Translate this page into:

Effects of supercritical CO2 exposure on diffusion and adsorption kinetics of CH4, CO2 and water vapor in various rank coals

⁎Corresponding authors. xidongdu@126.com (Xidong Du), hxw_2004@163.com (Xianwei Heng)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The physico-chemical effects caused by supercritical CO2 (ScCO2) exposure is one of the leading problems for CO2 storage in deep coal seams as it will significantly alter the flow behaviors of gases. The main objective of this study was to investigate the effects of ScCO2 injection on diffusion and adsorption kinetics of CH4, CO2 and water vapor in various rank coals. The powdered coal samples were immersed in ScCO2 for 30 days using a high-pressure sealed reactor. Then, the diffusion and adsorption kinetics of CH4, CO2 and water vapor in the coals both before and after exposure were examined. Results indicate that the diffusivities of CH4 and CO2 are significantly increased due to the combined matrix swelling and solvent effect caused by ScCO2 exposure, which may induce secondary faults and remove some volatile matters that block the pore throats. On the other hand, the diffusivities of water vapor are reduced due to the elimination of surface functional groups with ScCO2 exposure. It is concluded that density of the surface function groups is the controlling factor for water vapor diffusion rather than the pore properties. The unipore model and pseudo-first-order equation can simulate the diffusion and adsorption kinetics of CH4 and CO2 very well, but the unipore model is not capable of well describing water vapor diffusion. The effective diffusivity (De), diffusion coefficient (D) and adsorption rates (k1) of CH4 and CO2 are significantly increased after ScCO2 exposure, while the values of water vapor are decreased notably. Thus, the injection of ScCO2 will efficiently improve the transport properties of CH4 and CO2 but hinder the movement of water molecules in coal seams.

Keywords

Supercritical CO2

Diffusion

Adsorption kinetics

CH4 and CO2

Water vapor

1 Introduction

Coalbed methane (CBM) has been deemed as a clean energy resource with priority of less carbon emission than conventional fossil fuels such as coal and petroleum (White et al., 2005). At the same time, the world is committing to lower the carbon dioxide (CO2) level in atmosphere to ameliorate global warming. As an alternative, CO2 geological storage in deep un-minable coal seams has been recognized as an effective approach due to the benefits of combined carbon emission cut and CBM recovery enhancing (Busch and Gensterblum, 2011; Du et al., 2021; Perera, 2018). The technical development of coal seam CO2 storage with enhanced CBM recovery (CO2-ECBM) requires reliable information on the interaction of CO2 with coal. An improved understanding of this process is significant both to predict the transport and storage of gases and to model the changes of CO2 injectivity and CH4 recovery over time (Zhou et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020; Du et al., 2022).

Coal is a highly heterogeneous porous rock that covers a wide range of pore diameter, which consists of micropores (<2 nm), mesopores (2–50 nm) and fractures (>50 nm) (Okolo et al., 2015). The fractures and mesopores in coal would facilitate the transportation of fluids, while the micopores provide abundant adsorption sites. After injected, CO2 molecules may first penetrate the fractures and mesopores, and then competitively replace pre-adsorbed methane (CH4) in micropores. Finally, the CO2 molecules will be retained in the pore space of the coal seam (Zhao et al., 2016). Specifically, the migration of gases in coal seam is distinguished by two distinct mechanisms, i.e., flow through the fractures and diffusion within the mesopores. The former is governed by pressure and can be modeled using Darcy’s law, while the latter is concentration driven and is usually represented by Fick’s law (Jasinge et al., 2012). In comparison, coal seam is tightly compacted with lower permeability than the conventional reservoirs, making gas transmission highly difficult (Tan et al., 2018). Accordingly, diffusion is the main gas migration mechanism in the coal seam, which controls CO2 injectivity and CH4 recovery rates. On the other hand, adsorption kinetics is another key parameter in evaluating gas migration (Dim et al., 2021). Therefore, knowledge of diffusion as well as adsorption kinetics of CH4 and CO2 is important for reservoir simulation and optimization of CO2-ECBM.

The presence of seam water is often assumed to adversely influence CO2 injectivity and CH4 recovery. As reported by Saliba et al. (2016), water may lead to reduced uptake capacities of CH4 and CO2 by partial competition for adsorption sites or by hindering the access of other molecules to pores. It is reasonable to assume that the mechanism of water vapor diffusion and adsorption is quite different from CH4 and CO2. This is due to the tendency of water molecules to form hydrogen bonds with oxygen containing functional groups and other adsorbed water molecules, followed by the formation of water clusters and finally pore filling (Du and Wang, 2022; Rutherford, 2006). Moreover, the uptake of water vapor may differ significantly among different rank coals due to the variation in pore properties and density of surface functional groups (Chen et al., 2012).

The targeted coal seams for CO2-ECBM projects are located at deep underground with optimum depths of 800–1000 m. The pressure and temperature corresponding to these sites are higher than the critical values of CO2 (Pc = 7.38 MPa, Tc = 31.8℃). Supercritical CO2 (ScCO2) has unique physical properties comparing to subcritical CO2, such as gas-like viscosity and flow properties coupled with liquid-like density and dissolution power (Vishal and Singh, 2015). The unique properties of ScCO2 may cause the coal matrix to swell, which will compress the porous medium in coal seam, leading to higher resistances for gas transportation (Day et al., 2008; Pluymakers et al., 2018). Further, secondary faults may be generated as a consequence of coal matrix swelling, along with differential accessibility of CO2 to coal structure (Hol et al., 2012). On the other hand, ScCO2 is capable of dissolving in coal matrix, leading to rearrangement in the molecular structures of coal (Goodman et al., 2006). As structural property is one of the key factors upon gas transportation, the diffusion and adsorption kinetics of gases will be substantially changed with ScCO2 injection (Kutchko et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2015).

So far, in spite of the great number of studies on interaction of ScCO2 and coal, studies about the impact of ScCO2 exposure on diffusion and adsorption kinetics of CH4, CO2 and water vapor in coal are rare. Further, it has been demonstrated that the physico-chemical properties vary significantly among different rank coals, which may also make a difference in gas transportation (Liu et al., 2018). Therefore, it is valuable to study the effects of ScCO2 exposure on diffusion and adsorption kinetics of CH4, CO2 and water vapor in various rank coals.

The main objective of this study is to compare the diffusion and adsorption kinetics of CH4, CO2 and water vapor in various rank coals before and after ScCO2 exposure for estimation of the changes of CO2 injectivity and CH4 recovery over time. To address this issue, the powdered coals were immersed in ScCO2 for 30 days using a high pressure sealed reactor. Then, the diffusion isotherms of CH4, CO2 and water vapor both before and after ScCO2 exposure were determined using the gravimetric method. Finally, the unipore model and pseudo-first-order equation were applied to determine the parameters of diffusion and adsorption kinetics, namely, effective diffusivity (De), diffusion cofficient (D) and adsoprtion rate (k1).

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Sample collection and preparation

The samples selected for this study were drilled from four actively mined coal seams in China, i.e., SD coal (from Daliuta coal mine, Shendong coalfield), HZ coal (from Zhaolou coal mine, Heze coalfield), GZ coal (from Guiyuan coal mine, Guizhou coalfield), SC coal (from Datong mine, Sichuan coalfield).

Coal lumps were cut from mining faces using a diamond wire saw. The as received bulk coal samples were sealed in plastic bags flushed with N2 gas on the way from the mine to laboratory to minimize the structural changes by atmospheric oxidation. In laboratory, the bulk coal samples were prepared in the form of coarse powder by ground and sieved to + 10–8 mesh (2.36–2.00 mm) particles size. The measurements in this study were carried out on this fraction.

2.2 Sample characterization

Prior to diffusion isotherm measurements, the pore structure of the coal samples was thoroughly characterized by utilizing low-pressure N2 and CO2 adsorption methods and the results have been reported in our previous study (Liu et al., 2019). In addition, vitrinite reflectance (R0), proximate and ultimate analyses were employed, and the results are summarized in Table 1. Based on the R0 results, the coal samples can be categorized as different ranks following the Chinese standard GB/T 5751–2009, namely, lignite (SD), medium-volatile bituminous (HZ), low-volatile bituminous (GZ) and anthracite (SC).

Sample

R0 (%)

Proximate Analyze (wt %)

Ultimate Analyze (wt % daf)

Cfix

Vdaf

M

Aad

C

O

H

N

SD

0.42

53.6

37.0

2.5

19.4

72.7

20.5

4.9

1.2

HZ

0.81

65.1

28.7

1.5

16.2

82.5

11.0

4.6

1.1

GZ

1.14

78.3

6.1

2.1

10.5

86.9

6.0

4.0

1.2

SC

1.86

73.9

12.8

2.0

13.3

90.1

2.1

3.8

1.0

Proximate analyse indicates that the coal samples are identical regarding maceral composition. GZ coal contains the highest fixed carbon (Cfix) and the lowest volatile (Vdaf) contents, corresponding to 78.3 % and 6.1 %, respectively, while SD coal contains the lowest Cfix and the highest Vdaf contents, corresponding to 53.6 % and 37.0 %, respectively. On the other hand, the ash (Aad) and the moisture (M) do not follow such a monotonic trend. With the increasing coal rank, the carbon element (C) increases while the hydrogen element (H) and the oxygen element (O) decrease. The nitrogen element (N) is extremely low (around 1 %) and does not show any correlations with coal rank.

2.3 Exposure of coal sample to ScCO2

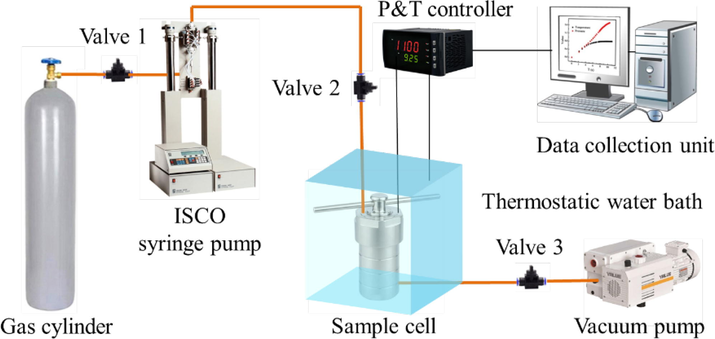

A specifically designed high-pressure sealed reactor was applied to simulate the process of CO2 storage in deep coal seams. As schematically illustrated in Fig. 1, the apparatus is consists of three individual units working together: i) a pressure charge unit, ii) a sample cell, and iii) a data collection unit. The coal sample (weighing 100 ∼ 200 g) was first inserted inside the sample cell. Then, CO2 was continuously injected into the sample cell using an ISCO (260D) syringe pump (Teledyne ISCO, USA) with a mass flow rate of ∼ 20 g/min until the target pressure was achieved. The sample cell was immersed in a high-resolution thermostatic water bath to maintain the system temperature within ± 0.1 ℃ of the set-point. The data collection unit allows the pressure and temperature in the sample cell to be detected within time intervals of 10 s.

Schematic diagram of coal-ScCO2 interaction system.

Before reaction, the coal sample was degassed at 80 ℃ under a high vacuum level (∼10-5 Pa) to remove air and some other impurities. The injection pressure of CO2 of each run was set at 16 MPa, under a constant operating temperature of 40 ℃, simulating the pressure and temperature in the coal seam at a burial depth of around 1000 m (Perera, 2017). To ensure sufficient physico-chemical reactions, the reaction time was set as 30 days. Then, CO2 was gradually released over an approximate rate of 0.05 MPa/min to minimize the influences on coal physical structure due to the sudden change in pressure. After exposure, the samples were sealed in plastic wraps and stored at room temperature. The tests in this study were repeated for three times to eliminate the possible errors. The final result presented is an average value of the three independent tests.

2.4 Diffusion isotherm measurements

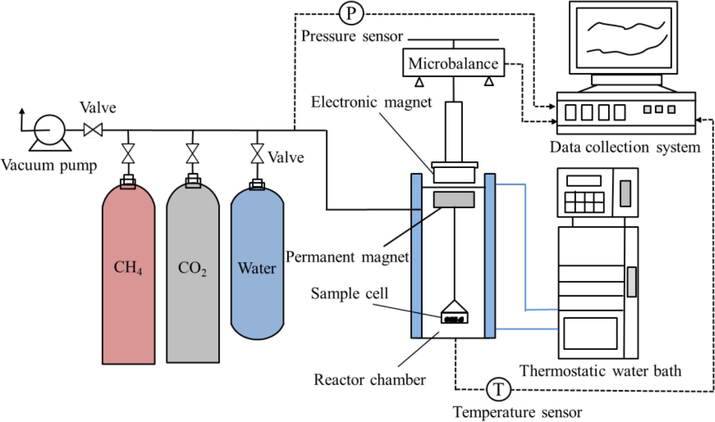

An Intelligent Gravimetric Analyzer (IGA, Hiden Analytical, UK) was used to measure the diffusion isotherms of CH4, CO2 and water vapor in the coal samples both before and after ScCO2 exposure. As shown in Fig. 2, the IGA system is characterized by a fully computerized high-resolution (±0.1 μg) microbalance, which can detect the sample weight as a function of time with pressure and temperature under computer control. For diffusion isotherm measurements, the coal sample (∼200 mg) was placed in a thermostatic reactor chamber with accurate temperature control (±0.1 ℃).

Schematic diagram of IGA system.

Prior to each measurement, the sample was first degassed under a vacuum level of ∼ 10−4 Pa at 105 ℃ for 3 h, then cooled to the operating temperature (40 ℃) by placing the reactor in a thermostatic water bath. The diffusion isotherms of CH4 and CO2 were measured under 1 MPa, while the operates of water vapor were performed under 6.6 kPa (∼90 % of the saturation pressure, p/p0 = 0.9). The increase in weight due to adsorption was continuously monitored and recorded, which was then applied to calculate the parameters of diffusion and adsorption kinetics with appropriate models.

3 Modeling approach

3.1 Mechanisms of diffusion

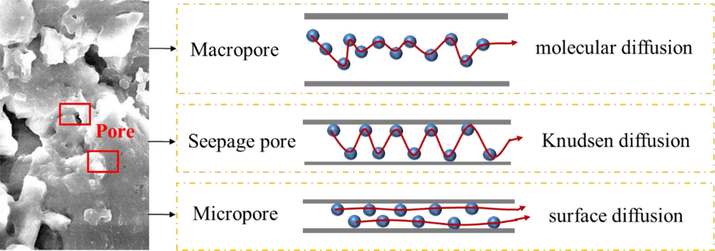

Gas diffusion in a porous medium can be categorized as interaction of gas molecules and collisions of gas molecules with the solid surface (Naveen et al., 2017). Accordingly, diffusion is controlled by characteristics of gas species as well as intrinsic morphology of the porous media. The diffusion process can be distinguished by three mechanisms, i.e., molecular diffusion, Knudsen diffusion and surface diffusion. As the pressure is high or the free path of gas molecules is smaller than the pore width, molecular diffusion prevails because the collision between gas molecules is larger than the interaction between gas molecules and pore surface. As the pressure is very low or the mean free path of gas molecules is larger than pore width, collision between gas molecules and pore surface dominates, and gas flow is controlled by Knudsen diffusion. Surface diffusion dominates in micropores with large sorption potential, as the adsorbed molecules migrate along the pore surface (Chua et al., 2015). Overall, the diffusion of CH4, CO2 and water vapor in the coal is a mixture of gas-phase and adsorbed-phase diffusion, as schematically depicted in Fig. 3.

Mechanisms of CH4, CO2 and water vapor diffusion in the coal.

3.2 Model of diffusion

In order to interpret and quantify the gas diffusion in a porous media, several numerical models have been developed by researchers (Bruch and Gensterblum, 2011). The application of unipore model for representing the gas transient data has been confirmed in a number of studies (Clarkson and Bustin, 1999; Pillalamarry et al., 2011). The unipore model is derived from the solution to Fick’s second law for spherical symmetric flow:

with the initial condition:

C = 0 at t = 0.

where D is diffusion coefficient, r is sphere radius, C is adsorbate concentration, and t is the time. This form of the equation assumes isothermal conditions, homogenous pore structure. Moreover, diffusivity is irrelevant with the location and concentration of coal particle.

The solution to Eq. (1) for a fixed surface concentration of the adsorbent can be transmitted as follows:

where Vt is the uptake amount of adsorbent at time t, V∞ is total amount of gas uptake, and rp is the path length of diffusion.

For Vt/V∞ < 50 %, Eq. (2) is approximated as:

where De (D/rp2) is effective diffusivity. Thus, the effective diffusivity De and diffusion coefficient D are calculated through linear fitting of Vt/V∞ vs t1/2.

3.3 Model of adsorption kinetics

The pseudo-first-order equation has also been widely employed when describing adsorption kinetics in terms of non-equilibrium status (Du et al., 2019). The pseudo-first-order equation is written as follows:

with boundary conditions:

where Qt is the uptake amount at time t, Qe is the uptake amount at equilibrium state, and k1 is adsorption rate constant.

Eq. (4) can be integrated as follows:

The adsorption rate (k1) is calculated by linear fitting of ln (Qe—Qt) vs time t.

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Effects of ScCO2 exposure on CH4 and CO2 diffusion and adsorption kinetics

4.1.1 Diffusion isotherms of CH4 and CO2

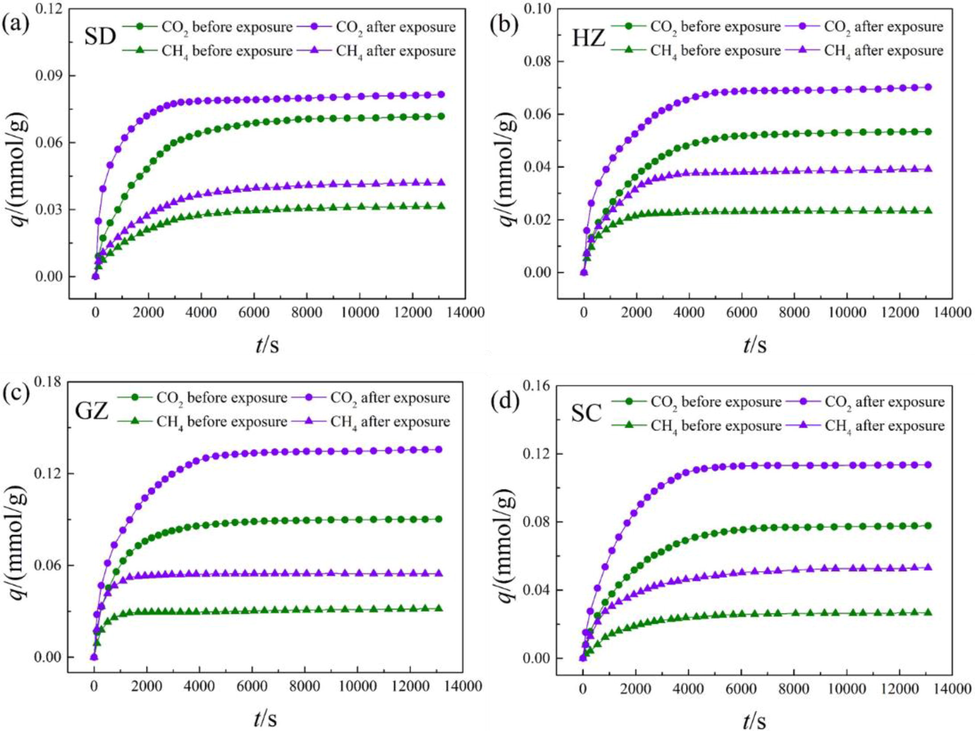

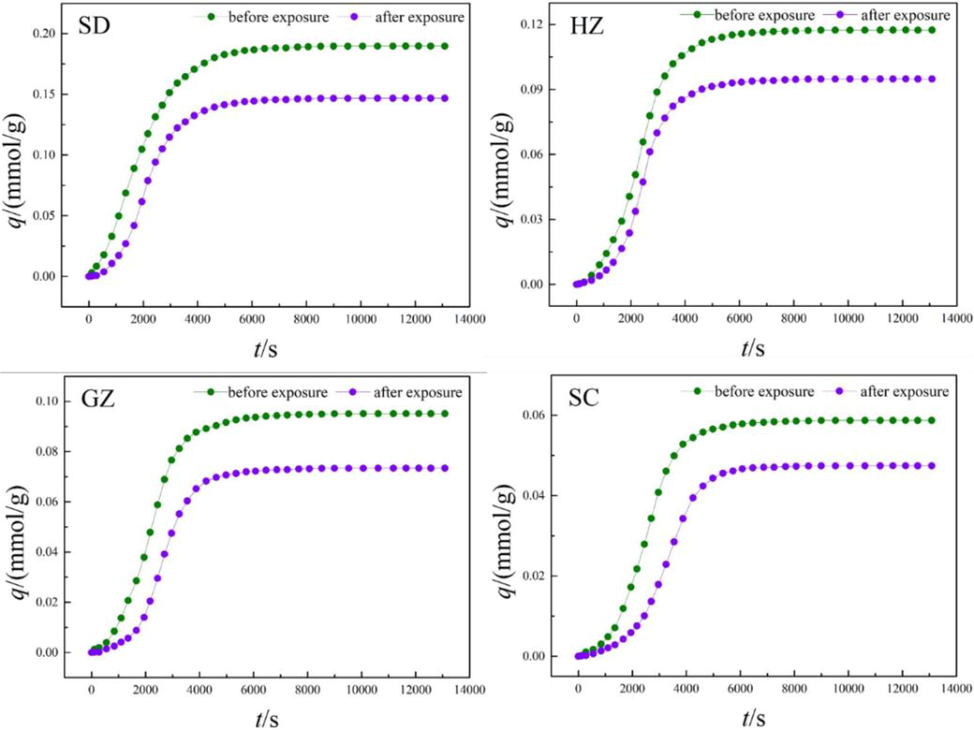

The diffusion isotherms of CH4 and CO2 in the coal samples both before and after ScCO2 exposure are shown in Fig. 4. Obviously, the overall trend of the isotherms exhibited by all cases are very similar. The isotherms can be divided into two stages, namely, an initial rapid diffusion stage and a slow diffusion stage. This is in coincidence with existing studies, including Clarkson and Bustin (1999), Pillalamarry et al. (2011), and Yang et al. (2016). The distinct behaviors of CO2 and CH4 diffusion is derived from the combined effect of multiple factors. At the early stage, the differences of concentration between inner pore space and coal surface are significant, providing strong driving forces for gas molecules to diffuse. As time goes by, the differences of concentration gradually reduce and the repulsive forces between the molecules in adsorbed and bulk phases are enhanced (Cui et al., 2004). In addition, coal matrix swelling induced by adsorption may also be one of the major factors. As stated by Pluymakers et al. (2018), coal matrix swelling will narrow the pore throats, resulting in higher transition resistances for CH4 and CO2.

Diffusion isotherms of CH4 and CO2 before and after ScCO2 exposure.

As depicted in Fig. 4, the equilibrium adsorption capacities of CO2 are larger than CH4 in all the coal samples. This result is ascribed to the distinct physical and chemical properties of CH4 and CO2. Firstly, the kinetic diameter of CO2 molecule is smaller than CH4, enabling CO2 molecules to penetrate into smaller pores (Kelemen and Kwiatek, 2009). Secondly, the critical temperature of CO2 is significantly higher than CH4, leading to higher binding forces between CO2 molecules and coal matrix (Dutta, et al., 2011). Moreover, the solubility of CO2 in coal matrix is higher than CH4, which can also lead to higher uptake capability of CO2 (Zhang et al., 2011).

After ScCO2 exposure, the diffusion of either CH4 or CO2 is ameliorated significantly. This result means the accessibility of both CH4 and CO2 molecules is enhanced with ScCO2 exposure, which can be interpreted as a consequence of the alterations of physico-chemical properties in the coals. Hol et al. (2012) found that microfractures were formed in the coal during ScCO2 exposure under unconfined conditions. They inferred from the microstructural and mechanical data that micro-fracturing will allow more homogeneous access of CO2, leading to the swelling of coal matrix not previously accessed by CO2. This will largely enhance the pore connectivity due to the transition of closed pores into adsorption pores in this process. On the other hand, the solvent effect caused by ScCO2 exposure may remove some volatile matters that may block the pore throats, thus widen the pathways for CH4 and CO2 molecules to diffuse (Gathitu et al., 2009). Based on Fourier Transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis, Wang et al. (2015) found that the density of oxygen-containing functional groups was significantly reduced for different rank of coals after ScCO2 exposure. They attributed this result to the extracting ability or reactivity of ScCO2 fluid. Similarly, Liu et al. (2019) found that the overall density of surface functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl and carbonyl) were significantly decreased after ScCO2 exposure. However, Mastalerz et al. (2010) found no differences in functional groups distribution between the coals before and after ScCO2 exposure. Also, Mavhengere et al. (2015) detected no significant changes in surface functional group distribution after exposed to both sub- and super-critical CO2. This division may be result from the variation in test conditions for different studies, including pressure, temperature and reaction time. It is concluded that the pore connectivity enhancing with ScCO2 exposure may be the major cause of the increase in accessibility of CH4 and CO2 molecules, while only minor or no changes of surface chemistry was reported in the previous studies.

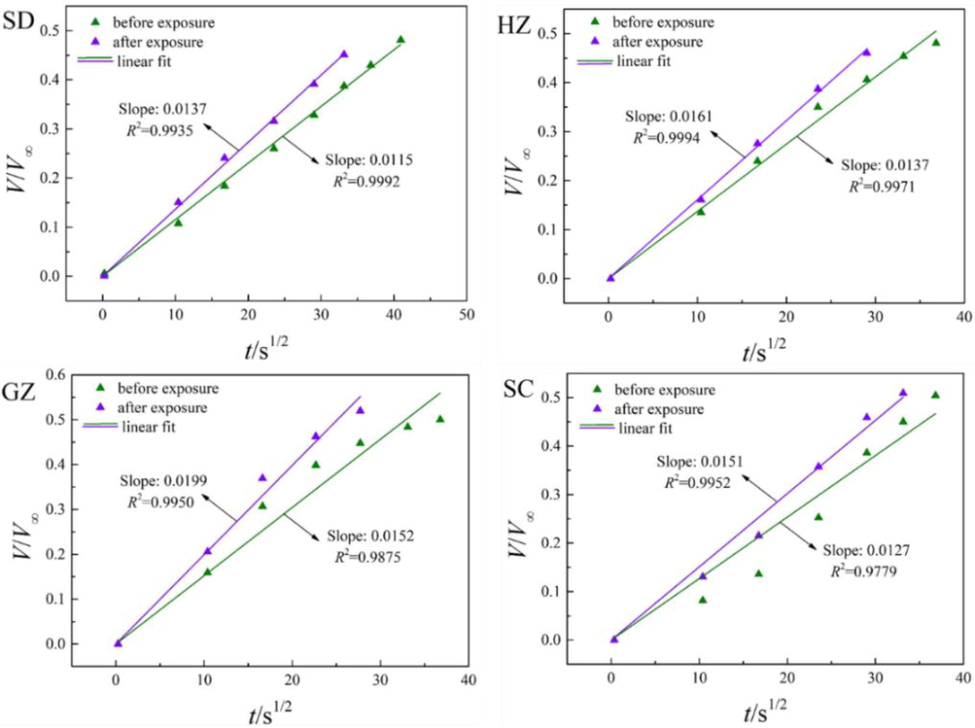

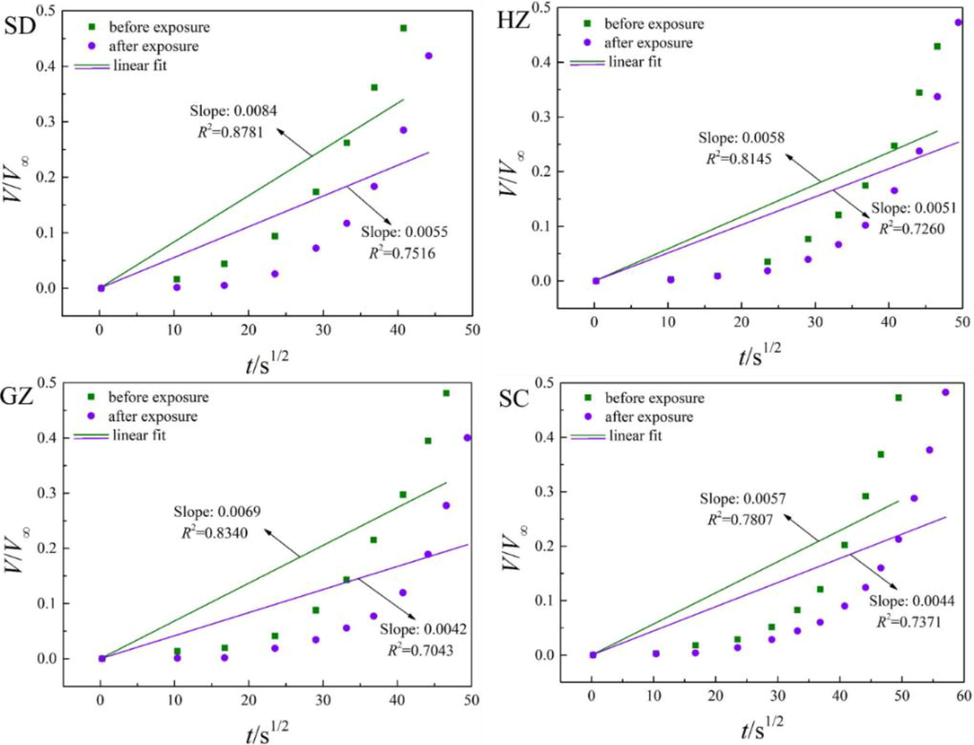

4.1.2 Diffusivities of CH4 and CO2 determined by unipore model

The fitting results of CH4 and CO2 diffusion in the coal samples both before and after ScCO2 exposure by unipore model (Eq. (3)) are depicted in Fig. 5 and Fig. 6, respectively. As can be seen in the figures, diffusion of either CH4 or CO2 can be well described by unipore model with the regression coefficients (R2) >0.97 for all cases. Therefore, it is responsible to suppose that unipore model provides good insights into the diffusion of CH4 and CO2 in powdered coals. After ScCO2 exposure, the slopes of the lines of either CH4 or CO2 are larger than the initial state, indicating that ScCO2 injection will effectively promote CH4 and CO2 molecules to move rapidly in the matrix and hence improve gas diffusivity. As mentioned above, this result may be originated from the combined influences of matrix micro-fracturing and solvent effects with ScCO2 exposure (Liu et al., 2018).

Fitting results of CH4 diffusion using unipore model.

Fitting results of CO2 diffusion using unipore model.

The results of the analytical model fit to the effective diffusivity (De) and diffusion coefficient (D) are listed in Table 2. Here, the order of magnitude of De and D for both CH4 and CO2 are 10-5 s−1 and 10-11 m2/s, respectively. Similar results have been reported in many previous studies (Bruch and Gensterblum, 2011). For example, in a study by Clarkson and Bustin (1999), a similar D of CH4 and CO2 was calculated by unipore model for constant pressure adsorption. They also found that the diffusivity of CO2 was significantly larger than CH4 in Cretaceous Gates Formation coal. However, the obtained diffusivities of CH4 and CO2 are similar in this study. It is because that diffusivity is influenced by multiple factors (e.g., coal rank, grain size, temperature and pressure), resulting in distinct results under each independent tests. In the future, significant efforts are still required to identify the effects of the above-mentioned factors on gas diffusion, in particular for the attachment of connection between a certain factor with diffusivity.

Sample

State

CH4

CO2

De

(10-5s−1)

D

(10-11m2/s)

Change

(%)

De

(10-5s−1)

D

(10-11m2/s)

Change

(%)

SD

before exposure

1.15

5.47

42.61

1.54

7.32

59.14

after exposure

1.64

7.79

2.46

11.69

HZ

before exposure

1.62

7.70

39.51

1.34

6.37

52.24

after exposure

2.26

10.74

2.04

9.69

GZ

before exposure

2.02

9.60

71.28

1.76

8.36

37.50

after exposure

3.46

16.44

1.28

6.08

SC

before exposure

1.41

6.70

41.13

0.94

4.47

42.16

after exposure

1.99

9.46

1.34

6.37

According to Table 2, the De and D of both CH4 and CO2 are significantly increased after ScCO2 exposure. The highest increase of CH4 is observed in GZ coal, intermediate in SD coal and SC coal, and lowest in HZ coal, corresponding to 71.28 %, 42.16 %, 41.13 % and 39.15 %, respectively. The value of CO2 is largest for SD coal, followed by HZ coal, SC coal and GZ coal in sequence, corresponding to 59.14 %, 52.24 %, 42.16 % and 37.50 %, respectively. Evidently, ScCO2 exposure enables the CH4 and CO2 molecules to diffuse more rapidly. This suggests that the injection of ScCO2 will efficiently accelerate the transportation of CH4 and CO2, facilitating the CO2 injectivity and CH4 recovery. In addition, the increase rates of De and D for CH4 and CO2 differ significantly among different rank coals, both of which exhibit downward trend with the increasing coal rank. It is noted that the effects of ScCO2 exposure on lower-ranked coals are much more remarkable than higher-ranked coals. This is because coalification is a compressive process that can intensify the polycondensation of coal molecules, which may reduce its reactivity when exposed to ScCO2 (Li et al., 2021).

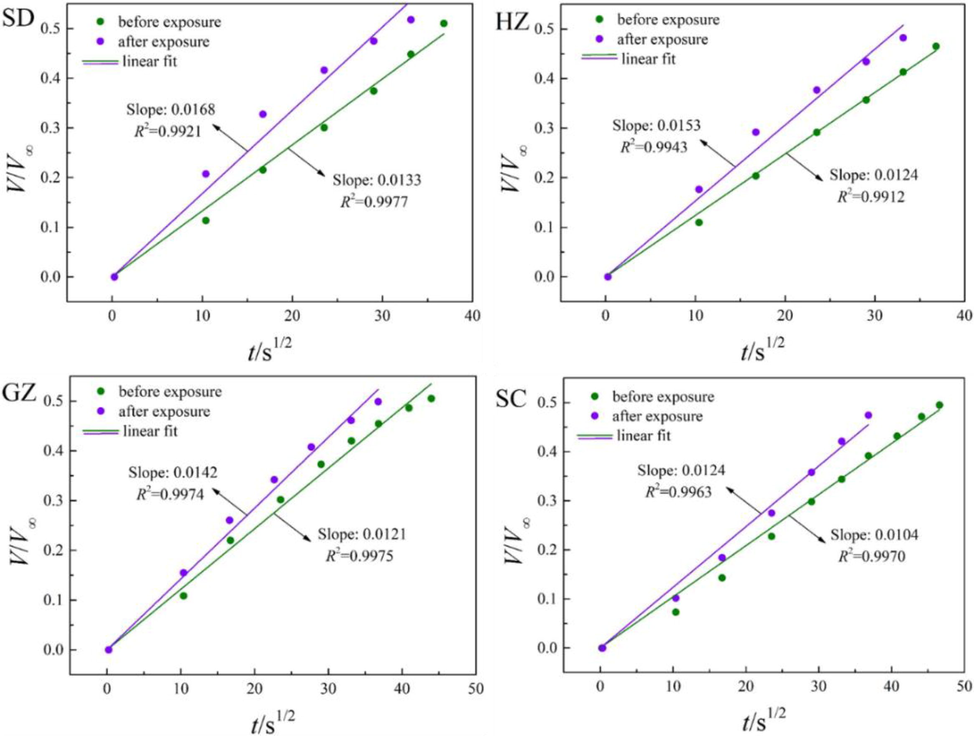

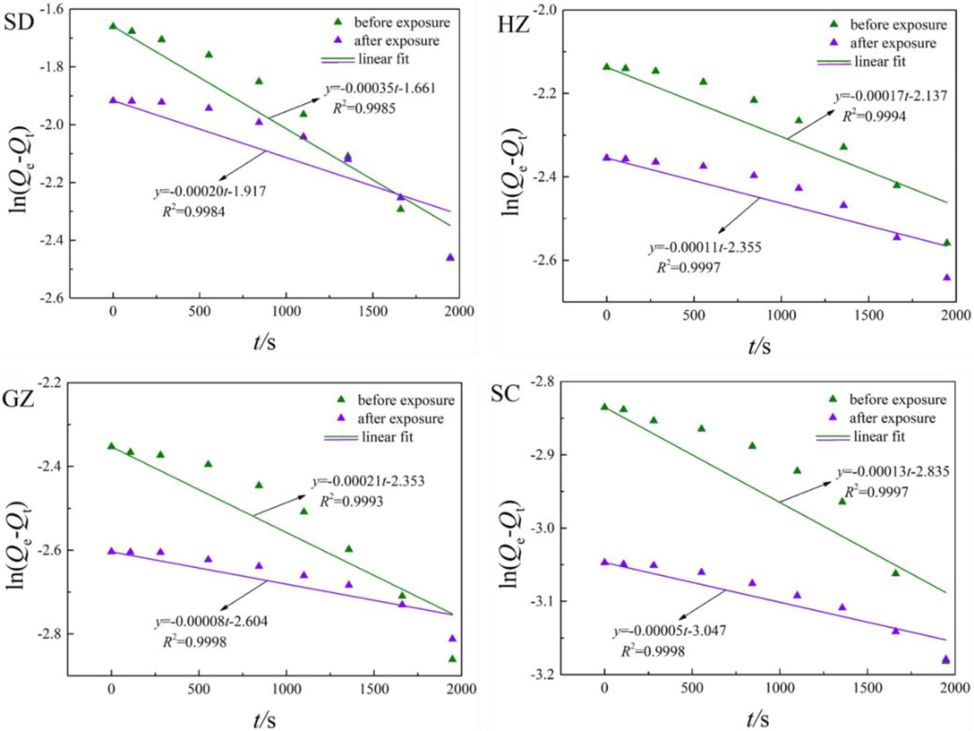

4.1.3 Adsorption kinetics of CH4 and CO2 determined by Pseudo-first-order equation

Fig. 7 and Fig. 8 display the fitting results of adsorption kinetics data of CH4 and CO2 in the coal samples before and after ScCO2 exposure by pseudo-first-order equation (Eq. (7)). It can be observed that the values of R2 are exceeded 0.99, and the calculated values are in coincidence with the experimental data for all cases. Therefore, the pseudo-first-order equation is feasible for representing the adsorption kinetics of CH4 and CO2.

Fitting results of CH4 adsorption kinetics using pseudo-first-order equation.

Fitting results of CO2 adsorption kinetics using pseudo-first-order equation.

As depicted in Fig. 7 and Fig. 8, the intercepts of the lines are increased notably after ScCO2 exposure, suggesting that the equilibrium adsorption capacities of CH4 and CO2 are increased with ScCO2 injection. On the other hand, the slopes of the lines are slightly reduced, indicating that the adsorption kinetics of CH4 and CO2 are accelerated after ScCO2 injection. These results indicate that both the adsorption capacities and kinetics of CH4 and CO2 can be facilitated with ScCO2 injection. However, our previous study (Liu et al., 2019) found a decreased monolayer capacity of CO2 due to the combined effects of surface property and pore structure alterations caused by ScCO2 exposure. It is noted that the operating pressure for adsorption kinetic experiments in this study (p = 1 MPa), which is much smaller than the saturation pressures (p0 > 5 MPa). In this case, ScCO2 exposure is beneficial to gas diffusion under low pressures, and further studies are needed to evaluate the its effect on high-pressure gas diffusion.

The determined adsorption rates (k1) by pseudo-first-order equation are summarized in Table 3. As can be seen, the order of magnitude of k1 of both CH4 and CO2 are 10-4 s−1. Similar to De and D, the values of k1 also increased notably after ScCO2 exposure. The k1 of CH4 increased by 8.35 % to 24.95 %, while the values of CO2 increased by 10.92 % to 30.05 %, indicating that the adsorption kinetics of CH4 and CO2 on various rank coals are significantly promoted with ScCO2 injection.

Sample

CH4 adsorption rate k1 (10-4 s−1)

CO2 adsorption rate k1 (10-4s−1)

Before exposure

After exposure

Change

(%)

Before exposure

After exposure

Change

(%)

SD

4.07

4.41

8.35

5.13

5.69

10.92

HZ

5.01

5.50

9.78

4.54

5.27

16.08

GZ

4.81

6.01

24.95

4.27

5.07

18.74

SC

4.93

5.69

15.42

3.56

4.63

30.05

Combining the results presented in Table 2 and Table 3, it is deduced that the effects of ScCO2 exposure on diffusion and adsorption kinetics of either CH4 or CO2 is identical in different rank coals, although the quantitative relationship can hardly be established. This is attributed to the differences in physical and chemical nature among the coals, resulting in variations of ScCO2-coal reaction mechanism. Firstly, the adsorption-induced swelling differs significantly among various rank coals. Walker et al. (1988) found that matrix swelling was enhanced with the increasing coal rank from lignite (C ≤ 70 %) to high volatile bituminous coal (70 %<C ≤ 90 %), and it then decreased up to anthracite (C > 90 %). Secondly, the extent of the solvent effect is largely depended on coal rank. As reported by Zhang et al. (2013), the amount and type of hydrocarbons extracted by ScCO2 is a function of volatile matter. In our previous study (Liu et al., 2019), it was also found that the physico-chemical properties of the coals were altered notably with ScCO2 exposure, irrespective of rank. To better gauge the influences of ScCO2 injection, further studies are still needed to quantify the relations of matrix swelling and solvent effect on diffusion of gases in various rank coals.

4.2 Effects of ScCO2 exposure on water vapor diffusion

4.2.1 Diffusion isotherm of water vapor

Fig. 9 shows the diffusion isotherms of water vapor in the coal samples both before and after ScCO2 exposure. As can be seen, the overall trend is quite similar among the isotherms. Each of the isotherm can be divided into several sections. At first, water molecules formed hydrogen bonds with surface functional groups, which is shown as a slow increase in diffusivity. The diffusion of water vapor in this process is significantly different from CH4 and CO2. As confirmed by Švábová (2011), this is due to the relatively weak carbon–water interaction. With increasing time, the diffusion continues until all the surface functional groups are occupied by water molecules. As the time increase further, water molecules adsorb on top of the previously adsorbed water molecules and form clusters, which is reflected by a rapid increase in water diffusivity. Finally, water clusters grown into larger clusters and continuous pore filling occurred until adsorption equilibrium achieved.

Diffusion isotherms of water vapor in the coals before and after ScCO2 exposure.

As shown in Fig. 9, the density of surface functional groups decreases with the increasing coal rank, leading to higher uptake capacity of water vapor in lower rank coal. In this respect, the density of surface function groups may probably be the key factor for water vapor diffusion, although pore properties have been proved to be another influential factor of water vapor diffusion (Charrière and Behra, 2010). In comparation, the diffusivity of water vapor in different rank coals are decreased significantly after ScCO2 exposure. This is due to that some organic matters are dissolved by ScCO2, reducing the number and overall density of surface functional groups in coal matrix, which can act as primary adsorption sites for water vapor (Li et al., 2017).

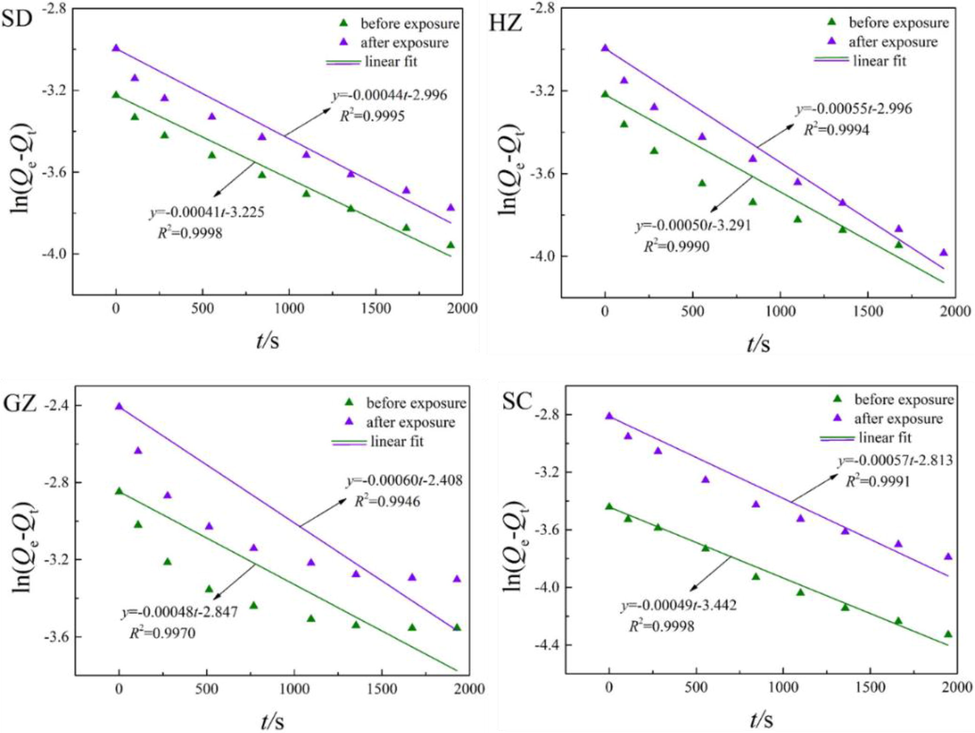

4.2.2 Diffusivities of water vapor

The diffusion of water vapor in the coal samples before and after ScCO2 exposure were fitted by the unipore model and the results are depicted in Fig. 10. According to the figure, the unipore model does not fit the experimental data as well as CH4 and CO2 with the values of R2 all smaller than 0.9. Thereby, the unipore model is not capable of well describing water vapor diffusion in the coals. This may possibly because the diffusion of water vapor is mainly derived from carbon-water interaction at the initial stage, which does not follow the Fick’s second law with the usual assumption of fluids equilibrium concentration at the surface. Therefore, efforts are still needed to strive for a new model which can distinguish the interaction between carbon–water and water-water, especially at the initial stage of water vapor adsorption. Nonetheless, the unipore model can reflect the overall trend of water vapor diffusion. It is observed that the slopes of the lines are uniformly decreased after ScCO2 exposure, indicating that the diffusivities of water vapor are reduced during this process.

Fitting results of water vapor diffusion using the unipore model.

The obtained effective diffusivity De (D/rp2) and diffusion coefficient (D) of water vapor in the coals before and after ScCO2 exposure are listed in Table 4. As shown in the Table 4, the De and D of water vapor diffusion in SD coal are the largest, followed by GZ coal, HZ coal, and SC coal in sequence. Although the uptake capacity of water vapor decreases with the increasing coal rank (Fig. 9), the diffusivities do not show any distinct correlation with coal rank. Combining the results of Table 2 and Table 4, it is concluded that both De and D of water vapor are in a smaller order of magnitude than CH4 or CO2. This is due to that the concentrations of CH4 and CO2 are much higher than water vapor for the tests, which is one of the key factors for CH4 and CO2 molecules to diffuse. In addition, Prinz and Littke (2005) have shown that water molecules cannot penetrate the interlayer spacing of crystallite structures (<0.4 nm). Instead, water is present in the mesopores and larger micropores (∼0.4–30 nm). This may be another reason for the lower diffusivity of water vapor than CH4 and CO2.

Sample

State

De

(10-6s−1)

D

(10-12m2/s)

Rate

(%)

SD

before exposure

6.15

2.92

−57.07

after exposure

2.64

1.26

HZ

before exposure

2.99

1.42

−24.75

after exposure

2.25

1.07

GZ

before exposure

4.15

1.98

−62.89

after exposure

1.54

0.73

SC

before exposure

2.83

1.35

−47.46

after exposure

1.77

0.84

As depicted in Table 4, the values of De and D are significantly reduced after ScCO2 exposure. The lowest reduction rate is observed in HZ coal, intermediate in SD coal and SC coal, and highest for GZ coal, corresponding to −24.75 %, −47.46 %, −57.07 % and −62.89 %, respectively. It is reasonable to assume that ScCO2 exposure may hinder water molecules rapidly diffuse in the coal matrix. This is because ScCO2 is able to remove some surface functional, which have been shown to be the primary sorption centers for water molecules (Han et al., 2019).

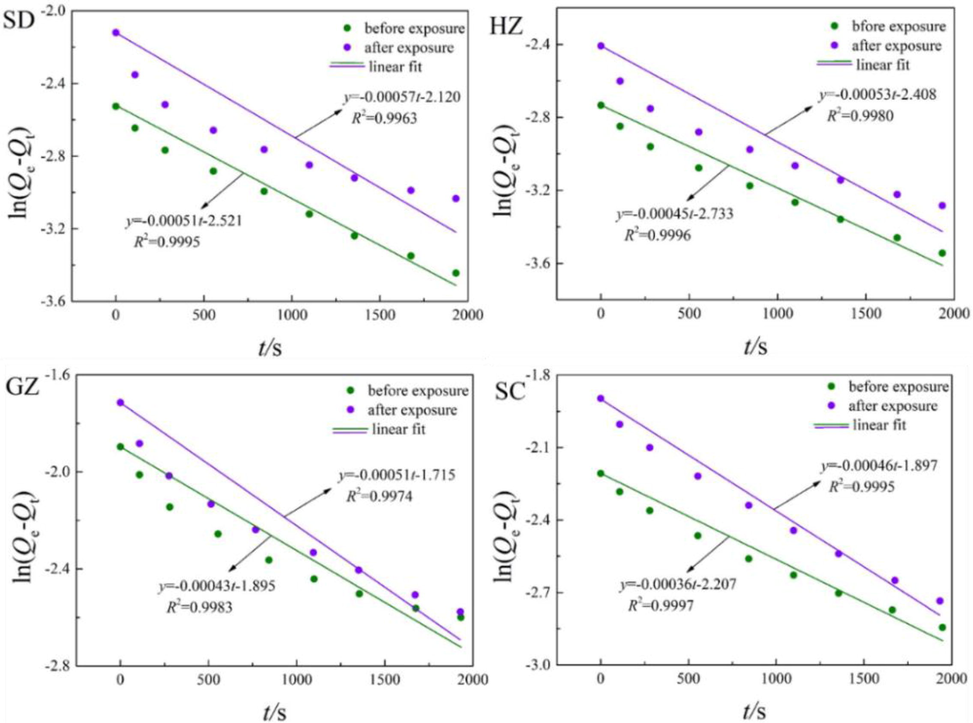

4.2.3 Adsorption kinetics of water vapor

Fig. 11 illustrates the fitting results of water vapor diffusion in the coals before and after ScCO2 exposure using pseudo-first-order equation. As shown in the figure, the pseudo-first-order equation fitted the experimental data very well with the values of R2 exceeded 0.99 in all cases. In comparation, the fitting results by pseudo-first-order equation is much better than the unipore model. This may probably be derived from basic assumption of pseudo-first-order equation, supposing that there is only one binding site on solid surface. Simultaneously, the interaction between water molecules and surface functional groups is chemical adsorption at a lower surface coverage, which is characterized by one water molecule adsorption on per surface functional group. In this respect, water vapor diffusion is in well agreement with the assumption of pseudo-first-order equation.

Fitting of water vapor adsorption kinetics using pseudo-first-order equation.

Unlike CH4 and CO2, the intercepts of the lines were decreased after ScCO2 exposure, indicating that the uptake capacities of water vapor in the coals are increased with ScCO2 exposure. On the contrary, the slopes of the lines are increased after ScCO2 exposure, indicating that the adsorption kinetics of water vapor are restricted in this process. As discussed above, this is probably due to the elimination of surface functional groups with ScCO2 exposure, which will weaken the adsorption potential of water molecules on coal surface.

The obtained adsorption rates (k1) of water vapor in the coal samples both before and after ScCO2 exposure are summarized in Table 5. As depicted in Table 5, the order of magnitude of k1 of water vapor in the coal samples are 10-4 s−1. This is similar with CH4 and CO2, although the values of water vapor were smaller. The k1 of water vapor in SD coal is the largest, moderate in HZ coal and GZ coal, and the smallest in SC coal. It can be deduced that k1 exhibits a downward trend with the increasing coal rank. The values of k1 decline significantly after ScCO2 exposure. The decrease rate of GZ coal is the largest (-62.43 %), followed by SC coal (-58.46 %), SD coal (-43.79 %) and HZ coal (–33.93 %) in sequence. Thus, the varieties of adsorption kinetics -are extremely significant with ScCO2 exposure but can hardly find any correlation with coal rank. The adsorption kinetics of water vapor is affected by both the surface chemistry and the pore structure of coal, which differ significantly among different rank coals, making it hard to evaluate the correlation between the variations in adsorption kinetics of water vapor and ScCO2 exposure.

Sample

Water vapor adsorption rate k1 (10-4 s−1)

Before exposure

After exposure

Rate (%)

SD

3.54

1.99

−43.79

HZ

1.68

1.11

–33.93

GZ

2.05

0.77

−62.43

SC

1.30

0.54

−58.46

4.3 Implications for enhanced CBM recovery and CO2 sequestration

Although ScCO2 exposure facilitated the diffusion of CH4 and CO2 by combined effects of coal micro-fracturing and solvent effects, the diffusivity and adsorption rate of water vapor are significantly decreased in different rank coals. Based on these results, it is deduced that the injection of ScCO2 will efficiently improve the transport properties of CH4 and CO2 but hinder water molecule movements in the coal seam. In this respect, ScCO2 exposure may be beneficial to CO2 injection and CH4 recovery.

It should be noted that the coal particles examined in this study were unconfined and measurements were made under ScCO2 exposure rather than at in-situ condition. In the coal seams suitable for CO2-ECBM, with the influence of the seam water and confining pressure, the effects may possibly be aggravated (Karacan, 2003; Pone et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2019). In addition, it should be pointed out that the measured properties of pressure in this study (1 MPa) is much lower than the actual conditions in coal seams (16 MPa). This will cause some inaccuracy with respect to the real conditions of the target sites for CO2 sequestration. Therefore, the field-scale reservoir tests are still needed under confined conditions and higher measured properties of pressure (up to 10 MPa) to elucidate more fully the response of coal seams to CO2 sequestration and better gauge the viability of CO2-ECBM.

5 Conclusions

The alterations of CH4, CO2 and water vapor diffusion with ScCO2 exposure were studied using different rank coals. The following conclusions can be drawn:

The diffusivities of CH4 and CO2 are significantly increased due to the combined matrix swelling and solvent effect caused by ScCO2 exposure, which may induce secondary faults and remove some volatile matters that block the pore throats.

The diffusivities of water vapor are reduced due to the elimination of surface functional groups with ScCO2 exposure. It is concluded that density of the functional groups on coal surface is a controlling factor for water vapor diffusion, although the pore properties of coal may be another influential factor.

The unipore model and pseudo-first-order equation can simulate the diffusion and adsorption kinetics of CH4 and CO2 well, but the unipore model is not capable of well describing water vapor diffusion. The De, D and k1 of CH4 and CO2 are significantly increased after ScCO2 exposure, while the values of water vapor are notably decreased.

The injection of ScCO2 will efficiently improve the transport properties of CH4 and CO2 but hinder water molecule movements in coal seams. These effects may be aggravated at in-situ condition.

Data availability

The data applied to support the results in this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

This study is financially supported by the Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 2020 M673152), Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects (Grant No. 202101BE070001-039), Yunnan Provincial Department of Education Science Research Fund Project (Grant No. 2022J0055) and Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (Qianke Foundation [2019] 1426).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- CBM and CO2-ECBM related sorption processes in coal: a review. Int. J. Coal Geol.. 2011;87:49-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of chemical functional groups in macerals across different coal ranks via micro-FTIR spectroscopy. Int. J. Coal Geol.. 2012;104:22-33.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanoporous organosilica membrane for water desalination: theoretical study on the water transport. J. Membrane. Sci.. 2015;482:56-66.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of pore structure and gas pressure upon the transport properties of coal: a laboratory and modeling study. 2. adsorption rate modeling. Fuel. 1999;78:1345-1362.

- [Google Scholar]

- Selective transport of CO2, CH4 and N2 in coals: insights from modeling of experimental gas adsorption data. Fuel. 2004;83:293-303.

- [Google Scholar]

- Swelling of Australian coals in supercritical CO2. Int. J. Coal Geol.. 2008;74:41-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of chromium (VI) and iron (III) ions onto acid-modified kaolinite: Isotherm, kinetics and thermodynamics studies. Arab. J. Chem.. 2021;14(4):103064

- [Google Scholar]

- CO2 and CH4 adsorption on different rank coals: A thermodynamics study of surface potential, Gibbs free energy change and entropy loss. Fuel. 2021;283:118886

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental study on the kinetics of adsorption of CO2 and CH4 in gas-bearing shale reservoirs. Energ. Fuel. 2019;33:12587-12600.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation into the adsorption of CO2, N2 and CH4 on kaolinite clay. Arab. J. Chem.. 2022;15(3):103665

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation into adsorption equilibrium and thermodynamics for water vapor on montmorillonite clay. AIChE Journal. 2022;68(3):e17550

- [Google Scholar]

- Methane and carbon dioxide sorption on a set of coals from india. Int. J. Coal Geol.. 2011;85:289-299.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of coal interaction with supercritical CO2: physical structure. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2009;48:5024-5034.

- [Google Scholar]

- Argonne coal structure rearrangement caused by sorption of CO2. Energ. Fuel. 2006;20:2537-2543.

- [Google Scholar]

- Insight into the interaction between hydrogen bonds in brown coal and water. Fuel. 2019;236:1334-1344.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microfracturing of coal due to interaction with CO2 under unconfined conditions. Fuel. 2012;97:569-584.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of the influence of coal swelling on permeability characteristics using natural brown coal and reconstituted brown coal specimens. Energy. 2012;39:303-309.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heterogeneous sorption and swelling in a confined and stressed coal during CO2 injection. Energ. Fuel. 2003;17:1595-1608.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physical properties of selected block Argonne premium bituminous coal related to CO2, CH4, and N2 adsorption. Int. J. Coal Geol.. 2009;77:2-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of coal before and after supercritical CO2 exposure via feature relocation using field-emission scanning electron microscopy. Fuel. 2013;107:777-786.

- [Google Scholar]

- Upgrading effects of supercritical carbon dioxide extraction on physicochemical characteristics of Chinese low-rank coals. Energ. Fuel. 2017;31:13305-13316.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanopore structure of different rank coals and its quantitative characterization. J. Nanosci. Nanotechno.. 2021;21(1):22-42.

- [Google Scholar]

- Simulation of adsorption-desorption behavior in coal seam gas reservoirs at the molecular level: a comprehensive review. Energ. Fuel. 2020;34:2619-2642.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of supercritical CO2 on mesopore and macropore structure in bituminous and anthracite coal. Fuel. 2018;223:32-43.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surface properties and pore structure of anthracite, bituminous coal and lignite. Energies. 2018;11:1502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supercritical CO2 exposure-induced surface property, pore structure, and adsorption capacity alterations in various rank coals. Energies. 2019;12:3294.

- [Google Scholar]

- Coal lithotypes before and after saturation with CO2, insights from micro- and mesoporosity, fluidity, and functional group distribution. Int. J. Coal Geol.. 2010;83(4):467-474.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physical and structural effects of carbon dioxide storage on vitrinite-rich coal particles under subcritical and supercritical conditions. Int. J. Coal Geol.. 2015;150–151:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sorption kinetics of CH4 and CO2 diffusion in coal: theoretical and experimental study. Energ. Fuel. 2017;31:6825-6837.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparing the porosity and surface areas of coal as measured by gas adsorption, mercury intrusion and SAXS techniques. Fuel. 2015;141:293-304.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influences of CO2 injection into deep coal seams: A review. Energ. Fuel. 2017;31(10):10324-10334.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive overview of CO2 flow behaviour in deep coal seams. Energies. 2018;11:906.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gas diffusion behavior of coal and its impact on production from coalbed methane reservoirs. Int. J. Coal Geol.. 2011;86:342-348.

- [Google Scholar]

- A high resolution interferometric method to measure local swelling due to CO2 exposure in coal and shale. Int. J. Coal Geol.. 2018;187:131-142.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sorption capacity and sorption kinetic measurements of CO2 and CH4 in confined and unconfined bituminous coal. Energ. Fuel. 2009;23:4688-4695.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of the micro- and ultramicroporous structure of coals with rank as deduced from the accessibility to water. Fuel. 2005;84(12/13):1645-1652.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modeling water adsorption in carbon micropores: Study of water in carbon molecular sieves. Langmuir. 2006;22:702-728.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combined influence of pore size distribution and surface hydrophilicity on the water adsorption characteristics of micro- and mesoporous silica. Micropor. Mesopor. Mat.. 2016;226:221-228.

- [Google Scholar]

- Švábová, M., Weishauptová, Z., P rˇibyl, O., 2011. Water vapour adsorption on coal. Fuel 90(5), 1892–1899.

- Experimental study of impact of anisotropy and heterogeneity on gas flow in coal. part I: diffusion and adsorption. Fuel. 2018;232:444-453.

- [Google Scholar]

- A laboratory investigation of permeability of coal to supercritical CO2. Geotech. Geol. Eng.. 2015;33:1009-1016.

- [Google Scholar]

- A direct measurement of expansion in coals and macerals induced by carbon dioxide and methanol. Fuel. 1988;67(5):719-726.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of CO2 exposure on high-pressure methane and CO2 adsorption on various rank coals: implications for CO2 sequestration in coal seams. Energ. Fuel. 2015;29:3785-3795.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sequestration of carbon dioxide in coal with enhanced coalbed methane recovery—a review. Energ. Fuel. 2005;19:659-724.

- [Google Scholar]

- A model of dynamic adsorption-diffusion for modeling gas transport and storage in shale. Fuel. 2016;173:115-128.

- [Google Scholar]

- Supercritical pure methane and CO2 adsorption on various rank coals of China: Experiments and modeling. Energ. Fuel. 2011;25:1891-1899.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental investigation of the influence of CO2 and water adsorption on mechanics of coal under confining pressure. Int. J. Coal Geol.. 2019;209:117-129.

- [Google Scholar]

- A comparative evaluation of coal specific surface area by CO2 and N2 adsorption and its influence on CH4 adsorption capacity at different pore sizes. Fuel. 2016;183:420-431.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular simulation of CO2/CH4/H2O competitive adsorption and diffusion in brown coal. RSC Adv.. 2019;9:3004-3011.

- [Google Scholar]