019). Using the prepared hydrogels as the template for in situ metal nanoparticles, silver acetate was also used in water (Scheme 12). This porous hydrogel composite was utilized to reduce 4-NP and H2 generation from hydrolysis of NaBH4. They determined activation energies, entropy, and enthalpy for 4-NP degradation and NaBH4 hydrolysis catalyzed via composite. Moreover, this composite was utilized as a catalyst in the aerobic oxidation of alcohols, they emphasized the impacts of various parameters like substituent effects and temperature.

The preparation of p(AMPS) composite.

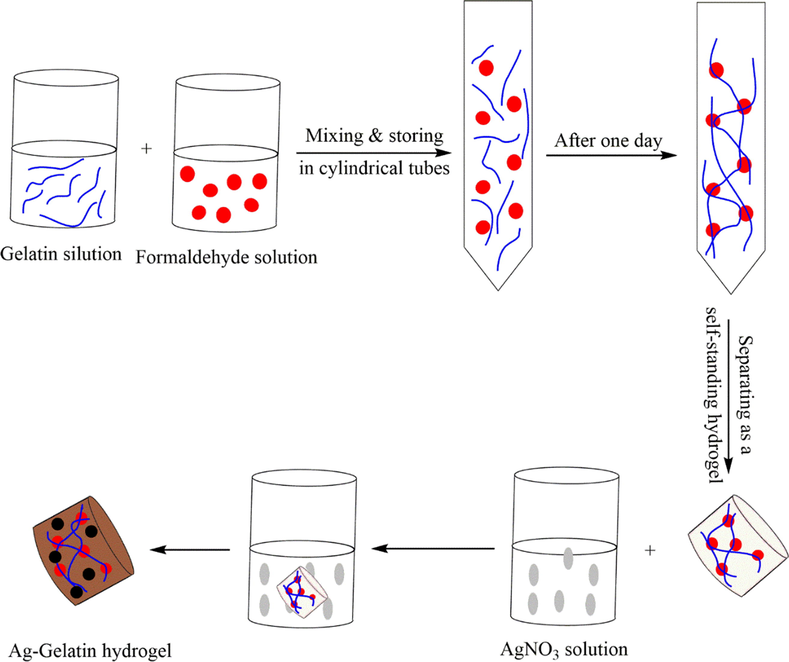

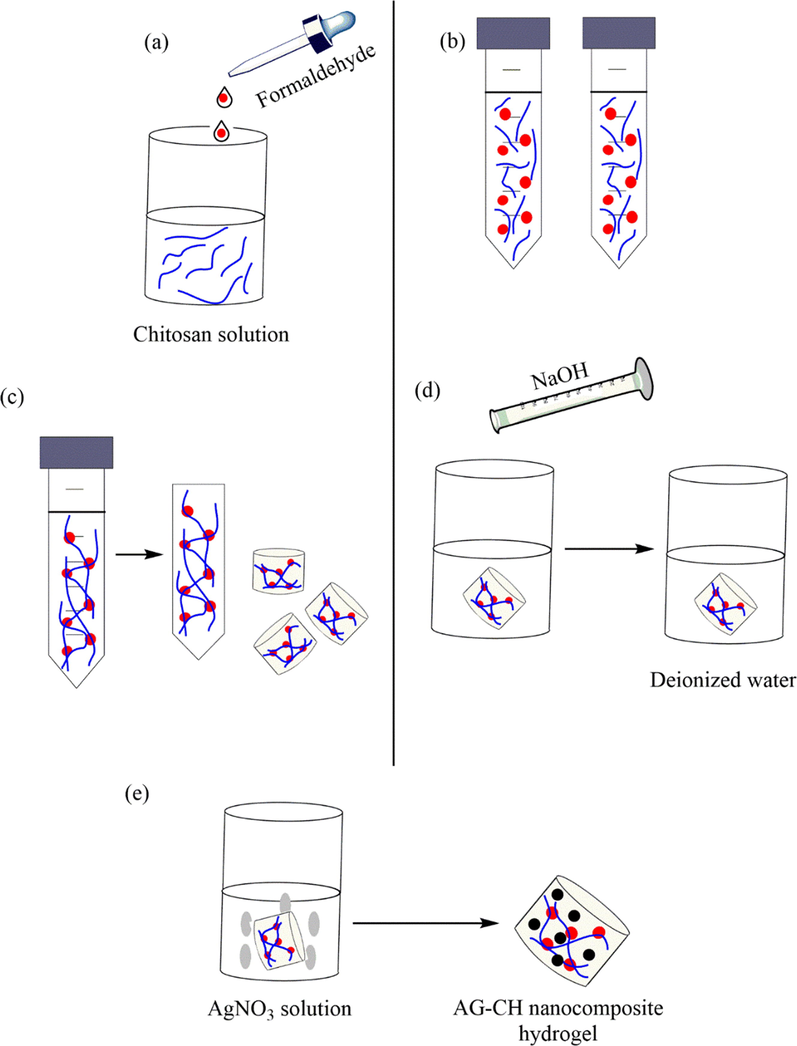

In 2019, a simple route was described by Kamal and teammates to self-synthesize of Ag NPs without using the reducing agents in a gelatin biopolymer hydrogel, which was used as a nanocatalyst for the degradation of the pollutants (Kamal et al., 2019). First, they prepared various wt% of the gelatin aqueous solutions at a higher temperature after CH2O solution cross-linking. They found that the 8% hydrogel was appropriate among the 3 various wt% of the gelatin hydrogels. For three days, the hydrogel was submerged in a 10 mM AgNO3 aqueous solution, then, the color change was found in gelatin hydrogel from transparent to brown color, which indicated the self-formation of the Ag NPs within the gelatin hydrogel (Ag-GL) (Fig. 6). They investigate the synthesized catalytic performance of Ag-GL to reduce MO and 4-NP.

The preparation of the Ag-Gelatin hydrogel.

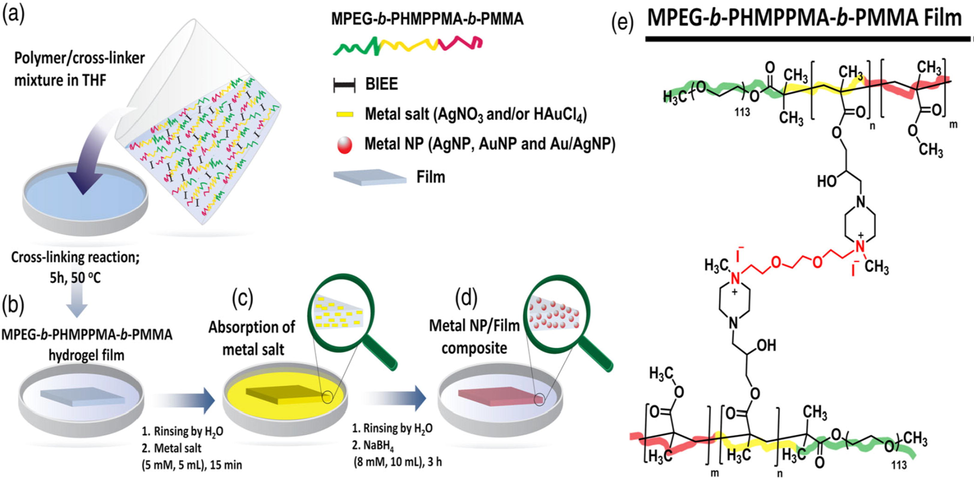

Kocak presented a simple technique to synthesize metal-NP-modified glycidyl methacrylate (GMA)-based hydrogel film composites. In this work, their catalytic activities were assessed with reduction 4-NP to 4-AP with NaBH4 (Fig. 7) (Kocak, 2019). Synthesizing poly (ethylene glycol) methyl ether-block-poly (glycidyl methacrylate)-block-poly (methyl methacrylate) (MPEG-b-PGMA-b-PMMA) triblock copolymer was performed through atom transfer radical polymerization. To open the epoxy ring of the PGMA blocks, 1-methyl piperazine was added. Using the resultant bi-functional polymer comprising 2-hydroxy-3-methyl piperazinepropyl methacrylate units, novel cross-linked hydrogel films were synthesized with quaternizing the tertiary amine (methyl piperazine) by 1, 2-bis (2-iodoethoxy) ethane. Using the prepared MPEG-b-PHMPPMA-b-PMMA hydrogel film as an immobilization matrix, monometallic Au and Ag and bimetallic alloy Ag/Au NPs were formed. The excellent catalytic activity was demonstrated by the prepared hydrogel film composites in the 4-NP-4-AP reduction.

(a) Preparing polymer/cross-linker mixture in tetrahydrofuran; (b) preparing polymer film and rinsing by H2O; (c) absorption of metal salt and rinsing with H2O; (d) adding the reducing agent (NaBH4), in situ generations of metal-nanoparticles inside hydrogel film; (e) Creation of cross-linked hydrogel film from PHMPPMA-based triblock co-polymer. Reproduced with permission from ref. (Kocak, 2019).

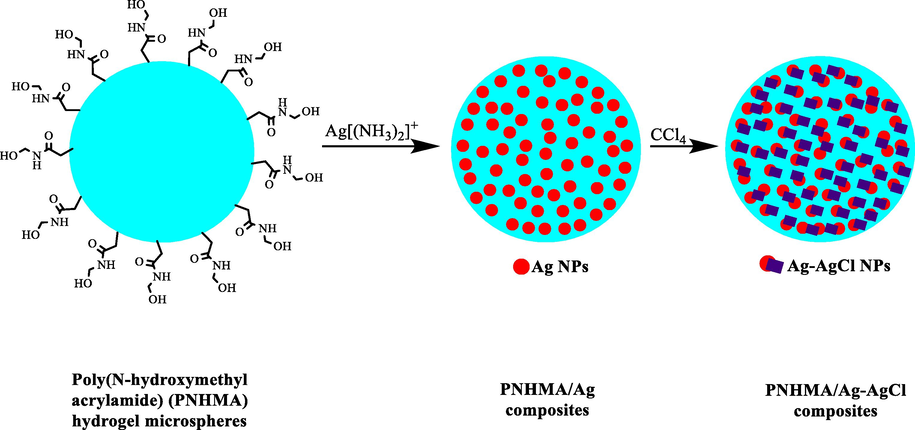

Photo catalytic redox reactions are very suitable approach to degrade organic pollutants especially organic dyes (Chen et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2018). These reactions usually need a semiconductor structure (Wang et al., 2018). In an study Zhang et al. (2019) made and used PNHMA/Ag (PNHMA = poly(N-hydroxymethyl acrylamide) and PNHMA/Ag-AgCl to degrade MO photo catalytically (Scheme 13) (Zou et al., 2019). They used PNHMA hydrogel microspheres because of hydroxyl groups as a template for Ag NPs aggregation inhibitor and Ag nanocatalysts loading. Using ethylene glycol as solvent and reductant, Ag ions were reduced. To perform the controllable transformation of Ag NPs to the Ag-AgCl composite particles, CCl4 was used. Changing the number of CCl4 within the preparation process, different PNHMA/Ag-AgCl composites were formed by various quantities of AgCl and Ag. This ratio highly affected the MO photocatalytic discoloration. The reduction efficiency was obtained as 18.8% for MO without PNHMA. However, it was 78% utilizing this polymer and in PNHMA/Ag-AgCl catalysts in the optimal conditions.

The preparation of PNHMA/Ag-AgCl composite.

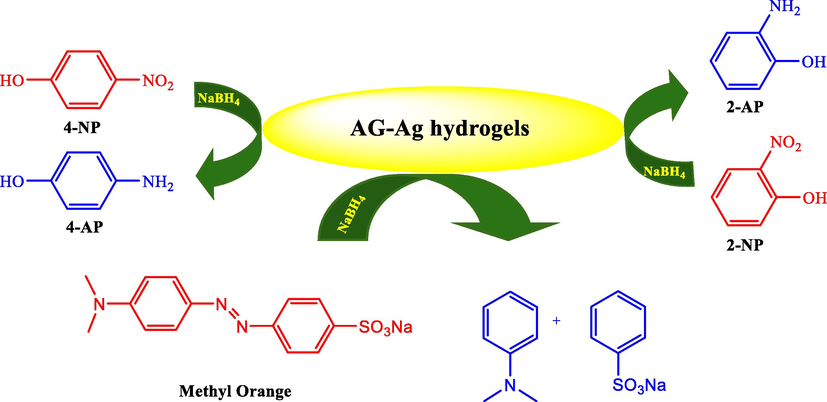

Farooq and co-workers prepared hydrogels of Acacia gum (AG) in the reverse micelle core of sodium bis (2-Ethylhexyl) sulfosuccinate (AOT) in a gasoline medium (Ihsan et al., 2020). Using the as-prepared hydrogels as a template, Ag NPs were prepared in situ through the reduction mechanism of NaBH4. The catalytic activity was found by the synthesized GA-Ag hydrogels in the reduction of MO and 2-NP, as well as 4-NP in an aqueous medium (Scheme 14). Considerably, 1000 mg/L of AG–Ag hydrogels with reduced 4-NP and 2-NP were also achieved into its counterparts, 4-AP and 2-AP in 24 min and 15 min, respectively at room temperature. Likewise, MO was completely reduced by 1000 mg/L of AG–Ag hydrogels within 25 min.

Reduction of 2-NP, 4-NP and MO by AG-Ag hydrogels.

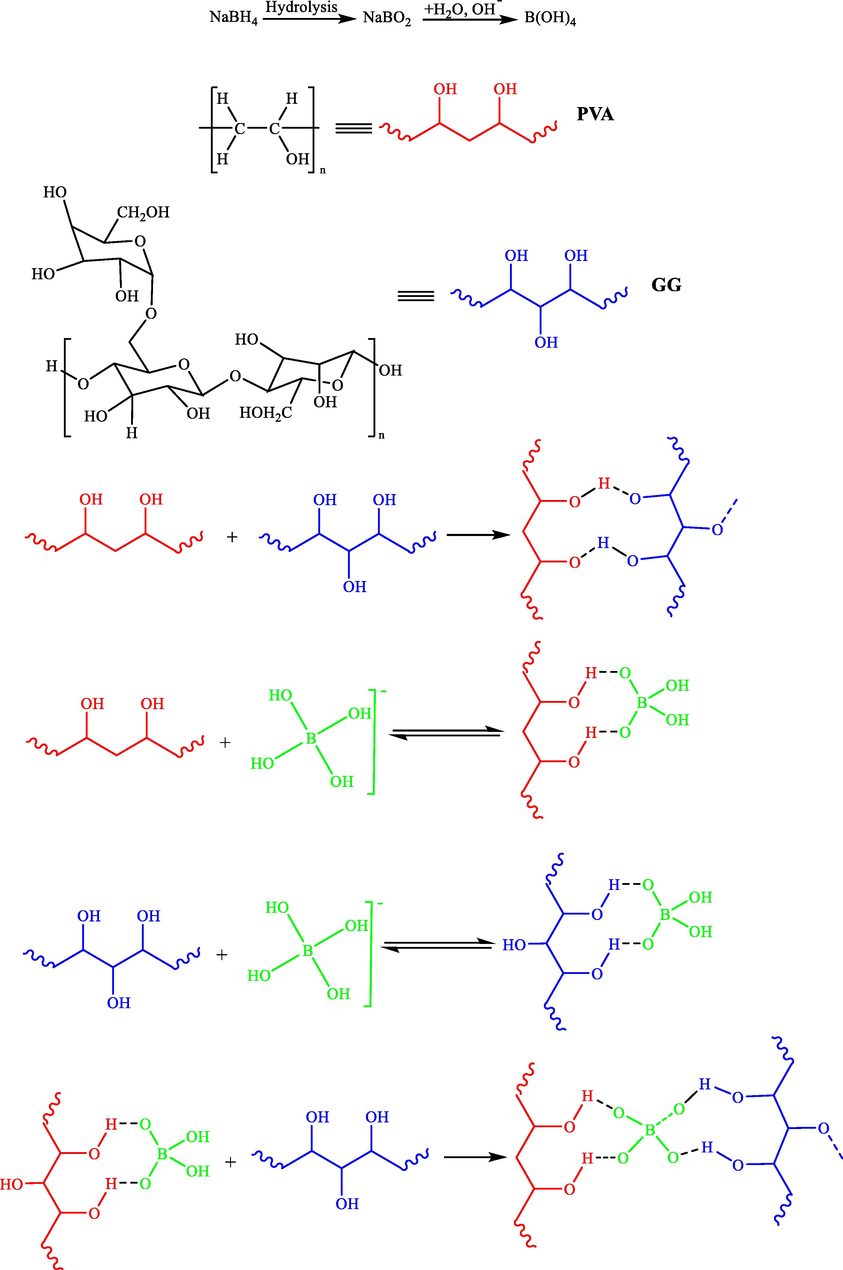

Sarmah et al. (2020) reported an efficient and rapid preparation of Ag NPs comprising polyvinyl alcohol- guar gum (PVA-GG) smart hydrogel composite. They found pH-based swelling and improved mechanical strength (Scheme 15) (Deka et al., 2020). They prepared the Ag NPs in situ in the PVA-GG hydrogel from different concentrations of the silver nitrate precursor solution using sodium borohydride. Uniform dispersed stable Ag NPs were obtained (90 days) of 10–20 nm in PVA-GG hydrogel. Good catalytic activity was displayed by PVA-GG-Ag NPs hydrogel while reducing nitrobenzene to aniline.

A probable mechanism of cross linking of polyvinyl alcohol, guar gum, and borate ions in the hydrogels.

The preparation of a new stable catalyst was reported by Farooqi et al. via loading the Ag NPs inside poly-(N-isopropylmethacrylamide-comethacrylicacid) [p(NMA)] microgels (Fig. 8) (Iqbal et al., 2020). They studied the resulting hybrid microgel [p(NMA)] to reduce MO, CR, and alizarin yellow (AY) catalytically in alkaline media. They examined the effects of different factors, such as dye concentration, stabilizing system, and shape and size of Ag NPs on the Ag-p(NMA) catalytic activity. The degradation reaction was investigated through UV spectra, within 16, 6, and 22 min for CR, MO, and AY, respectively. The best efficiency was represented by the prepared catalyst for MO in comparison to other dyes. Moreover, simultaneous reduction of AY, MO, and CR was assessed in one mixed solution of three dyes. Therefore, solution discoloration revealed the capability of catalyst for industrial wastewater treatment after 34 min.

The catalytic degradation of azo dyes by sodium borohydride utilizing Ag-p(NMA) hybrid microgels as a catalyst in water. Reproduced with permission from ref. (Iqbal et al., 2020).

Ghorbanloo and Fallah (2020) reported a simple technique to prepare poly(2-acrylamido-2-methyl-1-propane sulfonic acid-co-acrylic acid), p(AMPS-c-AA), embedded by Ag NPs (Scheme 16) (Ghorbanloo and Nosrati Fallah, 2020). They used the free radical polymerization reaction technique to prepare hydrogels from 2-acrylamido-2-methyl-1-propane sulfonic acid (AMPS) and acrylic acid (AA) monomers in the mild reaction condition. They made Ag NPs within hydrogel with reducing silver (I) ions utilizing NaBH4 as a reducing agent. The performance of the hydrogel was assessed in 4-NP reduction to 4-AP.

The preparation of p(AMPS-c-AA) composite.

A simple procedure was presented by Kamal et al. (2020) for the self-synthesis of Ag NPs in chitosan (CH) biopolymer hydrogels in the nonexistence of a reducing agent (Khan et al., 2020). They dissolved and crosslinked different quantities of CH powder in acidic aqueous solutions using the CH2O solution and made a CH biopolymer hydrogel. A CH hydrogel was made from a dense solution as a result of good mechanical stability. To self-synthesize Ag NPs inside hydrogel, immersing in an aqueous solution of silver nitrate (10 mM) was considered at room temperature for 3 days. A color change was found for the CH hydrogel to brown from transparent indicating the successful creation of Ag NPs over CH hydrogel (Ag-CH) (Fig. 9). The Ag-CH was examined as a catalyst in the 2-NP reduction reactions and acridine orange.

The preparation of Ag-CH hydrogel.

Ajmal et al. developed a facile and effective technique to synthesize poly (acrylic acid) hydrogel microparticles (PAAHMPs). They fabricated Ag NPs inside the prepared structure of PAAHMP (Scheme 17) (Ajmal et al., 2020). The PAAHMPs were made by inverse suspension polymerization method to fabricate Ag NPs via chemical reduction technique utilizing NaBH4 as reducing agent. The desirable catalytic activity was displayed by the synthesized PAAHMPs/Ag NPs composite to reduce nitro aromatic pollutants and an industrial dye, as, 4-NP, 2-NP, and MO.

The synthesis of PAAHMPs/Ag NPs.

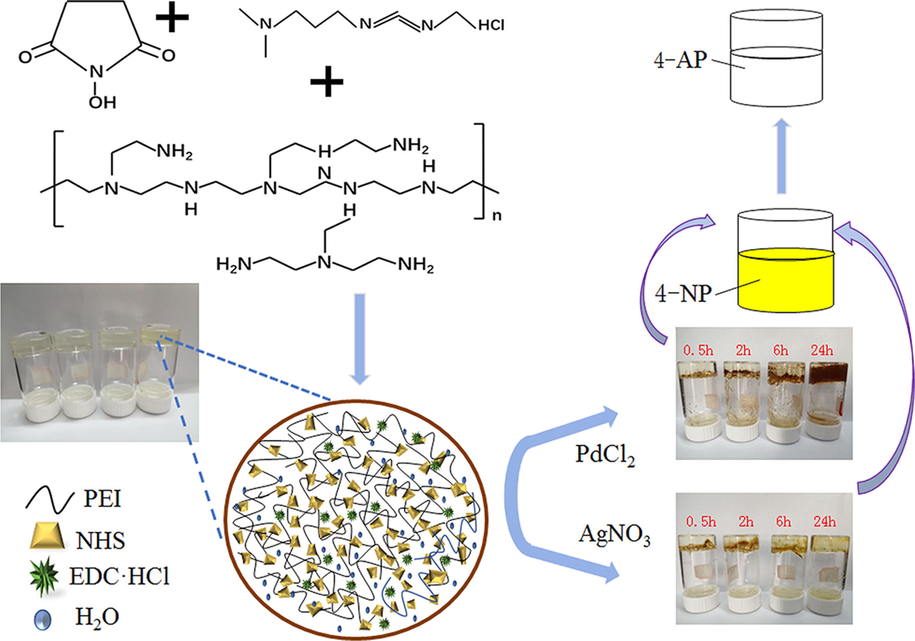

In 2020, PEI-Pd and PEI-Ag composite hydrogels were successfully synthesized by Jiao et al. through a facile and convenient route (Feng et al., 2020). The extraordinary and durable activity was found for the prepared PEI-Pd and PEI-Ag to reduce 4-NP to 4-AP in an environmentally-friendly medium (Fig. 10). This process includes advantages of the high effectiveness of the composite hydrogels, simple preparation, and easy workup.

Preparation and catalytic procedure of PEI-Ag/PEI-Pd composites and PEI hydrogel. Reproduced with permission from ref. (Feng et al., 2020).

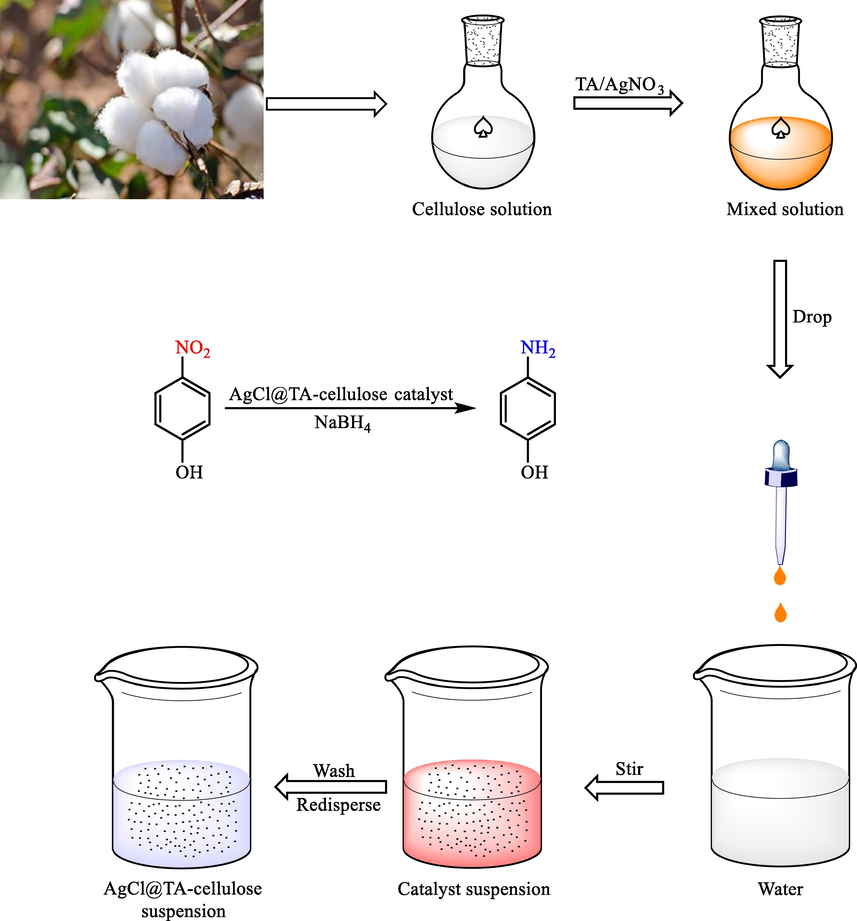

Some tannic acid (TA) modified cellulose hydrogels embedded size controlled AgCl NPs (AgCl@TAx-cellulose hydrogels) were synthesized by (Zhang et al., 2021) using a one-step technique (Zhang et al., 2021). The significant catalytic activity was displayed by the prepared AgCl@TAx-cellulose hydrogels to reduce 4-NP and degrade organic dyes by NaBH4 (Scheme 18).

The preparation of AgCl@TAx-cellulose hydrogels.

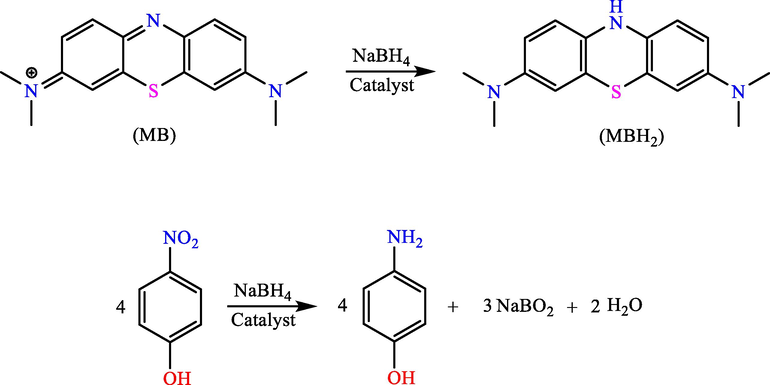

In the same year, poly (methacrylic acid) [p(MAAc] hydrogels were prepared by Naeem et al. with a facile and efficient free radical polymerization process. They prepared Ag, Co, and their bimetallic nanoparticles utilizing p(MAAc) as a template (Naeem et al., 2021). Cobalt (II) and silver (I) ions were loaded with p(MAAc) hydrogels from their equivalent aqueous salt solutions. Then, these metal ions-loaded hydrogels were treated by NaBH4, which is a reducing agent to achieve corresponding metal nanoparticles into the hydrogel network. Some harmful organic residual dyes were degraded such as MO using the prepared p(MAAc)-metal hydrogel composites as catalysts. Eosin Y was also degraded accompanied by reduction studies of some nitro aromatic compounds such as 4-nitroaniline, 2-NP 4-NP, to their particular amino phenolic compounds from contaminated water (Scheme 19).

Degradation and reduction of MB, Eosin Y and 4-NP, 2-NP by p(MAAc)-M catalyst.

Li et al. made nanoalloys in stable flexible electrospun hydrogel nanofibers comprising poly(allylamine hydrochloride) and polyacrylic acid (PAH/p(AA)) (Li Sip et al., 2021). Loading the hydrogel fibers with metal ions like Ag and Cu through immersion in metal salt solutions after a chemical reduction, the MNPs were formed. Absorbing the metal ions by the hydrogel matrix into the fibers. They presented a viscous environment for promoting the creation of alloy particles within the small diameter range (<25 nm). The reductions of MB and 4-NP were created for examining and comparing the catalytic activity of Ag-Cu bimetallic nanoparticles and monometallic nanoparticles (Scheme 20). The Ag-Cu bimetallic nanoparticles presented the preferred selectivity to reduce 4-NP and greater catalytic activity to degrade MB.

The chemical reduction of 4-NP and MB.

In the same year, a novel type of Ag NPs immobilized catalyst was synthesized by Zhai et al. based on glycine modified lignin hydrogels (Ag-GLH) by good catalytic activity to reduce p-NP (Gao et al., 2021). Using glycine, carboxy and amino groups were prepared to complex Ag ions, which was also simultaneously beneficial for the reduction and suppression of Ag NPs (Scheme 21). Through batch experiments of 4-NP hydrogenation, the catalytic performance was correlated. With only 101 s, the concentration of 4-NP of 5 mmol/L could be finished and the rate of k was obtained as 0.0151 s−1. After 10 cycles, the conversion rate was retained by the catalyst beyond 98%, and no obvious deterioration was found for the structure. The leaching of nanosilver can be neglected, which could be ascribed to the crucial contribution of the presented glycine component.

The preparation of Ag-GLH hydrogels.

Instances of using Ag-based hydrogel for environmental remediation are presented in Table 1.

Ag-based hydrogels

Size of Ag NPs (nm)

Application

Benefits

Year

Ref.

PVA/PS-PEGMA/Ag

35–45

active even

2007

(Lu et al., 2007)

Ag@Ahs

when the gels are dried and re-hydrated

CMS/Ag

8.3–16.6

Facile and eco-friendly preparation

2012

(Wu et al., 2012)

p(AAm)-CB composite hydrogel

20

Successfully catalyzing in 5 cycles

2013

(Sahiner et al., 2013)a

Ag@AHs

50–100

Uniform Ag NPs

2013

(Ai and Jiang, 2013)a

Ag/CA@GTA

5–20

Cost-effective and

eco-friendly2014

(Huang et al., 2014)a

Magnetically separable and

high loading of Ag NPs

Fe@Ag-ATP-CA

15–20

Fully renewable and eco-friendly

2014

(Gupta et al., 2014)a

Ag NP loaded poly(AAm-co-AA) hydrogels

Reduction

of

4-NP to 4-AP

20–50

Temperature dependence

2015

(He et al., 2015)a

α-cyclodextrin and poly(NIPAAm-co-AMPS) thermosensitive hydrogels

and catalytic efficiency

Ag/triton X-705/SiNPs

3.5

2016

(Wang et al., 2016)a

Ag-loaded Ca-ALG beads

Recyclable for 9 times

High loading of Ag NPs and catalytic efficiency

DNA-Ag-Hydrogel

200 nm-1 µm

Green organic synthesis as well as in vivo applications.

2016

(Bano et al., 2016)

10

Temperature dependence of catalytic efficiency

2016

(Wang et al., 2016)

AgNPs/PNN hybrid nanofibrous hydrogel

Recyclable for 10 times

Ag–CAHB

02-Mar

2016

(Zinchenko et al., 2016)

Short reaction time and

p(AA)‐Ag composite

relatively low temperature

Recyclable for 10 times with no catalytic activity loss

Ag@PEI@AHB

<5

2017

(Wang et al., 2017)a

High toughness and

Stability

20

2017

(Gao et al., 2017)

PEG600‐POSS/Ag NPs

Enhanced and tunable

20–40

catalytic activity

2018

(Ghorbanloo et al., 2018)a

PNIPAam-Ag or Au

Mechanically tough gel

03-May

2018

(Gao et al., 2018)a

Catalyzed process in about 5 min

Ag/NP-NC5-gel

Reuse catalyst 10 times

Ag/lignin/PAM hydrogels

Oct-30

Catalytic reduction under visible light at room temperature

2018

(Kazeminava et al., 2018)a

Ability to catalyze two simultaneous oxidation and reduction reactions

2

2018

(Gancheva et al., 2018)

Ag/N–C

Au and Ag bi-metallic catalyst

Reusable for 10 times

40–50

Reduction

2018

(Varade and Haraguchi, 2018)

of

Tunable catalytic activity under continuous flow

Ag based p(AMPS)

03-Jun

4-NP to 4-AP

2019

(Gao et al., 2019)a

composite

Ability to catalyze two simultaneous oxidation and reduction reactions

Simple preparation and easy workup

MPEG-b-PHMPPMA-b-PMMA composite film

13

2019

(Alhokbany et al., 173 (2019).)a

Catalytic reaction in only 123 s

Ag-PNIPAam

Reusable for 5 times

20

2019

(Ghorbanloo and Nazari, 2019)a

Catalysis along with reduction of Ag ions

p(AMPS-co-AA)

composite

4.9

Reusable for 10 times

2019

(Kocak, 2019)a

6.32

Temperature dependence of catalytic efficiency

PEI-Ag composite

2.4–5.9

Near-IR light-responsive

2019

(Gancheva and Virgilio, 2019)

Ag@LPAH-20

30

2020

(Ghorbanloo and Nosrati Fallah, 2020)a

Ag@HG xerogel

AgCl@TAx-cellulose hydrogels

–

2020

(Feng et al., 2020)a

Ag-GLH

03-Jun

2020

(Gao et al., 2020)

Ag@PS-PNIPAM

Reduction

Oct-30

of

2020

(Ganguly et al., 2020)

Ag/PDA@CNC

4-NP to 4-AP

>20

2021

(Zhang et al., 2021)a

06-Sep

2021

(Gao et al., 2021)a

2.4–5.6

2021

(Besold et al., 2021)

–

2021

(Liu et al., 2021)

RGO-based polyethylene imine hydrogel

60–70

High loading of Ag NPs and catalytic efficiency

2019

(Saruchi, 2019)a

Reduction of MB and rhodamine B

PAM-GO-Ag

Easy to handle and recover of catalyst

13

2021

(Sivaselvam et al., 2021)

Cellulose hydrogel containing cube-like Ag@AgCl

–

Synthesis with no need to additional templates and reducing agents

2018

(Tang et al., 2018)a

Catalyzing under visible light irradiation

High specific surface area

PNHMA/Ag-AgCl composite

Reduction of MO

350

2019

(Zou et al., 2019)a

CMC–p(AA)-based hydrogel

19–30

Reduction of CR and rhodamine B

Very fast reduction

2015

(Jiao et al., 2015)a

CGH-Ag NPs

Reduction of CR and rhodamine B

12.13

Improved mechanical and thermal properties

2019

(Sethi et al., 2019)a

DexCG-Ag nanocomposites

20–30

Good biocompatibility and biodegradability

2009

(Ma et al., 2009)

Reduction of MB

High MB adsorption and degradation

AMPS/AA-Ag

<100

High MB adsorption and degradation

2019

(Atta et al., 2019)a

AMPS/AAm-Ag

Can be isolated without filtration or centrifugation

–

2019

(Atta et al., 2019)

Low cost and enhanced catalytic activity

CS/AgCl/ZnO

Reduction of MB

20–40

2020

(Taghizadeh et al., 2020)

AgBr–ZnO/chitosan beads

27–50

2020

(Taghizadeh et al., 2020)

Ag-GL

43

Reduction of

High reaction rate

2019

(Kamal et al., 2019)a

MO and 4-NP

GA-Ag hydrogel

5–50 µm

Might be an effective catalyst at industrial level

2020

(Ihsan et al., 2020)a

High stability

PAAHMPs/Ag

04-Jul

Recyclable for 7 times

2020

(Ajmal et al., 2020)a

Selective catalyst

PAH/p(AA)-Ag-Cu

<25

2021

(Li Sip et al., 2021)a

PVA-GG hydrogel

Oct-20

Reduction nitrobenzene to aniline

Good antibacterial property

2020

(Deka et al., 2020)a

PVA-gel/AgNPs

6.7-19.2

Reduction of nitrobenzene to aniline

Reusable for six consecutive runs without significant loss of its activity

2019

(Quadrado et al., 2019)

Ag-p(NMA)

14

Reduction of CR, MO, and AY

Rapid and

2020

(Iqbal et al., 2020)a

economical degradation of dyes

Ag-CH hydrogel

11

Reduction of 4-NP and acridine orange

Enhanced immobilization of Ag NPs

2020

(Khan et al., 2020)a

p(MAAc)-Ag hydrogel

25–35

Reduction of Eosin Y and MO

Good catalytic activity

2021

(Naeem et al., 2021)a

in tap and dam water

PEOPPA-Ag

–

Reduction of

Easy separation of catalyst

2013

(Zhang et al., 2013)

nitro aromatics

PAM/graphene/Ag

60

Reduction of MB, 4-NP and MO

High loading of Ag NPs

2014

(Hu et al., 2014)

cl-AP/exf.LT-AgNPs

–

Ability to remove water-soluble organic pollutants and microbial contaminants

2017

(Sarkar et al., 2017)

AgI‐RGAs

25–30

Reduction of

Semi conductivity

2015

(Reddy et al., 2015)

Rhodamine B and 4-NP

Ag/F-127/SiNPs

20

Reduction of

Reusable for 10 times

2017

(Bano et al., 2017)

2-nitroaniline to

1, 2-benzenediamine

rGH-AgBr@RGO

500–600

Degradation of Bisphenol A

Synergy between photocatalytic and adsorption-based pollutant degradation

2017

(Chen et al., 2017)

AgNP@BC

8.1

Reduction of

Eco-friendly and scalable application

2018

(Yang et al., 2018)

Rhodamine 6G, MO and 4-NP

Ag- PAM/GO

10

Reduction of MB and 4-NP

The pseudo-zero-order kinetics for the first time

2020

(Hu et al., 2020)

Cu0/Alg-CNBs

-

Reduction of CR, MO, 4-NP, 2-NP and 2,6-DNP

Capable to use in the large scale

2020

(Khan et al., 2020)

HMC-Ag2O

20

Degradation of acid orange-8

Good photocatalytic activities and antibacterial properties

2019

(Li et al., 2019)

Hp(APTMACl)-Ag

-

Degradation of CR, MO, MB, NB and 4-NP

six times with 98% conversion of pollutants

2021

(Shah et al., 2021)

5 Conclusion and future prospects

For the development of industries in today's world, several pollutants have entered the environment imposing numerous risks to the environment and humans. These pollutants can be removed from the environment in different ways. Utilizing catalytic degradation or reduction, different organic pollutants, e.g., nitro compounds, hexavalent chromium, organic dyes, and medicinal compounds, can be removed from the environment including. This review summarized recent advances of Ag-based hydrogels employed as heterogeneous catalysts for the elimination of a wide variety of environmental pollutions. Despite outstanding improvements reported for Ag-based hydrogels, a few important aspects should be still focused on in the development of new hydrogels for the future catalytic environmental remediation. The new emerging synthetic methods of Ag-based hydrogel composites such as grafting hydrogel copolymers onto various support materials, are promising alternatives to the conventional silver containing hydrogels, due to their high mechanical strength. However, there is still much that can be done to further improve both physical and chemical properties of Ag-based hydrogels. More comprehensive stability studies under different operating conditions are required to validate the silver-incorporated hydrogels for industrial applications.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge partial support from the Research Council of Islamic Azad University, Qom Branch.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2018;108:1035-1044.

- Bioresour Technol.. 2013;132:374-377.

- Polym. Eng. Sci.. 2020;60:2918-2929.

- Heliyon. 2020;6:e04508

- Compos. B: Eng.. 2019;173

- J. Environ. Manage.. 2012;113:170-183.

- Ann. Rev. Nano Res. 2008:439-493.

- J. Ind. Eng. Chem.. 2015;27:347-353.

- J. Mater. Sci. Tech.. 2016;32:134-141.

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2019;131:682-690.

- Molecules. 2019;24

- Polymer Int.. 2019;68:1164-1177.

- New J. Chem.. 2016;40:6787-6795.

- J. Solid State Chem.. 2017;248:40-50.

- Environ. Chem. Lett.. 2009;7:191-204.

- Indus. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2021;60:3922-3935.

- Chem. An Asian J.. 2014;9:3451-3456.

- Europ. polym. J.. 2015;65:252-267.

- Int. Biodeterior. Biodegradation. 2008;62:96-103.

- Appl. Catal. B: Environment.. 2017;217:65-80.

- ACS Nano. 2019;13:295-304.

- Chem. Commun. (Camb). 2012;48:6663-6665.

- Applied Catalysis B: Environ.. 2019;244:546-558.

- J. Environ. Manage.. 2020;271:110962

- Carbohydr. Polym.. 2020;248:116786

- Chem. Eng. J.. 2021;404

- ACS Omega. 2020;5:3725-3733.

- Sci. Total. Environ.. 2021;765:142673

- Chem. Rev.. 2019;119:2611-2680.

- Appl. Sur. Sci.. 2019;473:578-588.

- Mater. Interfaces. 2018;10:21073-21078.

- Ultrason. Sonochem.. 2020;60:104797

- New J. Chem.. 2017;41:13327-13335.

- Chem. Soc. Rev.. 2017;46:2799-2823.

- Carbohyd. Polym.. 2018;181:744-751.

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2019;134:202-209.

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2020;144:947-953.

- Chem. Eng. J.. 2021;403:126370

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2019;132:784-794.

- J. Porous Mater.. 2019;27:37-47.

- Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2018;32:e3917

- Journal of Porous Materials. 2020;27:765-777.

- Adv. Res.. 2015;6:105-121.

- J. Mol. Liq.. 2014;190:133-138.

- Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2021;35

- Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:20234-20242.

- J. Alloys Compd.. 2016;689:625-631.

- Mater. Res. Bul.. 2015;70:263-271.

- J. Mater. Chem. A.. 2014;2:11319-11333.

- J. Mater. Chem. A.. 2015;3:11157-11182.

- Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2020;508

- RSC Adv.. 2014;4:60460-60466.

- Catal. Lett.. 2020;151:1212-1223.

- Ecotox. Environ. Saf.. 2020;202:110924

- Sci. Rep.. 2015;5:11873.

- Sci. Commun.. 2020;34

- J. Polym. Environment.. 2019;28:399-410.

- J. Phys. Chem. B.. 2000;104:3507-3517.

- Water. 2019;11

- Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2018;32:e4359

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2020;164:1087-1098.

- J. Polym. Environment.. 2020;28:962-972.

- J. Appl. Polym. Sci.. 2019;137

- J. Mater. Res.. 2019;34:1795-1804.

- J. Photochem. Photobiol. B.. 2019;199:111593

- Nano Mater.. 2021;4:6045-6056.

- Catalysis Today. 2019;335:160-165.

- Gels. 2022;8:256.

- Cellulose. 2021;28:2255-2271.

- Adv. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2020;281:102165

- Chem.. 2018;24:16804-16813.

- Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:22941-22949.

- J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:3930-3937.

- Macromol. Chem. Phys.. 2007;208:254-261.

- Appl. Catal. B: Environment.. 2018;226:16-22.

- J. Mater. Chem. A.. 2018;6:4590-4604.

- J. Macromol. Sci. Part A.. 2009;46:643-648.

- Front. Chem.. 2020;8:50.

- Macromol. Rapid Commun.. 2006;27:1346-1354.

- Carbohydr. Polym.. 2016;154:257-266.

- J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2008;318:217-224.

- Soft Mater.. 2021;19:480-494.

- Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;276:102103

- ACS Catal.. 2013;4:355-360.

- Soft. Matter.. 2018;14:1227-1234.

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2020;164:2477-2496.

- Pathakoti, K., Manubolu, M., Hwang, H.-M., 2018. Nanotechnology Applications for Environmental Industry. In: Handbook of Nanomaterials for Industrial Applications, pp. 894-907.

- Manage.. 2018;218:165-180.

- Chem. Rev.. 2020;120:11810-11899.

- J. Indust. Eng. Chem.. 2019;79:326-337.

- RSC Adv.. 2015;5:67394-67404.

- Appl. Catal. B: Environ.. 2010;101:137-143.

- Int. J. Polym. Mater.. 2013;62:590-595.

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2019;137:576-582.

- Chem. Eng.. 2017;5:1881-1891.

- Polym. Bull.. 2019;77:3349-3365.

- Reac. Func. Polym.. 2019;142:134-146.

- Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. 2021;235:1009-1026.

- Eng. Aspects. 2008;320:92.

- Chemosphere. 2021;275

- Adv. Mater.. 2009;21:3307-3329.

- Polymer Bull.. 2020;78:3869-3887.

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2020;147:1018-1028.

- J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2020;8:103602

- Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp.. 2018;553:618-623.

- Exp. Polymer Lett.. 2018;12:996-1004.

- J. Mater. Chem. B.. 2014;2:147-166.

- Catalysts. 2017;7

- J. Clean. Prod.. 2018;170:1536-1543.

- Mater. Sci. Eng. C: Mater. Biol. Appl.. 2019;97:624-631.

- Macromol. Mater. Eng.. 2017;302

- Separ. Purif. Tech.. 2020;233

- Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.. 2016;18:12610-12615.

- Appl. Catal. B: Environment.. 2018;233:11-18.

- Colloid Polym. Sci.. 2016;294:1087-1095.

- Reac. Func. Polym.. 1995;25:139-147.

- Cellulose. 2012;19:1239-1249.

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2018;119:402-412.

- App. Catal. B: Environ.. 2019;245:343-350.

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2017;95:294-298.

- Chemosphere. 2021;280:130792

- Cellulose. 2018;25:2547-2558.

- Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2020;156:1474-1482.

- Separ. Purif. Tech.. 2020;231

- Cellulose. 2021;28:3515-3529.

- RSC Adv.. 2013;3

- Biomaterials. 2020;230:119598

- J. Nanoparticle Res.. 2016;18

- J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem.. 2019;376:43-53.