Translate this page into:

Phytochemistry, pharmacology and clinical applications of the traditional Chinese herb Pseudobulbus Cremastrae seu Pleiones (Shancigu): A review

⁎Corresponding author at: 300 Xueshi Rd., Hanpu Science & Technology Park, Yuelu District, Changsha 410208, PR China. wangwei402@hotmail.com (Wei Wang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Pseudobulbus Cremastrae seu Pleiones (PCsP) is a traditional Chinese herbal medicine known as “Shancigu” in China. It has the property of relieving fever, counteracting toxicity, dissipating phlegm and resolving masses. Officially recognized species of PCsP include Pleione bulbocodioides (Franch.) Rolfe (PB), Cremastra appendiculata (D. Don) Makino (CA), and Pleione yunnanensis (Rolfe) Rolfe (PY). Approximately, 234 compounds have been isolated and identified from PCsP. The most thoroughly investigated constituents are stilbenes (bibenzyls and phenanthrenes) and glucosyloxybenzyl succinate derivatives. Other compounds include lignans, flavonoids, and simple phenolics. The extracts and purified compounds of PCsP have exhibited anti-cancer, hepatoprotective, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective and antioxidant potentials. Furthermore, pharmacological investigations support its traditional use for treating cancer. However, there is not enough data on the toxicity and quality control of this important herb. Moreover, the mechanism of action of active compounds and extracts need to be studied, with special attention to the effectiveness of PCsP against cancer. This review article aims to provide a critical overview of the botanical description, traditional uses, chemical constituents, pharmacological effects and clinical studies to provide a solid base for further research and development.

Keywords

PCsP

Traditional uses

Phytochemistry

Pharmacological activities

Clinical applications

- A549

-

Non-small-cell lung carcinoma

- A2780

-

Ovarian cancer cell line

- AKT

-

Protein Kinase B

- Bax

-

BCL2-Associated X

- BChE

-

Butyrylcholinesterase

- Bcl-2

-

B-cell lymphoma-2

- Bel7402

-

Liver cancer cell line

- BGC-823

-

Human gastric carcinoma

- CD-4+

-

Cluster differentiation 4+

- Cyt-c

-

Cytochrome c

- D-GalN

-

D-galactosamine

- EC50

-

Half-maximal effective concentration

- HCT-8

-

Human colon cancer cell line

- HepG2

-

Human hepatocellular carcinoma

- IC50

-

Half maximal inhibitory concentration

- LA795

-

Mouse lung adenocarcinoma cells

- MCF-7

-

Human breast cancer

- MDA-MB-231

-

Human breast cell line

- MTT

-

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- PC12

-

Pheochromocytomaderived cell line

- ROS

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SH-SY5Y

-

Human myeloid neuroblastoma

- THP-1

-

Human acute monocytic leukemia cell line

- VEGF

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Pseudobulbus Cremastrae seu Pleiones (PCsP), belonging to the family Orchidaceae, has been employed in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) for the treatment of cancer (Wang et al., 2013b; Hao et al., 2019). Clinical studies have shown that the combined application of TCM and chemotherapy not only reduces the toxicity of chemotherapy but also reverses the drug resistance of tumors (Zhang et al., 2020). Chinese Materia Medica (CMM) has been in use for thousands of years, with due recognition from the international community. PCsP has been used to treat cancer in both the ancient and modern era. However, current pharmacological studies have revealed that it may not be very effective against cancer. This may be attributed to the additive, synergistic, suppressive, and antagonistic interactions of PCsP’s, when it is part of a multicomponent prescription, which is common in TCM. These interactions, nevertheless are sometimes essential in improving their therapeutic potential and reducing the side effects of certain toxic ingredients (Pan et al., 2020).

The dry tubers of PB, PY, CA are considered to be the official sources of the PCsP in TCM (Committee for the Pharmacopoeia of PR China., 2020). PB and PY belong to the genus Pleione (Orchidaceae), while CA belongs to the genus Cremastra (Orchidaceae). The three precious orchid plants are perennial epiphytic or terrestrial herbs with beautiful flowers, mainly produced in East China, Central China, and Southwest China. During the last few decades, several reports have been published on the phytochemistry, bioactivities, and clinical applications of PCsP. Among the three plants, PB and CA have been the most studies ones, while PY has not been studied a lot. Furthermore, Tulipa edulis (Miq.) Baker (Guangcigu in Chinese) and Iphigenia indica Kunth et Benth. (Lijiang Shancigu in Chinese) are the counterfeit drug of PCsP in folk medicine (Liu et al., 2020). These two plants belong to Liliaceae family and contain the toxic colchicine. In modern studies, some researchers have used the two Liliaceae plants as PCsP to study their toxicities, causing confusion in future studies (Si et al., 2020). The chemical constituents of PB were first of all reported by Bai et al in 1996 (Bai et al., 1996a; Bai et al., 1996b). In the next 20 years, more than 234 compounds were isolated from PCsP by only Japanese and Chinese phytochemists, including bibenzyls, phenanthrenes, glucosyloxybenzyl succinate derivatives, lignans, flavonoids, and simple phenolics. The secondary metabolites and extracts of PCsP possess anti-cancer, hepatoprotective, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective and antioxidant activities (Si et al., 2020).

During the past few years, several Chinese research groups have made great contributions in exploring the chemical constituents, biological effects and clinical studies of the PCsP. However, no systematic review article discussing these achievements is available in the English literature. This article is focused on presenting a comprehensive overview of the botanical description, traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and clinical applications of PCsP to provide a basis for further research on these important medicinal herbs.

2 Botanical description, distribution, and cultivation

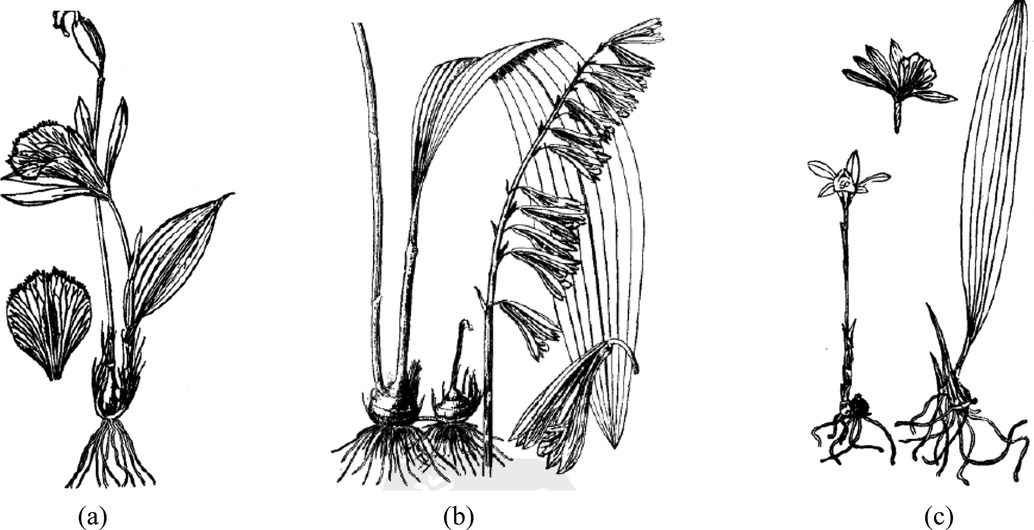

PB and PY are mainly distributed in West China. CA could be found in China, Japan, India and Southeast Asian countries. These plants primarily grow in humus-covered soil, on mossy rocks in evergreen broad-leaved forests and at thicket margins at an elevation of 500–3600 m (https://www.iplant.cn/foc/). The morphological of PB, CA, PY, as referenced by the Flora of China is presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Species

Botanical characteristics

Tubers

Leaves

Flowers

PB

ovoid to ovoid-conic, with a conspicuous neck, 1–2.5 × 1–2 cm

1-leaved; immature at anthesis, developing after flowering, narrowly elliptic-lanceolate or suboblanceolate, 10–25 × 2–5.8 cm, papery, base attenuate into a petiole-like stalk 2–6.5 cm, apex acute or acuminate.

Inflorescence erect; peduncle 7–20 cm, covered by 3 tubular sheaths below middle; floral bracts linear-oblong, (20−)30–40 mm, apex obtuse; flower solitary or rarely 2, pink to pale purple, with dark purple marks on lip.

CA

Ovoid or subglobose, 1.5–3 × 1–3 cm

1-leaved; narrowly elliptic, subelliptic, or narrowly elliptic- oblanceolate; 18–34 × 5–8 cm, base attenuate into a petiole-like stalk 7–17 cm, apex acute or acuminate.

Inflorescence erect; peduncle 27–70 cm, covered by some epibiotic tubular sheaths below middle; floral bracts lanceolate-ovate-lanceolate, (3-)5–12 mm, apex obtuse; 5–22 flowers, lavender brown.

PY

green, ovoid, narrowly ovoid, or conic, with a conspicuous neck 1.5–3 × 1–2 cm

1-leaved; very immature or undeveloped at anthesis, lanceolate to narrowly elliptic, 6.5–25 × 1–3.5 cm, papery, base attenuate into a petiole-like stalk 1–6 cm, apex acuminate or subacute.

Inflorescence erect; peduncle 10–20 cm, with several sheaths below middle; floral bracts obovate to obovate-oblong, 20–30 × 5–8 mm, shorter than ovary, apex obtuse; flowers solitary or rarely 2, purplish, pink, or sometimes white, with purple or deep red spots on lip.

Sketch of PB (a), CA (b) and PY (c). (Cited from the Flora of China, http://www.iplant.cn/foc/).

Furthermore, over-exploitation of wild medicinal resources of PCsP, during the recent past years has caused a depletion in the natural reserves, inducing an inflation in the market price. To address the issue, cultivation on mass scale has been carried out. However, the problem associated with cultivation is a long growth period, low yields, and slow propagation. Both sexual and asexual methods of reproduction are being employed at present. Seeds are used in sexual reproduction, while the tubers are exploited for asexual reproduction method. Sexual method of reproduction does not seem very feasible or productive because of small seed size, poor maturity, technological requirements, and long seedling rate etc. The plantation period is shortened in asexual method and the method is simple and convenient, meeting the production requirements. This makes the method a better option for reproduction. It is usually cultivated in spring (May to June) and autumn (August to September) from the tubers. Tubers with plump, strong buds, no mechanical or pest/insect damage are selected for the purpose (Norimoto et al., 2021).

Under forest raising is another suitable plantation method and one for the future. Wild cultivation has the advantages of being a low cost method with high economic benefit, making full use of natural resources, realizing three-dimensional management and comprehensive utilization of forest land for improving product quality (Bing and Zhang, 2008).

3 Traditional uses

PCsP has been widely used as traditional Chinese medicine for over thousand years. The dry tubers of the plants are used for medicinal purposes. In Summer and Fall, the aerial parts of the fresh PB, CA, or PY are removed. Due to the characteristics of PCsP described by Chinese medical theories (sweet, little pungent in taste, and cool in nature), it has been used to treat conditions such as furuncles, carbuncles, scrofulous sputum, snake and insect bites, abdominal masses and lumps. The recommended dosage is 3–9 g (Wu et al., 2019) (Committee for the Pharmacopoeia of PR China, 2020).

According to Chinese medicinal books, PCsP was first recorded in “Ben Cao Shi Yi” during the Tang Dynasty (perhaps earlier). In this book, PCsP was described as a treatment for carbuncle, ulcer fistula, scrofula tuberculosis, etc. In “Ben Cao Gang Mu”, another classic book of TCM, PCsP has been reported as a cure for furuncles, carbuncles, scrofulous sputum, snake and insect bites. According to “Dian Nan Ben Cao” (Ming Dynasty), it is effective in reducing phlegm and stopping cough and sore throat. The preparations of PCsP in combination with other herbals as shown in Table 2.

Names

Prescriptions

Traditional uses

Ref.

Zijin Ding (紫金锭)

PCsP, Knoxia Root, Semen Euphorbiae Pulveratum, Galla Chinensis, Moschus, Realgar, Cinnabar

Dissipating phlegm, opening orifices, detoxification and relieving swelling and pain. It is mainly used for the treatment of abdominal distension and pain, vomiting and diarrhea, heat stroke, food and drug poisoning, headache, toothache, and traumatic injury, etc.

“Ben Cao Xin Bian” (Qing Dynasty)

Zhoushi Huisheng Wan (周氏回生丸)

PCsP, Galla Chinensis, Radix Aucklandiae, Flos Caryophylli, Semen Euphorbiae Pulveratum, Moschus, Borneol, Lignum Santali Albi, Lignum Aquilariae Resinatum, Radix Glycyrrhizae, Radix Knoxiae, Medicated Leaven, Realgar Cinnabar

Expelling summer heat and dispersing cold, detoxification, resolving dampness and relieving pain. It is used for cholera vomiting and diarrhea, acute filthy disease and abdominal pain.

Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020 version)

Longbishu Jiaolang (癃闭舒胶囊)

PCsP, Fructus Psoraleae, Herbal Leonuri, Creeping Dichondra Herb, Spora Lygodii, Lamber

Nourishing kidney and promoting blood circulation clearing heat and freeing strangury.

Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020 version)

Qige Tang (启膈汤)

PCsP, Eupolyphaga, Scolopendra, Herba Scutellariae Barbatae, Radix Codonopsis, Rhizoma Pinelliae

Nourishing qi, promoting blood circulation, detoxification and eliminating phlegm. It is mainly used to treat esophageal carcinoma with dysphagia.

(Wu and Chen, 1993)

Xiaoai Jiedufang消癌解毒方

PCsP, Radix Ophiopogonis, Radix Pseudostellariae, Fruit of austral Akenia, Bombyx Batryticatus, Scolopendra

Eliminating cancer, detoxification, strengthening body and eliminating pathogen

(Guo et al., 2017)

4 Phytochemisrty

The PCsP is rich in stilbenes and glucosyloxybenzyl succinate derivatives. Till date, a total of 234 compounds, including 35 bibenzyls, 92 phenanthrenes, 36 glucosyloxybenzyl succinate derivatives, 7 lignans, 14 flavonoids, 22 simple phenolics, and 28 other compounds (Table 2) have been isolated and identified from PB, CA, and PY. Among the three orchid plants, 127, 104, and 61 compounds were isolated from PB, CA, and PY, respectively. Most of these compounds were isolated from the tubers of these plants. The name and chemical structures of these compounds are shown in Table 3 and Figs. 2–6. Plausible biogenetic pathway of some different types of stilbenes is given in Fig. 7 (Shao et al., 2019; Sun et al., 2021).

NO.

Compounds

Species

Ref.

Bibenzyls

1

3,5-dimethoxy-3′-hydroxybibenzyl

PB, PY

(Liu et al., 2011a; Xu et al., 2020)

2

3′-O-methylbatatasin III

PB, PY

(Bai et al., 1997a; Dong et al., 2013)

3

gigantol

PB, CA

(Li et al., 2015b; Li et al., 2020)

4

batatasin III

PB, PY, CA

(Bai et al., 1997a; Dong et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013b)

5

bauhinol C

PB

(Li et al., 2015b)

6

2,5,2′,5′-tetrahydroxy-3-methoxybibenzyl

PB

(Li et al., 2015b)

7

3,5,3′-trihydroxybibenzyl

CA

(Li et al., 2015a)

8

batatsin III-3-O-glucoside

PB, PY

(Bai et al., 1997a; Dong et al., 2013)

9

3′,5-dimethoxybibenzyl-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

PB, PY

(Bai et al., 1997a; Dong et al., 2013)

10

shancigusin F

PY

(Dong et al., 2013)

11

5,4′-dihydroxy-bibenzyl-3-O-β-D-glucoside

CA

(Li et al., 2015a)

12

5-methoxyl-bibenzyl-3,3′-di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

PB, CA

(Liu et al., 2008a; Han et al., 2019)

13

shancigusin E

PY

(Dong et al., 2013)

14

gymconopin D

PB

(Liu et al., 2007a)

15

bulbocol

PB

(Bai et al., 1998b)

16

shancigusin D

PY

(Dong et al., 2010)

17

3,3′-dihydroxy-2-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-5-methoxybibenzyl

PB, PY, CA

(Dong et al., 2010; Qin and Shen, 2011; Zhang et al., 2013)

18

3′,5-dihydroxy-2-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-3-methoxybibenzyl

PB, PY, CA

(Dong et al., 2010; Qin and Shen, 2011; Zhang et al., 2013)

19

shancigusin C

PY

(Dong et al., 2010)

20

5-O-methylshanciguol

PB, PY, CA

(Dong et al., 2010; Li et al., 2015b; Lin et al., 2016)

21

blestritin B

PB

(Li et al., 2015b)

22

shanciguol

PB, PY

(Bai et al., 1996a; Dong et al., 2010)

23

shancigusin A

PY

(Dong et al., 2010)

24

shancigusin B

PY

(Dong et al., 2010)

25

bulbocodin

PB

(Li et al., 2015b)

26

bulbocodin C

PB

(Bai et al., 1998a)

27

bulbocodin D

PB, CA

(Bai et al., 1998a; Liu et al., 2016c)

28

arundinin

PB, PY, CA

(Bai et al., 1998b; Dong et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013b)

29

shanciol A

PB

(Bai et al., 1998c)

30

shanciol B

PB

(Bai et al., 1998c)

31

2-(4′'-hydroxybenzyl)-3-(3′-hydroxy-phenethyl)-5-methoxy-cyclohexa-2,

5-diene-1,4-dionePB

(Liu et al., 2008b)

32

dusuanlansin A

PB

(Li et al., 2015b)

33

dusuanlansin B

PB

(Li et al., 2015b)

34

dusuanlansin C

PB

(Li et al., 2015b)

35

dusuanlansin D

PB

(Li et al., 2015b)

Phenanthrenes

Dihydrophenanthrenes

36

coelonin

PB, PY, CA

(Xuan et al., 2005; Dong et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017)

37

lusianthridin

PB, PY, CA

(Dong et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2020)

38

hircinol

PB

(Wang et al., 2014a)

39

isohircinol

CA

(Xuan et al., 2005)

40

7-hydroxy-2,4-dimethoxy-9,

10-dihydrophenanthreneCA

(Wang et al., 2013b)

41

1,2,7-trihydroxy-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydroxyphenanthrene

PY

(Xu et al., 2020)

42

1,4,7-trihydroxy-2-methoxy-9,10-dihydroxyphenanthrene

PY

(Xu et al., 2020)

43

2,5,7-trihydroxy-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydroxyphenanthrene

PY

(Xu et al., 2020)

44

4,7-dihydroxy-1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-2-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene

PB, PY

(Bai et al., 1996a; Dong et al., 2013)

45

2,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxy-1-(p-hydroxy-benzyl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene

PB, PY

(Dong et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015b)

46

1-(4-hydroxybenzyl)-4,7-dimethoxy-9,

10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-olPB, PY

(Li et al., 2015b; Xu et al., 2020)

47

1-(3′-methoxy-4′-hydroxybenzyl)-7-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2,4-diol

CA

(Liu et al., 2013)

48

shancigusin G

PY, CA

(Dong et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013b)

49

7-hydroxy-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydro-phenanthrene-2-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

CA

(Wang et al., 2013b)

50

4-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2,7-di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

CA

(Wang et al., 2013b)

Phenanthrenes

51

7-hydroxy-2,4-dimethoxy-phenanthrene

CA

(Qin and Shen, 2011)

52

2-hydroxy-4,7-dimethoxy-phenanthrene

CA

(Xue et al., 2006)

53

2,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxy-phenanthrene

PY, CA

(Wang et al., 2013b; Li et al., 2021)

54

3,5-dihydroxy-2,4-dimethoxy-phenanthrene

CA

(Liu et al., 2014)

55

7-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2-O-β-D-glucoside

CA

(Xia et al., 2005)

56

7-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,8-di-O-β-D-glucoside

CA

(Liu et al., 2016c)

57

8-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,7-di-O-β-D-glucoside

CA

(Liu et al., 2016c)

58

1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-2,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxy-phenanthrene

PB, PY, CA

(Qin and Shen, 2011; Dong et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014a)

59

1-(3′-methoxy-4′-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol

CA

(Liu et al., 2013)

60

1-(3′-methoxy-4′-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,6,7-triol

CA

(Liu et al., 2013)

61

cremaphenanthrene L

CA

(Liu et al., 2015)

62

cremaphenanthrene M

CA

(Liu et al., 2015)

63

cremaphenanthrene N

CA

(Liu et al., 2015)

64

cremaphenanthrene O

CA

(Liu et al., 2015)

65

cremaphenanthrene P

CA

(Liu et al., 2015)

Biphenanthrenes

66

cremaphenanthrene A

CA

(Liu et al., 2016b)

67

cremaphenanthrene B

CA

(Liu et al., 2016b)

68

blestriarene C

PY, CA

(Dong et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013b)

69

monbarbatain A

PB, PY, CA

(Liu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014a)

70

2,7,2′-didroxy-4,4′,7′-trimethoxy-1,

10-biphenanthrenePB, CA

(Wang et al., 2014a; Liu et al., 2015)

71

2,2′-dihydroxy-4,7,4′,7′-tetramethoxy-1,1′-biphenanthrene

CA

(Xue et al., 2006)

72

blestriarene B

CA

(Wang et al., 2013b)

73

4,7,4′-trimethoxy-9′,10′-dihydro

(1,1′-biphenanthrene)-2,2′,7′-triolCA

(Liu et al., 2015)

74

blestriarene A

PB, PY, CA

(Wang et al., 2013b; Wang et al., 2014a; Wang et al., 2014b)

75

isoarundinin I

PB

(Li et al., 2015b)

76

blestrianol A

PB, CA

(Wang et al., 2013b; Wang et al., 2019)

77

cremaphenanthrene C

CA

(Liu et al., 2016b)

78

gymconopin C

CA

(Wang et al., 2013b)

79

9′,10′-dihydro-4,5′-dimethoxy-(1,3′-biphenanthrene)-2,2′,7,7′-tetrol

CA

(Wang et al., 2013b)

80

cremaphenanthrene F

CA

(Liu et al., 2021)

81

cremaphenanthrene G

CA

(Liu et al., 2021)

82

phochinenin B

CA

(Liu et al., 2016b)

83

cremaphenanthrene D

CA

(Liu et al., 2016b)

84

cremaphenanthrene E

CA

(Liu et al., 2016b)

85

blestrin D

CA

(Liu et al., 2016b)

86

blestrin C

CA

(Liu et al., 2016b)

87

M-bulbocodioidin E

PB

(Wang et al., 2019)

88

P-bulbocodioidin E

PB

(Wang et al., 2019)

89

M-bulbocodioidin F

PB

(Wang et al., 2019)

90

P-bulbocodioidin F

PB

(Wang et al., 2019)

91

M-bulbocodioidin G

PB

(Wang et al., 2019)

92

P-bulbocodioidin G

PB

(Wang et al., 2019)

Dihydrophenanthrene/phenanthrene and bibenzyl polymers

93

M-bulbocodioidin H

PB

(Wang et al., 2019)

94

P-bulbocodioidin H

PB

(Wang et al., 2019)

95

phoyunnanin A

PB

(Li et al., 2015b)

96

shancilin

PB

(Bai et al., 1996a)

Triphenanthrene

97

2,7,2′,7′,2′'-pentahydroxy-4,4′,4′',7′'-tetramethoxy-1,8,1′,1′'-triphenanthrene

CA

(Xue et al., 2006)

Dihydrophenanthrene and phenylpropanoid polymers

98

pleionesin B

PB, PY

(Dong et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014a)

99

pleionesin C

PY

(Dong et al., 2011)

100

(2,3-trans)-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-3-hydroxymethyl-10-methoxy-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-phenanthro[2,1-b]furan-7-ol

CA

(Wang et al., 2013b)

101

pleionesin A

PY

(Dong et al., 2011)

102

shanciol H

PB, PY, CA

(Dong et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2013b; Wang et al., 2014a)

103

9-(4′-hydroxy-3′-methoxyphenyl)-10-(hydroxymethyl)-11-methoxy-5,6,9,10-tetrahydrophenanthro[2,3-b]furan-3-ol

PB

(Liu et al., 2009)

104

(3-hydroxy-9-(4′-hydroxy-3′-methoxyphenyl)-11-methoxy-5,6,9,10-tetrahydrophenanthro [2,3-b] furan-10-yl) methyl acetate

PB

(Liu et al., 2007a)

105

bletilol A

PB

(Bai et al., 1998c)

106

bletilol B

PB

(Bai et al., 1996b)

107

shanciol F

PB, PY

(Bai et al., 1998a; Dong et al., 2011)

108

shanciol C

PB

(Bai et al., 1998c)

109

shanciol

PB

(Bai et al., 1998c)

110

shanciol E

PB

(Bai et al., 1998a)

111

shanciol D

PB

(Bai et al., 1998c)

112

bletilol C

PB

(Bai et al., 1998c)

113

(2,3-trans)-3-[(2,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxy-phenanthren-1-yl)methyl]-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-10-methoxy-

2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-phenanthro[2,1-b]furan-7-olCA

(Wang et al., 2013b)

114

(2,3-trans)-3-[2-hydroxy-6-(3-hydroxy-phenethyl)-4-methoxybenzyl]-2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-10-methoxy-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-phenanthro[2,1b]furan-7-ol

CA

(Wang et al., 2013b)

Phenanthraquinones

115

(R)-bulbocodioidin A

PB

(Shao et al., 2019)

116

(S)-bulbocodioidin A

PB

(Shao et al., 2019)

117

(R)-bulbocodioidin B

PB

(Shao et al., 2019)

118

(S)-bulbocodioidin B

PB

(Shao et al., 2019)

119

(R)-bulbocodioidin C

PB

(Shao et al., 2019)

120

(S)-bulbocodioidin C

PB

(Shao et al., 2019)

121

(R)-bulbocodioidin D

PB

(Shao et al., 2019)

122

(S)-bulbocodioidin D

PB

(Shao et al., 2019)

123

2,6-dihydroxy-8-methoxy-1,4-phenanthraquinone

CA

(Li et al., 2020)

124

1-hydroxy-4,7-dimethoxy-1-(2-oxopropyl)-1H-phenanthren-2-one

CA

(Xue et al., 2006)

125

1,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxy-1-(2-oxopropyl)-1H-phenanthren-2-one

CA

(Xue et al., 2006)

126

bulbocodioidin I

PB

(Shao et al., 2020)

127

bulbocodioidin J

PB

(Shao et al., 2020)

Glucosyloxybenzyl succinate derivatives

128

pleionoside G

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

129

pleionoside H

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

130

pleionoside I

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

131

gymnoside I

PB, PY

(Dong et al., 2013; Han et al., 2019)

132

militarine

PB, PY, CA

(Dong et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013b; Han et al., 2019)

133

(−)-(2R,3S)-1-[(4-O-β-D-glucopy-ranosyloxy)benzyl]-4-methyl-2-isobutyltartrate

PB, CA

(Wang et al., 2013b; Han et al., 2019)

134

loroglossin

PB, PY, CA

(Wang et al., 2013b; Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2021)

135

1-[4-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)benzyl]-4-methyl-(R)-2-hydroxy-2-isobutylsuccinate

PY, CA

(Wang et al., 2013b; Han et al., 2021)

136

1-(4-β-D-Glucopyranosyloxybenzyl) 4-ethyl (2R)-2-isobutylmalate

CA

(Wang et al., 2013b)

137

pleionoside R

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

138

pleionoside S

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

139

pleionoside U

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

140

pleionoside Q

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

141

pleionoside T

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

142

pleionoside P

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

143

pleionoside M

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

144

pleionoside N

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

145

pleionoside O

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

146

shancigusin H

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

147

dactylorhin A

PB, PY

(Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2021)

148

gymnoside III

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

149

dactylorhin E

PY

(Han et al., 2021)

150

pleionoside A

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

151

pleionoside B

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

152

pleionoside C

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

153

pleionoside D

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

154

vandateroside II

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

155

pleionoside E

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

156

pleionoside F

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

157

grammatophylloside B

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

158

grammatophylloside A

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

159

cronupapine

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

160

1-(4-β-D-glucopyranosyloxybenzyl) 4-methyl (2R)-2-benzylmalate

CA

(Wang et al., 2013b)

161

(−)-(2S)-1-[(4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyloxy) benzyl]-2-isopropyl-4-[(4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)benzyl] malate

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

162

bletillin A

PB

(Li et al., 2015b)

163

(Z)-2-(2-methylpropyl)butenedioic acid bis(4-β-D-glucopyranosyloxybenzyl) ester

PB

(Wang et al., 2013a)

Lignans

164

sanjidin A

PB

(Bai et al., 1997b)

165

sanjidin B

PB

(Bai et al., 1997b)

166

pleionin A

PB

(Bai et al., 1997b)

167

(−)-syringaresinol

PY

(Dong et al., 2013)

168

syringaresinol mono-O-β-Dglucoside

PB

(Han et al., 2019)

169

phillygenin

PB

(Zhang et al., 2013)

170

(7S,8R)-dehydrodiconiferyl alcohol-

9′-O-β-D-glucopyranosidePB

(Han et al., 2019)

Flavonoids

171

quercetin

CA

(Liu et al., 2014)

172

quercetin 3′-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

CA

(Liu et al., 2014)

173

genkwanin

CA

(Liu et al., 2014)

174

isorhamnetin-3,7-di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

PB

(Li et al., 2017)

175

3′-O-methylquercetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

PB

(Li et al., 2017)

176

5,7-dihydroxy-8-methoxyflavone

PB

(Zhang et al., 2013)

177

3,5,3′-trihydroxy-8,4′-dimethoxy-7-(3-methylbut-2-enyloxy)flavone

PB

(Li et al., 2017)

178

3,5,7,3′-tetrahydroxy-8,4′-dimethoxy-6-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)flavone

PB

(Li et al., 2017)

179

kayaflavone

PB

(Yuan and Liu, 2012)

180

amentoflavone

PB

(Yuan and Liu, 2012)

181

corylin

CA

(Lin et al., 2016)

182

neobavaisoflavone

CA

(Lin et al., 2016)

183

isobavachalcone

CA

(Lin et al., 2016)

184

5,7-dihydroxy-3-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxy-benzyl)-6-methoxychroman-4-one

CA

(Shim et al., 2004)

Simple phenolics

185

p-hydroxybenzcic acid

PB

(Yuan and Liu, 2012)

186

p-hydroxy benzaldehyde

PB

(Yuan and Liu, 2012)

187

4-(methoxymethyl) phenol

PB

(Liu et al., 2011a)

188

4-(ethoxymethyl) phenol

PB

(Liu et al., 2011a)

189

p-dihydroxy benzene

PB

(Yuan and Liu, 2012)

190

methyl(4-OH) phenylacetate

PB

(Yuan and Liu, 2012)

191

p-hydroxyphenylethyl alcohol

CA

(Xuan et al., 2005)

192

ethyl p-hydroxyhydrocinnamate

PB

(Liu et al., 2011a)

193

syringic acid

CA

(Liu et al., 2014)

194

vanillin

CA

(Liu et al., 2014)

195

3-hydroxybenzcic acid

PB, CA

(Liu et al., 2011b; Yuan et al., 2017)

196

protocatechuic acid

CA

(Liu et al., 2008a)

197

p-coumaric acid

CA

(Zhang et al., 2011)

198

3-methoxy-4-hydroxy phenylethanol

CA

(Liu et al., 2014)

199

ethyl 3-hydroxyhydrocinnamate

PB

(Liu et al., 2011a)

200

vanillic acid

CA

(Zhang et al., 2011)

201

trans-cinnamic acid

PB

(Liu et al., 2011a)

202

3,4-dihydroxyphenylethyl alcohol

CA

(Xuan et al., 2005)

203

4,4′-dihydroxy-bisphenxyl

PB

(Zhang et al., 2013)

204

(E)-p-hydroxycinnamic acid

PY

(Wang et al., 2014b)

205

(E)-ferulic acid

PY

(Wang et al., 2014b)

206

(E)-ferulic acid hexacosyl ester

PY

(Wang et al., 2014b)

Others

207

β-sitosterol

PB, PY, CA

(Dong et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2016)

208

daucosterol

PY, CA

(Xuan et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2011b; Dong et al., 2013)

209

ergosta-4,6,8(14),22-tetraen-3-one

PB

(Wang et al., 2014a)

210

cyclolaudanol

CA

(Qin and Shen, 2011)

211

(−)-cadin-4,10(15)-dien-11-oic acid

CA

(Li et al., 2008)

212

(+)-24,24-dimethyl-25,32-cyclo-5α-lanosta-9(11)-en-3β-ol

CA

(Li et al., 2008)

213

(−)-ent-12b-hydroxykaur-16-

en-19-oic acid 19-β-D-xylopyranosyl-

(1 → 6)-O-β-D-glucopyranosideCA

(Li et al., 2008)

214

pleionol

PB

(Bai et al., 1998b)

215

pleionoside K

PB

(Han et al., 2020)

216

pleionoside L

PB

(Han et al., 2020)

217

emodin

CA

(Liu et al., 2014)

218

chrysophanol

PB, CA

(Zhang et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014)

219

physcion

PB, CA

(Zhang et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2014)

220

adenosine

PY, CA

(Xia et al., 2005; Dong et al., 2013)

221

aurantiamide acetate

CA

(Qin and Shen, 2011)

222

cremastrine

CA

(Ikeda et al., 2005)

223

gastrodin

PB, CA

(Wang et al., 2013b; Han et al., 2019)

224

tyrosol 8-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

CA

(Xia et al., 2005)

225

4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-2-methoxypheny l-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

CA

(Xia et al., 2005)

226

shancigusin I

PY, CA

(Dong et al., 2013; Yuan and Liu, 2015)

227

pleionoside K

CA

(Han et al., 2019)

228

2,6,2′,6′-tetramethoxy-4,4′-bis(2,3-epoxy-1-hydroxypropyl)biphenyl

CA

(Lin et al., 2016)

229

2-furoic acid

CA

(Zhang et al., 2011)

230

5-hydroxymethyl furfural

PB, CA

(Liu et al., 2011b; Qin and Shen, 2011)

231

4-(4′'-hydroxybenzyl)-3-(3′-hydroxy-phenethyl)furan-2(5H)-one

PB

(Liu et al., 2007b)

232

3-(3′-hydroxyphenethyl)furan-2(5H)-one

PB

(Liu et al., 2007b)

233

tephrosin

CA

(Tu et al., 2018)

234

succinic acid

PY

(Dong et al., 2013)

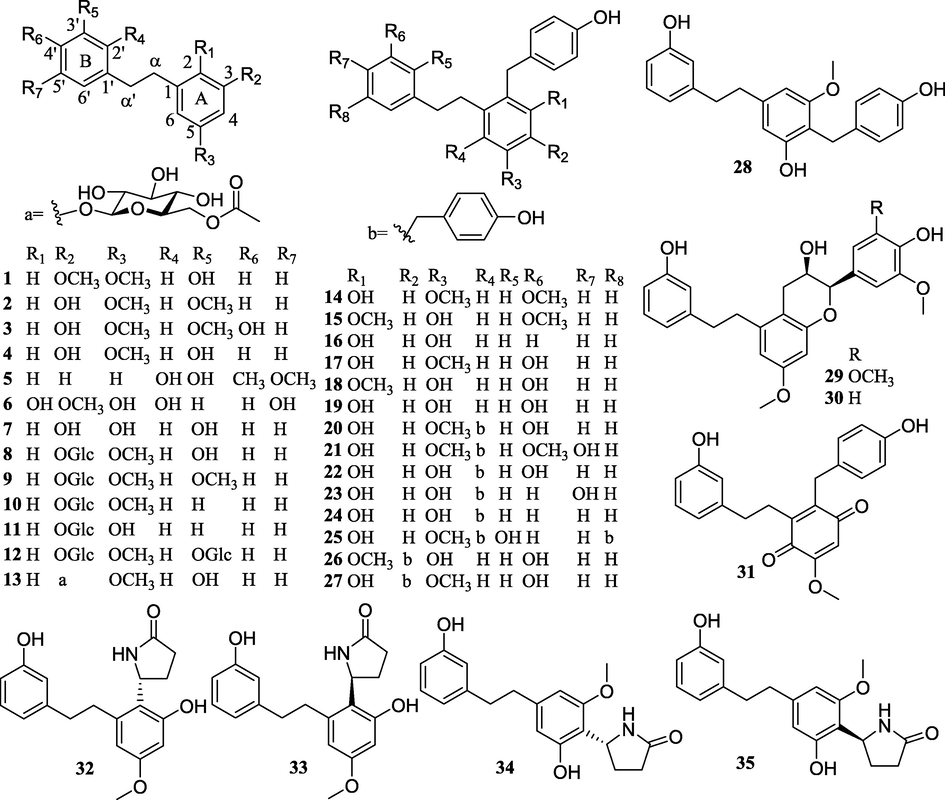

Structures of bibenzyls isolated from PCsP.

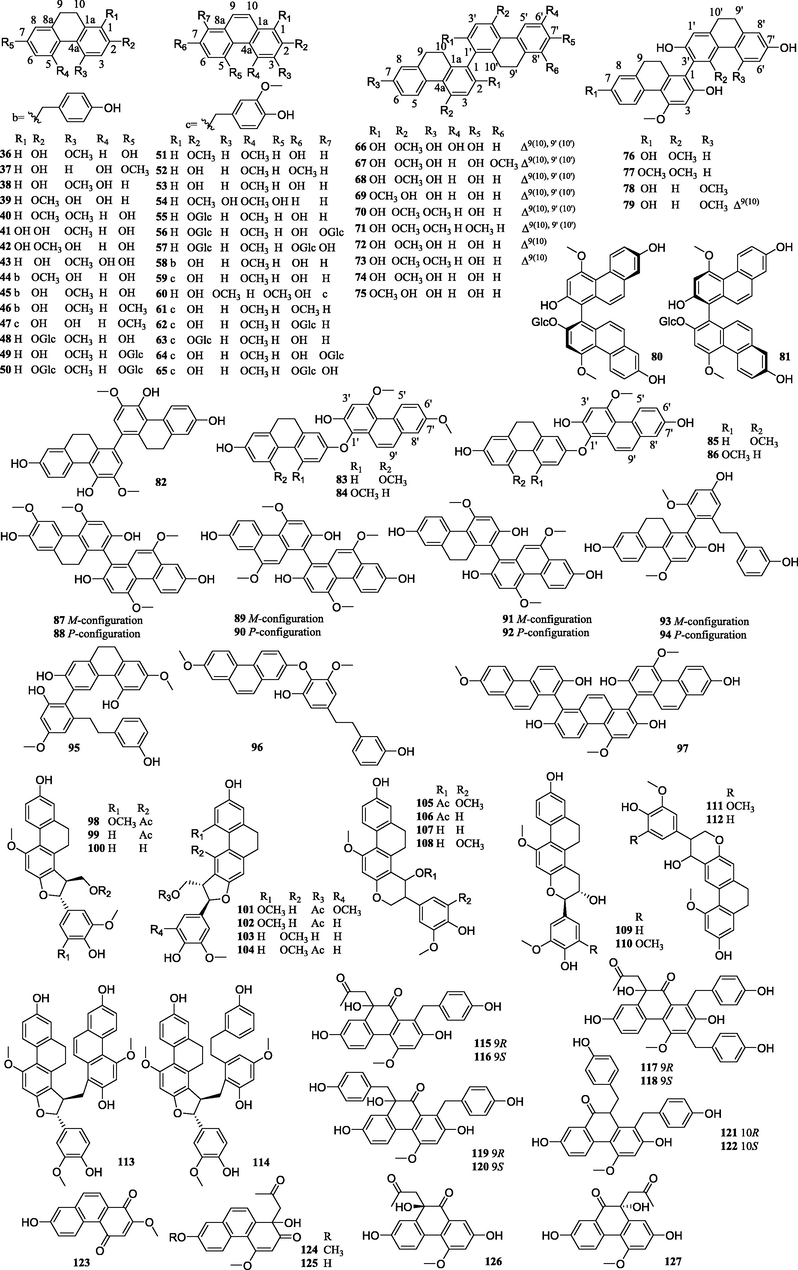

Structures of phenanthrenes isolated from PCsP.

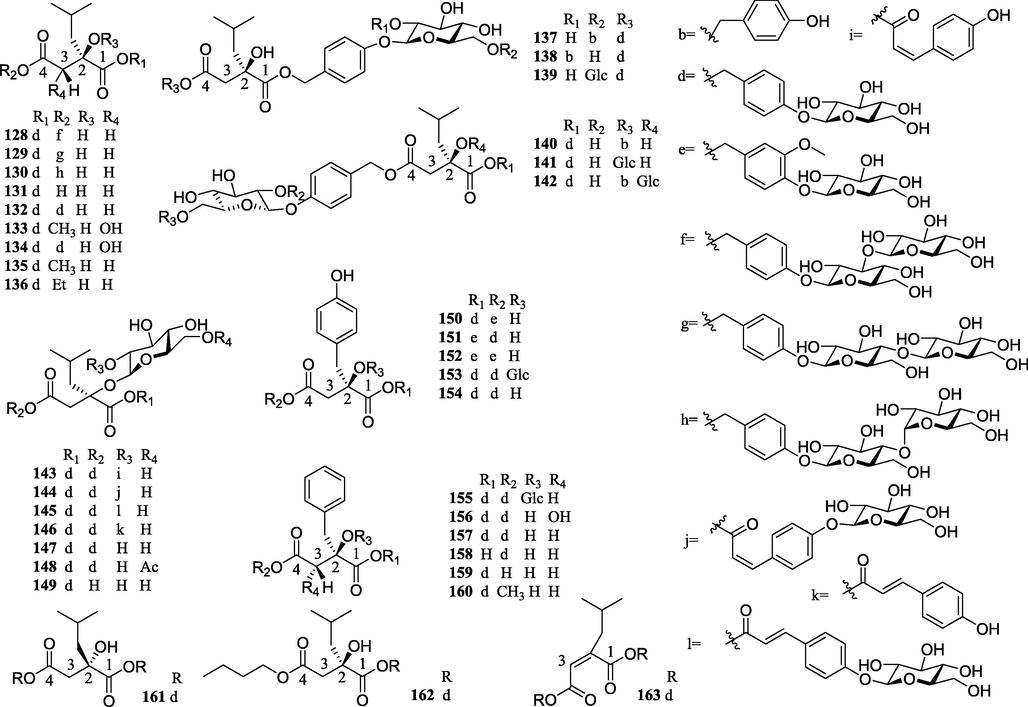

Structures of glucosyloxybenzyl succinate derivatives isolated from PCsP.

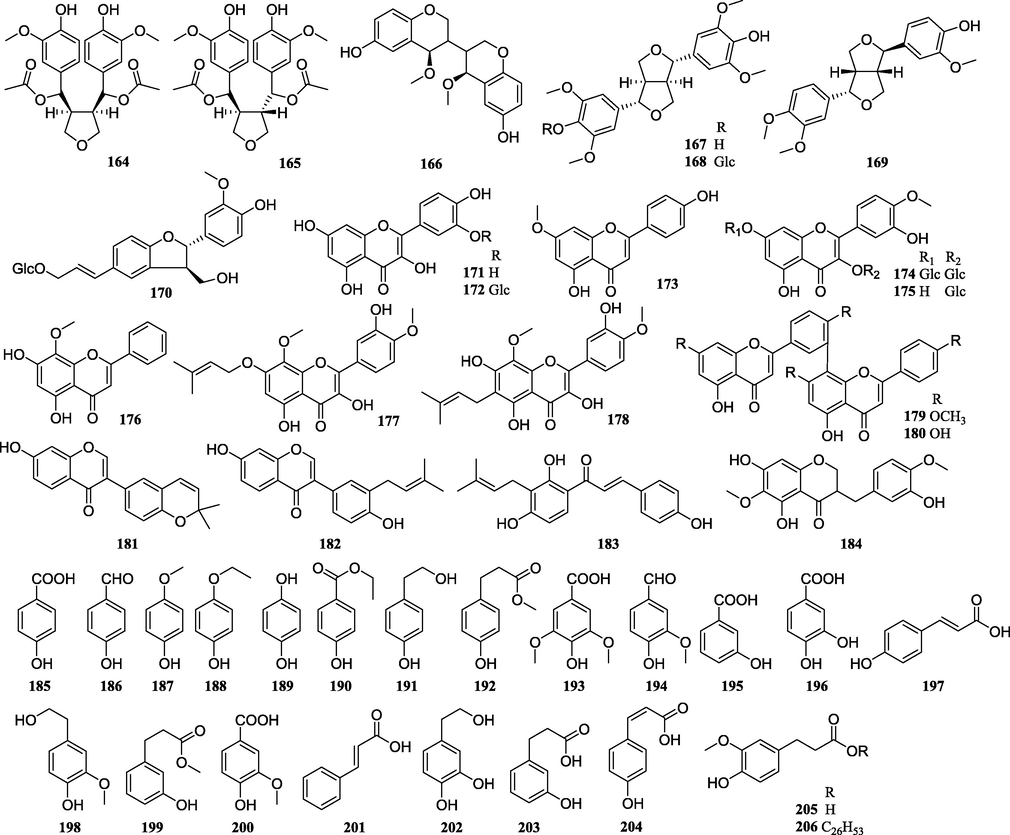

Structures of lignans, flavonoids, and simple phenolics isolated from PCsP.

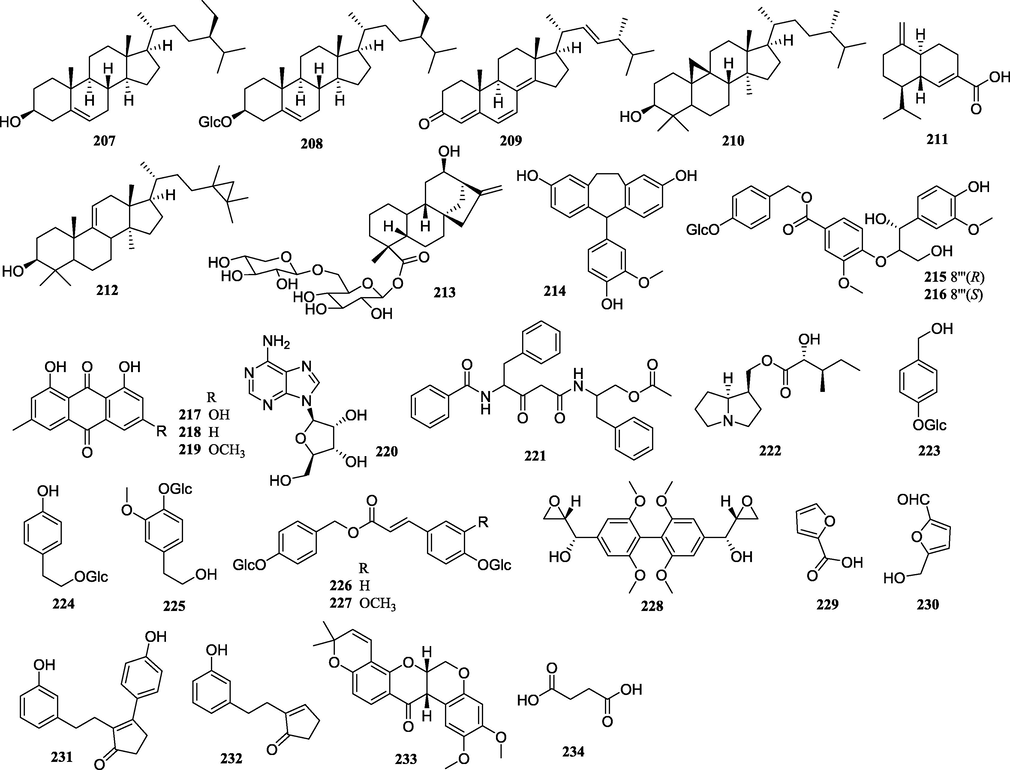

Structures of other compounds isolated from PCsP.

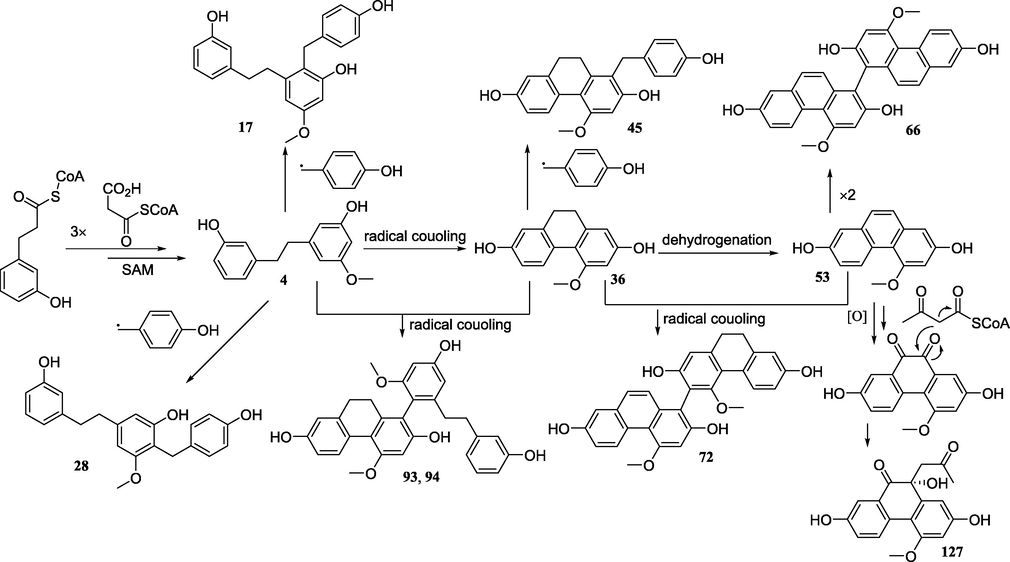

Plausible biogenetic pathway of some different types of stilbenes.

4.1 Bibenzyls

Bibenzyls contains a simple skeleton, just like one hydrogen on each of the two carbons in ethane being replaced by a phenyl group. These are usually found in bryophytes and Orchidaceae plants (Asakawa et al., 2013). Even so, their structural diversity stems from the number and positions of the substituents. Compounds 1–13 are simple bibenzyls, substituted with methoxy, hydroxy, and glucosyl groups. In 1997, 3′-O-methylbatatasin III (2), batatsin III-3-O-glucoside (8), and 3′,5-dimethoxybibenzyl-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (9) were isolated from the tubers of PB for the first time (Bai et al., 1997a). Compounds 14–28 are complex bibenzyls which have a 4-hydroxybenzyl group at C-2 or C-4, at least. Shanciguol (22) was isolated from the tubers of PB in 1996 (Bai et al., 1996a). Four compounds identified as shancigusins A-D (16, 19, 23 and 24) were isolated from the tubers of PY (Dong et al., 2010). Furthermore, some other interesting bibenzyls (29–35) found in PB are also given below. Shanciol A (29) and shanciol B (30) are flavan-3-ols which are simple bibenzyls combined with a phenylpropanoid moiety (Bai et al., 1998c); Compound 31 has a p-benzoquinone skeleton (Liu et al., 2008b), while compounds 32–35 are pyrrolidone substituted bibenzyls (Li et al., 2015b).

4.2 Phenanthrenes

The phenanthrenes are a rather uncommon class of aromatic metabolites which are presumably formed by oxidative coupling of the aromatic rings of stilbene precursors (Kovács et al., 2008). Ninety-two phenanthrenes, classified into 7 types have been isolated from the tubers of PB, CA, and PY. They can be classified as dihydrophenanthrenes (36–50), phenanthrenes (51–65), biphenanthrenes (66–92), dihydrophenanthrene/phenanthrene and bibenzyl polymers (93–96), triphenanthrene (97), dihydrophenanthrene and phenylpropanoid polymers (98–114), and phenanthraquinones (115–127).

The synthetic precursors of dihydrophenanthrenes are bibenzyls (Reinecke and Kindl, 1993). Coelonin (36) and lusianthridin (37) have been reported from all the plants of PCsP (Xuan et al., 2005; Dong et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2020). 4,7-dihydroxy-1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-2-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene (44), 2,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxy-1-(p-hydroxy-benzyl)-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene (45), and 1-(4-hydroxybenzyl)-4,7-dimethoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-ol (46) were isolated from the tubers of PB and PY (Bai et al., 1996a; Dong et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015b; Xu et al., 2020). Isohircinol (39), 7-hydroxy-2,4-dimethoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene (40), 1-(3′-methoxy-4′-hydroxybenzyl)-7-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2,4-diol (47), 7-hydroxy-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (49) and 4-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2,7-di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside have only been reported from were found in the tubers of CA (Xuan et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2013b).

All the phenanthrenes (51–65) can be found in CA. 2,7-Dihydroxy-4-methoxy-phenanthrene (53) and 1-(p-hydroxybenzyl)-2,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxy-phenanthrene (58) also were isolated from PY and PB/PY, respectively (Qin and Shen, 2011; Dong et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013b; Wang et al., 2014a; Li et al., 2021). More than 20 dimeric phenanthrene include 9,10-dihydro- and dehydro derivatives were obtained from the PCsP. The monomers are mostly 1–1′-linked, but 1–3′ and 2-O-1′ linkages also occur in these plants. The dimeric phenanthrenes derivatives have been regarded as optically pure compounds for a long time except one study which mentioned that the isolated biphenanthrene derivatives existed as racemates (Yao et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2019). Biphenanthrene atropisomers, cremaphenanthrene F (80) and cremaphenanthrene F (81) were obtained from the tubers of CA. Three pairs of racemic bi(9,10-dihydro)phenanthrene atropisomers, bulbocodioidins E-G (87–92) were isolated from the pseudobulbs of PB (Wang et al., 2019).

Four dihydrophenanthrene/phenanthrene and bibenzyl polymers, M-bulbocodioidin H (93), P-bulbocodioidin H (94), phoyunnanin A (94) and shancilin (95) were isolated from the tubers of PB (Bai et al., 1996b; Li et al., 2015b; Wang et al., 2019). 2,7,2′,7′,2′'-pentahydroxy-4,4′,4′',7′'-tetramethoxy-1,8,1′,1′'-triphenanthrene (96) was the only triphenanthrene which was isolated from the CA (Xue et al., 2006). In 2011, 5 dihydrophenanthrenes, pleionesin B (98), pleionesin C (99), pleionesin A (1 0 1), shanciol H (1 0 2) and shanciol F (1 0 7) were isolated from the tubers of PY (Dong et al., 2011). Eight dihydrophenanthrenes, bletilol A (1 0 5), bletilol B (1 0 6), shanciol F (1 0 7), shanciol C (1 0 8), shanciol (1 0 9), shanciol E (1 1 0), shanciol D (1 1 1) and bletilol C (1 1 2) were obtained from the tubers of PB by Japanese phytochemists (Bai et al., 1996b; Bai et al., 1998a; Bai et al., 1998b; Bai et al., 1998c). Bulbocodioidins A-D (115–122, 126 and 127) were the 4 pairs of phenanthrenequinone enantiomers found only in the tubers of PB (Shao et al., 2019). 2,6-Dihydroxy-8-methoxy-1,4-phenanthraquinone (1 2 3), 1-hydroxy-4,7-dimethoxy-1-(2-oxopropyl)-1H-phenanthren-2-one (1 2 4) and 1,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxy-1-(2-oxopropyl)-1H-phenanthren-2-one (1 2 5) were only isolated from the tubers of CA (Xue et al., 2006; Li et al., 2020).

4.3 Glucosyloxybenzyl succinate derivatives

A total of 36 glucosyloxybenzyl succinate derivatives have been isolated from the PCsP. These compounds can be divided into three groups, i.e., glucosyloxybenzyl 2-isobutylsuccinates (128–149 and 161–163), glucosyloxybenzyl 2-p-hydroxybenzylsuccinates (150–154), and III-glucosyloxybenzyl 2-benzylsuccinates (155–160). Militarine (1 3 2) and loroglossin (1 3 4) were isolated from all the three plants of PCsP (Dong et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013b; Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2021). Gymnoside I (1 3 1), (−)-(2R,3S)-1-[(4-O-β-D-glucopy-ranosyloxy)benzyl]-4-methyl-2-isobutyltartrate (1 3 3), 1-[4-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)benzyl]-4-methyl-(R)-2-hydroxy-2-isobutylsuccinate (1 3 4) and dactylorhin A (1 4 7) were isolated from the two plants of PCsP (Dong et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013b; Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2021). The other compounds were just found in one of plants of PCsP. Furthermore, this type of compounds, including 31 compounds all can be found in the tubers of PB/PY by one research group, Dr Shuai Li’s group (Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2021). In fact, this research group has been working on the phytochemistry of PCsP for more than 10 years (Li et al., 2008; Han et al., 2021).

4.4 Lignans

Till date, only 7 lignans have been found in PCsP. Most of them are tetrahytrofunan lignans, except pleionin A (1 6 6), which is different (Bai et al., 1997b).

4.5 Flavonoids

Flavonoids are important natural products but only 14 compounds were isolated from the PCsP. Even though the amount of the compounds is limited, but the type is diverse. Quercetin (1 7 1), quercetin 3′-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (1 7 2), genkwanin (1 7 3), isorhamnetin-3,7-di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (1 7 4), 3′-O-methylquercetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (1 7 5), and 5,7-dihydroxy-8-methoxyflavone (1 7 6) are simple flavonoids; 3,5,3′-trihydroxy-8,4′-dimethoxy-7-(3-methylbut-2-enyloxy)flavone (1 7 7), 3,5,7,3′-tetrahydroxy-8,4′-dimethoxy-6-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)flavone (1 7 8), corylin (1 8 1), and neobavaisoflavone (1 8 2) are prenylated flavonoids; kayaflavone (1 7 9) and amentoflavone (1 8 0) are bioflavonoids; isobavachalcone (1 8 3) is a chalcone and 5,7-dihydroxy-3-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxy-benzyl)-6-methoxychroman-4-one (1 8 4) is a homo-isoflavanone.

4.6 Simple phenolics

Twenty-six simple phenolics have been obtained from the PCsP. They are important natural products because they can protect plants by offering against insects, viruses, and bacteria (Heleno et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2019).

4.7 Other compounds

Other compounds including 3 steroids (207–209), 4 terpenoids (210–213), 1 polyphenol (2 1 4), 2 phenylpropanoid glycosidic (215–216), 3 anthraquinones (217–219), 3 nitrogen compounds (220–222), 5 simple glycosidics (223–227), and 7 others (228–234) have been reported from the PCsP. The terpenoids including 2 triterpenoids (210 and 212), 1 sesquiterpenoid (2 1 1), and 1 diterpenoid (2 1 3) were only found in the tubers of CA (Li et al., 2008; Qin and Shen, 2011; Liu et al., 2013).

5 Pharmacology

5.1 Anti-cancer activity

5.1.1 The cytotoxicity effect

The cytotoxic effects of batatasin III (4), P-bulbocodioidin H (94), shanciol F (1 0 7), (R)-bulbocodioidin A (1 1 5), (S)-bulbocodioidin D (1 2 2) and bulbocodioidin J (1 2 7) isolated from the ethanolic extract of tubers of PB were evaluated against several human cancer cell lines. Compounds 4 and 107 showed weak cytotoxic activity against the growth of LA795 tumor cell line with IC50 value of 76 and 21 μM (Liu et al., 2007a). Compound 115 showed moderate inhibition activities against HepG2, BGC-823, MCF-7 cell lines with respective IC50 values of 8.1, 8.4 and 3.9 μM. Compounds 94 and 122 exhibited marked cytotoxic activities against HCT-116, HepG2, MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 values of 7.6, 3.8, 3.4 μM and 8.3, 2.3, and 2.5 μM, respectively (Taxol as the positive control with IC50 values of 0.001–0.03 μM) (Shao et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019). Compound 127 exhibited cytotoxic activity against MCF-7 with the IC50 value of 2.1 μM (Taxol was used as the positive control) (Shao et al., 2020).

According to the cytotoxicity assay, 14 compounds, 1-(3′-methoxy-4′-hydroxybenzyl)-7-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2,4-diol (47), 1-(3′-methoxy-4′-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol (59), 1-(3′-methoxy-4′-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,6,7-triol (60), cremaphenanthrene L (61), Blestriarene C (68), 2,2′-dihydroxy-4,7,4′,7′-tetramethoxy-1,1′-biphenanthrene (71), blestriarene B (72), blestriarene A (74), 2,7,2′,7′,2′′-pentahydroxy-4,4′,4′′,7′′-tetramethoxy-1,8,1′,1′′-triphenanthrene (97), pleionesin C (99), shanciol H (1 0 2), (2,3-trans)-3-[(2,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxy-phenan-thren-1-yl)methyl]-2-(4-hydroxy-3 meth-oxyphenyl)-10-methoxy-2,3,4,5 tetra-hydrophenanthro[2,1-b]furan-7-ol (1 1 3), (2,3-trans)-3-[2-hydroxy-6-(3-hydroxyphenethyl)-4-methoxybenzyl]-2-(4-hydroxy-3 met-hoxyphenyl)-10-methoxy-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-phenanthro[2,1-b]furan-7-ol (1 1 4), and (+)-24,24-dimethyl-25,32-cyclo-5α-lanosta-9(11)-en-3β-ol (2 1 2) isolated from the tubers of CA showed different activities against several human cancer cell lines. Compounds 72, 74, 99, 102, 113, and 114 showed weak or moderate cytotoxic activity against A549 cells with IC50 values of 48.2, 47.5, 33.6, 42.8, 38.0, and 16.0 μM, respectively, with bufalin as the positive control (IC50 = 0.05 μM) (Wang et al., 2013b). Compounds 47 and 59 exhibited moderate cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 cell line with IC50 values of 10.42 and 11.92 μM, respectively; while compound 60 was found moderately active against HCT-116 cell line with IC50 value of 14.22 μM, while the IC50 values of paclitaxel against HCT-116 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines were 2.33 and 0.002 μM, respectively (Liu et al., 2013). Compounds 68, 71 and 97 exhibited moderate cytotoxicity against A549, A2780, Bel7402, BGC-823, HCT-8, and MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 values ranging from 8.4 to 17.8 μM, 9.5–11.9 μM, and 8.0–11.6 μM, respectively. Topotecan was used as positive control with IC50 values ranging from 1.1 to 4.4 μM (Xia et al., 2005; Xue et al., 2006). Compound 61 showed moderate cytotoxic activities against HCT-116, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines with IC50 values of 19.01, 24.18, and 15.84 μM, respectively, (paclitaxel, IC50 values of 2.33, 0.08, and 0.002 μM, respectively) (Liu et al., 2015). Compound 212 showed in vitro-selective cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cell line with an IC50 of 3.18 μM (Li et al., 2008). It also was found that the ethyl acetate fraction of the pseudobulb of PB and CA had significant anti-tumor activity by MTT method (Liu et al., 2011b; Li et al., 2015a).

5.1.2 Inhibit the proliferation of tumor cells

Liu et al and Wu et al found that the water decoction of CA could significantly inhibit the proliferation of 4 T1 and SW579 cells in dose-dependent manner (Wu, 2014; Liu et al., 2016d). Xing et al studied the inhibitory effect of different concentrations of CA water extracts on MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation. They concluded that the mechanism may be related to the inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway (Xing et al., 2020). Yu et al reported the anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of CA on thyroid cancer SW579 cells. The effect was attributed to the down-regulation of Bcl-2 protein (Yu et al., 2018).

5.1.3 Induce the apoptosis of tumor cells

Xu et al studied the anti-tumor effect and mechanism of PY polysaccharides on mice with H22 hepatocellular carcinoma and found that the probable route of inhibitory effect of PYRP on mice with H22 solid tumor is immune enhancement and acceleration of cell apoptosis (Xu et al., 2016). The water extracts of CA have shown significant effects on inducing the apoptosis of 4T1 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Liu et al., 2016d). The CA extract can also induce the apoptosis in HT29 cells by enhancing the expression of Cyt-C, Bax and Caspase-3 protein and at the same time suppressing Bcl-2 protein (Yu and Zhai, 2016). The polysaccharides from PY can promote mice H22 solid tumor cell fragmentation observed by HE staining and inhibit the expression of antiapoptotic factor Bcl-2 in different degrees. The expression of p53 has been found to increase with a decrease in differentiation of tumor cells (Xu, 2015). Hao et al studied the effects of an ethyl acetate extract of PB on the cell viability and apoptosis of THP-1 (human acute monocytic leukemia cell line) and its interaction with possible apoptotic pathways. The results showed that the EtOAc extract of PB significantly inhibits cell viability and induces cell apoptosis in THP-1 through a mitochondria-regulated intrinsic apoptotic pathway (Hao et al., 2019). It has been studied that the 55% ethanol extract of PCsP can inhibit the proliferation of human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells in vitro. The activity may be related to the down-regulation of Bcl-2 expression and up-regulation of Bax and Caspase-3 protein, inducing apoptosis (Xing et al., 2020). Similarly, the ethyl acetate extract of CA has also been found to induce apoptosis in lung cancer A549 cells (Zhang et al., 2020).

5.1.4 Inhibition of tumor angiogenesis

The aqueous extracts of PCsP has been found effective against breast cancer in vivo in a dose dependent manner by inhibiting the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) (Yang et al., 2018). The homoisoflavanone (1 8 4), obtained from the tubers of CA, inducing angiogenesis of the chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) of chick embryo both in vitro and in vivo. The compound was found to be non-toxic and at the same time effectively inhibited the bFGF-induced invasion of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in a dose-dependent manner in vitro with IC50 value of 0.5 μM using retinoic acid as positive control (IC50 = 0.3 μM) (Shim et al., 2004).

5.1.5 Improving human immunity

Jiang et al found that PCsP polysaccharide exhibited potent anti-tumor activity by enhancing lymphocyte proliferation capacity and macrophage phagocytic activity, increasing the levels of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells in mice and elevating the CD4+/CD8 + ratio, interleukin-2, tumor necrosis factor-α and interferon-γ levels, that may be related to the improvement of immune function (Jiang et al., 2018).

5.2 Hepatoprotective activity

Five compounds, pleionoside C (1 5 2), pleionoside D (1 5 3), pleionoside F (1 5 6), pleionoside K (2 1 5) and pleionoside L (2 1 6), isolated from the pseudobulbs of PB exhibited moderate hepatoprotective activity against the N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (APAP)-induced HepG2 cell damage in in vitro assays, with cell survival rates of 31.89%, 31.52%, 31.97%, 25.83% and 28.82% at 10 μM, respectively (Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020).

The chemical constituents of the pseudobulbs of PY showed interesting hepatoprotective activities, tested through the MTT method. pleionoside Q (1 4 0), pleionoside R (1 3 7), shancigusin H (1 4 6), and 1-[4-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)benzyl]-4-methyl-(R)-2-hydroxy-2-isobutylsuccinate (1 3 5) showed significant in vitro hepatoprotective activity against (D-galactosamine) D-GalN-induced toxicity in HL-7702 cells with increasing cell viability by 27%, 22%, 19%, and 31% compared to the positive group (cf. bicyclol, 14%) at 10 μM, respectively. On the other hand, Pleionoside P (1 4 2), pleionoside U (1 3 9), and dactylochin A (1 4 7) exhibited moderate activity by enhancing the cell viability by 9%, 16%, and 12% compared to the positive group (cf. bicyclol, 9%) at 10 μM, respectively (Han et al., 2021). However, the pathophysiological mechanisms of D-GalN and APAP-induced liver injury are different and complex. Therefore, it is necessary to further study the mechanisms by which these compounds play a protective role in these two different liver injury models in the future.

5.3 Anti-inflammatory activity

2,5,2′,5′-Tetrahydroxy-3-methoxybibenzyl (6), and 4,7-dihydroxy-2-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene (37), obtained from the pseudobulbs of PB, have shown potent anti-inflammatory activity against LPS-stimulated NO production in BV-2 microglial cells, with IC50 values of 2.46 and 5.44 μM, respectively. Quercetin was used as a positive control with IC50 value of 3.8 μM (Li et al., 2015b; Li et al., 2017). 3′-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybibenzyl (2), 1,2,7-trihydroxy-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydroxyphenanthrene (41), and 2,5,7-trihydroxy-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydroxyphenanthrene (43), isolated from the tubers of PY, have exhibited strong inhibitory effects on NO production in LPS-activited RAW264.7 cells without showing any obvious cytotoxicity toward RAW264.7 cells at the highest concentration, and their IC50 values ranged from 6.02 to 12.25 μM (Xu et al., 2020). 2,5,2′,5′-Tetrahydroxy-3-methoxybibenzyl (6) and 4,7-dihydroxy-2-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene (37) possessed strong anti-inflammatory effects on LPS-stimulated NO production in BV-2 microglial cells with IC50 values of 2.46 and 3.14 μM, respectively (Li et al., 2015b). The anti-inflammatory mechanism of PCsP needs further study.

5.4 Neuroprotective activity

The 55% ethanol extract of the tubers of CA has been found to significantly reduce excessive ROS production due to oxidative stress in PC12 cells, exerting thus exert its neuroprotective effect by inhibiting mitochondrial apoptosis pathway (Huo et al., 2018). Moreover, the 95% ethanol extract of the tubers of CA was found to significantly inhibit the butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) enzyme (IC50 = 23.66 µg/mL) and β-amyloid peptide aggregation (74.09% at 100 μg/mL). Coelonin (36) and orchinol (40), 7-hydroxy-2,4-dimethoxy-phenanthrene (51), obtained from this plant exhibited potent BChE inhibitory effects with IC50 values of 19.66, 32.80, and 37.79 µM, respectively. Kinetic studies indicated that both compounds 40 and 51 were mixed-type BChE inhibitors. Meanwhile, compounds 40 and 51 also inhibited the β-amyloid peptide aggregation (64.49% and 29.50% at 20 μM, respectively), indicating that they could serve as multifunctional potential agents against Alzheimer′s disease (AD) (Tu et al., 2018).

Keeping in view the inhibitory potential of the crude extract of CA tubers against apoptosis of human myeloid neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y), the isolates of the same were probed for the same activity, revealing that compounds 132 and 228 performed well in neuroprotection assay in a hydrogen peroxide model, through weakening of the oxidative damage (Lin et al., 2016).

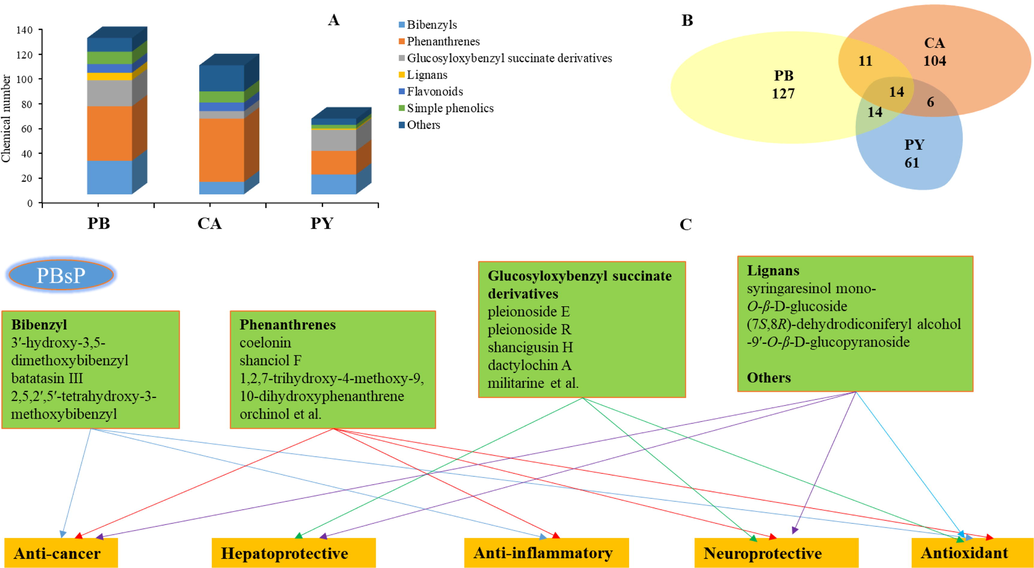

5.5 Antioxidant activity

Six compounds, pleionoside E (1 5 5), syringaresinol mono-O-β-D-glucoside (1 6 8), (7S,8R)-dehydrodiconiferyl alcohol-9′‐O-β-D-glucopyranoside (1 7 0), 3′-hydroxyl-5-methoxyl bibenzyl-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (8), pleionoside K (2 1 5) and pleionoside L (2 1 6), isolated from the pseudobulbs of PB were tested for antioxidant activity against H2O2-induced toxicity in SK-N-SH cells by means of MTT method, exhibiting moderate antioxidant activity with the cell viability increasing by 36.1%, 45.0%, 25.5%, 20.7%, 24.9% and 34.6%, respectively at 10 μM in comparision with the positive group (Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020). Meanwhile, coelonin (36) and orchinol (40) isolated from the tubers of CA exhibited the effective DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities (EC50 < 11 μM) (Tu et al., 2018). Furthermore, the polysaccharides from PCsP could have antioxidative effects by scavenging superoxide anion radicals, DPPH free radicals and hydroxyl free radicals (Fang et al., 2017). Furthermore, the antioxidant mechanism of PCsP needs further research.

6 Clinical applications

Clinical studies have shown that the combined application of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and chemotherapy not only reduces the toxicity of chemotherapy but also reverse the resistance of tumors against drugs (Zhang et al., 2020). There is limited data on the clinical studies of PCsP. Most of the formulations involve the crude extracts along with other herbs. Statistics suggest that the prescriptions with PCsP as an ingredient, are effective in lowering body temperature and detoxification, which could be helpful for treatment of liver and lung cancer (Shen, 2008). Upon analysis of the clinical symptoms, tumor markers, and tumor foci of 20 patients with liver cancer, surviving without surgical treatment, it was revealed that “Xiaoaijiedu” prescription could improve the clinical symptoms of patients with advanced liver cancer and stabilize the disease (Zhu et al., 2019). Another group of 198 patients with advanced tumors showed marked improvement in health when treated with “Xiaoaijiedu”, avoiding the side effects of chemotherapy. Thus PCsP shows good prospects of development as an anti-cancer drug (Zhu et al., 2019). Furthermore, a group of 60 patients diagnosed with malignant tumors were treated with “Ketong San”, applied externally. The product showed good analgesic effects on mild pain (83% relief), however it was not much effective against sever pain. More importantly, no side effects were reported (Jiang et al., 2010). In another study, carried out on a group of 90 advanced lung cancer patients, PCsP formulation was found very effective as compared to chemotherapy (Gu and Wu, 2016). PCsP also exhibits good analgesic effects in metastatic bone pain, revealed through a study conducted on 41 patients with this disorder (Gao and Feng, 2011). A total of 74 patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer were selected to study the clinical effect of the adjuvant treatment of PCsP and the results showed that PCsP had a high clinical remission rate and promoted the patients′ physical function status that good for improving the prognosis (Xiao, 2021).

7 Conclusions

Significant breakthrough has been made during the last two decades regarding the phytochemical and biological studies on PCsP. Almost all of the contribution have been made by Chinese research groups, i.e., Dr. Shui Li, Xinqiao Liu, Pengfei Tu, et al, in recent years. The larger contribution ratio by Chinese research groups may be attributed to the distribution of these plants in China. Stilbenes and glucosyloxybenzyl succinate derivatives are regarded as the major chemical constituents (Fig. 8a) of PCsP. The crude extracts and compounds from the PCsP have been shown to exhibit anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial, hepatoprotective, and neuroprotective actions (Table 4 and Fig. 8c).

Comparative understanding the phytochemistry and pharmacology of PCsP.

Effects

Species

Extracts or compounds

Results

Reference

Anti-cancer

PB

Ethyl acetate extract

It significantly inhibits cell viability and induces cell apoptosis in THP-1 through a mitochondria-regulated intrinsic apoptotic pathway.

(Hao et al., 2019)

batatasin III (4)

Showed weak cytotoxic activity against the growth of LA795 tumor cell line with the IC50 value of 76 μM.

(Liu et al., 2007)

P-bulbocodioidin H (94)

Exhibited marked cytotoxic activities against HCT-116, HepG2, MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 values of 7.6, 3.8, 3.4 μM (Taxol as the positive control with IC50 values of 0.001–0.03 μM).

(Shao et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019)

shanciol F (1 0 7)

Showed weak cytotoxic activity against the growth of LA795 tumor cell line with the IC50 value of 21 μM.

(Liu et al., 2007)

(R)-bulbocodioidin A (1 1 5)

Exhibited moderate inhibition activities in HepG2, BGC-823, MCF-7 cell lines with respective IC50 values of 8.1, 8.4 and 3.9 μM.

(Shao et al., 2019; Wang et al. 2019)

(S)-bulbocodioidin D (1 2 2)

Exhibited marked cytotoxic activities against HCT-116, HepG2, MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 values of 8.3, 2.3, 2.5 μM, respectively (Taxol as the positive control with IC50 values of 0.001–0.03 μM).

(Shao et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019)

bulbocodioidin J (1 2 7)

Showed cytotoxic activity against MCF-7 with the IC50 value of 2.1 μM (Taxol was used as the positive control).

(Shao et al., 2020)

Hepatoprotection

PB

pleionoside C (1 5 2)

Exhibited moderate hepatoprotective activity against N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (APAP)-induced HepG2 cell damage in in vitro assays, with cell survival rates of 31.89% at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2020; Han et al., 2019)

pleionoside D (1 5 3)

Exhibited moderate hepatoprotective activity against N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (APAP)-induced HepG2 cell damage in in vitro assays, with cell survival rates of 31.52% at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2020; Han et al., 2019)

pleionoside F (1 5 6)

Exhibited moderate hepatoprotective activity against N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (APAP)-induced HepG2 cell damage in in vitro assays, with cell survival rates of 31.97% at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2020; Han et al. 2019)

pleionoside K (2 1 5)

Exhibited moderate hepatoprotective activity against N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (APAP)-induced HepG2 cell damage in in vitro assays, with cell survival rates of 25.83% at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2020; Han et al. 2019)

pleionoside L (2 1 6)

Exhibited moderate hepatoprotective activity against N-acetyl-p-aminophenol (APAP)-induced HepG2 cell damage in in vitro assays, with cell survival rates of 28.82% at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2020; Han et al., 2019)

Anti-inflammation

PB

2,5,2′,5′-tetrahydroxy-3-methoxybibenzyl (6)

Exhibited potent anti-inflammatory activities on LPS-stimulated NO production in BV-2 microglial cells, with IC50 values of 2.46 μM. Quercetin was used as a positive control with IC50 value of 3.8 μM.

(Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2015b)

4,7-dihydroxy-2-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene (37)

Exhibited potent anti-inflammatory activities on LPS-stimulated NO production in BV-2 microglial cells, with IC50 values of 5.44 μM. Quercetin was used as a positive control with IC50 value of 3.8 μM.

(Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2015b)

Anti-inflammation

PY

3′-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybibenzyl (2)

Showed strong inhibitory effects on NO production in LPS-activited RAW264.7 cells without showing any obvious cytotoxicity toward RAW264.7 cells at the highest concentration, and their IC50 values of 11.20 μM.

(Xu et al., 2020)

1,2,7-trihydroxy-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydroxyphenanthrene (41)

Showed strong inhibitory effects on NO production in LPS-activited RAW264.7 cells without showing any obvious cytotoxicity toward RAW264.7 cells at the highest concentration, and their IC50 values of 6.02 μM.

(Xu et al., 2020)

2,5,7-trihydroxy-4-methoxy-9,10-dihydroxyphenanthrene (43)

Showed strong inhibitory effects on NO production in LPS-activited RAW264.7 cells without showing any obvious cytotoxicity toward RAW264.7 cells at the highest concentration, and their IC50 values of 12.25 μM.

(Xu et al., 2020)

Hepatoprotection

PY

1-[4-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)benzyl]-4-methyl-(R)-2-hydroxy-2-isobutylsuccinate (1 3 5)

Showed significant in vitro hepatoprotective activity against D-GalN-induced toxicity in HL-7702 cells with increasing cell viability by 31% compared to the positive group (cf. bicyclol, 14%) at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2021)

pleionoside R (1 3 7)

Showed significant in vitro hepatoprotective activity against D-GalN-induced toxicity in HL-7702 cells with increasing cell viability by 22% compared to the positive group (cf. bicyclol, 14%) at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2021)

pleionoside U (1 3 9)

Exhibited moderate hepatoprotective activity against APAP-induced toxicity in HepG2 cells with increasing cell viability by 16% compared to the positive group (cf. bicyclol, 9%) at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2021)

pleionoside Q (1 4 0)

Showed significant in vitro hepatoprotective activity against D-GalN-induced toxicity in HL-7702 cells with increasing cell viability by 27% compared to the positive group (cf. bicyclol, 14%) at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2021)

pleionoside P (1 4 2)

Exhibited moderate hepatoprotective activity against APAP-induced toxicity in HepG2 cells with increasing cell viability by 9% compared to the positive group (cf. bicyclol, 9%) at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2021)

shancigusin H (1 4 6)

Showed significant in vitro hepatoprotective activity against D-GalN-induced toxicity in HL-7702 cells with increasing cell viability by 19% compared to the positive group (cf. bicyclol, 14%) at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2021)

dactylochin A (1 4 7)

Exhibited moderate hepatoprotective activity against APAP-induced toxicity in HepG2 cells with increasing cell viability by 12% compared to the positive group (cf. bicyclol, 9%) at 10 μM.

(Han et al., 2021)

Anti-cancer

CA

Ethyl acetate extract

Had effect of inducing apoptosis in lung cancer A549 cells.

(Zhang et al., 2020)

1-(3′-methoxy-4′-hydroxybenzyl)-7-methoxy-9,10-dihydrophenanthrene-2,4-diol (47)

Had moderate cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 cell line with IC50 values of 10.42 μM.

(Liu et al., 2013)

1-(3′-methoxy-4′-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,7-diol (59)

Had moderate cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 cell line with IC50 values of 11.92 μM.

(Liu et al., 2013)

1-(3′-methoxy-4′-hydroxybenzyl)-4-methoxyphenanthrene-2,6,7-triol (60)

Showed moderate cytotoxicity against to HCT-116 cell line with IC50 value of 14.22 μM, while the IC50 values of paclitaxel against HCT-116 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines were 2.33 and 0.002 μM, respectively

(Liu et al., 2013)

cremaphenanthrene L (61)

Showed moderate cytotoxic activities against HCT-116, MCF-7, and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines with IC50 values of 19.01, 24.18, and 15.84 μM, respectively, paclitaxel as a positive control with IC50 value of 2.33, 0.08, and 0.002 μM, respectively.

(Liu et al., 2015)

Blestriarene C (68)

Had moderate cytotoxicity against A549, A2780, Bel7402, BGC-823, HCT-8, and MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 values ranging from 8.4 to 17.8 μM. Topotecan was used as positive control with IC50 values ranging from 1.1 to 4.4 μM.

(Xia et al., 2005; Xue et al., 2006)

2,2′-dihydroxy-4,7,4′,7′-tetramethoxy-1,1′-biphenanthrene (71)

Had moderate cytotoxicity against A549, A2780, Bel7402, BGC-823, HCT-8, and MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 values ranging from 9.5 to 11.9 μM. Topotecan was used as positive control with IC50 values ranging from 1.1 to 4.4 μM.

(Xia et al., 2005; Xue et al., 2006)

blestriarene B (72)

Showed weak cytotoxic activity against A549 cells with IC50 values of 48.2 μM (Bufalin was used as positive control, IC50 = 0.05 μM).

(Wang et al., 2013)

blestriarene A (74)

Showed weak cytotoxic activity against A549 cells with IC50 values of 47.5 μM (Bufalin was used as positive control, IC50 = 0.05 μM).

(Wang et al., 2013)

2,7,2′,7′,2′′-pentahydroxy-4,4′,4′′,7′′-tetramethoxy-1,8,1′,1′′-triphenanthrene (97)

Had moderate cytotoxicity against A549, A2780, Bel7402, BGC-823, HCT-8, and MCF-7 cell lines with IC50 values ranging from 8.0 to 11.6 μM. Topotecan was used as positive control with IC50 values ranging from 1.1 to 4.4 μM

(Xia et al., 2005; Xue et al., 2006).

pleionesin C (99)

Showed weak cytotoxic activity against A549 cells with IC50 values of 33.6 μM (Bufalin was used as positive control, IC50 = 0.05 μM).

(Wang et al., 2013)

shanciol H (1 0 2)

Showed weak cytotoxic activity against A549 cells with IC50 values of 42.8 μM (Bufalin was used as positive control, IC50 = 0.05 μM).

(Wang et al., 2013)

(2,3-trans)-3-[(2,7-dihydroxy-4-methoxy-phenan-thren-1-yl)methyl]-2-(4-hydroxy-3 meth-oxyphenyl)-10-methoxy-2,3,4,5 tetra-hydrophenanthro[2,1-b]furan-7-ol (1 1 3)

Showed weak cytotoxic activity against A549 cells with IC50 values of 38.0 μM (Bufalin was used as positive control, IC50 = 0.05 μM).

(Wang et al., 2013)

(2,3-trans)-3-[2-hydroxy-6-(3-hydroxyphenethyl)-4-methoxybenzyl]-2-(4-hydroxy-3 met-hoxyphenyl)-10-methoxy-2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-phenanthro[2,1-b]furan-7-ol (1 1 4)

Showed moderate cytotoxic activity against A549 cells with IC50 values of 16.0 μM (Bufalin was used as positive control, IC50 = 0.05 μM).

(Wang et al., 2013)

(+)-24,24-dimethyl-25,32-cyclo-5α-lanosta-9(11)-en-3β-ol (2 1 2)

Exhibited in vitro-selective cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cell line with an IC50 of 3.18 μM.

(Li et al., 2008)

Neuroprotection

CA

55% ethanol extract

It can significantly reduce excessive ROS production due to oxidative stress in PC12 cells, and thus exert its neuroprotective effect by inhibiting mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.

(Huo et al., 2018)

95% ethanol extract

Displayed potent inhibitory activities on butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) (IC50 = 23.66 µg/mL) and β-amyloid peptide aggregation (74.09% at 100 μg/mL).

(Tu et al., 2018)

55% ethanol extract

It can inhibit the apoptosis of human myeloid neuroblastoma (SH-SY5Y)

(Lin et al., 2016)

coelonin (36)

Exhibited potent BChE inhibitory effects with IC50 values of 19.66 µM.

(Tu et al., 2018)

orchinol (40)

Exhibited potent BChE inhibitory effects with IC50 values of 32.80 µM.

(Tu et al., 2018)

7-hydroxy-2,4-dimethoxy-phenanthrene (51)

Exhibited potent BChE inhibitory effects with IC50 values of 37.79 µM. Compounds 40 and 51 were mixed-type BChE inhibitors. Meanwhile, compounds 40 and 51 showed the inhibition effect on β-amyloid peptide aggregation (64.49% and 29.50% at 20 μM, respectively), indicating that they could serve as multifunctional potential agents for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) drugs development.

(Tu et al., 2018)

militarine (1 3 2)

Had the good performance of neuroprotection in hydrogen peroxide model. And the neuroprotective mechanism may be achieved by weakening the oxidative damage.

(Lin et al., 2016)

2,6,2′,6′-tetramethoxy-4,4-bis(2,3-epoxy-1-hydroxypropyl)biphenyl (2 2 8)

Had the good performance of neuroprotection in hydrogen peroxide model. And the neuroprotective mechanism may be achieved by weakening the oxidative damage.

(Lin et al., 2016)

Antioxidant

PB

3′-hydroxyl-5-methoxyl bibenzyl-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside (8)

It was tested for antioxidant activity against H2O2-induced toxicity in SK-N-SH cells by means of MTT method and showed moderate antioxidant activity with the cell viability increasing by 20.7% at 10 μM compared with the positive group.

(Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020)

pleionoside E (1 5 5)

It was tested for antioxidant activity against H2O2-induced toxicity in SK-N-SH cells by means of MTT method and showed moderate antioxidant activity with the cell viability increasing by 36.1% at 10 μM compared with the positive group.

(Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020)

syringaresinol mono-O-β-D-glucoside (1 6 8)

It was tested for antioxidant activity against H2O2-induced toxicity in SK-N-SH cells by means of MTT method and showed moderate antioxidant activity with the cell viability increasing by 45.0% at 10 μM compared with the positive group.

(Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020)

(7S,8R)-dehydrodiconiferyl alcohol-9′‐O-β-D-glucopyranoside (1 7 0)

It was tested for antioxidant activity against H2O2-induced toxicity in SK-N-SH cells by means of MTT method and showed moderate antioxidant activity with the cell viability increasing by 25.5% at 10 μM compared with the positive group.

(Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020)

pleionoside K (2 1 5)

It was tested for antioxidant activity against H2O2-induced toxicity in SK-N-SH cells by means of MTT method and showed moderate antioxidant activity with the cell viability increasing by 24.9% at 10 μM compared with the positive group.

(Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020)

pleionoside L (2 1 6)

It was tested for antioxidant activity against H2O2-induced toxicity in SK-N-SH cells by means of MTT method and showed moderate antioxidant activity with the cell viability increasing by 34.6% at 10 μM compared with the positive group.

(Han et al., 2019; Han et al., 2020)

Antioxidant

CA

coelonin (36)

Exhibited the effective DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities (EC50 < 11 μM).

(Tu et al., 2018)

orchinol (40)

Exhibited the effective DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activities (EC50 < 11 μM).

(Tu et al., 2018)

Stilbenes and glucosyloxybenzyl succinate derivatives isolated from PCsP mainly showed anti-cancer and hepatoprotective activities, respectively. Such compounds have also been reported from other genus of this family, i.e., Bletilla, Gymnadenia, Arundina, etc (Shang et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). However, the traditional use and pharmacology of these genus is different from PCsP, although the class of bioactive chemical constituents is the same. This is a question that needs to be answered by the researchers in future. Moreover, current studies are limited to explain the potential pharmacological mechanisms on anti-cancer and hepatoprotective activities for the PCsP. More relationships between the chemical constituents and biological activities should be established to further explain the principle of disease treatment. In addition, comparative comprehension on the chemical and pharmacological similarities and differences among these three orchid species should also be conducted to improve our understanding for the quality control and clinical study. In fact, the literature about quality control of the PCsP is rare. Cui et al found dactylorhin A (1 4 7) and militarine (1 3 2) are the high content in PCsP and want to use the two compounds as the Q-Marker to identify the PCsP and its confusions of herbs (Cui et al., 2013). However, the official Q-Marker of Bletilla striata also is militarine in Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020 version). From the viewpoint of similarity, 14 compounds are commonly found in PB, CA and PY (Fig. 8b). These 14 common compounds might be considered as the potential quality markers (Q-Marker) for the qualitative analysis (fingerprinting) of the PCsP (Liu et al., 2016a).

As a traditional herbal medicine, the toxicity of PCsP were rarely recorded in ancient clinical applications; in modern pharmacological research, the related toxicity of this herb in animal experiments are also limited. So more toxicity studies need to be carried out on PCsP, especially in vivo. In the TCM, the PCsP was used to help cure cancers because it has strong effect of reducing phlegm and dispersing concretion and it can be used in prescriptions for the treatment of cancerous phlegm. However, in modern study, the exact mechanisms of medicinal properties of PCsP are still query; thus, more experiment researches are needed to better understand the functions and molecular targets.

Moreover, the wild resources of the three orchid plants are decreasing with the increasing use of PCsP, and the planting technology of the three plants is not mature enough. Therefore, it is necessary to use the PCsP rationally. To sum up, the herb still needs further study and the collected literature in this review can provide a reference for future researches and medicinal exploitations of PCsP.

Authors’ contribution

Sai Jiang and Mengyun Wang wrote and revised the manuscript. Lin Jiang, Jiangyi Luo, Huimin Zhao, Siying Tian, Yuqing Zhu, and Caiyun Peng collected and analyzed the references. Salman Zafar modified the language such as grammar and spelling checking. Wei Wang designed and adjusted structure of manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by (1) The National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81874369); (2) the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant no. 2020JJ4463); (3) the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant no. 2020JJ4064); (4) the Pharmaceutical Open Fund of Domestic First-Class Disciplines (cultivation) of Hunan Province (grant no. 2020YX10); (5) the Changsha Municipal Natural Science Foundation (grant no. kq 2014086).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Phytochemical and biological studies of bryophytes. Phytochemistry. 2013;91:52-80.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Two bibenzyl glucosides from Pleione bulbocodioides. Phytochemistry. 1997;44:1565-1567.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Four stilbenoids from Pleione bulbocodioides. Phytochemistry. 1998;48:327-331.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A polyphenol and two bibenzyls from Pleione bulbocodioides. Phytochemistry. 1998;47:1637-1640.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stilbenoids from Pleione bulbocodioides. Phytochemistry. 1996;42:853-856.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lignans and a bichroman from Pleione bulbocodioides. Phytochemistry. 1997;44:341-343.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Flavan-3-ols and dihydrophenanthropyrans from Pleione bulbocodioides. Phytochemistry. 1998;47:1125-1129.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shanciol, a dihydrophenanthropyran from Pleione bulbocodioides. Phytochemistry. 1996;41:625-628.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The botanical identification of Shancigu in Chinese ancient literature. J. Syst. Evol.. 2008;46:785-792.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Determination of dactylorhin A and militarine in three varieties of Cremastrae Pseudobulbus/Pleiones Pseudobulbus by HPLC. China J. Chin. Mater. Med.. 2013;38:4347-4350.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shancigusins E-I, five new glucosides from the tubers of Pleione yunnanensis. Magn. Reson. Chem.. 2013;51:371-377.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New bibenzyl derivatives from the tubers of Pleione yunnanensis. Chem. Pharma. Bull.. 2010;40:513-515.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Complete assignments of 1H and 13C NMR data of three new dihydrophenanthrofurans from Pleione yunnanensis. Magn. Reson. Chem.. 2011;48:256-260.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Extraction and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides from Rhizoma Pleionis. J. Dalian Med. Univ.. 2017;039:527-531.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical observation on metastatic bone pain treated with application therapy with Pseudobulbus Cremastrae seu Pleiones. World J. Integr. Tradit. West. Med.. 2011;6:574-576.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical observation on the treatment of 45 cases of lung cancer with syndrome of yin deficiency and heat-poison by “Shancigu” prescription. J. New Chin. Med.. 2016;048:205-207.

- [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU Zhongying's theory of cancer toxin treating esophageal carcinoma. Chin. Arch. Tradit. Chin. Med.. 2017;35:453-456.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]