Translate this page into:

An Alkali-extracted polysaccharide from Poria cocos activates RAW264.7 macrophages via NF-κB signaling pathway

⁎Corresponding author. wxzhang@sxau.edu.cn (Wuxia Zhang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

An alkali-extracted polysaccharide (PCAPS1) was isolated and purified from the Poria cocos. Our results proved that PCAPS1 was a neutral polysaccharide with a molecular weight of 11.5 kDa. The monosaccharide composition, methylation and NMR analysis results displayed that the polysaccharide was mostly comprised of β-1,3-glucan with 1,4 and 1,6 branches. The Immune activity and mechanism of PCAPS1 were evaluated in RAW264.7 cells. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis revealed that PCAPS1 increased the tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) secretion. RNA-sequencing data analysis suggested that PCAPS1 activated macrophages by the classic NF-κB pathway. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis confirmed that PCAPS1 enhanced mRNA expression levels of TNF-α and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) in RAW264.7 cells. Simultaneously, the fluorescence nuclear transport experiment showed that PCAPS1 activated RAW264.7 cells by inducing the NF-κB p65 translocation. Our results indicated that PCAPS1-induced TNF-α expression was mediated via the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Keywords

Poria cocos

Alkali-extracted polysaccharide

Immunomodulatory effect

β-glucan

NF-κB signaling pathway

1 Introduction

It has been reported that Poria cocos was an important edible and pharmaceutical mushroom with a multitude of biological functions, including antioxygenation, tumor cell inhibition, anti-inflammation, and immunomodulation (Sun 2014). The polysaccharide is one of the most important active ingredients in Poria cocos and played key roles in functions of Poria cocos, especially the immunoregulatory activity(Jia et al. 2016). For instance, polysaccharides from Poria cocos have been found to suppress interferon (IFN)-c-induced IP-10 protein (Lu et al. 2010), and activate macrophages through Ca2+/PKC/p38 signaling pathway (Pu et al. 2019). These are evidence for Poria cocos polysaccharide as an immunopotentiator for the food industry and medical field.

It has been known that functions of polysaccharides vary with structural features, such as glycosidic linkage, chemical composition, degree of branching, and spatial conformation, which can be determined by the specific extraction method and condition, (Zhang et al. 2020). Some reports have found that the biomechanical properties of the alkali-extracted polysaccharides were superior to those of water-extracted both in vitro and in vivo (Shi 2016). Liu et al. found that alkali-soluble polysaccharides inhibited the growth of three cancer cell lines and possessed anti-inflammation activities (Liu et al. 2019). However, it is still lack related studies about the immunoregulatory activity of alkali-extracted polysaccharides from Poria cocos. It is believed that Poria cocos polysaccharide plays an immunomodulatory role by regulating cytokine secretion. Therefore, in this study, a water-soluble polysaccharide using alkali extraction was extracted and purified from the Poria cocos, and its structural characterization was further analyzed by high-performance gel permeation chromatography (HPGPC), Fourier transmission infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR), high-performance anion exchange chromatography (HPAEC), gas chromatograph-mass (GC–MS), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). Then, we investigated the immunomodulatory ability of PCAPS1 and the underlying molecular mechanism in RAW264.7 cells.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents and materials

Dried Poria cocos were bought from Shaanxi Province of China. RPMI-1640 medium was purchased from Beijing Solarbio Technology Co., ltd. (Beijing, China). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), (E)-3-[(4-methylphenylsulfonyl]-2-propenenitrile (BAY 11–7082, NF-κB inhibitor) and NF-κB transport activation kit were purchased from Shanghai Beyotime Bio-Technology Co., ltd. (Shanghai, China). TNF-α and IL-10 ELISA kits were purchased from R&D Systems.

2.2 Preparation of polysaccharides

The polysaccharide extraction by alkaline solution was modified according to our reported previously (Zhang et al. 2015). The powder of Poria cocos was ground into a powder and then conducted with ethanol at 80 °C for 2 h. The solid residues were extracted triple times with distilled water for 2 h. Collected solid residues by pumping filtration, extracted triple times again with 0.2 M NaOH solution at 50 °C for 2 h. After being filtered, the supernatant was concentrated by a rotary evaporator and precipitated by the 4-fold volume of ethanol. Then, the obtained sample was dissolved and dialyzed in distilled water (Mw: 500 Da). Vacuum freeze-dry to obtain crude polysaccharide (PCAP). 2 g of crude polysaccharide of PCAP was dispersed in 100 mL distilled water and then fractionated by DEAE-cellulose column (6 cm × 50 cm, Cl-) with 0.1 M NaCl solution at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. The carbohydrate content of the fraction was monitored by the phenol–sulfuric acid method (Martins et al. 2017), and absorbances at 490 nm were measured for samples. The polysaccharide fraction with peak absorption was further purified using a Sephadex-G100 chromatography column (2 cm × 60 cm), which was eluted with distilled water at a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min. Combination, concentration, and lyophilized the fraction obtained PCAPS1. Samples were endotoxins free.

2.3 Molecular weight determination

The relative molecular weight of PCAPS1 was determined using the HPGPC system (Zhang et al. 2021). A standard curve based on Dextrans molecular weights (5.2、11.6、23.8、48.6、148、273、410 kDa). samples were dissolved and applied to a system consisting of a Waters 515 instrument fitted equipped with three ultrahydrogel columns (30 cm × 7.8 mm; 6 μm particles), and 2414 refractive index detector. 3 mmol/L sodium acetate as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The linear relationship between the logarithm of relative molecular weight (lg Mw) and retention time (T) was lg (Mw)= − 0.1719 T + 11.585.

2.4 FT-IR spectroscopy analysis

Dried PCAPS1 mixed with KBr in the ratio of 1:100 was analyzed by a Fourier transform infrared experiment (BRUKER TENSOR 27, BRUCK, Germany), and spectra reading was taken from 4000 to 400 cm−1. The annotation of absorption peaks was performed using Origin 2018 software (Govindan et al. 2021).

2.5 Chemical and monosaccharide composition

The total sugar content, proteins and uronic acid contents of PCAPS1 were analyzed by standard colorimetric methods using the phenol–sulfuric acid, Bradford’s method (Bradford 1976) and m-hydroxydiphenyl-sulphuric acid method (Blumenkrantz; Asboe-Hansen 1973), respectively.

The monosaccharide composition of PCAPS1 was carried out using the HPAEC (Hu et al. 2020). Briefly, the hydrolysis of dried PCAPS1 was conducted in the residual trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) at 120 °C for 3 h. After removing TFA, blown dry in a stream of nitrogen and mixed with water, Diluted and centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 5 min. Supernatant using a Dionex ICS-5000 (Thermo Scientific, USA) equipped with a CarboPac™ PA-20 analytical column (3 × 150 mm) and an electrochemical detector. Mobile phase: A: H2O, B:15 mM NaOH, C: 15 mM NaOH and 100 mM NaOAC, the column temperature was set at 30 °C, 0.3 mL/min of flow rate, and the sample volume was 5 μL.

2.6 Methylation analysis

The glycosidic linkages of PCAPS1 were carried out according to the methylation analysis (Dong et al. 2020). Added DMSO to dissolve PCAPS1, after the addition of the NaOH solution, methyl iodide was then further reacted for 60 min at 30 °C. Then methylated products were hydrolyzed, reduced, and acetylated, then analysis was performed on a GC–MS spectrometer (GCMS-QP 2010, Shimadzu, Japan) equipped with an RXI-5 SIL MS column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). The initial temperature of the column oven was 120 °C for 2 min, and the temperature was raised to 250 °C at 3 °C/min and maintained for 3 min. The injection temperature was 230 °C, and the flow rate was 1 mL/min.

2.7 NMR analysis

50 mg dried PCAPS1 was dissolved in 0.5 mL D2O. The NMR spectra were recorded with a Bruker 600 MHz NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Germany). 1H and 13C spectra, COSY spectra, HSQC spectra, and HMBC spectra were adopted to analyze the structural features of polysaccharides (Zhang et al. 2014).

2.8 Effects of PCAPS1 on cytokines production in RAW264.7 cells

The RAW264.7 cells were obtained from Prof. Jinyou Duan, Northwest A&F University, cultured using RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS). MTT assay was for cell viability, cells were plated into a 96-well plate at 1 × 105 cells/well and exposed to PCAPS1 (250 μg/mL, 500 μg/mL and 1000 μg/mL) for 24 h. An equal volume of Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) or LPS (2.5 μg/mL) as the control group or the positive group. The supernatants were collected for the TNF-α and IL-10 cytokines production experiments, determined by ELISA kits according to the instructions. Equal volumes of fresh medium containing MTT (5 mg/mL) were added, and cells were cultured for another 4 h. Dissolved the formazan by adding DMSO, and the absorbances were determined at 570 nm.

2.9 RNA library preparation, sequencing and data processing

RAW264.7 cells were treated with 500 μg/mL PCAPS1 for 12 h. Cells were collected, washed with phosphate buffer and centrifuged. The RNA-seq analysis was performed by Majorbio Bio-Pharm Technology Co.,ltd (Shangha, China). Generally, total RNA was extracted and sequenced. The resultant FASTQ format data were cleaned by using fastp (Chen et al. 2018). Sequence reads were aligned to the human reference genome to obtain the gene-level count datasets by the transcript quantification method Salmon (Patro et al. 2017). Then, the tximport package was used to aggregate the transcript-level quantification data to the gene-level estimated count matrices (Soneson et al. 2015).

To perform the clustering analysis of the sequencing data, the RNA-seq count data were transformed into the homoskedastic data using the regularized-logarithm transformation (rlog) implemented in the R package DESeq2 (version: 1.28.1) (Love et al. 2014). The PCAPS1-induced differential gene expression values versus the control group were calculated by DESeq2 on the raw counts.

2.10 RT-qPCR assay

Using qRT-PCR to validate the expression of genes of inflammatory genes in RAW 264.7cells (Zheng et al. 2021). Cells were treated with 500 µg/mL PCAPS1 for 6 h and collected for RNA extraction using Total RNA Kit I (OMEGA, America). Reversed to cDNA by using PrimeScriptTMRT Master Mix reagent kit (TaKaRa, Japan) according to the instructions. The expression of mRNA was performed with TB Green® Premix Ex TaqTM II (TaKaRa, Japan) on a QuantStudio 6 (ABI, America) detection system, its reaction conditions were 95 °C for 30 s, 95 °C denaturations for 5 s, 60 °C annealing for 30 s, and 40 cycles. The primer sequences as listed in Table 1. β-actin was used as endogenous control, and the expression levels of mRNA were calculated by using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Wang et al. 2019).

Gene

Sequences

actin-β

Forward: 5́-TCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTACGA-3́

Reverse: 5́-GGATGCCACAGGATTCCATACCCA-3́

TNF-α

Forward: 5́-ATAGCTCCCAGAAAAGCAAGC-3́

Reverse: 5́-CACCCCGAAGTTCAGTAGACA-3́

IL-10

Forward: 5́- CCAAGCCTTATCGGAAATGA-3́

Reverse: 5́- TTTTCACAGGGGAGAAATCG-3́

NF-κB

Forward: 5́-CCAAAGAAGGACACGACAGAATC-3́

Reverse: 5́-GGCAGGCTATTGCTCATCACA-3́

2.11 NF-κB activation- translocation assay

After PCAPS1 (500 μg/mL) or LPS stimulation for 3 h, cells were immunofluorescence-labeled using a Cellular NF-κB Activation-Translocation Kit according to the instruction. After being washed with PBS and fixation, incubated successively with blocking buffer, primary NF-κB p65 antibody and FITC-labeled Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h, cell nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The cells were visualized using a fluorescence microscope (Leica TCS SP8, Leica, Germany) (Xu et al. 2008).

2.12 Inhibitor blocking assay

Macrophages contain multiple receptor recognition sites on their surface, among them, mannose receptor (MR) mediated contains N-acetylglucosamine, mannose, and fucose of antigen (Apostolopoulos; McKenzie 2001). According to the analysis of monosaccharide composition, PCAPS1 contains mannose. To assess whether MR was involved in PCAPS1-induced macrophage activation, cells cultured in 96-well plates were pretreated with an MR inhibitor (mannose, 500 μg/mL) for 1 h, then PCAPS1 (500 μg/mL) was added for another 24 h. The culture supernatant was collected and the secretion of TNF-α in the culture medium was measured by the ELISA kit. Also, the NF-κB inhibitor BAY 11–7082 (2 μM) was used to verify the NF-κB pathway.

2.13 Statistical analysis

Data were repeated in three independent experiments for each sample and analyzed statistically by GraphPad Prism 9.0, expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was calculated by One-way or Two-way ANOVA analysis to determine the difference between groups.

3 Results

3.1 Extraction, purification and fractionation of PCAPS1

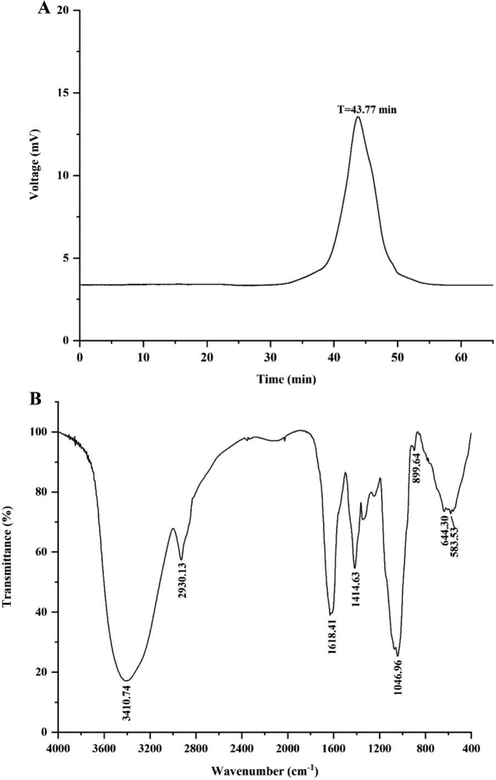

The alkali-extracted crude polysaccharide PCAPS was obtained from Poria cocos, with a yield of 3.50 %. After fractionation with a DEAE-Sepharose column, eluted with 0.1 M NaCl, obtained a polysaccharide fraction. Further purified by Sephadex G-100 column, eluted with distilled water, A pure polysaccharide component named PCAPS1. The yield of PCAPS1 from the PCAPS was 1.40 %. Chemical composition results showed that PCAPS1 was mainly composed of total sugar content (70.68 ± 10.88)% with a trace amount of protein (0.06 ± 0.20)% and uronic acid (2.94 ± 0.30)%. Furthermore, the HPGPC analysis showed that the molecular weight of PCAPS1 was 11.5 k Da (T = 43.77 min) (Fig. 1A).

HPGPC Chromatogram (A) and FT-IR spectrum (B) of PCAPS1.

3.2 FT-IR spectral analysis and monosaccharide composition

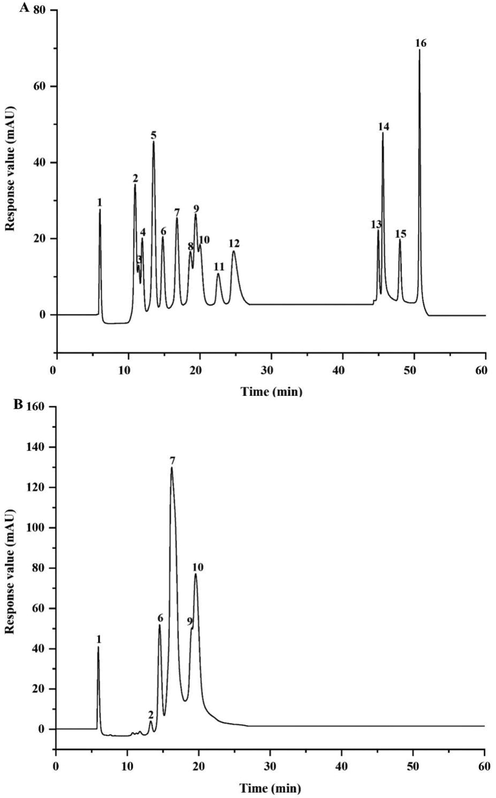

In Fig. 1B, the characteristic absorption peaks of PCAPS1 at 3410.74 cm−1 and 2930.13 cm−1 belonged to the stretching and bending of O—H and C—H, respectively. The peak at 1414.63 cm−1 contributed to the C—O stretching vibrations coupled with C—H bending vibrations (Acland et al. 2013). The peak at 1046.96 cm-1confirmed the presence of in C-OH group (Ka?Uráková; Wilson 2001). The absorption peaks at 899.64 cm−1 were due to the β-glycosidic bonds (Yanmin et al. 2021). The results of HPAEC proved that PCAPS1 was mainly composed of Glc, Man Gal, Xyl and Fuc, with the molar ratio 0.448: 0.287: 0.122: 0.077: 0.062 (Fig. 2).

Ion chromatogram of the standard monosaccharides (A) and PCAPS1 (B). 1: Fuc, 2: GalN, 3: Rha, 4: Ara, 5: GlcN, 6: Gal, 7: Glc, 8: GlcNAc, 9: Xyl, 10: Man, 11: Fru, 12: Rib, 13:GalA, 14:GulA, 15: GlcA, 16: ManA.

3.3 Methylation and NMR analysis

Methylation analysis provides information on the type and ratio of glycosidic bonds of polysaccharides. Combined with the results of monosaccharide composition, thirteen derivatives were revealed and characterized (Table 2). The results showed that PCAPS1 mainly consists of 1,3-linked glucose as a backbone with a minor amount of 1,4- and 1,6-branching. It also contains a smaller percentage of 1,4-Xylp, 1,3-Galp, 1,6-Galp and 1,2,3-Manp residues, the terminal residues are Manp, Glcp and Fucp.

RT

Methylated sugar

Mass fragments (m/z)

Molar ratio

Type of linkage

11.974

2,3,4-Me3-Fucp

43,59,72,89,101,115,117,131,175

0.013

Fucp-(1→

14.863

2,3-Me2-Xylp

43,71,87,99,101,117,129,161,189

0.023

→4)-Xylp-(1→

16.309

2,3,4,6-Me4-Glcp

43,71,87,101,117,129,145,161,205

0.133

Glcp-(1→

16.514

2,3,4,6-Me4-Manp

43,71,87,101,117,129,145,161,205

0.054

Manp-(1→

20.911

2,4,6-Me3-Glcp

43,87,99,101,117,129,161,173,233

0.567

→3)-Glcp-(1→

21.447

2,3,6-Me3-Glcp

43,87,99,101,113,117,129,131,161,173,233

0.030

→4)-Glcp-(1→

21.734

2,4,6-Me3-Galp

43,87,99,101,117,129,161,173,233

0.026

→3)-Galp-(1→

22.434

2,3,4-Me3-Glcp

43,87,99,101,117,129,161,189,233

0.060

→6-Glcp-(1→

24.42

2,3,4-Me3-Galp

43,87,99,101,117,129,161,189,233

0.014

→6)-Galp-(1→

24.615

2,6-Me2-Glcp

43,87,97,117,159,185

0.024

→3,4)-Glcp-(1→

24.811

2,6-Me2-Galp

43,87,99,117,129,143,159

0.019

→3,4)-Galp-(1→

25.451

4,6-Me2-Manp

43,85,87,99,101,127,129,161,201,216

0.011

→2,3)-Manp-(1→

27.662

2,4-Me2-Glcp

43,87,117,129,159,189,233

0.028

→3,6)-Glcp-(1→

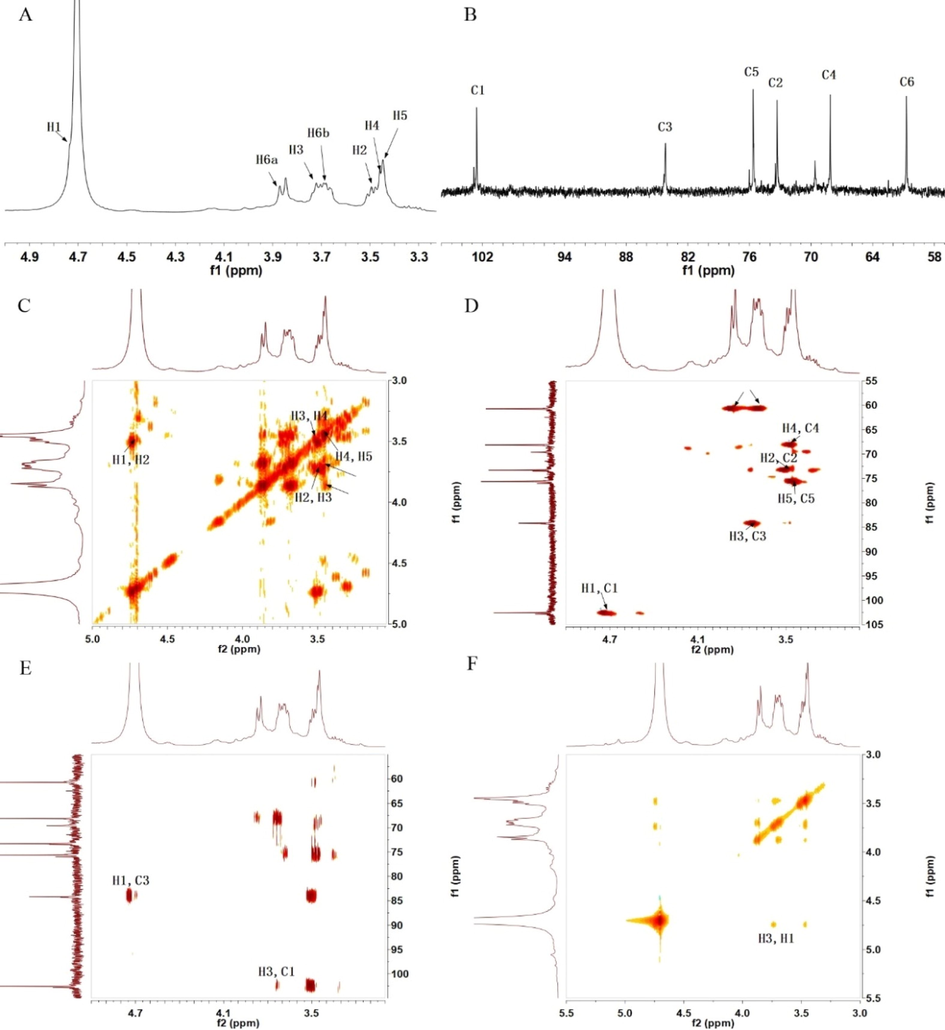

The structure of PCAPS1 was further provided by NMR spectra. The 1D and 2D NMR spectra were acquired to illustrate their structure. The 1H NMR spectrum suggested that the resonance signals at δ 4.73 ppm belonged to H-1 of the backbone 1,3-Glcp residue. Two distinct peaks were observed at δ 102.84 ppm and 102.56 ppm in 13C NMR. Among them, 102.56 ppm belonged to the C-1 of the backbone 1,3-Glcp. The backbone 1,3-Glcp was determined to be β form based on the peak position peaks of C1 and H1. This is corresponding to the results of IR spectrum analysis. According to the COSY and HSQC spectra, the six peaks at δ 3.49, 3.72, 3.46, 3.45, 3.87 and 3.69 ppm were the proton signals H2, H3, H4, H5 and H6 of β-1,3-Glcp, while the carbon signals of C2, C3, C4, C5, C6 were located at δ 73.48, 84.17, 68.13, 75.64, and 60.71 ppm. In the HMBC spectrum (Fig. 3E), large numbers of cross signal H1/C3 and H3/C2 were attributed to 3)-Glcp-(1 → 3)-Glcp-(1 →. In addition, there was an H1/H3 cross peak signal in the COSY spectra, further indicating that the 1,3-Glcp residue was β configuration. According to the results, PCAPS1 was a branched polysaccharide which the main backbone identified as 1,3-linked β-glucan backbone with 1,4-residues and 1,6-residues branches.

1H NMR spectrum (A), 13C NMR spectrum (B), 1H–1H COSY (C), HSQC spectrum (D), HMBC spectrum (E) and NOESY (F) of PCAPS1.

3.4 Immunomodulatory activities of PCAPS1 in RAW 264.7 cells

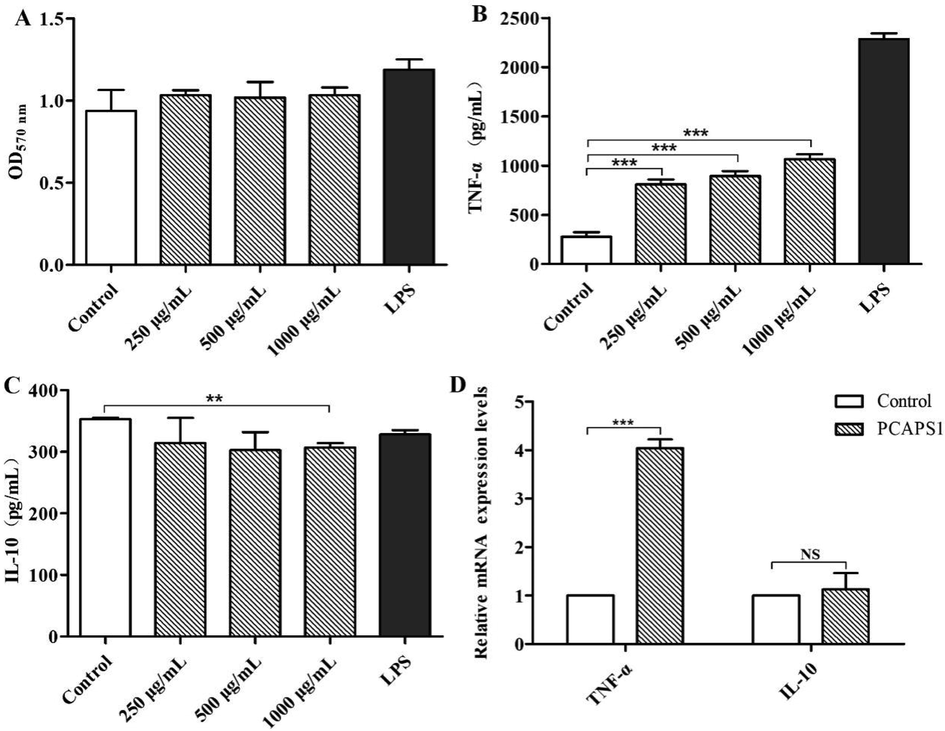

3.4.1 Effect of PCAPS1 on TNF-α production in RAW 264.7 cells

It is the production of cytokines that is one of the hallmarks of macrophage function (Jin et al. 2014). To study the effect of PCAPS1 on the activation of RAW264.7 cells, before the concentrations of TNF-α secretion were assayed with ELISA, cell viability and cytotoxicity were measured through MTT assay. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, PCAPS1 was non-toxic on RAW264.7 cells. After treated with 250 µg/mL, 500 µg/mL and 1000 µg/mL PCAPS1, the TNF-α production of macrophages increased about 3.35-fold, 3.73-fold, and 4.48-fold (Fig. 4B), respectively. The TNF-α production of RAW264.7 cells treated with 500 µg/mL of PCAPS1 reached about 839.43 pg/mL, which is much higher than in previous reports, such as ECIP-1A form Eurotium cristatum at the same concentration, the production of TNF-α was<175 pg/mL (Sayers et al. 2009). At the maximum concentration, the secretion of TNF-α was<300 pg/mL after incubation at 400 µg/mL polysaccharides from Apocynum venetum L. flowers (Wang et al. 2022). Moreover, compared to the control group, the mRNA expression of TNF-α was significantly increased by PCAPS1 treatment (Fig. 4D). These data suggested that PCAPS1 could make the cells immune function by the effect on the secretion of the levels of cell factor.

Effects of PCAPS1 at different concentrations on RAW264.7 cells: Effects on cell proliferation (A). TNF-α and IL-10 production (B and C). Effects on mRNA expression of TNF-α and IL-10 (D). (∗∗∗) P < 0.001, (∗∗) P < 0.01, and (∗) P < 0.05, compared with the control group.

IL-10 played a critical role in the immune defense system, itself inhibited the pro-inflammatory response and promoted the healing of injuries that resulted from inflammation (Ouyang; O'Garra 2019). To prove the effect of PCAPS1 on the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors by cells, the content of IL-10 in cell supernatant was determined by ELISA. The results showed that different concentrations of PCAPS1 had no significant effect on IL-10 secretion (Fig. 4C). Also, IL-10 mRNA levels were no significant increase after after treatment with 500 µg/mL PCAPS1 for 6 h (Fig. 4D). These results implied that PCAPS1 could not regulate the inflammatory function of RAW264.7 cells by IL-10.

3.4.2 Effects of PCAPS1 on NF-κB and MR in RAW 264.7 cells

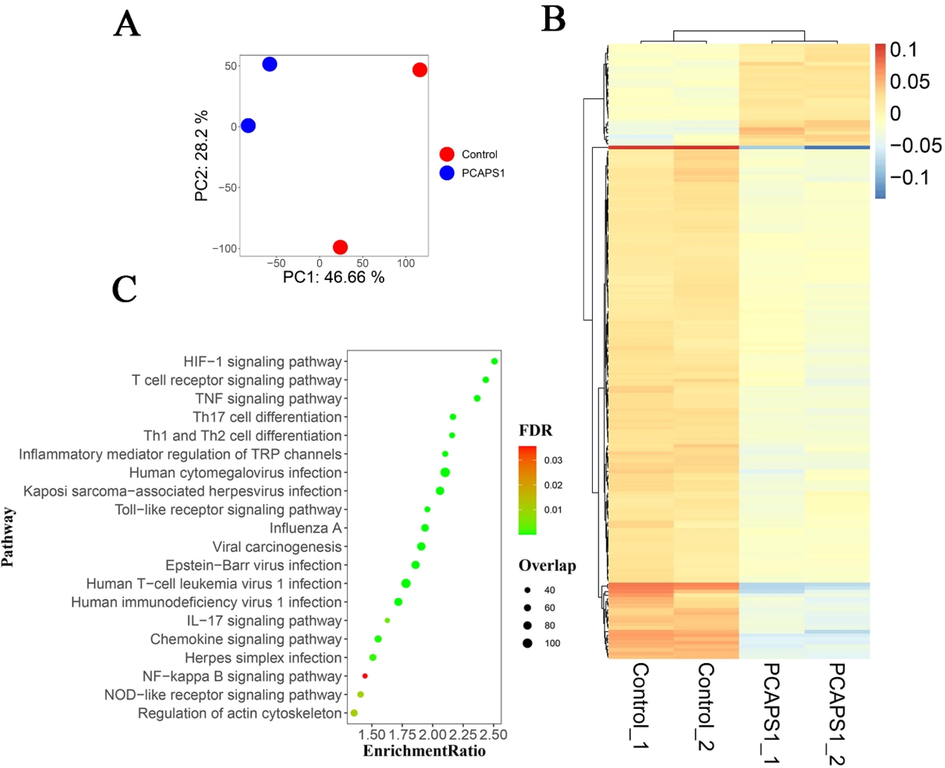

To detect the molecular mechanism of PCAPS1 for activating macrophage, we analyzed the overall gene expression profiles in RAW 264.7 cells treated by PCAPS1 through the RNA-seq technology. The principal component analysis and gene cluster analysis showed well clustering among between control and PCAPS1-treated groups (Fig. 5A, B). Pathway enrichment analysis showed that the top twenty pathways associated with immunity were significantly enriched (Fig. 5C), including “NF-κB pathway”, “Th1, Th2 and Th17cell differentiation”, “regulation of action cytoskeleton”, “nod-like receptor signaling pathway”, and “chemokine signaling pathway”. The NF-κB pathway had long been recognized as a typical proinflammatory signaling pathway (Lawrence 2009). Therefore, we further examined the impact of PCAPS1 for the NF-κB pathway.

Based on the principal component analysis diagram of transcriptome data (A): the red dot and blue dot represented control and PCAPS1 group, respectively. Heat map clustering of the differentially-expressed genes between two samples (B): bars on the right red to blue bars indicate gene expression levels from high to low. The bubble diagram of the top twenty pathways KEGG signaling pathway enrichment analysis (C): the abscissa represented the enrichment ratio, the ordinate represented the pathway name, the color indicates the correlation coefficient, and the size represented the number of differentially expressed genes enriched into each functional gene set.

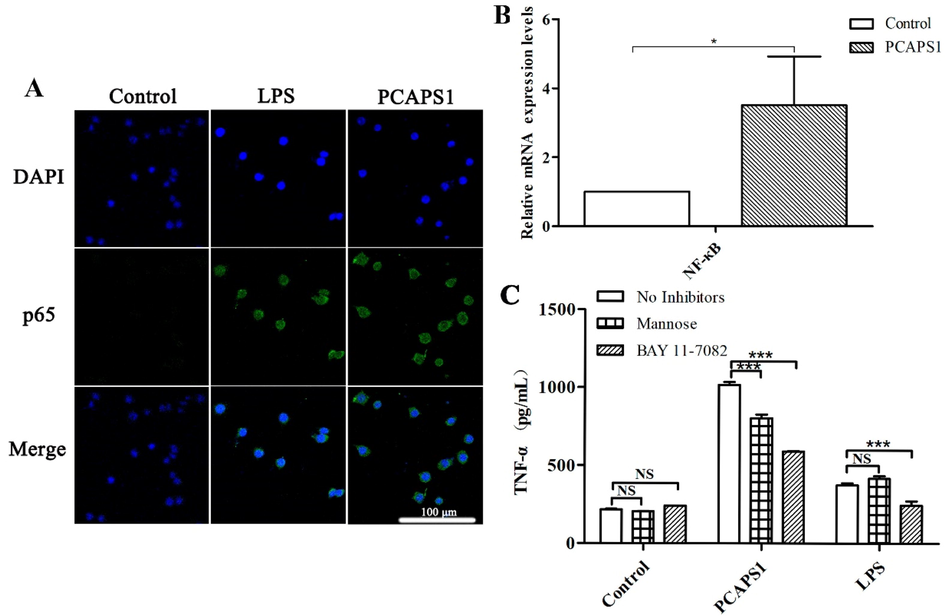

IκB was primarily presented in the cytoplasm, when phosphorylated IκB was degradation resulted in the activation, and nuclear translocation of the NF-κB p65 subunit into the nucleus, which mediated transcription of inflammatory factors leading to cytokine production (Jiang et al. 2020). The fluorescence assay set out with the aim of whether the PCAPS1-induced macrophage activation by NF-κB p65 subunit translocation into the nucleus. As shown in Fig. 6A, NF-κB p65 protein subunit translocated to the nucleus after PCAPS1 treatment. In the control group, the weaker green fluorescence indicated that only a small amount of the p65 protein subunit existed in the nucleus. After PCAPS1 treatment, the amount of green fluorescence increased, indicating that p65 protein was increased in the nucleus. In addition, RT-PCR analysis displayed that PCAPS1 up-regulated NF-κB mRNA expression in the RAW 264.7 cells after 6 h treatment (Fig. 6B). To further clarify the mechanism by which PCAPS1-induced cytokine production, we pretreated the RAW264.7 cells with signaling pathway inhibitors. The BAY 11–7082 treatment group markedly diminished the production of TNF-α (Fig. 6C). Thus, PCAPS1 activated the RAW264.7 cells through the NF-κB signaling pathway.

Effect of PCAPS1 on NF-κB activation in RAW 264.7 cells. PCAPS1 activated the p65 subunit of the NF-κB in RAW 264.7 cells. Cells were pretreated with PCAPS1 or LPS for 3 h, the fluorescence staining showed that NF-κB p65 protein transfer in the nucleus (Nuclei, blue labeled. NF-κB p65, green-labeled) (A). Effects on mRNA expression of NF-κB (B). Effects of BAY 11–7082 and mannose on PCAPS1-induced TNF-α secretion (C). (∗∗∗) represents P < 0.001 compared with the control group.

Due to their large molecular weight, polysaccharides need to bind to macrophage surface receptors to function (Schepetkin; Quinn 2006). MR blocking experiment showed that the secretion of TNF-α induced by PCAPS1 was significantly reduced, compared with the group without inhibitor (Fig. 6C).

4 Discussion

The residues of water-extracted polysaccharides could be extracted with alkaline solutions to maximize material utilization and expand the extraction yield. A novel polysaccharide named PCAPS1 was extracted by alkaline solution from Poria cocos residue, which mainly consisted of β-1,3-Glc with few 1,4-Glc and 1,6-Glc branches. Most fungal polysaccharides were conserved β-(1–3) and β-(1–6)-linked glucose (Snarr; Qureshi 2017). The polysaccharides with β-1,6-branched β-1,3-glucan found in Lentinus edodes promoted the proliferation of splenocytes and activated macrophages to produce TNF-α (Xing et al. 2017). Calocybe indica polysaccharide with β-glucose linked enhanced the expression of proinflammatory cytokines by activating myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MyD88)/NF-κB pathway by binding to toll-like receptors 4 (TLR4) (Ghosh et al. 2021). Macrocybe lobayensis polysaccharide with (1 → 3), (1 → 6)-linked β-d-glucans anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects (Ruthes et al. 2013). In addition, in the presence of higher molecular weights, polysaccharides with a complex structure, more results in combining membrane targets, and higher immunostimulatory activities were obtained (Du et al. 2019). Aconitum carmichaeli polysaccharide with a weight of 14 kDa influenced lymphocyte proliferation and antibody generation (Zhao et al. 2006). Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb polysaccharide with a weight of 33 kDa mediated the immune function of macrophages by activating the NF-κB pathway (Kim et al. 2007). Vernonia kotschyana polysaccharide with a weight of 20 kDa induced chemotaxis of macrophages, T cells, and NK cells (Nergard et al. 2005). The research showed that PCAPS1 had an immunostimulatory effect, which also could be linked to its molecular weight.

Polysaccharides played a prominent role in immunomodulatory agents, including activation of macrophages, T helper cells, NK cells, and promotion of T cell differentiation (Leung et al. 2006). Macrophages defend against invading pathogens by releasing cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β (Tong et al. 2015). The present study showed no toxicity to RAW 264.7 cells, illustrating the safety of this polysaccharide. Meanwhile, PCAPS1 increased the secretion of TNF-α, indicating that PCAPS1 induced the production of immunomodulatory factors in RAW264.7 cells. NF-κB is an important signaling pathway in immunity responses, after being activated by phosphorylation, it was translocated into the nucleus and caused transcription of chemokines, cytokines, and inflammatory mediators genes (Yu et al. 2020). Calocybe indica crude polysaccharides modulated macrophage cells serve a function by NF-κB pathway (Sandipta et al. 2021), a polysaccharide from Abelmoschus esculentus (L.), its proinflammatory responses also related to NF-κB signaling pathway (Liu et al. 2021). In this study, fluorescence and inhibitor neutralization experiments verified that PCAPS1 mediated RAW264.7 cells by activating NF-κB translocate to the nucleus, promoting the expression of TNF-α and NF-κB modulating secreting cytokines TNF-α production.

Taken together, PCAPS1 exhibited a great ability to stimulate macrophages through activation of the transcription factor NF-κB resulting in the increased transcription of proinflammatory cytokines. The NF-κB inhibitor could partially inhibit the secretion of cytokines TNF-α. Besides the NF-κB signaling pathway, the pathway enrichment analysis revealed that there may be other pathways in the immune response induced by PCAPS1, such as the “IL-17 signalingpathway” and “T cell receptor signaling”. In the further, we will examine these molecular pathways in immunoregulatory capacity of PCAPS1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.31800678), the Distinguished and Excellent Young Scholars Cultivation Project of Shanxi Agricultural University (No. 2022YQPYGC09), and the Fundamental Research Program of Shanxi Province (20210302124129).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res.. 2013;41:D8-D20.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Role of the mannose receptor in the immune response. Curr. Mol. Med.. 2001;1:469-474.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New method for quantitative determination of uronic acids. Anal. Biochem.. 1973;54:484-489.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem.. 1976;72:248-254.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., Y. Zhou, Y. Chen, and J. Gu, (2018). fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics, 34, i884-i890. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560.

- Structural characterization and immunomodulatory activity of a novel polysaccharide from Pueraria lobata (Willd.) Ohwi root. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2020;154:1556-1564.

- [Google Scholar]

- A concise review on the molecular structure and function relationship of β-Glucan. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2019;20:4032.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Crude polysaccharide from the milky mushroom, Calocybe indica, modulates innate immunity of macrophage cells by triggering MyD88-dependent TLR4/NF-κB pathway. J. Pharm. Pharmacol.. 2021;73:70-81.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and hepatoprotective effects of Hypsizygus ulmarius polysaccharide on alcoholic liver injury in rats. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 2021;10:523-535.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Manosonication extraction of RG-I pectic polysaccharides from citrus waste: optimization and kinetics analysis. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2020;235:115982

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prospects of Poria cocos polysaccharides: isolation process, structural features and bioactivities. Trends Food Sci. Technol.. 2016;54:52-62.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gastrodin protects against glutamate-induced ferroptosis in HT-22 cells through Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Toxicol. In Vitro. 2020;62:104715

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural features and biological activities of the polysaccharides from Astragalus membranaceus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2014;64:257-266.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ka?Uráková, M., and R. H. Wilson, (2001). Developments in mid-infrared FT-IR spectroscopy of selected carbohydrates. Carbohydrate polymers, 44, 291-303. 10.1016/s0144-8617(00)00245-9.

- Immunostimulating activity of crude polysaccharide extract isolated from Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.. 2007;71:1428-1438.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The nuclear factor NF-kappaB pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol.. 2009;1:a001651

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Polysaccharide biological response modifiers. Immunol. Lett.. 2006;105:101-114.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Purification, antitumor and anti-inflammation activities of an alkali-soluble and carboxymethyl polysaccharide CMP33 from Poria cocos. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2019;127:39-47.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural characterization and anti-inflammatory activity of a polysaccharide from the lignified okra. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2021;265:118081

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. GenomeBiol.. 2014;15:550.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Purification, structural elucidation, and anti-inflammatory effect of a water-soluble 1,6-branched 1,3-α-d-galactan from cultured mycelia of Poria cocos. Food Chem.. 2010;118:349-356.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro macrophage nitric oxide production by Pterospartum tridentatum (L.) Willk. inflorescence polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2017;157:176-184.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nergard, C. S., and Coauthors, (2005). Structural and immunological studies of a pectin and a pectic arabinogalactan from Vernonia kotschyana Sch. Bip. ex Walp. (Asteraceae). Carbohydr. Res., 340, 115-130. 10.1016/j.carres.2004.10.023.

- IL-10 family cytokines IL-10 and IL-22: from basic science to clinical translation. Immunity. 2019;50:871-891.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:417-419.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The immunomodulatory effect of Poria cocos polysaccharides is mediated by the Ca(2+)/PKC/p38/NF-κB signaling pathway in macrophages. Int. Immunopharmacol.. 2019;72:252-257.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ruthes, A. C., and Coauthors, (2013). Lactarius rufus (1→3),(1→6)-β-D-glucans: structure, antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects. Carbohydrate polymers, 94, 129-136. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.026.

- Crude polysaccharide from the milky mushroom, Calocybe indica, modulates innate immunity of macrophage cells by triggering MyD88-dependent TLR4/NF-κB pathway. J. Pharm. Pharmacol.. 2021;73:70-81.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sayers, E. W., and Coauthors, (2009). Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (vol 37, pg D5, 2008). Nucleic Acids Res, 37, 3124-3124. 10.1093/nar/gkp382.

- Botanical polysaccharides: macrophage immunomodulation and therapeutic potential. Int. Immunopharmacol.. 2006;6:317-333.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bioactivities, isolation and purification methods of polysaccharides from natural products: a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2016;92:37-48.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Immune recognition of fungal polysaccharides. J. Fungi (Basel, Switzerland). 2017;28:47.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Soneson, C., M. I. Love, and M. D. Robinson, (2015). Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Research, 4, 1521. 10.12688/f1000research.7563.2.

- Biological activities and potential health benefits of polysaccharides from Poria cocos and their derivatives. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2014;68:131-134.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H., M. Mao D Fau - Zhai, Z. Zhai M Fau - Zhang, G. Zhang Z Fau - Sun, G. Sun G Fau - Jiang, and G. Jiang, (2015). Macrophage activation induced by the polysaccharides isolated from the roots of Sanguisorba officinalis. Pharm. Biol., 53, 1511-1515. 10.3109/13880209.2014.991834.

- Immunoregulatory polysaccharides from Apocynum venetum L.flowers stimulate phagocytosis and cytokine expression via activating the NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathways in RAW264.7 cells. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 2022;11:9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Immunomodulation of ADPs-1a and ADPs-3a on RAW264.7 cells through NF-κB/MAPK signaling pathway. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2019;132:1024-1030.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Uptake of intraperitoneally administrated triple helical β-glucan for antitumor in murine tumor models. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2017;5

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ghrelin prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB pathways and mitochondrial protective mechanisms. Toxicology. 2008;247:133-138.

- [Google Scholar]

- Yanmin, Y., Q. Zhichang, L. Lingyu, V. S. K., Z. Zhenjia, and Z. Rentang, (2021). Structural characterization and antioxidant activities of one neutral polysaccharide and three acid polysaccharides from Ziziphus jujuba cv. Hamidazao: A comparison. Carbohydrate polymers, 261, 117879.

- Targeting NF-κB pathway for the therapy of diseases: mechanism and clinical study. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther.. 2020;5:209.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alteration in immune responses toward N-deacetylation of hyaluronic acid. Glycobiology. 2014;24:1334-1342.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of polysaccharides with antioxidant and immunological activities from Rhizoma Acori Tatarinowii. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2015;133:154-162.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural characterization and immunomodulatory activity of a novel polysaccharide from Lycopi Herba. Front. Pharmacol.. 2021;12:691995

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-inflammatory activity of alkali-soluble polysaccharides from Arctium lappa L. and its effect on gut microbiota of mice with inflammation. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2020;154:773-787.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and structural characterization of an immunostimulating polysaccharide from fuzi, Aconitum carmichaeli. Carbohydr. Res.. 2006;341:485-491.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multinuclei occurred under cryopreservation and enhanced the pathogenicity of Melampsora larici-populina. Front. Microbiol.. 2021;12:650902

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]