Translate this page into:

Molecular-level investigation on removal mechanisms of aqueous hexavalent chromium by pine needle biochar

⁎Corresponding authors at: Key Laboratory of Groundwater Resources and Environment, Ministry of Education, Jilin University, Changchun 130021, China (YingYing Liu). yingyingl@jlu.edu.cn (YingYing Liu), leiyutao@scies.org (Yutao Lei)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University. Production and hosting by Elsevier.

Abstract

Pine needle biochar produced via oxygen-limited pyrolysis at 800 °C for 2 h was used for removing aqueous hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] from water. The optimality of the pseudo-second order kinetic model indicated the chemisorption dominated the removal process. Strong acid environment (pH = 2.0) was more conductive to Cr(VI) removal. The functional groups (C–O, O–C–O, C = O) on biochar contributed to Cr(VI) elimination from aqueous solution. The governing removal mechanisms involved electrostatic attraction, reduction, and complexation. Especially, confocal micro-X-ray fluorescence (μ-XRF) mapping indicated that Cr ions and functional groups were primarily distributed on the surface of biochar. This study firstly provided a deep interpretation of Cr speciation and spatial distribution on pine needle biochar, which provided important information on removal mechanisms of Cr(VI) by pine needle biochar.

Keywords

Cr(VI)

Biochar

Confocal micro-X-ray fluorescence mapping

X-ray absorption near-edge structure

Removal mechanisms

1 Introduction

Hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] contamination detected in electroplating, printing, leather tanning, and mining industries has been recognized as one of the main severe environmental issues (Lin et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2020a). Compared to trivalent chromium [Cr(III)], Cr(VI) poses more negative impacts on human health and ecosystem attributed to its higher toxicity, carcinogenicity, and bio-accumulation (Cheng et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2018a). Therefore, the efficient detoxification of Cr(VI) from water should be considered as a priority for environmental protection. Varieties of methods have been conducted for purifying Cr(VI)-polluted water, including adsorption, chemical precipitation, membrane separation, and ion exchange (Godlewska et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019). Among them, adsorption has been identified as the most convincing method on Cr(VI) elimination ascribed to its effectiveness, maneuverability, and low-cost (Zhang et al., 2019; Shi et al., 2020).

Biochar is defined as the cabonaceous solid which obtained from diverse feedstocks including agricultural residues, manure, and sewage sludge, etc. (Zhang et al., 2017; Awasthi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020) via thermal decomposition under anaerobic condition at temperatures varying from 300 to 800 °C (Palansooriya et al., 2019). Biochar, as an outstanding sorbent for Cr(VI) treatment, has arose much attention based on its cost-effectiveness, ease of operation, and sufficient capacity (Tan et al., 2015). The properties of biochar and its removal performances on contaminants are also significantly affected by pyrolysis temperature (Qin et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2022) and feedstocks (Ippolito et al., 2020). The high pyrolysis temperature can promote the formation of biochar with stable C compounds (Cantrell et al., 2012); wood-based feedstock contains more C and is favorable for high-yield biochar production (Zhao et al., 2017). Biochar derived from various wood-feedstocks have been served as restoration materials in Cr(VI) treatment and presented outstanding performances (Mohan et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2020b).

As a wood biomass, pine needle is abundant in lignocellulose, including lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose, which are conducive to the synthesis of biochar with higher carbon contents (Cantrell et al., 2012). Besides, pine needle is one major by-product of pine tree which usually considered as a common forestry waste. The environmental and efficient disposal of pine needle by means of biochar production has been regarded as a promising way for the achievement of waste to treasure as well as the promotion of waste rational utilization. Studies have used pine needle biochar as sorbent for removing Pb, As (Ahmad et al., 2016; Choudhary et al., 2020), trichloroethylene (Ahmad et al., 2013), nonpolar and polar aromatic contaminants (Chen et al., 2008), and as conductive material for methanogenesis promotion (Mohan and Annachhatre, 2022), while no study has been conducted for Cr(VI) removal.

Confocal micro-X-ray fluorescence (μ-XRF) mapping is superior in the elemental spatial distribution analysis, due to its higher precision with deep detection depth of 600 μm, and can be utilized for three-dimensional depth profile acquirement. Confocal μ-XRF mapping as a novel analytical technique has been used in a wide variety of applications including geology (Vekemans et al., 2004), environmental science (Liu et al., 2018), and biology (Tsuji et al., 2007). For example, Liu et al. (2019a) mapped the spatial distribution of Cr element on oak wood biochar, and found that Cr was mainly distributed on the surface of bulk sample. Perez et al. (2010) reported the confocal μ-XRF mapping of Cu and Zn on the aquatic macrophyte Spirodela polyrhiza L., the results confirmed the applicability of confocal μ-XRF mapping in bioremediation by aquatic plants. X-ray absorption near edge structure spectroscopy (XANES) is a valuable and precise tool for elemental speciation determination ascribed to its strong penetrability for inner analysis. There might be two pathways for Cr(VI) removal by biochar: (1) Cr(VI) is directly bound on the surface of biochar or reduced to Cr(III) by surface functional groups and further existed as the form of surface-Cr on biochar; (2) Cr(VI) is diffused into the internal pore structure and directly bound as Cr(VI) or reduced to Cr(III) by inner functional groups and further existed as the form of inner-Cr on biochar. The combination of confocal μ-XRF mapping and XANES analysis can provide information on the speciation and spatial distribution of Cr on biochar, which is helpful in gaining insights into the removal mechanisms and the effectiveness of biochar in environmental remediation and management. The result of Cr(VI) reduction to Cr(III) by biochar has been obtained to a great extent (Guo et al., 2020a; Li et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2022). However, rare study has focused on the speciation and spatial distribution of the reacted-Cr on pine needle biochar.

In this work, biochar derived from pine needles was prepared and used to remove Cr(VI) from water. The removal kinetics, effects of solution pH and initial Cr(VI) concentration were systematically investigated and discussed. Furthermore, Cr(VI) removal mechanism and the potential stability of pine needle biochar were revealed through the combination of various techniques including Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method, SEM, Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), confocal μ-XRF mapping, and XANES. These observations will provide a new insight into the potential application of pine needle biochar on Cr(VI) removal.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

The precursors of biochar were obtained from a university campus of Changchun, Jilin, China, washed using ultra-pure water to remove the dust, dried at 80 °C, and finally cut to < 2 mm before pyrolysis. In addition to the superior nitric acid (HNO3) (65–68%, 16 M) obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., other reagents of analytical grade, including sodium hydroxide (NaOH), potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7), and calcium carbonate (CaCO3), were purchased from Beijing Reagent Co., Ltd..

2.2 Biochar preparation

Dried pine needles sticks were placed in a tube furnace, heated to the desired temperature of 800 °C, and carbonized for 2 h under N2 stream (heating rate: 10 °C min−1). The pine needle biochar was passed through the mesh sieves to obtain a size of 0.5–2 mm, then was rinsed three times using ultra-pure water and vacuum dried.

2.3 Cr(VI) removal experiments

Saturated CaCO3 ultra-pure water (pH = 8.1) was prepared as a background solution following Liu et al. (2020b). Concentrated HNO3 and 0.2 mol L−1 NaOH were utilized for adjusting solution pH. For Cr(VI) removal kinetic experiments, 50 mg L−1 Cr(VI) was exposed to 10 g L−1 biochar under pH of 2.0 and sampled at specific time intervals of 0.5, 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, 72, 120, and 168 h. The influencing factors analysis were conducted by varying the solution pH values from 2.0 to 8.1 and initial Cr(VI) concentrations from 1 to 600 mg L−1, respectively, with a consistent biochar dosage of 10 g L−1 and sampling time of 168 h. The 50 mL centrifuge tubes with 40 mL suspensions were shaken at room temperature. At each sampling time, biochar was separated from the supernatant using 0.22-μm membrane filters. For further characterization of biochar, the recovered solid was washed three times and vacuum-dried. The total amount of Cr and Cr(VI) were quantified via atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS) (6000CF, Shimadzu, Japan) and DR3900 spectrophotometer (Hach, USA), respectively. All experiments were conducted duplicated.

Cr removal percentage (R, %) was determined by employing Eq. (1):

in which, C0 presents the initial Cr(VI) concentration at time 0 (mg L−1), Ct is the Cr(VI) concentration at time t (mg L−1). The removal capacity of biochar (q, mg g−1) was determined by Eq. (2):

in which, v and m relate to the volume of reaction system (L) and mass of pine needle biochar (g), respectively.

2.4 Kinetic models

A better understanding of the kinetic data is conductive for a clearer explanation of the removal mechanism. Pseudo-first order (PFO), pseudo-second order (PSO), intra-particle diffusion (IPD), Elovich, and modified Freundlich models were utilized and the details of these five models were expressed as follows:

The PFO model (Guo et al., 2020a):

The PSO model (Guo et al., 2020a):

The IPD model (Zhang et al., 2018c):

The modified Freundlich model (Liu et al., 2020b):

The Elovich model (Liu et al., 2020b):

where qe and qt (mg/g) denote the treated Cr(VI) mass per unit mass of biochar at equilibrium and time t (h), respectively; k1 (L h−1), k2 (g mg−1h−1), k3 (mg g−1h−1/2) and k4 (L g−1h−1) are the rate constants of PFO, PSO, IPD, and the modified Freundlich models, respectively; α (mg g−1h−1) and β (g mg−1) are the Elovich constants; m is the modified Freundlich constant.

2.5 Characterization

Surface morphology was characterized by JSM-5600 SEM (JEOL, Japan), and the energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) spectra was utilized as an auxiliary tool and collected for the elemental varieties and content identification. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) spectrometer (Nicolet iS5, Thermo Fisher, USA) was conducted for the varieties of biochar surface functional groups determination. A BET analyzer (ASAP 2020, Micromeritics, USA) was carried out to obtain the surface area, pore volume, and pore size of biochar and Cr(VI)-biochar. The elemental compositions and speciation analysis were achieved via an ESCALAB 250 Al K-ɑ spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). The determination of the zeta potential of biochar was determined by Malvern zeta potential analyzer.

2.6 Confocal μ-XRF mapping analysis

Confocal μ-XRF mapping was utilized to provide the fine structures of biochar and Ca, K, and Cr distribution which can offer the evidence for the potential application of biochar. The measurement was performed at Sector 20-ID at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) of Argonne National Laboratory (ANL) in the USA. The confocal μ-XRF mapping data was obtained and corrected according to the methods described by Liu et al. (2017). Shortly, the mapping was conducted at the incident beam energy of 7.6 keV and the beam size of 2 × 2 μm2. The completion of the confocal geometry was achieved by installing an optic in front of the detector.

2.7 Cr XANES

The reacted biochar particles were analyzed using XANES method for Cr speciation determination. The Cr K-edge XANES spectra were recorded at sector 20-BM of ANL. Reference materials including K2Cr2O7 and Cr(OH)3 were introduced to distinguish the existing form of Cr on biochar. ATHENA software was utilized for the collected data standardization (Ravel and Newville, 2005). The first derivative smooth spectra were obtained after linear combination fitting (LCF) and the Cr speciation was determined through comparing with the reference spectra.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Cr(VI) removal experiments

3.1.1 Kinetic study

The kinetic study was performed to evaluate the performance of pine needle biochar for Cr(VI) removal (Fig. 1). In the first 12 h, total Cr and Cr(VI) concentration rapidly decreased with increasing of Cr(III), which was attributed to the availability of the unoccupied active sites of biochar (Aljeboree et al., 2017). The removal rate slowed down with the reaction time, ascribing to the consumption of biochar binding active sites in the initial stage. After the equilibrium (t = 168 h), 83.6% of Cr(VI) was removed and 50% of the aqueous Cr existed as Cr(III), illustrating the conversion of Cr(VI) to less toxic Cr(III) by pine needle biochar.![Variations of Cr concentration as a function of time [initial Cr(VI) concentration = 50 mg L−1, pH = 2.0, dosage = 10 g L−1].](/content/184/2023/16/8/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2023.104966-fig1.png)

Variations of Cr concentration as a function of time [initial Cr(VI) concentration = 50 mg L−1, pH = 2.0, dosage = 10 g L−1].

The plots and kinetic parameters of five kinetic models for Cr(VI) removal were depicted in Fig. 2 and Table 1, respectively. The PSO mode was preferable to simulate the kinetic data than the other four models in terms of the greatest corresponding meter (R2) of 0.999. Besides, the obtained removal capacity of 4.21 mg g−1 from PSO model was also consistent with the theoretical removal capacity of 4.18 mg g−1, indicating the removal mechanism of Cr(VI) by pine needle biochar dominantly was chemical sorption between Cr(VI) ions and active sites of biochar (Shi et al., 2013). The optimality of PSO model for Cr(VI) treatment was also observed in other studies (Miretzky and Cirelli, 2010). The Elovich model possessed a larger α value (39.28) and a smaller β value (2.364) was also appropriate for Cr(VI) removal representation (R2 = 0.964), which demonstrated the heterogenous surface of biochar and the occurrence of electron transfer between biochar and Cr(VI) ions (Aljeboree et al., 2017). For intra particle diffusion model, three rate-limiting stages were depicted in Fig. 2c, including external mass transfer (the first stage), intra particle diffusion (the second stage), and internal surface adsorption (the third stage) (Guo et al., 2020b). Besides, the intercepts of these lines were greater than 1.5 mg g−1 instead of zero, providing the key insights that the intra particle diffusion was not the only rate-limiting phase (Li et al., 2015).![Kinetic study of Cr(VI) removal based on (a) PFO model, (b) PSO model, (c) IPD model, (d) modified Freundlich model, and (e) Elovich model [initial Cr(VI) concentration = 50 mg L−1, pH = 2.0, dosage of biochar = 10 g L−1].](/content/184/2023/16/8/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2023.104966-fig2.png)

Kinetic study of Cr(VI) removal based on (a) PFO model, (b) PSO model, (c) IPD model, (d) modified Freundlich model, and (e) Elovich model [initial Cr(VI) concentration = 50 mg L−1, pH = 2.0, dosage of biochar = 10 g L−1].

Models

Parameters

R2

PFO model

k (L h−1)

0.990

0.0236

PSO model

k (g mg−1h−1)

0.998

0.0591

IPD model

k (mg g−1h−1/2)

0.999

0.0155

Modified Freundlich model

k (L g−1h−1)

m

0.989

0.0395

6.806

Elovich model

α (mg g−1h−1)

β (g mg−1)

0.964

39.28

2.364

The comparisons of Cr(VI) removal capacity of pine needle biochar with several other reported biochar were showed in Table 2: 3.40 mg g−1 for oak bark biochar (Mohan et al., 2011), 4.10 mg g−1 for oak wood biochar (Mohan et al., 2011), 2.00 mg g−1 for Melia azedarach wood biochar (Zhang et al., 2018c), 3.53 mg g−1 for oily seeds of Pistacia terebinthus L. biochar (Deveci and Kar, 2013), and 3.90 mg g−1 for landfill leachate sludge biochar (Li et al., 2022). By contrast, the pine needle biochar prepared in this study exhibited better performance than other reported biochars.

Materials

Initial Cr(VI)

(mg L−1)Dosage

(g L−1)Removal capacity

(mg g−1)Refs

Oak bark biochar

60

10.0

3.40

(Mohan et al., 2011)

Oak wood biochar

60

10.0

4.10

(Mohan et al., 2011)

Melia azedarach wood biochar

10

5.0

2.00

(Zhang et al., 2018c)

Oily seeds of Pistacia terebinthus L. biochar

25

2.0

3.53

(Deveci and Kar, 2013)

Landfill leachate sludge biochar

50

10.0

∼3.90

(Li et al., 2022)

Pine needle biochar

50

10.0

4.18

This study

3.1.2 Effect of pH

As depicted in Fig. 3a, the solution pH notably influenced removal capacity of pine needle biochar. Cr(VI) removal efficiency sharply decreased with increasing pH from 2.0 to 8.1. pH of 2.0 appeared to be the optimal pH for Cr(VI) removal. This phenomenon could be ascribed to the high dependence of aqueous Cr(VI) species and biochar surface charge on solution pH (Guo et al., 2018). As pH below 2.0, Cr(VI) existed in the forms of HCrO4− and Cr2O72− (Huang et al., 2016). The zeta potential of pine needle biochar was 3.83 (Fig. 3b), indicating that biochar surface was positively charged at pH below 3.83, and therefore, it was preferred to attract negative Cr(VI) ions. While at higher pH, biochar possessed negative charge and the resulting electrostatic repulsion would cause the low affinity of Cr(VI) to biochar. In addition, strong acidic condition was testified to be favorable for Cr(VI) reduction (Zhang et al., 2018b; Liu et al., 2020b). The exhibition of neglectable performance of biochar on Cr(VI) removal under high pH conditions coincided with previous studies (Zhou et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2020b).![(a) Effect of pH on Cr(VI) removal [initial Cr(VI) concentration = 50 mg L−1, dosage of biochar = 10 g L−1, time = 168 h] and (b) zeta potential of pine needle biochar.](/content/184/2023/16/8/img/10.1016_j.arabjc.2023.104966-fig3.png)

(a) Effect of pH on Cr(VI) removal [initial Cr(VI) concentration = 50 mg L−1, dosage of biochar = 10 g L−1, time = 168 h] and (b) zeta potential of pine needle biochar.

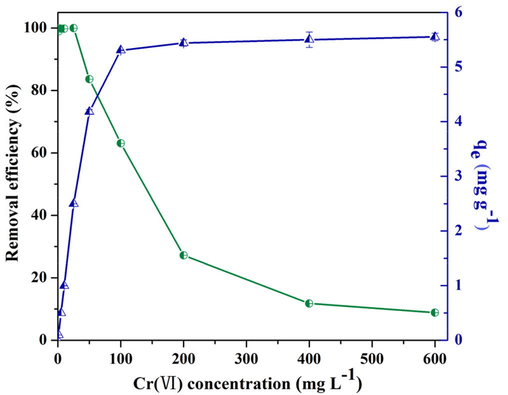

3.1.3 Effect of initial Cr(VI) concentration

Cr(VI) concentration is varied in different environment; therefore, initial Cr(VI) concentration is a decisive factor on Cr(VI) removal. As initial Cr(VI) concentration < 25 mg L−1, the removal efficiency of Cr(VI) was 99.9% (Fig. 4). This could be attributed to the adequate active sites of biochar for Cr(VI) with relatively low concentration elimination from solution. The occupation of the available active sites resulted in the sharp decrease in removal efficiency at higher initial Cr(VI) concentrations. In contrast, accompanying with the enhancement of the initial Cr(VI) concentration from 0 to 100 mg L−1, Cr(VI) removal capacity of biochar increased. This phenomenon might be attributed to the fact that the higher Cr(VI) concentration, the stronger driving force between Cr(VI) and biochar, which was conductive for Cr(VI) transferring to pine needle biochar (Albadarin et al., 2011; Shakya and Agarwal, 2019).

Variations of Cr(VI) removal efficiency and pine needle biochar capacity as a function of Cr(VI) concentration (pH = 2.0, time = 168 h, dosage of biochar = 10 g L−1).

3.2 BET analysis

As presented in Table 3, the specific surface area and pore characteristics of pine needle biochar varied after Cr(VI) elimination from aqueous solution. The decreases in the specific surface area (28.84 m2 g−1), pore volume (0.003 m3 g−1), and pore size (0.04 nm) were observed compared to the raw biochar, which could be ascribed to the blockage of biochar pores by Cr.

Specific surface area

(m2 g−1)Pore volume

(m3 g−1)Pore size

(nm)

Before the reaction

53.03

0.022

2.27

After the reaction

24.91

0.019

2.23

3.3 FTIR analysis

The comparison of FTIR spectra of unloaded and Cr(VI)-loaded biochar was depicted in Fig. S1. The biochar exhibited abundant functional groups including C = C, −OH, C−H, C = O, and C−O group. After Cr(VI) elimination, these functional groups varied a lot. In detail, the intensities of C−H stretching vibration at 2920 cm−1 (Mohammed et al., 2018) and 2851 cm−1 (Wang et al., 2017) increased, the biochar peak at 1075 cm−1 according to C−O became sharp and exhibited a right shift to 1050 cm−1 (Meng et al., 2013), with the enhancement of C = C or C = O band at 1636 cm−1 (Li et al., 2016a). The loss of C−O group and the generation of C = O could be ascribed to the occurrence of the oxidation–reduction process between C−O group and Cr(VI) ions (Shakya and Agarwal, 2019). The C = O group was also verified to be responsible for Cr(III) stabilization (Liu et al., 2020b). Overall, the FTIR results verified that Cr(VI) removal by pine needle biochar was primarily caused by the participation of functional groups.

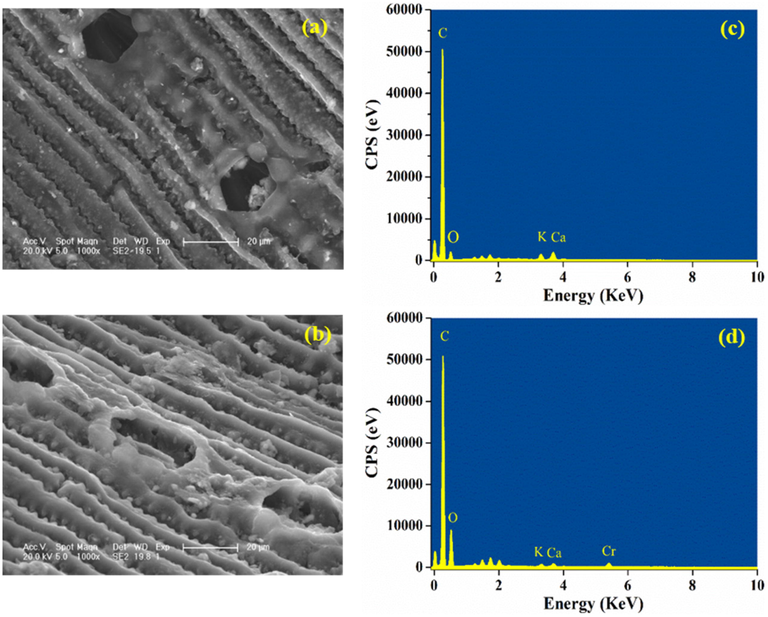

3.4 SEM/EDS analysis

The performance of biochar was also affected by its surface properties. From Fig. 5a, biochar exhibited structured and smooth surfaces with a few relatively large pores. However, for Cr-reacted biochar (Fig. 5b), the surface became rough and the pores were filled with irregular tiny particles which were supposed to be the fixed Cr. The distinguishment in the elemental composition between unreacted and Cr-reacted biochar was depicted in Fig. 5c and 5d. The appearance of an obvious Cr peak was observed in EDS spectra of Cr-reacted biochar, illustrating the combination of Cr with biochar after the reaction.

SEM images and EDS spectra of pine needle biochar before (a, c) and after Cr(VI) removal (b, d).

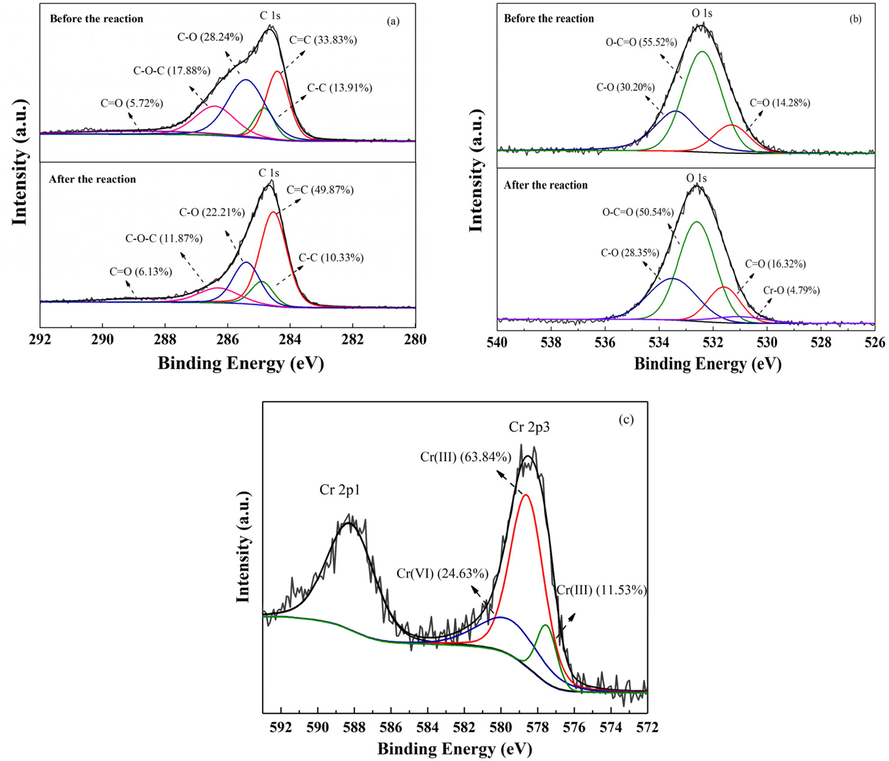

3.5 XPS analysis

The variations in the functional groups of biochar, species and contents of Cr after the reaction were recorded in XPS spectra (Fig. 6). The C 1 s and O 1 s spectra further confirmed the existence of abundant functional groups on biochar, which coincided with the FTIR results. As depicted in Fig. 6a, the C 1 s spectra were deconvoluted into five peaks at 284.0, 284.4, 285.4, 286.2, and 288.1 eV corresponding to C = C (Yang et al., 2010), C–C (Goswami et al., 2020), C–O (Liu et al., 2013), C–O–C (Xiao et al., 2021), and C = O (Chen et al., 2018) group, respectively. After Cr elimination, the proportion of C–O and C–O–C in pine needle biochar reduced from 28.24% and 17.88% to 22.21% and 11.87%, respectively, whereas the C = O group intensity increased. For O 1 s spectra (Fig. 6b), the variations of oxygen-containing functional groups were consistent with that of carbon-based functional groups. The C–O at 533.5 eV (Parayil et al., 2015) and O–C = O at 532.5 eV (Kim et al., 2019) declined 1.85% and 4.98%, respectively with the generation of 2.04% in C = O group at 531.4 eV (Peng et al., 2019). These phenomena further confirmed the reduction ability of biochar on Cr(VI) removal, which mainly depended on the reducing functional groups (C–O, C–O–C, O–C = O). Besides, peak representing Cr–O group (531.0 eV) in Cr2O3 (Seal et al., 2002) or Cr(OH)3 (Surviliene et al., 2015) was depicted in the reacted-biochar, illustrating Cr(III) was formed through reduction reaction and then bound on biochar through complexation with C = O groups. From Cr 2p spectra (Fig. 6c), the peaks representing Cr(VI) at 579.2 eV (Li et al., 2016b) and Cr(III) at 578.5 eV (Molodkina et al., 2020) and 577.5 eV (Shee and Sayari, 2010) were observed simultaneously, and only 24.63% of the combined Cr existed in the form of Cr(VI). This result further elucidated the reduction and stabilization roles of biochar for Cr contaminant removal.

XPS of (a) C 1 s, (b) O 1 s, and (c) Cr 2p spectra for pine needle biochar.

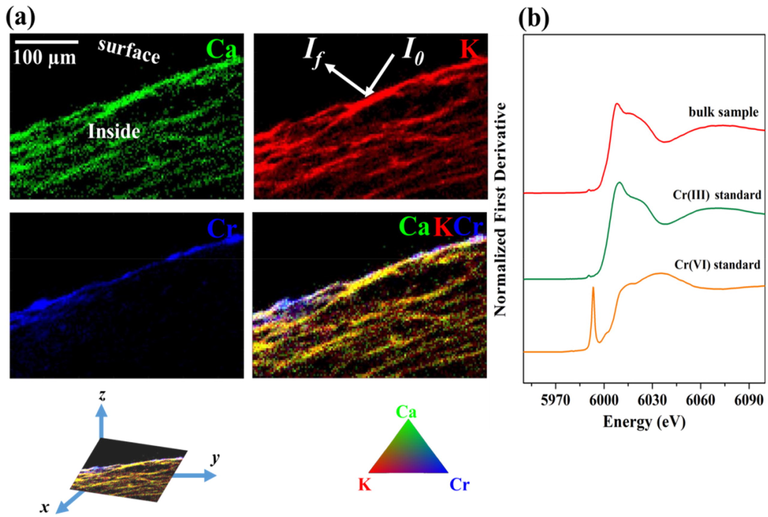

3.6 Confocal μ-XRF mapping and XANES analysis

The spatial distributions of elements Ca (green), K (red), and Cr (blue) were depicted in Fig. 7a. Ca and K, the common source materials of biochar, were utilized as reference elements for pine needle biochar structure and properties identification. In the confocal μ-XRF mapping of Ca and K elements, neatly structured biochar with low porosity was observed (Fig. 7a). In the confocal μ-XRF mapping of Cr element (Fig. 7a), different from the apple wood biochar we studied before (Liu et al., 2020b), Cr was unevenly distributed on the biochar and primarily near the edge of pine needle biochar, indicating that the functional groups of pine needle biochar were mainly existed in the form of surface-functional groups and played a key role in Cr stabilization. XANES data collected at the Cr K-edge spectra were shown in Fig. 7b. Compared with the reference compounds, weak Cr(VI) peak and intense Cr(III) peak were both observed in Cr XANES spectra of the reacted-biochar, indicating the coexistence of Cr(VI) and Cr(III) on biochar with a higher content of Cr(III). This fact was further proved by the LCF results (Table 4) with accurate contents of Cr(VI) (76.6%) and Cr(III) (23.4%). The combined results of confocal μ-XRF mapping and XANES illustrated that Cr(VI) was primarily removed through reduction and immobilization by biochar.

(a) Confocal μ-XRF mapping of Ca (green), K (red), and Cr (blue) distribution on the reacted-biochar and (b) Cr K-edge XANES spectra of Cr-loaded biochar.

Percentage (%)

R-factor

Reduced x2

Cr(VI)

Cr(III)

Cr(VI)-reacted biochar

23.4

76.6

0.0456

0.018

3.7 Integration of removal mechanism

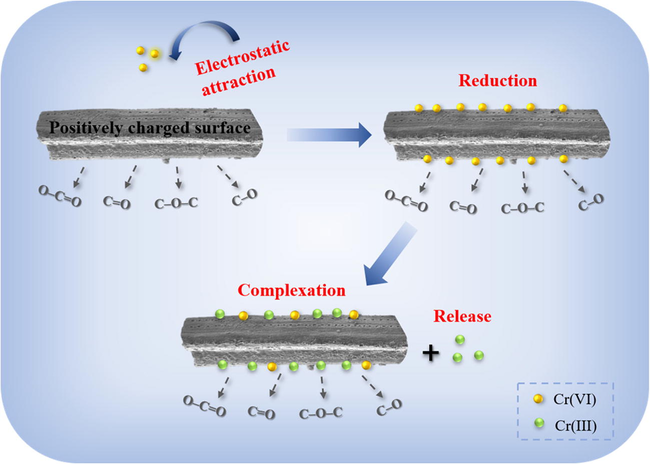

The observation of aqueous Cr(III) and the best fitting of PSO model indicated the occurrence of Cr(VI) reduction to Cr(III). The results from FTIR and XPS analysis demonstrated the critical role of functional groups on Cr(VI) reduction and Cr(III) complexation. The XPS and XANES spectra showed that Cr(VI) and Cr(III) were coexisted on biochar, and ∼ 76% of Cr was presented in the form of Cr(III). The confocal μ-XRF mapping revealed the distribution of Cr on biochar surface. Based on the kinetic studies and solid characterization analysis, the mechanism of Cr(VI) treatment by biochar was proposed. As shown in Fig. 8, firstly, in an acid environment, aqueous Cr(VI) was attracted to the protonated biochar surface under the electrostatic attraction (Guo et al., 2020a). Then, the reducing process of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) occurred, where the surface functional groups (C–O and C–O–C, and O–C = O) served as the electron donors (Choudhary et al., 2017). Finally, large proportion of Cr(III) was stabilized on biochar by complexation with C = O group, and the remainder was re-released into the solution (Zheng et al., 2021).

The proposed removal mechanisms of Cr(VI) by pine needle biochar.

4 Conclusions

This investigation utilized the waste pine needle as precursor for biochar preparation and evaluated the performance of pine needle biochar on Cr(VI) removal. Pine needle biochar exhibited a satisfactory performance to remove Cr(VI) with concentrations < 25 mg L−1. The suitability of PSO and IPD kinetic models indicated that Cr(VI) elimination from aqueous solution was predominantly controlled by chemisorption. The increasing pH was unfavorable to Cr(VI) removal and the optimal treatment was achieved at pH of 2.0. The pine needle biochar can be applied in acid Cr(VI)-containing wastewater treatment. After the pH of groundwater is adjusted to 2.0 following with extraction, the pine needle biochar is also suitable for ex-situ remediation of Cr(VI) contaminated groundwater. FTIR and XPS techniques demonstrated the key role of functional groups (C–O, C–O–C, and C = O) of pine needle biochar on Cr(VI) removal. The results from liquid phase and solid phase analysis indicated the removal process was combined by electrostatic attraction, Cr(VI) reduction, and Cr(III) complexation with C = O group. Confocal μ-XRF mapping revealed that Cr and functional groups of biochar were distributed primarily on the surface of biochar. This technique provided the crucial information that we can optimize pore structure and inner functional groups of pine needle biochar for developing new pine needle biochar-based materials with improved performance on Cr(VI) removal. Confocal μ-XRF mapping can also be conducted to identify the spatial distribution of Fe element in Fe-modified biochar or S element in S-modified biochar, which can provide insights into the extent and mechanisms of the modified processes. This study provided a deep understanding on the potential application of pine needle biochar, as well as the guidance for optimization of pine needle biochar properties.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuting Zhang: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Na Liu: Funding acquisition. Peng Liu: . YingYing Liu: Writing – review & editing. Yutao Lei: Supervision, Project administration.

Acknowledgement

This study was financially supported by the Science and Technology Project of Jilin Provincial Education Department (Grant Number JJKH20220295KJ and JJKH20210272KJ) and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Jilin Province (Grant Number 20220508008RC). Confocal μ-XRF mapping and XANES techniques were conducted at Beamline Sector 20-ID and 20-BM, respectively at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, Chicago, USA.

Ethics approval

This work does not contain any research involving humans or animals.

Consent to participate

The work described has not been published before; that it is not under consideration for publication anywhere else; that written informed consent was obtained from individual or guardian participants.

Consent to Publish

The publishment consent was obtained from all co-authors.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Science and Technology Project of Jilin Provincial Education Department (Grant Number JJKH20220295KJ and JJKH20210272KJ) and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Jilin Province (Grant Number 20220508008RC).

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Trichloroethylene adsorption by pine needle biochars produced at various pyrolysis temperatures. Bioresour. Technol.. 2013;143:615-622.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of soybean stover- and pine needle-derived biochars on Pb and As mobility, microbial community, and carbon stability in a contaminated agricultural soil. J. Environ. Manage.. 2016;166:131-139.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biosorption of toxic chromium from aqueous phase by lignin: mechanism, effect of other metal ions and salts. Chem. Eng. J.. 2011;169:20-30.

- [Google Scholar]

- Kinetics and equilibrium study for the adsorption of textile dyes on coconut shell activated carbon. Arabian J. Chem.. 2017;10:S3381-S3393.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emerging applications of biochar: Improving pig manure composting and attenuation of heavy metal mobility in mature compost. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2020;389:122116

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of pyrolysis temperature and manure source on physicochemical characteristics of biochar. Bioresour. Technol.. 2012;107:419-428.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of octadecylamine functionalized multi-wall carbon nanotubes on the conductive and mechanical properties of ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene. J. Polym. Res.. 2018;25:135.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transitional adsorption and partition of nonpolar and polar aromatic contaminants by biochars of pine needles with different pyrolytic temperatures. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2008;42:5137-5143.

- [Google Scholar]

- Bioremediation of Cr(VI) and Immobilization as Cr(III) by Ochrobactrum anthropi. Environ. Sci. Technol.. 2010;44:6357-6363.

- [Google Scholar]

- Batch and continuous fixed-bed lead removal using himalayan pine needle biochar: Isotherm and kinetic studies. ACS Omega. 2020;5:16366-16378.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of hexavalent chromium upon interaction with biochar under acidic conditions: mechanistic insights and application. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int.. 2017;24:16786-16797.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solutions by bio-chars obtained during biomass pyrolysis. J. Ind. Eng. Chem.. 2013;19:190-196.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biochar for composting improvement and contaminants reduction. A review. Bioresour. Technol.. 2017;246:193-202.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biological treatment of biomass gasification wastewater using hydrocarbonoclastic bacterium Rhodococcus opacus in an up-flow packed bed bioreactor with a novel waste-derived nano-biochar based bio-support material. J. Cleaner Prod.. 2020;256

- [Google Scholar]

- Camellia oleifera seed shell carbon as an efficient renewable bio-adsorbent for the adsorption removal of hexavalent chromium and methylene blue from aqueous solution. J. Mol. Liq.. 2018;249:629-636.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solution by mesoporous α-FeOOH nanoparticles: Performance and mechanism. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020;299

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption mechanism of hexavalent chromium on biochar: Kinetic, thermodynamic, and characterization studies. ACS Omega. 2020;5:27323-27331.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effective removal of Cr(VI) using β-cyclodextrin–chitosan modified biochars with adsorption/reduction bifuctional roles. RSC Adv.. 2016;6:94-104.

- [Google Scholar]

- Feedstock choice, pyrolysis temperature and type influence biochar characteristics: a comprehensive meta-data analysis review. Biochar. 2020;2:421-438.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effects of ozonized carbon black on fracture and post-cracking toughness of carbon fiber-reinforced epoxy composites. Compos. B. 2019;177

- [Google Scholar]

- Nanoscale zerovalent iron decorated on graphene nanosheets for Cr(VI) removal from aqueous solution: Surface corrosion retard induced the enhanced performance. Chem. Eng. J.. 2016;288:789-797.

- [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., Chen, X., Liu, L., Liu, P., Zhou, Z., Huhetaoli, Wu, Y., Lei, T., 2022. Characteristics and adsorption of Cr(VI) of biochar pyrolyzed from landfill leachate sludge. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 162.

- Preparation and characterization of biochars from Eichornia crassipes for cadmium removal in aqueous solutions. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148132-e148209.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surface-functionalized porous lignin for fast and efficient lead removal from aqueous solution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces.. 2015;7:15000-15009.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel materials for Cr(VI) adsorption by magnetic titanium nanotubes coated phosphorene. J. Mol. Liq.. 2019;287:110826

- [Google Scholar]

- Insight into pH dependent Cr(VI) removal with magnetic Fe3S4. Chem. Eng. J.. 2019;359:564-571.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal and reduction of Cr(Ⅵ) in simulated wastewater using magnetic biochar prepared by co-pyrolysis of nano-zero-valent iron and sewage sludge. J. Cleaner Prod.. 2020;257

- [Google Scholar]

- A beam path-based method for attenuation correction of confocal micro-X-ray fluorescence imaging data. J. Anal. At. Spectrom.. 2017;32:1582-1589.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of mercury stabilization mechanisms by sulfurized biochars determined using X-ray absorption spectroscopy. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2018;347:114-122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile synthesis of highly efficient and recyclable magnetic solid acid from biomass waste. Sci. Rep.. 2013;3:2419.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal mechanisms of aqueous Cr(VI) using apple wood biochar: a spectroscopic study. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2020;384:121371

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of pyrolysis temperature on characteristics and Cr(VI) adsorption performance of carbonaceous nanofibers derived from bacterial cellulose. Chemosphere. 2022;291:132976

- [Google Scholar]

- Quantitative and kinetic TG-FTIR investigation on three kinds of biomass pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis. 2013;104:28-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cr(VI) and Cr(III) removal from aqueous solution by raw and modified lignocellulosic materials: A review. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2010;180:1-19.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenol adsorption on biochar prepared from the pine fruit shells: Equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamics studies. J. Environ. Manage.. 2018;226:377-385.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facilitation of interspecies electron transfer in anaerobic processes through pine needle biochar. Water Sci. Technol.. 2022;86:2197-2212.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, D., Rajput, S., Singh, V.K., Steele, P.H., Jr, C.U.P., 2011. Modeling and evaluation of chromium remediation from water using low cost biochar, a green adsorbent. J. Hazard. Mater. 188, 319-333.

- Electrodeposition of chromium on single-crystal electrodes from solutions of Cr(II) and Cr(III) salts in ionic liquids. J. Electroanal. Chem.. 2020;860:113892

- [Google Scholar]

- Impacts of biochar application on upland agriculture: A review. J. Environ. Manage.. 2019;234:52-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- Photocatalytic conversion of CO2 to hydrocarbon fuel using carbon and nitrogen co-doped sodium titanate nanotubes. Appl. Catal. A. 2015;498:205-213.

- [Google Scholar]

- Catalyst-free synthesis of triazine-based porous organic polymers for Hg2+ adsorptive removal from aqueous solution. Chem. Eng. J.. 2019;371:260-266.

- [Google Scholar]

- Latest developments and opportunities for 3D analysis of biological samples by confocal μ-XRF. Radiat. Phys. Chem.. 2010;79:195-200.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biochar-driven reduction of As(V) and Cr(VI): Effects of pyrolysis temperature and low-molecular-weight organic acids. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf.. 2020;201:110873

- [Google Scholar]

- ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat.. 2005;12:537-541.

- [Google Scholar]

- Surface chemistry of oxide scale on IN-738LC superalloy: Effect of long-term exposure in air at 1173 K. Oxid. Met.. 2002;57:297-322.

- [Google Scholar]

- Shakya, A., Agarwal, T., 2019. Removal of Cr(VI) from water using pineapple peel derived biochars: Adsorption potential and re-usability assessment. J. Mol. Liq. 293.

- Light alkane dehydrogenation over mesoporous Cr2O3/Al2O3 catalysts. Appl. Catal. A. 2010;389:155-164.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of soy isoflavones by activated carbon: Kinetics, thermodynamics and influence of soy oligosaccharides. Chem. Eng. J.. 2013;215–216:113-121.

- [Google Scholar]

- High-efficiency removal of Cr(VI) by modified biochar derived from glue residue. J. Cleaner Prod.. 2020;254

- [Google Scholar]

- Annealing effect on the structural and optical properties of black chromium electrodeposited from the Cr(III) bath. Chemija. 2015;26:244-253.

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of biochar for the removal of pollutants from aqueous solutions. Chemosphere. 2015;125:70-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Development of confocal micro X-ray fluorescence instrument using two X-ray beams. Spectrochimi. Acta, Part B. 2007;62:549-553.

- [Google Scholar]

- Processing of three-dimensional microscopic X-ray fluorescence data. J. Anal. At. Spectrom.. 2004;19

- [Google Scholar]

- Black liquor as biomass feedstock to prepare zero-valent iron embedded biochar with red mud for Cr(VI) removal: Mechanisms insights and engineering practicality. Bioresour. Technol.. 2020;311:123553

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption removal of 17beta-Estradiol from water by rice straw-derived biochar with special attention to pyrolysis temperature and background chemistry. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14

- [Google Scholar]

- Developing WO3 as high-performance anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Lett.. 2021;285:129129

- [Google Scholar]

- Functionalization of carbon nanotubes with biodegradable supramolecular polypseudorotaxanes from grafted-poly(ε-caprolactone) and α-cyclodextrins. Eur. Polym. J.. 2010;46:145-155.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of feedstock and pyrolysis temperature on properties of biochar governing end use efficacy. Biomass Bioenergy. 2017;105:136-146.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption-reduction removal of Cr(VI) by tobacco petiole pyrolytic biochar: Batch experiment, kinetic and mechanism studies. Bioresour. Technol.. 2018;268:149-157.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of aqueous Cr(VI) by a magnetic biochar derived from Melia azedarach wood. Bioresour. Technol.. 2018;256:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hybrid functionalized chitosan-Al2O3@SiO2 composite for enhanced Cr(VI) adsorption. Chemosphere. 2018;203:188-198.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multicavity triethylenetetramine-chitosan/alginate composite beads for enhanced Cr(VI) removal. J. Cleaner Prod.. 2019;231:733-745.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of temperature on the structural and physicochemical properties of biochar with apple tree branches as feedstock material. Energ.. 2017;10

- [Google Scholar]

- Application of biochars in the remediation of chromium contamination: Fabrication, mechanisms, and interfering species. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2021;407:124376

- [Google Scholar]

- Investigation of the adsorption-reduction mechanisms of hexavalent chromium by ramie biochars of different pyrolytic temperatures. Bioresour. Technol.. 2016;218:351-359.

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104966.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1