Translate this page into:

TiO2-coated graphene oxide-molybdate complex as a new separable nanocatalyst for the synthesis of pyrrole derivatives by Paal-Knorr reaction

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

The preparation of chemical and pharmaceutical compounds through organic reactions has always been associated with the production of environmental waste. Growth population and concerns about ecological pollution increase the interest in using heterogeneous solid catalysts with capabilities such as increasing reaction efficiency and reducing the production of by-products, as well as the ability to separate and reuse. To develop and benefit such catalysts as much as possible, in this study, using graphene oxide (GO) as a support, we succeeded in preparing a heterogeneous catalyst with a high contact surface, excellent performance, and recyclability. Graphene oxide nanosheets were synthesized according to Hummer’s method. hexamolybdate anions ([n-Bu4N]2[Mo6O19]) were placed on this support as a catalytically active site using linkers. The structure of this catalyst was confirmed by XRD, FT-IR, EDS, SEM, TEM, TGA, Raman, and nitrogen adsorption–desorption analyses, and it was used to produce pyrroles by the Paal-Knorr method. The performance of the synthesized nanocatalyst was satisfactory for all the derivatives studied. Recovery and reuse of GO@TiO2@(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] after catalytic reactions were examined. This catalyst could be quickly recovered by simple filtration and recycled ten times without significant loss of its catalytic activity.

Keywords

Graphene oxide

Molybdate

Nanocatalyst

Paal-Knorr reaction

Pyrrole

1 Introduction

The development of catalytic reactions is one of the requirements of environmentally friendly processes. Therefore, the use of green and recyclable catalysts has attracted much attention. Catalysis includes the varieties of homogeneous, heterogeneous, and biological catalysis. Homogeneous catalysts offer many vital advantages over their heterogeneous counterparts. For example, they often show high chemoselectivity, regioselectivity, and enantioselectivity in organic transformations (Ren et al., 2021; Sheldon, 2001). Despite these benefits, most homogeneous catalysts have not been commercialized owing to the problematic separation of them from the reaction mixture and solvent (Cole-Hamilton, 2003). Immobilizing homogeneous catalysts on various supports, such as carbon, silica, metal oxide, polymer, and nanocomposites, is one of the efficient ways to overcome this problem. Immobilized catalysts possess main benefits such as ease of handling, low solubility, the possibility of recovery, and low toxicity. Stabilization of the catalyst on solid supports, in addition to increasing the surface area of the catalyst, helps to remove the catalyst from the reaction mixture easily (Bogdan et al., 2007; Celebi et al., 2016; Dai et al., 2017; Davies et al., 2001; Deebansok et al., 2021; Fei et al., 2017; Hutchings 2009; Hattori et al., 2015; Shi et al., 2017; Sudarsanam et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2018). In this sense, carbon materials are arguably the most extensively investigated and emerged as appealing catalyst supports because they are eco-friendly, cheap and, non-toxic (Fidalgo and Menendez, 2011; Yang et al., 2011). Numerous studies have been performed on these Carbonous materials as catalyst support, such as carbon nanotubes (Chizari et al., 2010; Rümmeli et al., 2007; Esteves et al., 2018), carbon-polymer composites (Memioğlu et al., 2014), mesoporous carbons (Ambrosio et al., 2009; Calvillo et al., 2011; Joo et al., 2008; Min et al., 2008), graphitized carbons (Wang et al., 2008), nitride graphitized carbons (Yao et al., 2019), graphene (Hu et al., 2015; Kidambi et al., 2013; Marinkas et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2013), and graphene oxide (GO) (Dreyer et al., 2010; Joshi et al., 2021; Pyun, 2011; Su et al., 2012; Su and Loh, 2013). Graphene oxide as a new nanocomposite has received a lot of consideration due to its unique mechanical and physical properties, high mechanical strength, chemical and thermal stability, unique layered structure, and flexibility (Zhang et al., 2017). This compound with a substantial surface capability can be a promising candidate in the very diverse application as a beneficial heterogeneous catalyst and catalyst support and can be proper support for metals and metal oxides due to its oxygen-containing functional groups on its surface (Akhavan et al., 2010; Ayyaru et al., 2020; Fan et al., 2011; Gao et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2011; Karimi et al., 2016; Khodabakhshi and Karami, 2014; Kim et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2021; Park et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2021). GO has been functionalized with different groups such as carboxylic acid, hydroxyl, and epoxide making GO a solid acid catalyst to many kinds of chemical reactions (Zhang et al., 2011; Pyun, 2011). The presence of these functional groups makes it possible to modify the surface of graphene oxide through covalent and non-covalent processes (singha et al., 2021). Surface coating is one of the approaches often applied in modifying or improving GO performance. Recently, titanium dioxide (TiO2) has also been used as a coating agent for this purpose because of its advantages as cost-effectiveness, low toxicity, and chemical stability. For example, in 2013, Anandan et al. used a coating of TiO2 on GO support to prepare an effective photocatalyst (Anandan et al., 2013).

Recently, inorganic/organic hybrid materials have been widely used in organic reactions as a catalyst, because they are well-matched with various processes of eco-friendly chemical transformations (Sanchez et al., 2005). This quickly growing field is producing several exciting new materials with novel properties. They gather together typical advantages of organic components like flexibility, low density, toughness, and formability, with the ones displayed with specific inorganic materials like hardness, chemical resistance, strength, optical properties, among others (Barud et al., 2008). The properties of these materials are not only the sum of the individual contributions of both phases, but the role of the internal interfaces could be substantial. Organic/inorganic grafted materials have appeared as superseded materials to design unique products and formed a new field of academic studies.

The idea of monomolecular bifunctional catalyst for helpful catalysis was first presented in 2003 And since then, both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts with molecular design and application in organic reactions have become the focus of attention (Xue et al., 2015). In this regard, polyoxometalates (POMs) are an essential class of polynuclear clusters of nanoscales. In these compounds, transition metals with their highest oxidation state and oxygen bridges are present, which cause substantial physical and chemical properties in them (Zarnegaryan et al., 2016; Zhong et al., 2021). Polyoxometalate clusters, in addition, to having huge sizes and exciting properties for medicine and nonlinear optics, are a prominent class of linkers to prepare interpenetrating networks. Directly applying POM clusters as linkers promise to be an appealing route to design new entangled network structures. The chief properties of polyoxometalates and variation of the systems of polyoxometalates endow them with solid potential for applications in different areas of chemical projects (Shi et al., 2006). Despite the benefits mentioned, the solubility and non-recoverability of POMs in various media, limit their applications in some procedures. Immobilizing these clusters on solid supports such as silica and magnetic nanoparticles could be an essential way to overcome this problem. Hexamolybdates are a group of POMs that have been used in several inorganic and organic reactions due to their thermal stability and radiation resistance. Lindqvist-type hexamolybdate cluster, [Mo6O19]2−, as a unique class of metal oxide clusters, is an ideal building block for constructing the organic–inorganic hybrid assemblies (Kargar et al., 2020; Neysi et al., 2019).

Many chemists have paid much attention to developing novel approaches for the preparation of nitrogen-containing heterocycles, which play vital roles in our life. They are part of many natural products, fine chemicals, and biologically active pharmaceuticals that are important for enhancing the quality of life (Azarifar et al., 2012). Pyrrole rings are among the most important heterocyclic compounds used in material science, medicines, natural products, catalysts, etc. (Agarwal and Knölker, 2004; Bando and Sugiyama, 2006; Gupton, 2006; Kel'in et al., 2001; Michlik and Kempe, 2013; Neto and Zeni, 2020; Zhang et al., 2021). Different derivatives of pyrrole have anti-tumor (Hu et al., 2020), anti-inflammatory (Battilocchio et al., 2013; Fernandes et al., 2004), hypolipidemic (Bellina and Rossi, 2006), and antimicrobial (Castro et al., 1967; Raimondi et al., 2006,) properties. They have also been used as useful synthetic intermediates in some organic syntheses. Consequently, many methods for synthesizing diversely substituted pyrroles have been developed (Alberola et al., 1999; Bellingham et al., 2004; Gourlay et al., 2006; Leonardi et al., 2018; Miles et al., 2009, Trautwein et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2014). However, the Paal-Knorr reaction is the most reliable method for synthesizing pyrrole derivatives (Braun et al., 2001; Mothana and Boyd, 2007; Wang et al., 2004).

In continuation of our program aimed at developing new methodologies for the preparation of green-supported catalysts (Farahi et al., 2015; Farahi et al., 2016; Farahi et al., 2017; Farahi and Abdipour, 2018; Gholtash et al., 2020; Karami et al., 2014; Karami et al., 2015; Karami et al., 2018; Tanuraghaj and Farahi, 2018; Tanuraghaj and Farahi, 2019), we have reported preparation and characterization of POM grafted on TiO2-coated GO (GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18]) as a new hybrid material. Furthermore, its catalytic application was studied in the synthesis of pyrrole derivatives by the Paal-Knorr reaction. In this new nanocatalyst, we used graphene oxide as heterogeneous support. Loading the POM complex onto this solid support contributes to the high catalytic performance and solves the problem of separating the catalyst from the reaction mixture. High contact surface, high production efficiency in short reaction time, separation capability with a simple filtration, and the ability to reuse the catalyst up to ten times, are the important advantages of this novel synthesized catalyst.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials and methods

All chemicals were commercially available from Merck, Aldrich, and Fluka chemical companies and used without further purification. X-ray diffraction analysis was studied using a Philips X Pert Pro X diffractometer operated with Ni-filtered Cu-Ka radiation. Scanning electron microscopy was performed by SEM: KYKY-EM3200 instrument operated at 26 kV. An electrothermal KSB1N apparatus was used to obtain the melting point. IR spectra were recorded using an FT-IR JASCO FT-IR/680 spectrometer instrument. NMR spectra were taken with a Bruker 400 MHz Ultrashield spectrometer at 400 MHz (1H) and 100 MHz (13C) using CDCl3 as the solvent. EDS was determined using the TESCAN vega model instrument. Thermogravimetric analysis was performed by heating at 25–900 °C.

2.2 Procedure for the synthesis of graphene oxide (GO)

Graphene oxide was prepared according to the modified Hummer method (Hummers et al., 1958). Graphite powder (3 g), H2SO4 (12 mL), K2S2O8 (2.5 g), and P2O5 were mixed at 80 °C for 4.5 h. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was washed with deionized water and then stirred at room temperature for 24 h. The mixture was then filtered and washed with deionized water and ethanol and dried. The resulting powder was poured into H2SO4 (120 mL) with KMnO4 (15 g) in a two-neck flask placed in an ice bath and constantly stirred until the contents were completely dissolved. Then, DI water (250 mL) was added into the mixture with stirring for two h while the mix temperature was 35 °C. Eventually, deionized water (250 mL) was added along with H2O2 (20 mL), and the reaction was finished via stirring for 30 min in an ice bath. The obtained mixture was washed, and then a brown powder was filtered and dried in a vacuum oven.

2.3 Preparation of GO@TiO2

GO nanosheet (0.03 g) in EtOH/CH3CN (125:45 mL) were dispersed for 15 min. Then tetraethylorthotitanate (TEOT) (1.5 mL) was added to the mixture dropwise under sonication and then stirred for 24 h at room temperature. After this time, the product was filtered and washed with water and ethanol and then dried at room temperature (Chen et al., 2010).

2.4 Synthesis of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3NH2

The prepared GO@TiO2 (0.3 g) was dispersed in toluene (20 mL) for 15 min, then 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane was added, and the resulting mixture was stirred under Ar atmosphere for 24 h at 100 °C. At the end of this time, the mixture was filtered and washed three times with absolute ethanol and dried at room temperature (Gholtash and Farahi, 2018).

2.5 Synthesis of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18]

GO@TiO2/(CH2)3NH2 (0.4 g) and tetrabutylammonium hexamolybdate ([n-Bu4N]2 [Mo6O19]) (0.4 g) with dry DMSO (20 mL) was stirred for 24 h at room temperature under Ar atmosphere, then refluxed for 24 h. Next, observing the discoloration, the reaction mixture was filtered and produced GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] (1) washed three times with ethanol and dried at room temperature.

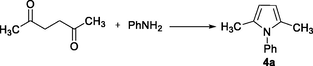

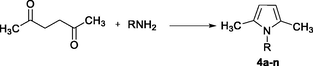

2.6 General procedure for the synthesis of pyrroles 4 by nanocatalyst 1

Nanocatalyst 1 (0.007 g) was added to a mixture of 2,5-hexadione (1 mmol) and amine (1 mmol) and stirred under solvent-free conditions at room temperature. After ensuring the completion of the reaction, boiling ethanol (5 mL) was added to the mixture, and the catalyst was separated by filtration. Finally, the pure product was obtained by recrystallization from n-hexane.

2.7 Catalyst recovery instructions

A mixture of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] (0.007 g), 2,5-hexadione (1 mmol), and aniline (1 mmol) was stirred under the free-solvent condition at 25 °C for 20 min. After completion of the reaction, boiling ethanol (5 mL) was added to the reaction, and the catalyst was separated. The catalyst was repeatedly washed with EtOH (10 mL) and deionized water (10 mL), followed by drying at 100 °C. Finally, it was reused in subsequent runs.

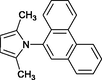

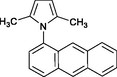

2.7.1 2,5-Dimethyl-1-(naphthyl)-pyrrole 4i

IR (KBr): vmax = 3060, 2980, 2915, 1594, 1410, 808, 779, 757 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 1.95 (s, 6H), 6.06 (s, 2H), 7.19 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.61 (2d, J 8, 7.6, 2H), 7.97 (d, J 8, 2H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 12.59, 105.44, 123.35, 125.42, 126.28, 126.56, 127.24, 128.08, 128.58, 129.90, 131.93, 134.23, 135.80 ppm.

2.7.2 1-(5-Chloro-2-hydroxyphenyl) 2,5-dimethyl-pyrrole 4q

IR (KBr): vmax = 3365, 2977, 2916, 1584, 1492, 1430, 1381, 1233, 1084, 820, 770, 729, 624 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.01 (s, 6H), 5.26 (m, 1H), 5.96 (s, 2H), 7.11 (s, 1H), 7.35 (s, 1H), 7.33 (s, 1H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 12.36, 106.68, 107.23, 117.42, 125.07, 126.05, 129.05, 130.13, 151.58 ppm.

2.7.3 7-(2,5-Dimethylpyrrol-1-yl)-4-methylcoumarin 4r

IR (KBr): vmax = 3066, 2916, 1749, 1616, 1510, 1401, 1166, 1078, 853, 751 cm−1. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 2.10 (s, 6H), 2.53 (s, 3H), 5.96 (s, 2H), 6.37 (s, 1H), 7.19–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.74 (d, J 8.4, 1H) ppm; 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ = 13.15, 18.77, 106.87, 115.29, 116.57, 119.22, 124.17, 125.20, 128.70, 142.05, 151.97, 153.78, 160.45 ppm.

3 Results and discussion

GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst (1) was synthesized as shown in Scheme 1. First, GO was prepared by the Hummer method. Using tetraethylorthotitanate (TEOT), a coating was placed on graphene oxide, and subsequently, POM was stabilized on the nanocatalyst as an active site with catalytic activity by aminopropyltriethoxysilane silane chain.![Preparation of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst 1.](/content/184/2022/15/5/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103736-fig1.png)

Preparation of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst 1.

As shown in Fig. 1, X-ray diffraction data of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] confirms that the crystal structure of the graphene oxide support remained unchanged during the catalyst preparation process. According to Fig. 1a, the peak at 2θ = 10.5 correspond to (0 0 1) represents GO powder. The repetition of this peak in Fig. 1b, c, and d emphasize the stability of the graphene oxide structure. In Fig. 1b, the peaks at 2θ = 24, 37.5, 48, 55.5, 58, and 62 related to (1 0 1), (0 0 4), (2 0 0), (1 0 5), (2 1 1) respectively, which proves the presence of anatase TiO2 on the surface of graphene oxide. In Fig. 1d, the confirming peak showing the presence of the molybdate group has appeared in the range of 2θ = 20–30°, which is covered by the broad peak of TiO2 (Abbasi et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022; Kou and Gao, 2011; Sun et al., 2022; Zarnegaryan et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2014). The interplanar spacing (d-spacing) of graphene oxide was also calculated using the Bragg equation and by XPert HighScore Plus software. According to Bragg's law:![XRD pattern of (a) GO and (b) GO@TiO2 (c) GO@TiO2/(CH2)3NH2 and (d) GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].](/content/184/2022/15/5/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103736-fig2.png)

XRD pattern of (a) GO and (b) GO@TiO2 (c) GO@TiO2/(CH2)3NH2 and (d) GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].

λ = 2dsin (θ)

wherein, λ is the wavelength of the X-ray beam (1.54 Aͦ nm), d is the distance between the layer, and θ is the diffraction angle. Based on these calculations, d was obtained about 1.2–8.8 Aͦ.

Fig. 2 shows the FT-IR spectrum of GO, GO@TiO2, GO@TiO2/(CH2)3NH2, and GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18]. In Fig. 2a, the presence of peaks in the 1052 cm−1, 1224 cm−1, 1755 cm-1and 3400 cm−1 are related to the stretching vibrations of C—O, C—OH, C⚌O, and COOH groups, respectively (Acik et al., 2010; Ayyaru and Ahn, 2017). The broad peaks between 500 and 900 cm−1 in Fig. 2b indicate Ti—O—Ti bonds (Martins et al., 2018). In Fig. 2c, absorption peaks at 2900–3000 cm−1 correspond to alkyl chains C—H vibrations. Furthermore, the presence of peaks at 790 cm−1 and 965 cm−1 in Fig. 2d are related to the stretching vibrations of Mo⚌O and Mo—O bonds which confirms the presence of [Mo6O18]−2 ions in the structure of the synthesized nanocatalyst (Kargar et al., 2020; Tanuraghaj and Farahi, 2019; Zarnegaryan et al., 2016).![FT-IR spectra of (a) GO, (b) GO@TiO2, (c) GO@TiO2/(CH2)3NH2, and (d) GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].](/content/184/2022/15/5/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103736-fig3.png)

FT-IR spectra of (a) GO, (b) GO@TiO2, (c) GO@TiO2/(CH2)3NH2, and (d) GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].

Energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) analysis proved that the GO and GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst was synthesized successfully. According to Fig. 3b, the EDS pattern indicated the existence expected of the elemental composition of C, O, Ti, N, and Mo in the nanocatalyst structure. The surface morphology and particle size distribution of the GO and prepared nanocatalyst were observed by the FE-SEM, and the corresponding image is shown in Fig. 3. Results show a uniform and regular spherical of particles with an average diameter range is 78–99 nm for GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst.![EDS analysis and FE-SEM images of (a) GO and (b). GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst.](/content/184/2022/15/5/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103736-fig4.png)

EDS analysis and FE-SEM images of (a) GO and (b). GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst.

To assess the morphologies of the GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst, the TEM image is provided in Fig. 4. The crumpled structure of graphene oxide with TiO2-coating and POM complex densely is evident in this image. The darker parts are related to the layers of graphene oxide support, and the more transparent parts confirm the presence of the TiO2 layer and the molybdate complex.![TEM images of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst.](/content/184/2022/15/5/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103736-fig5.png)

TEM images of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst.

Fig. 5 shows the representative Raman spectra of GO@TiO2@(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst. It could be seen that the high peak at 490 and 610 cm−1 correspond to the TiO2 nanoparticle (Zhao et al., 2014). Raman spectra of GO exhibit two characteristic bands that fit the disorder-induced D band and G band associated with the vibrations of sp2 bonded carbon networks (Claramunt et al., 2015). The nanocatalyst illustrates peaks at 1580 and 1361 cm−1, which are generally attributed to the G band and D band, respectively. Thus, it is evident from the Raman spectroscopy that the TiO2 nanoparticles and graphene oxide are present in the synthesized nanocatalyst.![Raman spectrum of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].](/content/184/2022/15/5/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103736-fig6.png)

Raman spectrum of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].

The thermal behavior of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] was investigated in a thermal range of 25–900 °C by thermogravimetric analysis under the air atmosphere (Fig. 6). According to the TGA curve, the first weight loss (about 2%) occurred at 80–110 °C, that related to the loss of water and ethanol solvent. The second weight loss (about 2%) at 140–230 °C indicates the removal of organic parts of the catalyst. The significant weight loss at 280–350 °C is probably due to the decomposition of the catalyst support (GO@TiO2), which has been degraded due to its modification by TiO2.![TGA curve of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].](/content/184/2022/15/5/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103736-fig7.png)

TGA curve of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].

The nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherm of the final catalyst is depicted in Fig. 7. The shape of the isotherm, according to IUPAC classification, revealed type IV isotherm with an H3-type hysteresis loop, indicating mesoporous material with layer structure. The specific surface area of GO before modification was 387.66 m2g−1, and the average pore diameter was 25.36 nm. This area was decreased to 12.94 m2g−1 after modification of the surface and stabilization of the metal complex and synthesis of GO@TiO2@(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst, which is quite normal due to the closing of the pores by metal. This can be considered as another proof for the immobilization of the hexamolybdate anions ([n-Bu4N]2 [Mo6O19]) on the surface of GO nanosheets.![Nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherm of (a) GO (b) GO@TiO2@(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].](/content/184/2022/15/5/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103736-fig8.png)

Nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherm of (a) GO (b) GO@TiO2@(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].

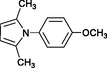

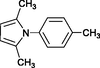

After characterization, to investigate the catalytic activity and efficiency of the newly designed catalyst, it was applied as a catalyst to synthesize pyrrole derivatives by Paal-knorr reaction (Scheme 2).![Synthesis of pyrrole derivatives in the presence of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] as the catalyst.](/content/184/2022/15/5/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103736-fig9.png)

Synthesis of pyrrole derivatives in the presence of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] as the catalyst.

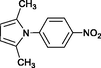

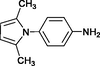

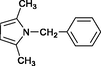

To find the optimal reaction conditions, the reaction between 2,5-hexadione, and aniline was selected as a model reaction. The effect of different parameters, such as temperature, catalyst loading, and the solvent, was evaluated. The reaction did not progress well in the absence of the catalyst. The model reaction was performed in the presence of 0.002, 0.004, 0.007, and 0.010 g of catalyst 1 at 25 °C. Next, the effect of the temperature was studied. The study showed the reaction to be affected by temperature. We found that higher temperature has not good impact on the reaction progress, and the best result was observed at 25 °C. Furthermore, the model reaction was performed by 0.007 g of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] in some solvents such as methanol, ethanol, acetonitrile, and toluene. As can be seen, considerable acceleration is observed chiefly in reactions performed at solvent-free conditions. According to these results, the use of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] (0.007 g) as catalyst under solvent-free conditions at 25 °C would be the best of choice (Table 1). To investigate the effect of electron-withdrawing and electron-donating groups on catalyst performance, different amines were used under optimal reaction conditions, and the results are shown in Table 2. aIsolated yields.

Entry

Catalyst loading (g)

Solvent

Temp. (°C)

Yieldb (%)

1

–

–

25

20

2

0.002

–

25

50

3

0.004

–

25

65

4

0.007

–

25

90

5

0.010

–

25

80

6

0.007

–

60

60

7

0.007

–

80

53

8

0.007

MeOH

25

60

9

0.007

EtOH

25

65

10

0.007

CH3CN

25

58

11

0.007

Toluene

25

50

Entry

Amine

Time (min)

Yielda (%)

M.p./°C

References

4a

20

96

50–51

Wang et al. (2004)

4b

15

81

58–60

Wang et al. (2004)

4c

15

91

45–47

Karami et al. (2013a)

4d

30

90

145–147

Karami et al. (2013a)

4e

25

87

72–74

Fattahi et al. (2021)

4f

20

92

78–79

Karami et al. (2013a)

4g

20

90

196–198

Karami et al. (2013a)

4h

35

80

–

Wang et al. (2004)

4i

20

83

120–122

Karami et al. (2013a)

4j

40

75

–

Wang et al. (2004)

4k

30

80

40–42

Wang et al. (2004)

4l

20

85

–

Banik et al. (2005)

4m

30

75

155–157

Banik et al. (2005)

4n

32

83

180–182

Banik et al. (2005)

4o

15

90

106–108

Karami et al. (2013a)

4p

30

70

265–267

Karami et al. (2013a)

4q

35

87

143–144

Karami et al. (2013b)

4r

45

72

138–139

Karami et al. (2013b)

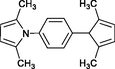

According to the reported mechanisms in the literature (Aghapoor et al., 2012; Chen et al., 2006; Khaghaninejad and Heravi, 2014; Marvi and Nahzomi, 2018), the proposed mechanism for Paal-Knorr reaction in the presence of nanocatalyst 1 is shown in Scheme 3. According to this mechanism, initially, the POM group stabilized on the catalyst support as an acidic catalytic site activates the carbonyl group of the diketone compound. The activated carbonyl group is attacked by amine to form hemiaminal 5. By the attack of amine to the second carbonyl group, intermediate 7, which is a 2,5-dihydroxytetrahydropyrrole derivative, is produced, which reaches the desired product by removing water.

Reasonable mechanism for Paal-Knorr reaction using nanocatalyst 1.

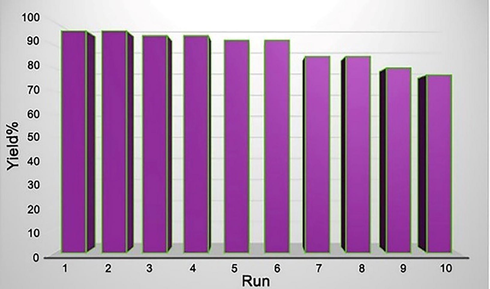

To investigate any leaching of [Mo6O19]2− from GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18], we have performed an in situ filtration technique. When the model reaction progress reached 50% warm EtOH (5 mL) was added, and the catalyst isolation was carried out by simple filtration. After removing the solvent, the catalyst-free residue continued the process under the conditions which before were optimized. As we expected, the progress of the reaction stopped, which confirms that no leaching of the supported catalytic centers has happened under optimized conditions. Also, the reusability of GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] was also investigated in the model reaction. After completion of the reaction, EtOH (5 mL) was added to the mixture, and the catalyst was filtered, washed with EtOH (10 mL), and deionized water (10 mL), followed by drying at 100 °C. Applying the recovered catalyst for ten successive runs in the model reaction generated the product, having some reduction in yield (Fig. 8). These experiments indicate the high stability and durability of this nanocatalyst under the applied conditions.

Reusability of catalyst 1 in the reaction between 2,5-hexadione and aniline.

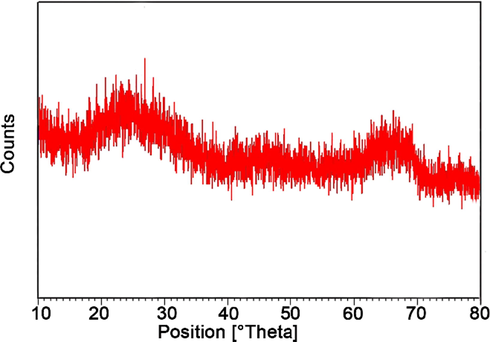

Fig. 9 shows the XRD pattern of recycled GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] nanocatalyst. The presence of index peaks in this spectrum and the complete similarity to the spectrum of the fresh nanocatalyst shows that its structure of it has remained almost unchanged after ten reuses. Also, in Fig. 10, the FT-IR spectrum of the nanocatalyst after ten reuses can be seen. This spectrum also confirms the stability of the structure of the recycled nanocatalyst.

XRD pattern of reused nanocatalyst.

![FT-IR spectrum of recycled GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].](/content/184/2022/15/5/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2022.103736-fig13.png)

FT-IR spectrum of recycled GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18].

In the next step, our study was concentrated on the comparison of the procedure mentioned above with the obtained results using precursors of the catalyst on the synthesis of pyrrole 4a as the model reaction. Table 3 shows that precursors of the catalyst have more prolonged time reactions and lower yields. The major advantages of the presented protocol over existing methods can be seen by comparing our results with those of some recently reported procedures in articles, as shown in Table 4.

Entry

Catalyst

Conditions

Time (min)

Yield (%)

1

GO (0.007 g)

solvent-free, r.t.

60

60

2

[n-Bu4N]2[Mo6O19] (0.007 g)

solvent-free, r.t.

60

50

3

TiO2 (0.007 g)

solvent-free, r.t.

60

45

4

GO@TiO2 (0.007 g)

solvent-free, r.t.

60

62

5

GO@(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] (0.007 g)

solvent-free, r.t.

60

73

6

GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] (0.007 g)

solvent-free, r.t.

20

96

Catalyst

Conditions

Time (min)

Yielda (%)

References

BiCl3/SiO2 (7.5 mol%)

solvent-free, r.t.

60

93

Aghapoor et al. (2012)

UO2(NO3)2·6H2O (10 mol%)

MeOH, r.t./)))

30

94

Satyanarayana and Sivakumar (2011)

In(OTf)3 (5 mol%)

solvent-free, r.t.

60

91

Chen et al. (2008)

Cu(OAc)2 (5 mol%)

solvent-free, r.t.

180

52

Chen et al. (2008)

[BMIm]I (1.5 g)

r.t.

180

96

Wang et al. (2004)

GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] (0.007 g)

solvent-free, r.t.

20

96

–

4 Conclusions

The development of catalytic processes and the advancement of innovative designs in the production of heterogeneous catalysts in recent years have led to an increase in the fabrication of pure products and the elimination of polluting products. Using recyclable and reusable catalysts prompted us to work on an environmentally friendly catalyst in this study. Thus, for the first time, we have introduced GO@TiO2/(CH2)3N = Mo[Mo5O18] as a green and recyclable GO-based nanocatalyst. The efficiency of this catalyst was evaluated in the synthesis of pyrrole derivatives. This new catalytic system demonstrated the advantages of environmentally benign character, easy separation, mild reaction conditions, short reaction times as well as good reusability. The results of using this nanocatalyst in the Paal–Knorr reaction were auspicious and gave us hope to use it in the preparation of other organic compounds and other coupling reactions in future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors would acknowledge the Yasouj University Research Council for trifle support of this research.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Application of the statistical analysis methodology for photodegradation of methyl orange using a new nanocomposite containing modified TiO2 semiconductor with SnO2. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.. 2021;101:208-224.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The role of intercalated water in multilayered graphene oxide. ACS Nano. 2010;4:5861-5868.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Silica-supported bismuth (III) chloride as a new recyclable heterogeneous catalyst for the Paal-Knorr pyrrole synthesis. J. Organomet. Chem.. 2012;708:25-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Photodegradation of graphene oxide sheets by TiO2 nanoparticles after a photocatalytic reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114:12955-12959.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Versatility of Weinreb amides in the Knorr pyrrole synthesis. Tetrahedron. 1999;55:6555-6566.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ordered mesoporous carbons as catalyst support for PEM fuel cells. Fuel Cells. 2009;9:197-200.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Superhydrophilic graphene-loaded TiO2 thin film for self-cleaning applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interf.. 2013;5:207-212.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Application of sulfonic acid group functionalized graphene oxide to improve hydrophilicity, permeability, and antifouling of PVDF nanocomposite ultrafiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci.. 2017;525:210-219.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced antifouling performance of PVDF ultrafiltration membrane by blending zinc oxide with support of graphene oxide nanoparticle. Chemosphere. 2020;241:125068.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasonic-promoted one-pot synthesis of 4H-chromenes, pyrano[2,3-d]pyrimidines, and 4H-pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazoles. Lett. Org. Chem.. 2012;9:435-439.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and biological properties of sequence-specific DNA-alkylating pyrrole-imidazole polyamides. Acc. Chem. Res.. 2006;39:935-944.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A straightforward highly efficient Paal-Knorr synthesis of pyrroles. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2005;46:2643-2645.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bacterial cellulose–silica organic–inorganic hybrids. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol.. 2008;46(3):363-367.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Improving solid-supported catalyst productivity by using simplified packed-bed microreactors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2007;46:1698-1701.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A class of pyrrole derivatives endowed with analgesic/anti-inflammatory activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 2013;21:3695-3701.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and biological activity of pyrrole, pyrroline and pyrrolidine derivatives with two aryl groups on adjacent positions. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:7213-7256.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A practical synthesis of a potent δ-opioid antagonist: Use of a modified knorr pyrrole synthesis. Org. Process. Res. Dev.. 2004;8:279-282.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A novel one-pot pyrrole synthesis via a coupling-isomerization-Stetter-Paal-Knorr sequence. Org. Lett.. 2001;3:3297-3300.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and performance of platinum supported on ordered mesoporous carbons as catalyst for PEM fuel cells: effect of the surface chemistry of the support. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2011;36:9805-9814.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial properties of pyrrole derivatives. J. Med. Chem.. 1967;10:29-32.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Palladium nanoparticles supported on amine-functionalized SiO2 for the catalytic hexavalent chromium reduction. Appl. Catal. B Environ.. 2016;180:53-64.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of visible-light responsive graphene oxide/TiO2 composites with p/n heterojunction. ACS Nano. 2010;4:6425-6432.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An approach to the Paal-Knorr pyrroles synthesis catalyzed by Sc(OTf)3 under solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2006;47:5383-5387.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Indium (III)-catalyzed synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles under solvent-free conditions. J. Braz. Chem. Soc.. 2008;19:877-883.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- FeCo/FeCoP encapsulated in N, Mn-codoped three-dimensional fluffy porous carbon nanostructures as highly efficient bifunctional electrocatalyst with multi-components synergistic catalysis for ultra-stable rechargeable Zn-air batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2022;605:451-462.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tuning of nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes as catalyst support for liquid-phase reaction. Appl. Catal. A. 2010;380:72-80.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The importance of interbands on the interpretation of the Raman spectrum of graphene oxide. J. Physic. Chem. C. 2015;119:10123-10129.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Homogeneous catalysis–new approaches to catalyst separation, recovery, and recycling. Science. 2003;299:1702-1706.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The influence of alumina phases on the performance of Pd/Al2O3 catalyst in selective hydrogenation of benzonitrile to benzylamine. Appl. Catal. A Gen.. 2017;545:97-103.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Are heterogeneous catalysts precursors to homogeneous catalysts? J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2001;123:10139-10140.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sphere-like and flake-like ZnO immobilized on pineapple leaf fibers as easy-to-recover photocatalyst for the degradation of congo red. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2021;9:104746.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Graphene oxide: a convenient carbocatalyst for facilitating oxidation and hydration reactions. Angew. Chem.. 2010;122:6965-6968.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon nanotubes as catalyst support in chemical vapor deposition reaction: a review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.. 2018;65:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tungstic acid-functionalized Fe3O4@TiO2: preparation, characterization and its application for the synthesis of pyrano[2,3-c]pyrazole derivatives as a reusable magnetic nanocatalyst. RSC Adv.. 2018;8:40962-40967.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molybdic acid-functionalized nano-Fe3O4@TiO2 as a novel and magnetically separable catalyst for the synthesis of coumarin-containing sulfonamide derivatives. Acta. Chim. Slov.. 2020;67:866-875.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanocomposites of TiO2 and reduced graphene oxide as efficient photocatalysts for hydrogen evolution. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2011;115:10694-10701.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Silica sodium carbonate as an effective and reusable catalyst for the three-component synthesis of pyrano coumarins. Org. Chem. Res.. 2018;4:182-193.

- [Google Scholar]

- A new protocol for one-pot synthesis of tetrasubstituted pyrroles using tungstate sulfuric acid as a reusable solid catalyst. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2016;57:1582-1584.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nano-Fe3O4@SiO2-supported boron sulfonic acid as a novel magnetically heterogeneous catalyst for the synthesis of pyrano coumarins. RSC Adv.. 2017;7:46644-46650.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Highly efficient syntheses of α-amino ketones and pentasubstituted pyrroles using reusable heterogeneous catalysts. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2015;56(14):1887-1890.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Design of sodium carbonate functionalized TiO2-coated Fe3O4 nanoparticles as a new heterogeneous catalyst for pyrrole synthesis. Bulg. Chem. Commun.. 2021;53:174-179.

- [Google Scholar]

- A study on the catalytic hydrogenation of N-ethylcarbazole on the mesoporous Pd/MoO3 catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2017;42:25942-25950.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In vitro scavenging activity for reactive oxygen and nitrogen species by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory indole, pyrrole, and oxazole derivative drugs. Free Radic. Biol. Med.. 2004;37:1895-1905.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon materials as catalysts for decomposition and CO2 reforming of methane: a review. Chin. J. Catal.. 2011;32:207-216.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Combustion synthesis of graphene oxide–TiO2 hybrid materials for photodegradation of methyl orange. Carbon. 2012;50:4093-4101.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A new and high yielding synthesis of unstable pyrroles via a modified Clauson-Kaas reaction. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2006;47:799-801.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrrole natural products with antitumor properties. Heterocycl. Antitum. Antibiot. 2006:53-92.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori, T., Tsubone, A., Sawama, Y., Monguchi, Y., Sajiki, H., 2015. Palladium on carbon-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction using an efficient and continuous flow system. Catalysts 5, 18–25. <https://doi.org/ 10.3390/catal5010018>.

- The Fe(iii)-catalyzed decarboxylative cycloaddition of β-ketoacids and 2H-azirines for the synthesis of pyrrole derivatives. Org. Chem. Front. 2020;7:3686-3691.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal-free graphene-based catalyst—insight into the catalytic activity: a short review. Appl. Catal. A. 2015;492:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hummers, J.R., William, S., Offeman, R.E., 1958. Preparation of graphitic oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 1339–1339. <https://doi.org/10.1021/ja01539a017>.

- Heterogeneous catalysts—discovery and design. J. Matter. Chem.. 2009;19:1222-1235.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- TiO2 nanoparticles assembled on graphene oxide nanosheets with high photocatalytic activity for removal of pollutants. Carbon. 2011;49:2693-2701.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ordered mesoporous carbons with controlled particle sizes as catalyst supports for direct methanol fuel cell cathodes. Carbon. 2008;46:2034-2045.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Contribution of B, N-co-doped reduced graphene oxide as a catalyst support to the activity of iridium oxide for oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021;9:9066-9080.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tungstic acid-functionalized MCM-41 as a novel mesoporous solid acid catalyst for the one-pot synthesis of new pyrrolo[2,1-a]isoquinolines. New J. Chem.. 2018;42:12811-12816.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A novel one-pot method for highly regioselective synthesis of triazoloapyrimidinedicarboxylates using silica sodium carbonate. Synlett. 2015;26:1804-1807.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Modified Paal-Knorr synthesis of novel and known pyrroles using tungstate sulfuric acid as a recyclable catalyst. Lett. Org. Chem.. 2013;10:12-16.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Regiospecific strategies for the synthesis of novel dihydropyrimidinones and pyrimidopyridazines catalyzed by molybdate sulfuric acid. Tetrahedron Lett.. 2014;55(26):3581-3584.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Green and rapid strategy for synthesis of novel and known pyrroles by the use of molybdate sulfuric acid. J. Chin. Chem. Soc.. 2013;60(9):1103-1106.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Core–shell structured Fe3O4@SiO2-supported IL/[Mo6O19]: a novel and magnetically recoverable nanocatalyst for the preparation of biologically active dihydropyrimidinones. J. Phys. Chem. Solids. 2020;146:109601.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Functional finishing of cotton fabrics using graphene oxide nanosheets decorated with titanium dioxide nanoparticles. J. Text Inst.. 2016;107:1122-1134.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A novel Cu-assisted cycloisomerization of alkynyl imines: efficient synthesis of pyrroles and pyrrole-containing heterocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2001;123:2074-2075.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Paal-Knorr reaction in the synthesis of heterocyclic compounds. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem.. 2014;111:95-146.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Graphene oxide nanosheets as metal-free catalysts in the three-component reactions based on aryl glyoxals to generate novel pyranocoumarins. New J. Chem.. 2014;38:3586-3590.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Observing graphene grow: catalyst–graphene interactions during scalable graphene growth on polycrystalline copper. Nano Lett.. 2013;13:4769-4778.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Graphene oxide sheets at interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2010;132:8180-8186.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Making silica nanoparticle-covered graphene oxide nanohybrids as general building blocks for large-area superhydrophilic coatings. Nanoscale. 2011;3:519-528.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Solvent free synthesis of chalcones over graphene oxide-supported MnO2 catalysts synthesized via combustion route. Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2021;259:124019.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Graphene as catalyst support: the influences of carbon additives and catalyst preparation methods on the performance of PEM fuel cells. Carbon. 2013;58:139-150.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- TiO2/graphene and TiO2/graphene oxide nanocomposites for photocatalytic applications: a computer modeling and experimental study. Compo. B Eng.. 2018;145:39-46.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grinding solvent-free Paal-Knorr pyrrole synthesis on smectites as recyclable and green catalysts. Bull. Chem. Soc. Ethiop. 2018;32:139-147.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Conducting carbon/polymer composites as a catalyst support for proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Energy Res.. 2014;38:1278-1287.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Clauson-Kaas pyrrole synthesis under microwave irradiation. Arkivoc. 2009;14:181-190.

- [Google Scholar]

- p-Aminophenol synthesis in an organic/aqueous system using Pt supported on mesoporous carbons. Appl. Catal. A. 2008;337:97-104.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A density functional theory study of the mechanism of the Paal-Knorr pyrrole synthesis. J. Mol. Struct.. 2007;811:97-107.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Transition metal-catalyzed and metal-free cyclization reactions of alkynes with nitrogen-containing substrates: synthesis of pyrrole derivatives. ChemCatChem. 2020;12:3335-3408.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Neysi, M., Zarnegaryan, A., Elhamifar, D., 2019. Core–shell structured magnetic silica supported propylamine/molybdate complexes: an efficient and magnetically recoverable nanocatalyst. New J. Chem. 43, 12283–12291. <https://doi.org/10.1039/C9NJ01160A>.

- Preparation, characterization and catalytic application of nano-Fe3O4@SiO2@(CH2)3OCO2Na as a novel basic magnetic nanocatalyst for the synthesis of new pyranocoumarin derivatives. RSC Adv.. 2018;8:27818-27824.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Molybdic acid immobilized on mesoporous MCM-41 coated on nano-Fe3O4: preparation, characterization, and its application for the synthesis of polysubstituted coumarins. Monatsh. Chem.. 2019;150:1841-1847.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A novel protocol for the synthesis of pyrano[2,3-h]coumarins in the presence of Fe3O4@SiO2@(CH2)3OCO2 Na as a magnetically heterogeneous catalyst. New J. Chem.. 2019;43:4823-4829.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Graphene oxide sheets chemically cross-linked by polyallylamine. Phys. Chem. C. 2009;113:15801-15804.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Graphene oxide as catalyst: application of carbon materials beyond nanotechnology. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2011;50:46-48.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of new bromine-rich pyrrole derivatives related to monodeoxypyoluteorin. Eur. J. Med. Chem.. 2006;41:1439-1445.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oxide-driven carbon nanotube growth in supported catalyst CVD. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2007;129:15772-15773.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Reshaping the cathodic catalyst layer for anion exchange membrane fuel cells: from heterogeneous catalysis to homogeneous catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2021;60:4049-4054.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Applications of hybrid organic–inorganic nanocomposites. J. Mater. Chem.. 2005;15:3559-3592.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of 2,5-dimethyl-N-substituted pyrroles catalyzed by uranyl nitrate hexahydrate. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry. 2011;18:917-922.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Encaging palladium(0) in layered double hydroxide: a sustainable catalyst for solvent-free and ligand-free Heck reaction in a ball mill. Beilstein J. Org. Chem.. 2017;13:1661-1668.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- From molecular double-ladders to an unprecedented polycatenation: a parallel catenated 3D network containing bicapped keggin polyoxometalate clusters. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem.. 2006;3:385-388.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- One-pot three-component tandem annulation of 4-hydroxycoumarine with aldehyde and aromatic amines using graphene oxide as an efficient catalyst. Sci. Rep.. 2021;11:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Probing the catalytic activity of porous graphene oxide and the origin of this behaviour. Nature Commun.. 2012;3:1-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbocatalysts: graphene oxide and its derivatives. Acc Chem. Res.. 2013;46:2275-2285.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Functionalised heterogeneous catalysts for sustainable biomass valorisation. Chem. Soc. Rev.. 2018;47:8349-8402.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In situ produced Co9S8 nanoclusters/Co/Mn-S, N multi-doped 3D porous carbon derived from eriochrome black T as an effective bifunctional oxygen electrocatalyst for rechargeable Zn-air batteries. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2022;608:2100-2110.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Single-site heterogeneous catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2005;44:6456-6482.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hantzsch pyrrole synthesis on solid support. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett.. 1998;8:2381-2384.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pyrrole synthesis in ionic liquids by Paal-Knorr condensation under mild conditions. Tetrahedron let.. 2004;45:3417-3419.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- l-(+)-Tartaric acid and choline chloride based deep eutectic solvent: An efficient and reusable medium for synthesis of N-substituted pyrroles via Clauson-Kaas reaction. J. Mol. Liq.. 2014;198:259-262.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of further improvement of platinum catalyst durability with highly graphitized carbon nanotubes support. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008;112(15):5784-5789.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ethylenediamine-functionalized magnetic Fe3O4@SiO2 nanoparticles: cooperative trifunctional catalysis for selective synthesis of nitroalkenes. RSC Adv.. 2015;5:73684-73691.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Direct catalytic oxidation of benzene to phenol over metal-free graphene-based catalyst. Energy Environ. Sci.. 2013;6:793-798.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Porous carbon-supported catalysts for energy and environmental applications: a short review. Catal. Today. 2011;178:197-205.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal-free catalysts of graphitic carbon nitride–covalent organic frameworks for efficient pollutant destruction in water. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2019;554:376-387.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A graphene oxide immobilized Cu(II) complex of 1,2-bis (4-aminophenylthio)ethane: an efficient catalyst for epoxidation of olefins with tert-butyl hydroperoxide. New J. Chem.. 2016;40:2280-2286.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and characterization of a novel polyoxometalate–Cu(II) hybrid catalyst for efficient synthesis of triazols. Polyhedron. 2016;115:61-66.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Supported molybdenum on graphene oxide/Fe3O4: an efficient, magnetically separable catalyst for one-pot construction of spiro-oxindole dihydropyridines in deep eutectic solvent under microwave irradiation. Catal. Commun.. 2017;88:39-44.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and photocatalytic performance of magnetic TiO2/montmorillonite/Fe3O4 nanocomposites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2014;53:8057-8061.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pd nanoparticles on a microporous covalent triazine polymer for H2 production via formic acid decomposition. Mater. Lett.. 2018;215:211-213.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Design, synthesis, and antifungal evaluation of novel coumarin-pyrrole hybrids. J. Heterocycl. Chem.. 2021;58:450-458.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Graphene oxide coated core–shell structured polystyrene microspheres and their electrorheological characteristics under applied electric field. J. Mater. Chem.. 2011;21:6916-6921.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Efficient preparation of large-area graphene oxide sheets for transparent conductive films. ACS Nano. 2010;4:245-5252.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Catalytic epoxidation of olefins with graphene oxide supported copper (Salen) complex. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2014;53:4232-4238.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Graphene oxide-supported cobalt tungstate as catalyst precursor for selective growth of single-walled carbon nanotubes. Inorg. Chem. Front.. 2021;8:940-946.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biomass valorisation over polyoxometalate-based catalysts. Green Chem.. 2021;23:18-36.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103736.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1