Translate this page into:

Measurement and modeling of metoclopramide hydrochloride (anti-emetic drug) solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide

⁎Corresponding author at: Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Kashan, Postal Code: 87317-53153 Kashan, Iran. sodeifian@kashanu.ac.ir (Gholamhossein Sodeifian)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

Knowledge of drug solubility data in supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) is a fundamental step in producing nano and microparticles through supercritical fluid technology. In this work, for the first time, the solubility of metoclopramide hydrochloride (MCP) in SC-CO2 was measured in pressure and temperature range of 12 to 27 MPa and 308 to 338 K, respectively. The results represented a range mole fractions of 0.15 × 10-5 to 5.56 × 10-5. To expand the application of the obtained data, six semi-empirical models and three models based on the Peng-Robinson equation of state (PR + VDW, PR + WS + Wilson and PR + MHV1 + COSMOSAC) with different mixing rules and various ways to describe intermolecular interactions were investigated. Furthermore, total enthalpy, sublimation enthalpy and solvation enthalpy relevant to MCP solvating in SC-CO2 were estimated.

Keywords

Metoclopramide hydrochloride

Supercritical carbon dioxide

Solubility

Sodeifian model

Peng-Robinson equation of state

1 Introduction

Metoclopramide hydrochloride (MCP), a receptor antagonist, is applied in the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders. Since antitumoral drugs usually cause nausea and vomiting as side effects, the main application of MCP is as an anti-emetic agent during cancer chemotherapy. It is also used in gastric stasis, gastroesophageal reflux and migraine headaches (Mohamed et al., 2013). There is a strong tendency in modern pharmaceutics to modify active pharmaceutical ingredients and make new formulations to increase therapeutic effects and reduce side effects. MCP has a short biological half-life so it is administered four times daily to maintain effective concentrations throughout the day. Also, this drug belongs to BCS III which has high solubility and low permeability. Hence, several researchers applied different techniques like solid dispersion, insertion of cosolvents, complexation with polymers or lipids and size reduction to to overcome these problems (Mohamed et al., 2013; Stosik et al., 2008).

The great attention has been draw to supercritical fluid (SCF) technology for micro and nanoparticle production (Sodeifian et al., 2022; Razmimanesh et al., 2021; Sodeifian et al., 2019; Sodeifian and Sajadian, 2019; Sodeifian et al., 2018; Sodeifian and Sajadian, 2018; Saadati Ardestani et al., 2020). In addition to the production of fine particles, another application of SCF is the extraction and purification of materials. Targeting components dissolving in the supercritical phase is a necessary step in the aforementioned processes. Lower viscosity, higher diffusivity, liquid-like density, better solvating power, and higher mass transferability are unique properties of SCF that can replace it with many organic solvents and ordinary processes (Sodeifian et al., 2017; Sodeifian et al., 2018; Sodeifian and Sajadian, 2017; Sodeifian et al., 2016). The application of CO2 as an SCF is common and favorable. In addition to its moderate critical pressure and temperature (7.38 MPa and 304 K), other properties such as non-explosiveness, non-flammability, non-polluting nature and high purity with low price have made it quite desirable and suitable (Sodeifian et al., 2019; Sodeifian et al., 2021).

The selection and design of an effective SCF process to reduce the particle size of a substance requires its solubility data. This information is also useful in evaluating an SCF extraction. Although experimental measurements may seem to be the most convincing way to obtain the required data, the high cost and time-consuming nature of this procedure, in addition to problems including toxic chemicals and/or excessive operation conditions, force us to use correlative models with few experimental data or to apply predictive thermodynamic models with relatively large uncertainty (Sodeifian et al., 2021). As a simple method, empirical and semi-empirical models can correlate the experimental solubility data according to the supercritical solvent density with or without co-solvents, operating temperature and pressure. A great advantage of using these models is that they do not require pure solid properties (Sodeifian et al., 2020; Tabernero et al., 2014).

On the other hand, applying cubic equations of state (EoS) like Peng − Robison (PR) is another way to model a supercritical equilibrium mixture. Some researchers have suggested that combining the cubic EoS with the classical mixing rule estimates the solubility in SC-CO2 more accurately for non-polar compounds while combining the cubic EoS with local composition-based activity coefficient models through a Gex-based mixing rule provides more appropriate results for polar substances (Jahromi and Roosta, 2019; Vidal, 1984). Although cubic EoSs, whilst having relatively simple mathematical formulas, are used to predict the properties of fluids and mixtures, their application requires the critical properties and sublimation pressures of solid substances for the solubility calculations. Sometimes, these properties are unavailable for new chemicals or those unstable at high temperatures. Furthermore, the sublimation pressure of many solids is so low that it is almost impossible to measure. Although these properties could be estimated in different ways, such as group contribution methods (Sodeifian et al., 2019; Sodeifian et al., 2018), such a missing exact (experimental) values of these properties may lead to excess errors in the employed models (Wang and Hsieh, 2022). An approach of utilizing quantum mechanical (QM) and COSMO solvation calculation results to determine the energy and volume parameters in PR EoS was proposed to overcome the issue of missing experimental critical properties and acentric factor (Hsieh and Lin, 2008; Hsieh and Lin, 2009; Liang et al., 2019) and has been applied to predict properties of pure components and fluid phase behaviors of mixtures (Hsieh and Lin, 2009; Hsieh and Lin, 2010; Hsieh and Lin, 2011).

To the best of our knowledge, there is no report of MCP solubility data in SC-CO2. Hence, this study aimed to experimentally quantify the solubility of this valuable drug in SC-CO2 at 308 K, 318 K, 328 K and 338 K in a pressure range of 12 – 27 MPa. Furthermore, the ability of six semi-empirical models and three approaches based on PR EoS in describing MCP solubility data in SC-CO2 was evaluated.

2 Experiment

2.1 Materials

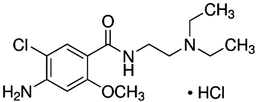

Metoclopramide hydrochloride, MCP, (CAS Number 7232–21-5) was provided by Aminpharma Company (Isfahan, Iran) with a minimum purity of 99.0%. The molecular structure and thermodynamic properties of MCP are summarized in Table 1. The carbon dioxide (CAS Number 124–38-9) with a purity of 99.99% was supplied by Fadak Company (Kashan, Iran). Methanol (CAS Number 67–56-1) was produced by Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) with a purity exceeding 99.9%.

Compound

metoclopramide hydrochloride

Structure

Formula

C14H22ClN3O2•HCl

CAS number

7232–21-5

λmax (nm)

270

Minimum purity

99%

MW (g∙mol−1)

336.26

Tm (K)

455.30 (Pabón et al., 1996)

ΔHm (kJ∙mol−1)

25.72 (Pabón et al., 1996)

Tc (K)a

1321.25

Pc (MPa) a

2.3958

ω (-) a

0.3471

Vs (cm3∙mol−1) b

233.51

2.2 Experimental apparatus and procedure

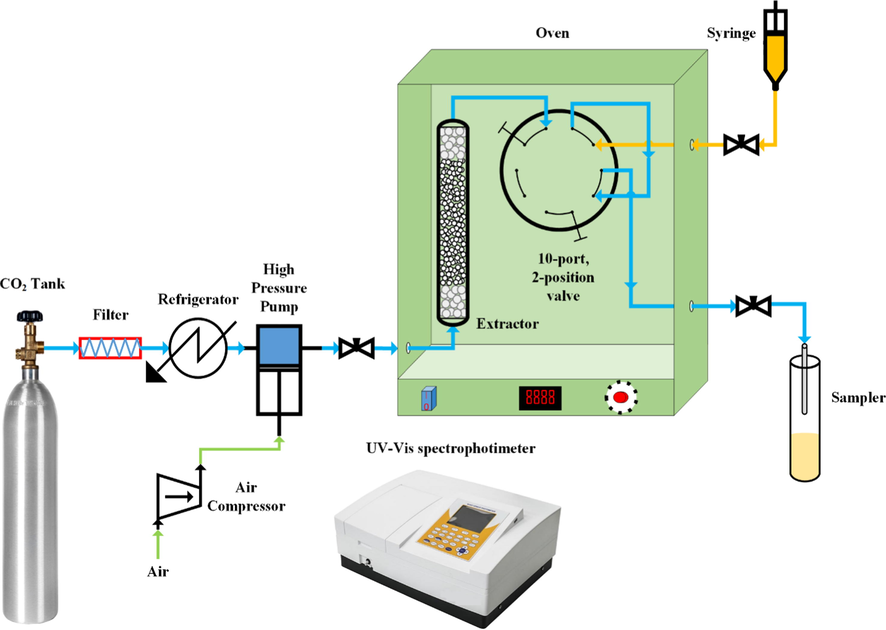

In this work, an experimental setup with the schematic shown in Fig. 1 along with a UV–vis spectrophotometer was employed to measure the drug solubility statically. Originated from a high-pressure storage cylinder (about 6 MPa), CO2 passed through a filter with a pore size of 1-μm and then was liquefied via cooling down from ambient temperature to about 253 K in a refrigeration unit. A reciprocating pump powered by an air compressor was used to pressurize CO2 to the desired value. The pressure was monitored and controlled by a pressure gauge (WIKA, Germany, Code EN 837–1) and a digital pressure transmitter (WIKA, Germany, Code IS-0–3-2111, pressure range 1–6000 psi) within ± 0.1 MPa of accuracy throughout the experiment. After passing through a preheater, carbon dioxide entered a 70-mL equilibrium cell where the temperature was carefully adjusted and controlled by an oven with an accuracy of ± 0.1 K. The equilibrium cell was preloaded with 500 mg of MCP along with 2-mm glass beads uniformly (for particle distribution and complete saturation). The undissolved drug was retained by putting two stainless-steel sintered filters on both ends of the equilibrium cell, and thus any solids carryover was prevented. The system (cell) was maintained at the desired experimental condition for 120 min to achieve the thermodynamic equilibrium (according to preliminary experiments). Then, the saturated SC-CO2 was transferred into a 600 μL ± 0.6% of volume collection loop through a six-port, two-position valve. Then this valve was turned over to evacuate the loop into an organic solvent (methanol) vial with a given volume. The depressurization (evacuation) process was controlled utilizing a micrometer valve to avoid solvent (methanol) dispersion. Eventually, the loop was rinsed with the collection vial solution followed by pure methanol, and the final sample volume was adjusted to 5 mL ± 0.6%.

Experimental setup for solubility measurement.

Utilizing a spectrophotometer (Cintra 101 UV–Vis), MCP solubility in different thermodynamic conditions was measured (λmax = 270 nm). A stock methanol solution of 100 μg∙mL−1 was prepared, using an appropriate mass of solid MCP. Subsequently, different standard solutions were fabricated by diluting the stock solution, and a calibration curve (regression coefficient = 0.989) was formulated for determining the MCP concentration in the collection vial. While MCP was denoted as 2 in the binary supercritical system, its solubility was quantitatively analyzed through UV absorption data. The equilibrium mole fraction in SC-CO2, y2, was computed as follows:

where

,

,

and

indicate moles of solute and CO2 in the sampling loop and molecular weights of the solute and CO2, respectively. Solute concentration (in unit of g∙L−1) in the collection vial, volumes (in unit of L) of the collection vial and sampling loop were denoted by

,

and

, respectively. The equilibrium solute solubility in SC-CO2 (in unit of g∙L−1) is then calculated from the following equations:

The collection vial and sampling loop (Vs and Vl) volumes were measured carefully by microliter pipette (transferpette® S). The accuracy of volumes was calculated by Eq. (6):

A = accuracy.

V0 = nominal value.

V = mean value.

These values for 600 µL and 5 mL were 2% and 0.6%, respectively.

To make sure the obtained absorption numbers by UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Cintra-101) are confident, absorption of number of samples were measured by other UV–Vis spectrophotometer like Unico, SQ-4802 and Shimadzu, model UV-3101 UV–Vis spectrophotometers. The obtained results indicate that uncertainty of UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Cintra) is less than 1%.

Due to the uncertainties values of different parameters (P, T and standard deviation of mole fraction), uncertainties of solubility data were calculated and presented in Table 2. *Standard uncertainty u are u(T) = 0.1 K and u(P) = 0.1 MPa. Also. relative standard uncertainties were obtained below 5% for solubilities in mole fraction. The value of the coverage factor k = 2 was chosen on the basis of the level of confidence of approximately 95 percent.

T

(K)

P

(MPa)

a

(kg∙m−3)

y × 105

(Mole fraction)Experimental standard deviation.b

Std(y) × 105

(Mole fraction)Expanded uncertainty.c U(y) × 105

(Mole fraction)Equilibrium solubility. S (g∙L−1)

308

12.0

769

0.4683

0.021

0.0455

0.0276

15.0

817

0.6728

0.012

0.0365

0.0420

18.0

849

0.8670

0.033

0.0715

0.0563

21.0

875

1.1911

0.041

0.0959

0.0797

24.0

896

2.4321

0.030

0.1232

0.1667

27.0

914

3.4444

0.082

0.2206

0.2406

318

12.0

661

0.3520

0.013

0.0259

0.0178

15.0

744

0.4526

0.011

0.0287

0.0257

18.0

791

0.4987

0.022

0.0458

0.0301

21.0

824

2.8905

0.041

0.1514

0.1821

24.0

851

4.0001

0.063

0.2138

0.2600

27.0

872

4.3114

0.093

0.2618

0.2875

328

12.0

509

0.2833

0.012

0.0240

0.0110

15.0

656

0.3520

0.011

0.0256

0.0177

18.0

725

0.4033

0.021

0.0439

0.0223

21.0

769

3.2970

0.061

0.1895

0.1939

24.0

802

4.3572

0.092

0.2638

0.2672

27.0

829

4.7873

0.021

0.2148

0.3032

338

12.0

388

0.1500

0.006

0.0139

0.0044

15.0

557

0.2657

0.011

0.0234

0.0113

18.0

652

0.3311

0.011

0.0249

0.0165

21.0

710

3.5429

0.021

0.1626

0.1923

24.0

751

4.5663

0.080

0.2577

0.2623

27.0

783

5.5609

0.102

0.3164

0.3329

The experimental standard deviation and the experimental standard deviation of the mean (SD) were obtained by .

and , respectively.

Expanded uncertainty and the relative combined standard uncertainty were defined (U) = k*ucombined and ucombined/y= , respectively.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Experimental data

It is worth mentioning that in our previous work (Sodeifian et al., 2017), the validity and reliability of the experimental apparatus and the applied procedure were approved by SC-CO2 solubility determination of naphthalene and alpha-tocopherol at several temperatures and pressures. Also, before solubility measurement, equipment was calibrated with the mentioned materials to validate the setup.

Experimental measurements were performed at least in triplicate for each data point. By computing the average, SC-CO2 solubility values of MCP were reported in Table 2. As the solubilities were low, the system density values presented in Table 2 were approximated by the density of pure carbon dioxide. The CO2 density was specified according to NIST chemistry database (

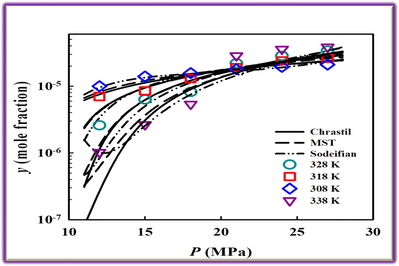

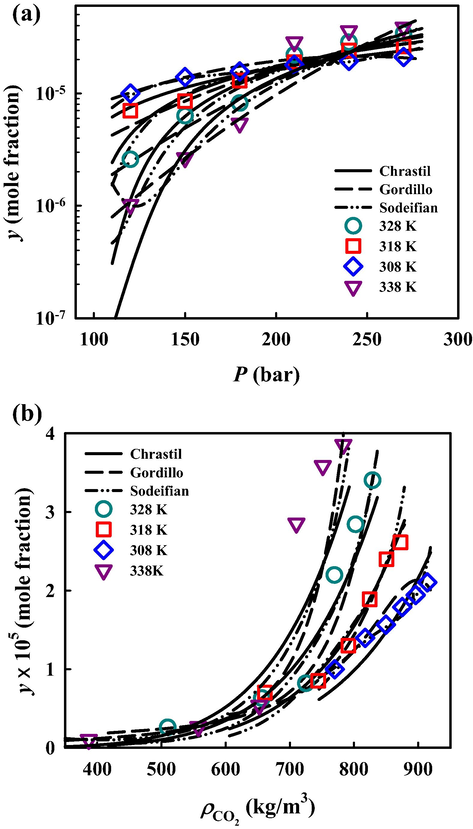

https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry) (National Institute of Standards, xxxx). The MCP solubility in terms of mole fraction (y) and g∙L−1 (S) ranges from 0.15 × 10-5 to 5.56 × 10-5 and 0.0044 to 0.3329, respectively. The magnitude of MCP solubility in SC-CO2 in mole fraction ranges from 10-6 to 10-5. The minimum and maximum values of MCP solubility in SC-CO2 among all experimental conditions were observed at 338 K under pressures of 12 MPa and 27 MPa, respectively. Fig. 2 depicts solubility isotherms and shows that pressure increment results in MCP solubility enhancement, indicating solvating power increasing. This phenomenon is due to higher SC-CO2 density, which is equivalent to the reduced mean distance of system molecules and improved solvent–solute interactions (Sodeifian et al., 2017; Iwai et al., 1991).

Solubility versus (a) pressure and (b) density from experiment and three semi-empirical models for solubility of metoclopramide hydrochloride in SC-CO2.

As shown in Fig. 2, isothermal lines intersect around 22 MPa, the cross-over point of the investigated system. Generally, the temperature has two antithetical effects on solid solute solubility in SC-CO2 due to its effect on SC-CO2 density and solute vapor pressure. The cross-over phenomenon indicates that the dominant effect of temperature on solubility changes from its effect via SC-CO2 density at the low-pressure region to solute vapor pressure at the high-pressure region. At lower pressures, the solubility diminishes on temperature increase due to density reduction. In contrast, the solubility increases with increasing temperature at higher pressures because of an excess elevation in solute vapor pressure. This behavior, i.e., the presence of a cross-over pressure, has been observed in many other SC-CO2 systems that could confirm the results of this work (Khimeche et al., 2007; Tamura et al., 2017; Pitchaiah et al., 2017; Kazemi et al., 2012; Sodeifian et al., 2017; Sodeifian et al., 2019; Sodeifian and Sajadian, 2019; Sodeifian et al., 2019).

3.2 Data correlation using semi-empirical models

The newly measured solubility data were correlated by six semi-empirical models, which were proposed by Chrastil (Chrastil, 1982), Méndez-Santiago and Teja (Méndez-Santiago and Teja, 1999), Kumar and Johnston (Kumar and Johnston, 1988), Bartle et al. (Bartle et al., 1991), Sodeifian et al. (Sodeifian et al., 2019) and Gordillo et al. (Gordillo et al., 1999). The expressions for these semi-empirical models, as well as their abbreviations, are summarized in Table 3. The values of adjustable parameters in these models were determined by minimizing the percentage average absolute relative deviation (AARD%) for solubility in mole fraction:

*a0 ∼ a5 are adjustable model parameters; ρ is SC-CO2 density in kg∙m−3; T is temperature in K; P is pressure in bar.

Model

Ref.

Equations

Chrastila

(Chrastil, 1982)

MSTb

(Méndez-Santiago and Teja, 1999)

K-Jb

(Kumar and Johnston, 1988)

Bartlec

(Bartle et al., 1991)

Sodeifianb

(Sodeifian et al., 2019)

Gordillob

(Gordillo et al., 1999)

where N is the number of data; the superscripts exp and cal indicate results from experiment and correlation models, respectively.

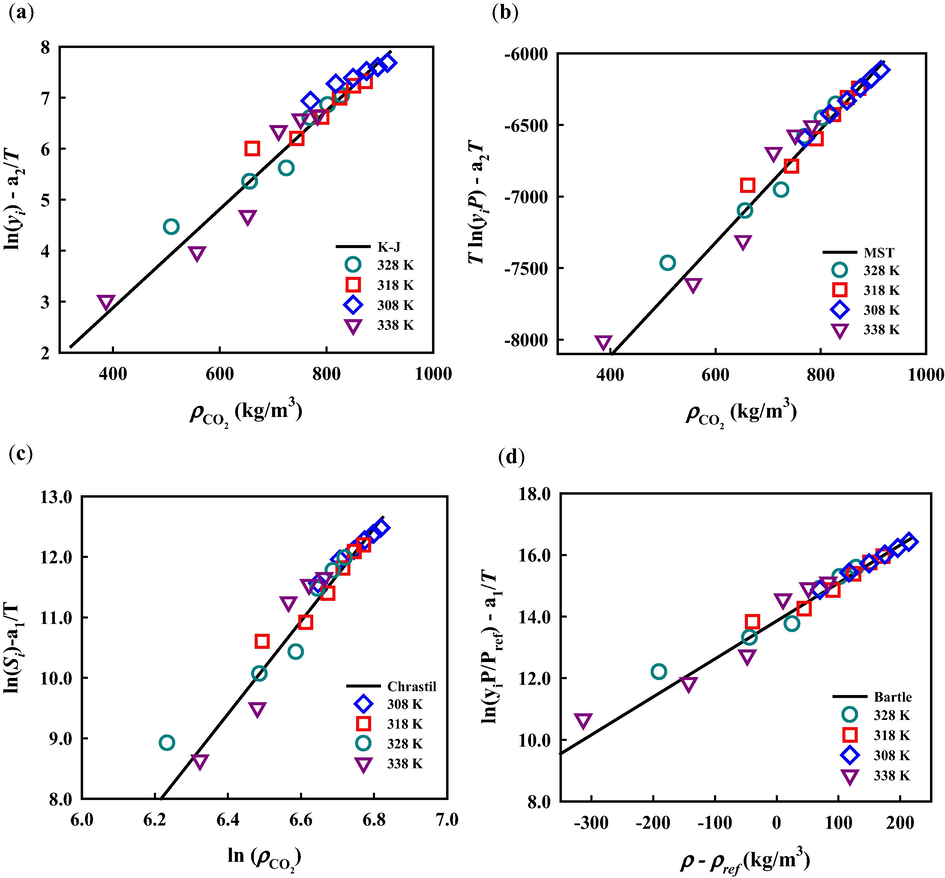

Table 4 summarizes the optimized parameter values for these six semi-empirical models, as well as their corresponding AARD%. The overall deviations for solubility data correlation are from 11.41% (Gordillo model) to 22.82% (Chrastil model). The Gordillo and Sodeifian models contain more terms, i.e., more adjustable parameters, than the other four models to consider possibly complex relations between solubility and independent variables of pressure, temperature and CO2 density, resulting in better representations of solubility. Fig. 2 illustrates the correlation results from three employed models: Chrastil, Sodeifian and Gordillo models. As can be seen, all these three models can approximately capture the tendency of solubility obtained from experiments. The correlation results from all six studied models are plotted separately in Figures S1 and S2 of the supplementary material. Gordillo and Sodeifian models contain more terms, i.e., more adjustable parameters, than the other four models to consider possibly complex relations between solubility and independent variables of pressure, temperature and CO2 density, resulting in better representations of solubility. In addition, the studied semi-empirical models, except for the Sodeifian and Gordillo models, could also be used to perform simple self-consistency tests for experimentally obtained solubility data to confirm their reliability. As shown in Fig. 3, the experimental solubility data are considered self-consistent since most of them were aligned to a single correlation line.

Model

Correlation parameters

AARD%

Chrastil

7.672

−4434.297

−39.696

22.82%

MST

−9695.491

3.956

14.682

22.25%

K-J

−9.876

10-1

9.667

10-3

−5683.709

22.02%

Bartle

13.857

1.232

10-2

−6651.853

21.03%

Sodeifian

110.278

2.632

10-2

−6.871

6.335

10-3

−9.738

10-3

−2952.469

17.33%

Gordillo

−5.981

10-3

−1.738

10-1

−4.792

10-5

6.403

10-4

5.325

10-2

−3.164

10-4

11.41%

Experimental data self-consistency test for solubility of metoclopramide hydrochloride in SC-CO2 using (a) K-J, (b) MST, (c) Chrastil and (d) Bartle models.

The total enthalpy for solid solute dissolution in SC-CO2 was proposed to be determined from the model parameter a1 of the Chrastil model (Chrastil, 1982): While the sublimation enthalpy of a solute molecule was estimated from the model parameter a2 of the Bartle model (Bartle et al., 1991): . If the process of a solute molecule dissolution in SC-CO2 consists of two steps: sublimation and solvation in SC-CO2; the solvation enthalpy ( ) can then be calculated from . The calculated total enthalpy, sublimation enthalpy, and solvation enthalpy for MCP are 36.87 kJ∙mol−1, 55.30 kJ∙mol−1 and −18.43 kJ∙mol−1, respectively.

3.3 Solubility from Peng-Robinson equation of state

The standard formula for solving the solubility in SC-CO2 of the studied solute i using a cubic EoS is the equifugacity condition for the solute in its pure solid phase (S) and supercritical fluid phase (SF) at a given temperature (T) and pressure (P) (Sandler, 2006):

Following the approach proposed by Kikic et al. (Kikic et al., 1997); fugacity of a solid solute i is obtained from its melting temperature (

) and fusion enthalpy (

):

where is atmospheric pressure and set to 101325 Pa in this study; and are the fugacity and molar volume in a hypothetical liquid state determined from the studied equation of state as well; is the solid molar volume and its value was retrieved from the molecular volume in COSMO solvation calculation (Ting and Hsieh, 2017; Chen et al., 2018; Cai et al., 2020; Cai and Hsieh, 2020; Wang et al., 2021).

The Peng-Robinson (PR) EoS (Peng and Robinson, 1976) was used to model the solubility of MCP in SC-CO2:

where a and b are energy and volume parameters of the investigated fluid. For pure fluid i, they are calculated from critical pressure (Pc,i), critical temperature (Tc,i) and acentric factor (ωc,i):

with

. In the case of a mixture, the composition has to be considered via a mixing rule, such as van der Waals (VDW) one-fluid mixing rule (Sandler, 2006):

where kij is the binary interaction parameter and × is the mole fraction. This approach is referred to as PR + VDW in the underlying context. In this study, the critical properties and acentric factor for MCP were estimated from PR + COSMOSAC EoS (Liang et al., 2019) and Lee-Kesler equation (Lee and Kesler, 1975), respectively, as described in previous works (Cai and Hsieh, 2020; Wang et al., 2021). The normal boiling temperature and critical temperature from PR + COSMOSAC EoS were rescaled with a factor of 0.91 in order to provide satisfactory correlation results, which was determined via regressing experimental solubility data together with kij. Their values are summarized in Table 1.

Two other approaches using

-based mixing rules with activity coefficient models to determine the energy and volume parameters were investigated in this study. One is the combination of the Wong-Sandler mixing rule (Wong and Sandler, 1992) and Wilson model (Wilson, 1964):

where

,

is the molar excess Gibbs energy and two binary interaction parameters

and

are adjustable parameters. This approach, denoted as PR + WS + Wilson, was taken into account to understand the capability of PR EoS in correlating the solubility data with two adjustable parameters. The other approach is to combine the MHV1 mixing rule (Michelsen, 1990) with COSMO-SAC model (Chen et al., 2016; Hsieh et al., 2010; Bell et al., 2020):

where and is determined from the COSMO-SAC model (Hsieh et al., 2010) without any adjustable species-specific binary interaction parameters. This approach, denoted as PR + MHV1 + COSMOSAC, was used to demonstrate the capability of PR EoS in predicting solubility with limited information. The quantum mechanical and COSMO solvation calculations were performed to generate molecular information for the COSMO-SAC model following the “b3lyp/6-31G(d.p)-cosmo” method in the literature (Chen et al., 2016).

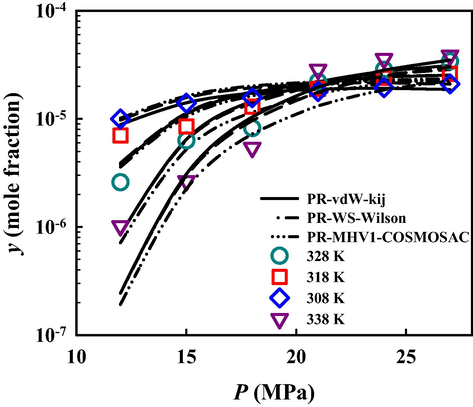

In the above approaches, the binary interaction parameters were obtained by minimizing the AARD% described in Eq. (7). Table 5 summarizes overall deviations in AARD% and the corresponding values of binary interaction parameters. The AARD% for MCP from two correlation approaches PR + VDW and PR + WS + Wilson are 24.0% and 26.2%, respectively, similar to those from the semi-empirical models. The advantage of using an EoS is that these optimal parameter values could be further applied to describe the phase behavior of multicomponent mixtures containing the studied solutes and CO2 (Li et al., 2004). The AARD% for MCP from the predictive approach PR + MHV1 + COSMOSAC is 28.9%, similar to those from the above correlation methods. This result demonstrates that the predictive models based on COSMO-SAC model can provide good solubility estimation with sufficient information for the investigated chemicals.

Model

k12

(−)Λ12

(J/mol)Λ21

(J/mol)AARD%

PR + VDW

8.81

10-2

–

–

24.0%

PR + WS + Wilson

–

2.08

104

1.07

103

26.2%

PR + MHV1 + COSMOSAC

–

–

–

28.9%

Fig. 4 compares the solubility of MCP in SC-CO2 from experimentation and the three studied thermodynamic models (the calculation results are plotted separately in Figure S3 of the supplementary material). In general, all three approaches provide satisfactory solubility results, but PR + MHV1 + COSMOSAC overestimates the isotherm cross-over pressure, which was experimentally determined around 22 MPa. It is worth mentioning that PR + MHV1 + COSMOSAC has been proved to provide reasonable predictions for binary vapor–liquid equilibria of CO2 and low molecular weight alcohols (Hsieh et al., 2013), indicating that this predictive approach has the potential to predict the solubility of MCP in CO2 + alcohol binary mixtures.

Solubility of metoclopramide hydrochloride in SC-CO2 from experimental measurement and three thermodynamic models based on PR EoS.

4 Conclusion

Determining the solubility of materials in a supercritical fluid is essential for the feasibility study of these processes and their optimization. In the present work, the solubility of metoclopramide hydrochloride (MCP), an anti-emetic drug during cancer chemotherapy, in SC-CO2 was measured at a pressure range of 12 to 27 MPa and temperatures of 308 to 338 K. The static method following by composition analysis via UV–Vis spectrophotometry determined the solubility in mole fraction within the range of 0.15 × 10-5 to 5.56 × 10-5. The capability of two classes of models in describing MCP solubility data was examined: semi-empirical models and thermodynamic models based on Peng-Robinson (PR) EoS (combining with different mixing rules and resulting in different numbers of adjustable binary interaction parameters). The semi-empirical model proposed by Gordillo et al. provides the most precise correlation results among the six studied semi-empirical models. On the other hand, thermodynamic modeling via integration of PR EoS and van der Waals (VDW) mixing rule produced the least error in solubility prediction. It is worth mentioning that all three studied approaches provide good solubility prediction.

Acknowledgement

We would like to take this opportunity to thank the Research Deputy to the University of Kashan for financially empowering this research under Grant number Pajoohaneh-1400/22. The authors also acknowledge the computational resources from the National Center for High-Performance Computing (NCHC) of Taiwan.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Formulation and evaluation of metoclopramide solid lipid nanoparticles for rectal suppository. J. Pharmacy Pharmacology. 2013;65:1607-1621.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biowaiver monographs for immediate release solid oral dosage forms: Metoclopramide hydrochloride. J. Pharm. Sci.. 2008;97:3700-3708.

- [Google Scholar]

- CO2 utilization as a supercritical solvent and supercritical antisolvent in production of sertraline hydrochloride nanoparticles. J. CO2 Utilization. 2022;55:101799

- [Google Scholar]

- An investigation into Sunitinib malate nanoparticle production by US- RESOLV method: Effect of type of polymer on dissolution rate and particle size distribution. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2021;170:105163

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of Loratadine drug nanoparticles using ultrasonic-assisted Rapid expansion of supercritical solution into aqueous solution (US-RESSAS) J. Supercritical Fluids. 2019;147:241-253.

- [Google Scholar]

- Utilization of ultrasonic-assisted RESOLV (US-RESOLV) with polymeric stabilizers for production of amiodarone hydrochloride nanoparticles: Optimization of the process parameters. Chem. Eng. Res. Des.. 2019;142:268-284.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of Aprepitant nanoparticles efficient drug for coping with the effects of cancer treatment) by rapid expansion of supercritical solution with solid cosolvent (RESS-SC) J. Supercritical Fluids. 2018;140:72-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solubility measurement and preparation of nanoparticles of an anticancer drug (Letrozole) using rapid expansion of supercritical solutions with solid cosolvent (RESS-SC) J. Supercritical Fluids. 2018;133:239-252.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preparation of phthalocyanine green nano pigment using supercritical CO2 gas antisolvent (GAS): experimental and modeling. Heliyon. 2020;6:e04947

- [Google Scholar]

- Supercritical fluid extraction of omega-3 from Dracocephalum kotschyi seed oil: Process optimization and oil properties. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2017;119:139-149.

- [Google Scholar]

- Properties of Portulaca oleracea seed oil via supercritical fluid extraction: Experimental and optimization. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2018;135:34-44.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of essential oil extraction and antioxidant activity of Echinophora platyloba DC. using supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2017;121:52-62.

- [Google Scholar]

- Extraction of oil from Pistacia khinjuk using supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental and modeling. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2016;110:265-274.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental study and thermodynamic modeling of Esomeprazole (proton-pump inhibitor drug for stomach acid reduction) solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2019;154:104606

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of Galantamine solubility (an anti-alzheimer drug) in supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2): Experimental correlation and thermodynamic modeling. J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;330:115695

- [Google Scholar]

- Solubility of Quetiapine hemifumarate (antipsychotic drug) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental, modeling and Hansen solubility parameter application. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 2021;537:113003

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental measurement and thermodynamic modeling of Lansoprazole solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide: Application of SAFT-VR EoS. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 2020;507:112422

- [Google Scholar]

- Modelling solubility of solid active principle ingredients in sc-CO2 with and without cosolvents: A comparative assessment of semiempirical models based on Chrastil's equation and its modifications. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2014;93:91-102.

- [Google Scholar]

- Estimation of critical point, vapor pressure and heat of sublimation of pharmaceuticals and their solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 2019;488:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phase Equilibria and Density Calculations for Mixtures in the Critical Range with Simple Equations of State (Invited Lecture) Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem.. 1984;88(9):784-791.

- [Google Scholar]

- Measurement, correlation and thermodynamic modeling of the solubility of Ketotifen fumarate (KTF) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Evaluation of PCP-SAFT equation of state. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 2018;458:102-114.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of solid solute solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide from PSRK EOS with only input of molecular structure. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2022;180:105446

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of cubic equation of state parameters for pure fluids from first principle solvation calculations. AIChE J.. 2008;54(8):2174-2181.

- [Google Scholar]

- First-Principles Predictions of Vapor−Liquid Equilibria for Pure and Mixture Fluids from the Combined Use of Cubic Equations of State and Solvation Calculations. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2009;48(6):3197-3205.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improvement to PR+COSMOSAC EOS for Predicting the Vapor Pressure of Nonelectrolyte Organic Solids and Liquids. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2019;58:5030-5040.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of 1-octanol–water partition coefficient and infinite dilution activity coefficient in water from the PR+COSMOSAC model. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 2009;285:8-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of liquid–liquid equilibrium from the Peng–Robinson+COSMOSAC equation of state. Chem. Eng. Sci.. 2010;65:1955-1963.

- [Google Scholar]

- First-principles prediction of vapor-liquid-liquid equilibrium from the PR+COSMOSAC equation of state. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2011;50:1496-1503.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determination of solubility of Aprepitant (an antiemetic drug for chemotherapy) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Empirical and thermodynamic models. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2017;128:102-111.

- [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology U.S. Department of Commerce, NIST Chemistry WebBook.

- Solubilities of myristic acid, palmitic acid, and cetyl alcohol in supercritical carbon dioxide at 35.degree.C. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 1991;36:430-432.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solubility of diamines in supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental determination and correlation. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2007;41:10-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solubility of 1-aminoanthraquinone and 1-nitroanthraquinone in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Chem. Thermodyn.. 2017;104:162-168.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solubility of dialkylalkyl phosphonates in supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental and modeling approach. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 2017;435:88-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solubilities of ferrocene and acetylferrocene in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2012;72:320-325.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solubility of an antiarrhythmic drug (amiodarone hydrochloride) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental and modeling. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 2017;450:149-159.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solubility measurement of a chemotherapeutic agent (Imatinib mesylate) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Assessment of new empirical model. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2019;146:89-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental measurement of solubilities of sertraline hydrochloride in supercriticalcarbon dioxide with/without menthol: Data correlation. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2019;149:79-87.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental measurements and thermodynamic modeling of Coumarin-7 solid solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide: Production of nanoparticles via RESS method. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 2019;483:122-143.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solubility of Solids and Liquids in Supercritical Gases. J. Phys. Chem.. 1982;86:3016-3021.

- [Google Scholar]

- J. Méndez-Santiago, A.S. Teja, The solubility of solids in supercritical fluids, Fluid Phase Equilibria 158-160 (1999) 501-510.

- Modelling the Solubility of Solids in Supercritical Fluids with Density as the Independent Variable. J. Supercritical Fluids. 1988;1:15-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solubilities of Solids and Liquids of Low Volatility in Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data. 1991;20:713-756.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solubility of the antibiotic Penicillin G in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercritical Fluids. 1999;15:183-190.

- [Google Scholar]

- S.I. Sandler, Chemical, Biochemical, and Engineering Thermodynamics, 4rd ed., John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2006.

- I. Kikic, M. Lora, A. Bertucco, A Thermodynamic Analysis of Three-Phase Equilibria in Binary and Ternary Systems for Applications in Rapid Expansion of a Supercritical Solution (RESS), Particles from Gas-Saturated Solutions (PGSS), and Supercritical Antisolvent (SAS), Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 36 (1997) 5507-5515.

- Prediction of solid solute solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide with organic cosolvents from the PR+COSMOSAC equation of state. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 2017;431:48-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of solid-liquid-gas equilibrium for binary mixtures of carbon dioxide + organic compounds from approaches based on the COSMO-SAC model. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2018;133:318-329.

- [Google Scholar]

- First-principles prediction of solid solute solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide using PR+COSMOSAC EOS. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 2020;522:112755

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of solid solute solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide with and without organic cosolvents from PSRK EOS. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2020;158:104735

- [Google Scholar]

- Measurement and Modeling of Solubility of Gliclazide (Hypoglycemic Drug) and Captopril (Antihypertension Drug) in Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. J. Supercritical Fluids. 2021;174:105244

- [Google Scholar]

- A generalized thermodynamic correlation based on three-parameter corresponding states. AIChE J.. 1975;21(3):510-527.

- [Google Scholar]

- A theoretically correct mixing rule for cubic equations of state. AIChE J.. 1992;38(5):671-680.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vapor-liquid equilibrium.11. New expression for excess free energy of mixing. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 1964;86(2):127-130.

- [Google Scholar]

- A modified Huron-Vidal mixing rule for cubic equations of state. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 1990;60:213-219.

- [Google Scholar]

- A critical evaluation on the performance of COSMO-SAC models for vapor-liquid and liquid-liquid equilibrium predictions based on different quantum chemical calculations. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2016;55:9312-9322.

- [Google Scholar]

- Improvements of COSMO-SAC for vapor-liquid and liquid-liquid equilibrium predictions. Fluid Phase Equilib.. 2010;297:90-97.

- [Google Scholar]

- A benchmark open-source implementation of COSMO-SAC. J. Chem. Theory Comput.. 2020;16:2635-2646.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modeling of the solubility of solid solutes in supercritical CO2 with and without cosolvent using solution theory. Korean J. Chem. Eng.. 2004;21:1173-1177.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vapor-liquid equilibria of CO2+C1-C5 alcohols from the experiment and the COSMO-SAC model. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2013;58:3420-3429.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of differential scanning calorimetry and X-ray powder diffraction to the solid-state study of metoclopramide. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal.. 1996;15:131-138.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103876.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1