Translate this page into:

Corrosion inhibitory action of some plant extracts on the corrosion of mild steel in acidic media

*Corresponding author. Tel.: +966 1 4675910; fax: +966 1 4675992 khathlan@ksu.edu.sa (H.Z. Alkhathlan)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Available online 8 Februray 2012

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The alcoholic extracts of eight plants namely Lycium shawii, Teucrium oliverianum, Ochradenus baccatus, Anvillea garcinii, Cassia italica, Artemisia sieberi, Carthamus tinctorius, and Tripleurospermum auriculatum grown in Saudi Arabia were studied for their corrosion inhibitive effect on mild steel in 0.5 M HCl media using the open circuit potential (OCP), Tafel plots and A.C. impedance methods. All the plant extracts inhibited the corrosion of mild steel in acidic media through adsorption and act as mixed-type inhibitors.

Keywords

Biomaterials

Corrosion

Electrochemical techniques

Organic compounds

1 Introduction

Industries depend heavily on the use of metals and alloys. One of the most challenging and difficult tasks for industries are the protection of metals from corrosion. Corrosion is a ubiquitous problem that continues to be of great relevance in a wide range of industrial applications and products; it results in the degradation and eventual failure of components and systems both in the processing and manufacturing industries and in the service life of many components. Corrosion control of metals and alloys is an expensive process and industries spend huge amounts to control this problem. It is estimated that the cost of corrosion in the developed countries such as the U.S. and European Union is about 3–5% of their gross national product (Bhaskaran et al., 2005; Economic Effects of Metallic Corrosion in the United States, 1978a,b). Corrosion damage can be prevented by using various methods such as upgrading materials, blending of production fluids, process control and chemical inhibition (Dudukcu et al., 2004; Galal et al., 2005). Among these methods, the use of corrosion inhibitors (Raja and Sethuraman, 2008; De Souza and Spinelli, 2009) is the best to prevent destruction or degradation of metal surfaces in corrosive media. The use of corrosion inhibitors is the most economical and practical method in reducing corrosive attack on metals. Corrosion inhibitors are chemicals either synthetic or natural which, when added in small amounts to an environment, decrease the rate of attack by the environment on metals. A number of synthetic compounds (Dudukcu et al., 2004; Galal et al., 2005; Ajmal et al., 1994; Bentiss et al., 2002; Abd El-Maksoud, 2004; Li et al., 2003; Kilmartin et al., 2002; Nishimura and Maeda, 2004) are known to be applicable as good corrosion inhibitors for metals. Nevertheless, the popularity and use of synthetic compounds as a corrosion inhibitor is diminishing due to the strict environmental regulations and toxic effects of synthetic compounds on human and animal life. Consequently, there exists the need to develop a new class of corrosion inhibitors with low toxicity, eco-friendliness and good efficiency.

Throughout the ages, plants have been used by human beings for their basic needs such as production of food-stuffs, shelters, clothing, fertilizers, flavors and fragrances, medicines and last but not least, as corrosion inhibitors. The use of natural products as corrosion inhibitors can be traced back to the 1930’s when plant extracts of Chelidonium majus (Celandine) and other plants were used for the first time in H2SO4 pickling baths (Sanyal, 1981). After then, interest in using natural products as corrosion inhibitors increased substantially and scientists around the world reported several plant extracts (El-Etre and Abdallah, 2000; Chetouani and Hammouti, 2003; Hammouti et al., 1997; Kliskic et al., 2000; Abdel-Gaber et al., 2006, 2008, 2009; Benabdellah et al., 2006; El-Etre et al., 2005; Zucchi and Omar, 1985; Abiola et al., 2007; Oguzie, 2006, 2007, 2008; Raja and Sethuramam, 2009; Grassino et al., 2009; Buchweishaija and Mihinji, 2008; Oguzie et al., 2006; Morad et al., 2002) and phytochemical leads (De Souza and Spinelli, 2009; Abdel-Gaber et al., 2009; Abiola et al., 2007; Oguzie, 2007; Raja and Sethuramam, 2009; Awad, 2006) as promising green anticorrosive agents. Although, a number of plants and their phytochemical leads have been reported as anticorrosive agents, vast majority of plants have not yet been properly studied for their anti-corrosive activity. For example, of the nearly 300,000 plant species that exist on the earth, only a few (less than 1%) of these plants have been completely studied relative to their anticorrosive activity. Thus, enormous opportunities exist to find out novel, economical and eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors from this outstanding source of natural products.

In order to find out non-toxic, cheap and effective green corrosion inhibitors from renewable sources, in the present study, we report the corrosion inhibitive effect of eight plants namely Lycium shawii (L.S.), Teucrium oliverianum (T.O.), Ochradenus baccatus (O.B.), Anvillea garcinii (A.G.), Cassia italica (C.I.), Artemisia sieberi (A.S.), Carthamus tinctorius (C.T.) and Tripleurospermum auriculatum (T.A.) grown in Saudi Arabia. Perusal of literature revealed that these plants have never been studied for their corrosion inhibition properties which prompted us to carry out corrosion inhibition evaluation of these plants on mild steel in 0.5 M HCl solution using open circuit potential (OCP), Tafel plots and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) methods.

2 Experimental

2.1 Collection of plant material and preparation of plant extracts

The aerial parts of L. shawii (L.S.), T. oliverianum (T.O.), O. baccatus (O.B.), A. garcinii (A.G.), C. italica (C.I.), A. sieberi (A.S.), C. tinctorius (C.T.) and T. auriculatum (T.A.) plants were collected from Riyadh, Central region of Saudi Arabia in December, 2004 and identified at the Botany department herbarium, King Saud University, Riyadh. A voucher specimen of all the plants has been maintained in our laboratory. Five hundred gram shade air-dried and powdered aerial parts of each plant were first defatted with petroleum ether (60–80 °C) three times at room temperature for 72 h each. The defatted plant materials were then extracted with chloroform and then finally with 95% ethanol three times at room temperature for 72 h each. The combined alcoholic extracts of each plant were concentrated under vacuum at 40 °C until solvents were completely removed. These dried alcoholic extracts of each plant were used for corrosion inhibition activity tests.

2.2 Materials and solution preparation

The material used for constructing the working electrode was mild steel with chemical composition (wt.%) as follows; Fe-99.14, C-0.15, Mn-0.6, P-0.04, S-0.04, Si-0.03. The exposed area (0.785 cm2) was mechanically abraded with a series of emery papers of variable grades, starting with a coarse one (600) and proceeding in steps to the finest (1000) grade. The sample was then washed thoroughly with double distilled water and degreased with acetone just before insertion in the cell. All chemicals, reagents used were of analytical grade and double distilled water was used for preparing solutions. The dried alcoholic extracts of each plant were used for the preparation of inhibitor test solutions in the concentration range of 0.01 g/100 ml solution of 0.5 M HCl.

2.3 Electrochemical studies

The electrochemical measurements along with EIS were carried out with potentiostat interfaced with a computer. OCP versus time and potentiodynamic polarization curves were recorded in agreement with the ASTM G5 norm (American Society for Testing and Materials, 1978). Briefly, the OCP was measured for 30 min before starting the EIS which was carried out at the open-circuit potential in the frequency range 30–10 mHz with a sine wave of 10 mV amplitude. Finally, the Tafel plots experiment was made by scanning the potential from negative to the OCP previously measured while the final potential was positive. The potential range was ±250 mV versus OCP at a scan rate of 1 mV/s.

2.4 Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis was carried out using a Shimadzu QP 5050A gas chromatograph equipped with non polar fused silica capillary DB-1 column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d.; film thickness 0.25 μm). The oven temperature was programmed from 50 to 290 °C at the rate of 4 °C/min and finally held isothermally for 10 min. The injector and detector temperatures were kept at 250 and 300 °C, respectively. Helium was used as a carrier gas at a flow rate of 1 mL/min; splitting ratio was: 100:1. The Mass spectral ionization temperature was set at 230 °C. The mass spectrometer was operated in the electron impact ionization mode at a voltage of 70 eV. Mass spectra were taken over the m/z range 30–700 amu. Individual components of each plant extracts were identified by WILEY and NIST database matching and by comparison of mass spectra with published data (Adams, 2001).

3 Results and discussion

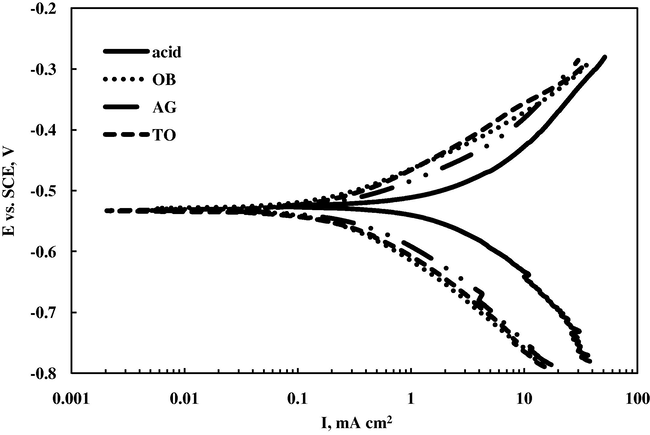

Alcoholic extracts of eight Saudi Arabian plants were tested for their corrosion inhibition properties for the corrosion of mild steel in aggressive media of 0.5 M HCl. The corrosion inhibition effect of these plants were investigated using open circuit potential (OCP), Tafel plots and A.C. impedance methods. OCP values in the presence of plant extracts shifted to more positive potential with time compared to those of acid solution (Table 1). For example, the steady state value of OCP for mild steel in blank solution was −543 mV whereas, in the presence of plant extracts it shifted toward the positive direction to −533 ± 4 mV. Thus, the shift in the steady state value of OCP in the presence of plant extracts was about 10 mV. This slight OCP displacement (∼10 mV) in the presence of plant extracts suggests that all the plant extracts act as mixed-type corrosion inhibitors. As it is known that only when change in OCP value is more than 85 mV it can be recognized as a classification evidence of a compound as an anodic or a cathodic type inhibitor (Riggs Jr., 1973). Typical Tafel plots for the corrosion of mild steel in 0.5 M HCl and in the presence of alcoholic extracts of some selected plants are shown in Fig. 1 whereas their electrochemical parameters are given in Table 1.

Extracts

OCP (mV)

Ecorr (mV)

βc (mV/dec)

βa (mV/dec)

Icorr (Acm−2 × 10−3)

IE (%)

0.5 M HCl

−543

−529

−320

259

4.659

–

L.S.

−534

−519

−184

141

0.68

85.4

T.O.

−532

−525

−234

148

1.23

73.6

O.B.

−532

−520

−207

138

0.71

84.7

A.G.

−535

−529

−247

174

1.28

72.5

C.I.

−536

−529

−203

140

1.77

62.0

A.S.

−536

−524

−131

112

0.42

90.9

C.T.

−531

−527

−127

109

0.51

89.1

T.A.

−531

−518

−119

108

0.42

91.0

Typical Tafel plots for mild steel in 0.5 M HCl and in the presence of 0.01 g/100 ml of alcoholic extracts of OB, AG and TO.

The displayed data clearly show that the corrosion current density (Icorr) values decreased in the presence of plants’ alcoholic extracts indicating that the corrosion process of mild steel was suppressed in the presence of plant extracts. However, the lowest Icorr values were observed in the presence of extracts of A.S. and T.A. suggest that these two plant extracts possess strongest inhibitive properties in comparison to other studied plant extracts. The percentage inhibition efficiency (IE %) for each plant extract was calculated using the relationship given below and their values are mentioned in Table 1:

From Table 1 it is evident that the highest inhibition efficiency was obtained for alcoholic extract of plants A.S. and T.A. (90.9%) followed by C.T. (89.0%), L.S. (85.4%), and O.B. (84.7%) suggesting that these plant extracts could serve as effective green corrosion inhibitors.

It is a known fact that adsorption of the inhibitors is the main process affecting the corrosion rate of metals. Inhibition adsorption can affect the corrosion rate in two possible ways (Riggs Jr., 1973). In first way, inhibitors decrease the available reaction area through adsorption on the metal which is called geometric blocking effect. In second way, inhibitors modify the activation energy of the cathodic and/or anodic reactions occurring in the inhibitor-free metal in the course of the inhibited corrosion process which is called energy effect. It is a difficult task to determine which aspects of the inhibiting effect are connected to the geometric blocking action and which are connected to the energy effect. Theoretically, no shifts in the corrosion potential should be observed after addition of the corrosion inhibitor if the geometric blocking effect is stronger than the energy effect (Martinez and Metikos-Hucovic, 2003).

As can be seen from Table 1, no shift in the values of corrosion potential (Ecorr) were observed for the extracts of plants A.G. and C.I. indicating that the geometric blocking effect is stronger for these two plant extracts. On the other hand, in case of rest of the plants the energy effect is stronger, although the blocking effect cannot be ignored as only a slight change was observed in the corrosion potential (Ecorr) values upon addition of the plant extracts. Also, it is clear that the addition of alcoholic extracts of all the plants in aggressive media either shift the corrosion potential (Ecorr) values slightly toward positive side or remained constant but alter both anodic and cathodic Tafel slope (βa and βc) values indicating that the presence of extracts inhibits both cathodic and anodic reactions and the extracts can be classified as mixed corrosion inhibitors (Huilong et al., 2002).

The corrosion behavior of mild steel in 0.5 M HCl in the absence and presence of plant extracts was investigated by EIS at open circuit potential and at after 30 min of immersion.

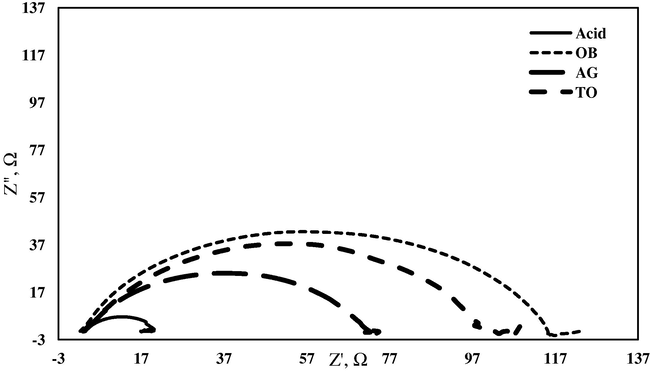

The Nyquist plot in the presence and absence of alcoholic extracts of some selected plants is shown in Fig. 2. It is worth noting that the presence of extracts did not alter the profile of impedance diagrams and it was found to be same in the presence and absence of plant extracts and composed of one semicircle indicating that a charge transfer process at the mild steel is the rate determining step. However, deviation from perfect semicircle indicates some inhomogeneity or roughness of the mild steel surface (Boyanzer et al., 2006). The charge-transfer resistance (Rct) values are calculated from the difference in impedance at lower and higher frequencies. The double layer capacitance (Cdl) was computed using the Eq. (2):

Typical Nyquist plots for mild steel in 0.5 M HCl and in the presence of 0.01 g/100 ml of alcoholic extracts of OB, AG and TO.

Extract

Rs (Ω)

Rct (Ω)

1/Rct (Ω−1)

Cdl (μF)

n

IE (%)

0.5 M HCl

3.26

17.6

0.057

98.0

0.864

–

L.S.

3.68

73.6

0.014

43.2

0.834

76.1

T.O.

2.84

73.6

0.014

32.9

0.849

76.1

O.B.

2.82

112.7

0.009

20.6

0.819

84.4

A.G.

4.22

66.6

0.015

28.8

0.819

73.6

C.I.

2.45

23.6

0.042

70.5

0.833

25.4

A.S.

2.90

62.3

0.016

42.6

0.811

71.8

C.T.

3.10

46.1

0.022

53.9

0.832

61.8

T.A.

2.56

62.0

0.016

54.0

0.813

71.6

It is evident from the data shown in Table 2 that the values of charge transfer resistance (Rct) were increased in the presence of alcoholic extracts of all plants compared with those in acid solution. This phenomenon is associated with decrease in the double layer capacitance (Cdl) values in the presence of plant extracts. The decrease in the Cdl values in the presence of plant extracts could be attributed to the adsorption of the phytochemicals present in plant extracts over the mild steel surface as organic compounds adsorption process on the metal surface is characterized by a decrease in Cdl value (Aramaki et al., 1987). The values of inhibition efficiency (IE %) were calculated by using the Eq. (3):

In order to check the stability of plant extracts in the acidic media, inhibition efficiency (IE %) was measured for some of the plant extracts present in the acidic medium at different time intervals. The inhibition efficiency (IE %) values for plant extract in acidic medium at different time intervals were also studied and are given in Table 3.

Extracts

IE% at 0 h

IE % at 24 h

IE % at 48 h

Tafel

EIS

Tafel

EIS

Tafel

EIS

C.T.

88.0

65.1

85.0

64.8

87.4

66.0

T.A.

83.7

61.3

82.7

66.0

83.4

66.5

A.S.

89.3

71.7

87.8

64.8

86.2

65.1

From Table 3 it is clear that the observed inhibition efficiency (IE %) remained unchanged with time and the plant extracts are unaffected by their presence in the acid solution suggesting that plant extracts are stable in 0.5 M HCl media.

The corrosion of mild steel in HCl solution containing plant extracts can be inhibited due to the adsorption of phytochemicals present in plant extracts through their lone pair of electrons and π-electrons with the d-orbitals on the mild steel surface (De Souza and Spinelli, 2009; Abdel-Gaber et al., 2009; Oguzie, 2008). The polar functions with S, O or N and π-electrons of the organic compounds are usually regarded as the reaction center for the establishment of the adsorption process. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) analysis of plant extracts led to the identification of 26 components from all the studied plants (Table 4). It is interesting to see here that all the identified compounds from plant extracts contained oxygen and/or π-electrons in their molecules. Moreover, from the previous studies on the phytochemical constituents of the plant extracts it was established that the plant extracts used in this study also contain a mixture of organic compounds containing O, N or π-electrons in their molecules (Table 5). Hence, the corrosion inhibition of mild steel through these studied plants may be attributed to the adsorption of the phytochemicals containing O, N or π-electrons in their molecules as these atoms are regarded as centers of adsorption onto the metal surface. However, the highly complex chemical compositions of the plant extracts make it rather difficult to assign the inhibitive effect to a particular compound present in plants extracts. Having confirmed the corrosion inhibition effectiveness of these plants extracts, further detailed investigation for each plant extract through inhibitive assay guided isolation using surface analytical techniques will enable the characterization of the active compounds in the adsorbed layer and assist in identifying the most active phytochemicals. +: Present, −: not present.

Components

Molecular formula

L.S.

T.O.

O.B.

A.G.

C.I.

A.S.

C.T.

T.A.

Palmitic acid

C16H32O2

+

+

+

+

+

−

+

+

Undecanoic acid

C11H22O2

−

−

−

−

+

−

+

−

8,11,14-Eicosatrienoic acid

C20H34O2

−

+

+

−

+

−

+

−

Stearic acid

C18H36O2

−

−

−

−

−

−

+

+

Ergost-5-en-3-ol

C28H48O

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

+

Bisabolol oxide A

C15H26O2

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

+

Stigmast-5-en-3-ol

C29H50O

+

−

−

+

+

+

−

+

Cholestan-3-one-4,4-dimethyl

C20H50O

+

−

−

+

+

−

−

+

25-Homo-24-ketocholesterol

C28H46O2

−

−

−

−

−

+

−

−

E,E-5-Caranol

C10H18O

−

−

+

−

−

+

−

−

δ-Nerolidol

C15H26O

−

−

−

−

−

+

−

−

Flavone-4′-OH, 5-OH, 7-di-O-glucoside

C27H30O15

−

−

−

−

−

+

−

−

Ergost-25-ene-3,6-dione, 5,12-dihydroxy

C28H44O4

−

−

−

−

−

+

−

−

Spiro[androst-5-ene-17,1-cyclobutan] 2′-one, 3-hydroxy

C22H32O2

+

+

−

−

−

+

−

−

Viridiflorol

C15H26O

−

−

−

−

−

+

−

−

Nonanoic acid

C9H18O2

+

−

+

−

−

−

−

−

Oleic acid

C18H34O2

+

+

+

−

−

−

−

−

Neophytadiene

C20H38

+

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

Ergost-25-ene-3,5,6-triol

C28H48O3

+

−

−

−

−

−

−

−

Flovonol-3′,4′,5,7-OH-3-O-araglucoside

C26H30O16

−

−

+

−

−

−

−

−

Coniferol

C10H12O3

−

−

+

−

−

−

−

−

Ethyl undecylate

C13H26O2

−

−

+

−

−

−

−

−

Phytol

C20H40O

−

−

+

−

−

−

−

−

Behenic acid

C22H44O2

−

+

−

−

−

−

−

−

1,2,4,5-Cyclohexanetetraol

C6H12O4

−

+

−

−

−

−

−

−

Isopulegol

C10H18O

−

−

−

+

−

−

−

−

Plants

Phytochemicals

Lycium shawii

No reports concerning the phytochemical isolation are available.

Teucrium olivrianum

Neo-clerodane diterpenoids and their derivatives (Al-Yahya et al., 2002).

Ochradenus baccatus

Flavanoids and their glycosides (Barakat et al., 1991).

Anvillea garcinii

Germacranolides (Abdel-Sattar and McPhail, 2000).

Cassia italica

Coumarins, carotenoids, flavonoids, anthraquinones, sterols and triterpenes (Kazmi et al., 1994).

Artemisia sieberi

Flavanoids, terpenoids and their glycosides (Marco et al., 1993).

Carthemus tinctorius

Unsaturated fatty acids, flavanoids and their glycosides, adenosine, adenine, uridine, thymine, uracil, roseoside, acetylenic and aromatic glycosides (Jiang et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2008).

Tripleurospermum auriculatum

Unsaturated fatty acids and sterols (Al-Wahaibi, 2003).

4 Conclusions

The alcoholic extracts of the eight studied plants, in particular, A. sieberi, T. auriculatum, C. tinctorius, L. shawii, and O. baccatus have showed promising corrosion inhibition properties for mild steel in 0.5 M HCl media. On comparing the percentage inhibition efficiencies of these five plant extracts with those of previously reported percentage inhibition efficiencies of different plant extracts in various acidic media, it was found that these five plants of the present study could serve as effective green corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic media. From the polarization studies it is evident that all the plant extracts act as mixed-type corrosion inhibitors. Further investigations to assess the corrosion morphology and to isolate and confirm the active phytochemicals responsible for the inhibition of mild steel corrosion in acidic media are required.

Acknowledgment

Financial support from National Plan for Science and Technology (NPST), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia for our ongoing project No. 10-ENV1004-02 is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- Corros. Sci.. 2006;48:2765.

- Corros. Sci.. 2009;51:1038.

- Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2008;109:297.

- J. Electroanal. Chem.. 2004;565:321.

- J. Nat. Prod.. 2000;63:1587.

- Anti-Corros. Meth. Mater.. 2007;54:219.

- Identification of essential oil components by Gas chromatography/quadrupole mass spectroscopy. Carol Stream, Illions: Allured Publishing Corporation; 2001.

- Corros. Sci.. 1994;36:79.

- American Society for Testing and Materials, 1978. Annual book of ASTM standard, ASTM, Philadelpia, PA.

- Phytochemistry. 2002;59:409.

- Al-Wahaibi, L.H.N., 2003. M.Sc. Thesis, Chemistry Department, Girls College, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

- Corros. Sci.. 1987;27:487.

- J. Appl. Electrochem.. 2006;36:1163.

- Phytochemistry. 1991;30:3777.

- Surf. Sci.. 2006;252:6212.

- Corros. Sci.. 2002;44:2271.

- Anti-Corros. Meth. Mater.. 2005;52:29.

- Mater. Lett.. 2006;60:2840.

- Portugaliae Electrochim. Acta. 2008;26:257.

- Bull. Electrochem.. 2003;19:23.

- Corros. Sci.. 2009;51:642.

- Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2004;87:138.

- Economic Effects of Metallic Corrosion in the United States, 1978a, NBS Special Publication 511-1, SD Stock No. SN-003-003-01926-7.

- Economic Effects of Metallic Corrosion in the United States, 1978b, Appendix B, NBS Special Publication 511-2, SD Stock No. SN-003-003-01927-5.

- Corros. Sci.. 2000;42:731.

- Corros. Sci.. 2005;47:385.

- Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2005;89:28.

- Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2009;47:1556.

- Bull. Electrochem.. 1997;13:97.

- Anti-Corros. Meth. Mater.. 2002;49:127.

- Zhongguo Zhong Yao Zhi. 2008;33:2911.

- Phytochemistry. 1994;36:761.

- Synth. Met.. 2002;131:99.

- J. Appl. Electrochem.. 2000;30:823.

- Electrochim. Acta. 2003;48:1735.

- Phytochemistry. 1993;34:1061.

- J. App. Electrochem.. 2003;33:1137.

- J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol.. 2002;77:486.

- Corros. Sci.. 2004;46:769.

- Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2006;99:441.

- Corros. Sci.. 2007;49:1527.

- Corros. Sci.. 2008;50:2993.

- Bull. Electrochem.. 2006;22:63.

- Mater. Lett.. 2008;62:113.

- Mater. Corros.. 2009;60:22.

- Prog. Org. Coat.. 1981;9:165.

- J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res.. 2008;10:817.

- Surf. Tech.. 1985;24:391.