Translate this page into:

Green synthesis of Cr2O3 nanoparticles by Cassia fistula, their electrochemical and antibacterial potential

⁎Corresponding authors. shabchem786@gamil.com (Shabbir Hussain), zeeshanmustafa@lgu.edu.pk (Zeeshan Mustafa)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Chromium oxide (Cr2O3) nanoparticles (NPs) find applications in modern science and technology due to their chemical stabilities, high-density corners and magnetic/electrical/catalytic properties. Current studies were performed to produce the (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)et NPs by treating chromium acetate with the aqueous and ethanolic extracts, respectively of Cassia fistula leaves; the same reaction was also performed in the presence of NaOH to yield the (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa NPs, respectively. The synthesized NPs were characterized by XRD, FTIR, Raman spectroscopy, UV–Vis spectroscopy, SEM, TGA and DSC analysis and examined for their electrochemical properties. Their antibacterial potential was tested by biofilm inhibition and agar well diffusion methods. XRD studies revealed that Cr2O3 NPs possessed hexagonal crystal structures with the crystallite sizes of 14.85 to 23.90 nm; the lowest size (14.85 nm) was possessed by (Cr2O3)et. FTIR and Raman spectroscopies verified the +3-oxidation state of chromium and corresponding Cr-O and Cr=O vibrations. Raman spectroscopy determined A1g vibration modes (540.50–557.07 cm−1) with rhombohedral Cr2O3 structure, high degree of crystallinity and existence of Cr3+ ions in octahedral coordination whereas Eg vibration modes were displayed at 306.04–350.87 cm−1 and 602.47–613.81 cm−1. UV–Visible spectroscopy has shown band gaps in the range of 4.06–4.40 eV. The SEM images demonstrated the spherical morphology with a high degree of agglomeration between fine particles. The synthesized NPs exhibited good thermal stabilities up to 600 °C. The CV curves displayed the oxidation–reduction peaks and reversible behavior whereas GCD curve indicated the possible energy storage applications of NPs. (Cr2O3)aqNa NPs showed the highest specific capacitance (234.35 mAhg−1) at 1 mA current density. The biofilm inhibitions of the investigated NPs were comparable to those of the standard antibacterial drug (ciprofloxacin); the activity of (Cr2O3)etNa was found even better than that of ciprofloxacin. The NPs were more active against Escherichia coli (Gram-negative) as compared to those against Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive).

Keywords

Cr2O3

Green Synthesis

Spectroscopy

Electrochemical

Biological

1 Introduction

Nanoparticles (NPs) find a tremendous commercial importance due to their characteristic magnetic (Fang et al., 2018), catalytic (Shen et al., 2021; Guan et al., 2022), thermal, mechanical, electrical, optical, scattering, physio-chemical (Titus et al., 2019; Kaur and Sidhu 2021) and photoluminescence (Kharangarh et al., 2017; Kharangarh et al., 2018a) properties. Their role as therapeutic agents (Hussain and Amjad 2021) for the treatment of inflammatory, cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases (Munir et al., 2020) and in targeted drug delivery (Zulfiqar et al., 2020) is well-recognized. They have also been used as packaging materials (Devatha and Thalla 2018), catalysts (Kuwauchi et al., 2012), nanomagnets (Ma et al., 2020), high performance supercapacitors (Kharangarh et al., 2022a), pseudocapacitors electrode materials (Kharangarh et al., 2020), in electronics industry (Abbasi et al., 2019; Iqbal et al., 2020a), optoelectronics, bioimaging (Kharangarh et al., 2018b), photocatalysis (Shahzad et al., 2020; Javed et al., 2021), mechanics and cosmetics (Mueez et al., 2022). Their role in the energy related applications (Kharangarh et al., 2022b) and degradation of environmental contaminants is appreciable (Azizi et al., 2016).

Cr2O3 NPs are notable inorganic materials which possess outstanding and interesting applications in modern science and technology (Almontasser and Parveen 2020; Ghotekar et al., 2021). They find applications in corrosive resistant and high temperature resistant materials (Yang et al., 2009), liquid crystal displays (Hwang and Seo 2010), green pigment, catalysts (Jaswal et al., 2014), heterogeneous catalysts, thermal protection coating materials, energy storage materials, solar energy collectors, hydrogen storage and antimicrobial agents (Almontasser and Parveen 2020), sensors, biomedicines, vaccinations, cosmetics, antigen detection, pathogen detection, diagnostics, enzymes and radiography (Boscher et al., 2008), catalysis, photo catalysis, protective coatings, green pigments, solar cells, piezoelectric devices and fuel cells (Alarifi et al., 2016). Cr2O3 NPs can be synthesized by thermal decomposition, chemical precipitation, microwave, combustion synthesis, sol–gel, micro emulsion, solvothermal, solution plasma discharge, mechanical grinding, precipitation method, arc discharge method, hydrothermal, co-precipitation, biological, mechanochemical, electrochemical (Sangwan and Kumar 2017), chemical vapor deposition and template (Sone et al., 2016) methods. However, the physical and chemical synthetic methods are associated with certain limitations on commercial scale use of Cr2O3 particles due to their expensive synthetic routes and equipment, low yield and involvement of the toxic chemicals. So, green process or bio-synthesis method has been endorsed by R & D community; this procedure involves the use of plants parts or microorganism for the syntheses of different NPs (Sackey et al., 2021). Currently, a large focus has been made on the green synthesis of NPs due to its eco-friendly, sustainable and reliable protocol. It is an important tool which can be used to reduce the hazardous effects associated with traditional physical and chemical synthetic procedures at laboratory/industry level (Singh et al., 2018, Iqbal et al., 2020b; Korde et al., 2020). Biological approaches using plant materials are highly suitable for the manufacture of Cr2O3 NPs due to their myriad medicinal, health, economic and environmental advantages (Ghotekar et al., 2021) and numerous applications in biology and medicine (Naseer et al., 2020). These methods involve the use of bio-organisms as reducing and reaction capping agents in NPs synthesis (Ramesh et al., 2012a). Plant leaves act as an amazing source of phytochemicals which can easily be extracted by using various solvents. The leave extracts of plants thus act as stabilizing and reducing agents and facilitate the formation of various sized NPs in different yields. Since, the concentrations of biomedical reducing agents is varied depending upon the plant species so the extent of NP formation is largely affected by the composition of leaves extracts. Numerous phyto-constituents including carboxylic acids, flavones, terpenoids, amides, ketones, and aldehydes play a key role in the formation of NPs (Hussain et al., 2023). The plant metabolites such as polyphenols, sugars, phenolic acids, terpenoids, alkaloids and proteins play an important role in the bio-reduction of metal ions. Flavonoids are polyphenolic compounds (e.g., isoflavonoids, flavonols, chalcones, anthocyanins, flavanones and flavones) with different functional groups which have ability to chelate with the metal ions and reduce them into NPs. It is proposed that the conversion of flavonoids from one tautomeric (the enol) to the other tautomeric (the keto) form can release a reactive H-atom which causes the reduction of the metal ions into NPs (Buazar 2019; Khalafi et al., 2019). Due to strong affinities of the N–H and O–H functional groups towards metal ions, a large number of electron donor amine and hydroxyl functional groups act as potential reducing and capping agents to donate electrons to the metal ions. In addition to this, numerous biomacromolecules can also behave as surface protectors of the synthesized NPs through electrostatic and/or steric repulsions, thus preventing the formation of aggregates (Rezazadeh et al., 2020; Safat et al., 2021).

The green syntheses of chromium oxide (Cr2O3) NPs were reported earlier in literature by using the leaves/flowers/fruits/peels extracts of various plants (Section 3.10, Table 3). However, there are still no reports on the green synthesis of Cr2O3 NPs by using the leave extract of Cassia fistula (Golden Shower or Amaltas, Fig. 1). C. fistula is a very common Indian plant which is native to Tropical Asia and widely cultivated in Brazil, East Africa, Mexico and South Africa (Bhalerao and Kelkar 2012). In current studies, chromium oxide (Cr2O3) NPs were synthesized by using the aqueous/ethanolic extracts of Cassia fistula leaves as reducing and capping agents. For comparison of results, the same syntheses were also performed in the presence of sodium hydroxide. The investigated synthetic methods rely on use of water (universal solvent) and ethanol solvents which are safe and do not add any poisonous contaminants to the environment. The synthesized NPs were characterized by XRD, FTIR, Raman, UV–Visible, SEM, TGA and DSC. They were finally evaluated for their antibacterial potential by biofilm inhibition and agar well diffusion methods. Their electrochemical studies were performed by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and Galvanostatic Charge-discharge (GCD) evaluations.

Cassia fistula (golden shower) used for the synthesis of Cr2O3 nanoparticles.

2 Materials and methods

The sodium hydroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), chromium(III) acetate (Uni-Chem) and ethanol (analytical grade) were used for the syntheses of NPs. Nutrient broth and nutrient agar were procured from Oxoid, UK. The structural parameters of NPs were determined by using Bruker AXS, D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (XRD). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed by Hitachi S4800. Fourier Transform Infra-Red (FTIR) spectroscopy was performed by using Carry 630 FTIR spectrometer. UV–Visible spectroscopic analysis was done by SPECORD 200 PLUS spectrometer. Raman spectra were recorded by Renishaw in Vis Reflex Raman spectrometer. The material was subjected to thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DTA) by SDT (Q600) thermal analyzer (TA Instruments, USA) under nitrogen atmosphere at the heating rate of 20 °C min−1. Galvanostat/Potentiostat (CS300 model, China) was used to evaluate the electrochemical properties and charging/discharging potential of the NPs by a reported procedure (Wyantuti et al., 2015).

Antibacterial activities of the synthesized NPs were performed by agar well diffusion method (Candan et al., 2003) using ciprofloxacin as a standard positive control against S. aureus (Gram-positive) and E. coli (Gram-positive). The identities and purities of the bacterial strains were verified by the Institute of Microbiology, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan. The activities were performed at Department of Biochemistry, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad. Nutrient broth and nutrient agar were used as growth media for bacteria in biofilm inhibition and agar well diffusion methods, respectively. The zones of inhibition were measured by a zone reader (Hussain et al., 2015a).

The extractions and syntheses were performed at Nanotechnology Unit of Health Science Research Center, Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia in collaboration with Department of Chemistry, Lahore Garrison University, Lahore, Pakistan.

2.1 Identification and collection of plant material

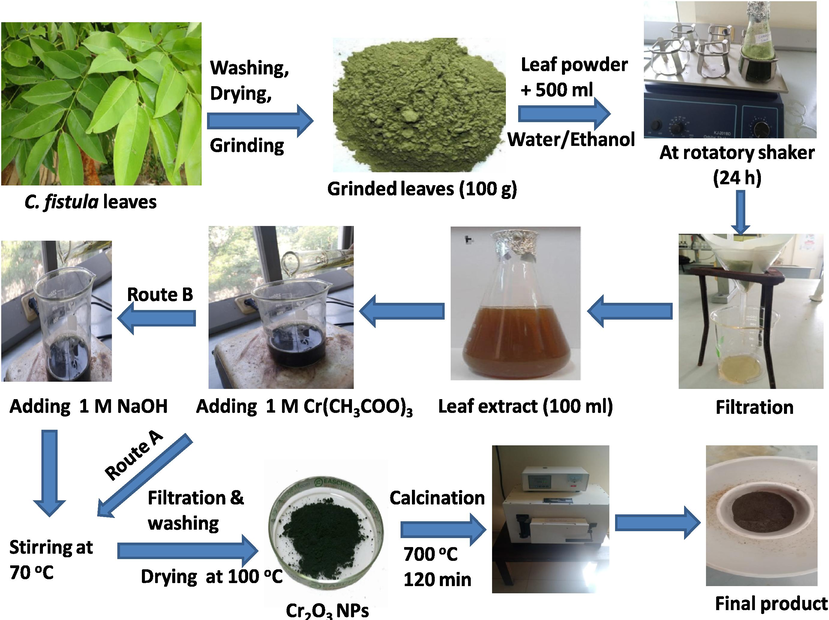

The green leaves of Cassia fistula (golden shower) (Fig. 1) were collected from Govt. College Vehari, Punjab (Pakistan) in November 2021. The plant material was identified by Department of Biology, Lahore Garrison University, Lahore, Pakistan. The leaves were washed with distilled water many times for the removal of dust particles (Fig. 2) and dried under the shade for two weeks. They were finally ground with the help of a grinder and passed through a sieve (80 mesh size) to obtain the fine powder (Fig. 2) which was used for stored in a polythene bag at room temperature (Khan et al., 2021) for further use.

Preparation of aqueous/ethanolic leaves extracts of C. fistula leaves and their use in the bio-syntheses of chromium oxide NPs; the route A was used to produce (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)et NPs (in the absence of NaOH) whereas (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa NPs were formed through route B (in the presence of NaOH).

2.2 Preparation of aqueous/ethanolic extracts of Cassia fistula leaves

50 g dried powder of C. fistula leaves was mixed with 500 mL of distilled water and stirred in an orbital shaker for 24 h at room temperature. Then the mixture was filtered through a Whatman No. 1 filter paper to obtain a brown colored filtrate (aqueous extract) which was stored at 4 °C for further use (Fig. 2). The same procedure was used for the preparation of ethanolic extract by shaking 50 g of dried powder with 500 mL of ethanol.

2.3 Preparation of (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)et NPs by using aqueous/ethanolic extracts

The (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)et NPs were synthesized by a reported procedure (Hussain et al., 2023) after some modifications. Freshly prepared 0.5 M solution (25 mL) of chromium(III) acetate was taken in a conical flask and placed on a magnetic stirrer. Then 100 mL aqueous extract of C. fistula leaves was added with stirring at room temperature. After 30 min, the temperature was increased to 70 °C and the mixture was further stirred for 60 min. Then the reaction flask was kept aside to achieve the room temperature. The black colored precipitates were filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper and rinsed with distilled water 3 times. They were then dried in an oven at 100 °C for 2 h to obtain a black colored residue (1.17 g) which was ground into a fine powder, transferred into a china dish and kept in a muffle furnace for 2 h at 700 °C for calcination. The final product (0.93 g) of (Cr2O3)aq NPs was stored for further use. % age Yield of (Cr2O3)aq NPs = 98.10 %.

Same procedure was repeated to produce (Cr2O3)et NPs by using 200 mL ethanolic extract of Cassia fistula leaves and 40 mL of freshly prepared chromium acetate solution (0.1 M). The obtained black precipitates (0.87 g) were calcinated for 2 h at 700 °C to produce 0.19 g of the final product. % age Yield of (Cr2O3)et NPs = 62.70 %.

Fig. 2 (Route A) displays the route for the green synthesis of (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)et NPs.

2.4 Preparation of (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa NPs by using aqueous/ethanolic extracts in the presence of NaOH

The (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa NPs were synthesized by a reported procedure in the presence of NaOH (Hussain et al., 2023) with some modifications. Freshly prepared 0.5 M solution (25 mL) of chromium(III) acetate was taken in a flask and placed on a magnetic stirrer. Then 100 mL of aqueous extract was added with stirring at room temperature. After 30 min of stirring, 100 mL of freshly prepared NaOH solution (1 M) was added till its pH was around 12 (Khalaji 2020). The reaction mixture was heated for 60 min at 70 °C to produce the precipitates. It was then cooled to room temperature and filtered through a Whatman filter paper No. 1 to leave behind the precipitates which were rinsed with distilled water 3 times. The precipitates were dried in an oven at 100 °C for two h. The obtained dried material (black, 0.61 g) was ground into a fine powder, transferred into a china dish and kept in a muffle furnace for two h at 700 °C for calcination. The obtained product (0.37 g) of (Cr2O3)aqNa was stored for analysis and further use. % age Yield of (Cr2O3)aqNa NPs = 39.36 %.

The same procedure was followed for treatment of ethanolic extract (100 mL) with 1 M chromium acetate solution (40 mL) in the presence of 1 M freshly prepared NaOH (70 mL). After drying, 5.33 g of black colored material was obtained, whose calcination at 100 °C for two h produced 2.34 g of (Cr2O3)etNa NPs (Khan et al., 2021). % age Yield of (Cr2O3)etNa NPs = 76.97 %.

Fig. 2 (Route B) displays the route for the green synthesis of (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa NPs.

2.5 Cyclic voltammetry (CV) and Galvanostatic Charge-discharge (GCD)

The synthesized NPs were subjected to cyclic voltammetry (CV) and Galvanostatic Charge-discharge (GCD) by a reported procedure (Wyantuti et al., 2015). Cyclic voltammetry was carried out by using an electrochemical workstation. The 6 M KOH solution was used as an electrolyte and three electrode system was employed i.e., reference electrode (Ag/AgCl), the counter electrode (Pt wire) and the working electrode (chromium oxide). The loading density of electrochemical material was 0.1 mg cm−2.

Potassium hydroxide (KOH) is used as an electrolyte material due to its good conductivity. Also, its 6 M concentration (as compared to the 2 M and 4 M solutions) as an electrolyte provides higher concentration of OH− ions and thus facilitates the charge transfer in bulk electrodes (Carmezim and Santos 2017).

The electrode material was prepared by taking a small piece of Ni foam which was washed with ethanol and then with deionized water and subsequently sonicated for 10 min with both the solvents separately. Afterwards, the nickel foam was dried by using a dryer. Then 80 % sample of synthesized NPs, 15 % carbon charcoal, and 5 % binder were ground together in a pestle mortar into fine powder followed by addition of few drops of N-Methyl-2-Pyrrolidone (NMP) to produce a slurry. Finally, the slurry was placed on the nickel foam and dried at 70 °C overnight (Wyantuti et al., 2015).

2.6 Biofilm inhibition assay by microtitre-plate method

Biofilm inhibition evaluations were performed by a microtitre-plate method reported earlier (Anjum et al., 2014; Shahid et al., 2015). The NPs were tested against Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive) and Escherichia coli (Gram-positive). Each well of a sterile 96-well flat-bottomed plastic tissue culture plate was filled with nutrient broth (100 μL), testing solution (100 μL) and bacterial suspension inoculation (20 μL). The wells containing only nutrient broth were taken as negative control. Each plate was covered and incubated aerobically at 37 °C for 24 h. Then there was washing of the contents of each well 3 times with sterile phosphate buffer (220 μL). For removal of non-adherent bacteria, each plate was vigorously shaken. The remaining attached bacteria were fixed with 220 microlitre of 99 % methanol per well; each plate was emptied after 15 min and then dried. Each well was stained with 220 mL of 50 % crystal violet for 5 min followed by removal of excess stain by placing the plate under running tap water. After drying of plates by air, 220 µL of 33 % (v/v) glacial acetic acid was added to each well to resolubilize the dye bound to the adherent cells. A microplate reader (BioTek, USA) was used to measure OD of each well at 630 nm (Qasim et al., 2020). Each test was performed thrice against a bacterium and the results were averaged. The following formula was used to calculate the bacterial growth inhibition (INH %):

2.7 Antibacterial activity by agar well diffusion method

Antibacterial activities of the synthesized NPs were performed by agar well diffusion method (Candan et al., 2003) using ciprofloxacin as a standard positive control against S. aureus (Gram-positive) and E. coli (Gram-positive). A suspension of nutrient agar in distilled water (37 g/L) was prepared and its pH was adjusted to 7 by adding 0.1 N HCl/NaOH. Then there was sterilization of the medium by autoclaving it at 121 °C for 15 min followed by its transfer into the sterilized petri plates. Afterwards, 100 µL of inoculum of a test pathogen (S. aureus and E. coli) was added to each plate, mixed homogenously with the growth medium and then the medium was permitted to solidify. A sterilized borer was used to cut the wells of fixed diameters in the solidified agar. Subsequently, 50 µL of a test sample was poured into a well; ciprofloxacin (as a positive control) was also transferred into a well. A laminar air flow cabinet was used to prepare the plates under aseptic conditions. Finally, there was incubation of the petri plates at 37 °C for 24 h for the bacterial growth. However, this growth was inhibited by the bioactive NPs with the formation of clear zones around them. A vernier calliper was used to measure the diameters of these inhibition zones in millimetres (Mushtaq et al., 2021). The observed results of NPs were compared with those of the standard drug (Zaidan et al., 2005; Mushtaq et al., 2021).

3 Results and discussions

Aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Cassia fistula leaves were treated with chromium acetate to produce (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)et NPs, respectively. For comparison of yield and particle sizes, the same reaction was performed in the presence of NaOH to synthesize (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa NPs with aqueous and ethanolic extracts, respectively of plant leaves. The synthesized NPs were characterized by XRD, FTIR, Raman spectroscopy, SEM, TGA and DSC analyses. They were also subjected to electrochemical investigations and antibacterial activity studies.

3.1 Role of plant material and reaction conditions in green synthesis

Green syntheses require eco-friendly, sustainable and reliable synthetic pathways in order to avoid the production of harmful/unwanted by-products. This goal can be achieved by using natural resources (such as organic systems) and ideal solvent systems. Various biological materials (e.g., e.g., plant extracts, algae, fungi, bacteria etc) can be employed for the green synthesis of NPs; however, the plant medicated synthesis is a rather simple and easy approach for the large scale production of NPs (Singh et al., 2018). The current study also utilizes the leaves extracts of C. fistula for eco-friendly production of chromium oxide NPs (Cr2O3 NPs). The % age yield of the synthesized NPs was decreased in the following order: (Cr2O3)aq > (Cr2O3)etNa > (Cr2O3)et > (Cr2O3)aqNa with 98.10, 76.97, 62.70 and 39.36 %, respectively. Under pure plant conditions (absence of NaOH), the aqueous extract of C. fistula leaves gave superior yield (98.10 %) of (Cr2O3)aq NPs as compared to that [(Cr2O3)et = 62.70 %] with the ethanolic extract. On the other hand, when the same reaction was performed in the presence of sodium hydroxide, the ethanolic leaves extract produced better yield (76.97 %) of Cr2O3)etNa NPs as compared to that [(Cr2O3)aqNa = 39.36 %] with the aqueous extract. Thus, it can be demonstrated that the yield of chromium oxide NPs varies with the nature of plant extract, solvent (water or ethanol) used for plant extraction and biosynthesis, reaction temperature and pH conditions (neutral or basic). Anyhow, it can also be concluded from our studies that both the aqueous and ethanolic extracts of C. fistula leaves act as reducing and capping agents; former gives better reaction with chromium acetate under neutral conditions (absence of NaOH) with pH = 7 whereas latter offered better yield under basic conditions (in presence of NaOH) with pH ∼ 12. Moreover, all the bio-syntheses of Cr2O3 NPs are endothermic because they require an extra energy input (heat) to achieve a reaction temperature of 70 °C for a period of 30 min. According to literature, the morphological parameters (e.g., shapes and sizes) of NPs are modulated by varying the concentrations of chemicals, the reaction conditions (e.g., pH and temperature) (Singh et al., 2018) and plant biodiversity due to the existence of different phytochemicals in various plants (Singh et al., 2018). Since, the leaves of Cassia fistula are good sources of carbohydrates, tannins, oleic, stearic/linoleic acid, sennosides A and B, free rhein, oxyanthraquinones derivatives, isofavoneoxalic acids (Saeed et al., 2020) and many antioxidants including flavonoids, alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics, tannins, cardiac glycosides, saponins, anthocyanosides, steroids, carbohydrates, proteins and phlobatannins (Bahorun et al., 2005; Naseer et al., 2020) so they may provide an excellent support for the fabrication and formation of Cr2O3 NPs. The aqua soluble heterocyclic compounds in leaf broth are mostly responsible for the reduction of chromium ions whereas the synthesized Cr2O3 NPs are stabilized by the presence of biomolecules in leaf broth (Ghotekar et al., 2021).

The investigated green synthetic route is cost effective since it requires only the use of chromium acetate (as main precursor), the leave extracts of C. fistula (a widespread plant) and a solvent; sodium hydroxide may or may not be required. The solvents (water or ethanol) used in this procedure are easily available, among which water is an ideal, cheapest, most commonly accessible and universal solvent on earth. All the NPs have shown good purity as reflected from their characterization (by XRD, IR and Raman spectroscopies and TGA). Moreover, the % yields of the green synthesized NPs are significant; especially the (Cr2O3)aq NPs have shown a surprising yield of 98.10 %. As far as the environmental impacts are concerned, all the synthetic routes in this research work utilize plant material (leaves extracts) as a reducing and capping agent. Since, they do not involve any toxic organic/inorganic dissolving agents and surfactants so they have no harmful effects on the environment, which are associated with the traditional nano-synthetic methods. The reaction schemes of (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)et are especially important and preferred because they do not even involve any standard acid or a base in their syntheses. The use of plant materials for the biosynthesis of Cr2O3 NPs is associated with many environmental, economic, health, and medicinal advantages (Ghotekar et al., 2021). The extraction of plant material (leaves) and nano-syntheses were performed by using water and ethanol solvents due to their different polarities. These solvents are also acceptable for human consumption (Zhang et al., 2007; Waszkowiak and Gliszczyńska-Świgło 2016) and do not introduce any hazardous solvent residues when they are added into the useful products and also do not disturb the quality of food products (Waszkowiak et al., 2014; Waszkowiak and Gliszczyńska-Świgło 2016). Moreover, it is well established that ethanol and water (due to their polar nature) are highly efficient for the extraction of phenolic compounds from a plant material (Mello et al., 2010). The oxygen present in water may also lead to the partial oxidation of synthesized NPs and thus affects their reactivities (Singh et al., 2018). The phytosynthesized Cr2O3 NPs have attracted tremendous usages as antidiabetic, antiviral, antileishmanial, anticancer, antioxidant, antifungal, antibacterial, photocatalytic agents as well as fabrication of microelectronic circuits, fuel cells, solar energy collectors and sensors (Ghotekar et al., 2021).

3.2 Structural properties

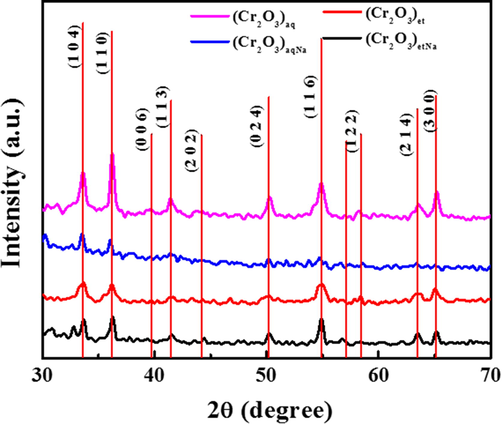

XRD analysis is used to provide information about the crystalline structure and crystallite sizes of the NPs (Hussain et al., 2023). The structural parameters of NPs were determined by using Bruker AXS, D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (XRD). The XRD patterns for the synthesized (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa NPs are compared in Fig. 3 and are in good agreement with the standard JCPDS card number 38-1479 (Almontasser and Parveen, 2020). In (Cr2O3)aq, sharp peaks were observed at 2θ = 33.5°, 36.2° and 54.87°, which correspond to (1 0 4), (1 1 0) and (1 1 6) crystal planes, respectively. (Cr2O3)aqNa have shown two prominent peaks at 2θ = 33.5° and 36.04° for crystal planes of (1 0 4) and (1 1 0), respectively. The three prominent XRD peaks at 2θ = 33.59°, 36.19° and 54.8° in (Cr2O3)et were assigned to (1 0 4), (1 1 0) and (1 1 6), respectively. However, for (Cr2O3)etNa, the sharp XRD peaks at 2θ = 33.6°, 36.2° and 54.8° are associated with the crystal planes of (1 0 4), (1 1 0) and (1 1 6), respectively. The average crystallite size of NPs was determined by using the Scherrer equation (Eq. (1)):

XRD spectra of (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa.

The crystallite sizes of the (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)aqNa, (Cr2O3)et and (Cr2O3)etNa NPs were found to be 18.95, 23.90, 14.85 and 20.22 nm, respectively. They possess the hexagonal crystal structures which are in accordance with the reported literature for Cr2O3 NPs (Jaswal et al., 2014). The smaller crystallite sizes of (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)et as compared to those of (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa clearly depict that the pure green method (in the absence of NaOH) is a successful method for synthesis of small sized/high surfaced chromium(III) oxide NPs as compared to the semi-green method (involving NaOH). The average crystallite sizes (14.85 to 23.90 nm) resemble with those of earlier reported Cr2O3 NPs (Hassan et al., 2019; Kafi-Ahmadi et al., 2022; Shahid et al., 2023).

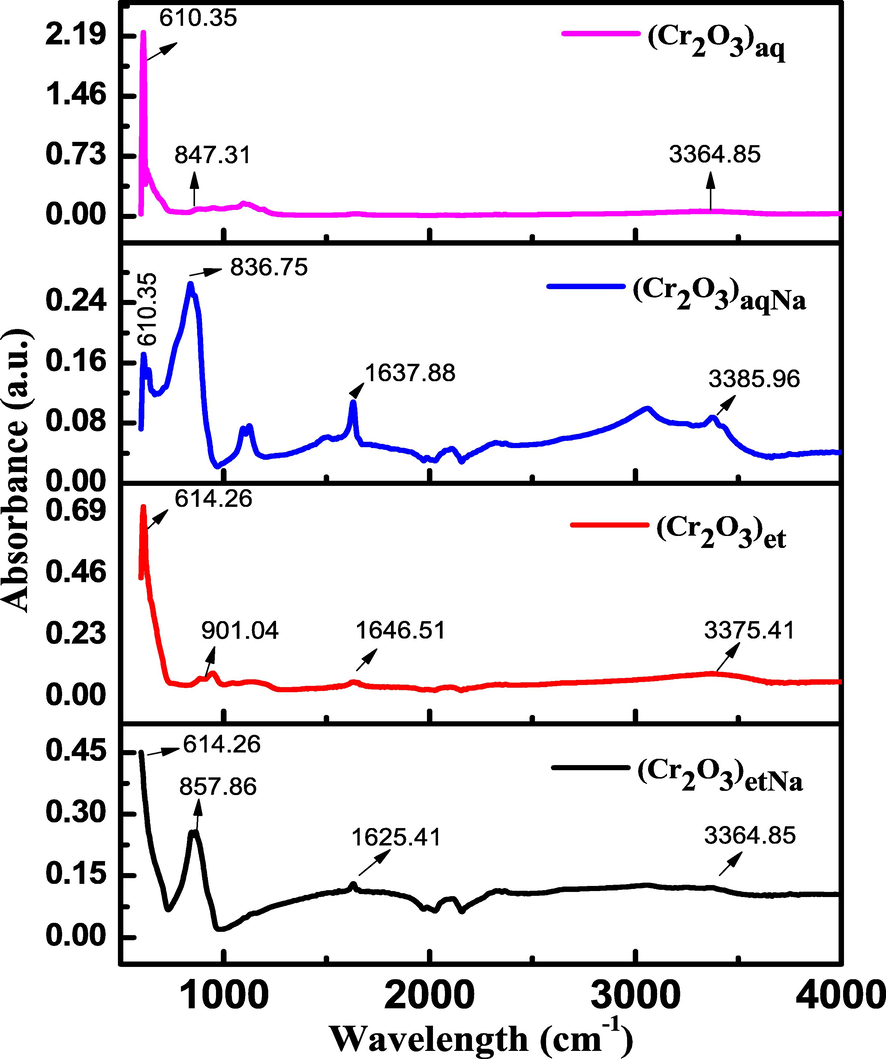

3.3 FTIR spectroscopy

The synthesized NPs were subjected to FTIR analysis in the range of 500–4000 cm−1 by Carry 630 FTIR spectrometer. The obtained FTIR spectra (Fig. 4) have shown many peaks, but the peaks of special interest are those of Cr-O stretching vibrations which appeared at 610.35, 610.35, 614.26 and 614.26 cm−1 in (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)etNa, (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)aqNa, respectively (Madi et al., 2007). The appearance of peaks at 610–614 cm−1 clearly depicts the +3 oxidation state of chromium (Cr+3) in the synthesized NPs because the oxides of chromium in higher oxidation states (Cr+4, Cr+5 and Cr+6) displays vibrations at higher frequencies according to the reported literature (Campbell 1965). Additional peaks for Cr=O were appeared at 836.75–901.04 cm−1 as shoulder bands to the Cr-O peaks (Levason et al., 2014); the earlier studies support the existence of υCrO bands below 1000 cm−1 (Bumajdad et al., 2017). The broad bands at 3364.85–3385.96 cm−1 can be assigned to the stretching vibrations of hydrogen bonded hydroxyl groups of physically adsorbed water molecules in (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)etNa and (Cr2O3)aqNa; the presence of hydroxyl bands was further verified by the presence of weak to medium strength bands at 1625.41–1646 cm−1 owing to O-H bending vibrations (Bumajdad et al., 2017). However, in (Cr2O3)aq, no peak was appeared for either stretching or bending vibrations of OH group indicating the absence of moisture in it. These results are further augmented from the thermogravimetric analysis data (Section 3.6) which clearly supports the evolution of water molecules from (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)etNa and (Cr2O3)aqNa NPs upon increasing of their temperatures.

FTIR spectra of (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa.

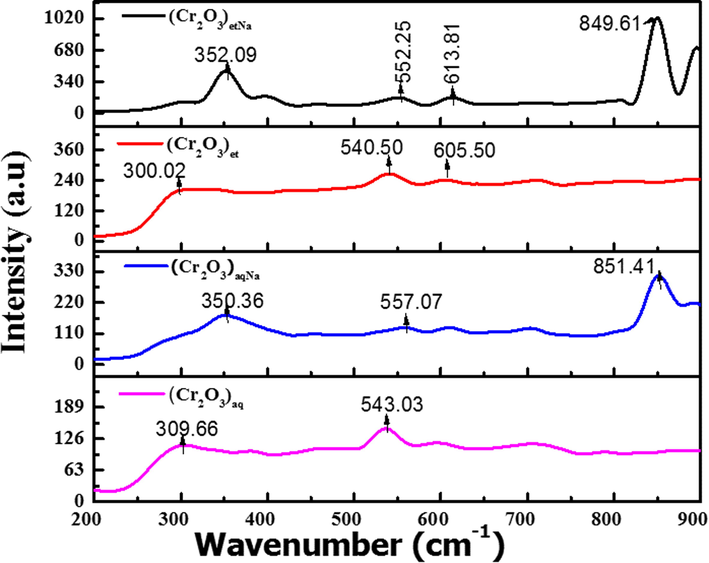

3.4 Raman spectroscopy

The NPs were subjected to Raman spectroscopy by Renishaw in Vis Reflex Raman spectrometer; the obtained spectra are displayed in Fig. 5.

Raman Spectra of (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa.

The vibrational peaks in the ranges of 306.04–350.87, 540.50–557.07 and 602.47–613.81 cm−1 can be assigned to the Raman modes of Cr2O3 NPs according to literature (Brown et al., 1968; Shim et al., 2004; Kikuchi et al., 2005). The Raman peak pattern (Fig. 5) closely resembles to that reported earlier for chromium oxide (Cr2O3) NPs (Mohammadtaheri et al., 2018) and completely supports the findings of XRD analyses (Section 3.2). The strong Cr-O bond is correlated with the highest symmetric stretching frequencies. The vibration peaks (Fig. 5) at 540.50–557.07 cm−1 are owed to A1g modes with rhombohedral Cr2O3 structure and indicate the Cr–O stretching vibrations of Cr3+ ions in octahedral coordination (Larbi et al., 2017). The existence of Cr3+ oxidation state is also verified from FTIR studies (Section 3.3). However, it is important to note that that the narrowness of the A1g peak demonstrates that Cr2O3 has a high degree of crystallinity (Larbi et al., 2017) which is also verified from XRD studies of the investigated samples (Section 3.2). The peaks located in the ranges of 306.04–350.87 and 602.47–613.81 cm−1 can be attributed to Eg vibrational modes (Sone et al., 2016; Larbi et al., 2017). Similar vibrations were reported earlier for α-Cr2O3 NPs (Mohammadtaheri et al., 2018). According to literature, the bulk α-Cr2O3 possesses a corundum structure with the D6 3d group. The chromium atoms belong to C3 site symmetry whereas the O atoms lie on sites with C2 symmetry. The 2A1g, 2A1u, 3A2g, 2A2U, 5Eg and 4Eu vibrations are the corresponding optical modes in the crystal, out of which only 2A1g and 5Eg vibrations are Raman active (Sone et al., 2016). Moreover, chromium (III) oxide is crystallized in the rhombohedral structure and is comprised of hexagonal close packed array of O2− ions (at Wyckoff site 18e) with 2/3 of the interstitial octahedral sites occupied by Cr3+ cations (at Wcykoff site 12c) (Larbi et al., 2017).

3.5 UV–Visible Spectroscopy

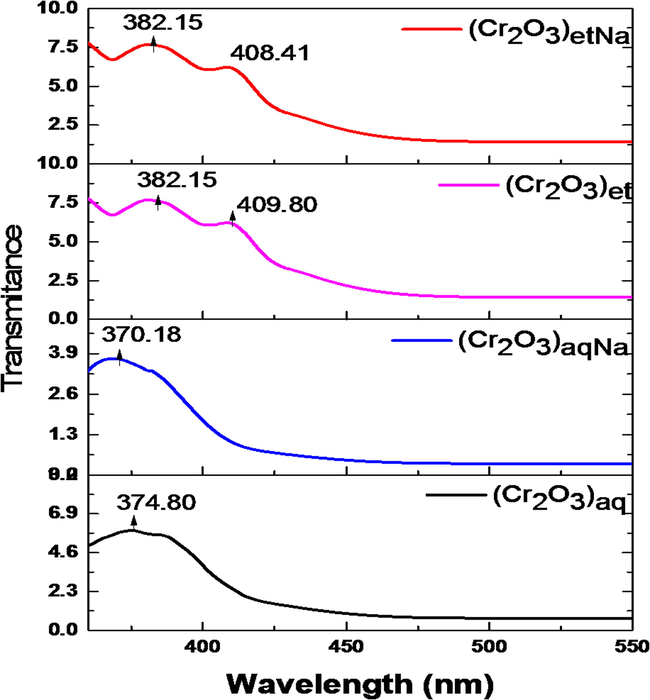

The synthesized NPs were subjected to UV–Visible spectroscopy in the range of 100 to 1000 nm by SPECORD 200 PLUS spectrometer; the corresponding spectra are shown in Fig. 6. The UV–Visible spectra of (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)etNa, (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)aqNa have shown the absorbance peaks at 382.15, 382.15, 374.80 and 370.18 nm, respectively which correspond to the band gap values of 4.26, 4.40, 4.06 and 4.11 eV, respectively (Kamari et al., 2019). The band gaps of (Cr2O3)et (4.26 eV) and (Cr2O3)aq (4.06 eV) were increased in their counterparts (Cr2O3)etNa (4.40 eV) and (Cr2O3)aqNa (4.11 eV), respectively as the latter two NPs were synthesized under basic conditions (presence of NaOH). The results thus demonstrate that the involvement of NaOH in the green synthetic path has increased the band gaps of the resultant Cr2O3 NPs. The appearance of two additional peaks at 409.80 nm and 408.41 nm in the spectra of (Cr2O3)et and (Cr2O3)etNa, respectively (Fig. 6) may also be attributed to the chromium oxide NPs as reported in literature (Ramesh et al., 2012b; Rakesh et al., 2013).

UV–Visible spectra of (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa.

3.6 Scanning electron microscope (SEM)

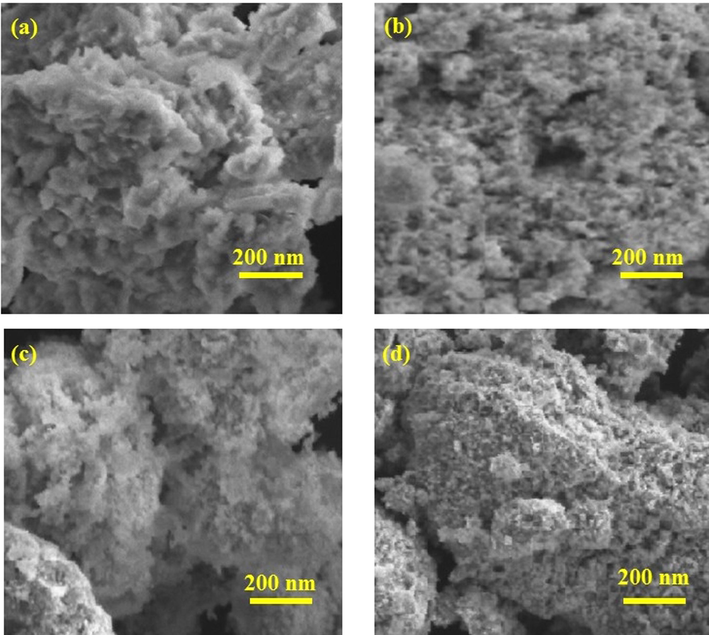

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) was performed by Hitachi S4800 to investigate the morphology of the synthesized NPs. Fig. 7 displays the SEM images of (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa NPs. It was observed that the (Cr2O3)aq NPs have a crystalline structure with a high degree of agglomeration between fine particles (Jaswal et al., 2014). Agglomeration of NPs results in a lowering of surface free energy by enhancing their sizes and reducing their surface area. Agglomeration occurs due to adhesion of NPs to each other by weak forces leading to (sub) micronized entities. The NP aggregates are produced due to the formation of metallic or covalent bonds that are unable to be disrupted easily (Balbus et al., 2007; Gosens et al., 2010). However, the SEM images of (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa NPs demonstrate the spherical shapes with porous structures (Ashika et al., 2022). The same kinds of results were also supported from XRD spectra which depicted that the peaks in (Cr2O3)aq were sharper as compared to those of (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa NPs.

SEM images (a, b, c, d) of (Cr2O3)aqNa, (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)et, and (Cr2O3)etNa, respectively.

3.7 Thermogravimetric analysis

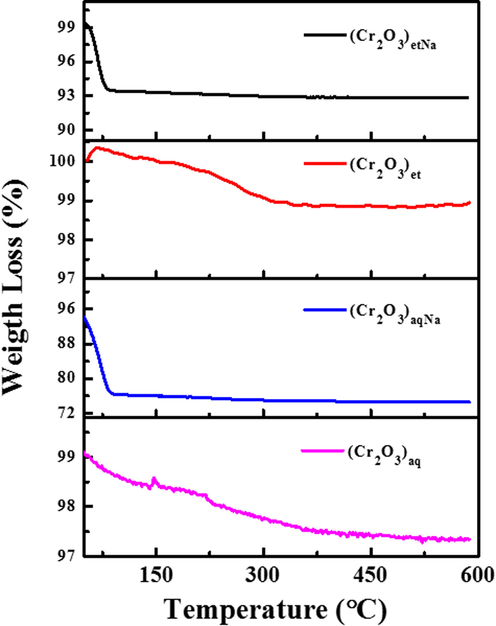

Thermogravimetric analyses were carried out by SDT (Q600) thermal analyzer (TA Instruments, USA) under nitrogen atmosphere at the heating rate of 20 °C min−1 to know about the thermal stabilities, percentage purity and extent of degradations (Hussain et al., 2015b) of the synthesized NPs. The obtained thermograms (Fig. 8) clearly show that (Cr2O3)et and (Cr2O3)aq NPs are comparatively more stable to heat as compared to their counterparts i.e., (Cr2O3)etNa and (Cr2O3)aqNa which were synthesized under basic conditions. The (Cr2O3)etNa and (Cr2O3)aqNa have shown the mass losses of 7 % and 24 %, respectively before 100 °C; the loss of mass before reaching the temperature of 110 °C evidently depicts the evolution of moisture content from these NPs (Zoromba et al., 2017). After 110 °C, there is no further change in their masses up to a temperature of 600 °C indicating their structural stabilities. The (Cr2O3)et and (Cr2O3)aq NPs have shown only mass losses up to 1.1 % and 1.6 %, respectively before reaching the temperatures of 600 °C. The loss of 1.1% mass before reaching the temperature of 330 °C in (Cr2O3)et may be owed to the evolution of coordinated water molecules which are strongly held in its crystal lattice. FTIR studies (Section 3.2) also verify the existence of water molecules in (Cr2O3)etNa, (Cr2O3)et and (Cr2O3)aqNa NPs. The results generally indicate that the synthesized NPs have some moisture content or coordinated water which is lost upon an increase of temperature. So, the investigated NPs possess significant thermal stabilities up to 600 °C without losing their original structural integrities (Cr2O3) and may be used under high-temperature conditions without any thermal degradations.

TGA curves (thermograms) of (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa.

3.8 Differential scanning calorimetry

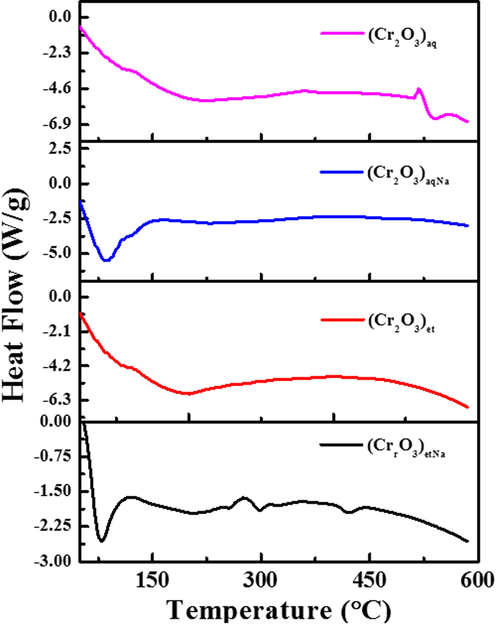

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed by SDT (Q600) thermal analyzer (TA Instruments, USA) under nitrogen atmosphere at the heating rate of 20 °C min−1 to support the results obtained from TGA analysis. The obtained results are shown in Fig. 9. In (Cr2O3)etNa, an endothermic process was started at 43 °C and continued till 80 °C; then an exothermic peak was observed at 116 °C which demonstrated the evaporation of water molecules from NPs, then again endothermic process was started. In (Cr2O3)et, an endothermic peak was shown at 202 °C. Then exothermic process was continued till 450 °C followed by absorption of heat again. The DSC behavior of (Cr2O3)aq almost resembles to that of (Cr2O3)et NPs; both these NPs also show approximately the uniform behavior in TGA curves (Section 3.6). However, (Cr2O3)aqNa NPs have shown endothermic peak at 83 °C and a sharp exothermic peak till 133 °C and again endothermic process was started.

DSC analysis of (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa.

3.9 Electrochemical potential

3.9.1 Cyclic voltammetry (CV)

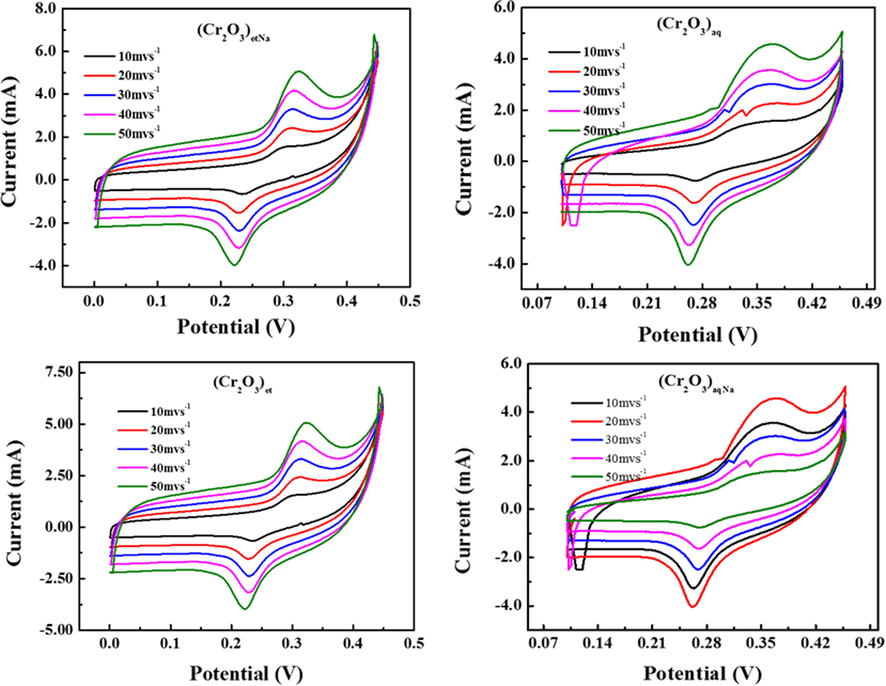

The cyclic voltammetry (CV) experiments were carried out by Galvanostat/Potentiostat (CS300 model, China) in order to observe the electrochemical behavior of (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)etNa and (Cr2O3)aqNa NPs. The CV measurements were taken at scan rates of 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 mV s−1 in the potential range of 0.05 V to 0.5 V. The obtained voltammograms of the investigated NPs are shown in Fig. 10.

CV graphs of (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)etN and (Cr2O3)aqNa NPs.

The cyclic voltammograms have shown the clear oxidation–reduction peaks of NPs, which confirmed their redox behaviors. From all the CV curves, it was observed that the reduction peak potential varies a little in between the range 0.2 V–0.28 V. Moreover, the reduction peaks in all the samples exhibited similar behavior but the oxidation peaks were not similar for (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)aqNa NPs. However, the potential range for oxidation peaks in all samples was found to be 0.29–0.4 V. The oxidation peaks of (Cr2O3)aq and (Cr2O3)aqNa NPs have shown a large area under their respective curves, which displays a large value of specific capacitance for both these samples. The CV curves (Fig. 10) of all the samples have clearly shown the redox peaks, which indicates that the process of charging is reversible in all the synthesized chromium oxide NPs. From the CV curves, we can fix the value of GCD potential. The starting potential for all the samples was fixed to be 0 V but the end potential value varies a little in accordance with the oxidation peaks as shown in Fig. 11, which effects the value of specific capacitance, energy density and power density as discussed in next Section (3.8.2).

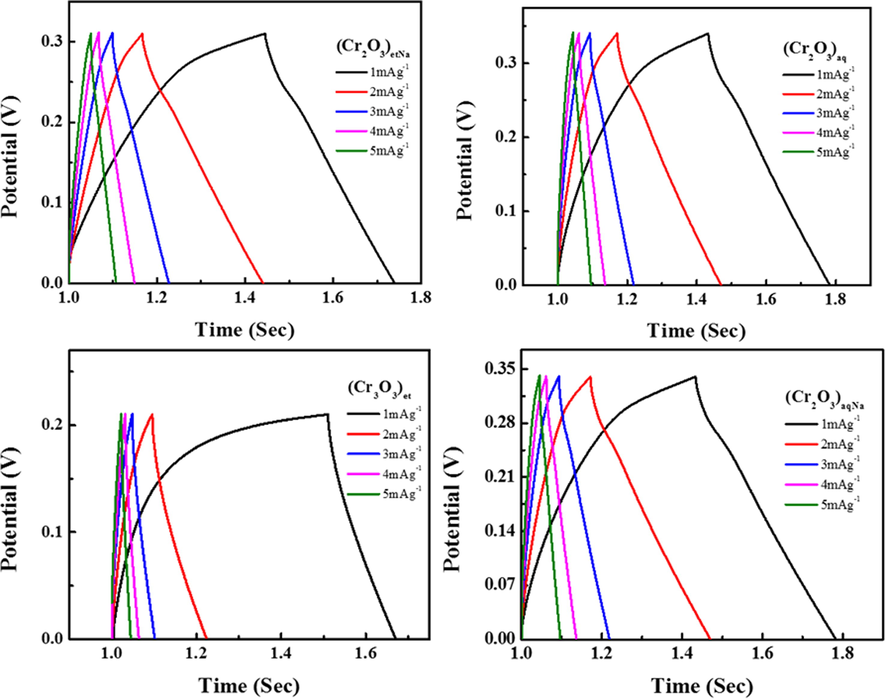

GCD graphs of (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)etN and (Cr2O3)aqNa NPs.

3.9.2 Galvanostatic Charge-discharge (GCD)

Galvanostatic Charge-discharge (GCD) cycling was performed by Galvanostat/Potentiostat (CS300 model, China) in the potential range of 0.0 to 0.35 V at different current densities ranging from 1 A g−1 to 5 A g−1. The GCD curves of the synthesized NPs (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)etNa and (Cr2O3)aqNa are shown in Fig. 11. The charging potential range for (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)etNa and (Cr2O3)aqNa were set to be 0–0.31, 0–0.35, 0–0.22 and 0–0.34 V, respectively. The specific capacitance was calculated using the GCD curves by using Equation (2).

The GCD curves of (Cr2O3)et NPs (Fig. 11) at different current densities show its capacitor nature. The GCD curves of other three synthesized NPs (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)etNa and (Cr2O3)aqNa show pseudo-capacitor nature. The (Cr2O3)aqNa NPs have demonstrated the highest specific capacitance (454.54 mAhg−1) at 1 mAg−1 current density, which was much greater as compared to that reported in literature (Shafi et al., 2021). It can be attributed to the porous structures as confirmed from the XRD analysis and SEM micrographs. The specific capacitances of the other synthesized NPs were less as compared to that of (Cr2O3)aqNa; they were found to be 313.90, 285.71 and 282.35 mAhg−1 for (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)etNa and (Cr2O3)et, respectively. All the values of specific capacitances were calculated from the GCD graph, which was plotted at a current density 1 mAg−1. The energy density and power density were also calculated for all the samples (Table 1). The GCD curves (Fig. 11) clarify that the discharging time of NPs is greater than their charge timings, which demonstrates that NPs are good materials for energy storage applications.

Sample

Current density

mA/g−1

Specific Capacitance

mAh/gEnergy Density

WKg−1

Power Density

W/Kg

(Cr2O3)aqNa

1

454.54

16.69

417.25

(Cr2O3)aq

1

313.90

11.52

288

(Cr2O3)etNa

1

285.71

10.48

262

(Cr2O3)et

1

282.35

10.36

259

3.10 Antibacterial activity

The synthesized NPs were tested for their antibacterial potential against Escherichia coli (gram negative) and Staphylococcus aureus (gram positive) by agar well diffusion method (Candan et al., 2003). Ciprofloxacin was used as a positive control. A vernier caliper was used to measure the zones of inhibition in mm whereas the biofilm inhibitions were measured in %age. The antibacterial activity data are shown in Table 2.

Sample

Biofilm inhibition (%)

Inhibition zones (mm)

E. coli

S. aureus

E. coli

S. aureus

(Cr2O3)et

41

27

16

5

(Cr2O3)etNa

66

49

13

14

(Cr2O3)aq

53

44

14

3

(Cr2O3)aqNa

44

27

17

5

Ciprofloxacin

53

47

37

40

Sr. No.

Plant extract used

Chromium salt solution used

Crystallite size (By XRD)

Shape of NPs

(By SEM analysis)

Applications tested

Reference

1

Callistemon viminalis(Bottle Brush)

flowersChromium nitrate

15.06–17.34 nmRhombohedral

Antibacterial, cytotoxicity, enzymatic, hemolytic, DPPH radical scavenging, reducing power and total antioxidant potential

(Hassan et al., 2019)

2

Callostemon viminalis fresh red flowers

Chromium nitrate

∼92.2 nmCubic-like platelets with sharp edges with a non-negligible degree of polydispersity

–

(Sone et al., 2016)

3

Cannabis sativa leaves

Chromium nitrate

85–90 nmPolydispersity, Irregular

Anti-cancer in HepG2 cell lines and corrosion inhibitory activity

(Sharma and Sharma 2021)

4

Hyphaene thebaica fruit

Chromium nitrate

25–38 nm

Cube like morphology, few NPs were quasi-spherical

Antifungal, antibacterial, antioxidant, cytotoxicity,

inhibition of polio virus, hemocompatibility and enzyme inhibition(Ahmed Mohamed et al., 2020)

5

Nephelium lappaceum fruit peels

Chromium nitrate

55.92 nm

Rhombohedral polycrystalline nature, spherical shapes

Cell viability and cytotoxicity analyses by using MTT assay of human breast cancer cell line

(Isacfranklin et al., 2020)

6

Rhamnus virgate leaves

Chromium nitrate

∼28 nm

Single and pure phase hexagonal crystalline

Cytotoxicity potentials against HepG2 and HUH-7 cancer cell lines, antioxidants, biostatic, alpha-amylase and protein kinase inhibition

(Iqbal et al., 2020b)

7

Ipomoea batatas (peels of sweet potatoes)

Chromium nitrate

3.44 nm (annealed at 300OC), 17 to 50 nm (annealed at 500OC), 93.5 nm (annealed at 700OC)

Agglomerated (annealed at 300OC),Rhomboid, elongated nanorods and highly agglomerated

(annealed at 500OC), agglomerated (annealed at 700OC)Density functional theory (DFT) for optimum structure, electronic and magnetic properties of antiferromagnetically ordered Cr2O3

(Sackey et al., 2021)

8

Zingiber officinal extract

Chromium nitrate

14 nm

Mixture of rods and particles

Magnetic properties, catalytic potential for the synthesis of polysubstituted imidazoles

(Kafi-Ahmadi et al., 2022)

9

Melia azedarach fruits

Potassium dichromate

–

nearly spherical and few NPs were agglomerated

antibacterial effect

(Kotb et al., 2020)

10

Artemisia herba-alba leaves

Potassium dichromate

32.35 nm as average of 10.37 number of particles counted

Nearly spherical, few NPs agglomerated

Antibacterial effect

(Kotb et al., 2020)

11

Mukia maderaspatana edible portion

Potassium dichromate

65 nm

–

Antibacterial Study

(Rakesh et al., 2013)

12

Apis mellifera

honeyPotassium dichromate

24 nm

Irregular rocky clusters

anti-bacterial, anti-biofilm, anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory abilities

(Shahid et al., 2023)

13

Tridax procumbens leaves

Potassium dichromate

80–100 nm

Look like strips with rough surface

Antibacterial activity on Escherichia coli

(Ramesh et al., 2012a)

14

Roselle extract

Chromium(III) chloride

89.83 nm

Spherical or semispherical

Antibacterial agent for human pathogenic bacteria

(Aziz et al., 2022)

15

Opuntia Ficus indica (cactus) leaves

Chromium(III) chloride

45 to 55 nm

Hexagonal

Optical properties

(Tsegay et al., 2021)

16

Abutilon indicum (L.) Sweet leaves

Chromium sulphate

17 to 42 nm

Spherical morphology

Antibacterial, anticancer (against MCF-7 cancer cells) and antioxidant potential

(Khan et al., 2021)

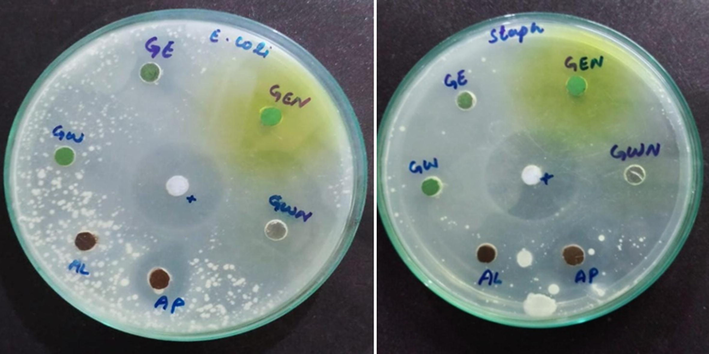

The obtained results are fascinating (Table 2); the biofilm inhibitions of the synthesized NPs (Cr2O3)aq, (Cr2O3)et, (Cr2O3)aqNa and (Cr2O3)etNa were comparable to those of the standard antibacterial drug (ciprofloxacin). The NPs have shown fantastic bacterial inhibitions of 41–66 % and 27–49 % against E. coli and S. aureus, respectively as compared to those (53 % against E. coli and 47 % against S. aureus) of ciprofloxacin. The (Cr2O3)etNa was most potent among all the NPs with 66 % and 49 % inhibitions of the E. coli and S. aureus biofilms, respectively; it has shown even higher biofilm inhibitions as compared to those of the standard drug against both the test bacterial strains. Antibacterial activity evaluations (Table 2, Fig. 12) by agar well diffusion method have shown that the prepared NPs possessed comparatively higher inhibition zones (13–17 mm) against Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli) as compared to those (3–14 mm) of Gram-positive strain (S. aureus). However, the sizes of inhibition zones of the tested NPs were found smaller as compared to those of ciprofloxacin (37 mm and 40 mm against E. coli and S. aureus, respectively). It is worth mentioning that synthesized NPs display significantly better antimicrobial potential by biofilm inhibition method as compared to those by agar well diffusion method.

The inhibition zones (mm) of (Cr2O3)aq = GW, (Cr2O3)aqNa = GWN, (Cr2O3)et = GE, (Cr2O3)etNa = GEN against E. Coli (left) and S. aureus (right) in agar well diffusion method.

Although, it is highly difficult to compare the results of the antimicrobial screening with those reported earlier because of the different methodology and strains assayed (Hussain et al., 2015b); yet, significant antibacterial potential of Cr2O3 NPs has been observed in the investigated work. Khan et al., 2021 described the green synthesized Cr2O3 NPs as promising candidates for future biomedical applications and attributed their enhanced biological activities to the synergetic effect (physical properties and adsorbed phytomolecules on their surface) (Khan et al., 2021). Cr2O3 NPs were reported as effective bactericided against human pathogenic bacteria (Aziz et al., 2022) including E. coli (Ramesh et al., 2012; Rakesh et al., 2013) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (Shahid et al., 2023). Hassan et al., 2019 reported a dose-dependent antimicrobial potential of the α-Cr2O3 NPs; there was inhibition of all the tested bacterial strains (S. aureus, Citrobacter, P. vulgaris, K. pneumoniae, V. cholera and C. sakazakii) up to the 50 μg/ml (MIC) concentration of Cr2O3 NPs (Hassan et al., 2019). Mohamed et al., observed the broad-spectrum and dose-dependent antimicrobial activities of Cr2O3 NPs against the bacterial (Staphylococcus epidermidis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, E. coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa & Bacillus subtilis) and the fungal (Mucor sp., Aspergillus fumigates, Fusarium solani, Aspergillus flavus & Aspergillus niger) strains (Ahmed Mohamed et al., 2020). In another study, Cr2O3 NPs have shown promising antibacterial potential against the tested pathogen (E. amylovora). Their colloidal solution up to a concentration of 100 ppm was found effective as a disinfectant for plant cells but its higher concentration also inhibited the cells growth of plant. However, the use of its concentration more than 100 ppm against E. amylovora fire blight bacterium can decontaminate in vitro infected callus cells in pear plants (Kotb et al., 2020).

3.11 Comparison of the investigated work with the previous studies

Green syntheses of chromium oxide NPs have been reported with numerous plant extracts. Table 2 displays the synthetic conditions and properties of Cr2O3 NPs which were synthesized from numerous plant extracts. According to literature, the morphological properties of the synthesized NPs can be varied by controlling various parameters such as reaction temperature (Elzoghby et al., 2021), reaction time (Prathna et al., 2011), reactant concentration (Chandran et al., 2006) and pH (Dubey et al., 2010). These factors also play a crucial role in optimizing the yield of metallic NPs through biological means (Zhang et al., 2020). So, the Cr2O3 have been reported with various morphologies (rhombohedral, cubic, spherical, rod-like, strip-like, quasi-spherical, semi-spherical, hexagonal, agglomerated, irregular rocky clusters) and crystallite sizes (3.44–100 nm) depending upon the reaction conditions and nature of plant material used for biosynthesis (Table 3).

There were still no reports on the green synthesis of chromium oxide NPs with Cassia fistula leaves. Moreover, the earlier studies (Table 3) had utilized the chromium nitrate/chromium sulfate/chromium(III) chloride/potassium dichromate as a metal salt precursor in their biosynthetic routes but no plant-mediated synthesis with chromium acetate solution has been reported yet. Current study reports the synthesis of Cr2O3 NPs by the treatment of chromium acetate solution with an aqueous/ethanolic extract of C. fistula leaves as a reducing and capping agent. We have also compared the yield and properties of NPs produced in the absence and presence of basic reaction conditions. Moreover, the previous studies were focused on the evaluation of antibacterial, antifungal, anti-cancer, antioxidant, cytotoxicity, hemolytic, enzymatic inhibition, inhibition of polio virus, hemocompatibility, radical scavenging, reducing power, anti-corrosion, catalytic and optical properties of green synthesized Cr2O3 NPs (Table 3); only one theoretical study (DFT) on their electronic properties was reported (Sackey et al., 2021). In the current study, we have performed the practical experiments to know about the electrochemical characteristics (CV & GCD) of green synthesized Cr2O3 NPs. The Cr2O3 NPs were produced in good yield and possessed the crystallite sizes of 14.85 to 23.90 nm, rhombohedral structures, high degree of agglomeration and existence of Cr3+ ions in octahedral coordination. They have shown band gaps in the range of 4.06–4.40 eV and good thermal stabilities. Their reversible behavior and good discharging time (as compared to the charging time) may enable their utilization in energy storage applications. Moreover, their biofilm inhibitions were comparable to those of the standard antibacterial drug (ciprofloxacin); the activity of (Cr2O3)etNa was found even superior to that of ciprofloxacin. The NPs were potentially more active against E. coli (Gram-negative) as compared to those against S. aureus (Gram-positive).

4 Conclusions

Chromium oxide NPs were synthesized by treating chromium acetate solution with aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Cassia fistulaleaves as the reducing agent as well stabilizing agent. However, when the same nano-syntheses were performed in the presence of sodium hydroxide, large sized NPs were produced with lower %age yield. The synthesized NPs possessed hexagonal crystal structures and crystallite sizes of 14.85 to 23.90 nm, with the lowest size (14.85 nm) possessed by (Cr2O3)et. There were A1g vibration modes (540.50–557.07 cm−1) with rhombohedral Cr2O3 structure, high degree of crystallinity and Cr3+ ions in octahedral coordination whereas Eg vibration modes were displayed at 306.04–350.87 cm−1 and 602.47–613.81 cm−1. The NPs synthesized with ethanolic extracts have shown smaller band gaps (3.02 & 3.03 eV) as compared to those (3.29 and 3.24 eV) produced with aqueous extracts. They existed in the spherical forms with a high degree of agglomeration between fine particles and demonstrated good thermal stabilities with their possible uses up to 600 °C without any structural degradation. The Cr2O3 NPs have displayed clear oxidation reduction peaks and demonstrated their reversible redox behavior with their possible utilization in batteries. Their discharging time was greater than charging time which indicated that NPs are good material for energy storage applications. The biofilm inhibitions of the synthesized NPs were comparable to those of the standard antibacterial drug (ciprofloxacin); the activity of (Cr2O3)etNa was found even better than that of ciprofloxacin. The NPs were found more active against E. coli (Gram-negative) as compared to those against S. aureus (Gram-positive).

Funding

This research was funded by Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R124), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2023R124), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Green bio-assisted synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation of biocompatible ZnO NPs synthesized from different tissues of milk thistle (Silybum marianum) Nanomaterials. 2019;9:1171.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phyto-fabricated Cr2O3 nanoparticle for multifunctional biomedical applications. Nanomedicine.. 2020;15:1653-1669.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanistic investigation of toxicity of chromium oxide nanoparticles in murine fibrosarcoma cells. Int. J. Nanomed.. 2016;11:1253.

- [Google Scholar]

- Almontasser, A., Parveen, A., 2020. Preparation and characterization of chromium oxide nanoparticles. AIP Conference Proceedings, AIP Publishing LLC.

- Exploration of nutraceutical potential of herbal oil formulated from parasitic plant. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement. Altern. Med.. 2014;11:78-86.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cost effective one-pot synthesis approach for the formation of pure Cr2O3 nanocrystalline materials. Results Chem.. 2022;4:100594

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis and characterization of Cr2O3 nanoparticle prepared by using CrCl3. 6H2O and Roselle extract. AIP Conference Proceedings, AIP Publishing LLC; 2022.

- Effect of annealing temperature on antimicrobial and structural properties of bio-synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using flower extract of Anchusa italica. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol.. 2016;161:441-449.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical constituents of Cassia fistula. Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2005;4:1530-1540.

- [Google Scholar]

- Meeting report: hazard assessment for nanoparticles—report from an interdisciplinary workshop. Environ. Health Perspect.. 2007;115:1654-1659.

- [Google Scholar]

- Traditional medicinal uses, phytochemical profile and pharmacological activities of Cassia fistula Linn. Int. Res. J. Biol. Sci.. 2012;1:79-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chromium oxyselenide solid solutions from the atmospheric pressure chemical vapour deposition of chromyl chloride and diethylselenide. J. Mater. Chem.. 2008;18:1667-1673.

- [Google Scholar]

- The infrared and Raman spectra of chromium (III) oxide. Spectrochim. Acta A: Mol. Spectrosc.. 1968;24:965-968.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of biocompatible nanosilica on green stabilization of subgrade soil. Sci. Rep.. 2019;9:15147.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-noble, efficient catalyst of unsupported α-Cr2O3 nanoparticles for low temperature CO Oxidation. Sci. Rep.. 2017;7:14788.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vibrational frequencies of the chromium-oxygen bond and the oxidation state of chromium. Spectrochim. Acta. 1965;21:851-852.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of the essential oil and methanol extracts of Achillea millefolium subsp. millefolium Afan. (Asteraceae) J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2003;87:215-220.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrolytes in Metal Oxide Supercapacitors. Metal Oxides Supercapacitors. 2017:49-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of gold nanotriangles and silver nanoparticles using Aloevera plant extract. Biotechnol. Prog.. 2006;22:577-583.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of nanomaterials. Synthesis of inorganic nanomaterials. Elsevier; 2018. p. :169-184.

- Tansy fruit mediated greener synthesis of silver and gold nanoparticles. Process Biochem.. 2010;45:1065-1071.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of polyamide-based nanocomposites using green-synthesized chromium and copper oxides nanoparticles for the sorption of uranium from aqueous solution. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021:106755.

- [Google Scholar]

- Single-step synthesis of carbon encapsulated magnetic nanoparticles in arc plasma and potential biomedical applications. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2018;509:414-421.

- [Google Scholar]

- Environmentally friendly synthesis of Cr2O3 nanoparticles: characterization, applications and future perspective─ a review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng.. 2021;3:100089

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of agglomeration state of nano-and submicron sized gold particles on pulmonary inflammation. Part. Fibre Toxicol.. 2010;7:1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cu2O nanoparticle-catalyzed tandem reactions for the synthesis of robust polybenzoxazole. Nanoscale.. 2022;14:6162-6170.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physiochemical properties and novel biological applications of Callistemon viminalis-mediated α-Cr2O3 nanoparticles. Appl. Organomet. Chem.. 2019;33:e5041.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review on gold nanoparticles (GNPs) and their advancement in cancer therapy. Int. J. Nanomater., Nanotechnol. Nanomed.. 2021;7:019-025.

- [Google Scholar]

- Heterobimetallic complexes containing Sn (IV) and Pd (II) with 4-(2-Hydroxyethyl) piperazine-1-carbodithioic acid: Synthesis, characterization and biological activities. Cogent Chem.. 2015;1:1029038.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and spectroscopic and thermogravimetric characterization of heterobimetallic complexes with Sn (IV) and Pd (II); DNA binding, alkaline phosphatase inhibition and biological activity studies. J. Coord. Chem.. 2015;68:662-677.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of nickel oxide nanoparticles using Acacia nilotica leaf extracts and investigation of their electrochemical and biological properties. J. Taibah Univ. Sci.. 2023;17:2170162.

- [Google Scholar]

- Liquid crystal alignment at low temperatures in flexible liquid crystal displays. J. Electrochem. Soc.. 2010;157:J351.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recycling of lead from lead acid battery to form composite material as an anode for low temperature solid oxide fuel cell. Mater. Today Energy. 2020;16:100418

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile green synthesis approach for the production of chromium oxide nanoparticles and their different in vitro biological activities. Microsc. Res. Tech.. 2020;83:706-719.

- [Google Scholar]

- Single-phase Cr2O3 nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Ceram. Int.. 2020;46:19890-19895.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of chromium oxide nanoparticles. Orient. J. Chem.. 2014;30:559-566.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of nanoparticles derived from chitosan-based biopolymer; their photocatalytic and anti-termite potential. Digest J. Nanomater. Biostruct. (DJNB).. 2021;16:1607-1618.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microwave-assisted preparation of polysubstituted imidazoles using Zingiber extract synthesized green Cr2O3 nanoparticles. Sci. Rep.. 2022;12:19942.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive study on morphological, structural and optical properties of Cr2O3 nanoparticle and its antibacterial activities. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron.. 2019;30:8035-8046.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis: An eco-friendly route for the synthesis of iron oxide nanoparticles. Front. Nanotechnol.. 2021;3:47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Toward Organosulfur Pollutants. Sci. Rep.. 2019;9:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cr2O3 Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, and Magnetic Properties. Nanochem. Res.. 2020;5:148-153.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of chromium oxide nanoparticles for antibacterial, antioxidant anticancer, and biocompatibility activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2021;22:502.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of defects on quantum yield in blue emitting photoluminescent nitrogen doped graphene quantum dots. J. Appl. Phys.. 2017;122:145107

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of sulfur related defects in graphene quantum dots for tuning photoluminescence and high quantum yield. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2018;449:363-370.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thermal effect of sulfur doping for luminescent graphene quantum dots. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol.. 2018;7:M29-M34.

- [Google Scholar]

- An efficient pseudocapacitor electrode material with co-doping of iron (II) and sulfur in luminescent graphene quantum dots. Diam. Relat. Mater.. 2020;107:107913

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of Nb-doped strontium cobaltite@ GQD electrodes for high performance supercapacitors. J. Storage Mater.. 2022;55:105388

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of luminescent graphene quantum dots from biomass waste materials for energy-related applications—An overview. Energy Storage 2022:e390.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-destructive rapid analysis discriminating between chromium (VI) and chromium (III) oxides in electrical and electronic equipment using Raman spectroscopy. Anal. Sci.. 2005;21:197-198.

- [Google Scholar]

- Plant extract assisted eco-benevolent synthesis of selenium nanoparticles-a review on plant parts involved, characterization and their recent applications. J. Chem. Rev.. 2020;2:157-168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of chromium nanoparticles by aqueous extract of Melia azedarach, Artemisia herba-alba and bacteria fragments against Erwinia amylovora. Asian J. Biotechnol. Bioresour. Technol.. 2020;6:22-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Intrinsic catalytic structure of gold nanoparticles supported on TiO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2012;51:7729-7733.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural, optical and vibrational properties of Cr2O3 with ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic order: a combined experimental and density functional theory study. J. Magn. Magn. Mater.. 2017;444:16-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, properties, and structures of chromium (VI) and chromium (V) complexes with heterocyclic nitrogen Ligands. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem.. 2014;640:35-39.

- [Google Scholar]

- Stabilizing hard magnetic SmCo5 nanoparticles by N-doped graphitic carbon layer. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2020;142:8440-8446.

- [Google Scholar]

- Madi, C., Tabbal, M., Christidis, T., et al., 2007. Microstructural characterization of chromium oxide thin films grown by remote plasma assisted pulsed laser deposition. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser., IOP Publishing.

- Concentration of flavonoids and phenolic compounds in aqueous and ethanolic propolis extracts through nanofiltration. J. Food Eng.. 2010;96:533-539.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of deposition parameters on the structure and mechanical properties of chromium oxide coatings deposited by reactive magnetron sputtering. Coatings.. 2018;8:111.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of nanosilver particles from plants extract. Int. J. Agric., Environ. Biores.. 2022;7

- [Google Scholar]

- The Role of Nanoparticles in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Diseases. Sci. Inquiry Rev.. 2020;4:14-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antimicrobial, antioxidant and enzyme inhibition roles of polar and non-polar extracts of Clitoria ternatea seeds. JAPS: J. Animal Plant Sci.. 2021;31

- [Google Scholar]

- Green route to synthesize Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles using leaf extracts of Cassia fistula and Melia azadarach and their antibacterial potential. Sci. Rep. 2020:10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetic evolution studies of silver nanoparticles in a bio-based green synthesis process. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp.. 2011;377:212-216.

- [Google Scholar]

- Qasim, N., Shahid, M., Yousaf, F., et al., 2020. Therapeutic potential of selected varieties of phoenix Dactylifera L. against microbial biofilm and free radical damage to DNA. Dose-Response 18, 1559325820962609.

- Synthesis of chromium (III) oxide nanoparticles by electrochemical method and Mukia maderaspatana plant extract, characterization, KMnO4 decomposition and antibacterial study. Modern Res. Catal.. 2013;2:127-135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of Cr2O3 nanoparticles using Tridax procumbens leaf extract and its antibacterial activity on Escherichia coli. Curr. Nanosci.. 2012;8:603-607.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activity of Cr2O3 nanoparticles against E. coli; reduction of chromate ions by Arachis hypogaea leaves. Arch. Appl. Sci. Res.. 2012;4:1894-1900.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic effects of combinatorial chitosan and polyphenol biomolecules on enhanced antibacterial activity of biofunctionalized silver nanoparticles. Sci. Rep.. 2020;10:1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bio-synthesised black α-Cr2O3 nanoparticles; experimental analysis and density function theory calculations. J. Alloy. Compd.. 2021;850:156671

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical Composition and Pharmacological Effects of Cassia Fistula. Sci. Inquiry Rev.. 2020;4:59-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced sunlight photocatalytic activity and biosafety of marine-driven synthesized cerium oxide nanoparticles. Sci. Rep.. 2021;11:14734.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activities of chromium oxide nanoparticles against klebsiella pneumoniae. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res.. 2017;10:206-209.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultrafine chromium oxide (Cr2O3) nanoparticles as a pseudocapacitive electrode material for supercapacitors. J. Alloy. Compd.. 2021;851:156046

- [Google Scholar]

- Laser-Assisted synthesis of Mn0.50Zn0.50Fe2O4 nanomaterial: characterization and in vitro inhibition activity towards bacillus subtilis biofilm. J. Nanomater.. 2015;16:111.

- [Google Scholar]

- Honey-mediated synthesis of Cr2O3 nanoparticles and their potent anti-bacterial, anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Arab. J. Chem.. 2023;16:104544

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Degradation of Nickel Doped Copper Oxide Nanoparticles. Lahore Garrison Univ. J. Life Sci.. 2020;4:130-138.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis, anti-cancer and corrosion inhibition activity of Cr2O3 nanoparticles. Biointerf. Res. Appl. Chem.. 2021;11:8402-8412.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanoparticle-catalyzed green chemistry synthesis of polybenzoxazole. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2021;143:2115-2122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Raman spectroscopy and x-ray diffraction of phase transitions in Cr2O3 to 61 GPa. Phys. Rev. B. 2004;69:144107

- [Google Scholar]

- ‘Green’synthesis of metals and their oxide nanoparticles: applications for environmental remediation. J. Nanobiotechnol.. 2018;16:1-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Single-phase α-Cr2O3 nanoparticles’ green synthesis using Callistemon viminalis’ red flower extract. Green Chem. Lett. Rev.. 2016;9:85-90.

- [Google Scholar]

- Titus, D., Samuel, E.J.J., Roopan, S.M., 2019. Nanoparticle characterization techniques. Green synthesis, characterization and applications of nanoparticles, Elsevier: 303–319.

- Structural and optical properties of green synthesized Cr2O3 nanoparticles. Mater. Today. Proc.. 2021;36:587-590.

- [Google Scholar]

- Binary ethanol–water solvents affect phenolic profile and antioxidant capacity of flaxseed extracts. Eur. Food Res. Technol.. 2016;242:777-786.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of ethanolic flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) extracts on lipid oxidation and changes in nutritive value of frozen-stored meat products. Acta Sci. Pol. Technol. Aliment.. 2014;13:135-144.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cyclic voltammetric study of Chromium (VI) and Chromium (III) on the gold nanoparticles-modified glassy carbon electrode. Procedia Chem.. 2015;17:170-176.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical assembly of Ni–xCr–yAl nanocomposites with excellent high-temperature oxidation resistance. J. Electrochem. Soc.. 2009;156:C167.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro screening of five local medicinal plants for antibacterial activity using disc diffusion method. Trop. Biomed.. 2005;22:165-170.

- [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of ethanol–water extraction of lignans from flaxseed. Sep. Purif. Technol.. 2007;57:17-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Green synthesis of metallic nanoparticles and their potential applications to treat cancer. Frontiers. Chemistry. 2020;8

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymerization of aniline derivatives by K2Cr2O7 and production of Cr2O3 nanoparticles. Polym. Adv. Technol.. 2017;28:842-848.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nature of nanoparticles and their applications in targeted drug delivery. Pak. J. Sci.. 2020;72:30.

- [Google Scholar]