Translate this page into:

Chemical composition of pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima) seeds and its supplemental effect on Indian women with metabolic syndrome

⁎Corresponding authors. sarahjane.monica@gmail.com (Sarah Jane Monica), armankhan0301@gmail.com (Ameer Khusro), mariopharma92@gmail.com (Márió Gajdács)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the effect of pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima) seed supplementation on the anthropometric measurements, biochemical parameters, and blood pressure (BP) of Indian women with metabolic syndrome (MetS). Initially, in vitro antioxidant activities of pumpkin seeds extract were assessed using standard methods. In vitro alpha-amylase, alpha-glucosidase, and dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibition effects, along with glucose uptake assay using 3T3-L1 cell lines were performed to determine the antidiabetic effects of the seeds extract. Fatty acids and phytoconstituents were identified using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Indian women aged 30–50 years, having MetS were assigned either to intervention (n = 21) or control (n = 21) group on a random basis. Participants in the intervention group received 5 g of pumpkin seeds for 60 days. Participants in both intervention and control were advised to follow certain dietary guidelines throughout the study. Pumpkin seeds extract exhibited not only strong reducing power but also scavenged DPPH and ABTS●+ free radicals with low IC50 values. Pumpkin seeds inhibited alpha-amylase, alpha-glucosidase, and DPP-IV enzymes at varying concentrations with IC50 values of 138, 22, and 246 µg/mL, respectively. Furthermore, glucose uptake was enhanced by 213% at 300 ng/mL on the 3T3-L1 cell line. GC–MS analysis showed the presence of propyl piperidine, flavone, oleic acid, and methyl esters of fatty acids in the seed extract. On comparing the changes in mean reduction/ increment in the anthropometric measurements as well as biochemical parameters and BP between the groups, significant difference (P = 0.012) was observed only for fasting plasma glucose. Findings of the present study highlight the role of pumpkin seeds as a cost-effective adjunct in treating MetS.

Keywords

Antioxidant

Antidiabetic

Indian women

Metabolic syndrome

Pumpkin seeds

1 Introduction

Edible seeds represent a quick, easy, and readily available source of micronutrients and functional compounds that provide numerous health benefits (Chandrasekar and Sivagami, 2021). Cucurbits are one of the major and diverse groups of plant families that are cultivated, as the seeds of these plants exhibit a wide array of therapeutic properties. Pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima), a fleshy fibrous crop which belongs to Cucurbitaceace family is widely cultivated in both tropical and sub tropical countries (Dotto and Chacha, 2020). Important species of pumpkin include Cucurbita pepo, C. maxima, C. moschata, C. ficifolia, and C. stilbo. An important part of pumpkin is its low fat, protein rich seeds, packed with different classes of phytochemicals (Lestari and Meiyanto, 2018). The Chinese and the Ayurvedic medicinal system have utilized pumpkin seeds for treating kidney disorders, prostate diseases, and erysipelas skin infections (Dhiman et al., 2012). Results of animal and in vitro experimental studies have demonstrated the antimicrobial, antidiabetic, antihyperlipidemic, anti-carcinogenic, antihypertensive, anti-inflammatory, anti-depressant, antioxidant, and anthelmintic effects of pumpkin seeds (Roy and Datta, 2015; Syed et al., 2019). Results of randomized control trials signify the role of pumpkin seeds in the treatment of benign prostate hyperplasia (Patel, 2013).

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) characterized by the presence of hypertension, abdominal obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and low levels of HDL cholesterol elevates the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) (Chait and Den Hartigh, 2020). Herbal medicines and dietary supplements have been widely used as alternative strategy to prevent the onset and progression of MetS. Different non-nutritive components such as dietary fibre, secondary plant metabolites, lipophilic compounds, detoxifying components, and immunity-potentiating agents present in edible seeds exert a positive effect against MetS (Silva et al., 2018).

Pumpkin seeds are rich in phytochemicals, unsaturated fatty acids, essential amino acids, vitamins, and minerals (Mondaca et al., 2019; Dowidar et al., 2020; Musaidah et al., 2021; Hagos et al., 2022). Cucurbitacin E contributes to anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities. Cucurbitin, extracted from pumpkin seeds acts as a vasodilator (Chelliah et al., 2018). Tocopherols reduce oxidative damage and render genoprotective effects to the seeds (Yasir et al., 2016). Trigonelline and D-chiro-inositol maintain glycemic control by acting as insulin sensitizers (Adam et al., 2014). Phenols, flavonoid, saponins, and essential fatty acids exhibit antihyperlipidemic activity. Rats fed with pumpkin seed extract showed an increase in HDL-C along with decrease in LDL-C and total cholesterol (Sharma et al., 2013).

Evidence from human studies is still lacking to substantiate the role of pumpkin seeds in treating metabolic disorders. Previous human studies provided data on the combined beneficial effect of pumpkin, flax, sesame, and black cumin seeds on CVD risk factors (Ristic-Medic et al., 2014; Amin et al., 2015). The nutrient-enriched edible pumpkin seeds which often get discarded habitually may be considered as a functional food. To date, limited attempts have been made to study the effect of pumpkin seeds in treating MetS. Taking these research gaps into consideration, this is the first study to examine the efficacy of pumpkin seeds on the anthropometric measurements, biochemical parameters, and blood pressure on Indian women with MetS.

2 Methodology

2.1 Reagents, media, cell line, and instrument used

Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, gallic acid, quercetin, 2, 2 diphenyl −1- picryl hydrazyl (DPPH), 2, 2′-azino-bis, 3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid (ABTS), ascorbic acid, p-Nitro phenyl-α-D glucopyranoside (p-NPG), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM), and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (India). All other reagents and chemicals used in this study were of analytical grade. 3T3-L1 cells (mouse embryonic fibroblast) were procured from National Centre for Cell science, Pune, India. Spectrophotometric measurements (absorbance value) of in vitro assays were performed using a UV–vis spectrophotometer (Model No: UV-1800PC).

2.2 Collection of plant materials

Seven kilograms of pumpkin seeds were procured from “Nuts ‘N’ Spices” shop in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. The seeds were authenticated by Dr. P. Jayaraman, Anatomist, Plant Anatomy Research Centre, Institute of Herbal Science, Chennai, Tamil Nadu (Voucher No: PARC/2018/3790).

2.3 Preparation of extract

Pumpkin seeds were coarsely crushed using a pestle and mortar. The extract was prepared by adding 50 g of crushed pumpkin seeds to 500 mL of ethanol. After 72 h of maceration under constant magnetic stirring, the extract was filtered using Buchner funnel and Whatmann filter paper no.1. The solvent was evaporated completely by rotary evaporator at 40 °C. The resulting extract was stored at 4 °C for further analysis.

2.4 Screening of phytochemicals

Pumpkin seeds extract was screened for the presence of different classes of phytochemicals viz. alkaloids, diterpenes, triterpenes, flavonoids, glycosides, phenols, saponins, steroids, tannins, terpenoids, and quinones using standard procedures (Tiwari et al., 2011).

2.4.1 Total phenolic content (TPC)

TPC of pumpkin seeds extract was estimated using the Folin-Ciocalteu method, as described by Ainsworth and Gillespie (2007) with minor changes. Initially, 100 µL of the extract was mixed with 1 mL of ethanol and 1 mL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (1:10 dilution using distilled water). This solution was shaken vigorously, followed by the addition of 1 mL of Na2CO3. After incubating the solution for 30 min, the absorbance or optical density (OD) was read at 760 nm. Gallic acid was used as standard for plotting the calibration curve. TPC was expressed as µg GAE/g.

2.4.2 Total flavonoid content (TFC)

TFC of the extract was estimated using aluminium chloride (AlCl3) method as described by Chang et al. (2002) with minor modifications. In brief, 500 µL of the extract was mixed with 0.5 mL of 5% Na2NO3 and the volume was made up to 1 mL using methanol. Later, 0.3 mL of 10% AlCl3 was added and incubated for 5 min. In the end, the reaction mixture was mixed with 1 mL of 1 M NaOH and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The absorbance was read at 510 nm. Quercetin was used as standard for plotting the calibration curve and TFC was expressed as µg QE/g.

2.5 In vitro antioxidant activity

2.5.1 DPPH radical scavenging assay

DPPH radical scavenging activity of the extract was carried out using the method as reported by Prasathkumar et al. (2021) with minor modifications. Different concentrations of the extract (200–1000 µg/mL) were mixed with 0.5 mL of 0.2 mM freshly prepared DPPH solution in methanol. The entire set up was incubated in dark for 30 min at room temperature. The absorbance was read at 517 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as standard. Results were expressed as % inhibition of DPPH radical.

2.5.2 ABTS●+ radical scavenging assay

ABTS●+ radical scavenging activity of the extract was performed using the method described by Arnao et al. (2001) with minor modifications. ABTS●+ a cationic radical was obtained by mixing 7 mM ABTS and 2.45 mM K2S2O8. This solution was incubated for 16 h in dark at room temperature. The resulting ABTS solution was further diluted with 5 mM phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) until an absorbance of 0.70 was obtained at 734 nm. Test tubes containing various concentrations of the extract (2–10 µg/mL) were mixed with 1 mL of diluted ABTS●+ solution and incubated for 10–12 min. The absorbance was read at 734 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as standard. Results were expressed as % inhibition of ABTS●+ radical.

2.5.3 FRAP assay

Fe3+ reducing potential of the extract was evaluated using the method described by Oyaizu (1986) with minor modifications. Different concentrations of the extract (20–100 µg/mL) were mixed with 1000 µL of 0.2 M phosphate buffer solution (pH 6.6) and 1000 µL of 1 % K3[Fe(CN)6]. The reaction mixture was incubated at 50 °C for 25 min. Later, 1 mL of 10% TCA and 0.5 mL of 0.1% freshly prepared FeCl3 was added. The absorbance was read at 700 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as standard. Results of reducing potential were expressed as absorbance value measured at 700 nm.

2.5.4 Phosphomolybdenum reduction assay

The total antioxidant activity of the extract was evaluated using the methodology of Prieto et al. (1999) with minor modifications. Test tubes containing different concentrations of the extract (20–100 µg/mL) were mixed with 1 mL of freshly prepared reagent solution [0.6 M H2SO4, 28 mM Na3PO4, and 4 mM (NH4)2MoO4]. The test tubes were incubated for 90 min at 95 °C and cooled before reading the absorbance at 695 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as standard. Results were expressed as absorbance value read at 695 nm.

2.6 In vitro enzymatic anti-diabetic activity

2.6.1 Alpha-amylase inhibition assay

Alpha-amylase inhibition assay was performed as per the methodology of Sudha et al. (2011) with minor changes. Different concentrations of the extract (6.2–500 µg/mL) were mixed with 0.5 mL of 0.02 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.9 containing 6 mM NaCl) and 10 µL of alpha-amylase solution. The reaction mixture was incubated for 10 min at room temperature. Soon after incubation, 0.5 mL of 1% starch solution was added and incubated for 50 min. Finally, 0.1 mL of dilute HCL was added to stop the enzymatic reaction, followed by the addition of 0.2 mL of freshly prepared iodine solution. The absorbance was read at 565 nm. Acarbose was used as standard. Results were expressed as % inhibition of alpha-amylase.

2.6.2 Alpha-glucosidase inhibition assay

Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity was carried out as per the methodology of Shai et al. (2011) with minor changes. Different concentrations of the extract (6.2–500 µg/mL) were mixed with 50 μL of 50 mM phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.0) and 10 μL of alpha-glucosidase solution. The reaction mixture was incubated for 20 min. Later, 25 μL of 5 mM p-NPG was added and incubated for 20 min. Finally, the enzymatic reaction was stopped by adding 50 μL of 0.1 M Na2CO3 and the absorbance was read at 405 nm. Acarbose was used as standard. Results were expressed as % inhibition of alpha-glucosidase.

2.6.3 Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibition assay

DPP-IV inhibition activity was carried out as per the procedure of Al-masri et al. (2009) with minor changes. Different concentrations of the extract (6.2–500 µg/mL) were mixed with 15 μL of human recombinant DPP-IV enzyme solution and allowed to stand for 5 min. To start the enzymatic reaction, 50 μL of 20 mM ρNA substrate (Gly-Pro- ρNA) were dissolved in Tris buffer solution and incubated for 30 min. Later, 25 μL of 25% CH3COOH was added to stop the reaction. The absorbance value was measured at 410 nm. Vildagliptin was used as standard. Results are expressed as % inhibition of DPP-IV.

2.7 Cell viability

2.7.1 MTT assay

3T3-L1 cells (mouse embryonic fibroblast) were obtained from the National Centre for Cellular Science (NCCS), Pune, India at Passage number 16. Cells were incubated in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The cells were cultured using DMEM with 10% FBS, supplemented with penicillin (120 International Units/mL), streptomycin (75 µg/mL), gentamycin (160 µg/mL), and amphotericin B (3 µg/mL). The cells were sub-cultured after reaching 80% confluence. Cell viability was evaluated using the MTT assay in 96-well plates, wherein 5000 cells/well were seeded and allowed to reach 80% confluence. Various concentrations of the extract (3, 10, 30, 100, and 300 ng/mL) were added and allowed to incubate at 37 °C for 48 h. Later, 50 µL of MTT solution was added and further incubated for 2 h. Finally, 50 µL of DMSO was added to each well, followed by measuring the absorbance at 490 nm. Results are expressed as % inhibition of cell death (Mosmann, 1983).

2.7.2 Adipocytes differentiation

Cells were allowed to grow in 96-well plates for 48 h until post-confluence. Later, the cells were differentiated in a differentiation medium which contained 0.25 µM/L of DEX, 0.5 mM/L of IBMX, and 1 mg/L of insulin in DMEM medium with 10% FBS. After 72 h, the differentiation medium was then replaced with another medium having 1 mg/mL of insulin only. After 48 h, the degree of differentiation was calculated by monitoring the formation of multi nucleation in cells. Later on, the cells were maintained in DMEM medium with 10% FBS (Susantia et al., 2013).

2.7.3 Deoxy-[3H]-D-glucose uptake by 3T3-L1 cells

In brief, the differentiated cells were serum starved for 5 h and incubated with 50 µM of metformin and different concentrations of the extract (3, 10, 30, 100, and 300 ng/mL) for 24 h. The cells were then stimulated with 10 nM of insulin for 20 min. Post incubation, the cells were immediately rinsed using HEPES buffered with Krebs Ringer phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), followed by incubation in HEPES buffered solution with 0.5 µCi/mL of 2-deoxy-D-[1-3H] glucose for 15 min. After incubation, the cells were washed three times using ice cold HEPES buffer. At last, the cells were lysed using 0.1% sodium dodecylsulphate. Radioactivity of cell lysate was determined using a liquid scintillation counter (Susantia et al., 2013).

2.8 GC-MS analysis

Fatty acids and phytoconstituents present in the extract were identified using gas chromatography interfaced to a mass spectrometer (GC–MS). The extract was injected into a HP-column (30 mm × 0.25 mm id with 0.25 μm film thickness) (Agilent technologies 6890 N JEOL GC Mate II GC–MS model). For detection purpose, an electron ionization system operated with an ionization voltage of 70 eV was used. Pure helium gas (99.999%) was used as a carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1 mL/min. The injector temperature was maintained at 250 °C, while the ion-source temperature was programmed at 200 °C. Initially, the oven temperature was maintained at 110 °C with an increase of 10 °C/min to 200 °C. The name, molecular weight, and structure of fatty acids and phytoconstituents were ascertained using the NIST database (Dandekar et al., 2015).

2.9 Intervention study

A randomised control trial was used to study the efficacy of pumpkin seed supplementation on Indian women with MetS. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Independent Institutional Ethics Committee (No.WCC/HSC/IIEC-2016:55).

Two hundred and fifty six women residing in Chennai were contacted and discussed about the study by the researcher. Women were screened for the presence of MetS using the diagnostic criteria given by Alberti et al. (2009). As per this definition, presence of any three out of five below mentioned abnormalities indicated the presence of metabolic syndrome:

-

Waist circumference: ≥ 80 cm

-

Triglyceride: ≥ 150 mg/dL

-

HDL cholesterol: < 50 mg/dL

-

Systolic blood pressure: ≥ 130 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure: ≥ 85 mm Hg)

-

Fasting plasma glucose: ≥ 100 mg/dL

Participants having MetS and who were willing to take part in the study were assigned either to test (n = 21) or control group (n = 21) randomly. Forty-two (n = 42) adult women were selected based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria: Pre-menopausal women aged 30–50 years, having three or more than three components of MetS, and not under any kind of drug therapy.

Exclusion criteria: Women allergic to pumpkin seeds and those having cholesterol > 240 mg/dL, triglycerides > 250 mg/dL, and LDL cholesterol > 190 mg/dL. A written consent was obtained from the study participants before commencing the study.

Intervention group participants received 5 g of pumpkin seeds for 60 days. The dosage was fixed based on FSSAI guidelines (FSSAI, 2015). Pumpkin seeds were measured, packed in zip lock covers, and given to the participants thrice a week. They were asked to consume it during evening snack time. The control group did not receive pumpkin seeds. A counselling session was conducted for the study participants where concepts of MetS, its relation in the development of diabetes and CVD, and the role of non-pharmacological approaches in reducing the risk of developing MetS were well explained to them. Participants were also counselled on how to reduce calorie intake, reduce the serving size of each meal, increase the intake of fruits and vegetables, and avoid heavy meal late at night. Participants belonging to both the groups were asked to follow the above mentioned guidelines throughout the study. Anthropometry, biochemical, and clinical parameters were measured at baseline and at the end of the study using standard methods.

2.9.1 Anthropometric measurements

Height in centimetres was measured using a roll ruler wall mounted stature meter (Gadget hero stature meter: 200 cm). Body weight in kilograms was measured using a weighing machine (Omron, HBF-375). Waist circumference in centimetres was measured using a non-stretchable measuring tape. Body Mass Index (BMI) was calculated as body weight in kilograms divided by height in meter square (kg/m2).

2.9.2 Biochemical parameters

Biochemical tests such as fasting plasma glucose and serum lipid profile were assessed. Five millilitres of venous blood were drawn from the mid-cubital vein using a sterile disposable syringe under aseptic condition after 8 h of overnight fasting. For estimating plasma glucose, blood was collected in a vacutainer tube containing EDTA and estimated using glucose oxidase peroxidase method (Burrin and Price, 1985). For lipid profile assessments, the serum was obtained by centrifuging the blood at 3500 rpm for 5 min. The samples were analyzed using an automated clinical auto analyzer (Cobas 6000; Roche). Enzymatic kit method developed by Allain et al. (1974) and Fossatia and Prencipe (1982) was used to estimate total cholesterol and triglyceride. HDL cholesterol was estimated using the enzymatic kit method developed by Burstein et al. (1970). LDL cholesterol was calculated using the equation of Friedewald et al. (1972). All biochemical tests were carried out in a standard laboratory (Lister Metropolis Laboratory Numgambakkam, Chennai) certified with NABL accreditation.

2.9.3 Blood pressure (BP)

Blood pressure was measured using the electronic BP device (Omron 7120) after the participants had rested for 5 min in a sitting position comfortably. Blood pressure was measured twice and the average was taken as the final reading.

2.10 Statistical analyses

Data analysis was carried out using SPPS software (version 15.0; IBM Corp., Endicott, NY, USA). To get concordant values for all in vitro assays, the experiments were done in triplicates and represented as mean ± SD of triplicates. Independent t-test was applied to check if any difference existed between the intervention and control group. Paired t-test was performed to check if any difference existed among the study participants within the intervention and control group. One way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test were carried out for in vitro assays. For all statistical tests, significance level was set as P < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Phytochemical screening, TPC, and TFC

Preliminary screening of phytochemicals showed the presence of alkaloids, phenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, diterpenes, triterpenes, steroids, tannins, and quinones in the pumpkin seeds extract. TPC and TFC were estimated as 313.19 ± 1.93 µg/g GAE and 212 ± 2.83 µg/g QE, respectively (data not shown).

3.2 Free radical scavenging activity of seeds extract

Table 1 provides data on free radical scavenging activities of the extract. Results showed that pumpkin seeds extract scavenged DPPH and ABTS●+ free radicals in a concentration dependent manner (P < 0.05). The IC50 value of DPPH and ABTS●+ radical scavenging assay was estimated to be 784 and 8 µg/mL, respectively. On comparing the IC50 value, it is evident that pumpkin seed extract had greater potential to scavenge ABTS●+ free radicals (58.36% at 12 µg/mL) than DPPH free radicals (56.6% at 1000 µg/mL). Values are the mean of triplicates. One way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test was performed. a,b,c,d,eDifferent superscripts in a column are significantly different (P < 0.05).

% inhibition of DPPH free radical

% inhibition of ABTS●+ free radical

Concentration (µg/mL)

C. maxima seeds extract

Ascorbic acid

Concentration (µg/mL)

C. maxima seeds extract

Ascorbic acid

200

24.35 ± 8.29a

38.40 ± 1.01a

2

35.63 ± 0.50a

30.96 ± 1.30a

400

36.68 ± 2.24b

48.41 ± 0.18b

4

43.27 ± 0.75b

45.27 ± 0.92b

600

43.79 ± 3.29bc

63.78 ± 2.85c

6

47.82 ± 0.66c

53.88 ± 0.98c

800

52 ± 2.15d

71.53 ± 2.44d

8

52.37 ± 0.78d

67.86 ± 0.59d

1000

56.6 ± 1.98 cd

80.63 ± 1.33e

10

55.90 ± 0.85e

74.28 ± 1.30e

3.3 Reducing power activity of seeds extract

Results of reducing power assays are presented in Table 2. Higher the absorbance, greater is the reducing power. As presented in Table 2, the ability of pumpkin seeds extract to reduce Fe3+ ferric cyanide complex to Fe2+ ferrous cyanide form and phosphomolybdenum (VI) to phosphomolybdate (V) increased with increase in concentration (P < 0.05). Maximum absorbance for FRAP and phosphomolybdenum assay was 0.56 and 0.89, respectively at 120 µg/mL. Values are the mean of triplicates. One way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test was performed. a,b,c,d,eDifferent superscripts in a column are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Concentration (µg/mL)

FRAP assay

Phosphomolybdenum assay

C. maxima seeds extract

Ascorbic acid

C. maxima seeds extract

Ascorbic acid

20

0.14 ± 0.05a

0.20 ± 0.10a

0.52 ± 0.07a

0.75 ± 0.05a

40

0.25 ± 0.06ab

0.34 ± 0.11ab

0.70 ± 0.04b

0.77 ± 0.05ab

60

0.35 ± 0.06bc

0.40 ± 0.12ab

0.81 ± 0.05b

0.85 ± 0.09abc

80

0.41 ± 0.02 cd

0.47 ± 0.09bc

0.85 ± 0.06c

0.87 ± 0.03bc

100

0.49 ± 0.01de

0.52 ± 0.07c

0.87 ± 0.06c

0.89 ± 0.03bc

3.4 Enzymatic antidiabetic activity of seeds extract

Table 3 shows that the seed extract inhibited the action of alpha-amylase, alpha-glucosidase, and DPP-IV enzymes at varying concentrations (6.2–500 µg/mL) (P < 0.05). At 500 µg/mL, pumpkin seeds effectively inhibited 85% of alpha-amylase action, 91.16 % of alpha-glucosidase action, and 81.20% of DPP-IV action. IC50 values for alpha-amylase, alpha-glucosidase, and DPP-IV inhibition assay were estimated as 138, 22, and 246 µg/mL, respectively. By comparing the IC50 values, it may be concluded that pumpkin seeds were found to be a better inhibitor of alpha-glucosidase followed by inhibition of alpha-amylase and DPP-IV activities. Values are the mean of triplicates. One way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test was performed. a,b,c,d,e,f,gDifferent superscripts in a column are significantly different (P < 0.05).

Concentration (µg/mL)

% inhibition of alpha-amylase

% inhibition of alpha-glucosidase

% inhibition of DPP-IV

C. maxima seeds extract

Acarbose

C. maxima seeds extract

Acarbose

C. maxima seeds extract

Vildagliptin

6.2

19.87 ± 1.38a

49.68 ± 0.79a

42.67 ± 5.36a

45.41 ± 6.99a

2.91 ± 0.70a

13.24 ± 0.56a

15.6

23.66 ± 3.87ab

51.72 ± 1.07ab

45.9 ± 2.89ab

67.24 ± 0.54b

5.01 ± 0.37a

25.39 ± 0.32b

31.25

32.79 ± 3.61bc

52.36 ± 0.40bc

52.62 ± 2.96b

87.62 ± 0.59c

24.72 ± 0.54b

36.69 ± 1.25c

62.5

35.09 ± 5.82 cd

54.23 ± 0.53 cd

61.17 ± 1.72c

90.49 ± 0.31 cd

32.00 ± 1.39c

49.51 ± 0.76d

125

45.18 ± 4.28d

55.78 ± 0.41d

70.27 ± 2.27d

92.02 ± 0.06 cd

41.25 ± 0.68d

65.76 ± 1.01e

250

83.55 ± 3.35e

85.98 ± 5.08e

79.20 ± 3.08e

93.43 ± 0.31 cd

52.66 ± 1.77e

72.65 ± 0.74f

500

85.12 ± 1.96e

88.51 ± 2.06e

85.54 ± 1.22e

95.16 ± 0.18d

82.88 ± 2.96f

81.20 ± 0.92 g

3.5 Cytotoxic effect of seeds extract

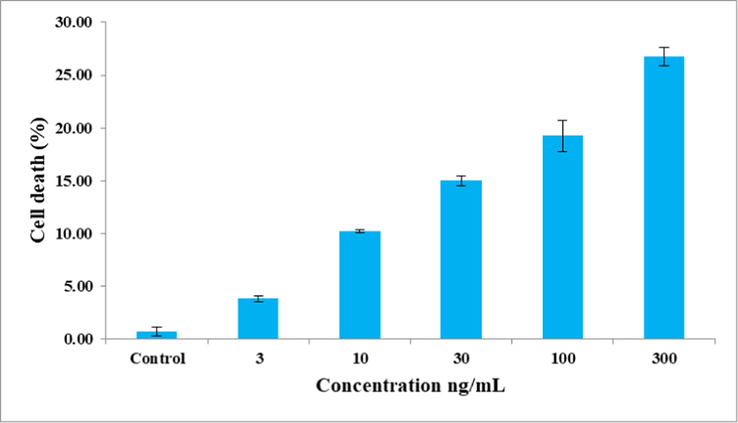

Fig. 1 illustrates that the extract exhibited low level of toxicity to 3T3-L1 cells (26.76% at 300 ng/mL).

Cytotoxic effect of C. maxima seeds extract against 3T3-L1 cells. Values are the mean of triplicates.

3.6 Effect of extract on glucose utilization in 3T3-L1 cell lines

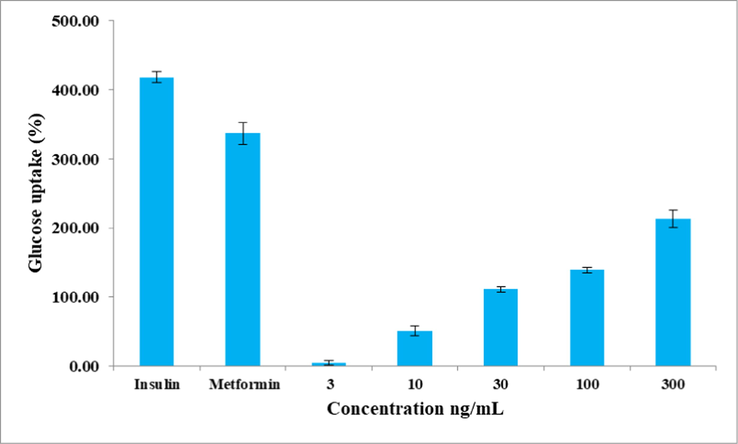

The extract enhanced the glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 cells that increased with increase in concentration (Fig. 2). At 300 ng/mL concentration, glucose uptake was enhanced by 213%. Insulin and metformin enhanced glucose uptake by 419 and 337 %, respectively.

Effect of C. maxima seeds extract on glucose utilization in 3T3-L1 cell lines. Values are the mean of triplicates.

3.7 GC–MS analysis of extract

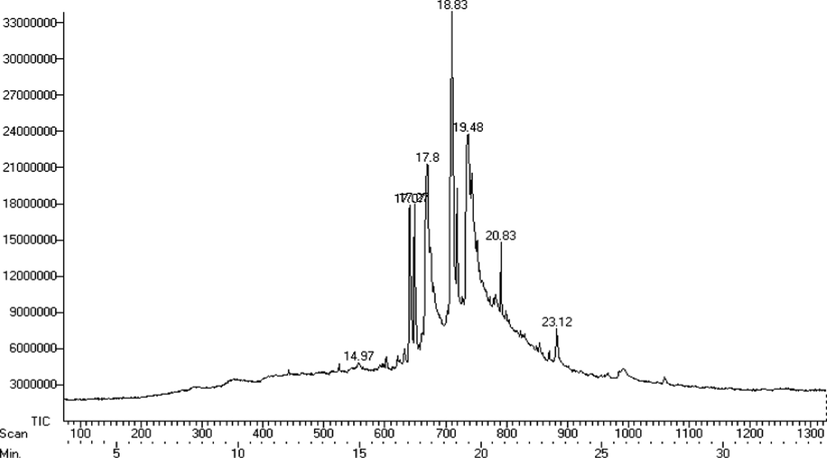

GC–MS analysis of C. maxima seeds extract showed the presence of eight peaks (Fig. 3). Interpretation was done using the NIST database. The eluted compounds were identified to be alkaloid (propyl piperidine), flavone, unsaturated fatty acid (oleic acid), and methyl esters of fatty acids (Table 4).

GC–MS chromatogram of C. maxima seeds extract.

Retention time

Compound name

Structure

Molecular formula

Molecular weight

14.97

1-propylpiperidine

C8H17N

127.23

17.07

Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester

C17H34O2

270.45

17.27

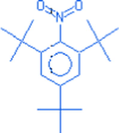

2,4,6 tri-tert-butylnitrobenzene

C18H29NO2

291.43

17.80

n-hexadecanoic acid

C16H32O2

256.42

18.83

10, octadecenoic acid, methyl ester

C19H36O2

296.48

19.48

Oleic acid

C18H34O2

282.46

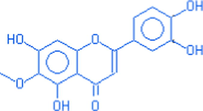

20.83

4H-1-benzo-pyran-4-one 2-(3,4 dihydroxyphenyl) – 5,7 dihydroxy −6- methoxy

C6H12O7

316.00

23.12

Octodecanoic acid 2-oxo-methyl ester

C19H36O3

312.48

3.8 Effect of pumpkin seeds on anthropometry, biochemical parameters, and BP level

Majority of the participants who participated in this study were in the age group of 40–50 years. Regarding marital status, 9.52% of participants in the intervention group were unmarried, while all the participants in the control group were married. According to the annual income classification given by National Council of Applied Economics and Research (Shukla, 2010), 71.43% of participants in the intervention group and 80.95% of participants in the control group were categorized under the middle income group, as per their annual family income. All the study participants were graduates as school teachers were selected and most of them led a sedentary lifestyle (Table 5). Values in parentheses indicate percentage.

Particulars

Intervention group (n = 21)

Control group (n = 21)

Age

30–40 years

7(33.33)

4(19.05)

40–50 years

14(66.67)

17(80.95)

Marital Status

Unmarried

2(9.52)

–

Married

19(90.48)

21(1 0 0)

Family type

Nuclear

15(71.43)

18(85.71)

Joint

6(28.57)

3(14.29)

Annual income

Middle Class

15(71.43)

17(80.95)

Rich

6(28.57)

4(19.05)

Educational qualification

Undergraduates

8(38.10)

4(19.05)

Post graduates

13(61.90)

17(80.95)

Occupation

School teachers

21(1 0 0)

21(1 0 0)

Physical activity

Yes

2(9.52)

5(23.81)

No

19(90.48)

16(76.19)

Type of diet

Vegetarian

1(4.76)

–

Non– vegetarian

20(95.23)

21(1 0 0)

From Table 6, it is evident that over the period of supplementation, reduction in anthropometric measurements, biochemical parameters, and BP were observed for participants in the intervention group when compared to the baseline. Nevertheless, changes that occurred in body weight, waist circumference, lipid ratios, HDL, LDL and non-HDL cholesterol, and BP alone were significant (P < 0.05). Table 7 indicates that the changes that occurred in anthropometric measurements, biochemical parameters, and BP in the control group were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). From Table 8, it may be concluded that on comparing the changes in mean reduction/increment in the anthropometric measurements, biochemical parameters, and BP between the groups, significant difference was observed solely for fasting plasma glucose (P < 0.05). Table 9 revealed that participants in the intervention group who received pumpkin seeds for 60 days showed moderate improvement in their cardio-metabolic profiles, when compared to the control group. **Significant at P < 0.01, *Significant at P < 0.05, NS: Not significant. NS: Not significant. *Significant at P < 0.05, NS: Not significant. Values in parentheses indicate percentage.

Parameters

Baseline

60 days

t-value

P value

Anthropometric measurements

Body weight (kg)

73.12 ± 10.53

72.20 ± 10.32

3.174

0.005**

Waist circumference (cm)

91.32 ± 7.09

90.62 ± 6.70

3.158

0.005**

BMI (kg/m2)

29.43 ± 4.12

28.66 ± 3.71

1.626

0.120NS

Biochemical parameters

Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL)

94.71 ± 12.17

89.86 ± 11.92

2.056

0.053NS

Total cholesterol (mg/dL)

188.57 ± 26.76

184.29 ± 27.28

0.870

0.394NS

Triglyceride (mg/dL)

114.48 ± 31.82

109.10 ± 31.86

0.972

0.343NS

HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

37.81 ± 6.75

42.24 ± 8.88

2.627

0.016*

Non– HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

150.76 ± 27.22

142.05 ± 28.20

2.230

0.037*

LDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

127.87 ± 23.95

120.22 ± 5.06

2.122

0.046*

VLDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

22.30 ± 6.23

21.82 ± 6.37

0.972

0.343NS

LDL cholesterol: HDL cholesterol ratio

3.52 ± 1.04

3.00 ± 0.98

3.785

0.001**

Total cholesterol: HDL cholesterol ratio

5.14 ± 1.20

4.55 ± 1.16

3.577

0.002**

BP levels

Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)

132.52 ± 12.98

122 ± 13.70

4.030

0.001**

Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg)

81.90 ± 9.04

75.79 ± 11.53

2.348

0.029*

Parameters

Baseline

60 days

t-value

P value

Anthropometric measurements

Body weight (kg)

71.10 ± 16.22

71.05 ± 12.75

0.256

0.800NS

Waist circumference (cm)

92.33 ± 12.73

92.10 ± 12.75

0.258

0.621NS

BMI (kg/m2)

29.66 ± 5.44

29.63 ± 5.51

0.327

0.538NS

Biochemical parameters

Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL)

100.29 ± 18.57

101.71 ± 18.77

0.796

0.435NS

Total cholesterol (mg/dL)

199.67 ± 30.85

197.95 ± 30.73

0.511

0.615NS

Triglyceride (mg/dL)

124.38 ± 38.69

123.95 ± 32.35

0.059

0.953NS

HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

42 ± 5.53

42.31 ± 7.21

0.275

0.786NS

Non– HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

157.67 ± 30.30

153.88 ± 28.28

1.119

0.276NS

LDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

132.79 ± 27.69

129.25 ± 26.58

1.002

0.328NS

VLDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

24.88 ± 7.74

24.63 ± 6.66

0.171

0.866NS

LDL cholesterol: HDL cholesterol ratio

3.21 ± 0 0.78

2.99 ± 0.84

1.734

0.098NS

Total cholesterol: HDL cholesterol ratio

4.82 ± 0.92

4.75 ± 0.83

0.652

0.522NS

BP levels

Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)

125.71 ± 12.25

125 ± 13.34

0.103

0.919NS

Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg)

80.90 ± 6.51

80.76 ± 7.54

0.796

0.435NS

Parameters

Intervention group

Control group

t-value

P value

Anthropometric measurements

Body weight (kg)

0.92

0.92

0.05

0.050.538

0.593NS

Waist circumference (cm)

0.70

0.70

0.23

0.230.620

0.537NS

BMI (kg/m2)

0.77

0.77

0.33

0.330.583

0.562NS

Biochemical parameters

Fasting plasma glucose (mg/dL)

4.85

4.85

1.42

1.422.556

0.012*

Total cholesterol (mg/dL)

4.28

4.28

1.72

1.721.980

0.051NS

Triglyceride (mg/dL)

5.38

5.38

0.43

0.431.513

0.134NS

HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

4.43

4.43

0.31

0.310.05

0.963NS

Non– HDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

8.71

8.71

3.79

3.791.94

0.592NS

LDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

7.65

7.65

3.54

3.541.243

0.218NS

VLDL cholesterol (mg/dL)

0.48

0.48

0.25

0.251.637

0.105NS

LDL cholesterol: HDL cholesterol ratio

0.52

0.52

0.22

0.220.795

0.429NS

Total cholesterol: HDL cholesterol ratio

0.59

0.59

0.07

0.070.277

0.783NS

BP levels

Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)

10.52

10.52

0.71

0.710.649

0.518NS

Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg)

6.11

6.11

0.14

0.141.010

0.316NS

Parameters

Intervention group

Control group

Baseline

60 days

Baseline

60 days

Waist circumference > 80 cm

21(1 0 0)

21(1 0 0)

21(1 0 0)

21(1 0 0)

BMI > 25 kg/m2

21(1 0 0)

20(95.24)

17(80.95)

17(80.95)

Fasting plasma glucose > 100 mg/dL

7(33.33)

4(19.05)

8(38.10)

10(47.62)

Total cholesterol > 200 mg/dL

9(42.86)

6(23.81)

11(52.38)

10(47.62)

Serum Triglyceride > 150 mg/dL

4(19.05)

–

7(33.33)

6(28.57)

LDL cholesterol > 100 mg/dL

18(85.71)

16(76.19)

19(90.48)

19(90.48)

Non– HDL cholesterol > 130 mg/dL

16(80.95)

12(57.14)

16(76.19)

18(85.71)

HDL cholesterol < 50 mg/dL

20(95.23)

16(76.19)

18(85.71)

18(85.71)

Blood pressure > 130/85 mmHg

17(80.95)

8(38.10)

12(57.14)

11(52.38)

4 Discussion

One of the prime factors for early onset of MetS are changes in dietary habits. Consuming food items rich in fats, sodium, refined sugars, and empty calories increases the risk of MetS (Castro-Barquero et al., 2020). Concurrently, choosing food items low in saturated fats and high in proteins improves diet quality and decreases the risk of MetS (Krauss and Kris-Etherton, 2020). Indians often fail to meet their protein requirements. Daily inclusion of nuts and oil seeds might help the Indian population to meet their daily protein requirements. Pumpkin seeds rich in proteins and low in saturated fats are less commonly consumed when compared to other oil seeds. On an average, 100 g of pumpkin seeds provide 30.23 g of proteins and 29.05 g of fat. Pumpkin seeds contain 19.35% of saturated fats and 80.65% of unsaturated fats (Glew et al., 2006).

Foods rich in antioxidants form an integral part of diet therapy for all metabolic disorders. Free radicals produced in consequence of cellular redox process occupy a decisive role in the pathophysiology of autoimmune disorders, cancer, neurodegenerative, and CVD (Peng et al., 2014). Antioxidants scavenge free radicals either by removing radical intermediates, terminating chain reactions, inhibiting oxidative reactions or by acting as reducing agents (Kabel, 2014). DPPH is a stable nitrogen centered free radical. On accepting a hydrogen molecule from the donor, the colour of DPPH changes from purple to yellow. Greater the decolourization, greater is the antioxidant activity (Kedare and Singh, 2011). ABTS●+ is a green blue cationic radical produced by the reaction between ABTS●+ and potassium persulphate. In the presence of a hydrogen-donating molecule, ABTS●+ radical gets decolourized. Greater the decolourization, greater is the antioxidant activity (Ilyasov et al., 2020). In this study, pumpkin seeds extract scavenged DPPH and ABTS●+ free radicals in a concentration dependent manner. Prasad (2014) evaluated the antioxidative effect of seeds belonging to the Cucurbitaceace family viz. pumpkin, watermelon, muskmelon, and bottle gourd using DPPH assay. Amongst the four seeds analyzed, pumpkin showed the highest antioxidant activity with an IC50 value of 620 µg/mL. Sakka and Karantonis (2015) reported similar results on ABTS●+ scavenging activity of aqueous and chloroform extract of C. moschata seeds and the IC50 value was calculated as 12.77 and 137 mg/mL for aqueous and chloroform extract, respectively.

Reducing capacity serves as an important indicator of potential antioxidant activity. In the present study, the ability of pumpkin seeds extract to reduce Fe3+ ferric cyanide complex to Fe2+ ferrous cyanide form and reduction of phosphomolybdenum (VI) to phosphomolybdate (V) bluish green complex was evaluated using FRAP and phosphomolybdenum assays. Results showed that the reducing power of pumpkin seeds extract increased with increase in concentration. Phenols and flavonoids present in pumpkin seeds might have contributed to the antioxidant activity (Peng et al., 2021).

Alpha-amylase hydrolyzes complex carbohydrates to oligosaccharides and disaccharides; while alpha-glucosidase hydrolyzes disaccharides into monosaccharides. Inhibiting the action of alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase reduce the likelihood of post-prandial hyperglycemia (Poovitha and Parani, 2016). Pumpkin seeds extract showed inhibitory effect on alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase. Insulin and oral antidiabetic drugs are used to treat hyperglycemia. Of late, there is more demand for natural products possessing antidiabetic activity among individuals, since anti-diabetic drugs cause abdominal discomfort, bloating, nausea, and dyspepsia. These adverse effects occur due to imprudent inhibition of alpha-amylase that leads to abnormal bacterial fermentation of undigested carbohydrates (Kumar et al., 2011). To overcome this problem, it is imperative to use natural products having mild effect on alpha-amylase and strong effect on alpha-glucosidase (Pinto et al., 2009). On comparing IC50 values, it is evident that pumpkin seeds extract had moderate inhibition action on alpha-amylase and strong inhibition action on alpha-glucosidase. Findings of the study are in agreement with Pinto et al. (2009). Kushawaha et al. (2016) noticed that the aqueous extract of C. maxima seeds inhibited the action of alpha-amylase and alpha-glucosidase by 46.03 ± 1.37 and 35.11 ± 1.04%. Besides starch blockers, DPP-IV inhibitors have received attention in treating hyperglycemia. Glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP-1) secreted by the intestinal cells maintains blood glucose homeostasis through several mechanisms. The short half-life period of GLP-1 is 1–2 min and gets metabolized quickly by DPP-IV enzyme. Inhibiting the action of DPP-IV enzyme lengthens the half-life period of GLP-1 (Singh, 2014). In this context, pumpkin seeds extract inhibited the action of DPP-IV enzyme.

Pumpkin seeds extract enhanced glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 cells at various tested concentrations. Metformin used by type 2 diabetic individuals promotes glucose uptake by improving insulin sensitivity and suppressing the action of gluconeogenic enzymes (Viollet et al., 2012). Secondary plant metabolites like flavonoids, polyphenols, and terpenoids promote glucose uptake by suppressing gluconeogenesis and increasing insulin sensitivity (Hanhineva et al., 2010). Thus, glucose uptake in 3T3-L1 cells by pumpkin seeds extract may be due to the presence of dietary phenols and flavonoids. This is the first study to document the anti-diabetic effect of pumpkin seeds extract using 3T3-L1 cells. The inhibitory effects of pumpkin seeds extract against alpha-amylase, alpha-glucosidase, and DPP-IV along with enhancing glucose uptake explicate the promising role of pumpkin seeds in preventing post prandial hyperglycemia.

Reducing body weight by 5 to 10% minimizes the risk of cardio metabolic abnormalities (Han and Lean, 2016). Participants who received pumpkin seeds showed a reduction in body weight, waist circumference, and BMI. However, these changes were not significant when compared with their counterparts. After 60 days, the mean fasting plasma glucose levels decreased significantly for participants in the intervention group when compared to the control group. Wide range of plant-derived components such as tocopherols, phenolic compounds, and flavonoids, present in pumpkin seeds contribute to hypoglycaemic activity (Bharti et al., 2013). Makni et al. (2008) documented that flax and pumpkin seeds given to diabetic rats showed hypoglycaemic, hypolipidemic, and nephroprotective effects.

Asian Indians show an eccentric pattern of atherogenic dyslipidemia characterized by hypertriglyceridemia, increased levels of LDL cholesterol, and low levels of HDL cholesterol (Joshi et al., 2014). In the present investigation, pumpkin seeds showed positive effects on all lipid parameters. A significant decrease in LDL and non-HDL cholesterol was also observed. HDL cholesterol is beneficial to human beings because it removes cholesterol from the peripheral tissues and delivers it back to liver (Marques et al., 2018). HDL-C otherwise known as anti-atherogenic “good” cholesterol decreases the risk of CVD (Rajagopal et al., 2012). In this study, supplementing pumpkin seeds to adult women with MetS increased HDL cholesterol by 4.43 mg/dL when compared to baseline. Abuelgassim and Al-Showayman (2012) reported that pumpkin seed significantly increased HDL cholesterol in atherogenic rats. Ristic-Medic et al. (2014) proved that supplementing 30 g of dietary seed mixture of pumpkin/sesame/flax seeds in the ratio of 18:6:6 to patients undergoing haemodialysis for 12 weeks showed significant (P = 0.001) reduction in blood sugar, insulin, inflammatory markers, and triglyceride levels. The levels of linoleic, dihomogamma linoleic acid (DGLA), arachidonic acid, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), eicosa pentanoic acid (EPA), and docosa hexanoic acid (DHA) increased after 12 weeks. Fathima et al. (2014) reported the potential of Nigella sativa seeds to increase HDL cholesterol level in hyperlipidemic patients (P < 0.001). Ibrahim et al. (2014) reported that the powdered Nigella sativa seeds (1 g/day) supplemented to menopausal women for 8 weeks significantly increased HDL cholesterol, and decreased LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglyceride levels.

Unsaturated fatty acids present in plant products inhibit the activity of cholesterol acyl transferase, which is the rate limiting step in cholesterol absorption (Jesch and Carr, 2017). Fatty acids present in pumpkin seeds include palmitic acid, stearic acid, oleic acid, and linoleic acid. On a percentage basis, oleic acid is the main fatty acid (45.4%), followed by linoleic acid (31%), palmitic acid (13%), and stearic acid (7.9%) (Glew et al., 2006). GC–MS analysis of pumpkin seeds extract showed the presence of oleic acid and palmitic acid. Polyunsaturated fatty acids present in nuts and oil seeds prevent fat accumulation in adipose tissues through adaptive thermogenic effect (Fan et al., 2019). Besides fatty acids, other non-nutritive compounds present in pumpkin seeds contribute to antihyperlipidemic properties. Pumpkin seeds provide 265 mg of phytoestrogen/100 g. Secoisolariciresinol, the main phytoestrogen present in pumpkin seeds exhibits hypolipidemic effect by increasing angiogenesis and decreasing apoptosis (Penumathsa et al., 2007).

Reducing systolic blood pressure (SBP) by 10 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) by 5 mm Hg lower the incidence of stroke by 30–40% and acute coronary events by 16% (Perk et al., 2012). In this investigation, participants in the intervention group showed a significant (P = 0.001) reduction in DBP and SBP when compared to baseline. The mean SBP decreased (P = 0.029) from 132.52 ± 12.98 mm Hg to 122 ± 13.70 mm Hg; while the mean DBP decreased from 81.90 ± 9.04 mm Hg to 75.79 ± 11.53 mm Hg. Gossell Williams et al. (2011) concluded that post menopausal women supplemented with 2 g of pumpkin seed oil for 90 days showed significant (P = 0.046) reduction in DBP from 81.10 ± 7.94 mm Hg to 75.6 ± 11.93 mm Hg and significant (P = 0.029) increase in HDL cholesterol from 0.92 ± 0.23 to 1.07 ± 0.27 mmol/L. In a double blinded placebo randomized trial, it was observed that supplementing 30 g of milled flaxseed for 6 months to patients diagnosed with peripheral arterial disease resulted in significant reduction in DBP and SBP (Leyva et al., 2011).

5 Conclusions

Type 2 diabetes mellitus and CVD are preceded by a group of risk factors that are components of MetS. Currently, a wide variety of plant-based products have received attention in treating MetS. This study highlights the antioxidant, anti-diabetic, antihypertensive, and antihyperlipidemic roles of pumpkin seeds. Though the present study reports certain beneficial effects of pumpkin seeds on Indian women with MetS, the study has few limitations such as smaller sample size and shorter duration. Hence, larger size randomized control trials are required to corroborate the medicinal properties of pumpkin seeds. Further studies on analyzing the effect of pumpkin seeds on nutrient biomarkers along with its appetite suppressing action would be helpful for better understanding the different mechanisms by which pumpkin seeds exhibit antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic properties.

Acknowledgement

M.G. was supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship (BO/00144/20/5) of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The research was supported by the ÚNKP-21-5-540-SZTE New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund. The authors like to thank Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia for their support (Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number: TURSP-2020/80).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- The effect of pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) seeds and L-arginine supplementation on serum lipid concentrations in atherogenic rats. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med.. 2012;9:131-137.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The hypoglycemic effect of pumpkin seeds, Trigonelline (TRG), Nicotinic acid (NA), and D-Chiro-inositol (DCI) in controlling glycemic levels in diabetes mellitus. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nut.. 2014;54:1322-1329.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of total phenolic content and other oxidation substrates in plant tissues using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Nat. Protoc.. 2007;2:875-877.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A joint interim statement of the international diabetes federation task force on epidemiology and prevention; national heart, lung, and blood institute; american heart association; world heart federation; international atherosclerosis society; international association for the study of obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640-1645.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin. Chem.. 1974;20:470-475.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP IV) is one of the mechanisms explaining the hypoglycemic effect of berberine. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem.. 2009;24:1061-1066.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical efficacy of the co-administration of Turmeric and Black seeds (Kalongi) in metabolic syndrome. a double blind randomized controlled trial – TAK- MetS trial. Complement. Ther. Med.. 2015;23:165-174.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The hydrophilic and lipophilic contribution to total antioxidant activity. Food Chem.. 2001;73:239-244.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tocopherols from seeds of Cucurbita pepo against diabetes. validation by in vivo experiments supported by computational docking. J. Formos. Med. Assoc.. 2013;112:676-690.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid method for the isolation of lipoproteins from human serum by precipitation with polyanions. J. Lipid Res.. 1970;11(6):583-595.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dietary strategies for metabolic syndrome: a comprehensive review. Nutrients. 2020;2020(12):1-21.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Adipose tissue distribution, inflammation and its metabolic consequences, including diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med.. 2020;2020(7):22.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Edible seeds medicinal value, therapeutic applications and functional properties: a review. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci.. 2021;13:11-18.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colometric methods. J. Food Drug Anal.. 2002;10:178-182.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antihypertensive effect of peptides from sesame, almond, and pumpkin seeds: in silico and in vivo evaluation. J. Agric. Life Environ. Sci.. 2018;30:12-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- GC-MS analysis of phytoconstituents in alcohol extract of Epiphyllum oxypetalum leaves. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem.. 2015;4:149-154.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review on the medicinally important plants of the family cucurbitaceae. Asian J. Clin. Nutr.. 2012;4:16-26.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The potential of pumpkin seeds as a functional food ingredient a review. Sci Afri.. 2020;10:1-14.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The critical nutraceutical role of pumpkin seeds in human and animal health: an updated review. Zagazig. Vet. J.. 2020;48:199-212.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Adaptive thermogenesis by dietary n 3 polyunsaturated fatty acids: emerging evidence and mechanism. Biochim. Biophy. Acta. Mol. Cell. Biol. Lipids. 2019;1864(1):59-70.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Nigella sativa on HDL-C and body weight. Pak. J. Medical Health Sci.. 2014;8:122-124.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serum triglycerides determined colorimetrically with an enzyme that produces hydrogen peroxide. Clin. Chem.. 1982;28:2077-2080.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of the concentration of low density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin. Chem.. 1972;18:499-502.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- FSSAI, Food Safety and Standards Authority of India 2015. F.No 1-4/Nutraceuticals/FSSAI – 2003. A statutory authority under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi

- Glew, R.H., Glew, R.S., Chuang, L.T., Huang, Y.S., Millson, M., Constans, D., Vanderjagt, D. J., 2006. Amino acid, mineral and fatty acid content of pumpkin seeds (Cucurbita spp.) and Cyperus esculentus nuts in the Republic of Niger. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 61, 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11130-006-0010-z.

- Improvement in HDL cholesterol in postmenopausal women supplemented with pumpkin seed oil: pilot study. Climacteric. 2011;14:558-564.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Development of analytical methods for determination of β-carotene in pumpkin (Cucurbita maxima) flesh, peel, and seed powder samples. Int. J. Anal. Chem.. 2022;2022:1-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A clinical perspective of obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. JRSM Cardiovasc. Dis.. 2016;5:1-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of dietary polyphenols on carbohydrate metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2010;11:1365-1402.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective effects of Nigella sativa on metabolic syndrome in menopausal women. Adv. Pharm. Bull.. 2014;4:29-33.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- ABTS/PP decolorization assay of antioxidant capacity reaction pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2020;21:1-27.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Food ingredients that inhibit cholesterol absorption. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci.. 2017;22:67-80.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of dyslipidemia in urban and rural India: the ICMR-INDIAB study. Plos One. 2014;9(5):e96808

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Free radicals and antioxidants: Role of enzymes and nutrition. World J. Nutr. Health. 2014;2:35-38.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genesis and development of DPPH method of antioxidant assay. J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2011;48:412-422.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Public health guidelines should recommend reducing saturated fat consumption as much as possible: debate Consensus. Am. J. Clin. Nutr.. 2020;112:19-24.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- α-glucosidase inhibitors from plants: a natural approach to treat diabetes. Pharmacogn Rev.. 2011;5:19-29.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity assessment of Cucurbita maxima seeds – a LIBS based study. Int. J. Phytomed.. 2016;8:312-318.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, B., Meiyanto, E., 2018. A review. The emerging nutraceutical potential of pumpkin seeds. Indones. J. Cancer Chemoprev. 9, 92-101. https://doi/org/10.14499/indonesianjcanchemoprev9iss2pp92-101.

- The effect of dietary flaxseed on improving symptoms of cardiovascular disease in patients with peripheral arterial disease: the rationale and design of the FlaxPAD randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin. Trials. 2011;32:724-730.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hypolipidemic and hepato protective effects of flax and pumpkin seed mixture rich in ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids in hypercholesterolemic rats. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2008;46:3714-3720.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Reverse cholesterol transport: molecular mechanisms and the non-medical approach to enhance HDL cholesterol. Front. Physiol.. 2018;9:1-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pumpkin seeds (Cucurbita maxima). A review of functional attributes and by-products. Rev. Chil. Nutr.. 2019;46:783-791.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;95:55-63.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of pumpkin seeds biscuits and Moringa extract supplementation on hemoglobin, ferritin, C-reactive protein, and birth outcome for pregnant women: a systematic review. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci.. 2021;9:360-365.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Studies on products of browning reactions: antioxidant activities of products of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. J. Nutr.. 1986;44:307-315.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pumpkin (Cucurbita sp.) seeds as a nutraceuticals. a review on status quo and scopes. Mediterr. J. Nutr. Metab.. 2013;6:183-189.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biology of ageing and role of dietary antioxidants. BioMed Res. Int.. 2014;1–13

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of roasting on the antioxidant activity, phenolic composition and nutritional quality of pumpkin seeds (Cucurbita pepo) Fornt. Nutr.. 2021;8:1-11.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside: relevance to angiogenesis and cardioprotection against ischemic reperfusion injury. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther.. 2007;320:951-959.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (Version 2012): The fifth joint task force of the European society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Atherosclerosis. 2012;223(1):1-68.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of anti-hyperglycemia and anti-hypertension potential of native Peruvian fruits using in vitro models. J. Med. Food. 2009;12:278-291.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro and in vivo α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibiting activities of the protein extracts from two varieties of bitter gourd (Momordica charantia L.) BMC Complement. Altern. Med.. 2016;16:1-15.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro phytochemical analysis and antioxidant activity of seeds belonging to cucurbitaceace family. Indian J. Adv. Plant Res.. 2014;1:13-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical screening and in vitro antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetic, and wound healing attributes of Senna auriculata (L.) Roxb. leaves. Arab. J. Chem.. 2021;14:1-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Anal. Biochem.. 1999;269:337-341.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- High density lipoprotein: How high. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab.. 2012;16:236-238.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ristic-Medic, D., Perunicic-Pekovic, G., Rasic-Milutinovic, Z., Takic, M., Popovic, T., Arsic, A., Glibetic, M., 2014. Effects of dietary milled seed mixture on fatty acid status and inflammatory markers in patients on hemodialysis. Sci. World J. 1-9. https://doi/org/10.1155/2014/563576.

- A comprehensive review on the versatile pumpkin seeds (Cucurbita maxima) as a valuable natural medicine. Int. J. Curr. Res.. 2015;7:19355-19361.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro health beneficial activities of pumpkin seeds from Cucurbita moschata cultivated in Lemnos. Int. J. Food Stud.. 2015;4:221-237.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory effects of five medicinal plants on rat alpha-glucosidase: comparison with their effects on yeast alpha-glucosidase. J. Med. Plant Res.. 2011;5:2863-2867.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic activity of Cucurbita maxima Duchense (pumpkin) seeds on streptozotocin induced diabetic rats. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem.. 2013;1:108-116.

- [Google Scholar]

- Shukla R. 2010. NSHIE 2004-2005. Data National Council of Applied Economic Research. How India spends and saves. Unmasking the real India sage New Delhi.

- An overview of novel dietary supplements and food ingredients in patients with metabolic syndrome and non- alcoholic fatty liver disease. Molecules. 2018;23:877-907.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dipeptidyl peptidase – 4- inhibitors: Novel mechanism of actions. Indian J. Endocrinol Metab.. 2014;18:753-759.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Potent α-amylase inhibitory activity of Indian Ayurvedic medicinal plants. BMC Complement Altern. Med.. 2011;1(11):1-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Friedelin and lanosterol from Garcinia prainiana stimulated glucose uptake and adipocytes differentiation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2013;27:417-424.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional and therapeutic effects of the pumpkin seeds. Biomed. J. Sci. Technol. Res.. 2019;21:15798-15803.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical screening and extraction. a review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2011;1:98-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin. An overview. Clin. Sci.. 2012;122:253-270.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and genoprotective activity of selected cucurbitaceae seed extracts and LC–ESIMS/MS identification of phenolic components. Food Chem.. 2016;199:307-313.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]