Translate this page into:

Economical, environmental friendly synthesis, characterization for the production of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) nanoparticles with enhanced CO2 adsorption

⁎Corresponding author. hafiz@petroleum.utm.my (Mohd Hafiz Dzarfan Othman)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Zeolitic imidazole framework 8 (ZIF-8) nanoparticles were successfully synthesized in an aqueous solution at the ambient condition with a relatively low molar ratio of zinc salt and an organic ligand, Zn+2/Hmim (1: 8). ZIF-8 has remarkable thermal and chemical stability, tunable microporous structure, and a great potential for absorption, adsorption, and separation. Various physicochemical characterization techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD), field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), attenuated total reflected infrared spectroscopy (ATR-IR), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and surface area with pore textural properties by micromeritics gas adsorption equipment were performed to investigate the effect of base type additive triethylamine (TEA) on the morphology, crystallinity, yield, particle and crystal size, thermal stability and microporosity of ZIF-8 nanoparticles. The total quantity of basic sites and carbon dioxide (CO2) desorption aptitude was also calculated using CO2 temperature-programmed desorption (CO2-TPD) system. The pure ZIF-8 nanoparticles of 177 nm were formed at TEA/total mole ratio of 0.002. Furthermore, the size of ZIF-8 nanoparticles was decreased to 77 nm with increasing TEA/total mole ratio up to 0.004. The structures, particle sizes and textural properties of ammonia modified ZIF-8 particle can easily be tailored by the amount of aqueous ammonium hydroxide solution. The smallest ZIF-8 nanoparticles obtained were 75 nm after ammonia modification which shows excellent thermal stability and improved microporosity. The ZIF-8 basicity and uptakes of CO2 improved with TEA and ammonia modification which followed the order: A25ml–Z4 > Z4 > Z3 > Z5 > Z2 > A50ml–Z4. The proposed economical and efficient synthesis method has great potential for large-scale production of ZIF-8.

Keywords

Synthesis

Modification

Low molar ratio

High basicity

Desorption capacity

1 Introduction

From last three decades, porous materials have been extremely investigated due to their intrinsic characteristics such as tunable pore size, large pore volumes, and large surface area. Recently, zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs), a new class of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) with metal ions and organic linkers, have chosen as potential candidates for CO2 capture due to its low densities, high surface area with porous structure (Chen et al., 2014; Truong et al., 2015). Generally, ZIFs were synthesized in organic solvents via various methods such as solvothermal at high temperature (Cravillon and Münzer, 2009; Nordin et al., 2014; Park et al., 2006), microwave-assisted solvothermal (Bux et al., 2009), ultrasound (Tanaka et al., 2012), thermo-chemical (Lin et al., 2011) and accelerated aging (Cliffe et al., 2012). The use of expensive and flammable organic solvents such as N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF), N, N-diethylformamide (DEF) and methanol (CH3OH) in synthesis medium was resulted in harmful effects on the environment due to their toxic nature. A great deal of research has been done to develop such a green and economical synthesis process to produce ZIFs that can reduce the usage of organic solvents and environmental impacts. Recently deionized water has been explored as a green and economical solvent to replace organic solvents in the synthesis of ZIF-8. Pan et al. (2011) have reported a novel aqueous room temperature synthesis process for preparing ZIF-8 nanoparticle. They do not only introduce a new approach but also replace expensive organic solvent with cheap water during the synthesis process. However, the high molar ratio of zinc salt and an rganic ligand, Zn+2/Hmim (1: 70) was needed to produce ZIF-8 which result to more expensive synthesis method. Kida et al. (2013) successfully synthesized ZIF-8 at aqueous room temperature with the high surface area and micropore volume (0.65 cm3/g). Though the high ratio of reagents Zn+2/Hmim (1: 40) was required to produce pure ZIF-8, zinc hydroxide was formed as a byproduct at a lower molar ratio of Zn+2/Hmim. In addition, it was reported that organic ligand concentration could also be reduced by introducing base-type deprotonation agents into synthesis mixture such as polyamine (Shieh et al., 2013), triethylamine (TEA) (Nordin et al., 2014), pyridine (Jian et al., 2015), sodium formate (Tanaka et al., 2012) and n-butylamine (Yao et al., 2015). For example, Gross et al. (2012) prepared ZIF-8 nanocrystals in aqueous room temperature using TEA as a deprotonation agent. They successfully synthesized ZIF-8 at a relatively low ratio of Zn+2/Hmim (1:16). However, their nanoparticles showed low porosity and smaller micropore volume (0.32 cm3 g−1), smaller than ideal micropore volume (0.663 cm3 g−1) calculated by CERIUS software based on the crystal structure (Banerjee et al., 2008). Yao et al. (2013) showed a synthesis of ZIF-8 at a very low molar ratio of Zn+2/Hmim (1:2) in an aqueous system at room temperature using tri-block copolymer and ammonium hydroxide. Unfortunately, this process was not economical due to recycling of tri-block copolymer additive after ZIF-8 formation.

Therefore, the synthesis of ZIF-8 in aqueous room temperature with low reagents ratio and high micropore volume was still considered as a big challenge for future researchers. Compared to other ZIFs, ZIF-8 has exceptionally high thermal stability up to 600 °C with high CO2 adsorption capacity (Lee et al., 2015). Its structure contained zinc (Zn) atom interconnected with 2-methylimidazolate (Hmim) ligands and having sodalite topology with large cavities (11.6 Å) and small pore aperture (3.4 Å) (Song et al., 2012). The ZIF-8 supremacy in various aspects has attracted a lot of attention and its versatility is widely applicable. Emerging concern about CO2 capture has motivated researchers to develop efficient separation media. As in 2005, the world CO2 emissions were estimated at 28,051 million metric tons (MMT) and projected to 42,325 MMT for 2030 (Ullah Khan et al., 2018, 2017). Hence, it is a major challenge to capture CO2 from the ambient to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The adsorption is considered as one of the most promising, competitive and feasible technologies in the commercial and industrial applications because of the low energy requirement and ease of applicability over a relatively wide range of temperatures and pressures (Zhang et al., 2011). However, the success of this approach is dependent on the development of a low-cost adsorbent with a high CO2 adsorption capacity (Tsai and Langner, 2016). ZIF-8 has emerged as good CO2 separation media through molecular sieving (kinetic diameter of CO2 is 3.3 Å) (Nordin et al., 2015; Tsai and Langner, 2016). To date, most studies on ZIFs have mainly concentrated on the synthesis and characteristic but rare reports showed adsorption of CO2, basic sites evaluation, and the modification of ZIFs to improve their adsorption performance further.

The objective of this work is to produce smaller ZIF-8 nanoparticles with low reagents ratio, high thermal stability, and improved microporosity and CO2 desorption capacity. Also, the effect of TEA and ammonium hydroxide solution on the structural, thermal, pore textural and desorption properties is investigated during the synthesis process. The CO2 desorption and surface basicity of ZIF-8 samples before and after amine surface modification is probed by CO2-TPD. The NH3 influence on the surface chemistry of the ZIF-8 samples is also discussed and reported here.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO3)2·6H2O, 99% purity), 2-methylimidazole (Hmim, 99% purity) and ammonium hydroxide (NH4OH) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich while triethylamine (TEA, 99.5% purity) as a base-type additive was obtained from Alfa Aesar. In addition, deionized water was used as a solvent in the synthesis of ZIF-8. All these three chemicals were used as received without any further purification.

2.2 ZIF-8 nanoparticles synthesis in a base solution

The molar ratio of a zinc salt (Zn+2) and organic ligand (Hmim) (1:8) was used to improve the yield and reduce the chemical used during synthesis of ZIF-8 in the aqueous base solution. Typically, 2.95 g (1.98 mmol) of Zn (NO3)2·6H2O and 6.5 g (15.83 mmol) of Hmim were dissolved in 200 mL deionized water respectively. The appropriate amount of TEA was added to the Hmim solution as a deprotonation agent as shown in Table 1 (where the samples were denoted as Z1, Z2, Z3, Z4, and Z5), and then both aqueous solutions were mixed under stirring. This mixture was stirred at room temperature for 40 min. The product was obtained by repeated centrifugation (10,000 rpm for 10 min) and washed with deionized water to remove residual chemicals. Finally, the product was dried in an oven at 60 °C for 12 h. The yield of the product was calculated using Eq. (1).

2.3 Surface modification of ZIF-8 nanoparticles

Prior to amine modification, the ZIF-8 particles were dried at 100 °C for 24 h for complete evaporation of moisture and unreacted species. In this work, the volumes of ammonium hydroxide solution were fixed at 25 mL and 50 mL to represent a different amount of –NH3+ available for modification. Firstly, 1 g of the prepared ZIF-8 nanoparticles were dispersed into a predetermined volume of ammonium hydroxide solution with additional 10 mL deionized water. The solution was then sonicated for 60 min to break the particle bulks before being vigorously stirred for 24 h at room temperature. The product was collected by centrifugation (10,000 rpm for 10 min) and washed with deionized water before being dried in an oven at 100 °C overnight. The obtained samples were denoted as A25ml–Z4 and A50ml–Z4 which are further characterized and compared with unmodified samples.

2.4 Characterizations

2.4.1 Physico-chemical analysis

The field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images were taken using a Hitachi SU 8020 microscope. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed on a Rigaku smart lab diffractometer using CuKα radiation at 40 KV and 30 mA in the 2θ range of 3–100°. Attenuated total reflectance infrared (ATR-IR) spectroscopy analysis was performed using Shimadzu, IRTracer-100 (Single Reflection Diamond for Spectrum Two) to observe the functional groups of synthesized ZIF-8 samples. ATR–FTIR spectra of amine-modified samples were recorded with the Thermo Scientific™ Nicolet™ iS10FT-IR Spectrometer in the range of 500–4000 cm−1. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Q 500, TA Instrument, USA) was used to check the thermal stability of the synthesized samples at different TEA loading. TGA records the weight changes of the sample when heated from 30 to 900 °C at the heating rate of 10 °C/min under nitrogen atmosphere. The flow rate of N2 was used up to 40 mL/min. BET surface area and pores textural properties of synthesized ZIF-8 particles were measured by using Micromeritics gas adsorption analyzer ASAP 2010 instruments equipped with the commercial software for calculation and analysis. Samples were first degassed at 130 °C for 1 h under a helium blanket and then placed in the adsorption–desorption station for analysis. The apparent surface area was calculated using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) equation.

2.4.2 CO2 temperature programmed desorption (CO2–TPD)

CO2 temperature-programmed desorption tests were conducted to determine the total amount of basic sites on the surfaces of the ZIF-8 samples. Experiments were carried out on Auto Chem II 2920 instrument equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) (Micromeritics, USA). Firstly, the sample was pretreated by Helium (He) with a flow rate of 30 mL/min at 150 °C for 2 h and then cooled to room temperature (50 °C). After that, the sample was saturated with CO2 with a flow rate of 30 mL/min at 50 °C for 2 h. Following this adsorption, the sample was flushed with He at room temperature for 1.5 h to remove any physisorbed CO2. After the He flush, the sample was heated at a heating rate of 10 °C/min with a He flow rate of 30 mL/min, and meantime the desorbed CO2 was measured by the Auto Chem II 2920 instrument with a TCD ramp to 900 °C. Effluent curves of CO2 were recorded, which were called CO2-TPD curves. Finally, the surface basicity of the sample can be found out separately according to the amounts desorbed of CO2. The basic sites (mmol/g) was defined as the number of desorbed CO2 molecules between room temperature and 900 °C during the TPD. The amount of basic sites can be calculated from the area of the TPD spectrum as follows:

3 Results and finding

3.1 Structural investigation with surface properties

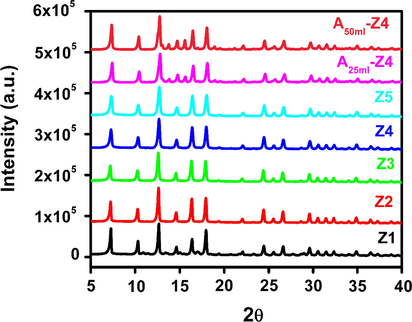

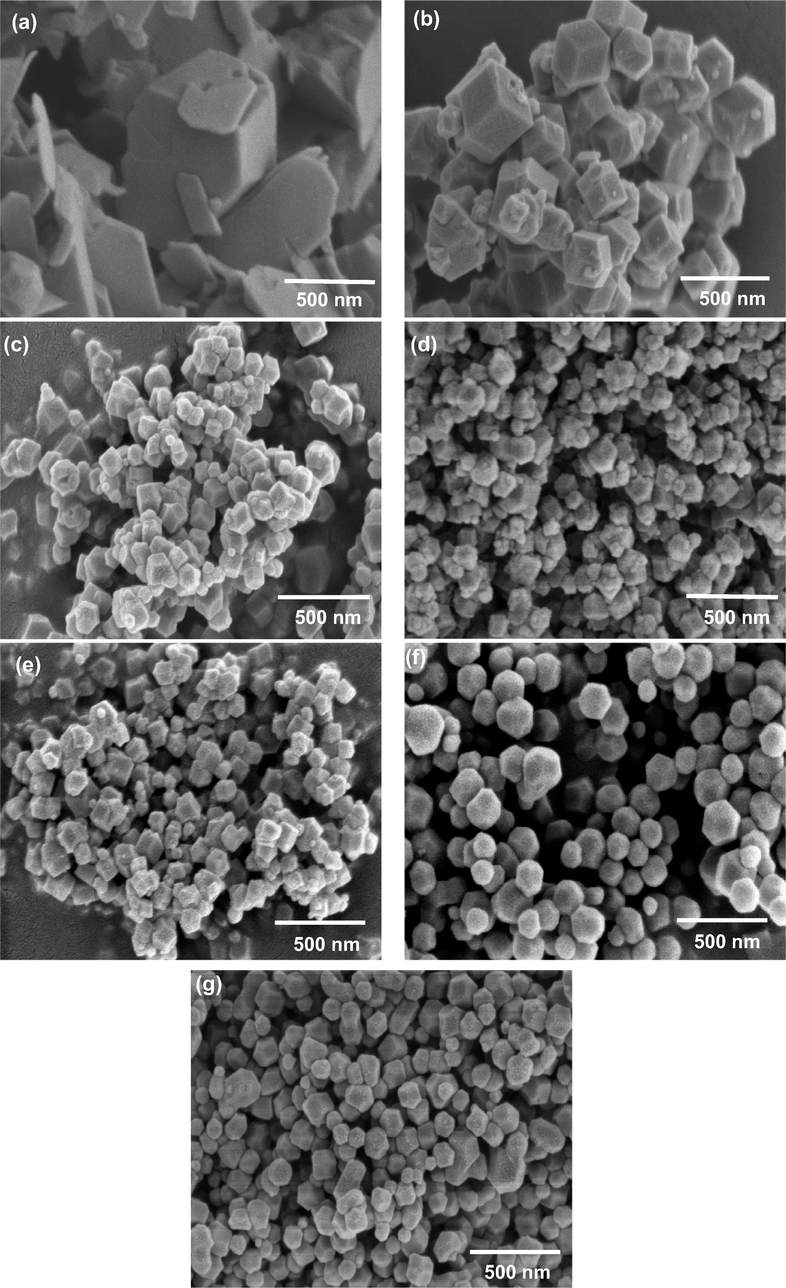

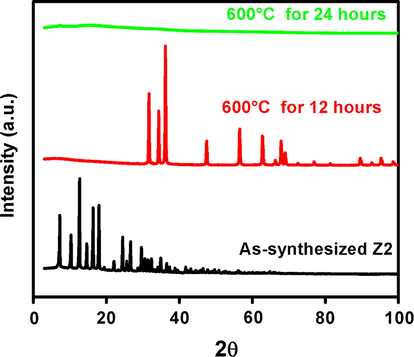

Fig. 1 shows the XRD pattern of prepared samples of ZIF-8 at various TEA/total mole ratio. The intensity of the gained peaks was in good agreement with the previously reported works (Pan et al., 2011; Tsai and Langner, 2016; Yao et al., 2013). In the first attempt (Fig. 1, sample Z1), a smaller TEA/total mole ratio of 0.001 was used to synthesize ZIF-8 particles. The synthesis solution turned cloudy after mixing of all reactants that show the occurrence of a reaction between zinc salt and organic linker (Hmim). However, low yield of the product (Table 1), the presence of unknown characteristics peaks in the XRD analysis at 2θ = 7.79, 10.91, 11.48, 13.62, 15.03, 17.11, 20.72, 21.69, and 22.67, and FESEM image (Fig. 2a) clearly identify that low TEA/total mole ratio was insufficient for the formation of ZIF-8 particles. The possible reason could be an incomplete reaction due to an insufficient amount of TEA for deprotonation of Hmim. When the TEA/total mole ratio was increased up to 0.002 (Fig. 1, sample Z2), the yield of the product was increased up to 90% (Table 1) and surprisingly, characteristic peaks of ZIF-8 for the planes {1 1 0}, {2 0 0}, {2 1 1}, {2 2 2}, {3 1 0}, {2 2 2}, {3 2 1}, {4 1 1}, {4 2 0}, {3 3 2}, {4 2 2}, {4 3 1}, {5 2 1} and {6 1 1} were clearly observed at 2θ = 7.24, 10.29, 12.64, 14.61, 16.37, 17.95, 19.38, 22.05, 23.01, 24.43, 25.53, 26.60, 28.61 and 32.32. Furthermore, FESEM images confirmed the three dimensional cubic hexagonal crystalline structure of ZIF-8 (Fig. 2b).

XRD pattern of synthesized and modified ZIF-8 samples at various TEA/total mole ratio: Z1 (0.001), Z2 (0.002), Z3 (0.003), Z4 (0.004), Z5 (0.006), A25ml–Z4 (0.004) and A50ml–Z4 (0.004).

FESEM analysis of the synthesized and amine modified ZIF-8 samples at various TEA/total mole ratio: (a) Z1 (0.001), (b) Z2 (0.002), (c) Z3 (0.003), (d) Z4 (0.004), (e) Z5 (0.006), (f) A25ml–Z4 (0.004) and (g) A50ml–Z4 (0.004).

The similar intensity of the peaks and high yield were observed when TEA/total mole ratio was further increased up to 0.003 and 0.004 for sample Z3, Z4 respectively as shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. Although similar peaks were observed for sample Z5, the yield of the product decreased. The possible reason was the usage of excess TEA in the synthesis solution that can introduce (−OH) groups on the organic ligands which react with zinc salt to form zinc hydroxide (Biemmi et al., 2009). So, it could be suggested that minimum TEA/total mole ratio of 0.002 was crucial and necessary to produce ZIF-8 nanoparticles with a molar ratio of reagents (Zn+2/Hmim = 8).

Sample Z4 was selected for ammonia modification because it gives smallest particle and crystal size (Table 2), high BET surface area and sufficient porosity (Table 3). Additionally, it showed a higher quantity of basic sites on their surfaces and thus improve the adsorption capacity and selectivity towards CO2. Two samples A25ml–Z4 and A50ml–Z4 were prepared and characterized that further compared with unmodified samples. The XRD pattern remains unchanged after ammonia modification showing the strong resistance of ZIF-8 particles against various amounts of ammonia solution (Fig. 1 A25ml–Z4 and A50ml–Z4). It was also observed that there is no apparent difference of peaks width of virgin and modified ZIF-8 samples.

Sample

δa

±0.0002εb

±0.0002Crystal size

Particle size

Scherrerc

±1 nmFESEMd

±2 nm

Z1

0.00071

0.00091

39.28

501

Z2

0.00087

0.00084

45.7

177

Z3

0.00088

0.00084

41.5

112

Z4

0.00082

0.00098

34.41

77

Z5

0.00090

0.00103

35.76

80

A25ml–Z4

0.00084

0.00099

34.60

75

A50ml–Z4

0.00068

0.00089

35.20

80

Sample

BET surface area (m2/g)

Langmuir surface area (m2/g)

Micropore volume (cm3/g)

Mesopore volume (cm3/g)

Micropore area (m2/g)

External surface area (m2/g)

Z2 (100 °C)

431

528

0.1341

0.08258

339

31

Z2 (300 °C)

1472

1605

0.5543

0.05234

1441

92

Z3 (100 °C)

453

575

0.1345

0.2180

342

67

Z3 (300 °C)

1504

1724

0.5657

0.1891

1437

111

Z4 (100 °C)

460

600

0.1330

0.3196

338

63

Z4 (300 °C)

1559

1699

0.5581

0.2095

1497

153

Z5 (100 °C)

515

679

0.1427

0.2988

362

40

Z5 (300 °C)

1234

1364

0.4616

0.1488

1194

68

A25ml–Z4

1589

1834

0.5982

0.2291

1521

122

A50ml–Z4

1247

1333

0.4509

0.1483

1211

36

The crystal size (which denoted as D) of the synthesized and modified ZIF-8 samples was measured using Debye-Scherrer equation, as shown in Eq. (3) (Abdel-wahab et al., 2016), and FESEM images were used to calculate particle size. It was observed that particle size decreased from 177 to 77 nm and crystal size from 45.7 nm to 34.41 nm when TEA/total mole ratio was increased from 0.002 to 0.006 respectively as shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2b, c, d, e with exception of sample Z1 (Fig. 2a) that give large particle size due to the incomplete reaction as stated above. The rapid deprotonation of Hmim at higher TEA loading was the main reason of particle size reduction, produces more reactive sites on the organic ligands to fast the chemical reaction with Zn+2 ions. Moreover, using ammonia modification (A25ml–Z4) causes the reduction of particle and crystal size (Table 2) due to further deprotonation of the unreacted imidazole ligands in the pores and this accelerates the crystallization process (Fig. 2f). But at higher loading of ammonium hydroxide (A50ml–Z4) excess –NH group would reside within the pores lead to increase of particle size (Fig. 2g).

-

–

D is crystal size (nm),

-

–

B is full-width at half maximum of the peak in radian,

-

–

θ is the measured diffraction angle of the peak, and

-

–

λ is x-ray wavelength of CuKα (0.1542 nm).

Moreover, the dislocation density (δ) is measured by the Eq. (4) (Jilani et al., 2016).

It gives more understanding of the number of defects present in the crystals. Very small defects were observed in ZIF-8 particles that slightly increase with decrease particles size from Z1 to Z5 as shown in Table 2. But fewer defects were found after ammonia modification. Strain-induced broadening arising from crystal imperfections and distortion are related by lattice strains that are calculated by Eq. (5) (Tan et al., 2015). Lattice strain slightly increases with reduction in particle size but decreases after modification of ZIF-8 nanoparticle (Table 2).

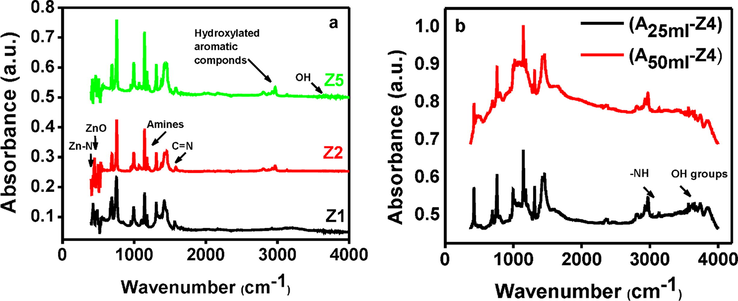

3.2 Functional groups characteristic

The bond stretching vibration of involved functional groups at various frequencies was identified by ATR-IR spectra. To check the effect of TEA, three samples with minimum (Z1), medium (Z2) and the maximum (Z5) amount of TEA were selected for this analysis, shown in Fig. 3a. The spectra showed the vibrations of imidazole and Zn+2 ions due to their bond origin, thus, it gives the information about basic or acidic nature of the sample. The spectra of all tested samples showed a good agreement with previous work (Chmelik et al., 2012) and main peaks were the same as reported previously (Park et al., 2006). The peaks at 2800–3100 cm–1 were due to the presence of aromatic, alkane and alkene stretch of the imidazole unit. The peak at 1585 cm–1 was attributed to C⚌N stretching, while bands at 1350–1500 cm–1 were attributed to the entire ring stretching (Hu et al., 2011). The peaks in the spectral region of 1180–1360 cm–1 were due to the stretching of amines. The spectral peaks in the region of 900–1350 cm−1 were related to the alkane in-plane blending while those below 800 cm–1 were named as out of plane bending (Hu et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). The peaks at 421 cm–1 and 450 cm–1 showed the unique stretching of Zn—N and Zn—O respectively.

(a) ATR-IR spectrum analysis of synthesized ZIF-8 samples: Z1 (0.001), Z2 (0.002) and Z5 (0.006) (b) FTIR spectrum analysis of amine modified ZIF-8 samples.

Furthermore, it was observed that excessive addition of TEA (sample Z5) in the synthesis solution would produce free hydroxyl (—OH) groups that react with the organic ligands to produce hydroxylated aromatic compounds. Subsequently, ATR-IR analysis of this sample clearly identified the presence of aromatic compounds at 3000–3100 cm−1, and free —OH stretch at 3500–3700 cm−1.

In order to check the changes in functional groups associated with ammonia modification of the sample Z4, FTIR analysis was carried out. Fig. 3b shows the FTIR spectra of the modified samples at various amounts of ammonia solution (A25ml–Z4 and A50ml–Z4). It was noticed that the spectra of these modified samples matched well with the unmodified ZIF-8 spectra except some differences. As the spectra of modified samples clearly showed a new peak at 3400–3500 cm–1 which was due to –NH groups appeared after modification (Zhang et al., 2011). Also, peak at 3650–3800 cm–1 assigned to —OH of the adsorbed H2O was clearly observed.

3.3 Thermal stability analysis

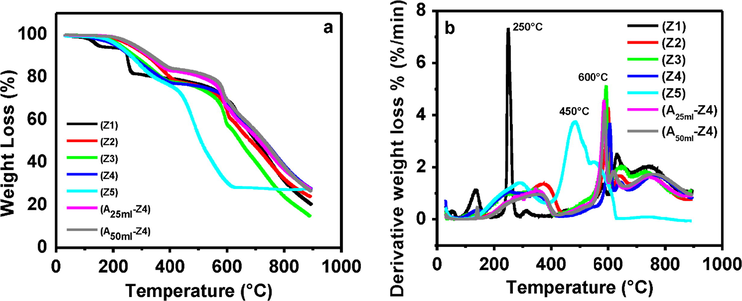

The thermal stability of the synthesized and ammonia modified samples was measured by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) in which the mass of the sample was monitored as a function of temperature as shown in Fig. 4a. As it was proven above in XRD (Fig. 1, sample Z1) and FESEM (Fig. 2a) results that low TEA/total mole ratio of 0.001 was not favorable for the production of ZIF-8, give low stability, as sudden weight loss detected around 250 °C (Fig. 4a, sample Z1). Nevertheless, other samples were reduced gradually in weight losses and shown remarkable stability as their sudden weight loss was observed at 600 °C. Sample Z5 shows lower stability (450 °C) which indicated the presence of zinc hydroxide due to excess usage of TEA during synthesis. The stability of compounds having zinc hydroxide is around 420 °C lower than ZIF-8 particles (Cursino et al., 2011).

(a) Thermal stability analysis of synthesized and amine modified ZIF-8 samples with weight loss profile at various temperatures: Z1 (0.001), Z2 (0.002), Z3 (0.003), Z4 (0.004), Z5 (0.006), A25ml–Z4 (0.004) and A50ml–Z4 (0.004) (b) Thermal stability analysis of synthesized and modified ZIF-8 samples with derivative of weight loss profile at various temperatures: Z1 (0.001), Z2 (0.002), Z3 (0.003), Z4 (0.004), Z5 (0.006), A25ml–Z4 (0.004) and A50ml–Z4 (0.004).

Additional confirmation of the thermal stability of samples was done by measuring the peaks at different temperature via derivative of the weight loss curves (Fig. 4b). The synthesized samples showed three peaks, representative of their three various weight loss temperatures or thermal events. The first derivative peak (Tp1) at a temperature around 100 °C showed the initial weight loss, ascribed to the evaporation of trapped deionized water molecules from the pores of unreactive species (e.g. Hmim) (Song et al., 2012). The second weight loss (Tp2) was observed around 250 to 300 °C, associated to carbonization of organic ligand molecules present in ZIF-8 structure (Park et al., 2006) and (Nordin et al., 2014). The third weight loss (Tp3) (Fig. 4b, Z2, Z3, Z4, A25ml–Z4 and A50ml–Z4) happened at 600 °C indicated the point of highest rate of weight loss on a curve, attributed to the decomposition of organic linkers in ZIF-8. The point of highest rate of weight loss for the sample Z1 and Z5 was 250 °C and 450 °C respectively.

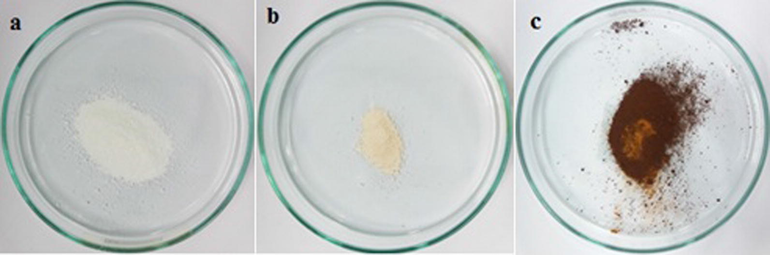

Further investigation was done to reconfirm the stability of ZIF-8 particles by heating in a furnace at 600 °C. Sample Z2 was selected because it provides the pure ZIF-8 particles at minimum TEA/total mole ratio of 0.002. The XRD patterns of sample Z2 heated at 600 °C for 12 h and 24 h are shown in Fig. 5. It was indicated that after 12 h, the ZIF-8 crystal structure was entirely collapsed and the colour of the sample was changed from white to yellow (Fig. 6a, b). After 24 h heating process at 600 °C, the peaks were disappeared suggesting the formation of amorphous solids and the colour of the sample was changed from yellow to dark brown (Fig. 6b, c). Further, it was also concluded that the ammonia modification of ZIF-8 particles has no significant effect on its thermal stability.

The XRD pattern of sample Z2 (0.002) (Zn+2/Hmim = 0.002) heated at 600 °C for 12 h and 24 h.

Photographs of the sample Z2 (0.002): (a) As-synthesized, (b) 600 °C for 12 h, and (c) 600 °C for 24 h.

3.4 Pore size and textural properties

The pore textural properties of synthesized and modified samples were presented in Table 3. Firstly, it was observed that BET and Langmuir surface area were smaller than previously published works (Chen et al., 2014; He et al., 2014). The incomplete activation of the prepared samples at high temperature was possibly the reason for the low surface area. The samples were heated at 100 °C before sorption measurement for surface area, but this temperature was not sufficient to remove guest molecules and unreacted species, led to a decrease the surface area (Kida et al., 2013). Now, ZIF-8 samples were heated at 300 °C in an oven to eliminate all the entrapped and unreacted molecules. Surprisingly, surface properties were enhanced (Table 3) and showed significant improvement compared to previously reported work (Tsai and Langner, 2016). The BET surface area of the smallest particles Z4 was increased up to 1559 m2/g with high micropores volume of 0.5581 cm3/g. The external surface area was also increased from 92 to 153 m2/g with decreasing particles size, which confirmed the fact that smaller particles have larger external surface area and vice versa (Tsai and Langner, 2016). The external surface area of smallest ZIF-8 nanoparticles (Table 3, sample Z4) was 1.32 times that of commercial ZIF-8 (116 m2/g) (Tsai and Langner, 2016). Moreover, surface properties improved when a smaller amount of ammonia solution was used but at higher loading amine would reside within the pores to cause blockage of the pores (Zhang et al., 2011).

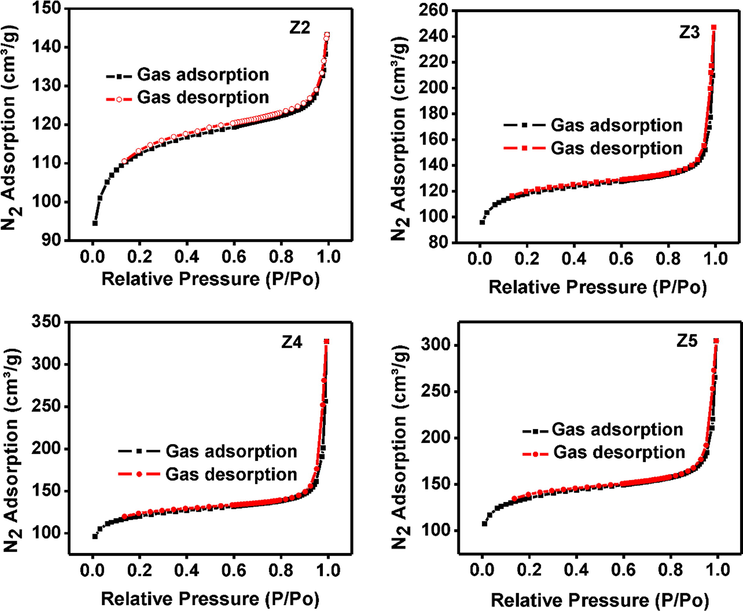

Fig. 7 showed the nitrogen sorption isotherms for synthesized ZIF-8 samples at 100 °C. Low gas adsorbed at 100 °C was observed possibly due to low BET surface and pore size area (Table 3). Moreover, the amount of adsorbed gas increased from 143 to 328 cm3/g for sample Z2 to Z4 respectively as the surface properties improve with size reduction.

Nitrogen sorption isotherms of synthesized ZIF-8 samples at 100 °C with different TEA/total mole ratio: Z2 (0.002), Z3 (0.003), Z4 (0.004) and Z5 (0.006).

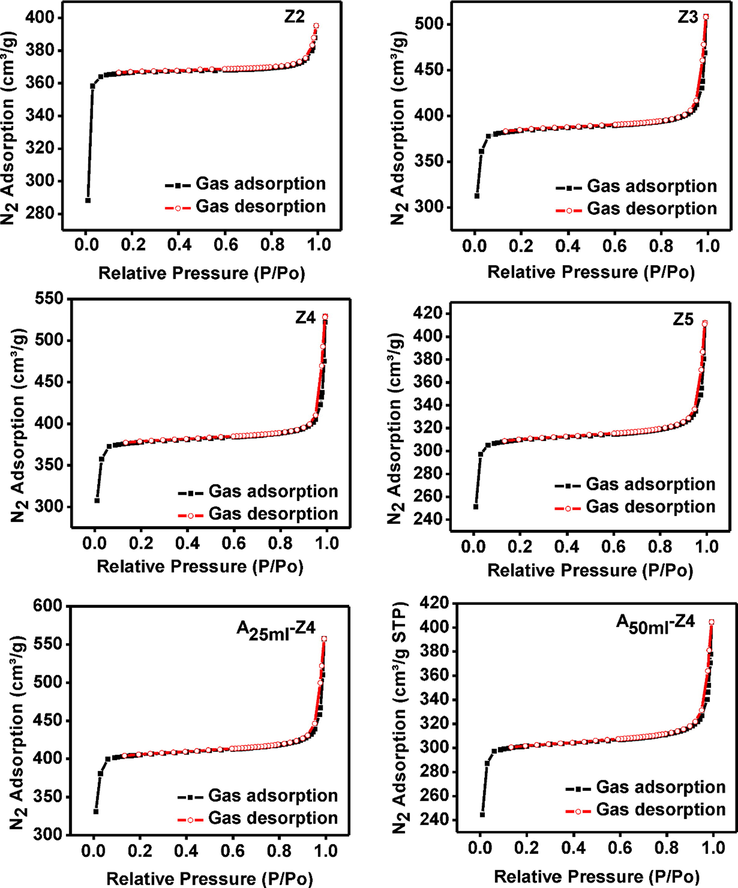

Fig. 8 showed the nitrogen sorption isotherms at 300 °C. In this case, gas adsorbed even at very low relative pressure, indicating the enhanced microporosity, though at high relative pressure gas adsorbed due to both micropores and mesopores of the ZIF-8 structure. Also, adsorbed gas in heat treated (Z2, Z3, and Z4) samples increased from 395 to 529 cm3/g probably due to the improvement of surface area and porosity (Fig. 8 and Table 3). Moreover, typical Type I isotherms for all samples were witnessed of their microporosity (Rowsell and Yaghi, 2004) (Figs. 7, 8). However, the behavior of the isotherms at P/P0 > 0.95 changes to Type IV, confirm the presence of mesoporous structure (Zhang et al., 2011).

Nitrogen sorption isotherms of synthesized and amine modified ZIF-8 samples at 300 °C with various TEA/total mole ratio: Z2 (0.002), Z3 (0.003), Z4 (0.004) and Z5 (0.006), A25ml–Z4 (0.004) and A50ml–Z4 (0.004).

All the surface properties increased after modification of sample Z4 when the volume of ammonium hydroxide solution was fixed at 25 mL (A25ml–Z4). The increased amount of adsorbed gas from 529 to 558 cm3/g attributed to increasing surface areas and microporosity (Fig. 8). The further removal of guest molecules has increased pores availability after modifications indicating pore reopening and formation of new pores due to cage reordering (Zhang et al., 2013). The types of a pore formed or reopened during the modification were highly dependent on the amount of –NH3+ available for modification (Zhang et al., 2011). The high volume of ammonium hydroxide solution (A50ml–Z4) causes the significant reduction of porosity probably due to pore constriction (Table 3). Subsequently, the amount of adsorbed gas also decreased from 558 to 405 cm3/g.

3.5 Desorption of CO2

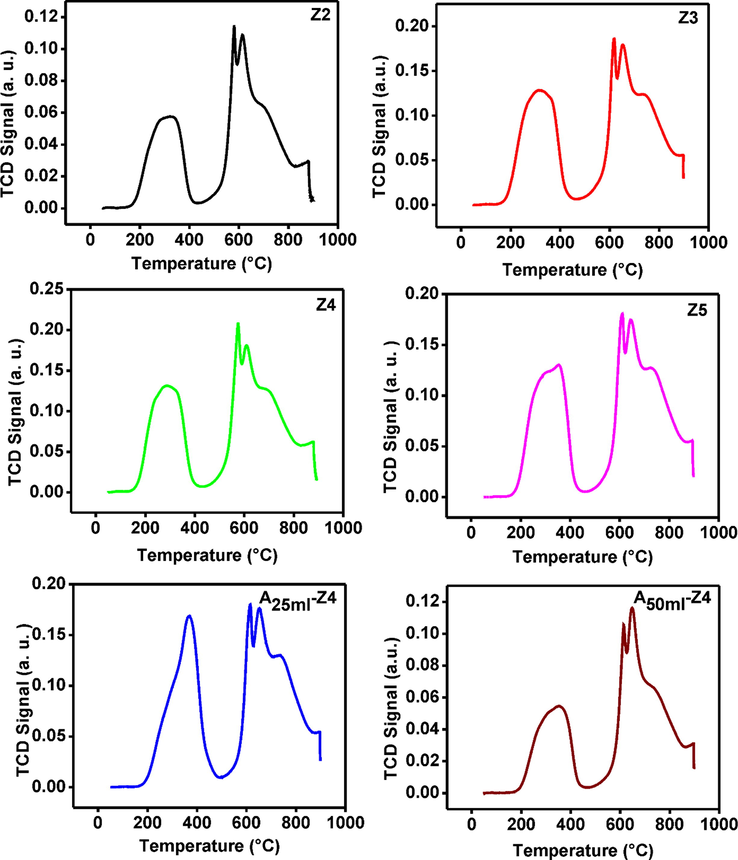

The total desorbed CO2 on ZIF-8 samples was calculated from CO2-TPD isotherms (Fig. 9) according to Eq. (2). All synthesized ZIF-8 samples have significant high basic sites (Table 4) compared with previously reported work (Khan et al., 2018; Klepel and Hunger, 2005; Zhang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013). The strength of the basic sites of the synthesized and amine modified ZIF-8 samples significantly increased with the decrease of particle size and followed the order: A25ml–Z4 > Z4 > Z3 > Z5 > Z2 > A50ml–Z4. Furthermore, the uptakes of CO2 increased proportionally with the basic sites on the surfaces of the ZIF-8 samples. This increase in basicity was attributed to amine basic groups involved in TEA which adsorbed more CO2 being an acidic molecule. But excess usage of TEA during synthesis (sample Z5) can reduce the CO2 adsorption and basic sites. The possible reason was the same as described above. The increase basicity and CO2 adsorption for modified ZIF-8 sample (A25ml–Z4) were mainly attributed to the presence of N–H groups, as shown in Fig. 3b and more pores availability after modification. But higher loading of ammonium hydroxide solution (A50ml–Z4) causes the reduction of basic sites as well as CO2 adsorption possibly due to blockage of the pores.

CO2-TPD spectra of synthesized and amine modified ZIF-8 samples at various TEA/total mole ratio: Z2 (0.002), Z3 (0.003), Z4 (0.004) and Z5 (0.006), A25ml–Z4 (0.004) and A50ml–Z4 (0.004).

Sample

Temperature (°C)

Amount of basic sites (mmol/g)

Z2

310.1

5.64

580.5

1.149

611.0

1.32

660.5

10.32

Total

18.43

Z3

100.0

0.0049

313.3

8.085

618.2

2.22

653

10.58

874.6

0.342

Total

21.23

Z4

286

7.55

575.4

3.25

610.4

10.76

880.3

0.872

Total

22.43

Z5

332.1

7.17

607.8

2.59

649.8

10.29

893

0.0107

Total

20.06

A25ml–Z4

115.4

0.018

367.4

8.83

614.4

2.52

651

10.89

894.3

0.48

Total

22.74

A50ml–Z4

345.1

5.75

614.3

2.34

646.9

10.31

Total

18.40

4 Conclusions

A new approach was presented to synthesize ZIF-8 in an aqueous solution at ambient conditions with a relatively low molar ratio of Zn+2/Hmim (1: 8), small particle size, improved porosity with improved thermal stability and CO2 desorption capacity. Minimum TEA/total mole ratio of 0.002 was required to produce pure phase ZIF-8 crystals, but particle size decreased from 177 to 77 nm as the TEA/total mole ratio increased from 0.002 to 0.004. However, an excessive usage of TEA was not favourable. The TEA/total mole ratio of 0.004 was played a major role in controlling the crystal growth, porosity, and CO2 desorption capacity. The surface area and microporosity of ZIF-8 particles increased up to 1559 m2/g and 0.5581 cm3/g respectively after heat treatment at 300 °C with excellent thermal stability around 600 °C. Additionally, the addition of TEA significant improves the basic strength of the surfaces up to 22.43316 mmol/g which improve the adsorption capacity of CO2. Further, it is concluded that ZIF-8 particles improved its structures, particle sizes, textural properties, basic sites strength and CO2 desorption capacity after ammonia modification using 25 mL ammonium hydroxide solution. We expect this new synthesis approach with low reagent ratio and base type additive will be beneficial and stimulate new ZIFs materials in future studies and thus reduce the production cost with improving basicity and adsorption capacity of CO2.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Universiti Teknologi Malaysia under the Research University Grant Tier 1 (Project number: Q. J130000.2546.12H25) and Nippon Sheet Glass Foundation for Materials Science and Engineering under Overseas Research Grant Scheme (Project number: R. J130000.7346.4B218). The authors would also like to thank Research Management Centre, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia for the technical support. Lastly, the first author would also like to thank National University of Science and Technology, Pakistan for their scholarship under Faculty Development Programme (FDP).

References

- Enhanced the photocatalytic activity of Ni-doped ZnO thin films: Morphological, optical and XPS analysis. Superlatt. Microstruct.. 2016;94:108-118.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- High-throughput synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks and application to CO2 capture. Science (80-.). 2008;319(5865):939-943.

- [Google Scholar]

- High-throughput screening of synthesis parameters in the formation of the metal-organic frameworks MOF-5 and HKUST-1. Microporous Mesoporous Mater.. 2009;117:111-117.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zeolitic imidazolate framework membrane with molecular sieving properties by microwave-assisted solvothermal synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2009;131:16000-16001.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zeolitic imidazolate framework materials: recent progress in synthesis and applications. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2:16811-16831.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hindering effects in diffusion of CO2/CH4 mixtures in ZIF-8 crystals. J. Memb. Sci.. 2012;397:87-91.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Accelerated aging: a low energy, solvent-free alternative to solvothermal and mechanochemical synthesis of metal–organic materials. Chem. Sci.. 2012;3:2495.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid room-temperature synthesis and characterization of nanocrystals of a prototypical zeolitic imidazolate framework. Chem. Mater.. 2009;21(8):1410-1412.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of confinement of anionic organic ultraviolet ray absorbers into two-dimensional zinc Hydroxide Nitrate Galleries – Cópia.pdf. J. Braz. Chem. Soc.. 2011;22:1183-1191.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aqueous room temperature synthesis of cobalt and zinc sodalite zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Dalt. Trans.. 2012;41(18):5458-5460.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 from a concentrated aqueous solution. Microporous Mesoporous Mater.. 2014;184:55-60.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In situ high pressure study of ZIF-8 by FTIR spectroscopy. Chem. Commun. (Camb). 2011;47:12694-12696.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Water-based synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 with high morphology level at room temperature. RSC Adv.. 2015;5:48433-48441.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nonlinear optical parameters of nanocrystalline AZO thin film measured at different substrate temperatures. Phys. B Condens. Matter. 2016;481:97-103.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structural transition from two-dimensional ZIF-L to three-dimensional ZIF-8 nanoparticles in aqueous room temperature synthesis with improved CO2 adsorption. Mater. Charact.. 2018;136:407-416.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Formation of high crystalline ZIF-8 in an aqueous solution. CrystEngComm. 2013;15(9):1794-1801.

- [Google Scholar]

- Temperature-programmed desorption (TPD) of carbon dioxide on alkali-metal cation-exchanged faujasite type zeolites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.. 2005;80:201-206.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework core-shell nanosheets using zinc-imidazole pseudopolymorphs. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:18353-18361.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Solvent/additive-free synthesis of porous/zeolitic metal azolate frameworks from metal oxide/hydroxide. Chem. Commun.. 2011;47:9185-9187.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Facile modification of ZIF-8 mixed matrix membrane for CO2/CH4 separation: synthesis and preparation. RSC Adv.. 2015;5(54):43110-43120.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aqueous room temperature synthesis of zeolitic imidazole framework 8 (ZIF-8) with various concentrations of triethylamine. RSC Adv.. 2014;4:33292.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rapid synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) nanocrystals in an aqueous system. Chem. Commun.. 2011;47:2071.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Exceptional chemical and thermal stability of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.. 2006;103:10186-10191.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal–organic frameworks: a new class of porous materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater.. 2004;73(1):3-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Water-based synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-90 (ZIF-90) with a controllable particle size. Chem. – A Eur. J.. 2013;19:11139-11142.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) based polymer nanocomposite membranes for gas separation. Energy Environ. Sci.. 2012;5:8359-8369.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantum mechanical predictions to elucidate the anisotropic elastic properties of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks: ZIF-4 vs. ZIF-zni. CrystEngComm. 2015;17(2):375-382.

- [Google Scholar]

- Size-controlled synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) crystals in an aqueous system at room temperature. Chem. Lett.. 2012;41:1337-1339.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Expanding applications of zeolite imidazolate frameworks in catalysis: synthesis of quinazolines using ZIF-67 as an efficient heterogeneous catalyst. RSC Adv.. 2015;5:24769-24776.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of synthesis temperature on the particle size of nano-ZIF-8. Microporous Mesoporous Mater.. 2016;221:8-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biogas as a renewable energy fuel – A review of biogas upgrading, utilisation and storage. Energy Convers. Manag 2017

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Status and improvement of dual-layer hollow fiber membranes via co-extrusion process for gas separation: A review. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2018

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Strategies for controlling crystal structure and reducing usage of organic ligand and solvents in the synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks. CrystEngComm. 2015;17(27):4970-4976.

- [Google Scholar]

- High-yield synthesis of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks from stoichiometric metal and ligand precursor aqueous solutions at room temperature. CrystEngComm. 2013;15:3601.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Improvement of CO2 adsorption on ZIF-8 crystals modified by enhancing basicity of surface. Chem. Eng. Sci.. 2011;66:4878-4888.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enhancement of CO2 Adsorption and CO2/N2 Selectivity on ZIF-8 via Postsynthetic Modification. AIChE J.. 2013;59:2195-2206.

- [Google Scholar]