Translate this page into:

Green sol–gel auto-combustion synthesis, characterization and study of cytotoxicity and anticancer activity of ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite

⁎Corresponding author. salavati@kashanu.ac.ir (Masoud Salavati-Niasari)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Due to the fact that researchers and scientists have been interested in environmentally friendly synthesis using plant extracts because of the wide distribution of plants, their ease of availability, and their safety in use, in the current work, ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite was produced using a green chemistry method via sucrose indicating the importance of both an active capping and reducing agent for the synthesis of nanocomposite materials with well-organized biological properties. Number of methods, including TEM, SEM, XRD, BET-BJH, VSM, and HRTEM, were used to characterize the produced nanocomposite. The XRD data showed that the produced nanocomposite had pure particles with a range of 37 ± 2 nm in size, which was validated by TEM examination. Additionally, the nanocomposite's cytotoxicity was examined to test its anti-proliferative effect against the T98, and SH-SY5Y cancer cell lines. It was also discussed how to effectively induce cancer cell death in vitro when manufactured nanocomposite was present. The results showed that the percentage of cells that survived was drastically decreased by the synthesized nanocomposite. However, further research must be done to identify the precise linked mechanisms.

Keywords

ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO Nanocomposite

Anticancer activity

Herbal extracts

Cytotoxicity

Green sol–gel auto-combustion synthesis

1 Introduction

The exceptional magnetic characteristics of orthorhombic perovskite-type ReFeO3 materials (where Re stands for the rare-earth element) have generated a lot of interest in recent years (Raji et al., 2021; Al-Mamari et al., 2022). In a variety of areas, including electromagnetic equipment, chemical sensors, fuel cells, catalysts, magneto-optic materials (Singh et al., 2008; Ju et al., 2011; Li et al., 2010; White and Sammells, 1993; Enhessari and Salehabadi, 2016; Miao et al., 2020); etc, rare-earth orthoferrites have been discovered. One of the attractive rare-earth ferrites is ErFeO3. ReFeO3 materials, although there aren't many studies on this particular type of substance. Therefore, in order for this material to be used in practice in the future, it is imperative that the synthesis process and magnetic properties of this material be thoroughly studied. As an illustration, L. Ma et al. created the PrFeO3 sensor for acetone detection using the electrospinning technique (Pei et al., 2021). Based on In-doped LaFeO3, G. H. Zhang et al. created a formaldehyde gas sensor, and the sensing capabilities improved with the addition of In (Zhang et al., 2019). According to earlier studies, erbium iron oxide (ErFeO3) has applications in photocatalysis and magnetism because of its magnetic characteristics, distinctive structure, outstanding chemical stability, and adequate band gap (Alam et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2015).Table 1.

Calcined time

Calcined temperature (oC)

Fuel

Sample Number

5

700

Sucrose

1

5

800

Sucrose

2

5

900

Sucrose

3

5

800

Sugar beet

4

To create the perovskite-type ReFeO3 materials, various synthetic procedures have been studied recently. These processes include the sol–gel method, co-precipitation, hydrothermal synthesis, and solid-state reaction (Zhang et al., 2020; Gómez-Cuaspud et al., 2017; Dhinesh Kumar and Jayavel, 2014; Afifah and Saleh, 2016; Lin et al., 2018; Lebid and Omari, 2014; Azouzi et al., 2019). When all of the aforementioned synthesis methods are taken into account, it can be said that the sol–gel process has numerous advantages over those used to create inorganic materials, including a high reaction rate, uniform combining at the atomic level, and homogeneous dispersion of particles (Jiang et al., 2012; Ming et al., 1999). The ErFeO3 nanocrystalline powders were made utilizing the sol–gel auto-combustion process with several combustion agents.

Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) have been employed extensively in biomedical research, due to their special magnetic characteristics, biocompatibility, and lack of toxicit. Numerous studies on superparamagnetic nanoparticles have been conducted in the fields of hyperthermia therapy, cell targeting, and medical imaging (Zhang et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2011; Salavati-Niasari et al., 2008). Superparamagnetic nanoparticles are used in cancer hyperthermal therapy (Maier-Hauff et al., 2011; Johannsen et al., 2007; Johannsen et al., 2007) because they have less side effects than radiotherapy or chemotherapy (Chu et al., 2013). Iron oxide nanoparticles' magnetic hyperthermia is carried on by dipole relaxation brought on by an alternating magnetic field (AMF) (Das et al., 2019). Tumors can be particularly destroyed by the heat produced by the locally injected magnetic nanoparticles, whereas healthy tissues are only minimally affected.

Graphene oxide is a two-dimensional substance consisting of a single layer, having a hexagonal and crystalline structure, and oxygen groups on the plates (Philipp et al., 2020). The main properties of graphene, such as conductivity (electrical-thermal), are not present in this material due to the presence of oxygen groups and disruption of the main graphene structure, but the presence of oxygen groups gives it the ability to interact with other materials more effectively and provides this possibility (Aradhana et al., 2018). Should slowly boned plates to polymers or other materials by covalent bonding.

This structure, due to its very high specific surface area, Hyperelasticity, better flexibility and dispersion, and the presence of oxygen groups, are used in solvents, biosensors, and catalysts (Bezzon et al., 2019). Among its applications are its use in medicine as nanocarriers of drugs (Daniyal et al., 2020), its use in tissue engineering to create biocompatible structures (Nalvuran et al., 2018).

According to the mentioned properties for perovskite and iron oxide group nanoparticles, In the current paper, ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite were constructed in the presence of sucrose as both alkaline and capping agent by sol–gel method. The anti-cancer activity of synthesized nanocomposite on two different cell lines (T98 and SH-SY5Y) was investigated as well. Based on our research, it is the first time that anticancer ability of ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite is presented.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Nitric acid (HNO3) was purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Company limited (Shanghai China). Fe(NO3)3·9H2O (98.5 % purity), Er2O3 (99.99 % purity), FeSO4·7H2O, sucrose and ethylenediamine were bought from the Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Corporation (Shanghai China). Sugar beet is a plant of the spinach family, with tuberous and sugary roots and large, broad leaves that store nutrients in their thick roots. The tuberous and conical roots of this plant have nutritional and medicinal uses. The chemical composition of sugar beet includes abundant sucrose in this plant and organic acids such as malic acid, oxalic acid, succinic acid, citric acid, gluconic acid, formic acid, acetic acid, butyric acid and so on. The amount of these acids is not constant and depends on the growing conditions of sugar beet and the storage time of sugar beet in cells. In this work, we used sugar beet juice, which is rich in sucrose, as a reaction fuel. Chemical sucrose was also used to compare the morphology of the nanoparticles.

2.2 Synthesis of ErFeO3 nanocrystalline powders

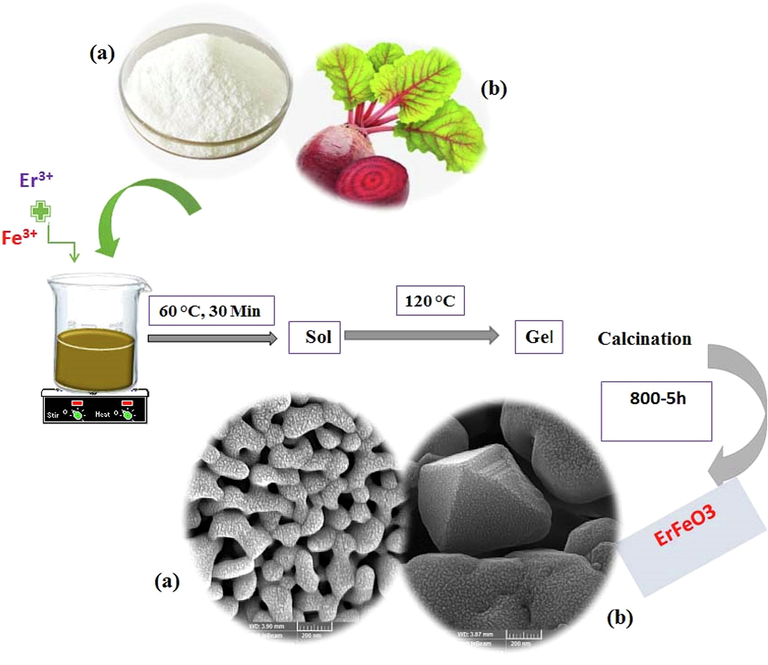

By using both natural, and chemical fuels (Sugar beet and sucrose), the sol–gel auto-combustion process was effectively used to create ErFeO3 nanocrystalline powders. At first, in a typical experiment, the Er2O3 can be dissolved in nitric acid while being heated, and stirred with a magnetic agitator in order to produce the Er(NO3)3 solution. After that, distilled water was used to dissolve the Fe(NO3)3·9H2O before it was exactly combined with the Er(NO3)3 in a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio. Also, sugar, and sugar beet were added to the aforementioned solutions in order to research how combustion agents influence the formation of ErFeO3 nanocrystalline powders. The ErFeO3 nanocrystalline was prepared by continually stirring, and heating the mixture until a sticky gel mixture formed. The resulting gel was heated to 75 °C for 24 h in an oven to finish drying. Following that, powders that had already been manufactured were calcined for 5 h at various temperatures. The ErFeO3 nanocrystalline powders were formed using the sol–gel auto-combustion approach, as shown in Scheme 1.

The formation process of the erfeo3 nanocrystalline powders by sol–gel auto-combustion method using sucrose and Sugar beet as combustion agent.

ErFeO3 nanostructure was prepared using auto-combustion sol–gel method. Initially, 1 mol (0.2 g) of Er(NO3)3·5H2O, and 1 mol (0.18 g) of Fe(NO3)2·6H2O were each separately distilled in 10 mL of water, and then 0.46 g of sucrose was added to the above solution. The solution was heated on a heater at 60 °C for 30 min, and then, was made viscous, and eventually transformed into a gel by heating it to 100 °C. The resultant gel was dried for 24 h at 75 °C in an oven, and the powder was then calcined for 5 h at 800 °C.

2.3 Synthesis of Fe3O4 nanoparticles

First, 0.2 g of FeSO4·7H2O, and 0.58 g of Fe(NO3)3·9H2O are dissolved separately in distilled water (20 mL). The two solutions were then added together, and subjected to vigorous magnetic stirring for 10 min. A few drops of ethylenediamine solution were slowly added to the solution under ultrasonic waves (60 W) for 5 min. A black precipitate is obtained which confirms the synthesis of Fe3O4. The Fe3O4 precipitate is then centrifuged, and washed with distilled water, and left in an atmosphere to dry.

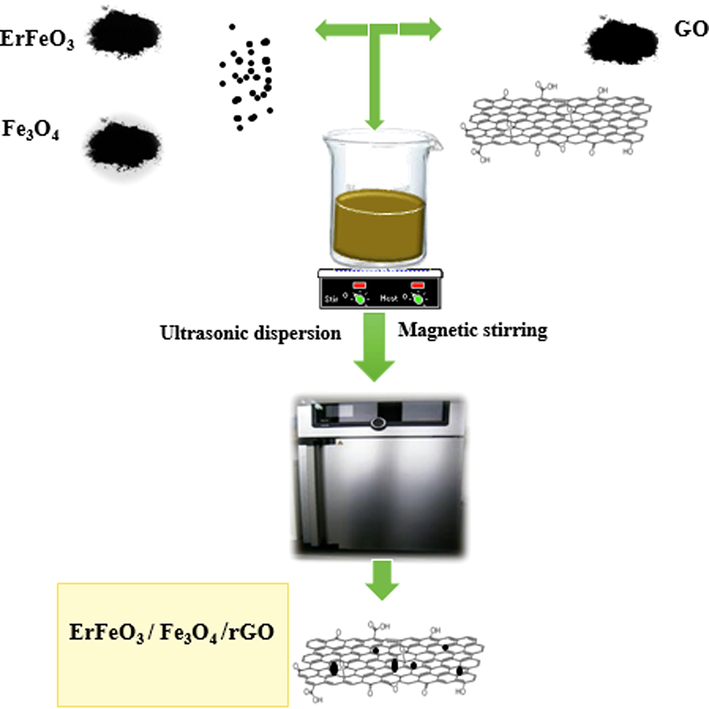

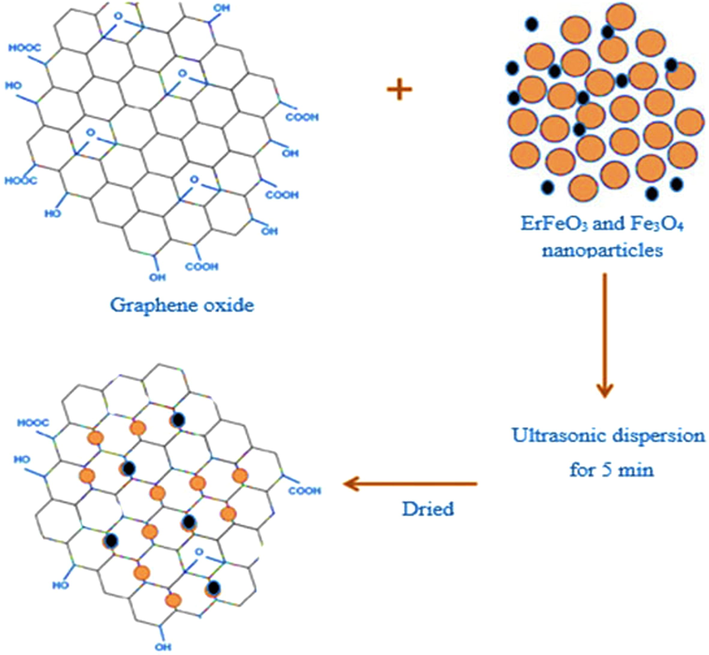

2.4 Synthesis ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite

To prepare ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite, 30 % by weight of ErFeO3, and Fe3O4 (synthesized by ultrasonic method) was added to 0.1 g of graphene oxide powder in 50 mL of distilled water, and placed on the stirrer for 10 min. Then dispersed under ultrasonic waves for 5 min, and the obtained nanocomposite was dried in an oven at 60 °C for 24 h. Scheme 2, and 3 indicated the fabricating the ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites.

A flowchart of fabricating the ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites.

The synthesis procedure for ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites.

2.5 Cell culture and treatment of cells by ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite

According to earlier reports, the T98, and SH-SY5Y cell lines were cultured (Amiri et al., 2018). Glioblastoma cell line 98G is utilized for drug development, and research on brain cancer in cell biology. The bone marrow biopsy line known as SK-N-SH was used to clone SH-SY5Y, which was initially described in 1973 (Biedler et al., 1973). A neuroblast-like SK-N-SH subclone, known as SH-SY, was subcloned as SH-SY5, which was subcloned a third time to create the 1978-described SH-SY5Y line (Biedler et al., 1973). Cloning is actually a form of artificial selection that involves the expansion of individual cells or a small group of cells that show a specific phenotypic of interest, in this case a feature that is neuron-like. The SH-SY5Y line has two X, and no Y chromosomes, making it genetically female. In a summary, Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media was used to cultivate human cells from the T98, and SH-SY5Y lines (Pasteur Institute, Tehran, Iran) in 25 cm2 flasks (Iwaki, Tokyo, Japan) at a cell density of 4 × 104 cells/mL (DMEM; Invitrogen Inc. Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA). The cultures received 1 % (v/v) penicillin/streptomycin, and 10 % (v/v) fetal calf inactivated serum supplements while being maintained at 37 ± 0.5 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5 % CO2. The medium was substituted every day.

For 24, and 48 h, groups of 4 × 104 cells (for each cell line) were exposed to ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite at varying concentrations (0.05–0.8 m/mL). It should be noted that ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite were suspended in DMEM medium, and that, in order to prevent agglomeration before application to cells, the suspensions of nanocrystals were sonicated at 40 W, for 10 min.

2.6 Cell viability

By measuring the amount of MTT dye that was decreased by active mitochondria in living cells, the proportion of viable cells was indirectly calculated (Mosmann, 1983). The Sladowski et al.-described modified method was used to perform the MTT experiment (Sladowski et al., 1993). In 96-well Iwaki plates, 2 × 102 cells were incubated with 1 mg/mL of MTT in DMEM at 37 °C for 2 h, and 5 % CO2. Following three rounds of washing with 0.2 M phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at pH 7.4, and 250 mL of DMSO were used to solubilize the reduced MTT formazan crystals. After that, an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader (Pharmacia Biotech, Stockholm, Sweden) recorded the optic density (OD) at 570 nm.

2.7 Sample characterization

A diffractometer made by the Philips Company was used to capture XRD (X-ray diffraction) patterns using X'PertPro monochromatized Cu Ka radiation (λ = 1.54 °A). TEM (Transmission Electron Microscopy) (HT-7700), and FESEM (Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy) (Mira3 Tescan) were used to examine the products' microscopic morphology. The Philips XL30 microscope was used to study the analysis of EDS (Energy Dispersive Spectrometry). Vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) were used to measure magnetic characteristics (Meghnatis. Daghigh Kavir Co.; Kashan Kavir; Iran). The N2 adsorption/desorption analysis (BET) was carried out at −196 °C using an automated gas adsorption analyzer (Tristar 3000, Micromeritics).

2.8 Statistical analysis

Data analysis was carried out using SPSS version 16 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), a statistical software for social research. The data was displayed as mean standard deviation of the mean (SEM). The t-Student’s test was used to establish the significance between the treated, and control groups with a 95 % of confidence. P-values of 0.05 or less were considered as significant.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 X-ray analysis

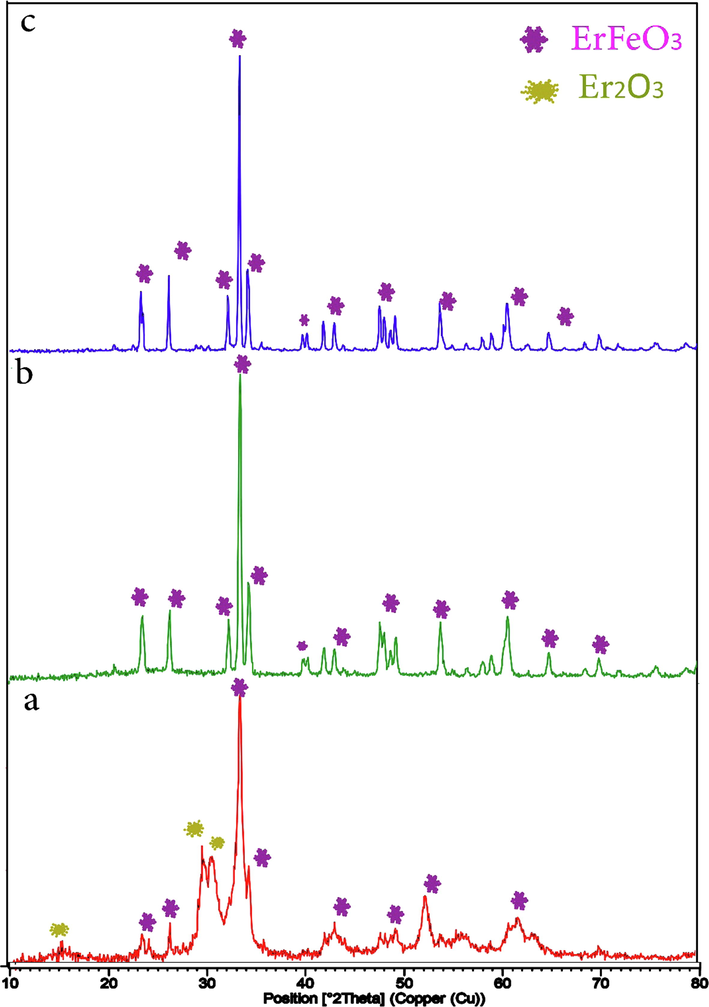

Fig. 1 illustrates the ErFeO3 nanoparticles XRD patterns, that were calcined at various temperatures: 700, 800, and 900 °C for five hours each, in the presence of sucrose. At a calcined temperature of 800 °C, ErFeO3 nanostructures were synthesized, which showed greater purity, and smaller particle size with the lattice constants a = 5.2670 A, b = 5.5810 A, and c = 7.5930 A (JCPDS 01–072-1281). Impure Er2O3 is observed at a calcined temperature of 700 °C, and the crystal size also increases with increasing temperature to 900 °C.

XRD patterns of the ErFeO3 nanoparticles provided in the presence of sucrose at various calcination temperatures: (a) 700 °C, (b) 800 °C and (c) 900 °C for 5 h.

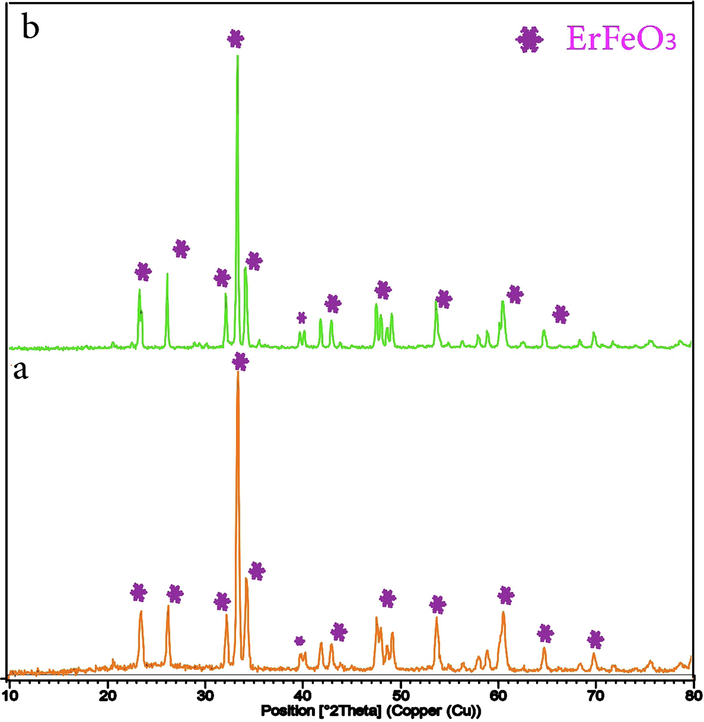

The XRD patterns of ErFeO3 nanocrystalline produced employing the combustion agents sucrose, and sugar beet are shown in Fig. 2(a, b). The fact that all of the XRD patterns of the annealed nanocrystalline powders in Fig. 2(a) match the standard card number (JCPDS 01–072-1281) shows that ErFeO3 nanocrystals were produced with both fuels present. Additionally, it is observed that the orthorhombic ErFeO3 maintains a reliable well-crystalline structure even when the calcination temperature reaches 900 °C. It can be said that, the sol–gel auto-combustion process could be employed to successfully manufacture orthorhombic perovskite-type ErFeO3 nanocrystalline powders.

XRD patterns of the ErFeO3 nanoparticles provided in the presence of two fuels: (a) sucrose and (b) Sugar beet at 800 °C for 5 h.

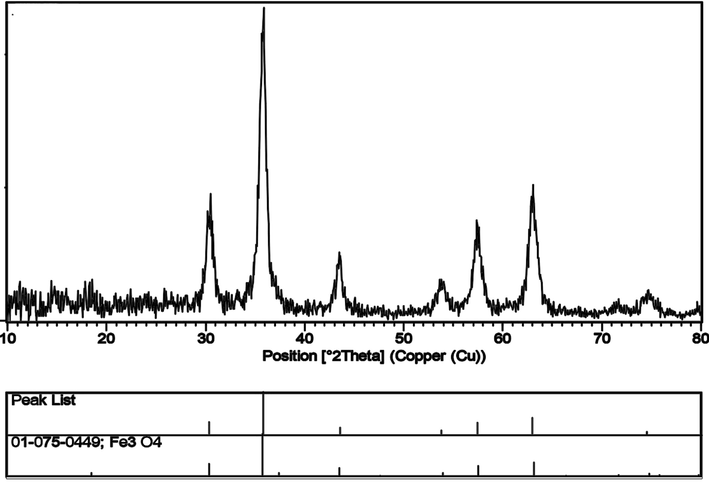

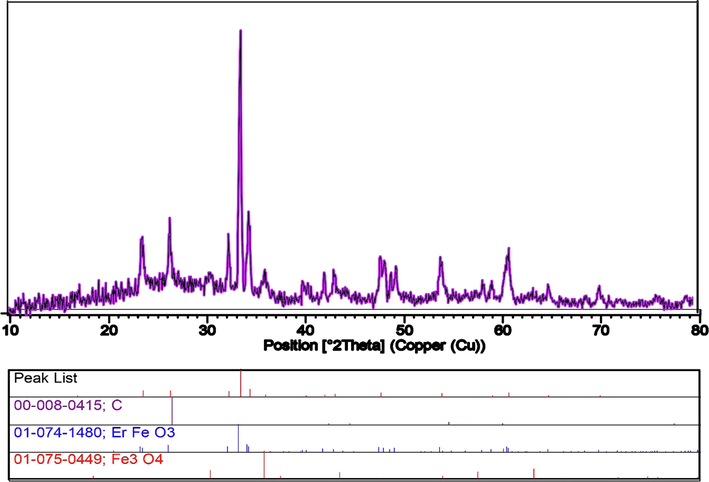

Fig. 3 indicates XRD patterns of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles synthesized by ultrasonic method and the powder XRD patterns of the produced ErFeO3, Fe3O4, and ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites are also shown in Fig. 4. It has been found that a single phase of ErFeO3 from the orthorhombic distorted perovskite phase can be used to explain all of the diffraction peaks of ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites. Moreover, no characteristic rGO (0 0 2) diffraction peaks were seen in the ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites because of the relatively low diffraction intensity, and low concentration of rGO present in the composite. The average crystallite size for ErFeO3, Fe3O4 nanoparticles, and ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites was computed using the Debye-Scherrer formula (Salavati-Niasari et al., 2009):

XRD patterns of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles synthesized by ultrasonic method.

XRD patterns of the ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites.

Where λ is the X-ray wavelength, K is a constant taken as 0.89, θ is the angle of Bragg diffraction, and B is the full width at half maximum.The average size of nanoparticles was found to be approximately 36.4, 15.6, and 27.3 nm, respectively.

3.2 FTIR spectra analysis

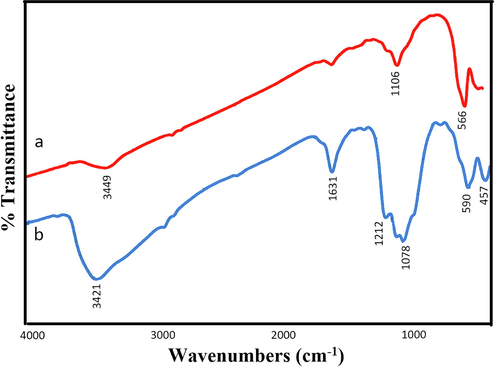

The produced samples were examined by FT-IR spectroscopy, and the spectra are displayed in Fig. 5 (a, b) to confirm the functional groups of ErFeO3, and ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites. The FT-IR spectrum of ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO, and ErFeO3 demonstrates some broad peaks. The unique peaks at around ∼ 3420–3449 cm−1 were related to the water molecule bending vibrations that were absorbed over the powder's surface during the initial preparation process (Salavati-Niasari, 2006). The extra peaks at 1078, and 1212 cm−1 are caused by the stretching vibrations of the C—O, and C—OH atoms in carboxyl (COOH) groups, respectively. The peak at 1631 cm−1 indicates the sp2 hybridized structure of graphene and is associated with the aromatic C—C bond (Ji et al., 2014; Luo et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2010). The B—O (Fe—O) stretching vibration, which is a property of the octahedral BO6 groups in the perovskite (ABO3) compound, is thought to be responsible for the strong absorption band at 566 cm−1 for pure ErFeO3. This band typically appears in the wavenumber range of ∼ 500–600 cm−1 (Abazari and Sanati, 2013; Dhinesh Kumar et al., 2017). Both the GO, and ErFeO3 vibrations are found for ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites, supporting their synthesis. Furthermore, the presence of carbon in the nanocomposites is seen to produce substantial stretching vibrations at 1630 cm−1.

the FTIR spectrum of (a) ErFeO3 nanoparticles in presence of sucrose and (b) ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites.

3.3 Morphology and microstructure analysis using FESEM and HR-TEM

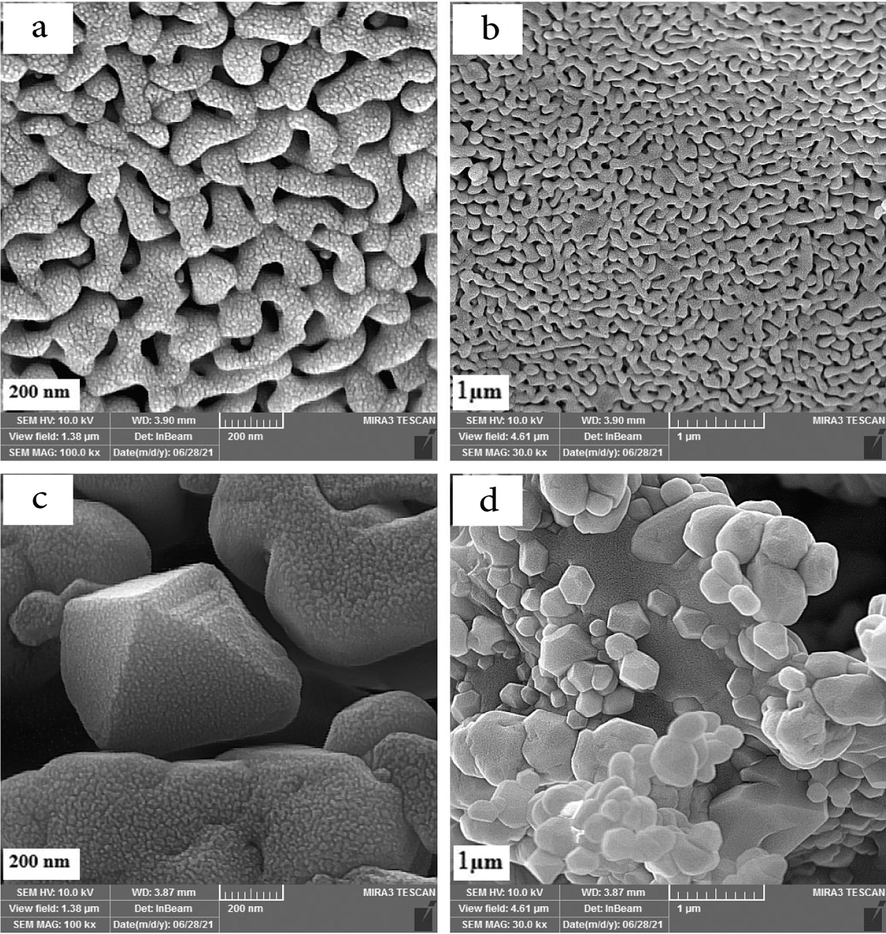

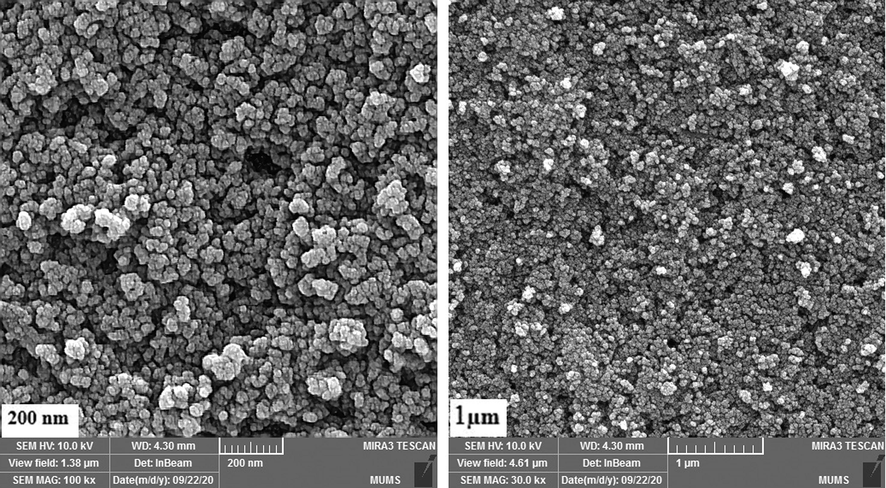

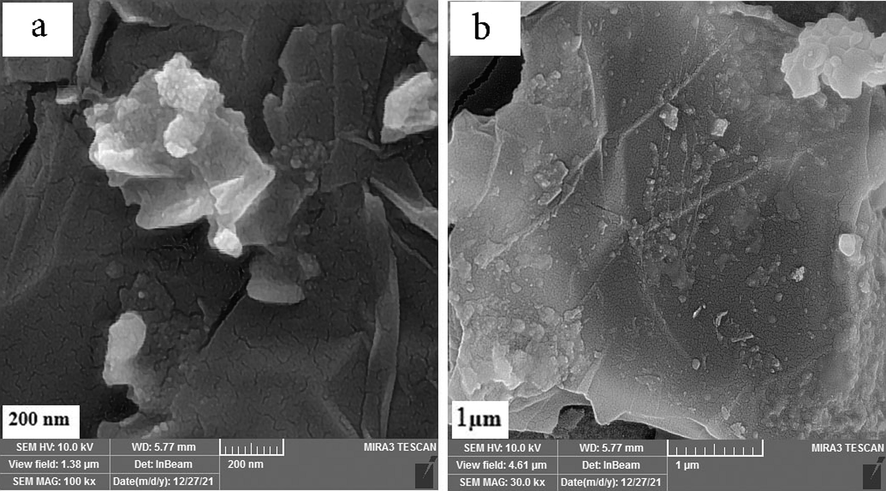

SEM photographs of ErFeO3 nanocrystalline powders made using sucrose (a, b) and sugar beet (c, d) as the combustion agent are shown in Fig. 6. It was found that ErFeO3 nanocrystalline powders were randomly dispersed in terms of their sizes and shapes and had a continuous porosity network. This might be because a significant quantity of gas was released during the automated combustion process. Morphology of ErFeO3 nanocrystalline powders prepared in the presence of sucrose as a combustion agent in Fig. 6(a, b) in comparison with the samples in Fig. 6(c, d), showes that ErFeO3 nanocrystals prepared with sucrose have more accessible and uniform surface, while in the presence of sugar beet multidimensional Structure and bigger particles size was observed. Additionally, iron oxide nanoparticles with a particle size average of 20 nm are shown in Fig. 7 in a fine, and uniform manner. Fig. 8 also displays the SEM image of the ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites, which clearly show ErFeO3, and Fe3O4 nanoparticles on a graphene oxide substratein.

SEM images of the ErFeO3 nanoparticles provided in the presence of two fuels: (a,b) sucrose and (c,d) Sugar beet at 800 °C for 5 h.

SEM images of the Fe3O4 nanoparticles synthesized by ultrasonic method.

SEM images of of the ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites.

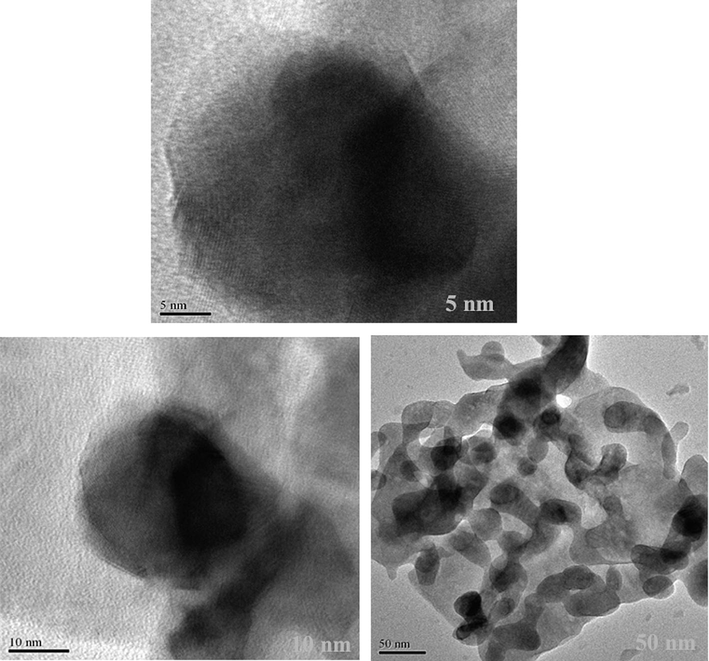

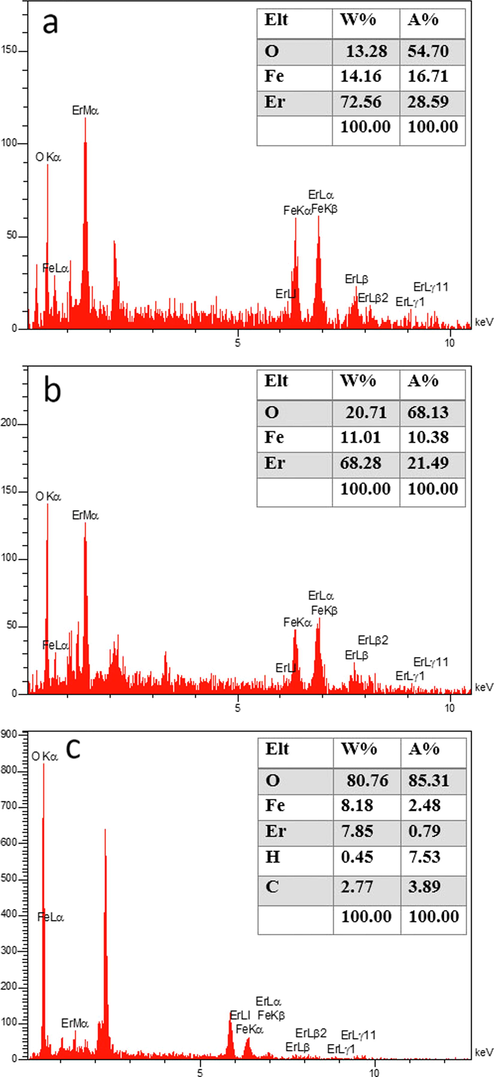

To have a better understanding, the structure of the produced nanocomposite was further examined by TEM at various magnifications (Fig. 9). TEM images clearly show the size, and characteristic structure of spheres with narrow size distribution, which is compatible with the aforementioned SEM and XRD analyses. Fig. 10(a-c) displays Scattered X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) of ErFeO3 nanostructure (in the presence of sucrose, sugar beet fuels), and ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites. As shown in Fig. 10, the presence of elements Er, Fe, C, and O, and the absence of impurities in the composition is confirmed.

TEM images of of the ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites.

EDS patterns of ErFeO3 provided in the presence of two fuels: (a) sucrose and (b) Sugar beet and (c) ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites.

3.4 Magnetic properties

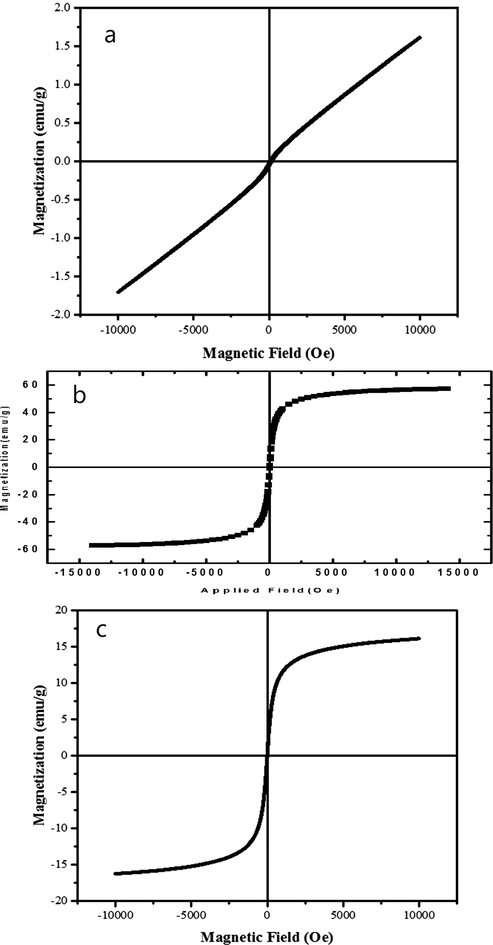

To determine the magnetic characteristics of pure ErFeO3, Fe3O4, and ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite, a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) was used (Fig. 11(a-c)). The highest applied field was 1000 Oe at ambient temperature. The magnetic hysteresis loop for ErFeO3 particles at 300 K was shown in Fig. 11(a). The M−H curve's outline reveals that ErFeO3 powders are paramagnetic and that their magnetization reaches 2 emu/g at a 50,000 Oe field. Fig. 11(b) shows the magnetic hysteresis rings for Fe3O4 powders at 300 K, which has a superparamagnetic behavior with a magnet of 60 emu/g. Fig. 11(c) shows the magnetic hysteresis rings for the ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite. A magnetism of 15 emu/g in a field of 50,000 Oe is seen in the M−H curve for ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites, indicating that these materials also exhibit superparamagnetic properties.

M- H hysteresis at 300 K for (a) ErFeO3 (b) Fe3O4 nanostructures and (C) the ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites.

3.5 Surface area and pore volume analysis

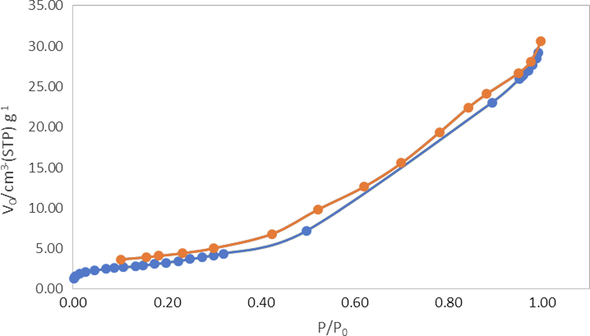

The nitrogen adsorption/desorption were examined via a MicroActive for TriStar II plus 2.03 instrument using the BET approach in order to learn more about the generated ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites. As According to Fig. 12, the nanocomposites' BET surface area, and pore volume are 13.3959 m2/g, and 0.040171 cm3/g, respectively.

N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms and inset image of pore size distribution of ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites.

3.6 ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanoparticles cytotoxicity studies

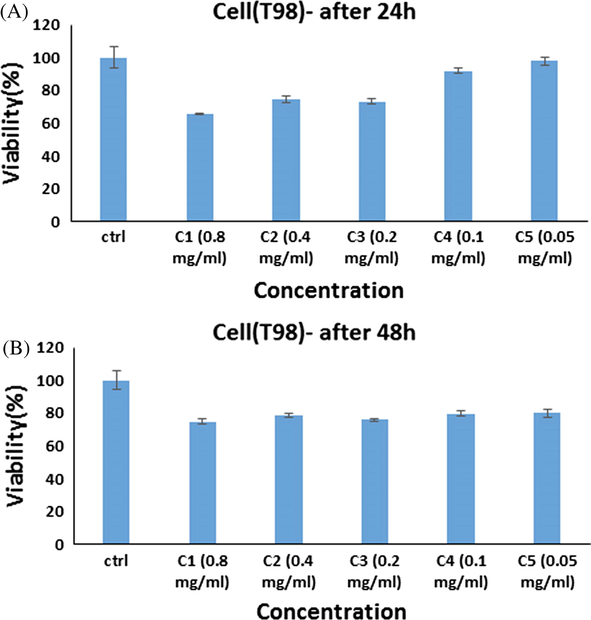

The survivability of T98 cell lines exposed to ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites at various doses for 24 h (A), and 48 h (B) is shown in Fig. 13′s in vitro cell viability experiment. Viability was noticeably decreased in cultivated cells when NPs were present at various doses, suggesting a dose-dependent effect. According to Fig. 13, the ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO NPs had a significant influence on the cytotoxicity index of malignant cell lines. The fact that glioblastoma cells demonstrate a greater rate of metabolism, and rapid cell division, as well as better NPs internalization, may be the cause of the inhibitory effects of NPs on this cancer. This increased internalization results in a higher rate of cell death (Goudarzi et al., 2021). With the passage of time, the level of toxicity in different concentrations increases, but the level of toxicity in different doses becomes similar to each other. In total, all the nanoparticles showed similar levels of toxicity to this cell in 24, and 48 h.

In vitro cell viability assay, Cell viability of T98 cell lines incubated with ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites at different concentrations for 24 h(a) and 48 h (b) (SD ± 2 %).

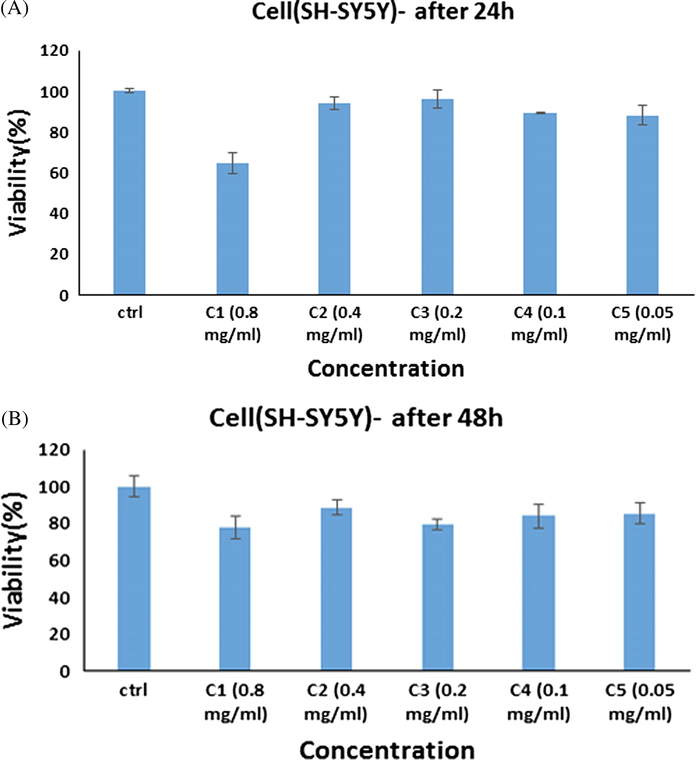

The in vitro cell survival assay of SH-SY5Y cell lines treated with ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites at various doses for 24 h (A), and 48 h (B) was shown in Fig. 14. Reduced cellular ATP level, decreased dehydrogenase activity, and formation of reactive oxygen species all contribute to decreased cell viability in the presence of ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO NPs. Cell death results from damage to the mitochondrial respiratory chain and other cellular components. Therefore, rather than causing a general disruption in cell membrane functions, phytogenic NPs' cytotoxicity is reliant on the kind of cell that exhibits an unique intracellular mechanism for growth suppression. However, NPs' cytotoxicity is solely determined by their surface chemistry, size, shape, duration of contact, and aggregation state (Amiri et al., 2018). Concequuently, the toxicity level of all nanoparticles was higher in glioblastoma cells than in neuroblastoma cells.

In vitro cell viability assay, Cell viability of SH-SY5Y cell lines incubated with ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposites at different concentrations for 24 h(a) and 48 h (b) (SD ± 2 %).

4 Conclusion

The current study reported the green synthesis of ErFeO3/Fe3O4/rGO nanocomposite using sucrose, that indicates the role of both capping and reducing agent. The TEM investigation supported the XRD findings that the pure particles were 37 ± 2 nm in size. To determine the nanocomposite's anti-proliferative impact on the cancer cell lines T98, and SH-SY5, the cytotoxicity of the compound was examined using the MTT test. It was shown that nanoparticles can efficiently cause cell death in both the cells under study (human primary glioblastoma, and neuroblastoma cancer cell lines). The toxicity level of all nanoparticles was higher in glioblastoma cells than in neuroblastoma cells. It will be necessary to do more research into surface alterations, in vivo assessments, and pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics studies.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mahin Baladi: Software, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. Mahnaz Amiri: Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Software, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Masoud Salavati-Niasari: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Data curation, Validation, Resources, Visualization, Funding acquisition.

Acknowledgements

The authors are appreciative of the committee of Iran National Science Foundation (INSF, 97017837), and the University of Kashan for financing this research by Grant No (159271/MB2).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Perovskite LaFeO3 nanoparticles synthesized by the reverse microemulsion nanoreactors in the presence of aerosol-OT: morphology, crystal structure, and their optical properties. Superlattice. Microst.. 2013;64:148-157.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and catalytic properties of perovskite LaFeO3 nanoparticles. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser., IOP Publishing 2016:012030.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microwave synthesis of surface functionalized ErFeO3 nanoparticles for photoluminescence and excellent photocatalytic activity. J. Lumin.. 2018;196:387-391.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural, Mössbauer, and Optical studies of mechano-synthesized Ru3+-doped LaFeO3 nanoparticles. Hyperfine Interact.. 2022;243(1):1-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic nickel ferrite nanoparticles: Green synthesis by Urtica and therapeutic effect of frequency magnetic field on creating cytotoxic response in neural cell lines. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2018;172:244-253.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and in vitro evaluation of a novel magnetic drug delivery system; proecological method for the preparation of CoFe2O4 nanostructures. J. Mol. Liq.. 2018;249:1151-1160.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of mechanical, electrical and thermal properties in graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide filled epoxy nanocomposite adhesives. Polymer. 2018;141:109-123.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sol-gel synthesis of nanoporous LaFeO3 powders for solar applications. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process.. 2019;104:104682

- [Google Scholar]

- Carbon nanostructure-based sensors: a brief review on recent advances. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng.. 2019;2019

- [Google Scholar]

- Morphology and growth, tumorigenicity, and cytogenetics of human neuroblastoma cells in continuous culture. Cancer Res.. 1973;33(11):2643-2652.

- [Google Scholar]

- Near-infrared laser light mediated cancer therapy by photothermal effect of Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2013;34(16):4078-4088.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive review on graphene oxide for use in drug delivery system. Curr. Med. Chem.. 2020;27(22):3665-3685.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in magnetic fluid hyperthermia for cancer therapy. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2019;174:42-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile hydrothermal synthesis and characterization of LaFeO3 nanospheres for visible light photocatalytic applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron.. 2014;25(9):3953-3961.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile preparation of LaFeO3/rGO nanocomposites with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater.. 2017;27(4):892-900.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perovskites-based nanomaterials for chemical sensors. Prog. Chem. Sensor 2016:59-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- One-step hydrothermal synthesis of LaFeO3 perovskite for methane steam reforming. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal.. 2017;120(1):167-179.

- [Google Scholar]

- ZnCo2O4/ZnO nanocomposite: Facile one-step green solid-state thermal decomposition synthesis using Dactylopius Coccus as capping agent, characterization and its 4T1 cells cytotoxicity investigation and anticancer activity. Arab. J. Chem.. 2021;14(9):103316

- [Google Scholar]

- A novel reduced graphene oxide/Ag/CeO2 ternary nanocomposite: green synthesis and catalytic properties. Appl. Catal. B. 2014;144:454-461.

- [Google Scholar]

- Low-temperature combustion synthesis of nanocrystalline HoFeO3 powders via a sol–gel method using glycin. Ceram. Int.. 2012;38(5):3667-3672.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morbidity and quality of life during thermotherapy using magnetic nanoparticles in locally recurrent prostate cancer: results of a prospective phase I trial. Int. J. Hyperth.. 2007;23(3):315-323.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thermotherapy of prostate cancer using magnetic nanoparticles: feasibility, imaging, and three-dimensional temperature distribution. Eur. Urol.. 2007;52(6):1653-1662.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sol–gel synthesis and photo-Fenton-like catalytic activity of EuFeO3 nanoparticles. J. Am. Ceram. Soc.. 2011;94(10):3418-3424.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and electrochemical properties of LaFeO3 oxides prepared via sol–gel method. Arab. J. Sci. Eng.. 2014;39(1):147-152.

- [Google Scholar]

- Exchange-coupled magnetic nanoparticles for efficient heat induction. Nat. Nanotechnol.. 2011;6(7):418-422.

- [Google Scholar]

- Controllable synthesis of pure-phase rare-earth orthoferrites hollow spheres with a porous shell and their catalytic performance for the CO+ NO reaction. Chem. Mater.. 2010;22(17):4879-4889.

- [Google Scholar]

- The structure and magnetic properties of magnesium-substituted LaFeO3 perovskite negative electrode material by citrate sol-gel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2018;43(28):12720-12729.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of As (III) and As (V) from water using magnetite Fe3O4-reduced graphite oxide–MnO2 nanocomposites. Chem. Eng. J.. 2012;187:45-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of intratumoral thermotherapy using magnetic iron-oxide nanoparticles combined with external beam radiotherapy on patients with recurrent glioblastoma multiforme. J. Neurooncol. 2011;103(2):317-324.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emerging Perovskite Electromagnetic Wave Absorbers from Bi-Metal–Organic Frameworks. Cryst. Growth Des.. 2020;20(7):4818-4826.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combustion synthesis and characterization of Sr and Ga doped LaFeO3. Solid State Ion.. 1999;122(1–4):113-121.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65(1–2):55-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanofibrous silk fibroin/reduced graphene oxide scaffolds for tissue engineering and cell culture applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2018;114:77-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modulated PrFeO3 by doping Sm3+ for enhanced acetone sensing properties. J. Alloy. Compd.. 2021;856:158274

- [Google Scholar]

- Anisotropic thermal transport in spray-coated single-phase two-dimensional materials: synthetic clay versus graphene oxide. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12(16):18785-18791.

- [Google Scholar]

- Twitching the inherent properties: the impact of transition metal Mn-doped on LaFeO3-based perovskite materials. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron.. 2021;32(20):25528-25544.

- [Google Scholar]

- Host (nanocavity of zeolite-Y)–guest (tetraaza[14]annulene copper(II) complexes) nanocomposite materials: synthesis, characterization and liquid phase oxidation of benzyl alcohol. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem.. 2006;245(1–2):192-199.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Flexible ligand synthesis, characterization and catalytic oxidation of cyclohexane with host (nanocavity of zeolite-Y)/guest (Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes of tetrahydro-salophen) nanocomposite materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater.. 2008;116(1–3):77-85.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of pure cubic zirconium oxide nanocrystals by decomposition of bis-aqua, tris-acetylacetonato zirconium (IV) nitrate as new precursor complex. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2009;362(11):3969-3974.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Electronic and magneto-optical properties of rare-earth orthoferrites RFeO3 (R= Y, Sm, Eu, Gd and Lu) J. Korean Phys. Soc.. 2008;53(2):806-811.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of Nanoparticulate ErFeO3 by Microwave Assisted Process and its Photocatalytic Activity. Mater. Sci. Forum Trans Tech Publ 2015:140-143.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile solvothermal synthesis of a graphene nanosheet–bismuth oxide composite and its electrochemical characteristics. Electrochim. Acta. 2010;55(28):8974-8980.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perovskite anode electrocatalysis for direct methanol fuel cells. J. Electrochem. Soc.. 1993;140(8):2167.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of In-doped LaFeO3 hollow nanofibers with enhanced formaldehyde sensing properties. Mater. Lett.. 2019;236:229-232.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mesoporous LaFeO3 perovskite derived from MOF gel for all-solid-state symmetric supercapacitors. Chem. Eng. J.. 2020;386:124030

- [Google Scholar]

- Imaging and cell targeting characteristics of magnetic nanoparticles modified by a functionalizable zwitterionic polymer with adhesive 3, 4-dihydroxyphenyl-l-alanine linkages. Biomaterials. 2010;31(25):6582-6588.

- [Google Scholar]