Translate this page into:

High performance biobased poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) nanocomposites for food and cosmetics packaging materials: PMDA chain extended and TiO2 NPs functionalized

⁎Corresponding authors. yzhang@dlut.edu.cn (Ying Zhang), jiangmin@dicp.ac.cn (Min Jiang), gyzhou@dicp.ac.cn (Guangyuan Zhou)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

Abstract

Abstract

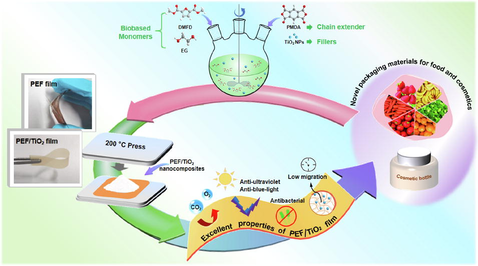

Poly (ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) (PEF) has attracted more attention due to its excellent properties and great potential to be the substitute of the petroleum-based polyethylene terephthalate (PET). However, the improvement of toughness and functionality from nano materials were limited. Here, we prepared novel PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites from dimethyl 2,5-furandicarboxylate (DMFD), ethylene glycol (EG), pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA) and TiO2 nanoparticles via one-pot polycondensation. The optimized PMDA (5‰ mol/mol of DMFD), TiO2 (60 nm, 0.5-10‰ wt./wt. of PEF) or TiO2 (30 nm or 100 nm, 3‰) served as extender, fillers, and comparison, respectively. The Tgs (∼88 °C) and the thermal stability of all nanocomposites were higher than pure PEF. The crystallization rate of the nanocomposites (60 nm-TiO2, 3‰) was improved mostly, and its half-crystallization time (t1/2) decreased to 6.16 min at 160 °C. The impact strength of nanocomposites (60 nm-TiO2, 10‰) could reach to 52.2 × 103 J/m2. Interestingly, the ultraviolet and blue-light shielding of PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites increased from 45.4% to 93.5% and 21.5% to 74.3%, respectively. The antibacterial activity of nanocomposites against E. coli also increased to 83%. The maximum migration of Ti during 35 d was 1.82 µg/g (FDA and EU guidance level are 10 µg/g). PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites shown great potential in industrial production and application.

Keywords

Poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) (PEF)

Polymer chain extension

PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites

Anti-ultraviolet functions

Anti-blue-light functions

Antibacterial functions

1 Introduction

In regard to the rapid consumption of fossil fuels, exploring biobased materials presented a possible solution for the sustainable development of materials (Wang et al., 2017a). Among the myriad of biobased polymers, increasing attention has been given to poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) (PEF) as one of the most promising candidates for poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) due to its structural analog of PET (Menager et al., 2018, Sousa and Silvestre, 2022). It has been reported that PEF presents superior stiffness and strength (Sousa et al., 2021), additionally, PEF has highly increased barrier properties. The barriers of O2 and CO2 are extensively reported to be 2–11 (Sun et al., 2019, Xie et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2017a) and 10–19 (Wang et al., 2017a, Xie et al., 2020, Wang et al., 2016) times higher than those of PET, which shows the great application potential of PEF as a kind of biobased polymer in the field of packaging. On the one hand, PEF’s suitability for films and bottles is still limited due to the reasons, such as slow crystallization rate and brittle fracture (Sousa et al., 2021); on the other hand, the development of additional functional properties of PEF is also worth studying. For example, there are still benefits to exploring polyester materials to meet the requirements of packaging materials for antibacterial, anti-ultraviolet and anti-blue-light functions, etc.

Polymer nanocomposites have been synthesized with pleasing enhancement of mechanical and crystallization properties at very low filler loadings (Loos et al., 2020), due to the large specific surface area of nanosized particles. In addition, nanoparticles can endow matrix materials with some innovative properties, for example, endowing composite materials with antibacterial properties (Zhu, Cai and Sun, 2018, Zhang et al., 2022a), UV resistance properties (Hu et al., 2019a, Huang et al., 2019), becoming electrical components(Xu et al., 2019), optical components(Karthikeyan et al., 2019), etc. Azarakhsh et al. prepared functional composite materials with excellent resistance to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Escherichia coli bacteria by doping silver nanoparticles with polyvinyl alcohol (Azarakhsh, Bahiraei and Haidari, 2022). In another study, Karthikeyan et al. introduced nano silica into polyvinyl alcohol to prepare composite materials with excellent optical properties, which could be suitable for opto-electronic applications (Karthikeyan et al., 2019). Zibaei et al. prepared antioxidant composite materials with significantly reduced water vapor permeability using polyolefin elastomers, selenium nanoparticles, and triethyl citrate (Zibaei et al., 2023). Wang et al. studied a composite material with catalytic performance, achieving excellent wastewater treatment results (Wang et al., 2023a, Wang et al., 2023b). Watte et al. investigated the preparation of anatase nanocrystal films with photocatalytic activity on a polymer substrate, and evaluated the surface morphology, transparency and photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants of the films prepared by dipping coating(Watté et al., 2016). However, research on PEF/nanocomposites is still limited. (Xie et al., 2019) synthesized PEF/organically modified montmorillonite (OMMT) nanocomposites by melt polycondensation, and found that the melt crystallization, tensile modulus and strength were significantly improved when the addition of OMMT was 2.5 wt%. (Martino et al., 2017) designed PEF/sepiolite or OMMT nanocomposites by melt extrusion and compression molding, and found that nanocomposites with intercalated morphology presented higher thermal decomposition temperatures, and a change in Tg was observed when the amount of nanoparticles was higher. (Lotti et al., 2016) designed PEF/MWCNTs (with –COOH or –NH2), or GO nanocomposites by melt polycondensation and found that the fillers acted as nucleating agents for PEF crystallization to different extents, showing a faster crystallization rate and slightly decreased thermal stability. (Codou et al., 2017) studied the effect of different extrusion parameters on PEF/cellulose nanocomposites prepared by twin-screw extrusion, and the results showed that the crystallization half time of nanocomposites could be decreased progressively with the increasing percentage of cellulose, which could be reduced by approximately 35% at most. (Achilias et al., 2017) designed PEF/TiO2 and SiO2 nanocomposites, and showed that the presence of the nano additives resulted in higher transesterification kinetic rate constants and lower activation energies from both the experimental measurements and the theoretical simulation. which caused a slightly higher average molecular weight of nanocomposites. (Koltsakidou et al., 2019) selected PEF as the substrate and prepared PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites with high concentration of TiO2 NPs (20%), as effective photocatalysts for anti-inflammatory/analgesic drugs, which was another application scenario that could be developed besides being used as a packaging material. Most of these works on PEF/nanocomposites focused on crystallization rate, molecular weight, mechanical properties, thermal stability, etc. From the perspective of packaging material development, the innovative functions that nanoparticles can bring to the matrix, such as ultraviolet shielding, blue-light shielding, and antimicrobial, are also in urgent need of research.

Titanium dioxide could generate the unique photogenerated electron-hole pairs under light irradiation. In order to improve the photocatalytic performance of titanium dioxide, Yang et al. prepared unique Co3O4/TiO2 heterojunctions serves, which produced more active radicals and holes to enhance the photothermal performance (Yang et al., 2022b, Yang et al., 2022a).Chen et al. successfully prepared uniform tablet-like TiO2/C nanocomposites with high specific surface area by calcining MIL125(Ti) in order to degrade the tetracycline (TC) (Chen et al., 2020a). In the same year, Chen et al. prepared a novel octahedral TiO2-MIL-101 (Cr) (T-MCr) photocatalyst with type-II heterojunction and surface heterojunction and showed the outstanding photocatalytic activity (Chen et al., 2020b). Zhang et al. performed type-II heterojunction by the encapsulation of Materials of Institut Lavoisier (MIL-101), and then the heterophase junction was further constructed to improve the catalytic performance of the photocatalyst (Zhang et al., 2022c, Zhang et al., 2022b). Titanium dioxide also exhibits excellent performance in smaller sizes, such as titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs). On the one hand, inorganic particles have better temperature resistance than organic substances (Nakazato et al., 2017); on the other hand, TiO2 NPs have many advantages, such as biocompatibility, photocatalytic properties, high anti-ultraviolet and anti-blue-light properties, low toxicity, and antibacterial activity (Mesgari, Aalami and Sahebkar, 2021, Zhang and Rhim, 2022), and often are selected as nano fillers for polymers. Luo et al. used ultraviolet (UV) light for the directed migration of inorganic nanoparticles in a polymer film, producing an ultra-thin (100–200 nm) nanoparticle layer on the film's light-exposed surface (Luo et al., 2022). Kaur et al. prepared coating materials and titanium dioxide nanocomposites using lignin as raw materials, and coated TiO2 nanocomposite doped lignin coating on cotton fabric, showing good antibacterial activity (Kaur et al., 2021). Bouadjela et al. developed a strong polymer dispersed liquid crystal material and investigated the dynamic expansion of polymer networks (Bouadjela et al., 2017). Sadowski et al. treated polymers (PP) with low temperature oxygen plasma, then deposited TiO2 nanoparticles and sensitized them with organic ligands, enabling the synthesis of photocatalytic coatings with visible-induced photoactivity on the polymers (Sadowski et al., 2019). Salomatina et al. synthesized polytitanium oxide (PTO) nano-composite copolymers using gold nanoparticles (NPs) doped polyhydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) as organic matrix through a one-pot reaction (Salomatina et al., 2016). More and more studies have investigated the functions of polymer/nanocomposites doped with TiO2 NPs. According to the literature, polyesters (such as poly(butene 2,5-furan dicarboxylate) (PBF), polylactide (PLA), cellulose triacetate (CTA), poly(propylene carbonate) (PPC) and PMMA incorporated with TiO2 NPs maintained excellent ultraviolet shielding (Zhou et al., 2021, Gomez-Hermoso-de-Mendoza, Gutierrez and Tercjak, 2020, Wu et al., 2019, Can and Kaynak, 2020) and antibacterial properties (Zhang and Rhim, 2022, Siripatrawan and Kaewklin, 2018, Nikolic et al., 2021, Mesgari et al., 2021, Al-Tayyar, Youssef and Al-Hindi, 2020); moreover, their mechanical properties could be enhanced in a certain concentration range (Vejdan et al., 2016, Gomez-Hermoso-de-Mendoza et al., 2020). Adding TiO2 NPs to polyester may not only change the crystallization rate, mechanical properties and thermal stability of the substrate material, but may also make polymer nanocomposites exhibit antibacterial properties and ultraviolet shielding performance due to TiO2 NPs. Therefore, the combination of biobased PEF with TiO2 NPs is also promising.

However, brittle materials with inorganic rigid particles may have worse toughness (Gomez-Hermoso-de-Mendoza et al., 2020), which may require the substrate material to be a quasi-ductile material before preparing the nanocomposites. In this study, pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA) was selected as a chain extender to prepare quasi-ductile PEF conveniently. First, we achieved this goal by optimizing the concentration of PMDA and the synthetic conditions of the polymer. On this basis, a series of PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites with TiO2 NPs (60 nm, 0.5-10‰ wt./wt. of PEF) were prepared; subsequently, the concentration that produced comprehensive excellent mechanical properties was selected, and PEF/nanocomposites with the addition of TiO2 NPs (30 nm or 100 nm, 3‰) were also prepared as a contrast. The PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were characterized by 1H NMR, FT-IR, XRD and SEM. The isothermal crystallization behavior, thermal and mechanical properties were investigated with DSC, TGA, and tensile testing. The barrier properties, anti-ultraviolet, anti-blue-light and antibacterial functions were also assessed. Finally, the migration of TiO2 from the polymeric matrix into different food simulants was evaluated for comparison with FDA and EU guidance to explain the biosafety of the material in food and cosmetics packaging field. PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were prepared by one-pot polycondensation method with chain extender and nano-TiO2 in situ doping simultaneously, which provided a new idea for the modification of PEF.

2 Experimental

2.1 Experimental materials

Dimethyl 2,5-furandicarboxylate (DMFD, 98%) was obtained from Mianyang ChemTarget. Co. Ltd. (China). Ethylene glycol (EG, 99.8%), tetrabutyltitanate (TBT, 99%) and 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane (TCE, 98%) were purchased from Aldrich Co. Pyromellitic dianhydride (PMDA, 99%) used as chain extender and Titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs, primary particle size was 30 nm, 60 nm, 100 nm respectively, 99%) were purchased from Innochem. Phenol was purchased from Guangdong Guanghua Sci-Tech Co. Ltd. E. coli lyophilized powder was purchased from the mall North Na Chuanglian Biotechnology Co. LTD.

2.2 Synthesis of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites

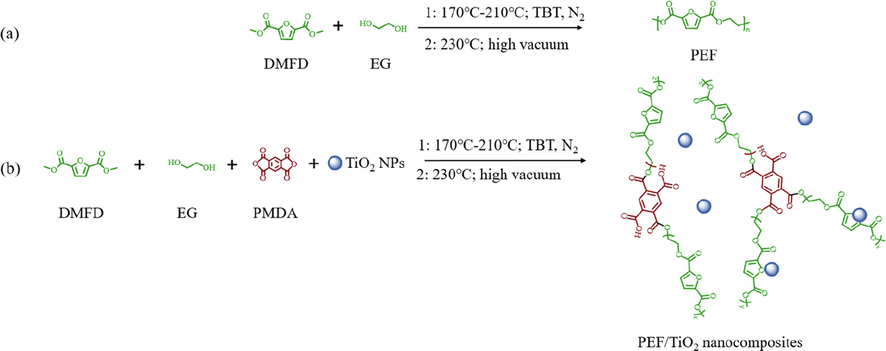

PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were also prepared using the one-pot polycondensation method (Fig. 1). The amounts of 60 nm-TiO2 NPs were 0.5-10‰ (wt./wt. of the PEF). Among them, the concentration of TiO2 NPs that produced the comprehensive mechanical properties was selected, and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were prepared by adding 30 nm or 100 nm TiO2 NPs (3‰). In order to obtain a uniform dispersion, TiO2 NPs were added into the three-necked round-bottomed flask already filled with EG. Stirred it magnetically overnight with tinfoil wrapped to get the dispersion (Zhou et al., 2021)). After that, PMDA (5‰ mol/mol of DMFD), DMFD (DMFD: EG = 1:1.6, mol/mol) and TBT (2‰ mol/mol of DMFD) were successively added to the reactor according to the above method. The process of selecting PMDA content and polyester synthesis conditions could be found in the supplementary information. The sample named PEF5,60,3 represented the nanocomposite materials with 5‰ concentration of PMDA and concentration of 60 nm-TiO2 NPs (3‰) added in situ during the synthesis process. All the obtained polyesters were prepared as film materials according tosupplementary information (1.2).

Synthesis route of a) PEF was synthesized by transesterification fusion polycondensation b) PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites was synthesized by the one-pot polycondensation.

2.3 Characterization

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (1H NMR) measurement was carried out on a Bruker Avance 400-MHz spectrometer. PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were dissolved in trifluoroacetic acid-d (TFA) with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal reference.

Weight-average molecular weight (Mw), number-average molecular weight (Mn) and its distribution (PDI) were determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) using a Waters 1515 HPLC apparatus. Hexafluorisopropanol (HFIP) supplemented with 0.005 mol/L sodium trifluoroacetate (CF3COONa) was used as solvent at 30 °C and the solvent flow rate was 1.0 mL/min. Mw, Mn and PDI were determined using polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) standard with a narrow PDI.

The ηsp/C were measured at 25 °C using an Ubbelohde viscometer (φ = 0.84). 0.125 g products were put into a 25 mL volumetric flask and dissolve by a mixture solvent composed of phenol and 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane (1/1, wt./wt.).

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) was performed with a Shimadzu IRTracer-100 using a KBr pellet. In the absorbance mode, scans were collected in the spectral region of 400–4000 cm−1.

The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of polyesters were recorded using Empyream wide-angle X-ray scattering measurements and scanning speed of 12.5°/min over a range of 2θ = 5° to 80° at room temperature.

N2 adsorption desorption tests were conducted on the prepared 30 nm, 60 nm, and 100 nm TiO2 NPs using Quadrasorb evo N2 adsorption–desorption.

The morphology of the PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites after platinum coating was observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi JSM-7800F) operated at an accelerating voltage of 3 kV.

Thermal transition properties and crystallization kinetics were performed by means of a Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) on a DSC-25 thermal analyzer (TA Instrument, USA), calibrated with pure Indium and Zinc standards. Nitrogen gas flow rate was 50 mL/min. The samples were firstly heated from room temperature to 235 °C, and kept for 3 min to erase the thermal history, then cooled down to −20 °C, and then heated again to 235 °C, all rates were 10 °C/min. The total percentage crystallinity (Xc) of the sample was calculated by Eq. (1)

for 100% crystalline PEF (Qu et al., 2021)).

The characterization procedure of isothermal crystallization kinetics was set as follows: the samples were heated from the room temperature to 235 °C at the rate of 50 °C /min and kept for 3 min to eliminate the thermal history, then quenched directly to Tc and maintained at this temperature for melt crystallization. Cooling to −20 °C and maintained 1 min at the rate of 50 °C /min. Finally, they were raised to 235 °C at the rate of 10 °C /min. Crystallization temperatures Tc were varied from 145 °C to 175 °C. The relative crystallinity Xt can be calculated as Eq. (2):

To, T, and T∞ are the initial, arbitrary, and final crystallization temperatures, respectively.

TGA analysis was carried out using TGA-55 (TA Instrument, USA). About 5–10 mg samples were heating to 800 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min in a 50 mL/min flow of N2.

Tensile modulus (Et), tensile strength (σm) and elongation at break (εb) of films were measured using a Instron 3366 with a strain rate of 0.5 mm/min at room temperature. The film samples were cut into rectangles strips (5 cm × 1 cm) and equilibrated under 50 ± 1% RH at 25 °C for 48 h. Film thickness was from the average of ten point determined by a digital micrometer with an accuracy of 0.01 mm. The impact strength was obtained from a film pendulum impact tester (FIT-01) produced by Labthink. Referring to the ASTM D3420 and GB 8809–88, the sample (ø=100 mm, thickness of 0.2 mm) was struck by the pendulum which impact energy was 1 J to evaluate its impact strength.

The CO2 and O2 barrier properties of the samples were investigated at 23 °C with the relative humidity (RH) of 50% by Labthink VAC-V2 gas permeability tester (0.1 Mpa), called manometric method. The CO2 and O2 used in the test process was 99.99%. The diameter of the film is 5 cm and thickness was from the average of ten point determined by a digital micrometer. Chamber and sample temperatures were controlled by an external thermostat. All experiments were run in triplicate.

The UV-shielding properties were measured by a Shimadzu (UV-2600) in the range of 200–800 nm. The UV blocking efficiency of the films was calculated according to the following Eq. (3):

The antibacterial analysis of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposite films against the bacteria was studied. Gram-positive bacteria Escherichia coli (E. coli). Freeze-dried E. coli powder was transferred to sterilized solid medium for three consecutive days under aseptic conditions to obtain stably growing strains. Scrape 1 ∼ 2 scoops of single colony into sterilized tubes filled with liquid culture medium to get bacterial suspension, diluted into 105 CFU/mL of E. coli. Each test film (2 × 2 cm2) was placed in sterilized petri dishes under aseptic conditions. 0.2 mL of bacteria suspension was added onto the surface of each film covered with sterilized polyethylene film. They were exposed to UV light (365 nm) illuminated by two 15 W black light lamps for 30 min (the samples were placed approximately 15 cm far from the lamps), and then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C. Then the samples and covering were washed with 20 mL 0.85% NaCl solution in order to remove the adhered bacteria. Quantification of colony review in eluate by aerobic plate count method and the antibacterial activity (R) was calculated by the following Eq. (4).

The TiO2 NPs migration test was conducted at room temperature (23 ± 2 °C). According to the recommendation from FDA and EU (European Union), distilled water, acetic acid, ethanol, and n-hexane were selected for the migration fluid, as neutral, acidic, alcohol and fat content, respectively. Each circular film sample (r = 2.5 cm, 0.5 g) was put into a 50 mL glass vial filled with 40 mL simulates, the whole film was immersed in the liquid, and the magnetic rotor was stirred in the bottle. The vial was kept at room temperature for 35 days. Remove 1 mL of solution every seven days, shaking each bottle by hand for half a minute before sampling to ensure uniform sampling. Digestion test of migration TiO2 was based on Lian et al. and some modifications were made (Lian et al., 2016).) In brief, the 1 mL food simulant was placed in a pressure resistant glass container and 5 g of ammoniumsulfate ((NH4)2SO4) and 10 mL of concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%) were incorporated. Those blend solutions were digested using oil bath at 200 °C for 3 h. After cooling at room temperature, the volume was fixed and tested by an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-MS).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Preparation of PEF and the extended PEF

PEF and the extended PEF were synthesized by one-pot polycondensation (transesterification and polycondensation). The gel content and ηsp/C of polyesters were determined, as shown in Table 1. The optimization process was described in detail in the supplementary information (1.2). After optimization of the PMDA content and synthesis conditions, the ηsp/C of polyester (PEF5) was increased to 0.88 dL/g, and there was no gel content (less than 40%), which showed an improvement in the molecular weight of polyester.

Samples

PMDA content (‰)

Polycondensation condition

Gel content (%)

ηsp/C (dL/g)

PEF

0

230 °C × 4 h

2.5

0.20

PEF0.5

0.5

230 °C × 4 h

2.4

0.27

PEF1

1

230 °C × 4 h

2.8

0.39

PEF3

3

230 °C × 4 h

3.5

0.65

PEF5

5

230 °C × 4 h

4.7

0.73

PEF7

7

230 °C × 4 h

56.7

–

PEF5

5

240 °C × 4 h

45.3

–

PEF5

5

250 °C × 4 h

72.8

–

PEF5

5

230 °C × 5 h

5.5

0.88

PEF5

5

230 °C × 6 h

41.3

–

PEF5

5

230 °C × 8 h

85.5

–

The rheological characterization of PEF and the extended PEF was performed at 230 °C in Fig.S1. For Groups A and B, G', G“ and η* were proportional to the concentration of PMDA, polycondensation temperature and polycondensation time. The results showed that the viscoelasticity of polyester was improved by increasing the content of chain extender and optimizing the reaction conditions, showing the effectiveness of chain extension. In addition, the shear-thinning phenomenon was observed in all materials, in which η* decreased as the angular frequency increased. This indicated that entanglement couplings occurred between the high molecular weight part and the part associated with the branches of the long branched chain, and a long time relaxation mechanism was thus generated (Pandey et al., 2020). Therefore, in addition to the highest ηsp/C, PEF5 (obtained by condensation polymerization at 230 °C for 5 h) had the highest G', G” and η*, which confirmed that polyester was chain-extended successfully. The Cole-Cole plot in Fig. S2 also confirmed that the chain extended products were significantly different from the pure PEF; the circular mark of the line type disappeared and the tails of the curve were upturned, confirming the existence of chain expansion.

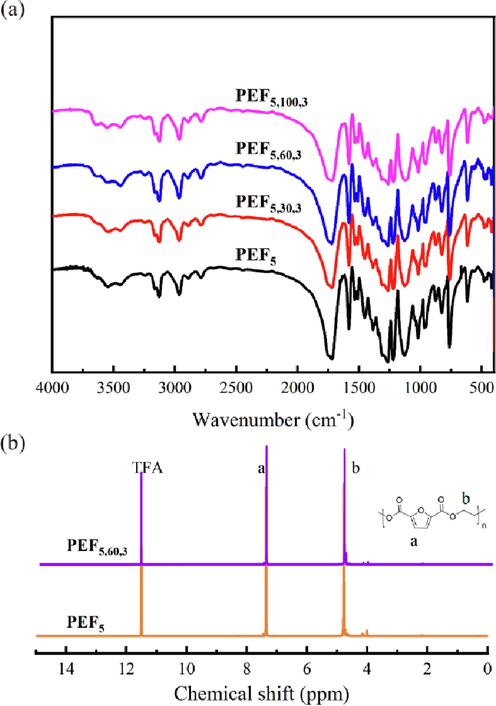

3.2 Structure characterization

The structure of the prepared PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites was verified with FT-IR spectroscopy in Fig. 2a and Fig. S4. The peaks observed at 3128 cm−1, 1581 cm−1, and 1020 cm−1 corresponded to C–H, C = C, and C-O-C, respectively. The band peaking at 2966 cm−1 was due to –CH2-, and the peak at 1727 cm−1 corresponded to the C = O bond. The peaks at 958 cm−1, 820 cm−1, and 760 cm−1 were assigned to furan ring bending vibrations. The successful synthesis of PEF was confirmed by FT-IR results (Xie et al., 2020). Moreover, almost no difference was observed at the peak position, which suggested that the TiO2 NPs and PEF5 were physically doped without forming new bonds.

FT-IR spectra a) and 1H NMR spectra b) of PEF5 and PEF5,60,3.

The chemical structures and compositions of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were characterized by 1H NMR. Take PEF5 and PEF5,60,3, for example, shown in Fig. 2b. The protons attached to the furan ring showed chemical shifts at 7.36 ppm, and the protons of the glycol subunit appeared at 4.78 ppm. The area ratio of the two peaks was 1:2. The peak position was in accordance with the results reported in the literature (Achilias et al., 2017, Lotti et al., 2016), showing the successful synthesis of polyester. In addition, the branched structure of PEF was not shown in the FT-IR spectra and 1H NMR spectra due to the low concentration of chain extender.

The sample named PEF5,60,3 represented the nanocomposite materials with 5‰ concentration of PMDA and 3‰ concentration of 60 nm-TiO2 NPs added in situ during the synthesis process. The ηsp/C of the PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were 0.73-0.91 dL/g in Table 2, suggesting that high molecular weight nanocomposites had been synthesized successfully. The ηsp/C of PEF/nanocomposites increased with the TiO2 nanoparticle feeding ratio up to 5‰, indicating that the presence of TiO2 NPs contributed to the molecular weight growth of the polyester (Zhou et al., 2021). In addition, the Mn of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites was higher than that of PEF (2.16 × 104 g/mol), which ranging from 3.12 × 104 g/mol to 5.48 × 104 g/mol. With the content of 60 nm TiO2 particles increased, the Mn of the nanocomposite materials first increased and then decreased, reaching a maximum value of 5.48 × 104 g/mol at PEF5,60,5. The nanocomposite materials with 30 nm or 100 nm TiO2 NPs were also consistent with this rule, indicating that the content rather than the particle size of TiO2 NPs had a greater effect on the molecular weight of polyester.

Samples

Mn × 104 (g/mol)

Mw × 104 (g/mol)

PDI

ηsp/C (dL/g)

PEF

2.16

3.18

1.47

0.20

PEF5

3.90

10.38

2.66

0.81

PEF5,60,0.5

4.08

9.77

2.39

0.77

PEF5,60,1

3.92

13.87

3.54

0.73

PEF5,60,3

4.23

15.52

3.67

0.89

PEF5,60,5

5.48

17.43

3.18

0.91

PEF5,60,7

3.24

15.12

4.67

0.87

PEF5,60,10

3.12

10.04

3.22

0.81

PEF5,30,3

4.95

12.63

2.55

0.90

PEF5,100,3

4.22

9.93

2.35

0.83

3.3 Morphology characterization

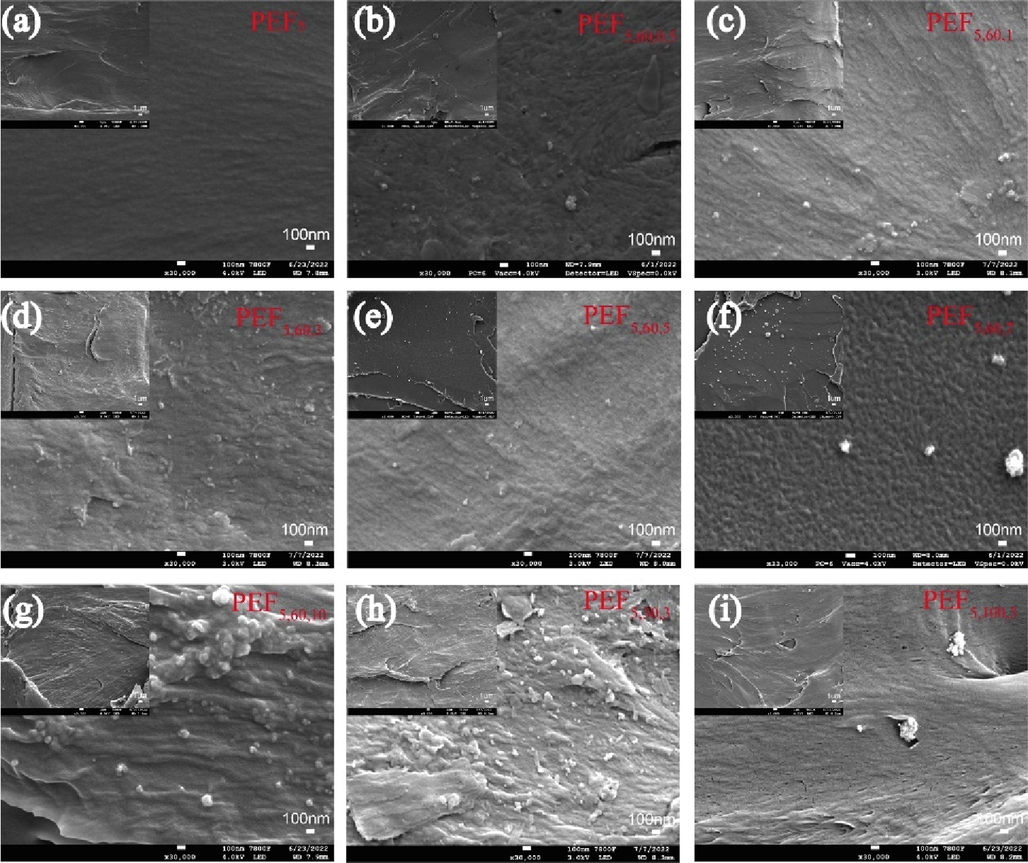

Fig. 3 shows the SEM micrograph to investigate the dispersion of TiO2 NPs within the matrix materials as well as the fracture surface morphology of the films(Achilias et al., 2017). The PEF5 in Fig. 3a showed smooth surface and compact structure with no particles. In sharp contrast, the PEF/TiO2 nanocomposite films in Fig. 3b-i presented much rougher surfaces and some crack tips, implying that the polymers exhibited ductile fracture and enhanced mechanical properties(Wu et al., 2019). In Fig. 3b-e, TiO2 NPs presented fine dispersion inside the films as well as on the surface. However, some extent of agglomeration was found across the entire fracture surface at concentrations of 7‰ and above, and the size of TiO2 NPs after agglomeration was still on the nanometer scale. In Fig. 3d and h-i, the higher the particle size of TiO2, the more likely it was to aggregate. Almost no particle pull-out holes were observed in all pictures which also revealed that the interfacial adhesion between the matrix and TiO2 particles used was strong (Can and Kaynak, 2019).

SEM micrographs of the fractured surfaces of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites: a) PEF5, b) PEF5,60,0.5, c) PEF5,60,1, d) PEF5,60,3, e) PEF5,60,5, f) PEF5,60,7, g) PEF5,60,10, h) PEF5,30,3, i) PEF5,100,3.

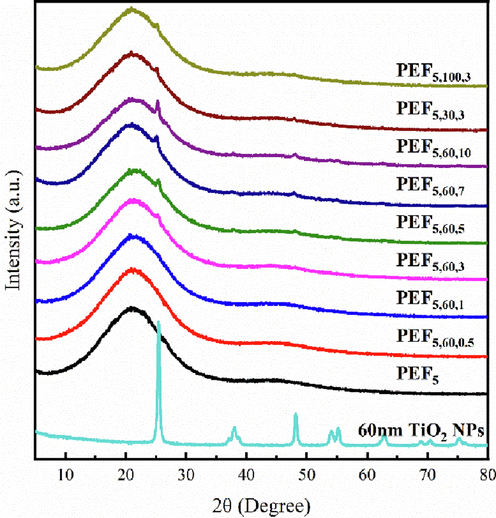

3.4 XRD characterization

Fig. 4 shows the XRD patterns of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites. A broad peak appeared at 2θ of approximately 20° in each sample, proving that PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were amorphous. The characteristic peak of anatase type TiO2 appeared when the addition level reached 3‰ and above. The peaks at 2θ = 25.3°, 37.9°, 47.8°, 54.5°, 63.1°, 69.4° and 75.2° indicated that the crystal form of TiO2 NPs had not been disturbed during the process. In addition, the intensity of the peaks and content of TiO2 NPs were closely related, and the peaks of PEF5,30,3, PEF5,60,3 and PEF5,100,3 were similar. The results were the same as those reported in the literature(Loos et al., 2020).

XRD of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites.

3.5 Crystallization behaviors

3.5.1 Non-isothermal crystallization

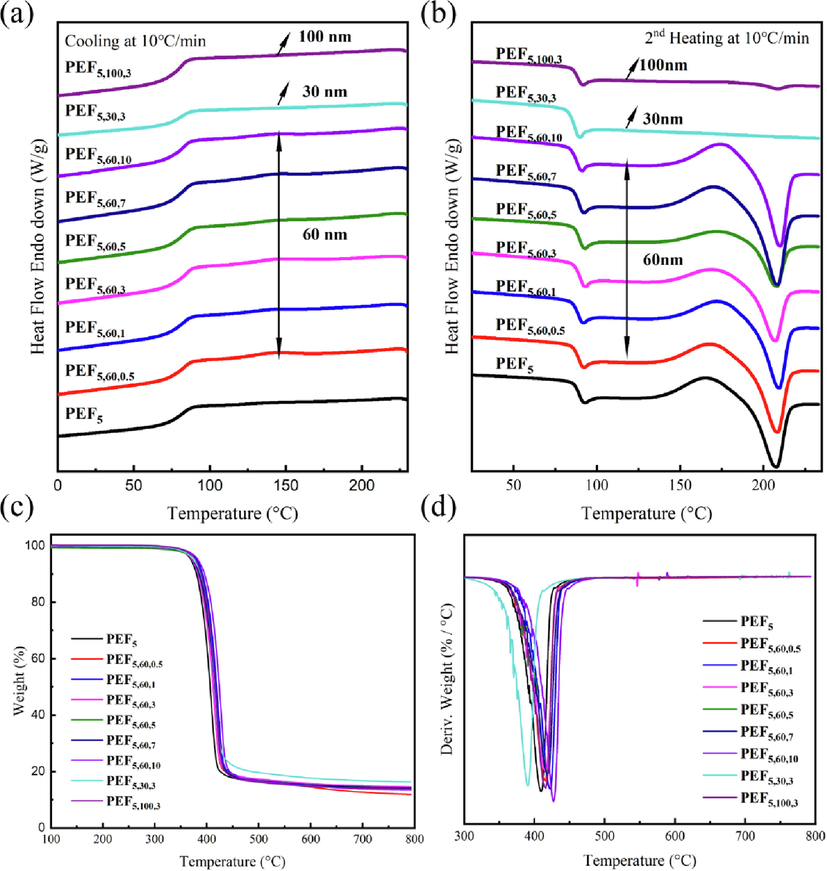

Fig. 5a-b and Table 3 depict the DSC thermograms records and results of PEF, PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites. The glass transition temperature (Tg) of PEF5 was 1.8 °C higher than that of PEF (86.5 °C), while the melting point (Tm) was 8.8 °C lower than that of PEF. PEF exhibited a melting peak (ΔHm = 33.8 J/g) at 216.8 °C in the second heating, higher than that of PEF5 (15.9 J/g) at 208 °C. At the same time, there did not result in a noticeable change in Tg (approximately 88 °C) and Tm (approximately 208 °C) during the composite materials with different concentrations of 60 nm TiO2 NPs, which possibly due to the relatively low concentration of TiO2 NPs in composites (Luo et al., 2009). Until the addition amount reaches 8%, TiO2 NPs showed an effect on the cold crystallization temperature of the substrate PLA (Luo et al., 2009). However, the Tm of PEF5,30,3 and PEF5,100,3 almost disappeared, which showed that the crystallization property was decreased, and the Tg was 1.3 °C-3.4 °C lower than that of PEF5,60,3. It was reported that enthalpy relaxation peaks were observed, resulting in a Tg shift to a slightly higher temperature (Papageorgiou et al., 2022), agreeing with the phenomenon in this study.

DSC a, b) and TGA c, d) curves of PEF, PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites under N2 atmosphere.

Polymers

Cooling

2nd heating

Tc (°C)

ΔHc (J/g)

Tg (°C)

Tcc (°C)

ΔHcc (J/g)

Tm (°C)

ΔHm (J/g)

Xc (%)

PEF

148.7

9.4

86.5

162.1

16.2

216.8

33.8

12.5

PEF5

142.4

2.3

88.3

164.9

9.2

208.0

15.9

4.8

PEF5,60,0.5

141.6

7.8

88.0

167.9

7.7

208.4

14.9

5.0

PEF5,60,1

145.3

4.3

88.2

160.1

7.8

208.3

23.0

10.7

PEF5,60,3

146.8

1.1

88.7

168.3

5.4

207.3

8.7

2.3

PEF5,60,5

145.4

0.7

88.6

172.1

5.8

208.1

8.6

2.0

PEF5,60,7

144.1

0.9

88.2

169.7

9.6

208.5

16.8

5.1

PEF5,60,10

144.8

1.2

88.1

169.6

7.9

207.8

14.3

4.5

PEF5,30,3

–

–

85.3

–

–

–

–

–

PEF5,100,3

–

–

87.4

–

–

208.4

0.9

–

Among all samples, the Tcc of PEF5 and the nanocomposite materials (60 nm) was more obvious, probably due to the positive effect of chain extender on polyester crystallization and the nucleating agent effect of 60 nm TiO2. The accelerated crystallization rate of polyester might be attributed to the nucleation effect when TiO2 NPs were uniformly distributed, but at high concentrations, nanoparticles might agglomerate to prevent the formation of nucleation sites and hinder the continuous growth of crystals (Vassiliou et al., 2008, Tang et al., 2016).

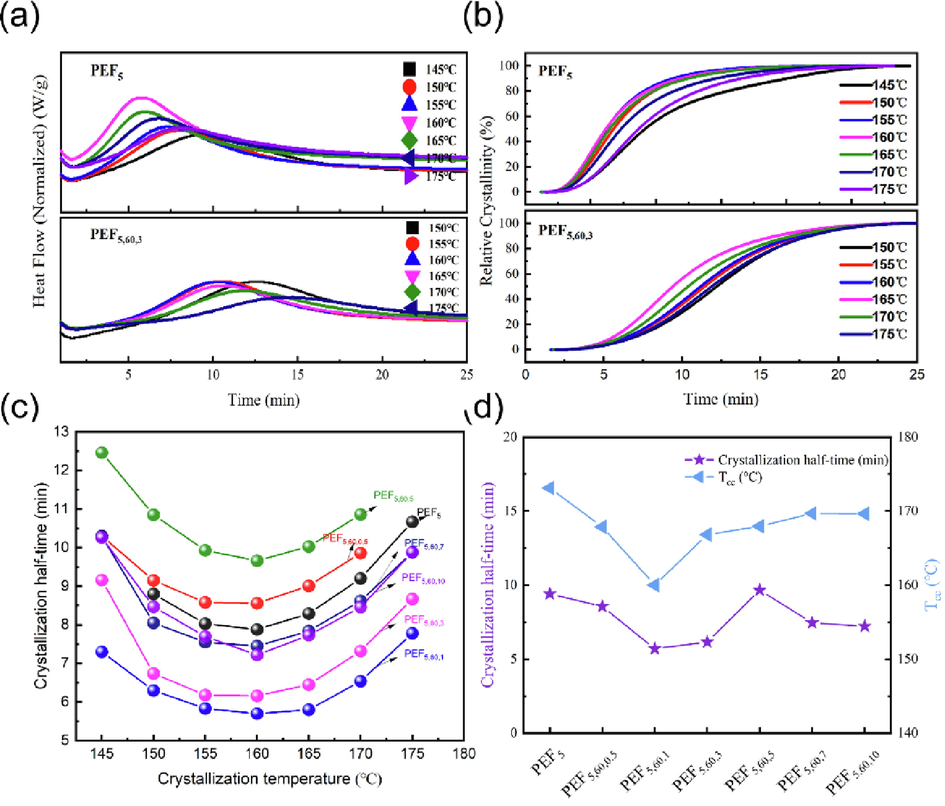

3.5.2 Isothermal crystallization

The isothermal crystallization properties of the PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites (60 nm) were also investigated by DSC. Fig. 6a and Fig. S7 depicted the thermograms recorded during successive heating for samples crystallized from the melt at different isothermal crystallization temperatures (Tc) ranging from 140 °C to 175 °C. All samples showed wide crystallization peaks, and the curves at each sample shifted with the isothermal temperature. To quantitatively study the crystallinity behavior, the relative crystallinity (Xt) and semi-crystallization time (t1/2) at different temperatures were calculated. The Xt versus time and t1/2 versus temperature curves are shown in Fig. 5a-b and Fig. S8. The t1/2 showed a trend of decreasing and then increasing in the range of 145 °C-175 °C, and reached the lowest at 160 °C (Stoclet et al., 2015). The t 1/2 of all samples ranged from 5.7 min to 9.66 min at 160 °C and reached the fastest at PEF5,60,3 of only 6.16 min, which was increased by 21.8% compared with PEF5 (except for 5.7 min at PEF5,60,1, which was attributed to the low molecular weight). It was reasonable that the variation pattern remained consistent with Tcc in Fig. 6d. Inorganic nanoparticles primarily have two effects on the crystallization of materials in nanocomposites: One is the reduction in chain segment mobility, and the other is the contribution of nanoparticles to heterogeneous nucleation (Nikam and Deshpande, 2019, Farhoodi et al., 2013). These heterogeneous nucleation sites could adsorb polymer chains in the melt for orderly arrangement to form crystal nucleus (Kourtidou et al., 2023) Hao et al.'s research showed that TiO2 NPs impart the smaller and more defects spherulites to the resulting nanocomposites, resulting in a decrease in Tm of the nanocomposite materials, which is consistent with the results of this article (Li, 2006).

Isothermal crystallization of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites: a, b) DSC traces of isothermal crystallization of samples within 25 min, c) crystallization half-time of samples at various temperatures, d) crystallization half-time at 160 °C and cold crystallization temperature of samples.

In short, the crystallization rate was related to the isothermal crystallization temperature, concentration and dispersion of nanoparticles in the matrix (Luyt and Gasmi, 2017, Nikam and Deshpande, 2019). Moreover, the t1/2 values of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were much lower than the 18.2 min-40.3 min reported in the literature, which their molecular weight ranged from 12000 g/mol to 28000 g/mol (Stoclet et al., 2015, van Berkel et al., 2015).

3.6 Thermal stability

The thermal stability of the PEF, PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites was determined by TGA, as shown in Fig. 5c-d and Table 4. PEF and PEF5 presented similar Td,5% and Tdmax of 369 °C and 14%, respectively. The Td,5% and Tdmax increased with increasing concentration of 60 nm TiO2, and they were approximately 2.1 °C-4.4 °C and 2.8 °C-11 °C higher than those of PEF5 at 369.9 °C and 409.7 °C, respectively. Naturally, as the concentration of inorganic particles increased, so did the residual amount. This could be attributed to the assumption of physical interactions between TiO2 NPs and the matrix, which required higher thermal energy to disrupt these interactions, thereby improving the thermal stability of nanocomposites (Youssef, Abd El-Aziz and Morsi, 2022). PEF5,30,3 and PEF5,100,3 had higher Td,5% and Tdmax than PEF5,60,3, showing the different thermal properties of PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites with different particle sizes. In the substrate material, TiO2 NPs could play a physical crosslinking role to improve the thermal stability of polyester (Vassiliou et al., 2008). The excellent thermal stability was of great importance for determining their potential application.

Polymers

Td,5%a (°C)

Tdmaxb (°C)

R600c (wt%)

PEF

369.4

416.1

14.0

PEF5

369.9

409.7

14.9

PEF5,60,0.5

373.9

415.8

14.5

PEF5,60,1

372.6

412.5

15.3

PEF5,60,3

372.0

415.5

15.7

PEF5,60,5

373.7

418.9

15.3

PEF5,60,7

374.3

418.5

15.2

PEF5,60,10

374.0

420.7

15.1

PEF5,30,3

375.0

417.1

17.6

PEF5,100,3

378.8

420.0

14.7

3.7 Mechanical properties

The film of pure PEF was brittle and have not been tested for tensile strength. The PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were subjected to tensile and impact experiments at room temperature, and the results are summarized in Table 5. The Et of the PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites was higher than that of PEF5 (an increase of 9%∼16%), except for PEF5,60,1 (due to its low molecular weight). With the increase in the content of 60 nm TiO2 NPs, the Et showed a trend of increasing from PEF5 (2158 MPa) first and then decreasing to PEF5,60,10 (2038 MPa). The improvement in the Et of nanocomposites by the addition of stiff TiO2 NPs was expected at low concentration, this was due to the stiff structure of TiO2 NPs and the close connection between the TiO2 NPs and the matrix (shown in Fig. 3); however, high concentrations of TiO2 nanoparticles might reduce the Et of nanocomposites due to agglomeration (Gomez-Hermoso-de-Mendoza et al., 2020, Can and Kaynak, 2019). The εb of most nanocomposites was lower than that of PEF5, which is also similar to that reported in the literature (Can and Kaynak, 2019). TiO2 NPs fillers as heterogeneous solid nanoparticles may prevent polymer stress-induced crystallization, reducing the fracture resistance of the complex network, according to research by Farhodi et al. The decrease in fracture elongation of nanocomposites was consistent with this research's findings (Farhoodi et al., 2013). Compared with PEF5, PEF5,60,3 had the best comprehensive performance and its Et, σm and εb increased by 36%, 14%, and 16%, respectively. However, the Et of PEF5,30,3 and PEF5,100,3 was increased by only 2% and 10%, respectively, compared with PEF5. The impact strength of PEF5 showed a great improvement compared with PEF in this study (the film prepared by PEF was brittle), proving that the addition of chain extender was effective for the preparation of quasi-toughness polyester. The impact strength of PEF5 (2.04 × 103 J/m2) was lower than that reported in the literature (7.2 × 103 J/m2) (Zhang et al., 2020), which was significantly improved in nanocomposite materials. The impact strength of the PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites showed a strict growth law from 10.4 × 103 J/m2 to 52.5 × 103 J/m2 with increasing of TiO2 NPs concentration (PEF5,30,3 and PEF5,100,3 also included). This improvement in impact strength was also expected, which might be due to the ability of nanoparticles to fill holes or defects in the material, thus increasing the stress on the surface where the stress was evenly distributed (Zhang et al., 2021, Al-Zubaydi, Salih and Al-Dabbagh, 2020, Zhang et al., 2020). The tight connection between the matrix and the nanoparticles was more conducive to stress transfer, thereby delaying crack propagation (Can and Kaynak, 2019).

Sample

Eta (MPa)

σm b (MPa)

εbc (%)

Impact strength (×103, J/m2)

PEF5

2158 ± 84d

67 ± 10

4.4 ± 0.1

2.04

PEF5,60,0.5

2351 ± 183

82 ± 5

5.6 ± 1.1

10.4

PEF5,60,1

2118 ± 184

63 ± 8

4.1 ± 1.0

19.5

PEF5,60,3

2485 ± 78

74 ± 4

4.0 ± 0.2

21.3

PEF5,60,5

2483 ± 14

49 ± 3

2.5 ± 0.2

28.7

PEF5,60,7

2511 ± 77

60 ± 6

3.3 ± 0.5

50.6

PEF5,60,10

2038 ± 19

47 ± 5

3.0 ± 0.3

52.2

PEF5,30,3

2191 ± 194

71 ± 12

4.5 ± 1.7

18.3

PEF5,100,3

2368 ± 68

58 ± 17

3.4 ± 1.4

19.0

3.8 Barrier properties

The CO2 and O2 permeability of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were determined by the differential pressure method, and the effects of content and particle size were also discussed in Table 6. In this study, all materials presented higher barrier properties compared to PET and PLA materials, and the permeability of CO2 was slightly higher than that reported in the literature. It was reported that large pores between molecules lead to higher gas and liquid permeability due to the formation of branched structure. The polymer prepared by PET and PMDA showed higher carbon loss (13.5% for PET and 15% for branched PET), which showed that the formation of a branched structure improved the permeability rate of CO2 (Awaja and Pavel, 2005).The permeability of CO2 increased with the addition of TiO2 NPs, from 0.037 barrer for PEF5 to 0.063 barrer for PEF5,60,10; however, the barrier performance of O2 became better, and the BIF value increased from 1.1 for PEF5 to 2.6 for PEF5,60,0.5. The most likely value of CO2/O2 in nanocomposite materials was located at 1 ∼ 2, higher than PEF5, which was 0.67. Despite this, the CO2 and O2 barrier properties of the PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites were still in the same order of magnitude and maintained excellent gas barrier properties. Similar to the findings reported by Silva-Leyton et al., the tendency of composite materials towards CO2 and O2 was not significant (Silva-Leyton et al., 2019). The good barrier performance of the composite material is unaffected by the TiO2 NPs due to their small particle size, low concentration, and physical doping.

Sample

CO2 permeability coefficient (barrera)

BIFpb

O2 permeability coefficient (barrer)

BIFp

CO2/O2

PET (Wang et al., 2016, Wang et al., 2017b)

0.13

1

0.060

1

2.17

PLA (Hu et al., 2019b)

1.0

0.13

0.25

0.24

4.00

PEF(Wang et al., 2017b)

0.010

13.0

0.011

5.5

0.9

PEF5

0.037

3.5

0.055

1.1

0.67

PEF5,60,0.5

0.043

3.0

0.023

2.6

1.87

PEF5,60,1

0.076

1.7

0.048

1.3

1.58

PEF5,60,3

0.043

3.0

0.044

1.4

0.98

PEF5,60,5

0.059

2.2

0.057

1.1

1.04

PEF5,60,7

0.043

3.0

0.041

1.5

1.05

PEF5,60,10

0.063

2.1

0.054

1.1

1.17

PEF5,30,3

0.045

2.9

0.034

1.8

1.35

PEF5,100,3

0.059

2.2

0.066

0.9

0.89

3.9 Anti-ultraviolet and anti-blue-light functions

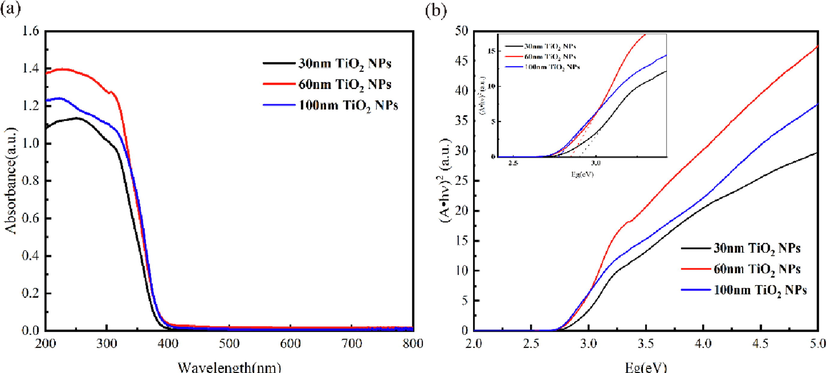

To examine the optical absorption study of 30 nm TiO2 NPs, 60 nm TiO2 NPs and 100 nm TiO2 NPs by UV-vis, Diffuse reflectance (DRS) spectra and results are shown in Fig. 7a. All three curves demonstrated a cutoff absorption edge at approximately 410 nm, which exhibited a similar pattern to the unmodified TiO2 NPs reported in the literature(Kite et al., 2021). This indicated that the change in particle size of TiO2 NPs did not result in a difference in the bandgap of the sample. From Fig. 7b, it could be seen that the bandgap energy values of 30 nm, 60 nm, and 100 nm TiO2 NPs were 2.90 eV, 2.84 eV, 2.77 eV, respectively. TiO2 is an N-type semiconductor. When ultraviolet light with a wavelength less than 385 nm irradiates TiO2, electrons in the valence band can absorb ultraviolet light and be excited to the conduction band, producing electron hole pairs. In this excited state, electrons generated by light can recombine with holes, during which light energy can be converted into heat or other forms of energy. Therefore, TiO2 has the function of absorbing ultraviolet light(Zhou et al., 2021).

a) uv-vis DRS spectra and b) Tauc’s plots of TiO2 NPs.

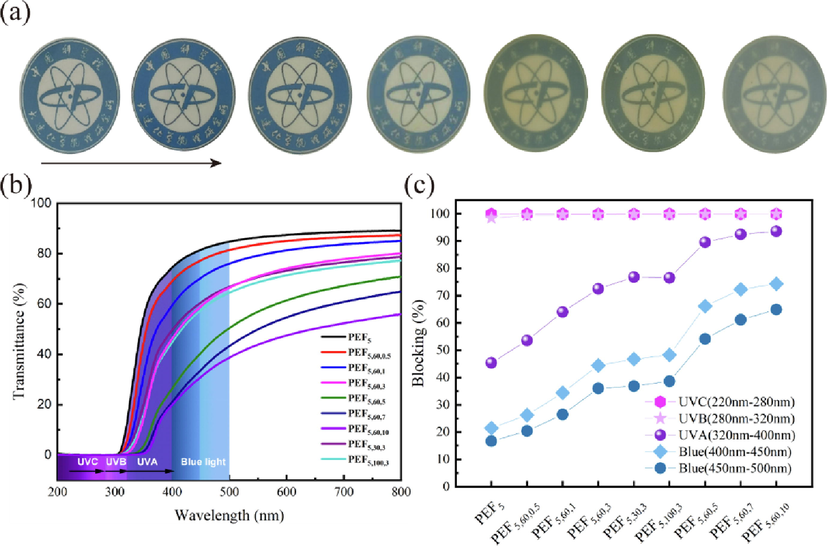

Photographs of the PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposite films are shown in Fig. 8a. The PEF5 film was colorless and transparent. With increasing of 60 nm-TiO2 NPs concentration, the transmittance of the films decreased and showed a white color gradually to varying degrees. The ultraviolet–visible light spectra (200 nm to 800 nm) are shown in Fig. 8b, which shows that all the films had decreasing transmittance as the wavelength of light decreased. All films exhibited an obvious shielding effect on UVB (280 nm-320 nm) and UVC (220 nm-280 nm), and the blocking rate shown in Fig. 8c increased from 98.43% to 99.95% and from 99.92% to 99.96%, respectively. In the UVA (320 nm-400 nm) region, the decrease in transmittance indicated the effect of TiO2 NPs on the anti-ultraviolet properties of films, and the blocking rate changed from 45.38% to 93.54%. The PEF5,60,3 prevented 72.49% of UVA range, and the blocking rate of PEF5,30,3 and PEF5,100,3 was 76.80% and 76.53%, respectively, which showed excellent ultraviolet shielding properties with a very small amount of TiO2 nanoparticles. The shielding effect of ultraviolet light could effectively reduce the deterioration of packaging contents, and extend the life of the film. The blocking rate of blue light (400 nm-500 nm) in different bands also increased with the increasing nanoparticle concentration, from 21.5% to 74.3% at 400 nm-450 nm, and from 16.7% to 64.9% at 450 nm-500 nm. Among them, high-frequency shortwave blue light (400 nm-450 nm) is more harmful to the human body, mainly causing retinal damage (Yang et al., 2020). PEF5 showed a high degree of transparency, which was 89.2% at 800 nm, followed by a progressively decreasing value with increasing TiO2 content. PEF5,60,10 maintained the lowest transmittance, which was only 55.9% at 800 nm. These results indicated that the higher the concentration of TiO2 NPs, the better anti-ultraviolet and anti-blue-light properties were obtained, although the transparency was reduced.

a) digital photos, b) uv–vis spectra and c) uv blocking parameters of pef5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites.

3.10 Antibacterial properties

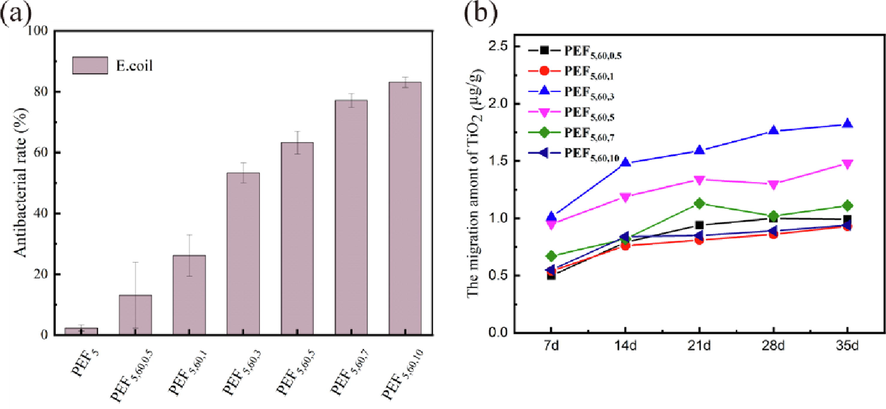

TiO2 NPs, Ag NPs, CuO NPs have demonstrated successful antimicrobial activity in food packaging materials(He et al., 2016, Kim et al., 2007, Siripatrawan and Kaewklin, 2018). The antibacterial properties of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposite films against the E. coli were studied in Fig. 9a (He et al., 2016). As expected, the PEF5 film did not show significant antibacterial activity; however, nanocomposites with TiO2 NPs exhibited strong antibacterial activity against gram-negative bacteria (E. coli) under UV light. With the increase in the amount of TiO2 NPs added, their antibacterial rate against E. coli also gradually increased, from 2% of PEF5 to 83% of PEF5,60,10. TiO2 NPs undergoes photocatalytic reactions when illuminated with UV light, generating electrons (e-) and holes (h+), which could react with substances in the air and generated O2– and OH∙, respectively (Siripatrawan and Kaewklin, 2018, He et al., 2016, Zhang et al., 2022a). It was reported that ROS such as O2– and OH∙ could oxidize polyunsaturated phospholipids in microbial cell membranes, causing changes in cell morphology and cytoplasmic leakage to achieve sterilization purposes (Siripatrawan and Kaewklin, 2018). Therefore, when irradiated TiO2 nanoparticles come into contact with microorganisms, these active substances easily cause cell lysis. The higher the TiO2 content was, the more reactive oxygen species were generated, and the resultant antibacterial rate substantially increased.

a) growth inhibition of pef5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites against E. coli, b) The migration amount of TiO2 NPs in 3% acetic acid solution.

3.11 Migration of titanium

A migration experiment was set up to study the safety of PEF5 and PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites used in the food or cosmetics packaging industry, where migration of nanoparticles would result in oral intake or dermal exposure. To the best of our knowledge, there were no specific guidelines concerning packaging/content interaction studies, but the migration behavior of polymer/nanocomposite materials used as cosmetic packaging was studied with reference to the standards of food contact materials (Connolly et al., 2019). The migration assay was set up to determine the rate of TiO2 NPs migration to the simulated solution during 35 days of storage, as shown in Fig. 9b. According to the European Commission 2011 (Lian, Zhang and Zhao, 2016, Liu et al., 2016) and GB/T 23296.1, distilled water, 3% acetic acid, and ethanol were used to simulate aqueous, acidic, and alcoholic foods, while n-hexane was the fatty food simulant. For 3% acetic acid, the migration rates ranged from 0.50 to1.82 µg/g with increasing of TiO2 NPs concentration within 35 days, which was far lower than the regulation given by the European Food Safety Authority (maximum migration of TiO2 particles in food packaging materials was 10 mg/kg) (Tang et al., 2020). The FDA approved the use of TiO2 in foods as a color additive (E171) at levels up to 1% (Alizadeh-Sani, Mohammadian and McClements, 2020); however, titanium dioxide was only used as an additive in food contact plastics without specifying the migration amount but only the purity in GB 9685–2016. In addition, TiO2 was also commonly used as a sunscreen, whitening agent, and oil absorber in cosmetics. The value of TiO2 NPs in other simulated solutions was lower than the detection limit of the instrument, showing that the effect of the type of simulated solution on the migration of TiO2 NPs in composite films was significant. The swelling of nanocomposite materials in acetic acid solution and the reduced barrier properties of the materials enhance the migration of nanoparticles. However, due to the solvent resistance of the PEF material, the barrier formed by the ethanol solution on the membrane surface will prevent the further migration of the nanoparticles (Li et al., 2016). Hence, acidic food was more conducive than other simulation solutions, such as ethanol, water, and hexane.

For each sample, the amount of migration in acetic acid solution increased with time, but the dependence of the rate on concentration was not obvious. Since TiO2 NPs on the surface instead of the titanium inside the film of the PEF film would migrate to the solution, it could be seen that as the concentration of TiO2 nanoparticles increased, there might be more nanoparticles on the membrane surface. The migration of titanium increased first and then decreased with increasing concentration of TiO2 NPs, and a turning point occurred at PEF5,60,3, which might be due to agglomeration at high concentrations, inlaid in the polyester internal network structure and not easily migrating out. The migration amount of PEF5,60,1 became low (due to its low molecular weight results and higher crystallinity). The dispersion and agglomeration state of the nanoparticles were also demonstrated in Fig. 3. The results indicated that the migration of TiO2 NPs from the nanocomposite packaging into simulated solution was below the EU and FDA recommended limits.

4 Conclusion

In summary, PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites with excellent performance were successfully synthesized via one-pot polycondensation. The addition of 5‰ PMDA not only extended the chain of PEF but also enhanced its toughness. In these nanocomposites, TiO2 NPs were physically incorporated into the polymer matrix with homogeneous dispersion below 5‰. All PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites in the form of powder were amorphous. The Tgs with 60 nm TiO2 NPs (∼88 °C) were higher than that of pure PEF. However, nanocomposites with 30 nm and 100 nm TiO2 presented relatively lower Tg. The Td,5% and Tdmax of PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites increased with increasing addition percentage. Only 60 nm TiO2 could enhance the crystallization rate of nanocomposites. The crystallization rate increased first and then decreased with increasing TiO2 content of 60 nm. The t1/2 of PEF5,60,3 reached a minimum (6.16 min) and was less than that of pure PEF (18.2 min-40.3 min) at 160 ℃. As the 60 nm TiO2 content increased, the tensile modulus of the nanocomposites first increased and then decreased, and the impact strength increased. For PEF5,60,10, its impact strength was 52.2 × 103 J/m2, which was 25 times that of pure extended PEF (2.04 × 103 J/m2). Fortunately, all PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites maintained higher gas barrier properties than traditional packing materials. Meaningfully, due to the addition of TiO2 NPs, nanocomposites were endowed with excellent anti-ultraviolet, anti-blue-light and antibacterial functions. The migration rate of TiO2 NPs in water, ethanol, n-hexane and acetic acid solution was lower than the EU and FAD for standard packaging materials for food and cosmetics, and the maximum migration in acetic acid was 1.82 µg/g.

In conclusion, the one-pot polycondensation approach can be used to simultaneously achieve chain extension and nano composition. The successful preparation of PEF/TiO2 nanocomposites with anti-ultraviolet, anti-blue-light and antibacterial functions also has certain significance for expanding the application range of PEF. The results obtained in this study provide a basis for the continuation of research in the future, which will be related to the packaging application made from PEF of real food and cosmetics, they are likely to have higher requirements for the antibacterial and UV shielding properties of packaging materials to obtain longer storage times in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 52273098, 52073284).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Solid state polymerization of poly(ethylene furanoate) and its nanocomposites with SiO2 and TiO2. Macromol. Mater. Eng.. 2017;302

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eco-friendly active packaging consisting of nanostructured biopolymer matrix reinforced with TiO2 and essential oil: Application for preservation of refrigerated meat. Food Chem.. 2020;322:126782

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial food packaging based on sustainable bio-based materials for reducing foodborne pathogens: A review. Food Chem.. 2020;310:125915

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of nano TiO2 particles on the properties of carbon fiber-epoxy composites. Prog. Rubber Plast. Recycl. Technol.. 2020;37:216-232.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Injection stretch blow moulding process of reactive extruded recycled PET and virgin PET blends. Eur. Polym. J.. 2005;41:2614-2634.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Electrospun synthesis of silver/poly (vinyl alcohol) nano-fibers: Investigation of microstructure and antibacterial activity. Mater. Lett.. 2022;309

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on polymer network formation. Spectrosc. Lett.. 2017;50:522-527.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of micro-nano titania contents and maleic anhydride compatibilization on the mechanical performance of polylactide. Polym. Compos.. 2019;41:600-613.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Performance of polylactide against UV irradiation: Synergism of an organic UV absorber with micron and nano-sized TiO2. J. Compos. Mater.. 2020;54:2489-2504.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A facile synthesis for uniform tablet-like TiO2/C derived from Materials of Institut Lavoisier-125(Ti) (MIL-125(Ti)) and their enhanced visible light-driven photodegradation of tetracycline. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2020;571:275-284.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic effects of octahedral TiO2-MIL-101(Cr) with two heterojunctions for enhancing visible-light photocatalytic degradation of liquid tetracycline and gaseous toluene. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2020;579:37-49.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and crystallization behavior of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)/cellulose composites by twin screw extrusion. Carbohydr. Polym.. 2017;174:1026-1033.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Novel polylactic acid (PLA)-organoclay nanocomposite bio-packaging for the cosmetic industry; migration studies and in vitro assessment of the dermal toxicity of migration extracts. Polym. Degrad. Stab.. 2019;168

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of spherical and platelet-like nanoparticles on physical and mechanical properties of polyethylene terephthalate. J. Thermoplast. Compos. Mater.. 2013;27:1127-1138.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Transparent and flexible cellulose triacetate–TiO2 nanoparticles with conductive and UV-shielding properties. J. Phys. Chem. C. 2020;124:4242-4251.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrication of gelatin-TiO2 nanocomposite film and its structural, antibacterial and physical properties. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2016;84:153-160.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multifunctional UV-shielding nanocellulose films modified with halloysite nanotubes-zinc oxide nanohybrid. Cellul.. 2019;27:401-413.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toward biobased, biodegradable, and smart barrier packaging material: Modification of poly(Neopentyl Glycol 2,5-Furandicarboxylate) with succinic acid. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.. 2019;7:4255-4265.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cesium lead halide perovskite nanocrystals for ultraviolet and blue light blocking. Chin. Chem. Lett.. 2019;30:1021-1023.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Optical, vibrational and fluorescence recombination pathway properties of nano SiO2-PVA composite films. Opt. Mater.. 2019;90:139-144.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable lignin-based coatings doped with titanium dioxide nanocomposites exhibit synergistic microbicidal and UV-blocking performance toward personal protective equipment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.. 2021;9:11223-11237.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial effects of silver nanoparticles. Nanomedicine. 2007;3:95-101.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanostructured TiO2 sensitized with MoS2 nanoflowers for enhanced photodegradation efficiency toward Methyl Orange. ACS Omega. 2021;6:17071-17085.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Biobased poly(ethylene furanoate) polyester/TiO2 supported nanocomposites as effective photocatalysts for anti-inflammatory/analgesic drugs. Molecules. 2019;24

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Incorporating graphene nanoplatelets and carbon nanotubes in biobased poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate): Fillers’ effect on the matrix’s structure and lifetime. Polymers. 2023;15

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Study of the migration of stabilizer and plasticizer from polyethylene terephthalate into food simulants. J. Chromatogr. Sci.. 2016;54:939-951.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. H. K. T. S. K. G., 2006. Crystallization Characteristics Of Pet/TiO2 Nanocomposites. Materials Science: An Indian Journal. 2, 154-160.

- Nano-TiO2 particles and high hydrostatic pressure treatment for improving functionality of polyvinyl alcohol and chitosan composite films and nano-TiO2 migration from film matrix in food simulants. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol.. 2016;33:145-153.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Migration of copper from nanocopper/LDPE composite films. Food Addit. Contam. Part A Chem. Anal. Control Expo. Risk Assess.. 2016;33:1741-1749.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A perspective on PEF synthesis, properties, and end-life. Front. Chem.. 2020;8:585.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermal and structural response of in situ prepared biobased poly(ethylene 2,5-furan dicarboxylate) nanocomposites. Polymer. 2016;103:288-298.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanoparticle layer via UV-induced directional migration of iron-doped titania nanoparticles in polyvinyl butyral films and superior UV-stability. Polymer. 2022;254

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Preparation and properties of nanocomposites based on poly(lactic acid) and functionalized TiO2. Acta Mater.. 2009;57:3182-3191.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of TiO2 nanoparticles on the crystallization behaviour and tensile properties of biodegradable PLA and PCL nanocomposites. J. Polym. Environ.. 2017;26:2410-2423.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Influence of organically modified montmorillonite and sepiolite clays on the physical properties of bio-based poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) Compos. B Eng.. 2017;110:96-105.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Strain induced crystallization in biobased Poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) (PEF); conditions for appearance and microstructure analysis. Polymer. 2018;158:364-371.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antimicrobial activities of chitosan/titanium dioxide composites as a biological nanolayer for food preservation: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2021;176:530-539.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Use of nanoparticles as a potential antimicrobial for food packaging. Food Preserv. 2017:413-447.

- [Google Scholar]

- Isothermal crystallization kinetics of PET/alumina nanocomposites using distinct macrokinetic models. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim.. 2019;138:1049-1067.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal oxide nanoparticles for safe active and intelligent food packaging. Trends Food Sci. Technol.. 2021;116:655-668.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thermo-rheological analysis of various chain extended recycled poly(ethylene terephthalate) Polym. Eng. Sci.. 2020;60:2511-2516.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A step forward in thermoplastic polyesters: Understanding the crystallization and melting of biobased poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) (PEF) ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.. 2022;10:7050-7064.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Photosensitized TiO2 films on polymers-Titania-polymer interactions and visible light induced photoactivity. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2019;475:710-719.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Structure and catalytic activity of poly(Titanium Oxide) doped by gold nanoparticles in organic polymeric matrix. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym Mater.. 2016;26:1280-1291.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Polyethylene/graphene oxide composites toward multifunctional active packaging films. Compos. Sci. Technol.. 2019;184

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrication and characterization of chitosan-titanium dioxide nanocomposite film as ethylene scavenging and antimicrobial active food packaging. Food Hydrocoll.. 2018;84:125-134.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations for replacing PET on packaging, fiber, and film materials with biobased counterparts. Green Chem.. 2021;23:8795-8820.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Plastics from renewable sources as green and sustainable alternatives. Curr. Opin. Green Sustainable Chem.. 2022;33

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isothermal crystallization and structural characterization of poly(ethylene-2,5-furanoate) Polymer. 2015;72:165-176.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New insight into the mechanism for the excellent gas properties of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) (PEF): Role of furan ring’s polarity. Eur. Polym. J.. 2019;118:642-650.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isothermal crystallization of polypropylene/surface modified silica nanocomposites. Sci. China Chem.. 2016;59:1283-1290.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The performance changes and migration behavior of PLA/Nano-TiO2 composite film by high-pressure treatment in ethanol solution. Polymers (Basel).. 2020;12

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isothermal crystallization kinetics of poly (ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) Macromol. Mater. Eng.. 2015;300:466-474.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanocomposites of isotactic polypropylene with carbon nanoparticles exhibiting enhanced stiffness, thermal stability and gas barrier properties. Compos. Sci. Technol.. 2008;68:933-943.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of TiO2 nanoparticles on the physico-mechanical and ultraviolet light barrier properties of fish gelatin/agar bilayer film. LWT Food Sci. Technol.. 2016;71:88-95.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Modification of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) with 1,4-cyclohexanedimethylene: Influence of composition on mechanical and barrier properties. Polymer. 2016;103:1-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis of bio-based poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) copolyesters: Higher glass transition temperature, better transparency, and good barrier properties. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem.. 2017;55:3298-3307.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Copolyesters based on 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA): Effect of 2,2,4,4-Tetramethyl-1,3-Cyclobutanediol units on their properties. Polymers (Basel). 2017;9

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A novel ZnO/CQDs/PVDF piezoelectric system for efficiently degradation of antibiotics by using water flow energy in pipeline: Performance and mechanism. Nano Energy. 2023;107

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sustainable self-powered degradation of antibiotics using Fe3O4@MoS2/PVDF modified pipe with superior piezoelectric activity: Mechanism insight, toxicity assessment and energy consumption. Appl. Catal. B:Environ.. 2023;331

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Titania nanocrystal surface functionalization through silane chemistry for low temperature deposition on polymers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016;8:29759-29769.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ecofriendly UV-protective films based on poly(propylene carbonate) biocomposites filled with TiO2 decorated lignin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.. 2019;126:1030-1036.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In-situ synthesis, thermal and mechanical properties of biobased poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate)/montmorillonite (PEF/MMT) nanocomposites. Eur. Polym. J.. 2019;121

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Modification of poly(ethylene 2,5-furandicarboxylate) with aliphatic polycarbonate diols: 1. Randomnized copolymers with significantly improved ductility and high CO2 barrier performance. Eur. Polym. J.. 2020;134

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ultraflexible transparent bio-based polymer conductive films based on Ag nanowires. Small. 2019;15:e1805094.

- [Google Scholar]

- Transparent nanostructured BiVO4 double films with blue light shielding capabilities to prevent damage to ARPE-19 cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2020;12:20797-20805.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oxygen-vacancy-induced O2 activation and electron-hole migration enhance photothermal catalytic toluene oxidation. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci.. 2022;3

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Highly efficient photothermal catalysis of toluene over Co3O4/TiO2 p-n heterojunction: The crucial roles of interface defects and band structure. Appl. Catal. B:Environ.. 2022;315

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Development and evaluation of antimicrobial LDPE/TiO2 nanocomposites for food packaging applications. Polym. Bull.. 2022;80:5417-5431.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Novel biobased high toughness PBAT/PEF blends: morphology, thermal properties, crystal structures and mechanical properties. New J. Chem.. 2020;44:3112-3121.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effective strategies of sustained release and retention enhancement of essential oils in active food packaging films/coatings. Food Chem.. 2022;367:130671

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Titanium dioxide (TiO2) for the manufacture of multifunctional active food packaging films. Food Packag. Shelf Life. 2022;31

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bio-based polyesters: Recent progress and future prospects. Prog. Polym. Sci.. 2021;120

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The promoting effect of alkali metal and H2O on Mn-MOF derivatives for toluene oxidation: A combined experimental and theoretical investigation. J. Catal.. 2022;415:218-235.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Highly efficient visible-light-driven photocatalytic degradation of gaseous toluene by rutile-anatase TiO2@MIL-101 composite with two heterojunctions. J. Environ. Sci. 2022

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Renewable poly(butene 2, 5-furan dicarboxylate) nanocomposites constructed by TiO2 nanocubes: Synthesis, crystallization, and properties. Polym. Degrad. Stab.. 2021;189

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Titanium dioxide (TiO2) photocatalysis technology for nonthermal inactivation of microorganisms in foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol.. 2018;75:23-35.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zibaei, R., B. Ebrahimi, M. Rouhi, Z. Hashami, Z. Roshandel, S. Hasanvand, J. de Toledo Guimarães, M. goharifar & R. Mohammadi, 2023. Development of packaging based on PLA/POE/SeNPs nanocomposites by blown film extrusion method: Physicochemical, structural, morphological and antioxidant properties. Food Packaging and Shelf Life. 38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fpsl.2023.101104.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105228.

Appendix A

Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1