Translate this page into:

Highly efficient UV–visible absorption of TiO2/Y2O3 nanocomposite prepared by nanosecond pulsed laser ablation technique

⁎Corresponding authors. drmosh@kfupm.edu.sa (Q.A. Drmosh), kaelsayed@iau.edu.sa (Khaled A. Elsayed)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Nanostructured TiO2-based composites are promising materials because of their superior optical, structural, and electronic properties relative to pristine nanostructured TiO2. The enhanced properties of TiO2-based composites have been used in several important applications such as gas sensors, solar cells, and photocatalytic applications. In the past, numerous materials have been coupled with TiO2 to enhance their optical properties. In this work, full-spectrum (UV and Visible) responsive TiO2 /Y2O3 nanocomposite has been synthesized via pulsed laser ablation in liquid (PLA) to study the impact of Y2O3 on the structural, morphology, and optical property of the TiO2. The nanostructured composites prepared were characterized by XRD, Raman spectroscopy, Field-Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FESEM) attached with Energy-Dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), Photoluminescence, XPS, and UV–Vis absorbance spectra. The result demonstrates that the coupling Y2O3 with TiO2 not only changes the structural, optical, and morphology of the TiO2 but also significantly amplified the light absorption characteristics of the TiO2 within the UV and visible region. The synthesized TiO2 /Y2O3 nanocomposite could potentially be useful for visible-light responsive applications.

Keywords

Pulsed laser ablation in liquid

Nanocomposites

Titanium oxide

Yttrium oxide

Optical properties

1 Introduction

Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is a well-known semiconductor material that has generated significant research interest due to its wide range of applications in photo remediation (Daghrir et al., 2013), water splitting (Nguyen et al., 2020), optical (Inpor et al., 2008), electronic (Phani and Santucci, 2006), sensors (Mele et al., 2021; Tian et al., 2021), and solar applications (Almomani et al., 2022). The use of TiO2 for various applications is due to its unique electronic and optical properties (Daghrir et al., 2013; Mele et al., 2021; Tian et al., 2021). TiO2 is non-toxic, hence it is useful in cosmetics(Dréno et al., 2019), biomedical (McNamara and Tofail, 2016), and anti-cancer applications (Elsayed et al., 2022b). TiO2 exists in four well-known polymorphs, namely, anatase (tetragonal), rutile (tetragonal), brookite (orthorhombic), TiO2 (B) (monoclinic) (Siddiqui, 2020). The nanostructured anatase TiO2 has received considerable interest in photocatalysis (Verbruggen, 2015) and dye-sensitized solar cells (Akila et al., 2019) research. Meanwhile, mixed polymorphs of TiO2 −20% rutile and 80% anatase are more efficient for biomedical applications (Jafari et al., 2020). Different TiO2 morphologies are appropriate for specific applications (Fahad et al., 2018; Gondal et al., 2015; Nabi et al., 2020). As such, several TiO2 morphologies have been prepared for different applications. Some of the common TiO2 morphologies include the quantum dot (Cui et al., 2014), nanoparticles, nanorods (Atabaev et al., 2016), nanoflowers (Dong et al., 2017), nanotubes(Cui et al., 2014), nanofibers (Kumar et al., 2007), etc., These morphologies are to a large extent a function of synthesis techniques used in the fabrication of nanostructured TiO2. The literature reflects that the following techniques have been used in the preparation of TiO2-based materials; sol–gel, hydrothermal, solvothermal, direct oxidation, chemical vapor deposition, physical vapor deposition, electrodeposition, etc (Chen and Mao, 2007).

The suitability of TiO2 for diverse application correlates with its wide and tunable electronic bandgap which range from 3.2 to 3.35 eV. Thus, permitting appropriate bandgap engineering for different applications (Chen and Mao, 2007). Studies have shown that the electronic bandgap is influenced by particle size, the presence of impurities, the shape of materials, surface charges, and phase transition (Mele et al., 2021; Tian et al., 2021), (Chen and Mao, 2007).

Despite the promising versatility of TiO2, pure TiO2 shows less promising results due to its high energy bandgap (Eg ∼ 3.6 eV), which limits its functionality to mainly absorb ultraviolet (UV) light which represents only 4% of the solar spectrum. Therefore, to maximize the absorption of solar light and transportation of charge, TiO2 has been doped and coupled with several nanomaterials such as Carbon/TiO2 (Irie et al., 2003), Pt/TiO2 (Yu et al., 2010), CdSe − TiO2 (Kongkanand et al., 2008), TiO2–Graphene (Wang et al., 2009), Graphene Oxide/TiO2 (Chen et al., 2010), TiO2/Au (Chen et al., 2010) for various applications. Despite the progress made in developing novel TiO2-based nanocomposites, there are still materials with tremendous capacity that have not been properly explored. One such material is yttrium oxide, which is an air-stable and solid material that is used for various applications such as the synthesis of inorganic compounds, microwave filters, and ultrafast sensors used in gamma-ray and X-rays.

It is important to state that studies on Y2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite are limited in the literature. A few examples of these studies are highlighted as follows: (Jun-ping and Ping, 2002) prepared Y2O3/TiO2 catalysts by the impregnation method, and the catalysts were used for the decomposition of sodium dodecylbenzene sulphonate. The report concluded that the photocatalytic activity of the Y2O3/TiO2 catalyst is about 2.4 times better than TiO2. Also, (Ravishankar et al., 2016) prepared Y2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite photocatalysts via a conventional hydrothermal method (Y2O3/TiO2 NC(HM)) and an ionic liquid assisted hydrothermal method (Y2O3/TiO2 ). Both materials were assessed for photocatalytic hydrogen production via water splitting. At 25% optimized weight, the Y2O3/TiO2 NC exhibits a 2-fold- improvement in the photocatalytic performance relative to 25 wt% Y2O3/TiO2. The study highlights that the synthesis approach is very important in fine-tuning the property of Y2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite which may affect the application performance.

In general, the literature survey revealed that both fundamental and applied research on Y2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite is lacking, as such, this present study is motivated by the gaps in research on the Y2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite. As noted by (Ravishankar et al., 2016), the synthesis approach affects the performance functionality of the prepared Y2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite. Hence, it is highly desirable to investigate the property of the Y2O3/TiO2 nanocomposite prepared by robust technique to uncover new information that could potentially be useful for different applications. In this contribution, we report the synthesis of TiO2/Y2O3 nanocomposite via pulsed laser ablation technique (PLA) for the first time. Further, we carried out thorough characterizations of the nanocomposite to gain better insight into the science of the material synthesized.

Interestingly, the result obtained shows a significant improvement in the absorbance characteristics which span the UV–visible region, which clearly shows a major improvement in the prepared nanocomposite relative to the previous studies where the absorbance enhancement is limited to the visible region. The PLA offers a green method for the synthesis of nanostructured materials. In PLA, a high-power nanosecond pulsed laser is used to ablate the composites in liquid and as a result, a nanostructured composite of TiO2/ Y2O3 is formed. The nanomaterial formed via PLA is highly pure which might not be easy to produce in many other chemical synthesis routes. More importantly, the approach does not depend on the use of a surfactant or any other chemical additives, thus, this safety component is very useful for the preparation of nanomaterials for biomedical applications (Drmosh et al., 2010; Elsayed et al., 2022c, 2022a; Gondal et al., 2012, 2010).

2 Experimental work

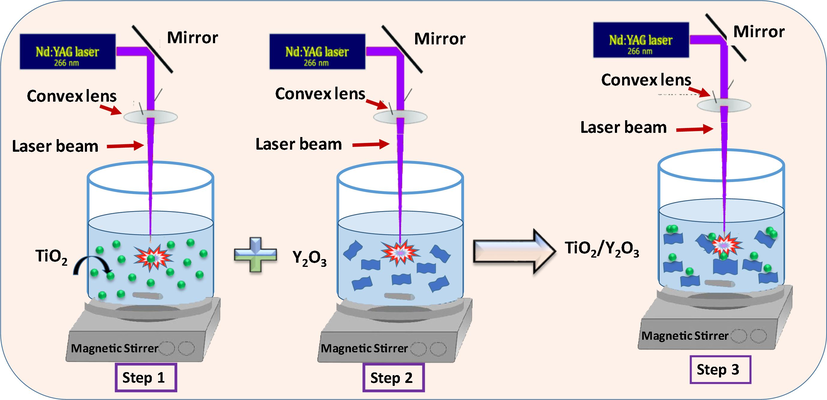

The laser ablation in liquid setup has been used to prepare the TiO2/ Y2O3 composite as shown in Fig. 1. A high purity TiO2 and Y2O3 (99.99%) were used as target materials. The two powders were purchased from Aldrich. 100 mg from each powder was dispersed separately in a beaker filled with 25 mL of deionized water and sonicated for 1 h. Firstly, the TiO2 colloidal solution was irradiated by a focused beam of a nanosecond pulsed Nd: YAG laser that operates at 266 nm, 30 m J, 10 ns, and 10 Hz for one hour. The laser beam was focused using a UV lens with a 200 mm focal length. The focus of the laser beam was adjusted under the surface of the liquid to avoid any high fluence that might cause ablation on the surface-air interface and to avoid the splashing of the liquid. The spot size on the liquid surface was kept at almost 5 mm. The colloidal solution was stirred at room temperature with a magnetic stirrer during the laser irradiation. Secondly, the colloidal solution of TiO2 was replaced by Y2O3 colloidal solution and irradiated under the same conditions. Finally, the two irradiated colloidal solutions of both TiO2 and Y2O3 were mixed, and then the mixture was irradiated with the focused laser beam for one hour to fabricate TiO2/Y2O3 nanocomposite.

Experimental steps used to fabricate TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites via PLA.

3 Characterization techniques

The as-fabricated nanostructured materials were characterized via various techniques to reveal the morphology, composition, and microstructure. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (FE-SEM, Lyra3, Tescan) with an accelerating voltage of up to 20 kV coupled with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) silicon drift detector (X-MaxN, Oxford Instruments) was used to identify the morphology of the fabricated samples. X-ray powder diffraction (XRD, Rigaku MiniFlex) was utilized with Cu Kα1 radiation (λ = 0.15416 nm), an accelerating voltage of 30 kV, and a tube current of 10 mA to accurately identify the crystalline properties of the samples. The Raman spectroscopy was carried out by a LabRam HR evolution Raman Spectrometer Horiba Scientific at room temperature with a 633 nm laser light. The photoluminescence (PL) measurements were conducted at room temperature at an excitation wavelength of 350 nm by a Fluorolog-3 spectrofluorometer system (Horiba Jobin-Yvon) in the emission spectral range 350–600 nm. The chemical composition of the nanocomposite was assessed using an ESCALAB 250Xi X-ray photoelectron spectroscope (XPS) that has a binding energy resolution of ± 0.1 eV. The UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Model SolidSpace-3700) was used to measure the optical properties of the synthesized materials using 10 mm quartz. The range of 200 – 900 nm was used to record the absorbance spectra.

4 Results and discussions

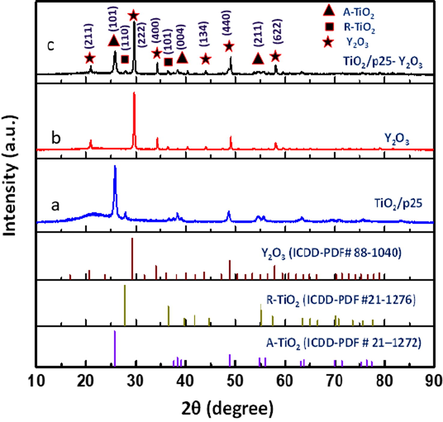

The XRD patterns of the TiO2/P25, Y2O3, and TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites fabricated by PLA in water are shown in Fig. 2 a, b, and c, respectively. As shown in Fig. 2a, TiO2/P25 patterns reveal the co-existence of rutile (ICDD-PDF #21–1276) and tetragonal anatase (ICDD-PDF # 21–1272) phases. The diffraction peaks of anatase TiO2 were found at 2θ = 25.78°, 36.58°, 37.53°, 38.32°, 48.55°, 53.89°, 63.22°, 68.76°, and 75.58° which are indexed to (1 0 1), (1 0 3), (0 0 4), (1 1 2), (2 0 0), (1 0 5), (2 1 1), (2 0 4), and (1 1 6) crystal planes of anatase phase of TiO2 (JCPDS #21–1272). Meanwhile, for the rutile TiO2, the 2θ are observed at 27.94°, 36.58°, 41.23°, 44.05°, and 56.64° (ICDD-PDF #21–1276) (Guo et al., 2017; Yao et al., 2020, 2017). The prominent peaks of the rutile TiO2 were identified at 27.94 and 36.58 which correspond to the (1 1 0) and (1 0 1), crystal planes, respectively. The diffraction peaks observed in Fig. 2b at 2θ = 20.94°, 29.61°, 34.28°, 36.37°, 40.38°, 43.98°, 47.43°, 49.03°, 50.59°, 53.73°, 56.67°, 58.09°, 59.53°, 60.91°, 64.99°, 71.50°, and 79.09° corresponded to cubic Y2O3 (ICDD-PDF #01–074-1828) (Benammar et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2013). The XRD pattern of TiO2/P25-Y2O3 (Fig. 2c) matches well with both Y2O3 and TiO2/P25, suggesting the successful integration of the two compounds. Furthermore, no other diffraction peaks except for that of the Y2O3 and TiO2/P25 phase were observed, indicating the high purity of the TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites sample and the successful integration of the two compounds. There is a reduction in the (1 0 1) peak belonging to the anatase TiO2 in the TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites. The size of the nanoparticles is calculated via Debye Scherrer’s formula D = k λ/β cosθ (Cullity, 1956), where k, λ, β and θ are a constant (0⋅94), the X-ray wavelength (0⋅154016 nm), the full wavelength at half maximum, and the half diffraction angle, respectively. The result demonstrated that the crystal size of the TiO2/P25 nanoparticles fabricated via PLA and the TiO2/P25 nanoparticles in the TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites sample is about 21 ± 5 nm. The average crystal size of the Y2O3 synthesized using PLA and the Y2O3 in the TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites sample is about 39 ± 10 nm.

XRD diffraction patterns (a) TiO2/P25, (b) Y2O3, and (c) TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites fabricated by PLA in water and their corresponding standards. XRD peaks of rutile and anatase phases are denoted by R and A, respectively.

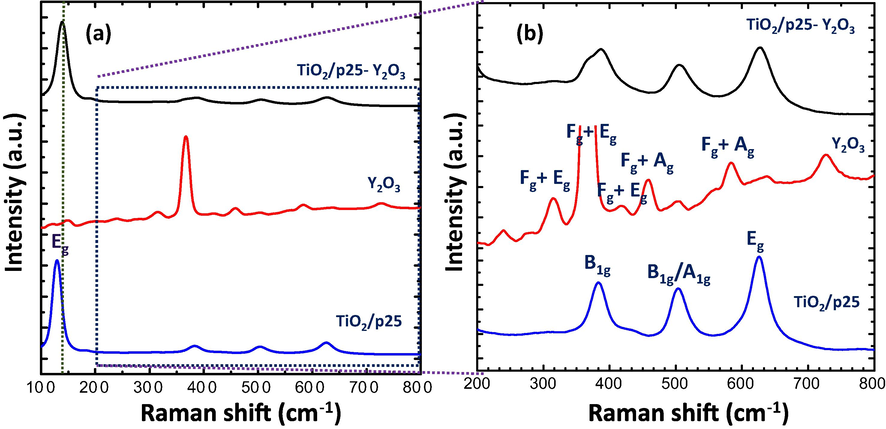

To further investigate the structural properties of the fabricated samples, Raman spectra were performed, and the obtained results are displayed in Fig. 3a and b. The nanostructured TiO2/P25 sample showed Raman bands at 132 cm−1 (Eg), 184 cm−1 (Eg), and 382 cm−1 (B1g), which could be ascribed to the O–Ti–O bending vibration of anatase TiO2. Other peaks observed at 505 cm−1 (A1g/ B1g), and 628 cm−1 (Eg) were ascribed to the stretching vibration modes of anatase TiO2 (Benammar et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2013). It is also important to mention that unlike the XRD the Raman spectra do not show the rutile phase in the TiO2/P25 sample and this is because Raman is slightly insensitive compared to XRD to the crystal structure of materials (Lu et al., 2013). According to several published works such as (Diego-Rucabado et al., 2020; Kruk, 2020), there are 22 active Raman lines in the Y2O3 Raman spectra (14Fg (triply degenerated), 4Eg (doubly degenerated) + 4Ag (singly degenerated)) as predicted by the theory. However, a few modes were experimentally observed which could be due to the superposition of different types of bands (Diego-Rucabado et al., 2020; Kruk, 2020). In this work, 10 characteristic lines of Y2O3 are observed at 155 cm−1 (Ag + Fg), 216 cm−1 (Eg), 320 cm−1 (Eg), 372 cm−1 (Ag + Fg), 459 cm−1 (Ag + Fg), 504 cm−1, 559 cm−1 (Ag + Fg), 584 cm−1, 634 cm−1, and 728 cm−1. The most intense line observed at around 372 cm−1 is characteristic of cubic Y2O3, indicating a large polarizability variation (Kumar et al., 2016). The Raman spectra of the TiO2/P25-Y2O3 sample show the Raman features of TiO2 with a small peak at 365 cm−1 related to Y2O3. Furthermore, the characteristic peaks of TiO2 are slightly shifted and become broader, indicating the decrease of TiO2 crystallinity or/and due to the decrease of TiO2 particle size in the nanocomposite sample. This observation is consistent with the XRD result shown in Fig. 2.

(a) Raman spectra, and (b) zoomed-in view of the TiO2/P25, Y2O3, and TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites fabricated by PLA.

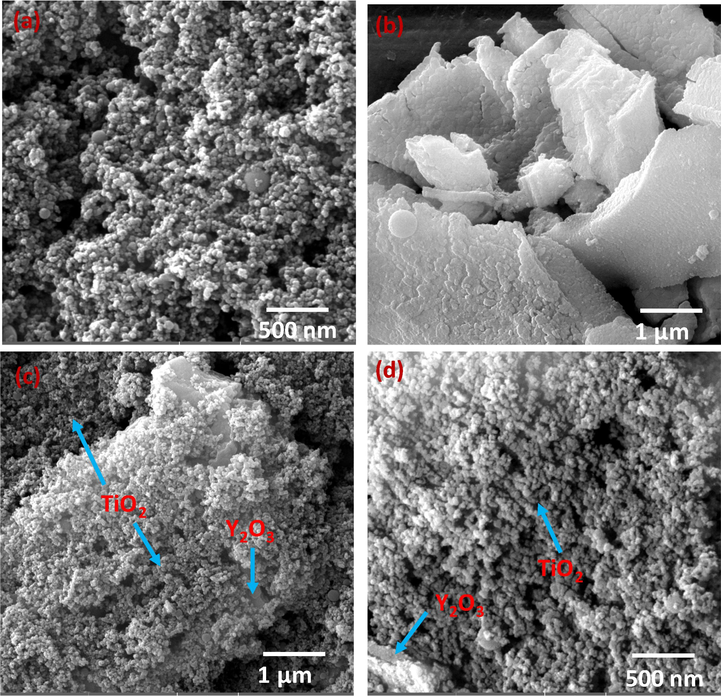

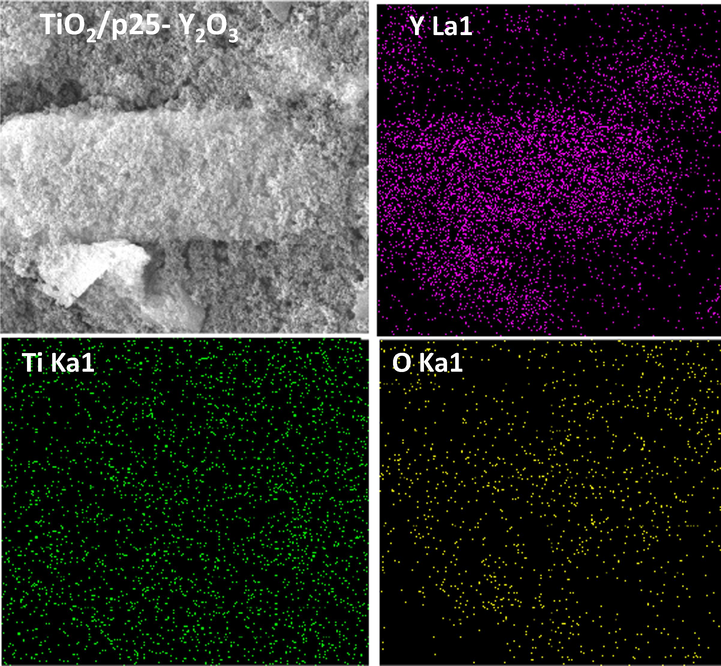

The fabricated materials were analyzed via a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM) attached with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) to investigate the morphology of TiO2/P25 and its dispersion on the Y2O3 sheet. Fig. 4 exhibits the FESEM micrographs of TiO2/P25, Y2O3, and TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites fabricated by PLA. Initially, TiO2/P25 nanoparticles demonstrated in Fig. 4a display sizes below 40 nm and random adhesion of nanoparticles. Furthermore, it can be observed from the FESEM image that the Y2O3 fabricated by PLA consists of several sheets or plate-like structures attaching. The image of After TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites (Fig. 4c d) shows the loading of TiO2/P25 nanoparticles on the surface of Y2O3, which confirmed the formation of TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites. Besides, Fig. 5 shows the elemental mapping of the TiO2/P25-Y2O3 sample in which the elements Ti, O, and Y are mapped in green, yellow, and red colors, respectively. This mapping confirmed the laser-anchoring of TiO2/P25 nanoparticles on Y2O3 sheets. Due to the unique attributes of the PLA technique, contamination-free TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites were fabricated with a straightforward procedure.

FESEM images of (a) TiO2/P25, (b)Y2O3, and (c and d) low and high magnification of TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites fabricated by PLA.

EDX mapping analysis of TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites synthesized by PLA.

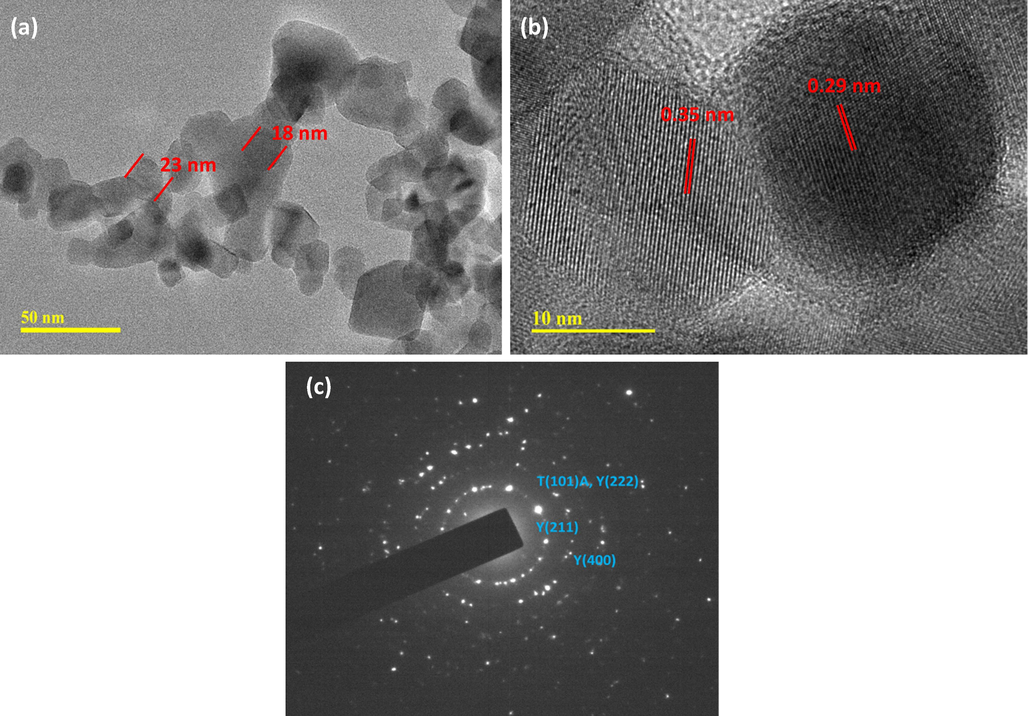

Fig. 6 (a-c) shows the TEM micrograph, High-resolution TEM, and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern of TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites. The dark contrast in Fig. 6a indicates the anchoring of the TiO2/P25 on the surface of Y2O3 nanosheets. The presence of Y2O3 material on the TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites can be seen clearly from the high-resolution TEM image (Fig. 6b). These images confirm the non-uniform clustering of Y2O3 in the nanocomposites. Fig. 6c shows the SAED pattern of TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites. The image confirms the polycrystalline structure of the TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposite with six diffraction rings that are consistent with the six prominent XRD diffraction peaks of the nanocomposite.

(a) TEM image, (b) HRTEM image, and (c) SAED pattern of TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites.

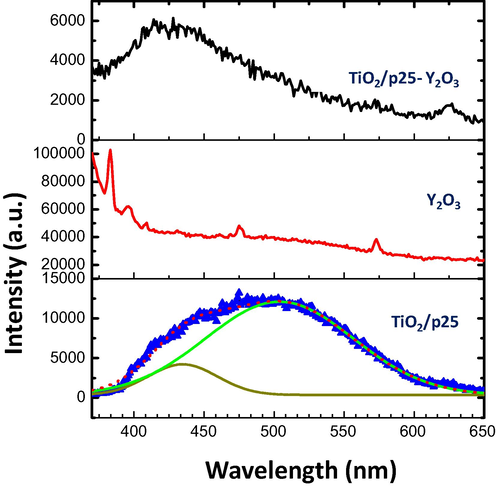

The room temperature photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the fabricated samples were performed to investigate the optical properties. PL spectrum of TiO2/P25 (Fig. 7) excited at 350 nm displayed a wide emission band and its Gaussian fitting showed two peaks centered at 430 nm and 501 nm, which could be caused by self-trapped excitons and oxygen vacancies, respectively [14–16]. The TiO2/P25-Y2O3 sample displayed emission at a wavelength of 421 nm, and the emission peak intensity is lower compared with that of TiO2/P25 nanoparticles. This confirms that the photoexcited e/h pairs are well separated making the TiO2/P25-Y2O3 suitable for many photocatalysts applications.

PL spectra of TiO2/P25, Y2O3, and TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites excited at 350 nm.

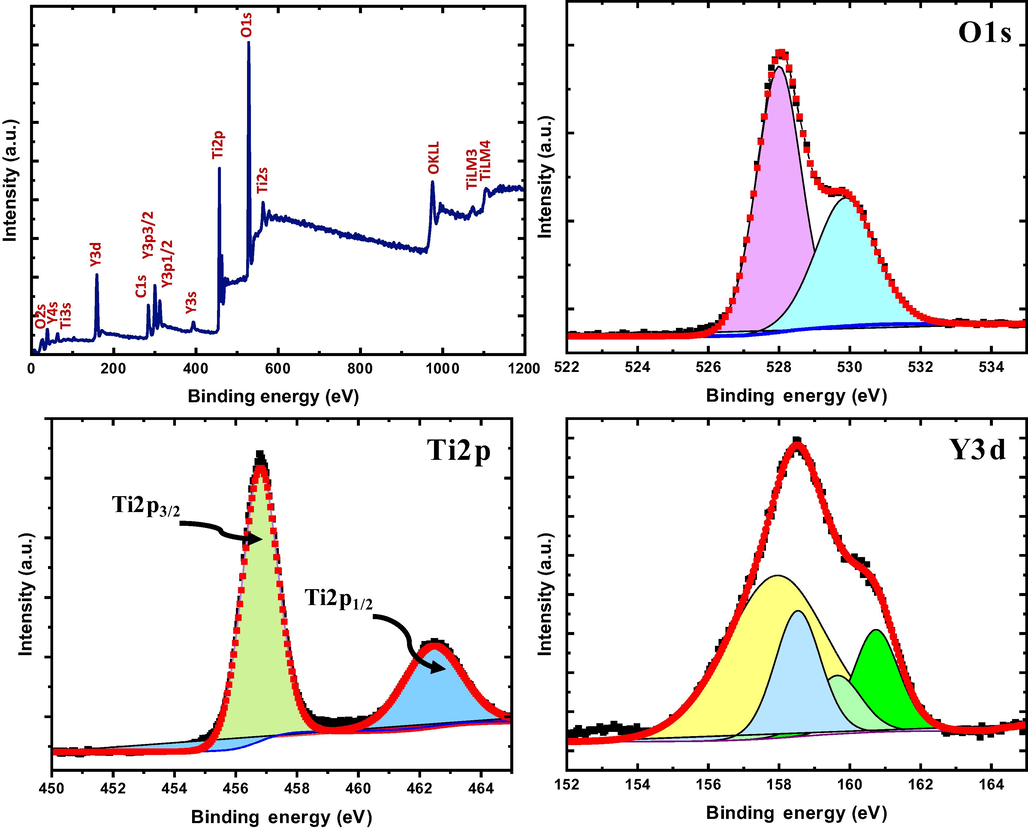

Fig. 8 shows the analysis of the chemical components of the TiO2/Y2O3 composite by XPS investigation. A quick survey scan revealed the presence of titanium, oxygen, carbon, and yttrium. The intensity of the O1s is the strongest, which can be attributed to the contribution of oxygen ions from the TiO2, Y2O3, and adventitious contamination from oxidation and/or water. The presence of titanium and yttrium in the survey scan indicates the formation of TiO2/Y2O3 composite. The carbon 1 s is the well-known adventitious carbon from atmospheric contamination. Fig. 8 (b, c, and d) show a narrow scan for O1s, Ti 2p, and Y 3d, respectively. For the O 1 s peak, two prominent peaks were observed at 528.5 eV and 530.2 eV which can be attributed to the oxygen in the anatase lattice from the oxides (TiO2) as well as oxygen defects and/or chemisorbed hydroxyls (OOH), respectively. For the Ti atoms, doublet symmetric peaks ascribed to Ti +4 were observed at approximately 457 eV and 462.5 eV which are assigned to Ti 2p 3/2 and Ti 2p ½, respectively (Pouilleau et al., 1997). The peak separation of 5.5 eV was noted between the spin split which is consistent with reported values in the standard (Greczynski and Hultman, 2020). For the yttrium atoms, the low XPS resolution of the two spin–orbit components (Y 3d 5/2 and Y 3d 3/2 electrons) indicates the presence of multiple chemical states. The binding–energy separation of 2 eV is found between the spin-split doublets, which is consistent with the XPS standard (‘X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Reference Pages: Yttrium’, n.d.).

(a) XPS survey, (b) O1s, (c) Ti2p, and (d) Y3d of TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites.

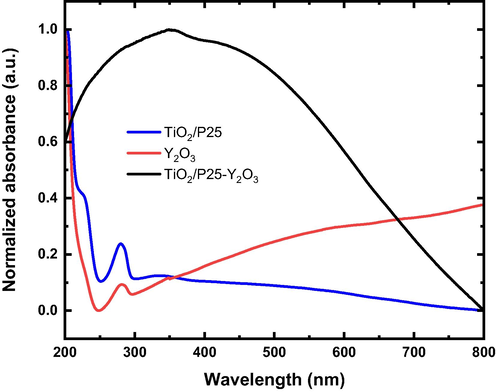

Fig. 9 shows the UV–Vis absorbance spectra of TiO2/P25, Y2O3, and TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites in the range of 200–800 nm. The absorption edge of TiO2/P25 and Y2O3 occurred at approximately 279 and 283 nm, respectively. The Y2O3 sample shows moderate absorbance across the visible range, whereas the TiO2/P25 sample showed absorbance in the UV region. Remarkably, TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites exhibit a very strong absorbance with the entire 250–650 nm spectrum, which is in a good agreement with the PL results. This result highlights the strong modification of the UV–VIS absorbance spectra of TiO2 due to the presence of Y2O3. Furthermore, the ionic radius of Y3+ is 0.088 nm, which is larger than that of Ti4+ (0.068 nm), so the Y ions should be difficult to get into the TiO2 lattice, in the contrary, partial Ti ions may have a chance to enter the Y2O3 crystal lattice, thus resulting in crystal defects and lattice distortion. The defects levels could make new capture centers of the light generated carriers, impeding them to recombine and prolong the lifetime of electrons and holes. This new observation provides a means of increasing the absorbance of TiO2 which can be useful in UV and visible light response applications.

UV–Vis absorbance spectra of TiO2/P25, Y2O3, and TiO2/P25-Y2O3 nanocomposites.

5 Conclusion

This study successfully synthesized TiO2 /Y2O3 nanocomposite using PLA in liquid for the first time. PLA-prepared nanostructures are unique and non-toxic because of the absence of chemical precursors or surfactants which makes nanostructures prepared via this route superior to any chemical approach. The structural, optical, and morphological properties of the nanocomposites were investigated using XRD, Raman spectroscopy, FESEM attached with EDX, photoluminescence, XPS, and UV–Vis absorbance spectra. The results obtained demonstrate that hybridizing TiO2 with Y2O3 significantly modifies the light absorption characteristics within the UV–visible region. This enhancement indicates that the nanocomposite could be useful for UV and visible light-responsive applications.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge to the Deanship for research and innovation, and the Ministry of education in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number IF 2020022Sci. The authors extend their great appreciation to the Interdisciplinary Research Center for Hydrogen and Energy Storage (IRC–HES), King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals (KFUPM) for support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- TiO2-based dye-sensitized solar cells. Nanomater. Sol. Cell Appl.. 2019;127–144

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Solar-driven hydrogen production from a water-splitting cycle based on carbon-TiO2 nano-tubes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2022;47:3294-3305.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pt-coated TiO2 nanorods for photoelectrochemical water splitting applications. Results Phys.. 2016;6:373-376.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The effect of rare earth element (Er, Yb) doping and heat treatment on suspension stability Y2O3 nanoparticles elaborated by sol-gel method. J. Mater. Res. Technol.. 2020;9:12634-12642.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of visible-light responsive graphene oxide/TiO2 composites with p/n heterojunction. ACS Nano. 2010;4:6425-6432.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Titanium Dioxide Nanomaterials: Synthesis. Properties, Modifications, and Applications. 2007

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Black TiO2 nanotube arrays for high-efficiency photoelectrochemical water-splitting. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2014;2:8612-8616.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Elements of X-ray diffraction. Reading Mass: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co.; 1956.

- Modified TiO2 for environmental photocatalytic applications: A review. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2013;52:3581-3599.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Diego-Rucabado, A., Candela, M.T., Aguado, F., González, J., Rodríguez, F., Valiente, R., Martín-Rodríguez, R., Cano, I., 2020. A Comparative Study on Luminescence Properties of Y2O3: Pr3+ Nanocrystals Prepared by Different Synthesis Methods. Nanomater. 2020, Vol. 10, Page 1574 10, 1574. https://doi.org/10.3390/NANO10081574.

- Reduced TiO2 nanoflower structured photoanodes for superior photoelectrochemical water splitting. J. Alloys Compd.. 2017;724:280-286.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Safety of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in cosmetics. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol.. 2019;33(Suppl 7):34-46.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spectroscopic characterization approach to study surfactants effect on ZnO 2 nanoparticles synthesis by laser ablation process. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2010;256:4661-4666.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrication of ZnO-Ag bimetallic nanoparticles by laser ablation for anticancer activity. Alexandria Eng. J.. 2022;61:1449-1457.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anticancer Activity of TiO2/Au Nanocomposite Prepared by Laser Ablation Technique on Breast and Cervical Cancers. Opt. Laser Technol.. 2022;149:107828

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Elemental analysis of limestone by laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy, scanning electron microscopy coupled with energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy and electron probe microanalysis. Laser Phys.. 2018;28:125701

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and characterization of SnO2 nanoparticles using high power pulsed laser. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2010;256:7067-7070.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of green TiO2/ZnO/CdS hybrid nano-catalyst for efficient light harvesting using an elegant pulsed laser ablation in liquids method. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2015;357:2217-2222.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of nickel oxide nanoparticles using pulsed laser ablation in liquids and their optical characterization. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2012;258:6982-6986.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy: Towards reliable binding energy referencing [WWW Document] Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Different Poisoning Effects of K and Mg on the Mn/TiO2 Catalyst for Selective Catalytic Reduction of NOx with NH3: A Mechanistic Study. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2017;121:7881-7891.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- TiO2 optical coating layers for self-cleaning applications. Ceram. Int.. 2008;34:1067-1071.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carbon-doped Anatase TiO2 Powders as a Visible-light Sensitive Photocatalyst.. 2003;32:772-773.

- [CrossRef]

- <p>Biomedical Applications of TiO2 Nanostructures: Recent Advances</p>. Int. J. Nanomedicine. 2020;15:3447-3470.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and photocatalytic performance of Y2O3/TiO2 conducted with the degradation of sodium dodecylbenzene sulphonate. IMAGING Sci. Photochem.. 2002;20:241.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Quantum dot solar cells. Tuning photoresponse through size and shape control of CdSe-TiO2 architecture. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2008;130:4007-4015.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk, A., 2020. Structural and Magneto-Optical Characterization of La, Nd: Y2O3 Powders Obtained via a Modified EDTA Sol–Gel Process and HIP-Treated Ceramics. undefined 13, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.3390/MA13214928

- Structural and Optical Properties of Electrospun TiO2 Nanofibers. Chem. Mater.. 2007;19:6536-6542.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Eu ion incorporation on the emission behavior of Y2O3 nanophosphors: A detailed study of structural and optical properties. Opt. Mater. (Amst). 2016;60:159-168.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Safe and facile hydrogenation of commercial Degussa P25 at room temperature with enhanced photocatalytic activity. RSC Adv.. 2013;4:1128-1132.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanoparticles in biomedical applications. 2016

- [CrossRef]

- Applications of TiO2 in sensor devices. Titan. Dioxide Its Appl.. 2021;527–581

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nabi, G., Ain, Q.U., Tahir, M.B., Nadeem Riaz, K., Iqbal, T., Rafique, M., Hussain, S., Raza, W., Aslam, I., Rizwan, M., 2020. Green synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles using lemon peel extract: their optical and photocatalytic properties. https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2020.1722816 102, 434–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/03067319.2020.1722816.

- Nguyen, T.P., Nguyen, D.L.T., Nguyen, V.H., Le, T.H., Vo, D.V.N., Trinh, Q.T., Bae, S.R., Chae, S.Y., Kim, S.Y., Le, Q. Van, 2020. Recent Advances in TiO2-Based Photocatalysts for Reduction of CO2 to Fuels. Nanomater. 2020, Vol. 10, Page 337 10, 337. https://doi.org/10.3390/NANO10020337.

- Microwave irradiation as an alternative source for conventional annealing: a study of pureTiO2, NiTiO3, CdTiO3 thin films by a sol–gel process for electronic applications. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2006;18:6965.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Surface study of a titanium-based ceramic electrode material by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Mater. Sci.. 1997;32:5645-5651.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen production from Y2O3/TiO2 nano-composites: a comparative study on hydrothermal synthesis with and without an ionic liquid. New J. Chem.. 2016;40:3578-3587.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, H., 2020. Modification of Physical and Chemical Properties of Titanium Dioxide (TiO 2) by Ion Implantation for Dye Sensitized Solar Cells . Ion Beam Tech. Appl. https://doi.org/10.5772/INTECHOPEN.83566.

- Gas sensors based on TiO2 nanostructured materials for the detection of hazardous gases: A review. Nano Mater. Sci.. 2021;3:390-403.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- TiO2 photocatalysis for the degradation of pollutants in gas phase: From morphological design to plasmonic enhancement. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev.. 2015;24:64-82.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Self-assembled tio2-graphene hybrid nanostructures for enhanced Li-ion insertion. ACS Nano. 2009;3:907-914.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hydrothermal synthesis and tunable multicolor upconversion emission of cubic phase Y2O3 nanoparticles. Adv. Condens. Matter Phys.. 2013;2013

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Reference Pages: Yttrium [WWW Document], n.d. URL http://www.xpsfitting.com/2012/02/yttrium.html (accessed 1.29.22).

- Enhancing the denitration performance and anti-K poisoning ability of CeO2-TiO2/P25 catalyst by H2SO4 pretreatment: Structure-activity relationship and mechanism study. Appl. Catal. B Environ.. 2020;269

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Selective catalytic reduction of NO x by NH 3 over CeO 2 supported on TiO 2: Comparison of anatase, brookite, and rutile. Appl. Catal. B Environ.. 2017;208:82-93.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hydrogen production by photocatalytic water splitting over Pt/TiO 2 nanosheets with exposed (001) facets. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2010;114:13118-13125.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]