Translate this page into:

SPIONs as a nanomagnetic catalyst for the synthesis and anti-microbial activity of 2-aminothiazoles derivatives

⁎Corresponding author.

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

A series of aminothiazole derivatives have been synthesized by using ultrasmall superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPIONs) nanomagnetic catalysis, which were prepared by reducing the Fe(II) and Fe(III) precursors using aqueous ammonia then characterized by the XRD, FTIR, SEM, and TEM. The 2-aminothiazole derivatives were obtained by coupling 2-aminothiazole diazonium salt with active methylene compounds then cyclization with hydrazine hydrate to afford pyrazolyl derivatives. The one-pot reaction of 2-aminothiazole with an aromatic aldehydes in the presence of Fe3O4 NPs to give Schiff bases derivatives. An efficient protocol is developed proudest yields and reduction reaction time and easy separation. Therefore, all synthesized compounds were evaluated for anti-microbial activity.

Keywords

Nanomagnetic catalysis

2-aminothiazole derivatives

Pyrazolyl derivatives

Schiff bases

Aromatic aldehyde

Anti-microbial activity

1 Introduction

Thiazole is a core structural element plays an important role in nature and has a wide range of applications in medicinal chemistry (Xue et al., 2014). Thiazole heterocycle is a main structural motif of many natural compounds such as vitamin B1 (thiamine), penicillin, and carboxylase (Zhu et al. 2012; Das et al., 2016). 2-Aminothiazoles are one of the most important classes of heterocyclic compounds, that contain nitrogen and sulfur are present in compounds possessing scaffolds due to the medical and pharmaceutical applications (Das et al., 2016; Smith et al., 2012; Giridhar et al, 2001; Ali and Sayed, 2021; Hussein et al., 2020), such as antihypertension (Patt et al., 1992), antibacterial (Joseph et al., 2017), anti-inflammation, antiviral (Venkatachalam et al., 2001), antimycobacterial (Makam et al., 2013; Elsadek et al., 2021; Dayan et al., 2021), anticonvulsant (Siddiqui and Ahsan, 2010), antileishmanial (Bhuniya et al., 2015), HIV infections (Bell et al., 1995), anticancer (Elsadek et al., 2021; Chugunova et al., 2021; Kuzhandaivel et al., 2021; Özbek and Gürdere, 2021), antitumor (Hersi et al., 2020), antidiabetic (Iino et al., 2009) and antioxidative (Uchikawa et al., 1996). Therefore, in recent times, increasing attention has been paid to the synthesis of heterocycles compounds the development of an environmentally benign and efficient procedure for the synthesis of 2-aminothiazoles derivatives (Ali et al., 2010) has become particularly fascinating and remains a great challenge. Recently, nanomagnetic catalysts have been used as heterogeneous green catalysts. However, this study focuses on the development synthesis of 2-aminothiazoles derivatives by using the nanomagnetic catalyst for the effective synthesis via the one-pot reaction. Concentration of Piperacillin = 4 µg/ml; Ceftazidime = 1 µg/ml; Oxacillin = 2 µg/ml; Fluconazole = 0.5 mg/ml.

Compd. No

Inhibition Zone (mm ± SD)

E. coli

P. aeruginosa

Bacillus

S. aureus

Candida

(1)

9.8 ± 0.2

Nil

Nil

Nil

Nil

(2)

10.15 ± 0.4

Nil

Nil

Nil

Nil

(6)

22 ± 0.8

16

Nil

Nil

Nil

(7)

16 ± 1.4

Nil

8.6 ± 0.4

12.3 ± 0.9

12 ± 0

(8)

20.6 ± 0.9

Nil

10.6 ± 0.4

Nil

Nil

(9)

8.8 ± 0.4

8 ± 0

Nil

Nil

Nil

(10)

14.3 ± 0.4

Nil

Nil

Nil

Nil

(11)

12.3 ± 0.9

11.8 ± 0.6

8.6 ± 0.9

10.6 ± 0.4

Nil

(12)

13.3 ± 1.2

Nil

Nil

10.3 ± 0.7

Nil

(13)

14.95 ± 0.5

9 ± 0.8

11.3 ± 0.4

9.6 ± 0.3

Nil

(14)

12.3 ± 0.4

Nil

10.3 ± 0.4

Nil

Nil

(15)

12.6 ± 0.5

Nil

Nil

Nil

Nil

(16)

13 ± 0.4

Nil

12.3 ± 0.4

13 ± 0.1

Nil

(17)

10.95 ± 0.3

Nil

Nil

9.3 ± 0.4

Nil

(18)

16.2 ± 0.9

14.6 ± 0.7

10 ± 0.2

11.3 ± 0.4

Nil

As ideal supports and nanocatalysts have attracted much attention in catalytic processes, due to their intriguing nanoscale dimensions, high activity, low cost, high surface area, nontoxicity, magnetically separation from the reaction media, and easy modification with other organic or inorganic species (Sadeghi et al., 2016; Azgomi and Mokhtary, 2015; Zarnegar and Safari, 2016). In recent years, magnetic nanostructures such as Fe3O4 nanoparticle (Fe3O4 NPs) was applied in the presence of atmospheric air as a green efficient, heterogeneous, and reusable catalytic system for synthesis of the heterocyclic compounds (Zolfigol et al., 2012; Bhaskaruni et al., 2020; Esfahani et al., 2011; Polshettiwar and Varma, 2010). Although, this efficient greener protocol and cleaner conditions, milder, shorter reaction time, an excellent yield of products higher purity and easier work-up procedure, easy separation using a simple external magnetic field, low cost and operational simplicity promoted us to developed novel 2-aminothiazoles derivatives by using Fe3O4 NPs.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials and methods

Melting points utilized via Stuart SMP30 Digital Advanced MP apparatus were taken in open capillary and uncorrected. FTIR spectra were carried out on IR Affinity (FTIR spectrometer) from Shimadzu, the sample prepared on a glass plate contain solid KBr. Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC/MS) were recorded on spectroscopy A LCMS-8040 Shimadzu corporation, model CAT-30A, Serial no. L20574900241 AE, 220-240v ∼ 50/60 HZ 300VA. 1H NMR and 13CNMR were recorded on BRUKER spectrometer, 400 MHZ. The samples were prepared by dissolution at DMSO‑d6. Chemical shifts (δ) are presented in part per million (ppm) using tetramethylsilane (TMS) an internal standard. Elemental microanalysis were done on Carlo Erba analyzer model 110. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on a Rigaku model Ultima-IV diffractometer employing Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at 40 kV and 25 mA over a 2θ range between 20 and 80°. All XRD measurement is handled in the air atmosphere. Samples for Scanning electron microscope (SEM) were prepared from ethanolic suspensions on single-sided alumina tape placed on alumina stubs. For the elemental analysis and mapping, the energy-dispersive X-ray spectra (EDS) were collected on a Lyra 3 (Tescan from the Chezch Republic) attachment to the SEM. TEM micrographs were obtained from a high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) (JEOL JEM-2100F) equipped with an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDX) operated at 200 kV. 300 mesh copper grids coated with carbon films were used for the imaging. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) samples were prepared by dropping it on a copper grid from an ethanolic suspension and drying at room temperature.

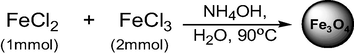

2.2 Synthesis of nanomagentic catalyst

Magnetic nanoparticles with the range of 6–8 nm were prepared as the literature procedure (Nezhad and Mohammadi, 2015). Scheme 1 shows the synthetic route for the magnetic nanoparticles. In a 250 ml, round bottom flask, hydrated ferrous chloride (FeCl2·H2O) (5 mmol, 1 g) and ferric chloride (FeCl3·H2O) (10 mmol, 4.04 g) were dissolved in de-ionized water (DI-H2O) (100 ml) under nitrogen atmosphere with a continuous stirring speed of 600 rpm. Then NH4OH (25%) solution (25 ml) was added slowly at 90 °C to raise the pH at 9. The orange color solution was turned black in 15 min and continued stirring for another 3 h to complete the reduction. The mixture was allowed to precipitate and collected using a simple magnet. The black solid was washed several times (5 × 25 ml) to remove the unreacted metal precursors and ammonia. The powdered material was dried and used for characterization and catalytic reaction.

Synthesis of Fe3O4.

2.3 Synthesis of 2-(chlorodiazenyl)thiazole (2)

Dissolve (1 mmol) of 2-aminothiazole in 3 ml of HCl keep this solution in ice at 0˚C diazotize this solution by using NaNO2 (5 mmol) solution (prepared by dissolving 5 mmol of NaNO2 in 1 ml H2O). The reaction mixture was kept onto ice bath for 3 h to give compound (2) as pink powder; yield (89.78%), mp.: 126.7 °C. FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): absence of (NH2), 3010, appearance of 2980 (CH), and 1530 (N⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm), 6.90 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-2-thiazole), 7.27 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-3-thiazole); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 170.1 (S-C-N), 150.4 (C⚌N thiazolyl), 127.0, 108.3 (C-thiazolyl); MS (m/z): 146.98 (M+, 80.5%); Anal. calcd. for C3H2ClN3S (146.96): C, 24.41; H, 1.37; Cl, 24.02; N, 28.47; S, 21.73%; found: C, 24.93; H, 1.39; Cl, 24.00; N, 28.45; S, 21.77%.

2.4 Coupling with active methylene compounds (3–5)

Reflux an equivalent mixture of (2) (1 mmol) and/or (1 mmol) ethyl acetoacetate, ethyl cyanoacetate, and acetylacetone respectively in presence of 25 ml ethanol for 1 h. The solid formed was recrystallized from ethanol to give (3–5) respectively.

2.4.1 Ethyl 3-oxo-2-(thiazol-2yldiazenyl)butanoate (3)

Light orange powder; yield (60.78%), mp.: 135.4 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm−1): 3010, 2980 (CH), 1750 (C⚌O ester and ketone) and 1590 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 1.35, 2.08 (m, 3H, 2CH3), 4.11 (m, 2H, —CH2—), 4.70 (s, 1H, CH—N); 7.16 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-2-thiazole), 7.55 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-3-thiazole), 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 171.0 (C⚌O ester), 166.9 (C⚌O), 150.4 (C⚌N thiazolyl), 125.0, 119.8 (C-thiazolyl), 62.9 (C—N), 13.6, 20.0 (CH3); 59.2 (CH2); MS (m/z): 240.05 (M+−1, 11.33%); Anal. calcd. for C9H11N3O3S (241.05): C, 44.80; H, 4.60; N, 17.42; S, 13.29%; found: C, 43.93; H, 4.44; N, 17.45; S, 13.39%.

2.4.2 Ethyl 2-cyano-2-(thiazol-2-yldiazenyl)acetate (4)

Orange powder; yield (65.45%), mp.: 144.3 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): 3010, 2980 (CH), 1749 (C⚌O), 1590 (C⚌N), 2260–2222 (CN); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 1.65 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.12 (m, 3H, —CH2—), 7.15 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-2-thiazole), 7.5 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-3-thiazole); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 171.1 (C⚌O), 152.4 (C⚌N thiazolyl), 125.0, 119.7 (CH-thiazolyl), 114.9 (CN), 50.9 (C—N), 58.7 (—CH2), 22.9 (CH3); MS (m/z): 224.04 (M+, 11.69%); Anal. calcd. for C8H8N4O2S (224.04): C, 42.85; H, 3.60; N, 24.99; S, 14.30%; found: C, 42.55; H, 3.68; N, 25.10; S, 14.40%.

2.4.3 3-(Thiazol-2-yl-hydrazono)-pentane-2,4-dione (5)

Yellow powder; yield (60.02%), mp.: 165.2 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): 3010, 2980 (CH), 1750 (C⚌O) and 1590 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 2.09 (s, 6H, 2CH3), 7.15 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-2-thiazole), 7.51 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-3-thiazole); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 206.0 (C⚌O), 85.7 (C⚌N), 151.4 (C⚌N thiazolyl), 125.0, 119.7 (C-thiazolyl), 19.3 (CH3); MS (m/z): 211.24 (M+, 22.01%); Anal. calcd. for C8H9N3O2S (211.24): C, 45.49; H, 4.29; N, 19.89; O, 15.15; S, 15.18%; found: C, 46.10; H, 4.32; N, 19.69; O, 15.05; S, 15.08%.

2.5 Synthesis of pyrazol-5-one derivatives (6–8)

An equivalent mixture of (1 mmol) of (3–5) and (2 mmol) hydrazine hydrate in presence of (0.01 mmol) of Fe3O4 the reaction mixture was stirred for 2 h at room temperature. The solid formed was recrystallized from ethanol to give (6–8) respectively.

2.5.1 3-methyl-4-(thiazol-2-yldiazenyl)-1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-one (6)

Beige powder; yield (87.02%), mp.: 155.5 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): 3250 (NH), 3010, 2980 (CH), 1750 (C⚌O) and 1590 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 1.75 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.16 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-2-thiazole), 7.55 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-3-thiazole), 8.70 (s, 1H, NH-pyrazolyl); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 166.9 (C⚌O), 156.7 (C⚌N pyrazolyl), 150.4 (C⚌N thiazolyl), 125.0, 119.7 (C-thiazolyl), 62.9 (C—N), 22.9 (CH3); MS (m/z): 209.06 (M+, 55.05%); Anal. calcd. for C7H7N5OS (209.04): C, 40.18; H, 3.37; N, 33.47; S, 15.33%; found: C, 41.00; H, 3.26; N, 33.27; S, 15.13%.

2.5.2 3-amino-4-(thiazol-2-yldiazenyl)-1H-pyrazol-5(4H)-one (7)

Orange powder; yield (80.66%), mp. 172.0 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): 3330, 3250 (NH2, NH), 3010, 2850 (CH), 1715 (C⚌O) and 1600 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 1.81 (s, 3H, CH3), 7.69 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-2-thiazole), 7.88 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-3-thiazole), 8.26 (s, 1H, NH-pyrazolyl), 8.54 (s, 1H, NH2); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 163.3 (C⚌O), 159.2 (C⚌N pyrazolyl), 140.9 (C⚌N pyrazolyl), 140.0 (C-thiazolyl), 62.9 (C—N), 15.4 (CH3); MS (m/z): 210.01 (M+, 33.2%); Anal. calcd. for C6H6N6OS (210.03): C, 34.28; H, 2.88; N, 39.98; S, 15.25%; found: C, 33.20; H, 2.90; N, 40.00; S, 15.35%.

2.5.3 (3,5-Dimethyl-4H-pyrazol-4-yl)-thiazol-2-yl-diazene (8)

Yellow powder; yield (82.03%), mp.: 186.0 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): 3380 (NH), 3010, 2850 (CH, CH3), and 1600 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 2.01 (s, 6H, 2CH3), 7.46 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-2-thiazole), 8.00 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-3-thiazole), 8.00 (s, 1H, NH-pyrazolyl). 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 164.5 (C⚌N pyrazolyl), 33.4 (C⚌N pyrazolyl), 153.0, 143.0 (C-thiazolyl), 62.9 (C—N), 15.4 (CH3); MS(m/z): 207.10 (M+, 22.11%); Anal. calcd. for C8H9N5S (207.06): C, 46.36; H, 4.38; N, 33.79; S, 15.47%; found: C, 45.49; H, 4.40; N, 33.81; S, 15.45%.

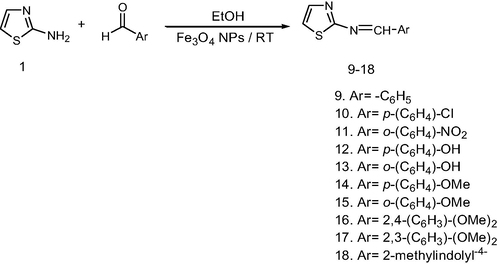

2.6 General procedure for Schiff bases synthesis of compounds (9–18)

An equivalent mixture of (1 mmol) of 1 and various aromatic aldehydes (1 mmol) namely: benzaldehyde, p-chlorobenzaldehyde, o-nitrobenzaldehyde, p-hydroxybenz- aldehyde, salicylladehyde, p-/o-anisaldehyde, 2,4-/2,3-dimethoxybenzaldehyde, and 2-methyl indolyl-3-carboxaldehyde in presence of (0.01 mmol) of Fe3O4 the reaction medium at room temperature (RT) for 1 h. The solid formed was recrystallized from ethanol to give the corresponding Schiff bases derivatives (9–18).

2.6.1 N-(benzylidene)thiazol-2-amine (9)

Yellow powder; yield (81.00%), mp.: 113–115 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): absence of (C⚌O, NH2), 3020, 2990 (CH), 1590 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 7.37–7.74 (m, 5H, CH-aromatic), 7.54 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-4-thiazole), 7.20 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5-thiazole), 9.01 (s, 1H, CH⚌N); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 171.9 (N⚌C—S), 167.1 (HC⚌N), 141.6, 119.8 (C-thiazolyl), 127.8, 124.4, 123.9 (C-aromatic); MS(m/z): 188.10 (M+, 44.05%); Anal. calcd. for C10H8N2S (188.04): C, 63.80; H, 4.28; N, 14.88; S, 17.03%; found: C, 63.76; H, 4.20; N, 14.91; S, 17.13%.

2.6.2 N-(4-chlorobenzylidene)thiazol-2-amine (10)

Brown crystal; yield (88.05%), mp.: 134.8 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): absence of (C⚌O, NH2), 3010, 2990 (CH), 1580 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 7.66–8.02 (m, 4H, CH-aromatic), 7.60 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-4-thiazole), 6.65 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5-thiazole), 8.03 (s, 1H, CH⚌N); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 171.9 (N⚌C—S), 166.6 (HC⚌N), 141.7, 119.9 (C-thiazolyl), 131.2, 129.7, 128.8 (C-aromatic); MS (m/z): 222.00 (M+, 18.52%); Anal. calcd. for C10H7ClN2S (222.00): C, 53.93; H, 3.17; Cl, 15.92; N, 12.58; S, 14.40%; found: C, 53.83; H, 3.20; Cl, 15.99; N, 12.50; S, 14.51%.

2.6.3 N-(2-nitrobenzylidene)thiazol-2-amine (11)

Orange powder; yield (80.97%), mp.: 163.5 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): absence of (C⚌O, NH2), 3020, 2990 (CH), 1610 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 6.54–7.76 (m, 4H, CH-aromatic), 7.02 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-4-thiazole), 7.01 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5-thiazole), 8.51 (s, 1H, CH⚌N); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 166.8 (N⚌C—S), 148.6 (HC⚌N), 134.4, 110.7 (C-thiazolyl), 134.2, 130.5, 129.0, 124.4 (C-aromatic); MS(m/z): 233.02 (M+, 80%); Anal calcd. for C10H7N3O2S (233.03): C, 51.49; H, 3.02; N, 18.02; S, 13.75%; found: C, 51.55; H, 3.32; N, 18.12; S, 13.75%.

2.6.4 4-((thiazol-2-ylimino)methyl)phenol (12)

Yellow powder; yield (85.43%), mp.: 175.2 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): absence of (C⚌O, NH2), 3020, 2890 (CH), 1605 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 6.38–7.33 (m, 4H, CH-aromatic), 7.07 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-4-thiazole), 7.72 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5-thiazole), 8.27 (s, 1H, CH⚌N), 9.84 (s, 1H, OH); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 173.0 (N⚌C—S), 162.2 (HC⚌N), 141.3, 115.9 (C-thiazolyl), 138.6, 132.1, 116.1 (C-aromatic); MS (m/z): 206.05 (M++2, 23.07%); Anal. calcd. for C10H8N2OS (204.04): C, 58.80; H, 3.95; N, 13.72; S, 15.70%; found: C, 58.92; H, 3.98; N, 13.75; S, 15.75%.

2.6.5 2-((thiazol-2-ylimino)methyl)phenol (13)

Brown powder; yield (90.00%), mp.: 165.8 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): absence of (C⚌O, NH2), 3320 (OH), 3010, 2880 (CH), 1610 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 10.25 (s, 1H, OH), 6.92–8.54 (m, 4H, CH-aromatic), 7.64 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-4-thiazole), 7.01 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5-thiazole), 8.21 (s, 1H, CH⚌N); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 160.8 (N⚌C—S), 154.3 (HC⚌N), 122.3, 119.5, 119.5 (C-aromatic); MS (m/z): 204.04 (M+, 55.01%); Anal. calcd. for C10H8N2OS (204.04): C, 58.80; H, 3.95; N, 13.72; S, 15.70%; found: C, 58.78; H, 3.75; N, 13.62; S, 15.68%.

2.6.6 N-(4-methoxybenzylidene)thiazol-2-amine (14)

Yellow powder; yield (87.07%), mp.: 102–103 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): absence of (C⚌O, NH2), 3020, 2990 (CH), 1610 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 6.35–7.31 (m, 4H, CH-aromatic), 7.60 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-4-thiazole), 7.21 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5-thiazole), 8.12 (s, 1H, CH⚌N), 3.38 (s, 6H, OCH3); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 161.5 (N⚌C—S), 156.0 (HC⚌N), 135.5, 120.6 (C-thiazolyl), 129.5, 128.4, 126.1 (C-aromatic), 62.9, 55.8 (OCH3); MS (m/z): 218.10 (M+, 60.0%); Anal. calcd. for C11H10N2OS (218.05): C, 60.53; H, 4.62; N, 12.83; S, 14.69%; found: C, 60.71; H, 4.66; N, 12.88; S, 14.72%.

2.6.7 N-(2-methoxybenzylidene)thiazol-2-amine (15)

Orange powder; yield (90.05%), mp.:150.9 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): absence of (C⚌O, NH2), 3009, 2890 (CH), 1605 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 6.37–7.21 (m, 4H, CH-aromatic), 7.60 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-4-thiazole), 7.21 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5-thiazole), 8.12 (s, 1H, CH⚌N), 3.33 (s, 6H, OCH3); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 161.5 (N⚌C—S), 156.0 (HC⚌N), 135.5, 120.6 (C-thiazolyl), 129.5, 128.5, 126.1 (C-aromatic), 62.9, 55.8 (OCH3); MS (m/z): 218.10 (M+, 66.03%); Anal. calcd. for C11H10N2OS (218.05): C, 60.53; H, 4.62; N, 12.83; S, 14.69%; found: C, 60.73; H, 4.74; N, 11.93; S, 13.99%.

2.6.8 N-(2,4-dimethoxy-benzylidene)-thiazol-2-yl-amine (16)

Orange powder; yield (87.50%), mp.:135.2 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): absence of (C⚌O, NH2), 3020, 2990 (CH), 1590 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 7.37–7.67 (m, 3H, CH-aromatic), 7.60 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-4-thiazole), 7.20 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5-thiazole), 9.01 (s, 1H, CH⚌N), 3.49 (s, 6H, 2CH3); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 173.6 (N⚌C—S), 167.1 (HC⚌N), 141.7, 119.7 (C-thiazolyl), 126.9, 124.5, 123.7 (C-aromatic), 62.8, 55.8 (OCH3); MS (m/z): 188.10 (M+, 88.01%); Anal. calcd. for C12H12N2O2S (248.06): C, 58.05; H, 4.87; N, 11.28; S, 12.91%; found: C, 59.04; H, 4.86; N, 11.29; S, 12.90%.

2.6.9 N-(2,3-dimethoxybenzylidene)thiazol-2-amine (17)

Yellow powder; yield (89.09%), mp.: 152.0 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): absence of (C⚌O, NH2), 3020, 2990 (CH), 1609 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 7.37–7.64 (m, 3H, CH-aromatic), 7.64 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-4-thiazole), 7.20 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5-thiazole), 9.29 (s, 1H, CH⚌N), 3.44 (s, 6H, 2CH3); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 172.6 (N⚌C—S), 167.1 (HC⚌N), 141.6, 119.8 (C-thiazolyl), 127.9, 124.5, 123.9 (C-aromatic), 62.8, 55.8 (OCH3); MS (m/z): 248.10 (M+, 100%); Anal. calcd. for C12H12N2O2S (248.06): C, 58.05; H, 4.87; N, 11.28; S, 12.91%; found: C, 59.05; H, 4.89; N, 11.30; S, 12.71%.

2.6.10 N-((2-methyl-1H-indol-3-yl)methylene)thiazol-2-amine (18)

Yellow powder; yield (86.34%), mp.:180.2 °C; FT‐IR (KBr, ν, cm‐1): absence of (C⚌O, NH2), 3010, 2980 (CH), 1600 (C⚌N); 1H NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 11.99 (s, 1H, NH-indolyl), 7.13–8.02 (m, 4H, CH-aromatic), 7.16 (d,1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-4-thiazole), 7.14 (d,1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5-thiazole), 8.04 (s, 1H, CH⚌N), 2.67 (s, 3H, CH3); 13C NMR: (400 MHz, DMSO‑d6, δ, ppm): 184.1 (N⚌C—S), 148.5, 111.4 (C-thiazolyl), 150.0 (HC⚌N), 135.3, 125.6, 122.6, 121.8, 119.9, 113.6 (C-aromatic); MS (m/z): 241.10 (M+, 66.09%); Anal. calcd. for C13H11N3S (241.07): C, 64.70; H, 4.59; N, 17.41; S, 13.29%; found: C, 64.55; H, 4.48; N, 17.38; S, 13.31%.

3 Results and discussion

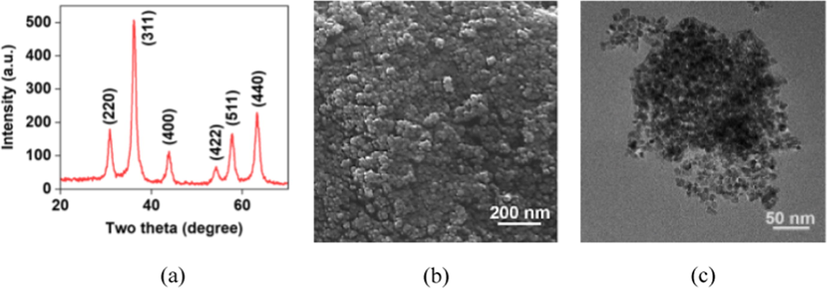

Ultrasmall nanomagnetic catalysts are prepared by the co-precipitation technique using Fe(II) and Fe(III) precursors using NH4OH as a reductant. The black powdered materials are collected by a magnet and non-magnetic materials are removed by washing with water repeatedly Scheme 1. The crystallinity of the prepared nanocatalyst is confirmed by the XRD signature. The XRD patterns of Fe3O4 display characteristic peaks at 2θ 30.2, 35.7, 43.1. 53.4, 57.1, and 63.2 indicate the formation of crystalline cubic (Fd3m) spinnel structure (JCPDS card no. 01-075-0449) (Shaikh et al., 2018; Pinna et al., 2005). Scanning electron microscopic (SEM) images demonstrated highly agglomerated particles with extremely smaller-sized particles with smooth surfaces. The higher surface interaction among the bared-surface ultrasmall nanoparticle leads to aggregation of the particles. Transmission electron microscopic (TEM) images show spherically shaped, uniformly distributed, nano-sized particles with 6–8 nm diameter, Fig. 1. The magnetic nature of the Fe3O4 NPs have been investigated and the results are shown below. The magnetization field (M−H) curve is recorded at room temperature using PMC Micromag 3900 model vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) equipped with a 1 Tesla magnet. The magnetic measurement of the Fe3O4 NPs shows 62.69 emu g−1, which is magnetic enough to separate the nanoparticles using a simple magnet at the bottom of the vessel after the reaction, Fig. 2.

X-ray diffraction(a) pattern of the Fe3O4 NPs, the SEM (b) and TEM (c) images show spherically shaped, uniformly distributed, nano-sized particles with 6–8 nm.

Magnetic hysteresis loops of Fe3O4 at room temperature with 1 Tesla magnet.

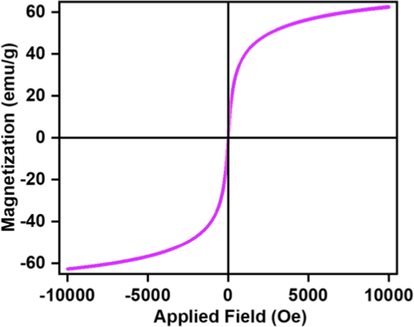

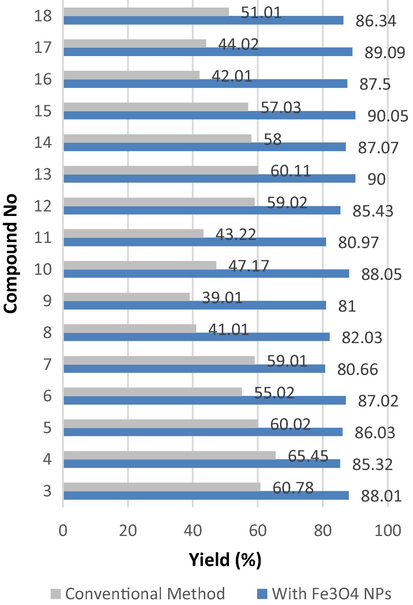

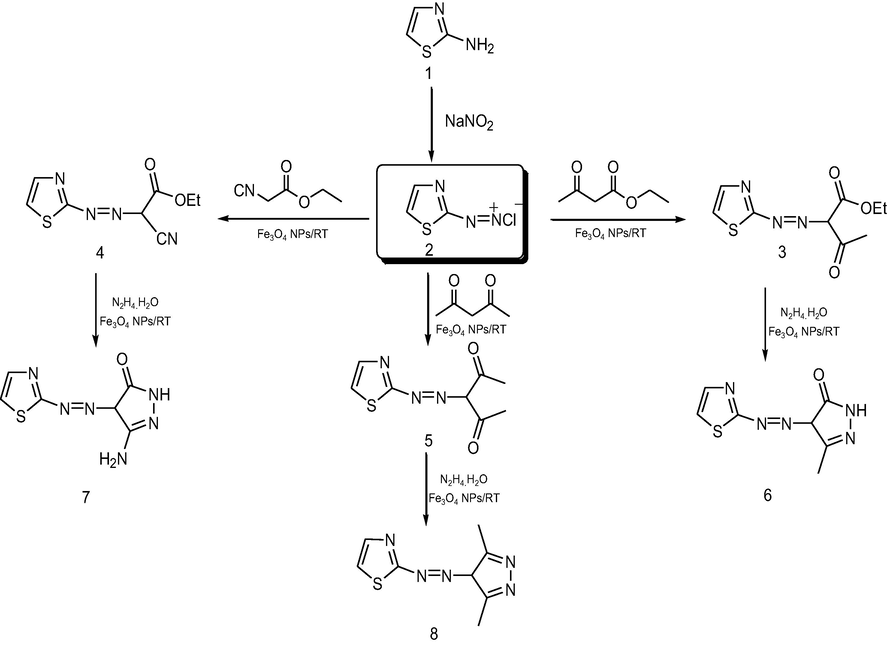

Using nanomagnetic catalysis is a modern technique for preparing organic compounds with high yield in a short time. Previously, we reported the diazotization of amino heterocyclic compounds followed by coupling with various active methylene compounds afford the corresponding coupling products by traditional method in ethanol under reflux for 2 h (Abrams, 2021). Herein, by using nanomagnetic catalysis (Fe3O4 NPs) in coupling the diazonium salt of 2-aminothiazole with various active methylene compounds, it seems the reaction is completed in 1 h. In addition to the short time reaction, it affords high yields compared to the conventional method Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 represents the pathway of preparing the target compounds. Coupling diazonium salt of 2-aminothiazole with ethyl acetoacetate, ethyl cyanoacetate, and acetylacetone in presence of a catalytic amount of Fe3O4 NPs at room temperature afforded the corresponding coupling products (3–5) respectively in 1 h. The reaction was monitored using the TLC technique. The prepared compounds were proved via their cyclization upon nucleophilic attack within by nucleophile hydrazine hydrate afforded the corresponding pyrazolyl derivatives (6–8) Scheme 2, these novel products were elucidated based on spectral data. The IR spectrum of (6) displayed absorption bands in the region 1750 cm−1 due to C⚌O, and at 3330, 3250 attributable for NH2 in (7). 1H NMR spectrum of (7) as an example, recorded new signals at δ 8.54, 8.26 ppm assigned for NH2 and NH, respectively. More details are required such as the absence of CN in 4 and more discussion for other products.

Reaction time (min) of products by used conventional method and with Fe3O4 NPs catalysis.

The effect of the yield (%) of products by used conventional methods and with Fe3O4 NPs catalysis.

Synthesistic pathway for pyrazole derivatives.

Moreover, the formation of Schiff bases from 2-aminothiazole was carried out upon one-pot method by treatment with a various aromatic aldehyde in presence of Fe3O4 NPs catalysis at room temperature Scheme 3., The reaction vanished in less time, and furnished high yield than the conventional method (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4).

Synthesistic pathway for Schiff bases derivatives.

The structures of these products were assigned using spectral analysis. IR for all compounds showed the absence of C⚌O and NH2.

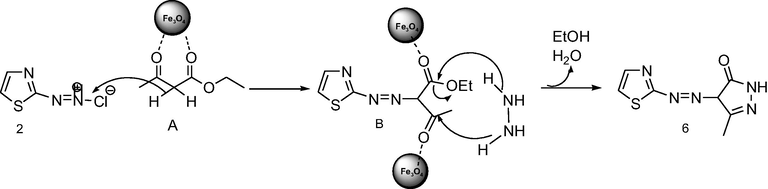

The plausible mechanism is consistent with the literature (Sadeghi et al., 2016; Zolfigol et al., 2012; Safari and Sadeghi, 2017). Preparation of intermediate given on proposed mechanism for the production of pyrazole derivatives in Scheme 4. Fe3O4 NPs as the catalyst can activate the active methylene compounds (A) through coordination to the oxygen atom of carbonyl group the catalyst can participate in the conversion of (B), Afterwards, Fe3O4 NPs promoted cyclization with hydrazine hydrate and dehydration gives pyrazole derivatives (6) (Polshettiwar and Varma, 2010). The nanocatalyst could be magnetically recovered from the reaction mixture during the workup procedure. Furthermore, the proposed mechanism for preparation of the Schiff base derivatives were carried out by activated aromatic aldehyde by Fe(III) of Fe3O4 NPs. Then nucleophilic attack of the amino group to carbonyl group of the activated aldehyde via the elimination of H2O to give Schiff base derivatives.

Plausible mechanism for synthesis pyrazole derivative by using Fe3O4 NPs.

4 Biological activity

All of the synthesized compounds were tested for their antimicrobial activities against five types of microorganisms including gram-negative and positive bacteria as well as fungus. The gram-negative bacteria include E. coli and P. aeruginosa while B. subtilis and S. aureus represented the gram-positive bacteria. C. albicans was the fungus used in the screening. Generally, the tested compounds exhibited better antibacterial activities with E.coli being the most sensitive bacteria. However, all of the tested compounds, except compound (7), showed no antifungal activity against C. albicans. Azo derivatives (1, 2) and (6–8) were slightly more potent than the Schiff bases with average zones of inhibition of 15.71 and 12.87 mm, respectively. Compound (6) showed the most potent antibacterial activity against E. coli whereas compound (9) was the least potent among the tested series of compounds. Unsubstituted benzene in Schiff base (9) was less potent than the substituted analogues. This may suggest that benzene substitution is beneficial for the activity. In addition, the antibacterial activity of the Schiff bases seems to be insensitive to the position and the nature of the substituents. The majority of the synthesized compounds did not exhibit antipseudomonal activity. Only compounds (6, 9, 11, 13) and (18) showed growth inhibition against P. aeruginosa with the most potent activity observed with compound (6). However, none of the compounds was superior to piperacillin. For the gram-positive bacteria, the antibacterial activity was more significant in Schiff base derivatives when compared to azo derivatives. None of the tested compounds showed superior activity to the positive control. Compound (7) was the only pyrazole derivative that showed activity against both B. subtilis and S. aureus whereas, compounds (11, 13) and (16) were the only Schiff bases that exhibited activities against both bacteria Table 1.

5 Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated an efficient, simple, efficient, and sable catalyst-Fe for the synthesis pyrazolyl derivatives and 2-aminothiazole Schiff bases derivatives of 2-aminothiazole by comparing showed best results of Fe3O4 NPs nanomagnetic catalysis and convention method. This method is quick, and avoids the use of toxic or heavy metals, high temperature, improved product yields, and easy workup procedure.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thanks Deanship of Scientific Research at Imam Abdulrhaman Bin Faisal University for financial support under projects no: (2019-132-sci), thanks for the co-workers and trenching at Basic and Applied Scientific Research Center, Imam Abdulrhaman Bin Faisal University, for making the spectral analyses, and for department of pharmaceutical chemistry and chemistry department at King Saud University to make the biological activity and nmr analysis for this research.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Alternative method for the synthesis of triazenes from aryl diazonium salts. Tetrahedron. 2021;89:132185.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microwave mediated cyclocondensation of 2-Aminothiazole into β-lactam derivatives: virtual screening and In vitro antimicrobial activity with various microorganisms. Int. J. ChemTech. Res.. 2010;2:956-964.

- [Google Scholar]

- Review of the synthesis and biological activity of thiazoles. Synthetic Comm.. 2021;51:670-700.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nano-Fe3O4@SiO2 supported ionic liquid as an efficient catalyst for the synthesis of 1,3-thiazolidin-4-ones under solvent-free conditions. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem.. 2015;398:58-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenethylthiazolethiouea (PETT) compounds, a new class of HIV-1 reverse transciptase inhibitors. 1. Synthesis and basic structure activity relationship studies of PETT analogs. J. Med. Chem.. 1995;38:4929-4936.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review on multi-component green synthesis of N-containing heterocycles using mixed oxides as heterogeneous catalysts. Arabian J. Chem.. 2020;13:1142-1178.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aminothiazoles: Hit to lead development to identify antileishmanial agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2015;102:582-593.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel hybrid compounds containing benzofuroxan and aminothiazole scaffolds: synthesis and evaluation of their anticancer activity. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2021;22:7497.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent developments of 2-aminothiazoles in medicinal chemistry. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2016;109:89-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic and biological activities of homoleptic palladium (II) complexes bearing the 2-aminobenzothiazole moiety. Polyhedron. 2021;199:115106.

- [Google Scholar]

- An overview on synthetic 2-aminothiazole-based compounds associated with four biological activities. Molecules. 2021;26:1449.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fe3O4 nanoparticles as an efficient and magnetically recoverable catalyst for the synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones under solvent free conditions. Chin. J. Catal.. 2011;32:1484-1489.

- [Google Scholar]

- Amiothiazoles part1-Syntheses and pharmacological evaluation of 4-[isobutylphenyl]-2-substituted aminothiazoles. Indan J. Chem. 2001:1279-1281.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design and synthesis of new energy restriction mimetic agents: Potent anti-tumor activities of hybrid motifs of aminothiazoles and coumarins. Sci. Rep.. 2020;10:2893.

- [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of new 2-aminothiazole scaffolds as phosphodiesterase type 5 regulators and COX-1/COX-2 inhibitors. RSC Adv.. 2020;10:29723-29736.

- [Google Scholar]

- Discovery of potent and orally active 3-alkoxy-5-phenoxy-N-thiazolyl benzamides as novel allosteric glucokinase activators. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2009;17:2733-2743.

- [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, and SOD activities of copper (II) complexes derived from 2-Aminobenzo thiazole derivatives. J. Coordination Chem.. 2017;70:242-260.

- [Google Scholar]

- Performance of 2-hydroxy-1-naphthaldehyde-2-amino thiazole as a highly selective turn-on fluorescent chemosensor for Al(III) ions detection and biological applications. J. Fluorescence. 2021;31:1041-1053.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2-(2-Hydrazinyl) thiazole derivatives: design, synthesis, and in vitro antimycobacterial studies. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2013;69:564-576.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic, acidic, ionic liquid-catalyzed one-pot synthesis of spirooxindoles. New J. Chem.. 2015;39:7293. ACS Comb. Sci. 15 (2013) 512

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and anticancer properties of 2-aminothiazole derivatives. Phosph. Sulfur Silicon Related Eleme.. 2021;196:444-454.

- [Google Scholar]

- Structure activity relationship of a series of 2-amino-4-thiazole-containing renin inhibitors. J. Med. Chem.. 1992;35:2562-2572.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetite nanocrystals: nonaqueous synthesis, characterization, and solubility. Chem. Mater.. 2005;17:3044-3049.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nano-organocatalyst: magnetically retrievable ferrite-anchored glutathione for microwave-assisted Paal-Knorr reaction, aza-Michael addition, and pyrazole synthesis. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:1091-1097.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of 2-aminothiazoles from methylcarbonyl compounds using a Fe3O4 nanoparticle-N-halo reagent catalytic system. RSC Adv.. 2016;6:64749-64755.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanostarch: a novel and green catalyst for synthesis of 2-aminothiazoles. Monatsh Chem.. 2017;148:745-749.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile hydrogenation of N-heteroarenes by magnetic nanoparticle-supported sub-nanometric Rh catalysts in aqueous medium. Catal. Sci. Technol.. 2018;8:4709-4717.

- [Google Scholar]

- Triazole incorporated thiazoles as a new class of anticonvulsants: design, synthesis, and in vivo screening. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2010;45:1536-1543.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and biological activity of 2-aminothiazoles as novel inhibitors of PGE2 production in cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2012;22:3567-3570.

- [Google Scholar]

- In vivo biological activity of antioxidative aminothiazole derivatives. Chem. Pharm. Bull.. 1996;44:2070-2077.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anti-HIV activity of aromatic and heterocyclic thiazolyl thiourea compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem.. 2001;11:523-528.

- [Google Scholar]

- Iodine-promoted efficient Synthesis of diheteroaryl thioethers via the integration of iodination/ condensation/cyclization/dehydration sequences. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2014;55:5544-5547.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic carbon nanotube-supportedimidazolium cation based ionic liquid as a highly stable nanocatalyst for the synthesis of 2-aminothiazoles. Appl. Organometal. Chem.. 2016;30:1043-1049.

- [Google Scholar]

- I2/CuO-catalyzed tandem cyclization strategy for one-pot synthesis of substituted 2-aminothiozole from easily available aromatic ketones/α, β-unsaturated ketones and thiourea. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:173-178.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nano-Fe3O4/O2: green, magnetic and reusable catalytic system for the synthesis of benzimidazoles. J. Chem.. 2012;65:280-285.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103878.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1