Translate this page into:

Citrus hystrix: A review of phytochemistry, pharmacology and industrial applications research progress

⁎Corresponding author. 1511006@sntcm.edu.cn (Haifa Qiao)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Citrus hystrix DC, also known as kaffir lime, is a species of lime native to Southeast Asia and the southern China. So far, 78 components have been characterized from C. hystrix. The main constituents of these compounds include coumarins, flavonoids, phenolic acids and terpenoids. Studies of the pharmacological research of C. hystrix have indicated that this edible medicinal herb shows therapeutic potential including antimicrobial, anti-mosquito, antioxidant, antitumor, anti-inflammatory and neural-protective properties. The purpose of this review is to give a summarization of C. hystrix studies until 2023. It is also the intention of this paper to review advances in the botanical, phytochemical, pharmacological studies and industrial applications of C. hystrix. This will help to provide a useful bibliography for further research of C. hystrix in drugs and foodstuffs.

Keywords

Citrus hystrix

Edible medicinal herb

Phytochemistry

Pharmacology

Review

- AML

-

acute myeloid leukemia

- AChE

-

acetylcholinesterase

- ASA

-

acetyl salicylic acid

- CUPRAC

-

Cupric Reducing Antioxidant Capacity

- DPPH

-

2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl scavenging activity

- DMBA

-

dimethylbenz[a]anthracene

- FRAP

-

ferric reducing/antioxidant potency

- FIR

-

far-infrared radiation

- GC–MS

-

gas chromatography/mass spectrometry

- HA

-

hot-air

- LRH

-

low relative humidity

- MDR

-

multidrug-resistant

- MTT

-

3- (4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- MRSA

-

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- MSSA

-

methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus

- ORAC

-

oxygen radical uptake capacity

- ROS

-

reactive oxygen species

- SK

-

standard streptokinase

- TAC

-

total antioxidant capacities

- TPC

-

total phenolic content

- TFC

-

total flavonoid content

- TPA

-

12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

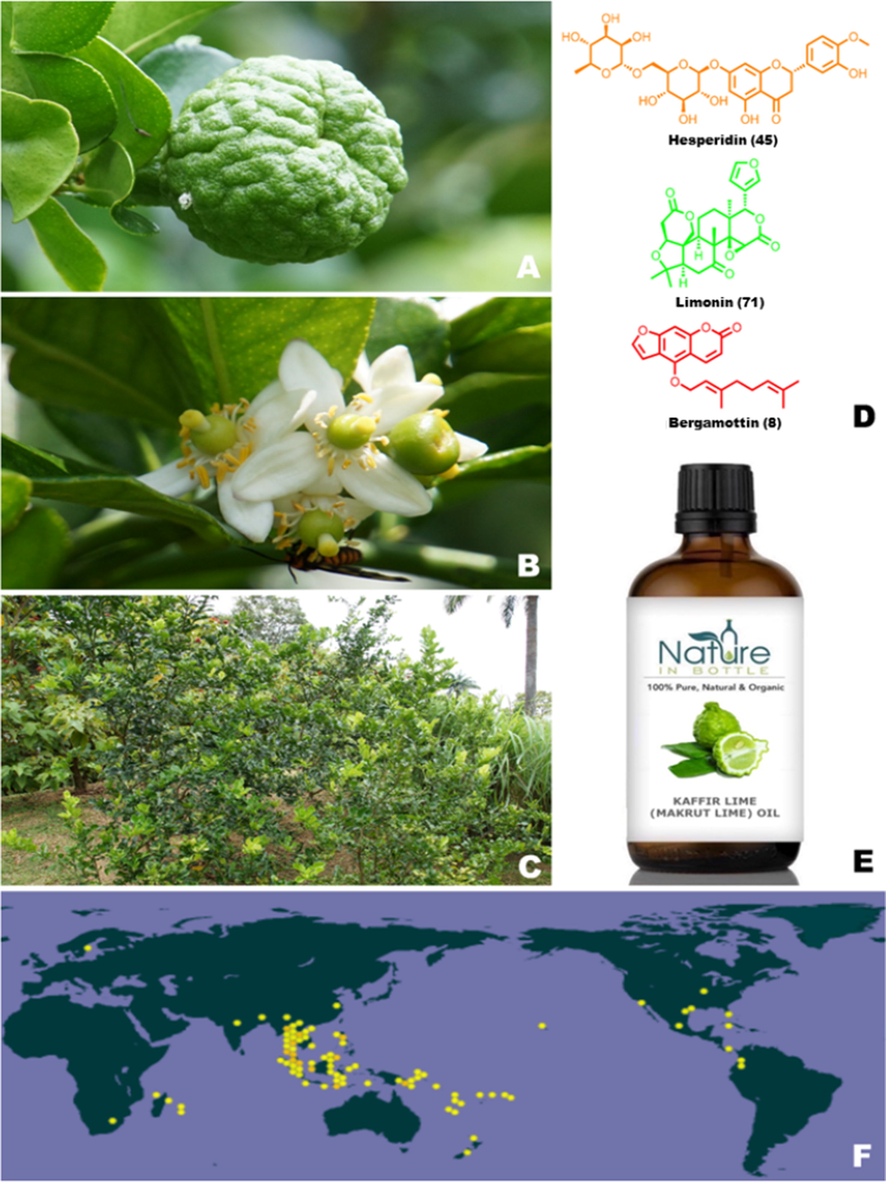

Citrus hystrix DC, also known as kaffir lime, makrut lime, Thai lime or Mauritius papeda, is a species of citrus in the family Rutaceae, native to tropical Southeast Asia and the south of China. It grows all over the world in climates suitable as a garden shrub for home fruit production, it is also well-suited for container gardens and for large garden pots on patios, terraces and in conservatories. In Southeast Asian cuisines including Indonesian, Laotian, Cambodian, and Thai cuisines, C. hystrix leaves are frequently utilized. The leaf, which can be utilized fresh, dried, or frozen, is the plant component that is used the most frequently. The leaves of C. hystrix are used in Vietnamese cookery to enhance the flavor of chicken meals and to lessen the strong odor that results from boiling snails. The leaf is used in Indonesian cooking for dishes like ayam soto and for chicken and fish along with Indonesian laurel leaves (Fig. 1). C. hystrix leaves are also used in Malaysian and Burmese cuisines for tea making and as a flavouring agent. In several Asian nations, C. hystrix juice and peel rinds are used in traditional medicine. The fruit juices are frequently found in shampoo and are said to be effective against head lice. The rough-skinned, bitter-tasting fruits of C. hystrix only yield a tiny amount of juice, which can be mixed with other fruit juices to improve food flavor and is also used in canned products. The pharmaceutical, agronomic, food, sanitary, cosmetic, and fragrance sectors all use C. hystrix oil as a feedstock. In addition, it is frequently utilized in aromatherapy and is a crucial component of many cosmetic and beauty products.

C. hystrix: (A) C. hystrix fruits; (B) flower of C. hystrix; (C) bushes of C. hystrix C. hystrix; (D) chemical structure of typical constituents from C. hystrix; (E) essential oil products containing C. hystrix; (F) distribution of P. chinensis (https://www.gbif.org/).

Contemporary pharmacological research has proven that C. hystrix ingredients show a wide range of pharmacological actions including antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-tumour and anti-inflammatory activities. These activities are largely consistent with those seen for C. hystrix in traditional applications. Historically, the main use of C. hystrix appears to be as an insecticide to wash the head and treat the feet to kill terrestrial leeches. The principal components of C. hystrix include coumarins, flavonoids, phenolic acids and terpenoids. Of these ingredients, bergamottin (8) is the most representative coumarin compound that has been shown to have multiple potential pharmacological activities. There are no authoritative comprehensive reviews of C. hystrix published in print as of yet. With all identified structures presented, the goal of this study is to consolidate the results of phytochemical and pharmacological investigations conducted over the previous few decades. The purpose of this essay is to understand new developments in the chemical constituents, pharmacological advantages and industrial uses of C. hystrix.

2 Botany

C. hystrix is a species in the genus Citrus (family Rutaceae). According to “The Plant List” (https://www.theplantlist.org), C. hystrixis is the only accepted name for the plant with relative to other synonyms including C. aurantium var. saponacea Saff., C. auraria Michel, C. balincolong (Yu.Tanaka) Yu.Tanaka, C. boholensis (Wester) Yu.Tanaka, C. celebica Koord., C. combara Raf., C. hyalopulpa Yu.Tanaka, C. kerrii (Swingle) Yu.Tanaka, C. micrantha Wester and C. papuana F.M.Bailey, etc.

C. hystrix is about 3–6 m high of evergreen tree. Tender blade ovate leaves of C. hystrix are often dark red with petiole winged. Buds globose and white petals, which is pinkish red from outside, can be found in the flowers of C. hystrix. Lemon yellow C. hystrix fruits are often slightly coarse or smooth with numerous and prominent oil dots on the thick pericarp. The shape of fruit is apex rounded and the sarcocarp is usually divided into 11–13 segments. The flowering stage ranges from March to May, and the mature fruit phase is typically from November to December (Flora of China Editorial Committee, 2001).

3 Nutritional and physiochemical composition

3.1 Nutritional composition

The nutrient composition of the C. hystrix fruit contains per 100 g edible portion was reported as: water 88.6 g, protein 0.8 g, fat 0.6 g, carbohydrate 8.5 g, fiber 0.8 g, carotene 16 mg, vitamin A 3 mg, vitamin B1 0.02 mg, vitamin B2 0.07 mg, and vitamin C 37 mg trace elements including Ca 57 mg, P 2 mg, Fe 0.1 mg, K 172 mg (Table 1). Additionally, essential oils were reported to be rich in peel and juice of C. hystrix (Lim and Lim 2012). The main components in the peel oil were reported as follow: β-pinene (22.7%), limonene (17.3%), sabinene (11.9%), citronellal (7.8%), terpinen-4-ol (7.2%), citronellol (3.6%), and linalool (2.6%), while in the juice were β-pinene (35.6%), sabinene (7.0%), limonene (5.9%), terpinen-4-ol (19.7%), γ-terpinene (4.4%), and linalool (2.8%). These results revealed the low-calorie and health-promoting properties of C. hystrix. Nowadays, lipid compositions are getting more and more attentions due to their broad implications for human disease (Al Othman et al., 2023), thus C. hystrix which is rich in lipids will be appreciate with great prospect.

Nutritional composition

Contents

Nutritional composition

Contents

Protein

0.8 g/100 g

Vitamin B2

0.07 mg/100 g

Fat

0.6 g/100 g

Vitamin C

37 mg/100 g

Carbohydrate

8.5 g/100 g

Ca

57 mg/100 g

Fiber

0.8 g/100 g

P

2 mg/100 g

Carotene

16 mg/100 g

Fe

0.1 mg/100 g

Vitamin A

3 mg/100 g

K

172 mg/100 g

Vitamin B1

0.02 mg/100 g

3.2 Physiochemical and structural features

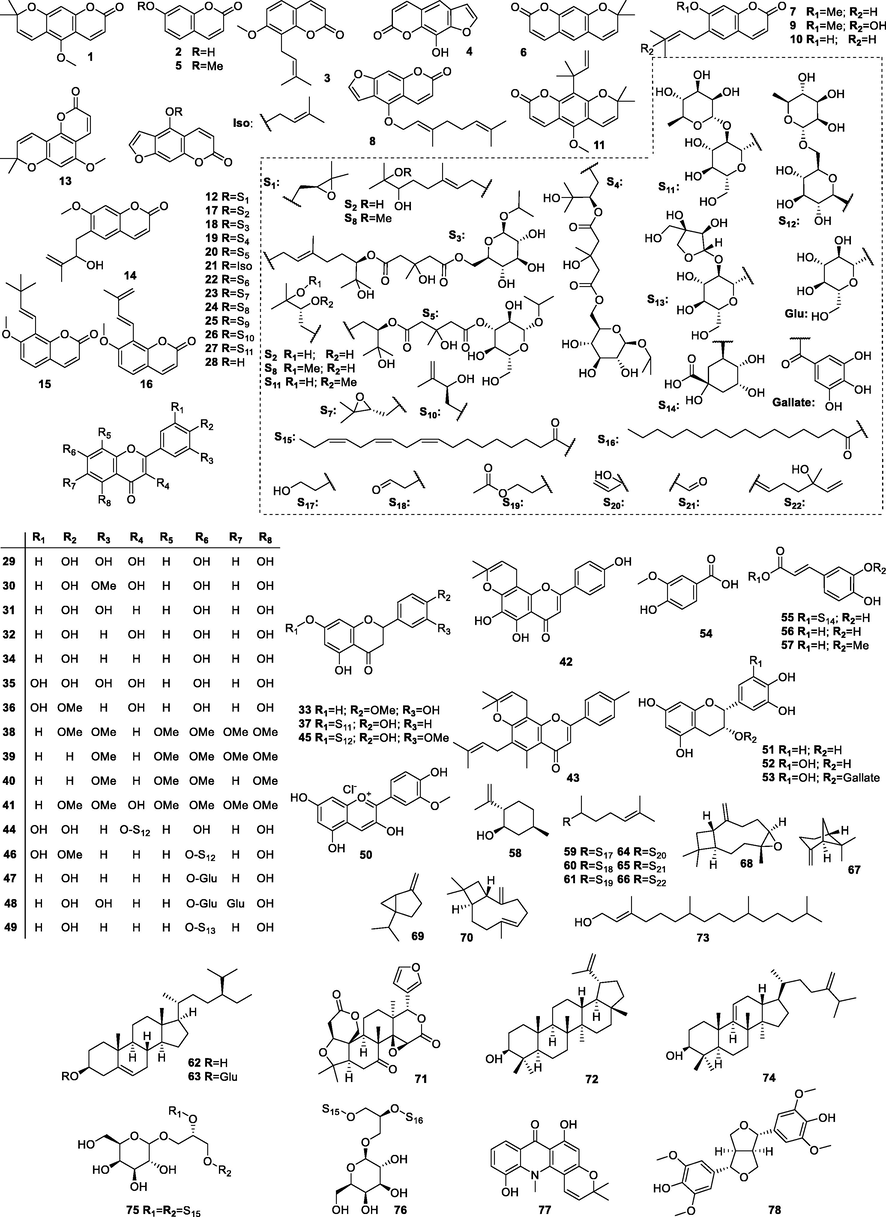

Detailed phytochemical and nutrient analyses of C. hystrix have been performed. The constituents isolated from C. hystrix include coumarins, flavonoids, phenolic acids and terpenoids, among others, which are the primary types. A summary and compilation of all compounds regarding their names, CAS numbers and formulae is given in Table 2, and the structure of these compounds has been detailed in Fig. 2.

NO.

Name

Formula

CAS

Ref.

Coumarins

1

Xanthoxyletin

C15 H14 O4

84-99-1

(Murakami et al., 1999)

2

Umbelliferone

C9 H6 O3

93-35-6

(Murakami et al., 1999)

3

Osthol

C15 H16 O3

484-12-8

(Murakami et al., 1999)

4

Bergaptol

C11 H6 O4

486-60-2

(Murakami et al., 1999)

5

Seselin

C14 H12 O3

523-59-1

(Murakami et al., 1999)

6

Xanthyletin

C14 H12 O3

553-19-5

(Murakami et al., 1999)

7

Suberosin

C15 H16 O3

581-31-7

(Murakami et al., 1999)

8

Bergamottin

C21 H22 O4

7380-40-7

(Murakami et al., 1999)

9

Suberenol

C15 H16 O4

18529-47-0

(Murakami et al., 1999)

10

7-Demethylsuberosin

C14 H14 O3

21422-04-8

(Murakami et al., 1999)

11

Dentatin

C20 H22 O4

22980-57-0

(Murakami et al., 1999)

12

Oxypeucedanin

C16 H14 O5

26091-73-6

(Murakami et al., 1999)

13

5-Methoxyseselin

C15 H14 O4

31525-76-5

(Murakami et al., 1999)

14

Tamarin

C15 H16 O4

65451-76-5

(Murakami et al., 1999)

15

Murraol

C15 H16 O4

109741-38-0

(Murakami et al., 1999)

16

trans-Dehydroosthol

C15 H14 O3

112667-50-2

(Murakami et al., 1999)

17

4- [(6, 7-Dihydroxy-3, 7-dimethyl-2-octen-1-yl) oxy] −7H-furo[3, 2-g] [1] benzopyran-7-one; 5- [(6′, 7′-Dihydroxy-3′, 7′-dimethyl-2-octenyl) oxy] psoralen

C21 H24 O6

71339-34-9

(Murakami et al., 1999)

18

Citrusoside B

C36 H48 O15

1255789-52-6

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

19

Citrusoside C

C31 H40 O15

1255789-53-7

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

20

Citrusoside D

C31 H40 O15

1255789-54-8

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

21

Isoimperatorin

C16 H14 O4

482-45-1

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

22

(+)-Oxypeucedanin hydrate

C16 H16 O6

2643-85-8

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

23

(+)-Oxypeucedanin

C16 H14 O5

3173-02-2

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

24

(R) - (+)-6′-Hydroxy-7′-methoxybergamottin

C22 H26 O6

1255117-90-8

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

25

(R) - (+)-Oxypeucedaninmethanolate

C17 H18 O6

52939-12-5

(Sun et al., 2018)

26

Pangelin

C16 H14 O5

33783-80-1

(Sun et al., 2018)

27

2′-Methoxyoxypeucedanin hydrate

C17 H18 O6

2376519-64-9

(Sun et al., 2018)

28

Xanthotoxol

C11 H6 O4

2009-24-7

(Umran et al., 2020)

Flavonoids

29

Quercetin

C15 H10 O7

117-39-5

(Butryee et al., 2009)

30

Isorhamnetin

C16 H12 O7

480-19-3

(Butryee et al., 2009)

31

Luteolin

C15 H10 O6

491-70-3

(Butryee et al., 2009)

32

Kaempferol

C15 H10 O6

520-18-3

(Butryee et al., 2009)

33

Hesperetin

C16 H14 O6

520-33-2

(Butryee et al., 2009)

34

Apigenin

C15 H10 O5

520-36-5

(Butryee et al., 2009)

35

Myricetin

C15 H10 O8

529-44-2

(Butryee et al., 2009)

36

Tamarixetin

C16 H12 O7

603-61-2

(Butryee et al., 2009)

37

Naringin

C27 H32 O14

10236-47-2

(Butryee et al., 2009)

38

Nobiletin

C21 H22 O8

478-01-3

(Sadasivam et al., 2018)

39

Tangeretin

C20 H20 O7

481-53-8

(Sadasivam et al., 2018)

40

5, 7, 8, 4′-Tetramethoxyflavone

C19 H18 O6

6601-66-7

(Sadasivam et al., 2018)

41

Natsudaidain

C21 H22 O9

35154-55-3

(Sadasivam et al., 2018)

42

5, 6, 4′-Trihydroxypyranoflavone

C20 H16 O6

2166018-83-1

(Sadasivam et al., 2018)

43

5, 4′-Dimethyl-6-prenylpyranoflavone

C27 H30 O3

2169947-22-0

(Sadasivam et al., 2018)

44

Eldrin

C27 H30 O16

153-18-4

(Umran et al., 2020)

45

Hesperidine

C28 H34 O15

520-26-3

(Umran et al., 2020)

46

Diosmin

C28 H32 O15

520-27-4

(Umran et al., 2020)

47

Cosmosiin

C21 H20 O10

578-74-5

(Umran et al., 2020)

48

Saponarin

C27 H30 O15

20310-89-8

(Umran et al., 2020)

49

Apiin

C26 H28 O14

26544-34-3

(Umran et al., 2020)

50

Peonidin

C16 H13 O6

18736-36-2

(Butryee et al., 2009)

51

(-)-Epicatechin

C15 H14 O6

490-46-0

(Butryee et al., 2009)

52

(-)-Epigallocatechin

C15 H14 O7

970-74-1

(Butryee et al., 2009)

53

(-)-Epigallocatechin 3-gallate

C22 H18 O11

989-51-5

(Butryee et al., 2009)

Phenolic acids

54

Vanillic acid

C8 H8 O4

121-34-6

(Butryee et al., 2009)

55

Chlorogenic acid

C16 H18 O9

327-97-9

(Butryee et al., 2009)

56

Caffeic acid

C9 H8 O4

331-39-5

(Butryee et al., 2009)

57

Ferulic acid

C10 H10 O4

1135-24-6

(Butryee et al., 2009)

Terpenoids

58

Isopulegol

C10 H18 O

89-79-2

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

59

Citronellol

C10 H20 O

106-22-9

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

60

Citronellal

C10 H18 O

106-23-0

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

61

Citronellol acetate

C12 H22 O2

150-84-5

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

62

β-Sitosterol

C29 H50 O

83-46-5

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

63

Sitosteryl-β-D-glucopyranoside

C35 H60 O6

474-58-8

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

64

Linalool

C10 H18 O

78-70-6

(Wongsariya et al., 2014)

65

2, 6-Dimethyl-5-heptenal

C9 H16 O

106-72-9

(Wongsariya et al., 2014)

66

Peruviol

C15 H26 O

142-50-7

(Wongsariya et al., 2014)

67

β-Pinene

C10 H16

127-91-3

(Wongsariya et al., 2014)

68

(-)-Caryophyllene oxide

C15 H24 O

1139-30-6

(Wongsariya et al., 2014)

69

Sabinene

C10 H16

3387-41-5

(Wongsariya et al., 2014)

70

β-Caryophyllene

C15 H24

87-44-5

(Sammi et al., 2016)

71

Limonin

C26 H30 O8

1180-71-8

(Sadasivam et al., 2018)

72

Lupeol

C30 H50 O

545-47-1

(Anuchapreeda et al., 2020a, 2020b)

73

Phytol

C20 H40 O

150-86-7

(Anuchapreeda et al., 2020a, 2020b)

74

Agrostophillinol

C31 H53 O

–

(Anuchapreeda et al., 2020a, 2020b)

Other compounds

75

1, 2-Di-O-linolenoyl-3-O-galactopyranosyl-sn-glycerol

C45 H74 O10

63180-02-9

(Murakami et al., 1995)

76

1-O-α-Linolenoyl-2-O-palmitoyl-3-O-β-galactopyranosyl-sn-glycerol

C43 H76 O10

121249-84-1

(Murakami et al., 1995)

77

11-Hydroxynoracronycine

C19 H17 N O4

11361-79-0

(Panthong et al., 2013)

78

(+)-Syringaresinol

C22 H26 O8

487-35-4

(Panthong et al., 2013)

Chemical structure of coumarins isolated from C. hystrix.

3.2.1 Coumarins

Similar to other Citrus plants, coumarins are the main and representative constituents isolated from C. hystrix. To date, 28 kinds of coumarin constituents have been separated from C. hystrix (1–28). Among them, most of compounds are furocoumarins (4, 8, 12, 17–28), other types including simple coumarins (2, 3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16) and pyranocoumarins (1, 6, 11 and 13) are exiting as well. As for the substituted groups, multiple groups including methyl, ethyl, methoxy, isopentenyl and glucosides have been reported in the chemical structure of C. hystrix coumarins, which can be regarded as effective supplements of diversity of constituents of C. hystrix based on the coumarin skeletons. The contents of the coumarins are shown in Table 2 with their chemical structures listed in Fig. 2.

3.2.2 Flavonoids

Abundant flavonoids (29–53) have been separated from C. hystrix. The presence of flavonoids is closely linked to the antioxidant activity of C. hystrix, which provides important insights for the industrial applications of C. hystrix (Alirezalu et al., 2020; Granato et al., 2020). These structures primarily contain the flavonol backbones (29, 30, 32, 35, 36 and 41) and the 2-phenylchromone backbone (31, 34, 38–40, 46–49), which can be distinguished from whether or not there is a hydroxyl group on the C-3 position as a substitution. In addition to the flavonones (33, 37 and 45) that can also be found in constituents of C. hystrix. Anthocyanin derivatives (50–53), a type of positively charged flavonoid that is often considered to be the valuable natural pigment in plants, have been isolated and characterized from C. hystrix as well, most of which are epicatechin analogues (50–53) with dihydroxy groups substituted on 3‘ and 4‘ position of C ring of the anthocyanin scaffold. Table 2 shows the contents of the flavonoids mentioned with their generalized chemical structures in the form of a skeleton in Fig. 2.

3.2.3 Phenolic acids

Four kinds of phenolic acids have been isolated from C. hystrix. The structural identification technologies offer help to definite their name as vanillic acid (54), 4,6,7-trimethoxy-5-chlorogenic acid (55) caffeic acid (56) and ferulic acid (57), which are frequently occurring in functional ingredients of food. Phenolic acids are valuable functional ingredients of food, which have been associated with a variety of activities (Akyol et al., 2016; M'Hiri et al., 2017; Naveed et al., 2018; Romani et al., 2019). The potential bioactivity of phenolic acids from C. hystrix are still waiting for excavating.

3.2.4 Terpenoids

Nineteen kinds of terpenoids (58–74) have been separated from C. hystrix. The structure of the terpenoids have been shown in Fig. 2. Most of terpenoids can be divided into essential oils, lupeol (72) and agrostophillinol (74) are typical tetracyclic triterpenoids, and the compounds like β-sitosterol (62) and sitosteryl-β-D-glucopyranoside (63) are steroids.

3.2.5 Other compounds

Other compounds have been isolated from C. hystrix as well, mainly containing glycosides and other constituents. Murakam and colleagues (Murakami et al., 1995) isolated two sorts of unique glucosides from the leaves of C. hystrix. Two compounds were structurally identified as 1, 2-di-O-linolenoyl-3-O-galactopyranosyl-sn-glycerol (75) and 1-O-α-linolenoyl-2-O-palmitoyl-3-O-β-galactopyranosyl-sn-glycerol (76), respectively. The structure of two glucosides should be noteworthy from the point of view of phytochemistry because the coexistence of the hydrophilic glucoside group and the hydrophobic aliphatic chains gave them potential in terms of their pharmacological properties. This initial experiment proves that these compounds could be inhibitors of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) activation induced by tumor promoters. Additionally, compounds 11-hydroxynoracronycine (77) and (+)-syringaresinol (78) have also been isolated from C. hystrix (Panthong et al., 2013).

4 Progress of pharmacological studies on C. Hystrix

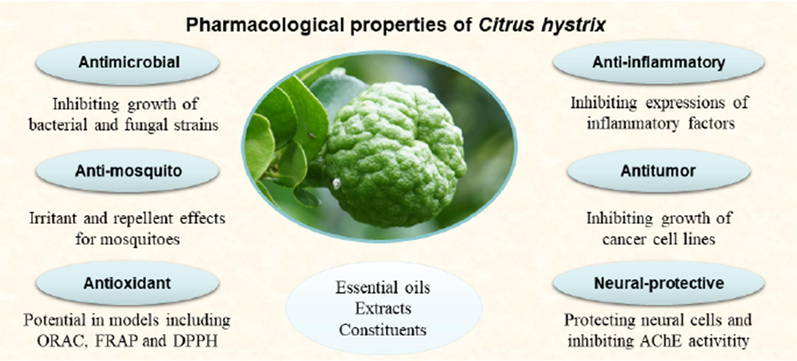

Several studies to date have disclosed biological activities of C. hystrix. These largely effective extractions of constituents perform multiple pharmacological properties, including antimicrobial, anti-mosquito, antioxidant, antitumor, anti-inflammatory and neural-protective properties (Fig. 3). These pharmacological properties are summarized in the following paragraphs, and the recapitulative items is generalized in Table 3.

Pharmacological properties of C. hystrix.

Pharmaceutical effects

Part

Comp./Extract

Model and effective concentrations

Ref.

Antimicrobial

Oils

Active against strains including Staphylococcus epidermidis, Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae

(Waikedre et al., 2010)

Antimicrobial

Roots

14

Active against multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii JVC 1053 (MIC: 100 μg/mL)

(Panthong et al., 2013)

Antimicrobial

Roots

71

Active against multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii JVC 1053 (MIC: 100 μg/mL)

(Panthong et al., 2013)

Antimicrobial

Roots

78

Active against multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii JVC 1053 (MIC: 50 μg/mL)

(Panthong et al., 2013)

Antimicrobial

Leaves

Oils

Active against Trichophyton mentagrophytes (MIC: 1.08 mg/mL)

(Pumival et al., 2020)

Antimicrobial

Peels

Ethanolic fraction

Inhibitory activity towards Salmonella spp

(Ulhaq et al., 2020)

Antimicrobial

Oils

Active against Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (1500–50,000 ppm)

(Chit-aree et al., 2021)

Anti-mosquito

Leaves

Oils

Active against Aedes aegypti and Aedes minimus in the concentrations of 1–5%

(Nararak et al., 2017)

Antioxidant

Leaves

Lipid extracts

Showing antioxidant potential in ORAC and FRAP assay

(Butryee and Lupradinun 2008)

Antioxidant

Roots

77

Showing antioxidant potential in DPPH assay (IC50: 0.19 mg/mL)

(Panthong et al., 2013)

Antioxidant

Roots

78

Showing antioxidant potential in DPPH assay (IC50: 0.032 mg/mL)

(Panthong et al., 2013)

Antitumor

75

Inhibited tumor promoter-induced EBV activation induced by tumor promoters

(Murakami et al., 1995)

Antitumor

76

Inhibited tumor promoter-induced EBV activation induced by tumor promoters

(Murakami et al., 1995)

Antitumor

Peels

Oils

Inhibiting growth of melanoma cells

(Borusiewicz et al., 2017)

Antitumor

8

Inhibited growth of cancer cell line PANC‐1 inducing cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing and organelle disintegration

(Sun et al., 2018)

Antitumor

61

Inducing apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells via inhibiting Bcl-2 and activating caspase-3 dependent pathway

(Ho et al., 2020)

Antitumor

62

Inducing apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells via inhibiting Bcl-2 and activating caspase-3 dependent pathway

(Ho et al., 2020)

Antitumor

Leaves

72

Decreasing the proliferation of leukemic cells

(Anuchapreeda et al., 2020a, 2020b)

Antitumor

Leaves

73

Reducing the proliferation of leukemic cells

(Anuchapreeda et al., 2020a, 2020b)

Antitumor

Leaves

74

Inhibiting growth of lines of acute myeloblastic leukaemia against EoL-1 (36.3 μg/mL) and HL-60 (53.4 μg/mL) cells

(Anuchapreeda et al., 2020a, 2020b)

Anti-inflammatory

Leaves

74

Inhibiting the release of IL-6 and TNF-α

(Anuchapreeda et al., 2020a, 2020b)

Neural-protective

24

Active in AChE inhibition (IC50: 11.2 μM)

(Youkwan et al., 2010)

Neural-protective

60

Active in AChE inhibition

(Sammi et al., 2016)

Neural-protective

Peels and leaves

Extracts

Protecting neuroblastoma cells SH-SY5Y through mediating activation of the SIRT1/GAPDH pathway

(Pattarachotanant and Tencomnao 2020)

4.1 Antimicrobial activity

C. hystrix exerted potential in antimicrobial potency including antibacterial, antifungal and anti‑vibrio activities. Essential oils from C. hystrix were reported to exhibited antimicrobial activity on multiple strains including Staphylococcus epidermidis (diameter of inhibition zone: 7 mm), Candida albicans (minimal inhibitory concentration, MIC: 75 μg/mL), Cryptococcus neoformans (MIC: 50 μg/mL) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (MIC: 50 μg/mL) (Waikedre et al., 2010).

The antibacterial effect of the multiple compounds separated from the roots of C. hystrix were assessed (Panthong et al., 2013). In terms of antimicrobial activity, the compounds 14 and 78 were found to be active against multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii JVC 1053 with the same MIC values for 100 μg/mL, whereas limonin (71) demonstrated improved effect with MIC 50 μg/ml.

In 2014, Wongsariya and co-workers, 2014 disclosed that the oil from the leaves of C. hystrix showed antibacterial potency with MICs of 1.06 mg/mL for Porphyromonas gingivalis and Streptococcus mutans and at 2.12 mg/mL for Streptococcus sanguinis. At a concentration of 4.25 mg/mL, leaf oil exhibited antibiofilm formation effect with 99% inhibitory effects. Lethal effects on P. gingivalis were determined within 2 and 4 h of treatment with 4 × MICs and 2 × MICs, respectively. The results revealed that S. sanguinis and S. mutans were completely killed following the induction of C. hystrix leaf oil. MIC values of the strains tested showed a 4-fold decrease indicating a synergistic interaction of the oil and chlorhexidine. The bacterial outer membrane was disrupted following leaf oil treatment. Furthermore, citronellal (60) was proved to be the essential active constituent of the C. hystrix oils.

Borusiewicz et al. (2017) declared that the essential oil isolated from C. hystrix displayed favorable antibacterial activities. To test the antibacterial effects of the essential oil of C. hystrix, disc diffusion and serial macrodilution assay were used against 50 kinds of multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii strains, which demonstrated its potential as expressed by MIC ranging from 0.125 to 1 μL/mL.

In 2020, Pumival et al. (2020) declared that C. hystrix leaf oil displayed good antifungal activities against Trichophyton mentagrophytes. The antifungal activity of C. hystrix leaf oil and its microemulsion were studied through macrodilution and agar well diffusion methods against T. mentagrophytes (MIC: 1.08 mg/mL). Additionally, the microemulsion of C. hystrix oil also exhibited promising antifungal potency with physical and chemical stability, suggesting an alternative therapeutic agent for T. mentagrophytes.

It was claimed that the ethanolic fraction of C. hystrix peel exhibited inhibitory activity towards Salmonella spp (Ulhaq et al., 2020). The MIC of the extract was tested to be 0.625% using an agar dilution test. To examine the antibacterial activity in vivo, 16 mg of C. hystrix extract was administered daily for 3 consecutive days in a S. typhimurium-infected murine model. The results showed that the bacterial loads of S. typhimurium in the spleen, liver, and ileum reduced after administration of the C. hystrix treatment with statistic differences.

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a marine bacterium that has been shown to opportunistically cause foodborne gastroenteritis in humans and some diseases in marine animals. At an optimal concentration of 50 mg/mL and Broth's micro dilution method (MICs of 50–100 mg/mL), the ethanolic fractions from the peel of Citrus aurantifolia and C. hystrix were proved to be more active in anti-V. parahaemolyticus effects than the other fractions by the Agar disk diffusion method (Singhapol and Tinrat 2020), indicating potentials to be developed as a distinctive candidate for an alternative natural agent for controlling disease spread in shrimp.

In 2021, the potency of C. hystrix essential oil inhibiting Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, the causative agent of anthracnose disease in mango fruit, was studied (Chit-aree et al., 2021).Beta-pinene (67), limonene (71), and citronellol (59) were the major compounds in the essential oil according to the results of constituent analysis. In vitro tests revealed that C. hystrix essential oils (1500–50,000 ppm) exhibited the inhibitory effects against C. gloeosporioides mycelial growth. In vivo efficacy studies have shown that the essential oils of ripe C. hystrix (1500 ppm) inhibited the disease development of C. gloeosporioides, showing that essential oils of C. hystrix could be applied to protect against mango fungal contamination.

Recent research revealed that C. hystrix essential oil was effective for multidrug-resistant (MDR) methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant S. aureus strains (MRSA) (Sreepian et al., 2023). C. hystrix essential oil alone showed antibacterial effect toward all MSSA isolates (MIC: 18.3 mg/mL) and MRSA isolates (MIC: 17.9 mg/mL). Time killing kinetics suggested that C. hystrix essential oil at 1 × MIC completely killed MSSA and MRSA within 12 h. The use of C. hystrix essential oil as an alternative antibacterial agent would reduce the emergence of resistant bacteria, especially MDR MRSA.

4.2 Anti-mosquito activity

At present, over 3500 genera of mosquitoes have been reported (Brisola and Melo, 2016), which play an important role in the transmission of infections to communities (Manguin et al., 2010; Sinka et al., 2010). There is evidence that C. hystrix has repellent activity against mosquitoes such as Aedes aegypti, Anopheles minimus Theobald, and others. In order to demonstrate the potential effectiveness of C. hystrix leaf essential oil as an insect repellent against Aedes aegypti and Aedes minimus, Nararak and colleagues conducted a study (Nararak et al., 2017). C. hystrix leaf oil demonstrated the greatest spatial repellent activity at 1% and 2%, and significant combined irritant and repellent activity responses at 1–5% concentrations. C. hystrix oils were confirmed to show more inhibition against A. minimus mosquitoes than A. aegypti mosquitoes.

In 2016, Nishan et al. (2017) disclosed that ethanolic extracts of pulps of Citrus aurantifolia and C. hystrix exerted favorable larvicidal activity against 3rd and 4th instar of A. aegypti larvae. When dosed at 3.75 mg/mL, the C. hystrix extract resulted in 66.70% mortality over a 24 h period whereas. Furthermore, the percentage mortality caused by C. hystrix was 56.70% at the dosage of 3.75 mg/mL for 24 h, both botanical extracts show similar results to the synthesis products at the concentration of 3.75 mg/mL for 72 h. Through the nut shell methods, it was found that extracts of C. aurantifolia and C. hystrix also had larvicidal activity, suggesting that they should be further developed as larvicidal agents.

4.3 Antioxidant activity

As with other functional food resources, it was widely reported that C. hystrix also exhibited antioxidant activity. The task forces of Chaniphun Butryee made relentless efforts in this area. The leaf of C. hystrix was disclosed in 2008 to show total antioxidant capacities (TAC) in vitro as well as clastogenic and anticlastogenic potency in vivo via the erythrocyte micronucleus assay in mice (Butryee and Lupradinun, 2008). Two different assays, including oxygen radical uptake capacity (ORAC) and ferric reducing antioxidant potency (FRAP), were used to evaluate the antioxidant effects of the aqueous extracts and the lipid extracts of C. hystrix. On the basis of these findings, the TAC values assessed by ORAC and FRAP were determined to be 433 μM Trolox Equivalent/g and 95 μM Fe2+ Equivalent/g, respectively. In 2009, the task group investigated the potency of the treatment on content of flavonoids and antioxidant capacity of the C. hystrix (Butryee et al., 2009). The results revealed that boiling reduced TAC values in the trials, the order of TACs: fresh > deep-fat frying > boiling.

The antioxidant activities of the benzene, coumarin, and quinolinone derivatives with 33 kinds of known compounds separated from C. hystrix roots were assessed (Panthong et al., 2013). Compounds 77 and 78 showed antioxidant activity in 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl scavenging activity (DPPH) test with IC50 values of 0.19 and 0.032 mg/mL, respectively. Compound 78 was a potential superoxide scavenger (IC50: 1.52 mg/mL) as well. The activity of compounds 77 and 78 was lower than that of the crude extract, suggesting a synergistic potency in this compound.

In 2015, leaf C. hystrix extract was subjected to a comparative evaluation of a preliminary phytochemical screen as well as in vitro antioxidant effects (Ali et al., 2015). In a phytochemical research part, leaf extracts of C. hystrix were suggested to contain alkaloids, carbohydrates, flavonoids, glycosides, phenolic compounds, steroids and tannins. As for the evaluation of antioxidants in vitro, all forms of C. hystrix extract had a significant positive effect through the evaluation of free radical scavenging activity of DPPH, Cupric Reducing Antioxidant Capacity (CUPRAC), Nitric oxide scavenging assay. And it was observed that the total antioxidant capacity of the fractions decreased in the following order: ethanol extract > chloroform extract > methanol extract.

In 2023, C. hystrix extract showed antioxidant activity through mediating cell migration on human keratinocytes and fibroblasts (Ratanachamnong et al., 2023). In vitro, C. hystrix water extract displayed free radical scavenging capacity in DPPH assay (IC50: 14.91 mg/mL), and nitrite radical scavenging capacity using NO assay (IC50: 4.46 mg/mL). Treatment of C. hystrix extract as low as 50 μg/mL decreased the reactive oxygen species (ROS) from H2O2-induced ROS formation. C. hystrix extract dose-dependently promoted cell migration. The results demonstrated the positive benefit of C. hystrix water extract as a wound-healing accelerator.

4.4 Antitumor activity

Based on the available literature, C. hystrix appears to have great potential as an anticancer therapeutic agent. Compounds 75 and 76 along with their derivatives were prepared from C. hystrix (Murakami et al., 1995). Both compounds 75 and 76 exhibited potential to inhibit tumor promoter-induced Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) activation induced by tumor promoters with lower IC50 values compared to representative cancer preventive agents. In a two-step carcinogenesis experiment performed on the skin of ICR mice induced by dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) and 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA), compound 75 showed antitumor activity at a dose ten times lower than α-linolenic acid. Compounds 75 and 76 displayed stronger inhibitory effects than indomethacin in the anti-inflammation assay using edema formation induced by TPA on mouse ears. The release of arachidonic acid by phospholipase A2 triggers inflammation induced by the tumor promote. The anti-inflammatory properties of glyceroglycol lipids may be caused by the suppression of enzymes controlling such pathways.

In 2015, the antitumor potency of the C. hystrix leaf extracts was determined using a 3- (4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay in an attempt to investigate the cytotoxic effects of C. hystrix extracts on cervical cancer cell lines and neuroblastoma cells (Tunjung et al., 2014). Based on the results, the ethyl acetate fraction of C. hystrix leaf showed antitumor potential with IC50 values for HeLa, UKF-NB3, IMR-5, and SK-N-AS parent cells of 40.7 μg/mL, 28.4 μg/mL, 14.1 μg/mL, and 25.2 μg/mL, respectively.

According to Borusiewicz et al. (2017), peel of C. hystrix essential oils showed good antitumor activity. In their study, the authors present firstly an anti-proliferative and cytotoxic potency of C. hystrix essential oils against human melanoma cells (WM793 and A375) as well as fibroblasts from normal human skin. Also, the acquired findings have shown that the oil has an inhibitory impact in the investigated dosages (0.05, 0.1 and 0.15 mg/mL). Of particular interest was the finding that both melanoma cell lines (WM793 and A375) were more sensitive to the effect of C. hystrix peel essential oil than were normal cells such as fibroblasts from human skin.

In 2018, Suresh Awale task group (Sun et al., 2018) isolated and identified ten genera of coumarins from C. hystrix, of which bergamottin (8) was found to be the most promising compound against the human pancreatic cancer cell line PANC‐1. Further molecular biology studies indicated that compound 8 induced cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing and organelle disintegration, the migration of PANC-1 cells and colony formation was suppressed by compound 8 as well. In addition, compound 8 was shown to down-regulate the levels of proteins in the Akt/mTOR signaling, suggesting potential for development as pancreatic cancer candidates.

In 2020, C. hystrix leaves extracts and potential compounds citronellol (59) and citronellal (60) from essential oil were disclosed to suppress the growth of MDA-MB-231 cancer cell line (Ho et al., 2020). Extracts of C. hystrix, compounds 59 and 60 were evaluated in vitro against the MDA-MB-231 cells through multiple molecular biology methods. Results revealed that C. hystrix extracts, 59 and 60 decreased cell proliferation, colony formation and cell migration by inducing cell cycle arrest, as well as inducing apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 cells via inhibition of the expression of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2, activiting the caspase-3 dependent pathway.

Constituents from extracts of C. hystrix leaves have been shown to display antileukemic cell proliferation (Anuchapreeda et al., 2020a, 2020b). This proved that hexane fraction exhibited the best inhibition on levels of WT1 of several leukemia cell lines and reduced expression of WT1 protein levels from K562 cells. It was confirmed that phytol (73) and lupeol (72) isolated from the extracts were the anti-proliferative agents for decreasing the proliferation of leukemic cells tested by the bioassay. And a further study was the first report showing anticancer activity of agrostophillinol (74) that had been isolated from the leaves of C. hystrix in the blood (Anuchapreeda et al., 2020a, 2020b). It is important to note that 74 was nontoxic to normal cells (e.g., PBMCs). Compound 74 was tested to show inhibition against acute myeloblastic leukaemia cell lines like EoL-1 (IC50: 36.3 μg/mL) and HL-60 cells (IC50: 36.3 μg/mL). The anti-leukemic and anti-inflammatory activities of 74 were confirmed by biological assays against leukemic cells.

4.5 Anti-inflammatory activity

Th The development of anti-inflammatory agents is closely linked to public health due to the extensive links between the inflammatory response and multiple morbidities (Zhao et al., 2020). Several constituents isolated from C. hystrix were reported to show anti-inflammatory potency in different models (Murakami et al., 1999). A cluster of coumarins were separated and characterized from C. hystrix with significant anti-inflammatory activities. The inhibitory effect of bergamottin (8, IC50: 14 µM) was close to the reference standard N-(iminoethyl)-ornithine (IC50: 7.9 µM), whereas other monomers structurally different from compound 8 only in their side-chain moieties, were notably less active.

The isolation of agrostophillinol (74) from C. hystrix leaves and its anti-inflammatory activity was firstly reported (Anuchapreeda et al., 2020a, 2020b).The IC20 values of compound 74 and C. hystrix leaf extracts (2.7 and 90 μg/mL, respectively) were used as test dosages to evaluate the inhibitory effects on IL-6 and TNF-α. At the same dosage, compound 74 (2.7 μg/mL) showed more significant IL-6 inhibitory effects than the reference standard dexamethasone, indicating that promising anti-inflammatory potential against IL-6-induced inflammation.

4.6 Neural-protective activity

Several neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's, Huntington's, and Parkinson's disease, as well as several mental conditions, such as schizophrenia, affect cholinergic neurotransmission. The majority of these disorders are now treated with drugs that aim to increase neurotransmission by either decreasing acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity or by positively modulating cholinergic receptors (Sammi et al., 2016). C. hystrix has been reported to show AChE inhibitory activity in previous researches.

Derivatives of furanocoumarin were isolated from C. hystrix in 2010 and assessed for cholinesterase inhibitory activity (Youkwan et al., 2010), among which compound 24 showed the strongest AChE inhibition with an IC50 value of 11.2 μM, indicating promising potency curing Alzheimer's disease. Initial Structure-Activity Relationship can be generalized as the presence of a deoxygenated geranyl chain in the isolated constituents was found to be important for the inhibitory effect.

In 2016, Sammi and his colleagues (2016) determined the synaptic Ach levels evident using aldicarb assay, following treatment with C. hystrix extract being orchestrated by the attenuation of AChE activity, recorded at levels of genomic and biochemical, as well as high genomic expression of the choline transporter. Based on this result, it was found that the active components citronellal (60) extracted from C. hystrix was able to inhibit the activity of AChE at both biochemical and transcriptomic levels, moreover, it can also possess its function through regulating the genomic levels of choline transporter and choline acetyltransferase.

In terms of enzyme-inhibiting effects, in 2014 (Abirami et al., 2014), fresh juice from C. hystrix fruit was shown to inhibit multiple enzymes including α-amylase, α-glucosidase, tyrosinase, AChE, β-glucuronidase with an inhibitory ratio ranging from 60% to 80%, respectively, indicating a good potential in the development of healthcare production.

In 2020, the anti-senescent mechanisms of C. hystrix extracts were investigated through human neuroblastoma cells SH-SY5Y (Pattarachotanant and Tencomnao 2020). The effects of C. hystrix extracts on high glucose-induced cytotoxicity, generation of ROS, cell cycle arrest, and cell cycle associated proteins were evaluated. This result showed that the neuroprotective effects of C. hystrix peel and leaf extracts were mediated through cell cycle progression in cell cycle checkpoint proteins and the up regulation of SIRT1 following activation of the SIRT1/GAPDH pathway. Extracts of C. hystrix can be developed as agents to protect neuronal senescence induced by high glucose. And diseases associated with neuronal senescence will hopefully be clarified in future research.

4.7 Other activities

Apart from the activities introduced above, other activities of C. hystrix have also been explored. In 2015, Ali et al. (2015) evaluated the thrombolytic and membrane-stabilizing activities of C. hystrix leaf extracts using human erythrocytes, and the results were compared with those of standard streptokinase (SK) and acetyl salicylic acid (ASA), respectively. The results of this study are presented in Table 3. In terms of thrombolytic activity and membrane stabilizing effects, ethanolic leaf fraction had a clot lysing value of 13.69% against standard SK (37.43 %) and a highest percentage hemolytic value of 74.40% against standard ASA (93.24%), respectively.

C. hystrix was reported to show skin-stimulating effects. In 1999 (Koh and Ong, 1999), a case report disclosed that the phytophotodermatitis on a hiker caused by the application of the juice of C. hystrix because of the abundant content of psoralens, suggesting the more attention should be paid in the application of C. hystrix productions. In 2007 (Hongratanaworakit and Buchbauer, 2007), C. hystrix oil was demonstrated to promote the blood pressure and reduce the skin temperature.

5 Industrial applications

Industrial applications of C. hystrix in the food service industry offer a novel choice for people to choose health care foods such as beverages that contain certain C. hystrix derivatives (Table 4). In addition, C. hystrix is used in the cosmetics industry, several patents have disclosed the potential of C. hystrix to be developed as skin or hair care agent (CN104379219, JP2001031528A, TW201740922A, JP2004083416A, JP2011016756A, US6426080B1, JPH11199427A). Industrial applications more extensive, correspondent advanced extraction conditions are urgently needed (Lubinska-Szczygel et al., 2023). Extraction methods reported in published studies mainly contain water and ethanol extracts, acid extraction conditions and suitable temperature (60–90 °C) are favorable for the retention of effective substances. With the development of pharmacological related technologies, more and more C. hystrix based functional products will be developed in the future.

Application

Main composition

Properties

Publish number

Hair products

Boiled C. hystrix without seeds

Stimulating the hair growth and colored

CN104379219

Hair products

C. hystrix extracts

Providing a safe hair restorer effect without allergic reaction to the scalp

JP2001031528A

Skin care agent

C. hystrix honey, glycerinum

Preserving skin moisture and reducing the side effects

TW201740922A

Skin care agent

C. hystrix extracts

Accelerating the action of collagen and hyaluronic productions

JP2004083416A

Skin care agent

C. hystrix extracts

Melanin inhibitory effect with formulation stability

JP2011016756A

Skin care agent

C. hystrix extracts

Natural products as cosmetic substances with high protection factor against free radicals

US6426080B1

Skin care agent

C. hystrix leaves extracts

Active in antioxidant effects

JPH11199427A

Skin care agent

C. hystrix leaves extracts

Reducing moisture content of horny layer from getting rough

JP2022087646A

Treating skin and hair damages agents

Peel or leaf extracts of C. hystrix

Natural products as radical scavengers for protecting and treating skin and hair damages

KR101159392B1

Detergent

Fermented C. hystrix with rock salt and surfactant

Cleaning with less environmental impact and less rough skin

JP2007270134A

Herbal smoking blend

Essential oil of C. hystrix as additive agent

Providing herbal terpenoid solution to improve taste

US9532593B2

Tea beverage

Extracts of C. hystrix as additive agent

Quickly preparing a cup of tea with good taste and aroma

RU2690651C2

Flavor modifying composition

C. hystrix extracts

Natural products as flavor modifying composition

CN106998761A

Promoting small intestinal motility agent

Constituents isolated from C. hystrix

Promoting small intestinal motility for further drug development

CN105168200A

Medicated toothpaste inhibiting plaque

Polygonatum cyrtonema extracts and C. hystrix extracts

Natural products as ingredients of toothpaste inhibiting plaque

CN108354875A

Weight loss products

Extracts of C. hystrix as additive agent

Natural products as lipase inhibitor

WO2010010949A1

Adipocyte differentiation inhibitor

C. hystrix extracts

Natural products as adipocyte differentiation inhibitor

JP4363825B2

Carcinogenic promotion-inhibiting agent

C. hystrix extracts

Inhibiting the activation of Epstein-Barr virus via the promoter teleocidin B-4

JPH06336437A

Antiviral agents

C. hystrix essential oil

Natural products as antiviral agents for multiple virus

EP3964221A1

Antiplasmin agent

C. hystrix extracts

Natural products as antiplasmin agent

CN114007632A

Detergent

Fermented C. hystrix with rock salt and surfactant

Cleaning with less environmental impact and less rough skin

JP2007270134A

Cleansing skin dried pad

C. hystrix extracts

Cleaning skin with minimizes irritation

KR20210017704A

Mosquito repellent

C. hystrix extracts

Natural products as ingredients of mosquito repellent

WO2017168449A1

6 Conclusion

The purpose of this review was to summarize the phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, and industrial applications of C. hystrix based on published literatures. Current studies on C. hystrix mostly focus on the components found in leaves or fruits, but more research into other elements and other plant parts is urgently needed because the current findings are ambiguous and inadequate. Studies of biological activity must be combined with clinical application research that focuses on the structural underpinnings of its efficacy. As for the pharmacological studies, C. hystrix has been proved to show potential to be developed as drug candidates for multiple disorders. However, most of the studies conducted thus far are still at the initial stages of using crude extracts in vitro. In vivo investigations should be conducted to confirm the observed in vitro effects (Siti et al., 2022). Bioactive compounds should although though C. hystrix has been utilized widely as a food and medicine source, there is still a lack of safety data, and there have only been a few toxicity studies conducted. Thus, more toxicological research is also necessary.

In summary, C. hystrix has a wide range of bioactivities, making it a kind of important edible medicinal plant resource deserving of further study. Unfortunately, there is not enough information available on clinical value about C. hystrix. Multiple constituents have been identified from C. hystrix, although research on these components may just be at the beginning of the story. Future study will likely concentrate on comprehensive phytochemical analyses of C. hystrix and its pharmacological characteristics, particularly its bioactivity mechanism, to show its ethnomedicinal applicability and to help the creation of new pharmaceuticals. Development and application of C. hystrix should be facilitated by this paper.

Author agreement

All the authors agree to publish the article on the Arabian Journal of Chemistry.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 8210142829), Shaanxi Province Department of Education Fund (no. 21JS020), Natural science basic research project of Shaanxi Province (no. 2022JQ-823) and Program for Meridian-Viscera Correlationship Innovative Research Team of Shaanxi University of Chinese Medicine (YL-09).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- In vitro antioxidant, anti-diabetic, cholinesterase and tyrosinase inhibitory potential of fresh juice from Citrus hystrix and C.maxima fruits. Food Sci. Hum. Well.. 2014;3:10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenolic compounds in the potato and its byproducts: an overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016:17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical composition, antioxidant and antiproliferative activities of Citrus hystrix, Citrus limon, Citrus pyriformis, and Citrus microcarpa leaf essential oils against human cervical cancer cell line. Plants-Basel.. 2023;12(1):134.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies of preliminary phytochemical screening, membrane stabilizing activity, thrombolytic activity and in-vitro antioxidant activity of leaf extract of Citrus hystrix. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Res.. 2015;6:2367-2374.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical constituents, advanced extraction technologies and techno-functional properties of selected Mediterranean plants for use in meat products. A comprehensive review. Trends Food Sci. Tech.. 2020;100:292-306.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and biological activity of agrostophillinol from Kaffir Lime (Citrus hystrix) leaves. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2020;30(14):127256

- [Google Scholar]

- Antileukemic cell proliferation of active compounds from Kaffir Lime (Citrus hystrix) leaves. Molecules. 2020;25(6):1300.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cytostatic, cytotoxic, and antibacterial activities of essential oil isolated from Citrus hystrix. Sci. Asia. 2017;43:96-106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Zika virus in Brazil and the danger of infestation by Aedes (Stegomyia) mosquitoes. Rev. Soc. Brasil. Med. Trop.. 2016;49:4-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant capacity of Citrus hystrix leaf using in vitro methods and their anticlastogenic potential using the erythrocyte micronucleus assay in the mouse. Toxicol. Lett.. 2008;180:S79-S.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of processing on the flavonoid content and antioxidant capacity of Citrus hystrix leaf. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr.. 2009;60:162-174.

- [Google Scholar]

- Valorization and biorefinery of kaffir lime peels waste for antifungal activity and sustainable control of mango fruit anthracnose. Biomass Convers. Bior.. 2021;13(2):1-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Is a higher ingestion of phenolic compounds the best dietary strategy? A scientific opinion on the deleterious effects of polyphenols in vivo. Trends Food Sci. Tech.. 2020;98:162-166.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer effect of Citrus hystrix DC. leaf extract and its bioactive constituents citronellol and citronellal on the triple negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cell line. Pharmaceuticals.. 2020;13:476-492.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and stimulating effect of Citrus hystrix oil on humans. Flavour Frag. J.. 2007;22:443-449.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytophotodermatitis due to the application of Citrus hystrix as a folk remedy. Brit. J. Dermatol.. 1999;140:737-738.

- [Google Scholar]

- Edible medicinal and non-medicinal plants: volume 4, fruits. Citrus Hystrix 2012:634-643.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of the major by-products of Citrus hystrix peel and their characteristics in the context of utilization in the industry. Molecules. 2023;28(6):2596.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review on global co-transmission of human Plasmodium species and Wuchereria bancrofti by Anopheles mosquitoes. Infect. Genet. Evol.. 2010;10:159-177.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical characteristics of citrus peel and effect of conventional and nonconventional processing on phenolic compounds: a review. Food Rev. Int.. 2017;33:587-619.

- [Google Scholar]

- Glyceroglycolipids from Citrus hystrix, a traditional herb in Thailand, potently inhibit the tumor-promoting activity of 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate in mouse skin. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 1995;43:2779-2783.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of coumarins from the fruit of Citrus hystrix DC as inhibitors of nitric oxide generation in mouse macrophage RAW 264.7 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 1999;47:333-339.

- [Google Scholar]

- Excito-repellency of Citrus hystrix DC leaf and peel essential oils against Aedes aegypti and anopheles minimus (Diptera: Culicidae), vectors of human pathogens. J. Med. Entomol.. 2017;54:178-186.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chlorogenic acid (CGA): A pharmacological review and call for further research. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2018;97:67-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toxicity of Citrus aurantifolia and Citrus hystrix against Aedes albopictus larvae. Int. J. Biosci.. 2017;10:48-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Benzene, coumarin and quinolinone derivatives from roots of Citrus hystrix. Phytochemistry. 2013;88:79-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Citrus hystrix extracts protect human neuronal cells against high glucose-induced senescence. Pharmaceuticals.. 2020;13(10):283.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal activity and the chemical and physical stability of microemulsions containing Citrus hystrix DC leaf oil. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2020:15.

- [Google Scholar]

- HPLC analysis and in vitro antioxidant mediated through cell migration effect of C.hystrix water extract on human keratinocytes and fibroblasts. Heliyon. 2023;9(2):e13068

- [Google Scholar]

- Health effects of phenolic compounds found in extra-virgin olive oil, by-products, and leaf of Olea europaea L. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1776.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical constituents from dietary plant Citrus hystrix. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2018;32:1721-1726.

- [Google Scholar]

- Citrus hystrix-derived 3,7-dimethyloct-6-enal and 3,7-dimethyloct-6-enyl acetate ameliorate acetylcholine deficits. RSC Adv.. 2016;6:68870-68884.

- [Google Scholar]

- Virulence genes analysis of vibrio parahaemolyticus and anti-vibrio activity of the Citrus Extracts. Curr. Microbiol.. 2020;77:1390-1398.

- [Google Scholar]

- The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in the Americas: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic precis. Parasite Vector.. 2010;3

- [Google Scholar]

- Potential therapeutic effects of Citrus hystrix DC and its bioactive compounds on metabolic disorders. Pharmaceuticals.. 2022;15(2):167.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial efficacy of Citrus hystrix (makrut lime) essential oil against clinical multidrug-resistant methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus isolates. Saudi Pharm J.. 2023;31:1094-1103.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents of Thai Citrus hystrix and their anti-austerity activity against the PANC-1 human pancreatic cancer cell line. J. Nat. Prod.. 2018;81:1877-1883.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tunjung, W.A.S., Cinatl, J., Michaelis, M., Smales, C.M., 2014. Anti-cancer effect of Kaffir Lime (Citrus hystrix DC) leaf extract in cervical cancer and neuroblastoma cell lines. 2nd Humboldt Kolleg in Conjunction with International Conference on Natural Sciences (HK-ICONS), Batu, Indonesia.

- Antibacterial activity of Citrus hystrix toward Salmonella spp. infection. Enferm. Infec. Micr. Cl.. 2020;39:283-286.

- [Google Scholar]

- Citrus hystrix leaf extract attenuated diabetic-cataract in STZ-rats. J. Food Biochem.. 2020;44:e13258.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the essential oils from New Caledonian Citrus mucroptera and Citrus hystrix. Chem. Biodivers.. 2010;7:871-877.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic interaction and mode of action of Citrus hystrix essential oil against bacteria causing periodontal diseases. Pharm. Biol.. 2014;52:273-280.

- [Google Scholar]

- Citrusosides A-D and furanocoumarins with cholinesterase inhibitory activity from the fruit peels of Citrus hystrix. J. Nat. Prod.. 2010;73:1879-1883.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pyrazolone structural motif in medicinal chemistry: Retrospect and prospect. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2020;186:111893

- [Google Scholar]