Translate this page into:

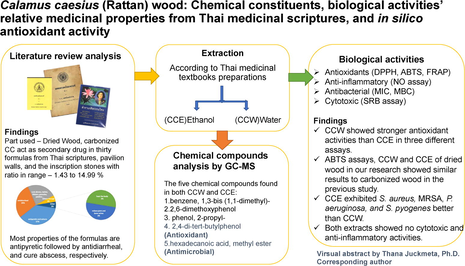

Calamus caesius (Rattan) wood: Chemical constituents, biological activities’ relative medicinal properties from Thai medicinal scriptures, and in silico antioxidant activity

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Applied Thai Traditional Medicine, School of Medicine, Walailak University, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80160, Thailand. thanajuckmeta9@gmail.com (Thana Juckmeta)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

Calamus caesius is known as Rattan. It was found as a component of many formulas from evidence-based Thai medicinal scriptures but no research about their medicinal properties. We investigated the literature review analysis from Thai medicinal textbooks for proposed biological activity relatives including antioxidant, cytotoxic, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities, and chemical profiles using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS). In silico studies were inspected on tyrosinase and NAD(P)H oxidase actions. Thirty formulas from Thai medicinal textbooks found C. caesius as a component with a percent ratio in the range of 1.43 to 14.99, the formula's properties are antipyretic, followed by antidiarrhea, and cure abscesses related to inflammation and infection. Both water extracted and ethanol extracted showed high antioxidant activities in all assays and showed no toxicity in macrophage-like cells and cancer cell lines. The ethanol extracted showed slightly bactericidal better than the water extracted, none of them inhibited against C. albicans. From GC–MS analysis, the highest components of water and ethanol extract are 3-tert-Butylamino-acrylonitrile and β-Sitosterol, respectively. Five chemical compounds revealed in both water and ethanol extracted of C. caesius are 1,3-di-tert-butylbenzene; 2,6-dimethoxyphenol; 2-propylphenol; 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol; methyl palmitate. Sterol compounds such as stigmasterol, beta-sitosterol, and campesterol from ethanol extracted showed outstanding interaction with both tyrosinase and NADPH oxidase in silico molecular docking study. All outcomes proven that C. caesius has potentially antioxidant effects to support health problems. Additionally, this is the first report on the scientific data of Calamus caesius wood related to its medicinal properties in the formula from Thai medicinal scriptures.

Keywords

Calamus caesius

Rattan

Thai medicinal scriptures

Biological activities

Molecular docking

GC–MS

- ABTS

-

2,2′-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt

- BHT

-

Butylated hydroxytoluene

- DMEM

-

Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium

- DMSO

-

Dimethylsulfoxide

- DPPH

-

2,2–Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- FBS

-

Fetal bovine serum

- FRAP

-

ferric reducing antioxidant power

- HCl

-

Hydrochloric acid

- LPS

-

Lipopolysaccharide from E. coli O55:B5

- MBC

-

Minimum bactericidal concentration

- MHA

-

Mueller-Hinton agar

- MHB

-

Mueller-Hinton broth

- MIC

-

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

- MRSA

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- MTT

-

Thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide, 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2- thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide

- NO

-

Nitric oxide

- OD

-

Optical density

- PBS

-

Phosphate buffer saline

- RAW264.7

-

Mouse macrophage leukemia-like

- RPMI

-

RPMI 1640 Medium

- SRB

-

Sulphorhodamine B

- Sulfanilamide

-

N-(1-Naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride

- Trolox

-

6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetra-methylchroman-2-carboxylic acid

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Calamus caesius Blume (family Arecaceae) is widespread in South-East Asia, including Malaysia, Sumatra, Borneo, Palawan (the Philippines), and southern Thailand. C. caesius has a resilient and durable cane commonly used to make high-quality rattan carpets, mats, baskets, and in-house handicrafts or construction (Shim and Tan, 1993). In terms of medicinal use, the vine has a cold taste used to cure heat exhaustion, black fever, convulsions due to heat, relieve suffocation, stiff tongue and chin due to fever (Ayurvedic school, 2016).

To continue survival, the body maintains a consistent core temperature range of 37.2–37.7 °C or 99-100°F; fever or pyrexia or hyperthermia is defined as having a temperature above the average normal. Causes of fever are categorized by exogenous pyrogens (microbial substances, ex. LPS in the cell wall of bacteria) and endogenous pyrogens (cytokines of inflammatory mechanisms such as IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α). Some drugs such as antibiotics, antidepressants, and antihistamines also induce hyperthermia. Several signs and symptoms of fever are headaches, sweating, thirst, chills or shivering, nausea, lacking energy, poor appetite, etc (Ogoina, 2011). Antipyretic drugs, acetaminophen, aspirin, and ibuprofen are generally used for suppressing fever (Plaisance and Mackowiak, 2000).

Thai Traditional medicine (TTM) theory claims the human body is controlled by the balance of Tri-Dhatu (three elements) - consisting of Pit-ta (fire), Va-ta (wind), Sem-ha (water). Pit-ta represents all heat in the body involved in cell metabolisms, GI digestion, and thermal homeostasis. Va-ta describes fluids and airs throughout the body including blood circulation, respiratory, and nervous system. Sem-ha is all fluid in the body as saliva, tear, urine, blood, etc. They need to work together, so an imbalance of Tri-Dhatu can cause any illness that affects and manifest in the earth element. The reflection of higher fire (Pitta) in the body affected a high body temperature called “fever”, which affects the skin showing red. In some cases, patients get a fever with papules, blisters, rashes, and diarrhea (Ayuraved-Wittayarai Foundation, 1988). Modern medicine considers fever with these symptoms to be involved in inflammation and infection mechanisms in the body, for example, dengue fever, chikungunya fever, chickenpox, hand and foot, and mouth disease, etc. (Ogoina, 2011). For clinical guideline practice of treatment in TTM, the most formulation is provided and recorded by Thai folk doctors and Thai traditional practitioners based on the Tri-Dhatu theory. The components might be slightly different according to available local herbals. The taste of herbs affected their pharmacological properties especially, for relieving fever usually use bitter, cold, and flavorless as the main constituent in the formula (Prommee et al., 2021).

Despite C. caesius has been reported as a component in the formulation of Thai traditional scriptures, the inscription of Thai historical pavilion walls and the stone. There is no research on their scientific reports in medicinal fields. Based on the literature review, we designed this research to investigate the preparation and purpose of using C. caesius in the formulation of Thai traditional medicine textbooks (Ayurvedic school, 2016). The results lead to a study on the pharmacological activities of their properties which include antioxidants, anti-inflammation, antimicrobials, and cytotoxicity. Additionally, the chemical constituents of the extract were also investigated by the Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) technique.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material and preparation of extract

Calamus caesius wood was purchased from Charoensuk Osod, a Thai herbal medicinal store in Nakorn Pathom province, Thailand. It was authenticated and deposited at the Thai traditional medicine herbarium, under the Thai Traditional medicine research institute, Ministry of public health of Thailand. The voucher specimen is TTM-c No. 1000721. Dried wood of C. caesius was ground and extracted using maceration and decoction following the previous study (Dechayont et al., 2021). All extracts have calculated the percentage of yield (%w/w) and were kept at −20 °C until further use.

2.2 Chemicals and reagents

DPPH and BHT were purchased from Fluka, Germany. ABTS, Trolox, potassium persulfate, DMSO, LPS, MTT, acetic acid, phosphoric acid, N-(1-naphthyl) ethylenediamine dihydrochloride, sulfanilamide, and resazurin sodium salt were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Ferric chloride was purchased from Loba Chemie, India. RPMI 1640 Culture Medium, FBS, trypan blue stain 0.4%, and trypsin-EDTA were obtained from Gibco, USA. Hydrochloric acid and isopropanol were obtained from RCI Labscan, Thailand. PBS was provided by Biochrom, Germany. Nutrient agar and Mueller Hinton broth were purchased from Difco, USA. Amoxicillin and gentamicin were purchased from TCI, Japan.

2.3 Evaluation of antioxidant activities

2.3.1 DPPH radical scavenging assay

The DPPH solution at concentration 6 × 10−5 M was freshly prepared in absolute ethanol and protected from any light. Samples of stock at 1 mg/mL were prepared in a serial dilution (at least 4 concentrations). The ethanol extracts were prepared in absolute ethanol, the water extracts were prepared in distilled water. The 100 μL of sample solutions were added in 96 well-plates mixed with DPPH solution equally and put in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. BHT was prepared as same as the sample, as a positive control. The absorbance was measured at 520 nm using a microplate reader (Biotek, USA). The percentage of radical scavenging inhibition was calculated by the formula below (Phuaklee et al., 2021).

A dose–response curve was created from the percentage of inhibition and calculated the EC50 using GraphPad software.

2.3.2 ABTS radical cation decolorization assay

The mixing of ABTS at concentration 7 mM with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate in deionized water was prepared and placed in the dark at room temperature for 12–16 h to generate the ABTS reagent (Re et al., 1999). It was diluted with deionized water to obtain an OD absorbance value of 0.700 ± 0.020 at wavelength 734 nm. The sample was dissolved in an appropriate solution as the ethanol extract in absolute ethanol and water extract in distilled water then prepared in five concentrations by serial dilutions technique. The 20 μL of sample solution was added in 96 well-plates mixed with the ABTS reagent 180 μL. The absorbance was measured 6 min later. The scavenging of the sample was calculated in percentage by this formula and generated the IC50 value by using GraphPad 4.0 software.

2.3.3 Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay (FRAP)

The reducing powers of our extract can reflect their antioxidant activity by using a modified FRAP assay (Benzie and Strain, 1996). Concisely, freshly mixing of three solutions by 300 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 3.6), 10 mM TPTZ solution in 40 mM HCl solution, and 20 mM ferric chloride (FeCl3) solution in proportions of 10:1:1 (%v/v/v) was FRAP reagent. The 20 μL of sample solution (1 mg/ml) was added to 96 well plates. FRAP reagent was warmed in a water bath at 37 °C for 4 min before it (180 μL) was added to each well. After 8 min of mixing reaction, the absorbance was measured at 593 nm. Trolox and ferric sulfate were used as a standard to generate a calibration curve for ethanol extract and water extract, respectively. The results are expressed as ferrous ion equivalent or relative to a standard.

2.4 Evaluation of Anti-inflammatory activity

2.4.1 Nitric oxide inhibitory effect and MTT assay

The methodology of nitric oxide inhibition by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induced from murine macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7) was evaluated as previously reported (Prommee et al., 2021). Briefly, the density of 1 × 105 cells/well was placed into 96 well plates and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h to adhere. Freshly media with LPS (final conc. 5 ng/mL) was replaced with the test sample in various concentrations (max. 100 μg/mL) in equal volume and incubated. After 24 h, the supernatant nitrite was transferred into new 96 well-plates and evaluated by the Griess reagent. MTT assay was also evaluated to confirm cell viability which wasn’t affected by our extracts. MTT solution was prepared at a concentration of 5 mg/mL in PBS added to the 96 well plate testing and placed in the incubator for 4 h. The excess supernatant was removed, then added 0.04 M HCl in isopropanol to dissolve the formazan product. The absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 570 nm. The percentage of inhibition and IC50 values were calculated using a formula and GraphPad software. In addition, cell survival was also calculated and presented by percentage following a formula.

2.5 Evaluation of cytotoxic activity

2.5.1 Sulforhodamine B (SRB) assay

Human breast cancer cell line (T-47D, ATCC® HTB-133™) and human cervical adenocarcinoma cell line (Hela, ATCC® CCL-2™) cell lines were used in this experiment. The estimated cells density detected by the total protein staining was evaluated based on SRB colorimetric assay following the procedure of Skehan et al. (1990); Juckmeta et al. (2019). The appropriate cell's density was seeded into 96 well plates and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h, then the serial concentration of samples was added. After 72 h of incubation, the supernatant in plates was rinsed out and replaced with fresh media. The sample plates were placed in the incubation for 72 h (the recovery period) before fixing them with 10% trichloroacetic acid and stained with SRB. The excess dye was removed, and the protein-stained was dissolved in 10 mM Tris base solution. The absorbance was measured at 492 nm. The percentage of inhibition and IC50 values were analyzed using a formula and GraphPad software.

2.6 Evaluation of antimicrobial activity

2.6.1 Microorganisms

Our study used standard microorganisms’ cultures from the National Institute of Health of Thailand, including Staphylococcus aureus ATCC25923, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ATCC20651, Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC19615, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC9097, and Candida albicans ATCC90028. The antimicrobial activities were tested using the disc diffusion method, minimum inhibitory concentration, and minimum bactericidal concentration.

2.6.2 Disc diffusion method

The disc diffusion method was performed as in the previous study (Dechayont et al., 2021). The ethanol extract (conc. 5 mg/disc) and water extract (1 mg/disc) were applied on a paper disc of 6 mm diameter and dried before testing. The 0.5 McFarland of inoculum was adjusted before being spread over an agar plate; MHA (S. aureus, MRSA, and P. aeruginosa), MHA with 5% sheep blood (S. pyogenes), and SDA (C. albicans). The air-dried sample discs were placed on the inoculum. The zone of inhibition was measured after incubating at 37 °C for 24 h (all bacteria) and 48 h (only C. albicans). Amoxicillin and gentamicin (conc. 10 μg/disc) were positive controls. The mean value of the three replicates measuring is shown in Table 3.

2.6.3 Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC)

The lowest concentration that can inhibit visible microbial growth (bacteriostatic activity) called MIC was determined using the colorimetric resazurin microtiter plate-based antibacterial assay (Sarker et al., 2007). All microorganisms have been grown in their appropriate conditions before being transferred to media broth. For testing, they were adjusted to 0.5 McFarland by the McFarland densitometer. Bacteria suspension and sample in a ratio 1:1 was transferred into each well of the 96-well plate and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h (all bacteria) and 48 h (only C. albicans). A resazurin solution, blue dye (1 mg/mL) was added into each well and incubated for 3 h. The lowest concentration with no change of resazurin color was determined as MIC value. After that, all concentrations with blue color were transferred onto nutrient agar and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The lowest concentration with no growth of bacteria was recorded as MBC. All bacteria and fungi were performed in triplicate. The MIC and MBC values were reported as mg/mL.

2.7 Statistical analysis

All the experiments were conducted in triplicate. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. The IC50 value and statistical significance with p < 0.05 were calculated using one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test using the GraphPad software.

2.8 Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis

The chemical composition of both ethanol extract (CCE) and water extract (CCW) of C. caesius were investigated by Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS) technique. Scion 436-GC model coupled with a single quadruple mass spectrophotometer comprising of a CP-8410 autosampler with a fused silica capillary column SCION-5MS (5% phenyl/95% dimethyl polysiloxane) 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μM run on helium gas with a flow rate of 1 mL/min (Konappa et al., 2020). The sample (10 μL) was injected into the capillary column and was run for 60 min throughout the experiment. The initial temperature was maintained at 80 °C and gradually increased up to 250 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min. (until 38 min.) and finally raised to 280 °C at a rate of 20 °C/min. The components' identification was confirmed by comparing the mass spectra with reference data from the National Institute Standard and Technology (NIST) library.

2.9 In silico – Molecular docking analysis

Molecular docking studies were using PyRx 0.8 and BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2021 software programs. The available 3D configuration compounds found from both ethanol and water extracts of C. Caesius were retrieved from PubChem as ligands in these studies (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The force field and optimization with the lowest energy of ligands were prepared for docking. The crystal structures of receptor proteins, tyrosinase from Bacillus megaterium (3NM8) and NADPH oxidase from Lactobacillus sanfranciscensis (2CDU) were retrieved from the Protein Databank, RCSB PDB (https://www.rcsb.org). The proteins were processed by removing ligands, and water molecules (H20) and then adding polarity. PyRx was used to dock 26 compounds derived from CC into the target sites. Nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) and dextro-methorphan (DEX) were used as the positive control of 3NM8 and 2CDU proteins, respectively. The results are expressed in the binding affinities (kcal/mol), the number of interactions, and the types of interaction. Docking effects were considered when the binding energy values were less than those of NDGA and DEX to the target proteins. Ligand interaction and visualization were carried out via BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2021.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Analytical a literature review of Thai traditional scriptures

Thai medicinal textbooks, gathered from many local and royal scriptures, record knowledge of traditional medical management and treatment throughout the history. The principle of medicinal materials in Thai medicinal formulations includes plants, animals, and elements. The medicinal properties of C. caesius have also been reported in several scriptures used for a similar purpose to reduce heat thereby balancing temperature from fever in the body. The Thai medicinal textbook named “Paet-Saat- Song-Kroh (Thai word)” combined various Thai scriptures, including That Wi Phang, Pra Thom Jinda, Maha Chotarat, Artisan, and Ya-Taret scriptures, etc (Ayurvedic school, 2016; Ayuraved-Wittayarai Foundation, 1988; Mulholland, 1979). Moreover, other local medicinal textbooks from Wat-Pho have also been reported (Phisal and Phisal, 1917). C. caesius was used as part of the thirty formulas from Thai scriptures, pavilion walls, and the inscription stones. All formulas were conveyed as ingredients, methodology for preparation which were related chemical constituents, and their properties shown in Table 1. Remarkably, many formulations can cure similar ailments depending on the difference in locations and herbal diversity. Various liquids are added to prepare a specific purpose based on properties like Traditional Chinese medicine and Ayurveda beliefs. For example, rice water helps to cure fever, relieve faintness, and diuretics (Ayurvedic school, 2016). In Ayurveda, varieties of rice were also used for cooling effect, reducing fever and blood pressure, relieving pimples and small boils in infants (Chaudhari et al., 2018). Flower water has a cool scent that helps to relieve fever and fatigue and nourish the heart (Ayurvedic school, 2016). Sandalwood is known as an anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, and anti-proliferative agent (Moy and Levenson, 2017). It has also been used in Ayurveda by ground into a paste and applied on local inflammations, skin diseases, and on the forehead during fever. Animal bile has a bitter and mao bua taste that helps nourish the blood and bile, treat fever, and increase appetite (Mulholland, 1979). The animal biles of goat, pig, dog, crow, raven, python, and black snake were important drugs in traditional Chinese medicine. Python bile was used for biliary colic disease, infantile malnutrition, infectious skin and eye diseases, gingivitis, and high fever in children (Wang and Carey, 2014).

No.

Scripture /other resources

Formula name, page

Components

%Ratio

(plants/animals/elements)%CC in formula

Preparation before use

Properties

1

That Wi Phang

Unnamed1, 164

10

68.75/ 31.25/ -

6.25

ground to be a powder, dissolved in a hot water, some borneol was added before eat.

heats the body throughout the limbs

2

Jak kra wan fah krob, 175

65

78.46/ 16.92/ 4.62

1.54

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick, animal bile was added properly before eat.

antipyretic, cure abscess

3

Pra Thom Jinda

Nan ta Krai wad, 4

26

76.92/ 19.23/ 3.85

3.85

some flower water was added to the herbal powder for prepared to a stick, for edible and topical use.

relieving seizures in children and adults

4

Thep mong khol, 19

23

52.18/ 34.78/ 13.04

4.35

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick.

relieve blisters in the mouth (Infants under 3 months old)

5

Unnamed2, 59

7

57.14/ 42.86/ -

14.29

ground to be a powder, used as a powder or the herbal powder was prepared to a stick.

relieve symptoms of granules on the body, diarrhea (infants from 3 days of age to 1 year and 6 months)

6

Unnamed3, 452

3

100.00/ -/ -

33.33

all herbals were rubbed with python oil for topical use.

antipyretic, antiemetics, antidiarrhea in children

7

Kae sang lohn long pai tam thong, 473

8

75.00/ 25.00/ -

12.50

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick, dissolved in water before eat.

antipyretic, antiemetics, antidiarrhea

8

In ta john, 528

15

66.67/ 26.67/ 6.67

6.67

Areca catechu L. water was added in the herbal powder for prepared to a stick.

antipyretic, antiemetics, antidiarrhea in children

9

Loam Tab Dab Pit, 537

12

83.33/ 16.67/ -

8.33

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick, dissolved in alcohol before eat.

antidiarrhea in children (5–12 years old)

10

Kae sang daeng sang fai, 539

17

58.82/ 41.18/ -

5.88

python bile was added in the herbal powder for prepared to a stick.

antipyretic, antiemetics, antidiarrhea in children

11

Ma ha wong, 547

48

62.50/ 36.07/ 1.43

1.43

alcohol was added in the herbal powder for prepared to a stick.

relieve hiccups in children and adults

12

Chan Pid Ruea, 548

22

86.36/ 4.55/ 9.09

4.55

some of animal fangs water was added in the herbal powder for prepared to a stick.

antipyretic, antidiarrhea

13

Kwad sang kho, 575

6

16.67/ 66.66/ 16.67

16.67

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick.

antipyretic, relieve body rash in children

14

Unnamed4, 580

11

100.00/ -/ -

9.09

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick, for edible and topical use.

relieve white pathes in the mouth, throat, cheekbones, or on the tongue (newborns to children up to 5 years and 6 months)

15

Thep mong khol, 600

22

50.00/ 31.82/ 18.18

4.55

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick.

relieve symptoms of granules on the body, diarrhea, vomit, thirsty, cough, inedible

16

Jud lah sang ka dook, 609

7

28.58/ 57.13/ 14.29

14.29

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick, dissolved in lime before eat.

relieve blisters in the mouth (Infants under 3 months old)

17

Unnamed5, 609

10

90.00/ 10.00/ -

10.00

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick, dissolved in flower water before eat or apply on skin.

relieve seizures in babies

18

Maha Chotarat

Unnamed6, 148

17

88.24/ 5.88/ 5.88

5.88

ground to be a powder, dissolved in rice water before eat.

prevent liver damage, relieve hiccups and vomiting

19

Thep ni mit, 159

33

87.74/ 3.77/ 8.49

3.77

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick, dissolved in wood water with some borneol before eat.

relieve joint and bone aches before menstruation

20

Atisan

Pra sa chan yai, 900

27

81.49/ 14.81/ 3.70

3.70

Sandalwood equal all components ground to be powder, five-part of pomegranate water was used for prepared a stick, rubbed with sandalwood water before eating.

antipyretic, antiemetics, antidiarrhea in children

21

Pra sa chantara monthol, 904

22

81.81/ 13.64/ 4.55

4.55

Sandalwood equal all components ground to be powder, prepare as stick for rub with flower water.

22

Pra sa chan, 912

20

85.00/ 10.00/ 5.00

5.00

23

Ya-Taret

Unnamed7, 962

27

100.00/ -/ -

3.70

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick, dissolved in rice water before eat.

antipyretic

24

Unnamed8, 964

4

100.00/ -/ -

25.00

the herbal powder was prepared to a stick.

25

Unnamed9, 990

5

80.00/ 20.00/ -

20.00

the herbal powder was dissolved in alcohol before eat.

relieve headache

26

PW name guardian spirit of a newborn baby No.46

Unnamed10, 158

10

60.00/ 40.00/ -

10.00

all equal components are ground to powder, dissolved in alcohol before eating.

relieve symptoms of granules on the body (infants 3 months)

27

stone inscription

Unnamed11, 173

7

100.00/ -/ -

14.29

all equal components are ground to powder, dissolved in water for eating and bath.

antipyretic

28

Unnamed12, 176

23

69.57/ 30.43/ -

4.35

all equal components are ground and prepared to a stick, dissolved in rice water with some borneol before eating.

29

PW name smallpox or massage plan no.70

Ta-rat-thann-phee-yod-deaw, 225

9

77.78/ 11.11/ 11.11

11.11

all equal components are ground to powder and dissolved in alcohol before applying to the abscess.

cure abscess

30

PW name smallpox or massage plan no.79

Unnamed13, 227

14

50.00/ 50.00/ -

7.14

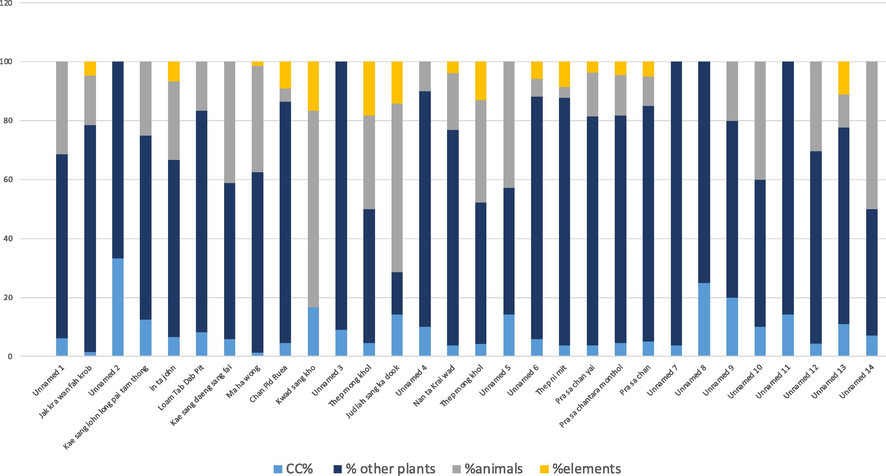

The percentage of C. caesius in each formula was calculated and the grouping of ratio was shown in Fig. 1. There are 19 formulas (64%) that used C. caesius as a small part of recipes with less than 10% ratio. However, C. caesius was used as the principal component of 33.33% in Unnamed3 from Pra Thom Jinda scripture for antipyretic antiemetics, antidiarrheal in children, 25% in Unnamed8 from Ya-Taret scripture for antipyretic, and 20% in Unnamed9 from Ya-Taret scripture for relieving headaches.

The ratio of C. caesius in thirty formulas with the classification of ingredients in a recipe, categorized into plants, animals, and elements.

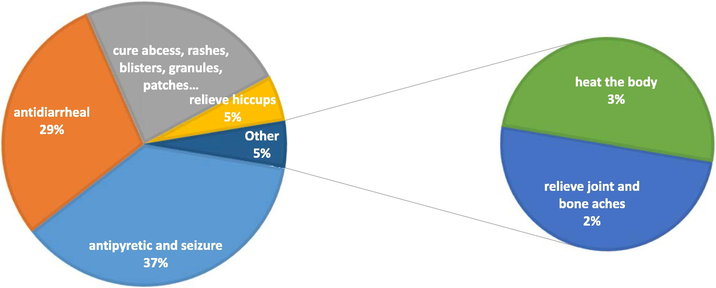

In the preparation of some formula ingredients, which were animal products, elements, or plants were burned before grinding them. Carbonized wood, shell, horn, fang, and the jaw of animals are components in various formulations. All preparations were ground into a powder form before dilution in liquids such as water or alcohol solution. Depending on appropriate purposes, many types of liquid were added to the formulation, such as hot water, rice water, flower water, wood water, and animal bile. The statistical frequency of formula properties (Fig. 2) found that 14 formulas were used for antipyretic and seizure in babies, followed by 11 formulas used for antidiarrheal. Nine formulas used for skin infections (anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory relevance) which showed symptoms are cure abscess, rashes, blisters, etc. Other purposes are to relieve hiccups in children and adults (2 formulas), relieve joint and bone aches (1 formula), and warm the body throughout the limbs (1 formula).

The statistical frequency of formula properties found C. caesius as a component.

C. caesius is no research on its medicinal properties although it normally is a component in the formulas according to Thai traditional medicinal textbooks. Not only dried wood but carbonized C. caesius used as a component found in Kwad sang kho from Pra Thom Jinda scripture and unnamed with 4 components from Ya-Taret scripture (Phisal and Phisal, 1917). Moreover, carbonized C. caesius is an ingredient of the Mahanintangtong remedy in Thailand’s National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM). It was reported antioxidant activity by ABTS and DPPH assay, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial activities of both carbonized C. caesius ethanolic and aqueous extract (Dechayont et al., 2021). As Thai traditional medicines use polyherbal for treating diseases, each herb has its own status in a formula. The main drug is herbs with a major ratio for curing the symptoms. The secondary drug is the herbs for curing any symptoms related to or aiding the main drug through additive or synergistic activities. The ratio in the formula varies depends on the number of herbs in the formulation. The complementary drug is the herbs for enhancing immunity or nourishing the power of the body. Also, the flavoring drug is a small amount in the formulation. It is used to improve the taste and is easy to consume (Ayurvedic school, 2016). C. caesius acts as the main drug with a percentage ratio of more than 15 in four formulas (13.33%). Mostly, C. caesius has been used as a secondary drug for treating antipyretic and antidiarrheal formulations. It implied that C. caesius might show additive or synergistic activities with the main drug in the formulation. Thai traditional medicines use this herb to increase the potential of antipyretic, it displays a mechanism of action to cure diarrhea which is a general symptom from septic patients. Our scientific evidence showed that C. caesius might have the potential to inhibit P. aeuginosa which is related to diarrhea in children (Chuang et al., 2017). Conversely, the small amount of C. caesius in the formulation aimed to use for tonic properties related to our results found that this herb showed leading inhibiting free-radical protecting oxidative stress in the body instead of killing any infectious organisms. So, our preliminary research was conducted based on literature reviews to screen the possibility of C. caesius for medicinal use.

3.2 Effect of antioxidant activities

The result of estimated antioxidant activity using radical scavenging methods of the extracts showed similar activity, CCW showed a higher potential than CCE in all assays (Table 2). CCW exhibited a similar result to CCE in the DPPH radical scavenging activity with IC50 values of 23.33 and 28.77 µg/mL, respectively. In previous study, the carbonized wood of CCE and CCW reported lower antioxidant activity in DPPH assay with IC50 values of 58.93 and >100 µg/mL (Dechayont et al., 2021). Salusu et al., (2018) researched on several part of C. caesius fruits which showed greater DPPH activity ordered as following pericarp (IC50 = 15.34 µg/mL), seed (IC50 = 10.66 µg/mL), and flesh (IC50 = 8.80 µg/mL). In ABTS assay, CCW exhibited better results with IC50 value of 32.15 µg/mL than CCE (IC50 = 56.75 µg/mL). However, the positive control, BHT showed the best one with an IC50 value of 5.66 µg/mL. Amount of FRAP values calculated as standard equivalent from the calibration curve as linear regression formula; y = mx + c, R2 = 0.999. Interestingly, the results of CCW represented two-fold higher than CCE with FRAP values of 144.47 and 73.23 mg standard equivalent/g, respectively. Regarding results of the dried stem of Calamus quiquesetinervius was isolated compounds and investigated antioxidants by Chang et al., (2010a). EtOAc fraction of C. quiquesetinervius ethanol extract revealed highest antioxidant possibility in total polyphenols (273.5 mg/g gallic acid eq.) and DPPH assay (IC50 = 21.9 µg/mL) led to a purified active compound. Only Quiquelignan E from isolated 8 compounds showed stronger OH and O2 free radical scavenging powers with IC50 value of 6.2 and 53.8 µg/mL while Trolox, a positive control remained the best (4.4 and 32.8 µg/mL, respectively). In summary, both CCE and CCW showed strong antioxidant activities in three different assays.

Code name

Extraction

%Yield

Antioxidant activity

DPPH

EC50 ± SEM

(µg/mL)ABTS

EC50 ± SEM

(µg/mL)FRAP

(mg Trolox equivalent/g)

CCE

EtOH, maceration

5.54

28.77 ± 3.87*

56.75 ± 0.91*

73.23 ± 2.49

CCW

Water, decoction

9.80

23.33 ± 2.48*

32.15 ± 3.65*

144.47 ± 6.77

BHTa

–

–

13.72 ± 2.08

5.66 ± 0.26

–

Sample

Anti-inflammatory activity

Cytotoxic activity

IC50 ± SEM (µg/mL)

IC50 ± SEM (µg/mL)

%Survival

(conc. 100 µg/mL)T47D

CCL-2

CCE

>100

97.46 ± 6.15

>100

>100

CCW

>100

106.02 ± 3.16

>100

>100

3.3 Effect of anti-inflammatory activity in vitro

Neither CCE nor CCW had an inhibitory effect on nitric oxide production in RAW264.7 cell line with an IC50 values of greater than 100 µg/mL. The cell viability at a concentration of 100 µg/mL was more than 97%. All extracts did not show cytotoxicity in RAW264.7 cell line using MTT assay. Similarly, the extract of C. caesius carbonized showed inhibitory effects on NO, TNF- , and IL-6 production with IC50 values > 100 µg/mL. It also showed no toxicity on macrophage cell lines (Dechayont et al., 2021). Other researchers studied suppressing LPS-stimulated production of nitric oxide (NO) of isolated compounds from C. quiquesetinervius. Chang et al. (2010b) revealed phenylpropanoid glycosides named Quiquesetinerviuside D and E exhibited potent activity with IC50 values of 9.5 and 9.2 µM while a positive control, quercetin showed an IC50 value of 34.5 µM. Quiquelignan D and F had anti-inflammatory potency 2.7 to 4.5-fold higher compared to quercetin in RAW264.7 cell lines (Chang et al., 2010a). Carapanolide J, limonoid compound from C. guianensis showed similar inhibitory activities compared to positive control L-NMMA with non-toxicity (Dias et al., 2023). Total saponin compound at the concentration in the range of 6.25 to 25 µg/ml from Dioscorea nipponica showed a dose-dependent significant reduce the level of NO on the RAW 264.7 cell lines (Chang et al., 2023). Nonetheless, the numerous phytochemical constituents found from C. caesius ethanol extract such as heptadecane (Kim et al., 2013), n-hexadecanoic acid (Aparna et al., 2012), 9(E),11(E)-conjugated linoleic acid (Lee et al., 2009), β-Sitosterol (Loizou et al., 2010) and glutinol (Adebayo et al., 2017) had reported anti-inflammatory in various studies.

3.4 Effect of SRB cytotoxic activity

Our results revealed that the ethanol and water extracts of C. caesius wood at concentrations of 50 and 100 µg/mL did not show cytotoxic activity against breast and cervical cancer cell lines (IC50 > 100 µg/mL). The percentage of cell viability was more than 90 in both cell lines. From Thai traditional medicine wisdom, Thai doctors have been using this herb in the formula for treating pyretic and diarrheal. The main action of this herb is to support inhibiting free radicals and antimicrobial which is not used to inhibit cancer cells directly. Although there is no research on the cytotoxic activity of C. caesius, some research in the same genus of Calamus was reported. Yu et al., (2008) informed that the methanol extract of Calamus ornatus tender shoots and isolated steroidal saponin compound 2, 3 inhibited cell proliferation of breast (MCF7), CNS (SF-268), lung (NCI-46), colon (HCT-116) and gastric (AGS) cancer cell lines. Thakur et al., (2017) presented that the methanolic supernatant and methanolic precipitate of Calamus tenuis shoots, MSCT and MPCT, had potent against lung carcinoma (A549) and breast carcinoma (MCF7) cell lines. Besides, some chemical constituents in these extracts were reported to have cytotoxicity. β-sitosterol, a phytosterol that is present in the plant cell membrane. Recently, Alvarez-Sala et al., 2019 reported that β-sitosterol displayed cytotoxicity against the HeLa cancer cell line. The mechanism of this compound is an elevated level of p53 mRNA and a reduced level of oncogenic HPV E6. Also, Vundru et al., (2013) showed that β-sitosterol treatment led to G1 arrest in human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells corresponding to reduced levels of cyclin D1 and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) and increased levels of p21/ Cip1 and p27/Kip1 proteins involved in inhibiting the kinase activity of CDK. Furthermore, lupeol and campesterol were reported to inhibit cancer cell lines. Lupeol also showed cytotoxic against Hela, KB, MCF-7, and A549 cell lines (Bednarczyk-Cwynar et al., 2016). Moreover, Kang et al., (2013) supported that lupeol reduced the viability of HeLa cells, and campesterol displayed to inhibit MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer (Awad et al., 2000). Although, the phytochemicals of CC showed the possibility of anti-inflammatory and anticancer in several compounds. Both extracts showed no potential therapeutic effect on the chronic inflammatory mechanism and cytotoxicity against woman's cancer cell lines. It suggests that the quantity of compounds may affect their biological activity.

3.5 Effect of antimicrobial activity

The antimicrobial activity against gram-positive, gram-negative bacteria and gram-positive fungus was reported in the inhibition zone, MIC, and MBC values of the extract which are shown in Table 4. None of extracts demonstrated anti-microbial effects against C. albicans. The extract from C. caesius, especially ethanol extract, represented a productive inhibition activity against S. aureus, S.aureus MRSA, P.aeruginosa, and S.pyogenes. Our results supported Thai traditional doctors’ use of C. caesius to treat fever from bacteria. This data is the first report on C. caesius. Furthermore, some chemical constituents influence inhibiting bacteria. Triazole rings in several compounds including Triadimefon, Triazolam, Ribavirin, Fluconazole, and Tazobactum displayed antiviral and antimicrobial activities (Al-Ghulikah et al., 2023). Benzothiazole is a heterocyclic compound that has also been reported in the field of antimicrobial activity (Alheety et al., 2021). Besides, the silver nanoparticle ions with benzisothiazolinone can cause uncontrolled regulation of cell permeability that results in bacterial cell death (Alheety et al., 2019). Heterocyclic sulfur-containing ligands (1-Phenyl-1H-tetrazole-5-thiol) exhibited C. albicans and A. niger (Al-Janabi et al., 2020). Furaneol has been well-known as the main aroma compound that showed antimicrobial activities against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (Sung et al., 2006). Previous studies have reported the antibacterial activity of heptadecane to possess potent activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria (Naeim et al., 2020). Also, Vanitha et al., (2020) investigated the antimicrobial activity of heneicosane against S. pneumoniae, M. tuberculosis, B. cereus, S. enteritidis, A. baumannii, and A. fumigatus. The results showed that heneicosane at 10 μg/mL exhibited S. pneumoniae with a maximum zone of inhibition (31 mm), followed by M. tuberculosis(28 mm), B. cereus(27 mm), S. enteritidis(26 mm) and A. baumannii(24 mm), respectively. For the antifungal activity, heneicosane at the same concentration also exhibited A. fumigatus excellent activity (29 mm). Stigmasterol and β-Sitosterol, are known to possess antimicrobial properties. Several research claimed that Stigmasterol had the potential to inhibit S. aureus, B. subtilis, E. coli and C. albicans (Odiba et al., 2014; Yusuf et al., 2018). β-Sitosterol has exhibited antimicrobial activity against S. aureus, B. subtilis, and K. phemoniae with the zone of inhibition of 27 mm, 34 mm, and 26 mm, respectively (Alawode et al., 2021). Simultaneously, diacetyl and campesterol displayed antimicrobial activity (Lanciotti et al., 2003; Achika et al., 2020). These major compounds may be responsible for antibacterial activity against S.aureus, S.aureus MRSA, P.aeruginosa, and S.pyogenes.

Sample

Antimicrobial activity showed inhibition zone/ MIC/ MBC

(mm, mg/ml, mg/ml)

S.aureus

S.aureus MRSA

P.aeruginosa

S.pyogenes

C.albicans

CCE

6/ 0.625/ 0.625

6/0.625/ 0.625

0/ 0.625/ >5

7/ 0.313/ 0.625

0/ >5/ >5

CCW

0/ 0.625/ 0.625

0/ 0.625/ 1.25

0/ 5/ >5

0/ >5/ >5

0/ >5/ >5

Amoxicillina

NT

NT

NT

35/ 0.016/ 0.025

NT

Gentamicina

15/ 0.195/ 0.195

10/ >200/ >200

12/ 0.39/ 0.39

NT

NT

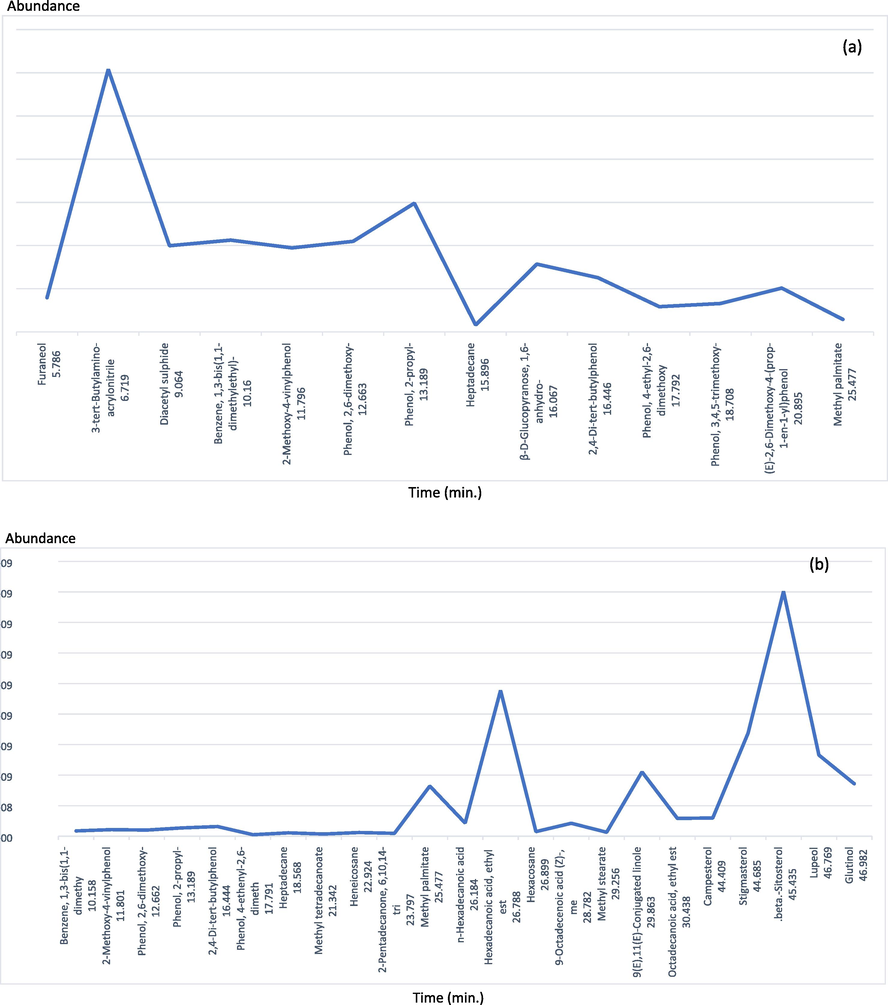

3.6 The profile of GC–MS

The GC–MS chromatogram of CCW and CCE demonstrated a total of 14 and 24 peaks corresponding to the phytochemical constituents shown in Table 5 and Table 6. The data were recognized by molecular weight relating the name of the compound and percentage of peak area to that of the known compounds provided by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library as shown in Fig. 4. The 14 chemical constituents of CCW with peak area were 3-tert-Butylamino-acrylonitrile (25.81%), phenol, 2-propyl- (12.65%), benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- (9.03%), phenol, 2,6-dimethoxy- (8.90%), diacetyl sulphide (8.47%), 2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol (8.26%), β-D-glucopyranose, 1,6-anhydro- (6.67%), 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol (5.33%), (E)-2,6-dimethoxy-4-(prop-1-en-1-yl)phenol (4.31%), furaneol (3.37%), phenol, 3,4,5-trimethoxy- (2.80%), phenol, 4-ethyl-2,6-dimethoxy (2.49%), hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester (1.23%), heptadecane (0.68%), respectively. The major chemical constituents of CCW revealed 3-tert-butylamino-acrylonitrile which was shown antifungal activity in the previous study (Ayed et al., 2021). The chemical constituents of CCW were shown several bioactivities for example 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol exhibited antioxidant in TBARS assay (Yoon et al., 2006), heptadecane exhibited a potent anti-oxidative effect and suppressed NF-kB signal pathway in aged rats (Kim et al., 2013), hexadecenoic acid methyl ester or methyl palmitate showed high antimicrobial effect against clinical pathogenic bacteria (Shaaban et al., 2021) and inhibited fungal pathogen cause of leaf spot and rot diseases (Abubacker and Deepalakshmi, 2013). Note: SI no; serial number, MW; Molecular weight, (-); not detected, (--); not reported. Note: SI no; serial number, MW; Molecular weight, (-); not detected, (--); not report.

SI no.

RT

(min.)

CAS

Name of the compound

R. Match

Molecular formular

Molecular weight

%Peak area

Biological and pharmacological activities

1

5.786

3658-77-3

Furaneol

818

C6H8O3

128.13

3.37

Flavoring agent (Buechi et al., 1973)

2

6.719

77376-84-2

3-tert-Butylamino-acrylonitrile

–

C7H12N2

124.18

25.81

Antifungal (Ayed et al., 2021))

3

9.064

3232-39-1

Diacetyl sulphide

967

C4H6O2S

118.15

8.47

--

4

10.16

1014-60-4

Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-

930

C14H22

190.32

9.03

--

5

11.796

31853-85-7

2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol

921

C9H10O2

150.17

8.26

Aromatic substance, flavoring agent

(EU Food Improvement Agents, 2020)

6

12.663

91-10-1

Phenol, 2,6-dimethoxy-

955

C8H10O3

154.16

8.90

Flavoring agent (Yannai, 2012)

7

13.189

644-35-9

Phenol, 2-propyl-

903

C9H12O

136.19

12.65

--

8

15.896

629-78-7

Heptadecane

887

C17H36

240.46

0.68

Anti-inflammatory (Kim et al., 2013)

9

16.067

498-07-7

β-D-Glucopyranose, 1,6-anhydro-

919

C6H10O5

162.14

6.67

--

10

16.446

96-76-4

2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol

955

C14H22O

206.32

5.33

Antioxidant (Yoon et al., 2006)

11

17.792

-

Phenol, 4-ethyl-2,6-dimethoxy

924

C10H14O3

182.21

2.49

Phenolic compound

(Tymchyshyn and Xu, 2010)

12

18.708

642-71-7

Phenol, 3,4,5-trimethoxy-

900

C9H12O4

184.18

2.80

--

13

20.895

20675-95-0

(E)-2,6-Dimethoxy-4-

(prop-1-en-1-yl)phenol912

C11H14O3

194.22

4.31

--

14

25.477

112-39-0

Methyl palmitate

948

C17H34O2

270.45

1.23

Antibacterial, Fatty acid (Shaaban et al., 2021),

Antifungal (Abubacker and Deepalakshmi, 2013)

SI no.

RT

(min.)CAS

Name of the compound

R. Match

Molecular formular

MW

%Peak area

Biochemistry and pharmacology

1

10.158

1014-60-4

Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-

930

C14H22

190.32

0.62

--

2

11.801

31853-85-7

2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol

921

C9H10O2

150.17

0.76

Aromatic substance, flavoring agent (EU Food Improvement Agents, 2020)

3

12.662

91-10-1

Phenol, 2,6-dimethoxy-

955

C8H10O3

154.16

0.71

Flavoring agent (Yannai, 2012)

4

13.189

644-35-9

Phenol, 2-propyl-

903

C9H12O

136.19

0.96

--

5

16.444

96-76-4

2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol

955

C14H22O

206.32

1.12

Antioxidant (Yoon et al., 2006)

6

17.791

-

Phenol, 4-ethyl-2,6-dimethoxy

924

C10H14O3

182.21

0.18

Phenolic compound (Tymchyshyn and Xu, 2010)

7

18.568

629-78-7

Heptadecane

887

C17H36

240.46

0.39

Anti-inflammatory (Kim et al., 2013)

8

21.342

124-10-7

Methyl tetradecanoate

910

C15H30O2

242.39

0.25

--

9

22.924

629-94-7

Heneicosane

964

C21H44

296.57

0.43

Antimicrobial (Vanitha et al., 2020)

10

23.797

502-69-2

2-Pentadecanone, 6,10,14-trimethyl-

910

C18H36O

268.47

0.33

--

11

25.477

112-39-0

Methyl palmitate

948

C17H34O2

270.45

5.82

Antibacterial, Fatty acid (Shaaban et al., 2021), Antifungal (Abubacker and Deepalakshmi, 2013)

12

26.184

57-10-3

n-Hexadecanoic acid

955

C16H32O2

256.42

1.52

Anti-inflammatory (Aparna et al., 2012)

13

26.788

628-97-7

Hexadecanoic acid,

ethyl ester907

C18H36O2

284.47

16.91

Palmitic acid ester (Hungund et al., 1988),

Antimicrobial (Krishnaveni et al., 2014)

14

26.899

630-01-3

Hexacosane

950

C26H54

366.70

0.53

Antimicrobial (Rukaiyat et al., 2015)

15

28.782

112-62-9

9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)-, methyl ester

923

C19H36O2

296.48

1.50

--

16

29.256

112-61-8

Methyl stearate

943

C19H38O2

298.50

0.46

Fatty acid (Bancquart et al., 2001)

17

29.863

544-71-8

9(E),11(E)-Conjugated Linoleic Acid

923

C18H32O2

280.50

7.46

Anti-inflammatory (Lee et al., 2009), Anticancer (Kelley et al., 2007)

18

30.438

111-61-5

Octadecanoic acid, ethyl ester

901

C20H40O2

312.53

2.06

--

19

44.409

474-62-4

Campesterol

850

C28H48O

400.68

2.12

Antiangiogenic (Choi et al., 2007)

20

44.685

83-48-7

Stigmasterol

865

C29H48O

412.69

11.98

Anti-osteoarthritic (Gabay et al., 2010), Antiperoxidative and Hypoglycemic (Panda et al., 2009)

21

45.435

83-46-5

β-Sitosterol

895

C29H50O

414.70

28.38

Anti-inflammatory (Loizou et al., 2010)

22

46.769

545-47-1

Lupeol

916

C30H50O

426.71

9.41

Triterpene compound

23

46.982

545-24-4

Glutinol

921

C30H50O

426.70

6.08

Anti-inflammatory (Adebayo et al., 2017)

GC–MS chromatogram showing the peaks and retention time the water extract (a) and the ethanolic extract (b) of C. caesius.

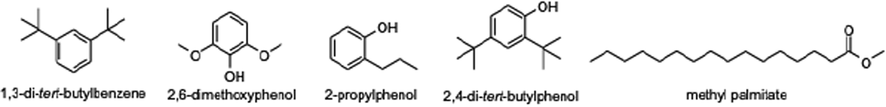

In contrast, the major chemical constituents of CCE were phytosterol compounds such as β-sitosterol and stigmasterol and triterpenoid compound as lupeol. According to the peak areas, seven major phytochemical constituents of C. caesius ethanol extract (CCE) included β-Sitosterol (28.38%), hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester (16.91%), stigmasterol (11.98%), lupeol (9.41%), 9(E),11(E)-conjugated linoleic acid (7.46%), lutinol (6.08%), hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester (5.82%), respectively. An isomer of linoleic acid as 9(E),11(E)-conjugated linoleic acid found in CCE has reported potential anticancer and anti-inflammatory activities (Lee et al., 2009). Interestingly, β-Sitosterol and hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester demonstrated anti-inflammatory and antibacterial activities (Loizou et al., 2010; Krishnaveni et al., 2014) which is related to our study that used a CCE for treating fever and anti-inflammatory disorder. The investigation of CCE revealed the presence of various phytoconstituents, including phenolic compounds and fatty acids as well as CCW. Five compounds found in both ethanol and water extract of C. caesiusshowed in Fig. 3. These bioactive phytoconstituents of CCW and CCE could be responsible for the therapeutic capability of C. caesius prescribed in Thai traditional medicine by following Thai scriptures and textbooks.

The chemical compounds found in both ethanol and water extract of C. caesius.

3.7 Molecular docking analysis

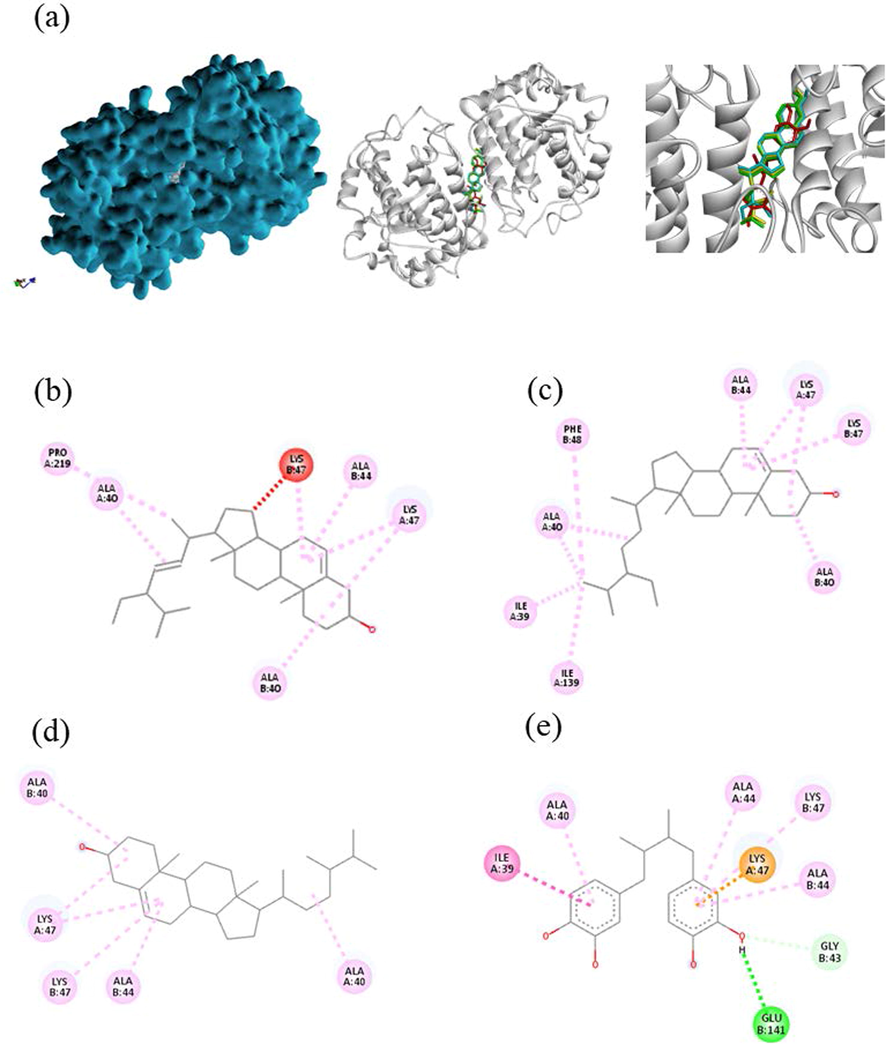

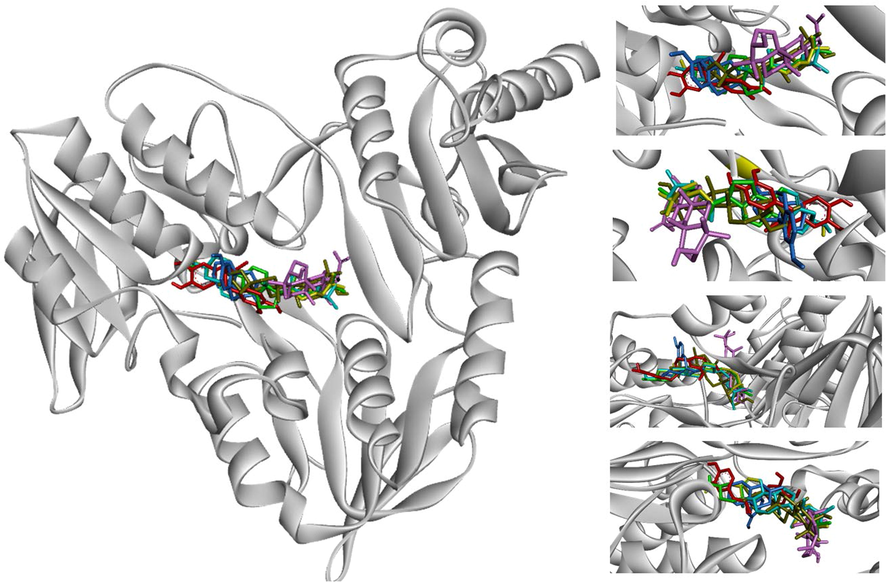

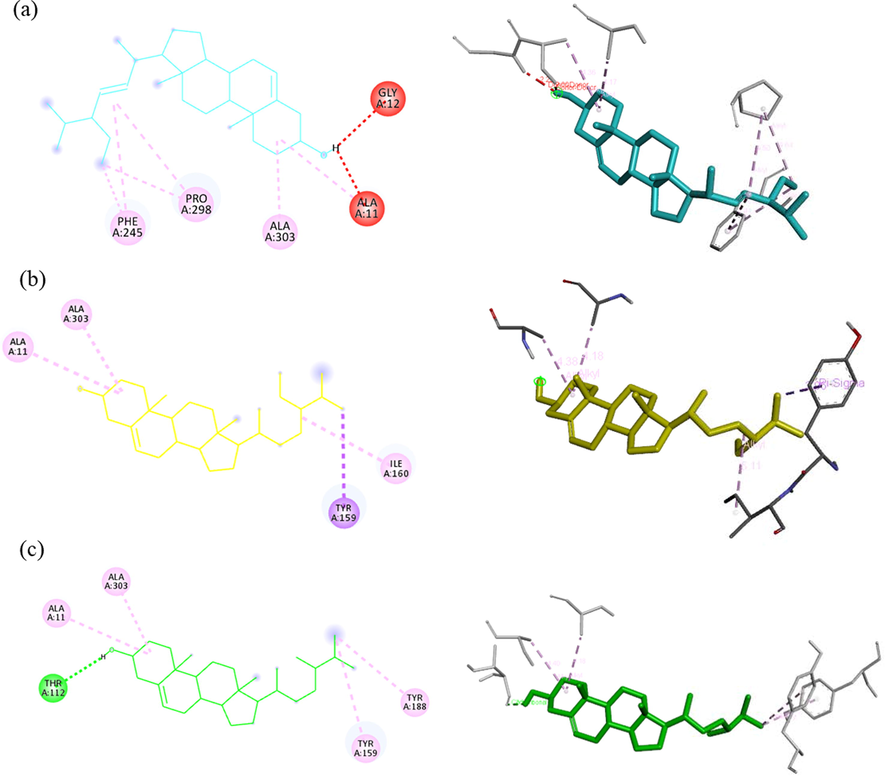

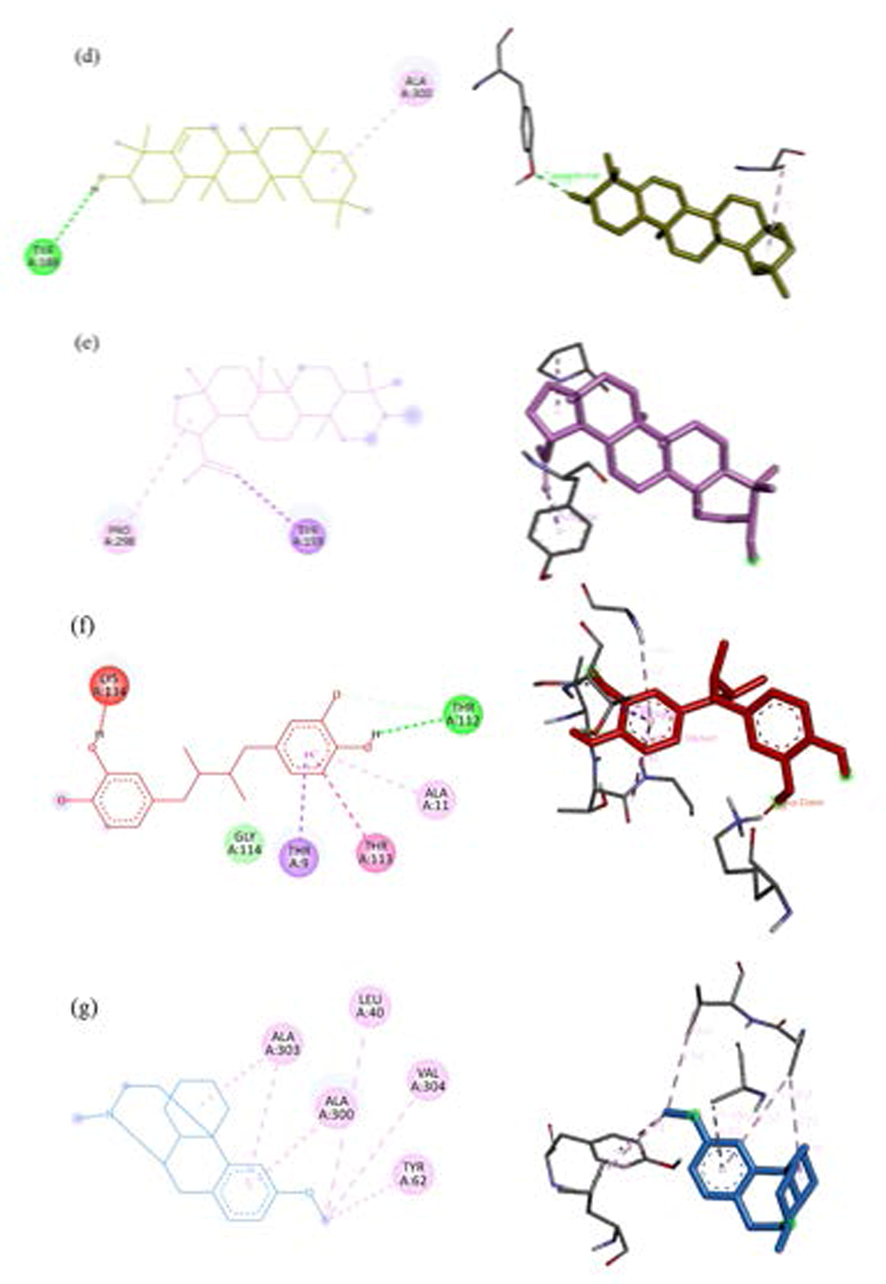

Both ethanol and water extracts of C. Caesius have dominant antioxidant in three free-radical scavenging activities which is interesting to develop as ingredient into the pharmaceutical drugs, food additives and cosmetic industries. The primary function of NADPH oxidase is to produce reactive oxygen species that is regard as important factor to pathogenesis of various diseases such as vascular diseases, cancer, inflammation, CNS diseases, and other degenerative diseases (Maraldi, 2013; Sui et al., 2019). Besides, ROS inducing from UV irradiation lead to induce hyperpigmentation on skin by activating tyrosinase enzyme (Muddathir et al., 2017). For antioxidant in silico, phytochemical constituents from GC–MS analysis were focused on inhibiting properties of these two enzymes. So, the molecular docking approaches of NADPH oxidase and tyrosinase were conceived under budget constraints of research. The active sites of proteins in this study defined from PDB site records via Discovery studio Visualizer 2021. The results of the docking score were reported as binding affinity with kcal/mol (Table 7), the interaction of ligand–protein bonding classified by numbers and types was also shown in Table 8. In addition, an interactive visualization of molecular docking studies represented the hydrophobic and hydrogen bond interactions between ligands and proteins. The different colors performed diverse interactions as following green-hydrogen bonding, pink-alkyl/hydrophobic bonding, and red-unfavorable bonding. In tyrosinase (PBD CID: 3NM8) binding simulation, Nordihydroguaiaretic acid (NDGA) was used as a standard (Al-Salahi et al., 2019) has a docking score of −8.7 kcal/mol in this experiment. Three ligands showed the best efficient docking energy values β-sitosterol with a binding affinity score of −8.3 kcal/mol followed by campesterol and stigmasterol with the same score of −8.3 kcal/mol. Analogous to Ghalloo et al., (2022) research, β-sitosterol revealed a binding affinity score of around −9.0 kcal/mol while Kojic acid (standard) had −5.0 kcal/mol. None of them had hydrogen bond interaction. Stigmasterol and campesterol similarly activate hydrophobic interaction with LYS47, ALA44, and ALA40. In the case of docked NDGA and β-sitosterol, hydrophobic bonds with LYS47, ALA44, ALA40, and ILE39 were also formed but H-bonds interaction with GLU141 was not found in beta-sitosterol (Fig. 5). Similarly, Yousuf et al., (2022) reported campesterol had alkyl bond interaction with ALA155. Based on our results NDGA appeared to bind more strongly to the active site of tyrosinase than beta-sitosterol, campesterol, and stigmasterol, respectively. Docked conformation of seven ligand structures in the binding site of NADPH oxidase (PBD CID: 2CDU) is visualized in Fig. 6. The standard compounds of the 2CDU model were dextromethorphan (DEX) (Farouk et al., 2021) and NDGA with binding affinity score of −7.6 and −7.7 kcal/mol. The candidate compounds had a better affinity of the binding score more than NDGA and DEX. Stigmasterol revealed the greatest docking score (−9.1 kcal/mol) followed by campesterol (−8.7 kcal/mol), β-sitosterol and two triterpenoids, glutinol and lupeol with balanced scores (−8.6 kcal/mol). An interaction of ligands and 2CDU presented by 2D and 3D visualization via BIOVIA Discovery studio was shown in Fig. 7. DEX appears to interact with ALA303 ALA300 LEU40 VAL304 TYR62 with hydrophobic bonding. Phytosterol compounds are stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, and campesterol also formed with ALA303 in the same interaction. In addition, stigmasterol interact the nature ligand (GSH) into the active pocket of NADPH-dependent human carbonyl reductase-1 (hCBR-1) with hydrophobic bonding to VAL96, MET141, TYR193, TRP229 (Andriani et al., 2022). From the list of residues, five interact with NDGA are ALA11, THR113, and THR9 with hydrophobic bonding, THR112 with hydrogen bonding, and LYS unfavorable bonding. Campesterol also interacts with THR112 similar to NDGA interface. Our results discovered the possibility of antioxidant activities of ethanol compounds were phytosterols and triterpenoids from C. caesius.

Compounds

Binding Affinity (kcal/mol)

Tyrosinase

3NM8

NAD(P)H Oxidase

2CDU

(E)-2,6-Dimethoxy-4-(prop-1-en-1-yl)phenol

−7.1

−5.8

2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol

−5.9

−6.3

2-Methoxy-4-vinylphenol

−6.4

−5.5

2-Pentadecanone, 6,10,14-trimethyl-

−7.3

−5.8

2-Propylphenol

−7.0

−5.6

3-tert-Butylamino-acrylonitrile

−5.2

−4.6

9(E),11(E)-Conjugated Linoleic Acid

−7.4

−6.5

Benzene, 1,3-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-

−5.8

−6.5

Beta-Sitosterol

−8.3

−8.6

Campesterol

−8.0

−8.7

Diacetyl sulphide

−4.2

−4.0

Furaneol

−5.6

−5.3

Glutinol

−5.0

−8.6

Heneicosane

−7.0

−4.8

Heptadecane

−6.4

−5.3

Hexacosane

−7.3

−4.9

Hexadecanoic acid, ethyl ester

−6.8

−5.5

Levoglucosan

−5.7

−5.3

Lupeol

−3.1

−8.6

Methyl palmitate

−6.4

−5.5

Methyl tetradecanoate

−6.7

−5.4

n-Hexadecanoic acid

−6.8

−5.4

Phenol, 2,6-dimethoxy-

−5.7

−4.9

Phenol, 3,4,5-trimethoxy-

−6.0

−5.2

Phenol, 4-ethyl-2,6-dimethoxy

−6.4

−5.3

Stigmasterol

−8.0

−9.1

Nordihydroguaiaretic acid, NDGA*

−8.7

−7.7

Dextromethorphan, DEX*

−5.7

−7.6

Interaction type

Enzymes

Ligands

Total number of interaction

Hydrogen bonding

Hydrophobic bonding

Unfavorable bonding

Tyrosinase

Beta-Sitosterol

10

0

10

0

Campesterol

6

0

6

0

Stigmasterol

9

0

7

2

Nordihydroguaiaretic acid

9

3

6

0

NAD(P)H Oxidase

Beta-Sitosterol

4

0

4

0

Campesterol

5

1

4

0

Glutinol

2

1

1

0

Lupeol

2

0

2

0

Stigmasterol

8

0

6

2

Nordihydroguaiaretic acid

6

2

3

1

Dextromethorphan

6

0

6

0

Interaction visualization of four ligands binding 3NM8 with BIOVIA discovery studio - stigmasterol in blue, beta-sitosterol in yellow, campesterol in green, NDGA in red (a), 2D interaction of stigmasterol (b), beta-sitosterol (c), campesterol (d), NDGA (e).

Interaction visualization of seven ligands binding active site of 2CDU with BIOVIA discovery studio- stigmasterol (blue, #55ffff), beta-sitosterol (yellow, #ffff00), campesterol (green, #00ff00), lupeol (light pink, #ffaaff), glutinol (light yellow, #aaaa00), NDGA (red, #ff0000), DEX (light blue, #55aaff).

2D and 3D interaction of 2CDU binding stigmasterol (a), beta-sitosterol (b), campesterol (c), glutinol (d), lupeol (e), NDGA (f), DEX (g) 2D and 3D interaction of 2CDU binding stigmasterol (a), beta-sitosterol (b), campesterol (c), glutinol (d), lupeol (e), NDGA (f), DEX (g).

2D and 3D interaction of 2CDU binding stigmasterol (a), beta-sitosterol (b), campesterol (c), glutinol (d), lupeol (e), NDGA (f), DEX (g) 2D and 3D interaction of 2CDU binding stigmasterol (a), beta-sitosterol (b), campesterol (c), glutinol (d), lupeol (e), NDGA (f), DEX (g).

4 Conclusion

This is the first scientific report on the ethnopharmacological analysis of C. caesius. From Thai traditional formulations in Thai traditional scriptures and Thai medicinal textbooks (TMT), C. caesius was mostly used as a secondary drug in the formula with a percentage ratio in the range of 5 to 14.99 act as a component for antipyretic, antidiarrhea, and cure abscess treatment. Based on GC–MS analysis, the chemical profiles reported the scientific data associated with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial activities. In vitro results of biological activities in this study support that C. caesius displayed antioxidants and antimicrobial activities in the formulas. Furthermore, in silico molecular docking study of phytochemical constituents revealed the phytosterols from ethanol extract are promising antioxidant agents (tyrosinase and NADPH oxidase). According to Thai traditional formulations analysis, C. caesius is used for oral and topical drugs that is supposed to against oxidative stress for immune support in the human body. Hence, our results in vitro and in silico supported C. caesius acts as an antioxidant agent in drug formulas.

Acknowledgments

The authors also thank the Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University, Faculty of Public Health, Naresuan University, the Center for Scientific and Technological Equipment, and the School of Medicine, Walailak University for supporting and providing laboratory facilities, Weerachai Pipatrattanaseree for give advice in silico technique.

Authors’ contributions

TJ conceived and designed most of the experiments. BD, PP, and JC performed most of the experiments. OP and KY carried out cytotoxic activity. NP performed GC-MS analysis and wrote this part. SN and TJ analyzed Thai traditional scriptures, analyzed the remaining data, and wrote the manuscript. TJ performed Molecular docking analysis. TJ, BD, PD reviewed and modified the paper. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Walailak University research grants [grant numbers WU-IRG-64-067, 2021] and the Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat University [grant numbers 2–13/2562, 2019] for providing financial support and equipment used for biological assays.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- In vitro antifungal potential of bioactive compound methyl ester of hexadecanoic acid isolated from Annona muricata Linn. (Annonaceae) leaves. Biosci. Biotechnol. Res Asia.. 2013;10(2):879-884.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Terpenes with antimicrobial and antioxidant activities from Lannea humilis (Oliv.) Sci. Afr.. 2020;10:e00552.

- [Google Scholar]

- First isolation of glutinol and a bioactive fraction with good anti-inflammatory activity from n-hexane fraction of Peltophorum africanum leaf. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med.. 2017;10(1):42-46.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stigmasterol and β-Sitosterol: Antimicrobial compounds in the leaves of Icacina trichantha identified by GC–MS. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci.. 2021;10:80.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of new 1,2,3-triazole linked benzimidazolidinone: Single crystal X-ray structure, biological activities evaluation and molecular docking studies. Arab. J. Chem.. 2023;16(3):104566

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alheety, M.A., Al-Jibori, S.A., Ali, A.H., Mahmood, A.R., Akba ş, H., Karada ğ , A., Uzun, O., Ahmad, M.H., 2019. Ag(I)-benzisothiazolinone complex: synthesis, characterization, H2 storage ability, nano transformation to different Ag nanostructures and Ag nanoflakes antimicrobial activity. Mater. Res. Express. 6, 125071. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/ab5ab4.

- Biogenic silver nanowires for hybrid silver functionalized benzothiazolilthiomethanol as a novel organic–inorganic nanohybrid. Mater. Today:Proceedings.. 2021;43(2):2076-2082.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anti-cancer and anti-fungal evaluation of novel palladium(II) 1-phenyl-1H-tetrazol-5-thiol complexes. Inorg. Chem. Commun.. 2020;121:108193

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant activities and molecular docking of 2-thioxobenzo[g]quinazoline derivatives. Pharmacol. Rep.. 2019;71:695-700.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Apoptotic effect of a phytosterol-ingredient and its main phytosterol (β-sitosterol) in human cancer cell lines. Int J Food Sci Nutr.. 2019;70:323-334.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Andriani1, Y., Mulyani1, Y., Iskandar, Megantara, S., Levita J., 2022. Molecular docking study, antioxidant activity, proximate content, and total phenol of Lemna perpusilla Torr. Grown in Sumedang, West Java, Indonesia. Rasayan J. Chem.15(2), 1182–1189. http://doi.org/10.31788/RJC.2022.1526925.

- Anti-inflammatory property of n-hexadecanoic acid: structural evidence and kinetic assessment. Chem. Biol. Drug Des.. 2012;80:434-439.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of growth and stimulation of apoptosis by beta-sitosterol treatment of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells in culture. Int. J. Mol. Med.. 2000;5:541-546.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal activity of volatile organic compounds from Streptomyces sp. strain S97 against Botrytis cinerea. Biocontrol Sci. Technol.. 2021;31:1330-1348.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ayuraved-Wittayarai Foundation, 1988. Thai traditional medicine textbook (Paet-Saat- Song-Kror), first ed. Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand.

- Ayurvedic school (Chewaka Komaraphat)., 2016. Thai pharmacy textbook, second ed. Foundation for the rehabilitation and promotion of traditional Thai medicine, Bangkok, Thailand.

- Glycerol transesterification with methyl stearate over solid basic catalysts: I. Relationship between activity and basicity. Appl. Catal.. 2001;218:1-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxic activity of some lupeol derivatives. Nat Prod Commun.. 2016;11(9):1237-1238. PMID: 30807009

- [Google Scholar]

- The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem.. 1996;239:70-76.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Syntheses of 2,5-dimethyl-4-hydroxy-2,3-dihydrofuran-3-one (furaneol), a flavor principle of pineapple and strawberry. J. Org. Chem.. 1973;38:123-125.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of extraction process of Dioscorea nipponica Makino saponins and their UPLC-QTOF-MS profiling, antioxidant, antibacterial and anti- inflammatory activities. Arab. J. Chem.. 2023;16(4):104630

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory phenylpropanoid derivatives from Calamus quiquesetinervius. J. Nat. Prod.. 2010;73:1482-1488.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Quiquelignan A-H, eight new lignoids from the rattan palm Calamus quiquesetinervius and their antiradical, anti-inflammatory and antiplatelet aggregation activitie. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2010;18:518-525.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rice nutritional and medicinal properties: A review article. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem.. 2018;7(2):150-156.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of campesterol from Chrysanthemum coronarium L. and its antiangiogenic activities. Phytother. Res.. 2007;21:954-959.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa-associated diarrheal diseases in children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J.. 2017;36(12):1119-1123.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of Mahanintangtong and its constituent herbs, a formula used in Thai traditional medicine for treating pharyngitis. BMC Complement. Med. Ther.. 2021;21:105.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dias, K.K.B., Cardoso, A.L., da Costa, A.A.F., Passos, M.F., da Costa, C.E.F., da Rocha Filho, G.N., Andrade, E.H.d.A., Luque, R., do Nascimento, L.A.S., Noronha, R.C.R., 2023. Biological activities from andiroba (Carapa guianensis Aublet.) and its biotechnological applications: A systematic review. Arab. J. Chem. 16 (4), 104629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104629.

- European union. EU Food Improvement Agents. https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/food-improvement-agents_pl?2nd-language=mt (accessed 15 June 2022).

- Antioxidant activity and molecular docking study of volatile constituents from different aromatic Lamiaceous plants cultivated in Madinah Monawara, Saudi Arabia. Molecules.. 2021;26(14):4145.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stigmasterol: a phytosterol with potential anti-osteoarthritic properties. Osteoarthr. Cartil.. 2010;18(1):106-116.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical profiling, in vitro biological activities, and in silico molecular docking studies of Dracaena reflexa. Molecules. 2022;27(3):913.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Formation of fatty acid ethyl esters during chronic ethanol treatment in mice. Biochem. Pharmacol.. 1988;37(15):3001-3004.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cytotoxicity to five cancer cell lines of the respiratory tract system and anti-inflammatory activity of Thai traditional remedy. Nat. Prod. Commun.. 2019;14(5)

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lupeol is one of active components in the extract of Chrysanthemum indicum Linne that inhibits LMP1-induced NF-κB activation. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e82688.

- [Google Scholar]

- Conjugated linoleic acid isomers and cancer. J. Nutr.. 2007;137(12):2599-2607.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular study of dietary heptadecane for the anti-inflammatory modulation of NF-kB in the aged kidney. PLoS One. 2013;8(3):e59316.

- [Google Scholar]

- GC–MS analysis of phytoconstituents from Amomum nilgiricum and molecular docking interactions of bioactive serverogenin acetate with target proteins. Sci. Rep.. 2020;10:16438.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- GC-MS analysis of phytochemicals, fatty acid profile, antimicrobial activity of Gossypium seeds. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res.. 2014;27(1):273-276.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of diacetyl antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus. Food Microbiol.. 2003;20(5):537-543.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- 9E,11E-conjugated linoleic acid increases expression of the endogenous anti-inflammatory factor, interleukin-1receptor antagonist, in RAW 264.7 cells. J. Nutr.. 2009;139(10):1861-1866.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- β-sitosterol exhibits anti-inflammatory activity in human aortic endothelial cells. Mol. Nutr. Food Res.. 2010;54(4):551-558.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Natural compounds as modulators of NADPH oxidases. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013:271602.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sandalwood album oil as a botanical therapeutic in dermatology. J. Clin. Aesthet. Dermatol.. 2017;10(10):34-39. PMID: 29344319; PMCID: PMC5749697

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-tyrosinase, total phenolic content and antioxidant activity of selected Sudanese medicinal plants. S. Afr. J. Bot.. 2017;109:9-15.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thai traditional medicine: ancient thought and practice in a Thai context. J Siam Soc.. 1979;67(2):80-115. PMID: 11617470

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activity of Centaurea pumilio L. root and aerial part extracts against some multidrug-resistant bacteria. BMC Complement Altern Med.. 2020;20:79.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activity of isolated stigmast5-en-3β-ol (β-Sitosterol) from honeybee propolis from North-Western, Nigeria. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res.. 2014;5:908-918.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fever, fever patterns and diseases called ‘fever’–A review. J. Infect. Public Health.. 2011;4(3):108-124.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thyroid inhibitory, antiperoxidative and hypoglycemic effects of stigmasterol isolated from Butea monosperma. Fitoterapia. 2009;80(2):123-126.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vejsardwanna (Ancient Thai medicinal textbook) 1–5. Bangkok, Thailand: Phisalbannithi; 1917.

- Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-Staphylococcal activities of Albizia lucidior (Steud.) I. C. Nielsen wood extracts. Sci. Asia.. 2021;47:682-689.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antipyretic therapy: physiologic rationale, diagnostic implications, and clinical consequences. Arch Intern Med.. 2000;160(4):449-456.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ethnopharmacological analysis from Thai traditional medicine called Prasachandaeng remedy as a potential antipyretic drug. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2021;268:113520

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic. Biol. Med.. 1999;26(9–10):1231-1237.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activities of hexacosane isolated from Sanseveria liberica (Gerome and Labroy) plant. Adv. Med. Plant Res.. 2015;3(3):120-125.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant assay of the ethanolic extract of three species of rattan Fruits using DPPH Method. J. Trop. Pharm. Chem.. 2018;4:154-162.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microtitre plate-based antibacterial assay incorporating resazurin as an indicator of cell growth, and its application in the in vitro antibacterial screening of phytochemicals. Methods. 2007;42(4):321-324.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activities of hexadecanoic acid methyl ester and green-synthesized silver nanoparticles against multidrug-resistant bacteria. J. Basic Microbiol.. 2021;61(6):557-568.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shim, P.S., Tan, C.F., 1993. Calamus trachycoleus Beccari. In Plant Resources of South-East Asia No 6: Rattans. https://prota4u.org/prosea/view.aspx?id=1955 (accessed 21 February 2022).

- New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. J. Natl. Cancer Inst.. 1990;82(13):1107-1112.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- NADPH oxidase is a primary target for antioxidant effects by inorganic nitrite in lipopolysaccharide-induced oxidative stress in mice and in macrophage cells. Nitric Oxide. 2019;89:46-53.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial effect of furaneol against human pathogenic bacteria and fungi. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol.. 2006;16(3):349-354.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thakur, P. K., 2017. Consumption pattern of Calamus tenuis Roxb. shoots of the forest village natives of Dibrugarh, Assam and investigation of its cytotoxicity activity on cancer and normal cells (A549, MCF7 and L132). Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda (India) ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. 27672400. https://www.proquest.com/openview/af0e2a9822cabea6407ab47c13d5a7c7/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y. (accessed 21 February 2022).

- Liquefaction of bio-mass in hot-compressed water for the production of phenolic compounds. Bioresour. Technol.. 2010;101(7):2483-2490.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heneicosane—A novel microbicidal bioactive alkane identified from Plumbago zeylanica L. Ind. Crop. Prod.. 2020;154:112748

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- β-Sitosterol induces G1 arrest and causes depolarization of mitochondrial membrane potential in breast carcinoma MDA-MB-231 cells. BMC Complement Altern Med.. 2013;13:280.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic uses of animal biles in traditional Chinese medicine: an ethnopharmacological, biophysical chemical and medicinal review. World J. Gastroenterol.. 2014;20(29):9952-9975.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dictionary of Food Compounds with CD-ROM (second ed.). Crc Press; 2012.

- Antioxidant effects of quinoline alkaloids and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol isolated from Scolopendra subspinipes. Biol. Pharm. Bull.. 2006;29(4):735-739.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical profiling, formulation development, in vitro evaluation and molecular docking of Piper nigrum seeds extract loaded emulgel for anti-aging. Molecules. 2022;27(18):5990.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.F., Mulabagal, V., Diyabalanage, T., Hurtada, W.A., DeWitt, D.L., Nair, M.G., 2008. Non-nutritive functional agents in rattan shoots, a food consumed by native people in the Philippines. 110 (4), 991-996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.03.015.

- Antimicrobial activity of stigmasterol from the stem bark of Neocarya macrophylla. J. Med. Plants Econ. Dev.. 2018;2(1):1-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]