Translate this page into:

Influence of metal-support interaction on nitrate hydrogenation over Rh and Rh-Cu nanoparticles dispersed on Al2O3 and TiO2 supports

⁎Corresponding author. Fax: +40 213121147. ibalint@icf.ro (Ioan Balint)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Well-defined Rh and Rh-Cu nanoparticles (NP's) of 1.6 nm and 1.3 nm, respectively, were synthesized by alkaline polyol method and then dispersed on insulating (Al2O3) and semiconducting (TiO2) supports. Both colloidal NP's and supported NP's were characterized using various experimental methods (TEM, XPS, XRD, etc.) to gather information about their specific morphology, structure and chemical state. The effects of size and support on the catalytic behavior of NP's for nitrate hydrogenation reaction were analyzed. Oxide supports, especially TiO2, were found to have a strong positive effect on the catalytic activity of metallic NP's. The non-supported, colloidal, Rh and Rh-Cu NP's are either inactive or posses very low hydrogenation activity. For supported materials, the intimate contact between two metals (i.e. Rh-Cu) is required to attain good hydrogenation activity. The strong metal-support interaction, induced by hydrogen spillover, is a key point in determining hydrogenation activity. The Rh-Cu NP's dispersed on TiO2 are extremely active for NO3− and NO2− (intermediate) deep hydrogenation, with high selectivity for NH4+. The hydrogenation activity of Rh-Cu NP's supported on Al2O3 is hindered considerably, the main products of NO3− hydrogenation being NO2− intermediate.

Keywords

Rh and Rh-Cu nanoparticles

Strong metal-support interaction

Hydrogen spillover

Nitrate hydrogenation

1 Introduction

A great challenge in catalytic field is to prepare catalysts, showing enhanced activity and selectivity, based on well-defined metallic and bimetallic nanoparticles (NP's). An important component of the research development is to acquire better understanding on the catalytic systems exhibiting strong-metal support interactions (SMSI).

Metal-support interaction was investigated mostly in the case of monometallic NP's (Sadeghi and Henrich, 1984a,b; Linsmeier and Taglauer, 2011). For example, it is disclosed that the interaction of Pt clusters with basic support favors the catalysis due to the increase in electron density on metal sites (Gates, 1995). However, in spite of intense researches, lack of agreement still exists on the role played by substrate on the activity of NP's. In addition, metal-support interaction is less studied for bimetallic nanoparticles. Study dedicated to this issue would be important because bimetallic NP's show in many cases superior catalytic activity and selectivity compared to monometallic ones due to the synergistic effect between the component metals (Monyoncho et al., 2015). The colloidal deposition method of well defined NP's is a valuable alternative to obtain model catalysts in which is easier to discriminate between support and particle size effects. The influence of the support on the formation of mono and bimetallic nanoparticles is therefore eliminated as the metal nanoparticles are generated before they are dispersed on the support.

Structure sensitive model reactions are the best selection to evidence the distinct influence of size and support on metal(s) catalytic performances. The nitrate catalytic reduction (involving the formation of N—N bonds) is a suitable model reaction because is sensitive to the structure (size and shape) of supported metal particles (Gates, 1995). In addition, nitrate reduction is a good example for the beneficial effect of secondary metal addition on catalytic reduction of nitrate ion (Vorlop and Tacke, 1989).

The reduction of nitrate at ppm level in drinking water has a practical relevance only if the selectivity to nitrogen is close to 100%. Up to date, no efficient catalysts for selective conversion of nitrate and its derivatives for N2 were identified but researches on this field are still in progress (Barrabés and Sá, 2011). The selective and complete conversion of nitrate to ammonia may have impact eventually on energy conservation field. Ammonia was found recently to be a very attractive alternative to H2 as energy storage media (Chakraborty et al., 2010). For ammonia large scale production, with no additional carbon foot print generation, liquid wastes with high concentration of nitrates and nitrites should be used.

Well-defined Rh and Rh-Cu NP's were considered in this research as the best candidates to investigate catalytic reduction of NO3− with H2. One of the reasons is that Rh-based nanoparticles were reported to exhibit good hydrogenation activity. Photocatalytically generated Rh nanoparticles, capped by CTAB, exhibit excellent catalytic activity towards the reduction of aromatic nitro compounds by NaBH4 to their corresponding amino derivates (Kundu et al., 2009). Nitrobenzaldehyde is selectively hydrogenated to aminobenzaldehyde over colloidal Rh-Cu NP's (Sharif et al., 2014). Another reason for our material selection is that, to the best of our knowledge, the hydrogenation of nitrate and/or nitrites over well-defined Rh-based mono/bimetallic nanoparticles, either in colloidal form or dispersed on oxide supports, was not explored yet.

The hydrogenation of nitrate over physical mixtures with Rh and Cu supported on active carbon was reported by Soares et al. (2011). The activity of co-impregnated Rh-Cu/C catalysts was also investigated (Soares et al., 2008, 2009, 2011). Witońska et al. (2007) studied the kinetic of nitrate hydrogenation in water using impregnated Rh/Al2O3 and Rh–Cu/Al2O3 catalysts.

Thus, the investigation of these well-defined Rh-based mono/bimetallic nano-materials would bring new knowledge in catalytic field from fundamental and practical points of view. The aims of our work were to investigate the (i) activity of Rh and Rh-Cu NP's for NO3− hydrogenation, (ii) effect of TiO2 and Al2O3 supports on catalytic behavior of mono and bimetallic nanoparticles, (iii) impact of nanoparticles morphology and chemical state on catalytic activity.

2 Material and methods

2.1 Synthesis of nanoparticles and preparation of supported catalysts

Mono- (Rh) and bimetallic (Rh-Cu) NP's protected by PVP (polyvinylpyrrolidone) were prepared by the alkaline polyol method. The preparation protocol is described in detail in a previous publication (Papa et al., 2011). The metal precursors were RhCl3 (Fluka) and Cu(CH3COO)2 (Merck). The molar ratio between Rh and Cu was one to one. Four supported catalysts were obtained by dispersing the colloidal nanoparticles, previously suspended by sonication in ethanol, on Al2O3 and TiO2-P25 (Aerosil, Japan). The catalytic materials were dried at 100 °C for 4 h and then calcined at 400 °C for 1 h to combust the protective PVP polymer. It is reported that the noble metal-catalyzed PVP removal in the presence of oxygen takes place in temperature range 200–400 °C (Rioux et al., 2006). The final metal loading of support oxides was 3 wt%. Prior to the catalytic runs, the materials were reduced in H2 at 400 °C for 1 h. The catalytic samples are labeled as follows: Rh, Rh-Cu, Rh/Al2O3, Rh/TiO2, Rh-Cu/Al2O3, Rh-Cu/TiO2.

2.2 Characterization

The TEM (Transmission Electron Microscopy) and HRTEM (High Resolution Transmission Electron Microscopy) characterization of catalysts was performed with FEI Tecnai G2-F30 S-Twin microscope operated at 300 kV. Small amounts of the colloidal and supported Rh and Rh-Cu nanoparticles were drop-cast on holey carbon-coated copper grids and subsequently air-dried before TEM analysis. The surface elemental composition and chemical state of catalytic materials was determined by XPS (X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy). The radiation source of VG ESCA 3 Mk II was Al Kα (hν = 1486.7 eV). The 100 mm radius hemispherical electron analyzer was operated at pass energy of 50 eV. The experimental spectra were fitted with Voight functions (SDP 2.3). The crystalline structure of powder catalysts was investigated with a D8 Advance (Bruker-AXS) apparatus using CuKα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å). The diffraction patterns were recorded in the 2Θ = 30–90° domain. The exposed surface area of Rh deposited on Al2O3 and TiO2 was estimated by H2 chemisorption at 25 °C using a ChemBet-3000 Quantachrome Instrument equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). Prior H2 chemisorption measurements, the catalysts were reduced with H2 at 400 °C for 1 h. The TPR (Thermoprogrammed reduction) experiments were carried out with the aforementioned instrument (ChemBet-3000).

2.3 Catalytic tests

The catalytic tests were performed in a batch reactor, thermostated at 25 °C (LabTech H50-500), containing 0.1 g of the powder catalysts dispersed in 200 mL of a nitrate aqueous solution (1.61 mmol L−1/100 mg L−1 NO3−). The H2 was bubbled (10 cm3 min−1) into reactor stirred at 800 rpm with a magnetic bar. Every 30 min aliquots of the solution were withdrawn and filtered. The species of interest (NO3−, NO2− and NH4+) were analyzed with an ion chromatography system (ICS 900 Dionex). The nitrogen, which is a gaseous product, was calculated from the mass balance of reaction.

3 Results and discussion

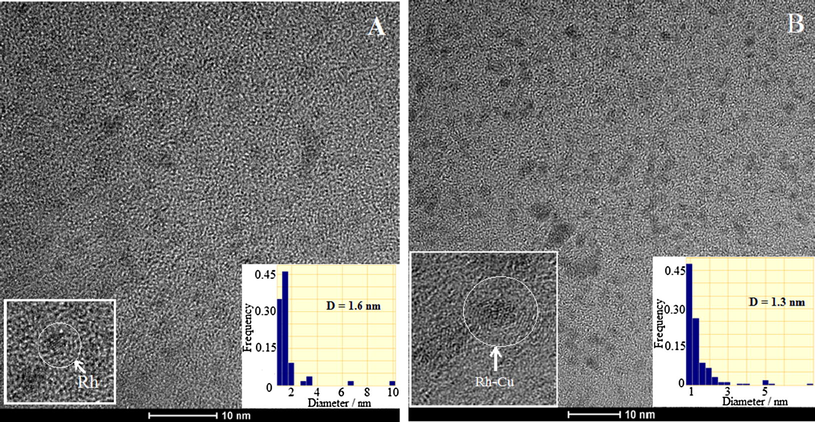

Fig. 1A shows the TEM images of PVP protected Rh nanoparticles. The average size of very fine Rh nanoparticles is centered at 1.6 nm (see the inset containing the associated histogram). At a closer look, few atomic rows can be distinguished at individual nanoparticles.

TEM image of PVP-protected Rh (A) and Rh-Cu (B) nanoparticles and the associated size histograms. The insets evidence magnified individual Rh and Rh-Cu nanoparticle.

The characteristic TEM image of bimetallic Rh-Cu nanoparticles is presented in Fig. 1B. The average size, derived from the inset histogram, is ≈1.3 nm. From TEM analysis it is unambiguous that the polyol synthesis method is able to yield reproductively, fine and well-dispersed Rh as well as Rh-Cu nanoparticles which can be used further to catalyze various chemical reactions.

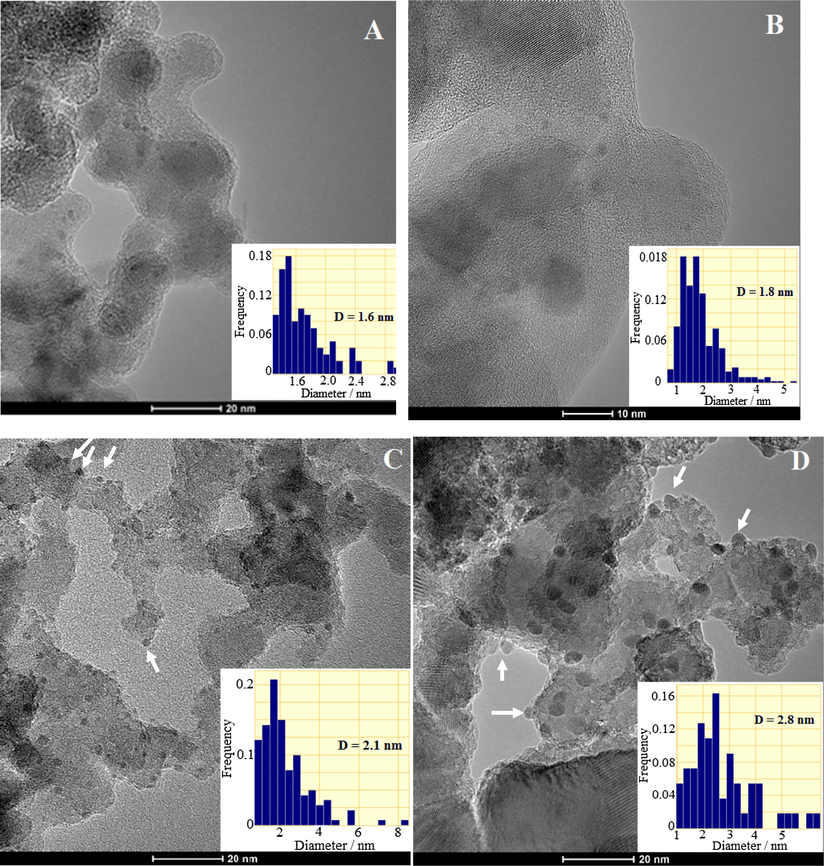

The TEM images of Rh and Rh-Cu NP's dispersed on Al2O3 and TiO2 supports are presented in Fig. 2A–C. The supported mono and bimetallic nanoparticles capped by PVP were calcined and then reduced at 400 °C for 1 h.

TEM images of supported Rh and Rh-Cu nanoparticles: Rh/Al2O3 (A), Rh/TiO2 (B), Rh-Cu/Al2O3 (C) and Rh-Cu/TiO2 (D).

The TEM micrographs of conditioned catalysts reveal the influence, especially in the case of Rh-Cu NP's, of supporting material nature on dispersion (average size). The average size of Al2O3 and TiO2-supported NP's increased to some extent after conditioning procedures (calcination and reduction steps). The only exception was Rh on Al2O3 which preserved its initial size of 1.6 nm. The Rh on TiO2 appeared slightly larger (1.8 nm) than of the precursor nanoparticles (1.6 nm). The Rh-Cu NP's deposited on Al2O3 and on TiO2 underwent to coarsening process, the average diameter increasing from 1.3 nm (the size of colloidal batch NP's) to 2.1 and 2.8 nm, respectively (see the histograms in Fig. 2C and D). The arrows in TEM micrograph 2C points to Rh-Cu NP's characterized by deformed spherical (ovoid) or by hemispherical shapes as result of particle interaction with Al2O3 support. The side view of hemispherical Rh-Cu nanoparticles, indicated by arrows, in intimate (epitaxial) contact with TiO2 support can be visualized in Fig. 2D. The flattening of Rh-Cu NP's on TiO2 suggests that strong interaction takes place between metal and support (SMSI). Earlier published works on other metals confirm this hypothesis. For example, Comotti et al. (2006) advanced the idea that the change in shape of Au particles from spherical to hemispherical one, due to the interaction with the TiO2 support, is an important factor to decide catalytic activity. Similarly, the wetting-like phenomenon of support by Rh-Cu NP’s is likely to create reactive perimeters with catalytic activity (Fujitani et al., 2009).

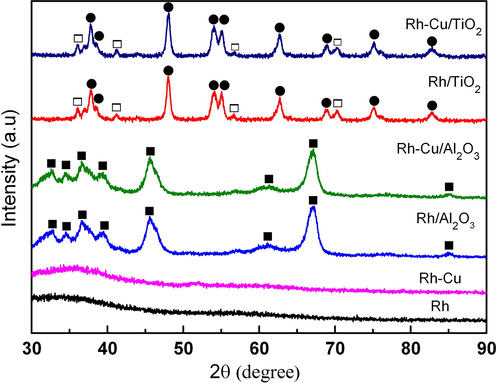

Fig. 3 displays the XRD patterns of colloidal nanoparticles as well as of the supported catalysts. The colloidal Rh and Rh-Cu nanoparticles are XRD amorphous, in spite that few crystalline fringes are visible at some of the individual nanoparticles (see the insets in Figs. 1 and 2). The absence of the characteristic XRD reflections can be explained by the very small size of Rh and Rh-Cu nanoparticles (d = 1.3–1.6 nm). Molecular dynamic simulation demonstrates the formation of amorphous structure is inevitable for metallic NP's on reducing the diameter down to ≈1 nm (Sun et al., 2007). As expected, the supported catalysts show only the characteristic diffraction lines of oxides (alumina and titania’s anatase and rutil).

Comparative XRD patterns of colloidal nanoparticles as well as of the catalysts. ■-γ-Al2O3; ●-anatase; □-rutile.

Relevant surface information on the chemical state of metals and support oxides was obtained from XPS investigation. The atomic sensitivity factors were derived from the electronic cross-section of each element using the transmission and inelastic mean free path corrections.

The XPS analysis was carried out on the as prepared PVP-capped nanoparticles as well as on the conditioned supported catalysts. The XPS results, summarized in Table 1, reflect the complex composition and chemical state of mono and bimetallic nanoparticles. Rhodium is present in mixed metallic and oxide states in all investigated catalysts systems. The Rh/Rh3+ atomic ratio for Rh and Rh-Cu NP's capped with PVP is 1.5 and 1.1, respectively. The oxidized form of rhodium in Rh-Cu nanoparticles dispersed on TiO2 prevailed over the metallic state (Rh/Rh3+ = 0.7) in contrast to the same bimetallic nanoparticles supported on Al2O3 (Rh/Rh3+ = 1.5). In the case of simple Rh nanoparticles, the choice of support seems to have an opposite effect on their oxidation state compared to Rh-Cu system. The TiO2 support favors the metallic state for Rh (Rh/Rh3+ = 3) compared to Al2O3 where Rh/Rh3+ ratio is close to unity.

Materials

BE (eV)

Rh/Rh3+*

Oxidation states

Rh3d5/2

Rh3d3/2

Cu2p3/2

Rh/PVP

307.0

308.7

311.7

313.7

-

-

1.5

Rh0, Rh3+

Rh-Cu/PVP

306.8

308.3

311.5

313.1

933.0

935.6

1.1

Rh0, Rh3+,

Cu0, Cu+

Rh/Al2O3

306.9

308.6

311.7

313.3

–

–

1.0

Rh0, Rh3+

Rh-Cu/Al2O3

307.0

309.0

311.8

313.8

932.6

934.8

1.5

Rh0, Rh3+,

Cu0/Cu+, Cu2+

Rh/TiO2

307.0

309.0

311.8

313.8

–

–

3.0

Rh0, Rh3+,

Ti4+

Rh-Cu/TiO2

307.0

308.5

311.6

313.3

932.6

–

0.7

Rh0, Rh3+

Cu0/Cu+Ti4+, Ti3+

Metal-support interaction can be viewed as a redox reaction (implying electron transfer) at metal(s) - oxide support interface (Fu and Wagner, 2007). Charge will flow from the component with higher Fermi level to the lower one (Tang and Henkelman, 2009). The interactions are strongly dependent on the surface properties of oxide substrate. Surface stoichiometry, surface terminations, and surface defects are the most important factors influencing the metal-oxide interactions (Fu and Wagner, 2007). Chemical reactions, occurring between reactive metals (i.e. Nb) and TiO2, lead to oxidation of few layers of metal in parallel with partial reduction of TiO2 layer of nanometer order near the metal-support junction (Marien et al., 2000). Oxygen mass transport commonly accompanies the chemical reactions at metal-oxide junctions. For Rh-Cu NP's deposited on TiO2 it can be assumed that electron transfer from metal to support favors the increase of Rh3+ (Rh/Rh3+ = 0.7) compared to Al2O3 support (Rh/Rh3+ = 1.5) where electron conduction cannot take place because of alumina insulating characteristics. This corresponds to electronic configuration EF(metal) > EF(TiO2) and results in built-up of negative space charges in TiO2 and downward bending of bands (Fu and Wagner, 2007). Probably that copper intermediates the electronic processes at metal-support interfaces but its precise role remains obscure at present.

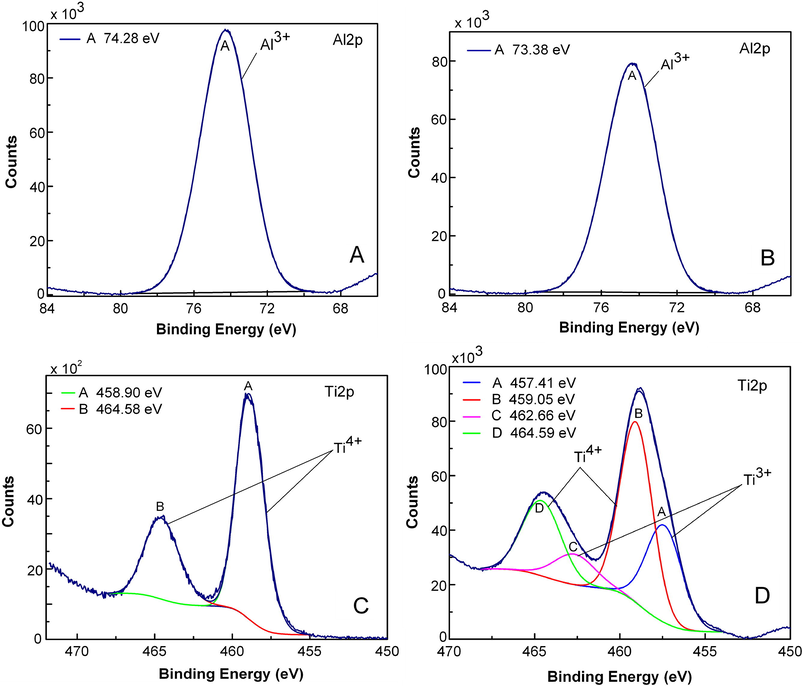

As anticipated, aluminum was in fully oxidized state (Al3+) in alumina support (see Fig. 4A and B). For Rh/TiO2 (Fig. 4C) as well as for simple TiO2 (not shown here), Ti4+ was the only species identified. On the other hand, large amount of Ti3+ was detected at Rh-Cu/TiO2 catalyst. From the XPS spectrum presented in Fig. 4D, the estimated surface fraction of Ti3+ is quite important, about 42.5 at.%. To explain the extensive formation of Ti3+ on the surface of the catalyst, hydrogen spillover from metal NP's to support, during the reduction at 400 °C, should be considered. This mechanism, valid only for reducible and semiconducting oxides (Prins, 2012), implies that H2 molecules dissociate to H atoms on Rh-Cu nanoparticles. According to our TPR results, H2 starts to be activated over Rh-Cu nanoparticles dispersed on TiO2 at room temperature. The resulted H atoms generate electrons (e−) and protons (H+) at the interface with TiO2. The electrons located at Ti4+ sites produce Ti3+ (which are in fact negative lattice defects, Ti'Ti) at the metal-support interface while the protons binds to O2− in the vicinity of Ti3+ forming OH− (OO•, positive lattice defects). The formation of Ti3+ lattice point defects, creating locally electron-rich environments at metal-support perimeter, may promote catalytic activity of deposited metal nanoparticles (Cai et al., 2013). The extent of the reduction of metal oxide at interface with metal particles depends on the activation energy required for proton-electron migration. In the case of Pt/TiO2, the proton-electron migration is limited to the immediate environment of the metal particles due to the relative high migration activation energy (Huizinga and Prins, 1981). Extensive reduction of oxide was observed for materials characterized by low migration activation energy. For example on MoO3, with activation energy of 6–12 kJ mol−1 for electrons and protons, the reduction moves away from the metal support interface and the support is extensively reduced (Prins, 2012). At higher temperatures, two adjacent OH− groups are reversibly eliminated to form one oxygen vacancy (VO••) bearing two positive charges and one H2O molecule. The negative charges of two Ti3+ lattice defects are compensated by positive charges oxygen vacancy. The formation of Ti3+ by hydrogen spillover mechanism was reported also for Pd-Cu/TiO2 catalysts (Kim et al., 2013). In fact, the formation of Ti3+ is indicative that Rh-Cu nanoparticles posses high hydrogenation activity when are supported on suitable oxide material enabling H2 spillover. In the case of Rh/TiO2 catalyst, although H2 can be activated by Rh NP's at low temperature (see TPR results), the electron and proton transfer to TiO2 is not important because the formation of Ti3+ was not evidenced by XPS analysis.

XPS core-level spectra of Al2p, Ti2p regions measured for Rh/Al2O3 (spectrum A), Rh-Cu/Al2O3 (spectrum B), Rh/TiO2 (spectrum C) and for Rh-Cu/TiO2.

TPR measurements were carried out on freshly calcined catalysts to obtain information on the oxidation state of supported metals. The TPR results (hydrogen consumption) are synthetically presented in Table 2. In addition, information concerning the oxidation state of metals on catalysts reduced in H2 at 400 °C for 1 h is displayed for comparison in the same table. The Rh/Rh3+ proportion, depending on the nature of support, shows similar tendency for calcined and reduced catalysts. The Rh/Rh3+ ratio increases for all investigated catalysts after reduction with H2.

Catalyst

H2 consumption (mmol g−1)

Atomic ratio Rh0/Rh3+

TPRa

XPSb

Rh/Al2O3

0.48

0.6

1

Rh/TiO2

0.26

1.3

3

Rh-Cu/Al2O3

0.24

0.77

1.5

Rh-Cu/TiO2

0.33

0.12

0.7

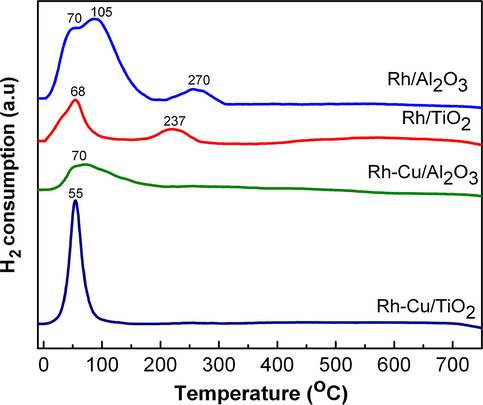

The interesting feature of Rh-Cu-based catalysts is that they exhibit only one reduction peak, located at 55 °C for Rh-Cu/TiO2 and at 70 °C for Rh-Cu/Al2O3. The atypical, simultaneous reduction of CuOx and RhOx species strongly suggests that a synergetic effect takes place between the component metals. Mendes and Schmal (1997) reported that rhodium interaction with copper promotes reduction of copper oxide. Normally, CuOx is reduced at higher temperature compared to Rh2O3 (Guerrero-Ruiz et al., 1997). The second observation is that in spite of high hydrogen consumption (0.33 mmol g−1), the oxidized Rh-Cu NP's on TiO2 are reduced fast in one step process at low temperature (55 °C, see Fig. 5). The two metals behave in fact like one, homogeneous oxide compound. The H2 consumption for Rh-Cu on Al2O3 is smaller (0.24 mmol g−1), and the broad reduction maximum is placed at higher temperature (70 °C). The sharp reduction peak at low temperature of Rh-Cu/TiO2, consistent with high hydrogen consumption rate, suggests excellent catalytic activity for hydrogenation reactions. In contrast to Rh-Cu, supported Rh NP's exhibit distinct low and high temperatures reduction peaks. The reduction maxima of Rh/TiO2 and Rh/Al2O3 are positioned at 68, 237 °C and at 70, 105, 270 °C, respectively. According to the published data, the low-temperature TPR peak belongs to well-dispersed Rh2O3, which is also easily formed, while the high-temperature TPR peak belongs to the reduction of bulk like, crystalline Rh2O3 (or larger Rh2O3 particles) (Vis et al., 1985).

Comparative TPR traces obtained for Rh/Al2O3, Rh/TiO2, Rh-Cu/Al2O3 and Rh-Cu/TiO2.

The number of exposed rhodium atoms was assessed by H2 chemisorption. The assumption was that all the hydrogen adsorption occurred selectively only at Rh sites (Anderson et al., 1999). The particle size of Rh supported on Al2O3 of 1.7 nm (see Table 3), derived from H2 chemisorption measurements, matches well with the average diameter observed by TEM (dTEM = 1.6 nm). For Rh NP's deposited on TiO2, the particle size calculated from H2 chemisorption data is bigger (dH2 = 2.7 nm) than observed by TEM (dTEM = 1.8 nm). The decrease in Rh surface area from 2.9 m2 g−1 (corresponding to Rh particles of about 1.8 nm) to 1.8 m2 g−1, probed by H2 chemisorption, can be interpreted as beginning of metal encapsulation by support oxide. Previous experiments showed that encapsulation of Rh occurs on defected TiO2, subjected to high reduction temperature or Ar+ sputtering (Sadeghi and Henrich, 1984a; Berkó et al., 1998). The encapsulation process requires the outward diffusion of Tiin+ to TiO2 surfaces and an electronic configuration of EF(TiO2) > EF (Rh). The n-type TiO2 and noble metals with large work function (i. e. Pt, Pd, Rh) are necessary for encapsulation reactions (Fu and Wagner, 2007). In our case the encapsulation of Rh nanoparticles by TiO2, leading to decrease in surface of exposed metal surface area, was limited by the relatively low reduction temperature (400 °C). The encapsulation of Rh by TiO2 was reported to charge negatively Rh and to oxidize Ti3+ defects to Ti4+ (Berkó et al., 1998). This observation is in line with our XPS results showing that the formation of Ti3+ lattice defects do not take place for Rh/TiO2.

Catalyst

Dispersion (%)

Metal surface area (m2·g−1)

Particle size (nm)

Rh/Al2O3

22.05

2.91

1.7

Rh/TiO2

13.73

1.81

2.7

Rh-Cu/Al2O3

-

0.18

-

Rh-Cu/TiO2

-

0.15

-

The data in Table 3 show significant lower rhodium surface area for supported Rh-Cu NP's compared to Rh NP's. The CuOx species formed on the surface of Rh nanoparticle core can be a pertinent explanation for these chemisorption results. The XPS and TPR data support also the idea that copper is extensively oxidized to CuO. The TEM and HRTEM images revealed that particle coarsening occurs in the case of alumina and TiO2-supported Rh-Cu nanoparticles (dTEM of Rh-Cu on Al2O3 and TiO2 is 2.1 and 2.8 nm, respectively). The particle coarsening, suggested by H2 chemisorption, contributes to a decrease in Rh surface area. The encapsulation of Rh-Cu nanoparticles by TiO2 cannot be probed by chemisorption measurements as it competes with the covering of Rh nanoparticle with CuOx. The correlation between surface energy (γ) and work function (ϕ) was made and the results suggest that encapsulation is expected for ϕ > 5.3 eV and γ > 2 j m−2 (Fu et al., 2005). Metals with large γ values such as Pt, Pd, Rh, Ir are likely to experience encapsulation reactions while Cu, Ag, Au with small γ value are not expected to be encapsulated. In light of this information it is likely that copper presence prevents the encapsulation of Rh-Cu nanoparticles by TiO2. Thus, the surface of bimetallic nanoparticles remains available for catalytic reactions. This hypothesis is confirmed by the excellent catalytic activity of Rh-Cu nanoparticles deposited on TiO2. The SMSI may contribute to the low value of exposed Rh surface area of Rh-Cu/TiO2 catalyst. The SMSI phenomenon led to a decreased H2 (or CO) chemisorbed on the metal either due to a decrease in the number of surface metal (partially covered by the reduced support oxide) or due to a change in electron density in metal surface (electron flow from metal to support), which cause a decrease in the metal and adsorbate bond strength (Santos et al., 1983; Chou and Vannice, 1987). Sa et al. (2007) observed that SMSI takes place for Pd/TiO2 at relatively low temperatures (350 °C) with the formation of Ti4O7 stable phase, even at exposure to atmospheric pressure. The formation of TiOx species are a consequence of support interaction with H2 dissociated on the noble metals. This finding is consistent with our XPS results showing the formation of large amount of stable Ti3+ after reduction treatment of Rh-Cu/TiO2.

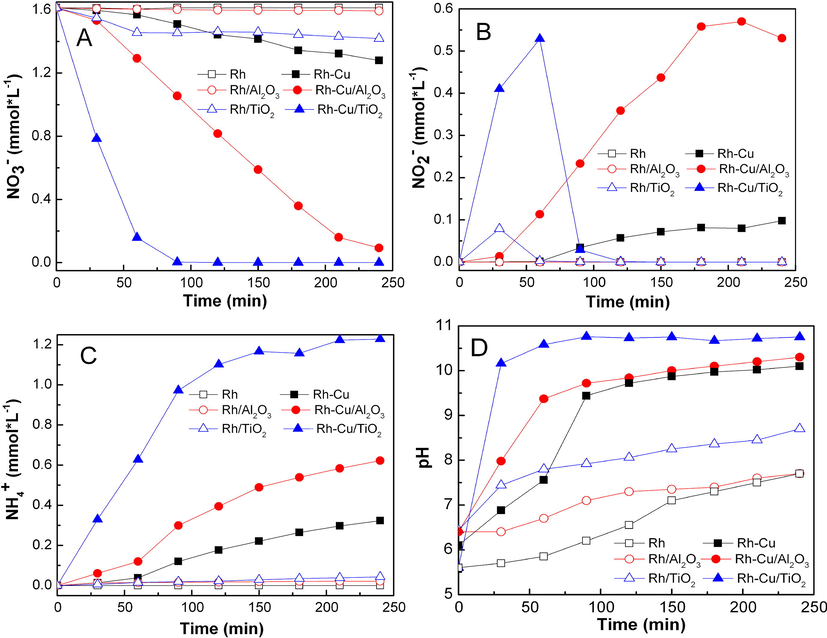

The time courses of NO3− reactant and of products (NO2− and NH4+) are comparatively presented in Fig. 6. The evolution of pH with time is presented in the same figure. The activity of Rh NP's in colloidal form and as supported NP's is represented by open symbols whereas that of Rh-Cu, either in colloidal or supported forms, by closed symbols. The first glance at results depicted in Fig. 6 evince that Rh-Cu NP's, either supported or in colloidal form, perform better than the monometallic Rh NP's in terms of NO3− and NO2− conversions. The second general observation is that the support, regardless its nature, enhances the catalytic performances of mono/bimetallic nanoparticles. The third remark is that deposition of NP's on TiO2 is far a better choice than on Al2O3. The Rh-Cu/TiO2 catalyst showed the best performances in term of NO3− and NO2− conversion and selectivity for NH4+. The NO3− and NO2− (reaction intermediate) were transformed completely in 90 and 120 min, respectively. Assuming the general accepted step way reaction mechanism

(Miyazaki et al., 2015) the calculated reaction rate constants for the hydrogenation of NO3− and NO2− were k1 = 3.5 × 10−2 min−1 and k2 = 4.3 × 10−2 min−1, respectively. The NH4+ was the only ionic compound at the end of denitration reaction over Rh-Cu/TiO2 catalyst. The selectivity for NH4+ and N was 76% and 24%, respectively. The formation of Ti3+ in connection to activity enhancement of Rh-Cu nanoparticles dispersed on TiO2 are in our view the result of SMSI effect. The Ti3+ lattice defects should play an essential role in mechanism of hydrogenation reaction. Probably H2 molecules dissociate at the reactive bimetal-support region formed by SMSI. Similar mechanism for hydrogen dissociation over Au nanoparticles on TiO2 was reported by Fujitani et al. (2009). Then hydrogen atoms react with NO3− (as well as with NO2−) at the perimeter of bimetallic nanoparticles. The protons generation by spillover mechanism, close to the reacting sites (metal-support interface), helps the adsorption of negatively charged anion reactants (NO3− and NO2−) even at basic pHs (see Fig. 6D) when it is supposed that the support should be charged negatively. Usually, the increase of pH in the liquid phase during the reaction course by formation of OH− results in development of negative charge which inhibits the adsorption of nitrate and nitrite ions on the surface of catalyst. One possible cause for ammonia formation are the rise of the pH during reaction and/or as suggested in the literature isolated metal atoms, which can act as active sites (Yoshinaga et al., 2002). Catalytic studies pointed out that the formation of Ti3+ lattice defects is effective to promote in some cases oxidation processes. According to Li et al. (2014), the highly defective structure of Co3O4/TiO3 due to the formation of Ti3+, is responsible for the high catalytic activity observed for CO oxidation.

Comparative time course of NO3− (A), NO2− (B) and NH4+ (C) concentrations for Rh/Al2O3, Rh-Cu/Al2O3, Rh/TiO2 and Rh-Cu/TiO2 catalysts. The figure presents also the time course evolution of pH (D) during the reaction (NO3− + 4 H2 = NH4+ + H2O + 2 OH−).

The Rh-Cu nanoparticles supported on Al2O3 exhibited satisfactory performance for reduction of NO3− (conversion was ≈94%) but on the other hand, the hydrogenation rate of NO2− intermediate was very low (see Fig. 6). The concentration of NO2− reached a maximum at 0.57 mmol L−1, then decreases to 0.53 mmol L−1. The reaction selectivity for NO2−, NH4+ and N at end of reaction time was 28.2, 32.9 and 38.9%, respectively. It is documented that the H2 spillover does not occur for insulators, such as alumina (Prins, 2012). The absence of H2 spillover may explain the limited catalytic activity of the Rh-Cu nanoparticles (originating from solely one batch) when they are supported onto the insulating Al2O3. The simple Rh nanoparticles, performed better on TiO2 than on Al2O3 (see Fig. 6). The Rh/Al2O3 catalyst was practically inactive to hydrogenate NO3−.

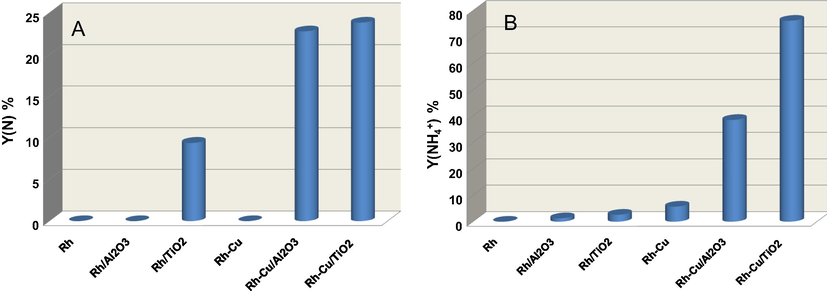

Fig. 7A shows that Rh-Cu NP's on TiO2 show the highest yields to nitrogen as well as to NH4+(Fig. 7B). The non-supported Rh-Cu NP's produce only NH4+. It is clear that by supporting Rh-Cu NP's, both on Al2O3 and TiO2, active sites for selective hydrogenation of NO3− to N2 are created. Zhang et al. (2008) advanced the idea that the selectivity of nitrate hydrogenation depends generally on the size of active phase. On the bimetallic ensembles with size below to 3.5 nm the exposed palladium particle becomes too small to adsorb and activate two N-containing species simultaneously for the formation of nitrogen. Since the formation of ammonium required only one N, the size effect is not remarkable, and ammonium as by-product is always formed. This observation is in line with our results showing that over the very small, non-supported, Rh-Cu NP's of 1.6 nm, NH4+ is formed selectively. The Rh-Cu NP's coarsens when deposited on Al2O3 or on TiO2 to 2.1 and 2.8 nm, respectively. In this case, small amounts of N2 are formed along with the main reaction product, NH4+. In light of this hypothesis, the increase in size can be one of the reasons for N2 formation.

Comparative NO3− hydrogenation yield to N2 (N) and NH4+ over supported and non-supported Rh and Rh-Cu nanoparticles.

4 Conclusions

The catalytic behavior of colloidal and of supported Rh and Rh-Cu nanoparticles in a model hydrogenation reaction (NO3− hydrogenation) was investigated.

The most important findings of this research can be summarized as follow.

-

Oxide supports bust up the catalytic activity of metallic NP's. The non-supported NP's are either inactive or posses only low hydrogenation activity.

-

Two metals are required to obtain good hydrogenation activity. The Rh NP's dispersed on Al2O3 are inactive whereas on TiO2 they show only modest performances. The synergetic effect between Rh and Cu enhances considerably the catalytic activity.

-

The strong metal-support interaction is a key point in determining hydrogenation activity. The Rh-Cu NP's dispersed on TiO2 semiconductor are extremely active for NO3− and NO2− (intermediate) deep hydrogenation, with high selectivity for NH4+. When the same Rh-Cu NP's are supported on Al2O3 insulator the hydrogenation activity is hindered considerably, the main products of NO3− hydrogenation being NO2− intermediate.

Future research plans are aiming to identify a new class of hydrogenation reactions with high practical importance to valorize the excellent hydrogenation activity of Rh-Cu nanoparticles. New catalytic semiconducting supports will be also screened to maximize the catalytic performances of Rh-based NP's through SMSI mechanism. The exploration of synthesis strategies leading to bimetallic nanoparticles with controlled structure (core-shell, inverse core shell, alloy) as well as the accurate control of nanoparticle size is worth of attention in time to come.

Acknowledgements

Financial support through Grant PNII-PTPCCA BICLEANBIOS 46/2012 is greatly appreciated.

References

- IR study of CO adsorption on Cu–Rh/SiO2 catalysts, coked by reaction with methane. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem.. 1999;139:285-303.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic nitrate removal from water, past, present and future perspectives. Appl. Catal. B. 2011;104:1-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Encapsulation of Rh nanoparticles supported on TiO2 (110)-(1× 1) surface: XPS and STM studies. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3379-3386.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transition metal atoms pathways on rutile TiO2 (110) surface: distribution of Ti3+ states and evidence of enhanced peripheral charge accumulation. J. Chem. Phys.. 2013;138:154711.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, D., Petersen, H.N., Johannessen, T., 2010. Nova Science Publishers: Technical University of Denmark, 317–336.

- Calorimetric heat of adsorption measurements on palladium: II. Influence of crystallite size and support on CO adsorption. J. Catal.. 1987;104:17-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Support effect in high activity gold catalysts for CO oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2006;128:917-924.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Interaction of nanostructured metal overlayers with oxide surfaces. Surf. Sci. Rep.. 2007;62:431-498.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal− oxide interfacial reactions: encapsulation of Pd on TiO2 (110) J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:944-951.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hydrogen dissociation by gold clusters. Angew. Chem.. 2009;121:9679-9682.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Supported metal clusters: synthesis, structure, and catalysis. Chem. Rev.. 1995;95:511-522.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation, characterization, and activity forn-hexane reactions of alumina-supported rhodium-copper catalysts. J. Catal.. 1997;171:374-382.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior of titanium(3+) centers in the low- and high-temperature reduction of platinum/titanium dioxide, studied by ESR. J. Phys. Chem.. 1981;85:2156-2158.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic reduction of nitrate in water over Pd–Cu/TiO2 catalyst: effect of the strong metal-support interaction (SMSI) on the catalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B. 2013;142–143:354-361.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Photochemical generation of catalytically active shape selective rhodium nanocubes. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2009;113:18570-18577.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of TiO2 crystal structure on the catalytic performance of Co3O4/TiO2 catalyst for low-temperature CO oxidation. Catal. Sci. Technol.. 2014;4:1268-1275.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Strong metal–support interactions on rhodium model catalysts. Appl. Catal. A. 2011;391:175-186.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nb on (110) TiO2 (rutile): growth, structure, and chemical composition of the interface. Surf. Sci.. 2000;446:219-228.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The cyclohexanol dehydrogenation on Rh CuAl2O3 catalysts. Part 1. Characterization of the catalyst. Appl. Catal. A. 1997;151:393-408.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of particle size and metal–support interaction on denitration behavior of well-defined Pt–Cu nanoparticles. Catal. Sci. Technol.. 2015;5:492-503.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synergetic effect of palladium–ruthenium nanostructures for ethanol electrooxidation in alkaline media. J. Power Sources. 2015;287:139-149.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Morphology and chemical state of PVP-protected Pt, Pt–Cu, and Pt–Ag nanoparticles prepared by alkaline polyol method. J. Nanopart. Res.. 2011;13:5057-5064.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Monodisperse platinum nanoparticles of well-defined shape: synthesis, characterization, catalytic properties and future prospects. Top. Catal.. 2006;39:167-174.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Imaging of low temperature induced SMSI on Pd/TiO2 catalysts. Catal. Lett.. 2007;114:91-95.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rh on TiO2: model catalyst studies of the strong metal-support interaction. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 1984;19:330-340.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- SMSI in Rh/TiO2 model catalysts: evidence for oxide migration. J. Catal.. 1984;87:279-282.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal-support interactions between iron and titania for catalysts prepared by thermal decomposition of iron pentacarbonyl and by impregnation. J. Catal.. 1983;81:147-167.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Selective hydrogenation of 4-nitrobenzaldehyde to 4-aminobenzaldehyde by colloidal RhCu bimetallic nanoparticles. Top. Catal.. 2014;57:1049-1053.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nitrate reduction with hydrogen in the presence of physical mixtures with mono and bimetallic catalysts and ions in solution. Appl. Catal. B. 2011;102:424-432.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Activated carbon supported metal catalysts for nitrate and nitrite reduction in water. Catal. Lett.. 2008;126:253-260.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bimetallic catalysts supported on activated carbon for the nitrate reduction in water: optimization of catalysts composition. Appl. Catal. B. 2009;91:441-448.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Collapse in crystalline structure and decline in catalytic activity of Pt nanoparticles on reducing particle size to 1 nm. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2007;129:15465-15467.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Charge redistribution in core-shell nanoparticles to promote oxygen reduction. J. Chem. Phys.. 2009;130:194504.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The morphology of rhodium supported on TiO2 and Al2O3 as studied by temperature-programmed reduction-oxidation and transmission electron microscopy. J. Catal.. 1985;95:333-345.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Erste Schritte auf dem Weg zur edelmetallkatalysierten Nitrat- und Nitrit-Entfernung aus Trinkwasser. Chem. Ing. Tech.. 1989;61:836-837.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kinetic studies on the hydrogenation of nitrate in water using Rh/Al2O3 and Rh-Cu/Al2O3 catalysts. Kinet. Catal.. 2007;48:823-828.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hydrogenation of nitrate in water to nitrogen over Pd–Cu supported on active carbon. J. Catal.. 2002;207:37-45.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Size-dependent hydrogenation selectivity of nitrate on Pd− Cu/TiO2 catalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008;112:7665-7671.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]