Translate this page into:

Cytoprotective effect of selenium polysaccharide from Pleurotus ostreatus against H2O2-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in PC12 cells

⁎Corresponding author. sxnydxwy@163.com (Yu Wang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

One main fraction of Selenium-enriched Pleurotus ostreatus (P. ostreatus) polysaccharide (Se-POP-1) was extracted and purified by DEAE-52 and sephadex G-100. Se-POP-1 was an approximate homogenous polysaccharide with an average molecular weight of 1.62 × 104 Da, and mainly composed of glucose, mannose and galactose, with molar ratio of 5.30:1.55:2.14. The absorption peaks at 941 cm−1 and 1048 cm−1 in FT-IR analysis were ascribed as C-O-Se and Se=O bonds. Pr-treatment of Se-POP-1 (400 μg/mL) increased the cell survival of H2O2-stimulated PC12 cells and inhibited intrinsic apoptosis and oxidative stress in H2O2-stimulated PC12 cells via limiting DNA degradation and decreasing the reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. In addition, up-regulation of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2, down- regulation of pro-apoptotic protein Bax, cleaved caspase 3, and cytochrome c were also observed. Se-POP-1 presented an obvious effect to alleviate oxidative damage and apoptosis in PC12 cells induced by H2O2. Therefore, Se-POP-1 possessed potent antioxidant and biological activities with the ability to prevent oxidation via scavenging ROS and free radicals in cells. It could be developed as organic selenium dietary supplement and functional food.

Keywords

Selenium-enriched polysaccharide

Pleurotus ostreatus

Chemical structure

Antioxidant activity

H2O2

PC12 cell

1 Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are predominantly produced from the respiratory chain of mammalian cellular mitochondria and peroxisomes, as well as from exogenous sources. ROS are essential components of the cells of living organisms in normal conditions and play a dual role in the physiological processes, including phagocytosis, intracellular signalling, cell proliferation, metabolism, apoptosis and muscle contraction (Wang et al., 2016). But when the accumulation of ROS beyonds the defense capacity of living cells, or when the cellular antioxidant system is insufficient, the oxidative stress occurs. As a consequence, the excess accumulation of ROS in cell can cause oxidative damage to cell membranes, lipids, proteins and DNA leading to cell injury or even death of cells. ROS has also been implicated in various diseases, such as atherosclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, neurodegenerative and carcinogenesis (Zhang et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2017). Consequently, oxidative stress from increased ROS and/or insufficient antioxidant defense systems has been widely considered as a major cause of cell damage (Guo et al., 2013; Mao et al., 2014). The antioxidant defense has been demonstrated to be one of the most effective means for protecting the cells from oxidative injury.

The rat pheochromocytoma cell line 12 (PC12) was derived from an adrenal pheochromocytoma and has been widely used as a model for exploring cytoprotective agents (Hu et al., 2017; Chu et al., 2019). Recent studies indicated the oxidative damage initiated mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in various cells such as PC12 cells via ROS production and oxidative stress formation (Maroto and Perez-Polo, 1997; Hwang and Yen, 2008). Among various ROS, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) has been widely used to induce oxidative damage in cell culture models. There are numerous natural compounds that have been succeed in preventing H2O2-induced oxidative injuries in PC12 cells. For instance, polysaccharides are considered as important antioxidants and provide protective effects against ROS-induced oxidative insult and intrinsic apoptosis in PC12 cells (Guo et al., 2019; Sheng et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2016b; Chu et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2018). Additionally, Se was reported to serve as the potential protective roles in reducing mercury, arsenic and cadmium induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells by autophagy/apoptosis-regulation apoptosis inhibition (Hossain et al., 2021; Rahman et al., 2018; Fang et al., 2017). It is also reported that Se contributes to increasing antioxidant activity of polysaccharides in many different cell types (Wang et al., 2012). Therefore, many researchers have focused more on the Se-enriched polysaccharides in recent years.

Pleurotus ostreatus is one of the most popular commercialized edible fungi that has been widely cultivated. It has also been used as traditional foods for a long period time in many Asian countries such as China, Korea and Japan for its abundant biological substances (e.g. polysaccharides, protein and trace elements) as well as low fat. Pleurotus ostreatus can effectively absorb selenium from cultivated medium and transform inorganic selenium to organic forms via binding to protein and polysaccharide. Pleurotus ostreatus polysaccharide (POP) has been found to have antioxidant, immunomodulatory, anti-tumor and antiviral activities (Zhang et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012). Previous studies on the selenium (Se)-containing polysaccharides of P. ostreatus were focused on the chemical structure analysis and antioxidant and anticancer activities. However, there is relatively little known about the protective effects of selenium enriched P. ostreatus polysaccharides at the cellular level. The detailed biomolecular mechanisms of ameliorations of Se contrary to H2O2-toxicity still remains ambiguous and needs further investigations. In this study, we used injury model of PC12 cells induced by H2O2 to explore the protective effects of selenium polysaccahride from P. ostreatus and its mechanism of action.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Samples

The fresh fruiting bodies of P. ostreatus fortified with sodium selenite to the medium were cultivated in Zituan Ecological Agriculture Co., Ltd (Changzhi, Shanxi, China).

2.2 Chemicals

Sodium selenite (Na2SeO3) was purchased from Xiya Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). The standard monosaccharides including D-glucose, D-galactose, D-xylose, D-mannose, L-rhamnose, L-arabinose and trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) were obtained from Sigma Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). DEAE-52 cellulose and Sephadex G-100 were acquired from Solarbio Bioscience & Technology Corporation Limited. (Beijing, China). PC12 cell was obtained from College of Food Science and Engineering of Tianjin University of Science and Technology (Tianjin, China). Antibodies against Bax, Bcl-2, Cytochrome C, cleaved Caspases 3, Nrf2 as well as β-actin were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Annexin V-FITC Apoptosis Detection Kit, Cell cycle detection kit, The Reactive oxygen species (ROS) kit and the other kits used in assays were bought from BioSource International, Inc. (Camarillo, CA, USA). All other chemicals were of the highest purity and commercially grade available.

2.3 Extraction and purification of polysaccharides

The air-dried fruit bodies of P. ostreatus were ground into powder (particle size: 200–300 μm), then the powder was pretreated with 95% ethanol for three times to remove some colored materials, fats and other low molecular compounds. Then the residue was collected with nylon cloth filter. Afterwards, 10 g of pretreated samples were mixed with 300 mL distilled water at 90 ◦C and stirred for 3 h, and the process was repeated for three times. All supernatants were collected and condensed by rotary evaporator. The extracting samples were precipitated with four-fold volume of 95% ethanol and kept overnight at 4◦C. The polysaccharide was obtained after centrifugation at 5000g for 10 min.Thereafter, polysaccharide was deproteinated with Sevag reagent (chloroform: nbutanol = 3:1), followed by exhaustive dialysis with tap water for 48 h and distilled water for 48 h. Finally, the water soluble crude selenium-polysaccharide was obtained by lyophilizing.

The crude polysaccharide was dissolved in distilled water and loaded onto DEAE-52 cellulose column (2.6 × 40 cm). The column was first equilibrated with distilled water, then eluted with a linear gradient NaCl solution (0–0.5 M) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Different fractions (5 mL/tube) were collected according to the total carbohydrate content as quantified by the phenol–sulfuric acid method, the main fractions were obtained, dialyzed and lyophilized. Next, the fractions were further purified on sephadex G-100 column (30 × 2.6 cm) and eluted with ultrapure water at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. The main fraction was obtained and named Se-POP-1.

2.4 Preliminary characterization of Se-POP-1

2.4.1 Chemical component analysis

The total carbohydrate content was determined by the phenol–sulfuric acid method with D-glucose as a standard (Dubois et al., 1956). The protein content was estimated by Coo-massie brilliant blue G-250 method with bovine serum albumin as the standard (Bradford, 1976). Uronic acid content was determinated by the carbazole–sulfuric acid method using glucuronic acid as standard (Bitter and Muir, 1962). Sulfate content was measured according to the gelatin barium chloride method (Kawai et al., 1969). The selenium content in Se-POP-1 was detected by a graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometer (WFX-210, Rayleigh, China). Briefly, the sample was predigested with mixed acid (HNO3: HClO4 = 4:1, v/v) for 2 h until the solution became colorless and clear. After cooling, the solution was diluted with 20% HCl for further determination (Wang et al., 2015).

2.4.2 Molecular weight distribution

Molecular weight (Mw) of Se-POP-1 was determined by High-performance gel-permeation chromatography (HPGPC) with Refractive Index Detector, The TSK-gel G4000 PW (7.8 × 300 mm) column was employed. The Se-POP-1 solution was filtered through 0.45 μm pore membrane, and 20 μL of sample (2 mg/mL) was injected and eluted with ultrapure water at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. Calibration curve was established through T-series Dextran standards (T-10, T-40, T-70, T-500 and T-2000). The molecular weight of Se-POP-1 was calculated according to the standard curve (Zhu et al., 2011).

2.4.3 Fourier transformed infrared spectral analysis

One milligram polysaccharide and 150 mg spectroscopic grade KBr powder were grinded and pressed into 1 mm pellet. Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR, VECTOR-22) spectrum of Se-POP-1 was obtained by FT-IR spectrophotometer with scanning range of 4000–400 cm−1 (Yan et al., 2010).

2.4.4 Monosaccharide composition analysis

Five milligram sample was dissolved with 2 M trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and hydrolyzed at 110℃ for 5 h, then the TFA was removed by washing with methanol. Pyridine and acetic acid anhydride were added to acetylation at 90◦C for 1 h. The acetylated sample was completely dissolved in dichloromethane for further GC (GC2010, Shimadzu, Japan) analysis (Zhang et al., 2016). D-glucose, D-xylose, D-galactose, L-rhamnose, D-mannose and L-arabinose were also derivated as standards.

2.4.5 Scanning electron microscopy analysis

The polysaccharide was placed on a specimen holder and fixed onto a copper stub and then coated with a thin gold layer under reduced pressure. The SEM analysis was performed on a SU1510 scanning electron microscope (SU1510, Hitachi High Technologies, Japan) (Lai and Yang, 2007).

2.5 Cell culture and treatment

PC12 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. The cell was kept at 37 ℃ in an incubator with a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. When the PC12 cells reached 80% confluence, they were treated with 0.25% trypsin in 0.02% EDTA solution. Prior to exposure to H2O2 with concentration of 400 μM for 2 h, cells were pretreated with Se-POP-1 at concentrations of 200 μg/mL and 400 μg/mL for 24 h. Cells without treatment were used as the control, while cells treated with H2O2 alone for 2 h served as the model group.

2.5.1 Cell apoptosis assay

To evaluate the protective effect of Se-POP-1 on H2O2-induced oxidative stress on PC12 cells, cell apoptosis including early apoptosis and late apoptosis was detected using Annexin V-FITC/PI staining. PC12 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 105 / mL. After treatments as above, cells were harvested and were washed with PBS, and then suspended in 500 μL 1 × binding buffer. And the cells were incubated with 5 μL Annexin V-FITC and 5 μL PI for 10 min at room temperature in the dark. Finally, the levels of apoptotic cells were analyzed by flow cytometry (Song et al., 2015).

2.5.2 Cell cycle analysis

Cell cycle distributions were determined by PI staining. PC12 cells were treated as describe above, then cells were harvested, washed with PBS and fixed with ice-cold 70% (v/v) ethanol overnight at 4℃. Then the cell pellets were washed twice and resuspended in PBS buffer. Afterwards, 20 μL of RNase A solution was added and the cells were incubated for 30 min at 37℃. Finally, the cells were incubated with 400 μL of PI at 4℃ for 30 min in the dark. The percentage of apoptotic cells was quantified by sub-G1 DNA content and the distribution of cell cycle was determined by flow cytometer (Zhu et al., 2013).

2.5.3 Cell morphology observation

After the treatment as describe above, PC12 cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, then the fixed cells were stained with DAPI (1.5 μg/mL in PBS) for 15 min and washed with PBS for three times. Cells were examined to assess changes in nuclear morphology and analyzed by a fluorescence microscope (Lee et al., 2005).

2.5.4 Intracellular ROS generation analysis

Intracellular formation of ROS was measured by flow cytometry and the H2O2-sensitive DCFH-DA fluorescence was used as a substrate. The treated cells were collected and adjusted to 2 × 105, and then incubated with 40 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min at 37℃. Afterwards, the cells were washed twice with PBS and monitored by flow cytometry with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 525 nm. For each condition, 10,000 cells were counted. Quadrant analysis was done using WinMDI software (Ding et al., 2016).

2.5.5 GSH-Px activity and GSH level determination

After treatment, PC12 cell lysate was collected, the GSH-Px activity and GSH level were detected with an assessment kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Shi et al., 2014).

2.5.6 Western blotting

After treatments, cells were washed 3 times with cold PBS and the lysate from caspase assay was centrifuged at 14,000g for 15 min. The supernatants were collected and the protein concentration was quantitated by the BCA Protein Assay Kit.

Equal amounts of protein (30 mg) from the supernatant was loaded on to 10% SDS-PAGE apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 100 V for 2 h, and transferred to 0.22 μm PVDF membranes in transfer buffer. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween-20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4℃ with various primary antibodies. After washing with TBST for three times, a second incubation was carried out with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, the membrane was incubated with the enhanced ECL immunoblotting detection kit and exposed with an X-ray film. The protein expression level of each strap was quantitated by the ImageJ-Pro Plus 5.1 software The relative amount of target proteins in each strap was obtained after normalization with the β-actin values (Chu et al., 2019; Fang et al., 2017).

2.6 Statistical analysis

Results were reported as the means ± SD (standard deviation). SPSS version 16.0 software was used for all statistical calculations (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). An ANOVA was used to determine the differences between the sample results. All values with p < 0.05 were considered significantly different.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Chemical contents and monosaccharide compositions

The crude Se-POP was obtained by the series procedures as extraction, sedimentation, deproteinization, dialysis and lyophilization. Two main components were purified by DEAE-52 cellulose column chromatography (Fig. 1A). The elution peak was narrower at the concentration of NaCl of 0.3 mol/L. The fraction was further purified on Sephadex G-100 column and a signal peak was obtained (Fig. 1B). The purified fraction showed higher antioxidant activity compared with other fractions. Therefore, one major polysaccharide fraction, named Se-POP-1 was selected for further research.

The elution curve of Se-POP on the DEAE-52 cellulose column (A) and on the Sephadex G-100 column (B).

The total carbohydrate content, protein content, uronic acid content, sulfate content, and selenium content of Se-POP-1 were 82.74%, 6.81%, 1.89%, 4.32% and 3.69 µg/g, respectively, indicating that it is the Se-containing polysaccharide. The selenium content was much higher than the native P.ostreatus polysaccharide, while the content was similar to those of Se-polysaccharide from Ziyang green tea and Se-enriched Maitake polysaccharide, with organic selenium contents of 2.14 µg/g and 4.50 µg/g, respectively (Wang et al., 2013; Mao et al., 2014). However, the selenium content in the Se-POP-1 was slightly lower than in other selenium modified polysaccharides, such as Catathelasma ventricosum Se-polysaccharides (41.77 µg/g) and Coprinus comatuson Se-polysaccharides (15.21 µg/g) (Liu et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2009).

Monosaccharide composition was detected by GC and the results were recorded in Fig. 2. Six standard monosaccharides of L-rhamnose, L-arabinose, D-xylose, D-mannose, D-glucose and D-galactose were used as standard monosaccharides. As shown in Fig. 2A, all identified peaks were separated rapidly within 20 min. The sample was identified by matching their retention time with those of monosaccharide standards under the same analytical conditions. As shown in Fig. 2B, the monosaccharide composition showed that Se-POP-1 was mainly consisted of glucose, mannose and galactose with molar ratio of 5.30:1.55:2.14.

GC chromatography of standard monosaccharide (A) and Se-POP-1 (B), Peaks: 1, rhamnose; 2, arabinose; 3, xylose; 4, mannose; 5, glucose; 6, galactose; 7, internal standard.

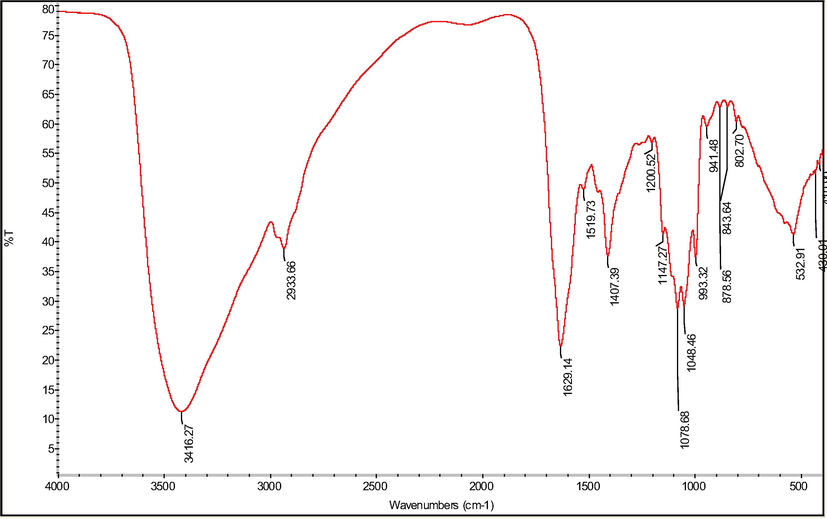

3.2 FTIR spectroscopy analysis

FT-IR spectroscopy is usually used for identification of characteristic organic groups in polysaccharides. IR absorbance of the polysaccharide was shown in Fig. 3. The band at 3339 cm−1 was due to the stretching of the hydroxyl groups. Whereas the spectrum of xylan with β(1 → 4) backbone was dominated by an intense ring and (COH) side group band at 1048 cm−1. The peak at 2933 cm−1 reveals the presence of the C-H vibration. The characteristic absorbance around 1606 cm−1 was attributed to N-H sretching. All absorption bands were typical absorption peaks of polysaccharides. Two stretching peaks at 1408 cm−1 and 1161 cm−1 in the IR spectra suggested the presence of C-O bonds. The absorptions at 1078.36 cm−1 was designated to a pyranose form of sugars. These common peaks suggest that introduction of selenium does not affect the main structure of the polysaccharide, which was in accordance with other result (Yu et al., 2009). The binding of Se on polysaccharides was generally recognized as C-O-Se and Se=O form with the absorption peaks at 941 cm−1 and 1048 cm−1 (Wei et al., 2015; Xiao et al., 2017)

FT-IR spectra of Se-POP-1.

3.3 The molecular weight properties

The molecular weight distribution of Se-POP-1 and T-series dextran standard was shown in Fig. 4, and the standard curve equation was y = − 0.3863x + 8.7216 (R2 = 0.9938, y = lgMw, x = Rt). It could be seen that the HPGPC chromatogram of Se-POP-1 showed a relative single peak, which indicated that the Se-POP-1 was an approximate homogeneous polysaccharide. The average molecular weight of Se-POP-1 was determined to be 1.62 × 104 Da in reference to universal calibration curve and the retention time.

HPLC of Se-POP-1 (A) and standard curve (B).

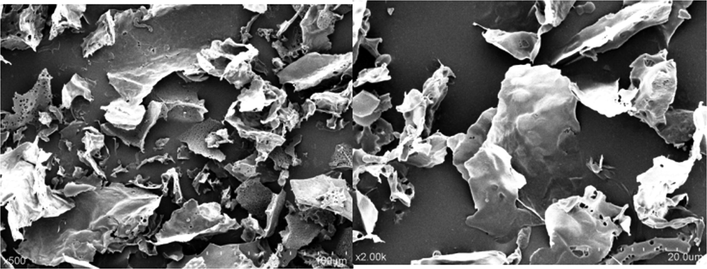

3.4 Morphological analysis

The scanning electron microscopy can be used as a commonly useful tool to analyze and predict the physical properties and surface morphology of polysaccharides. As shown in Fig. 5, the SEM images showed the aggregation structure of Se-POP-1, specifically. Its surface was big lamellar structured and with small irregular pores, which was similar to the Se-enriched tea polysaccharides (Wang et al., 2015). The regularity of structure was crumble, intertwined and rather rough. Furthermore, it can be speculated that the Se-POP-1 was composed of relative homogeneous matrix. It was reported that the surface morphology and structure of polysaccharides might be changed by selenylation modification, and thus affected the functional and biological properties of polysaccharides.

SEM images of Se-POP-1.

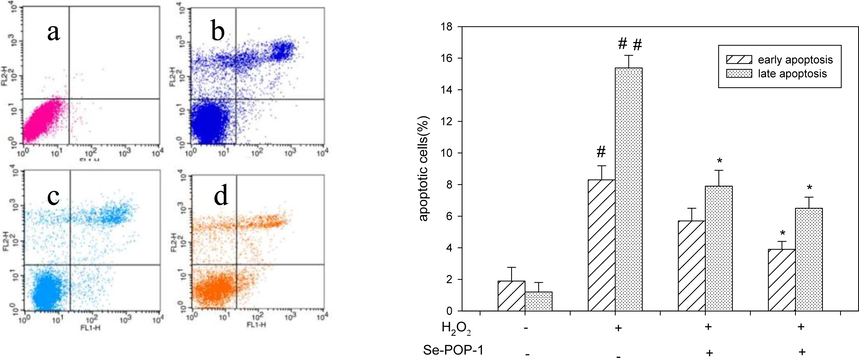

3.5 Effect of Se-POP-1 on H2O2-induced apoptosis in PC-12 cells

Compelling evidence has supported that oxidative stress-induced apoptosis, also known as programmed cell death, plays a critical role in neuronal and hepatic injury. The cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI, and the apoptosis was assayed through flow cytometry. The results were shown in Fig. 6. The cells in the lower left quadrant were double negative and recognized as viable cells, and the early and late apoptotic cells were appeared in the lower right quadrant and the upper right quadrant, respectively. The AV+/PI + cell population in upper left quadrant has been identified as advanced apoptotic or necrotic. In early and late apoptotic cells, the percentage of apoptotic cells in the H2O2-treated group was significantly increased to 8.31% and 15.40% compared with the control group (p < 0.05, p < 0.01). However, the apoptosis was decreased in a concentration-dependent manner in Se-POP-1 treated groups. The apoptosis decreased to 5.74% and 7.93% (p < 0.05) after being pretreated with Se-POP-1 at 200 μg/mL, and the percentage was further notable decreased to 3.92% and 6.55% at the concentration of 400 μg/mL (p < 0.05). It was observed that apoptosis of H2O2-induced PC12 cells could be significantly alleviated after pretreated with the Se-POP-1, which obviously suggested that the Se-POP-1 could effectively mediate oxidative damage and significantly protect PC12 cells against H2O2-induced apoptosis. The mechanisms of Se-POP-1 for ameliorative effects on H2O2 induced apoptosis in PC12 cells were as follows: it was proposed that selenium possibly existed in the form of selenyl group (-SeH) or seleno-acid ester in the selenium polysaccharides, the new two groups could activate the hydrogen atom of the anomeric carbon and have the capacity of hydrogen atom-donating, in turn they could be able to convert more free radicals to stable products (Liu et al., 2013). Additionally, the two new groups may regulate the cellular antioxidant enzymes, such as glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) (Mou et al., 2003). GSH-Px is one of major cellar antioxidant enzyme and plays an important role in protecting cells from oxidative damage. Our results demonstrated that pretreatment of H2O2-induced PC12 cells with Se-POP-1 increased the level of GSH-Px and GSH (Fig. 9). GSH-Px can catalyze the reduction of harmful peroxides and radicals, and protect the cells from oxidative damage by converting reduced glutathione (GSH) to its oxidized form (GSSG).

Cell apoptosis for different treatment of PC12 cells.(a) control; (b) model (H2O2 400 μΜ);(c) H2O2 (400 μΜ) + Se-POP-1 (200 μg/ mL); (d) H2O2 (400 μΜ) + Se-POP-1 (400 μg/ mL).

3.6 Effects of Se-POP-1 on the DNA damage of H2O2-induced PC12 cells

Severe oxidative stress usually contributed to DNA damage which can be monitored by Flow cytometry with PI-staining, and the sub-G1 peak was traditional considered as one of the important apoptosis characteristics. As shown in Fig. 7 (A), Compared with the control group (1.46%), a distinct rise in the sub-G1 peak (23.82%) was discovered in groups exposured to H2O2. The progression of cell cycle arrested at G0/G1 phase was to prevent damaged DNA from being duplicated, but a dose-dependent decrease of sub-G1 peak were observed when incubating the H2O2-induced PC12 cells with different concentrations of Se-POP-1. The percentage of sub-G1 peak decreased to 14.35% and 7.27% when pretreated with 200 μg/mL and 400 μg/mL of Se-POP-1, respectively. The results demonstrated that H2O2 caused G0/G1 cell cycle arrest leading cells to death (Ding et al., 2016) and the ratio of G0/G1 phase could be significantly decreased by pretreating with Se-POP-1. It was confirmed that hydrogen peroxide inhibited cell proliferation and caused DNA fragmentation in cultured PC12 cells. However, pretreatment with Se-POP-1 could promote DNA synthesis and cell proliferation and provide protection against DNA damage induced by H2O2. The mechanism was probably due to treatment of Se-POP-1 induced increases of GSH and GSH-Px in PC12 cells (Fig. 9). Increased GSH and GSH-Px may modulate DNA-repair activity (Chatterjee, 2013). Similar result was also reported that Se and Se induced GSH-Px provided protection on cell membrane integrity and against DNA damage induced by iHg and UV (Hossain et al., 2021; Baliga et al., 2007).

Cell cycle (A) and Morphological changes for different treatment of PC12 cells (B). (a) control; (b)model (H2O2 400 μΜ);(c) H2O2 (400 μΜ) + Se-POP-1 (200 μg/ mL); (d) H2O2 (400 μΜ) + Se-POP-1 (400 μg/ mL).

3.7 Effects of Se-POP-1 on the morphology of H2O2-induced PC12 cells

In order to further understanding the protective effects of Se-POP-1 on the DNA and nuclear structure in PC12 cells, morphological changes were examined by monitoring the H2O2-induced morphological features of cultured PC12 cells in the absence or presence of Se-POP-1 under Laser confocal microscope. As presented in Fig. 7 (B), treatment of cultured PC12 cells with 400 μM H2O2 alone led to a considerable proportion apoptosis, which representing a lot of small bright blue dots and chromatin condensation or nuclear fragmentation. Meanwhile, cells pretreatment with Se-POP-1 (200 μg/mL and 400 μg/mL) significantly decreased the apoptotic cells with nuclear condensation and fragmentation, and most of cell nuclei were close to their normal shape and size. Taken together, pretreatment of cells with Se-POP-1 could inhibit the nucleic morphological changes and alleviate the oxidative damage in PC12 cells from the oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide.

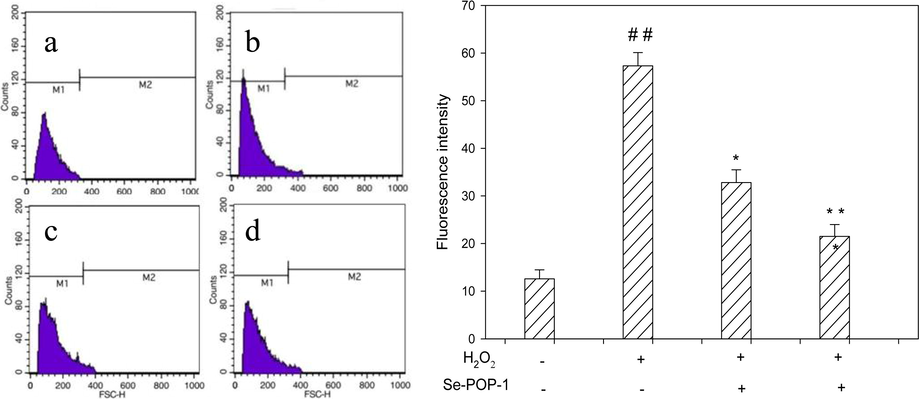

3.8 Effect of Se-POP-1 on H2O2-induced ROS production in PC-12 cells

It is commonly used PC12 cells as a oxidative stress model in test of possible cytoprotection of the antioxidative compounds, and especially in the assessment of their intracellular ROS scavenging ability. The intracellular ROS level and the intracellular ROS-scavenging activity of Se-POP-1 in oxidized PC12 cells induced by H2O2 were evaluated, and the results were shown in Fig. 8. The group exposured to H2O2 alone had the higher intracellular ROS level compared to control group (p < 0.01), indicating that H2O2 triggered oxidative stress in PC12 cells through the accumulation of intracellular ROS. As expected, the groups that had been pretreated with Se-POP-1 significantly decreased ROS levels in H2O2-stimulated cells in a dose-dependent manner (p < 0.05). Group treated with 400 μg/mL of Se-POP-1 significantly suppressed H2O2-induced intracellular ROS production (p < 0.01). Therefore, It suggested that excessive ROS generation acts a critical role in H2O2-induced oxidative stress and pr-treatment of Se-POP-1 exhibited excellent ROS-scavenging capacities through its antioxidant properties. Our results demonstrated that treatment of H2O2 induced increase of ROS (Fig. 8), increased ROS damages cellular membrane lipids and cellular DNA (Fig. 7A), excess organelle damages lead to inability of maintaining cellular function, thus induces apoptosis and cell death (Fig. 6, Fig. 7B). We found that pretreatment with Se-POP-1 could reduce the intracellular ROS level induced by H2O2. It was probably due to increases of GSH-Px and GSH, which were considered as the highly abundant cellular scavengers of ROS.

ROS production for different treatment of PC12 cells. (a) control; (b)model (H2O2 400 μΜ);(c) H2O2 (400 μΜ) + Se-POP-1 (200 μg/ mL) ;(d) H2O2 (400 μΜ) + Se-POP-1 (400 μg/ mL). ##p < 0.01 vs normal group; *p < 0.05 vs H2O2 group and **p < 0.01 vs H2O2 group.

GSH-Px activity and GSH level for different treatment of PC12 cells. ##p < 0.01 vs normal group; *p < 0.05 vs H2O2 group and **p < 0.01 vs H2O2 group.

3.9 Effect of Se-POP-1 on H2O2-induced GSH-Px and GSH in PC-12 cells

GSH-Px plays a central role in protecting the cells from oxidative damage induced by H2O2 with high concentration, and the restored GSH-Px activity can utilize the GSH to catalyze the reduction of peroxides (H2O2 or lipid peroxides) in the cells and protect the cells from oxidative stress consequently. The activity of GSH-Px and level of GSH were determined in different treatment of PC 12 cells, and the results were shown as in Fig. 9. The activity of GSH-Px and level of GSH decreased significantly under H2O2-induced oxidative stress in PC12 cells (p < 0.01), whereas pretreatment of Se-POP-1 (200 μg/mL and 400 μg/mL) enhanced GSH-Px activity and GSH level dramatically in H2O2-treated cells (p < 0.05, p < 0.01). This result may be explained by the fact that Selenium is a cofactor of glutathione peroxidase (GSH-Px) and Se induced increase of GSH-Px and GSH in PC12 cells pretreated with Se-POP-1.

3.10 Effects of Se-POP-1 on the expression of apoptotic proteins in H2O2 induced PC12 cells

Bcl-2 proteins, a large family of apoptosis-regulating proteins, can be classified into two groups according to the structure and function: anti-apoptotic like Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL and pro-apoptotic including Bax and Bak (Ramkumar et al., 2012). Bcl-2 proteins play a crucial role in the mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis pathway and have been identified as major regulators in blocking cytochrome c efflux into the outer mitochondrial membrane (Reed, 2001). Bax proteins induce apoptosis by disintegrating the outer mitochondrial membrane and causing the release of cytochrome c (Dan and Yamori, 2011). Bcl-2 inhibits apoptosis while Bax promotes apoptosis. The balance between these two proteins is commonly used to determine the cell survival or death. An increase in Bcl-2 level antagonizes the promotion effect of Bax to apoptosis and limits the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, which could suppress the activation of caspase cascade and apoptosis (Czabotar et al., 2014). Caspase-3, a frequently activated cysteine protease and can be activated by ROS, also connected with the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway and has been identified as important regulators in the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (Mazumder et al., 2008). Nrf 2 is a transcription factor that regulates the expression of a series of phase II detoxifying enzyme and the expression of antioxidant enzymes (such as SOD, HO-1, CAT, GSH, GST, etc.), activation of Nrf2 could diminish ROS production and improve the ability of anti-oxidative stress (Hossain et al., 2021).

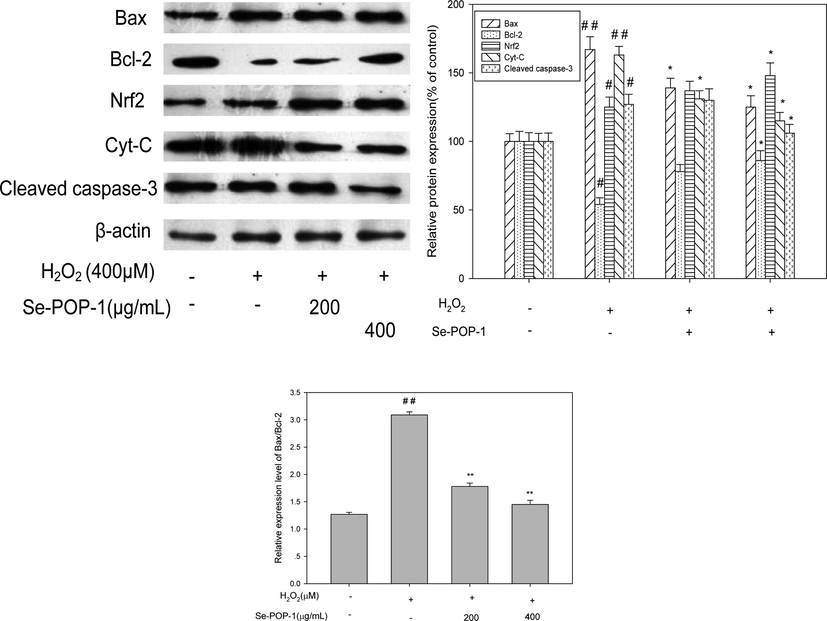

To investigate the protective effect of Se-POP-1 on H2O2-induced mitochondrial depolarization in PC12 cells, the changes in the expressions of apoptosis-related proteins including Bcl-2, Bax, Nrf2 and cleaved caspase-3 in PC12 cells after H2O2 exposure were determined. As described in Fig. 10, an increased expression of pro-apoptotic protein Bax (p < 0.01) and decreased expression of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 (p < 0.05) were observed in PC12 cells under H2O2 stress lonely in comparison with that of control group, meanwhile, the ratio of bax/bcl-2 was 3.09. However, the observation was reversed in a dose-dependent manner by pre-incubation with Se-POP-1. Se-POP-1(400 μg/mL) treatment resulted in an increased level of Bcl-2 expression and decreased level of Bax expression (p < 0.05), leading to an decrease in the pro-apoptotic/anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 ratio, especially, the ratio of bax/bcl-2 was decreased to 1.45. The results were in accordance with the previous related studies (Deng et al., 2015; Shan et al., 2015). The expression of cleaved caspase-3 was elevated obviously in PC12 cells treated with H2O2 alone as compared with control group (p < 0.05). However, pretreating with Se-POP-1 with concentration of 400 μg/mL could dramatically converse the increase of cleaved caspase-3 expression compared with H2O2-treated alone (p < 0.05). Previous data has illustrated that H2O2 exposure could result in cytotoxicity and the over expression of caspase-3, while various polysaccharides could alleviate the oxidative stress induced cell apoptosis via blocking the caspase-3 (Sheng et al., 2017; Spencer et al., 2001; Martín et al., 2010). Similarly, the cytosolic cytochrome c levels were significantly increased in PC12 cells incubated with H2O2 alone compared to the control (p < 0.01), which suggests the disruption of mitochondrial outer membrane and origination of intrinsic apoptosis. However, pretreatment with Se-POP-1 significantly attenuated the cytochrome c release from the mitochondria as compared with H2O2-treated group (p < 0.05). The transcription factor Nrf2 is an essential mediator in the coordinated regulation of some cytoprotective genes. Western blot results showed that Nrf2 expression was improved notably under H2O2 stress in comparison with that of control group (p < 0.05). Interestingly, this increase was further enhanced to defense oxidative stress by pre-treating with Se-POP-1(400 μg/mL) compared to the H2O2 treated group (p < 0.05). The results suggested that H2O2 caused down-regulating protein expressions of Bcl-2 and Nrf2; whereas resulted in up-regulating of Bax, cleaved caspase 3 and cytochrome c expressions synergistically, which demonstrated oxidative stress and intrinsic apoptosis were occurred. Se-POP-1 treatment could inhibit apoptosis by up-regulating the pro-survival proteins (Bcl-2 and Nrf2) and decreasing the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2, as well as down-regulating the expression of proapoptotic proteins (Bax, cytochrome c and cleaved caspase-3). Similarly, it was reported that Se induced the down-regulation of cytochrome c in cadmium induced cytotoxic on PC12 cells (Hossain et al., 2018), Se induced down-regulation of cleaved caspase 3 and cytochrome c in iHg-induced toxicity PC12 cells (Hossain et al., 2021), and Se induced inhibition of apoptosis by down-regulation of caspase 3 (Ren et al., 2016).

Protein expression in PC12 cells for different treatment. #p < 0.05 vs normal group; ##p < 0.01 vs normal group; *p < 0.05 vs H2O2 group and **p < 0.01 vs H2O2 group.

4 Conclusion

The selenium-enriched P. ostreatus polysaccharide (Se-POP-1) with the selenium content of 3.69 µg/g was obtained by hot water extraction and DEAE-52 and G-100 purification. It was mainly composed of glucose, mannose and galactose with the molar ratio of 5.30:1.55:2.14, and the average molecular weight was approximately 1.62 × 104 Da. Se-POP-1 exhibited excellent inhibition against severe oxidative damage in H2O2-induced PC12 cells by improving cell membrane integrity, limiting DNA injury, inhibiting ROS generation, decreasing the ratio of Bax/Bcl-2 and diminishing pro-apoptotic cytochrome c and cleaved caspase 3, and finally arresting apoptosis. These protection of Se-POP-1 was estimated to be resulted from the antioxidant properties of Se-POP-1. Se-POP-1 have potent antioxidant properties and could be explored as functional food ingredient or component of medicines with organic selenium supplements.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ling Ma: Data curation, Writing – original draft. Jing Liu: Data curation, Writing – original draft. Anjun Liu: Investigation, Validation. Yu Wang: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgment

This research was co-financed by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2017YFD0400206), Shanxi Province key R&D Plan (201812005) and Zituan Ecological Agriculture Co., Ltd (130014008) (Changzhi City, Shanxi province, China). Mr Zhigang Zhang and Ms Yongxia Zhang are gratefully acknowledged for their special help in developing P. ostreatus.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Selenium and gpx-1 overexpression protect mammalian cells against UV-induced DNA damage. Biol. Trace Elem. Res.. 2007;115:227-241.

- [Google Scholar]

- A modified uronic acid carbazole reaction. Anal. Biochem.. 1962;4:330-334.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein binding. Anal. Biochem.. 1976;72:248-254.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Reduced glutathione: a radioprotector or a modulator of DNArepair activity? Nutrients. 2013;5:525-542.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Control of apoptosis by the BCL-2 protein family: implications for physiology and therapy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol.. 2014;15(1):49-63.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Apios americana Medik flowers polysaccharide (AFP-2) attenuates H2O2 induced neurotoxicity in PC12 cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2019;123:1115-1124.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Repression of cyclin B1 expression after treatment with adriamycin: but not cisplatin in human lung cancer A549 cells. Biochem. Biophy. Res. Commun.. 2011;280:861-867.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of selenium on lead-induced alterations in Aβ production and Bcl-2 family proteins. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol.. 2015;39(1):221-228.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and anti-aging activities of the polysaccharide TLH-3 from Tricholoma lobayense. Int. J. Biol. Macormol.. 2016;85:133-140.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protection mechanism of Se-containing protein hydrolysates from Se-enriched rice on Pb2+-induced apoptosis in PC12 and RAW264.7 cells. Food Chem.. 2017;219:391-398.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and immunomodulatory activity of selenium exopolysaccharide produced by Lactococcus lactissubsp.lactis. Food Chem.. 2013;138:84-89.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A polysaccharide isolated from Sphallerocarpus gracilis protects PC12cells against hydrogen peroxide-induced injury. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2019;129:1133-1139.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Neuroprotective effects of the citrus flavanones against H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells. J. Agric. Food. Chem.. 2008;56:859-864.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Neuroprotective effects of six components from Flammulina velutipes on H2O2 -induced oxidative damage in PC12 cells. J. Funct. Foods. 2017;37:586-593.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory effects of selenium on cadmium-induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells via regulating oxidative stress and apoptosis. Food Chem. Toxicol.Toxicol.. 2018;114:180-189.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Selenium modulates inorganic mercury induced cytotoxicity and intrinsic apoptosis in PC12 cells. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.. 2021;207:111262

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai, Y., Seno, N., Anno, K., 1969. A modified method for chondrosulfatase assay. Anal. Chem. 32, 314–321. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90091-8.

- Induction apoptosis of luteolin in human hepatoma HepG2 cells involving mitochondria translocation of Bax/Bak and activation of JNK. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.. 2005;203:124-131.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rheological properties of the hot-water extracted polysaccharides in Ling-Zhi (Ganoderma lucidum) Food Hydrocolloids. 2007;21:739-746.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antidiabetic activity of mycelia selenium-polysaccharide from Catathelasma ventricosumin STZ-induced diabetic mice. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2013;62:285-291.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maroto, R., Perez-Polo, J.R., 1997. BCL-2-related protein expression in apoptosis: oxidative stress versus serum deprivation in PC12 cells. J. Neurochem. 69, 514–523. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69020514.x.

- Caspase-3 activation is a critical determinant of genotoxic stress-induced apoptosis. Methods Mol. Biol.. 2008;1219(414):1.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cocoa flavonoids up-regulate antioxidant enzyme activity via the ERK1/2 pathway to protect against oxidative stress-induced apoptosis in HepG2 cells. J. Nutr. Biochem.. 2010;21(3):196-205.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Extraction, preliminary characterization and antioxidant activity of Se-enriched Maitake polysaccharide. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2014;101(213–219):213-219.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A κ-carrageenan derived oligosaccharide prepared by enzymatic degradation containing anti-tumor activity. J. Appl. Phycol.. 2003;15:297-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Apoptosis-regulating proteins as targets for drug discovery. Trends Mol. Med.. 2001;7:314-319.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Selenium inhibits homocysteine-induced endothelial dysfunction and apoptosis via activation of akt. Cell. Physiol. Biochem.. 2016;38:871-882.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oxidative stress-mediated cytotoxicity and apoptosis induction by TiO 2 nanofibers in HeLa cells. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm.. 2012;81(2):324-333.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ameliorative effects of selenium on arsenic-induced cytotoxicity in PC12 cells via modulating autophagy/apoptosis. Chemosphere. 2018;196:453-466.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Epicatechin and its in vivo metabolite, 3'-O-methyl epicatechin, protect human fibroblasts from oxidative-stress-induced cell death involving caspase-3 activation. Biochem. J. 2001;354(3):493-500.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective effect of a polysaccharide isolated from a cultivated Cordyceps mycelia on hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative damage in PC12 cells. Phytother. Res.. 2011;25:675-680.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Involvement of caspases and their upstream regulators in myocardial apoptosis in a rat model of selenium deficiency-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. J. Trace Elem. Med Biol.. 2015;31:85-91.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peptides derived from eggshell membrane improve antioxidant enzyme activity and glutathione synthesis against oxidative damage in Caco-2 cells. J. Functional Foods. 2014;11:571-580.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of phosphorylation on antioxidant activities of pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo, Lady godiva) polysaccharide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2015;81:41-48.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A selenium polysaccharide from Platycodon grandiflorum rescues PC12 cell. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2017;104:393-399.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isolation, antioxidant property and protective effect on PC12 cell of the main anthocyanin in fruit of Lycium ruthenicum Murray. J. Funct. Foods. 2017;30(97–107):97-107.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization, antioxidant activity and neuroprotective effects of selenium polysaccharide from Radix hedysari. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2015;125:161-168.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of selenium-containing polysaccharides and evaluation of antioxidant activity in vitro. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2012;51:987-991.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tumoricidal effects of a selenium (Se)-polysaccharide from Ziyang green tea on human osteosarcoma U-2 OS cells. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2013;98:1186-1190.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Extraction, characterization and antioxidant activities of Se-enriched tea polysaccharides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2015;77:76-84.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Intracellular ROS scavenging and antioxidant enzyme regulating capacities of corn gluten meal-derived antioxidant peptides in HepG2 cells. Food Res. Int.. 2016;90:33-41.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A polysaccharide isolated from Cynomorium songaricum Rupr. Protects PC12 cells against H2O2-induced injury. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2016;87:222-228.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structure characterization of one polysaccharide from Lepidium meyenii Walp., and its antioxidant activity and protective effect against H2O2-induced injury RAW264.7 cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2018;118:816-833.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Construction of a Cordyceps sinensis exopolysaccharide-conjugated selenium nanoparticles and enhancement of their antioxidant activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2017;99:483-491.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective effect of selenium-polysaccharides from the mycelia of Coprinus comatuson alloxan-induced oxidative stress in mice. Food Chem.. 2009;117:42-47.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural elucidation of an exopolysaccharide from mycelial fermentation of a Tolypocladium sp. Fungus isolated from wild Cordyceps sinensis. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2010;79:125-130.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gastroprotective activities of a polysaccharide from the fruiting bodies of Pleurotus ostreatus in rats. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2012;50:1224-1228.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural analysis and anti-tumor activity comparison of polysaccharides from Astragalus. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2011;85:895-902.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization and in vitro antioxidant activities of polysaccharides from Pleurotus ostreatus. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2012;51:259-265.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective effects of wheat germ protein isolate hydrolysates (WGPIH) against hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in PC12 cells. Food Res. Int.. 2013;53:297-303.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and hepatoprotective activities of intracellular polysaccharide from Pleurotus eryngii SI-04. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2016;91:568-577.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.Z., Tong, X.H., Sui, X.N., Wang, Z.J., Qi, B.K., Li, Y., et al., 2018. Antioxidant activity and protective effects of Alcalase-hydrolyzed soybean hydrolysate in human intestinal epithelial Caco-2 cells. Food Res. Int. 111, 256–264 (CNKI:SUN:DDTB.0.2019-S1-009).

Further reading

- Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem.. 2002;28:350-356.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]