Design and optimization of lipids extraction process based on supercritical

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Extraction of oil with supercritical

Keywords

Supercritical

Carbon dioxide

Microalga

Biodiesel

Dunaliella Tertiolecta

1 Introduction

Scientists predict that the world will face a crisis of shortage of oil, gas and coal resources in the not-too-distant future (Andreo-Martínez et al., 2020; Tan et al., 2020). Extensive studies have been conducted today on sustainable and renewable fuels such as microalga-derived oils (Halim et al., 2012). Biodiesel is the product of a transesterification reaction between lipids and alcohol, and its required fatty acids can be obtained from a wide range of sources such as food waste, animal fats, vegetable oils, cooking oil wastes, algae and other sources (Qadeer et al., 2021).

Based on stoichiometric ratios, one mole of triglyceride or three moles of alcohol reacts, producing three moles of ester and one mole of glycerol (Koyande et al., 2019). Methanol is the most widely used alcohol because of its low cost, but other alcohols can also be used. for example ethanol, isopropanol and, ethanol. Although the use of these alcohols can improve fuel properties, they will be costly on an industrial scale and not feasible. Biodiesel can be produced from a variety of raw materials, including edible oils (soy, palm, sunflower, coconut) (Nguyen et al., 2020). But, the non-edible oils (Jatropha, Camellia, rice bran, Pongamia, Telotia) are preferred. Therefore, the supply of raw materials is one of the most important challenges in biodiesel production, which accounts for 85% of the cost of biodiesel production (Kadir et al., 2021).

Among the various sources for biodiesel production; microalga is the best option because, unlike agricultural and animal resources, they are more efficient, have a less direct effect on the human food cycle, and can be produced in large quantities in a small space (Tan et al., 2018). By providing light, nutrients,

- Schematic of the photosynthesis cycle of microalga.

Dunaliella Tertiolecta is a green and marine microalga. This microalga has two protozoan parts and has been widely used in ecological, industrial and agricultural studies (Iyer, 2016). In the first stage of its reproduction, this microalga requires super-saline and marine habitats, but the results of studies showed that this microalga is able to grow in a wide range of salinity (Faried et al., 2017).

Today, the production of biodiesel using alkaline homogenized catalysts is more commercializable than other methods. This reaction takes place by the addition of a nucleus of the oxide anion to the carbonyl (Leone et al., 2019). The catalysts used are sodium, potassium methoxide and hydroxide. In the alkaline catalyst process, the raw materials must be water-free to prevent hydrolysis of volatile fatty acids (Keddar et al., 2020). Volatile fatty acids are not converted to esters but to soap (Saleem et al., 2018).

In the transesterification method and acidic esterification, the transesterification can be performed in the presence of strong acid catalysts such as sulfuric acid (Liu et al., 2017; Rangabhashiyam and Selvaraju, 2015). The use of this method to produce biodiesel from frying oils and palm oil waste has been reported. Acid catalysts are slower than alkaline catalysts during the acid transesterification process. Due to the low reaction speed, it requires high temperatures and high pressure (Di Caprio et al., 2020). During acidic esterification, water is formed which causes the hydrolysis of triglycerides in small amounts (Tabernero et al., 2012). Most acidic catalysts are highly corrosive and cause contamination and turbidity of biodiesel (Vasistha et al., 2021).

One method of extracting biodiesel from microalgae is the microwave method. Reports have shown that this method is effective but requires a lot of energy (Chang et al., 2020). The biological cell breakdown method is another method of extracting biodiesel from algae that is able to increase biodiesel production (Goh et al., 2019). Nowadays, the extraction method by supercritical

Various shocks can affect the production of biomass and dry microalga and change the amount of oil extracted from the algae. Also, different shock conditions can affect the composition and amount of fatty acids in algae, and as a result, this quality of biofuels is effective. In this study, the effect of changes in culture conditions (different shocks in the microalga breeding stage) was studied quantitatively and qualitatively in biofuel extraction by

2 Experiment

2.1 Material

A sample of Dunaliella Tertiolecta was purchased from the microalga pilot plant facility of arian gostar research company (TAG BIOTEK CO), Tehran, Iran. BBM Medium 50X (Bold's Basal Medium + soil extract + vitamins) (50X), NaCl, Hcl, and NaOH was purchased from the Sigma-Aldrich. Double distillation water was used in all experiments.

2.2 Cultivation of microalga

Microalga were cultured in clear polyethylene terephthalate flasks with a volume of

| Treatments | Instructions for creating shock |

|---|---|

| 1 | Creating severe alkaline conditions (pH 11) |

| 2 | Creating severe salinity conditions by increasing salt (1 M NaCl) |

| 3 | Creating nutrient deficiency conditions (Substrate reduction) |

| 4 | pH 11 + 1 M NaCl |

| 5 | pH 11 + Substrate reduction |

| 6 | 1 M NaCl + Substrate reduction |

| 7 | 1 M NaCl + Substrate reduction + pH 11 |

| 8 | No shock (control sample) |

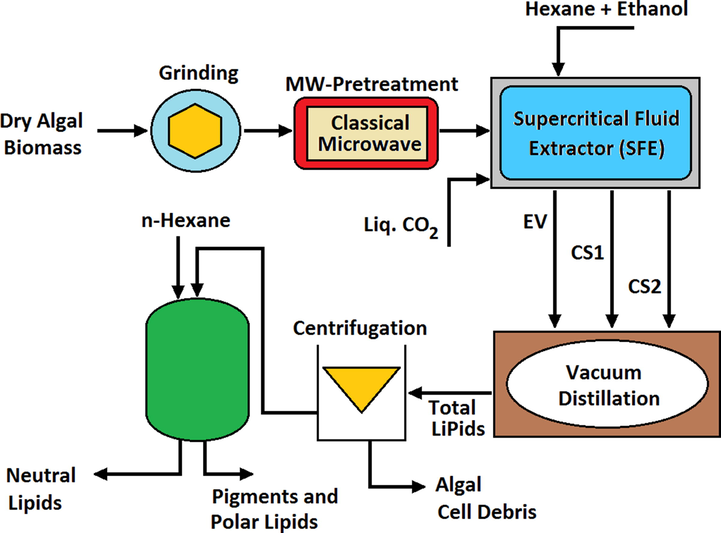

2.3 Extraction with supercritical carbon dioxide

In this method, extraction was performed with the help of liquid carbon dioxide on dry algae, which extracts all the fat of the microalga cell (McKennedy et al., 2016). In this method, 30 g of microalga under temperature conditions of 40-80 °C, pressure of 200–370 bar, mixture of hexane: ethanol solvents (1:1), duration 60 min, carbon dioxide flow rate of 200–100

- The process of extracting biodiesel fuel from microalga using supercritical

According to Paolo Leone et al. (Leone et al., 2019) reports, in terms of purity, the lower the pressure, the higher the purity, because the highest lipid purity was found at 75 °C and 100 bar with a

2.4 Measurement of cell growth

Cell density was determined by measuring the optimal density at a wavelength of 750 nm. The optimal density was checked daily and the number of cells was counted daily. The biomass productivity (

The specific growth rate (

Division time (

2.5 Chlorophyll a, b and total carotene measurements

96% methanol solvent will be used for extraction. For this purpose, a certain amount of culture medium was taken and after separating the algae from the water, 50

The adsorption of chlorophyll a (

2.6 Approximate composition

2.6.1 Lipid and ash content analysis

Soxhlet method was used to measure the amount of total fat and burning the weighed samples in an electric oven at 550 °C for 6

2.6.2 Protein content measurement

To measure the protein content, 5

2.6.3 Total carbohydrate content measurement

The prepared samples were centrifuged at 5000

2.6.4 Fatty acid profiles

200

2.7 Measuring of biodiesel quality

The quality of biodiesel extracted from Dunaliella Tertiolecta oil was determined by evaluating the degree of unsaturation (DU) (Tobar and Núñez, 2018), saponification value (SV) (Keddar et al., 2020), cetane number (CN) (Islam et al., 2017) and, iodine value (IV) (Islam et al., 2017). These values were calculated by following equations:

2.8 Statistical analysis

All measurements were repeated three times and the error of values was considered in the report. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSSSPSS Statistics V.17.01 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). The P-value less than 0.05 was considered as significant.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Growth factors in Dunaliella Tertiolecta microalga

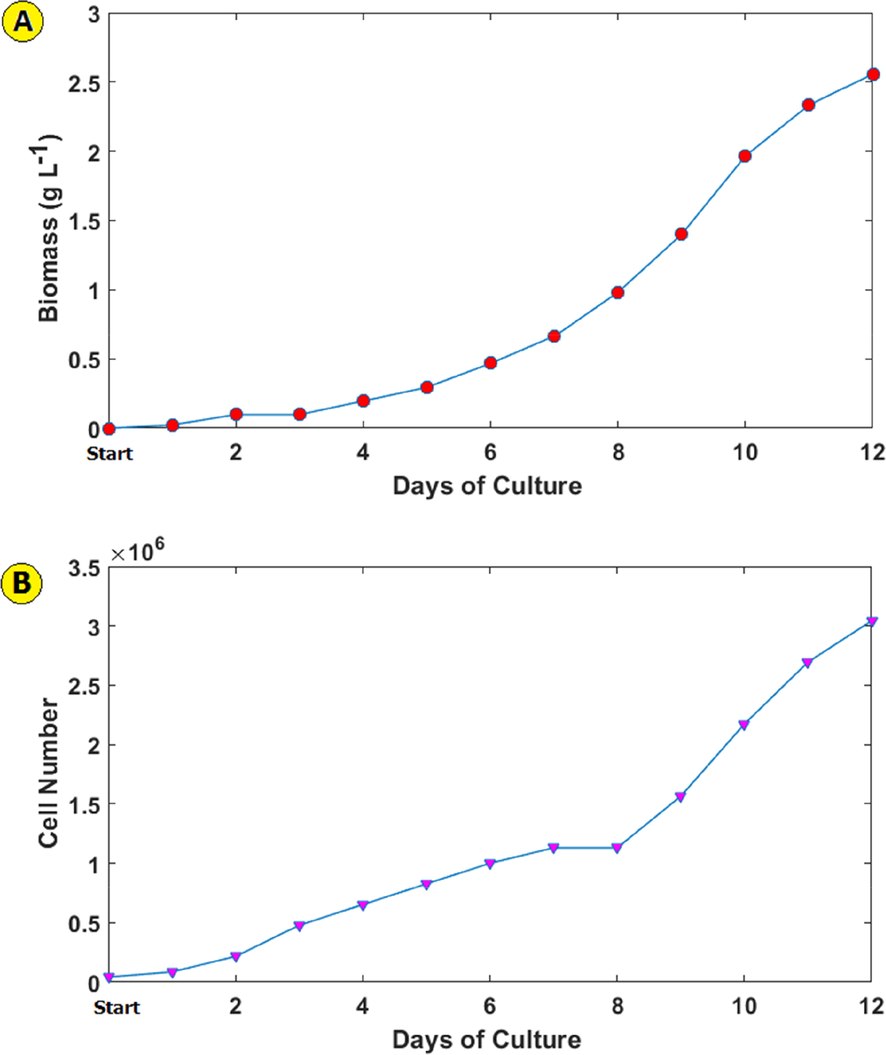

The Dunaliella Tertiolecta microalga biomass production and cell number during 12 days was shown in Fig. 3 a and b. The properties of Dunaliella Tertiolecta microalga growth were as follows: SGR = 0.17

-

Dunaliella Tertiolecta microalga biomass produced (a), cell number (b) and, pH change (c) during 12 days of culture.

-

Dunaliella Tertiolecta microalga biomass produced (a), cell number (b) and, pH change (c) during 12 days of culture.

- Overview of fatty acids of Dunaliella Tertiolecta microalga.

3.2 Approximate composition of Dunaliella Tertiolecta microalga

The results obtained for the microalga Dunaliella teriolecta are given in Table 2. According to the results, the amount of lipid in the dark period 7 treatment was the highest (54.83

| Treatments | Lipid (%) | Ash (%) | Protein (%) | Carbohydrate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dark Time | 23.18 ± 0.44d | 9.00 ± 0.10b | 17.02 ± 0.18ab | 50.24 ± 0.47bc |

| Light Time | 13.73 ± 0.44ab | 8.08 ± 0.49b | 17.07 ± 0.22ab | 60.41 ± 0.38 cd | |

| 2 | Dark Time | 18.05 ± 0.61c | 4.78 ± 0.71a | 16.21 ± 0.209ab | 60.0 ± 2.21 cd |

| Light Time | 17.95 ± 0.56c | 5.23 ± 1.19a | 16.71 ± 0.23ab | 59.64 ± 1.72c | |

| 3 | Dark Time | 20.08 ± 0.72d | 9.24 ± 0.68b | 14.07 ± 2.50a | 56.5 ± 1.30c |

| Light Time | 12.84 ± 0.41ab | 9.60 ± 0.44b | 20.08 ± 0.86b | 57.19 ± 0.72c | |

| 4 | Dark Time | 22.50 ± 0.94d | 7.68 ± 0.96b | 12.02 ± 1.63a | 57.03 ± 1.43c |

| Light Time | 33.89 ± 0.84f | 6.88 ± 0.25ab | 17.39 ± 1.54ab | 41.38 ± 0.02b | |

| 5 | Dark Time | 27.40 ± 1.18e | 5.54 ± 0.20a | 17.66 ± 0.45ab | 49.16 ± 1.57b |

| Light Time | 10.93 ± 0.97a | 4.16 ± 0.85a | 19.16 ± 1.95b | 65.32 ± 3.52e | |

| 6 | Dark Time | 27.53 ± 1.52e | 7.62 ± 0.79b | 14.30 ± 0.09a | 50.27 ± 0.85bc |

| Light Time | 11.63 ± 0.44a | 7.68 ± 0.94b | 21.75 ± 1.90bc | 58.72 ± 2.88c | |

| 7 | Dark Time | 54.83 ± 1.02 g | 5.04 ± 0.96a | 13.16 ± 1.40a | 26.01 ± 1.30a |

| Light Time | 10.21 ± 0.09a | 5.14 ± 0.63a | 19.11 ± 0.54b | 65.45 ± 1.04e | |

| 8 | Dark Time | 28.88 ± 0.16e | 6.75 ± 0.91ab | 13.70 ± 0.77a | 50.27 ± 0.14bc |

| Light Time | 11.20 ± 0.25a | 7.81 ± 0.66b | 17.25 ± 0.68ab | 63.38 ± 1.15d |

Non-identical letters in each column indicate significance between treatments (P < 0.05).

The amount of protein in the results obtained in the light period of treatment 6 (21.75

3.3 Measurement of chlorophyll a, b and total carotene

The results for chlorophyll a, b and total carotene of Dunaliella teriolecta are shown in Table 3. Based on the results, it was determined that the amount of chlorophyll a had the highest value during the light period of treatments 1 (28.18

| Treatments | Chlorophyll a

|

Chlorophyll b

|

Total Carotene

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dark Time | 4.68 ± 0.28b | 3.76 ± 0.1.52a | 322.44 ± 31.10a |

| Light Time | 28.18 ± 0.22e | 16.71 ± 0.07c | 797.27 ± 30.81c | |

| 2 | Dark Time | 7.05 ± 0.02b | 3.93 ± 0.00a | 1238.59 ± 70.00f |

| Light Time | 28.78 ± 0.36e | 16.40 ± 0.12c | 833.23 ± 21.88d | |

| 3 | Dark Time | 2.14 ± 0.16a | 2.47 ± 0.143a | 852.95 ± 13.00d |

| Light Time | 29.74 ± 0.19e | 16.87 ± 0.21c | 906.22 ± 16.30d | |

| 4 | Dark Time | 4.01 ± 1.46b | 3.21 ± 0.07a | 1892.19 ± 31.27 g |

| Light Time | 22.87 ± 0.21c | 14.22 ± 0.02b | 498.87 ± 16.72b | |

| 5 | Dark Time | 5.57 ± 0.01b | 3.36 ± 0.01a | 1111.62 ± 14.61e |

| Light Time | 23.11 ± 0.84c | 13.68 ± 0.45b | 439.48 ± 106.83b | |

| 6 | Dark Time | 2.45 ± 0.29a | 2.53 ± 0.17a | 879.52 ± 21.04d |

| Light Time | 24.19 ± 0.26 cd | 14.67 ± 0.47b | 482.83 ± 32.04b | |

| 7 | Dark Time | 2.32 ± 0.15a | 2.31 ± 0.21a | 872.45 ± 5.17d |

| Light Time | 22.40 ± 0.38c | 13.32 ± 0.47b | 441.24 ± 28.61b | |

| 8 | Dark Time | 2.54 ± 0.01a | 2.52 ± 0.04a | 900.79 ± 44.35d |

| Light Time | 24.87 ± 1.99 cd | 14.11 ± 0.62b | 439.20 ± 84.25b |

Non-identical letters in each column indicate significance between treatments (P < 0.05).

Based on the results obtained for total carotene, it was found that the highest amount of carotene is present in the dark period of treatment 4 (1892.19

3.4 Profiles of fatty acids

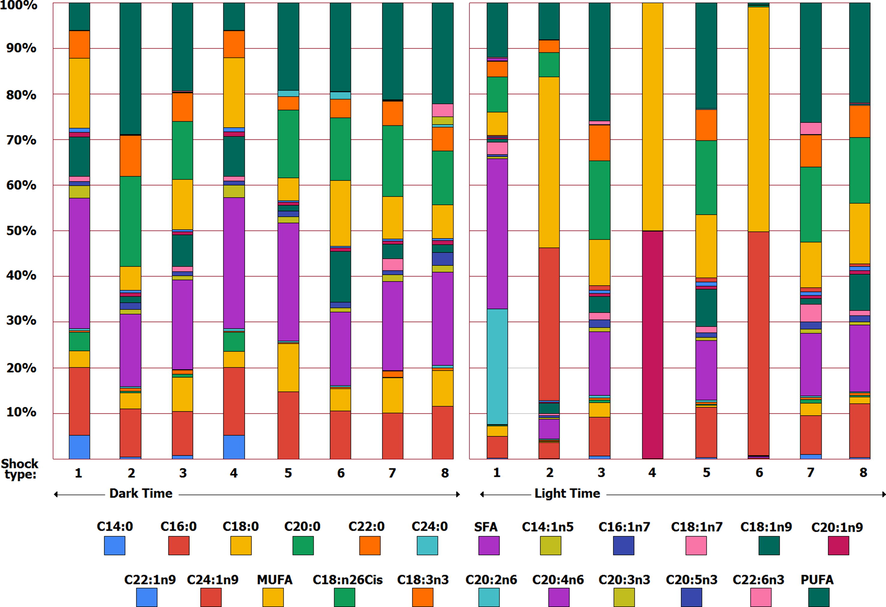

The profile results of Dunaliella teriolecta microalga fatty acids are given in Table 4. Based on the results, it was found that the amount of myristic acid (C14) in the dark period was higher than the light period and the highest and lowest values in the dark period (15.57

| Fatty acid profiles | Time | Treatments

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| C14 | Dark Time | 9.74 ± 0.52c | 8.72 ± 0.52c | ND | 15.57 ± 0.12d | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.00a | 1.09 ± 0.02b |

| Light Time | 0.50 ± 0.12a | 3.59 ± 1.05c | 3.53 ± 0.01c | 0.51 ± 0.12a | 0.39 ± 0.11a | 0.79 ± 0.07a | 1.46 ± 0.13b | 0.87 ± 0.04a | |

| C16:0 | Dark Time | 20.94 ± 1.06b | 17.89 ± 1.05a | 17.36 ± 0.82a | 21.70 ± 0.69b | 25.95 ± 0.14c | 20.53 ± 0.09b | 21.17 ± 0.69b | 24.58 ± 0.12c |

| Light Time | 24.19 ± 0.74c | 10.31 ± 2.12a | 17.28 ± 0.72b | 23.96 ± 0.73c | 15.88 ± 0.83b | 23.82 ± 0.38c | 17.54 ± 0.53b | 21.29 ± 0.20c | |

| C18:0 | Dark Time | 12.91 ± 0.53bc | 6.70 ± 0.53a | 11.91 ± 0.51bc | 4.40 ± 0.28a | 18.58 ± 0.10c | 8.06 ± 0.04b | 16.76 ± 0.55c | 11.12 ± 0.09bc |

| Light Time | 7.09 ± 0.41a | 8.65 ± 0.29a | 22.12 ± 0.14d | 24.28 ± 0.12d | 10.67 ± 0.01ab | 14.12 ± 0.53bc | 13.98 ± 0.21b | 29.28 ± 0.09f | |

| C20:0 | Dark Time | 7.73 ± 0.41c | 7.71 ± 0.41c | ND | 0.45 ± 0.09ab | ND | ND | 0.01 ± 0.00c | 0.87 ± 0.19b |

| Light Time | 0.40 ± 0.09a | ND | 0.42 ± 0.07a | 0.40 ± 0.09a | 0.31 ± 0.09a | 0.63 ± 0.05ab | 1.16 ± 0.10a | 0.99 ± 0.03ab | |

| C22:0 | Dark Time | 0.61 ± 0.20a | 0.55 ± 0.25a | 0.78 ± 0.07a | 0.88 ± 0.03a | 3.56 ± 0.24b | 2.43 ± 0.05b | 0.73 ± 0.02b | 0.62 ± 0.00a |

| Light Time | 0.40 ± 0.11a | 0.26 ± 0.00a | 0.91 ± 0.02a | 1.09 ± 0.04b | 3.76 ± 0.25c | 2.12 ± 0.08c | 1.33 ± 0.00b | 0.90 ± 0.14a | |

| C24:0 | Dark Time | 0.80 ± 0.03a | 1.11 ± 0.00ab | 0.81 ± 0.00a | 0.37 ± 0.05a | 1.17 ± 0.05b | 0.67 ± 0.14a | 0.24 ± 0.00a | 0.27 ± 0.000a |

| Light Time | 7.65 ± 0.05c | 0.19 ± 0.00a | 0.24 ± 0.00a | 0.54 ± 0.16a | 0.71 ± 0.04a | 0.22 ± 0.00a | 0.45 ± 0.02a | 2.93 ± 0.05b | |

Non-identical letters in each column indicate significance between treatments (P < 0.05).

Stearic acid (C18:0) showed the highest value during the light period in treatment 8 (29.28

The profile of monounsaturated fatty acids of Dunaliella teriolecta is given in Table 5. Based on the results, Myristoleic acid (C14:1n5) in the dark period had the highest value in treatments 1 (5.13

| Fatty acid profiles | Time | Treatments

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| C14:1n5 | Dark Time | 5.13 ± 0.40c | 5.14 ± 0.41c | 2.17 ± 0.07ab | 1.27 ± 0.34a | 2.51 ± 0.01ab | 1.44 ± 0.00a | 2.36 ± 0.07ab | 1.18 ± 0.00a |

| Light Time | 11.18 ± 0.02c | 5.61 ± 0.00b | 5.99 ± 0.01b | 1.41 ± 0.04a | 1.01 ± 0.02a | 1.02 ± 0.01a | 1.26 ± 0.0.02a | 1.29 ± 0.11a | |

| C16:1n7 | Dark Time | 1.81 ± 0.10a | 1.81 ± 0.10a | 4.40 ± 0.17c | 1.95 ± 0.06a | 2.17 ± 0.00ab | 2.04 ± 0.00ab | 1.66 ± 0.02a | 1.42 ± 0.00a |

| Light Time | 1.48 ± 0.04a | 5.62 ± 0.00c | 1.86 ± 0.05a | 1.86 ± 0.07a | 1.49 ± 0.04a | 1.66 ± 0.02a | 1.39 ± 0.03a | 2.28 ± 0.02b | |

| C18:1n9 | Dark Time | 8.07 ± 0.54d | 1.97 ± 0.11a | 1.67 ± 0.04a | 1.92 ± 0.06a | 1.67 ± 0.02a | 5.70 ± 0.19c | 1.68 ± 0.00a | 2.02 ± 0.02ab |

| Light Time | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 3.89 ± 0.13b | ND | 1.66 ± 0.00a | |

| C18:1n7 | Dark Time | 16.30 ± 0.33c | 16.28 ± 0.33c | 12.54 ± 0.90b | 11.56 ± 0.42ab | 9.11 ± 0.40a | 11.81 ± 0.53ab | 8.31 ± 0.19a | 15.20 ± 0.07c |

| Light Time | 11.94 ± 0.06b | 5.64 ± 0.00a | 12.54 ± 0.09b | 11.66 ± 0.05b | 22.22 ± 0.00d | 18.64 ± 0.08c | 24.79 ± 0.17d | 4.72 ± 0.06a | |

| C20:1n9 | Dark Time | 1.84 ± 0.40b | 1.85 ± 0.41b | 1.34 ± 0.15b | 0.91 ± 0.15a | 1.21 ± 0.01ab | 1.20 ± 0.02ab | 1.04 ± 0.03ab | 1.14 ± 0.13ab |

| Light Time | 1.19 ± 0.00ab | 4.48 ± 0.04c | 1.15 ± 0.04ab | ND | ND | 0.85 ± 0.00a | ND | ND | |

| C22:1n9 | Dark Time | 1.72 ± 0.02b | 1.75 ± 0.00b | 1.44 ± 0.05b | 1.15 ± 0.28b | 1.35 ± 0.06b | 1.44 ± 0.05b | 1.19 ± 0.19b | 0.80 ± 0.00a |

| Light Time | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| C24:1n9 | Dark Time | 0.69 ± 0.00a | 1.16 ± 0.033ab | 0.76 ± 0.00a | 1.35 ± 0.01b | 1.29 ± 0.09ab | 3.47 ± 0.05b | 1.40 ± 0.01b | 1.36 ± 0.16b |

| Light Time | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

Non-identical letters in each column indicate significance between treatments (P < 0.05).

Palmitoleic acid (C16: 1n7) showed the highest value in treatment 3 (4.40

Oleic acid had the highest value during the dark period in treatment 1 (8.07

Paullinic acid (C20:1n9) had the highest value during the dark period in treatments 1 (1.84

The profile results of Dunaliella tertiolecta polyunsaturated fatty acids are given in Table 6. According to the results, the amount of linoleic acid (C18: 2n6) during the dark period had the highest value in treatment 2 (3.60

| Fatty acid profiles | Time | Treatments

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| C18:2n6 | Dark Time | ND | 3.60 ± 2.23c | 0.21 ± 0.03a | ND | ND | 1.15 ± 1.14b | 2.39 ± 5.27bc | ND |

| Light Time | 0.66 ± 0.66a | 0.69 ± 0.68a | 2.47 ± 1.12c | 1.60 ± 1.59b | ND | ND | ND | 2.86 ± 2.15c | |

| C18:3n3 | Dark Time | ND | ND | 27.27 ± 0.80b | 24.78 ± 1.16b | 26.26 ± 0.13b | 22.90 ± 0.10b | 13.42 ± 0.97a | 23.70 ± 0.14b |

| Light Time | 22.92 ± 1.07a | 21.85 ± 0.08a | 20.86 ± 0.79a | 21.34 ± 1.00a | 27.30 ± 1.11b | 22.37 ± 0.55a | 25.16 ± 0.91b | 20.94 ± 0.36a | |

| C20:2n6 | Dark Time | 11.09 ± 0.93c | 11.07 ± 0.93c | 14.51 ± 0.36 cd | 11.20 ± 0.52c | 5.12 ±.02b | 16.95 ± 0.03d | 1.29 ± 0.33a | 14.13 ± 0.07 cd |

| Light Time | 10.28 ± 0.48b | 0.85 ± 0.04a | 10.35 ± 0.39b | 10.93 ± 0.51b | 15.89 ± 0.47d | 9.35 ± 0.23b | 10.67 ± 0.39bc | 8.50 ± 0.16b | |

| C20:3n3 | Dark Time | ND | 0.14 ± 0.03b | ND | 0.06 ± 0.00a | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Light Time | ND | 1.73 ± 0.08c | ND | 0.09 ± 0.00a | ND | 0.18 ± 0.00ab | ND | ND | |

| C20:3n5 | Dark Time | ND | ND | 2.55 ± 0.11c | ND | ND | ND | 0.18 ± 0.00b | 0.08 ± 0.03a |

| Light Time | ND | ND | 0.04 ± 0.00a | ND | ND | ND | 0.08 ± 0.00a | ND | |

Non-identical letters in each column indicate significance between treatments (P < 0.05).

Linolenic acid (C18: 3n3) had the highest value during the dark period in treatments 3 (27.27

Eicosadienoic acid (C20: 2n6) had the highest and lowest values in treatment 6 (16.95

Eicosatrienoic acid (C20: 3n3) had the highest amount in treatment 2 (0.14

Finally, Eicosapentanoic acid (EPA) (C20: 3n5) was not observed in treatments 1, 2, 4, 5 and 6 of the dark shock period. The highest EPA was observed in treatment 3 (2.55

3.5 Quality of fat and biofuels produced

The results obtained on the quality characteristics of fats and biofuels extracted from the microalga Dunaliella tertiolecta are given in Table 7. According to the results regarding the number of sapnification value, no significant difference was observed between different treatments during dark shock (P < 0.05), but slightly treatment 5 (31.25

| Time | Treatments

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||

| Saponification value | Dark Time | 30.95 ± 0.62a | 31.04 ± 0.35b | 31.18 ± 2.01b | 31.11 ± 1.02b | 31.25 ± 1.06b | 31.20 ± 0.35b | 31.23 ± 0.14b | 31.13 ± 1.02b |

| Light Time | 31.28 ± 0.28b | 31.09 ± 1.02b | 31.95 ± 0.85b | 31.16 ± 2.30b | 31.15 ± 0.61b | 31.15 ± 0.04b | 31.03 ± 0.25b | 30.95 ± 1.06a | |

| Iodine value | Dark Time | 123.83 ± 1.20a | 124.18 ± 12.32b | 124.71 ± 11.05b | 124.46 ± 11.08b | 125.00 ± 14.35c | 124.79 ± 9.58b | 124.94 ± 10.35b | 124.54 ± 9.62b |

| Light Time | 124.90 ± 2.15b | 124.39 ± 21.32b | 124.65 ± 10.14b | 124.65 ± 13.00b | 124.59 ± 9.68b | 124.63 ± 10.25b | 124.14 ± 10.20b | 123.82 ± 11.24a | |

| Cetane number | Dark Time | 2509.40 ± 36.54d | 1701.52 ± 23.65a | 1786.26 ± 34.05a | 1865.86 ± 26.51b | 1925.50 ± 30.14c | 1731.63 ± 22.02a | 1969.03 ± 24.15c | 1779.26 ± 24.65a |

| Light Time | 1701.52 ± 26.51a | 1952.88 ± 26.34c | 1831.26 ± 12.65b | 2137.92 ± 24.68 cd | 1771.58 ± 16.85a | 1746.60 ± 30.01a | 1719.28 ± 36.52a | 2713.52 ± 46.25d | |

| Degree of unsaturation | Dark Time | 57.74 ± 1.62a | 97.28 ± 6.21d | 113.40 ± 2.63e | 92.19 ± 3.14c | 82.07 ± 2.65c | 109.10 ± 2.65e | 78.26 ± 3.17b | 99.94 ± 3.52d |

| Light Time | 93.51 ± 2.62d | 71.59 ± 2.15a | 88.98 ± 1.65bc | 82.85 ± 3.12b | 111.10 ± 3.14f | 89.86 ± 3.51bc | 99.26 ± 2.58e | 74.55 ± 3.51a | |

Non-identical letters in each column indicate significance between treatments (P < 0.05).

Cetane number had the highest value during dark shock in treatment 5 (2509.40

Degree of unsaturation was highest during dark shock in treatment 3 (113.40

3.6 Effect of pressure and temperature on extracted oil by

According to Table 8, the amount of fatty acids extracted from Dunaliella tertiolecta microalga using supercritical

| Fatty Acid (w/w %) | Control | Optimal treatment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 bar 40 °C |

285 bar 40 °C |

370 bar 40 °C |

200 bar 80 °C |

285 bar 80 °C |

370 bar 80 °C |

200 bar 40 °C |

285 bar 40 °C |

370 bar 40 °C |

200 bar 80 °C |

285 bar 80 °C |

370 bar 80 °C |

|

| C12:0 Lauric acid |

1.56 | 1.70 | 2.17 | 0.93 | 1.21 | 1.38 | 3.15 | 3.29 | 3.76 | 2.52 | 2.81 | 2.98 |

| C14:0 Myristic acid |

3.32 | 3.42 | 3.59 | 2.23 | 2.27 | 2.60 | 4.92 | 5.01 | 5.18 | 3.82 | 3.86 | 4.20 |

| C16:0 Palmitic acid |

26.99 | 27.39 | 28.51 | 25.12 | 26.01 | 26.51 | 28.59 | 28.99 | 30.10 | 26.71 | 27.60 | 28.11 |

| C18:0 Stearic acid |

28.11 | 29.24 | 30.73 | 24.83 | 25.37 | 27.32 | 29.70 | 30.84 | 32.32 | 26.42 | 26.97 | 28.91 |

| C20:0 Arachidic acid |

1.00 | 1.27 | 1.60 | 0.14 | 0.37 | 0.45 | 2.59 | 2.86 | 3.19 | 1.74 | 1.97 | 2.04 |

| C16:1n7 Palmitoleic acid |

0.88 | 1.20 | 1.49 | 0.37 | 0.63 | 1.18 | 2.47 | 2.79 | 3.09 | 1.97 | 2.22 | 2.77 |

| C18:1n9Oleic acid (Trance) |

1.30 | 1.61 | 2.02 | 0.68 | 0.75 | 1.13 | 2.90 | 3.21 | 3.61 | 2.28 | 2.35 | 2.72 |

| C18:2n6Linoleic acid (LA) |

0.22 | 0.45 | 0.61 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 1.82 | 2.04 | 2.20 | 1.69 | 1.74 | 1.77 |

| C20:5n3 Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) |

2.28 | 2.44 | 2.66 | 1.70 | 1.81 | 1.90 | 3.87 | 4.04 | 4.25 | 3.30 | 3.40 | 3.50 |

| C22:6n3Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) |

0.46 | 0.55 | 0.85 | 0.12 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 2.05 | 2.15 | 2.44 | 1.72 | 1.79 | 1.85 |

| Microalgal species | P (bar) | T (°C) |

|

Polar modifier; quantity of polar modifier | Results | Final total lipid yield (

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spirulina platensis | 316 | 40 | 0.71

|

Ethanol; 9.64, 11, 13, 15, 16.36 ml | Total lipid yield increased with P. Optimum condition was found at 400 bar, 60 min, and 13.7 ml ethanol. | 8.6 |

| Spirulina maxima | 250 | 50 | – | Ethanol; 10 mol% of

|

At constant T, total lipid yield increased with P.At constant P, total lipid yield decreased with T.At constant T and P, polar modifier addition significantly increased total lipid yield. Optimum condition was found at 350 bar, 60 °C with ethanol addition (10 mol%). |

3.1 |

| Hypnea charoides | 310 | 50 | 1

|

– | At constant T, total lipid yield increased with P.At low P (241 bar), total lipid yield decreased with T.At medium to high P (310 and 379 bar), total lipid yield increased with T. Optimum condition was found at 379 bar and 50 °C. |

6.7 |

| Chlorella vulgaris | 350 | 55 | 0.4

|

– | At constant T, total lipid yield increased with P.At low P (200 bar), total lipid yield decreased with T.At high P (350 bar), total lipid yield increased with T. Optimum condition was found at 350 bar and 55 °C. |

13 |

4 Conclusion

Based on the results obtained on growth indices, it was found that with increasing the amount of SGR and

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Andreo-Martínez, P., Ortiz-Martínez, V.M., García-Martínez, N., de los Ríos, A.P., Hernández-Fernández, F.J., Quesada-Medina, J., 2020. Production of biodiesel under supercritical conditions: State of the art and bibliometric analysis. Appl. Energy 264, 114753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.114753.

- Supercritical fluid extraction of bioactive lipids from the microalga Nannochloropsis sp. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol.. 2005;107:381-386.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Environmental Technology & Innovation Biosorption, an efficient method for removing heavy metals from industrial effluents : A Review. Environ. Technol. Innov.. 2020;17:100503

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In situ catalyst-free biodiesel production from partially wet microalgae treated with mixed methanol and castor oil containing pressurized CO2. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2020;157:104702

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sequential extraction of lutein and β-carotene from wet microalgal biomass. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol.. 2020;95:3024-3033.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biodiesel production from microalgae: Processes, technologies and recent advancements. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2017;79:893-913.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bioremediation of textile wastewater and successive biodiesel production using microalgae. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2018;82:3107-3126.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sustainability of direct biodiesel synthesis from microalgae biomass: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2019;107:59-74.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Integrated biodiesel and biogas production from microalgae: Towards a sustainable closed loop through nutrient recycling. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2018;82:1137-1148.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Extraction of oil from microalgae for biodiesel production: A review. Biotechnol. Adv.. 2012;30:709-732.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Microalgae biodiesel: Current status and future needs for engine performance and emissions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2017;79:1160-1170.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The issue of reducing or removing phospholipids from total lipids of a microalgae and an oleaginous fungus for preparing biodiesel. Biofuels. 2016;7:55-72.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Simultaneous harvesting and cell disruption of microalgae using ozone bubbles: optimization and characterization study for biodiesel production. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng.. 2021;15:1257-1268.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Efficient extraction of hydrophilic and lipophilic antioxidants from microalgae with supramolecular solvents. Sep. Purif. Technol.. 2020;251:117327

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of protein extraction from Chlorella Vulgaris via novel sugaring-out assisted liquid biphasic electric flotation system. Eng. Life Sci.. 2019;19:968-977.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leone, G.P., Balducchi, R., Mehariya, S., Martino, M., Larocca, V., Sanzo, G. Di, Iovine, A., Casella, P., Marino, T., Karatza, D., Chianese, S., Musmarra, D., Molino, A., 2019. Selective extraction of ω-3 fatty acids from nannochloropsis sp. using supercritical CO2 Extraction. Molecules 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24132406.

- Liu, W. ping, Yin, X. fei, 2017. Recovery of copper from copper slag using a microbial fuel cell and characterization of its electrogenesis. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 24, 621–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12613-017-1444-z.

- A comprehensive review on harvesting of microalgae for biodiesel - Key challenges and future directions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2018;91:1103-1120.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Supercritical carbon dioxide treatment of the microalgae Nannochloropsis oculata for the production of fatty acid methyl esters. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2016;116:264-270.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Modern developmental aspects in the field of economical harvesting and biodiesel production from microalgae biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2021;135:110209

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spectrophotometric determination of insuline by ternary complex formation with o-carboxyphenylfluorone-copper(II) complex. Bunseki Kagaku. 2007;56:781-784.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- High biodiesel yield from wet microalgae paste via in-situ transesterification: Effect of reaction parameters towards the selectivity of fatty acid esters. Fuel. 2020;272:117718

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Martínez, V.M., Andreo-Martínez, P., García-Martínez, N., Pérez de los Ríos, A., Hernández-Fernández, F.J., Quesada-Medina, J., 2019. Approach to biodiesel production from microalgae under supercritical conditions by the PRISMA method. Fuel Process. Technol. 191, 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2019.03.031.

- Review of biodiesel synthesis technologies, current trends, yield influencing factors and economical analysis of supercritical process. J. Clean. Prod.. 2021;309:127388

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy of unmodified and chemically modified Swietenia mahagoni shells for the removal of hexavalent chromium from simulated wastewater. J. Mol. Liq.. 2015;209:487-497.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biological hydrogen production via dark fermentation by using a side-stream dynamic membrane bioreactor: Effect of substrate concentration. Chem. Eng. J.. 2018;349:719-727.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Supercritical carbon dioxide extraction of algal lipids for the biodiesel production. Procedia Eng.. 2012;42:1755-1761.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Life cycle assessment of biodiesel from estuarine microalgae. Energy Convers. Manage.. 2020;X 8:100065

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating the industrial potential of biodiesel from a microalgae heterotrophic culture: Scale-up and economics. Biochem. Eng. J.. 2012;63:104-115.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A review on microalgae cultivation and harvesting, and their biomass extraction processing using ionic liquids. Bioengineered. 2020;11:116-129.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cultivation of microalgae for biodiesel production: A review on upstream and downstream processing. Chinese J. Chem. Eng.. 2018;26:17-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Supercritical transesterification of microalgae triglycerides for biodiesel production: Effect of alcohol type and co-solvent. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2018;137:50-56.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Current advances in microalgae harvesting and lipid extraction processes for improved biodiesel production: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.. 2021;137:110498

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]