Translate this page into:

Updated review on Indian Ficus species

⁎Corresponding author. bharatsingh217@gmail.com (Bharat Singh)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University. Production and hosting by Elsevier.

Abstract

As per Ayurvedic system of medicine, Indian Ficus (Fam. – Moraceae) plants are used in the treatment of various diseases. The plants are characterized by a specific class of closed inflorescence, named syconia, and are distributed in different states of India. Total 97 species of Ficus genus are naturalized in Indian states. Indian Ficus species possess anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antidiabetic, antiarthritic, antistress, anticancer, hepatoprotective, neuroprotective and wound healing properties. The phytochemical analysis reveals the presence of alkaloids, triterpenoids, flavonoids, furanocoumarins, and polyphenolic compounds in different species. Recently, bioavailability of Indian Ficus has been increased due to the presence of antioxidative agents. However, large number of reports have been published on phytochemistry and biological activities of 31 Indian Ficus species but, no reports are available in literature on 66 species. This review summarizes and describes the current knowledge of ethnomedicinal uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, bioavailability, and pharmacokinetic profiles of 31 Indian Ficus species. Moreover, it includes clinical and toxicological studies with an aim to explore their potential in the pharmaceutical industries.

Keywords

Clinical and toxicological studies

Ethnomedicinal properties

Ficus species

Pharmacology

Phytochemistry

- ABTS

-

2,2-Azinobis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate)

- ALT

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST

-

Aspartate transaminase

- BSA

-

Bovine serum albumin

- CAT

-

Catalase

- CCl4

-

Carbon tetrachloride

- CFA

-

Complete Freund’s adjuvant

- COX-2

-

cyclooxygenase 2

- DMSO

-

Dimethylsulfoxide

- DPPH

-

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- FRAP

-

Ferric reducing antioxidant power assay

- HFD-STZ

-

High fat diet fed-streptozotocin- induced

- iNOS

-

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- LPS

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MDA

-

malondialdehyde

- MIA

-

Monosodium iodoacetate

- MIC

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- MTT assay

-

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide

- NO

-

Nitric oxide

- ORAC

-

Oxygen radical absorbance capacity

- PGE2

-

Prostaglandin E2

- SGOT

-

Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase

- SGPT

-

Serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase

- SOD

-

Superoxide dismutase

- TNF-α

-

Tumor necrosis factor

- VEGF

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

Medicinal plants play vital roles in primary healthcare system of various developing countries due to lack of modern healthcare infrastructure, traditional acceptance, high cost of pharmaceutical drugs as well as efficacy of medicinal plants against certain disorders that cannot be treated by modern therapeutic drugs (Abdullahi, 2011; Kipkore et al., 2014; Megersa and Tamrat, 2022). Numerous patients in these developing countries combine folklore medicines with standard medicines and use them for the treatment of chronic diseases (Kigen et al., 2013). Ficus genus includes trees, hemi-epiphytes, shrubs, creepers, and climbers and are distributed in the forests, tropical and subtropical areas of Asia, Africa, America, and Australia (Hamed, 2011; Ahmed and Urooj, 2010b). Certain Indian Ficus species do not bear fruits, but they have similar morphological characters that are problematic to be distinguished from their species and variants. Every part of Ficus plants is used in the treatment of peptic ulcers, piles, jaundice, haemorrhage, diabetes, asthma, diarrhoea, dysentery, biliousness, and leprosy (Chopra et al., 1956; Kirtikar and Basu, 1995; Cox and Balick, 1996; Khan and Khatoon, 2007).

Different species of Indian Ficus genus contain sesquiterpenes, monoterpenes, triterpenoids, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, anthocyanins, alkaloids, furanocoumarins, organic acids, volatile components, and phenylpropanoids (Khayam et al., 2019; Shao et al., 2018; Tamta et al., 2021). These metabolites occur in latex, leaves, fruit, stem, and roots of different species (Shahinuzzaman et al., 2021). The Indian Ficus plants possess remarkable analgesic (Mahajan et al., 2012), antimicrobial (Patil and Patil, 2010), antiarthritic (Thite et al., 2014), anticancer (Jamil and Abdul Ghani, 2017), neuroprotective (Ramakrishna et al., 2014) and antidiabetic properties (Anjum and Tripathi, 2019a).

The present review summarizes and discusses the updated knowledge of ethnomedicinal properties, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities of 31 Indian Ficus species. Moreover, toxicological, and clinical studies are also included in this review. Out of 31 species, some species possess potent biological activities, but they have not been evaluated for their clinical research. No information is available in literature on 66 species. This review also provides some critical insights into the current scientific knowledge of bioavailability and pharmacokinetic profiles and its future potential in pharmaceutical research.

2 Methods

The data of identified compounds, studies of pharmacological activities, clinical trials, and toxicological research of 31 species were extracted by using various databases and search-engines e.g., monographs, reference books, MSc/MTech dissertations, PhD theses, PubMed/Medline, Scopus, ScienceDirect, Scifinder, Microsoft Academic, eFloras, Wiley, Google Scholar, DataONE Search, and Research Gate. The meta-analysis of extracted information was also conducted. The authors did not include the pharmacological activities of synthetic and semisynthetic compounds in this review.

3 Results

3.1 Botany and ethnomedicinal properties

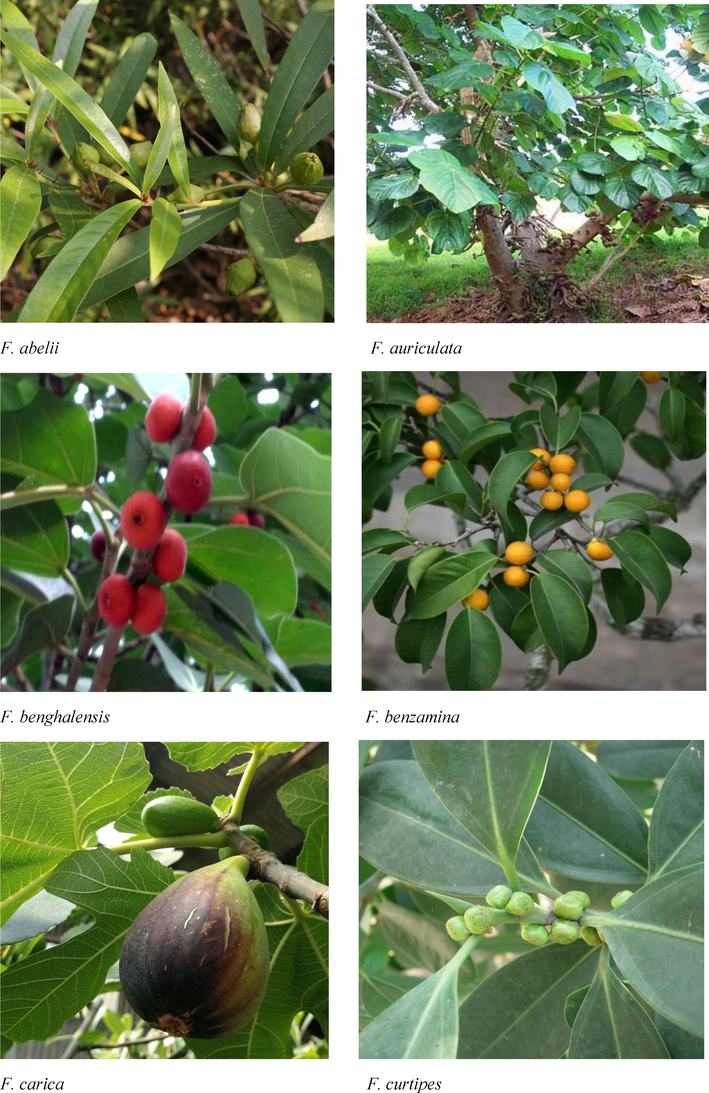

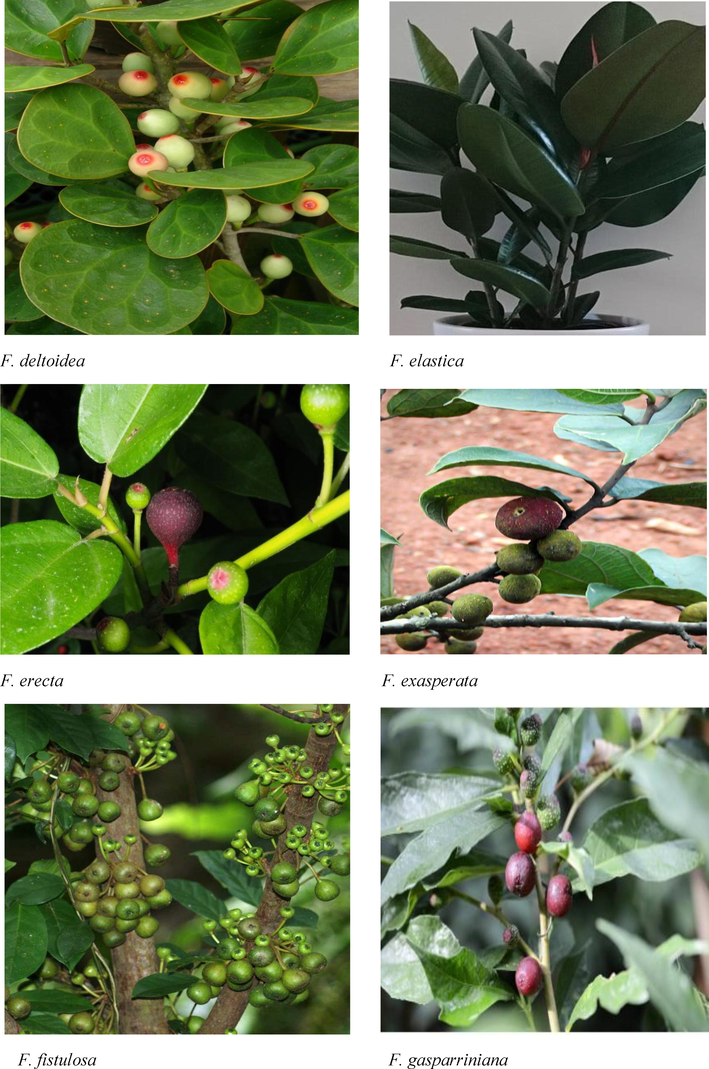

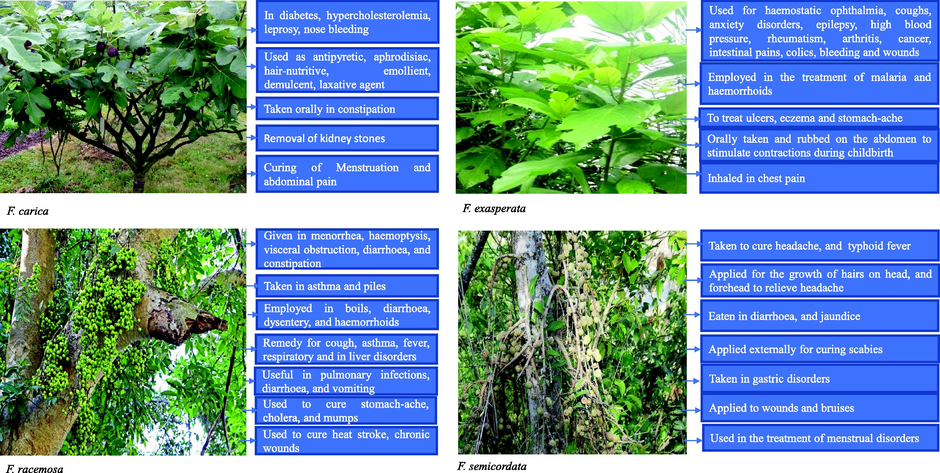

Most Indian Ficus species are deciduous and evergreen trees, shrubs, herbs, and climbers. The leaves are reticulate, palmately compound, waxy, and exude white or yellow latex when broken. Many Indian Ficus species have aerial roots, whereas few are epiphytes. The syconium is hollow, enclosing an inflorescence with small male and female flowers lining the inside (Fig. 1). Different parts (bark, fruit, leaves, roots, and latex) of Ficus plants are used in the treatment of leprosy, nose bleeding, cough, paralysis, liver diseases, chest pain, and piles (Kirtikar and Basu, 1995; Khanom et al., 2000; Jaradat, 2005). Leaf infusion of F. carica is recommended as remedy for the treatment of diabetes and hypercholesterolemia (Chaachouay et al., 2019). Powdered roots and leaves of F. deltoidea are taken in the treatment of wounds, rheumatism, and sores (Burkill and Haniff, 1930). Fruits of F. racemosa are given in menorrhea, haemoptysis, visceral obstruction, diarrhoea, and constipation (Chopra et al., 1958; Ahmed et al., 2012b). Mixture of F. religiosa leaf juice and honey is employed for the treatment of asthma, cough, diarrhoea, earache, toothache, migraine, eye troubles, and scabies (Jain et al., 1991; Bhattarai, 1993b; Yadav, 1999). The ethnomedicinal properties of 31 Indian Ficus species are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 2.

Morphological features of Indian Ficus species.

Morphological features of Indian Ficus species.

Morphological features of Indian Ficus species.

Morphological features of Indian Ficus species.

Morphological features of Indian Ficus species.

Morphological features of Indian Ficus species.

Species

State/India

Disease/complaints

Mode/parts of application

References

F. abelii

Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, and Meghalaya

Used in the treatment of diabetes

Leaf decoction

Chaachouay et al. (2019)

F. auriculata (syn.

F. pomifera)Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Jammu &

Kashmir, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Orissa, Sikkim, Karnataka, and West Bengal

Externally applied for wound healing

Paste of crushed leaves

Kunwar and Bussmann (2006)

Treatment of dysentery

Roasted figs

Zhang et al. (2019)

Used in cholera mumps, and vomiting

Latex of roots

Tamta et al. (2021)

Taken in the treatment of jaundice

Mixture of root powder and bark of Oroxylum indicum

Kunwar and Bussmann (2006)

Useful in diarrhoea

Infusion of stem bark

Cox and Balick (1996)

Employed in the treatment of diabetes

Fruits

Wangkheirakpam and Laitonjam (2012)

F. bengalensis

Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, West Bengal, Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala

Employed in cold, cough and asthma

Boiled stem bark

Shakya (2000)

Used for diarrhoea, dysentery, indigestion, joint pain, dermatitis, gum swelling, gonorrhoea, and snake bite

Milky sap from bark

Cause allergy to children

Leaves

Dangol (2002)

Employed in stopping the menstruation

Aerial root juice

Mishara (1998)

Applied externally for body pain, toothache, diabetes, joint pain, and rheumatism

Kharel and Siwakoti (2002)

Helps in leucorrhoea control

Root bark powder is mixed with Desmostachys bipinnata and is taken with one spoon of sugar

Siwakoti and Siwakoti (2000)

Treatment of boils, wounds and obstinate vomiting

Root latex

Parajuli (2001)

It is used in diarrhoea

Aerial roots decoction and water obtained from rice wash

Chopra et al. (1956)

F. benzamina

Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya

Pradesh, Orissa, Sikkim, and Uttar PradeshApplied on the treatment of boils

Latex

Kunwar and Adhikari (2005)

F. carica

Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, North-east states, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu

Used in the treatment of diabetes and hypercholesterolemia

Leaf infusion

Chaachouay et al. (2019)

In leprosy and nose bleeding

Fruit powder

Idolo et al. (2010)

Useful in diarrhoea

Decoction of dried fruits and unpeeled almond

Ramazani et al. (2010)

Treatment of abdominal pain

Fruits juice

Khan and Khatoon (2007)

Treatment of leukoderma and ringworm infection

Root’s decoction

Kirtikar and Basu (1995)Dimomfu (1984)Akah et al. (1998)

Used as expectorant, diuretic, and anthelmintic agent

Latex

Bone treatment

Bark poultice

Bronchitis treatment

Aqueous infusion of fresh leaves

Tene et al. (2007)

Taken orally in constipation

Fruit juice

Prajapati et al. (2007)

Taken orally in the treatment of cough

Fruit decoction with honey

Ghazanfar and Al-Abahi (1993)

Expectorant

Fruit

Afzal et al. (2009)

Jaundice

20 mL of leaf juice mixed with a cup of goat milk is taken early in the morning for 3 days

Manjula et al. (2011)

Removal of kidney stone

Bark and leaves

Afzal et al. (2009)

Leukoderma

Roots

Kalaskar et al. (2010)

In menstruation pain

Aqueous infusion of fresh leaf tender is taken orally as a drink

Tene et al. (2007)

Regulates blood stream

Decoction made with dried fruits, lemon peel and Laurus nobilis leaves

Idolo et al. (2010)

To remove weakness

Single dry fruit is soaked in water for a night and is consumed at morning for 15 days

Patil et al. (2011)

Skin disease

Fruits and stem latex

Khan and Khatoon (2007)

F. curtipes

Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Sikkim,

Tripura, and West BengalUsed as immune stimulant

Decoction of stem bark and leaves

Andrade et al. (2019)

F. deltoidea

Assam, and West Bengal

Treatment of wounds, rheumatism, and sores

Powdered roots and leaves

Burkill and Haniff (1930)Khan et al. (2011)

Used as a tonic to contract the uterus and vaginal muscles, and to treat menstrual cycle, and leucorrhoea

Decoction of boiled leaves

Chewed to relieve toothache, cold, and headache

Fruits

Bunawan et al. (2014)

Bouquet (1969)

Taken as an aphrodisiac tonic

Whole plant

F. elastica

Assam, Meghalaya, Sikkim, Assam, and West Bengal

Useful in skin infections and skin allergies

Boiled leaf extract

Kiem et al. (2012)

Employed as a diuretic agent

Cold leaf extract

Teinkela et al. (2018)

Employed as an astringent and styptics for wounds

Stem bark

Rahman and Khanom (2013)

F. erecta

Assam, Sikkim, and Meghalaya

Recommended as medicine in nephritis, and arthritis

Whole plant

Yakushiji et al. (2012)

Treatment of inflammations

Roots, stem bark, and fruits

Kislev et al. (2006)

F. exasperata

Andaman & Nicobar Island, Central and Southern states of India

Used in the treatment of stomach disorders, coughs, epilepsy, high blood pressure, rheumatism, arthritis, intestinal pains, and wounds

Leaf decoction

Dalziel (1948)

Employed as an antipyretic agent

Leaves

Haxaire (1979)

Used in the treatment of malaria

The leaves are macerated in water and the decoction is taken orally

Titanji et al. (2008)

Used in the treatment of haemorrhoids

Aqueous extract of leaves

Focho et al. (2009)

In diarrhoea treatment

Infusion of leaves

Noumi and Yomi (2001)

Treatment of ulcer

Few leaves are chewed and swallowed three times for 4–8 weeks

Berg (1989)

To treat stomach-ache

Infusion of dried leaves

Akah et al. (1997)

Remedy for peptic ulcers

50 Leaves of F. exasperata, 50 leaves of Emilia coccinea and 10 fruits of Capsicum frutescens are boiled in water (1 l), homogenized, and filtered. 150 mL filtrate is taken twice a day for 5 days

Noumi and Dibakto (2000)

Treatment of asthma, bronchitis, tuberculosis, and emphysema

Leaf juice mixed with lemon juice and taken twice a day

Bafor and Igbinuwen (2009)

Used for insomnia

Fresh leaves

Kerharo (1974)

Applied externally to treat eczema

Stem bark crushed with the roots of Croton roxburghii in coconut milk

Harsha et al. (2003)

Eaten to relieve throat pain

Dried flowers

Chhabra et al. (1984)

Used to manage asthma, and venereal diseases

Roots

Chhabra et al. (1990)

Inhaled in case of chest pain

Leaves are boiled in water and the steam

Assi (1990)

Used to arrest bleeding by traditional birth attendants in hastening childbirth

Plant sap

Irene and Iheanacho (2007)

Orally taken and rubbed on the abdomen to stimulate uterus contractions during childbirth

Dried leaf decoction

Hutchinson (1985)

F. fistulosa

Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Bengal, Jharkhand, Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Tripura

Used in the post-natal treatment, and possess diaphoretic property

Whole plant

Mehra et al. (2014)

F. gasparriniana

Bihar, Arunachal Pradesh,

Assam, Meghalaya, Nagaland, and SikkimUsed in the improvement of digestion

Roots

Luo et al. (2019)

F. geniculata

Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Jharkhand, Meghalaya, Orissa, Sikkim, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal

Medicines for haemorrhage, stomach disorder, gastrointestinal, arthritis, headache, and cardiovascular disorder

Stem bark and leaves

Kumari et al. (2019)

F. hirta

Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Meghalaya, Tripura, and West Bengal

Used as child snacks

Ripe female figs

Shi et al. (2014)

F. hispida

Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, West Bengal, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, and Rajasthan

Is taken for earache

Leaf juice

Basnet (1998)

Used to treat liver complaints

Fumes from twigs

Dangol and Gurung (1995)

Used as emetic and purgative agents

Fruit, seed, and bark

Kharel and Siwakoti (2002)

Remedy to treat diabetes

Infusion of stem bark

Khan et al. (2011)

Used as lactagogue and tonic

Seed infusion

Kirtikar and Basu (1987)

Given to mother as a galactagogue for better milk formation

Boiled green fruits

Behera (2006)

F. lacor

Uttarakhand, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh

Used to treat leucorrhoea, ulcers, and boils

Decoction of buds

Manandhar (1985)

Useful in the curing of stomach disorders

Seeds

Bhatt (1977)

Treatment of Harsha

Dried buds

Nakarmi (2001)

Used to treat diabetes

Powder of dried ripened fruits

Khan et al. (2011)

In expelling round worms from stomach

Stem bark

Nadkarni and Nadkarni (1976a)

Used for treatment of various skin problems

Leaves

Gupta and Arora (2013)

F. lamponga

Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, and West Bengal

In the treatment of jaundice

Whole plant

Das et al. (2008)

F. lyrata (Syn. F. pandurata Sand)

Andaman & Nicobar Islands

Used as diuretic and antidepressant agent

Leaves

Dhawan et al. (1977)

F. microcarpa

Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Peninsular region, Punjab, Rajasthan, and Sikkim

Used as insecticide to kill housefly

Leaf extract

Kalaskar and Surana (2012)

Taken orally in the treatment of diabetes

Powder of fresh leaves and fruits (equal amounts)

Khan et al. (2011)

F. mollis

Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Bihar, Central and Southern provinces, Jharkhand, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh

Used to increase lactation after delivery of women

Whole plant

Shahare and Bodele (2020)

Used to treat ulcers and wounds

Leaves

Thapa (2001)Lim (2012)

Applied as a poultice to treat boils

Crushed leaves

Used for stomatitis, and to clean ulcers

Roots

Priya and Abinaya (2018)Ghimire et al. (2000)

To treat skin infections, neck swelling and scabies

Stem bark

F. neriifolia

Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Uttar Pradesh, and Western

to Eastern HimalayasGiven in conjunctivitis

Stem bark juice

Manandhar (2001)

Used in the treatment of boils

Milky latex of bark

Khan et al. (2011)

F. palmata

Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Kerala Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh

Employed in ringworm and skin diseases

Fruit paste

Thapa (2001)

Used in dysentery and vomiting

Ripen fruits

Devkota and Karmacharya (2003)

Applied to extract spines deeply lodged in the flesh

Stem latex

Manandhar (1995)

Used to treat digestion complaints

Fruits

Pala et al. (2010)

F. pumila

Rajasthan, Gujarat, Punjab, Uttarakhand, Himachal Pradesh, Assam, Karnataka

Treatment of bleeding, swelling, haemorrhoids, and intestinal disorders

Leaves and fruits

Abraham et al. (2008)

Used to treat diabetes, and high blood pressure

Leaves and fruits

Kaur (2012)

Used for skin infections

Stem latex

Mazid et al. (2012)Sarkar and Devi (2017)Pant and Pant (2004)

Useful in carbuncle, dysentery, haematuria, and piles

Leaves

Used to treat bladder inflammation and dysuria

Roots

Employed for backache, piles, swellings, and tuberculosis of the testicles

Stem or fruit peel

Rahman and Khanom (2013)Vihari (1995)Khare (2007a)

Used for boils, rheumatism, and sore throat

Dried leaves and stems

In the treatment of hernia

Fruit decoction

F. racemosa (syn. F. glomerata)

Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Orissa, Sikkim, Meghalaya, and West Bengal

Used as an astringent, stomachic, carminative given in menorrhea, and constipation

Fruits

Chopra et al. (1958)

Useful in leprosy

A bath made of fruit and bark

Nadkarni et al. (1976)

Raghunatha Iyer (1995)

In the treatment of diabetes

Fruit infusion

Used in bilious infections

Leaf powder mixed with honey

Kirtikar and Basu (1975)

Muller Boker (1999)

Taken in asthma and piles treatment

Bark decoction

Used for boils, blisters, and measles

Leaf latex

Siwakoti and Siwakoti (2000)

Valuable medicine in diabetes

Trunk sap

Paudyal (2000)

Used in burns, swelling, leukorrhea dysentery and diarrhoea

Paste of stem bark

Tiwari (2001)

Used to cure heat stroke, and chronic wounds

Root sap

Thapa (2001)

Taken as aphrodisiac agent

Stem latex

Yadav (1999)

Used to cure stomach-ache, cholera, and mumps

Stem latex

Basnet (1998)

Remedy for cough, asthma, fever, respiratory and liver disorders

Leaf galls

Annon (1976)

Treatment of children’s ear infections, and used to suppress nose bleeding

Leaf galls

Nadkarni (1976)

Used in pulmonary infections, diarrhoea, and vomiting

Leaf galls

Kirthikar and Basu (1935)

F. religiosa

Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Bihar,

Meghalaya, and SikkimEmployed in the treatment of asthma, cough, sexual disorders, diarrhoea, haematuria, earache, toothache, migraine, and gastric complaints

Mixture of leaf juice and honey

Jain et al. (1991)

Used as an analgesic for toothache

Leaf decoction

Bhattarai (1993a)Bhattarai (1993b)

Eaten to facilitate asthma and respiratory system

Fruits

Applied externally to treat scabies

Fruit paste

Siwakoti and Siwakoti (2000)

Taken in scabies

Bark infusion

Chaudhary (1994)

Used in gonorrhoea, wounds, diabetes, diarrhoea, and bone fracture

Stem bark

Shrestha (1997)

Useful in cough, cold and mild fever

Mixture of bark paste and honey (equal amounts)

Dangol (2002)

Employed in the treatment of menstrual complaints

Aerial root juice

Thapa (2001)

F. retusa

Goa, Assam, Meghalaya, and Uttar Pradesh

Used in wounds and bruises

Roots, stem barks, and leaves

Chopra et al. (1956)

(Karki 2001)

Applied to treat decaying or aching tooth

Dried roots are mixed with salt

Used in the treatment of liver diseases

Roots

Semwal et al. (2013)

F. sarmentosa

Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, Meghalaya,

Mizoram, Punjab, Sikkim, Tripura, Uttar Pradesh, and West BengalRecommended as remedy for wounds, fever, swollen joints, inflammations, and ulcers

Whole plant

Ripu et al. (2006)

Joshi and Joshi (2000)Guan et al. (2007)

Taken to cure boils and to increase milk secretion after delivery

Edible bark powder

Used in malaria

Aqueous root extract

Cure for leprosy

A bath made from the fruit and bark

Dimri et al. (2018)Priyanka et al. (2016)Gupta and Acharya (2018)

Lansky (2011)

Curing of fever

Latex

Eaten in diarrhoea

Raw fruits

Applied on forehead to relieve headache

Young fruit juice

F. semicordata

Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Assam, West Bengal, and Karnataka

Applied on forehead to cure headache

Root paste

Rajendra and Prasad (2009)

Taken orally at the time of pregnancy

Fresh decoction of the stem bark and leaves

Ghildiyal et al. (2014)

Curing the fever

Latex

Kunwar and Bussmann (2006)

Taken in typhoid fever

Milky sap of aerial parts diluted once in water

Gopal (2013)

Applied for the growth of hairs on head

Milky latex

Phondani et al. (2010)

Eaten in diarrhoea

Raw fruits

Shashi and Rabinarayan (2018)

Taken orally to get relief from jaundice

Leaf decoction

Gupta and Acharya (2019)

Used in the treatment of constipation

Ripe figs

Kunwar and Bussmann (2006)

Applied to treat wounds and bruises

Juice and powdered stem bark

Khare (2007)

Used to treat boils

Latex

Rajesh et al. (2017)

Applied for curing scabies

Leaf juice

Shubhechchha (2012)

Used in the treatment of menstrual disorders

Juice of stem bark of F. semicordata and M. esculenta

Nikomtat et al. (2011)

F. talbotii

Madhya Pradesh, and Peninsular region

Used for ulcers and venereal diseases

Stem bark

Khare (2007)

Employed as diuretic, spasmolytic, and antidepressant agent

Aerial parts

Shi et al. (2018)

F. tikoua

Assam, Manipur, West Bengal

Used in the treatment of chronic bronchitis, diarrhoea, dysentery, rheumatism, oedema, and impetigo

Rhizomes

Jiangsu New Medical College (1986)

F. tinctoria

Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Bihar, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Meghalaya, Orissa, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh

Used as a tonic for weakness after the childbirth

Leaf decoction

Smith (1979)

Employed in dressing for broken bones

Plant juice and leaves

Satapathy and Kumar (2017)

Ethnomedicinal properties of some important Indian Ficus species.

3.2 Phytochemistry

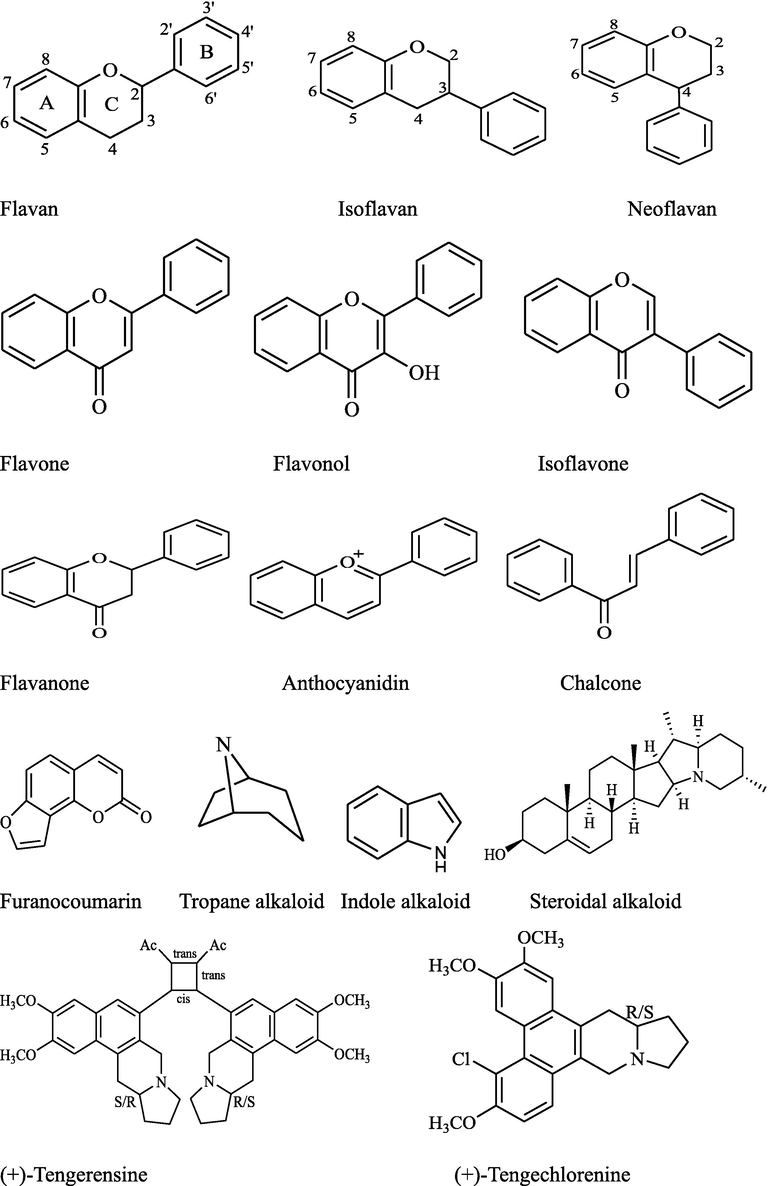

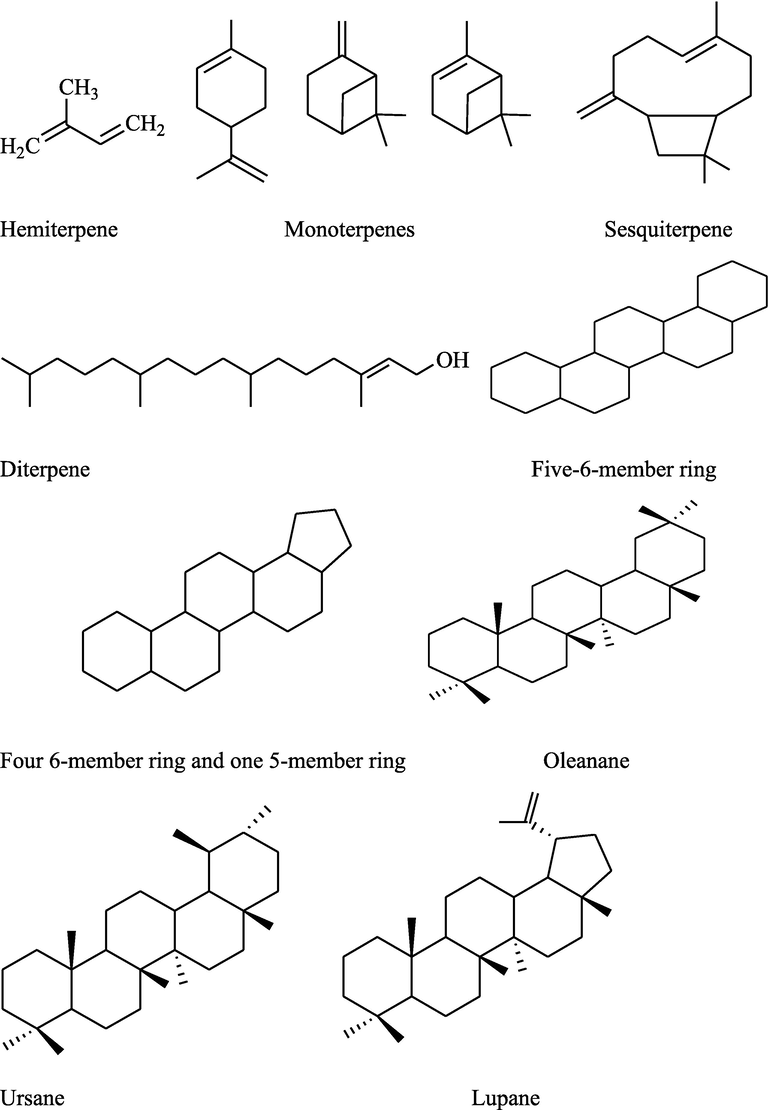

The phenylpropanoids, isoflavonoids, flavonoids, phenolic glycosides, monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, triterpenes, and alkaloids have been isolated and identified from 25 species {F. auriculata (syn. F. pomifera), F. bengalensis, F. benjamina, F. carica, F. curtipes, F. deltoidea, F. elastica, F. erecta, F. exasperata, F. fistulosa, F. geniculata, F. hirta, F. hispida, F. lacor, F. lyrata (Syn. F. pandurata), F. macrocarpa, F. mollis, F. palmata, F. pumila, F. racemosa (syn. F. glomerata), F. religiosa, F. retusa, F. sarmentosa, F. semicordata, and F. tikoua}of Indian Ficus genus while other 72 species {F. abelii Miq, F. filicauda Hand. - Mazz., F. ischnopoda Miq., F. nigrescens King, F. fulva Reinw. ex Blume, F. langkokensis Drake, F. pubigera (Miq. ex Wall.) Brandis, F. laevis Blume, F. diversiformis Miq., F. chartacea (Wall. ex Kurz) Wall. ex-King, F. laevis Blume var. macrocarpa (Miq.) Corner, F. crininervia Miq., F. villosa Blume, F. sagittata Vahl, F. recurva Blume, F. pendens Corner, F. hedaracea Roxb., F. punctata Thunb., F. ampelas Burm. f., F. andamanica Corner, F. assamica Miq., F. copiosa Steud., F. cyrtophylla (Miq.) Miq., F. heterophylla L. f., F. praetermissa Corner, F. montana Burm. f., F. subincisa Buch. -Ham. ex J. E. Sm., F. subincisa Buch. -Ham. ex J. E. Sm. var. paucidentata (Miq.) Corner, F. heteropleura Blume, F. obscura Blume var. borneensis (Miq.) Corner, F. sinuata Thunb., F. subulata Blume, F. guttata (Wight) Kurz ex-King, F. variegata Blume, F. prostrata (Wall. ex Miq.) Miq., F. squamosa Roxb., F. ribes Reinwdt. ex Blume, F. magnoliifolia Blume, F. nervosa B. Heyne ex Roth, F. albipila (Miq.) King, F. callosa Willd., F. capillipes Gagnep., F. alongensis Gagnep., F. amplissima J. E. Sm., F. arnottiana (Miq.) Miq., F. caulocarpa (Miq.) Miq., F. concinna (Miq.) Miq., F. cupulata Haines, F. hookeriana Corner, F. maclellandii King var. rhododendrifolia (Miq.) Corner, F. rigida Jacq., F. rumphii Blume, F. superba (Miq.), F. tsjahela Burm. f., F. virens Aiton, F. altissima Blume, F. beddomei King, F. costata Aiton, F. dalhousiae (Miq.) Miq., F. drupacea Thunb., F. fergusonii (King) Worthington, F. maclellandii King, F. pellucidopunctata Griff., F. stricta (Miq.) Miq., F. sundaica Blume, F. trimenii King, F. gasparriniana Miq., F. macrophylla Desf. ex Pers, F. lamponga Miq., F. neriifolia Sm., F. talbotii King, and F. tinctoria G.Forst} have not been evaluated for the presence of phytoconstituents. The backbone structures of identified compounds are presented in Fig. 3. The state-wise location, types of extracts, parts used, and identified phytoconstituents are described in Table 2.

Backbone structures of important isolated and identified compounds of Indian Ficus species.

Backbone structures of important isolated and identified compounds of Indian Ficus species.

Plant species

Extract type

Plant parts

Compounds type

Isolated compounds

References

F. auriculata (syn.

F. pomifera)

Ethanolic (70%)

Dried fruits

Sesquiterpene

Aristolone

Ambarwati et al. (2021)

Ethanolic

Roots

Isoflavones

5,7,4′-Trihydroxy-3′-hydroxymethylisoflavone, 3′-formyl-5,4′-dihydroxy-7-methoxyisoflavone, ficuisoflavone and alpinumisoflavone

Qi et al. (2018)

Aerial parts

Flavonoids

Quercetin, epigallocatechin, kaempferol, quercetin, and myricetin

El-Fishawy et al. (2011); Khayam et al. (2019)

Leaves

Volatile oils

4-Phenylmethyl-pyridine, dibutyl phthalate, phytol, 3β-lup-20(29)-en-3-ol-acetate and indol, 4-phenylmethyl-pyridine

Shao et al. (2013)

Stem

Triterpenoids

Betulinic acid, lupeol, stigmasterol, scopoletin, and β-sitosteril-3-O-β-D- glucopyranoside,

El-Fishawy et al. (2011)

Lactone

Ficusine D

Shao et al. (2018); Tamta et al. (2021)

Fruit

Phenolic acids

Galloylquinic acid, 3-O-cafeoylquinic acid, 4-O-cafeoylquinic acid, 5-O-cafeoylquinic acid, procyanidin trimer (B-type), 4-O-feruloylquinic acid derivatives, methoxyl-epicatchin dimer, epicatchin-trimer (A-type), trihydroxy-octadecadienoic acid, trihydroxy octadecanoic acid, gallocatchin-O-hexoside, hydroxy-octadecatrienoic acid, xanthone derivatives, and 3-methyl epigallocatechin gallate

Shahinuzzaman et al. (2021)

Ethyl acetate

Stem

12-Membered and benzoic acid lactones

(3R,4R)-4-Hydroxy-de-O-methyllasiodiplodin, 6-oxolasiodiplodin and ficusines A-C, (R)-(+)-lasiodiplodin, (+)-(R)-de-O-methyllasiodiplodin and (3R,6S)-6-hydroxylasiodiplodin

Shao et al. (2014)

Aqueous

Dried bark

Furanocoumarins

Bergapten

Tiwari et al. (2017)

Flavonoid

Myricetin and querecetin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

Petroleum ether

Leaves

Triterpenoids

3β-Acetoxyurs-12-ene, 3β-hydroxyurs-12-ene, 3β-hydroxyurs-12-en-27-oic acid, 3β-hydroxyolean-12-en-27-oic acid and 3α-acetoxyolean-12-en-27-oic acid

Wangkheirakpam et al. (2015)

F. benghalensis

Methanolic

Leaves

Essential oils

α-Cadinol, germacrene D-4-ol, γ-cadinene, α-muurolene, β-caryophyllene epoxide, cyclosativene, cubenol, τ-cadinol, (E)-β-ionone, δ-cadinene, β-geranylacetone, toluene, γ-muurolene, ethylbenzene, α-copaene, α-phellandrene, linalool, β-caryophyllene, maaliene, n-nonanal, n-hexanal, β-cyclocitral, (E)-α-ionone and limonene

Adebayo et al. (2015)

Flavonoids

Naringenin, and quercetin

Rao et al. (2014)

Stem bark

Triterpenoids

Lanostadienylglucosyl cetoleate, bengalensisteroic acid ester, heneicosanyl oleate, α-amyrin acetate, and lupeol

Naquvi et al. (2015)

Terpenoid

3, 7, 11, 15-Tetramethyl-2-hexadecen-1-ol (phytol)

Kanjikar and Londonkar (2020)

Aerial roots

Flavones and coumarins

Bengalensinone, benganoic acid, apocarotenoid, alpinumisoflavone, 4-hydroxyacetophenone, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 4-hydroxymellein, and p-coumeric acid

Riaz et al. (2012)

Lupane triterpenoids

Stigmasterol, lupanyl acetate, and 3-acetoxy-9(11),12-ursandiene

Ethanolic

Aerial roots

Phenolics

Cyanidin 3-glucoside equivalent, cyanidin 3-glucoside, chlorogenic acid, caffeic acid, quercetin, naringenin, and kaempferol

Afzal et al. (2020)

Fruits

Phenolics

Cyanidin 3-glucoside equivalent, cyanidin 3-glucoside, chlorogenic acid, and caffeic acid

Aerial parts

Triterpenoids

Lanosterol, lupeol, amyrin acetate, lupenyl acetate, friedelanol, cyclolaudenol, epifriedelanol, dihydrobrassicasterol, stigmasterol, sitosterol, ergosterol acetate, furostano, 4,22-stigmastadiene-3-one, 1-heptatriacotanol, and protodioscin

Verma et al. (2015)

Stigmasterol

Fegade Sachin and Siddaiah (2019)

Stem bark

Flavonoids

5,7-Dimethyl ether of leucopelargonidin 3-O-α-L rhamnoside and 5,3′-dimethyl ether of leucocyanidin 3-O-α-D galactosyl cellobioside, and quercetin

Daniel et al. (1998)

Fruits

Phenolic acid

Caffeic acid

Gopukumar and Praseetha (2015)

Aqueous- acetone

Stem bark

Anthocyanin

Pelargonidin

Kundap et al. (2017)

Ethyl acetate

Leaves

Flavonoids

5,6,7,3′,5′-Pentamethoxy-4′-prenyloxyflavone, rutin, quercetin and 3-acetyl ursa-14:15-en-16-one

Elgindi (2004)

Chloroform

Leaves

Phenolics

Cinnamic acid, gallic acid, theaflavin-3,3́-digallate, rutin, quercetin-3-galactoside, leucodelphinidin, gallocatechin, kaempferol, leucocydin and apigenin

Almahy et al. (2003)

Stem bark and leaves

Triterpenoids

Stigmasterol, friedelin, lupeol, β-amyrin, 3-friedelanol, betulinic acid, 20-traxasten-3-ol, taraxosterol, and β-sitosterol

Murugesu et al. (2021)

F. benjamina

3% formic acid in 70% methanol/dH2O

Leaves and stem bark

Indole-type

Calycanthidine, akuammidine, ergoline, dasycarpidan, ibogamine, ajamalicine, and dasycarpidol

Novelli et al. (2014)

Indolyzidine-type

Obscurinervinediol, and crinamidine

Isoquinoline-type

Columbamine, laudanosoline, methylcoridaldine, salsoline, reticuline, hydroxymorphine, and isoclaurine

Quinolizidine-type

Sophocarpine, matridine, scoulerine, and lycocernuine

Pyridine-type

Anabasine, nicodicodine, adenocarpine, and lutidine

Carbazol-type

Neblinine, harmine, ellipticine, and aspidospermidin

Pyrrolizidine-type

Indicine N-oxide, and retronecine

Steroidal-type

Tomatidine and solasodine

Quinoline-type

Cinchophen

Pyrrolidine-type

Clemastine

Tropane-type

p-Bromo atropine

Acridine-type

Acridine derivative

Petroleum ether

Leaves

Pentacyclic triterpenoids

Ursolic acid and lupeol

Singh et al. (2020)

Ethyl acetate

Fruits

Isoflavonoids

5,7,4′-Trihydroxy-6-(3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadienyl)isoflavone, 5,7,2′,4′-tetrahydroxy-8-(3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadienyl)isoflavone, 6-[(1R*,6R*)-3-methyl-6-(1-methylethenyl)-2-cyclohexen-1-yl]-5,7,4′- trihydroxyisoflavone, 3,5,7-trihydroxy-4′-methoxycoumarano-chroman-4-one, 6-(3-methyl-2-buten-1-yl)-3,5,7-trihydroxy-4′-methoxycoumarano-chroman-4- one, 5,4′-dihydroxy- 2″-hydroxyisopropyldihydrofurano[4,5:7,8]-isoflavone, 5,4′-dihydroxy-2″-(-2-hydroxy-6-methylhept-5-en-2-yl)dihydrofurano[4,5:7,8]- isoflavone, 5,4′-dihydroxy-2″-(-2-hydroxy-6-methylhept-5-en-2-yl)dihydrofurano[4,5:6,7]- isoflavone, lespedezol E1, ficusin A, gancaonin N, lupiwighteone and erythrinin C

Dai et al. (2012); dos Anjos Cruz et al. (2022)

Aqueous methanol (95%)

Root bark

Triterpenoids and ceramide

β-Amyrin acetate, β-amyrin, psoralen, betulinic acid, lupeol, platanic acid, β-sitosterol glucoside, and benjaminamide

Simo et al. (2008)

F. carica

Ethanolic (70%)

Leaves

Isoflavones

Quercetin, luteolin, biochanin A, kaempferol, and rutin

Vaya and Mahmood (2006); Trifunschi et al. (2015)

Polyphenolics

3-O-(Rhamnopyranosyl-glucopyranosyl)-7-O-(glucopyranosyl)-quercetin, 2-carboxyl-1, 4-naphthohydroquinone-4-O-glucopyranoside, luteolin 6-C-glucopyranoside, 8-C-arabinopyranoside, schaftoside, isoorientin, isoschaftoside, rutin, 2″-O-rhamnosylvitexin, isovitexin, isoquercetin, kaempferol-3- O-rutinoside

Li et al. (2021b)

Ethanolic

Root bark

Triterpenoids

α-Amyrin, β-sitosterol, and β-sitosterol-β-D-glucoside

Jain et al. (2007)

Coumarins

Psoralen, bergapten, xanthotoxin, and 6-(2-methoxyvinyl)-7-methylcoumarin

Fruits

Prenylated isoflavone derivatives

Ficucaricones A–D

Liu et al. (2019)

Anthocyanin

Cyanidin-3-O-rutinoside

Solomon et al. (2006)

Leaves

Isoflavonoids

Rutin, isoschaftoside, isoquercetin, chlorogenic acid, caffeoyl malic acid and rutin

Takahashi et al. (2017)

Phenolic acids and flavonoids

Chlorogenic acid, rutin, and psoralen

Teixeira et al. (2006)

Leaves, pulps, and peels

Phenolic acids and flavonoids

3-O- and 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acids, ferulic acid, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside, psoralen and bergapten

Oliveira et al. (2009)

Methanolic

Leaves

Triterpenoids

Bauerenol, lupeol acetate, methyl maslinate, calotropenyl acetate and oleanolic acid

Saeed and Sabir (2002)

Furanocoumarin

Psoralen and bergapten

Takahashi et al. (2014); Li et al. (2021a)

Polyphenols and furanocoumarins

Caffeoyl malic acid, psoralic acid-glucoside, rutin, psoralen and bergapten

Yu et al. (2020); Ladhari et al. (2020)

Phenolics

Caffeoylmalic acid, psoralic acid-glucoside, rutin, psoralen and bergapten

Wang et al. (2017)

Fruits

Pentacyclic triterpenoids

Betulinic acid, and oleanolic acid

Wojdyło et al. (2016)

Methanol: water

(80:20%)Leaves

Phenolics

Chlorogenic acid, caffeoylmalic acid, p-coumaroyl derivative, p-coumaroylquinic acid, p-coumaroylmalic acid, caffeic acid, isoschaftoside, schaftoside, rutin, psolaric acid glucoside, quercetin 3-O- glucoside, quercetin 3-O-malonylglucoside, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, psolaren, and bergapten

Petruccelli et al. (2018)

Water - methanol (40:60)

Leaves

PolyphenolQuercetin-3-glucoside, caftaric acid, quercetin-3, 7-diglucoside, and coumaroyl-hexose, kaempferol-3-O-sophorotrioside, cichoric acid and sinapic acid glucoside

Nadeem and Zeb (2018)

Ammonium sulphate-Ethanol

Leaves

Flavonoids

3-O-(Rhamnopyranosyl-glucopyranosyl)-7-O-(glucopyrnosyl)-quercetin, 2-carboxyl-1,4-naphthohydroquinone-4-O-hexoside, luteolin 6-C-hexoside, 8-C-pentoside, kaempferol 6-C- hexoside −8-C-hexoside, quercetin 6-C-hexobioside, kaempferol 6-C- hexoside −8-C-hexoside, quercetin 3-O-hexobioside, apigenin 2″-O-pentoside, apigenin 6-C-hexoside, quercetin 3-O-hexoside, and kaempferol-3-O-hexobioside

Zhao et al. (2021)

F. curtipes

Methanolic

Stem bark

Phenolics

3-O-Caffeoylquinic acid, catechin, chlorogenic acid isomer, 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid, procyanidin type B, catechin/epicatechin derivative, epicatechin, vicenin-2, procyanidin type C, apigenin-7-O-hex-6/8-C-hex, apigenin-6-C-pt-8-C-hex, cinchonain type II, apigenin-6-C-hex-8-C-pent, cinchonain type I, vitexin, procyanidin type B, isovitexin, and aviculin

Andrade et al. (2019)

F. deltoidea

Methanolic

Leaves

Acyclic monoterpenes

6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-one, myrcene, (Z)-β-ocimene, (E)-β-ocimene, cis-furanoid linalool oxide, trans-furanoid linalool oxide, linalool, cis-pyranoid linalool oxide, trans-pyranoid linalool oxide, hotrienol, perillene

Grison-Pige et al. (2002a)

Cyclic monoterpenes

Limonene

Fruits

Sesquiterpenes

Dendrolasine, α-cubebene, cyclosativene, Α-ylangene, α-copaene, β-bourbonene, 1,5-diepi-β-bourbonene, β-cubebene, β-elemene, α-gurjunene, α-cis-bergamotene, β-caryophyllene, α-santalene, selina-3–6-diene, α-trans-bergamotene, α-humulene, alloaromadendrene, aciphyllene, germacrene D, β-selinene, αd-selinene, α-selinene, bicyclogermacrene, α-muurolene, germacrene A, δ-amorphene, (E,E) α-farnesene, 2-epi-α-selinene, δ-cadinene, cadina-1,4-diene, germacrene B, and caryophyllene oxide

Grison-Pige et al. (2002b)

Ethanolic

Leaves

Flavonoids

Gallocatechin, epigallocatechin, catechin, (epi)afzelechin-(epi)catechin, (epi)afzelechin-(epi)afzelechin, (epi)catechin, epicatechin, lucenin-2, vicenin-2, luteolin-6-C-hexosyl-8-C-pentoside, luteolin-6-C-glucosyl-8-C-arabinoside, isoschaftoside, luteolin-6-C-arabinosyl-8-C-glucoside, schaftoside, orientin, apigenin-6-C-pentosyl-8-C-glucoside, vitexin, apigenin-6-C-glucosyl-8-C-pentoside, apigenin-6,8-C-dipentoside isomer, isovitexin, 4-p-coumarolyquinic acid, rutin, quercetin, and naringenin

Ong et al. (2011); Omar et al. (2011); Choo et al. (2012)

Triterpenoid

Lupeol

Suryati et al. (2011)

Aqueous

Leaves and fruits

Flavonoids

Epicatechin, rutin, quercetin 5,4′-di-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, myricetin and naringenin

Dzolin et al. (2015)

Ethyl acetate

Leaves

Alkaloids

1,1′-(1,1-Ethenediyl) bis(3- methylpiperazine), and nigeglanine

Triadisti et al. (2021)

Terpenoid

1,1,2,3,3-Pentamethylindane

F. elastica

n-Hexane

Leaves

Phenolics

Macluraxanthone, rutin, chlorogenic acid, and psoralen

Teixeira et al. (2009)

Dichloromethane

Leaves

Triterpenoids

Campesterol, stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, α-amyrin, and friedelin

El-Hawary et al. (2012)

Ethanolic (70%)

Leaves

Flavonoids

Quercitrin, morin, myricitrin, and eleutheroside B

Ginting et al. (2020)

Ethanolic

Leaves

Pentacyclic triterpenoids

1-O-Caffaeoyl-D-mannitol, moretenone, glutinol, moretenol, lupeol, β-sitosterol, sakuranin, and kaempferol-3-O-rutinoside

EI-Domiaty et al. (2002)

Methanolic

Aerial root bark

Ceramide, cerebroside and triterpenoid saponin

Ficusamide, ficusoside and elasticoside

Mbosso et al. (2012)

F. erecta

Aqueous ethanol (50:50%)

Leaves and branches

Flavonoids

Chlorogenic acid, rutin, and keampferol-3-O-rutinoside

Sohn et al. (2021)

Ethanolic (70%)

Branches

Organic acids

p-Hydroxybenzoic acid, methyl p-hydroxybenzoate, vanillic acid, methyl vanillate, syringic acid, and ethyl linoleate

Park et al. (2012)

Triterpenoids

β-Sitosterol, and α-amyrin acetate

F. exasperata

Methanolic

Leaves

Isoflavone glycosides

Quercetin-3,7-di-hexoside, quercetin-3-(6-rhamnoside) glucoside, quercetin-3-glucoside, kaempferol-3–92- rhamnoside)hexoside, quercetin-3-(6-malonyl)hexoside, quercetin-3-hexoside-7-ketorhamnoside, kaempferol-3 hexoside, apigenin-7-(6-rhamnoside)hexoside, luteolin 6,8-di-C-hexoside, apigenin-6-C-pentoside-8-C-hexoside pigenin-6-C-hexoside-8-C-pentoside, apigenin-6-C rhamnoside-8-C-hexoside, apigenin-6-C-pentoside-8-C- (3/4-ketorhamnoside) hexoside, apigenin-8-C-glucoside, luteolin-8-C-(3/4-ketorhamnoside)hexoside, apigenin 7-O-ketorhamnoside-8-C-hexoside, and apigenin-8-C-(3/4 ketorhamnoside) hexoside

Mouho et al. (2018)

Ethanolic

Leaves

Phenolics

Quercitrin, chlorogenic acid and caffeic acid

Oboh et al. (2014)

Aqueous- ethanol (50:50%)

Leaves

Isoflavone glycosides

Apigenin C-8 glucoside, isoquercitrin-6-O-4-hydroxybenzoate and quercetin-3-O-β-rhamnoside

Taiwo and Igbeneghu (2014)

F. fistulosa

CH2Cl2/MeOH

Leaves

Bis-benzopyrroloisoquinoline and chlorinated phenanthroindolizidine enantiomers

(±)-Tengerensine, (+)-Tengechlorenine, (±)-fistulosine, (+)-antofine, and (−)-seco-antofine

Al-Khdhairawi et al. (2017); Putra et al. (2020)

Methanolic

Stem bark

Triterpenoids

3β-Acetyl ursa-14:15-en-16-one, lanosterol-11-one acetate, 3β-acetyl-22,23,24,25,26,27-hexanordamaran-20-one, 24-methylenecycloartenol, sorghumol (isoarborinol), 11α,12α-oxidotaraxeryl acetate, and ursa-9(11):12-dien-3β-ol acetate

Tuyen et al. (1998)

Ethanolic

Stem bark

Benzopyrroloisoquinoline alkaloids

Fistulosine

Subramaniam et al. (2009)

Phenanthroindolizidine alkaloids

(−)-13aα-Antofine, (−)-14β-hydroxyantofine and (−)-13aα-secoantofine

Stem bark and leaves

Septicine-type alkaloids

Fistulopsines A and B

Yap et al. (2016)

Phenanthroindolizidine alkaloids

(+)-Septicine, (+)-tylophorine, (+)-tylocrebrine, (–)-3,6-didemethylisotylocrebrine and (+) -(6S,9S)-vomifoliol

F. geniculata

Methanolic

Pulps and peels

Phenolics

3-O- and 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acids, ferulic acid, psoralen, and bergapten

Gupta et al. (2017)

F. hirta

Methanolic

Fruits

Flavonoids

Naringenin-7-O-β-D-glucoside, pinocembrin-7-O-β-D- glucoside, eriodictyol-7-O-β-D-glucoside, luteolin, apigenin, eriodictyol-7-O-β-D-glucoside, methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-β-carboline-3-carboxylic acid, 2-methyl-1-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-β-carboline-3-carboxylate, dihydrophaseic acid, vomifoliol, dehydrovomifoliol, pubinernoid A, 2-phenylethyl-O-β D-glucoside, 1-O-trans-cinnamoyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1 → 6)-β-D-glucopyranoside, 4-O-benzoyl-quinic acid, 3-O-benzoyl-quinic acid, benzyl-β-D-glucopyranoside, (2S) 2-O-benzoyl-butanedioic acid-4-methyl ester, pinocembrin-7-O-β-D-glucoside, naringenin-7-O-β-D-glucoside, eriodictyol-7-O-β-D-glucoside, luteolin, apigenin, and umbelliferone

Wan et al. (2017); Chen et al. (2020)

Methanolic (80%)

Roots

Phenolics

Luteolin, apigenin, psoralen, and bergapten

Yi et al. (2013)

Ethyl acetate

Roots

Phenylpropanoids

(1′S)-Methoxy-4-(1-propionyloxy-5-methoxycarboxyl-pentyloxy)-

(E)-formylvinyl, (8R)-4,5′-dihydroxy-8-hydroxymehtyl-3′-methoxydeoxybenzoin, (2′S)-3-[2,3-dihydro-6-hydroxy-2-(1-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)-5- benzofuranyl] methyl propionate, 3-[6-(5-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl) benzofuranyl] methyl propionate, methylcnidioside A, (E)-3-[5-(6-hydroxy) benzofuranyl] propenoic acid, ficuscarpanoside A, syringaresinol, (7R,8S)-ficusal, trans-p-hydroxycinnamic acid, 1′-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl (2R,3S)-3-hydroxynodakenetin, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, syringic acid, and ficuglucosideCheng et al. (2017a)

Ethyl acetate and n-butanol

Roots

Furanocoumarin glycoside

5-O-[β-D-Apiofuranosyl-(1 → 2)-β-D-glucopyranosyl]- bergaptol

Dai et al. (2018)

Phenolics

Bergapten, umbelliferone, 6-carboxy-umbelliferone, 6,7-furano-hydrocoumaric acid methyl ester, picraquassioside A, and rutin

Ethanolic

Roots

Triterpenoids

Stigmasterol, 22,23-dihydro-stigmasterol, α-amyrin, and β-sitosterol

Li et al. (2006)

Phenolics

Psoralene, 3β-hydroxy-stigmast-5-en-7-one, 5-hydroxy-4′, 6, 7, 8-tetramethoxy flavone, 4′, 5, 6, 7, 8-pentamethoxy flavone, 4′, 5, 7-trihydroxy-flavone, 3β-acetoxy-β-amyrin, 3β-acetoxy-α-amyrin and hesperidin

Epicatechin, chlorogenic acid, (-) (2R,3R)epiafzelechin, psoralenoside, methoxypsoralenoside, hydrasine, 4,5-dihydrogenpsoralenoside, pelargonidin 7-glucoside, aloin A, isoliquiritigenin, vitexin, picraquassioside A, isoeugenitol, kaempferol, psoralen, (±)-naringenin, apigenin, bergapten, resveratrol, pinolenic acid, 2-ethylhexyl ester-2-propenoic acid, n-hexadecanoic acid, ethyl iso-allocholate, bergapten, and 2-methyl-Z, Z-3,13-octadecadienol

Tang et al. (2020)

Lignan

Undescribed lignan

Ye et al. (2021)

Leaves

Ursane triterpenoids

α-Amyrin acetate, 3β-acetoxy-11α-hydroxy- 12-ursenes, and 1β,3β,11α-trihydroxy-urs-12-enyl-3-stearate

Thien et al. (2021)

Phenolics

p-Coumaric acid and isovitexin

Dai et al. (2020)

Ethanolic (95%)

Roots

Phenolics

Cyclomorusin, 3-O-[(6-O-E-sinapoyl)-β-D-glucopyranosyl]-(1 → 2)-β-D-glucopyranoside, 3,5,4′-trihydroxy-6,7,3′-trimethoxyflavone, quercetin, tricin, acacetin, luteolin, apigenin, (E)-suberenol, meranzin hydrate, methyl eugenol(11),3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, methyl chlorogenate, and emodin

Zheng et al. (2013)

Fruits

Isoflavonoids

1-Methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-β-carboline-3-carboxylic acid, methyl 1-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-β-carboline-3-carboxylate, vomifoliol, dehydrovomifoliol, icariside B2, dihydrophaseic acid, pubinernoid A, pinocembrin-7-O-β-D-glucoside, naringenin-7-O-β-D-glucoside, eriodictyol-7-O-β-D-glucoside, and 1-phenylpropane-1,2-diol

Wan et al. (2017)

Ethanolic (60%)

Roots

Phenolic glycosides

Ficusides A-G, 3,4-dimethoxyphenyl-1-O-β-D-apiofuranosyl (1 → 2)-β-D-glucopyranoside, khaephuoside A, 2-methoxyphenol-O-β-D-apiofuranosyl-(1 → 2)-β-D-glucopyranoside, methyl 2-hydroxybenzoate 2-O-β-D-apiofuranosyl-(1 → 2)-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, markhamioside F, benzyl-O-β-D-apiofuranosyl-(1 → 2)-β-D-glucopyranoside, 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl 1-O-β-apiofuranosyl (1′'→6′)-β-glucopyranoside, di-O-methylcrenatin, 3,4-dimethoxyphenyl-β-D-glucopyranoside, phenyl β-D-glucopyranoside, 2,4,6-trimethoxy-1-O-β-D-glycoside, 2,6-dimethoxy-4-hydroxyphenol-1-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, uralenneoside, glucosyringic acid, 4-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy) benzoic acid and vanillic acid 4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, (1′R)-1′-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl) propan-1′-ol 4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, 3,4,5-Trimethoxybenzaldehyde, 4-(3′-hydroxypropyl)-2,6-dimethoxyphnol-3′-O-β-D-glucoside, and gentisic acid 5-O-β-D-xyloside

Ye et al. (2020)

Ethanolic (75%)

Roots

Phenolics

(Z)-3-[5-(6-O-β-D-Glucopyranosyl) benzofuranyl] methyl propenoate, (Z)-3-[5-(6-methoxy) benzofuranyl] propenoic acid, (10S)-6-(2ʹ-hydroxy-10-O-β-D-glucopyranoside)-7-hydroxycoumarin, (2S)-1-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-2-O-(2-methoxy-4- phenylaldehyde) propane-3-ol, psoralen, umbelliferon, 7-(2ʹ,3ʹ-dihydroxy-3́-methylbutoxy)-coumarin, nodakenetin, (1R, 2R, 5R, 6S)-6-(4-hydroxy-3, 5-dimethoxyphenyl)-3, 7-dioxabicyclo [3, 3, 0] octan-2-ol, (+)-(7R, 8R)-4-hydroxy-3,3ʹ,5ʹ-trimethoxy-8ʹ,9ʹ-dinor-8,4ʹ-oxyneoligna-7,9-diol-7ʹ-aldehyde, (-)-(7S,8R)-4-hydroxy-3,3ʹ,5ʹ-trimethoxy-8ʹ,9ʹ-dinor-8,4ʹ-oxyneo-ligna-7,9-diol-7ʹ-aldehyde, (1R, 2R, 5R, 6S)-6-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-3,7-dioxabicyclo [3,3,0] octan-2-ol, (-)-pinoresinol, 2-[4-(3-hydroxy

propyl)-2-methoxyphenoxy] propane-1, 3-diol, vanillin, 3ʹ-hydroxy-4ʹ-metoxy-trans- cinnamaldehyde, vanillin acid, β-hydroxypropiovanillone, 7-O-ethylguaiacylglycerol, evofolin-B, (E)-3-[5-(6-methoxy) benzofuranyl] propenoic acid, (E)-isopsoralic acid 1 → 6-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, (Z)-isopsoralic acid1 → 6-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, phenyl β-D-glucopyranoside, 2, 3-dihydroxy-1-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-propan-1-one, 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzyl β-D-glucopyranoside, 3,4-dimethoxyphenyl-1-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, 3,4,5-trimethoxy phenoltetraacetyl-β-D- glucopyranoside, and 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzeneCheng et al. (2017b)

n-Hexane

Leaves

Oleanane

triterpenoids3β-Hydroxy-11-oxo-olean-12-enyl-3-stearate, taraxerol, 3β-acetoxy-11α-methoxy-12-ursene and 3β-acetoxy-11α-hydroxy-12-ursene

Thien et al. (2019)

F. hispida

Ethanolic

Stem bark and leaves

Unusual 8,4′-oxyneolignan-alkaloid

Hispidacine

Yap et al. (2015)

Phenanthroindolizidine alkaloids

Hispiloscine and (+)-deoxypergularinine

Twigs and leaves

Amine alkaloids with a rhamnosyl moiety

Ficuhismines A–D, ficushispimine C, magnosprengerine, and ficushispimine A

Jia et al. (2020)

Twigs

Pyrrolidine alkaloids

Ficushispimine A and ficushispimine B

Shi et al. (2016)

Pyrrolidine alkaloids

Ficushispimine A and ficushispimine B

ω-(Dimethylamino)caprophenone alkaloid

Ficushispimine C

Indolizidine alkaloid

Ficushispidine

Isoflavones

Isoderrone, 3′-(3-methylbut-2-en-1-yl)biochanin A, myrsininone A, ficusin A, and 4′,5,7-trihydroxy-6-[(1R*,6R*)-3-methyl-6-(1-methylethenyl)cyclohex-2-en-1-yl]isoflavone

Chloroform

Leaves and twigs

Phenanthroindolizidine alkaloid

O-Methyltylophorinidine

Peraza-Sánchez et al. (2002)

Norisoprenoid

Ficustriol

Hexane

Fruits

Isoflavonoids

Isowigtheone hydrate, 3′-Formyl-5,7-dihydroxy-4′-methoxyisoflavone, 5,7-dihydroxy-4′-methoxy-3′-(3-methyl-2-hydroxybuten-3-yl) isoflavone, and alpinumisoflavone

Zhang et al. (2018)

Coumarin

7-Hydroxycoumarin, 7-hydroxy-6-[2-(R)-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-3-enyl] coumarin, psoralen, and (–)-marmesin

Phenolics

Chlorogenic acid, chlorogenic acid methyl ester, chlorogenine glycoside, protocatechuic acid, gallic acid, benzyl β-D-glucopyranoside, 2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxy phenyl) ethyl β-D-glucopyranoside

Indole alkaloid

Murrayaculatine

Triterpenoids

Betulinic acid, and sitosterol 3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

Methanolic

Fruits

Isoflavone

5,7-Dihydroxy-4′-methoxy-3′-(3-methyl-2-hydroxybuten-3-yl) isoflavone

Cheng et al. (2021)

F. lacor

Ethanolic

Aerial roots

Triterpenoids

β-Sitosterol, lupeol, α-amyrin, β-amyrin, stigmasterol, and campesterol

Sindhu and Arora (2013a, b); Ghimire et al. (2020)

Phenolics

Scutellarein glucoside, scutellarein, infectorin, sorbifolin, bergaptol, and bergapten

F. lyrata (Syn. F. pandurata Sand)

Methanolic

Leaves

Flavonoids

(Epi)-catechin digalloyl rhamnoside, (epi)afzelechin-(epi) gallocatechin, epicatechin, (epi)afzelechin-(epi)catechin, (epi)afzelechin(epi)afzelechin-epigallocatechin, benzyl rutinoside, lucenin-2, vicenin-2, rutin, orientin, 3-O-p-coumaroyl epigallocatechin, isoquercetin, luteolin, quercetin, apigenin, and ficuisoflavone

Farag et al. (2014)

F. microcarpa

Ethanolic

Leaves

Triterpenoids

29(20 → 19)Abeolupane-3,20-dione, 19,20-secoursane-3,19,20-trione, (3β)-3-hydroxy-29(20 → 19)abeolupan-20-one, lupenone, and α-amyrone

Hsiung and You (2004)

Aerial roots

Triterpenoids

3β-Acetoxy-11α-hydroxy-11(12 → 13)abeooleanan-12-al, 3β-hydroxy-20-oxo-29(20 → 19)abeolupane, and 29,30-dinor-3β-acetoxy-18,19-dioxo-18,19-secolupane

Chiang and Kuo (2002)

3β-Acetoxy-12,19-dioxo-13(18)-oleanene, 3β-acetoxy-19(29)-taraxasten-20α-ol, 3β-acetoxy-21α,22α-epoxytaraxastan-20α-ol, 3,22-dioxo-20-taraxastene, 3β-acetoxy-11α,12α-epoxy-16-oxo-14-taraxerene, 3β-acetoxy-25-methoxylanosta-8,23-diene, 3β-acetoxy-11α,12α-epoxy-14-taraxerene, 3β-acetoxy-25-hydroxylanosta-8,23-diene, oleanonic acid, acetylbetulinic acid, betulonic acid, acetylursolic acid, ursonic acid, ursolic acid, and 3-oxofriedelan-28-oic acid

Chiang et al. (2005)

Peroxy triterpenoids

3β-Acetoxy-12β,13β-epoxy-11α-hydroperoxyursane, 3β-acetoxy-11α-hydroperoxy-13αH-ursan-12-one, 3β-acetoxy-1β,11α-epidioxy-12-ursene, (20S)-3β-acetoxylupan-29-oic acid, (20S)-3β-acetoxy-20-hydroperoxy-30-norlupane, and 3β-acetoxy-18α-hydroperoxy-12-oleanen-11-one, and 3β-acetoxy-12-oleanen-11-one

Chiang and Kuo (2001)

Methanolic

Syconia

Terpenes

α-Cubebene, 1,2,4-metheno-1H-indene, 3,7-dimethyl-1,3,6-octatriene, (E,E)-2,4-hexadiene, caryophyllene, copaene, and D-limonene

Zhang et al. (2017)

Stem bark

Phenolics

Protocatechuic acid, chlorogenic acid, methyl chlorogenate, catechin, epicatechin, procyanidin B1, and procyanidin B3

Ao et al. (2010)

F. mollis

Methanolic

Stem

Monoterpenes

Sulfurous acid, octadecyl 2-propyl ester, tetratetracontane, hexatriacontyl pentafluoropropionate, octatriacontyl pentafluoropropionate, octacosyl trifluoroacetate, hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester, heptacosanoic acid, and 25-methyl-, methyl ester

Priya and Abinaya (2018)

F. palmata

Methanolic

Fruit

Phenolics

Rutin, isoquercitin, quercitin, kaempferol, luteolin, and cinnamic acid

Sharma et al. (2021)

F. pumila

Chloroform

Stem

Flavonoid glycosides

Astragalin, isoquercitrin, apigenin 6-C-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 2)-β-D-glucopyranoside, kaempferol 3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl- (1 → 6)-β-D-glucopyranoside and kaempferol 3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1 → 6)-β-D-galactopyranoside, rutin and isorhamnetin-3-O-glucoside, apigenin, taxifolin, tricetin, luteolin, hesperitin, and chrysin

Pistelli et al. (2000)

n-Hexane

Stem

Triterpenoids

β-Sitosterol, α-amyrin, taraxasterol and 11α-hydroxy-β-amyrin

Chloroform

Leaves

Furanocoumarin derivatives

Bergapten and oxypeucedanin hydrate

Juan et al. (1997)

Aqueous Pb(OAc)2 solution

Leaves

Triterpenoids

Neohopane

Ragasa et al. (1999)

Ethanolic

Leaves

Norisoprenoids

3,9-Dihydroxy dihydro actinidiolide, 3α-hydroxy-5,6-epoxy-7-megastimen-9-one, dehydrovomifoliol, 3,9-dihydroxy-5,7-megastigmadien-4-one, 9,10-dihydrox-y-4,7-megastigmadien-3-one, 8,9-dihydro-8,9-dihydroxymegastigmatrienone, (6R,9S)-3- oxo-α-ionol, blumenol A, (E)-3-oxo-retro-α-ionol, (6R,9R)-3-oxo-α-ionol-β-d-glucopyranoside, roseoside, and (E)-4-[3′-(β-D-glucopyranosyloxy)butylidene]-3,5,5-trimethyl-2-cyclohexen-l-one

Bai et al. (2019)

Benzofuran derivative

Pumiloside

Trinh et al. (2018)

Flavonoid glycosides

Afzelin, astragalin, quercitrin, isoquercitrin, kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside, rutin and kaempferol 3-O-sophoroside

Flavonoids and phenolic acids

Rutin, kaempferol 3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl (1 → 6)-β-D-glucopyranoside, isoquercitrin, quercitrin, dihydrokaempferol 5-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, dihydro-kaempferol 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, maesopsin 6-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, secoisolariciresinol 9-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, chlorogenic acid, protocatechuic acid, caffeic acid, 5-O-caffeoyl quinic acid methyl ester(12), p-hytroxybenzoic acid, vanillic acid, and 5-O-caffeoyl quinic acid butyl ester

Wei et al. (2014)

Ethyl acetate

Roots

Dinorsesquiterpenoids

(6S,9R)-Vomifoliol and (6S)-dehydrovomifoliol

Nguyen and Nguyen (2021)

Stems and roots

Sesquiterpenoids

Phaseic acid, and methyl (2α,3β)-2,3-dihydroxy-olean-12-en-28-oate

Aqueous- ethanol (50:50)

Leaves

Flavonoid glycosides

Rutin, apigenin 6-neohesperidose, kaempferol 3-robinobioside and kaempferol 3-rutinoside

Leong et al. (2008)

Methanolic

Fresh fruits

Acetylated dammarane- triterpenoids

3β-Acetoxy-22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27-hexanordammaran-20-one, 3β-acetoxy-20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27-octanordammaran-17β-ol, 3β-acetoxy-(20R, 22E, 24RS)-20, 24-dimethoxydammaran-22-en-25-ol and 3β-acetoxy-(20S, 22E, 24RS)-20, 24-dimethoxydammaran-22-en-25-ol

Kitajima et al. (1999, 2000)

Sesquiterpenoid glucosides

Pumilasides A, B and C

F. racemosa (syn. F. glomerata)

Ethanolic

Stem bark

Flavonoids

Kaempherol, Quercetin, Naringenin, and Baicalein

Keshari et al. (2016)

Triterpenoid

Lupeol

Joshi et al. (2016)

Anthocyanins

Gluanol acetate, leucocyanidin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranc oside, leucopelargonidin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, leucopelargonidin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside, ceryl behenate

Joy et al. (2001)

Triterpenoids

Lupeol acetate, and α-amyrin acetate, lupeol, friedelin, behenate, stigmasterol, β-sitosterol, β-sitosterol-D-glucoside, bergenin, racemosic acid, friedelin β-sitosterol, β-amyrin, and lupeol acetate

Nguyen et al. (2001); Malairajan et al. (2006); Veerapur et al. (2007)

Fruits

Triterpenoids

β-Sitosterol, gluanol acetate, hentriacontane, tiglic acid, taraxasterol, lupeol acetate, and α-amyrin acetate

Singhal and Saharia (1980);Narender et al. (2009)

Methanolic

Stem bark

Tetracyclic triterpenoids

Gluanol acetate

Rahuman et al. (2008)

Leaves

Tetraterpenoids

Tetra triterpene, glauanolacetate, and racemosic acid

Patil et al. (2010)

n-Hexane

Stem bark

Triterpenoids

Lupeol, lupeol acetate, and β-sitosterol

Bopage et al. (2018)

Root

Triterpenoids

Cycloartenol, euphorbol, taraxerone, and tinyatoxin

Varma et al. (2009)

Latex

Triterpenoids

α-Amyrin, β-sitosterol, cycloartenol, cycloeuphordenol, 4-deoxyphorbol and its esters, euphorbinol, isoeuphorbol, taraxerol, tinyatoxin, and trimethylellagic acid

Paarakh (2009)

F. religiosa

Methanolic

Stem bark

Naphthyl substituted phytosterol

β-Sitosteryl naphthadiolyl linoleinate

Ali et al. (2017, 2020)

Lanostane type-triterpenic

Lanostanoic acid oleate

Naphthyl esters

Lanostanoic acid linolenate, Lanostanoic acid and naphthadiolyl linoleiate

Ali et al. (2014)

Steroids

β-Sitosterol glucoside and β-sitosteryl oleate

Leaves

Phenolics

Eugenol, and tannic acid

Poudel et al. (2015); Rathod et al. (2018)

Monoterpenes

Phytol, linalool, α-cadinol, α-eudesmol, β-eudesmol, epi-α-cadinol, γ-eudesmol, and epi-γ-eudesmol

Triterpenoids

Lupeol α-amyrin, campestrol, and stigmasterol

Murugesu et al. (2021)

Ethanolic

Stem bark

Phenolics

Leucopelargonidin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, leucopelargonidin-3-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside, leucoanthocyanidin, leucoanthocyanin, bergapten, and bergaptol

Sirisha et al. (2010); Wilson et al. (2016)

Triterpenoids and their derivatives

Lanosterol, lupen-3-one, β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, β-sitosterol-D-glucoside, lupeol acetate, and α-amyrin acetate

Stem

Phenolics

2,6-Dimethoxyphenol, n-hexadecanoic acid, octadecanoic acid, 4H-pyran-4-one,2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl, and 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)

Manorenjitha et al. (2013)

n-Hexane

Stem

Triterpenoids

Stigmasterol, lanosta-8,24-dien-3-ol, acetate(3β), and ergost-5-en-3-ol(3β)

Ethanolic

Roots

Phenolics

Ceryl behenate, leucocyanidin-3-O-β-D-glucopyrancoside, leucopelargonidin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, leucoanthocyanidin, and leucoanthocyanin

Goyal (2014)

Triterpenoids

Lupeol acetate, α-amyrin acetate, lupeol, and β-sitosterol

Fruits

Monoterpenes

β-Caryophyllene, α-terpinene, dendrolasine, α-trans bergamotene, (e)-β-ocimene, α-pinene, limonene, dendrolasine, α-ylangene, α- thujene, α-copaene, β-bourbonene, aromadendrene, δ-cadinene, α-humulene, β-pinene, alloaromadendrene, germacrene, γ-cadinene, bicyclogermacrene [undecane, tridecane, and tetradecane

Rathee et al. (2015); Verma and Gupta (2015)

Triterpenoids

Stigmasterol and lupeol

F. retusa

Ethanolic (96%)

Aerial parts

Polyphenolic

retusaphenol [2-hydroxy-4-methoxy-1,3-phenylene-bis- (4-hydroxy-benzoate)], (+)-retusa afzelechin [afzelechin - (4α → 8) - afzelechin - (4α → 8) - afzelechin], luteolin, (+) - afzelechin, (+)-catechin, and vitexin

Sarg et al. (2011)

Triterpenoids

β-Sitosterol acetate, β-amyrin acetate, moretenone, friedelenol, β-amyrin and β-sitosterol

F. sarmentosa

Methanolic

Stem and leaves

Flavonoids

Eriodictyol, homoeriodictyol, dihydroquercetin, luteolin, quercetin, dihydroquercetin, kaempferol, dihydrokaempferol, naringenin, luteolin, apigenin, chrysoeriol, and 3′,5′,5,7-tetrahydroxylfavanone

Wang et al. (2010a, b)

7-Hydroxycoumarin, apigenin, eriodictyol, and quercetin

Wang et al. (2016)

F. semicordata

Ethanol (70%): acetic acid: formalin (90:5:5%)

Leaves and fruits

Aflatoxins

Aflatoxin B1, aflatoxin B2, aflatoxin G1, and aflatoxin G2

Gupta and Acharya (2019)

Ethanolic

Leaves

Phenolics

Gallic acid and quercetin

Kaur et al. (2017)

Stem

Phenolics

Gallocatechin, epigallocatechin, catechin, rutin, quercetin, quercetrin, (+)-catechins, quercetin and quercitrin

Nguyen (2002); Gupta et al. (2019); Al-Snafi (2020)

Methanolic

Fruits

Monoterpenes

α-Thujene, α-Pinene, sabinene, β-pinene, β-myrcene, limonene,1,8-cineole, (Z)-β-ocimene, (E)-β-ocimene,γ-terpinene, terpinolene, linalool, and perillene

Chen et al. (2009)

Sesquiterpenes

Ylangene, α-copaene, β-panasinsene, β-cubebene, β-elemene, α-gurjunene, β-caryophyllene, α-humulene, alloaromadendrene, γ-muurolene, germacrene D, β-Selinene, α-selinene, α-muurolene, (E,E)-α-farnesene, and δ-cadinene

F. tikoua

Ethanolic (95%)

Whole plant

Isoprenylated flavonoids

Ficustikousins A and B, derrone, alpinumisoflavone, (S)- 5,7,3′,4′-tetrahydroxy-2′-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)flavanone, (S)-paratocarpin K, 3′-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)biochanin A, and genistein

Wu et al. (2015)

Coumarin

Bergapten

Benzofuran glucoside

6-Carboxyethyl-5-hydroxybenzofuran 5-O-β-d-glucopyranoside, and 6-carboxyethyl-7-methoxyl-5-hydroxy-benzofuran 5-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

Wei et al. (2011b)

Rhizome

Isoflavonoids

Ficusin C, 6-[(1R*,6R*)-3-methyl-6-(1-methylethenyl)-2-cyclohexen-1-yl]-5,7,4′- trihydroxyisoflavone, ficusin A, alpinumisoflavone, 4′-O-methylalpinumisoflavone, and quercetin

Fu et al. (2018)

Methanolic

Stem

Pyranoisoflavone

5,3′,4′-trihydroxy-2″,2″-dimethylpyrano (5″,6″:7,8) isoflavone

Wei et al. (2012)

Isoflavones

Wighteone and lupiwighteone

Isoflavanone

Ficustikounone A

Zhou et al. (2018)

Ethanolic (90%)

Stem

Phenolic glycosides

2-Ethylene-3,5,6-trimethyl-4-phenol-1-O-β-D-xylopyranosyl-(1 → 6)-β-D-glucopyranoside, 3-methoxy-4-O-β-D-apiofuranosyl-(1 → 2)-β-D-glucopyranosylpropiophenone, 3-hydroxy-1-(4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-3-methoxyphenyl)propan-1-one, 4-hydroxy-3,5-bis(3′-methyl-2-butenyl)benzoic acid-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenol-1-O-β-D-apiofuranosyl-(1 → 6)-β-D-glucopyranoside, 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenol-1-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, 3-methoxy-4-O-β-D-apiofuranosyl-(1 → 6)-β-D-glucopyranosylpropiophenone, baihuaqianhuoside, 3,5-dimethoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic acid-O-β-D-glucopyranoside and 2-methoxy-4-allylphenyl-1-O-β-D-apiofuranosyl-(1 → 6)-β-D-glucopyranoside

Jiang et al. (2013)

3.3 Pharmacological attributes

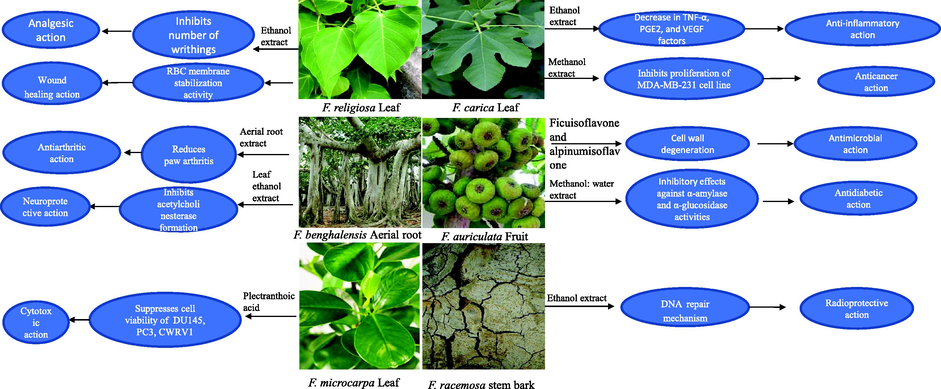

Indian Ficus species possess analgesic (Marasini et al., 2020), antioxidative (Etratkhah et al., 2019), antidiabetic (Anjum and Tripathi, 2019b), anti-inflammatory (Sabi et al., 2022), antiarthritic (Mathavi and Nethaj, 2019), anti-stress (Murugesu et al., 2021), anticancer (Jain and Jegan, 2019), hepatoprotective (El-hawary et al., 2019), neuroprotective (Hassan et al., 2020), antimicrobial (Raja et al., 2021), radioprotective (Vinutha et al., 2015), and wound healing (Ansari et al., 2021) properties. The summary and related mechanisms of various pharmacological activities are presented in Table 3 and Fig. 4.

Pharmacological activity

Plant species

Used plant parts

Tested extract/ compound

Tested concentration/dose

Tested model/mode of administration

Study outcomes

References

Analgesic activity

F. benghalensis

Stem bark

Aqueous

400 mg/kg b.w./p.o.

Swiss albino mice/ tail-flick and formalin-induced pain assay/i.p.

Tail-flick model - extract (P < 0.001) increased mean tail-flick latency when compared to the control group/formalin-induced pain – extract significantly reduced pain response when compared with control group animals (P < 0.001)

Rajdev et al. (2018)

Methanol

400 mg/kg b.w./p.o.

Swiss albino mice/ acetic acid-induced writhing/i.p.

Extract prevented acetic acid induced writhing movements significantly in mice (P < 0.01) when compared to control

Thakare et al. (2010)

Leaves

Methanol

100 mg/kg b.w./p.o.

Swiss albino Wistar rats/ acetic acid-induced writhing and hot plate assays/i.p.

Extract showed maximum inhibition to writhing responses (43%) when compared to aspirin (20 mg/kg; P < 0.05)/maximum nociception inhibition of stimulus displayed by extract at 15 min (P < 0.05) in hot plate model

Mahajan et al. (2012)

F. carica

Fruits

Aqueous (boiled)

2000 mg/kg b.w./i.p.

Wistar male rats/ formalin-induced paw licking/i.p.

Extract showed no significant difference between control and extract treated animals (P > 0.05)

Mirghazanfari et al. (2019)

F. deltoidea

Leaves

Aqueous

100 mg/kg b.w./i.p.

Male ICR mice/acetic acid-induced abdominal writhing, formalin-induced pain, and hot plate assays/i.p.

Extract produced significant antinociceptive effect in tested assays when compared with control (P < 0.001)

Sulaiman et al. (2008)

Leaves and roots

Aqueous

200 mg/kg b.w./i.p.

Male ICR mice/ acetic acid-induced abdominal writhing (i.p.)/formalin (s.c.)-induced pain and hot plate assays

Extract produced significant antinociceptive effect in acetic acid-induced abdominal writhing (P < 0.001 compared to control)/extract showed significant inhibition in the early phase of the formalin-induced pain assay (P < 0.001 compared to control)/increased latency time significantly in the hot plate assay (P < 0.0001)

Salihan et al. (2015)

F. elastica

Stem bark

Methanol (98%)

10 mg/kg b.w./i.p.

Wistar albino rats/ acetic acid-induced writhing/i.p.

The inhibitory effect of extract on squirming count was significant (P < 0.05; compared to control)

Aziba and Sokan (2009)

F. exasperata

Leaves

Methanol

250 mg/kg b.w./i.p.

Swiss albino mice/ acetic acid-induced writhing/i.p.

Extract reduced the numbers of writhes (36.87%) when compared with control (69.7%; P < 0.001)

Zubair et al. (2014)

F. pumila

Stem and leaves

Methanol

1 g/kg b.w./p.o.

Male ICR mice/acetic acid-induced writhing and formalin-induced paw licking/i.p.

Extract significantly decreased writhing responses in the acetic acid assay (P < 0.01) and licking time in the formalin-induced pain (P < 0.001)

Liao et al. (2012)

F. racemosa (syn. F. glomerata)

Leaves

Ethanol

400 mg/kg b.w./i.p.

Male Swiss albino mice/ acetic acid-induced writhing and formalin-induced paw licking/i.p.

Extract displayed significant activity (P < 0.01) in acetic-induced writhing/extract showed significant reduction in paw biting and licking response (P < 0.01)

Ghawate et al. (2012)

F. religiosa

Leaves

Methanol

40 mg/kg b.w./p.o

Wistar albino rats/ tail flick latency period/ acetic acid- induced writhing in mice/i.p.

Extract found more effective (P < 0.01) in preventing acetic acid induced writhing and in increasing latency period in tail flick method (P < 0.01)

Gulecha et al. (2011)

Leaves and bark

Ethanol

400 mg/kg b.w./p.o.

Swiss albino mice/ Eddy’s hot plate and acetic acid-induced writhing/p.o.

Hot plate – both extracts increased latency time 70.81% (8.54 min) and 70.78% (8.53 min), respectively (P < 0.05)/ both extracts inhibited the number of writhings induced by acetic acid (P < 0.05)

Marasini et al. (2020)

Anti-inflammatory activity

F. benghalensis

Stem bark

Ethanol

600 mg/kg/day/b.w./p.o.

Wistar albino rats/ carrageenan-induced rat paw oedema and cotton pellet granuloma models/i.p.

Extract showed significant inhibition (69.04%; P < 0.05) after 3 h on carrageenan-induced paw edema/extract displayed significant (39.03%; P < 0.05) inhibition after 3 h on cotton pellet granuloma model

Patil and Patil (2010)

200 mg/kg b.w./p.o.

Sprague Dawley rats/ carrageenan-induced paw edema/i.p.

Extract (69.86%) showed significant (P < 0.0001) inhibition at 3 h on the carrageenan-induced inflammation

Wanjari et al. (2011)

Methanol

400 mg/kg b.w./p.o./given for 6 h

Wistar albino rats/carrageenan-induced paw edema/s.c.

Extract (3.8 ± 0.1 mL) and diclofenac sodium (2.9 ± 0.1 mL) elicited significant inhibition of edema formation at 3 h (P < 0.01)

Thakare et al. (2010)

300 mg/kg b.w./i.p. in case of FCA-induced edema arthritis, formalin –induced arthritis while p.o. in case of agar- induced

Swiss albino rats/FCA-induced edema arthritis/s.c./ formalin –induced arthritis/ agar- induced edema/i.p.

FCA-induced edema arthritis - extract exhibited significant inhibition (40.48%) when compared with acetyl salicylic acid (26.98%; P < 0.05)/ formalin-induced paw edema-extract displayed significant inhibition (69.9%) when compared with acetyl salicylic acid (67.72%; P < 0.05)/agar- induced edema-extract exhibited maximum inhibition which was as good as indomethacin (P < 0.01)

Manocha et al. (2011)

Methanol (70%)

60 µg/mL

RAW 246.7 cells/in vitro induced using LPS (500 ng/mL)

Significant decrease in the amount of uric acid, nitric oxide, lipid peroxidation and xanthine oxidase activity reported in treated cell (in vitro)

Sabi et al. (2022)

Leaves

Methanol

200 mg/kg b.w./p.o.

Wistar albino rats/formalin-induced inflammation/i.p.

Extract showed a significant (P < 0.001) decrease in paw volume at 3 h (inhibition 65.21% when compared to 62.31% of diclofenac)

Kothapalli et al. (2014)

F. benjamina

Leaves

Aqueous

264 mg/kg b.w./p.o.

Wistar male albino rats/ carrageenan-induced paw edema/i.p.

Extract showed significant anti-inflammatory (inhibition 39.715%) effects when compared to the negative control (inhibition 70.12%; P < 0.05)

Bunga and Fernandez (2021)

F. carica

Leaves

Ethanol

600 mg/kg b.w/p.o.

Wistar albino rats/ carrageenan-induced paw edema/i.p.

Extract showed (75.90%; P < 0.05) significant inhibition after 3 h when compared with indomethacin (79.72%)

Patil and Patil (2011)

Wistar albino rats/carrageenin, serotonin, histamine, dextran-induced rat paw oedema/i.p.

Extract exhibited maximum anti-inflammatory effect (inhibition 33.73%) at the end of 3 h on carrageenin, serotonin, histamine, and dextran-induced rat paw oedema when compared to indomethacin (P < 0.001)

Patil et al. (2013)

Extract gel (carbopol 940 base swelling + fig leaves)

Rats were topically treated for 3 days

BALB/c rats/croton oil-induced inflammation on the back of rats

The gel displayed significant differences in the treatment group (P = 0.688 negative control; gel P = 0.470)

Kurniawan et al. (2021)

Methanol (50%)

500 mg/kg b.w./p.o.

Wistar albino rats/ formalin-induced rat paw oedema/ i.p.

Extract showed significant inhibition (66.43%) after 4 h (P < 0.001) of administration

Ali et al. (2009, 2012)

Methanol

50 mg/pouch

Male Wistar albino rats/ carrageenan-induced pouches/ i.p.

Extract significantly reduced the formation of TNFα, PGE2, and VEGF, while angiogenesis was significantly suppressed when compared to diclofenac (

< 0.001)

Eteraf-Oskouei et al. (2015)

Branches

Ethyl acetate

–

RAW264.7 cells/in vitro assay

Extract suppressed nitric oxide formation in RAW264.7 cells. The level of tumor necrosis factor-α was significantly decreased (P < 0.01)

Park et al. (2013)

Fruits

Ficucaricones A–D

0.89 ± 0.05 to 8.49 ± 0.18 μM

RAW264.7 cells/in vitro assay

Compounds showed significant anti-inflammatory effects (IC50 0.89 ± 0.05 to 8.49 ± 0.18 μM)

Liu et al. (2019)

F. deltoidea

Leaves

Aqueous

300 mg/kg b.w./p.o.

Wistar albino rats/carrageenan-induced paw edema, cotton pellet-induced granuloma/i.p.

Extract showed significant (P < 0.05) anti-inflammatory activity in all tested assays

Zakaria et al. (2012)

Methanol

–

Wistar albino rats/lipoxygenase inhibitory activity/ hyaluronidase inhibition assay and 12-otetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA)-induced ear oedema

Extract exhibited 10.35 ± 0.04% inhibition in case of lipoxygenase activity/ extract showed 51.0% inhibition in case of hyaluronidase inhibition assay/extract showed strong decrease of oedema (85.46 ± 8%; P < 0.05) in (TPA)-induced ear oedema

Abdullah et al. (2009); Ashraf et al. (2021)

F. elastica

Root bark

Aqueous

10 mg/kg b.w./p.o.

Male Wistar albino rats/ carrageenin-induced paw oedema/i.p.

Extract and indomethacin produced potent inhibition (68.92% and 69.26%) to paw edema

Sackeyfio and Lugeleka (1986)

Stem bark

Methanol (98%)

10 mg/kg b.w/p.o.

Wistar albino rats/carrageenan-induced paw oedema/i.p.

Extract significantly inhibited carrageenan induced inflammation when compared with control (P < 0.05)

Aziba and Sokan (2009)

F. erecta

Leaves

Dichloromethane

1 μg/mL

Raw 264.7 murine macrophage cell lines /LPS-induced in vitro assay

Extract inhibited the production of pro-inflammatory factors (NO, iNOS, COX-2, and PGE2)

Jung et al. (2018)

F. exasperata

Stem bark

Ethanol (70%)

300 mg/kg b.w./p.o

Male Wistar rats/carrageenan- induced foot edema/i.p.

Extract significantly suppressed carrageenan induced foot edema (68.57 ± 3.342%) when compared to diclofenac (71.56 ± 3.43%) and dexamethasone (74.53 ± 5.21%)

Amponsah et al. (2013)

F. hirta

Roots

(1′S)-methoxy-4-(1-propionyloxy-5-methoxycarboxyl-pentyloxy)- (E)-formylviny, (8R)-4,5′-dihydroxy-8-hydroxymehtyl-3′-methoxydeoxybenzoin, (2′S)-3-[2,3-dihydro-6-hydroxy-2-(1-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)-5- benzofuranyl] methyl propionate, 3-[6-(5-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl) benzofuranyl] methyl propionate

–

Murine macrophage RAW 264.7 cells/in vitro assay