Translate this page into:

Synthesis, characterization and catechol oxidase biomimetic catalytic activity of cobalt(II) and copper(II) complexes containing N2O2 donor sets of imine ligands

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

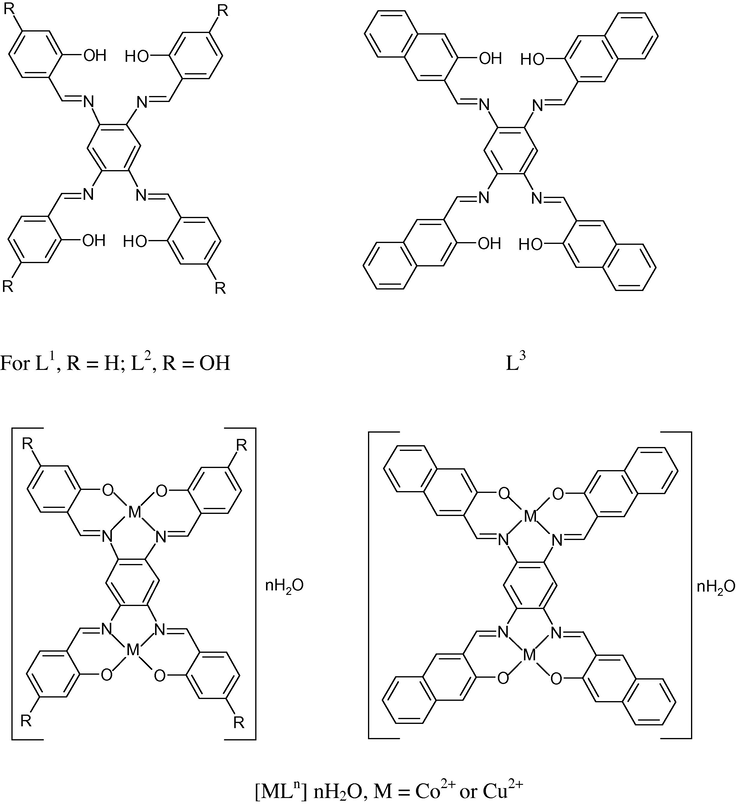

New tetradentate imine ligands are derived from Schiff base condensation in a 1:2 molar ratio of the 1,2,4,5-tetra-amino benzene with 2-hydroxy benzaldehyde, (L1), 2,4-dihydroxy benzaldehyde (L2) and 2-hydroxy naphthaldehyde (L3). These ligands react with CoCl2 and CuCl2 in refluxing ethanol to yield a series of cobalt(II) and copper(II) complexes of the type [M2IILn] nH2O. The structure of the obtained ligands and their metal(II) complexes were characterized by various physicochemical techniques, viz. elemental analysis, molar conductance, magnetic susceptibility measurements, thermal analysis (TGA & DTG), IR, electronic absorption and ESR spectral studies. Four-coordinate tetrahedral and square–planar structures were proposed for cobalt(II) and copper(II) complex species respectively. The ability of the synthesized complexes to catalyze the aerobic oxidation of 3,5-di-tert-butylcatechol (3,5-DTBC) to the light absorbing 3,5-di-tert-butylquinone (3,5-DTBQ) has been investigated. The results obtained show that all complexes catalyze this oxidation reaction and slight variations in the rate were observed. The probable mechanistic implications of the catalytic oxidation reactions are discussed.

Keywords

Synthesis

Characterization

Copper(II)

Cobalt(II)

Catecholase

Biomimetic

Catalytic activity

1 Introduction

A number of enzymes found in Nature are able to catalyze the activation of dioxygen from the atmosphere, and use it to affect a wide variety of remarkable reactions (Bugg, 2003, 1997; Kaim and Schwederski, 1995). Enzymes that are able to activate dioxygen include the oxidases, which use oxygen as an oxidant, and reduce dioxygen to hydrogen peroxide or water. One such enzyme is catechol oxidase (copper enzyme), which catalyzes the aerobic oxidation of o-diphenols (catechols) to the highly reactive o-quinones (Bugg, 2003, 1997; Kaim and Schwederski, 1995). Catechol oxidase, an enzyme ubiquitous in plants, insects and crustaceans (Hughes, 1999), is a type III copper protein containing a binuclear active site specializing in the two-electrons oxidation of a broad range of o-diphenols (catechols) to the highly reactive o-quinones (Solomon et al., 1992, 1996; Gerdemann et al., 2002) that auto polymerizes producing the pigment, melanin, which in turn, guards the damaged tissues against pathogens and insects among many of its protective functions (Deverall, 1961) Catechol melanin, the black pigment of plants (black banana and black sugar) is a polymeric product formed by the oxidative polymerization of catechol. Melanin exists in the hair, brain and eyes of Mammals and it is produced in pigment cells (ca. 1500 cell/mm2 in human) of the skin (Reedijk, 1993). Melanin plays a role in the prevention of organism damage in vivo by the absorption of ultraviolet light. Melanin is the major paramagnetic organic compound in vivo and acts as a scavenger of toxic radicals formed in vivo. The role of melanin in the brain is to assist in electron-transfer processes. Melanin in the eyes is excited by ultraviolet light to form tyrosyl radicals, which apparently play a role in visual perception (Reedijk, 1993). The formation of melanin does not always proceed rapidly with tyrosinase. This slow formation accounts for the phenomenon of sunburn of skin, which occurs when irradiation is faster than melanin formation. Some attempts have been reported on the development of catalysts which either promote the formation of melanin or retard the multistage processes of the oxidation reaction (Reedijk, 1993). The catechol oxidase enzyme thus plays an important role in disease resistance in Mammals, bacteria, fungi and higher plants.

The study of chemical models that mimic oxidases has been developed with the objective of providing bases for understanding enzymatic activity and to develop simple catalytic systems that under mild conditions, exhibit appreciable catalytic activity (Jorge and Bernt, 1997; Olivia et al., 2002; Lakshmi et al., 1996; Moya and Coichev, 2006; Girenko et al., 2002; Ramadan and El-Mehasseb, 1998; Ramadan et al., 2006, 2011; Hassanein et al., 2005; Simandi et al., 1995, 2003; Jung and Pierpont, 1994; Qiu et al., 2005; Kovala-Demertzi et al., 1998; Dilworth et al., 1977). Synthetic model studies on the reactivity of cobalt complexes toward the oxidation of ascorbic acid and phenolic substrates, implicate both structural and electronic factors as being responsible for the catalytic activity (Jorge and Bernt, 1997; Olivia et al., 2002; Lakshmi et al., 1996; Ramadan et al., 2006; Yang and Vigee, 1991).

Therefore, the structural and electronic properties of the synthesized cobalt(II) and copper(II) imine complexes are of interest. Synthesis, characterization and catecholase biomimetic catalytic activity of the reported cobalt(II) and copper(II) imine complexes as functional catecholase models are the subjects of the present article.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

Cobalt(II) and copper(II) salts, 1,2,4,5-tetra-amino benzene, 2-hydroxoy benzaldehyde, 2,4-dihydroxy benzaldehyde and 2-hydroxy naphthaldehyde were procured from Aldrich. All chemicals used are of high purity analytical grade.

2.2 Synthesis of imine ligands

The reported imine ligands were prepared by the following procedure. To a solution of 1,2,4,5-tetra-amino benzene (0.1 mol) was added a solution of the corresponding carbonyl compound (0.2 mol) in absolute EtOH (50 ml). The reaction mixture was stirred and boiled under reflux for 2 h. On cooling, the solid product that precipitated was removed by filtration and washed with cold EtOH. The crude product was recrystallized from hot EtOH to give dark red fine powders, which were filtered off washed with cold EtOH and finally dried in vacuum over CaO. The purity of these ligands was checked by elemental analysis, constancy of the melting point, and spectral measurements.

2.3 Synthesis of the metal chelates

A hot solution of cobalt(II) or copper(II) chloride (0.02 mol) in absolute EtOH (50 ml) was added to a boiling solution of the imine ligand (0.01 mol) in absolute EtOH (50 ml) and the reaction mixture was refluxed for 4 h. The reaction mixture was then allowed to stand at room temperature overnight, whereby a microcrystalline product was formed. All complexes thus obtained were filtered off, washed several times with EtOH, then Et2O, and finally dried in evacuated desiccators over anhydrous CaO.

2.4 Physical measurements

The IR spectra were recorded using KBr disks in the 4000–200 cm−1 range on a Unicam SP200 spectrophotometer. The electronic absorption spectra were obtained in methanolic solution with a Shimadzu UV-240 spectrophotometer. Magnetic moments were measured by Gouy's method at room temperature. ESR measurements of the polycrystalline samples at room temperature were made on a Varian E9 X-band spectrometer using a quartz Dewar vessel. All spectra were calibrated with DPPH (g = 2.0027). The specific conductance of the complexes was measured using freshly prepared 10−3 M solutions in electrochemically pure MeOH or DMF at room temperature, using an YSI Model 32 Conductivity meter. The thermogravimetric measurements were performed using a Shimadzu TG 50-Thermogravimetric analyzer in the 25–800 °C range and under an N2 atmosphere. Elemental analyses (C, H, and N) were carried out at the Micro analytical Unit of Cairo University.

2.5 Catechol oxidase biomimetic catalytic activity

A mixture of 1.0 ml of 3,5-di-tert-buty1catehol (3,5-DTBC) solution (30 mM) in methanol and 1.0 ml of metal complex solution (∼3 mM) in DMF was placed in a 1 cm path length optical cell containing 1.0 ml of DMF in a spectrophotometer. The final concentration of reaction mixture is catechol (20 mM) and complex (l mM). The formation of 3,5-di-tert-butyl-catequinone (3,5-DTBQ) was followed by observing the increase of characteristic quinone absorption band at 400 nm. For each set of observation, a curve of concentration of 3,5-DTBQ formed (calculated by using corresponding ε value) versus time was plotted and initial rates were calculated by drawing a tangent to curve at t = 0 and finding its slope. After this initial fast phase, the average rate of reaction was also calculated. The above described experiment was repeated under two sets: (i) in the reaction mixture the concentration of catalyst was varied (0.5, 1.0, 1, 2.0 mM) and concentration of DTBC was kept constant at 20 mM. (ii) Concentration of DTBC was varied (10, 20, 30, 40 mM) and concentration of catalyst was kept fixed at 1.0 mM. For each set of data initial rates were calculated and graphs of rate versus concentration of catalyst and rate versus concentration of catechol were plotted.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 General

The imine ligands used in this study are derived from Schiff base condensation in a 1:1 molar ratio of the 1,2,4,5-tetra-amino benzene with 2-hydroxy benzaldehyde, (L1), 2,4-dihydroxy benzaldehyde (L2) and 2-hydroxy naphthaldehyde, (L3), as shown in Scheme 1. Interaction of cobalt(II) or copper(II) salts with the title ligands in 1:2 (L:M) molar ratio in ethanolic solution produces a series of metal chelates (1–6) in an appreciable yield. The pure products were characterized by the elemental analysis and spectroscopic techniques chemical analysis and some physical properties of the pure isolated cobalt(II) and copper(II) complexes are listed in Table 1. The analytical results demonstrate that all the complexes have (2:1) metal–ligand stoichiometry. The microcrystalline chelates are various shades of brown and they are stable as solid or in solution under the atmospheric conditions. These pure complexes are freely soluble in DMF, DMSO and completely insoluble in water and the common organic solvents. The molar conductivities obtained in DMF solution demonstrate that these complexes are non-electrolytes with ΛM values lying in the 23.64–41.66 Ω−1 cm2 mol−1 range. This fact confirms the analytical results and the accordance of the suggested chemical formulae of these metal chelates.

Structure of L1, L2, L3 and their complexes of cobalt(II) and copper(II) ions.

Complex

Color

Found (calcd.)

C

H

N

M

1

[Co2L1] 3H2O

Deep red

53.98 (53.34)

3.89 (3.55)

8.03 (8.30)

16.97 (17.45)

2

[Co2L2] 4H2O

Red

47.57 (47.56)

3.63 (3.43)

7.18 (7.40)

15.20 (15.56)

3

[Co2L3] 5H2O

Dark red

60.66 (60.94)

3.88 (3.97)

6.17 (6.18)

13.43 (13.00)

4

[Cu2L1] 5H2O

Brown

49.66 (49.99)

3.85 (3.88)

7.49 (7.78)

17.17 (17.64)

5

[Cu2L2] 3H2O

Faint Brown

48.86 (48.62)

3.59 (3.20)

7.17 (7.49)

16.36 (16.98)

6

[Cu2L3] 2H2O

Yellowish brown

63.90 (64.10)

3.55 (3.48)

6.29 (6.50)

14.40 (14.75)

3.2 Mode of bonding

Important vibration bands of the free ligands and their cobalt(II) and copper(II) complexes along with their assignments, which are useful for determining the mode of coordination of the ligands, are given in Table 2. The free imine ligands exhibit medium bands in the region 3412–3541 cm−1 assigned to the OH, stretching (Dilworth et al., 1977). This band disappears on complexation, indicating the replacement of the phenolic hydrogen by the metal ion. Several significant changes, with respect to the spectra of the ligands, are observed in the spectra of the corresponding metal complexes. A new band appearing in the 1247–1289 cm−1 region in the spectra of complexes was assigned to the ν(C–O) of the phenolate mode (Ramadan and Issa, 2005; Vcrgopoulos et al., 1993). The bonding of phenolate oxygen to the metal ion is further supported by the appearance of new absorption band at 510–550 cm−1, which is not observed in the spectra of the free ligands. This band is characteristic of ν(M–O) stretching Nakamoto, 1986.

Compound

ν(O–H)

ν(C⚌N)

ν(C–O)

ν(M–O)

ν(M–N)

L1

2846b

1612

1200

…

…

[CoL1]

1595

1228

513

440

[CuL1]

1585

1218

511

456

L2

2335

1600

1210

…

…

[CoL2]

1595

1220

517

455

[CuL2]

1590

1242

519

467

L3

2362

1600

1217

…

…

[CoL3]

1595

1230

507

446

[CuL3]

1590

1237

513

449

In all complexes, the azomethine band of the Schiff-base linkage undergoes a remarkable shift toward lower wave numbers (5–27 cm−1) compared with its position in the spectra of the free ligands, as a consequence of coordination of the nitrogen atom to the metal ion (Maroney and Rose, 1984). Coordination of the azomethine group to the metal ion is expected to reduce the electron density on the Schiff-base linkage (C⚌N), causing a reduction in its vibrational frequency. However, the corresponding absorption band appears to be slightly shifted to lower frequency in complexes [CoL3] and [CuL3] in agreement with other reported results (Ramadan and Issa, 2005). Coordination of the nitrogen atoms to M2+ ion is further supported by the appearance of a new absorption band at 440–467 cm−1 range which are assigned to the ν(N–M) Nakamoto, 1986.

The spectra of all complexes reveal an absorption band in the region 1200–1220 cm−1 characteristic to the α-diimine moiety of the metal chelates (Rai and Prased, 1994). This finding has been observed in several α-diimine containing tetraazamacrocyclic Schiff-base complexes (Maroney and Rose, 1984).

For all complexes, broad bands present in the range 3450–3550 cm−l, assignable to ν(OH), clearly confirm the presence of surface and crystalline water (Nakamoto, 1986; Ferraro, 1971). Since vibrational modes such as wagging, twisting and rocking activated by coordination to the metal have not been found in the expected ranges, it appears that coordinated water is not present. These results are consistent with the thermogravimetric studies, using TG and DTG techniques. In fact this water is lost in the 42–100 °C range.

3.3 Electronic absorption spectra

The electronic absorption spectra of the reported ligands and their cobalt(II) and copper(II) complexes were measured at room temperature in DMF solution and the corresponding data are given in Table 3. The spectra of the free ligands give rise to high energy absorption below 300 nm, due to π → π∗ transition of the naphthyl and phenyl moieties. The strong absorption band at ≈ 310 nm of the uncoordinated ligands is assignable to the n → π∗ transition originating from the azomethine linkage of the Schiff base moiety (West et al., 1988, 1991). The absorption spectral data in Table 3 show that there is a significant change in the energy of π → π∗ and n → π∗ band on complexation. The band maximum in the spectra of chelates is shifted to lower frequencies relative to those in the free ligands. This bathochromic shift may result from the extended conjugation in the ligand forced by the chelated metal ion (Ismail, 1997; Gang and Yuan, 1994).

Complex

λmax (cm−1)

(F)

(P)

[CoL1]

16,384

19,186

35,097

40,816

[CoL2]

16,772

19,230

37,735

40,596

[CoL3]

15,897

18,999

37,027

38,461

[CuL1]

14,525

17,490

18,035

27,777

38,314

[CuL2]

15,051

17,062

19,450

28,169

39,215

[CuL3]

14,839

16,524

18,976

27,624

38,542

In the low energy region the spectra of cobalt(II) complexes, 1–3, exhibit two low-intensity bands, the 4A2 → 2T1 (F) (ν2) and 4A2 → 2T1 (P) (ν3) transitions respectively, supporting the tetrahedral geometry (Gaber et al., 2008; Lever, 1970) second of which is present as a shoulder in the 18,999–19,230 cm−1 range.

The spectra of the four-coordinate complexes 4, 5 and 6 display three electronic absorptions in the 14,525–15,051, 16,524–17,490 and 18,035–19,450 cm−1 ranges which can unambiguously be assigned to the three spin allowed transitions: 2B1g → 2B2g, 2B1g → 2A1g and 2B1g → 2Eg, respectively (Lever, 1970; Singh et al., 2007; Li et al., 2008). These spectral features support the square–planar geometry around copper(II) center (Khan et al., 2009; Ramadan et al., 2005).

3.4 ESR-spectra and magnetic moment measurements

The effective magnetic moments (BM) measured at room temperature indicate that the reported cobalt(II) and copper(II) complexes are magnetically dilute (Dutla and Syamal, 2007). The magnetic moments of the three complexes namely [CoL1], [CoL2] and [CoL3] are 4.1, 3.98 and 4.3 BM respectively. These values lie in the range expected for the four-coordinated tetrahedral cobalt(II) complexes of a high spin type, i.e., these magnetic moments are in agreement with the spin only value for three unpaired electrons (Dutla and Syamal, 2007). The data Table 4 reveal that the observed magnetic moments fall in the range 1.88–2.10 BM These values are close to the spin only (S = 1/2) behavior of 1.73 BM for d9 configuration and reflect the absence of any metal-metal interaction with the neighboring molecules. This finding is further confirmed from the clear resolution of the ESR spectra.

Complex

g||

gav

G

μeff (BM)

[CuL1]

2.222

2.055

2.107

4.036

2.24

[CuL2]

2.235

2.055

2.115

4.273

1.93

[CuL3]

2.255

2.061

2.126

4.180

1.88

The X-band ESR spectra of the polycrystalline samples of the reported copper(II) complexes 4, 5 and 6 were recorded at room temperature. The g|| and values were computed from the spectrum using DPPH (g = 2.0027) as “g” marker. Based on the g-values Table 4, the copper(II) ion in these complexes is in an axial distorted ligand field. Since the g|| and values are close to 2 and g|| > suggesting a tetragonal distortion around the copper(II) ion corresponding to the elongation along the four fold symmetry Z-axis (West et al., 1995). However, all complex species show parameters which are characteristic of the axial symmetry with the elongation of axial bonds and the orbital is the ground state. Elongated square planar or distorted square-pyramidal stereochemistries would be consistent with these data, but trigonal-pyramidal involving compression of the axial bonds should be excluded (Fernandes et al., 2007).The spectra of most complexes show one signal and the absence of the hyperfine splitting may be attributed to a strong dipolar interaction between the copper(II) ions in the unit cell. The analysis of the spectra gives the trend: g|| > > ge (2.0023), which supports that the orbital is the ground state (West et al., 1995). It is well known that for an ionic environment g|| is normally 2.3 or larger, but for covalent environment g|| is less than 2.3. The observed g|| value for the investigated complexes is less than 2.3; consequently the coordination environment is covalent. The trend g|| (2.222–2.255) > (2.055–2.068) observed for all complexes was found to be in accordance with the criterion of Kivelson and Neiman implying the presence of the unpaired electron that is localized in orbital for copper(II) ion characteristic of the axial symmetry (Kivelson and Neiman, 1961). Tetragonal elongated structure is confirmed for the reported copper(II) complexes.

The value of the exchange interaction (G) between the copper(II) centers in a polycrystalline solid has been calculated using the relation G = (g|| − 2.0023)/( − 2.0023) (Raman et al., 2005). According to Hathaway et al. if the G > 4, the exchange interaction is negligible, while G < 4 indicates considerable exchange interaction in the solid complexes (Hathaway and Billing, 1970). The data in Table 4 reflect the absence of any exchange interaction between copper(II) centers in the solid complexes in accordance with the results of magnetic moment measurements.

Great effort to grow crystals of these metal imine complexes suitable for X-ray structure determination so far has been unsuccessful. However, based on the composition of these complexes, their IR and electronic spectra, conductivity measurements, magnetic studies (vide infra), these complexes are proposed to have a tetrahedral geometry for cobalt(II) ion and a square-planar environment in the case of copper(II) species, as shown in Scheme 2. The plausible structure of these complexes is further illustrated by the following thermal studies.

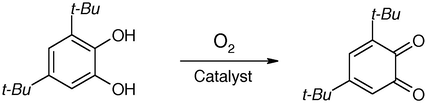

Catalytic aerobic oxidation of 3,5-di-tert-butylcatechole (3,5-DTBC) to 3,5-di-tert-butylquinone (3,5-DTBQ).

3.5 Thermal studies

3.5.1 Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA–DTG)

The content of a particular component in a complex changes with its composition and structure. Thus, the content of such components can be determined based on the mass losses of these components in the thermogravimetric plots of the complexes. Therefore, in order to throw more insight into the structure of the reported complexes, thermal studies on the solid complexes using the thermogravimetric (TG) and differential thermogravimetric (DTG) techniques were performed. The TG and DTG thermograms of complexes 1–6 were recorded under a dynamic N2 atmosphere and some of the important characteristics, e.g. the decomposition stages temperature ranges, maximum decomposition peaks DTGmax, percentage losses in mass, and the assignment of decomposition moieties are listed in Table 5. The TG curve was redrawn as mg mass loss versus temperature and typical TG and DTG curves for complexes [CoL3] 5H2O and [CuL3] 2H2O are represented in Fig. 1.

Complex

Temperature range °C

DTG T °C

% Weight loss found (calcd.)

Species formed

[Co2L1] 3H2O

42–100

42.30

07.37 (07.47)

[CoL1]

100–600

568.19

68.60 (69.87)

Co2O3

[Co2L2] 4H2O

45–95

49.44

09.51 (09.51)

[CoL2]

95–750

571.62

69.98 (70.45)

Co2O3

[Co2L3] 5H2O

50–100

60.94

09.21 (09.93)

[CoL3]

100–750

687.69

72.84 (73.18)

Co2O3

[Cu2L1] 5H2O

50–100

68.56

10.97 (12.49)

[CuL1]

100–650

525

64.86 (65.48)

CuO

[Cu2L2] 3H2O

60–100

45

05.57 (07.42)

[CuL2]

100–600

460

72.84 (73.05)

CuO

[Cu2L3] 2H2O

60–100

45

04.57 (04.81)

[CuL3]

100–650

450

78.84 (79.58)

CuO

![Thermogravimetric (TGA/DTG) curves of [CoL3] 5H2O and [CuL3] 2H2O complexes.](/content/184/2016/9/2_suppl/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2012.02.007-fig3.png)

Thermogravimetric (TGA/DTG) curves of [CoL3] 5H2O and [CuL3] 2H2O complexes.

The thermogravimetric curves of complexes 1–6 are similar and show two stages of decomposition within the temperature range of ambient temperature to 750 °C. The thermal decomposition occurs in two stages within the temperature range 45–750 °C. The first stage shows the dehydration process which starts at 45 °C and comes to an end at 100 °C. The weight losses are corresponding to the volatilization of 2–5 surface and lattice water molecules and the activation energy values are in the 26.87 and 55.22 kJ mol−1 range. The second thermal degradation stage comprises several successive and unresolved steps within the temperature range 100–750 °C, with the maximum decomposition peaks DTGmax lying at 723 and 960°K range. The corresponding mass loses are due to the complete decomposition and removal of the organic ligand. The mass losses in this stage are in good agreement with calculated mass losses and the final product is quantitatively proved to be anhydrous metallic oxide Co2O3 for cobalt(II) complexes and CuO for copper(II) chelates. The observed overall weight loss amounts Table 5, are in good agreement with the calculated values based on the suggested formulae of these complexes and consistent with the thermal material decomposition and elimination of the complex molecule contents. The activation energies of the thermal dehydration and pyrolytic processes of these complexes are 26.87–55.22 and 111.15–205.53 kJ mol−1 respectively.

3.5.2 Kinetic aspects

The kinetic activation parameters of the thermal decomposition of the investigated cobalt(II) and copper(II) imine complexes, namely the activation energy E∗ in kJ mol−1 is evaluated graphically by using the Coats–Redfern method (Coats and Redfern, 1964): where α is the fraction of the sample decomposition, T the temperature, A the pre-exponential factor, g(α) the kinetic mechanism function, R the gas constant, β the heating rate and E the activation energy.

In the present investigation log[g(α)/T2] plotted against 103/T gives straight lines whose slope and intercept are used to evaluate the kinetic parameters ΔH∗ and ΔG∗ by the least squares method. The goodness of fit is checked by calculating the correlation coefficient.

The entropy of activation (ΔS∗) was computed by employing the following relation: ΔS∗ = R ln(Ah/KBTs).

Where k is the Boltzmann's constant, Ts the DTG peak temperature, h the Plank’s constant and R the gas constant. All the calculations were done with the help of a computer program.

The thermodynamic parameters of the TGA studies permit coordinated and uncoordinated water molecules, to distinguish. The TG curves of the reported complexes demonstrated that, two thermal processes can be observed: (a) dehydration and (b) pyrolytic decomposition.

3.5.2.1 Dehydration processes

The first stage that takes place in thermal decomposition of the complexes 1–6 is assigned to the dehydration processes of the outer coordination sphere water molecules, i.e., the surface and lattice water molecules. The data in Table 6 reveal that, the activation energy (E∗) and the dehydration enthalpy (ΔH∗) values depend on the number of water molecules present in complex molecule. The first weight loss calculations obtained from the TGA curves of the complexes 1–6 are assigned as dehydration of the physically adsorbed water molecules. The difference in the thermal data (E∗, ΔH∗) is attributed to the difference in water content that exists per complex molecule. E∗, ΔH∗ and ΔG∗ are in kJ mol−1, ΔS∗ in J K mol−1.

Complex

Stage

T (K)

A (s−1)

E∗

ΔH∗

ΔS∗

ΔG∗

[Co2L1] 3H2O

1

315

0.4529

026.87

023.95

−0.2546

124.21

2

841

11.740

111.15

108.23

−0.2326

274.13

[Co2L2] 4H2O

1

332

8.790

38.900

34.04

−0.2300

113.63

2

844

11.401

186.96

181.54

−0.2349

294.94

[Co2L3] 5H2O

1

333

3.840

55.22

52.30

−0.2353

106.77

2

960

10.510

205.53

202.61

−0.2337

393.35

[Cu2L1] 5H2O

1

341

1.4200

54.830

51.920

−0.2451

118.82

2

798

10.610

204.35

201.44

−0.2335

389.70

[Cu2L2] 3H2O

1

319

10.110

37.82

34.90

−0.2263

118.02

2

733

1.917

156.51

153.59

−0.2472

248.74

[Cu2L3] 2H2O

1

313

10.110

28.82

25.90

−0.2263

108.02

2

723

1.917

126.51

123.59

−0.2472

228.74

3.5.2.2 Pyrolytic decomposition

Once dehydrated, the investigated cobalt(II) and copper(II) complexes are subjected to decomposition of nearly the same manner and all ended with the formation of metal oxide. The larger E∗ and ΔH∗ values for the dehydrated complex species namely [CoL3] and [CuL1] compared to the other complexes may be due to strong thermal agitation accompanying the successive thermal elimination of organic ligand. This points to the existence of these complexes in an associated structure and supports the proposed dimeric forms.

For all dehydrated complexes the thermodynamic parameter values of the pyrolytic decomposition stages were found to be higher than that of the dehydration stage which indicates that the rate of the pyrolytic stage is lower than that of the dehydration stage. This may be attributed to the structural rigidity of the coordinated imine ligand as compared with H2O which requires lower energy for its rearrangement before undergoing any compositional changes associated with its elimination. The negative values of ΔS∗ for all complexes (Table 6), indicate that during thermal decomposition stages the resulting transition states (the activated complexes) are more orderly, i.e. in a less random molecular configuration, than the reacting complexes. The data in Tables 6 and 7 reveal also that the values of the free energy ΔG∗ increase for the subsequent decomposition stages due to increase in the values of TΔS from one step to another which override the value of ΔG∗. This increase reflects that the rate of the subsequent removal of the organic ligand moiety is lower than that of the surface and lattice water molecules. The positive values of ΔH∗ means that the thermal decomposition processes are endothermic. Complexes details are as listed in Table 1.

Complex

kcat (h−1)

Km × 102 (M)

Vmax × 104 (MS−1)

1

270.00

9.76

4.50

2

222.00

8.57

3.70

3

150.00

5.47

2.50

4

390.00

10.92

6.50

5

352.20

10.03

5.87

6

187.20

6.14

3.12

3.6 Catechol oxidase biomimetic catalytic activity studies

The catechol oxidase biomimetic catalytic activity of the reported cobalt(II) and copper(II) imine complexes, as functional models has been determined by the catalytic oxidation of catechols (Selmeczi et al., 2003; Neves et al., 2002; Seneque et al., 2002; Belle et al., 2007) (Scheme 2). Among the different catechols used in catechol oxidase model studies, 3,5-di-tert-butylcatechol (3,5-DTBC) is the most widely used substrate for catecholase activity of tyrosinase (Monzani et al., 1998, 1999; Bolus and Vigee, 1982; Zippel et al., 1996). Its low redox potential for the, quinone-catechol couple, makes it easy to be oxidized to the corresponding quinone 3,5-DTBQ, and its bulky substituents, make further oxidation reactions such as ring opening remote. The product 3,5-di-tert-butyl-o-quinone (3,5-DTBQ), is considerably stable and exhibits a strong absorption at λmax = 400 nm (ε = 1900 M−1 cm−1 in MeOH) (Gentschev et al., 2000). Therefore, activities and reaction rates can be determined using electronic spectroscopy by following the appearance of the characteristic absorption of the 3,5-di-tert-butyl-o-quinone (3,5-DTBQ). The reactivity studies were performed in DMF solution because of the solubility of the complexes as well as the substrate. When the oxidation reaction was allowed to continue for 48 h at room temperature, only o-quinone was detected. The exceptionally high stability found for o-quinone at room temperature suggests that a single reaction pathway is being followed and that the o-quinone produced does not undergo further oxidative cleavage.

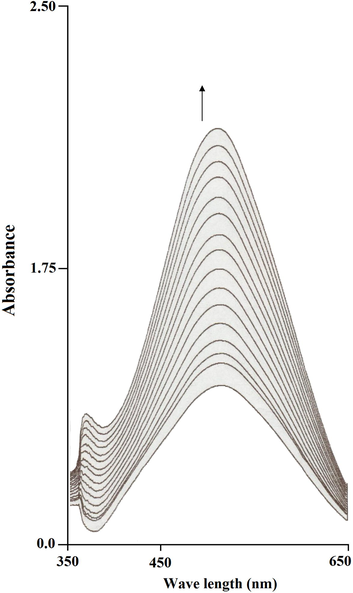

3.6.1 Initial rate studies

Prior to a detailed kinetic study, it is necessary to get an estimation of the ability of the complexes to oxidize catechol. The kinetic data were determined by the method of initial rates by monitoring the growth of the λ at 400 nm band of the product 3,5-DTBQ, formed due to aerobic oxidation of 3,5-DTBC in the presence of metal(II) complexes. For this purpose 1 × 10−4 M solutions of 1–4 in DMF were treated with 100 equivalent of 3,5-DTBC in the presence of air. The absorbance was continually monitored at λ = 400 nm over the first 20 min and the case for complex [CuL1] is presented in Fig. 2. Initial rates for 1–6 were determined from the slope of the tangent to the absorbance versus time curve at t = 0. Fig. 2 shows the time course of the reaction of [CuL1] with, 5-DTBC. The first apparent result is that the reactivity of the complexes does not differ significantly from each other. Under identical conditions, without the presence of a possible catalyst no significant quinone formation was observed. Important is the comparison of the reactivity of [Cu2L3] and [Co2L3] with the other reported complexes that displayed lower reactivity. The low catechol oxidase activity of [Cu2L3] and [Co2L3] may be attributed to the steric effect of the naphthalene moiety in L3. For all complexes, the reactivity order is: [Cu2L1] ⩾ [Cu2L2] > [Co2L1] ⩾ [Co2L2] > [Cu2L3] ⩾ [Co2L3]. The observed difference in the catalytic activity of these catechol oxidase functional models could be ascribed to the values of the redox potential of the couple M2+/M+ during the catalytic cycle where the metal ion behaves as a redox center.

Monitoring the increase in the characteristic o-quinone absorption band at 390 nm as a function of time.

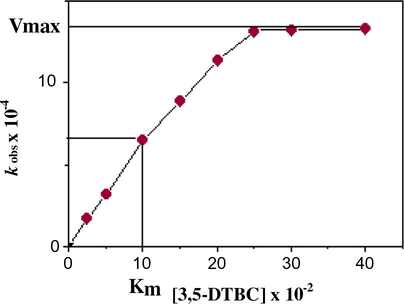

To determine the dependence of the rates on the substrate concentration, solutions of the complexes 1–6 were treated with increasing amounts of 3,5-DTBC. A first order dependence was observed at low concentrations of the substrate, whereas saturation kinetics was found for all complexes 1–6 at higher concentrations and a representative plot is given in Fig. 3. A treatment on the basis of the Michaels–Menten model, originally developed for enzyme kinetics, was applied. In our case we can also propose a pre-equilibrium of free complex and substrate on one hand, and a complex-substrate adduct on the other hand. The irreversible conversion into complex and quinone can be imagined as the rate-determining step. Although a much more complicated mechanism may be involved, the results show this simple model to be sufficient for a kinetic description.

The dependence of the reaction rate on the 3,5-DTBC concentration for the aerial oxidation reaction catalyzed by complex 4 (1 × 10−4 M) at 296 K.

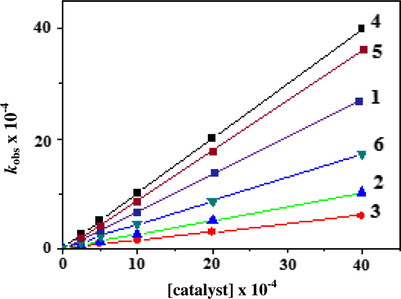

The dependence of the reaction rate on the catalyst concentration is illustrated in Fig. 4, and from it one can see that at constant concentration of DTBC, O2 and a variation amount of the catalyst, the initial rate is linearly dependent on the square of the catalyst concentration. As the curves in Fig. 4 pass through the origin i.e. without intercept, it can be stated that there is no measurable rate of oxidation in the absence of the catalyst. It has been reported earlier that for a single mononuclear complex, the rate of DTBC oxidation depends linearly on the copper(II) complex concentration in accordance with our results in this study.

A comparison of the dependence of kobs on catalyst concentration for the aerial oxidation of 3,5-DTBC in DMF at 296 K.

Based on the above kinetic and catalytic investigations a probable catalytic reaction sequence can be represented as follows:

4 Conclusion

The present study describes the syntheses and characterization of a series of cobalt(II) and copper(II) complexes with the tetradentate imine ligands. The characterization of the synthesized compounds was achieved by several physicochemical methods namely, elemental analysis, thermal studies, magnetic, electrochemical and spectroscopic techniques. The reported complexes contain a four – coordinated metal(II) ion in an oxygen and nitrogen rich environment in the tetrahedral stereochemistry for cobalt(II) ion and square – planar geometry in the case of copper(II) complexes. The catecholase biomimetic catalytic activity of the synthesized complexes has been investigated. The results obtained show that all the complexes catalyze the aerobic oxidation of catechol to the corresponding light absorbing o-quinone.

References

- C. R. Chim.. 2007;10:1.

- Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1982;67:19.

- An Introduction to Enzyme and Coenzyme Chemistry, 1st Edit. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1997. Ch. 3

- Tetrahedron. 2003;59:7075.

- Nature. 1964;201:68.

- Nature. 1961;189:311.

- J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1977:849.

- Elements of Magnetochemistry (1st ed.). New Delhi: Affiliated East-West Press; 2007.

- J. Inorg. Biochem.. 2007;101:849.

- Low Frequency Vibrations of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds. New York: Plenum; 1971.

- J. Mol. Struct.. 2008;875:322.

- Trans. Met. Chem.. 1994;19:218.

- Inorg. Chim. Acta. 2000;300:442.

- Acc. Chem. Res.. 2002;35:183.

- Russ. Chem. Bull. International Edit.. 2002;51(7):1236.

- J. Mol. Catal.. 2005;240:22.

- Coord. Chem. Rev.. 1970;5:143.

- Immunogenetics. 1999;49:106.

- Trans. Met. Chem.. 1997;22:565.

- J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans.. 1997;20:3793.

- Inorg. Chem.. 1994;33:2227.

- Bioinorganic Chemistry: Inorganic Elements in Chemistry of Life. New York: Wiley; 1995. Ch. 3

- Spectrochim. Acta. 2009;A73:622.

- J. Chem. Phys.. 1961;35:149.

- J. Inorg. Biochem.. 1998;69(4):223.

- J Inorg. Biochem.. 1996;61:155.

- Inorganic Electronic Spectroscopy. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1970.

- J. Magn. Magn. Mater.. 2008;292:418.

- Inorg. Chem.. 1984;23:2252.

- Inorg. Chem.. 1998;37:553.

- Inorg. Chem.. 1999;38:5359.

- J. Braz. Chem. Soc.. 2006;17(2):364.

- Infrared and Raman Spectra of Inorganic and Coordination Compounds. New York: Wiley; 1986.

- Inorg. Chem.. 2002;41:1788.

- Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.. 2002;8:2007.

- Polyhedron. 2005;24(13):1617.

- Monatsh Chem.. 1994;125:385.

- Transition Met Chem.. 1998;23:183.

- Trans. Met. Chem.. 2005;30:471.

- Transition Met Chem.. 2006;31:730.

- J. Mol. Struct.. 2011;1006:348.

- Central Eur. J. Chem.. 2005;3:537.

- Reedijk J., ed. Bioinorganic Catalysis. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1993.

- Coord. Chem. Rev.. 2003;245:191.

- Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002:2007.

- Inorg. Chem.. 1995;34:6337.

- Coord. Chem. Rev.. 2003;245(1–2):85.

- Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2007;42:394.

- Chem. Rev.. 1992;92:521.

- Chem. Rev.. 1996;96:2563.

- Inorg. Chem.. 1993;32:1844.

- Trans. Met. Chem.. 1988;23:423.

- Trans. Met. Chem.. 1991;16:565.

- Trans. Met. Chem.. 1995;20:303.

- J. Inorg. Biochem.. 1991;41:1.

- Inorg. Chem.. 1996;35:3409.