Translate this page into:

Anti-corrosion and anti-microbial evaluation of novel water-soluble bis azo pyrazole derivative for carbon steel pipelines in petroleum industries by experimental and theoretical studies

⁎Corresponding author. emad_992002@yahoo.com (Emad E. El-Katori) emad_elkatori@sci.nvu.edu.eg (Emad E. El-Katori)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

In this research, we investigated the synthesis of a novel water-soluble bis azo pyrazolin-5-one (ABP) which was synthesized efficiently via the regioselective reaction of hydrazine with coumarin hydrazone (CMH). Also, we evaluate their anti-corrosion and anti-bacterial behavior. The inhibition efficiency of ABP in an acidic medium (1.0 M HCl) was evaluated using various electrochemical and surface morphology measurements. The novel bis pyrazole-based azo dye ABP (16 × 10−6 M) demonstrated a higher protection capacity (93.3 %). Tafel curves revealed that ABP was a mixed-type inhibitor. The adsorption of ABP on the C-steel (CS) surface is proven by the alteration in (Rct and Cdl) impedance characteristics and obeyed the Langmuir isotherm model. SEM/EDX, AFM, and XPS surface examinations confirmed the enhancement of an adsorbed film protects the CS surface from acid corrosion at the appropriate dose. Furthermore, theoretical calculations using DFT and MC simulations were performed to identify the active sites on ABP molecules in charge of the adsorption and surface protection of the CS. The adsorption of bis pyrazole-based azo dye on the metal surface explained the protection mechanism. Moreover, the ABP screened for its antimicrobial activity against sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB), and the calculated inhibition efficiency was 100 %. The current work presents significant results in manufacturing and producing novel water-soluble bis pyrazole-based azo dye derivative with high anti-corrosion and anti-microbial efficiency.

Keywords

Bis pyrazole

Carbon steel

Acid corrosion

Surface morphology

SRB

Theoretical studies

Nomenclature

- CS

-

C-steel

- NMR

-

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- AFM

-

Atomic force microscopy

- XPS

-

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy

- SEM/EDX

-

Scanning electron microscopy/ Electron dispersive X-ray

- OCP

-

Open circuit potential

- PDP

-

Potentiodynamic polarization

- EIS

-

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

- Ecorr

-

The corrosion potential

- icorr

-

Corrosion current density

- Rct

-

Charge transfer resistance

- Cdl

-

Double layer capacitance

- DFT

-

Density functional theory

- MC

-

Monte Carlo

- HOMO

-

Highest occupied molecular orbital

- LUMO

-

Lowest unoccupied molecular orbital

1 Introduction

Azo dyes possess a broad spectrum of unique biological applications (Banaszak-Leonard et al., 2021; Metwally et al., 2012), good dyeing (Abdou et al., 2012; Abdou et al., 2013; Metwally et al., 2012) and sensing properties (El-Mahalawy et al., 2022; El-Mahalawy et al., 2021). Among these compounds, pyrazoles are the crucial components of many synthetic dyes (Metwally et al., 2013; Abdou et al., 2013). Recently, considerable studies have been devoted to azo pyrazoles as scaffolds for corrosion inhibitors (Ferkous et al., 2020). It has been noted that several organic compounds having polar functionalities involving nitrogen, oxygen, or sulfur atoms in a conjugated system have strong inhibitory characteristics. To prevent the dissolving of carbon steel in acidic environments, aliphatic and aromatic amines, as well as nitrogen heterocyclic compounds, were explored as corrosion inhibitors. In general, it has been thought that the adsorption of the inhibitors onto the metal surface is the initial step in the action mechanism of the inhibitors in hostile acid conditions (Belakhdar et al., 2020). The nature and surface charge of the metal, the chemical structure of organic inhibitors, the distribution of charge in the molecule, the type of aggressive electrolyte, and the type of interaction between organic molecules are the primary types of interaction between organic inhibitors and the metal surface (El-Katori et al., 2019). Metallic corrosion is a basic phenomenon that has a significant impact on economics and protectively. CS is a type of iron alloy commonly utilized in the petrochemical and metallurgical sectors (Zerroug et al., 2021). It is also used as a building material due to its excellent mechanical properties and low cost (Boulechfar et al., 2021). However, it is quickly corroded in various environments (El-Katori et al., 2019; El-Katori and Hashem, 2022). Acid solutions are frequently utilized in industry in various applications (Suárez-Vega et al., 2021). Inhibitors are widely employed to minimize the metallic corrosion in acid media (Thomas, 1980). Organic molecules with N, O, S, and π-bonds, or aromatic rings, constitute the bulk of popular acid inhibitors (Zheng et al., 2022; Subramanyam et al., 1993). Generally, organic chemicals are efficient aqueous corrosion inhibitors for many metals and alloys (Babu et al., 2005; Fouda et al., 2005; Yurchenko et al., 2006). Chemical inhibitors are used in a variety of ways to reduce the corrosion rate of CS (El-Katori et al., 2019; El-Katori, 2020). Organic heterocyclic compounds have been utilized to shield iron or copper against corrosion (Mohammad et al., 2021; Abdou et al., 2022). As known SRB is one of the most bacterial-influenced corrosion (El-Saeed et al., 2022; Abbas et al., 2021; Abdou, 2013). There are several reports in the literature showing the performance of corrosion inhibitor against SRB (vide Table 1) (Eid et al., 2020; Abousalem et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019).

Inhibitor

Corrosion inhibition %

SRB inhibition %

Ref

TOS3

87.6 %

80 %

29

MA-1156

86.4 %

80 %

30

SPT

79.0 %

100 %

31

ABP

93.3 %

100 %

This work

With this object in view, and connected with our program focus coumarins and their isosteric compounds (Abdou, 2018; Abdou et al., 2019; Abdou et al., 2016; Abdou et al., 2019). In one of our projects, 4-hydroxycoumarin was employed to construct azo pyrazoles as promising corrosion inhibitors (Wang et al., 2019). The main target of this research is to prepare novel water-soluble bis azo pyrazolin-5-one (ABP) to assess its inhibition efficiency on CS in 1.0 M HCl via some electrochemical measurements such as PDP, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and surface characterization via SEM/EDX, AFM, and XPS analysis. Furthermore, DFT and MC simulations were studied to explore the potential inhibitory mechanisms of ABP on CS corrosion.

2 Experimental work

2.1 Materials and solutions

The CS specimens have composition by weight: C (0.17–0.20), Si (0.003), Mn (0.35), P (0.025), and Fe is the rest. CS's working electrode was glossed via SiC emery papers with grades (400–1200) before being submerged in the corrosive solution. The applicable solution was 1.0 M HCl, which was made by diluting 36 % HCl (supplied from El-Gomhoria Co., Egypt) with deionized water and standardized with Na2CO3. All solutions were made with analytical-grade chemicals and deionized water without any extra purification. The inhibitor concentrations (Cinh) varied from 1 × 10-6 M to 16 × 10-6 M.

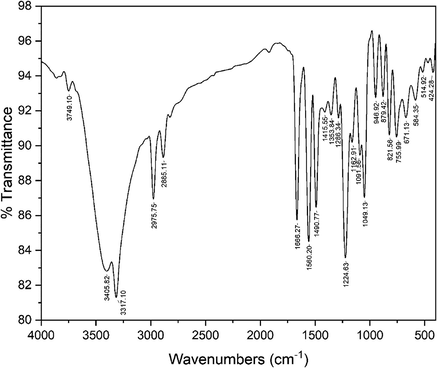

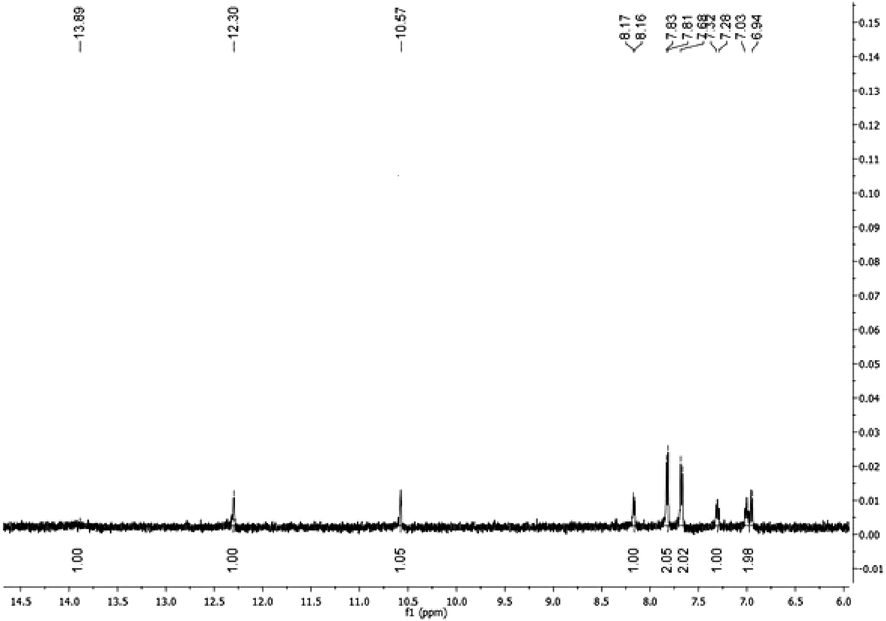

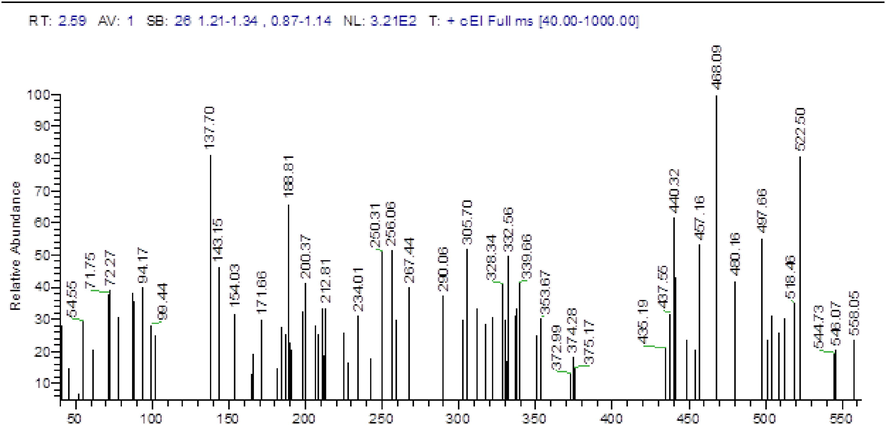

3,3‘-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4,4‘-diylbis(hydrazin-2-yl-1-ylidene))bis(chromane-2,4-dione) (CMH) was prepared according to our previous method (Thomas, 1980). Agilent Cary 660 FTIR spectrometer was used to record infrared spectra (IR). On a Bruker Avance III 500, 1H NMR (500 MHz) spectra were recorded. A Finnigan Incos 500 was used for Mass spectra.

2.2 Synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of inhibitor (ABP)

2.2.1 Synthesis of 4,4 -([1,1′-biphenyl]-4,4 -diylbis(hydrazin-2-yl-1-ylidene))bis(5-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-2,4-dihydro-3H-pyrazol-3-one) (ABP)

A mixture of CMH (5.3 g, 0.01 mol) and N₂H₄ (1.6 mL, 0.03 mol) in 100 mL (EtOH/AcOH, 1:1) was refluxed for 8 h then the solvent was concentrated under vacuum. The solid left was crystallized from EtOH /DMF mixture to give the ABP as red crystals, Yield = 5 g (89 %). IR (KBr) max/cm−1: 3749.10)OH(, 3405.82)NH(, 3317.10 (NH), 1666.27 (C⚌O), 1660.20 (C⚌N), 1224.63 (C—N).1H NMR (500 MHz) δ 13.89 (s, 2H, NH-Ph), 12.30 (s, 2H, NHCO), 10.57 (s, 2H, PhOH), 8.17 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H, ArH), 7.82 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 4H, ArH), 7.68 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4H, ArH), 7.30 (d, J = 17.6 Hz, 2H, ArH), 6.98 (d, J = 41.0 Hz, 4H, ArH); MS m/z (%): 558.05 (M+, 23), 468.09 (1 0 0).

2.3 Electrochemical measurements (EM)

At 25 °C, EM was measured using a three-electrode cell association, with a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) serving as the reference electrode, a counter electrode made of Pt wire, and a working electrode made of CS. The CS working electrode was coated with epoxy resin to expose only a geometrical surface area of 1 cm2 to the practical solution. A Versa STAT 4 potentiostat/galvanostat combined with a frequency response analyzer (FRA) and connected to a laptop “All in one” was employed to evaluate the anticorrosive effectiveness of the newly bis pyrazole-based azo dye ABP. For potentiodynamic polarization measurements, the potential was started from –1.2 to + 0.2 V vs open circuit potential (EOCP) at a sweep rate 1 mV s−1. Under open-circuit conditions, AC impedance measurements were made in the frequency range of 0.2 Hz to 105 Hz with a peak-to-peak amplitude of 10 mV.

2.4 Surface examinations (SEM/EDX, AFM, and XPS)

In both the absence and presence of the inhibitor ABP, the CS coupons were submerged in 1.0 M HCl for 14 h at 25 °C. The CS surface morphology was investigated via (SEM, JOEL, JSM-T20, Japan), and the elemental composition of CS surface was detected using energy dispersive Type: Philips X-ray diffractometer (pw-1390) equipped with Cu-tube (Cu Ka1, l = 1.54051 Å. Also, the corroded CS was inspected by model Wet–SPM (Scanning probe microscopy) Shimadzu, Japan at the Faculty of Engineering, Mansoura University and was applied for the atomic force microscopy (AFM) tests. Moreover, the protective film presented at the CS/solution interface for inhibited and uninhibited solutions was inspected through high-resolution XPS analysis for CS specimens in the applicable solution without and with 16 × 10-6 M of ABP for 14 h at 25 °C.

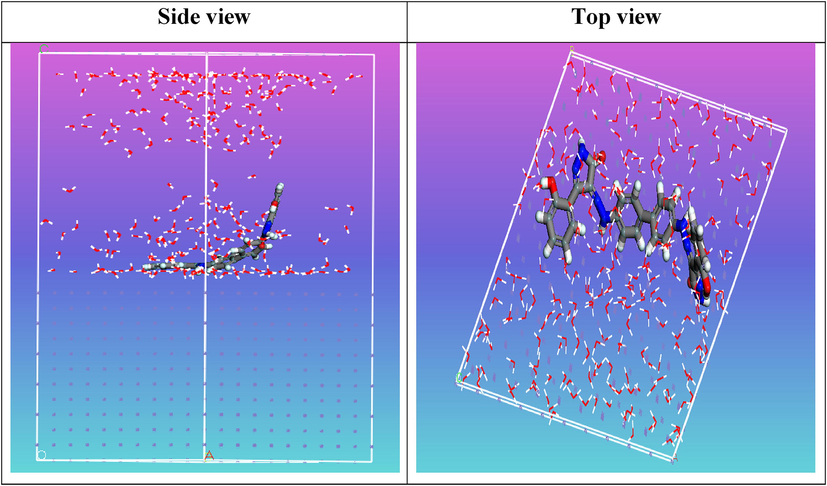

2.5 Theoretical studies

The density functional theory (DFT) approach was performed to implement the DFT computations using the Standard Gaussian 09 software package (revision A02). The novel bis pyrazole-based azo dye ABP structure was optimized in the aqueous phase via B3LYP/6-311G* basis set (Nady et al., 2021). The ionization potential (I), global hardness (η), electronegativity (χ), global softness (σ), as well as the dipole moment (μ) were all computed (Abd El-Lateef et al., 2019). The likely adsorption arrangements of the structure of ABP on the Fe (1 1 0) interface were identified for the MC simulations via the adsorption locator module in Accelrys Inc.'s Materials Studio program V7.0 (Dehghani et al., 2020). The interactions of the optimized ABP molecules and water molecules with the Fe (1 1 0) surface were examined in a simulation box with the dimensions (32.27 Å × 32.27 Å × 50.18 Å) (Abd El-Lateef et al., 2020). Our earlier investigations covered the details of computational studies (Migahed et al., 2004).

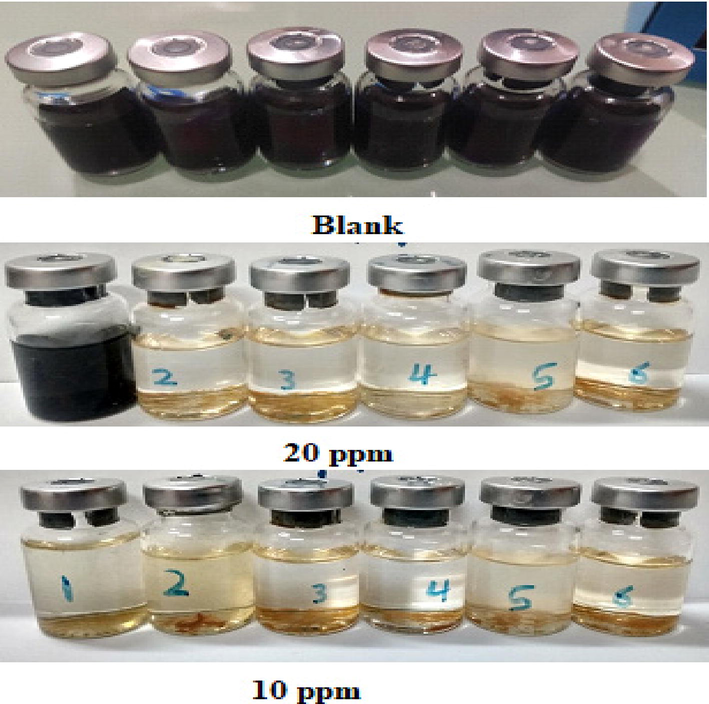

2.6 Microbial-induced corrosion (MIC)

The bottom level of produced oil tanks can be considered a major MIC source since it provides good anaerobic conditions for bacteria such as sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) to grow. MIC attacks caused by SRB in such vulnerable locations can lead to catastrophic consequences (Li et al., 2022). Egyptian Petroleum Research Institute (EPRI) provided specific growth media kits. Such media were formulated and enclosed in isolated vials to simulate the anaerobic conditions outlined in NACE TM0194-14-SG. The standard sampling procedure and data collection were executed following NACE TM0194/14 and our previous study (Bennet, 2017).

3 Results and discussion

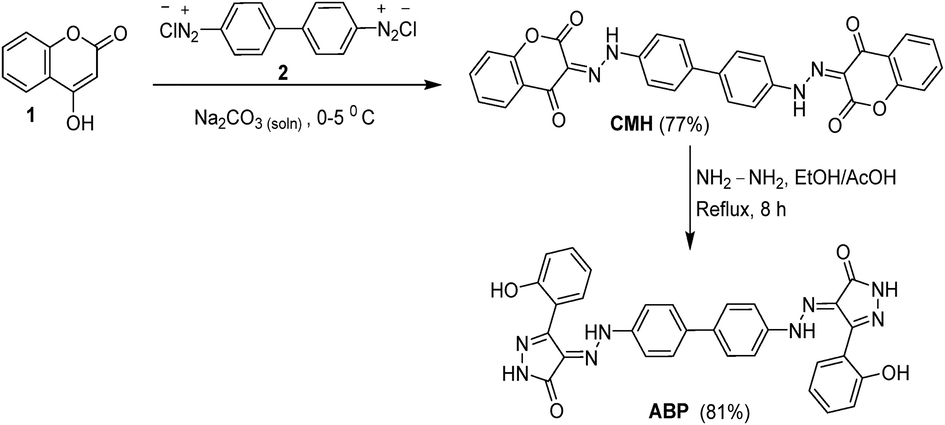

3.1 Synthesis of the studied corrosion inhibitor (ABP)

The synthetic strategy adopted for constructing ABP is outlined in Scheme 1. The versatile precursor CMH was synthesized according to our previous method by coupling bis(diazonium) salt of benzidine (2) with 4-hydroxycoumarin (1) (Abdou et al., 2012). The condensation of the latter precursor with hydrazine furnished the corresponding pyrazoline ABP. The structure of the latter ABP was elucidated based on spectroscopic data (vide experimental section), as confirmed in Figs. 1-3.

Preparation of the studied compound ABP.

FT-IR spectrum of ABP.

1H NMR spectrum of ABP in DMSO‑d6.

Mass spectrum of ABP.

3.2 Electrochemical measurements

3.2.1 Potentiodynamic polarization (PDP)

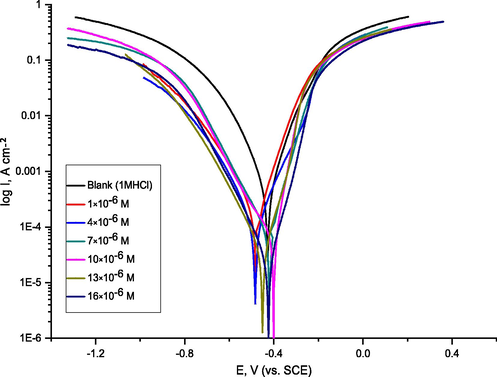

The Tafel curves for CS in 1.0 M HCl solution with and without various amounts of ABP are shown in Fig. 4 at 25 °C. Tafel–type behavior may be seen in the polarization curves. Table 2 shows the electrochemical data acquired from the inhibitor's polarization curves. According to the data, increasing the Cinh lowers the corrosion current density (icorr), yet the Tafel slopes (βa‚ βc) are nearly constant, indicating that the two reactions (anodic metal dissolution and cathodic hydrogen reduction) were influenced without changing the dissolution mechanism. With increasing inhibitor concentrations, the findings for βa and βc marginally altered, indicating that this molecule had an impact on the kinetics of CS dissolution and hydrogen evolution. They may operate as adsorption inhibitors because some active sites, such as hetero-atoms, depend on functional groups in the ABP to produce adsorption. The ABP inhibitor, which was absorbed on the CS, managed the cathodic and anodic reactions during the corrosion process. The ABP's structure and functional groups are crucial to the adsorption process. On the other hand, when neutral organic substances adsorb on the CS surface, an electron transfer occurs. The corrosion potential (Ecorr.) and the current density (icor) are found by the Tafel areas junction of cathodic and anodic curves, and the %IE is determined by the following equation (1) (Benabdellah et al., 2007):

Potentiodynamic polarization curves for C-steel dissolution in 1.0 M HCl in the absence and presence of various concentrations of ABP at 25 °C.

Compound

Conc., M

-Ecorr., mV(vs SCE)

icorr μA cm−2

βa mV dec-1

βc mV dec-1

θ

% IE

Blank (1 M HCl)

0.0

431

671.0

108

151

----

----

ABP

1 × 10-6

485

259.2

111

188

0.614

61.4

4 × 10-6

478

182.4

128

184

0.728

72.8

7 × 10-6

422

99.6

78

149

0.852

85.2

10 × 10-6

411

69.8

67

152

0.896

89.6

13 × 10-6

461

51.4

81

154

0.923

92.3

16 × 10-6

418

38.7

75

161

0.942

94.2

Where Icorr (free) and Icorr (Inh) are the corrosion current densities in the absence and presence of ABP, respectively. As reported in Table 2, increasing inhibitor concentrations significantly impact the icorr. and, as a result, CS acid protection in 1.0 M HCl. The investigated inhibitor, ABP, affects both anodic and cathodic overpotential as a mixed-type inhibitor. Cathodic hydrogen reduction processes and anodic metal dissolution were slowed when compared to 1.0 M HCl ((blank), and both Tafel slopes were shifted to higher positive and negative potentials (Saha et al., 2015).

3.2.2 Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS)

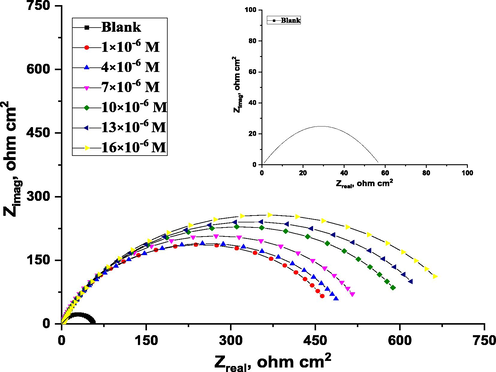

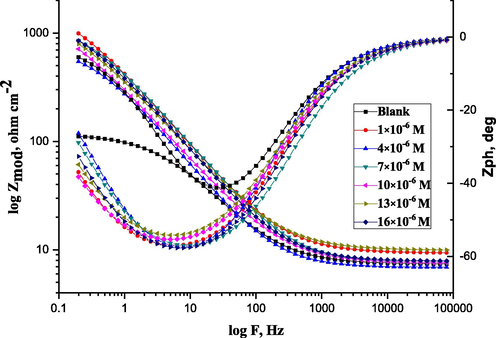

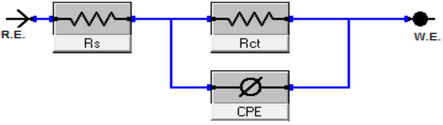

The electrode's covering layer can be characterized by EIS using a unique method that results in charge transfer resistance (Rct) (Quan et al., 2001; Paskossy, 1994; Lebrini et al., 2005). The film quality can also be calculated using the interface capacitance (Khaled, 2003). The coverage of organic compounds on the metal surface is determined not only by the nature of the metal and the structure of the organic compound but also by experimental parameters such as adsorbent concentrations and immersion time (Babic-Samardzija et al., 2005; McCafferty et al., 1991). The graphs in Fig. 5 demonstrate a similar type of Nyquist curves for CS in 1.0 M HCl with varying ABP concentrations at 25 °C. Because of the disintegration of the metal surface, which is unaffected by the ABP inhibitor, the existence of a semi-circle single leads to a single charge transfer process. All the impedance spectroscopy characteristics were measured at the corresponding open-circuit potentials. The Nyquist curves of ABP from separate semi-circles are perfect, as predicted by the EIS, owing to frequency disappearance. As shown in Fig. 6, the gained data revealed that each impedance curve consisted of a big capacitive loop with one capacitive time constant in the Bode–phase. Also, with increasing ABP concentrations, the diameter of the capacitive loop grows, indicating the degree of corrosion inhibition (Bessone et al., 1983). The acquired EIS data were fitted using the parallel electrical circuit model illustrated in Fig. 7. The charge-transfer resistance of the corrosion interfacial reaction (Rp) or (Rct), the double-layer capacitance (Cdl), and the solution resistance (Rs) are all included in this model. An outstanding match to this fit was produced by our experimental result. EIS parameters are shown in Table 3. The %IE was gained from the following equation (2) (Epelboin et al., 1972):

Nyquist fitted curves recorded for C-steel in 1.0 M HCl with and without various concentrations of ABP at 25 °C (inset. Blank).

Bode curves recorded for C-steel in 1.0 M HCl with and without various concentrations of ABP at 25 °C.

Parallel electrical circuit model utilized to fit EIS results.

Compound

Conc., M

Rct, Ω cm2

Cdl x10-6, µFcm−2

θ

% IE

Blank (1 M HCl)

0.0

56.7

188.6

---

---

ABP

1 × 10-6

512.4

179.8

0.889

88.9

4 × 10-6

525.2

161.4

0.892

89.2

7 × 10-6

551.8

152.7

0.897

89.7

10 × 10-6

631.4

141.9

0.910

91.0

13 × 10-6

675.2

133.4

0.916

91.6

16 × 10-6

733.4

132.8

0.923

92.3

Where Rct and Roct are the charge-transfer resistance with and without inhibitor, respectively.

The results reveal that the Rct data rises and the Cdl data reduce when the inhibitor ABP concentrations are improved. This is due to ABP molecules adsorbing on the CS surface gradually replacing water molecules, limiting the amount of dissolution. Furthermore, a slower corroding mechanism is frequently associated with high Rct values (Bosch et al., 2001). The decreased Cdl might be due to a reduction in the local dielectric constant and/or a rise e in the thickness of the electrical double layer (Bentiss et al., 2007), implying that the ABP molecules are adsorbed at the metal/solution interface. The %IE produced using EIS is like that calculated using PDP measurements.

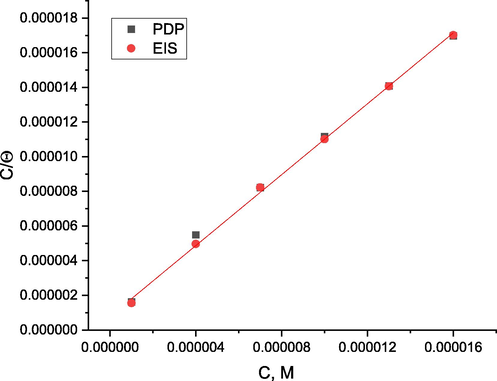

3.3 Adsorption isotherm

Deriving the adsorption isotherm that describes the metal/inhibitor/environment system is one of the best methods for quantitatively explaining adsorption (Szklarska-Smiaiowska, 1991). The surface coverage degree (θ) was valued at several ABP concentrations in 1.0 M HCl. The surface coverage degree (θ) was extracted from the investigated electrochemical measurements. After fitting surface coverage (θ) values in different adsorption isotherm models, the correlation coefficient (R2) was used to select the best isotherm, which was found to obey the Langmuir adsorption isotherm and described by the following equation (3) (El-Katori et al., 2022):

The inhibitor concentration is Cinh, and the adsorption equilibrium constant is Kads. Fig. 8 shows the plotting of (C/ θ) vs (C) for various ABP concentrations. ABP's straight lines relationship was discovered. The significant correlations (0.9989) and linearity of the graphs illustrate the effectiveness of this method. The adsorption potency or desorption between the adsorbate and the adsorbent in Table 3 was confirmed using Kads values. Also, Table 3 shows that the slopes didn’t correspond to the unity value predicted by a perfect Langmuir adsorption equation (Kaminski et al., 1973). The interaction of adsorbed ABP molecules on the CS surface could explain this variation. The adsorption equilibrium constant (Kads) is connected to the adsorption free energy (ΔG°ads) as follows (Putilova et al., 1960):

Langmuir adsorption isotherm plot for the adsorption of ABP on C-steel in 1.0 M HCl via different electrochemical measurements at 25 °C.

Where 55.5 is the molar concentration of water in mol/L, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature. Table 4 shows that large values of (ΔG°ads) and their negative sign are generally suggestive of strong contact and exceptionally effective adsorption (Quartarone et al., 2008). Physisorption is commonly associated with (ΔG°ads) values of − 20 kJ mol−1. Those at − 40 kJ mol−1 or above are nevertheless linked to chemisorption because electrons from inhibitor molecules are transferred to the metal surface to form a coordinating bond (Behpour et al., 2008). The values of (ΔG°ads) larger than − 40 kJ mol−1 indicate that chemisorption is involved in the adsorption mechanism.

Electrochemical methods

-ΔG◦ads (kJ mol−1)

K, M−1

Slope

R2

PDP

44.1

952,381

1.004

0.996

EIS

44.8

1,285,348

1.023

0.999

3.4 Surface assessment

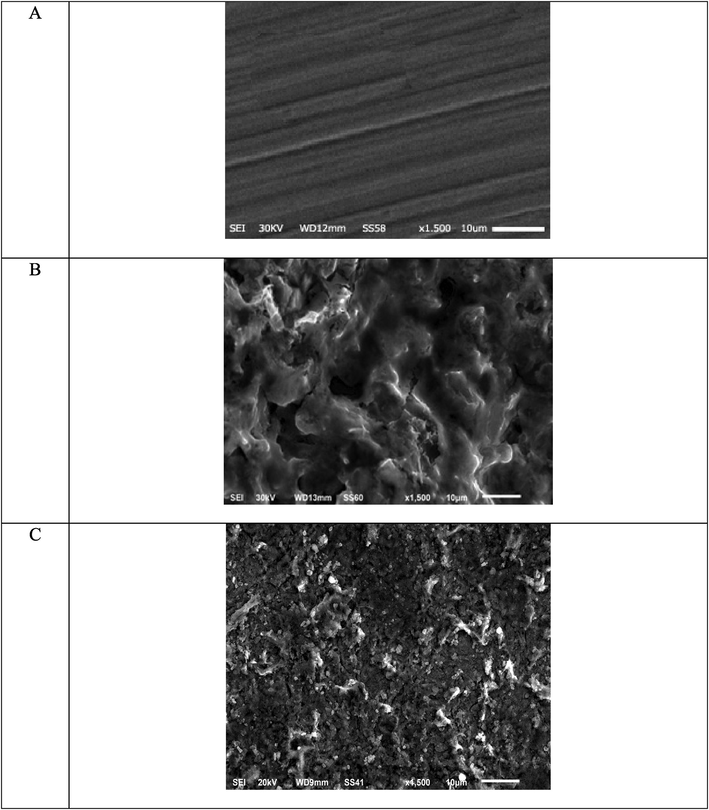

3.4.1 Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Fig. 9 shows the micrographs of CS specimens after 14 h of immersion in 1.0 M HCl with and without ABP (16 × 10−6 M). In the blank sample, it is evident that CS surfaces are severely corroded. It's worth noting that when ABP is present in the solution, the surface morphology of CS changes significantly, and the specimen surface smooths out. We observed the creation of a coating film on the CS surface, that is spread in random actions could be due to i) The adsorption of ABP on the CS surface to prohibit the active site on the CS surface or ii) ABP participation in the interaction with the reactive sites on the CS surface, generating a reduction in the contact between CS and the acidic environment and so an excellent inhibition capacity (Prabhu et al., 2008).

SEM micrograph (A) Free C-steel surface (B) after 14 h of inundation in 1.0 M HCl and (C) after 14 h of inundation in 1.0 M HCl + 16 × 10-6 M of ABP.

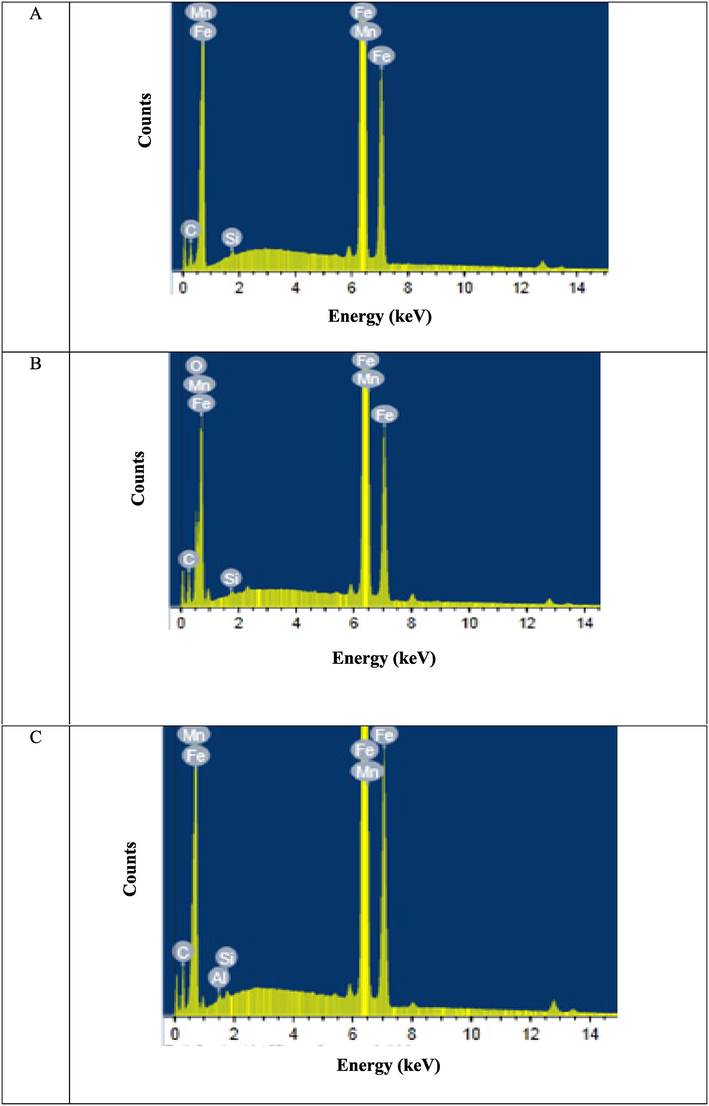

3.4.2 Energy dispersive X-ray (EDX)

EDX spectroscopy was used to identify the existing elements on the CS surface after 14 h of immersion in 1.0 M HCl with and without ABP (16 × 10-6 M), as illustrated in Fig. 10 and reported in Table 5. Figs. 10-A showed the EDX analysis of the composition of the pure surface of a CS specimen that hadn't been exposed to any ABP inhibitor or corrosive environment (1.0 M HCl). According to the EDX analysis, Fe was detected on the CS surface without rust formation. The EDX analysis of a CS surface after 14 h of immersion in a corrosive solution of 1.0 M HCl was shown in Figs. 10-B. According to EDX analysis, only Fe and oxygen were found, indicating that the passive film was connected to the Fe2O3 production. The EDX analysis of a CS surface after immersion in a corrosive solution of 1.0 M HCl and the presence of 16 × 10-6 M of ABP inhibitor was shown in Figs. 10-C. O, N and C were explained by additional lines in the EDX spectra (due to the O, N, and C atoms of ABP inhibitor molecules). These results confirmed that C, N, and O atoms coated the CS surface because the oxygen signal was missing on the CS surface exposed to uninhibited HCl, this film was formed due to the adsorption of the active chemical constituents of the synthesized inhibitor ABP onto the CS surface (Moretti et al., 1994).

EDX plots (A) Free C-steel surface (B) after 14 h of inundation in 1.0 M HCl and (C) after 14 h of inundation in 1.0 M HCl + 16 × 10-6 M of ABP.

(Mass %)

Fe

Mn

P

O

N

C

Cl

Free

98.2

0.93

0.02

–

–

0.85

–

HCl (1 M)

72.4

0.65

0.03

25.2

–

1.22

0.5

ABP

62.4

0.48

0.01

11.4

14.5

11.2

0.1

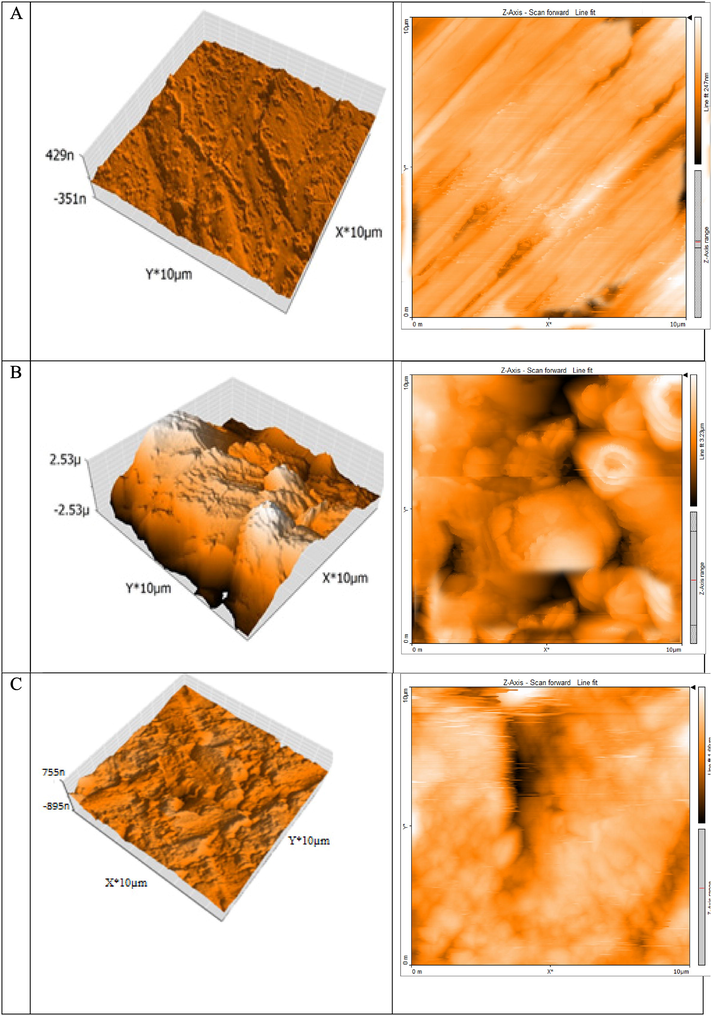

3D & 2D-AFM micrographs (A) Free C-steel surface (B) after 14 h of inundation in 1.0 M HCl and (C) after 14 h of inundation in 1.0 M HCl + 16 × 10-6 M of ABP.

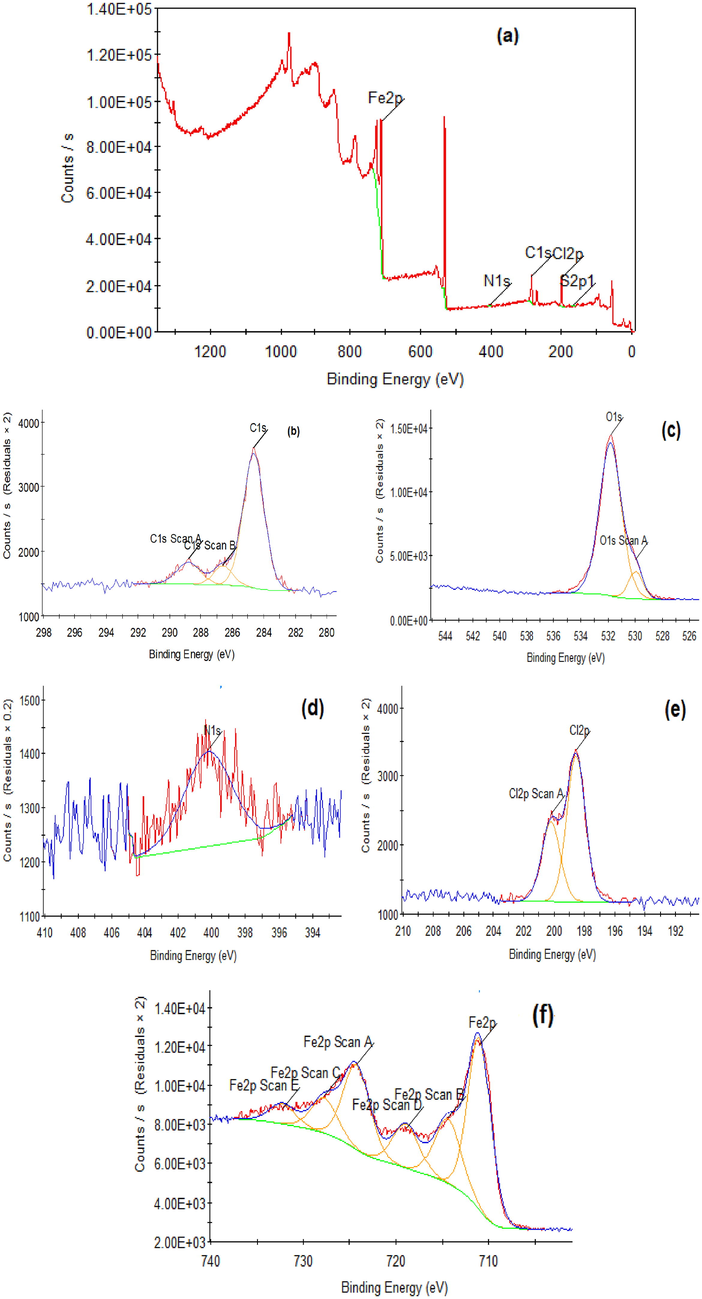

(a) XPS survey scan composition (All elements) of C-steel after 14 h immersion in 1.0 M HCl and 16 × 10-6 M of ABP and the profiles of (b) C 1 s, (c) O 1 s, (d) N 1 s and (e) Cl 2p (f) Fe 2p.

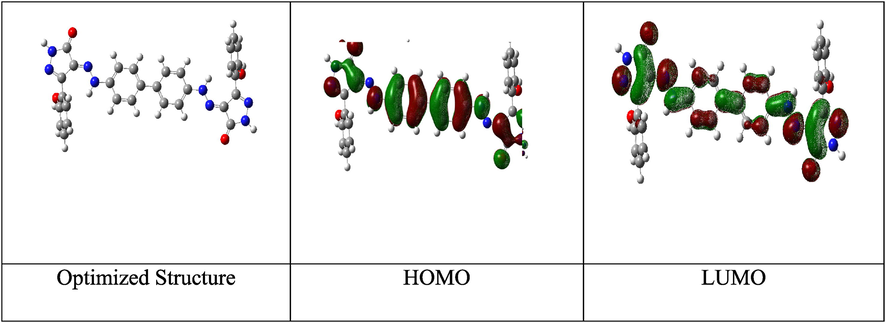

Optimized molecular structure with electronic densities of HOMO and LUMO of the tested compound ABP.

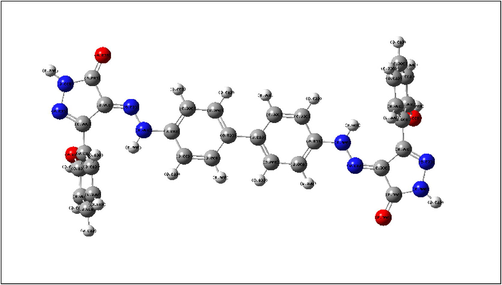

Mulliken population analysis with atomic charge ranges from -ve charged with red color and + ve charged with green color of the tested compound ABP.

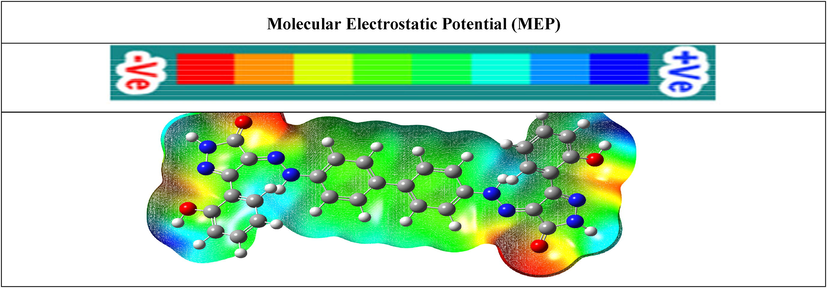

Graphical presentation of the MEP of ABP molecules using DMol3 module.

Side and top view snapshots of the most stable orientation of the tested compound ABP simulated as whole part in water condition.

SRB growth quantification at 10 and 20 ppm of ABP.

3.4.3 Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

AFM has been a significant apparatus to evaluate the surface morphology, which is an important method to help in discussing the ABP inhibitor effect on the metal/solution interface (Younis et al., 2020). Fig. 11 shows the AFM graphs of polished CS, CS in 1.0 M HCl without ABP, and CS in 1.0 M HCl with 16 × 10-6 M of ABP, respectively. The Sa (The roughness average) and Sq (The root mean square) height values are considerably less in the inhibited environment compared to the uninhibited environment. These parameters prove that there is a formation of a protective film consisting of Fe2+-ABP complex and the surface became smoother. The surface smoothness is due to the Fe2+-ABP complex on the CS surface, which inhibits CS corrosion. The adsorption of ABP on the CS surface results in lower roughness values in the presence of ABP than in the absence of ABP, as shown in Table 6. Therefore, it prevents CS corrosion in 1.0 M HCl, implying that this ABP is an excellent corrosion inhibitor.

Code

Status

Sa (nm)

A

Free metal (C-steel)

52

B

Blank (C-steel + 1 M HCl)

590

C

(C-steel + 1 M HCl + 16x10-6 M ABP)

110

3.4.4 X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS)

XPS was employed to characterize and identify ABP molecules' structure and chemical bonds and determine their adsorption on the CS interface. Fig. 12 depicts the XPS spectra obtained for CS immersed in 1.0 M HCl with ABP compound. The CS specimens had popular peaks for C 1 s, N 1 s, Cl 2p, O 1 s, and Fe 2p before and after adding the ABP inhibitor. Furthermore, in ABP, there are peaks for N 1 s, C 1 s, and O 1 s were found, confirming the adsorption of ABP molecules on the CS surface. In Fig. 12, C 1 s spectrum show three bands: one at 284.63 eV that could be assigned to C—C, C⚌C, or C—H bonds, one at 286.6 eV that could be attributed to C—N or C-Cl bonds, and one at 288.79 eV that could be attributed to C—O or C—N+ bonds (Ouici et al., 2017; Fan et al., 2020). The presence of Cl2 peak on CS surface treated with ABP is attributed to the interaction of Cl- and the positively charged Fe2+ (Bouanis et al., 2016). Cl 2p spectrum in Fig. 10, shows two peaks at 200.22 eV and 198.56 eV, which are assigned to Cl 2p1/2 (Solomon et al., 2019). The Fe 2p spectrum has five peaks: those at 711.01 eV and 714.41 eV are for Fe 2p3/2 of Fe2+, those at 718.93 eV are for Fe 2p3/2 of Fe3+, and those at 724. The peak at 24 eV is identified as Fe 2p1/2 of Fe2+, while the peak at 732.23 eV is identified as Fe 2p1/2 of Fe3+ (Hashim et al., 2019; Bommersbach et al., 2005). Also, O 1 s spectrum demonstrates two peaks at 529.96 eV are associated with O2– and may be related to O atoms assigned to Fe(II) & Fe(III) in both FeO and Fe2O3 oxides (Zarrouk et al., 2015); the second peak at 531.83 eV is attributed to OH–, which could be connected to Fe3+ in FeOOH (Mourya et al., 2016). Furthermore, N 1 s spectrum shows one peak at 400.23 eV attributed to the Fe-N bond (Kharbach et al., 2017). Finally, XPS results show that ABP adsorbs on the CS surface, producing a strong protecting film.

3.5 Theoretical studies

3.5.1 DFT

Fig. 13 shows the optimized structures, HOMO, and LUMO of the ABP compound. To establish the link between the inhibitor and the corrosion inhibition, DFT in the aqueous phase was used. EHOMO is taking charge of the electron-donating ability to the Fe of CS, corresponding to the Frontier molecular orbital theory (FMO). In contrast, ELUMO implies electron-accepting from metallic orbitals (Xia et al., 2008). The EHOMO and ELUMO provide helpful information regarding the inhibitor's inhibition efficiency. The easier it is to transfer electrons to the vacant metallic surface d-orbital, and the stronger the inhibitor's inhibition efficacy, the larger the inhibitor's EHOMO value. The ability of the fragment to absorb electrons increases with decreasing ELUMO rate (Fig. 13). The minor is the worth of ΔE, the extra possibility that the complex has inhibition efficacy (Zhang et al., 2018). According to Table 7, the molecule has a low E value, which increases its propensity to adsorb on the CS surface. Another measure that provides information about the protective power is ΔE. Because less energy is required to donate an electron from EHOMO to ELUMO, the lower value of ΔE, the better the inhibition efficiency (Ogunyemia et al., 2020). The ionization potential (-EHOMO) reveals that the examined ABP inhibitor has a higher tendency to give electrons. The lower the ionization potential [higher the value of (EHOMO) values, the greater the capacity of ABP to donate electrons to an appropriate electron acceptor, such as chemical species with vacant d-orbitals at low energy levels, such as the Fe surface atoms in our case (Guo et al., 2017). Furthermore, the dipole moment of ABP is about 1.1 Debye, suggesting that the ABP inhibitor has greater polarizability, facilitating its adsorption on the CS surface (Mishra et al., 2018).

Quantum Parameters

Total Energy (a.u)

EHOMO, eV

ELUMO, eV

ΔE, eV

ƞ

σ(S)

I

X

μ, Debye

ABP / Water

−3012.2

−0.2130

−0.1107

0.102

0.051

19.5

−0.162

0.162

1.1

In an acidic solution, the investigated inhibitor ABP has heteroatoms in its molecular structure that can be protonated. The Mulliken charges in the neutral state are determined and illustrated in Fig. 14 to determine which atoms of ABP inhibitor will be protonated. Atoms N8, N10, N11, O15, O22, N23, N24, O28, O35, and N36 of ABP inhibitor have the greatest negative values for the Mulliken charges listed in Table 8. As a result, these atoms are the active centers in ABP. They are responsible for nucleophilic attack on the Fe surface via electron/charge transfer from negatively charged centers to the Fe surface atoms' unoccupied d-orbital. Bold values indicate the hetero atoms with more negative Mulliken charges.

Mulliken charges on the atoms of ABP

Atoms

Mulliken charges

1C

−0.031565

2C

−0.110107

3C

−0.354321

4C

0.545123

5C

−0.177212

6C

−0.123006

7 N

0.003536

8 N

−0.635734

9 N

0.003511

10 N

−0.128836

11 N

−0.557554

12C

0.521061

13C

−0.367308

14C

0.169160

15O

−0.421362

16C

0.087528

17C

0.281110

18C

−0.252112

19C

−0.100042

20C

−0.199854

21C

−0.183406

22O

−0.604074

23 N

−0.128955

24 N

−0.557597

25C

0.521092

26C

−0.367292

27C

0.169149

28O

−0.421271

29C

0.087584

30C

0.281135

31C

−0.252092

32C

−0.100131

33C

−0.199728

34C

−0.183566

35O

−0.604091

36 N

37C

−0.635742

–0.031566

38C

−0.110153

39C

−0.354210

40C

0.544998

41C

−0.177167

42C

−0.123112

43H

0.179174

44H

0.182364

45H

0.174202

46H

0.177516

47H

0.403335

48H

0.375544

49H

0.176133

50H

0.171780

51H

0.168710

52H

0.231349

53H

0.398985

54H

0.375530

55H

0.176143

56H

0.171762

57H

0.168689

58H

0.231392

59H

0.398994

60H

0.403350

61H

0.179151

62H

0.182365

63H

0.174202

64H

0.177511

The molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) of an ABP provides information on the reactive sites for electrophilic and nucleophilic attacks. An electrophile is a reactant that gets the electron pair. Electrophilic inhibitors have an electron deficit in comparison to electrophilic inhibitors. An electrophile's comparative reactivity is determined by its structure and its nucleophilic reaction partner (Mayr et al., 2005). Electrophilic reactivity is depicted in red as presented in Fig. 15, while nucleophilic reactivity is depicted in blue. The negative areas are limited to O and N atoms, indicating the most suitable places for an electrophilic attack. In contrast, the positive areas are distributed throughout the ABP inhibitor, meaning nucleophilic attack sites.

3.5.2 MC simulation

MC simulation revealed the adsorption behavior of ABP on the CS surface, as well as the determination of their most suitable adsorption centers on the Fe (1 1 0) surface (Abdallah et al., 2018). As a result, Fig. 16 depicts the most suited adsorption configurations for ABP on the CS surface, described in an almost parallel or flat design, meaning increased adsorption extent and maximum surface coverage (Madkour et al., 2018). In addition, the parameters derived from MC simulations are shown in Table 9; the adsorption energy is a crucial directory that depicts both the adsorbate molecule's deformation energy and the rigid adsorption energy (¨Ozcan et al., 2004). Table 9 shows that ABP has higher adsorption energy (-2965.4 kcal mol−1), implying that the ABP has strong adsorption on the CS surface, forming an adsorbed coating and protecting it from corrosion, based on the empirical findings. If one of the adsorbates were absent, the adsorption energy would be dEads/dNi; hence, a high adsorption energy value indicates strong protection (Zhang et al., 2020). The dEads/dNi value (-197.8 kcal mol−1) for ABP (Table 9) is high, meaning that ABP molecules adsorb more readily on the CS surface.

Structures

Adsorption energy/kcal/mol

Rigid adsorption energy/kcal/mol

Deformation energy/kcal/mol

dEads/dNi. ABP kcal/mol

dEads/dNi. water kcal/mol

Fe (1 1 0)

−2965.4

−3102.6

137.2

−197.8

−7.6

ABP

water

Furthermore, the dEads/dNi values for water are around (-7.6 kcal mol−1), which is a small value, implying that ABP molecules have greater adsorption than water molecules on the CS surface. Therefore, it's possible to confirm that ABP molecules substitute water molecules on the CS surface. As a result, the ABP molecules bind to the CS contact, forming a strong adsorbed protecting layer that protects the surface from aggressive environments. Finally, experimental, and theoretical studies have validated this protection.

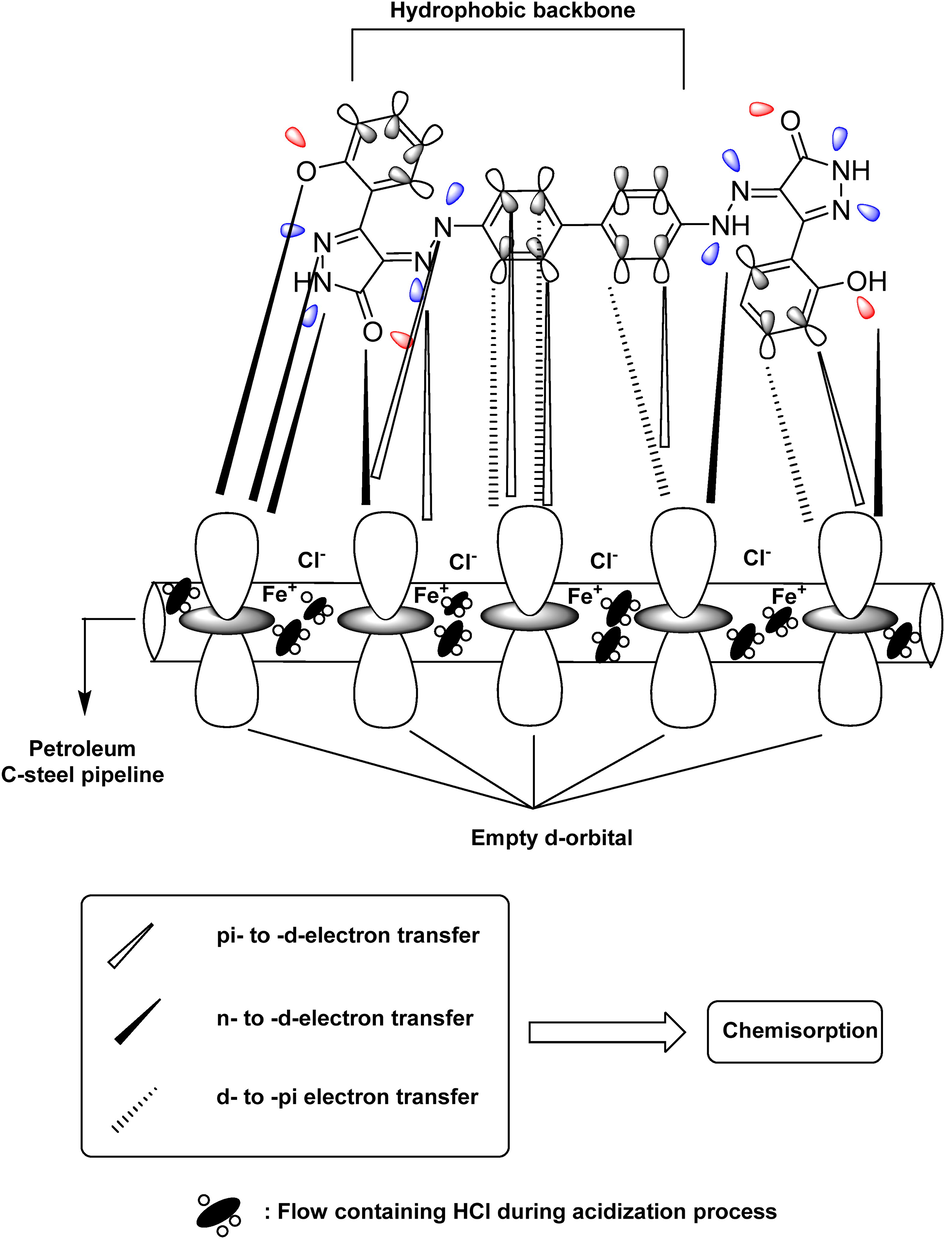

3.6 Corrosion mitigation mechanism

Firstly, we must realize the corrosion processes on the CS surface before the adsorption of the ABP inhibitor to understand the corrosion inhibition mechanism for CS in an acidic medium. The following steps describe the anodic and cathodic reactions that occur during the corrosion of CS in HCl solution (El-Katori, 2020; Guo et al., 2020):

(i) Anodic reaction (Metal dissolution):

(ii) The cathodic reaction (Hydrogen evolution):

Corrosion protection is primarily achieved through the adsorption of a protective inhibitor coating on the metal surface. The surface charge of CS in acidic solutions is positive, according to earlier investigations (Hou et al., 2020), and this promotes the adsorption of anions (such as Cl-), resulting in the formation of a negative anion layer via electrostatic attraction. Finally, ABP establishes chemical bonds (chemisorption) with CS by interacting lone pairs of electrons from N and O atoms and phenyl ring π-electrons with vacant d-orbitals of Fe on the CS surface (Scheme 2) (Shalabi et al., 2021). The values of ΔG°ads agreed with the previous assumptions, showing ABP chemisorption on the CS surface. Furthermore, computational studies revealed that the active sites in ABP molecules are centered on the phenyl and pyrazole moieties that advance electrons to interact with the d-orbitals of iron on CS, suggesting that CS is highly corrosion-resistant corrosive media.

Proposed mechanism of ABP action on the C-steel surface.

3.7 Microbial-induced corrosion (MIC)

Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) growth rate was tested to study the effect of ABP compounds as an antibacterial agent against prospective MIC attacks. Two concentrations of the inhibitor ABP (10 and 20 ppm) were introduced into the growth media vials by being injected into the sealed vials, then a series of different concentrations were developed using the serial dilution approach. Fig. 17 depicts the captured photos for the incubated blank vials without inhibitor along with the serially diluted sample vials with the injected ABP inhibitor after a period of 21-days. The inhibitory action of the ABP compound was evaluated via the reduction of the number of blackened vials (infected vials) regarding that of the blank. ABP has shown significant biocidal activity. The calculated inhibition efficiency was 100 % since the measured bacterial count was 101 cell/ml for 10 ppm and 0 cell/ml in the 20-ppm concertation range (Table 10).

Compound

Conc., ppm

SRB count (cell/ml)

Reduction in SRB count (cell/ml)

Efficiency

Blank

-----

106

-----

-----

ABP

10

101

105

83.3 %

20

100

106

100 %

4 Conclusions

This paper showed the preparation of the unreported bis pyrazole-based azo dye with good yields and used as a good and effective corrosion inhibitor in an acidic medium. The corrosion protection measurements assessed using PDP, EIS, SEM/EDX, AFM, and XPS techniques were all in good agreement. The ABP is a mixed-type inhibitor, according to PDP measurements. The variation in Rct and Cdl values with changing ABP concentrations revealed a protective layer via ABP adsorption by replacing adsorbed H2O molecules. According to the Langmuir adsorption model, the ABP molecules were adsorbed on the CS surface via the chemisorption process. SEM/EDX and AFM surface morphology analyses revealed a significant improvement in CS corrosion by enhancing the protecting film on the CS surface at the optimum concentration (16 × 10−6 M) of ABP. Furthermore, XPS measurement confirmed the ABP compound's adsorption on the CS surface. Theoretical calculations improved the experimental results, revealing that ABP is an excellent CS corrosion inhibitor. Water-soluble bis pyrazole-based azo dye compound ABP is a safe and effective corrosion inhibitor, and it should be utilized to protect CS in acidic environments. Moreover, a preliminary study of ABP had good antimicrobial activity against sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Multifunctional aspects of the synthesized pyrazoline derivatives for AP1 5L X60 steel protection against MIC and acidization: Electrochemical, in-silico and SRB insights. ACS Omega. 2021;6(13):8894-8907.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solvent-free synthesis and corrosion inhibition performance of ethyl 2-(1,2,3,6-tetrahydro-6-oxo-2- thioxopyrimidin-4yl) ethanoate on CS in pickling acids: experimental, quantum chemical and Monte Carlo simulation studies. J. Mol. Liq.. 2019;296:111800-111815.

- [Google Scholar]

- Corrosion inhibition and adsorption features of novel bioactive cationic surfactants bearing benzenesulphonamide on C1018-steel under sweet conditions: combined modeling and experimental approaches. J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;320:114564-114584.

- [Google Scholar]

- Eco-friendly synthesis, biological activity and evaluation of some new pyridopyrimidinone derivatives as corrosion inhibitors for API 5L X52 CS in 5% sulfamic acid medium. J. Mol. Struct.. 2018;1171:658-671.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thiophene-based azo dyes and their applications in dyes chemistry. Am. J. Chem.. 2013;3(5):126-135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemistry of 4-hydroxy-2 (1H)-quinolone. part 2. as synthons in heterocyclic synthesis. Arab. J. Chem.. 2018;11(7):1061-1071.

- [Google Scholar]

- A worthy insight into the dyeing applications of azo pyrazolyl dyes. Int. J. Modern Org. Chem.. 2012;1(3):165-192.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, structure elucidation and application of some new azo disperse dyes derived from 4-hydroxycoumarin for dyeing polyester fabrics. Am. J. Chem.. 2012;2(6):347-354.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, spectroscopic studies and technical evaluation of novel disazo disperse dyes derived from 3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-2-pyrazolin-5-ones for dyeing polyester fabrics. Am. J. Chem.. 2013;3(4):59-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of tolyl guanidine as copper corrosion inhibitor with a complementary study on electrochemical and in silico evaluation. Sci. Rep.. 2022;12(1):1-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advancements in tetronic acid chemistry. part 2: use as a simple precursor to privileged heterocyclic motifs. Mol. Divers.. 2016;20(4):989-999.

- [Google Scholar]

- Advancements in tetronic acid chemistry. Part 1: Synthesis and reactions. Arab. J. Chem.. 2019;12(4):464-475.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and chemical transformations of 3-acetyl-4-hydroxyquinolin-2 (1 H)-one and its N-substituted derivatives: bird's eye view. Res. Chem. Intermed.. 2019;45(3):919-934.

- [Google Scholar]

- A complementary experimental and in silico studies onthe action of fluorophenyl 2, 2′ bichalcophenes as ecofriendly corrosion inhibitors and biocide agents. J. Mol. Liq.. 2019;276:255-274.

- [Google Scholar]

- Properties of hybrid sol-gel coatings with the incorporation of lanthanum 4-hydroxy cinnamate as corrosion inhibitor on carbon steel with different surface finishes. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2021;561:149881

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitive properties and surface morphology of a group of heterocyclic diazoles as inhibitors for acidic iron corrosion. Langmuir. 2005;21:12187-12196.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effect of isomers of some organic compounds as inhibitors for the corrosion of CS in sulfuric acid. Anti-Corros. Meth. Mater.. 2005;52:219-225.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical and theoretical investigation on the corrosion inhibition of mild steel by thiosalicylaldehyde derivatives in hydrochloric acid solution. Corros. Sci.. 2008;50:2172-2181.

- [Google Scholar]

- Belakhdar Amina, Hana Ferkous, Souad Djellali, Rachid Sahraoui, Hana Lahbib, Yasser Ben Amor, Alessandro Erto, Marco Balsamo, Yacine Benguerba, 2020. Computational and experimental studies on the efficiency of Rosmarinus officinalis polyphenols as green corrosion inhibitors for XC48 steel in acidic mediu., Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 606, 125458.

- Inhibitive action of some bipyrazolic compounds on the corrosion of steel in 1.0 M HCl. Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2007;105:373-379.

- [Google Scholar]

- Oilfield Microbiology: Effective Evaluation of Biocide Chemicals. SPE/IATMI Asia Pacific Oil & Gas Conference and Exhibition. Society of Petroleum Engineers; 2017.

- Understanding the adsorption of 4H–1,2,4-triazole derivatives on mild steel surface in molar hydrochloric acid. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2007;53:3696-3704.

- [Google Scholar]

- AC-impedance measurements on aluminium barrier type oxide films. Electrochim. Acta. 1983;28:171-175.

- [Google Scholar]

- An enhancement on corrosion resistance of low carbon steel by a novel bio-inhibitor (leech extract) in the H2SO4 solution. Surf. Interfaces. 2021;24:101159

- [Google Scholar]

- Formation and behaviour study of an environment-friendly corrosion inhibitor by electrochemical methods. Electrochim. Acta. 2005;51:1076-1084.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical frequency modulation: a new electrochemical technique for online corrosion monitoring. Corrosion. 2001;57:60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Corrosion inhibition performance of 2,5-bis(4-dimethylaminophenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole for CS in HCl solution: gravimetric, electrochemical and XPS studies. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2016;389:952-966.

- [Google Scholar]

- DFT/molecular scale, MD simulation and assessment of the eco-friendly anti-corrosion performance of a novel Schiff base on XC38 carbon steel in acidic medium. J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;344:117874

- [Google Scholar]

- A detailed study on the synergistic corrosion inhibition impact of the quercetin molecules and trivalent europium salt on mild steel; electrochemical/surface studies, DFT modeling, and MC/MD computer simulation. J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;316:113914-113930.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tetrazole-based organoselenium Bi-functionalized corrosion inhibitors during oil well acidizing: experimental, computational studies, and SRB bioassay. J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;298:111980

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of Echium Angustifolium mill extract in the corrosion mitigation of CS in sulfuric acid solution. Protect/ Metals Phys. Chem. Surf.. 2020;56(5):1081-1095.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibitive properties and computational approach of diselenide derivatives on mild steel corrosion in acidic environment. Russ. J. Electrochem.. 2019;55(12):1320-1335.

- [Google Scholar]

- Corrosion mitigation of CS by spin coating with novel Ag–TiO2 nanocomposite thin films in acidic solution: fabrication, characterization, electrochemical and quantum chemical approaches. Surf. Coat. Technol.. 2019;374:852-867.

- [Google Scholar]

- The inhibition activity of lemongrass extract (LGE) for mild steel acid corrosion: electrochemical, surface and theoretical investigations. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater.. 2022;69(1):71-80.

- [Google Scholar]

- The Synergistic inhibition between the aqueous valerian extract and zinc ions on mild steel for the corrosion protection in acidic environment. Zeitschrift Phys. Chem.. 2019;233(12):1713-1739.

- [Google Scholar]

- Imidazole derivatives based on glycourils as efficient anti-corrosion inhibitors for copper in HNO3 solution: synthesis, electrochemical, surface, and theoretical approaches. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp.. 2022;649:129391

- [Google Scholar]

- Structural, spectroscopic and electrical investigations of novel organic thin films bearing push-pull azo–phenol dye for UV photodetection applications. Spectrochim. Acta A. 2021;248:119243

- [Google Scholar]

- Physical and optoelectronic characteristics of novel low-cost synthesized coumarin dye-based metal-free thin films for light sensing applications. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022;137:106225

- [Google Scholar]

- An innovative SiO2-pyrazole nanocomposite for Zn (II) and Cr (III) ions effective adsorption andanti-sulfate-reducing bacteria from the produced oilfield water. Chem: Arab. J; 2022. p. :103949.

- Use of impedance measurements for the determination of the instant rate of metal corrosion. J. Appl. Electrochem.. 1972;2:71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Trazodone as an efficient corrosion inhibitor for CS in acidic and neutral chloride-containing media: facile synthesis, experimental and theoretical evaluations. J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;311:113302

- [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic influence of iodide ions on the inhibition of corrosion of CS in sulphuric acid by some aliphatic amines. Corros. Sci.. 2005;47:1988-2004.

- [Google Scholar]

- Toward understanding the anticorrosive mechanism of some thiourea derivatives for CS corrosion: a combined DFT and molecular dynamics investigation. J. Colloid Interf. Sci.. 2017;506:478-485.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multidimensional insights into the corrosion inhibition of 3,3-dithiodipropionic acid on Q235 steel in H2SO4 medium: a combined experimental and in silico investigation. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2020;570:116-124.

- [Google Scholar]

- Corrosion inhibition of mild steel by 2-(2-methoxybenzylidene) hydrazine-1-carbothioamide in hydrochloric acid solution: experimental measurements and quantum chemical calculation. J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;30:112957

- [Google Scholar]

- XPS and DFT investigations of corrosion inhibition of substituted benzylidene Schiff bases on mild steel in hydrochloric acid. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2019;476:861-877.

- [Google Scholar]

- A pyrimidine derivative as a high efficiency inhibitor for the corrosion of CS in oilfield produced water under supercritical CO2 conditions. Corros. Sci.. 2020;164:108334-108352.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of thiophene derivatives on steel in sulphuric acid solutions. Corros. Sci.. 1973;13:557.

- [Google Scholar]

- The inhibition of benzimidazole derivatives on corrosion of iron in 1 M HCl solutions. Electrochim. Acta. 2003;48:2493-2503.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticorrosion performance of three newly synthesized isatin derivatives on CS in hydrochloric acid pickling environment: electrochemical, surface and theoretical studies. J. Mol. Liq.. 2017;246:302-316.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical and quantum chemical studies of new thiadiazole derivatives adsorption on mild steel in normal hydrochloric acid medium. Corros. Sci.. 2005;47:485-505.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of autoinducer-2 on corrosion of Q235 carbon steel caused by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Corros. Sci. 2022:110220.

- [Google Scholar]

- Computational, Monte Carlo simulation and experimental studies of some arylazotriazoles (AATR) and their copper complexes in corrosion inhibition process. J. Mol. Liq.. 2018;260:351-374.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetics of electrophile-nucleophile combinations: a general approach to polar organic reactivity. Pure Appl. Chem.. 2005;77:1807-1821.

- [Google Scholar]

- Double layer capacitance of iron and corrosion inhibition with polymethylene diamines. J. Electrochem. Soc.. 1991;119:146-154.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental and theoretical evaluation of the adsorption process of some polyphenols and their corrosion inhibitory properties on mild steel in acidic medi. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2021;9(6):106482

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, structure investigation and dyeing assessment of novel bisazo disperse dyes derived from 3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-ones for dyeing polyester fabrics. J. Korean Chem. Soc.. 2012;56(3):348-356.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, tautomeric structure, dyeing characteristics, and antimicrobial activity of novel4-(2-arylazophenyl)-3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-1-phenyl-2-pyrazolin-5-ones. J. Korean. Chem. Soc.. 2012;56(1):82-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- A facile synthesis, tautomeric structure of novel 4-arylhydrazono-3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-2-pyrazolin-5-ones and their application as disperse dyes. Color. Technol.. 2013;129(6):418-424.

- [Google Scholar]

- Corrosion protection of mild steel in 1M sulfuric acid solution using anionic surfactant. Mater. Chem. Phys.. 2004;85:273-279.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis, characterization and corrosion inhibition studies of N-phenyl-benzamides on the acidic corrosion of mild steel: experimental and computational studies. J. Mol. Liq.. 2018;251:317-332.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of mild steel corrosion in 1N sulphuric acid through indole. Wekst. Korros.. 1994;45:641-647.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition of mild steel corrosion by1,4,6 trimethyl-2-oxo-1,2-dihydropyridine-3-carbonitrile and synergistic effect of halide ion in 0.5 M H2SO4. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2016;380:141-150.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of H2O2/albumin and glucose on the biomedical iron alloys corrosion in simulated body fluid: experimental, surface, and computational investigation. J. Mol. Liq.. 2021;339:116823

- [Google Scholar]

- Theoretical investigation to corrosion inhibition efficiency of some chloroquine derivatives using density functional theory. Adv. J. Chem.-Sect. A. 2020;3(4):485-492.

- [Google Scholar]

- Luminescent coatings: White-color luminescence from a simple and single chromophore with high anti-corrosion efficiency. Dyes and Pigments. 2020;175:108146

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption and corrosion inhibition properties of 5-amino 1,3,4-thiadiazole-2- thiol on the mild steel in hydrochloric acid medium: thermodynamic, surface and electrochemical studies. J. Electroanal. Chem.. 2017;803:125-134.

- [Google Scholar]

- Organic sulphur-containing compounds as corrosion inhibitors for mild steel in acidic media: correlation between inhibition efficiency and chemical structure. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2004;236:155-164.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inhibition effects of some schiff's bases on the corrosion of mild steel in hydrochloric acid solution. Corros. Sci.. 2008;50:3356-3362.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metallic Corrosion Inhibitors. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1960.

- Self-assembled monolayers of schiff bases on copper surfaces. Corrosion. 2001;57:195-201.

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of the inhibition effect of indole-3-carboxylic acid on the copper corrosion in 0.5 M H2SO4. Corros. Sci.. 2008;50:3467-3474.

- [Google Scholar]

- Density functional theory and molecular dynamics simulation study on corrosion inhibition performance of mild steel by mercapto-quinoline Schiff base corrosion inhibitor. Phys. E Low- Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct.. 2015;66:332-341.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption and inhibition effect of tetraaza-tetradentate macrocycle ligand and its Ni (II), Cu (II) complexes on the corrosion of Cu10Ni alloy in 3.5% NaCl solutions. Colloids Surf. A. 2021;609:125653-125673.

- [Google Scholar]

- Myristic acid based imidazoline derivative as effective corrosion inhibitor for steel in 15% HCl medium. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2019;551:47-60.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thiourea and substituted thioureas as corrosion inhibitors for aluminium in sodium nitrite solution. Corros. Sci.. 1993;34:563-571.

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical and optical techniques for the study of metallic corrosion. Kluwer Academic, the Netherlands. 1991;545

- [Google Scholar]

- 5th European Symposium on Corrosion Inhibitors. Italy: Ferrara; 1980.

- Synergistic corrosion inhibition effects of quaternary ammonium salt cationic surfactants and thiourea on Q235 steel in sulfuric acid: experimental and theoretical research. Corros. Sci.. 2022;199:110199

- [Google Scholar]

- The performance and mechanism of bifunctional biocide sodium pyrithione against sulfate reducing bacteria in X80 carbon steel corrosion. Corros. Sci.. 2019;150:296-308.

- [Google Scholar]

- Molecular dynamics and density functional theory study on relationship between structure of imidazoline derivatives and inhibition performance. Corros. Sci.. 2008;50:2021-2029.

- [Google Scholar]

- Anticorrosive properties of N-acetylmethylpyridinium bromides. Russian J. Appl. Chem.. 2006;79:1100-1104.

- [Google Scholar]

- New 1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione derivatives as efficient organic inhibitors of CS corrosion in hydrochloric acid medium: electrochemical, XPS and DFT studies. Corros. Sci.. 2015;90:572-584.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gravimetric, electrochemical and surface studies on the anticorrosive properties of 1-(2-pyridyl)-2-thiourea and 2-(imidazol-2-yl)-pyridine for mild steel in hydrochloric acid. New J. Chem.. 2018;42:12649-12665.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aloe polysaccharide as an eco-friendly corrosion inhibitor for mild steel in simulated acidic oilfield water: experimental and theoretical approaches. J. Mol. Liq.. 2020;307:112950-211962.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104373.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1