Translate this page into:

Multidisciplinary green approaches (ultrasonic, co-precipitation, hydrothermal, and microwave) for fabrication and characterization of Erbium-promoted Ni-Al2O3 catalyst for CO2 methanation

⁎Corresponding author. salavati@kashanu.ac.ir (Masoud Salavati-Niasari)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The dispersion of nickel catalysts is crucial for the catalytic ability of CO2 methanation, which can be influenced by the fabrication method and the operation process of the catalysts. Therefore, a series of fabrication methods, including ultrasonic, hydrothermal, microwave, and co-precipitation, have been applied to prepare 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalysts. The fabrication method can partially influence the structural and catalytic activity of the nickel aluminate catalysts. Among the catalysts modified by Erbium prepared with various methods, the catalyst fabricated by ultrasonic pathway exhibited better catalytic performance and CH4 selectivity especially, at a temperature (400 ℃). The impact of the temperature of the reaction (200–500 °C) was examined under a stoichiometric precursor ratio of (H2:CO2) = 4: 1, atmospheric pressure, and space velocity (GHSV) of 25000 mL/gcath. The results demonstrate that the ultrasonic method is strongly efficient for fabricating Ni-based catalysts with a high BET surface area of about 190.33 m2g−1. The catalyst composed via the ultrasonic technique has 69.38 % carbon dioxide conversion and 100 % methane selectivity at 400 °C for excellent catalytic performance in CO2 methanation reactions. The fabrication effect can be associated with its high surface area, which is achieved via the hot spot mechanism. Besides, the addition of Erbium promotes the Ni dispersion on the supports and stimulates the positive reaction because of the erbium oxygen vacancies.

Keywords

CO2 Methanation

Hydrothermal

CH4 Selectivity

Ultrasonic Method

Erbium-Promoted Ni Catalysts Nanostructures

1 Introduction

Anthropogenic actions constantly boost atmospheric CO2 levels, being accountable for climate change effects and global warming (Cox et al., 2000; Gruber et al., 2019; Kind, 2009; Zhu et al., 2021). Existent technologies can efficiently captivate carbon dioxide from the source of the manufacturing site, although the consequent disposal remains a challenge. Amidst every possible solution, catalytic reduction of CO2 into value-added goods, identified as “CO2 utilization”, is a hopeful approach because it not only can decrease the pure carbon effusion but also generate commodity chemicals and fuels, which are of great manufacturing quality (Gao et al., 2019; Peng et al., 2018; Tackett et al., 2019). In addition, such technology could likewise be beneficial for recycling oxygen atoms in closed ecological systems, including crewed spacecraft and submarines (Wendel et al., 2005).

A comprehensive variety of goods can be achieved through the catalytic reduction of CO2, such as alcohols, carbon monoxide, alkanes, esters, alkenes, aromatic compounds, etc. (Asefa et al., 2019; Saeidi et al., 2014). Amidst them, methane (CH4) is attractive as an ideal energy carrier that can be distributed through the regular gas pipeline system. In addition, the molecular hydrogen (H2) required for this reaction can be produced by electrolysis of water using renewable power (biomass, wind, solar, etc.) as a power input. Many aspects of CO2 methanation have been studied over the last few decades, for instance, catalytic structures, mechanisms, etc. (Frontera et al., 2017; Saeidi et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2020).

Based on the report, methanation of CO2 (Eq. 1), which is a highly exothermic reaction (ΔH298K = -165 kJmol−1), occurs through the CO intermediate generation by the reverse water–gas shift (RWGS) reaction (Eq. (2)), pursued via hydrogenation of CO to methane (Eq. (3)) (Bin et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2021; Hu, et al., 2022a; Hu, et al., 2022b). 4H2 (g) + CO2 (g) → CH4 (g) + 2 H2O (g) ΔΗ298 Κ = − 165 kJ mol−1(1) CO2 (g) + H2 (g) ↔ H2O (g) + CO (g) ΔΗ298 Κ = +41 kJ mol−1(2) 3H2 (g) + CO (g) ↔ CH4 (g) + H2O (g) ΔΗ298 Κ = -206 kJ mol−1(3)

Nevertheless, through the hydrogenation procedure of CO2 and relying on the catalyst system and reaction state applied, some of the generated carbon monoxides are not able to cooperate in the methanation and produce methane, which reduces the methane selectivity (Panagiotopoulou, 2017). Therefore, the development of highly active catalytic systems capable of effectively converting carbon dioxide to methane at suitable temperatures with high carbon resistance and low CO generation are an urgent need. Up to now, comprehensive investigations have been performed to assess and analyze the selectivity and activity of multiple metals (such as Ni, Co, Ru, and Rh) on many oxide supports (for example, CeO2, SiO2, TiO2, MgO, La2O3, Y2O3, Nb2O5, Al2O3, and ZrO2) for low-temperature purposes (Alarcón et al., 2019; Gnanakumar et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2014; Li et al., 1998; Yan et al., 2018).

Catalysts based on nickel endure deactivation at low temperatures owing to the generation of the nickel carbonyl, which is obtained from the interplay of CO with metal species. This nickel carbonyl formation can stimulate the sintering of metal (Daza et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2018a; Zhan et al., 2018). The support type utilized to prepare the catalysts is a fundamental parameter in preventing catalyst deactivation. The catalytic behavior and also the basic and acidic features can be affected by the catalyst support type (Le et al., 2017). The interplay between support and metal has a notable impact on catalytic behavior, and it is generally called the “metal-support interaction.” The support plays an essential role in the catalytic performance and stability and, likewise, on the production of inactive spinel phases and the distribution of the active metal (Jimenez et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016).

The synthesis procedure can influence the textural properties of the methanation catalysts. Different synthesis approaches, for example, ultrasonic (U), co-precipitation (C), sol–gel, impregnation, and solid-state, have been employed for the nanocatalyst preparation (Salavati-Niasari et al., 2008). Based on the researches, the incorporation of rare earth elements into the Al2O3 lattice develops its thermal resistance and may generate further oxygen vacancies. The oxygen vacancies are extremely helpful in limiting the aggregation of metal particles (for example, Ni) (Siakavelas et al., 2021a). In particular, the formation of solid solutions with trivalent rare-earth metal cations generates a non-stoichiometry of oxygen, which intensifies the movement of O-2 ions (Luisetto et al., 2019). In this regard, different fabrication methods, including ultrasonic (U), hydrothermal, microwave (M), co-precipitation (C), were applied to prepare 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalysts. The ultrasonic method has been widely utilized to accelerate the synthesis of materials (decreasing the reaction time from hours to a few minutes) compared to conventional hydro/solvothermal techniques, and its benefits have been investigated in several practical studies. (Daroughegi et al., 2020; Salavati-Niasari, 2005; Salavati-Niasari, 2006). As is known, this is the first time that Er-promoted alumina has been applied as a support for nickel-based catalysts in the CO2 methanation reactions. Therefore, in the current research, we fabricated a nickel-based catalyst on Al2O3 support, promoted by Er elements with different preparation methods for the first time, demonstrating an excellent catalytic performance and selectivity of methane with superior durability at a lower temperature of the reaction.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Precursors

Erbium(III) nitrate pentahydrate (Er(NO3)3·5H2O), Nickel(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Ni(NO3)2·6H2O), Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), Aluminum nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO3)3·9H2O), ethyl alcohol, Ethylene glycol (EG) were procured from Sigma-Aldrich and employed without extra refinement.

2.2 Preparation of catalyst

2.2.1 Synthesis of Ni/Al2O3

25Ni/Al2O3 was prepared from aluminum nitrate nonahydrate and nickel(II) nitrate hexahydrate by sonochemical method. In short, 5.15 g of Al(NO3)3·9H2O was liquified in 25 mL of distilled water (DW). 1.23 g Ni(NO3)2·6H2O was liquefied in 20 mL DW and added to Al(NO3)3·9H2O solution. Under ultrasonic radiation (QSONICA-Q700 Sonicator), an aqueous NaOH (1 M) solution was added to the above solution as a precipitant to adjust the pH at 10. The precipitate was washed with DW and ethyl alcohol multiple times and parched at 75 ℃ for 12 h. Eventually, the powder was calcinated at 700 °C for 4 h at a temperature increase rate of 3 ℃/min (Chang et al., 2021).

2.2.2 Ultrasonic preparation of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3

In a conventional approach, 5.15 g of Al(NO3)3·9H2O was dissolved in 25 mL of DW (solution A). In the next step, 1.23 g Ni(NO3)2·6H2O was dissolved in 20 mL DW and agitated for 15 min. 0.11 g Er(NO3)3·5H2O was also dissolved in 15 mL DW. The solution containing Er was added to the solution A and stirred for 15 min. Then, the solution of Ni ions was added and agitated for another 30 min (solution B). An aqueous NaOH (1 M) solution was added to solution B under ultrasonic radiation (15 min 30 W) as a precipitant to adjust the pH of the solution at 10. The obtained precipitate was rinsed with DW and ethyl alcohol many times and parched at 75 ℃ for 12 h. Eventually, the powder was calcined at 700 °C for 4 h at a temperature increase rate of 3 ℃/min.

2.2.3 Hydrothermal preparation of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3

All steps until reaching solution B were similar to the ultrasonic method. An aqueous NaOH (1 M) solution was then added to the mixture as a precipitant to adapt the pH of the solution to 10. The obtained mixture was moved to a Teflon reactor and transferred to an oven at 180 ℃ for 12 h. The collected precipitate was rinsed with DW and ethyl alcohol many times and parched at 75 ℃ for 12 h. Finally, the powder was calcined at 700 °C for 4 h at a temperature increase of 3 ℃/min.

2.2.4 Microwave preparation of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3

All steps until reaching solution B were similar to the above procedure. The solvent of all precursors was ethylene glycol. The mixture was placed under microwave irradiation at 900 W for 5 min after adjusting the pH to 10. The resulted powder was centrifuged with ethanol and DW three times and dried at 75 ℃ for 12 h. Finally, the powder was calcined at 700 °C for 4 h at a temperature increase rate of 3 ℃/min.

2.2.5 Co-precipitation preparation of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3

5.15 g of Al(NO3)3·9H2O was dissolved in 30 mL DW (solution A). In the next step, 1.23 g Ni(NO3)2·6H2O was dissolved in 20 mL DW and stirred for 15 min. 0.11 g Er(NO3)3·5H2O was also dissolved in 15 mL DW. The solution containing Er was added to the solution A and stirred for 15 min. Then, the solution of Ni ions was added and agitated for another 30 min (solution B). An aqueous NaOH (1 M) solution was then added to the mixture as a precipitant to adjust the pH of the solution at 10. The obtained precipitate was washed with DW and ethanol many times and dried at 75 ℃ for 12 h. Finally, the powder was calcined at 700 °C for 4 h at a temperature increase rate of 3 ℃/min.

2.3 Catalytic hydrogenation of CO2

A quartz tubular fixed-bed reactor (10 mm in diameter) was used for the catalytic evaluation of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalysts for CO2 methanation at atmospheric pressure. The catalyst powder was pressed into tablets and then ground into 0.25–0.5 mm particles before the reaction. The catalyst test used a 100 mg catalyst (60–100 mesh) diluted with 100 mg of inert SiO2. The temperature of the reaction was estimated by a temperature-measuring device positioned in the middle of the catalyst bed. The catalyst was stimulated at 700 °C for 1 h in a stream of pure hydrogen (25 mLmin−1) before testing the catalytic activity. Then the temperature dropped to 200 ℃. CO2 and H2 interacted with the molar ratio of CO2: H2 = 1: 4 at a gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) of 25000 mL/gcath. Specifically, the catalytic behavior was investigated at 200–500 °C (Shafiee et al., 2021). The generated gas flow was measured online by gas chromatography (GC, Shimadzu).

2.4 Physical instruments

The Philips X' Pert Pro X-ray diffractometer with Cu Ka radiation (λ = 0.154 nm) was utilized to register XRD patterns. X’Pert HighScore Plus software was involved in identifying the crystallographic phase of compounds. The texture characteristics of the catalysts were accomplished by degassing at 250 °C for 2 h and then applying N2 adsorption/desorption to the Micromeritics Tristar II 3020 analyzer at −196 °C. The morphology of the catalyst was apperceived with a Vega Tescan microscope operating at 10 kV. Before taking images, the powder sample was uniformly spread on the SEM stubs. Eventually, the specimen was covered with a gold layer. The nitrogen adsorption/resorption was employed as a calculation technique to evaluate the specific surface area, while BJH technique was used to estimate the pore volume and radius. Thermogravimetry/Differential Thermal Analysis (TG/DTA) was conducted on a Bahr STA 503 device by heating the catalysts from 25 to 800 °C at a speed of 10 °C/min below air current. The reduction performance of the catalysts was studied via temperature-programmed reduction (TPR) analysis utilizing a Micromeritics chemisorb 2750 analyzer equipped with a thermal conductivity detector (TCD). 100 mg of each catalyst was preprocessed underneath a stream of Argon at 250 °C for 1 h. It was then heated from 35 °C to 900 °C at a 15 °C/min with 10 % Hydrogen/Argon (30 mLmin−1). The composition of the product was determined using a Shimadzu gas chromatograph containing a Carboxen-1000 column.

3 Results and discussions

3.1 Catalyst description

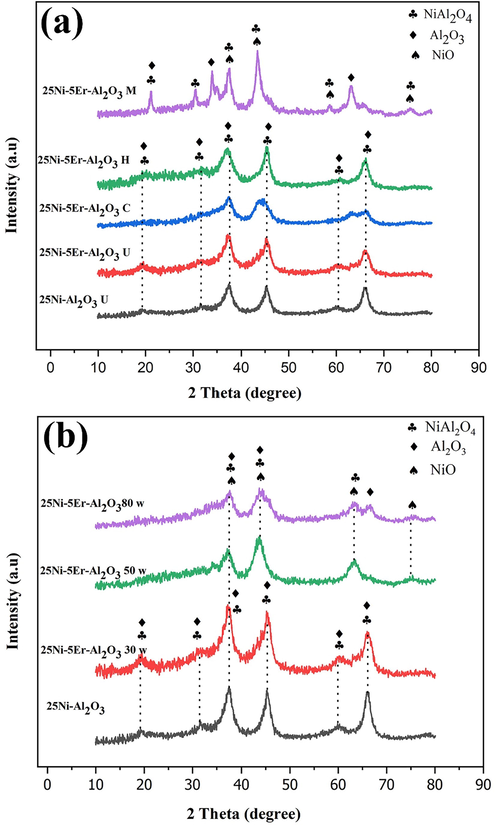

Fig. 1a depicts the XRD patterns of unmodified and modified alumina-supported Ni catalysts prepared with different fabrication methods. Two major crystallographic phases corresponding to the Al2O3 and NiAl2O4 phases are identified in all catalysts. The XRD pattern of the unpromoted Ni-Al2O3 catalyst is formed from NiAl2O4 (JCPDS NO. 10‐0339) and Al2O3 (JCPDS NO. 80–0955) phases. As can be seen, no diffraction peaks related to Er phase were detected for Er-promoted catalysts owing to the small crystal formation with great distribution or low crystallinity. Besides, since the nickel oxide particles are highly dispersed in these samples, they were not identified in the XRD patterns. NiO (JCPDS NO. 047–1049) phase exists in these patterns, which is attributed to the fact that the NiO crystals actively cooperate with the catalyst carrier, causing the high distribution of NiO (Liu et al., 2018c). Fig. 1b depicts the effect of sonication powers (30, 50, and 80 W) on the structure of the catalyst. As observed, the peak intensity and crystallinity of the product have decreased by increasing the sonication power due to the increment in the reaction temperature. According to the XRD data, the 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst prepared in low power (30 W) has better crystallinity than others. The crystal size (D) of the catalysts was specified by the Scherrer (Eq. (4)) (Abkar et al., 2021; Anand et al., 2011) and Williamson Hall (W-H) equations (Eq. (5)) (Pourshirband & Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, 2021, 2022)

The XRD patterns of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 (a) with different fabrication method (M = microwave, H = hydrothermal, C = co-precipitation, and U = ultrasonic) and (b) in three different sonication powers (30, 50 and 80 W).

Here, β is the full width at half maximum (FWHM), θ is the diffraction angle, and λ is the wavelength of the X-ray, K is the Scherrer constant (Anand et al., 2009, 2010) and ɛ is the strain. The calculated crystallite sizes are listed in Tables 1 and 2. As observed, the Scherer equation gives a smaller crystallite size than the Williamson-Hall plot for non-zero residual stress (stress leads to an increase in peak width; therefore, only using the Scherer equation that relies on a very large FWHM and large peak width. Therefore, we have too small crystallite size.

Catalyst

SBET (m2 g−1)

Vpore (cm3 g−1)

dpore (nm)

Crystallite size (nm)*

Crystallite size

(nm)**

H2 consumption (mmol g−1)

25Ni-Al2O3

73.62

0.34

18.65

19.21

23.37

7.41

25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U

190.33

0.39

8.33

8.69

21.76

8.64

25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 C

61.20

0.29

19.35

7.44

12.13

6.78

25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 H

143.01

0.42

11.94

6.76

14.52

5.18

25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 M

38.33

0.17

18.09

25.02

26.77

6.52

Catalyst

SBET (m2 g−1)

Vpore (cm3 g−1)

dpore (nm)

Crystal size (nm)*

Crystal size (nm)**

H2 consumption (mmol g−1)

25Ni-Al2O3

73.62

0.34

18.65

19.21

23.37

7.41

25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 30 w

190.33

0.39

8.33

8.69

21.76

8.64

25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 50 w

160.33

0.26

7.22

5.18

10.59

7.40

25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 80 w

135.64

0.22

7.24

5.91

6.77

6.23

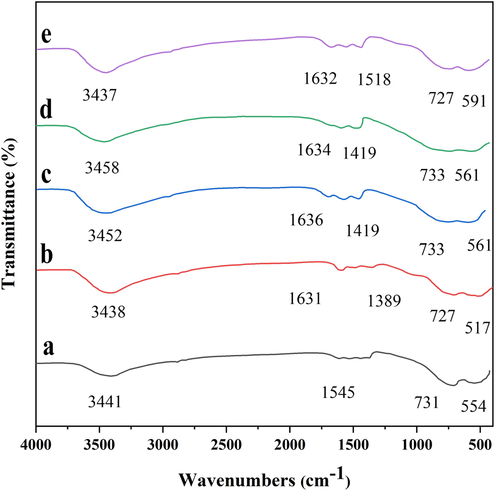

Fig. 2 shows the FTIR spectra of 25Ni-Al2O3 (support sample) and 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 prepared by different fabrication methods. The characteristic bands at 3438–3441 cm−1 are associated with the OH stretching vibrations. In addition, the peaks at around 1630 cm−1 are correlated to H2O bending vibrations in molecules (Padmaja et al., 2001; Salavati-Niasari, 2009). The characteristic bands in the range of 500–750 cm−1 are correlated to the Al—O and Ni—O stretching vibrations (Adamczyk & Długoń, 2012). The addition of Er as a promoter did not change the FTIR spectrum of the catalysts, and it slightly shifted the positions of bands. In addition, the FTIR spectra of different fabrication methods are similar, and the spectra did not change through the prepration process.

FTIR spectra of (a) 25Ni-Al2O3, and 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst prepared by different fabrication methods: (b) ultrasonic, (c) co-precipitation, (d) hydrothermal, and microwave (e).

3.2 BET data

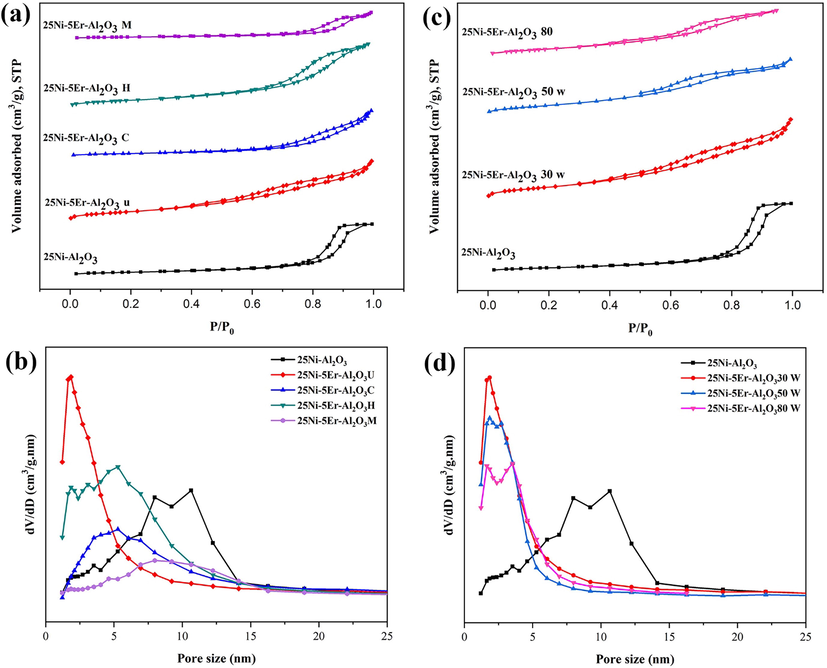

The N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms and pore size distribution diagram of the unmodified Ni-Al2O3 catalyst and modified with Er are demonstrated in Fig. 3. According to the IUPAC categorization, catalytic isotherms belong to Type-IV with H2-type hysteresis loops, indicating that a closely cylindrical mesostructure material containing ink bottle-shaped pores was produced (Dutta et al., 2012). The varieties of pores can be classified into intra-particle pores (within crystals) and inter-particle pores (between crystals). The source of porosity can be both intra- and inter-particle pores of the produced catalyst. Tables 1 and 2 show the sample texture properties. It is worth mentioning that the structural and textural properties of the catalysts are highly influenced by the processing factors. As observed, the type of hysteresis does not alter when the second metal (Er) is introduced into the catalyst (Fig. 3a). Also, changing the fabrication methods does not change the hysteresis type. A broad pore size distribution is observed in the range of 1–15 nm for unmodified catalysts (Fig. 3b).

N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms and pore size distributions of the of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalysts with different fabrication method (M = microwave, H = hydrothermal, C = co-precipitation, and U = ultrasonic) (a,b), and in three different sonication powers (30, 50, and 80 W) (c,d).

The BET surface area was increased (Table 1) after introducing Er as a promotor, which decreased the breadth of the hysteresis loop (Bayat et al., 2016). The pore size distribution of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U shows a mesoporous structure, containing a smaller size distribution (<5 nm) than the 25Ni-Al2O3 catalyst. The pore size distribution curves are shifted to the smaller sizes when the ultrasonic method is used to prepare the 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst. The physical attributes of 25Ni-Al2O3 and 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 prepared by various methods are presented in Tables 1 and 2. The ultrasonic method intensified the total pore volume (from 0.34 to 0.39 cm3g−1) and reduced the mean pore radius (from 18.65 to 8.33 nm) relative to 25Ni-Al2O3. The BET surface area of the 25Ni-Al2O3 was 73.62 m2g−1, and the addition of Er improved the BETsurface area to 190.33 m2g−1 for 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U. The results confirm that the catalyst fabricated by ultrasonic (25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U) has a larger SBET than others. The addition of Er prepared by co-precipitation and microwave methods decreased the SBET area to 61.20 and 38.33 m2g−1 for 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 C and 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 M, respectively. Moreover, the 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 C revealed the highest mean pore diameter (19.35 nm) in comparison to other fabricated catalysts. Therefore, 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U prepared at low sonication power (30 W) possesses the largest surface area and smallest mean pore diameter.

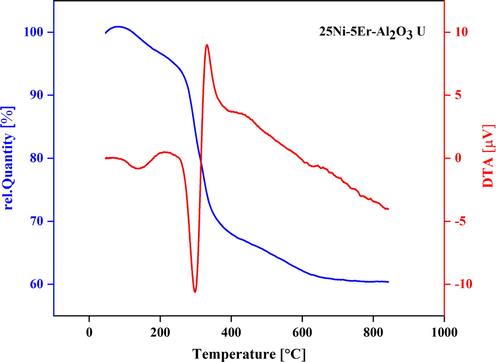

3.3 DTA-TGA analysis

The TGA and DTA analyses were performed (Fig. 4) to investigate the decomposition/mass loss process and the thermal behavior of the 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 (optimal sample) with the maximum surface area. The TGA profile showed three levels of weight loss. The first showed a slight mass loss (about 3.53 wt%) at temperatures below 250 °C, which is due to the dehydration of hygroscopic water or loss of free water evaporation (such as physical adsorption) by an endothermic reaction (Liu et al., 2018b). In the next level, a significant 29.37 % weight loss at about 400 °C was due to the thermal decomposition of metal hydroxides (NiCO3, Al(OH)3, Er(OH)3, and NH4NO3) into oxides (NiO and CO2, Al2O3 and H2O, Er2O3 and H2O, NH3 and NO2) (Rafique et al., 2018). At the high-temperature stage of 600–900 °C, there was nearly no weight loss. The TGA data prove the production of high quantities of carbon deposited on the catalyst. The DTA curve displays an endothermic peak associated with the dehydration of adsorbed water at about 300 °C and an exothermic peak at 335 °C for the catalyst.

TGA spectrum of of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst prepared by ultrasonic method.

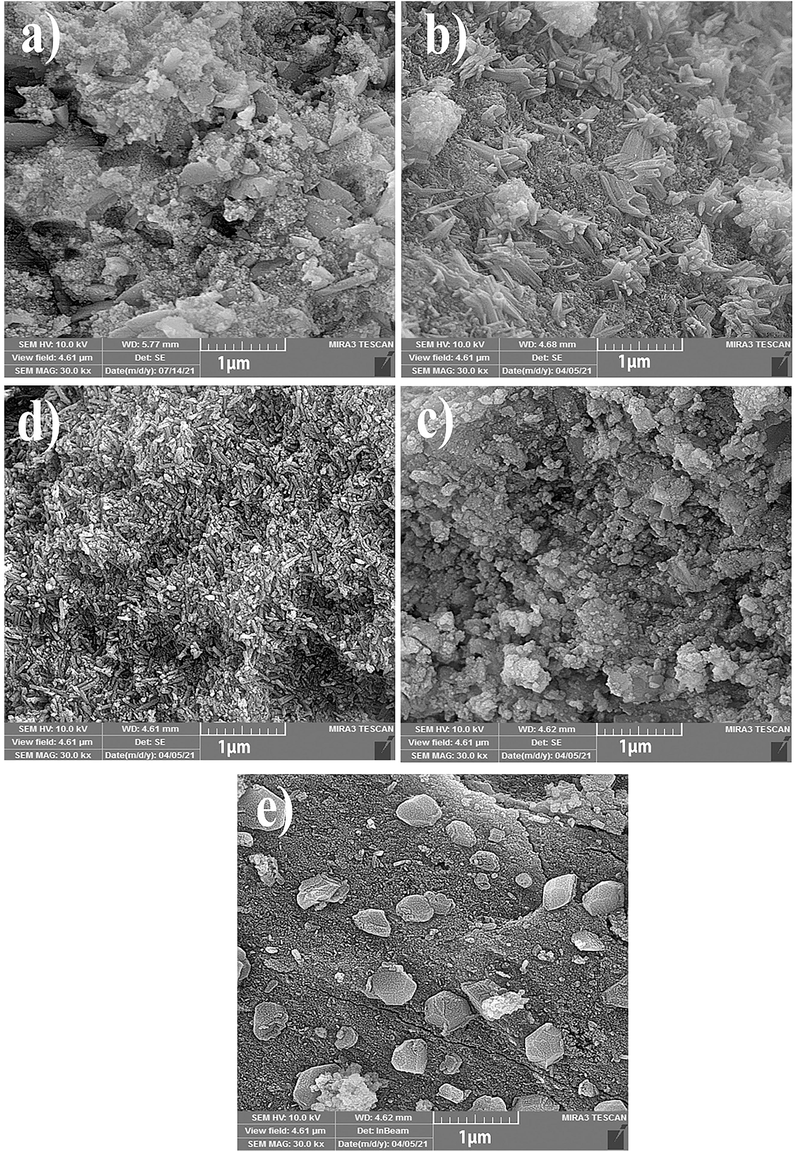

3.4 Morpholophy of catalysts

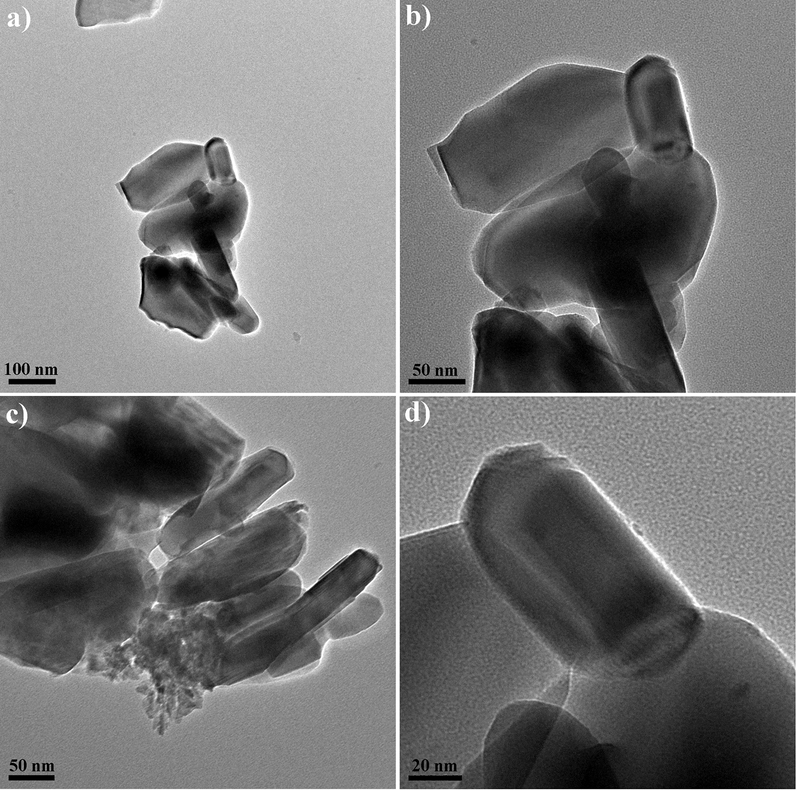

Fig. 5 depicts the FESEM images of Ni-Al2O3 and the Er-modified Ni-Al2O3 catalysts prepared with various fabrication methods. Since the control of particle size and morphology is easier in the hydrothermal method, the catalysts made in this way have a smaller and more uniform particle size than the others. On the other hand, the catalyst prepared by the microwave method has large particles and microstructures. Besides, the tiny Ni species particles dispersed on the surface of 25Ni-Al2O3 and 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U. Fig. 6 reveals the HRTEM micrographs of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U in multiple scales (100, 50, and 20 nm). The morphology of the HRTEM confirms the FESEM image of Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U. As observed, small particles are formed next to the larger particles.

The FESEM micrographs of (a) 25Ni-Al2O3 catalyst, 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst with different fabrication method ((b) ultrasonic, (c) co-precipitation, (d) hydrothermal, and microwave (e)).

The HRTEM micrographs of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst prepared by ultrasonic method.

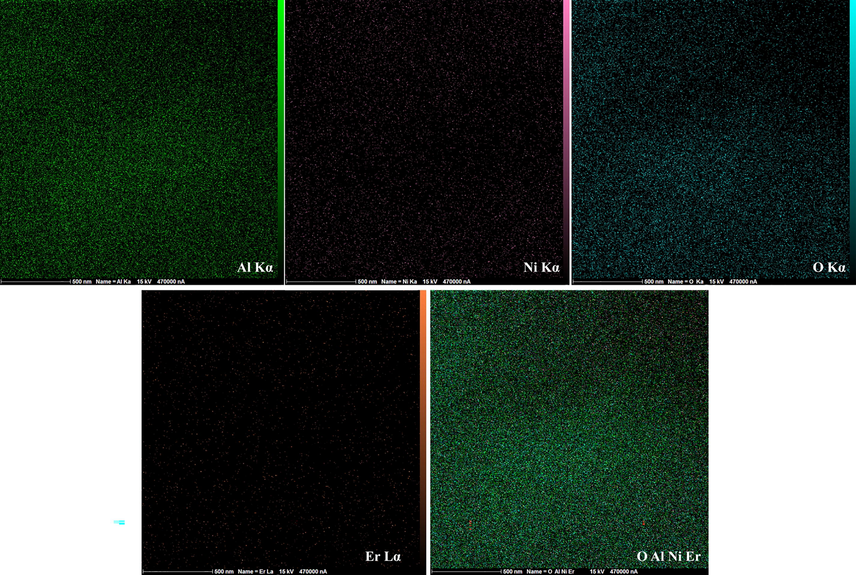

EDS mapping images of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst are displayed in Fig. 7. Multi-elemental EDS mapping images of Al, O, Ni, and Er are depicted in this figure. The corresponding maps of Ni, O, Er, and Al manifested shiny spots corresponding to the areas of calcification and demonstrated a uniform distribution of these elements.

EDS mapping of Al, Ni, O, and Er elements of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst.

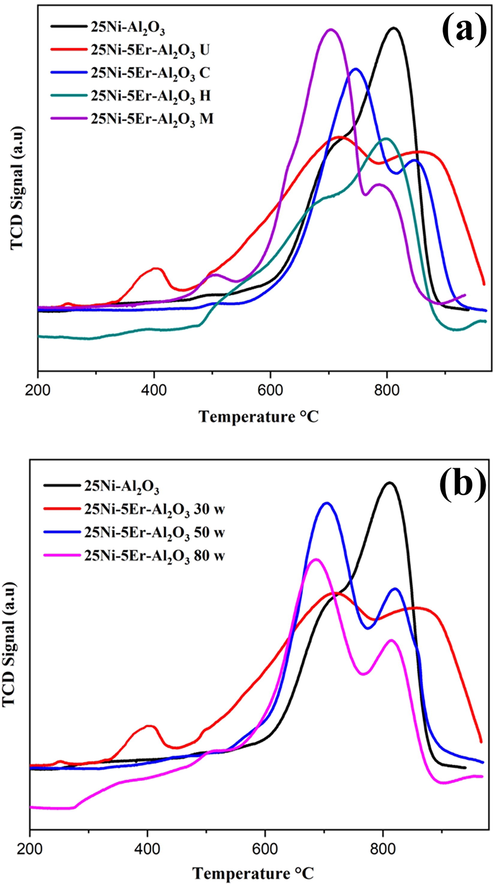

3.5 TPR data

A temperature programmed reduction (TPR) analysis was conducted for comparison of reduction properties of the as-prepared catalyst. Fig. 8 shows the H2-TPR spectra of the 25Ni-Al2O3 and 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalysts prepared with different fabrication methods. Different reduction peaks are identified based on the fabrication methods. For the 25Ni-Al2O3 catalyst, there are three major reduction peaks at 491 °C, 716 °C, and 814 °C. The peak located at 716 ℃ was assigned to the NiO reduction greatly interconnected by the catalytic carrier, and the peak at 814 ℃ was created by NiAl2O4 (Daroughegi et al., 2017). The band at 491 ℃ is associated with the Ni2O3 reduction. Three reduction bands appeared in the 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U catalyst. The band at 374 °C is the reduction of Er3+ ions, or bulk NiO or Ni2O3 (Li et al., 2016). It is noteworthy that the second reduction peak moved from 716 °C to 710 °C due to the addition of Er to the catalyst system. Besides, the reduction intensity peak of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U could be because of the lack of complex composition of nickel aluminate. Generally, the bands displayed at low temperatures are associated with NiO species reduction that interacts weakly with the catalytic carrier. The other bands at high temperatures are clarified by the reduction of nickel oxide with high interplay by the carrier. The reduction peaks moved to lower temperatures by changing the preparation procedure, which indicates that the variation in preparation led to the generation of more easily reducible nickel species. The 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U catalyst possesses a hydrogen consumption band in the range of 300 to 400 °C, which is related to the reduction of Er3O4 species to Er metal (Phaltane et al., 2017). The outcomes verified that the ultrasonic method with low sonication power (30 W) enhanced the catalyst reduction.

TPR spectra of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalysts with different fabrication method (M = microwave, H = hydrothermal, C = co-precipitation, and U = ultrasonic) (a), and (b) in three different sonication powers (30, 50, and 80 W).

3.6 Catalytic behavior

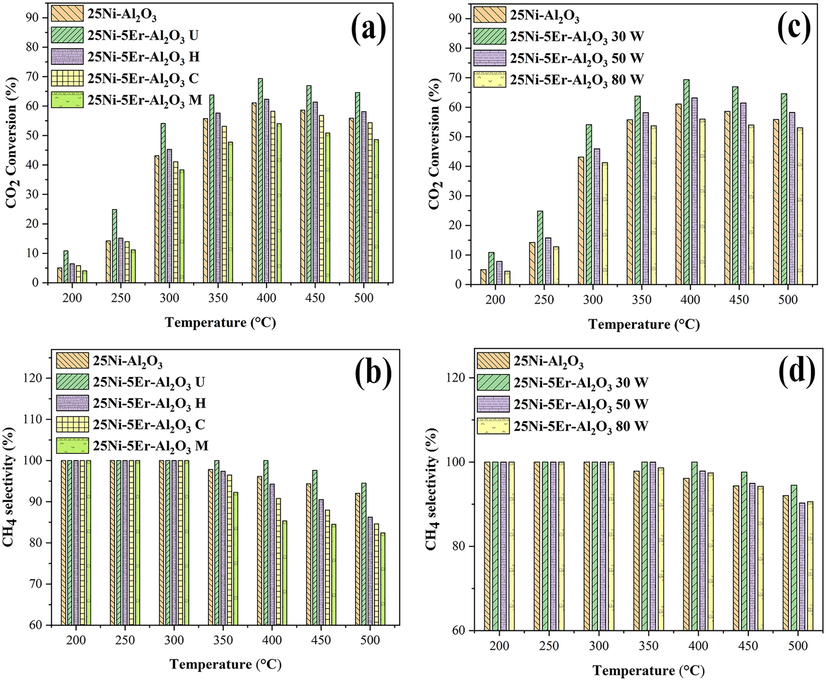

Fig. 9 represents the catalytic behavior of 25Ni-Al2O3 and 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 with different prepration methods. It has been shown that the catalytic performance of catalysts is organized as below: 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U > 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 H > 25Ni-Al2O3 > 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 C > 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 M (Fig. 9a). Hence, the carbon dioxide conversion and methane selectivity of the 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst fabricated with the ultrasonic technique (at low power (30 W)) manifested greater performance (Fig. 9c) at low temperatures. It was seen that a proper fabrication method could enhance CO2 adsorption by producing activated carbonate (CO32–) species and prevent the accumulation of nickel particles (Seok et al., 2002; Toemen et al., 2014). Moreover, due to the formation of Er2O3, the spinel structure of the modified catalyst was disordered during the calcinating process, and surface basicity properties were developed, the absorptivity of acidic CO2 molecules was improved, and the excellent catalytic action of Er-modified Ni-Al2O3 was obtained in CO2 methanation (Toemen et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2018a). In addition, the improved catalytic activity in terms of carbon dioxide methanation and methane selectivity of the Er-modified catalyst can occur owing to the production of active metal nanoparticles with wide distribution on the catalyst outside and high reduction at lower temperatures, as shown with the TPR and XRD data in Figs. 1 and 8. Corresponding to the outcomes of TPR (Fig. 8), the incorporation of Er advanced the reducing ability of the Ni-Al2O3 catalyst at low temperature, and it became possible to provide more Ni0 active sites by manipulating carbon dioxide methanation. It is noteworthy that the use of ultrasonic waves affects the particle size and distribution of activated metals as well as the catalytic ability. The lower carbon dioxide conversion of Er-modified catalysts prepared by microwave and co-precipitation methods contrary to unpromoted catalysts could be due to the slower reduction rate of the carbon dioxide methanation reaction and the smaller number of active regions, as confirmed by the TPR reports. Besides, Fig. 9 exposes the impact of reaction temperature on product selectivity and carbon dioxide conversion. This figure shows that enhancig the temperature of reaction from 200 °C to 400 °C significantly increases the CO2 conversion of the catalyst. Whereas, CO2 conversion, together with CH4 selectivity, was reduced when the temperature was above 400 °C owing to thermodynamic constraints and the reverse water–gas shift reaction (RWGS) (Eq.2). The catalytic activity of several catalysts was listed in Table 3. The 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 could contest with other modified catalysts listed in Table 3. We can designate this compound as a new and efficient catalyst for CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity.

Catalytic activity of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalysts with different fabrication method and in three different sonication powers (a and c) CO2 conversion and (b and d) CH4 selectivity, and H2:CO2 = 4:1 M ratio and GHSV = 25000 mL/gcath.

Catalysts

Preparation

Methods

Promoters Metal

Conditions

%CO2

Conversion

%CH4

Selectivity

Ref

Ni-Er-Al2O3

Sonochemical

Er

GHSV = 25000 mL g-1h−1

H2/CO2 = 4/169.38

100

This work

Ni/Pr-Ce

Sol-gel microwave assisted

Pr

GHSV = 25000 mL g-1h−1

H2/CO2 = 4/154.5

100

(Siakavelas et al., 2021b)

Ni/La-Pr-CeO2

Sol-gel-microwave assisted

La-Pr

GHSV = 25000 mL g−1.h−1

H2/CO2 = 4/155

100

(Siakavelas et al., 2021b)

Ni/CeO2-ZrO2

wetness -impregnation

Ce

GHSV = 20000 mL g-1h−1

55

99.80

(Ashok et al., 2017)

Na-Co/Al2O3

Incipient-wetness

impregnationNa

GHSV = 16000 mL g-1h−1

H2/CO2 = 4/152

67

(Zhang et al., 2020)

La1-xCaxNiO3

Pechini

Ca

GHSV = 16000 mL1·h−1

H2/CO2 = 4/157.7

100

(Lim et al., 2021)

Ce-Co3O4

co-precipitation

Zr

GHSV = 18000 mL g-1h−1

H2/CO2 = 4/158.2

100

(Zhou et al., 2018b)

Co–Cu–ZrO2

Co-precipitation

Co-Cu

H2/CO2 = 3/1

Co:Cu:ZrO2

20:40:4058

86.3

(Dumrongbunditkul et al., 2016)

Ca -NiTiO3

Coprecipitation-

impregnationCa

GHSV = 5000 Ml.g−1.h−1

H2/CO2 = 4/1,55

99.70

(Do et al., 2020)

Mg –Ni-Al2O3

Self-assembly (EISA)

Mg

GHSV = 15000 mL g-1h−1

H2/CO2 = 4/165

96

(Xu et al., 2017)

Ni-KOH/Al2O3

Incipient-wetness

impregnationK

GHSV = 16000 mL g-1h−1

H2/CO2 = 4/140

45

(Zhang et al., 2019)

3.7 Impact of operational parameters

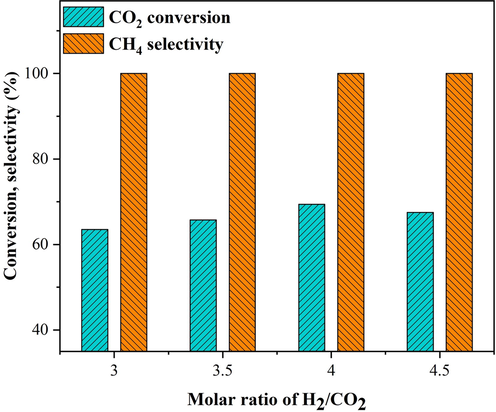

The CH4 selectivity and conversion of CO2 of the 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U catalyst (at 400 °C) vs molar ratio of H2:CO2 are presented in Fig. 10. The catalytic ability was developed by increasing the molar ratio from 3 to 4. Due to the stoichiometry of the carbon dioxide methanation reaction, when the molar ratio of H2: CO2 is smaller than 4, H2 plays as a limiting precursor, which generates the carbonate hydrogenation on the catalyst surface. Hence, as shown in Fig. 10, the hydrogenation development was boosted by increasing the molar of H2. Furthermore, no significant variations were detected in the CH4 selectivity by raising the molar ratio owing to the absence of CO2 decomposition at 400 ℃ (Rahmani et al., 2014).

Effect of H2:CO2 molar ratio on the catalytic activity of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst prepared by ultrasonic method at 400 °C, GHSV = 25000 mL/gcath.

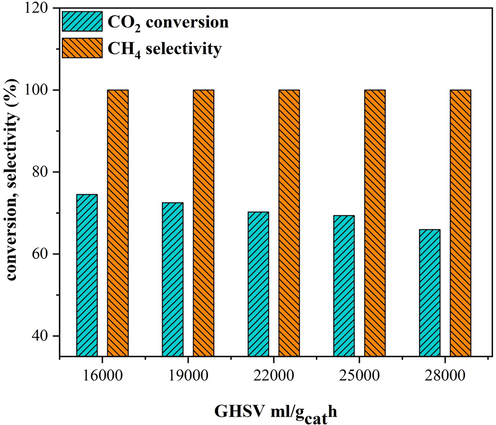

The effect of GHSV on the selectivity and catalytic behavior of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U catalyst at 400 ℃ for CO2methanation is presented in Fig. 11. As a result, reducing the catalytic efficiency of the catalyst by increasing GHSV from 16,000 to 28000 mL/gcath is related to a reduced residence time and a reduced quantity of reagents adsorbed at high GHSV.

Effect of GHSV on the catalytic activity of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst prepared by ultrasonic method at 400 °C, H2:CO2 = 4:1 M ratio.

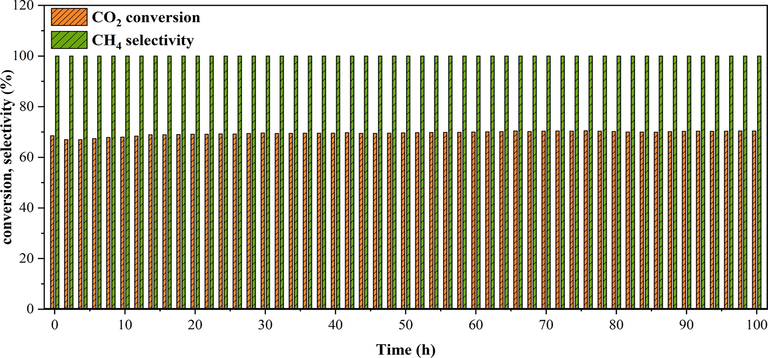

The durability essay on the 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U at 400 ℃ for 6000 min is depicted in Fig. 12. No notable decrease in the selectivity of methane and CO2 conversion was recognized, confirming that the 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 U catalyst was stable, durable, and resistant to deactivation of the catalyst influenced with the deposition of carbon and nickel particles sintering.

Stability test of the of 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalyst prepared by ultrasonic method at 400 °C, GHSV = 25000 mL/gcath and H2:CO2 = 4:1 M ratio.

4 Conclusions

In this research, 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 catalysts were manufactured by several prepration techniques, including ultrasonic, hydrothermal, microwave, and co-precipitation methods for the CO2 methanation reaction. BET studies have shown that the addition of erbium as a promoter led to the production of larger mesopores. In addition, the addition of erbium resulted in a stronger interaction between the aluminum oxide and the nickel species, which resulted in the production of smaller crystallite sizes with a higher distribution on the surface of the catalyst. For erbium addition, nickel-based alumina catalysts have advanced low-temperature performance in the methanation of carbon dioxide reaction. The catalyst prepared with the ultrasonic method showed superior catalytic activity of 69.38 % conversion of carbon dioxide and 100 % selectivity of methane at 400 °C. Furthermore, the highest adsorption capacity of CO2 was achieved for the Er-promoted catalyst prepared by ultrasonic, which can be presumed to have enhanced catalytic behavior. We can conclude that the 25Ni-5Er-Al2O3 has a permanent and durable catalytic capacity and can be regarded as an excellent inherent catalyst for the hydrogenation of carbon dioxide.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Farzad Namvar: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Software, Methodology. Masoud Salavati-Niasari: Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Project administration, Investigation, Data curation, Validation, Resources, Visualization, Funding acquisition. Makarim A. Mahdi: Software, Methodology, Data curation. Fereshteh Meshkani: Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization.

Acknowledgements

The authors are appreciative of the committee of Iran National Science Foundation; INSF (97017837), and the University of Kashan for financing this research by Grant No (159271/FN9).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Facile preparation and characterization of a novel visible-light-responsive Rb2HgI4 nanostructure photocatalyst. RSC Adv.. 2021;11(49):30849-30859.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The FTIR studies of gels and thin films of Al2O3–TiO2 and Al2O3–TiO2–SiO2 systems. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.. 2012;89:11-17.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Optimization of nickel and ceria catalyst content for synthetic natural gas production through CO2 methanation. Fuel Process. Technol.. 2019;193:114-122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Formation of zinc sulfide nanoparticles in HMTA matrix. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2009;255(21):8879-8882.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thermal stability and optical properties of HMTA capped zinc sulfide nanoparticles. J. Alloy. Compd.. 2010;496(1–2):665-668.

- [Google Scholar]

- Controlled synthesis and characterization of cerium-doped zns nanoparticles in hmta matrix. Int. J. Nanosci.. 2011;10(03):487-493.

- [Google Scholar]

- CO2-Mediated H2 storage-release with nanostructured catalysts: recent progresses, challenges, and perspectives. Adv. Energy Mater.. 2019;9(30):1901158.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced activity of CO2 methanation over Ni/CeO2-ZrO2 catalysts: influence of preparation methods. Catal. Today. 2017;281:304-311.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thermocatalytic decomposition of methane to COx-free hydrogen and carbon over Ni–Fe–Cu/Al2O3 catalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2016;41(30):13039-13049.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalysis mechanisms of CO2 and CO methanation. Catal. Sci. Technol.. 2016;6:4048-4058.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced low-temperature CO/CO2 methanation performance of Ni/Al2O3 microspheres prepared by the spray drying method combined with high shear mixer-assisted coprecipitation. Fuel. 2021;291:120127

- [Google Scholar]

- Acceleration of global warming due to carbon-cycle feedbacks in a coupled climate model. Nature. 2000;408(6809):184-187.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced activity of CO2 methanation over mesoporous nanocrystalline Ni–Al2O3 catalysts prepared by ultrasound-assisted co-precipitation method. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42(22):15115-15125.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterization and evaluation of mesoporous high surface area promoted Ni-Al2O3 catalysts in CO2 methanation. J. Energy Inst.. 2020;93(2):482-495.

- [Google Scholar]

- High stability of Ce-promoted Ni/Mg–Al catalysts derived from hydrotalcites in dry reforming of methane. Fuel. 2010;89(3):592-603.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effective thermocatalytic carbon dioxide methanation on Ca-inserted NiTiO3 perovskite. Fuel. 2020;271:117624

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and characterization of Co–Cu–ZrO2 nanomaterials and their catalytic activity in CO2 methanation. Ceram. Int.. 2016;42(8):10444-10451.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and temperature-induced morphological control in a hybrid porous iron-phosphonate nanomaterial and its excellent catalytic activity in the synthesis of benzimidazoles. Chem.–A Eur. J.. 2012;18(42):13372-13378.

- [Google Scholar]

- Rational catalyst and electrolyte design for CO2 electroreduction towards multicarbon products. Nat. Catal.. 2019;2(3):198-210.

- [Google Scholar]

- Highly efficient nickel-niobia composite catalysts for hydrogenation of CO2 to methane. Chem. Eng. Sci.. 2019;194:2-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 from 1994 to 2007. Science. 2019;363(6432):1193-1199.

- [Google Scholar]

- CO methanation over ZrO2/Al2O3 supported Ni catalysts: a comprehensive study. Fuel Process. Technol.. 2014;124:61-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Graphene Aerogel Supported Ni for CO2 Hydrogenation to Methane. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2021;60(33):12235-12243.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ni nanoparticles enclosed in highly mesoporous nanofibers with oxygen vacancies for efficient CO2 methanation. Appl Catal B. 2022;317:121715

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structure-Activity relationship of Ni-Based catalysts toward CO2 methanation: recent advances and future perspectives. Energy Fuel. 2022;36(1):156-169.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Supported cobalt nanorod catalysts for carbon dioxide hydrogenation. Energ. Technol.. 2017;5(6):884-891.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pedagogical content knowledge in science education: perspectives and potential for progress. Stud. Sci. Educ.. 2009;45(2):169-204.

- [Google Scholar]

- CO and CO2 methanation over Ni catalysts supported on alumina with different crystalline phases. Korean J. Chem. Eng.. 2017;34(12):3085-3091.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic properties of sprayed Ru/Al2O3 and promoter effects of alkali metals in CO2 hydrogenation. Appl. Catal. A. 1998;172(2):351-358.

- [Google Scholar]

- The promotion effects of Ni on the properties of Cr/Al catalysts for propane dehydrogenation reaction. Appl. Catal. A. 2016;522:172-179.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ni-exsolved La1-xCaxNiO3 perovskites for improving CO2 methanation. Chem. Eng. J.. 2021;412:127557

- [Google Scholar]

- Interface effects for the hydrogenation of CO2 on Pt4/γ-Al2O3. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2016;386:196-201.

- [Google Scholar]

- Self-assembled AgNP-containing nanocomposites constructed by electrospinning as efficient dye photocatalyst materials for wastewater treatment. Nanomaterials. 2018;8(1):35.

- [Google Scholar]

- Temperature-controlled hydrogenation of anthracene over nickel nanoparticles supported on attapulgite powder. Fuel. 2018;223:222-229.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of preparation method and Sm2O3 promoter on CO methanation by a mesoporous NiO–Sm2O3/Al2O3 catalyst. New J. Chem.. 2018;42(15):13096-13106.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dry reforming of methane over Ni supported on doped CeO2: new insight on the role of dopants for CO2 activation. J. CO2 Util.. 2019;30:63-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Characterisation of stoichiometric sol–gel mullite by fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Int. J. Inorg. Mater.. 2001;3(7):693-698.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydrogenation of CO2 over supported noble metal catalysts. Appl. Catal. A. 2017;542:63-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chem. 2019;5:526-552. CrossRef CAS;(b) DU Nielsen, X. M. Hu, K. Daasbjerg and T. Skrydstrup Nat. Catal 1 2018 244 254

- Photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue by hydrothermally synthesized CZTS nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron.. 2017;28(11):8186-8191.

- [Google Scholar]

- An efficient Z-scheme CdS/g-C3N4 nano catalyst in methyl orange photodegradation: Focus on the scavenging agent and mechanism. J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;335:116543

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The boosted activity of AgI/BiOI nanocatalyst: a RSM study towards Eriochrome Black T photodegradation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.. 2022;29(30):45276-45291.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aquatic biodegradation of methylene blue by copper oxide nanoparticles synthesized from Azadirachta indica leaves extract. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater.. 2018;28(6):2455-2462.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of highly active nickel catalysts supported on mesoporous nanocrystalline γ-Al2O3 for CO2 methanation. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.. 2014;20(4):1346-1352.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hydrogenation of CO2 to value-added products—A review and potential future developments. J. CO2 Util.. 2014;5:66-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanoscale microreactor-encapsulation of 18-membered decaaza macrocycle nickel(II) complexes. Inorg. Chem. Commun.. 2005;8(2):174-177.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Host (nanocavity of zeolite-Y)–guest (tetraaza[14]annulene copper(II) complexes) nanocomposite materials: synthesis, characterization and liquid phase oxidation of benzyl alcohol. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem.. 2006;245(1–2):192-199.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Flexible ligand synthesis, characterization and catalytic oxidation of cyclohexane with host (nanocavity of zeolite-Y)/guest (Mn(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Cu(II) complexes of tetrahydro-salophen) nanocomposite materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater.. 2008;116(1–3):77-85.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of pure cubic zirconium oxide nanocrystals by decomposition of bis-aqua, tris-acetylacetonato zirconium (IV) nitrate as new precursor complex. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2009;362(11):3969-3974.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mn-promoted Ni/Al2O3 catalysts for stable carbon dioxide reforming of methane. J. Catal.. 2002;209(1):6-15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solid-state synthesis method for the preparation of cobalt doped Ni–Al2O3 mesoporous catalysts for CO2 methanation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2021;46(5):3933-3944.

- [Google Scholar]

- Highly selective and stable nickel catalysts supported on ceria promoted with Sm2O3, Pr2O3 and MgO for the CO2 methanation reaction. Appl. Catal. B. 2021;282:119562

- [Google Scholar]

- Highly selective and stable Ni/La-M (M= Sm, Pr, and Mg)-CeO2 catalysts for CO2 methanation. J. CO2 Util.. 2021;51:101618

- [Google Scholar]

- Net reduction of CO2 via its thermocatalytic and electrocatalytic transformation reactions in standard and hybrid processes. Nat. Catal.. 2019;2(5):381-386.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of Ru/Mn/Ce/Al2O3 catalyst for carbon dioxide methanation: catalytic optimization, physicochemical studies and RSM. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng.. 2014;45(5):2370-2378.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of ceria and strontia over Ru/Mn/Al2O3 catalyst: catalytic methanation, physicochemical and mechanistic studies. J. CO2 Util.. 2016;13:38-49.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comparison of extended and sigma-point Kalman filters for tightly coupled GPS/INS integration. AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference and Exhibit. 2005

- [Google Scholar]

- Alkaline-promoted Ni based ordered mesoporous catalysts with enhanced low-temperature catalytic activity toward CO2 methanation. RSC Adv.. 2017;7(30):18199-18210.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improved stability of Y2O3 supported Ni catalysts for CO2 methanation by precursor-determined metal-support interaction. Appl Catal B. 2018;237:504-512.

- [Google Scholar]

- Promotion effect of CaO modification on mesoporous Al2O3-supported Ni catalysts for CO2 methanation. Int J. Chem. Eng. 2016:2016.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ni/Al2O3-ZrO2 catalyst for CO2 methanation: the role of γ-(Al, Zr)2O3 formation. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2018;459:74-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Regulation the reaction intermediates in methanation reactions via modification of nickel catalysts with strong base. Fuel. 2019;237:566-579.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impacts of alkali or alkaline earth metals addition on reaction intermediates formed in methanation of CO2 over cobalt catalysts. J. Energy Inst.. 2020;93(4):1581-1596.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of Zr, Ce, and La on Co3O4 catalyst for CO2 methanation at low temperature. Chin. J. Chem. Eng.. 2018;26(4):768-774.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mn and Mg dual promoters modified Ni/α-Al2O3 catalysts for high temperature syngas methanation. Fuel Process. Technol.. 2018;172:225-232.

- [Google Scholar]

- Probing the surface of promoted CuO-Cr2O3-Fe2O3 catalysts during CO2 activation. Appl Catal B. 2020;271:118943

- [Google Scholar]

- Vacancy engineering of the nickel-based catalysts for enhanced CO2 methanation. Appl. Catal. B. 2021;282:119561

- [Google Scholar]