Phytochemical, antioxidant, enzyme inhibitory, thrombolytic, antibacterial, antiviral and in silico studies of Acacia jacquemontii leaves

⁎Corresponding authors. kashifur.rahman@iub.edu.pk (Kashif-ur-Rehman Khan), umair_uaf@hotmail.com (Muhammad Umair)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The main objective of this work was to gain insight into biological propensities, and bioactive phytochemicals of Acacia jacquemontii Benth, a wild plant providing medicinal components, as well as to establish a link between its phytochemical profile and biological activities. Phytochemical profiling revealed the presence of a higher amount of total phenolic (271.44 ± 4.41 mg GAE/g) and flavonoid contents (216.47 ± 5.82 mg QE/g) in methanolic extract (MEAJ), and as compared to n-hexane fraction (HEAJ) and stronger biological activities of MEAJ were possibly linked to the higher bioactive contents. The freshly collected plant leaves showed a strong antioxidant potential (total antioxidant capacity 1.03 ± 0.19 mmol TE/g), which was found even stronger in dried methanolic extract (TAC; 4.36 ± 1.12 mmol TE/g), moreover, MEAJ also showed strong antioxidant potential when investigated by different antioxidant assays (DPPH; 154.04 ± 2.47, ABTS; 122.36 ± 0.80, FRAP; 453.18 ± 5.9, CUPRAC; 1389.97 ± 5.32 mg TE/g). The MEAJ showed good tyrosinase inhibition activity (71.69 %), compared with 83 % inhibition by kojic acid. Ten major compounds identified by GC–MS were docked and eight legends showed lower binding energies (-6 to −7.8 kcal/mol) compared with kojic acid (-5.9 kcal/mol), which shows the possible role of these compounds in the anti-tyrosinase activity of the extract, and the ADMET analysis predicted the drug-likeness and safety profile of the studied compounds. The thrombolytic effect of MEAJ was 56.41 ± 0.75 to 57.15 ± 1.41 % which was comparable with streptokinase (82.44 ± 1.15 to 84.14 ± 0.95 %). Antibacterial activity of MEAJ was also good (MEAJ; 0.5–2.0 mg/mL, and co-amoxiclav; 5.0–12.5 µg/mL), and the highest activity was observed against Bacillus subtilis (MEAJ; 0.5 mg/mL, co-amoxiclav; 5.0 µg/mL). The antiviral activity of MEAJ was highly strong (HA titer; 00 to 08) against all the tested strains. It can be concluded that A. jacquemontii is a prospective source of phytochemicals with strong biological activities, and their usage in formulations of natural products and pharmaceuticals is recommended, however, further research may address the discovery and development of novel drugs for the pharmaceutical industry.

Keywords

Acacia jacquemontii

Bioactive compounds

Secondary metabolites

Biological activities

Molecular docking

Natural products

1 Introduction

There are two major groups of plant-derived natural products (primary and secondary). The secondary natural products (secondary metabolites) have become the endless hope for medicinal chemists to develop lead compounds and novel drugs from these resources of nature. Moreover, the plant extracts investigated by popular techniques of biological screening and chemical characterization have delivered new bioactive compounds for use as medicines i.e., digoxin from the flowers of Digitalis lanata and morphine from Papaver somniferum (Kowalski 2018, Dilshad et al., 2022). Although plants are biodiverse resources which are still under-explored (by scientific approach) for their application in medicinal systems, however, 73 % of pharmaceutical drugs are derived from natural products of traditional medicine (Wangchuk 2018, Bursal et al., 2021). More often, drugs derived from natural sources also gained prime importance due to the safety and efficacy of these agents compared to synthetic drugs (ul Hassan et al., 2019), and the research is still increasing rigorously to investigate the plant extracts for their bioactive phytochemicals and pharmacological properties (Chen et al., 2022).

Some plant secondary metabolites including polyphenols, flavonoids, fatty acids, terpenoids and steroids, are structurally and pharmacologically active compounds and many of them may act as antimicrobial agents in addition to their versatile biological activities (Bursal et al., 2019, Dahibhate et al., 2022). Microbial infections and resistance to antibiotics have become a big issue due to health threats for human (Murray et al., 2022), and 75 % of drugs employed for infectious diseases are natural products or their derivatives (McChesney et al., 2007). The COVID-19 pandemic had an impact on the healthcare system and people were also concerned about their appearance and paid attention to skincare (Pranskuniene et al., 2022). So, the study aimed for the biological screening for antibacterial, antiviral, thrombolytic, and tyrosinase inhibitory potential as well as antioxidant activities. Phytochemical evaluation of the plant was done to gain basic knowledge of their link with biological activities. The Acacia jacquemontii was selected based on ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology but less explored scientifically involving wet-lab or dry-lab.

Acacia jacquemontii Benth. also known as Chota babool, Bhu-baonli or Baonli, belongs to the genus Acacia, a member of the Fabaceae family. It is a xerophytic shrub or small tree, characterized by zig-zag branches. A. jacquemontii is distributed throughout semi-arid regions of the world. Bark, leaves, and gum are the most commonly used parts of Acacia species in ethnomedicine (Subhan et al., 2018). However, the selected plant also provides certain products like fodder, fruits, and fibers in addition to gums. A decoction of the A. jacquemontii bark has traditionally been used to cure fever, muscle pain, and cough. Analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic effects were also supported by in vivo studies (Ashfaq et al., 2016). This plant’s gum is also used as a health tonic in a variety of food products. Patients with accidents resulting in serious injury and women following childbirth may get benefits from food preparation of gum for quick recovery (Choudhary et al., 2009). Gum also contains demulcent and astringent characteristics, so it’s frequently used in medicine. Gum is heated and administered once a day for one month to treat asthma. Gum is also used to treat mouth ulcers (Al-Mosawi and Thevenet 2006).

However, the genus of Acacia has more versatile and scientifically revealed uses. Preparations made from various parts of Acacia species are traditionally used for diarrhea, diabetes, gastrointestinal disorders, skin ailments and to treat inflammatory diseases (Thambiraj and Paulsamy 2015). Another study revealed the antioxidant, antibacterial, cytotoxic, and other activities from the extracts of Acacia species (Amoussa et al., 2020). According to ethnobotanical data methanolic extracts of A. nilotica pods have been claimed against HIV-PR (Maldini et al., 2011, Rehman et al., 2011) and found this specie has good activity against hepatitis C virus, and for skin disorders (Saini et al., 2008). The antiplatelet aggregation activity of this species was reported in an animal model (Shah et al., 1997). So, the investigation of the antibacterial, antiviral, and thrombolytic of the plant is designed to study. Despite the numerous benefits of A. jacquemontii and its genus members, this plant has not been thoroughly investigated for application in the pharmaceutical and food industry. Therefore, the present study is designed to determine the phytochemical profiling via, total bioactive contents (polyphenols and total flavonoids) and GC–MS analysis, a comprehensive pharmacological screening was done through antioxidant, antibacterial, antiviral, thrombolytic and enzyme inhibitory assays to disclose the ingredients of natural bioactive plant products, natural food supplements and pharmaceuticals. Moreover, in silico studies were performed to predict the effect of major identified compounds.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Collection and identification of the plant

Leaves of the plant were collected in March 2021 from the Cholistan Desert of Bahawalpur, Punjab, Pakistan. Plant material was identified by the Cholistan Institute of Desert Studies (CIDS) in The Islamia University of Bahawalpur and recorded as CIDS/ IUB-1901/63.

2.2 Antioxidant potential estimation of fresh leaves of A. jacquemontii

2.2.1 Extraction of antioxidant enzymes from leaves

The freshly collected leaves had been washed using distilled water and air dried to remove surface water. Then sample leaves were packed in airtight plastic bags and stored in a refrigerator for enzymatic antioxidant, studies. The 0.3 g of fresh leaves were ground in a 2 mL volume of 50 mM cold phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) solution to obtain fresh leaves sample extract. After that, the sample was centrifuged at 15,000 × g at 4 °C for 20 min. Results were exhibited as units of enzyme per gram of fresh sample (units/g f. wt.). After the separation of extract from residues by filtration, the supernatant layer of liquid was used to determine enzymatic antioxidant activity (Güneş et al., 2019).

2.2.2 Antioxidant enzyme assays

To determine the superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was performed by following the method reported in the literature (Li et al., 2015). Enzyme activity (one unit) was defined as the quantity of enzyme which causes 50 % inhibition of photochemical reduction of NBT. The peroxidase activity (POD) was determined by using a procedure described in the literature (Jameel et al., 2021). POD activity was equal to one unit when the change in absorbance occurred at 0.01/minute. Catalase (CAT) activity was measured following Jameel et al., (2021). For the determination of enzyme activity, a change of absorbance at 0.01/minute was one unit of enzyme activity per gram of fresh leaves of the plant. Ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity was determined through an already-established method (Dixit et al., 2001). The rate of oxidation of ascorbic acid had been measured by noting the decline in absorbance at 290 nm after every 30 s.

2.2.3 Total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of fresh sample

A phosphomolybdenum assay was followed to do this study as reported in the literature with slight modifications (Osman et al., 2022). The molybdate reagent contained 1 mL each of 0.6 M sulfuric acid, 28.0 mM sodium phosphate, and 4.0 mM ammonium molybdate and made up the volume to 50 mL by adding distilled H2O. After extraction of leaves of A. jacquemontii by homogenization, following, the already reported method with some modifications (Pellegrini et al., 2006), the supernatant layer of the extract was taken (100 µL extract) and poured into a test tube, which was already contained 3 mL of distilled water and 1 mL of molybdate reagent. The test tube was incubated at 95 °C for 90 min. After that, the temperature of the test tube was allowed drop till it reached room temperature, taking a time of 20–30 min, and the absorbance of this reaction mixture was measured at 695 nm. Mean values were noted after three independent samples and results were reported in micromoles equivalents of Trolox (as a standard in this study) per gram of fresh leaves weight of sample along with standard deviation (mmol TE/g f. wt).

2.3 Extraction of the dried sample of the plant leaves

The shade-dried leaves (2 kg) of the plants were crushed into a coarse powder and macerated with 5 L of 80 % methanol (Safdar et al., 2017) for 7 days at 25 °C. This solvent phase was used for extraction due to the evidence of good extraction of polyphenols and methanol was also considered a good solvent for the extraction of flavonoid secondary metabolites of plants (Truong et al., 2019). The extract was decanted and filtered, and the marc was macerated again for exhaustive extraction. Filtrates were mixed and concentrated through a rotary evaporator (Heildoph USA) under reduced pressure. After concentration and subsequent drying, methanol extract was obtained as a gummy solid (50 g). After separating 5 g of crude extract, the remaining 45 g of dried matter was extracted, with n-hexane (5 L) to obtain a non-polar fraction (4 g of greenish liquid), and both samples were used for further analysis.

2.4 Phytochemical studies by quantification of total bioactive contents and GC–MS analysis

Folin-Ciocalteu (FC) method (Dilshad et al., 2022) with slight modification was employed to determine the total phenolic contents (TPC). The sample solution was prepared by dissolving the dried extracts in methanol (concentration of 1 mg/mL), and the same is used for TFC analysis. Solution of gallic acid (used as standard) was prepared in the methanol with varying concentrations (10, 20, 40, 80, 100 and 200 µg/mL), and the standard curve of gallic acid was drawn. Solutions of extract or standard in the volume of 200 µL had been taken in an Eppendorf tube and added to 200 µL of FC reagent. The ingredients of the mixture were mixed to obtain a uniform solution with a vortex mixer. After that, 0.8 mL of sodium carbonate had been added to the solution and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. A volume of 200 µL of the obtained solution was taken into 96 well microtiter plate and the absorbance was measured at 765 nm by using the BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader. The total phenolic content was written in milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry extract (mg GAE/g extract).

The total flavonoids contents (TFC) were demonstrated by using an experiment already present in the literature (Basit et al., 2022). The standard curve of quercetin was plotted by using the concentrations of 10, 20, 40, 80, 100 and 200 µg/mL. The stock solution of both samples was prepared in methanol (1 mg/mL). A mixture of 1 mL extract with 4 mL deionized water and 300 µL of NaNO3 plus a 300 µL volume of 10 % AlCl3 solution was added to the test tubes. The contents of the mixture were subjected to a vortex mixer. After that 2 mL of 1 M NaOH solution was mixed with the previously prepared solution. This mixture was finally incubated for a time of 6 min, at room temperature. Then a 2.4 mL volume of deionized water was also added to the incubated solution. Finally, 200 µL of this solution was taken in a 96-microtiter plate, and absorbance was measured at 510 nm with the help of a BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader. Total flavonoids contents were written in milligrams of quercetin equivalents to one gram of dry extract (mg QE/g extract) using the quercetin as standard.

The procedure followed for GC–MS was reported by Ezhilan and Neelamegam (2012). The n-hexane fraction from the methanolic extract of leaves of A. jacquemontii was analyzed by utilizing the instrument, GC–MS Agilent 7890B with Mass Hunter acquisition software. This instrument has a non-polar column of HP-5MS ultra inert capillary with proportions of 30 mm × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 µm films. The carrier gas was helium, which was used at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/minute. The injector was operated at 250 °C and the oven temperature was set in a strategy that it was kept at 50 °C for 5 min, then a gradual increase of temperature was done to 250 °C at the rate of 10 °C /minute, and finally to 300 °C for 10 min at the rate of 10 °C/minute. The metabolites were identified by using the NIST library, while the percentage peak area for each metabolite was computed from the total area of peaks.

2.5 Antioxidant activities of dried plant extract

2.5.1 Radical scavenging activities

The radical scavenging antioxidant potential of extracts was measured through 2,2-azinobis 3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) and 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assays. DPPH radical scavenging assay was performed by the already reported method (Shahzad et al., 2022) with some modifications. The absorbance of the test solution was measured by setting the wavelength of 517 nm with the help of the BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader. The results of the experiment were written as Trolox equivalents per gram of dried extract (mg TE/g dried extract). For the ABTS assay, we adopted a previously reported procedure and results were recorded as mg of Trolox equivalent in one gram of extract (mg TE/g extract).

2.5.2 Reducing power assays

The reducing capacities of extracts were analyzed by utilizing CUPRAC (cupric-reducing antioxidant capacity) and FRAP (ferric-reducing antioxidant power). CUPRAC assay was performed by following the already described procedure. For the FRAP assay, we followed the mentioned protocol in the literature (Ghalloo et al., 2022), and Trolox was used as standard in this assay.

2.5.3 Total antioxidant capacity (TAC)

A volume of 0.30 mL of the sample solution (1 mg/mL in methanol) was combined with 3.0 mL of molybdate reagent solution (4.0 mM ammonium molybdate, 0.60 M sulfuric acid and 28.0 mM sodium phosphate), and incubated for 90 min at 95 °C. Finally, the absorbance was recorded at 765 nm against a blank solution (0.30 mL methanol and 3.0 mL reagent solution). The results were expressed as millimoles of Trolox equivalents per gram of dry extract (mmol TE/g extract) (Ahmed et al., 2022).

2.6 Tyrosinase inhibition assay

The Solution (1 mg/mL in methanol) of samples (25 µL) was mixed to a 40.0 µL solution of tyrosinase (200 units /mL) and 100.0 µL PBS (40.0 mM, pH 6.8) in a 96 well microtiter plate. This prepared solution was then incubated, for 15 min at ambient temperature. l-DOPA (10 mM) was in the volume of 40 µL added to the incubated blend to start the reaction. Afterwards, that solution was incubated again for 10 min. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was taken at 492 nm. A blank solution was also prepared without the extract/fraction and analyzed according to this procedure. Kojic acid was used as a standard in this activity (Yousuf et al., 2022).

2.7 In vitro thrombolytic study

The thrombolytic (clot-dissolving) activity of A. jacquemontii extracts was determined through the previously reported method (Sayeed et al., 2014). About 5 mL of streptokinase (SK) was added to distilled water (sterile) to the commercially available streptokinase (lyophilized) vial (Polamin Werk GmbH, Herdecke, Germany) of 15, 00,000 I.U. and shaken properly to make a stock solution as a standard reagent. After that 100.0 μL of solution of the enzyme (30,000 I.U) was utilized for thrombolytic activity. Approximately 5 mL of blood was drawn (from a vein) from five healthy human volunteers, which did not have a history of oral contraceptive or anticoagulant therapy (approval of the protocol was given by the institutional ethics committee of the Islamia University of Bahawalpur). Eppendorf tubes were weighed and 500 μL of blood was dropped into each of the five tubes to form clots. After clot formation, serum was removed completely, through aspiration (the clot should not be disturbed). The weight of the thrombus is determined as clot weight = weight of tube with clot – the weight of tube alone. Then 100.0 μL of extract of 1 mg/mL concentration, was added to each tube. In the control tubes, 100.0 μL of streptokinase (as a positive control) and 100.0 μL of distilled H2O (as a non-thrombolytic control) were added individually. After incubation for 90 min at 37 °C, we removed the liquid, and the weight of the test tubes was measured again to calculate the percentage of clot lysis. The difference in weight, before and after clot lysis was calculated and expressed as a percentage of thrombolysis (mean % of thrombolysis).

2.8 Antibacterial activity

2.8.1 Bacterial strains for study

The Bacillus subtilis ATCC1692, Micrococcus luteus ATCC 4925, Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 8724, Bacillus pumilus ATCC 13835, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Bordetella bronchiseptica ATCC 7319, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 9027 were the Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains of bacteria investigated in this analysis. The strains were obtained from the Bahawalpur Drug Testing Laboratory (DTL). The candidate strains were able to survive in a variety of environments including extreme conditions.

2.8.2 Preparation of inoculums

The bacterial inoculum of each strain was prepared from the previously preserved cultures (24 h old). Afterwards, a few colonies of each strain were taken and added to test tubes with 10 mL of previously sterilized nutrient broth medium. Then test tubes were incubated at 37 °C overnight. The bacterial colonies were diluted to a cell density of 105 CFU/mL (Ahmad et al., 2019).

2.8.3 Micro-dilution method

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined by the microtitre broth dilution method by following the guidelines and procedures reported in the literature after slight modifications (Dahibhate et al., 2022). The MIC assay was performed on methanolic extract (MEAJ) and n-hexane fraction (HEAJ). Serial dilution of both samples was done for the determination of MIC. Stock solutions of both samples were prepared in Eppendorf tubes by dissolving respective samples in dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO) and made a final concentration of 64 mg/mL. Then the serial dilutions from this stock solution were prepared in the range of 32 mg/mL to 0.25 mg/mL using Mueller–Hinton broth in a 96-well microplate. The bacterial inoculum containing a cell density of nearly 105 CFU/mL was prepared from a 24 h freshly cultured plate, and a volume of 100 μL of this bacterial suspension was inoculated into each well. A negative control well (without sample and standard) and a positive control well were also studied for each strain of bacteria. The microtiter plates were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Then a volume of 40 μL of a 0.40 mg/mL solution of INT was added to each well (to indicate the bacterial growth). The microtiter plates were incubated again, at 37 °C for 30 min and the MIC values were visually observed and reported. The MIC was the lowest concentration of each sample showing no visible growth (observed first clear well). The experiment was repeated to confirm the activity, and the values were taken as duplicates. Co-amoxiclav was used as a standard antibacterial drug (starting conc. 0.10 mg/mL in DMSO) to observe the sensitivity of the experimental strains and to compare the results of samples, and DMSO (without sample/standard) was used to perform the experiment for negative control. The final concentrations for these experiments ranged from 25.00 μg/mL to 0.19 μg/mL.

2.9 Antiviral activity

2.9.1 Inoculation of viruses in chicken embryonated eggs (cultivation of viral strains)

Chicken embryonated eggs were used as a medium for inoculation. All viral strains were cultured in embryonated eggs of chicken (7–11 days old), obtained from the poultry farm, established by the government of Pakistan in Model Town A, Bahawalpur. A 5 cc syringe was used to inoculate the viral strains through the chorioallantoic route. After incubation at 37 °C for 48–72 h, allantoic fluid was dropped in Eppendorf to preserve at 4 °C and subjected to haemagglutination (HA) and indirect haemagglutination (IHA) to measure the titers of the virus. The highest titer score of viral strains was obtained which was 1024 for AIV (Avian Influenza Virus; H3N2) and NDV (Newcastle Disease Virus). For IBDV (Infectious Bursal Disease Virus) and IBV (Infectious Bronchitis Virus), viruses the highest titer score was 2048. These titers were used as a control in this assay (Andleeb et al., 2020).

2.9.2 Heamagglutination (HA) test procedure

First of all, a 1 % RBCs solution was prepared using chicken blood. After that, we took a 96-well round bottom microtiter plate and added 50 µL of phosphate buffer solution to each well. 50 µL of the viral sample or allantoic fluid was added in the first column of wells and serially diluted to the 11th well. Negative control (phosphate buffer solution only) was left in the 12th well. 50 µL of 1 % RBCs solution was poured into each well. Then, the sample extract (1 mg/mL in DMSO) of 50 µL volume was added to each well except for negative control. Incubated, the plate for 2–3 h at 37 °C. Uniform reddish colors showed positive results, and red dots at the bottoms of the wells showed negative results. The highest dilution number was the HA titer which show a positive result (Harazem et al., 2019). The experiment was used for testing the titer of NDV, IBV, IBDV and H9N2 strains of the virus.

2.10 In silico studies

2.10.1 Molecular docking studies for tyrosinase inhibition

Structures of tyrosinase with the highest resolution were obtained from the protein data bank as pdb format. Structures of selected ligands and kojic acid were downloaded from the PubChem database for docking studies. The structures of receptors and ligands were prepared for docking by using AutoDock Tools-1.5.6, Discovery Studio 2021 Client, and open babel GUI. All the water molecules in the structures were removed. Polar hydrogen and Kollman charges were added.

The molecular docking of selected and prepared ligands (phytochemicals and kojic acid), and receptors was performed with AutoDock vina of PyRx software (Abdulfatai et al., 2019). The maximum binding energies and binding interactions between ligands and receptor molecules were determined. The minimum energy position represents the maximum binding affinities. Results of receptor-ligand interactions were made visible with Discovery Studio 2021 Client.

2.10.2 ADMET prediction studies

Measuring the absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity (ADMET) are the essential tools for any compound before its selection as a drug candidate. The online web tool Swiss ADME ( https://www.swissadme.ch/index.php) was used to obtain the characteristics related to absorption and distribution of the major compounds identified from GC–MS and depicting equal to or lower score of binding energies than kojic acid (standard for tyrosinase inhibition). Excretion assessment of these compounds was done by using the online web tool pkCSM ( https://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/pkcsm/prediction), while toxicity was predicted by using Protox-II ( https://tox-new.charite.de/protox_II/).

2.11 Statistical analysis

The experiments were performed in triplicates and results were written in the form of mean ± S.D (standard deviation). The data was evaluated through SPSS version 20.0. Statistical analysis of results was done through ANOVA (one-way analysis of variance). P ≤ 0.05 values were considered as significant.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Phytochemical studies by quantification of total bioactive contents and GC–MS analysis

The total bioactive contents (TBC) of methanolic extract (MEAJ) and n-hexane fraction (HEAJ) of the leaves (Table 1) were determined through total phenolic contents (TPC), of the plant (Daneshzadeh et al., 2020). The methanolic extract indicated a higher concentration of phenolic contents (271.44 ± 4.41 mg GAE/g extract) as compared to the total flavonoids contents with a value of 216.47 ± 5.82 mg QE/g of the dry extract. The quantities seem to be very high and the results of this study are substantiated by the findings of Awan et al., they found that the ethyl acetate extract of A. jacquemontii contains a higher quantity of TPC than TFC (83.83 mg GAE/g and 77.06 mg QE/g, respectively) (Awan et al., 2021). Moreover, methanol proved to be a more efficient solvent for the extraction of polyphenols from plants (Zhao et al., 2006, Świątek et al., 2021), this may be the reason for such a high quantity of TPC and TFC in our study as compared to the ethyl acetate extract of the previous study. However, the n-hexane fraction showed a lesser quantity of TPC (106.16 ± 3.84 mg GAE/g extract) and TFC (78.82 ± 3.32 mg QE/g of a dry fraction). It was observed that this plant contains more polyphenolic contents in the methanolic extract as compared to the n-hexane fraction, and previous studies on the genus also authenticate our results (Amoussa et al., 2020). The readings were taken as triplicates and shown in Table 1. Our findings were also consistent with the reported results from leaves of a closely related specie A. nilotica, in which researchers found that methanolic extract contain high phenolic content values (166 mg GAE/g of dry extract) (Yadav et al., 2018). Previous studies also support our findings by declaring a high amount of phenols and flavonoids in the methanolic extract from leaves of plants (Mayouf et al., 2019), and the high quantity of phenolic compounds confers the plant with potential for antioxidant, antibacterial, antiviral and other biological activities (Marín et al., 2015). Findings from the literature also evidenced that the antioxidant, anticancer and some other properties of plant extracts are due to the presence of a high amount of flavonoids (Altemimi et al., 2017). So, our findings of good values of phenolic and flavonoid contents revealed our plant as a good source of bioactive molecules for the formulation of herbal products and pharmaceuticals (See Fig. 1).

| Sample code (1 mg/mL) | TPC (mg GAE/g dried extract ± SD) | TFC (mg QE/g dried extract ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| MEAJ | 271.44 ± 4.41 a | 216.47 ± 5.82 a |

| HEAJ | 106.16 ± 3.84b | 78.82 ± 3.32b |

MEAJ = Methanolic extract of A. jacquemontii, HEAJ = n-hexane extract of A. jaquemontii. Different letters in same column indicate significant differences in the tested extracts (p < 0.05).

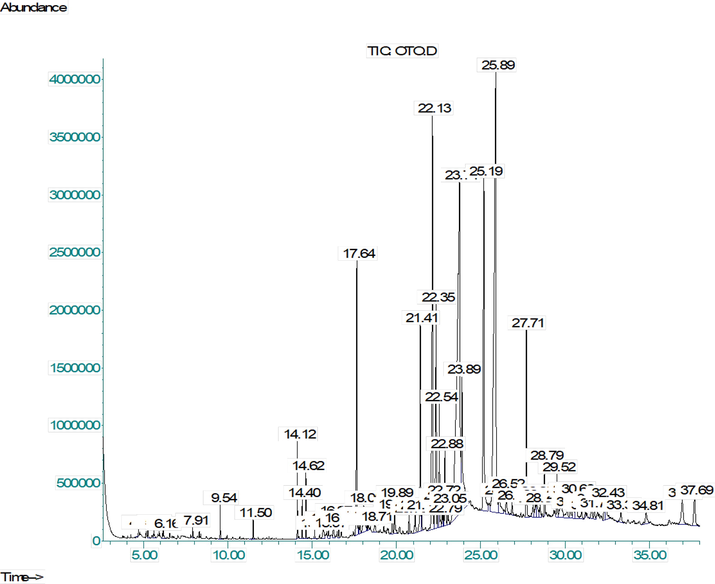

- GC–MS chromatogram of the n-Hexane soluble fraction of methanolic extract from A. jacquemontii leaves.

Further chemical profiling for the identification of secondary metabolite (Table 2) was done through GC–MS investigation of the n-hexane fraction. As a result of GC–MS analysis, we identified 65 compounds, and the major class of bioactive phytochemicals was terpenoid (39.28 %). Aldehydes (21.12 %) were the second major portion of HEAJ, while alkenes and alkynes collectively contributed 10.6 % of the total peak area, and compounds found in lesser quantity were alcohols (9.58 %), Napthoic acids (4.23 %), Phenanthrenes (2.01 %), steroids and their ester (1.77 %), while fatty acids were<1 %. Most of the identified compounds have great biological significance like (+)-4-carene is used as larvicidal for malaria and dengue mosquitoes (Govindarajan et al., 2016), α-pinene shows anticoagulant, antiproliferative, antimicrobial, antimalarial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and analgesic activities (Salehi et al., 2019), and α-terpinene has strong antioxidant, antimicrobial and antifungal potential (Rudbäck et al., 2012). Caryophyllene showed a wide range of applications like anti-inflammatory, diseases of the nervous system (stroke, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis), atherosclerosis, tumors (melanoma, colon, pancreas, breast, lymphoma and glioma cancer), potentiation of anticancer medicines (Francomano et al., 2019). cis-Z-α-bisabolene epoxide (Roukia et al., 2013) and 9-octadecyne have shown antioxidant, antimicrobial and antiviral activity (Vanitha et al., 2019). The 14-methyl-pentadecanoic acid has strong anticancer and antioxidant activity (To et al., 2020), and n-hexadecanoic acid is a long-chain fatty acid which shows good anti-inflammatory effects (Aparna et al., 2012). The 1H-naphtho[2,1-b]pyran, 3-ethenyldodecahydro-3,4a,7,7,10a-pentamethyl- is an antimicrobial compound (Bedair et al., 2001) and 3-eicosyne have antioxidant activity (Mary and Giri 2016). Octadecanoic acid has hypocholesterolemia and antibacterial activity (Abubakar and Majinda 2016). It also possesses antioxidant, cytotoxic and hepatoprotective effects (Ganesh and Mohankumar 2017). Caryophyllene oxide has anticancer, analgesic, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant (Nguyen et al., 2017). The 1H-3a,7-methanoazulene, octahydro-1,4,9,9-tetramethyl- have anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial (Arora and Saini 2017).

| Sr. no. | Retention time | Predicted compounds | Molecular formula | Molecular weight | Chemical class | Relative content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.69 | (+)-4-Carene | C10H16 | 136.23 | Terpenoid | 0.03 |

| 2 | 5.25 | α-Pinene | C10H16 | 136.23 | Terpenoid | 0.10 |

| 3 | 5.61 | α-Terpinene | C10H16 | 136.23 | Terpenoid | 0.16 |

| 4 | 6.16 | 2,6-Dimethyl-1,3,5,7-octatetraene | C10H14 | 134.22 | Alkene | 0.17 |

| 5 | 7.91 | Benzene, tert-butyl- | C10H14 | 134.22 | Aromatic hydrocarbon | 0.09 |

| 6 | 9.53 | Caryophyllene | C15H24 | 204.35 | Terpenoid | 0.31 |

| 7 | 11.50 | cis-Z-α-bisabolene epoxide | C15H24O | 220.35 | Epoxide | 0.20 |

| 8 | 14.12 | Bicyclo[3.1.1]heptane, 2,6,6-trimethyl- | C10H18 | 138.25 | Terpenoid | 0.79 |

| 9 | 14.40 | 1-Ethynyl-1-cyclooctanol | C10H16O | 152.23 | Alcohol | 0.34 |

| 10 | 14.62 | 9-Octadecyne | C18H34 | 250.50 | Alkyne | 0.56 |

| 11 | 15.14 | Pentadecanoic acid, 14-methyl- | C16H32O2 | 256.42 | Fatty acid | 0.10 |

| 12 | 15.66 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | C16H32O2 | 256.42 | Fatty acid | 0.36 |

| 13 | 15.97 | Naphthalene, decahydro-4a-methyl-1-methylene-7-(1-methylethenyl)-, [4aR-(4aα,7α,8aβ)]- | C15H24 | 204.35 | Terpenoid | 0.18 |

| 14 | 16.27 | 5-Eicosene, (E)- | C20H40 | 280.50 | Alkene | 0.36 |

| 15 | 16.56 | 1H-Naphtho[2,1-b] pyran, 3-ethenyldodecahydro-3,4a,7,7,10a-pentamethyl- | C20H34O | 290.48 | Terpenoid | 0.15 |

| 16 | 17.64 | 1,4-Eicosadiene | C20H38 | 278.50 | Alkene | 4.05 |

| 17 | 17.74 | 3-Eicosyne | C20H38 | 278.50 | Alkyne | 0.15 |

| 18 | 17.84 | 2,4-Hexadiyne, 1,3,3-trimethyl-2-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexene | C15H26O | 222.37 | Terpenoid | 0.21 |

| 19 | 18.05 | 1,5-Cyclodecadiene, (E, Z)- | C10H16 | 136.23 | Alkene | 1.10 |

| 20 | 18.24 | 1-(1-Methylene-2-propenyl)-cyclopentanol | C9H14O | 138.24 | Alcohol | 0.08 |

| 21 | 18.33 | Octadecanoic acid | C18H36O2 | 284.50 | Fatty acid | 0.13 |

| 22 | 18.71 | Caryophyllene oxide | C15H24O | 220.35 | Terpenoid | 0.25 |

| 23 | 19.76 | 1-Pentadecyne | C15H28 | 208.38 | Alkyne | 0.36 |

| 24 | 19.89 | Furan-2-carboxylic acid | C5H4O3 | 112.08 | Furoic acid | 0.63 |

| 25 | 20.75 | 6-Methyloctahydrocoumarin | C10H16O2 | 168.23 | Coumarin | 0.27 |

| 26 | 21.12 | 7,11-Dimethyl-3-methylene-1,6Z,10-dodecatriene | C15H26 | 206.37 | Alkene | 0.42 |

| 27 | 21.41 | (E,E)-7,11,15-Trimethyl-3-methylene-hexadeca-1,6,10,14-tetraene | C20H32 | 272.46 | Alkene | 2.92 |

| 28 | 21.49 | 2-Methyl-3-(3-methyl-but-2-enyl)-2-(4-methyl-pent-3-enyl)-oxetane | C15H26O | 222.37 | Terpenoid | 0.31 |

| 29 | 22.14 |

|

C15H26O | 222.37 | Alcohol | 8.24 |

| 30 | 22.35 | 1-Naphthalenecarboxylic acid | C11H8O2 | 172.18 | Napthoic acid | 4.23 |

| 31 | 22.47 | Benzoic acid, 2,5-dimethyl- | C9H10O2 | 150.17 | Benzoic acid | 0.36 |

| 32 | 22.54 | 3-Cyclohexene-1-methanol, alpha, alpha,4-trimethyl-, 1-acetate | C12H20O2 | 196.29 | Terpenoid | 1.72 |

| 33 | 22.71 | 1,3,3-Trimethyl-2-(hydroxymethyl)-6-hydroxy-1-cyclohexene | C15H26O2 | 170.25 | Alcohol | 0.41 |

| 34 | 22.78 | Z-3-Hexadecen-7-yne | C16H28 | 220.39 | Alkyne | 0.16 |

| 35 | 22.88 | (Z, Z)-α-Farnesene | C15H24 | 204.35 | Terpenoid | 1.54 |

| 36 | 23.05 | 1-Methylene-2b-hydroxymethyl-3,3-dimethyl-4b-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-cyclohexane | C15H26O | 222.37 | Cyclohexane | 0.34 |

| 37 | 23.74 | 4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclohexane carboxaldehyde | C8H14O2 | 142.20 | Aldehyde | 21.12 |

| 38 | 23.89 | 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid | C8H6O4 | 166.13 | Pthalic acid | 0.88 |

| 39 | 25.19 | Geranyllinalool | C20H34O | 290.48 | Terpenoid | 7.51 |

| 40 | 25.89 | ar-Turmerone | C15H20O | 216.32 | Terpenoid | 19.68 |

| 41 | 26.09 | 1H-3a,7-Methanoazulene, octahydro-1,4,9,9-tetramethyl- | C15H26 | 206.37 | Terpenoid | 0.81 |

| 42 | 26.52 | N-hydroxy-N-phenylfuran-2-carboxamide | C11H9NO3 | 203.19 | Amide | 0.51 |

| 43 | 26.86 | Germacra-1(10),4,11(13)-trien-12-al | C15H22O | 218.33 | Terpenoid | 0.23 |

| 44 | 27.71 | Squalene | C30H50 | 410.70 | Terpenoid | 3.08 |

| 45 | 28.11 | 2,5-Octadiene, 3,4,5,6-tetramethyl- | C12H22 | 166.30 | Alkene | 0.35 |

| 46 | 28.25 | 3β-Acetoxy-5α-pregnan-20-one | C23H36O3 | 360.50 | Steroid ester | 0.47 |

| 47 | 28.33 | 5-Isopropyl-6-methyl-hepta-3,5-dien-2-ol | C11H20O | 168.28 | Alcohol | 0.51 |

| 48 | 28.53 | A-Neooleana-3(5),12-diene | C30H48 | 408.70 | Terpenoid | 0.25 |

| 49 | 28.79 | Cholesta-6,22,24-triene, 4,4-dimethyl- | C29H46 | 394.70 | Steroid | 0.77 |

| 50 | 29.52 | Stigmastan-3,5-diene | C29H48 | 396.70 | Phenanthrene | 0.78 |

| 51 | 29.74 | Lanosterol | C30H50O | 426.70 | Terpenoid | 4.10 |

| 52 | 30.13 | Stigmasteryl tosylate | C36H54O3S | 566.88 | Phytosterol | 0.64 |

| 53 | 30.33 | 9,19-cyclo-9.β-lanost-24-en-3.β-ol, acetate | C32H52O2 | 468.80 | Ester | 0.26 |

| 54 | 30.50 | 3,4-2H-Coumarin,4,4,5,6,8 pentamethyl- | C14H18O2 | 218.29 | Coumarin | 0.50 |

| 55 | 30.63 | Stigmastan-3,5,22-trien | C29H46 | 394.70 | Phenanthrene | 0.73 |

| 56 | 30.98 | 2-Ethylacridine | C15H13N | 207.27 | Acridine | 0.27 |

| 57 | 31.21 | Benzo[h]quinoline, 2,4-dimethyl- | C15H13N | 207.27 | Quinoline | 0.09 |

| 58 | 31.57 | Thiocarbamic acid, N, N-dimethyl, S-1,3-diphenyl-2-butenyl ester | C19H21NOS | 311.40 | Carbamic acid ester | 0.35 |

| 59 | 31.75 | 9,19-Cycloergost-24(28)-en-3-ol | C29H48O | 412.70 | Steroid | 0.23 |

| 60 | 32.34 | Vitamin E | C29H50O2 | 430.70 | Lipophilic Vitamin | 0.55 |

| 61 | 32.43 | Cyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione | C6H4O2 | 108.10 | Quinone | 0.64 |

| 62 | 33.32 | Androstan-1-one, (5α)- | C19H30O2 | 274.40 | Steroid | 0.30 |

| 63 | 34.81 | Stigmasta-5,22-dien-3. beta-ol, acetate | C31H50O2 | 454.70 | Phenanthrene | 0.50 |

| 64 | 36.96 | Olean-12-ene | C3H48O2 | 440.70 | Terpenoid | 1.09 |

| 65 | 37.69 | 3-Hydroxydiphenylamine | C12H11NO | 185.22 | Aromatic amine | 1.01 |

Further identified sterol derivatives; squalene, cholesta-6,22,24-triene,4,4-di, stigmastan-6,22-dien, 3,5-, have antioxidant, antitumor activity and cytotoxic activity (Huang et al., 2009). Biological activities described for identified phytoconstituents show that it may be one of the best sources available for the development of natural products formulations.

3.2 Biological activities

3.2.1 Antioxidant potential estimation of fresh leaves of A. jacquemontii

The antioxidant potential of fresh leaves of A. jacquemontii was determined, through antioxidant enzymes activity and TAC (Table 3). This activity was done to authenticate our selection of the plant with good antioxidant potential, so that it may be further investigated as a source of functional food components. Plants with good activity in fresh form may also have better activities in dried form (Kozłowska et al., 2021). However, the dried plant extracts were frequently investigated by researchers for bioactive phytochemicals and their biological effects. Moreover, plants having good antioxidant enzyme activities have good health-promoting effects (Khalid Rai et al., 2017). From the finding of good TAC of fresh sample ranks our selection of plant as a food source for good health, and a potential candidate for detailed investigations. So, it was obvious to proceed with the present research by extracting dried plants in bulk, with an organic solvent for more detailed investigations through various phytochemical and biological evaluations. All these experiments were designed in search of a potential source for functional foods and nutraceutical constituents. Organic solvents (especially methanol) have the capacity to extract various phytochemicals of biological importance and also increase the yield of bioactive secondary metabolites (Truong et al., 2019), so, further research for extraction with methanol is designed and also the extraction with a non-polar solvent is considered. Then, the antioxidant activities of dried extract were performed to reveal the antioxidant potential of the plant and its relation with phytochemical constituents.

| Sr. No. | Phytochemical tests | Mean | Standard deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | POD (Units/g f. wt.) | 399.70 | 17.09 |

| 2 | CAT (Units/g f. wt.) | 250.00 | 14.14 |

| 3 | APX (Units/g f. wt.) | 320.00 | 8.28 |

| 4 | SOD (Units/g f. wt) | 59.00 | 2.75 |

| 5 | TAC (mmol TE/g f. wt) | 1.03 | 0.19 |

POD = peroxidase, CAT = catalase, APX = ascorbate peroxidase, SOD = superoxide dismutase, TAC = total antioxidant capacity.

3.2.2 Antioxidant activities of dried plant extract

Phenolic and flavonoid compounds are ascribed as “high-level natural antioxidants” and are responsible for the antioxidant properties of food plants and also increase their medicinal value by contributing to other biological activities (Kalaivani and Mathew 2010). As we found a high concentration of phenolic and flavonoid contents in A. jacquemontii, the antioxidant potential of MEAJ and HEAJ extracts was evaluated through four diverse assays, which include two radical scavenging (DPPH and ABTS), and two reducing capacity methods (FRAP and CUPRAC). The results were expressed as mg Trolox equivalents per gram of the dried extract along with standard deviation (mg TE/g of dry extract) and listed in Table 4. Radical scavenging activities revealed that MEAJ extract has high antioxidant potential (DPPH, 154.04 ± 2.47 and ABTS, 122.36 ± 0.80 mg Trolox/g of dry extract) as compared to HEAJ extract (DPPH, 97.06 ± 1.61 and ABTS, 74.37 ± 0.49 mg Trolox/g of dry extract). Further, a similar pattern of activity was observed for reducing power as MEAJ extract showed greater antioxidant activity (FRAP, 453.18 ± 5.9 and CUPRAC, 1389.97 ± 5.32 mg Trolox/g of dry extract) when compared with HEAJ (FRAP, 217.8 ± 3.10 and CUPRAC, 610.49 ± 4.91 mg Trolox/g of dry fraction) of A. jacquemontii. Moreover, the total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of MEAJ was also higher (4.36 ± 1.12 mmol TE/g dry extract) as compared to HEAJ (1.10 ± 0.5 mmol TE/g dry fraction) which may due to the presence of higher phenolic and flavonoid contents in MEAJ. These findings also supported the previous study in which strong antioxidant activity was observed from ethyl acetate extract of leaves of A. jacquemontii. They found that the extract showed 69.470 % inhibition of DPPH compared with the standard drug antioxidant (ascorbic acid; 78.90 %) at the same concentration (1 mg/mL) (Awan et al., 2021). Previous research on the leaves extracts of a closely related species A. nilotica also claimed that the high antioxidant potential of plant leaves was due to the presence of a high concentration of phenolic and flavonoid contents in addition to saponins and terpenoids (Saratale et al., 2019). The presence of a high concentration of terpenoids, along with other bioactive phytochemicals in the HEAJ fraction reflected the antioxidant activity of that sample (Mohandas and Kumaraswamy 2018). According to our findings, A. jacquemontii has a lot of potential as an antioxidant agent for the development of new functional foods and nutraceuticals.

| Sample codes (1 mg/mL) | DPPH (mg TE/g of the dried sample) | ABTS (mg TE/g of the dried sample) | FRAP (mg TE/g of the dried sample) | CUPRAC (mg TE/g of the dried sample) | TAC (mmol TE/g of the dried sample) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEAJ | 154.04 ± 2.47 a | 122.36 ± 0.80 a | 453.18 ± 5.9 a | 1389.97 ± 5.32 a | 4.36 ± 1.12 a |

| HEAJ | 97.06 ± 1.61b | 74.37 ± 0.49b | 217.80 ± 3.10b | 610.49 ± 4.91b | 1.10 ± 0.50b |

MEAJ = Methanolic extract of A. jacquemontii, HEAJ = n-Hexane extract of A. jaquemontii, TAC = Total antioxidant capacity, TE = Equivalent of Trolox. Different letters in same column indicate significant differences in the tested extracts (p < 0.05).

3.2.3 Tyrosinase inhibition and thrombolytic activity

Various Acacia species have previously demonstrated effective tyrosinase inhibition (Casas et al., 2020, Zheleva-Dimitrova et al., 2021), thus we investigated A. jacquemontii for tyrosinase inhibition activity. The MEAJ extract showed 71.69 % inhibition against tyrosinase, which was comparable to the standard (kojic acid 83 %), While HEAJ (n-hexane fraction) exhibited a 57.83 % inhibition (Table 5). Tyrosinase inhibition is found to be closely connected to plant flavonoids content and plant materials containing more flavonoids contents show stronger tyrosinase inhibition (Shimizu et al., 2000). So, in the case of A. jacquemontii, the MEAJ extract contained more flavonoid contents, which may be responsible for better tyrosinase inhibition. As the A. jacquemontii extracts demonstrated a very high reducing power so it may also affect the chelating activity of copper at the active site of the enzyme, which prevents the binding of copper ions to oxygen and leads to the irreversible deactivation of the tyrosinase enzyme (Ortonne and Ballotti 2000, Yaar and Gilchrest 2004). Our results were also supported by previous findings from a similar specie A. nilotica that was found to be a potent inhibitor of tyrosinase enzyme (Opperman et al., 2020), and other investigations also show that methanolic extract of A. nilotica was more effective tyrosinase inhibitor compared with other tested species of Acacia (Zheleva-Dimitrova et al., 2021). So, our study may be helpful for designing herbal products and pharmaceuticals, in order to develop skin-lightening agents.

| Sample name (1 mg/mL) | % Inhibition of tyrosinase |

|---|---|

| MEAJ | 71.69 % |

| HEAJ | 57.83 % |

| Kojic acid | 83 % |

MEAJ = Methanolic extract of A. jacquemontii, HEAJ = n-Hexane extract of A. jaquemontii.

Now a day, another big problem is a failure in hemostasis, which causes thrombus (blood clot) formation which may cause a partial or complete blockage in small vessels of the circulatory system. This vascular blockage may lead to catastrophic thrombotic illnesses such as acute myocardial or cerebral infarction, which can ultimately become the cause of death (Keziah and Devi 2018). To dissolve thrombus, thrombolytic drugs such as streptokinase, alteplase, anistreplase, urokinase and tissue plasminogen activator are routinely used. The majority of them are synthetic and have adverse effects (Li et al., 2020). Therefore, there is a crucial need to look into indigenous sources for new, safer and more effective therapies that lead to good thrombolytic action. In this investigation, we used various subject’s samples A-E for thrombolytic activity (Table 6) and found that MEAJ extract has shown significant activity ranging from 56.22 ± 1.01 to 57.15 ± 1.41 % which is higher than the HEAJ fraction (41.8 ± 1.21 to 43.1 ± 0.69 %), Whereas streptokinase showed the thrombolytic activity varying from 82.5 to 84.1 %. This activity could be attributed to the many phytochemicals present in these extracts. According to the above findings, A. jacquemontii may be used as a source of natural thrombolytic medicines and herbal products can be formulated from it.

| Sample codes (1 mg/mL) | Subject A | Subject B | Subject C | Subject D | Subject E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEAJ | 56.41 ± 0.75b | 57.15 ± 1.41b | 56.22 ± 1.01b | 56.61 ± 1.71b | 56.9 ± 2.10b |

| HEAJ | 42.18 ± 0.98c | 43.1 ± 0.69c | 42.51 ± 0.78c | 41.8 ± 1.21c | 42.63 ± 1.85c |

| Streptokinase | 82.5 ± 0.45 a | 84.14 ± 0.95 a | 83.43 ± 0.89 a | 82.44 ± 1.15 a | 83.1 ± 2.80 a |

MEAJ = Methanolic extract of A. jacquemontii, HEAJ = n-Hexane extract of A. jaquemontii. Different letters in same column indicate significant differences in the tested extracts (p < 0.05).

3.2.4 Antibacterial activity

The bacterial strains employed in this study are frequently drug-resistant or isolated from clinical specimens, implying that they are responsible for human infections (Mukerji et al., 2017). Both extracts of A. jacquemontii showed antibacterial activity in a concentration-dependent manner and we observed the antibacterial activity of MEAJ (methanolic extract) was higher, as compared to the HEAJ (hexane fraction) as presented in Table 7. Our findings were in line with the previously conducted study on a similar species (Jabaka et al., 2019). Who reported that more polar fractions of A. nilotica had the highest inhibition against Bacillus subtilis, Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus epidermidis). Our analysis also showed that MEAJ had the strongest inhibitory effect on B. subtilis (MIC; 0.5 mg/mL) whereas MIC of the standard drug was 0.5 µg/mL. The results of antibacterial activity were supported by the previous study in which the ethanolic extract of the stem bark of A. jacquemontii was found to be active against tested bacteria. They reported that the extract of this plant was highly active against Bacillus species. The zone of inhibition for Bacillus cereus was 15.4 ± 0.02 mm, and Bacillus pumilus showed 16 ± 0.01 mm (Choudhary et al., 2009). Our results were also consistent with another study conducted on Acacia species that found the highest zone of inhibition against B. Subtilis (Thambiraj and Paulsamy 2015). The antibacterial activity of HEAJ may be due to the presence of terpenoids in high concentrations. Moreover, phytochemicals like terpenoids, unsaturated and saturated fatty acids, and coumarins also contribute to the activity of n-hexane fraction (Adhoni et al., 2016) and similar bioactive metabolites were also identified from HEAJ extract, in our study by GC–MS technique (Table 2). Moreover, the higher antibacterial activity of the methanolic extract was correlated with the possible synergistic effect of phenolic and flavonoid contents and we found a good quantity of them in our experiment as shown in Table 1 (Neto et al., 2017). So, the methanolic extract if further investigated, may provide natural antibacterial ingredients for nutraceutical products and the pharmaceutical industry.

| Name of bacterial strains | Minimum inhibitory concentration (µg/mL) of standard (co amoxiclav) | Minimum inhibitory concentration (mg/mL) of methanolic extract (MEAJ) | Minimum inhibitory concentration (mg/mL) of n-hexane fraction (HEAJ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacillus subtilis | 5.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| Micrococcus luteus | 6.00 | 0.75 | 2.00 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 6.00 | 0.75 | 1.50 |

| Bacillus pumilus | 5.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 8.50 | 0.75 | 1.00 |

| Escherichia coli | 8.00 | 1.00 | 1.50 |

| Bordetella bronchiseptica | 12.50 | 1.50 | 3.00 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 12.50 | 2.00 | 3.00 |

3.2.5 Antiviral activity

The antiviral study of the methanolic and n-hexane extracts of A. jacquemontii was tested against four different viruses and significant results were obtained against all the tested viruses as shown in Table 8, and the titer score is directly proportional to the number of viral particles, so presenting efficacy of extract concerned viral growth (Musaddiq et al., 2020). In the present study, both extracts MEAJ and HEAJ displayed good antiviral activity against all four viruses, including avian influenza virus (AIV) H9N2, infectious bronchitis virus (IBV), Newcastle disease virus (NDV), and infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV), and very less viral titer growth of virus was found as presented in Table 9. The HEAJ extract shows weaker antiviral activity with a viral titer 12 (IBV virus) whereas MEAJ expressed good activity with a viral titer 08 (IBV virus). These findings were also consistent with prior research, which found that the hydroalcoholic extract of Acacia nilotica (Linn) leaves had good antiviral action against Peste des petits ruminant’s virus (PPRV), a single-stranded RNA virus with a negative sense (Ahmad et al., 2014). Another deadly virus is IBDV, due to the non-availability of antiviral brands in the market. However, several researchers have found evidence of the use of medicinal herbs to combat the fatal IBDV virus (Pant et al., 2012). IBDV is also called HIV for poultry (HIV causes AIDS in humans), as it causes immunosuppression (Fauci 2003). The recent global pandemic of COVID-19, which was triggered by SARS-CoV-2, has been devastating to communities all over the world. It is critical to investigate all possibilities to develop a much-needed therapeutic medication for SARS-CoV-2, as there are no specific medications to treat COVID-19 in the current pandemic (Stasi et al., 2020). So the antiviral study against IBV virus, which has similar characteristics to the coronavirus (Wang et al., 2020), may also be helpful to develop antiviral agents. According to our results, A. jacquemontii has a high potential as an antiviral agent or could pave the path for the development of novel antiviral compounds from this plant to combat viral infections.

| Sample code (1 mg/mL) | Avian Influenza virus (AIV H9N2) | Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) | Newcastle disease virus (NDV) | Infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEAJ | 00 | 08 | 00 | 00 |

| HEAJ | 04 | 12 | 00 | 08 |

| Control | 1024 | 2048 | 1024 | 2048 |

HA titer score 0–8 = highly strong against virus, 16–32 = strong antiviral, 64–128 = moderate effect, 256–2048 = not active (Musaddiq et al., 2020).

| Sr. no. | Compound name | binding energy kcal/mol | Interaction of ligands at binding site of enzyme | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonding type | Binding amino acids | |||

| 1 | 1-Naphthalenecarboxylic acid | −7.8 | Van der Waals | GLU 232, TYR 462, LEU 460, ILE 128, GLN 236, GLY 461, 116, VAL 126, ARG 114, 118, TRP 117. |

| Alkyl | LEU 229, PRO 115, LYS 233. | |||

| 2 | Geranyllinalool | −6.0 | Van der Waals | GLU 237, GLY 116, 107, GLN 236, LEU 158, TRP 117, HIS 108, ARG 230, PRO 242, THR 112. |

| Alkyl | ARG 118, LYS 233, PRO 115. | |||

| 3 | Squalene | −6.7 | Van der Waals | GLN 437, THR 69, 448, 98, ARG 230, 114, ASN 439, ASP 641, HIS 100, GLU 451, VAL 68, CYS 99, 101, SER 106. |

| Alkyl | PRO 446, 445, 115, LYS 233, VAL 447, LEU 229, TYR 226. | |||

| 4 | Lanosterol | −7.3 | Van der Waals | LEU 45, PRO 47, 43, 51, GLU 34, ASP 44, GLN 29, CYS 41, 42, GLY 52, ARG 55, MET 40, THR 32. |

| Alkyl | ALA 35. | |||

| 5 | 3-Cyclohexene-1-methanol, alpha, alpha,4-trimethyl-, 1-acetate | −6.0 | Van der Waals | ILE 466, GLU 413, THR 463, 455, TYR 464, ALA 409, ASP 412, 458. |

| Alkyl | PRO 457, ARG 416. | |||

| 6 | 2,6,10-Dodecatrien-1-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl- | −6.3 | Van der Waals | TYR 462, ILE 128, GLY 116, 461, TRP 117, LEU 460, VAL 126, GLN 236, GLU 237. |

| Carbon hydrogen bond | GLU 232. | |||

| Alkyl | PRO 115, 242, LYS 233, ARG 118. | |||

| 7 | (E,E)-7,11,15-Trimethyl-3-methylene-hexadeca-1,6,10,14-tetraene | −6.5 | Van der Waals | CYS 99, ARG 114, 230, SER 106, GLY 107, TYR 226, THR 98, 112, GLU 451, VAL 447. |

| Alkyl | HIS 100, PRO 446, 445, 115, LYS 233, LEU 229. | |||

| 8 | ar-Tumerone | −6.4 | Van der Waals | CYS 113, 99, THR 112, PRO 115, 446, TYR 226, GLU 451, HIS 100, VAL 447, GLY 107. |

| Conventional hydrogen bonding | ARG 114. | |||

| Unfavorable acceptor–acceptor | SER 106. | |||

| Pi-cation | SER 16. | |||

| Alkyl | LYS 233, PRO 445. | |||

| 9 | 4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclohexane carboxaldehyde | −5.9 | Van der Waals | ARG 130, VAL 129, GLU 140, LEU 246, SER 245, PE 244, 144, HIS 143. |

| Conventional hydrogen bonding | ARG 131. | |||

| Alkyl | PRO 247, LEU 136. | |||

| 10 | 1,4-Eicosadiene | −4.2 | Van der Waals | TRP 468, PHE 406, TYR 248, GLN 468, AGN 250, ASN 132. |

| Alkyl | VAL 333, ALA 252, ILE 466, PRO 469, 330. | |||

| 11 | Kojic acid | −5.9 | Van der Waals | ARG 374, LEU 382, ASN 378, HIS 377, 215, 404, 192, PHE 400, GLY 388, 389, GLN 390, SER 394. |

| Conventional hydrogen bonding | HIS 381. | |||

| Unfavourable acceptor–acceptor | TYR 362. | |||

| Pi-donor hydrogen bond | THR 391. | |||

| Pi-pi stacked | HIS 381. | |||

3.3 In silico studies

3.3.1 Molecular docking studies for tyrosinase inhibition

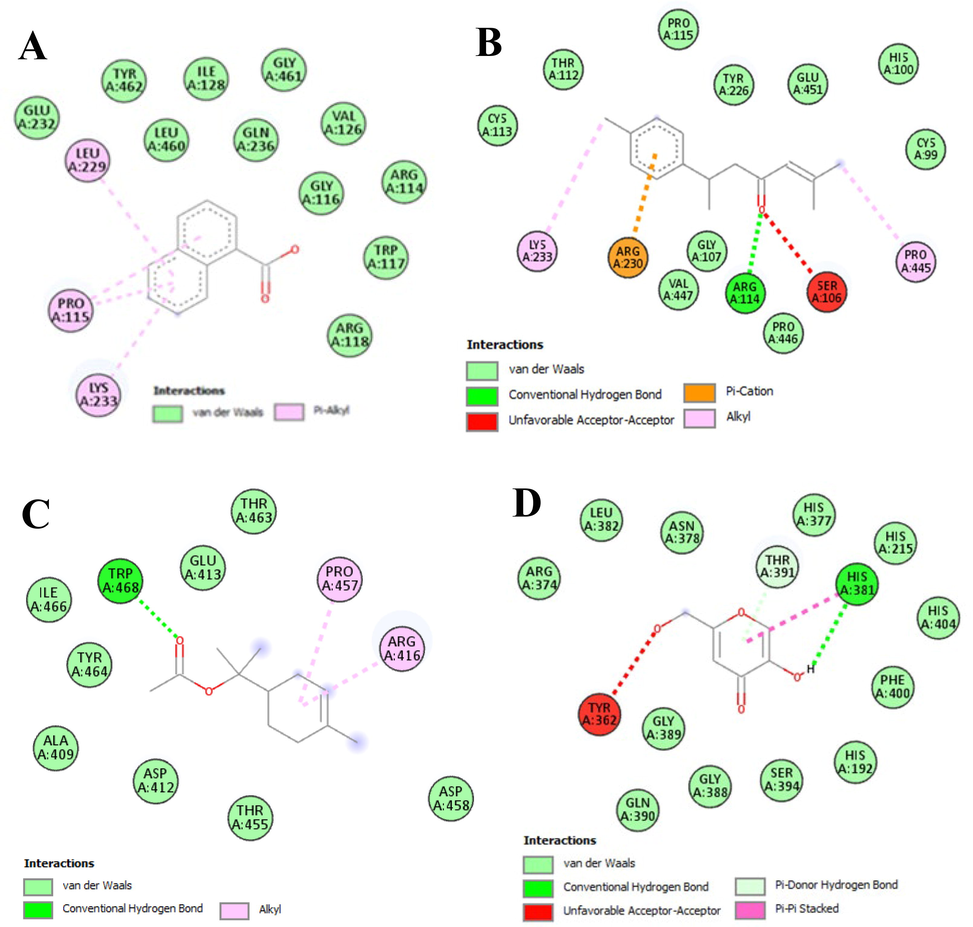

Molecular docking is the computer-aided procedure describing the interaction of ligand and receptor molecules that interact together in 3-dimensional spaces. It is a key technique in computer-aided drug designing and structural biology (Varela et al., 2020). Compounds are chosen as ligands were eight bioactive moieties from the library of GC–MS (Ladokun et al., 2018). The selection criteria were that the compounds should have a maximum peak area and belong to a major class of bioactive phytochemicals, and vitamin E was also selected for its frequent use in cosmetic formulations and skincare products. Kojic acid was selected as a standard ligand to compare the activities of phytochemicals for tyrosinase inhibition. The binding energies (kcal/mol) score of the ligands was obtained and given as, 1-naphthalenecarboxylic acid (-7.8), lanosterol (-7.3), squalene (-6.7), (E,E)-7,11,15-Trimethyl-3-methylene-hexadeca-1,6,10,14-tetraene (-6.5), ar-turmerone (-6.4), 2,6,10-Dodecatrien-1-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl- (-6.3), geranyllinalool (-6.0), 3-Cyclohexene-1-methanol, alpha,alpha,4-trimethyl-, 1-acetate (-6.0). All these docked compounds had higher binding affinities with tyrosinase active sites as they revealed lower binding energies compared with kojic acid (-5.9 kcal/mol). Herein, the binding energy of 4-(hydroxymethyl) cyclohexane carboxaldehyde (-5.9 kcal/mol) was equal to the binding energy of kojic acid, and the only compound which showed less binding energy than kojic acid was 1,4-Eicosadiene (-4.2 kcal/mol). The higher negative value of binding energy from the docking score (lower binding energy) indicates a higher binding affinity of the ligand with the tyrosinase active site. Further, the binding efficacy of the ligand may be explained by the type of bonding involved in the interaction of ligand molecules with amino acids of the target receptor (Ashraf et al., 2021). Among various types of bonds, van der Waals and alkyl bonding had been shown by all ligands. Conventional hydrogen bonding was present among the amino acids of the tyrosinase active site and two compounds (ar-turmerone, and 4-(hydroxymethyl) cyclohexane carboxaldehyde), and kojic acid, while the carbon-hydrogen bond was formed by 2,6,10-Dodecatrien-1-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl- with the GLU 232 residue of tyrosinase active site. Unfavorable acceptor–acceptor interaction was shown by ar-tumerone and kojic acid with active site residues. Various π-π interactions were depicted by ar-turmerone, and standard ligand (kojic acid), and turmerone. This data revealed that the tyrosinase inhibitory potential of HEAJ extract of A. jacquemontii may be due to the presence of the docked phytochemical ligands. Results of interactions of ligands from this docking study for tyrosinase inhibition were given below in Table 9, which included binding energies of ligands and details of interacting amino acids of the active site. Diagrammatic presentations, showing the ligand-receptor interaction are given in Fig. 2. So, comparing the significant results of our experiment on HEAJ extract (HEAJ, 57.83 % while kojic acid, 83 % inhibition) with the results of our computational study, it was concluded that docked compounds may be responsible for tyrosinase inhibition because they were contributing the major portion of extract. So HEAJ extract may also be considered for the isolation of compounds with tyrosinase-inhibiting effects in future studies to develop natural products for skin, pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical formulations.

- Diagrammatic presentation (two-dimensional) of interaction between selected ligands and amino acid residues of tyrosinase enzyme with; A = 1-naphthalenecarboxylic acid, B = ar-turmerone, C = 3-Cyclohexene-1-methanol, alpha, alpha, 4-trimethyl-, 1-acetate, D = kojic acid (used as a standard).

3.3.2 ADME prediction studies

Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) were predicted by different parameters obtained by using online predictors and presented in Table 10. The six major compounds were evaluated for their pharmacokinetic parameters and all the compounds showed high absorption through the gastrointestinal tract. The studied compounds also show good permeation parameters of skin because the more negative values of logp, the less permeable will be the molecule for the skin (Daina et al., 2017). Geranyllinalool showed the properties as a substrate for P‐glycoprotein, which is a mechanism of efflux used by cancer cells leading to drug resistance, while other compounds were not acting as substrates in this prediction study. Lanosterol showed the highest volume of distribution (0.66 log L/kg), and 4-(hydroxymethyl) cyclohexane carboxaldehyde depicted the lowest volume of distribution (-0.016 log L/kg). All the compounds were predicted to cross the blood–brain barrier except geranullinalool, and lanosterol.

| Parameters | 4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclohexane carboxaldehyde | 1-Naphthalenecarboxylic acid | 2,6,10-Dodecatrien-1-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl- | ar-Turmerone | Geranyllinalool | Lanosterol | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility class | High | High | High | High | High | High | |

| Log Kp (Skin permeation) cm/s | Very soluble | Soluble | Moderately soluble | Moderately soluble | Poorly soluble | Poorly soluble | |

| Pgp substrate2 | −6.30 | −5.15 | −3.81 | −4.79 | −3.33 | −2.58 | |

| Distribution | BBB3 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| VDss4 (human) log L/kg | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | |

| Metabolism | CYP1A2 inhibitor | −0.016 | −1.993 | 0.36 | 0.621 | 0.476 | 0.66 |

| CYP2C19 inhibitor | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| CYP2C9 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| CYP2D6 inhibitor | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| CYP3A4 inhibitor | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Excretion | Total Clearance (log mL/min/kg) | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Renal OCT2 substrate | 0.444 | 0.660 | 1.754 | 0.295 | 1.868 | 0.403 | |

1 gastrointestinal absorbance; 2P-glycoprotein; 3 blood brain barriers; 4 vol of distribution.

Furthermore, the employed tool also predicted the interaction of compounds with five major cytochromes (CYP) isoforms, which play a crucial role in the metabolism and excretion of the majority of drugs available in the market and it was predicted that the compounds do not inhibit the CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP3A4 enzymes. CYP1A2 and CYP2C9 were inhibited by 2,6,10-Dodecatrien-1-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl- and geranyllinalool. So 2,6,10-Dodecatrien-1-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl- and geranyllinalool were the compounds which may observe the first-pass metabolism and can also interact with other drugs (Chen et al., 2020). Total clearance of the compounds was tested including hepatic and renal clearance which predicted that all the tested compounds showed inadequate values of total clearance. According to another parameter of excretion, it was found that the compounds were non-substrate of OCT2 (Organic Cat‐ ion Transporter 2), and the substrates of this transporter may cause adverse interactions with the inhibitors of OCT2 (Hassan et al., 2021).

3.3.3 In silico toxicity prediction study

In silico toxicity was evaluated by using the parameters of organ toxicity and the median lethal dose was also predicted along with the toxicity class of the compounds and it was found that 1-naphthalenecarboxylic acid is hepatotoxic (active toxicity prediction) and belongs to class-4 in toxicity with a median lethal dose of 390 mg/kg, while lanosterol predicted to be immunotoxic. All the other compounds were found to be safe with inactive prediction, however, their probability score varied which suggested their comparative inactivity for organ toxicity. The detail of the prediction scores is given in Table 11.

| Organ toxicity with a toxicity prediction score | 4-(hydroxymethyl)cyclohexane carboxaldehyde (LD50: 5100 mg/kg, class; 5) | 1-Naphthalenecarboxylic acid (LD50: 390 mg/kg, class; 4) | 2,6,10-Dodecatrien-1-ol, 3,7,11-trimethyl-(LD50: 5000 mg/kg, class; 5) | ar-Turmerone (LD50: 2000 mg/kg, class; 4) | Geranyllinalool (LD50: 5000 mg/kg, class; 5) | Lanosterol (LD50: 2000 mg/kg, class; 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hepatotoxicity | 0.77 | 0.58* | 0.79 | 0.59 | 0.81 | 0.82 |

| Carcinogenicity | 0.60 | 0.63 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.65 | 0.58 |

| Immunotoxicity | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.55* |

| Mutagenicity | 0.84 | 0.61 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.94 |

| Cytotoxicity | 0.89 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.96 |

* Predicted as “active for toxicity”, Class 4; harmful if swallowed (300 mg/kg < LD50 ≤ 2000 mg/kg), Class 5; may be harmful if swallowed (2000 mg/kg < LD50 ≤ 5000 mg/kg).

4 Conclusions

The purpose of the current research was to determine the phytochemical composition and biological activities of A. jacquemontii, a wild plant providing food and medicinal components. Total bioactive contents were revealed in higher quantities from methanolic extracts (MEAJ), as compared to n-hexane extract (HEAJ). GC–MS analysis showed the presence of a variety of phytochemicals of biological significance, with antioxidant and antibacterial characteristics. Further to authenticate its potential for use in natural and pharmaceutical products a comprehensive biological screening was done through various antioxidant assays, which revealed the strong antioxidant potential of the plant. Tyrosinase enzyme inhibition activity showed good results, especially from MEAJ. Moreover, the plant extracts showed good results for thrombolytic activity which is one of the most needed therapies now a day, as thrombotic events lead to impaired quality of life and death. Along with these activities, the methanolic extract also showed good results for both antiviral and antibacterial activities, and the antiviral potential of the plant also encourages further investigations of the plant to combat recent viral ailments. Antioxidants, antityrosinase, and antibacterial and antiviral effects encourage to development of natural products related to skin disorders. These findings will help in designing natural bioactive plant products, and functional food supplements for the prevention of various ailments however further research may lead to the discovery and development of novel drugs for the pharmaceutical industries.

Funding

This work was supported by the Special Fund for Development of Strategic Emerging Industries in Shenzhen (JCYJ20190808145613154, KQJSCX20180328100801771).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Maqsood Ahmed: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Kashif-ur-Rehman Khan: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Saeed Ahmad: Supervision, Project administration. Hanan Y. Aati: Resources. Asma E. Sherif: Resources. Mada F. Ashkan: Software, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Jehan Alrahimi: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Ebtihal Abdullah Motwali: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Muhammad Imran Tousif: Validation, Formal analysis. Mohsin Abbas Khan: Resources. Musaddique Hussain: Visualization. Muhammad Umair: Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Funding acquisition. Bilal Ahmad Ghalloo: Methodology. Sameh A. Korma: Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the Chairperson Department of Pharmaceutical Chemistry, the Islamia University of Bahawalpur, for his technical support, suggestions, and laboratory facilities, and we acknowledge the facilitations from, the Development of Strategic Emerging Industries in Shenzhen.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Molecular design and docking analysis of the inhibitory activities of some α_substituted acetamido-N-benzylacetamide as anticonvulsant agents. SN Appl. Sci.. 2019;1:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- GC-MS analysis and preliminary antimicrobial activity of Albizia adianthifolia (Schumach) and Pterocarpus angolensis (DC) Medicines. 2016;3:3.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical analysis and antimicrobial activity of Chorella vulgaris isolated from Unkal Lake. J. Coastal Life Med.. 2016;4:368-373.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Exploration of the in vitro cytotoxic and antiviral activities of different medicinal plants against infectious bursal disease (IBD) virus. Open Life Sci.. 2014;9:531-542.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vitro bioactivity of extracts from seeds of Cassia absus L. growing in Pakistan. J. Herbal Med.. 2019;16:100258

- [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M., K.-u.-R. Khan, S. Ahmad, et al., 2022. Comprehensive Phytochemical Profiling, Biological activities, and Molecular Docking Studies of Pleurospermum candollei: An Insight into Potential for Natural Products Development. molecules. 27, 4113

- Phytochemicals: extraction, isolation, and identification of bioactive compounds from plant extracts. Plants. 2017;6:42.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical diversity and pharmacological properties of genus Acacia. Asian J. Appl. Sci.. 2020;13:40-59.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of bioactive composites and antiviral activity of Iresine herbstii extracts against Newcastle disease virus in ovo. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.. 2020;27:335-340.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-inflammatory property of n-hexadecanoic acid: structural evidence and kinetic assessment. Chem. Biol. Drug Des.. 2012;80:434-439.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometry profiling in methanolic and ethyl-acetate root and stem extract of Corbichonia decumbens (Forssk.) Exell from Thar Desert of Rajasthan, India. Pharmacogn. Res.. 2017;9:S48.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antipyretic, analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities of methanol extract of root bark of Acacia jacquemontii Benth (Fabaceae) in experimental animals. Trop. J. Pharm. Res.. 2016;15:1859-1863.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure-based designing and synthesis of 2-phenylchromone derivatives as potent tyrosinase inhibitors: In vitro and in silico studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2021;35:116057

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Acacia Jacquemontii Ethyl Acetate Extract Downregulated the Hyperglycemia Through Its Modulatory Effects On Endogenous Antioxidant. Environmental Science and Pollution Research: Anti-Inflammatory And Pancreatic β-Cell Regenerative Status in Alloxan Induced Diabetic Rats; 2021.

- New mechanistic insights on Justicia vahlii Roth: UPLC-Q-TOF-MS and GC–MS based metabolomics, in-vivo, in-silico toxicological, antioxidant based anti-inflammatory and enzyme inhibition evaluation. Arabian J. Chem.. 2022;15:104135

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and antimicrobial activities of novel naphtho [2, 1-b] pyran, pyrano [2, 3-d] pyrimidine and pyrano [3, 2-e][1, 2, 4] triazolo [2, 3-c]-pyrimidine derivatives. Il Farmaco.. 2001;56:965-973.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of antioxidant capacity of endemic plant Marrubium astracanicum subsp. macrodon: Identification of its phenolic contents by using HPLC-MS/MS. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2019;33:1975-1979.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enzyme inhibitory function and phytochemical profile of Inula discoidea using in vitro and in silico methods. Biophys. Chem.. 2021;277:106629

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioactive properties of Acacia dealbata flowers extracts. Waste Biomass Valoriz. 2020

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cyclocarya paliurus (Batalin) Iljinskaja: botany, Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2022;285:114912

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In silico design of novel HIV-1 NNRTIs based on combined modeling studies of dihydrofuro [3, 4-d] pyrimidines. Front. Chem.. 2020;8:164.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhary, K., M. Singh and N. Shekhawat, 2009. Ethnobotany of Acacia jacquemontii Benth.-An Uncharted Tree of Thar Desert, Rajasthan, India. Ethnobotanical leaflets. 2009, 1.

- Antibacterial Screening and Phytochemical investigation of bark extracts of Acacia jacquemontii Benth. Stamford J. Pharma. Sci.. 2009;2:21-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dahibhate, N., S. Shukla, K. J. F. i. P. Kumar, et al., 2022. A Cyclic Disulfide Diastereomer From Bioactive Fraction of Bruguiera gymnorhiza Shows Anti–Pseudomonas aeruginosa Activity. Front. Pharmacol. 13: 890790. doi: 10.3389/fphar. 2022.890790. Frontiers in pharmacology. 13

- Daina, A., O. Michielin and V. J. S. r. Zoete, 2017. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 7, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42717

- An investigation on phytochemical, antioxidant and antibacterial properties of extract from Eryngium billardieri F. Delaroche. J. Food Meas. Charact.. 2020;14:708-715.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical profiling, in vitro biological activities, and in-silico molecular docking studies of Typha domingensis. Arabian J. Chem. 2022:104133.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dilshad, R., K.-u.-R. Khan, L. Saeed, et al., 2022. Chemical Composition and Biological Evaluation of <i>Typha domingensis</i> Pers. to Ameliorate Health Pathologies: <i>In Vitro</i> and <i>In Silico</i> Approaches. BioMed Research International. 2022, 8010395. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/8010395

- Differential antioxidative responses to cadmium in roots and leaves of pea (Pisum sativum L. cv. Azad) J. Exp. Bot.. 2001;52:1101-1109.

- [Google Scholar]

- GC-MS analysis of phytocomponents in the ethanol extract of Polygonum chinense L. Pharmacogn. Res.. 2012;4:11.

- [Google Scholar]

- β-Caryophyllene: a sesquiterpene with countless biological properties. Appl. Sci.. 2019;9:5420.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extraction and identification of bioactive components in Sida cordata (Burm. f.) using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J. Food Sci. Technol.. 2017;54:3082-3091.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ghalloo, B. A., K.-u.-R. Khan, S. Ahmad, et al., 2022. Phytochemical Profiling, In Vitro Biological Activities, and In Silico Molecular Docking Studies of Dracaena reflexa. Molecules. 27, 913

- Eugenol, α-pinene and β-caryophyllene from Plectranthus barbatus essential oil as eco-friendly larvicides against malaria, dengue and Japanese encephalitis mosquito vectors. Parasitol. Res.. 2016;115:807-815.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of antioxidant enzyme activity and phenolic contents of some species of the Asteraceae family from medicanal plants. Ind. Crops Prod.. 2019;137:208-213.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of Antiviral Activity of Allium Cepa and Allium Sativum Extracts Against Newcastle Disease Virus. Alexand. J. Veterin. Scie.. 2019;61

- [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S. S. u., I. Muhammad, S. Q. Abbas, et al., 2021. Stress driven discovery of natural products from actinobacteria with anti-oxidant and cytotoxic activities including docking and admet properties. Int J Mol Sci. 22, 11432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms222111432

- Biological and pharmacological activities of squalene and related compounds: potential uses in cosmetic dermatology. Molecules. 2009;14:540-554.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial Activity of Acacia nilotica Stem-Bark Fractions against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Int. J. Biochem. Res. Rev.. 2019;1–1

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jameel, S., A. Hameed and T. M. Shah, 2021. Investigation of Distinctive Morpho-Physio and Biochemical Alterations in Desi Chickpea at Seedling Stage Under Irrigation, Heat, and Combined Stress. Frontiers in plant science. 2049. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.692745.

- Free radical scavenging activity from leaves of Acacia nilotica (L.) Wild. ex Delile, an Indian medicinal tree. Food Chem. Toxicol.. 2010;48:298-305.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Focalization of thrombosis and therapeutic perspectives: a memoir. Orient. Pharma. Experimental Med.. 2018;18:281-298.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant potential and biochemical analysis of Moringa oleifera leaves. Int. J. Agric. Biol.. 2017;19

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent developments in the chemistry of ferrocenyl secondary natural product conjugates. Coord. Chem. Rev.. 2018;366:91-108.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenolic contents and antioxidant activity of extracts of selected fresh and dried herbal materials. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci.. 2021;71:269-278.

- [Google Scholar]

- GC-MS and molecular docking studies of Hunteria umbellata methanolic extract as a potent anti-diabetic. Inf. Med. Unlocked. 2018;13:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanisms of tolerance differences in cucumber seedlings grafted on rootstocks with different tolerance to low temperature and weak light stresses. Turk. J. Bot.. 2015;39:606-614.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antithrombotic drugs—pharmacology and perspectives. Coronary Artery Disease: Therap. Drug Discov. 2020:101-131.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Strong antioxidant phenolics from Acacia nilotica: profiling by ESI-MS and qualitative–quantitative determination by LC–ESI-MS. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.. 2011;56:228-239.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bioavailability of dietary polyphenols and gut microbiota metabolism: antimicrobial properties. Biomed Res. Int.. 2015;2015

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phytochemical screening and GC-MS analysis in ethanolic leaf extracts of Ageratum conyzoides (L.) World J. Pharm. Res.. 2016;5:1019-1029.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect of Asphodelus microcarpus methanolic extracts. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2019;239:111914

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McChesney, J. D., S. K. Venkataraman and J. T. J. P. Henri, 2007. Plant natural products: back to the future or into extinction? 68, 2015-2022

- Antioxidant activities of terpenoids from Thuidium tamariscellum (C. Muell.) Bosch. and Sande-Lac. a Moss. Pharmacogn. J.. 2018;10

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Development and transmission of antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negative bacteria in animals and their public health impact. Essays Biochem.. 2017;61:23-35.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]