Translate this page into:

Botanical description, ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological activities of genus Kniphofia and Aloe: A review

⁎Corresponding author. tamefeyisa2008@gmail.com (Tamiru Fayisa Diriba),

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Genus Kniphofia and Aloe belong to Asphodeloideae and Alooideae subfamily of Asphodelaceae respectively. Asphodelaceae is a family of lily-related monocotyledonic flowering plants with 2 subfamilies, 16 genera and about 780 species distributed in arid and mesic regions of the temperate, subtropical and tropical zones of the old world, with the main center of diversity in southern Africa. The genus Kniphofia has about 70 species distributed in eastern and southern Africa, including the 7 species known to occur in Ethiopia, of which 5 species are endemic. Aloe is the largest genus among the Asphodelaceae family and it comprises of more than 400 species that are widely distributed in Africa, India, and other arid areas, with the major diversity in South Africa. The leaves of Kniphofia species are non-succulent, unlike the leaves of Aloe species. Aloe species are distinguished by having fleshy and cuticularized leaves usually with spiny margins. Kniphofia species have regular flowers with fused tepals while Aloe species have regular flowers with free tepals. Both Kniphofia and Aloe species have been employed in ethnopharmacology and have provided many bioactive compounds through phytochemical-pharmacological research works. They are traditionally used for treatment of various diseases by herbalists. Both genus elaborate naphthoquinone, preanthraquinone, anthraquinones and alkaloids in common. Additionally, Kniphofia elaborates benzene, naphthalene, and phloroglucinol derivatives while Aloe produces anthrones and chromones. The genus Kniphofia is rich in Knipholone type compounds while the genus Aloe is rich in anthrone-C-glycosides. Secondary metabolites isolated from the two genus have wide range of pharmacological activities such as antiplasmodial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. There is no published review article on the botanical description, traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological activities of the genus Kniphofia and only few review articles are available on the genus Aloe. In this review, an attempt is made to present pharmacological activities and secondary metabolites reported to date from genus Kniphofia and Aloe. Secondary metabolites reported from both plant genus have interesting biological activities so the authors of this review paper strongly recommend studies on toxicity of these compounds and their structural activity relationship so as to develop new pharmaceutical drug.

Keywords

Kniphofia

Aloe

Asphodelaceae

Bioactive compounds

Ethnopharmacology

1 Introduction

Genus Kniphofia and Aloe belong to the subfamily Asphodeloideae and Alooideae of the family Asphodelaceae respectively (Bringmann et al., 2008). Asphodelaceae is a family of lily-related monocotyledonic flowering plants with 2 subfamilies, 16 genera and about 780 species distributed in arid and mesic regions of the temperate, subtropical and tropical zones of the old world, with the main center of diversity in southern Africa (Bringmann et al., 2008; Demissew & Nordal, 2010; Smith, 1998). In addition to Kniphofia, Asphodeloideae subfamily consists of Asphodeline, Asphodelus, Bulbine, Bulbinella, Eremurus, Jodrellia, Simethis, and Trachyandra while Alooideae subfamily comprises Astroloba, Chamaealoe, Gasteria, Haworthia, Lomatophyllum, and Poellnitzia in addition to Aloe (Bringmann et al., 2008). Asphodelaceae plants have leaves arranged in a basal rosette and regular flowers with fused tepals (in Kniphofia) or free tepals (in all other genera), which may be white, greenish, yellow, pink or red (Demissew & Nordal, 2010; Edwards et al.,1997).

Both Kniphofia and Aloe species have been employed in ethnopharmacology and have provided many bioactive compounds through phytochemical-pharmacological research works (Table 2-5). Species of genus Kniphofia have been traditionally used to treat a variety of ailments in different African countries (Table 2). Kniphofia species primarily elaborate anthraquinones, as well as other compounds including benzene, naphthalene, and phloroglucinol derivatives, and alkaloids with wide range of pharmacological activities (Sema et al., 2018). On the other hand, plants of the genus Aloe have been used medicinally to cure different diseases in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Middle East for hundreds of years and they are included in many commercial preparations for various applications (Belayneh et al., 2020). Aloe species are the rich natural sources of bioactive compounds; majority of them being anthraquinones (Puia et al., 2021). There is no published review article on the botanical description, traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological activities of the genus Kniphofia and only few review articles are available on the genus Aloe. Therefore, the aim of this review is to compile reports on the botanical description, ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of the genus Kniphofia and Aloe.

Group

Description

Representative species

References

Group 1

Grass Aloes: Long and narrow leaves that have a grass like appearance

A. myriacontha

(Ayana, 2015)

Group 2

Lepto Aloes: Short-stemmed

A.nuttii

(Ayana, 2015)

Group 3

Bulbous species

A. bkettneri

(Ayana, 2015)

Group 4

Perianth striped

A. peckii, A. rugosifolia, A. pirottae

(Dagne et al., 1994)

Group 5

Compact rosettes or larger with open rosettes

A. dorotheae

(Dagneet al., 1994)

Group 6

Sapanariae: Plants with perianth pronounced basal inflation

A. lateritia, A. dumetorum, A. graminicola

(Dagne et al., 1994)

Group 7

Hereroenses: Plant sacaulescent or short-stemmed

A. hereroensis

(Ayana, 2015)

Group 8

Perianth trigonously indented above the ovary

A. chabaudii, A. rivae

(Dagne et al., 1994)

Group 9

Verae: Plants acaulous rarely caulescent, solitary or in group

A. barbadensis, A. pubescens

(Dagne et al., 1994)

Group 10

Pendet series

A. veseyi

(Ayana, 2015)

Group 11

Later bracteatae: Plants with bracts large, broadly ovate or suborbicular

A. cryptopoda

(Demissew & Nordal, 2010)

Group 12

Acaulescent or short stemmed

A. christianii

(Ayana, 2015)

Group 13

Perianths clavate

A. camperi, A. calidophila, A. sinana

(Dagne et al., 1994)

Group 14

Ortholophae: Flowers secund

A. secundiflora, A. ortholopha

(Dagne et al., 1994)

Group 15

Racemes bottle brush like: Plants with racemes densely flowered

A. aculeate

(Ayana, 2015)

Group 16

Large compact rosettes

A. percrassa, A. harlana

(Dagne et al., 1994)

Group 17

Leaves spreading, canaliculated

A. magalacantha, A. schelpei

(Dagne et al., 1994)

Group 18

Tall stemmed species

A. volkensii

(Ayana, 2015)

Group 19

Shrubs

A. dawei, A. arborescens

(Dagne et al., 1994)

Group 20

Trees

A. eminens

(Ayana, 2015)

Plant species

Part used

Disease treated

References

K. foliosa

Leaves

Hepatitis

(Yineger et al., 2007)

Roots

Abdominal cramps and wound

(Dagne & Steglich, 1984; Wube et al., 2006;Wube et al., 2005)

Not specified

Endoparasites of cattle

(Schmelzer et al., 2008)

K. isoetifolia

Roots

Gonorrhea and hepatitis B

(Yineger et al., 2008)

Not specified

Wound

(Meshesha et al., 2017)

K. caulescens

Root bulb

Headache, eye pain and fatigue

(Mugomeri et al., 2016)

K. northiae

Stems

Prolonged periods in women, and related pains

(Mugomeri et al., 2016)

K. drepanophylla

Rhizomes

Ringworm, wounds, pimples, acne, and eczema

(Sagbo & Mbeng, 2018)

Root

Tuberculosis

K. reflexa

Rhizomes

High relapsing fever

(Sema et al., 2018)

K. crassifolia

Rhizomes

Orchitis

(Ramarumo et al., 2019)

Rhizomes Flower

Hydrocele

Varicocele

Whole part

Erectile dysfunction

K. sumarae

Leaves and flowers

Malaria

(Mothana et al., 2009)

K. buchananii

Not specified

Snake bite and chest ailments

(Bringmann et al., 2008)

K. parviflora

K. laxiflora

K. rooperi

K. linearifolia

Root

Infertility of women

(Schmelzer et al., 2008)

Plant species

Part used

Disease treated

References

A. macrocarpa

Root Latex Fresh leaf

Impotency in men, Malaria, Bloat and fire burn

(Chekole et al., 2015; Bula & Baressa, 2017)

A. trichosantha

Latex

Malaria, Stomach ache, Gonorrhea, Impotency in men

(Bula & Baressa, 2017)

A. citrina

Latex

Swollen foot

A. monticola

Root

Liver disease, Anthrax

(Abera, 2014; Bula & Baressa, 2017)

A. gilbertii

Leaves gel, roots and exudates

Malaria, Wounds

(Dessalegn, 2013)

A. lateritia

Exudates

Eye ailments

A. pulcherrima

Sap

Asthma, Psychiatric disease

(Zenebe et al., 2012)

A. kefaensis

Latex

Fire burn

(Ayana, 2014)

Compounds

Species (part)

Reference

Naphthoquinone

3,5,8-trihydroxy-2-methylnaphthalen-1,4-dione (1)

K. isoetifolia (roots)

(Meshesha et al., 2017)

Pre-anthraquinones

Aloesaponol III (2)

K. foliosa (stem)

(Yenesew et al., 1994)

Aloesaponol III-8-methyl ether (3)

Monomeric anthraquinones

Chrysophanol (4)

K. foliosa (rhizomes)

(Gebru, 2010)

K. isoetifolia (roots)

(Meshesha et al., 2017)

K. foliosa (roots)

(Dagne & Steglich, 1984; (Wube et al., 2005)

K. foliosa (leaves)

(Berhanu & Dagne,1984)

K. thomsonii (roots)

(Achieng, 2009)

K. ensifolia (whole part)

(Dai et al., 2014)

K. reflexa (rhizomes)

(Sema et al., 2018)

Islandicin (5)

K. foliosa (rhizomes)

(Gebru, 2010)

K. thomsonii (roots)

(Achieng, 2009)

Laccaic acid D (6)

K. foliosa (rhizomes)

(Gebru, 2010)

Aloe-emodin acetate (7)

K. foliosa (leaves)

(Berhanu & Dagne,1984)

K. thomsonii (roots)

(Achieng, 2009)

Aloe-emodin (8)

K. thomsonii (roots)

(Achieng, 2009)

K. ensifolia (whole part)

(Dai et al., 2014)

Physcion (9)

K. thomsonii (roots)

(Achieng, 2009)

Kniphofione A (10)

K. ensifolia (whole part)

(Dai et al., 2014)

Kniphofione B (11)

Dimeric anthraquinones

Asphodeline (12)

K. isoetifolia (roots)

(Meshesha et al., 2017)

K. ensifolia

(Dai et al., 2014)

10-hydroxy-10-(chrysophanol-7′-yl) chrysophanolanthrone (13)

K. isoetifolia (roots)

(Meshesha et al., 2017)

K. foliosa (roots)

(Wube et al., 2005)

K. ensifolia

(Dai et al., 2014)

K. thomsonii (roots)

(Achieng, 2009)

Chryslandicin (14)

K. foliosa (roots)

(Wube et al., 2005)

K. ensifolia

(Dai et al., 2014)

K. thomsonii (roots)

(Achieng, 2009)

10, 10′-bichrysophanol anthrone (15)

K. thomsonii (roots)

(Achieng, 2009)

10-hydroxy-10-(chrysophanol-7′-yl)-aloe-emodinanthrone (16)

10-hydroxy-10-(islandicin-7′-yl)-aloe emodin anthrone (17)

Microcarpin (18)

K. ensifolia

(Dai et al., 2014)

10-methoxy-10,7′-(chrysophanol anthrone)-chrysophanol (19)

K. foliosa (roots)

(Abdissa et al., 2013)

Phenyl anthraquinones

Knipholone (20)

K. foliosa (rhizomes)

(Gebru, 2010)

K. foliosa (roots)

(Dagne & Steglich, 1984; (Wube et al., 2005)

K. foliosa (leaves)

(Berhanu & Dagne,1984)

K. thomsonii (roots)

(Achieng, 2009)

K. reflexa (rhizomes)

(Sema et al., 2018)

K. ensifolia

(Dai et al., 2014)

Knipholone anthrone (21)

K. foliosa (stem)

(Dagne &Yenesew,1993)

Isoknipholone (22)

K. foliosa (stem)

(Yenesew et al., 1994)

Isoknipholone anthrone (23)

Foliosone (24)

Isofoliosone (25)

Knipholone cyclooxanthrone (26)

K. foliosa (roots)

(Abdissa et al., 2013)

10-acetonylknipholone cyclooxanthrone (27)

K. foliosa (rhizomes)

(Induli et al., 2013)

Dimeric phenyl anthraquinones

Joziknipholone A (28)

K. foliosa (rhizomes)

(Gebru, 2010; Induli et al., 2013)

JoziknipholoneB (29)

Tetrameric phenyl anthraquinone

Jozi-joziknipholone anthrone (30)

K. foliosa (rhizomes)

(Gebru, 2010)

Other Compounds

3,4-dihydroxybenzoic acid (31)

K. foliosa (rhizomes)

(Gebru, 2010)

K. reflexa (rhizomes)

(Sema et al., 2018)

2-acetyl-1-hydroxy-8-methoxy- 3-methyl naphthalene (32)

K. foliosa (roots)

(Wube et al., 2005)

K. reflexa (rhizomes)

(Sema et al., 2018)

4,6-dihydroxy-2-methoxyacetophenone (33)

K. foliosa (stem)

(Yenesew et al., 1994)

Flavoglaucin (34)

K. thomsonii (roots)

(Achieng, 2009)

3′'',4′''-dehydroflavoglaucin (35)

Kniphofiarindane (36)

K. reflexa (rhizomes)

(Sema et al., 2018)

Kniphofiarexine (37)

Dianellin (38)

K. foliosa (roots)

(Abdissa et al., 2013)

N,N,N'-trimethyl-N'-[4-hydroxy-cis-cinnamoyl]-putrescin (39)

K. foliosa, K. flavovirens, K. tuckii (leaves)

(Ripperger et al., 1970)

N,N,N'-trimethyl-N'-[4-methoxy-cis-cinnamoyl]-putrescin (40)

Compounds

Species (part)

Reference

Alkaloids

Coniine (41)

A. sabaea (leaves)

(Blitzke et al., 2000)

Conhydrine (42)

A. gillilandii (leaves)

(Hotti & Rischer,2017)

g-Coniceine (43)

A. krapholiana (leaves)

(Dagne et al., 2000)

Anthraquinones

Chrysophanol (4), Helminthosporin (44), Aloeemodin (8), Aloesaponarin II (45), Aloesaponarin I (46)

A. megalacantha (root)

(Abdissa et al., 2017)

Pre-anthraquinones

Aloesaponol I (47)

A. megalacantha (root)

(Van Heerden et al., 2000)

Aloesaponol III (2), Aloesaponol IV (48), Aloesaponol-I-6-O-glucopyranoside(49), Aloesaponol-II-6-O-glucopyranoside (50), Aloesaponol-III-8-O-glucopyranoside (51)

A. saponaria (subterranean parts)

(Ayana, 2015)

Anthrones

Aloin A (52), Aloin B (53)

A. castanea (leaves exudate)

(Van Heerden et al., 2000)

5-Hydroxyaloin A (54), AloinosideA (55), Aloinoside B (56)

A. ferox (leaf exudate)

(Adhami & Viljoen, 2015)

10-hydroxyaloin B (57), Deacetyllittoraloin (58)

A. littoralis (leaf exudate)

(Karagianis et al., 2003)

Naphthoquinones

6-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxy-2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone (59), Ancistroquinone C (60), 5,8-dihydroxy-3-methoxy-2-methyl-1,4- naphthoquinone (61), Malvone A (62), Droserone (63), Droserone-5-methyl ether (64), Hydroxydroserone (65)

A. dawei (root)

(Abdissa et al., 2014))

Chromones

8-C-glucosyl-(S)-O-aloesol (66), 8-C-glucosyl-7-O-methylaloediol (67), 8-C-glucosyl noreugenin (68)

A. vera (leaves)

(Okamura et al., 1998)

Aloesin (69)

A. monticola (leaf latex)

(Hiruy et al., 2019)

7-hydroxy-2,5-dimethyl- chromone (70), Furoaloesone (71), 2-acetonyl-8-(2-furoylmethyl)-7-hydroxy-5-methylchromone (72)

A. ferox (leaf exudates)

(Kametani et al., 2007)

7-O-methyl-6-O-coumaroylaloesin (73)

A. monticola (leaf latex)

(Hiruy et al., 2019)

2 The review methodology

2.1 The study design

In this study, a comprehensive review design was used to compile information on the botanical descriptions, ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry and pharmacological properties of genus Kniphofia and Aloe.

2.2 The search strategy

The relevant sources were retrieved by using search engines such as Google Scholar and PubMed. Specific keywords, phrases and synonyms such as Kniphofia/genus Kniphofia/Kniphofia species/Kniphofia plants, Aloe/genus Aloe/Aloe species/Aloe plants, botanical descriptions/informations, ethnomedicinal uses/values or traditional uses/values or ethnopharmacological uses/values, phytochemistry or phytochemicals or secondary metabolites or natural products or compounds, pharmacological properties/activities or biological properties/activities were used for searching available literatures for the review.

2.3 Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies reporting botanical descriptions and/or ethnomedicinal uses of genus or specific species of Kniphofia and/or Aloe were included while reports on other related genus in the family Asphodelaceae were excluded in this review. Concerning phytochemistry part, studies reporting pure compounds isolated from the two genus and structurally characterized by spectroscopic techniques were included. However, those articles focusing only on qualitative analysis such as phytochemical screening tests or detection of compounds in the crude extract by using GC–MS or HPLC techniques and quantitative determinations of phytochemicals such as total phenol, total flavonoid, etc. were excluded. Regarding pharmacological properties, both in vitro and/or in vivo studies conducted on the crude extracts and/or isolated compounds were included while reports on biological activities of other derivatives such as nanoparticles synthesized from crude extracts and/or isolated compounds were excluded. In all cases, studies published in languages other than English were also excluded in this review.

2.4 Study selection

After collecting all sources, selection was made by quick analysis of the topics, abstracts and conclusions of the retrieved sources for eligibility criteria. Then after, the selected sources were deeply analyzed for preparation of this review article.

2.5 Softwares used

ChemDraw Ultra 8.0 software was used to draw the chemical structures of compounds and Mendeley Desktop reference management software was used to provide citations and references in this review.

3 Botanical description of genus Kniphofia and Aloe

3.1 Botanical description of genus Kniphofia

The genus Kniphofia named after the German botanist Johann Hieronymus Kniphof belongs to the subfamily Asphodeloidea of the family Asphodelaceae (Gebru, 2010). The genus includes about 70 species distributed essentially in eastern and southern Africa, including the 7 species known to occur in Ethiopia, of which 5 species are endemic (Demissew & Nordal, 2010). Plants of this genus grow from a thick rhizome in aggregates or solitarily, rarely with a thick, well developed woody stem. The leaves are arranged in basal rosettes, usually in 4 or 5 ranks, linear, tapering gradually to the apex (Demissew & Nordal, 2010). The leaves of Kniphofia species are non-succulent, unlike the leaves of Aloe species (Bringmann et al., 2008) and the flowers are usually pendulous, with varied colors: white, yellow, brownish or red (Demissew & Nordal, 2010). The flowering season is either winter or summer depending on the species (Bringmann et al., 2008). Most Kniphofia species grow near rivers or in damp or marshy areas although few species prefer dry conditions with good drainage (Bringmann et al., 2008).

3.2 Botanical description of genus Aloe

Aloe is the largest genus among the Asphodelaceae family and it comprises of more than 400 species ranging from diminutive shrubs to large trees that are widely distributed in Africa, India, and other arid areas, with the major diversity in South Africa. Aloe is represented in East Africa by 83 species, of which 38 grow naturally in Ethiopia, including 15 endemic species (Abdissa et al., 2017). They are distinguished by having fleshy and cuticularized leaves usually with spiny margins. Its name is taken from the Arabic word “Alloeh”, meaning “shining bitter substance” (Surjushe et al., 2008). There are 20 different groups (group 1 to 20) of the species of these plants according to Reynolds division by their similarities in morphology as depicted in Table 1.

4 Ethnomedicinal uses of genus Kniphofia and Aloe

4.1 Ethnomedicinal uses of genus Kniphofia

Genus Kniphofia has many records of medicinal values in treatment of various diseases. Its uses in treatment of hepatitis B, abdominal cramps, wound, gonorrhea and eradicating endoparasites of cattle are among the reported traditional uses of this genus in Ethiopia (Wube et al., 2006; Wube et al., 2005; Schmelzer et al., 2008; Dagne & Steglich, 1984; Meshesha et al., 2017; Yineger et al., 2007; Yineger et al., 2008). In other African countries, it is used in treatment of pain, prolonged periods in women, skin infections, tuberculosis, fever, infertility and as snake deterrent (Schmelzer et al., 2008; Bringmann et al., 2008; Ramarumo et al., 2019; Mothana et al., 2009; Mugomeri et al., 2016; Sagbo & Mbeng, 2018; Sema et al., 2018). Different parts of thLe plants such as leaves, roots, root bulb, stems, rhizomes and flowers are used in treatment of many ailments in traditional practices. Table 2 describes ethnomedicinal uses of genus Kniphofia.

4.2 Ethnomedicinal uses of genus Aloe

Aloe species have played important role in medicinal and economic history since 1500 BCE and the gel found in the interior of their leaves has been used to cure human and animals diseases (Abdissa et al., 2017). Plants in genus Aloe have been used for a broad range of medicinal purposes by traditional healers from wide variety of cultural groupings in Africa (Dagne, 1996). As well as these plants have been visited by traditional healers to treat various diseases in Ethiopia as depicted in Table 3. In rural parts of the country, its mucilaginous fluid applied to cuts and wounds in order to prevent infections and bring about healing (Tadesse & Mesfin, 2010).

5 Phytochemistry of genus Kniphofia and Aloe

5.1 Phytochemistry of genus Kniphofia

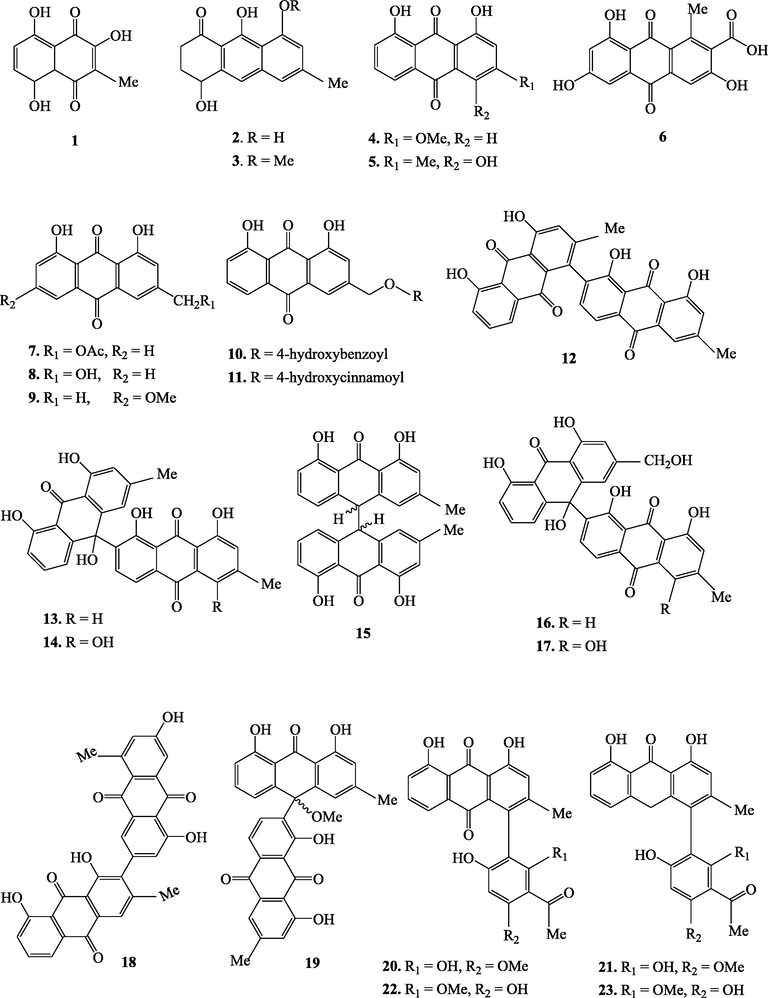

The genus Kniphofia is a rich source of anthraquinones besides other compounds such as benzene, naphthalene and phloroglucinol derivatives as well as alkaloids (Sema et al., 2018). This genus is well known to elaborate mainly monomeric and dimeric anthraquinones as well as phenyl anthraquinones. Anthraquinones of genus Kniphofia have a common structural feature which is hydroxylation at C-1 and C-8 positions of the anthranoid nucleus. Methylation at C-3 position is also commonly observed in most anthraquinones of this genus. Sometimes, this methyl group can also be oxidized as in the case of compounds 7, 8, 10, 11, 16 and 17 (Fig. 1). The dimers of different types which are believed to be formed by inter or intramolecular oxidative coupling of monomeric anthraquinones through carbon-carbon bonds have also been reported commonly in this genus.

Chemical structures of secondary metabolites isolated from Kniphofia species.

Chemical structures of secondary metabolites isolated from Kniphofia species.

Genus kniphofia is also reported to be one of the three important sources of phenyl anthraquinones after the genera Bulbine and Bulbinella (Bringmann et al., 2008). This special class of anthraquinones have a phenyl group (acetyl phloroglucinol moiety) attached to a chrysophanol or chrysophanol anthrone at C-4 or C-10 positions. Phenyl anthraquinones of genus kniphofia can also exist in monomeric, dimeric and tetrameric forms. Phenyl anthraquinones in which the acetyl phloroglucinol moiety is linked to oxychrysophanol anthrone at C-10 (as in the case of compounds 24 and 25) are called oxanthrones (Bringmann et al., 2008). Unusual monomeric phenyl anthraquinones in which cyclization involving C-10 and C-6′ via oxygen bridge leads to formation of one more ring (compounds 26 and 27) have also been reported in this genus (N. Abdissa et al., 2013; Induli et al., 2013). Phenyl anthraquinones having acetyl phloroglucinol moiety coupled to chrysophanol or chrysophanol anthrone unit via C-4 like knipholone (20) and its derivatives are by far the largest group in this genus (Bringmann et al., 2008). O-methylation pattern of the acetyl phloroglucinol moiety and/or the oxidation state of the anthranoid core leads to structural diversification among phenyl anthraquinones of this genus (Bringmann et al., 2008). Table 4 summarizes secondary metabolites isolated from different Kniphofia species.

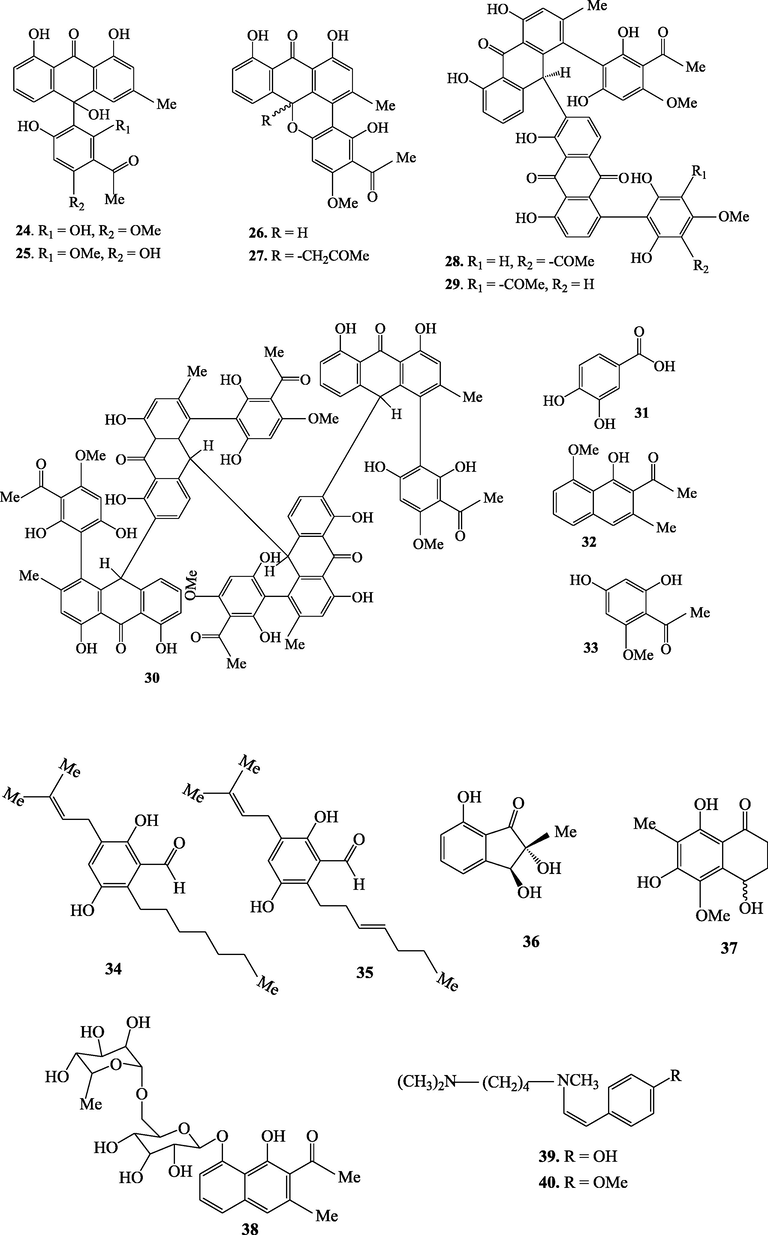

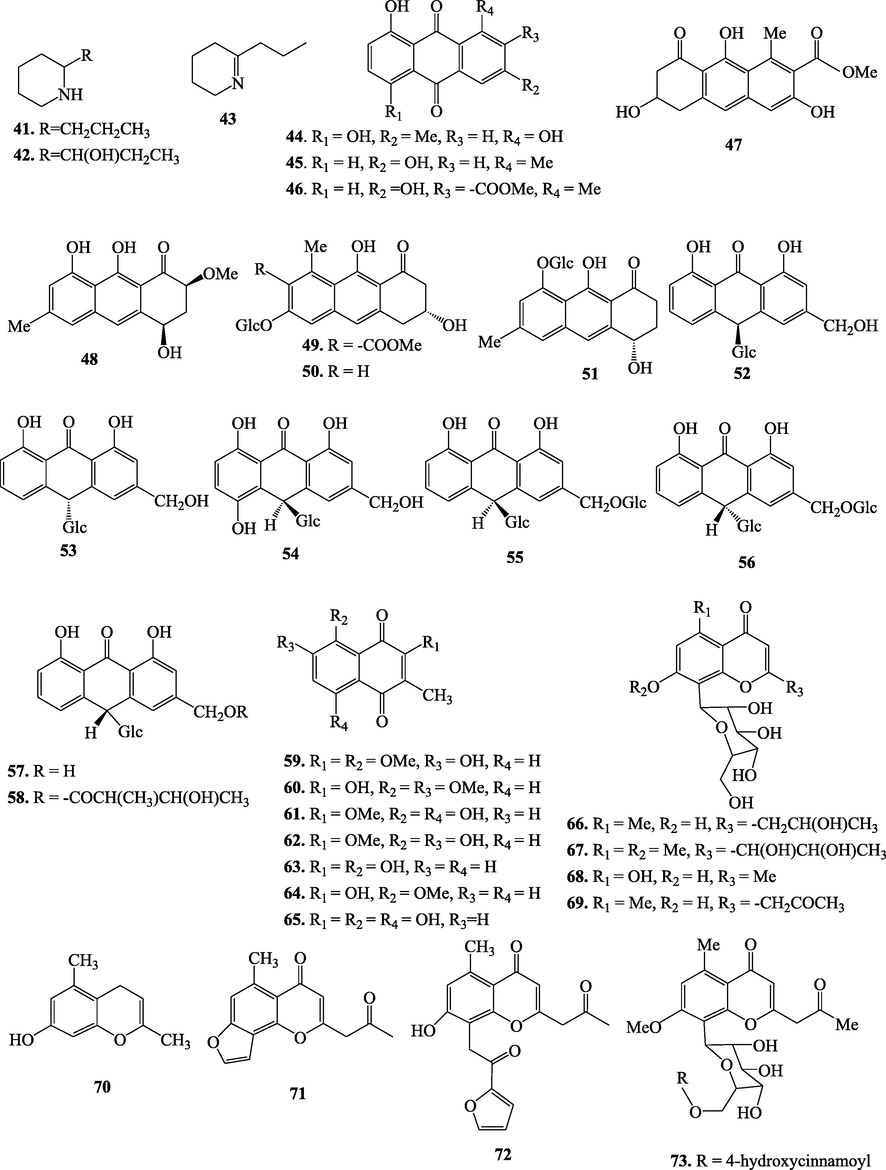

5.2 Phytochemistry of genus Aloe

Aloes are interesting sources of various classes of secondary metabolites (Table 5 and Fig. 2). Regarding the different composition of leave portions of Aloe species, they are likely to have distinct classes of bioactive compounds; outer green epidermis has been reported to contain alkaloids, anthraquinones, pre-anthraquinones. While the outer pulp region below the epidermis contains latex that predominantly consists of phenolic compounds, including anthraquinones, pre-anthraquinones, anthrones, chromones, coumarins, and flavonoids (Salehi et al., 2018). Besides leaves and roots are also the site of storage for many interesting secondary metabolites such as anthraquinones, pre-anthraquinones, anthrones, chromones, and alkaloids (Koroch et al., 2009). Methylation at C-1 and hydroxylation at C-8 positions of the anthranoid unit is commonly observed in anthraquinones of genus Aloe. This genus is also rich in anthrone-C-glycosides.

Chemical structures of secondary metabolites isolated from Aloe species.

6 Pharmacological activities of genus Kniphofia and Aloe

6.1 Pharmacological activities of genus Kniphofia

Anthraquinones which are the major secondary metabolites of Asphodelaceae family and genus Kniphofia have a wide range of pharmacological activities which include antiplasmodial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. The biological activities of genus Kniphofia are discussed in detail in the following sections.

6.1.1 Antiplasmodial activities

10-methoxy-10, 7′-(chrysophanol anthrone)-chrysophanol (19), 10-acetonyl knipholone cyclo oxanthrone (27) and joziknipholone A (28) from K. foliosa were investigated for in vitro antiplasmodial activities against the chloroquine resistant (W2) and chloroquine sensitive (D6) strains of Plasmodium falciparum (Abdissa et al., 2013; Induli et al., 2013). Compound 19 showed good activity with IC50 values of 1.17 ± 0.12 and 4.07 ± 1.54 µg/mL respectively. Compound 27 exhibited significant activity (IC50 = 3.1 ± 1.2 µg/mL) against the W2 strain of P. falciparum. Compound 28 was found to be the most active compound with IC50 values of 0.3 ± 0.1 μg/mL (against W2) and 0.4 ± 0.1 μg/mL (against D6).

10-(chrysophanol-7′-yl)-10 hydroxy chrysophanol anthrone (13) and chryslandicin (14) from the roots of K. foliosa were evaluated for their in vitro antimalarial activity against the chloroquine sensitive 3D7 strain of P. falciparum (Wube et al., 2005). Compounds 13 and 14 showed a high inhibition of the growth of P. falciparum with ED50 values of 0.260 and 0.537 µg/mL, respectively. Compounds 13 and 14 were also isolated from K. ensifolia and reported to have strong antiplasmodial activities with IC50 values of 0.4 ± 0.1 and 0.2 ± 0.1 µM, respectively against Dd2 strain of P. falciparum (Dai et al., 2014).

6.1.2 Anticancer activities

The antiproliferative activity of the methanol extract of K. sumarae was tested in vitro against three human cancer cell lines; 5637, MCF-7, A-427 and showed an IC50 values of greater than 50 μg/mL (Mothana et al., 2009). The cytotoxicity of knipholone (20) and knipholone anthrone (21) from K. foliosa was examined on leukaemic and melonocyte cancer cell lines (Habtemariam, 2010). Compound 21 was found to induce a rapid onset of cytotoxicity with IC50 values ranging from 0.5 to 3.3 μM while compound 29 showed 70–480 times less cytotoxicity to cancer cells (IC50 greater than 240 μM).

6.1.3 Anti-inflammatory activities

Knipholone (20) and chrysophanol (4) from the rhizomes of K. reflexa showed moderate anti-inflammatory activity against ROS production with CC50 value of 38.7 ± 4.90 and 20.00 ± 4.40 μg/mL, respectively (Sema et al., 2018). Compound 20 was also isolated from the roots of K. foliosa and investigated for inhibition of leukotriene biosynthesis in an ex-vivo bioassay using activated human neutrophile granulocytes (Wube et al., 2006). This compound was found to be a selective inhibitor of leukotriene metabolism in a human blood assay with an IC50 value of 4.2 μM.

6.1.4 Antioxidant activities

The free radical scavenging activity of methanol extract of K. sumarae was studied and reported to be 2.0, 6.8, 16.5, 66.1, 91.0 % at 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 μg/mL, respectively (Mothana et al., 2009). The antioxidant activity of knipholone (20) from the roots of K. foliosa was examined using various in vitro assay systems including free radical scavenging, non-enzymatic lipid peroxidation, and metal chelation (Wube et al., 2006). Knipholone was found to be a weak dose-independent free radical scavenger and lipid peroxidation inhibitor, but not a metal chelator. The radical scavenging activity of knipholone tested on the stable DPPH radical showed a very weak antioxidant property with an IC50 value of 355 μM compared to the positive control, quercetin (IC50 = 3.2 μM). Knipholone was also found to be a weak inhibitor of phospholipids liposomes peroxidation with an IC50 value of 311 μM compared to the positive control, quercetin (IC50 = 1.4 μM).

The antioxidant potential of knipholone anthrone (21) from K. foliosa was assessed using a variety of in vitro assay models (Habtemariam, 2007). This compound displayed IC50 value of 22 ± 1.5 μM in the DPPH assay while the positive control, (-)-epicatechin showed IC50 value of 8.7 ± 0.9 μM. The compound displayed a better activity than (-)-epicatechin in scavenging superoxide anions and preventing deoxyribose degradation by hydroxyl radicals. The compound was found to form a complex with iron (II) ion (Fe2+), displaying a concentration-dependant reducing power and also protected (at concentration of greater than 4.4 μM) isolated DNA from damage induced by Fenton reaction-generated hydroxyl radicals.

6.1.5 Antimicrobial activities

The antimicrobial investigations of genus Kniphofia has been reported to be carried out against microorganisms including Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis, Micrococcus flavus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida maltosa, Aliivibrio fischeri, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Enterococcus faecalis, Klebsiella pneumonia, Salmonella typhimurium.

The antimicrobial activity of methanol extract of K. sumarae was investigated against S. aureus, B. subtilis, M. flavus, E. coli, P. aeruginosa and C. maltosa (Mothana et al., 2009). The crude extract showed inhibition zones of 11, 7, and 14 mm respectively for the first three organisms but no activity was observed for the last three organisms.

Knipholone (20) and knipholone anthrone (21) from K. foliosa were tested for antibacterial activities against A. fischeri and M. tuberculosis (Feilcke et al., 2019). No more than 30% growth inhibition was observed at concentrations up to 100 μM and 10 μg/mL suggesting that both compounds have minimal antibacterial activities.

The CHCl3/CH3OH (1:1) crude extract and pure compounds from the roots of K. isoetifolia were evaluated for in vitro antibacterial activity against S. aureus, E. faecalis, P. aeruginosa and E. coli (Meshesha et al., 2017). The crude extract showed inhibition zone of 23 ± 0.81, 23 ± 0.89, 22 ± 0.30 and 28 ± 0.51 mm respectively against the listed bacteria. The isolated compounds were also evaluated and the inhibition zone of 16 ± 0.15, 19 ± 0.15, 23 ± 0.06, 17 ± 0.06 for 3,5,8-trihydroxy-2-methylnaphthalene-1,4-dione (1), 10 ± 0.26, 18 ± 0.06, 17 ± 0.25, 16 ± 0.30 for chrysophanol (4), 22 ± 0.32, 30 ± 0.12, 22 ± 0.06, 20 ± 0.05 for asphodeline (12) and 25 ± 0.01, 28 ± 0.15, 17 ± 0.15, 18 ± 0.06 mm for 10-hydroxy-10,7 -(chrysophanol anthrone) chrysophanol (13) were recorded respectively against the mentioned organisms. Among the tested compounds, chrysophanol (4) was found to be the least active (10–18 mm) while asphodeline (12) demonstrated relatively good zone of inhibition (20–30 mm).

The in vitro antibacterial activity of acetone crude extract of K. pumila was investigated and it was found to show growth inhibition zone of 12.6 ± 0.39, 11.8 ± 0.41, 10.7 ± 0.32 and 9.7 ± 0.28 mm against E. coli, K. pneumonia, S. aureus and S. typhimurium, respectively (Abdissa et al., 2020). Knipholone (20), the compound isolated from this plant displayed better activity than the crude extract against E. coli, S. aureus and S. typhimurium, with inhibition zone of 14 ± 0.13, 16 ± 0.42 and 12 ± 0.13 respectively.

6.2 Pharmacological activities of genus Aloe

As various report showed, the genus Aloe has interesting biological activities including antimicrobial, antiplasmodial, antioxidant, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and larvicidal activities.

6.2.1 Antimicrobial activities

The antimicrobial investigations of genus Aloe has been reported to be conducted against microorganisms such as Bacillus cereus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Candida albicans, Salmonella typhimurium, Aspergillus niger, Fusarium oxysporum, and different viruses.

The antibacterial activity of the leaves of A. rupestris and A. maculatavar were evaluated in vitro against B. cereus and showed inhibition zone of 22.3 ± 1.52 and 21.0 ± 2.0 mm respectively (Sonam & Archana, 2015; Omer et al., 2017). The leaves latex of A. monticola was also determined for in vitro antibacterial activity against S. typhi and showed inhibition zone of 15.0 ± 0.6 (Waithaka et al., 2018). The antibacterial activity of the leaves of A. vera was assessed against E. coli and P. aeruginosa and found to have inhibition zone of 29 and 20 mm respectively (Abakar et al., 2017). A. pulcherrima roots was also evaluated against P. aeruginosa and revealed inhibition zone of 21 mm (Abdissa et al., 2017). The leaves of A. vera was evaluated for its antifungal activity and showed inhibition zone of 20 and 23 mm against C. albicans and A. niger respectively (Saniasiaya et al., 2017; Waithaka et al., 2018). Antifungal activity of A. volkensii leaves pulp was also reported to have inhibition zone of 21 ± 1 mm against F. oxysporum (Waithaka et al., 2018). The antimicrobial activity of the Aloe species may attribute to the presence of chromones, anthraquinones, and their derivatives. As the screening for their in vitro antimicrobial activity shows compounds such as chrysophanol (4), Aloe-emodin (8), Aloesin (69), and 7-O-methyl-6, -O-coumaroylaloesin (73) are promising antimicrobial agents (Hiruy et al., 2019; Malmir, 2017).

As shown in many reports crude extract of from A. vera has antiviral activity on several types of virus (Haemorrhagic viral, Rhobda virus septicaemia, Herpes simplex virus type 1, Herpes simplex virus type 2, Varicella-Zoster virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Influenza virus, Polio virus, Cytomegalo virus, Human papilloma virus) including Corona virus SARS-CoV-1 (Mpiana et al., 2020). Such promising antiviral activity of this Aloe plant may attribute to the presence of anthraquinone derivatives, such as aloe-emodin (8) and chrysophanol (4) which have been reported to exhibit antiviral activity against influenza A virus with reducing virus-induced cytopathic effect and inhibiting replication of influenza A virus (Kumar, 2017). Extracts from flowers, flower-peduncles, leaves, and roots of A. hijazensis have also been evaluated for antiviral activities of against avian influenza virus type A (AI-H5N1), Newcastle disease virus (NDV), and egg-drop syndrome virus (EDSV). Extract of the flowers and leaves have showed higher activity than the extracts of other plant parts (Abd-Alla et al., 2012).

6.2.2 Antiplasmodial activities

Antiplasmodial/antimalarial activity of both crude extract and isolated anthrones (Aloin A (52) and aloin B (53) from the leaf latex of A. percrassa was studied in vivo using Peter’s 4-day suppressive test. After a four day treatment of P. berghei infected mice with the extract at doses of 100, 200 and 400 mg/kg/day, chemosuppression of 45.9%, 56.8% and 73.6% was observed respectively for each dose. Aloin A/B showed chemo-suppression of 36.8, 51.1, and 66.8 % (Geremedhin et al., 2014). Compounds isolated from the roots of A. pulcherrima; chrysophanol (4), aloesaponarin II (45) and aloesaponarin I (46), were evaluated for their in vitro antiplasmodial activity using malaria SYBR Green I-based in vitro assay against chloroquine resistant (W2) and chloroquine sensitive (D6) strains of P. falciparum. The isolates; chrysophanol (4) (IC50 21.05 ± 0.64), aloesaponarin II (45) (IC50 5.00 ± 0.36) and aloesaponarin I (46) (IC50 7.80 ± 1.11) showed considerable in vitro antiplasmodial activity against chloroquine-sensitive (D6) strain. Moreover these anthraquinones; chrysophanol (4) (IC50 36.09 ± 3.32), aloesaponarin II (45) (IC50 18.60 ± 7.10) and aloesaponarin I (IC50 20.13 ± 5.12) (46) have also showed significant antiplasmodial activity against chloroquine-resistant (W2) (Abdissa et al., 2017).

6.2.3 Antioxidant activities

The antioxidant capacities of crude extract of A. gilbertii were evaluated by using reducing power determination method. The methanol, ethanol, and ethyl acetate root extracts of the plant showed good antioxidant activity with 244.5 ± 0.631, 241.5 ± 0.112, and 106 ± 1.05 mg of ascorbic acid per 10 mg dry weight of antioxidant in the reducing power, respectively (Yadeta, 2019). The ethanol extracts of the peels of A. vera have also been reported to have high antioxidant activity with values of 2.43 mM ET/g MF (DPPH), 34.32 mM ET/g MF (ABTS), and 3.82 mM ET/g MF (FRAP).Total antioxidant activity was determined as the capturing of the DPPH and ABTS radicals, while the iron-reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) was analyzed by spectroscopic methods (Quispe et al., 2018).

6.2.4 Anticancer activities

Petroleum ether extract of A. perryi flowers was evaluated for its antiproliferative activity against seven human cancer cell lines (HepG2, HCT-116, MCF-7, A549, PC-3, HEp-2 and HeLa) using MTT assay. The percentage inhibition of the extract was reported to be 92.6%, 93.9%, 92%, 90.9%, 88.9%, 82% and 85.7% for HepG2, HCT-116, MCF-7, A- 549, PC-3, HEp-2 and HeLa cells, respectively (Al-Oqail et al., 2016). The in vitro anticancer activity of compounds isolated from A. turkanensis was evaluated using MTT assay against the human extra hepatic bile duct carcinoma (TFK-1) and liver (HuH7) cancer cell lines. The anthraquinone aloe-emodin (8) and the naphthoquinone 5,8-dihydroxy-3-methoxy-2-methylnaphthalene-1,4- dione (61) exhibited high inhibition against TFK-1 cell lines with IC50 values of 6.0 and 15.0 µg/mL (in TFK-1 cells) and 31 and 20 µg/mL (in HuH7 cell line), respectively (Fozia, 2014).

6.2.5 Anti-inflammatory activities

The anti-inflammatory activity of aqueous extract of A. barbadensis was investigated in rats using formalin-induced hind paw oedema. The results of the anti-inflammatory study revealed that 25, 50 and 100 mg/kg of the extract significantly reduced the formalin-induced oedema at the beginning of 3 h (Egesie et al., 2011). The anti-inflammatory activity of aqueous extract A. ferox leaf was studied using carrageenan and formaldehyde-induced rat paw oedema. The extract exhibited potential anti-inflammatory activity (78.2 and 89.3% for carrageenan and formaldehyde-induced rat paw oedema, respectively) at the dose of 400 mg/kg (Mwale & Masika, 2010).

6.2.6 Larvicidal activities

The ethyl acetate soluble extract of A. turkanensis was reported to have high larvicidal activity against the common malaria vector, Anopheles gambie, where 100% mortality was achieved at a concentration of 0.2 mg/ml and it had an LC50 of 0.11 mg/ml (Matasyoh et al., 2008). Crude extract of A. vera have been screened for its larvicidal activity against Musca domestica. Three instars larvae of housefly were treated with the different concentrations by dipping method for 24 and 48 hrs. The LC50 values of A. vera extract were found to be 32.67, 36 and 38.67 ppm in 24 hrs; 24, 25.67 and 28.33 ppm in 48 hrs on 1st, 2nd and 3rd instars respectively (Jesikha, 2012).

7 Conclusion

Botanically, genus Kniphofia and Aloe shares the same family (Asphodelaceae) while they belong to different subfamilies (Asphodoledeae and Aloideae respectively). They prefer different habitat and have different physical appearance regarding leaf and flower anatomy. Ethnomedicinally, species of the two genus are used for curing numerous ailments by herbalists. Phytochemically, both genus elaborate naphthoquinone, preanthraquinone, anthraquinones and alkaloids in common. Additionally, Kniphofia elaborates benzene, naphthalene, and phloroglucinol derivatives while Aloe produces anthrones and chromones. The anthraquinones of the two genus have different structural features. Most anthraquinones of genus Kniphofia are characterized by hydroxylation at C-1 and C-8, as well as methylation at C-3 positions of the anthranoid nucleus. Sometimes, the methyl group at C-3 position oxidizes to form alcohol or ester group. In the case of the genus Aloe, methylation at C-1 and hydroxylation at C-8 positions of the anthranoid unit is commonly observed. The genus Kniphofia is rich in Knipholone type compounds while the genus Aloe is rich in anthrone-C-glycosides. Pharmacologically, secondary metabolites isolated from the two genus have wide range of activities such as antiplasmodial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities.

8 Author Agreement

We accept the terms of Author Agreement on the Arabian Journal of Chemistry.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Antiviral activity of Aloe hijazensis against some haemagglutinating viruses infection and its phytoconstituents. Arch. Pharmacal Res.. 2012;35(8):1347-1354.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical investigation of Aloe pulcherrima roots and evaluation for its antibacterial and antiplasmodial activities. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0173882

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Extraction and isolation of compound from roots of kniphofia pumila, and its antibacterial activities in combination with zinc chloride. Walailak J. Sci. Technol.. 2020;17(7):631-638.

- [Google Scholar]

- Knipholone cyclooxanthrone and an anthraquinone dimer with antiplasmodial activities from the roots of Kniphofia foliosa. Phytochem. Lett.. 2013;6(2):241-245.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxic quinones from the roots of Aloe dawei. Molecules. 2014;19(3):3264-3273.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Medicinal plants used in traditional medicine by Oromo people, Ghimbi District, Southwest Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed.. 2014;10(1):40.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparative isolation of bio-markers from the leaf exudate of Aloe ferox (“Aloe bitters”) by high performance counter-current chromatography. Phytochem. Lett.. 2015;11:321-325.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro anti-proliferative activities of Aloe perryi flowers extract on human liver, colon, breast, lung, prostate and epithelial cancer cell lines. Pakistan J. Pharma. Sci.. 2016;29(2 Suppl):723-729.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical investigation of four asphodelaceae plants for antiplasmodial principles. Erepository.uonbi.ac.ke. 2015

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethno-medicinal and bio-cultural importance of Aloes from south and east of the Great Rift Valley floristic regions of Ethiopia. Heliyon. 2020;6(6):e04344

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aloe-emodin acetate, an anthraquinone derivative from leaves of Kniphofia foliosa. Planta Med.. 1984;50(6):523-524.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A chlorinated amide and piperidine alkaloids from Aloe sabaea. Phytochemistry. 2000;55(8):979-982.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knipholone and related 4-phenylanthraquinones: Structurally, pharmacologically, and biosynthetically remarkable natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep.. 2008;25(4):696-718.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aloes of Ethiopia: a Review on Uses and Importance of Aloes in Ethiopia. Int. J. Plant Biol. Res. 2017

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in the environs of Tara-gedam and Amba remnant forests of Libo Kemkem District, northwest Ethiopia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed.. 2015;11(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Review of the chemistry of Aloes of Africa. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop.. 1996;10(1)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knipholone anthrone from Kniphofia foliosa. Phytochemistry. 1993;34(5):1440-1441.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anthraquinones, pre-anthraquinones and isoeleutherol in the roots of Aloe species. Phytochemistry. 1994;35(2):401-406.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knipholone: a unique anthraquinone derivative from Kniphofia foliosa. Phytochemistry. 1984;23(8):1729-1731.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isolation of antiplasmodial anthraquinones from Kniphofia ensifolia, and synthesis and structure-activity relationships of related compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2014;22(1):269-276.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Study on the populations of an endemic Aloe species (A. gilbertii Reynolds) in Ethiopia. Eng. Sci. Technol.: Int. J.. 2013;3(3):562-576.

- [Google Scholar]

- Flora of Ethiopia and Eritrea. Hydrocharitaceae to Arecaceae: The National Herbareum, Addis Ababa Universtiy; 1997.

- Anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects of aqueous extract of Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis) in rats. African J. Biomed. Res.. 2011;14(3):209-212.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological activity and stability analyses of knipholone anthrone, a phenyl anthraquinone derivative isolated from Kniphofia foliosa Hochst. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.. 2019;174:277-285.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical and antiplasmodial investigation of rhamnus prinoides and kniphofia foliosa. Erepository.uonbi.ac.ke. 2010

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation, characterization and in vivo antimalarial evaluation of anthrones from the leaf latex of Aloe percrassa Todaro. J. Nat. Remedies. 2014;14(2):119-125.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activity of Knipholone anthrone. Food Chem.. 2007;102(4):1042-1047.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knipholone anthrone from Kniphofia foliosa induces a rapid onset of necrotic cell death in cancer cells. Fitoterapia. 2010;81(8):1013-1019.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Two chromones with antimicrobial activity from the leaf latex of Aloe monticola Reynolds. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2019;35(6):1052-1056.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The killer of Socrates: Coniine and related alkaloids in the plant kingdom. Molecules. 2017;22(11):1962.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antiplasmodial quinones from the rhizomes of Kniphofia foliosa. Nat. Prod. Commun.. 2013;8(9):1261-1264.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of larvicidal efficacy of Aloe vera extract against Musca domestica. IOSR J. Environ. Sci., Toxicol. Food Technol.. 2012;2(2):01-03.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents of cape Aloe and their synergistic growth-inhibiting effect on ehrlich ascites tumor cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem.. 2007;71(5):1220-1229.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of major metabolites in Aloe littoralis by high-performance liquid chromatography-nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Phytochem. Anal.. 2003;14(5):275-280.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biology and chemistry of the genus Aloe from Africa. ACS Symp. Ser.. 2009;1021:171-183.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating antimicrobial activity of Aloe vera plant extract in human life. Biomed. J. Scient. Tech. Res.. 2017;1(7):1854-1856.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anthraquinones as potential antimicrobial agents-A review. Antimicrobial research: Novel bioknowledge and educational programs. Formatex; 2017. p. :55-61.

- Aloe plant extracts as alternative larvicides for mosquito control. Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2008;7(7):912-915.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents of the roots of Kniphofia isoetifolia Hochst. and evaluation for antibacterial activity. J. Pharm. Pharmacogn. Res.. 2017;5(6):345-353.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the in vitro anticancer, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of some Yemeni plants used in folk medicine. Pharmazie. 2009;64(4):260-268.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mpiana, P. T., Ngbolua, K.-T.-N., Tshibangu, D. S. T., Kilembe, J. T., Gbolo, B. Z., Mwanangombo, D. T., Inkoto, C. L., Lengbiye, E. M., Mbadiko, C. M., Matondo, A., Bongo, G. N., & Tshilanda, D. D. (2020). Aloe vera (L.) Burm. F. as a potential anti-covid-19 plant: A mini-review of its antiviral activity. European Journal of Medicinal Plants, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.9734/ejmp/2020/v31i830261.

- Ethnobotanical study and conservation status of local medicinal plants: towards a repository and monograph of herbal medicines in Lesotho. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med.. 2016;13(1):143-156.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of Aloe ferox Mill. aqueous extract. African J. Pharm. Pharmacol.. 2010;4(6):291-297.

- [Google Scholar]

- Achieng, O.I. (2009). Antiplasmodial anthraquinones and benzaldehyde derivatives from the roots of kniphofia thomsonii. https://profiles.uonbi.ac.ke/achiengimma/files/ima-abstract.pdf.

- Five chromones from Aloe vera leaves. Phytochemistry. 1998;49(1):219-223.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity and minimum inhibitory concentration of Aloe vera sap and leaves using different extracts. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem.. 2017;6(3):298-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- The phytochemical constituents and therapeutic uses of genus Aloe: a review. Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca. 2021;49(2):1-16.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of Aloe vera from the Pica Oasis (Tarapaca Chile) by UHPLC-Q/Orbitrap/MS/MS. J. Chem.. 2018;2018

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Warburgia salutaris (G. Bertol.) Chiov.: An endangered therapeutic plant used by the Vhavenda ethnic group in the Soutpansberg, Vhembe Biosphere Reserve, Limpopo province, South Africa. Res. J. Pharm. Technol.. 2019;12(12):5893.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Putrescine amides from Kniphofia species. J. Pract. Chem.. 1970;312(3):449-455.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plants used for cosmetics in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa: a case study of skin care. Pharmacogn. Rev.. 2018;12(24):139-156.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aloe genus plants: From farm to food applications and phytopharmacotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2018;19(9)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal effect of Malaysian Aloe vera leaf extract on selected fungal species of pathogenic otomycosis species in in vitro culture medium. Oman Med. J.. 2017;32(1):41-46.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer, G. H., Gurib-Fakim, A., Arroo, R., Bosch, C. H., Ruijter, A. de, Simmonds, M. S. J., Lemmens, R. H. M. J., & Oyen, L. P. A. (2008). Plant Resources of Tropical Africa 11(1) : Medicinal plants 1. In research.wur.nl. PROTA Foundation [etc.]. https://research.wur.nl/en/publications/plant-resources-of-tropical-africa-111-medicinal plants-1.

- Sema, D. K., Meli Lannang, A., Tatsimo, S. J. N., Mujeeb-ur-Rehman, Yousuf, S., Zoufou, D., Iqbal, U., Wansi, J. D., Sewald, N., & Choudhary, M. I. (2018). New indane and naphthalene derivatives from the rhizomes of Kniphofia reflexa Hutchinson ex Codd. Phytochemistry Letters, 26(May), 78–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phytol.2018.05.025

- Smith, G. F., & Wyk, B. E. (1998). Asphodelaceae. In flowering plants· Monocotyledons (pp. 130-140). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Antibacterial efficacy of Aloe species on pathogenic bacteria. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Manage.. 2015;4(1):143-151.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aloe vera: A short review. Indian Journal of Dermatology. 2008;53(4):163.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A review of selected plants used in the maintenance of health and wellness in Ethiopia. Ethiopian E-J. Res. Inov. Foresight. 2010;2(1):85-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- 6′-O-Coumaroylaloesin from Aloe castanea-a taxonomic marker for Aloe section Anguialoe. Phytochemistry. 2000;55(2):117-120.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial properties of Aloe vera, Aloe volkensii and Aloe secundiflora from Egerton University. Acta Scient. Microbiol.. 2018;1(5):06-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimalarial compounds from Kniphofia foliosa roots. Phytother. Res.. 2005;19(6):472-476.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Knipholone, a selective inhibitor of leukotriene metabolism. Phytomedicine. 2006;13(6):452-456.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical investigation and antioxidant activity of root extract of Aloe gilbertii Reynolds, from Konso, Southern Ethiopia. Am. J. Appl. Chem. 2019

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An anthrone, an anthraquinone and two oxanthrones from Kniphofia foliosa. Phytochemistry. 1994;37(2):525-528.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ethnoveterinary medicinal plants at Bale Mountains National Park, Ethiopia. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2007;112(1):55-70.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plants used in traditional management of human ailments at Bale Mountains National Park, South Eastern Ethiopia. J. Med. Plants Res.. 2008;2(6):132-153.

- [Google Scholar]

- An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Asgede Tsimbila District, Northwestern Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Ethnobotany Res. Appl.. July 2012;10:305-320.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]