Translate this page into:

Morinda citrifolia (Noni): A comprehensive review on its industrial uses, pharmacological activities, and clinical trials

⁎Corresponding author. drmeer1@gmail.com (Reem Abou Assi)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Traditional medical practitioners in Hawaii and Polynesia have used Morinda citrifolia L. (Noni) for centuries to cure or prevent varieties of illnesses. The popularity of M. citrifolia as a dietary supplement, a food functional ingredient, or as a natural health enhancer is increasing throughout the world. M. citrifolia contains phytochemicals that own antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, antitumor, anthelminthic, analgesic, hypotensive, anti-inflammatory and immune enhancing effects. Moreover, the increasing vogue of M. citrifolia has attracted industries to employ it as a part of various products and for wide applications such as a natural source of medicines and chemical reagents as well as a green insecticidal. The wide spread of M. citrifolia in tropical climate of the globe, from USA to Brazil reaching to Tahiti, Malaysia and Australia, contributed in enriching its uses and potentials due to the variation in harvest locations. M. citrifolia parts including fruits, seeds, barks, leaves, and flowers are utilized on their own for individual nutritional and therapeutical values, however, the fruit is considered to contain the most valuable chemical compounds. This review discusses in details the industrial uses and the pharmacological activities of M. citrifolia fruit, seed, leaf and root, along with their isolated phytochemical compounds, through describing the conducted in vitro and in vivo studies as well as clinical data.

Keywords

Noni

Morinda citrifolia

Cancer

Pharmacological

Food

Industrial

1 Introduction

Morinda citrifolia is the scientific name of the commercially known plant Noni. The name Morinda citrifolia is also referring to the botanical name which is originally derived from the two Latin words “morus” imputing to mulberry, and “indicus” imputing to Indian, it belongs to the Rubiaceae family (Nelson, 2006). In Hawaii M. citrifolia called Noni, whereas in India it is called Indian mulberry and nuna, or ach. Malaysians call it mengkudu and in Southeast Asia it is called nhaut, while in the Caribbean, it is called the painkiller bush or cheese fruit (Chan-Blanco et al., 2006).

Currently, there are two recognized varieties of M. citrifolia (M. citrifolia var. citrifolia and M. citrifolia var. bracteata) and one cultivar (M. citrifolia cultivar Potteri). The most commonly found variety is M. citrifolia var. citrifolia, with the greatest health and economic importance. Traditional healers can recognize these varieties by the leaf size and shape, in addition to the fruit odor; however, most research has not distinguished between the different M. citrifolia varieties yet (Pawlus and Kinghorn, 2007).

In the early 1990s, the first commercialized products derived from M. citrifolia fruit in USA were lunched (Santhosh Aruna et al., 2013). Later, in 1996, M. citrifolia juice was introduced as a wellness drink, due to numerous reports stating its therapeutic effects (Kamiya et al., 2009). In 2003, the fruit juice of M. citrifolia was approved as a novel food by the European commission; however, this approval was limited to the Tahitian fruit juice and not to other products (Potterat and Hamburger, 2007). Amazingly, even with the absence of specific mechanisms of action for the claimed M. citrifolia effects (Kamiya et al., 2009), yet the market annual sales of M. citrifolia products claimed to reach up to US $ 1.3 billion (Potterat and Hamburger, 2007).

2 Chemical constituents

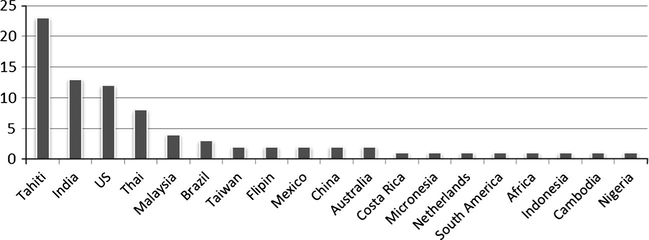

Almost 200 phytochemicals were identified and isolated from different parts of M. citrifolia (Singh, 2012), however, up to date, the complete phytochemical composition of the M. citrifolia has not been fully reported. The chemical compositions and their concentrations are related significantly not only to the part of the plant but also to its country of origin (Deng et al., 2010), and to the harvesting season (Iloki Assanga et al., 2013), however, the optimization of agricultural/post-harvest practices or processing technologies have been neglected (Chan-Blanco et al., 2006). Fig. 1 illustrates the most studied harvesting locations and brands of the M. citrifolia around the world.

The most studied harvest locations and brands of M. citrifolia all over the world based on our review.

Under favorable conditions, the plant can bear fruit about nine months to one year after planting, where M. citrifolia plots are usually harvested two or three times per month and one hectare of M. citrifolia can yield around 35 tons of juice. Fruits are usually harvested at different stages, but most processors buy them at the “hard white” stage for juice production (Chan-Blanco et al., 2006). The evolution of fruits phytochemical constituents, as well as isolation and identification of the bioactive compounds with their activity upon the different stages is not fully addressed yet. In one study, Mexican M. citrifolia fruit was assessed during its different maturity stages (1–4) for its phytochemical constituents, finding that it has high levels of soluble protein, carbohydrates, ascorbic acid, rutin and phenols, with an independent profile of season (Lewis Luján et al., 2014). It was suggested that the exposure of the fruits to light or high temperatures immediately after harvest does not affect their overall quality (Chan-Blanco et al., 2006), yet, precise studies are required to specify under which temperature and light conditions fruit quality remains stable.

According to a Malaysian medicinal plants book, M. citrifolia chemical constituents are: 5,7-Acacetin-7-O-β-D(+)-glycopyranoside, ajmalicine isomers, alizarin, asperuloside, asperulosidic acid, chrysophanol (1,8-dihydroxy-3-methylanthraquinone), damnacanthol, digoxin, 5,6-dihydroxylucidin, 5,6-dihydroxylucidin-3-β-primeveroside, 5,7-dimethylapigenin- 4′-O-β-D(+)-galacto pyranoside, lucidin, lucidin-3-β-primeveroside, 2-methyl-3,5,6-trihydroxy anthraquinone, 3-hydroxymorindone, 3-hydroxymorindone-6-β-primereroside, α-methoxyalizarin, 2-methyl-3,5,6-trihydroxyanthraquinone-6-β-primeveroside, mono-ethoxyrubiadin, morindadiol, morindin, morindone (1,5,6-trihydroxy-2- methylanthraquinone), morindone-6-β-primeveroside, nordamnacanthal, quinoline, rubiadin, rubiadin 1-methyl ether, saronjidiol, ursolic acid, alkaloids, anthraquinones and their glycosides, caproic acid, caprylic acid, fatty acids and alcohols (C5-9), flavones glycosides, flavonoids, glucose (β-D-glucopyranose), indoles, purines, and β-sitosterol (Krishnaiah et al., 2012).

Till now, 51 volatile compounds were identified in the M. citrifolia ripe fruit, without clear specification of the fruit harvest locations and stage conditions. These compounds include organic acids such as octanoic and hexanoic acids, alcohols including 3-methyl-3-butene-1-ol, and esters like methyl octanoate, and methyl decanoate, as well as ketones as 2-heptanone, and lactones (E)-6-dodeceno-ɣ-lactone (Farine et al., 1996).

The lyophilized Tahitian M. citrifolia fruit juice contains trace elements including manganese (6.11 ± 0.21 g L−1), copper (2.22 ± 0.31 g L−1), molybdenum (0.160 ± 0.004 g L−1), and cobalt (0.0474 ± 0.0006 g L−1) (Rybak and Ruzik, 2013). Minerals including potassium, sulfur, calcium, phosphorus and traces of selenium were reported in the fruit juice of M. citrifolia from Cambodia (Chunhieng, 2003), while vitamins such as ascorbic acid and pro-vitamin A were detected in the Indian and Micronesian M. citrifolia fruit (Krishnaiah et al., 2012; Shovic and Whistler, 2001). Thai concentrated M. citrifolia fruit juice total fatty acid content reported to be 149 ± 8.735 mg/100 g, and its amino acids content was as follows: glutamate, alanine, arginine (range 20–26 mg/100 g); glycine, cysteine, methionine, tyrosine, phenylalanine, lysine (range 9.0–14.5 mg/100 g) and threonine, serine, valine, isoleucine, leucine (range 3–6.5 mg/100 g). The highest and lowest content was aspartate 34.9 (mg/100 g) and histidine (2.0 mg/100 g), respectively (Rawangban et al., 2011). Phenolic compounds are also dominating in the fruit of M. citrifolia, including damnacanthal, scopoletin, morindone, alizarin, aucubin, nordamnacanthal, rubiadin, rubiadin-1-methyl ether, and anthraquinone glycosides (Mahanthesh et al., 2013). A phytochemical screening for the presence of secondary metabolite was conducted on the Indian M. citrifolia fruit aqueous, ethanol and methanol extracts detecting steroids, cardiac glycosides, phenol, tannins, terpenoids, alkaloids, carbohydrates, flavonoids, reducing sugar, lipids and fats in all types of extracts, while saponins in aqueous and methanol extracts, as well as acidic compounds in aqueous extract only (Nagalingam et al., 2012), Brazilian M. citrifolia fresh fruit pulp showed the presence of reducing sugars mainly glucose, fructose and sucrose, and suggested large amount of minerals (Da Silva et al., 2012). Recently, phytochemical screenings of different commercial Nigerian M. citrifolia juice extracts confirmed the presence of secondary metabolites such as reducing sugars, phenols, tannins, flavonoids, saponins, glycosides, steroids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and acidic components, and the study also reported the absence of anthraquinones, phylobatannins and resins (Anugweje, 2015). Brazilian aqueous extracts from M. citrifolia leaves phytochemical screening showed the presence of alkaloids, coumarins, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, steroids, and triterpenoids (Serafini et al., 2011). The phytochemical studies of Malaysian M. citrifolia roots dichloromethane extract have resulted in the isolation and characterization of ten anthraquinone including: I-hydroxy-2methylanthraquinone, nordamnacanthal, damnacanthal, morindone, rubiadin-I-methyl ether, soranjidiol, rubiadin and damnacanthol (Saidan, 2009). Furthermore screening led to the identification of twenty compounds from the Chinese dried M. citrifolia seeds ethanol extract including daucosterol, ursolic acid, 19-hydroxyl-ursolic acid, 1,5,15-trimethylmorindol, 5,15-dimethyl-morindol, scopoletin, 3,3′-bisdemethylpinoresinol, 3,4,3′4′-tetrahydroxy-9,7′α-epoxylignano-7α,9′-lactone, americanin D, americanin A, americanin, isoprincepin, deacetyl- asperulosidic acid, loganic acid, asperulosidic acid, rhodolatouside, quercetin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside, 4-ethyl-2-hydroxyl-succinate, 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furancarboxaldehyde, 3-methylbut-3-enyl-6-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-β-D-glucopyranoside (Yang et al., 2009). For a novel and accurate outcomes, M. citrifolia studies quality can be improved through developing identification markers for its chemical components and characterize their chemical structures on TLC, HPTLC, HPLC, NMR spectroscopy (Saminathan et al., 2014). Table 1 summarizes the major chemical components of M. citrifolia different organs and their phytochemical classification and proven activities.

Plant part

Compound

Chemical classification

Activities/uses

Reference

Leaf

Americanin A

Lignan

Larvicidal, antioxidant

Kovendan et al. (2012) and Kovendana et al. (2014)

Proline

Amino acid

A source of essential and conditional amino acids

Shovic and Whistler (2001), Elkins (1998) and Sang et al. (2001)

Leucine

Cysteine

Methionine

Glycine

Histidine

Isolucine

Glutamic acid

Phenylalanine

Serine

Threonine

Tryptophan

Tyrosine

Arginine

Valine

Quercetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

Flavonoids

Antimicrobial

Chan-Blanco et al. (2006) and Sang et al. (2001)

Quercetin-3-O-a-L- rhamnopyranosyl-(1-6)-β-D-glucopyranoside

Ursolic acid

Triterpenoids

Anticancer

Elkins (1998), Sang et al. (2001) and Dittmar (1993)

β-sitosterol

Sterols

Lowering blood cholesterol and stimulating immune system

Shovic and Whistler (2001) and Wang et al. (2002)

Citrifolinoside B

Iridois

Suppressing UVB-induced Activator Protein-1 (AP-1) activity

Sang et al. (2001)

Kaempferolm 3-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1-2)-a-Lrhamnopyranosyl-(1-6)-β-D-galactopyranoside

Chlorophyll derivatives

Might be involved in lowering blood glucose levels

Sang et al. (2001)

Scopoletin

A coumarin derivative

Anti-proliferative effects on cancer

Kamiya et al. (2010) and Mohd Zin et al. (2007)

Fruit

Octanoic (caprylic) acid

Fatty acid

Antifungal

Elkins (1998), Dittmar (1993), Wang et al. (1999, 2002), Mohd Zin et al. (2007), Jayaraman et al. (2008), Liu et al. (2001) and Zhang et al. (2014)

Hexanoic acid

Antifungal, Antioxidant

Caproic acid

Antifungal

Vitamin C

Vitamins

Antioxidant

Zin et al. (2002) and West et al. (2011)

Vitamin E

Nutritional

Niacin

Nutritional

Manganese, Selenium

Trace elements

Nutritional

Zin et al. (2002) and West et al. (2011)

Asperulosidic acid

Iridoid

Antibacterial

West et al. (2012)

Quercetin

Flavonoids

Anti-inflammatory, Lipoxygenase inhibitor

Elkins (1998), Sang et al. (2001), Liu et al. (2001), Morton (1992), Yu (2004) and Deng et al. (2007b)

2,6-di-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl 1-O-octanoyl-β-D glucopyranose

Fatty acid ester

Melanogenesis suppression, antioxidant

Nelson (2006), Kamiya et al. (2010), Jayaraman et al. (2008) and Lin et al. (2013)

6-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl-1-O-octanoyl-β-D glucopyranose

Liu et al. (2001), Wang et al. (1999), Zhang et al. (2014) and Akihisa et al. (2012)

Damnacanthal

Anthraquinones

Anti-cancer

Chan-Blanco et al. (2006) and Kamata et al. (2006)

Americanin A

Lignan

Potent antioxidant

Su et al. (2005)

Root

8-hydroxy-8-methoxy-2-methyl-anthraquinone, rubiadin

Anthraquinone

Antiviral

Elkins (1998), Morton (1992) and Inoue et al. (1981)

1,3-dihydroxy-6-methyl anthraquinone

Morenone 1

Anti-cancer

Elkins (1998) and Solomon (1999)

Morenone 2

Asperuloside (rubichloric acid)

Iridoid

Anti-bacterial

Bushnell et al. (1950)

Quercetin

Flavonoids

Antioxidant, anti-dyslipidemic

Mohd Zin et al. (2007) and Mandukhail et al. (2010)

Scopoletin

Coumarin derivative

Antibacterial

Sang et al. (2001) and Jensen et al. (2005)

Damnacanthal

Anthraquinones

Anti-carcinogenic

Nualsanit et al. (2012)

3 Industrial uses

M. citrifolia is involved in various green industrial sectors, including the following:

3.1 Natural preservative

M. citrifolia is recognized as a novel food ingredient under the name of Noni fruit puree (Efsa, 2009), however, food industry is mainly interested in Tahitian M. citrifolia due to its leaf, fruit and root antioxidant properties which are similar to vitamin E, and they also contain butylated hydroxytoluene (a phenol derivative) which has a natural preservative activity (Zin et al., 2002), and was effective in blocking warmed-over flavor in formerly stewed beef pies, by reducing lipid oxidation, as well as enhancing color stability and the shelf life of the final aerobically wrapped pies (Nathan et al., 2012). Despite of the proven in vivo safety of Tahitian M. citrifolia as a food ingredient (West et al., 2011), yet, the unpleasant off-taste of its puree might restrict its use as a preservative (Nathan et al., 2012). Interestingly, the addition of maltodextrin to the M. citrifolia pulp powder (Fabra et al., 2011), as well as to the spray dried seedless M. citrifolia fruit powder, successfully eliminated M. citrifolia bad smell and unpleasant taste, and increased its resistance to humidity (Anwar and Arsyadi, 2007), yet no study has observed the effect of maltodextrin complexation with M. citrifolia on enhancing its preservative effects with less or no distasteful flavor and odor.

3.2 M. citrifolia juice

The M. citrifolia juice products are a corner stone within its industrial sector. Fresh Noni juice is obtained by compressing the fruits immediately after harvesting (Newton, 2002), whereas homemade juice is prepared by letting the fruits decompose naturally (Brown, 2012), and commercial juice is made by fruit fermentation (Nelson, 2006). The chemical composition of M. citrifolia juice depends majorly upon the method of juice extraction. The physiochemical screening of the fermented Indian M. citrifolia fruit showed that it contains anthraquinones, saponins, and scopoletin (Satwadhar et al., 2011), while the bioactive screening of the Thai M. citrifolia fermented fruit juice recorded a superior vitamins content (C, B1, B2, B3, B12) in comparison to the vitamin content of the American M. citrifolia fruit, it was also containing alkaloids, anthraquinones, antioxidants, essential oils, flavonoids, saponins, scopoletin and sugars, and these results were congruent to the content of the commercial Thai fruit juice content (Nandhasri et al., 2005). To overcome problems associated with transport and storage, M. citrifolia juice was concentrated (Valdés et al., 2009). However, its processing methods and storage conditions influence juice stability. For example, heat affects the organoleptic nature of the concentrated M. citrifolia juice (Valdés et al., 2009), while a fermentation process for 90 days caused about 90% reduction of its radical-scavenging activity (RSA), and a dryness at 50 °C reduced the RSA by 20%, as for freshly prepared M. citrifolia juice, the RSA is decreased by more than 90% if it is stored at 24 °C for 90 days, whereas the RSA of the juice or powder is reduced by 10–55% when stored for 90 days at −18 °C and 4 °C, respectively (Yang et al., 2007). M. citrifolia beverages taste was enhanced in an economic juice recipe which was prepared by mixing 10% of fermented juice extract of an Indian M. citrifolia ripe fruit with 14% total suspended solids (T.S.S.) and 2% ginger extract (Joshi et al., 2012). Only one published research has studied the stability of M. citrifolia final products where the concentrated Thai fruit juices and its dried powders showed stability for 451 days (Rawangban et al., 2011). This is indicating that stability factor should be considered more in future studies.

Many of M. citrifolia commercial juice parameters should be fixed including its concentrations variations, the prevalent bioactive component in the fermented products, pasteurization impact on these bioactive compounds, and the specification regarding the juice source for being fermented, and for how long, and pasteurized or unpasteurized (Brown, 2012).

3.3 M. citrifolia probiotic juice

Seedless fermented M. citrifolia fruit juice from Taiwan showed potentials for the production of probiotic which was produced by reacting M. citrifolia juice (as a raw substrate) with lactic acid bacteria (Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus plantarum) or Bifido-bacteria (Bifidobacterium longum). After 48 h. of fermentation, all tested strains grew well on M. citrifolia juice and colony-forming reached nearly 109 units/ml. Lactobacillus casei produced less lactic acid than Bifidobacterium longum, whereas Lactobacillus plantarum, Bifidobacterium longum and Lactobacillus plantarum survived under low-pH conditions in a cold storage at 4 °C for a period of 4 weeks. The results indicated that Bifidobacterium longum and Lactobacillus plantarum bacteria are selective for producing a probiotic M. citrifolia juice (Wang et al., 2009a).

3.4 Natural source of medicines

Scientists are looking at the M. citrifolia as a natural source for the medicinal production by using a bioreactor cultivation technology to produce specific medicinal compounds at a rate similar or superior to natural grown M. citrifolia. Data have shown that casual root cultures of M. citrifolia could be a useful way for the commercial production of biotechnology based chemicals such as rubiadin, flavonoids, phenolics and anthraquinones (Baque et al., 2012).

The aqueous root extract of Indian M. citrifolia was also used in nanobiotechnology field for the synthesis of ecological noble metal nanoparticles due to the presence of anthraquinones. Silver nanoparticles were prepared by the reduction of silver nitrate into silver ions upon adding M. citrifolia root aqueous extract and incubating for an overnight to yield particles between 30 and 55 nm with a cytotoxic activity against the HeLa cell lines (Suman et al., 2013). Gold nanoparticles were prepared by mixing M. citrifolia root aqueous extract with aqueous solution of chloroauric acid to produce gold nanoparticles. This preparation was predicted to have a higher anticancer activity due to its smaller size (12.17–38.26 nm) (Suman et al., 2014). However, before proceeding in this drug development program, a comprehensive phytochemical profiling of M. citrifolia, pharmaco-therapeutics, toxicity and clinical trials are needed (Singh, 2012).

3.5 Natural source of chemical reagents

Acetone extract of Thai M. citrifolia dried roots was reported as a source of natural reagents for the flow injection spectrophotometric technique in quantitative assays. Extract containing anthraquinones like alizarin was successfully detecting aluminum at a concentration range of 0.1–1.0 mg L−1 in instant tea samples. Anthraquinone compounds were acting as a complexing agent by reacting with aluminum and forming a reddish complex which could be measured at 499.0 nm (Tontrong et al., 2012). The potentials of M. citrifolia in being a green chemical reagent opened a new era of research in the analytical and biochemical fields.

3.6 Green insecticidal

The mosquitocidal activity of Indian M. citrifolia was successfully proved at various concentrations range (100–500 ppm). The activities of hexane, chloroform, acetone, methanol, and water leaf extracts were sequentially observed on the developing phases of malarial vector, Anopheles stephensi, Dengue vector, Aedes aegypti and Filarial vector culex quinquefasciatus. The studies were conducted for 24 and 48 h. showing that methanol extract had the highest larval and pupal mortality rate (Kovendan et al., 2012). The Indian M. citrifolia leaf ethanol extract was also reported for its larvicidal and pupicidal activities against the malarial vector Anopheles stephensi either alone at a range of 18.30–97.78 mg/L, or as a combination of M. citrifolia at a concentration range of 16.73–138.10 mg/L with Metarhizium anisopliae (an entomopathogenic fungi) at a concentration range of 150.15–806.67 mg/mL. The combination therapy showed the highest larval and pupal mortality rate (Kovendana et al., 2014).

4 Pharmacological activities

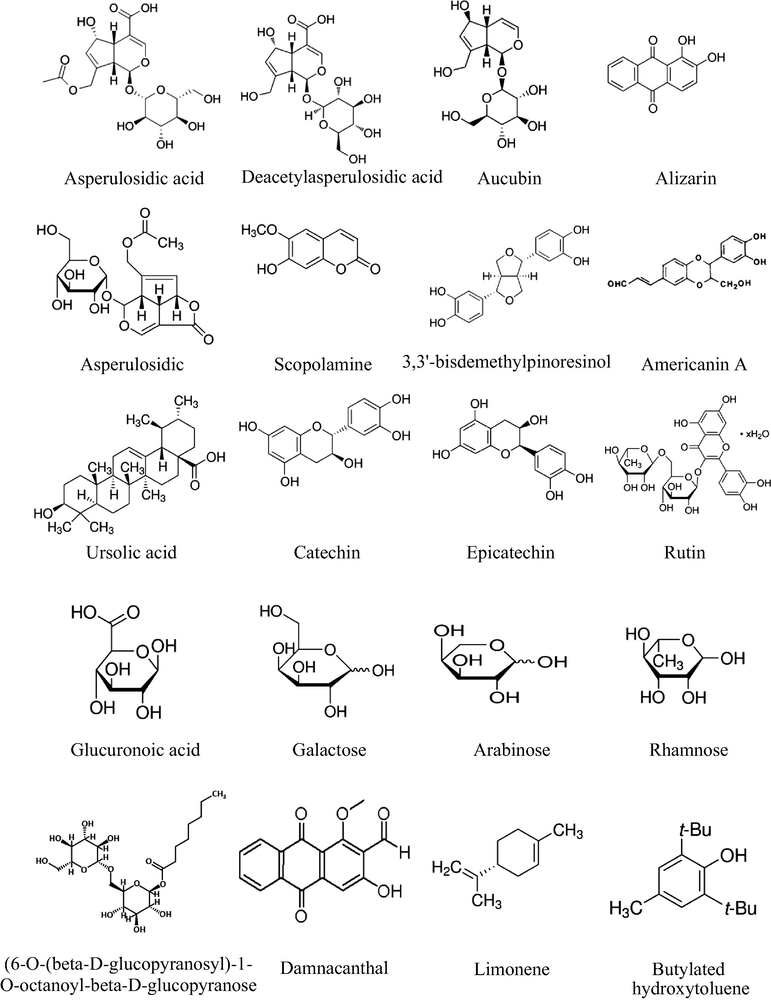

According to the European Commission 5th framework program quality of life, there are no systematic reviews or meta-analyses that have been published about the M. citrifolia wide ranges of therapeutical claims (Pilkington and The CAM-Cancer Consortium, 2015). In the next paragraph, the discussed therapeutic indications are linked to a clear scientific evidence of either in vitro and in vivo studies, or clinical trials, with a specification about the responsible phytochemical component of each activity, as well as the extracting solvent and the used part of the plant along with its country of origin and Fig. 2 summarizes the chemical structures of M. citrifolia most common pharmacologically active ingredients.

Summary of the chemical structures of M. citrifolia most common pharmacologically active ingredients.

4.1 Antimicrobial and antiseptic activity

The anti-microbial activity of Tahitian M. citrifolia fruit in a methanol partitioned with n-butanol extract was assessed in an in vitro assay on Escherichia coli, Candida albicans and Staphylococcus aureus. Candida albican was the most sensitive to M. citrifolia antimicrobial activity, while Staphylococcus aureus sensitivity was the lowest. This activity was linked to the rich iridoid content of the fruit, particularly, deacetylasperulosidic acid and asperulosidic acid (West et al., 2012). Another anti-microbial in vitro assay was conducted on methanol, ethyl acetate and hexane Indian M. citrifolia fruit extracts against a wide range of organisms including the following: Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, Lactococcus lactis, Streptococcus thermophilus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhi, Escherichia coli, Vibrio harveyi, Klebsiella pneumonia, Shigella flexneri, Salmonella paratyphi A, Aeromonas hydrophila, Vibrio cholera, Chromobacterium violaceum, and Enterococcus faecalis. Among the three tested extracts, methanol extract was the most effective, ethyl acetate was effective against all the tested micro-organisms except for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumonia, and hexane extract was ineffective against all tested microorganisms (Jayaraman et al., 2008). The antimicrobial activities of the Australian M. citrifolia leaf against Salmonella, Enterica serovar typhi (S76), Staphylococcus aureus (B313) and Myco. phlei CSL, were attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds such as acubin, l-asperuloside, alizarin and scopoletin (Atkinson, 1956). On the other hand, an in vitro study reported M. citrifolia as an oral antiseptic through teeth inoculation with Enterococcus faecalis at 37 °C in a CO2 atmosphere for 30 days, and then treating them with Tahitian noni fruit juice (TNJ), NaOCl, chlorhexidine gluconate (CHX), and TNJ/CHX respectively, followed by a final flush with 17% ethylene diamine tetra acetic acid (EDTA). Upon scanning the teeth with electron microscopy, and examining the removed smear layer, TNJ efficacy found to be similar to NaOCl when it is used together with EDTA, authors recommended preclinical and clinical trials to evaluate TNJ biocompatibility and safety (Murray et al., 2008). The previous results were confirmed with another study which additionally revealed TNJ safety on the micro-hardness property of root canal dentin (Saghiri et al., 2013).

4.2 Antifungal activity

The antifungal properties of Indian M. citrifolia fruit extract in three different solvents, methanol, ethyl acetate and hexane were tested in an in vitro assay on different fungi including Candida albicans, Aspergillus niger, Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Penicillium species, Fusarium species, Aspergillus fumigates, Rhizopus species, Aspergillus flavus, and Mucor species. The maximum inhibition was in the methanol and ethyl acetate extract of 79.3% and 62.06%, respectively against Trichophyton mentagrophytes, while almost 50% inhibition was recorded in the methanol extract against Penicillium, Fusarium and Rhizopus species, and none of the extracts were active against either Candida albicans or Aspergillus species (Jayaraman et al., 2008).

Despite the fact that in vitro results for anti-bacterial and anti-fungal studies are promising yet further in vivo and clinical research are highly recommended using different routes of administrations.

4.3 Antioxidant activity

Australian M. citrifolia fruit juice showed an anti-oxidant activity 2.8 and 1.4 times higher than vitamin C and pycnogenol, respectively. This antioxidant activity was similar to grape seed powder at the daily dose recommended by U.S. RDAs and manufacturers (Atkinson, 1956). Neolignan and americanin A were the potent antioxidant constituent of the American M. citrifolia fruit (Su et al., 2005). The optimum magnitudes of radical scavenging activity (RSA), and total phenolic content of Malaysian seedless M. citrifolia fruit methanol extract were 55.60% and 43.18 mg GAE/10 g, respectively (Krishnaiah et al., 2015). In other study, M. citrifolia anti-oxidant activity was evaluated as a natural anti-pigmentation agent by observing the effect of 50% ethanol extracts of Tahitian M. citrifolia fruit flesh, leaves, and seeds, on the tyrosinase enzyme responsible for controlling the production of melanin. The in vitro test was carried out using tyrosinase inhibitory assay, showing that seed extract had stronger tyrosinase inhibitory (from 20 to 500 μg/ml) and antioxidant activity than the fruit (500 μg/ml), while leaf extract did not have any tyrosinase inhibitory activity at any concentration. The tyrosinase inhibitory activity was linked to the presence of lignans in M. citrifolia, particularly 3,3′-bisdemethylpinoresinol and americanin A (Masuda et al., 2009). The same seed extract was found to have anti-photoaging activity at concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 1.0 mg/ml (Matsuda et al., 2013), and also inhibited blood hemagglutination at concentrations ranging from 50 to 500 μg/ml (Matsuda et al., 2011); ursolic acid was the responsible chemical for the both activities.

M. citrifolia anti-oxidant property was also linked to other health enhancements activities. In an in vitro evaluation of methanol, chloroform, ethanol, butanol and aqueous extract of Indonesian M. citrifolia fruit, all extracts were able to inhibit Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation due to M. citrifolia lignans, such as americanol A, americanin A, americanoic acid A, morindolin, and isoprincepin (Kamiya et al., 2004). Other in vitro study suggested Malaysian M. citrifolia leaf ethanol extract was a highly effective natural anti-obesity supplement than its fruit. Leaf and fruit methanol extracts inhibited the lipoprotein lipase activity 66% ± 2.1 and 54.5% ± 2.5%, respectively. Both extracts contain high levels of phenolic constituents including catechin, epicatechin and rutin which acted synergistically to demonstrate this activity (Pak-Dek et al., 2008). Furthermore, Tahitian M. citrifolia juice was able to reduce obesity related to insulin resistance in an in vitro mouse muscle cells C2C12 culture, by inhibiting the reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial damage (Nerurkar and Eck, 2008).

A clinical study was carried out on twenty-two participants (16 women and 6 men), aged between 18 and 65 years old for 12 weeks trial of a weight-loss program with a fixed study factors including Tahitian M. citrifolia -based dietary supplements (US brand), daily calorie reduction, and exercise. All participants experienced weight loss with significant decrease in fat mass without side effects. However, the researchers suggested that further clinical studies should be carried out to include more male participants, and ethnic diversity (Palu et al., 2011). Antidyslipidemia activity was related to M. citrifolia antioxidant property in the aqueous-ethanol extracts of its Indian fruits, leaves, and roots in Sprague–Dawley rats and mice of either sex, all these different parts extracts caused significant reduction in total cholesterol, triglyceride (TC), low density lipoprotein-cholesterol, atherogenic index and TC/HDL ratio. There were no behavioral changes, toxicity or mortality occurred up to 10 g/kg of M. citrifolia intake, as compared to control group (Mandukhail et al., 2010). Hepato-protective effects M. citrifolia was also affined to anti-oxidant effects in its Taiwanese fermented fruit juice at a dose range of 3–9 mL NJ/kg BW on hamsters fed with a high-fat diet (Lin et al., 2013).

4.4 Anti-inflammatory activity

In an in vitro study, the anti-inflammatory activity was detected in the Costa Rican M. citrifolia fruit juice by measuring its direct inhibitory activities on cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and -2 (Dussossoy et al., 2011). The in vivo study on Tahitian M. citrifolia fruit juice showed a reduction in the induced carrageenan paw edema in rats, revealing a strong anti-inflammatory effect comparable to that of non-steroidal inflammatory drugs, such as acetylsalicylic acid, indomethacin and celecoxib, without side effects (Su et al., 2001). Tahitian M. citrifolia seeds oil showed topical anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting both COX-2 and 5-LOX enzymes in an in vitro assay at concentrations of 0.5 and 1 mg/ml (Palu et al., 2012). The topical safety of the M. citrifolia seed oil was evaluated on 49 adult volunteers using the patch test whereas topical comedogenic effect of the seed oil was studied on 23 Caucasian adolescent volunteers. Both studies were conducted for four weeks, and results indicated that the topical M. citrifolia seed oil was safe and non-comedogenic, in addition to showing a very little risk of causing allergic dermatitis which could be due to seed high fatty acids content, mainly linoleic acid (Palu et al., 2012).

A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial using a M. citrifolia dietary supplement (U.S brand) was first performed on 100 women above 18 years old, however, only 80 women completed the study. The aim of the study was to find out the potential natural anti-inflammatory efficacy of M. citrifolia. This study included some variables such as age, parity, body mass index, pain, menstrual blood loss, hemoglobin, packed cell volume and erythrocyte sedimentation rate before and after treatment. Patients were observed for three menstrual cycles after being exposed to 400 mg of M. citrifolia capsules or placebo (38 in the placebo group and 42 in the M. citrifolia group) and there were no significant differences in any of the variables studied between treated and placebo group, further studies using higher doses of M. citrifolia with a larger sample size were recommended (Fletcher et al., 2013).

4.5 Anti-arthritic activity

An Indian brand of M. citrifolia fruit juice was orally administered to arthritic rats at doses 1.8 ml/kg and 3.6 ml/kg, and showed a dose dependent significant reduction in paw thickness, arthritic index, secondary lesions, mononuclear infiltration and pannus formation. Similar changes were also recorded by the administration of indomethacin except for the reduction of secondary lesions. The anti-arthritic activity could be due to the presence of flavonoids and phenols (Saraswathi et al., 2012). Precise investigations can add a therapeutical value by specifying the chemicals owning such activities and their effective and safe doses.

4.6 Anti-cancer activity

M. citrifolia natural components are mostly reported as a natural anticancer cure where sulphated polysaccharide stops metastasis by destabilizing the interaction between glycosaminoglycan and certain proteins (Liu et al., 2000) while damnacanthal inhibits the formation of tumors either by interfering with the growth of ras gene activation (Hiramatsu et al., 1993), or by increasing apoptosis in human colorectal cancer cell lines (Nualsanit et al., 2012). Alizarin has an antiangiogenic effect through blocking blood circulation to malignant tumors. Limonene prevents mammary, liver, and lung cancers by stimulating thymus gland to secrete more T cells which destroys the carcinoma cells. Last but not the least, ursolic acid inhibits the growth of cancerous cells and induces apoptosis by modulating the body immune process (Lv et al., 2011).

4.6.1 In vitro studies

Thai M. citrifolia fresh and dried leaf dichloromethane extracts were reported to be more effective and probably safer in treating cancer than M. citrifolia pure compounds such as damnacanthal, rutin, and scopoletin due to the extracts higher safety ratios. Four human cancer cell lines (epidermoid carcinoma, cervical carcinoma, breast carcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma), and a Vero (African green monkey kidney) cell lines were used in the study. Both M. citrifolia extracts showed an inhibitory effect on epidermoid carcinoma and cervical carcinoma cells, while the pure compounds, rutin and scopoletin, showed lower anti-proliferative effects on all human cancer cell lines. However, only damnacanthal had potent cytotoxic effects against all human cancer cell lines as well as African green monkey kidney cell lines (Kamiya et al., 2010).

Furthermore, both pure polysaccharide, and aqueous extract from the root of Chinese M. citrifolia were cultured separately in a blood serum with osteoblasts (induced by trans-retinoic acid) to assess their cytotoxic role. The pure polysaccharides showed higher anticancer activity than the root aqueous extract (Li et al., 2008b), yet no specific screening was conducted on the type and structure of these polysaccharides. Furthermore, the damnacanthal which was isolated from the roots of Thai M. citrifolia had anticolorectal cancer activity as it showed a systematic cancer-suppressing capability in colorectal tumorigenesis (Nualsanit et al., 2012). Likewise, scientists extracted and scanned 18 different anthraquinones from the air dried powders of Hawaiian M. citrifolia roots for its anti-cancer activity using MTT cell proliferation assay. All the anthraquinones showed an anti-proliferation activity on both human lung cancer and colon cancer cells, specifically 1,3-dihydroxy-2-formylanthraquinone had the highest effects (Lv et al., 2011). Anthraquinone anti-cancer activity is not fully addressed, but it could be due to either aldehyde or methoxymethyl group at the C-2 position (Kamiya et al., 2010).

Anti-genotoxic potential of M. citrifolia juice was tested on human lymphocyte cultures at 200, 250, 300, 350 μl/ml per culture, showed a potent anti-genotoxic activity reflecting its possible anti-carcinogen effects at the initiation stage (Li et al., 2008b), however, further studies should specify the M. citrifolia juice ingredient(s) which is causing this effect, taking in consideration to evaluate wider concentrations range than the previously used ones on human lymphocyte cultures or even studying other models. M. citrifolia fruits ethanol extract from Kauai and Hawaii islands contains a polysaccharide rich substances (i.e. glucuronic acid, galactose, arabinose and rhamnose), which had immunomodulatory and anti-tumor effects on Lewis lung carcinoma cell lines (Hirazumi and Furusawa, 1999). Other two glycosides (6-O-(β-D-glucopyranosyl)-1-O-octanoyl-β-D-glucopyranose and asperulosidic acid) which were isolated from M. citrifolia fruit juice, showed an efficacy in suppressing the induced transformation in mouse epidermal JB6 cell line (Liu et al., 2001).

The crude extract of Hawaiian M. citrifolia fruit was reported to inhibit neuroblastoma (36%) and breast cancer (29%) cell lines effectively in comparison to hamster (6%) or human laryngeal (13%) cell lines, but it had no effects on green monkey kidney (0%) cell line (Arpornsuwan and Punjanon, 2006). In addition, the fermented Hawaiian M. citrifolia juice acted as an anti-proliferative for dendritic cells by stimulating both splenocytes, and B cells in order to produce IgG and IgM (Wong, 2004).

HeLa and SiHa cell lines were treated with either Indian M. citrifolia fruit juice, cisplatin (an anti-cervical cancer treatment), or their combination and showed that all the tested preparations were able to induce apoptosis in the examined cell lines. However, cisplatin showed slightly higher cell killing rate compared to M. citrifolia fruit juice, whereas their combination showed additive effects (Gupta et al., 2013). Furthermore, two lignans, 3,3′-bisdemethylpinoresinol (5 μM) and americanin A (200 μM), from the Tahitian M. citrifolia seed ethanol extract were evaluated for melanogenesis inhibitory properties, using B16 murine melanoma cells as a melanogenesis test model and α-melanocyte hormone (α-MSH) to stimulate the cells, before incubating them for 72 h. Both lignans were able to inhibit α-MSH-stimulated melanogenesis, however, 3,3′-bisdemethylpinoresinol effect was superior, and the suggested mechanism of action was through tyrosinase suppression (Masuda et al., 2012).

4.6.2 In vivo studies

Rats with artificially induced cancer in specific organs were fed with 10% M. citrifolia juice in their drinking water. After one week DNA-adduct formation was reduced depending on sex and organ. The reduction rates in organs of female rats were heart 30%, liver 42%, lungs 41% and kidneys 80% whereas the reduction rates in organs of male rats were heart 60%, liver 70%, lungs 50% and kidneys 90% (Chan-Blanco et al., 2006). In other study, mice subjected to sarcoma tumor cells demonstrated synergistic beneficial effects after being treated with Hawaiian M. citrifolia fruit ethanol precipitate combined with some anti-cancer drugs including cisplatin, adriamycin, mitomycin-C, bleomycin, etoposide, 5-fluorouracil, vincristine or camptothecin. However, no beneficial effects were recorded when M. citrifolia combined with paclitaxel, cytosine arabinoside, or immunosuppressive anticancer drugs such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate or 6-thioguanine. In contrast, mice treated with the fruit ethanol precipitate alone showed a cure rate of 25–45% (Furusawa et al., 2003). The freeze-dried Tahitian M. citrifolia fruit was also reported to prevent chemically induced tumorigenesis in rat esophagus (Stoner et al., 2010).

Li et al. (2008a,b) investigated antitumor effect of fermented Hawaiian Noni M. citrifolia exudate (500 μl/mouse/day) administered intraperitoneally to sarcoma 180 ascites mouse model. It was discovered that more than 85% of nude mice were tumor free in one and half months after tumor inoculation, versus 100% of the control mice died within 30 days of tumor inoculation (Li et al., 2008a). Another antitumor study was conducted on three groups of eight mice each was induced with Ehrlich ascites tumor. The first, second and third groups were given oral M. citrifolia juice (a commercial product from the Netherlands), doxorubicin (a potent anticancer drug), and a combination of both, respectively. The results suggested that oral M. citrifolia fruit juice may be useful in the treatment of breast cancer, either alone or in combination with doxorubicin (Taskin et al., 2009). Moreover, Tahitian M. citrifolia juice significantly reduced tumor weight and volume in mice, thus it might be useful in enhancing the treatment responses in women with the existing HER2/neu breast cancer (human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 gene) (Clafshenkel William et al., 2012). In contrast, Tahitian M. citrifolia fruit juice administered to MMTV-neu transgenic mice had no effect on mammary tumor latency, incidence, multiplicity, and metastatic, suggesting that the M. citrifolia juice did not increase or decrease breast cancer risk in women, but it could be taken as a dietary supplement for other benefits (Clafshenkel William et al., 2012). Thus, further work is highly recommended to clarify the role of Tahitian M. citrifolia juice and its other extracts in treating breast cancer.

4.6.3 Clinical trials

In one trial, Tahitian M. citrifolia fruit juice with a dose of 1 and 4 oz daily had reduced cancer risk among 203 heavy cigarette smokers. The data showed a significant reduction of aromatic DNA adducts levels in all participants by 44.9% after drinking the juice for 1 month. Dose-dependent analyses of aromatic DNA adduct levels revealed a reduction of 49.7% in the 1-oz dose group, and 37.6% in the 4-oz dose group. However, gender-specific analyses showed no significant differences in the 4-oz dose groups, while in the 1-oz dose group showed 43.1% reduction in females compared to 56.1% in males. The suggested mechanism of cancer reduction was by blocking carcinogen-DNA binding, or excising DNA adducts from genomic DNA (Wang et al., 2009b).

Only two cancer cases were reported to use M. citrifolia. Case 1 was about a 69 year old male with gastric cancer who was predicted to die within few months without surgical intervention. The patient chose to take homemade M. citrifolia fruit juice over the surgical operation and his condition improved within a month. After 6 months he stopped the self-treatment, and seven years later he did not have any gastric symptoms. However, a biopsy showed histological similarity to his original cancer and hence, he started taking M. citrifolia juice again but the outcome was not reported. Case 2 was about a 64 year old man with gastric cancer who underwent a gastrectomy. The cancer had spread to 17 out of 28 examined lymph nodes, and he was given 5 years to live. The patient consumed a homemade M. citrifolia juice and lived additional 16 years until he died at the age of 80 due to gastric cancer (Wong, 2004).

In a Phase I human clinical trial conducted at the Cancer Research Centre in Hawaii, 29 advanced cancer patients first started a daily dosage of 4 capsules (500 mg/capsule) from a freeze dried M. citrifolia fruit, and later it was increased up to 20 capsules (10 g) during a total 4 weeks trial which showed no tumor regression, but only a decrease in fatigue and pain interference, while the recorded maximum tolerated dose was six capsules four times daily (12 g) (Issell et al., 2009). The clinical trials' results are showing no clear role of M. citrifolia in either preventing or healing cancer disease, patients’ number should be addressed on a larger scale, with wider parameters and specifications to ameliorate the understanding of applying M. citrifolia in therapeutic and prophylactic anti-cancer medicine.

4.7 Antidiabetic activity

Indian M. citrifolia commercial fruit juice was administered orally to induced steroid diabetic (diabetes type 2) female Wistar rats, at a dose of 1.8 and 3.6 ml/kg for 10 days. The blood glucose level was significantly decreased compared to control induced diabetic rats by dexamethasone. At higher oral dose (3.6 ml/kg, twice a day) M. citrifolia fruit juice had better results than rosiglitazone, but caused liver damage in rats (Puranik et al., 2013). On the other hand, fermented juice of South American M. citrifolia also controlled blood sugar induced diabetic rats by streptozotocin. Diabetic standard animals, treated with hypoglycemic drug, glibenclamide, while diabetic experimental animals treated with 2 ml/kg M. citrifolia twice a day for 20 days exhibited a significant reduction in blood glucose level of 125 mg/dl and 150 mg/dl, respectively, as compared to untreated diabetic rats with fasting blood sugar of 360.0 mg/dl (Shivananda Nayak et al., 2011). Hypoglycemic activity of Tahitian M. citrifolia fruit Juice was investigated by administering the juice to male Sprague–Dawley rats at a dose of 1 ml/150 g body weight, twice daily for 4 weeks prior to diabetic induction using alloxan. After induction, a rise in blood glucose levels occurred but followed by a steady decline due to M. citrifolia juice prophylaxis against the diabetogenic agent, alloxan (Horsfal et al., 2008).

Based on a microarray analysis data, hypoglycemic properties of Hawaiian fermented M. citrifolia fruit juice were associated with the ability to modulate transcription factors (FoxO1) in order to regulate the gluconeogenesis process. Fermented M. citrifolia juice supplement at a dose of 1.5 μl/g body weights, twice a day for 12 weeks improved glucose and insulin tolerance as well as fasting blood glucose level in male mice. Gluconeogenic genes which are regulated by insulin including phosphoenolpyruvate C kinase and glucose-6-phosphatase were also inhibited by more than 80% (Nerurkar et al., 2012). It was suggested that M. citrifolia antidiabetic effect might be due to the stimulatory effect on the remnant ß-cells to secrete more insulin (Mustaffa et al., 2011). Saponins as well as flavonoids in M. citrifolia fruit such as rutin may also act as a secretagogue by enhancing insulin secretion (Shivananda Nayak et al., 2011). M. citrifolia is showing promising in vivo results as a natural antidiabetic agent; however scientist should pay a great concern on its safety particularly liver. If the doses are adjusted within a safe range and a proven efficacy, preclinical studies will be recommended.

4.8 Wound healing activity

Fresh Tahitian M. citrifolia leaf juice (1 mg/ml), its leaf ethanol extract (10–200 μg/ml), and its methanol and hexane fractions (10–200 μg/ml), were investigated for their topical wound healing properties. Receptors involved in wound healing such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and adenosine A2A receptor were studied on male mice. All M. citrifolia extracts showed a wound healing activity at a concentration dependent manner; however, leaf methanol extract significantly increased wound closure and reduced the half closure time in treated mice compared to the control, suggesting that the probable mechanism underlying this effect was the ligand binding to PDGF/A2A receptor which promoted wound closure (Palu et al., 2010). The promising results in this study should be confirmed through further in vivo studies on various models to draw a sharp conclusion about the healing mechanism.

4.9 Memory enhancing activity

Observations in a scopolamine induced memory impairment mice model suggested that Indian M. citrifolia dry fruit may be useful in enhancing memory at concentration range of 5–400 μg/ml. The fruit ethanol extract and its ethyl acetate fraction were containing rutin, scopoletin and quercetin, while the chloroform fraction was containing rutin and scopoletin, have showed positive effects. However, butanol fraction containing rutin alone had no effect. The mechanism of action was thought to be by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase activity, and the enhancement of the cerebral circulation (Pachauri et al., 2012). Results should be confirmed by further research to justify M. citrifolia effects on different in vivo models with precise illustration of chemicals responsible of such activity and the precise mechanism of memory enhancement.

4.10 Anxiolytic and sedative activity

A preliminary in vitro study revealed that Tahitian M. citrifolia freeze dried fruit methanol extract had anxiolytic and sedative effects by showing an affinity to the gamma-aminobutyric acid A (GABAa) inhibitory neurotransmitter receptors at a concentration of 100 μg/ml. The action could be due to the presence of competitive ligand(s) bind to the GABAa receptor as an agonist that induced anxiolytic and sedative effects. However, in vivo studies and clinical trials were recommended by the authors to confirm the newly reported activity (Deng et al., 2007a). Furthermore, a US brand of Tahitian M. citrifolia fruit juice at 10 ml/kg/day showed to have an in vivo brain protection from the stress-induced impairment of cognitive function on male ICR mice. This beneficial effect may be partly mediated by the improvement in angiogenesis induced by M. citrifolia (Muto et al., 2010). In an in vivo study on the Swiss albino mice, Malaysian M. citrifolia unripe dried fruit methanol extract was also reported for its anti-dopaminergic effects at 1, 3, 5, 10 g/kg oral doses. The suggested mechanism of action was due to the possible inhibition of the Methamphetamine-induced stereotypy behavior in a dose dependent manner. Further studies to isolate and characterize the responsible compounds for anti-psychiatric disorders were recommended (Pandy et al., 2012).

4.11 Analgesic activity

Tahitian M. citrifolia fruit juice was reported for its analgesic effect in rats by using the hotplate assay. The rats tolerated more pain after feeding with 10% or 20% M. citrifolia juice (Wang et al., 2002). In another study, the lyophilized aqueous African M. citrifolia dry root extract had also demonstrated analgesic properties at dose of 800 mg/kg given intraperitoneal injections. The analgesic activity was observed using three methods, the antagonistic action of naloxone, the writhing test, and the hotplate assay (Younos et al., 1990).

4.12 Gastric ulcer healing activity

Thai dried mature unripe M. citrifolia fruit aqueous extract was reported for its in vivo gastro-esophageal anti-inflammatory effects in rats at a range of 0.63–2.50 g/kg, with possible mechanisms of reducing the formation of acute gastric lesions, blocking the esophagus reflux and acting as an antisecretory agent similar to ranitidine and lansoprazole (Mahattanadul et al., 2011). In an open-label, two-period crossover study, 20 healthy volunteers from 18 to 45 years old were given a single-dose of Thai M. citrifolia fruit aqueous extract containing 25.15 ± 0.11 μg/ml scopoletin. After 30 min the volunteer were given 1 tablet of ranitidine (300 mg) and blood samples were collected for 12 h. The results showed that M. citrifolia acted as a ranitidine absorbance inducer due to the presence of scopoletin which stimulated the 5-HT4 receptor. Further clinical trial using more patients having specific gastric motility defect or symptoms was recommended to provide stronger evidence (Nima et al., 2012).

4.13 Antiemetic activity

To study the antiemetic activity of M. citrifolia, a preliminary randomized double blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial was done on 100 patients with a high risk of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), their ages were 18–65 years old. In one group Thai M. citrifolia fruit was given 1 h. before the surgery at a dose of 600 mg, beside that the patients were also received the standard general anesthesia as well as the post-operative analgesia. The results revealed that patients who received M. citrifolia experienced significantly less nausea during the first 6 h compared to the placebo group (Prapaitrakool and Itharat, 2010), to understand this activity further in vitro, in vivo and clinical trials should be conducted to specify by which mechanism(s) M. citrifolia is acting as an antiemetic, and what if it could be used in reducing emetic symptoms caused by different cases rather than PONV.

4.14 Gout and hyperuricemia healing activity

The in vitro bioassay of xanthine oxidase (XO) inhibiting effects revealed that the Tahitian noni juice (TNJ) is having a dose dependent natural anti-gout and anti-hyperuricemic effects. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of M. citrifolia was 3.8 mg whereas IC50 of allopurinol was 2.4 μm. The concentrated methanol extract of this fruit juice at concentration of 0.1 mg/ml exhibited higher XO enzyme inhibition rate (64%) compared to XO enzyme inhibition rate of TNJ itself (11%) at concentration of 1 mg/ml. However, the authors recommended further studies to isolate the active compounds, and to conduct clinical trials in an aim of supporting this hypothesis (Palu et al., 2009).

4.15 Anti-psoriasis healing activity

M. citrifolia was reported to act as an anti-psoriasis healing factor in a 31-year old man who received treatment of M. citrifolia fruit powder (4 g/day) and a weekly methotrexate. After one month treatment, his psoriatic skin lesions significantly improved. This could be due to the immune-modulation effect of both M. citrifolia and methotrexate on skin lesion (Okamoto, 2012). So far, this is the only case report about that activity, thus, such cases should be deeply investigated on in vitro, in vivo and clinical scales.

4.16 Immunity enhancing activity

The immunity enhancement activity of both Tahitian and commercial M. citrifolia fruit juices was reported in an in vivo study on mice, suggesting that M. citrifolia is modulating the immune system by activating the CB2 receptors, and suppressing the interleukin-4, as well as increasing the production of interferon gamma cytokines. However, authors recommended further in vivo and clinical research to illustrate the dosage and actual mode of action of M. citrifolia on the immune system (Palu et al., 2008).

4.17 Anti-viral activity

M. citrifolia fruit component damnacanthal showed to have an in vitro anti-viral activity via inhibiting one of the human immunodeficiency viruses type 1 (HIV-1) accessory proteins in a Hela cells through an unknown mechanism. Authors suggested further studies to elucidate the anti-viral mechanism of M. citrifolia that could be useful in assessing the treatment of HIV-1 and other viral diseases (Kamata et al., 2006).

4.18 Anti-parasitic activity

Brazilian M. citrifolia fruit aqueous extract at 50.1 mg/mL and ethanolic extract at 24.6 mg/mL were given for three days to chickens naturally infected by Ascardiagalli. The aqueous extract showed lower parasite mortality rate (27.08%) than ethanol extract (66.67%), and the authors recommended repeating the in vivo experiment using higher concentrations (Brito et al., 2009).

4.19 Anti-tuberculosis activity

The Filipino M. citrifolia leaves ethanol extract and hexane fractions at 100 μg/ml reported to have an anti-tubercular activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis cultures, with inhibition rates of 89% and 95% respectively. It is suggested that the activity may come from E-Phytol compounds, which is a mixture of ketosteroids, and epidioxysterol (Saludes Jonel et al., 2002). Future studies should select a proper positive control to assess this activity.

4.20 Osteoporotic and otoscopic enhancer

Langford et al. (2004) investigated the ability of M. citrifolia fruit juice to enhance osteoporotic conditions and otoscopic deficiencies by conducting a pilot health survey using SF-36 measurements. Eight participants consumed 2 oz of either a placebo or a M. citrifolia juice (US brand), along with calcium supplement, two times a day for 3 months. The results showed an increase in bone reconstruction which is probably due to a slight increase in the mean value of the osteoclastic activity specific marker, the deoxypyridinoline crosslinks. The otoscopic evaluation showed a limited impact on hearing, with a possible prophylactic effect at the 8000 Hz sensorineural domains; however authors recommended further studies with a larger sample size and over longer time periods (Langford et al., 2004).

Table 2 shows the kinds of investigations (in vivo, in vitro and clinical trials) conducted on leaf, fruit seed and root of M. citrifolia.

5 Conclusion

M. citrifolia has been used as a medicine for the overall maintenance of a good health as well as the prevention of some diseases including skin, brain, GIT, heart, liver and cancer. Till date, the only information available for daily recommended oral dose of M. citrifolia is 2 g; however, there is no information on recommended doses range for topical preparations. It is important to understand that M. citrifolia properties require further extensive studies in terms of identification of the active compounds, their specific mechanism of action and safety. In addition, more in vivo and clinical studies are required with a significant number of subjects and a wider range of concentrations especially in the cancer field. Since further studies are recommended on M. citrifolia and its products, thus they should be used with caution particularly for customers with concomitant illness and medications. Companies which are producing M. citrifolia products should provide relevant information regarding the bioactive components of M. citrifolia and any extra nutritional elements added to the products, along with their concentrations in order to arouse a sense of awareness among consumers for the safe purchase.

Acknowledgment

Authors are grateful to Universiti Sains Malaysia for providing a short term grant holding the number 304/P Farmasi/6312023 to accomplish this work.

References

- Melanogenesis-inhibitory saccharide fatty acid esters and other constituents of the fruits of Morinda citrifolia (Noni) Chem. Biodivers.. 2012;9(6):1172-1187.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Micronutrient and phytochemical screening of a commercial Morinda citrifolia juice and a popular blackcurrant fruit juice commonly used by Athletes in Nigeria. World Rural Obser.. 2015;7(1):40-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of coating tablet extract noni fruit (Morinda citrifolia, L.) with maltodextrin as a subcoating material. J. Med. Sci.. 2007;7(5):762-768.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumor cell-selective antiproliferative effect of the extract from Morinda citrifolia fruits. Phytother. Res.. 2006;20(6):515-517.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial substances from flowering plants. 3. Antibacterial activity of dried Australian plants by rapid direct plate test. Aust. J. Exp. Biol.. 1956;34(1):17-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of biomass and useful compounds from adventitious roots of high-value added medicinal plants using bioreactor. Biotechnol. Adv.. 2012;30(6):1255-1267.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anthelmintic activity of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of Morinda citrifolia fruit on ascaridia galli. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet.. 2009;18(4):32-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer activity of Morinda citrifolia (Noni) fruit: a review. Phytother. Res.. 2012;26(10):1427-1440.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The antibacterial properties of some plants found in Hawaii. Pac. Sci.. 1950;4(3):167-183.

- [Google Scholar]

- The noni fruit (Morinda citrifolia L.): a review of agricultural research, nutritional and therapeutic properties. J. Food Compos. Anal.. 2006;19(6-7):645-654.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chunhieng, M.T., 2003. Developpement de nouveaux aliments santé tropical: application a la noix du Bresil Bertholettia excels et au fruit de Cambodge Morinda citrifolia. Ph.D, l’Institut National Polytechnique de Lorraine (INPL).

- Morinda citrifolia (noni) juice augments mammary gland differentiation and reduces mammary tumor growth in mice expressing the unactivated c-erbb2 transgene. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med.. 2012;2012:1-15.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva, Aline Marques, de Souza, Adriana Martins, de Paula Maciel, Fernanda, Diniz, Adriana Pádua, Zan4, Renato André, Ramos, Leandro José, Barbosa, Nathália Vieira, de Oliveira Meneguetti, Dionatas Ulises, 2012. Analysis physical-chemical, mutagenic and antimutagenic of Morinda citrifolia L. (rubiaceae: Rubioideae) noni, germinaded in the region of Brazilian West Amazon. Open Access Scientific Reports 1 (12), pp. 1–6, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4172/scientificreports.569.

- Noni as an anxiolytic and sedative: a mechanism involving its gamma-aminobutyric acidergic effects. Phytomedicine. 2007;14(7–8):517-522.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lipoxygenase inhibitory constituents of the fruits of noni (Morinda citrifolia) collected in Tahiti. J. Nat. Prod.. 2007;70(5):859-862.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A quantitative comparison of phytochemical components in global noni fruits and their commercial products. Food Chem.. 2010;122(1):267-270.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization, anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects of Costa Rican noni juice (Morinda citrifolia l.) J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2011;133(1):108-115.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efsa, European Food Safety Authoritiy, 2009. Scientific opinion of the panel on dietetic products nutrition and allergies on a request from the European commission on the safety of ‘Morinda citrifolia (noni) fruit puree and concentrate’ as a novel food ingredient. The EFSA J. 998:1–16. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2903/j.efsa.2009.998.

- Hawaiian Noni (Morinda citrifolia): Prize Herb of Hawaii and the South Pacific. Utah: Woodland Publishing; 1998.

- Effect of maltodextrins in the water-content–water activity–glass transition relationships of noni (Morinda citrifolia l.) pulp powder. J. Food Eng.. 2011;103(1):47-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Volatile components of ripe fruits of Morinda citrifolia and their effects on Drosophila. Phytochemistry. 1996;41(2):433-438.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Morinda citrifolia (noni) as an anti-infammatory treatment in women with primary dysmenorrhoea: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial treatment in women with primary dysmenorrhoea: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. Int.. 2013;2013:1-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antitumour potential of a polysaccharide-rich substance from the fruit juice of Morinda citrifolia (noni) on sarcoma 180 ascites tumour in mice. Phytother. Res.. 2003;17(10):1158-1164.

- [Google Scholar]

- Induction of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis by Morinda citrifolia (noni) in human cervical cancer cells. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev.. 2013;14(1):237-242.

- [Google Scholar]

- Induction of normal phenotypes in ras-transformed cells by damnacanthal from Morinda citrifolia. Cancer Lett.. 1993;30(73(2–3)):161-166.

- [Google Scholar]

- An immunomodulatory polysaccharide-rich substance from the fruit juice of Morinda citrifolia (noni) with antitumour activity. Phytother. Res.. 1999;13(5):380-387.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti diabetic effect of fruit juice of Morinda citrifolia (Tahitian Noni Juice®) on experimentally induced diabetic rats. Nigerian J. Health Biomed. Sci.. 2008;7(2):34-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of maturity and harvest season on antioxidant activity, phenolic compounds and ascorbic acid of Morinda citrifolia L. (noni) grown in Mexico (with track change) Afr. J. Biotechnol.. 2013;12(29):4630-4639.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anthraquinones in cell suspension cultures of Morinda citrifolia. Phytochemistry. 1981;20(7):1693-1700.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Using quality of life measures in a Phase I clinical trial of noni in patients with advanced cancer to select a Phase II dose. J. Diet. Suppl.. 2009;6(4):347-359.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial, antifungal and tumor cell supression potential of Morinda citrifolia fruit extracts. Int. J. Integr. Biol.. 2008;3(1):44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, C.J., Palu, A.K., Story, S.P., Su, C.X., Wang, M.Y., West, B.J., Westendorf, J.J., 2005. Selectively inhibiting estrogen production and providing estrogenic effects in the human body. Google Patents.

- Studies on physico-chemical properties of noni fruit (Morinda citrifolia) and preparation of noni beverages. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Diet.. 2012;1(102):3-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cell-based chemical genetic screen identifies damnacanthal as an inhibitor of HIV-1 Vpr induced cell death. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.. 2006;348(3):1101-1106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical constituents of Morinda citrifolia fruits inhibit copper-induced low-density lipoprotein oxidation. J. Agric. Food Chem.. 2004;52(19):5843-5848.

- [Google Scholar]

- New anthraquinone glycosides from the roots of Morinda citrifolia. Fitoterapia. 2009;80(3):196-199.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory effect of anthraquinones isolated from the Noni (Morinda citrifolia) root on animal A-, B- and Y-families of DNA polymerases and human cancer cell proliferation. Food Chem.. 2010;118(3):725-730.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of larvicidal and pupicidal activity of Morinda citrifolia L. (Noni) (Family: Rubiaceae) against three mosquito vectors. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis.. 2012;2(Suppl. 1):S362-S369.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mosquitocidal properties of Morinda citrifolia l. (Noni) (family: Rubiaceae) leaf extract and Metarhizium anisopliae against malaria vector, Anopheles stephensi Liston. (Diptera: Culicidae) Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis.. 2014;4(1):S173-S180.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnaiah, Duduku, Nithyanandam, Rajesh, Sarbatly, Rosalam, 2012. Phytochemical constituents and activities of Morinda citrifolia L. In: Venketeshwer (Ed.), Phytochemicals – A Global Perspective of Their Role in Nutrition and Health. InTech.

- Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of an isolated Morinda citrifolia l. methanolic extract from poly-ethersulphone (pes) membrane separator. J. King Saud University – Eng. Sci.. 2015;27(1):63-67.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Morinda citrifolia on quality of life and auditory function in postmenopausal women. J. Altern. Complement. Med.. 2004;10(5):737-739.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional and phenolic composition of Morinda citrifolia L. (Noni) fruit at different ripeness stages and seasonal patterns harvested in Nayarit, Mexico. Int. J. Nutr. Food Sci.. 2014;3(5):421-429.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fermented Noni exudate (fNE): a mediator between immune system and anti-tumor activity. Oncol. Rep.. 2008;20(6):1505-1509.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protection of apoptosis of osteoblast cultured in vitro by Morinda Root Polysaccharide. Zhongguo Gu Shang. 2008;21(1):39-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Beneficial effects of noni (Morinda citrifolia L.) juice on livers of high-fat dietary hamsters. Food Chem.. 2013;140(1–2):31-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Two novel glycosides from the fruits of Morinda citrifolia (noni) inhibit AP-1 transactivation and cell transformation in the mouse epidermal JB6 cell line. Cancer Res.. 2001;61(15):5749-5756.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of the in vitro inhibition of mammary adenocarcinoma cell adhesion by sulphated polysaccharides. Anticancer Res.. 2000;20(5A):3265-3271.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemical components of the roots of noni (Morinda citrifolia) and their cytotoxic effects. Fitoterapia. 2011;82(4):704-708.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morinda citrifolia linn; a medicinal plant with diverse phytochemicals and its medicinal relevance. World J. Pharm. Res.. 2013;3(1):215-232.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Morinda citrifolia aqueous fruit extract and its biomarker scopoletin on reflux esophagitis and gastric ulcer in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2011;134(2):243-250.

- [Google Scholar]

- Studies on antidyslipidemic effects of Morinda citrifolia (Noni) fruit, leaves and root extracts. Lipid. Health Dis.. 2010;9(88):1-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory effects of constituents of Morinda citrifolia seeds on elastase and tyrosinase. J. Nat. Med.. 2009;63(3):267-273.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory effects of Morinda citrifolia extract and its constituents on melanogenesis in murine B16 melanoma cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull.. 2012;35(1):78-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of Morinda citrifolia extract and its constituents on blood fluidity. J. Tradit. Med.. 2011;28(2):47-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, Hideaki, Masuda, Megumi, Murata, Kazuya, Abe, Yumi, Uwaya, Akemi, 2013. Study of the anti-photoaging effect of noni (Morinda citrifolia), Melanoma – From Early Detection to Treatment.

- Isolation and identification of antioxidative compound from fruit of Mengkudu (Morinda citrifolia L.) Int. J. Food Prop.. 2007;10(2):363-373.

- [Google Scholar]

- The ocean-going noni, or Indian Mulberry (Morinda citrifolia, Rubiaceae) and some of its “colorful” relatives. Econ. Bot.. 1992;46(3):241-256.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of Morinda citrifolia as an endodontic irrigant. J. Endod.. 2008;34(1):66-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review of Malaysian medicinal plants with potential antidiabetic activity. J. Pharm. Res.. 2011;4(11):4217-4224.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morinda citrifolia fruit reduces stress-induced impairment of cognitive function accompanied by vasculature improvement in mice. Physiol. Behav.. 2010;101(2):211-217.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extraction and preliminary phytochemical screening of active compounds in Morinda citrifolia fruit. Asian J. Pharm. Clin. Res.. 2012;5(2):179-181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutraceutical properties of Thai “Yor”, Morinda citrifolia and “Noni” juice extract. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol.. 2005;27(2):579-586.

- [Google Scholar]

- Noni puree (Morinda citrifolia) mixed in beef patties enhanced color stability. Meat Sci.. 2012;91(2):131-136.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, Scot C., 2006. Species profiles for Pacific island agroforestry Morinda citrifolia noni. In: Elevitch, Craig R. (Ed.). Permanent Agriculture Resources <http://www.traditionaltree.org/>.

- Prevention of palmitic acid-induced lipotoxicity by Morinda citrifolia (noni) FASEB J.. 2008;22(1_MeetingAbstracts):1062-1064.

- [Google Scholar]

- Regulation of glucose metabolism via hepatic forkhead transcription factor 1 (FoxO1) by Morinda citrifolia (Noni) in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Br. J. Nutr.. 2012;108(2):218-228.

- [Google Scholar]

- Newton, Ken, 2002. Production of noni juice and powder in Samoa. In: Hawai‘i Noni Conference, University of Hawaii at Manoa, College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources.

- Gastrokinetic activity of Morinda citrifolia aqueous fruit extract and its possible mechanism of action in human and rat models. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2012;142(2):354-361.

- [Google Scholar]

- Damnacanthal, a noni component, exhibits antitumorigenic activity in human colorectal cancer cells. J. Nutr. Biochem.. 2012;23(8):915-923.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Morinda citrifolia (Noni) in the Treatment of Psoriasis. Open General Int. Med. J.. 2012;5:1-2.

- [Google Scholar]

- Protective effect of fruits of Morinda citrifolia L. on scopolamine induced memory impairment in mice: a behavioral, biochemical and cerebral blood flow study. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2012;139(1):34-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitory effect of Morinda citrifolia L. on lipoprotein lipase activity. J. Food Sci.. 2008;73(8):C595-C598.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effects of Morinda citrifolia l. (noni) on the immune system: Its molecular mechanisms of action. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2008;115(3):502-506.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthine oxidase inhibiting effects of noni (Morinda citrifolia) fruit juice. Phytother. Res.. 2009;23(12):1790-1791.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wound healing effects of noni (Morinda citrifolia L.) leaves: a mechanism involving its PDGF/A2A receptor ligand binding and promotion of wound closure. Phytother. Res.. 2010;24(10):1437-1441.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Noni-based nutritional supplementation and exercise interventions influence body composition. N. Am. J. Med. Sci.. 2011;3(12):552-556.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Noni seed oil topical safety, efficacy, and potential mechanisms of action. J. Cosmet., Dermatol. Sci. Appl.. 2012;2(2):74-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antipsychotic-like activity of noni (Morinda citrifolia Linn.) in mice. BMC Complement. Altern. Med.. 2012;12 186

- [Google Scholar]

- Review of the ethnobotany, chemistry, biological activity and safety of the botanical dietary supplement Morinda citrifolia (noni) J. Pharm. Pharmacol.. 2007;59(12):1587-1609.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington, Karen, The CAM-Cancer Consortium, 2015. Noni (Morinda citrifolia), abstract and key points. European Commission.

- Morinda citrifolia (noni) fruit–phytochemistry, pharmacology, safety. Planta Med.. 2007;73(3):191-199.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Morinda citrifolia Linn. For prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting. J. Med. Assoc. Thai.. 2010;93(Suppl. 7):S204-S209.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preclinical evaluation of antidiabetic activity of noni fruit juice. Int. J. Bioassays. 2013;02(02):475-482.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bio-extract concentrated of Thai “Yore” Morinda citrifolia effects in analgesic, acute toxicity and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Thammasat Med. J.. 2011;11(1):8-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of chromatography and mass spectrometry to the characterization of cobalt, copper, manganese and molybdenum in Morinda citrifolia. J. Chromatogr. A. 2013;15(1281):19-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of Morinda citrifolia juice as an endodontic irrigant on smear layer and microhardness of root canal dentin. Oral Sci. Int.. 2013;10(2):53-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Saidan, Noor Hafizoh, 2009. Phytochemicals and biological activities of roots of malaysian Morinda citrifolia (rubiaceae). Master, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Universiti Teknologi MARA.

- Antitubercular constituents from the hexane fraction of Morinda citrifolia Linn. (Rubiaceae) Phytother. Res.. 2002;16(7):683-685.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review on anticancer potential and other health beneficial pharmacological activities of novel medicinal plant Morinda citrifolia (Noni) Int. J. Pharmacol.. 2014;9(8):462-492.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sang, Shengmin, Wang, Mingfu, He, Kan, Liu, Guangming, Dong, Zigang, Badmaev, Vladimir, Zheng, Qun, Yi, Ghai, Geetha, Rosen Robert T., Ho, Chi-Tang., 2001. Chemical components in Noni fruits and leaves (Morinda citrifolia l.). In: Quality Management of Nutraceuticals, pp. 134–150. American Chemical Society.

- Ashyuka: a hub of medicinal values. Int. J. Biol. Pharm. Res.. 2013;4(12):1043-1049.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-arthritic activity of Morinda citrifolia L. fruit juice in Complete Freund’s adjuvant induced arthritic rats. J. Pharm. Res.. 2012;5(2):1236-1239.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutritional composition and identification of some of the bioactive components in Morinda citrifolia juice. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci.. 2011;3(1):58-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Serafini, Mairim Russo, Santos, Rodrigo Correia, Guimaraes, Adriana Gibara, dos Santos, Joao Paulo Almeida, da Conceicao Santos, Alan Diego, Alves, Izabel Almeida, Gelain, Daniel Pens, de Lima Nogueira, Paulo Cesar, Quintans-Júnior, Lucindo Jose, de Souza Araujo, Adriano Antunes, Bonjardim, Leonardo Rigoldi, 2011. Morinda citrifolia linn leaf extract possesses antioxidant activities and reduces nociceptive behavior and leukocyte migration. J. Med. Food 14 (10):1159–1166.

- Hypoglycemic and hepatoprotective activity of fermented fruit juice of Morinda citrifolia (Noni) in diabetic rats. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med.. 2011;2011:1-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Food sources of provitamin A and vitamin C in the American Pacific. Trop. Sci.. 2001;41:199-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Morinda citrifolia L. (Noni): a review of the scientific validation for its nutritional and therapeutic properties. J. Diabet. Endocrinol.. 2012;3(6):77-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Noni Phenomenon (second ed.). Utah: Direct Source Publishing; 1999.

- Multiple berry types prevent n-nitrosomethylbenzylamine-induced esophageal cancer in rats. Pharm. Res.. 2010;27(6):1138-1145.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Su, C., Wang, M.Y., Nowicki, D., Jensen, J., Anderson, G., 2001. Selective cox-2 inhibition of Morinda citrifolia (Noni) in vitro. In: The Proceedings of the Eicosanoids and Other Bioactive Lipids in Cancer. Inflammation and Related Disease. The 7th Annual Conference, Loews Vanderbilt Plaza, Nashville, Tennessee, USA.

- Chemical constituents of the fruits of Morinda citrifolia (Noni) and their antioxidant activity. J. Nat. Prod.. 2005;68(4):592-595.

- [Google Scholar]