Translate this page into:

Microwave-assisted synthesis and antibacterial propensity of N′-s-benzylidene-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide and N′-((s-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)methylene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide motifs

⁎Corresponding author. ola.ajani@covenantuniversity.edu.ng (Olayinka O. Ajani)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Microwave-assisted approach was utilized as green approach to access a series of 2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide hydrazone derivatives 10a-j of aromatic and heteroaromatic aldehydes in highly encouraging yields. It involved four steps reaction which was initiated with ring opening reaction of isatin in a basified environment and subsequent cross-coupling with pentan-2-one to produce compound 7. Esterification of 7 in acid medium led to the formation of compound 8 which was reacted with hydrazine hydrate to access 9 which upon microwave-assisted condensed with aromatic and heteroaromatic aldehydes furnished the targeted compounds 10a-j. The structures of 10a-j were confirmed by physico-chemical, elemental analyses and spectroscopic characterization which include UV, FT-IR, 1H and 13C NMR as well as DEPT-135. The targeted compounds 10a-j, alongside with gentamicin clinical standard, were investigated for their antibacterial efficacies using agar diffusion method. 2-Propyl-N′-(pyridine-3-ylmethylene) quinoline-4-carbohydrazide 10j emerged as the best antibacterial hydrazide-hydrazone with lowest MIC value of 0.39 ± 0.02 – 1.56 ± 0.02 µg/mL across all the organisms screened.

Keywords

Pfitzinger synthesis

Microwave irradiation

Quinoline

Spectral study

Antibacterial

1 Introduction

The quinoline nucleus is one of the most prevalent heterocyclic scaffolds and is found in several bio-active natural products (Keri and Patil, 2014; Simoes et al., 2014). Quinoline is a benzo-fused pyridine heterocycle which occurs naturally in Skimmianine which is a furoquinoline alkaloid present mainly in the Rutaceae family (Huang et al., 2017). The 2-phenylquinoline was identified as alkaloid from the plant Galipea longiflora (Breviglieri et al., 2017). Quinolines and its derivatives represent a broad class of compounds, which have received considerable attention due to their wide range of pharmacological properties (Khalifa et al., 2017). Owing to high significant of quinoline in medicinal research and other applications, numerous derivatives of this N-heterocycle have been synthesized. For the synthesis of quinolines, various methods have been reported including the Pfitzinger (Ibrahim and Al-Faiyz, 2016), Povarov (Almansour et al., 2015), Doebner-Miller (Ishak et al., 2013), Skraup (Pandeya and Tyagi, 2011), Conrad-Limpach (Brouet et al., 2009), Friedlander (Yang et al., 2007), Combes (Parikh et al., 2006). However, the Friedländer condensation is still considered as a popular method for the synthesis of quinoline derivatives (Nasseri et al., 2015) because among all the named reaction for quinoline synthesis, the Friedländer annulation (Ibrahim and Al-Faiyz, 2016) appears to be still one of the most simple and straightforward approaches for the synthesis of quinolines (Marco-Contelles et al., 2009). However, the adopted approach in this present study was Pfitzinger method wherein ring-opening reaction of isatin followed by condensation with aliphatic ketone was engaged (Sonawane and Tripathi, 2013). There are several other established protocols for the synthesis of these ring frameworks (Liao et al., 2017). Synthesis via linking of other molecular entities with quinoline core have been proven to increase bioactivity of the resultant motifs. For instance, synthesis of aliphatic amide bridged 4-aminoquinoline clubbed 1,2,4-triazole derivatives and evaluation of their antibacterial activity against seven different bacterial strains was reported (Thakur et al., 2016). Gold-catalyzed [4+2]annulation/cyclization of benzisoxazoles was reported as a viable pathway for accessing highly oxygenated quinoline (Sahani and Liu, 2017).

Furthermore, quinoline moiety is an essential pharmacophore and a crucial functionality because of its wide variety of reported biological and pharmacological activities which include anticancer (Zablotskaya et al., 2017), antibacterial (Sun et al., 2017), anti-inflammatory (Pinz et al., 2017), antioxidant (Murugavel et al., 2017), antitubercular (Bodke et al., 2017), antiproliferative (Nathubhai et al., 2017), antifungal (Ben et al., 2017), antimalarial (Vijayaraghavan and Mahajan, 2017), antiprotozoal (Garcia et al., 2017), antitumor (Fouda, 2017), DNA binding (Krstulović et al., 2017), antihypertensive (Kumar et al., 2015), anti-HIV (Zhong et al., 2015), activities among others. Quinoline based tyrosine kinase inhibitors have proven antidiabetic effect in different animal models and in clinical cancer patients (Orfi et al., 2017). Therapeutic efficacy of quinoline derivatives cannot be overemphasized as they form the core structure of numerous commercially available drugs. Some of the examples are ofloxacin 1, quinidine 2, chloroquine 3, clioquinol 4, bosutinib hydrate 5 and ivacaftor 6 (Yin et al., 2015) as shown in Fig. 1. Molecular hybrid is one of the most popular strategies to develop new drug candidates based on combination of structural features of two different active fragments, which do not only reduce the risk of drug-drug interactions but also improve the pharmacological activities (Shaveta et al., 2016). In another study, piperazine bridged 4-aminoquinoline 1,3,5-triazine derivatives led to the production of antibacterial agents (Verma et al., 2016).

Some commercially available quinoline-based drugs and their uses.

Antibiotic-resistant bacteria that are difficult or impossible to treat are becoming increasingly common and are causing a global health crisis. For instances, there were reported cases of methicillin-resistance Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strains (Blair et al., 2015) which are considered to be one of the major causes of food-borne diseases in hospitals (Dehkordi et al., 2017), quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli (QREC) which is common in feces from young calves (Duse et al., 2016), multi-drug resistant Proteus vulgaris (Mandal et al., 2015). In addition, because the importance of fluoroquinolones (FQs) in humans and animals is increasing, FQ-resistant bacteria are a major concern in the treatment of infectious diseases (Hu et al., 2017). The bacteria used in this present study are S. aureus, Bacillus lichenformis, Proteus vulgaris, Micrococcus varian, Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These organisms are great source of potential threat to health and wellbeing of man and his eco-system because they are causative agents of numerous infectious diseases. Due to drug resistance challenges, emergent of new diseases and high rate of global health threat, there is continuous need for the preparation of biologically active heterocyclic compounds as therapeutic target in drug design. Molecular hybridization approach can address these issues. Hence, we have herein incorporated benzylidene and heteroaromatic methylidene on quinoline moiety through hydrazide linker by microwave assisted technique as green approach in order to evaluate their antimicrobial efficacy via in vitro screening for future antimicrobial drug design.

2 Experimental

2.1 Material and methods

All the chemical reagents used herein were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Chemicals except hydrazine hydrate and vanillin which were obtained from Surechem Product Chemicals and Kiran Light Laboratory respectively. They were of analytical grade and were used as received. Stuart melting point apparatus was used to determine the melting points which were uncorrected. The UV–visible analysis was carried out with the aid of UV-Genesys Spectrophotometer Infrared (IR) spectra were run in KBr pellet using the Perkin Elmer FT-IR Spectrophotometer. The progress of the reaction and the level of purity of the compounds were routinely checked by Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) on silica gel plates. The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on NMR Bruker DPX 400 Spectrometer operating at the machine frequencies of 400 MHz and 100 MHz respectively using DMSO-d6 as solvent. DEPT-135 NMR analysis was evaluated for all the synthesized compounds and Tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as internal standard. The microwave assisted synthesis were carried out using CEM Discover Monomode oven operating at frequency of 2450 MHz monitored by a PC computer and temperature control was fixed at 140 °C within the power modulation of 500 W. The reactions were performed in sealed tube within ramp time of 1 to 3 min. The elemental analysis (C, H, N) of the synthesized compounds were performed using a Flash EA 1112 elemental analyzer. Selectivity index (S.I.) was calculated by dividing the zones of inhibition of compounds against organisms with the zones of inhibition of gentamicin against organisms.

2.2 Synthetic procedures

2.2.1 General procedure for microwave-assisted synthesis of targeted products (10a-j)

2-Propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 9 (3.0 g, 13 mmol) was dissolved in ethanol (10 mL) in a sealed tube. The corresponding aldehyde (13 mmol) was added and the resulting mixture was then irradiated in microwave oven for a period of 1 to 3 min as the case may be based on the result obtained from the monitored progress of reaction using TLC spotting in dichloromethane (DCM) as eluent. The heated solution was allowed to cool to ambient temperature and filtered to afford the corresponding hydrazide-hydrazone of quinoline (10a-j) in good to excellent yields.

2.2.1.1 N'-Benzylidene-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (10a)

Microwave-assisted reaction of 9 (3.0 g, 13 mmol) with benzaldehyde (1.3 mL, 13 mmol) for 1 min afforded N’-benzylidene-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 10a. Yield 3.84 g, 93%. UV–Vis.: λmax (nm)/log εmax (M−1 cm−1): 212 (3.97), 225 (3.99), 236 (4.01), 257 (4.64), 314 (4.21). IR (KBr, cm−1) : 3358 (N—H), 3151 (C—H aromatic), 2943 (C—H aliphatic), 2805 (C—H aliphatic), 1683 (C⚌O hydrazide), 1604 (C⚌C aromatic), 1589 (C⚌N), 1467 (CH3 deformation), 1335 (CH2 deformation), 1248 (C—N of hydrazide), 929 (⚌C—H bending), 749 (Ar-H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 8.36 (s, 1H), 7.83–7.81 (d, J = 8.40 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.75–7.73 (d, J = 8.28 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.43–7.40 (m, 3H, Ar-H), 7.29–7.26 (dd, J1 = 8.40 Hz, J2 = 10.00 Hz 2H, Ar-H), 5.80 (s, 1H, N⚌C—H), 3.31–3.25 (q, J = 7.22 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.97–1.91 (m, 2H, Aliph-H), 0.88–084 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 173.3 (C⚌O), 155.2, 151.0, 146.6, 142.7, 138.1, 134.0 (2 × CH), 132.0, 127.8, 120.8, 117.7, 117.1, 115.2 (2 × CH), 112.6, 110.5, 29.7, 25.2, 15.1 (CH3) ppm. DEPT 135 (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: Positive signals are: 155.2, 138.1, 134.0 (2 × CH), 132.0, 127.8, 117.1, 115.2 (2 × CH), 112.6, 110.5, 15.1 (CH3). Negative signals are: 29.7 (CH2), 25.2 (CH2) ppm.

2.2.1.2 N′-(4-Chlorobenzylidene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (10b)

Microwave-assisted reaction of 9 (3.0 g, 13 mmol) with 4-chlorobenzaldehyde (1.83 g, 13 mmol) for 1 min afforded N′-(4-chlorobenzylidene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 10b. Yield 4.53 g, 92%. UV–Vis.: λmax (nm)/log εmax (M−1 cm−1): 221 (4.33), 228 (4.25), 250 (4.43), 260 (4.80), 308 (4.78). IR (KBr, cm−1) : 3376 (N—H), 3060 (C—H aromatic), 2943 (C—H aliphatic), 2884 (C—H aliphatic), 1689 (C⚌O hydrazide), 1616 (C⚌C aromatic), 1593 (C⚌N), 1463 (CH3 deformation), 1334 (CH2 deformation), 1202 (C—N of hydrazide), 934 (⚌C—H bending), 826 (C—Cl), 745 (Ar-H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 8.36 (s, 1H), 7.83–7.81 (d, J = 8.80 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.75–7.73 (d, J = 8.20 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.29–7.26 (dd, J1 = 8.20 Hz, J2 = 10.02 Hz 2H, Ar-H), 7.12–7.10 (d, J = 8.80 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 5.80 (s, 1H, N⚌C—H), 3.31–3.25 (q, J = 7.22 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.96–1.91 (m, 2H, Aliph-H), 1.02–0.99 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 173.2 (C⚌O), 156.4, 155.2, 142.8 (2 × CH), 138.1, 134.1 (2 × CH), 132.0, 127.5, 117.5, 115.2 (2 × CH), 112.6, 110.5, 29.5, 25.4, 15.3 (CH3) ppm. DEPT 135 (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: Positive signals are: 155.2, 142.8 (2 × CH), 134.1 (2 × CH), 132.0, 127.5, 117.5, 115.2 (2 × CH), 110.5, 15.3 (CH3). Negative signals are: 29.5 (CH2), 25.4 (CH2) ppm.

2.2.1.3 N’-(4-Ethoxybenzylidene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (10c)

Microwave-assisted reaction of 9 (3.0 g, 13 mmol) with 4-ethoxybenzaldehyde (1.95 g, 13 mmol) for 3 min afforded N′-(4-ethoxybenzylidene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 10c. Yield 3.69 g, (73%). UV–Vis.: λmax (nm)/log εmax (M−1 cm−1): 225 (4.48), 227 (4.61), 255 (4.62), 272 (5.07), 338 (4.94). IR (KBr, cm−1) : 1682 (C⚌O hydrazide), 1602 (C⚌C aromatic), 1572 (C⚌N), 1471 (CH3 deformation), 1300 (C—N of hydrazide), 1116 (C—O, of OEt), 921 (⚌C—H bending), 749 (Ar-H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 8.38 (s, 1H), 7.83–7.81 (d, J = 8.60 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.74–7.72 (d, J = 8.22 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.29–7.26 (dd, J1 = 8.22 Hz, J2 = 10.00 Hz 2H, Ar-H), 7.12–7.10 (d, J = 8.60 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 5.80 (s, 1H, N⚌C—H), 3.31–3.25 (q, J = 7.16 Hz, 2H, CH2CH3), 3.17–3.11 (q, J = 7.22 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.98–1.90 (m, 2H, Aliph-H), 1.12–1.08 (t, J = 7.16 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2), 1.02–0.99 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 173.5 (C⚌O), 156.2, 155.1, 151.0, 147.3, 142.5 (2 × CH), 135.9, 134.2 (2 × CH), 132.0, 127.5, 117.1, 115.0 (2 × CH), 112.3, 110.7, 47.8, 29.4, 25.0, 20.1, 14.9 (CH3) ppm. DEPT 135 (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: Positive signals are: 142.5 (2 × CH), 134.2 (2 × CH), 132.0, 127.5, 117.1, 115.0 (2 × CH), 110.7, 20.1 (CH3), 14.9 (CH3). Negative signals are: 47.8 (CH2), 29.4 (CH2), 25.0 (CH2) ppm.

2.2.1.4 N’-(3-Methoxybenzylidene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (10d)

Microwave-assisted reaction of 9 (3.0 g, 13 mmol) with 3-methoxybenzaldehyde (1.77 g, 13 mmol) for 3 min afforded N′-(3-methoxybenzylidene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 10d. Yield 3.16 g, (65%). UV–Vis.: λmax (nm)/log εmax (M−1 cm−1): 215 (4.47), 221 (4.47), 240 (4.58), 257 (4.99), 308 (4.93). IR (KBr, cm−1) : 3459 (N—H), 3106 (C—H aromatic), 2923 (C—H aliphatic), 2854 (C—H aliphatic), 1699 (C⚌O hydrazide), 1622 (C⚌C aromatic), 1580 (C⚌N), 1458 (CH3 deformation), 1346 (CH2 deformation), 1245 (C—N of hydrazide), 1185 (C—O, of OMe), 927 (⚌C—H bending), 719 (Ar-H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 8.38 (s, 1H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.83–7.81 (d, J = 8.00 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.75–7.73 (d, J = 8.20 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.61–7.59 (d, J = 7.80 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.42–7.39 (m, 1H, Ar-H), 7.29–7.26 (dd, J1 = 8.20 Hz, J2 = 10.00 Hz 2H, Ar-H), 7.06 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 5.80 (s, 1H, N⚌C—H), 3.31–3.25 (q, J = 7.22 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.40 (s, 3H, OCH3), 1.98–1.93 (m, 2H, Aliph-H), 1.02–0.99 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 173.9 (C⚌O), 157.4, 154.4, 151.3, 146.6, 141.7, 139.0, 138.1, 134.7 (2 × CH), 132.5, 124.9, 123.3, 120.8, 115.2, 112.3, 110.8, 55.9 (OCH3), 31.9, 24.9, 15.1 (CH3) ppm. DEPT 135 (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: Positive signals are 146.6, 141.7, 138.1, 134.7 (2 × CH), 132.5, 124.9, 120.8, 112.3, 110.8, 55.9 (OCH3), 15.1 (CH3) ppm. Negative signals are: 31.9, 24.9 (CH2) ppm.

2.2.1.5 N’-(2-Nitrobenzylidene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (10e)

Microwave-assisted reaction of 9 (3.0 g, 13 mmol) with 2-nitrobenzaldehyde (1.96 g, 13 mmol) for 2 min afforded N’-(2-nitrobenzylidene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 10e. Yield 3.86 g, (76%). UV–Vis.: λmax (nm)/log εmax (M−1 cm−1): 210 (4.32), 230 (4.41), 237 (4.38), 250 (4.41), 257 (5.11). IR (KBr, cm−1) : 3411 (N—H), 3104 (C—H aromatic), 3035 (C—H aromatic), 2913 (C—H aliphatic), 2865 (C—H aliphatic), 1699 (C⚌O of hydrazide), 1608 (C⚌C aromatic), 1571 (C⚌N), 1527 (N—O of NO2), 1447 (CH3 deformation), 1346 (CH2 deformation), 1271 (C—N), 983 (⚌C—H bending), 743 (Ar-H). 1H NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 8.36 (s, 1H), 8.16–8.14 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.84–7.82 (d, J = 7.54 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.75–7.73 (d, J = 8.20 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.29–7.27 (dd, J1 = 8.20 Hz, J2 = 10.02 Hz 2H, Ar-H), 7.22 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 7.12–7.06 (m, 2H, Ar-H), 5.80 (s, 1H, N⚌C—H), 3.31–3.25 (q, J = 7.22 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.96–1.91 (m, 2H, Aliph-H), 1.02–0.99 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 173.2 (C⚌O), 157.2, 151.2, 146.3, 141.2, 138.5, 138.0, 134.1 (2 × CH), 132.4, 131.6, 126.0, 121.7, 120.3, 117.7, 115.4, 110.3, 31.5, 26.1, 21.0 (CH3) ppm. DEPT 135 (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: Positive signals are 141.2, 138.5, 138.0, 134.1 (2 × CH), 126.0, 120.3, 117.7, 115.4, 110.3, 21.0 (CH3) ppm. Negative signals: 31.5, 26.1 (CH2).

2.2.1.6 N’-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzylidene)-2-propyl quinoline-4-carbohydrazide (10f)

Microwave-assisted reaction of 9 (3.0 g, 13 mmol) with vanillin (1.98 g, 13 mmol) for 2 min afforded N′-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzylidene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 10f. Yield 4.73 g (93%). UV–Vis.: λmax (nm)/log εmax (M−1cm−1): 221 (4.23), 236 (4.29), 248 (4.31), 278 (4.76), 308 (4.80). IR (KBr, cm−1) : 3320 (OH of phenol), 3021 (C—H aromatic), 2977 (C—H aliphatic), 2947 (C—H aliphatic), 2858 (C—H aliphatic), 1681 (C⚌O of hydrazide), 1620 (C⚌C), 1575 (C⚌N), 1464 (CH3 deformation), 1373 (CH2 deformation), 1271 (C—N), 1114 (C—O of OMe), 983 (⚌C—H bending), 733 (Ar-H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 9.02 (s, 1H, OH), 8.37 (s, 1H), 8.13 (s, 1H), 8.01–7.99 (d, J = 7.60 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), 7.76–7.74 (d, J = 8.22 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.61–7.59 (d, J = 7.56 Hz, 1H, Ar-H),7.29–7.26 (dd, J1 = 8.22 Hz, J2 = 10.00 Hz 2H, Ar-H), 7.06 (s, 1H, Ar-H), 5.80 (s, 1H, N⚌C—H), 3.31–3.25 (q, J = 7.22 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.40 (s, 3H, OCH3), 1.98–1.93 (m, 2H, Aliph-H), 1.02–0.99 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 173.0 (C⚌O), 159.5, 157.4, 154.4, 151.3, 146.6, 141.7, 139.0, 138.1, 134.7 (2 × CH), 132.5, 124.9, 123.3, 120.8, 115.2, 110.8, 55.9 (OCH3), 31.9, 24.9, 15.1 (CH3) ppm. DEPT 135 (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: Positive signals are 146.6, 141.7, 138.1, 134.7 (2 × CH), 132.5, 124.9, 120.8, 115.2, 110.8, 55.9 (OCH3), 15.1 (CH3) ppm. Negative signals: 31.9, 24.9 (CH2) ppm.

2.2.1.7 N'-((1H-pyrrol-2-yl)methylene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (10g)

Microwave-assisted reaction of 9 (3.0 g, 13 mmol) with 1H-pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde (1.24 g, 13 mmol) for 2 min afforded N'-((1H-pyrrol-2-yl)methylene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 10g (88%). Yield 3.50 g (88%). UV–Vis.: λmax (nm)/log εmax (mol−1 cm−1): 208 (3.85), 215 (3.90), 224 (3.98), 230 (4.11), 257 (4.46). IR (KBr, cm−1) : 3310 (N—H), 3245 (N—H), 3102 (C—H aromatic), 2964 (C—H aliphatic), 2870 (C—H aliphatic), 1681 (C⚌O of hydrazide), 1621 (C⚌C), 1588 (C⚌N), 1452 (CH3 deformation), 1364 (CH2 deformation), 1275 (C—N), 983 (=C—H bending), 744 (Ar-H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 11.05 (s, 1H, NH), 8.54 (s, 1H), 8.21 (s, 1H), 7.75–7.73 (d, J = 8.20 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.29–7.26 (dd, J1 = 8.20 Hz, J2 = 10.08 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.95–6.93 (d, J = 7.76 Hz, 1H, Pyrr-H), 6.55–6.51 (dd, J1 = 7.76 Hz, J2 = 7.94 Hz, 1H, Pyrr-H), 6.22–6.20 (d, J = 7.94 Hz, 1H, Pyrr-H), 5.80 (s, 1H, N⚌C—H), 3.31–3.25 (q, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.96–1.91 (m, 2H, Aliph-H), 1.02–0.99 (t, J = 7.10 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO‑d6) δC: 173.3 (C⚌O), 157.6, 155.2, 151.2, 146.8, 143.0, 138.3, 134.3 (2 × CH), 131.4, 125.1, 121.1, 117.1, 112.6, 110.5, 29.9, 25.6, 15.1 (CH3) ppm. DEPT 135 (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: Positive signals are: 155.2, 138.3, 134.3 (2 × CH), 131.4, 125.1, 121.1, 117.1, 110.5, 15.1 (CH3) ppm. Negative signals are: 29.9 (CH2), 25.6 (CH2) ppm.

2.2.1.8 N'-((5-Methyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)methylene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (10h)

Microwave-assisted reaction of 9 (3.0 g, 13 mmol) with 5-methyl-1H-pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde (1.42 mL, 13 mmol) for 3 min afforded N'-((5-methyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)methylene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 10h. Yield 3.04 g (73%). UV–Vis.: λmax (nm)/log εmax (mol−1 cm−1): 203 (4.04), 225 (4.08), 251 (4.10), 254 (4.38), 305 (4.11). IR (KBr, cm−1) : 3443 (N—H), 3362 (N—H), 3059, 3035 (C—H aromatic), 2970 (C—H aliphatic), 2876 (C—H aliphatic), 1687 (C⚌O of hydrazide), 1614 (C⚌C), 1575 (C⚌N), 1461 (CH3 deformation), 1375 (CH2 deformation), 1292 (C—N), 945 (⚌C—H bending), 725 (Ar-H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 11.04 (s, 1H, NH), 8.58 (s, 1H), 8.22 (s, 1H), 7.75–7.73 (d, J = 8.20 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.29–7.26 (dd, J1 = 8.20 Hz, J2 = 10.08 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.83–6.81 (d, J = 7.78 Hz, 1H, Pyrr-H), 6.22–6.20 (d, J = 7.78 Hz, 1H, Pyrr-H), 5.80 (s, 1H, N⚌C—H), 3.31–3.25 (q, J = 7.22 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.38 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.96–1.91 (m, 2H, Aliph-H), 1.02–0.99 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 173.1 (C⚌O), 155.1, 151.0, 146.5, 142.8, 138.1, 134.2 (2 × CH), 131.3, 125.1, 121.1, 117.1, 115.0, 112.6, 110.5, 29.9, 25.6, 18.3 (CH3), 15.1 (CH3) ppm. DEPT 135 (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: Positive signals are: 155.2, 138.1, 134.2 (2 × CH), 131.3, 125.1, 117.1, 110.5, 18.3 (CH3), 15.1 (CH3) ppm. Negative signals are: 29.9 (CH2), 25.6 (CH2) ppm.

2.2.1.9 N'-((3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)methylene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide (10i)

Microwave-assisted reaction of 9 (3.0 g, 13 mmol) with 3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde (1.60 mL, 13 mmol) for 3 min afforded N'-((3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-2-yl)methylene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 10i. Yield 3.51 g (81%). UV–Vis.: λmax (nm)/log εmax (mol−1 cm−1): 215 (4.33), 224 (4.43), 240 (4.33), 257 (5.14). IR (KBr, cm−1) : 3374 (N—H), 3303 (N—H), 3036 (C—H aromatic), 2980 (C—H aliphatic), 2889 (C—H aliphatic), 1688 (C⚌O of hydrazide), 1605 (C⚌C), 1587 (C⚌N), 1465 (CH3 deformation), 1355 (CH2 deformation), 1297 (C—N), 983 (⚌C—H bending), 747 (Ar-H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 11.04 (s, 1H, NH), 8.56 (s, 1H), 8.20 (s, 1H), 7.75–7.73 (d, J = 8.20 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.29–7.24 (dd, J1 = 8.20 Hz, J2 = 11.26 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 6.47 (s, 1H, Pyrr-H), 5.80 (s, 1H, N⚌C—H), 3.31–3.25 (q, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H, CH2), 2.46 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.38 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.96–1.91 (m, 2H, Aliph-H), 1.02–0.99 (t, J = 7.12 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 173.3 (C⚌O), 155.0, 151.0, 146.5, 142.8, 138.1, 134.2 (2 × CH), 131.3, 125.1, 121.1, 116.8, 115.0, 112.6, 110.5, 29.9, 25.6, 18.8 (CH3), 18.3 (CH3), 15.1 (CH3) ppm. DEPT 135 (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: Positive signals are: 155.0, 138.1, 134.2 (2 × CH), 131.3, 125.1, 116.8, 110.5, 18.8 (CH3), 18.3 (CH3), 15.1 (CH3) ppm. Negative signals are: 29.9 (CH2), 25.6 (CH2) ppm.

2.2.1.10 2-Propyl-N’-(pyridine-3-ylmethylene)quinoline-4-carbohydrazide (10j)

Microwave-assisted reaction of 9 (3.0 g, 13 mmol) with 3-pyridine carboxaldehyde (1.22 mL, 13 mmol) for 1½ min afforded 2-propyl-N′-(pyridine-3-ylmethylene) quinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 10j 4.28 g (96%). UV–Vis.: λmax (nm)/log εmax (M−1 cm−1): 221 (4.15), 250 (4.15), 254 (4.47), 314 (4.40), 410 (3.58). IR (KBr, cm−1) : 3419 (N—H), 3059 (C—H aromatic), 2959 (C—H aliphatic), 2865 (C—H aliphatic), 1683 (C⚌O of hydrazide), 1615 (C⚌C), 1575 (C⚌N), 1451 (CH3 deformation), 1367 (CH2 deformation), 1269 (C—N), 1271 (C—N), 934 (⚌C—H bending), 724 (Ar-H). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δH: 8.88 (s, 1H), 8.42 (s, 1H), 8.11 (s, 1H), 7.96–7.94 (d, J = 7.04 Hz, 1H, Pyr-H), 7.75–7.73 (d, J = 8.22 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.61–7.59 (d, J = 7.46 Hz, 1H, Pyr-H), 7.29–7.26 (dd, J1 = 8.22 Hz, J2 = 10.08 Hz, 2H, Ar-H), 7.08–7.04 (dd, J1 = 7.04 Hz, J2 = 7.46 Hz, 1H, Pyr-H), 5.80 (s, 1H, N⚌C—H), 3.31–3.25 (q, J = 7.20 Hz, 2H, CH2), 1.96–1.90 (m, 2H, Aliph-H), 1.02–0.99 (t, J = 7.10 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: 173.5 (C⚌O), 157.4, 155.1, 151.0, 147.3, 142.8, 138.0, 134.2 (2 × CH), 130.9, 127.3, 121.0, 117.1, 112.5, 110.2, 108.5, 29.9, 25.6, 15.1 (CH3) ppm. DEPT 135 (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δC: Positive signals are: 155.1, 138.0, 134.2 (2 × CH), 130.9, 127.3, 121.0, 117.1, 110.2, 108.5, 15.1 (CH3) ppm. Negative signals are: 29.9 (CH2), 25.6 (CH2) ppm.

2.3 Antibacterial activity assay

The antibacterial assay of the 10a-j was investigated against six organisms namely: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, Bacillus lichenformis and Micrococcus varians. The organisms were not type culture; but they were locally isolated organisms which were identified using API Kits and conventional biochemical methods. The clinical standard, gentamicin was used as the positive control and DMSO was used as the solvent for dissolution. Antibacterial sensitivity testing was carried out using agar diffusion method while minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) test was determined by serial dilution method as described by standard method (Russell and Furr, 1977). To obtain minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC), 0.1 mL volume was taken from each tube and spread on agar plates. The number of c.f.u was counted after 18–24 h of incubation at 35 °C. It was determined from the broth dilution of MIC tests by sub-culturing to agar plates that do not contain the test agent. The MBC is identified by determining the lowest concentration of antibacterial agent that reduces the viability of the initial bacterial inoculum by a pre-determined reduction such as ≥99.9% (Ajani and Nwinyi, 2010).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Chemistry

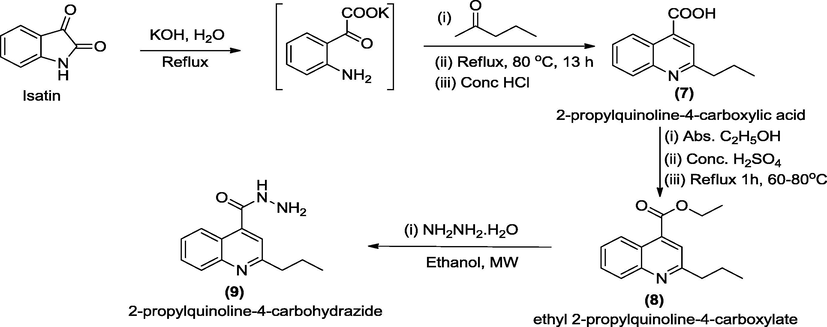

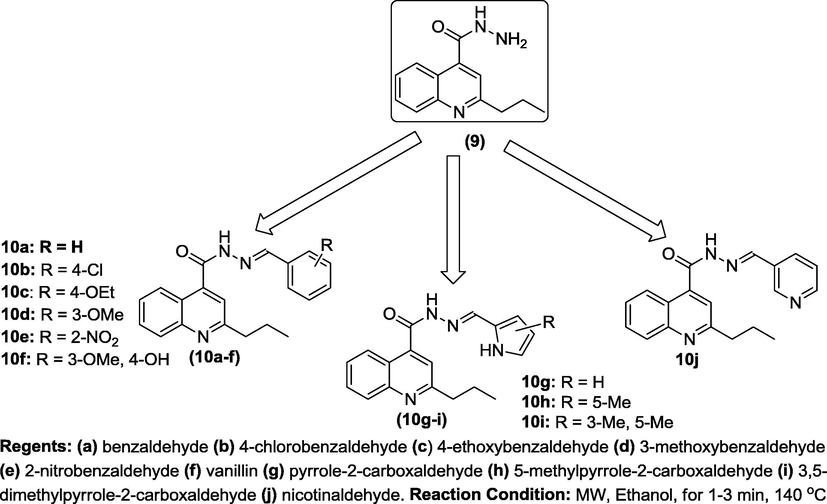

Microwave-assisted reactions have been intensely investigated since the earliest publications (Gedye et al., 1986; Giguerre et al., 1986). Based on the experimental data from various studies that have been reported over three decades ago, chemists have found that, microwave-enhanced chemical reaction rates and can be faster than those of conventional heating methods by as much as a thousand-fold (Hayes, 2004). The emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria causes an urgent need for new generation of antibiotics, which may have a different mechanism of inhibition or killing action from the existing ones (Sun et al., 2017). Thus, in continuation of our research effort on the microwave assisted synthesis of heterocyclic scaffolds (Ajani et al., 2016; Ajani et al., 2010; Ajani and Nwinyi, 2010), we have herein reported the preparation of N′-(s-benzylidene and s-heteroaromatic methylidene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazides, 10a-j in order to investigate their antimicrobial efficacies for possible future drug development. The synthetic pathway adopted to synthesize the reactive intermediate 7–9 and targeted products 10a-j were as described in Schemes 1 and 2 respectively. The synthesis started with ring-opening reaction of isatin and subsequent cross-coupling with pentan-2-one by heating under reflux for 13 h according to a standard method (Saleh and Khaleel, 2015), to afford 2-propylquinoline-4-carboxylic acid 7 which was esterified to produce ethyl 2-propylquinoline-4-carboxylate 8 which upon hydrazinolysis furnished 2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide 9 in improved yield (Scheme 1). Microwave assisted reaction of compound 9 with benzaldehyde an and its derivatives b-f afforded 10a-f while its reaction with 5-membered heterocycle 1H-pyrrole, g and its substituted derivatives h-i produced 10g-i (Scheme 2). Finally, microwave assisted reaction of 9 with 6-membered heterocycle nicotinaldehyde j furnished 10j (Scheme 2). It is interesting to note that the targeted compounds 10a-j were obtained in good to excellent yields within short reaction times of 1–3 min. in an eco-friendly manner under the influence of microwave irradiation as green approach. According to Table 1, the result of the physicochemical parameters unveiled that the 10i was produced in highest yield (96%) while 10d was obtained in lowest yield (65%). The melting points of compounds 10g, 10h and 10i were 271–273 °C, 288–290 °C and 300 °C respectively while all other final products, (10a-f and 10j) refused to melt at 300 °C, except that of 10d which was not determined because it was oily substance. The visual observation confirmed that colour ranged from brown (10b, 10g) to black (10c, 10d) to yellow (10a, 10e, 10f, 10h) to orange (10i-j). The elemental analysis result was consistent with the molecular masses of the compounds and it existed within limit of ±0.25 between% calculated and% found for C, H, N of the final products 10a-j. N.D. = Not Determined (oil). Comp. No = Compound Number. (s) = sharp melting point. Mol. Wt. = Molecular weight. Melting Pt = Melting Point.

Pathways for the synthesis of 2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 9.

N′-(Substitutedbenzylidene)-2-propylquinoline-4-carbohydrazide, 10a-j.

Comp No

Molecular formula

Mol. Wt.

Yield (%)

Melting pt (oC)

Colour

Elemental analysis (%)Calcd. (Found)

C

H

N

10a

C20H19N3O

317.38

93

>300

Yellow

75.69(75.81)

6.03(5.89)

13.24(13.33)

10b

C20H18ClN3O

351.83

92

>300

Brown

68.38(68.19)

5.16(4.95)

11.94(12.08)

10c

C22H23N3O2

361.44

73

>300

Black

73.11(72.97)

6.41(6.29)

11.63(11.82)

10d

C21H21N3O2

347.41

65

N.D.

Black

72.60(72.78)

6.09(5.88)

12.10(11.91)

10e

C20H18N4O3

362.38

76

>300

Yellow

66.29(66.13)

5.01(4.79)

15.46(15.71)

10f

C21H21N3O3

363.41

93

>300

Yellow

69.41(69.62)

5.82(6.01)

11.56(11.78)

10g

C18H18N4O

306.36

88

271–273

Brown

70.57(70.71)

5.92(6.07)

18.29(18.37)

10h

C19H20N4O

320.39

73

288–290

Yellow

71.23(7.09)

6.29(6.11)

17.49(17.26)

10i

C20H22N4O

334.41

81

300 (s)

Orange

71.83(71.74)

6.63(6.45)

16.75(16.89)

10j

C19H18N4O

318.37

96

>300

Orange

71.68(71.85)

5.70(5.55)

17.60(17.81)

In addition, UV, IR, 1H and 13C NMR as well as DEPT-135 were used as the spectroscopic means of characterizing the targeted compounds 10a-j. The UV spectra of 10a-j were run in solution using ethanol solvent. The first electronic transition in all the compounds was found at λmax of 203–225 nm. This was as a result of π → π∗ transition which confirmed the presence of conjugated C⚌C of benzene which agreed with the value earlier reported for benzene nucleus (Ajani et al., 2016). The longest wavelength λmax of 410 nm found in 10j and other bathochromic shifts experienced were ascribed to the chromophoric C⚌N group; characteristic of K bands (Komurcu et al., 1995) and existence of some auxochromes which led to n→π∗ transitions that originated from the lone pair of electron delocalization ability. FT-IR spectra was run for compounds 10a-j in KBr pellet with vibrational absorption bands appearing at : 3459–3245 cm−1, 3151–3021 cm−1, 2980–2805 cm−1, 1699–1681 cm−1, 1622–1602 cm−1, 1593–1571 cm−1, 1471–1451 cm−1, depicting the presence of N—H, C—H aromatic, C—H aliphatic, C⚌O hydrazide, C⚌C aromatic, C⚌N quinoline/hydrazone, CH3 deformation. Specifically, the presence of a broad band at 3320 cm−1 in compound 10f depicted the presence of OH of phenol which was in line with the stretching vibrational frequency of the hydrogen-bonded OH reported by Siyanbola et al. (2017). In addition, the presence of C—N and Ar-H functionalities in all the final products 10a-j was confirmed by the bending vibrational absorption bands at 1300–1202 cm−1 and 749–719 cm−1 respectively which was in concordance with earlier findings where synthesis and characterization of 2-quinoxalinone-3-hydrazone derivatives was reported (Ajani et al., 2010).

In addition, the chemical shifts and the multiplicity patterns of 1H- and 13C NMR spectra run in deuterated DMSO were consistent with that of the proposed structures of the title compounds 10a-j. Taking 10a as the representative compound, its 1H NMR spectrum in a 400 MHz machine showed that 1H of CH of heterocyclic ring resonated downfield at a singlet at δ 8.36 ppm. Also, 2H aromatic doublet signal at δ 7.83–7.81 ppm was due to presence of proton at 5- and 8-positions of quinoline ring, while the remaining 2H on that same benzene ring at 6- and 7-positions appeared as doublets of doublet at 7.29–7.26 ppm with coupling constant values of 8.40 Hz and 10.00 Hz. The benzylidene 5H of resonated as two signals comprising 2H doublet at δ 7.75–7.73 ppm and 3H multiplet δ 7.43–7.40 ppm. The chemical shift values of the aromatic protons agreed with those earlier reported by Ogunniran et al. (2015) wherein, nicotinic acid hydrazide was utilized as ligand for metal complexes synthesis. The upfield signals outside the aromatic region were recorded between δ 5.80 ppm to δ 0.84 ppm with the most shielded peak being that of 3H triplet of CH3-CH2 at δ 0.88–0.84 ppm having a coupling constant of 7.12 Hz. The 13C NMR spectrum of 10a showed the presence of C⚌O of hydrazide at 173.3 ppm while the sixteen aromatic carbon atoms and azomethine carbon atoms resonated from 155.2 ppm to 110.5 ppm which were in line with earlier reported ranges for aromatic carbon atoms (Ajani et al., 2016). The aliphatic propyl carbon atom at 2-position appeared as two CH2 at 29.7 ppm and 25.2 ppm while the only CH3 resonated upfield at δ 15.1 ppm. The DEPT 135 showed that there were twelve positive signals which comprised of eleven CH signals and one CH3 signal, while there were two negative signals which depicted the presence of two CH2 signals. These were in accordance with the findings from the 13C NMR result.

3.2 Antibacterial activity

The in vitro screening of the synthesized compounds 10a-j and gentamicin standard was carried out on six bacterial isolates (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, Proteus vulgaris, Bacillus lichenformis and Micrococcus varian) using agar diffusion method (Russell and Furr, 1977). The choice of gentamicin as clinical standard is owing to the fact that it is a bactericidal antibiotic that works by irreversibly binding the 30S subunit of the bacterial ribosome, interrupting protein synthesis (Ajani et al., 2010; Prescott et al., 2005). The result of sensitivity testing of 10a-j with zones of inhibition in mm is as shown in Table 2. It is interesting to note that Pseudomonas aeruginosa was resistant against gentamicin whereas it was sensitive to compounds 10a-j with largest zone of inhibition being 30 mm from 10c and 10j. Although, P. aeruginosa possesses the hardy cell wall which contains porins and efflux pumps called ABC transporters, which pump out some antibiotics before they are able to act (Prescott et al., 2005), yet synthesized compounds 10a-j herein inhibited the growth of this organism considerably. Comparing the efficiency of gentamicin with synthesized compounds unveiled that three compounds 10e, 10f and 10j inhibited the growth of Staphylococcus aureus at larger Z.O.I. (30–33 mm) than the gentamicin with Z.O.I. of 23 mm. Considering the growth inhibition potential against E. coli, only 10e (Z.O.I. = 29 mm) and 10j (Z.O.I. = 27 mm) exhibited larger inhibition zones than gentamicin (Z.O.I. = 25 mm). Low activity experienced in 10d against E. coli (Z.O.I. = 9 mm) might be due to the protective biofilms formed by this organism. According to the result of the screening against Proteus vulgaris, only 10e (Z.O.I. = 27 mm) possessed larger inhibitory efficiency than gentamicin (Z.O.I. = 25 mm); although, all the compounds showed considerably improved inhibition with Z.O.I. from 15 mm to 27 mm. Comparative study of activity on Bacillus lichenformis showed that its growth inhibition in 10b and gentamicin (Z.O.I. = 15 mm) was similar; lower for 10a, 10c, 10d (Z.O.I. = 11–13 mm) while the rest of the compounds (Z.O.I. = 18–29 mm) exhibited higher inhibitory activity than gentamicin against the growth of Bacillus lichenformis. P. aeruginosa = Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus = Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli = Escherichia coli, B. lichenformis = Bacillus lichenformis, P. vulgaris = Proteus vulgaris, M. varian = Micrococcus varian. GTM. = Gentamicin, R = Resistance. Mean ± Standard deviation of triplicate measurements. Compd No = Compound No.

Compd. No

Organisms used and Z.O.I. (mm)

P. aeruginosa

S. aureus

E. coli

P. vulgaris

B. lichenformis

M. varians

10a

15.00 ± 0.11

16.00 ± 0.13

17.00 ± 0.15

15.00 ± 0.13

13.00 ± 0.11

10.00 ± 0.10

10b

19.00 ± 0.23

19.00 ± 0.17

17.00 ± 0.15

18.00 ± 0.17

15.00 ± 0.14

13.00 ± 0.14

10c

30.00 ± 0.41

23.00 ± 0.25

17.00 ± 0.14

18.00 ± 0.19

13.00 ± 0.12

18.00 ± 0.20

10d

23.00 ± 0.26

17.00 ± 0.15

9.00 ± 0.08

23.00 ± 0.27

11.00 ± 0.12

18.00 ± 0.19

10e

17.00 ± 0.14

30.00 ± 0.39

29.00 ± 0.37

27.00 ± 0.27

25.00 ± 0.22

28.00 ± 0.37

10f

13.00 ± 0.11

33.00 ± 0.42

19.00 ± 0.24

23.00 ± 0.26

18.00 ± 0.19

19.00 ± 0.23

10g

16.00 ± 0.17

17.00 ± 0.15

17.00 ± 0.14

22.00 ± 0.25

25.00 ± 0.21

23.00 ± 0.25

10h

14.00 ± 0.13

15.00 ± 0.14

14.00 ± 0.12

20.00 ± 0.23

22.00 ± 0.20

17.00 ± 0.14

10i

14.00 ± 0.14

16.00 ± 0.16

15.00 ± 0.14

19.00 ± 0.23

21.00 ± 0.21

13.00 ± 0.11

10j

30.00 ± 0.39

34.00 ± 0.41

27.00 ± 0.24

16.00 ± 0.18

29.00 ± 0.38

25.00 ± 0.22

GTM

R

23.00 ± 0.26

25.00 ± 0.21

25.00 ± 0.28

15.00 ± 0.14

18.00 ± 0.20

Furthermore, both community-associated and hospital-acquired infections with Staphylococcus aureus have increased in the past 20 years. In fact, S. aureus has been identified has highly problematic bacterial isolate which has caused high mortality rate in the recent time (Baorto et al., 2017). In view of this, the selectivity index (S.I.) of quinoline hydrazide-hydrazones 10a-j in comparison with gentamicin, was evaluated against the S. aureus (Fig. 2). The comparative study of activity potential of 10a-j versus that of gentamicin against S. aureus was considered since, in humans, gentamicin has structurally different ribosomes from bacteria, thereby allowing the selectivity of this antibiotic for bacteria. Each of the compounds 10b, 10e, 10f, and 10j had a better selectivity index (with S.I. > 1) as compared with gentamicin whereas compounds 10a, 10d, 10g, 10h, and 10i possessed lesser selectivity indices (S.I. < 1) than gentamicin antibiotic, but 10c had similar S.I. with gentamicin in the growth inhibition on S. aureus. These significant antibacterial activities of the synthesized compounds may be explained with clue of the site of action of hydrazones and hydrazides, where it interacts with bases of DNA of the organisms, and thus, inserts (intercalates) between the stacked bases of helix. This insertion possibly causes a stretching of the DNA duplex and the DNA polymerase is fooled into inserting an extra base opposite an intercalated molecule thereby results to frame shifts. The frame shifts invariably will affect the physiological activity by not arraying the right bases that confer resistance on the organisms (Ajani et al., 2010).

Result of the selectivity index of hydrazide-hydrazones (10a-j) against S. aureus.

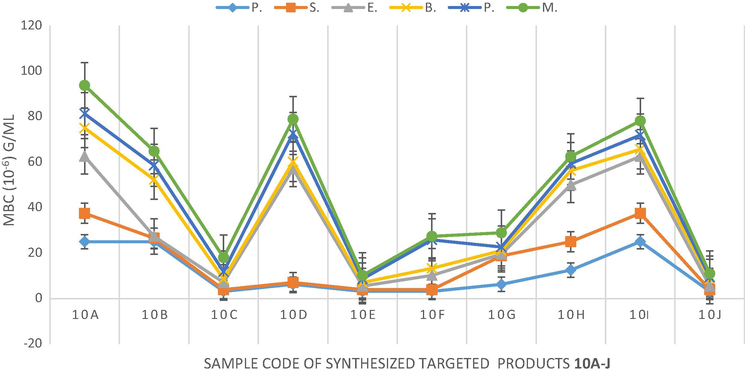

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of the synthesized compounds 10a-j against the six screened organisms was achieved by a standard procedure (Russell and Furr, 1977) and the result is as shown in Table 3. Generally speaking, the MIC values of the compounds 10a-j ranged from 0.39 ± 0.02 µg/mL to 25.00 ± 0.12 µg/mL. However, critical studies among the benzylidenes 10a-f showed that non-substituted benzylidene 10a (R = H) had lowest potency (3.13 ± 0.03 – 25.00 ± 0.11 µg/mL) while the substituted benzylidenes 10b-f exhibited improved activity with 10c (R = 4-OCH2CH3) being the most potent (0.39 ± 0.02 – 1.56 ± 0.02 µg/mL). This implied that presence of ethoxy substituent, an electron donating group, at para position of benzylidene conferred the highest potency as far as benzylidene groups 10a-f were concerned. On the contrary, five membered non-substituted heteroaromatic methylidene-containing compound, 10g (0.39 ± 0.02 – 12.50 ± 0.03 µg/mL) showed a better efficiency than the substituted counterparts 10h-i (1.56 ± 0.02 – 12.50 ± 0.08 µg/mL) while six membered non-substituted heteroaromatic methylidene-containing compound 10j (0.39 ± 0.02 – 1.56 ± 0.02 µg/mL) had highest potency among 10a-j against all the six organisms. From the result of the MIC test, therefore, order of activity of the three most significant compounds against the six organisms was 10j > 10c > 10g. Since, all the compounds are structurally related at the quinoline nucleus, it is obvious that nitrogen heteroatom of pyridine in 10j and of pyrrole in 10g played significant role in the antibacterial diversity of the compounds. On the overall, compound 10j emerged as the most active antibacterial agent because it has the lowest MIC value against all the six organisms. Having obtained highly impressed MIC values in the in vitro antibacterial screening, the Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) testing was conducted using standard method as earlier reported (Ajani and Nwinyi, 2010). MBC is the lowest concentration at which 99.9% of the inoculum was killed. The MBC of all the compounds against all the organisms were twofold higher than their MIC except in the activity of compound 10a against Pseudomonas aeruginosa wherein the MBC was found to be the same fold concentration with the MIC (Fig. 3). P. aeruginosa = Pseudomonas aeruginosa, S. aureus = Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli = Escherichia coli, B. licheniformis = Bacillus lichenformis, P. vulgaris = Proteus vulgaris, M. varian = Micrococcus varian. Mean ± Standard deviation of triplicate measurements.

Sample

Organism used (µg/mL)

P. aeruginosa

S. aureus

E. coli

B. lichenformis

P. vulgaris

M. varians

10a

25.00 ± 0.11

6.25 ± 0.10

12.50 ± 0.05

6.25 ± 0.08

3.13 ± 0.03

6.25 ± 0.09

10b

12.50 ± 0.10

0.78 ± 0.02

0.39 ± 0.02

12.50 ± 0.09

3.13 ± 0.02

3.13 ± 0.03

10c

1.56 ± 0.02

0.39 ± 0.04

1.56 ± 0.02

0.78 ± 0.02

1.56 ± 0.02

3.13 ± 0.02

10d

3.13 ± 0.02

0.39 ± 0.02

25.00 ± 0.12

1.56 ± 0.02

6.25 ± 0.08

3.13 ± 0.02

10e

1.56 ± 0.02

0.39 ± 0.03

0.78 ± 0.03

0.78 ± 0.02

0.78 ± 0.02

0.78 ± 0.03

10f

1.56 ± 0.02

0.39 ± 0.02

3.13 ± 0.03

1.56 ± 0.03

6.25 ± 0.04

0.78 ± 0.02

10g

3.13 ± 0.03

6.25 ± 0.03

0.39 ± 0.02

0.78 ± 0.03

0.78 ± 0.03

3.13 ± 0.02

10h

6.25 ± 0.03

6.25 ± 0.04

12.50 ± 0.04

3.13 ± 0.03

1.56 ± 0.03

1.56 ± 0.02

10i

12.50 ± 0.08

6.25 ± 0.03

12.50 ± 0.08

1.56 ± 0.02

3.13 ± 0.03

3.13 ± 0.03

10j

1.56 ± 0.02

0.39 ± 0.02

0.78 ± 0.02

1.56 ± 0.02

0.39 ± 0.02

0.78 ± 0.02

Graphical representation of minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC).

3.3 Structure activity relationship (SAR) study

The establishment of the SAR model is essential in order to obtain a deeper insight into the molecular description of compounds’ activities. Since all the derivatives as structurally related at their quinoline-hydrazides congeners’ end; hence, the variation in antibacterial activities could be traced to either the nature / position of substituents in phenyl-linked hydrazone for 10a-f and on the numbers of membered-ring nature in the N-heterocyclic-linked hydrazones 10g-j. Therefore, the substitutions on aryl ring of these analogues were varied so as to understand this phenomenon. Comparing the substitution patterns of the phenyl linked hydrazones, 10a-f, on the growth inhibition against P. aeruginosa, the non-substituted phenyl, 10a (R = H) was the least active (MIC = 25 µg/mL; MBC = 25 µg/mL). The most active compounds among this series of 10a-f were compounds 10c (4-OEt), 10e (2-NO2) and 10f (4-OH), against the growth of S. aeruginosa (MIC = 1.56 µg/mL; MBC 3.13 µg/mL). This was a strong indication that the presence of electron donating group (EDG) at position 4 and electron withdrawing group (EWG) at position 2 had crucial effects on the activity increase observed on the growth inhibition experienced on S. aeruginosa as far as phenyl ring substitution was concerned. On the contrary, when electron withdrawing substituent (EWG) was on position 4 (Cl) as seen in 10b, there was activity decrease (MIC = 12.50 µg/mL; MBC 25.00 µg/mL). This showed that a careful selection of EWG and EDG and their point of attachment on phenyl ring is a worthwhile adventure in the activity scale of preference for phenyl-linked hydrazones 10a-f. The SAR study of the pyrrole-linked hydrazones series 10g-i and pyridine-linked hydrazone 10j against S. aeruginosa unveiled the order of antibacterial activity to be 10j > 10g > 10h > 10i. This implied 10j (MIC = 1.56 µg/mL; MBC 3.13 µg/mL) which was a non-substituted six-membered heterocycle here conferred more activity on the quinoline-based templates than any of the five-membered heterocyclic pyrrole derivatives 10g-i. Furthermore, non-substituted pyrrole 10g (MIC = 3.13 µg/mL; MBC 6.25 µg/mL) was twofold more active than monosubstituted one, 10h (MIC = 6.25 µg/mL; MBC 12.50 µg/mL) which was in turn twofold more active than disubstituted pyrrole-linked 10i (MIC = 12.50 µg/mL; MBC 25.00 µg/mL). It means that the presence or increase in numbers of EDGs on pyrrolo or heterocyclic-linked hydrazones led to loss of activity.

4 Conclusions

In conclusion, microwave-assisted synthesis of title compounds 10a-j was successfully achieved in good to excellent yields. Structural elucidation of the compounds was correctly established since the spectral data information conformed vividly to the proposed structures of 10a-j. All compounds exhibited broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity against six bacterial isolates with large zones of inhibition in mm. Compound 10j emerged as the best antimicrobial hydrazide hydrazone with the lowest MIC value of 0.39 ± 0.02 – 1.56 ± 0.02 µg/mL. This compound possesses envisaged candidature for further pharmacological study for future antimicrobial drug development.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledged Covenant University for her support. This work was also supported by The World Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 14-069 RG/CHE/AF/AC_1).

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Microwave assisted synthesis and antimicrobial activity of 2-quinoxalinone-3-hydrazone derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2010;18(1):214-221.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparative study of microwave-assisted and conventional synthesis of 3-[1-(s-phenyl imino) ethyl]-2H-chromen-2-ones and selected hydrazone derivatives. J. Appl. Sci.. 2016;16(3):77-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microwave assisted synthesis and evaluation of antimicrobial activity of 3-{3-(s-aryl and s-heteroaromatic)acryloyl}-2H-chromen-2-one derivatives. J. Heterocycl. Chem.. 2010;47:179-187.

- [Google Scholar]

- Straightfoward synthesis of pyrrolo[3, 4-b]quinolines through intramolecular Povarov reactions. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2015;56:6900-6903.

- [Google Scholar]

- Baorto, E.P., Baorto, D., Windle, M.L., Lutwick, L.I., Steele, R.W. 2017. Staphylococcus aureus infection clinical presentation. Medscape Medical News. <http://emedicine.medscape.com/ article/ 971358-clinical> (accessed 12 August 2017).

- The quinoline bromoquinol exhibits broad-spectrum antifungal activity and induces oxidative stress and apoptosis in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother.. 2017;72(8):2263-2272.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol.. 2015;13:42-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, antibacterial and antitub ercular activity of novel Schiff bases of 2-(1-benzofuran-2-yl)quinoline-4-carboxylic acid derivatives. Russ. J. Gen. Chem.. 2017;87:1843-1849.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gastroprotective and anti-secretory mechanism of 2-phenyl quinoline, an alkaloid isolated from Galipea longiflora. Phytomedicine. 2017;25:61-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- A survey of solvents for the Conrad-Limpach synthesis of 4-hydroxyquinolones. Synth. Commun.. 2009;39(9):5193-5196.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of antibiotic resistance of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from hospital food. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control.. 2017;6:104.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Occurrence and spread of quinolone-resistant Escherichia coli on dairy farms. Appl. Environ., Microbiol.. 2016;82(13):3765-3773.

- [Google Scholar]

- Halogenated 2-amino-4pyrano[3,2-h]quinoline-3-carbonitriles as antitumor agents and structure-activity relationships of the 4-, 6- and 9-positions. Med. Chem. Res.. 2017;26:302-313.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and antiprotozoal activity of furanchalcone-quinoline, furanchalcone-chromone and furanchalcone-imidazole hybrids. Med. Chem. Res. 2017

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The use of microwave ovens for rapid organic synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett.. 1986;27(3):279-282.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of commercial micro-wave oven to organic synthesis. Tetrahedron Lett.. 1986;27(41):4945-4948.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in microwave-assisted synthesis. Aldrichim. Acta. 2004;37(2):66-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and mechanism of fluoroquinolone resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from swine feces in Korea. J. Food Protect.. 2017;80(7):1145-1151.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic profile of Skimmianine in rats determined by ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometry. Molecules. 2017;22:489. 12 pp

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A simple one-pot synthesis of quinoline-4-carboxylic acids by the Pfitzinger reaction of isatin with enaminones in water. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2016;57:110-112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of some new 6-substituted-2, 4-di (hetar-2-yl)quinolines via micheal addition-ring closure reaction of schiff base N-(hetar-2-yl) methylene aniline with hetarylketones. Int. J. Pharm. Phytopharmacol. Res.. 2013;2(6):431-435.

- [Google Scholar]

- Quinoline: A promising antitubercular target. Biomed. Pharmacother.. 2014;68:1161-1175.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities of some novel carboxamides derived from 2-phenyl quinoline candidates. Biomed. Res.. 2017;28(2):869-874.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of some arylhydrazones of p-amino benzoic acid hydrazide as antimicrobial agents and their in-vitro hepatic microsomal metabolism. Boll. Chim. Farmac.. 1995;134:375-379.

- [Google Scholar]

- New quinoline-arylamidine hybrids: Synthesis, DNA/RNA binding and tumor activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2017;137:196-210.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antihypertensive activity of a quinoline appended chalcone derivative and its site-specific binding interaction with a relevant target carrier protein. RSC Adv.. 2015;5:65496-65513.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expeditious synthesis of pyrano[2,3,4-de] quino lines via Rh-catalyzed cascade C-H activation/annulation/lactonization of quinoline-4-ol with alkynes. Chem. Commun.. 2017;53:7824-7827.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isolation and characterization of multi-drug resistance Proteus vulgaris from clinical samples of UTI infected patients from Midnapore, West Bengal. Int. J. Life Sci. Pharm. Res.. 2015;5(2):32-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, structural elucidation, antioxidant, CT-DNA binding and molecular docking studies of novel chloroquinoline derivatives: Promising antioxidant and anti-diabetic agents. J. Photochem. Photobiol.. 2017;173:216-230.

- [Google Scholar]

- Proficient procedure for preparation of quinoline derivatives catalyzed by NbCl5 in glycerol as green solvent. J. Appl. Chem. 2015:7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Highly potent and isoform selective dual site binding Tankyrase/Wnt signaling inhibitors that increase cellular glucose uptake and have antiproliferative activity. J. Med. Chem.. 2017;60(2):814-820.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural and in vitro anti-tubercular activity study of (E)-N’- (2,6-dihydroxybenzylidene)nicotinohydrazide and some transition metal complexes. J. Iran. Chem. Soc.. 2015;12:815-829.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel members of quinoline compound family enhance insulin secretion in RIN-5AH beta cells and in rat pancreatic islet microtissue. Sci. Rep.. 2017;7:44073.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthetic approaches for quinoline and isoquinoline. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci.. 2011;3(3):53-61.

- [Google Scholar]

- Name Reactions in Organic Synthesis. Cambridge: Foundation Books, UK; 2006.

- 7-Chloro-4-phenylsulfonyl quinoline, a new antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory molecule: Structural improvement of a quinoline derivate with pharmacological activity. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol.. 2017;90:72-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- In Microbiology (6th ed.). McGraw Hill; 2005.

- Antibacterial activity of a new chloroxylenol preparation containing ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid. J. Appl. Bacteriol. UK. 1977;43:253-260.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gold-catalyzed [4+2] annulation/cyclization cascades of benzisoxa zoles with propiolate derivatives to access highly oxygenated tetrahydroquinolines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2017;56:12736-12740.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of isatine derivatives considering Pfitzinger reaction part 1. Int. J. Sci. Res.. 2015;4(8):2083-2089.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hybrid molecules: The privileged scaffolds for various pharmaceuticals. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2016;124:500-536.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficient synthesis of 2,4-disubstitued quinolines: Calix[n]arene-catalyzed Povarov-hydrogen-transfer reaction cascades. RSC Adv.. 2014;4:18612-18615.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on the antibacterial and anticorrosive properties of synthesized hybrid polyurethane composites from castor seed oil. Rasayan J. Chem.. 2017;10(3):1003-1014.

- [Google Scholar]

- The chemistry and synthesis of 1H-indole-2,3-dione (isatin) and its derivatives. Int. Lett. Chem. Phys. Astron.. 2013;7(1):30-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial activity of N-methylbenzofuro[3,2-b]quinoline and N-methylbenzoindolo [3,2-b]-quinoline derivatives and study of their mode of action. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2017;135:1-11.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis, SAR, docking and antibacterial evaluation: Aliphatic amide bridged 4-aminoquinoline clubbed 1,2,4-triazole derivatives. Int. J. ChemTech. Res.. 2016;9(3):629-634.

- [Google Scholar]

- Piperazine bridged 4-aminoquinoline 1,3,5-triazine derivatives: Design, synthesis, characterization and antibacterial evaluation. Int. J. ChemTech. Res.. 2016;9:261-269.

- [Google Scholar]

- Docking, synthesis and antimalarial activity of novel 4-anilinoquinoline derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2017;27(8):1693-1697.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of quinoline derivatives via the Friedländer reaction. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:7654-7658.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of furo[3,4c] quinolin-3(1H)-one derivatives through TMG catalyzed intramolecular aza-MBH reaction based on the furanones. RSC Adv.. 2015;5(22):17296-17299.

- [Google Scholar]

- N-Heterocyclic choline analogues based on 1,2,3,4-tetrahydro(iso)quinoline scaffold with anticancer and anti-infective dual action. Pharmacol. Rep.. 2017;69:575-581.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of benzene sulfonamide quinoline derivatives as potent HIV-1 replication inhibitors targeting Rev protein. Org. Biomol. Chem.. 2015;13:1792-1799.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2018.01.015.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1