Translate this page into:

Efficient lead removal from aqueous solutions using a new sulfonated covalent organic framework: Synthesis, characterization, and adsorption performance

⁎Corresponding authors. m.dehghani@iauba.ac.ir (Mohsen Dehghani Ghanatghestani), Fa.Moeinpour@iau.ac.ir (Farid Moeinpour)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University. Production and hosting by Elsevier.

Abstract

The aim of removing Pb(II) from water is to minimize the potential harm posed by toxic metals to both human health and the environment. To achieve this, a covalent organic framework adsorbent called TFPOTDB-SO3H was developed using a condensation process involving 2,5-diaminobenzenesulfonic acid and 2,4,6-tris-(4-formylphenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine. This adsorbent exhibited excellent properties such as high repeatability, selectivity, and easy solid–liquid separation. Under conditions of pH = 6.0 and 298 K, the TFPOTDB-SO3H demonstrated impressive capability of adsorbing Pb(II). In a brief span of 10 min, it attained a special elimination rate of 99.40 % and shown its capacity to adsorb up to 500.00 mg/g. The adsorbent presented effective removal of Pb(II) from a solution that had a mixture of various ions, showcasing its proficiency in capturing the contaminant, with a partition coefficient (Kd) of 3.99 × 106 mL/g and an adsorption efficiency of 99.75 % among six coexisting ions. The pseudo-second-order kinetic model was observed to govern the adsorption process kinetics, while the Langmuir isotherm model confirmed monolayer chemisorption as the mechanism for Pb(II) removal. Thermodynamic analysis indicated that the uptake process was both exothermic and spontaneous. Furthermore, the adsorbent maintained a significant adsorption efficiency of 89.63 % for Pb(II) even after undergoing four consecutive adsorption–desorption cycles. These findings collectively suggest that TFPOTDB-SO3H has excellent potential for effectively adsorbing and removing Pb(II) heavy metal ions from wastewater.

Keywords

Covalent organic frameworks

Adsorption

Pb(II)

Removal

Aqueous solutions

1 Introduction

Water pollution is a pressing environmental concern that poses a significant threat to ecosystems and human health worldwide (Li et al., 2019). The accumulation of various pollutants, including heavy metals, organic dyes, and pharmaceutical compounds, in water bodies has necessitated the development of efficient and sustainable methods for their removal (Qasem et al., 2021). Lead ions in water sources pose significant disadvantages for humans and the environment. Firstly, lead exposure through drinking water can have detrimental health effects on humans. Numerous scientific studies have demonstrated that high levels of lead in the body can result in various neurological disorders, particularly in children. It can impede cognitive development, cause learning disabilities, and impact behavior and attention span (Lanphear et al., 2005). According to the World Health Organization and US Environmental Protection Agency guidelines, the maximum allowable concentration of lead in drinking water is 0.01 mg/L and 0.015 mg/L, respectively (Faust and Aly, 1998; Organization, 2004) . Numerous approaches have been devised over time to eliminate heavy metal ions, including methods like adsorption (Cui et al., 2019), reduction (Hai et al., 2013), and precipitation (Xiong et al., 2020). One of the methods that can be used to achieve this goal is adsorption, which involves the attachment of metal ions to the surface of solid materials. Adsorption has several advantages over other methods, such as low cost, high efficiency, easy operation, and strong applicability (Barakat, 2011; Anderson et al., 2022; Chakraborty et al., 2022) . Traditional adsorbents such as zeolites (Yang et al., 2020), aluminosilicate minerals (Zha et al., 2018), clays (Uddin, 2017), polymers (Zhao et al., 2018), activated carbons (Nayak et al., 2017) and metal oxides (Lingamdinne et al., 2017), are widely utilized in the water treatment sector. However, these adsorbents have limitations such as small pore size, irregular surface structure, limited surface area, and chemical bonds that negatively impact their adsorption process. Therefore, it’s crucial to investigate the development of new adsorbents with high porosity, large surface area, and specific adsorption sites for effective heavy metal removal. To address these limitations, various types of nanomaterials have been developed and investigated as potential adsorbents for heavy metal removal, such as zero-valent metals (Di et al., 2023), carbon-based materials (Krishna et al., 2023), and nanocomposites (Wang et al., 2015; Omidvar-Hosseini and Moeinpour, 2016; Wang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2021; Lakkaboyana et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Vijitha et al., 2021; Vijitha et al., 2021; Palani et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Zandi-Mehri et al., 2022; El Mouden et al., 2023; Qiu et al., 2023) . However, some nano absorbents have low stability in water, are toxic, and expensive, and in some cases, their recovery capability is ineffective (Gendy et al., 2021). Therefore, to overcome these limitations, COFs have been designed with significant surface area and porosity to increase their adsorption capacity. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are a class of crystalline materials with a porous structure composed of organic components connected via strong covalent bonds. (Wang and Zhuang, 2019). COFs demonstrate strong resistance to chemical alteration in both aqueous and organic environments, which sets them apart from metal-organic frameworks that tend to be unstable when subjected to moisture and aqueous conditions (Feng et al., 2012; Kandambeth et al., 2012) . Their unique structural characteristics, such as tunable pore size, high surface area, and exceptional stability, make them highly attractive for applications in water purification (Smith and Dichtel, 2014; Dinari and Hatami, 2019; Tang et al., 2022; Khojastehnezhad et al., 2023) . COFs can be tailored and functionalized at the molecular level, allowing for precise control over their physicochemical properties to enhance pollutant removal efficiency and wastewater treatment (Huang et al., 2020; Gan et al., 2022; Li et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2022; Zhu et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2023) . In the realm of separation science, the use of COFs has primarily relied on their inherent hydrophobic properties and π–π stacking interactions. However, introducing of functional groups into the COF structure can greatly enhance both the selectivity of extraction and the efficiency of adsorption. For instance, Li and his team created a sulfonate functionalized COF composite (referred to as Fe3O4@COF(TpBD)@Au-MPS nanocomposites) specifically for the capture of fluoroquinolones (Wen et al., 2020). Similarly, Zhao and his team developed a sorbent with sulfonic acid functionality (known as Ni/CTF-SO3H) by modifying a triazine-based COF substrate post-synthesis, which was then used for selective enrichment of carbendazim and thiabendazole in various fruits, vegetables, and juices (Zhao et al., 2020). Despite the success of these post-synthetic modification strategies in enhancing selectivity, they involve a lengthy and complex preparation process for the sorbent. As such, designing and preparing COFs with inherent functional groups can simplify the sorbent preparation procedure. Hence, by integrating functional components into their structures, these materials exhibit substantial potential as adsorbents for investigating the effectiveness of metal ion removal from water solutions.

In this study, a porous COF called TFPOTDB-SO3H was synthesized using a rational design approach. The COF contained sulfonic acid groups, N and O atoms that contributed to its exceptional performance in removing Pb(II) ions efficiently. To create the TFPOTDB-SO3H, a flexible binding block and a monomer derived from triazine were employed, leading to a network structure with high resonance upon polymerization. This unique structure allowed easy interaction between the lone pair electrons and Pb(II) ions.

2 Experimental

2.1 Materials

The chemicals used in the experiment were obtained from commercial sources without any additional processing. The specific chemicals and their respective suppliers were as follows: p-phenylenediaminesulfonic acid (DB-SO3H) from Sigma-Aldrich (purity ≥ 97.0 %), glacial acetic acid from Sigma-Aldrich (purity ≥ 99 %), 1,4-dioxane from Merck, ethanol from Alfa Aesar (purity 94–96 %), acetone from Alfa Aesar (purity 99.5 %), and nitric acid from Alfa Aesar. Cyanuric chloride and p-hydroxybenzaldehyde were purchased from Merck. The preparations of all solutions were carried out utilizing deionized water. The lead solution, which had a concentration of 1000 mg/L, was acquired from Merck as the standard solution and diluted as required. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and nitric acid (HNO3) with a concentration of 0.1 mol/L were used to adjust the solution's pH as needed.

2.2 Material characterization

The experimental analysis of the sample utilized a range of analytical techniques. The HITACHI, S-4160 scanning electron microscope was used to conduct scanning electron microscopy (SEM). For transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis, the Philips CM 120 microscope was employed. To obtain ATR-FTIR (Fourier transform infrared) spectra, the Thermo Nicolet 370 instrument from Thermo Fisher in the USA was utilized, with measurements taken in the 400–4000 cm−1 range, employing an average of 64 scans and a resolution of 4 cm−1. The Micromeritics TriStar II Series, GA 30093 instrument from the USA was utilized to evaluate the surface area and pore size distribution, where N2 gas served as the adsorbate, and measurements were carried out at 77 K. The process of thermogravimetry analysis (TGA) involved subjecting the sample to a gradual increase in temperature, starting from room temperature and reaching 800 °C. This temperature increment occurred at 10 °C per minute, and the experiment was conducted under an N2 atmosphere. The STA503 TA instrument was utilized for this procedure. The CuKα radiation and a Bruker instrument from Germany were used to obtain powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns in the 2-80° range. Ultimately, the measurement of Pb(II) ions was successfully carried out using flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry (FAAS). This method employed the PerkinElmer 2380-Waltham instrument, which was fitted with a hollow cathode lamp specific to Pb(II).

2.3 Synthesis and purification of 2,4,6-Tris-(4-Formylphenoxy)-1,3,5-Triazine (TFPOT)

Initially, p-hydroxybenzaldehyde (14.64 mmol, 1800 mg) and NaOH (14.64 mmol, 585 mg) were dissolved in a round bottom flask containing a mixture of acetone and water (30 mL, v/v = 1:1). The flask was then cooled to 0 °C using an ice bath. Subsequently, cyanuric chloride (4.88 mmol, 900 mg) dissolved in acetone (15 mL) was slowly added to the solution over 60 min, resulting in the formation of a white solid. The reaction proceeded for 12 h at room temperature. Once the reaction was complete, the white solid was filtered, thoroughly washed with water, and recrystallized using ethanol. Finally, the product was dried in a vacuum oven at 80 °C, resulting in a pure final product with a yield of 92 % in the form of a white solid (Dutta and Patra, 2021).

2.4 Synthesis method to produce sulfonate-COF (TFPOTDB-SO3H)

A solvothermal reaction was employed to synthesize a sulfonated covalent organic framework (TFPOTDB-SO3H). In the process, a mixture of TFPOT (132.42 mg, 0.3 mmol), DB-SO3H (85 mg, 0.45 mmol), 1,4-dioxane (20 mL), and aqueous acetic acid (3 M, 2 mL) was prepared by ultrasonication (80 W, 15 min) to achieve a uniform dispersion. This mixture was then transferred to an autoclave and heated at 120 °C for 72 h. The resulting solid, colored dark red-brown, was subsequently washed with ethanol, water, and ethanol in sequential order, followed by drying at 50 °C under vacuum conditions for 12 h with an impressive yield of 78 % (Krishnaveni, 2023).

2.5 Batch adsorption experiments

The 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask was utilized for performing the adsorption experiments. The flask contained varying specific amounts of TFPOTDB-SO3H and initial concentrations of metal ions, and the experiments were carried out at different times under non-continuous conditions. For the experiments involving Pb(II), solutions with desired concentrations were prepared by diluting a 1000 ppm Pb(II) solution. The removal procedures were studied to determine the optimal conditions by investigating the effects of pH (ranging from 2 to 7) and time (from 0.5 to 60 min). The initial concentration of Pb(II) ranged from 5.0 to 200 mg/L, while the adsorbent dosage was between 1.0 and 100 mg/100 mL. After achieving adsorption equilibrium, the mixture was filtered to separate the adsorbent, and the remaining filtrate was analyzed using FAAS. Each experiment was repeated three times to ensure accuracy and reliability. The equations provided below were used to calculate the removal efficiency (Removal (%)) and equilibrium adsorption capacity (qe) for Pb(II):

In these equations, C0 represents the initial concentration of the Pb(II) in the solution (measured in mg/L). The amount of Pb(II) adsorbed by the adsorbent at equilibrium is denoted as qe (measured in mg/g), and Ce refers to the residual concentration of the Pb(II) in the solution at equilibrium (measured in mg/L). The mass of the adsorbent is represented by the variable m (measured in grams), while V denotes the volume of the Pb(II) solution (L).

2.6 A step-by-step approach for the selective adsorption of Pb(II)

A standard approach was followed to adsorb Pb(II) ions selectively. A 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask held a 50-mL water-based solution consisting of Pb(NO3)2, Zn(NO3)2, Fe(NO3)3, Cd(NO3)2, Ni(NO3)2, Mn(NO3)2, and Co(NO3)2. Each substance was present at a concentration of 10 ppm and maintained at pH 6 using a buffer solution. To this mixture, 10.0 mg of TFPOTDB-SO3H was added, forming a slurry. The mixture was agitated for 10 min at ambient temperature. Following that, the mixture underwent filtration to separate the adsorbent. The resulting filtrate was subjected to FAAS analysis to determine its composition.

2.7 A general recycling procedure

To begin with, a 250 mL Erlenmeyer flask was utilized and filled with 10.0 mg of TFPOTDB-SO3H. Then, a solution containing Pb(NO3)2 with a concentration of 10 ppm (50 mL) was added to the flask. The resulting mixture underwent stirring at room temperature for 10 min. Subsequently, it was filtered using filter paper and rinsed with 50 mL of water. To regenerate the TFPOTDB-SO3H sample, it was stirred in a 0.1 M EDTA solution (50 mL) for 30 min, followed by filtration and washing with 20 mL of water. This regenerated TFPOTDB-SO3H was then ready for use in subsequent cycles.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis of TFPOTDB-SO3H

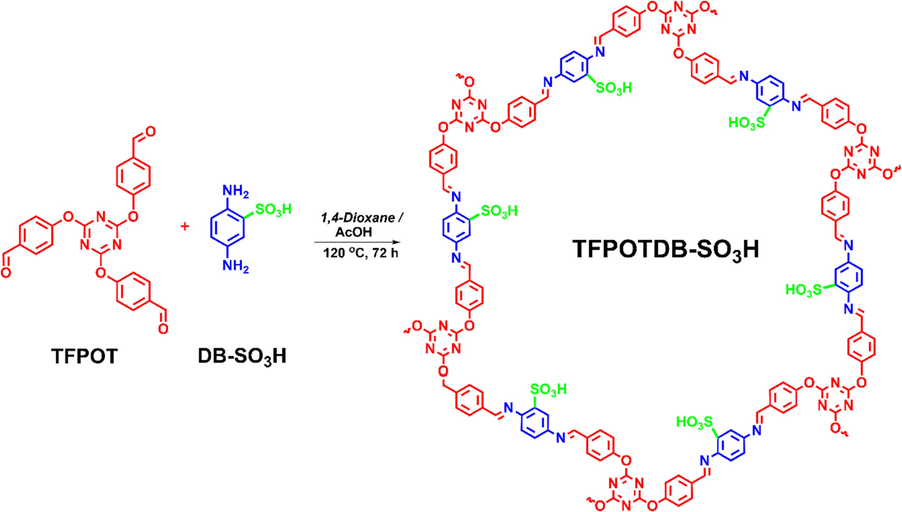

The solvothermal technique was utilized to create a sulfonated covalent organic framework. This involved the combination of p-phenylenediaminesulfonic acid (DB-SO3H) and 2,4,6-tris-(4-formylphenoxy)-1,3,5-triazine (TFPOT) with the presence of a 3 M acetic acid catalyst. This reaction took place at 120 °C for 72 h in 1,4-dioxane. Initially, an intermediate enol-imine form with unstable imine bonds was generated through a reversible Schiff base reaction between aldehyde and amino components. The synthesis process is more straightforward and user-friendly than traditional vacuum solvothermal conditions (Scheme 1).

A comprehensive method for synthesizing TFPOTDB-SO3H.

3.2 PXRD, FT-IR, BET, and TGA analyses

The TFPOTDB-SO3H adsorbent was synthesized and obtained as a solid material with a dark red-brown color. To confirm its crystalline structure, the PXRD technique was employed. Figs. S1a illustrates the PXRD spectrum specifically for TFPOTDB-SO3H. Within this spectrum, distinct peaks are observed at 4.4°, 8.1°, and 25°, corresponding to the facets 100, 110, and 001, respectively. These peaks signify the presence of ordered structures of TFPOTDB-SO3H within the covalent organic framework, which extends along the COF layers' π-π stacking arrangement. The main peak at 4.4° displays the highly ordered hexagonal structure of synthesized TFPOTDB-SO3H COF (Xu et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2017) . The peak associated with facet 001 in the PXRD spectrum further supports this observation (Jeong et al., 2019). As can be found in Figs. S1a, the experimental PXRD pattern of the TFPOTDB-SO3H is in a good match with the simulated pattern. Furthermore, the FT-IR spectroscopy analysis of TFPOTDB-SO3H (as depicted in Figs. S1b) corroborated the structure determined through PXRD. The FT-IR spectrum of the COF material exhibited the absence of adsorption peaks associated with the amine functional group of DB-SO3H and the carbonyl functional group of TFPOT at approximately 3400 and 1700 cm−1, respectively. Conversely, a distinctive peak at 1005 cm−1 indicated the presence of -SO3H groups by demonstrating the stretching band of O = S = O. Additionally, the emergence of a new peak at 1621 cm−1 confirmed the successful synthesis of the COF by denoting the occurrence of the imine condensation reaction. These observations collectively suggest the successful synthesis of the framework material (Pachfule et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2020) . The investigation proceeded to examine the porosity of the porous material through N2 sorption measurements conducted at a temperature of 77 K. The obtained results, depicted in Figs. S1c, exhibited type I sorption isotherms. Calculations based on the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) formula determined a surface area of 190.73 m2/g. Furthermore, employing the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) technique, the average pore diameter and pore volume were estimated from the adsorption branches. The outcomes revealed values of approximately 2.5 nm for pore diameter and 1.55 cm3/g for pore volume. Ensuring the stability of the adsorbent is a crucial aspect when it comes to its practical use. Thermal stability of a composite can be confirmed by looking at the TGA thermogram curve. If the curve is flat and shows no change in weight over a certain temperature range, then it can be said that the composite is thermally stable. If the curve shows a decrease in weight with increasing temperature, then it can be said that the composite is not thermally stable. As can be seen in Figs. S1d, TFPOTDB-SO3H is stable until 280 °C and it indicated 100 % weight loss at around 600 °C.

3.3 Examining SEM and TEM data

Figs. S2(a, b) present SEM and TEM images of TFPOTDB-SO3H, respectively. The SEM image suggests that the structure of the COF is composed of Spherical particles that are somewhat stuck together. Additionally, the TEM image displays a flake and layered configuration likely due to hydrogen bonding between layers. The analysis using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) is depicted in Figs. S2c, revealing the presence of sulfur in the COF called TFPOTDB-SO3H. The image provides evidence of this. Additionally, it was determined that the percentage of sulfur in TFPOTDB-SO3H is 12.72 %.

3.4 Lead removal

Before conducting the adsorption experiments, the stability of TFPOTDB-SO3H in water was assessed using PXRD. By comparing the PXRD patterns of TFPOTDB-SO3H samples before and after being immersed in water, HCl (1 M) and NaOH (1 M) solutions for 24 h, it was observed that the crystallinity of both immersed TFPOTDB-SO3H and TFPOTDB-SO3H remained intact. This observation confirmed the water, acid, and base stability of the compounds (Fig. S3).

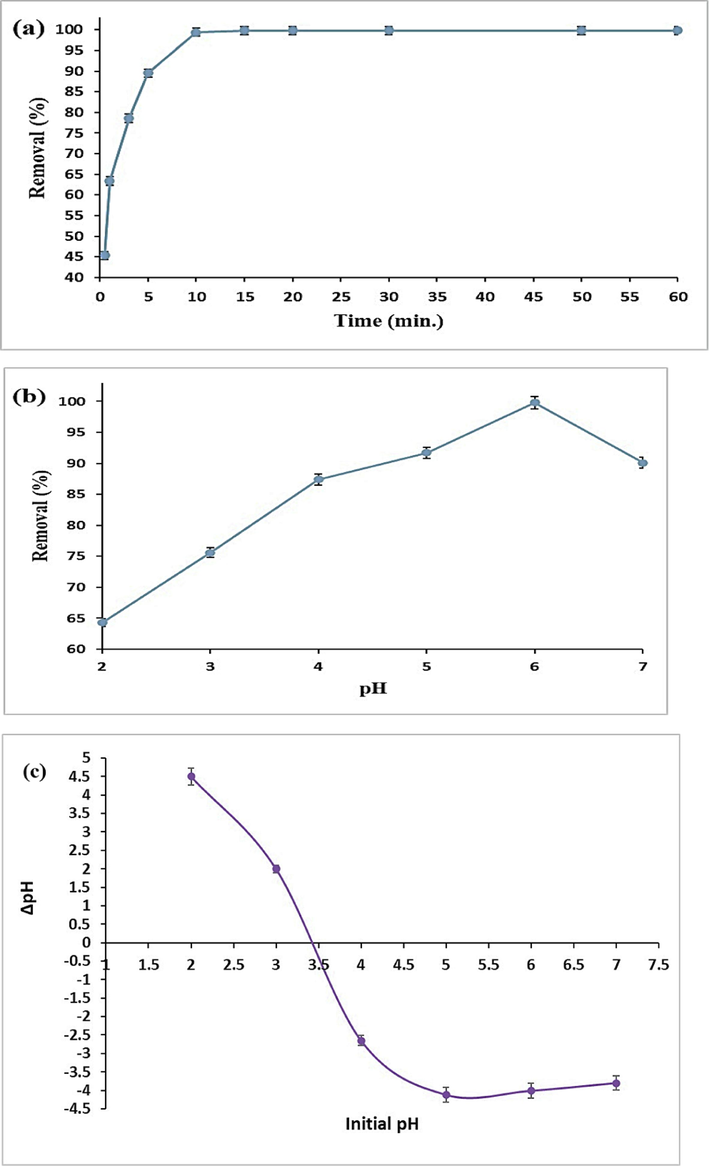

The TFPOTDB-SO3H product was utilized to examine the influence of contact duration on the adsorption process of Pb(II) (Fig. 1a). The swift uptake of Pb(II) took place during the initial adsorption phase, reaching equilibrium within 10 min. After this time, no further enhancement in Pb(II) adsorption was observed. The rapid early-stage adsorption of Pb(II) is due to the availability of numerous open surface sites on the TFPOTDB-SO3H material. The efficient removal of Pb(II) heavily relies on the pH level's significant involvement. A crucial point to consider is that when the pH reaches 6 or higher, a considerable amount of the overall lead content forms into Pb(OH)2 and becomes unadsorbable. Therefore, the pH range of 1.0 to 7.0 was selected for this study. Fig. 1b illustrates the effect of pH on the removal of Pb(II) ions by TFPOTDB-SO3H. The findings suggest that the adsorption of lead is affected by pH levels and can be influenced by the presence of various forms of lead at different pH levels. When the pH level is 2.0, Pb(II) takes the form of Pb+2 ions. This creates a situation where Pb+2 and H+ ions compete for the binding spots on TFPOTDB-SO3H, resulting in reduced absorption of Pb+2 ions. In the pH range of 2.0 to 6.0, the adsorption of lead increased linearly. This was primarily attributed to the creation of additional Pb(II) compounds like Pb(OH)+ and Pb2(OH)3+. When the pH level exceeds 6.0, lead ions undergo a chemical reaction to form lead hydroxide (Pb(OH)2), resulting in a reduction in the ability of lead to be adsorbed (Singh and Bhateria, 2020). The highest elimination effectiveness of 99.8 % was attained when the pH level was adjusted to 6.0, identified as the most favorable pH condition for TFPOTDB-SO3H in this study. To gain insights into the interaction between the adsorbent and Pb(II), the surface charge density of TFPOTDB-SO3H was determined by employing the point of zero charge (PZC) measurement method. Generally, when the pH is lower than the PZC, the surface of the adsorbent becomes positively charged. This leads to electrostatic repulsion between the adsorbent and Pb(II) ions that carry a positive charge. On the other hand, if the pH surpasses the PZC, there is a phenomenon of electrostatic attraction caused by the presence of opposite charges between the adsorbent and the metal cation. According to Fig. 1c, the PZC of the adsorbent is 3.42, indicating a positively charged surface at pH values below this threshold. The pH range of 3–7 promotes the attraction between the adsorbent and Pb(II) ions, aiding their adsorption. It is essential to highlight that the removal rate of Pb(II) surpasses 75 % under these conditions. The versatility of this adsorbent across various pH ranges suggests its potential utility in complex environments in the future.

Pb(II) removal efficiency of TFPOTDB-SO3H: time-dependent investigation (a), pH-dependent evaluation (b), Determination of pHPZC for TFPOTDB-SO3H (c), Impact of adsorbent dosage on Pb(II) removal (d), Influence of initial Pb(II) concentrations on TFPOTDB-SO3H performance (e), TFPOTDB-SO3H Recycling using 0.1 M EDTA solution (f) and PXRD patterns of fresh TFPOTDB-SO3H and recycled one (g).

Pb(II) removal efficiency of TFPOTDB-SO3H: time-dependent investigation (a), pH-dependent evaluation (b), Determination of pHPZC for TFPOTDB-SO3H (c), Impact of adsorbent dosage on Pb(II) removal (d), Influence of initial Pb(II) concentrations on TFPOTDB-SO3H performance (e), TFPOTDB-SO3H Recycling using 0.1 M EDTA solution (f) and PXRD patterns of fresh TFPOTDB-SO3H and recycled one (g).

Various experiments were carried out utilizing varying quantities of TFPOTDB-SO3H, varying from 1.0 to 100 mg/100 mL, to optimize the dosage of the adsorbent (Fig. 1d). It was observed that increasing the quantity of TFPOTDB-SO3H led to a corresponding increase in the uptake of Pb(II), as more binding sites became available for the Pb(II) ions. A dosage of only 10 mg/100 mL of TFPOTDB-SO3H was sufficient to eliminate 99.56 % of the Pb(II) ions. The fraction of removed Pb(II) ions was not significantly impacted by further increases in dosage. The researchers examined the absorption of Pb(II) by TFPOTDB-SO3H at various levels of Pb(II) ions (ranging from 5 to 200 mg/L). The time, pH, and amount of adsorbent used remained constant at 10 min, 6.0, and 10 mg/100 mL, respectively. The research findings indicated that when the Pb(II) concentration was raised from 5 to 200 mg/L, there was a noticeable decline in the efficiency of Pb(II) absorption, with the rate decreasing from 99.8 % to 69.9 % (Fig. 1e). This decrease in adsorption can be attributed to the limited availability of adsorption sites on the surface of TFPOTDB-SO3H due to the higher concentration of Pb(II) ions.

To make adsorption more cost-effective for practical purposes, it is necessary to reduce the expenses by desorbing the adsorbed Pb(II) from TFPOTDB-SO3H and regenerating it. It has been observed that the most effective desorption occurred in a solution of 0.1 M EDTA. After undergoing four cycles of reuse, the adsorbent only experienced a slight decrease of 10.1 % in its removal efficiency percent, indicating its excellent regenerative capability (Fig. 1f). As seen in Fig. 1g, the XRD pattern of the recovered TFPOTDB-SO3H is not much different from the fresh one. This indicates that the structure of the catalyst was stable after recovery.

Consequently, TFPOTDB-SO3H is regarded as an efficient and economical adsorbent for removing Pb(II) from contaminated wastewater.

3.5 Lead adsorption kinetics

Various kinetic models, including the pseudo-first-order model (Eq. (3)), pseudo-second-order model (Eq. (4)) and Elovich model (Eq. (5)) were utilized to understand the kinetics of the adsorption process. The equations representing these models are as follows:

Ln(qe – qt) = lnqe – k1t (3)

The pseudo-first-order model involves variables such as qe (mg/g) and qt (mg/g), which indicate the adsorption capacity of metal ions at equilibrium and time t (min), respectively. The rate constant for the pseudo-first-order reaction, denoted as k1 (min−1), determines the speed of the reaction.

In the context of the pseudo-second-order model, the quantities qe (mg/g) and qt (mg/g) denote the equilibrium and time-dependent adsorption capacity of metal ions, respectively. The rate constant for the pseudo-second-order reaction is characterized as k2 (g mg−1 min−1). In the Elovich model, α (mg g−1 min−1) and β (g mg−1) represent the initial adsorption rate and a constant providing information on the level of surface coverage.

One can choose the most appropriate kinetic model for the experimental data by considering the correlation index (R2) and the calculated uptake capacity (qe,cal). The results of the fitting analysis are presented in Table S1 and Fig. S4. After analyzing Table S1, it was concluded that the pseudo-first- and pseudo-second-order kinetic models yielded higher R2 values (0.9828 and 0.9999, respectively) compared to the Elovich model (0.8756). Additionally, the pseudo-second-order model displayed a qe,cal value that matched the qe,exp value in Table S1. Based on the results, it can be concluded that the pseudo-second-order model provides the best fit for describing the adsorption process. This suggests that chemisorption, involving ion exchange and coordination between metal ions and sorbent, may be the rate-limiting step in the adsorption of metal ions onto TFPOTDB-SO3H. The outcomes as a whole align with prior research findings (Dinari and Hatami, 2019; Wang et al., 2023) .

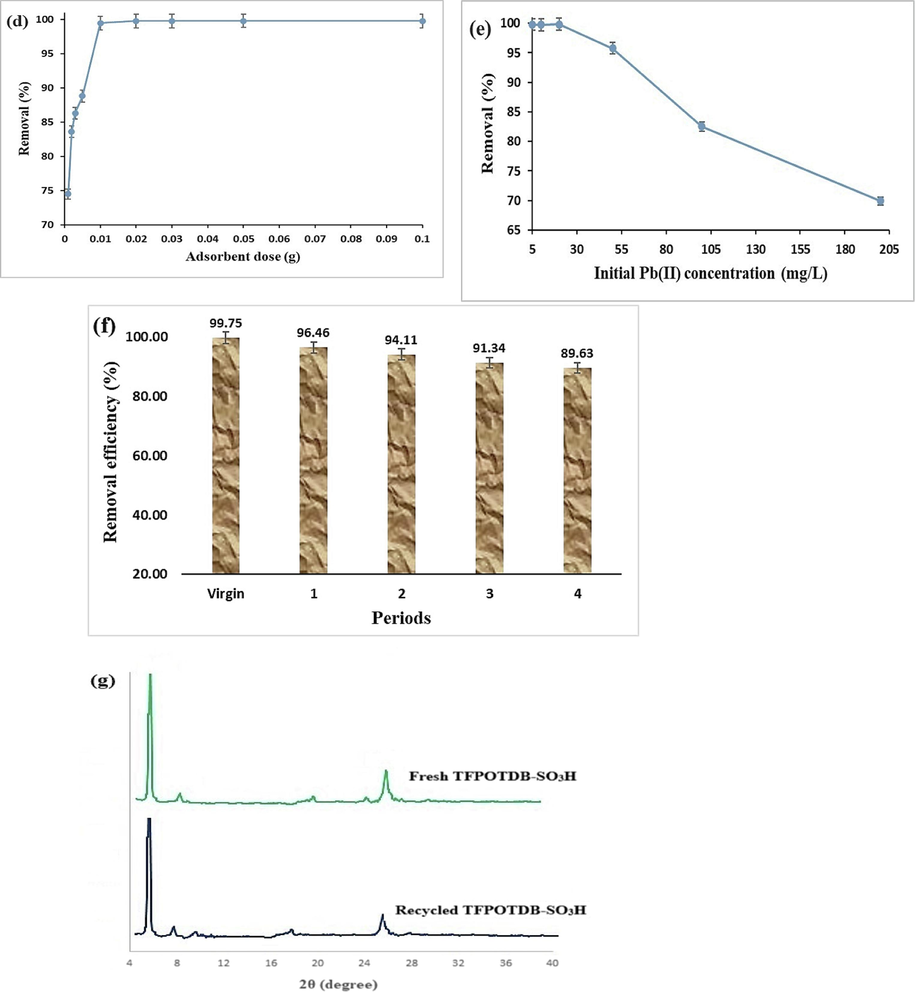

3.6 Lead adsorption isotherms

The equilibrium distribution of adsorbate molecules between the solid and liquid phases can be assessed by conducting adsorption isotherm studies. In this study, the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin isotherm models were employed to analyze the results obtained from the isotherm experiments (Fig. 2). The equations (6) to (8) represent the linear forms of the Langmuir, Freundlich and Temkin adsorption isotherm equations, respectively:

Linearized plots of isotherms models Langmuir (a), Freundlich (b), and Temkin (c) for Pb(II) adsorption on TFPOTDB-SO3H.

Langmuir

Freundlich

Temkin

T (K)

qm (mg/g)

KL (L/mg)

RLa range

R2

KF [(mg/g)(L/mg)1/n]

n

R2

AT (L/g)

bT (J/mol)

R2

298

500.00

2.857

0.0654–0.0017

0.961

356.533

3.005

0.931

88.280

18.604

0.895

308

181.82

7.856

0.0248–0.0006

0.975

159.247

1.871

0.967

3.921

12.649

0.944

323

51.28

24.375

0.0081–0.0002

0.992

60.576

1.476

0.974

0.903

12.600

0.949

3.7 Pb(II) adsorption thermodynamics

The influence of temperature on the adsorbent's ability to adsorb is observable. The uptake of Pb(II) ion onto the TFPOTDB-SO3H was investigated at different temperatures ranging from 298 to 323 K. A correlation was noticed wherein higher temperatures led to a decrease in adsorption, suggesting the occurrence of an exothermic adsorption phenomenon, which aligns with previous findings (Tang et al., 2021; Zandi-Mehri et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023) (Fig. S5). To evaluate the possibility and comprehend the adsorption procedure, an analysis was conducted on the thermodynamic parameters ΔG (change in free energy), ΔH (change in enthalpy), and ΔS (change in entropy). The determination of ΔH and ΔS involved calculating their values by analyzing the slopes and intercepts derived from the graphical representations of ln Kc versus 1/T (Fig. S6), employing the following equations.

The thermodynamic constant Kc (L/mg) is determined by qe/Ce, with R (8.314 kJ/mol.K) being the gas constant and T (K) the absolute temperature. Table S2 provides the amounts of ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS for Pb(II) uptake onto the adsorbent. The adsorption process is characterized as exothermic due to a negative ΔH value. The findings align with previous research, indicating that as the solution temperature increased, there was a decrease in the percentage of Pb(II) removal achieved by utilizing phenylthiosemicarbazide-functionalized UiO-66-NH2 (Tang et al., 2021). The ΔH value provides exciting information about the type of adsorption process. Table S2 shows that the adsorption of Pb(II) onto TFPOTDB-SO3H has an ΔH value of −122.149 kJ/mol, indicating a certain percentage of chemical adsorption (Okoli et al., 2019). Additionally, the negative ΔG values suggest that the adsorption process is spontaneous and feasible within the studied temperature range. The negative ΔG also suggests that the binding energy between the lead-adsorbent is stronger than that between lead-solvent, which drives the redistribution of Pb(II) cations in the system and leads to the spontaneous adsorption of lead on TFPOTDB-SO3H (Sprynskyy, 2009). As temperatures rise, the mobility of Pb(II) ions increases, causing them to move from the solid phase to the liquid phase. This results in a decrease in the amount of Pb(II) ions adsorbed; this is reflected by negative values of entropy change (Aravindhan et al., 2007). In comparison, pure ion exchange processes involve lead in solution being replaced with either a divalent ion like Ca2+ or two monovalent ions such as K+ or Na+. However, negative entropy change values suggest that chemisorption due to complex formation is more effective for removing Pb(II) than ion exchange (Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh and Kabiri-Samani, 2013).

3.8 Examining the lead adsorption selectivity

In practical scenarios, the presence of other metal ions poses a significant challenge to the adsorption performance of the adsorbent. To address this issue, we conducted a competitive experiment using TFPOTDB-SO3H to quantify the adsorption of Pb(II) in the presence of other metal ions. We employed TFPOTDB-SO3H to selectively adsorb a mixed solution containing ions at equal concentrations ([Co(II), Fe(III), Cd(II), Zn(II), Mn(II), Ni(II), Ca2+, Mg2+ and Pb(II) (10 mg/L)]), and anions (chloride, sulfate, nitrate, and bicarbonate (100 mg/L)) followed filtration and analysis of the cation contents using FAAS. The results in Fig. S7 demonstrate that within 10 min, TFPOTDB-SO3H effectively adsorbs Pb(II) with a removal rate exceeding 99.75 %, while the removal rate for other metal ions remains below 17 %. Also, the amount of Pb(II) removal in the presence of chloride, sulfate, nitrate and bicarbonate anions was equal to 98.50 %, 98.30 %, 99.30 % and 98.6 % respectively. These findings unequivocally indicate minimal competition from other metal ions and anions. Determining the distribution coefficient (Kd) is a crucial method for assessing the affinity of a sorbent towards a specific metal ion. The Kd can be calculated using the equation Kd = (C0-Ce) V/Ce m, where C0 denotes the initial concentration of ions, Ce represents the concentration of ions at equilibrium, V signifies the volume of the solution in milliliters, and m indicates the mass of the adsorbent in grams. The Kd value is a significant performance indicator for the adsorption of metal ions and adsorbent. Typically, a Kd value of 1.0 × 105 mL/g is considered highly favorable (Huang et al., 2017). In this study, the researchers utilized Kd to investigate the binding strength between TFPOTDB-SO3H and Pb(II). Table S3 presents a higher Kd value for Pb(II), indicating its preferential binding to TFPOTDB-SO3H. This suggests that Pb(II) has a greater tendency to displace other metal ions from the active sites on TFPOTDB-SO3H. These findings indicate that TFPOTDB-SO3H exhibits a strong preference and high selectivity when sorbing Pb2+. The exceptional selectivity can be attributed to the following factors: (1) the abundant sulfonic acid groups and N, O atoms in TFPOTDB-SO3H foster robust interactions with Pb2+; (2) in general, adsorbents tend to selectively adsorb cations with lower hydration energies, as the metal ions need to shed a significant amount of hydrated water before entering the narrower channels of the adsorbents (Marcus, 1991; Eren et al., 2009; Du et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2014)). This is supported by a comparison of Gibbs free energy of hydration values: Ca2+ (1683.6 kJ/mol), Mg2+ (2046.4 kJ/mol), Ni2+ (2482 kJ/mol), Fe3+ (4309.5 kJ/mol), Zn2+ (2047.6 kJ/mol), Mn2+ (1904.1 kJ/mol), Co2+ (2035.9 kJ/mol), Cd2+ (1755 kJ/mol), and Pb2+ (1425 kJ/mol) (Moon and Jhon, 1986). Pb2+ exhibits the lowest energy, indicating a higher tendency for preferential adsorption compared to other cations (Marcus, 1991; (3) studies have shown that larger ionic radius facilitates interactions between metal ions and functional groups of the adsorbent (Lau et al., 1999; Low et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2013) . The radius of Ca2+, Mg2+, Ni2+, Fe3+, Zn2+, Mn2+, Co2+, and Cd2+ are 0.100 nm, 0.072 nm, 0.069 nm, 0.055 nm, 0.074 nm, 0.067 nm, 0.065 nm, and 0.095 nm, respectively, while Pb2+ has a radius of 0.119 nm. The larger radius makes TFPOTDB-SO3H highly selective for Pb2+ adsorption. Also, the findings revealed that anions had no considerable effect on the adsorption of Pb2+ in the experimental conditions (Fig. S7).

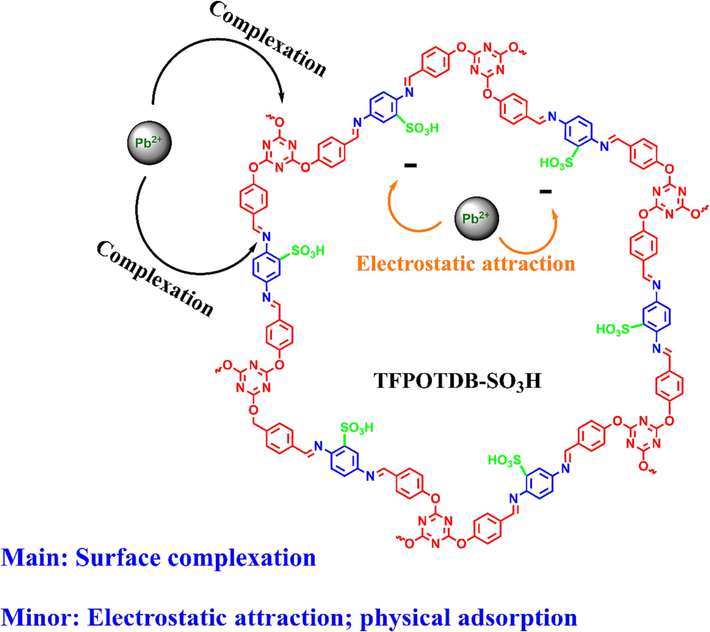

3.9 Lead adsorption and desorption mechanism

Scheme 2 presents a proposed mechanism for the attachment and release of Pb(II) ions onto TFPOTDB-SO3H. The results obtained from various analyses (including XRD, BET, FT-IR, pHpzc, and batch adsorption) led to the proposition of a plausible adsorption mechanism. Specifically, for the adsorption of mono-component Pb2+, it was determined that the adsorption mechanism on TFPOTDB-SO3H involved a combination of physical adsorption, electrostatic interaction, and surface complexation. The SEM and BET information revealed the presence of abundant mesopores with large pore volume and size, which facilitated the removal of Pb2+ ions by providing mass transfer pathways and adsorption domains (Hou et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019) . Some ions diffused into the pores and deposited on the surface of TFPOTDB-SO3H. Additionally, electrostatic interaction occurred between positively charged Pb2+ and negatively charged TFPOTDB-SO3H at pH 6, although its contribution was considered secondary (Song et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2019) . Therefore, the primary adsorption mechanism was identified as surface complexation, whereby the positively charged Pb2+ interacted with negatively charged surface-active sites on TFPOTDB-SO3H via electrostatic attraction. The sulfonyl groups on TFPOTDB-SO3H served as sites for Pb2+ removal, where coordination with O and N atoms occurred (Deng et al., 2019). The surface complexation involving Pb2+ and surface N and O atoms proceeded simultaneously, with lone pair electrons playing a pivotal role in complex formation (Chen et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2019) . The N and O atoms, known for their strong tendency to donate lone pair electrons, exhibited high bonding capacity for capturing Pb2+. Overall, the multifunctional groups and unique structure of TFPOTDB-SO3H were crucial in the comprehensive adsorption mechanism for Pb2+ in complex environments. As a result of electrostatic attraction, these groups became connected to the Pb(II) ion. By utilizing 0.1 M EDTA, the Pb(II) ions were subsequently released.

The adsorption process of Pb(II) by TFPOTDB-SO3H and its probable mechanism.

3.10 Assessments of performance

The maximum adsorption capacity of Pb(II) by the TFPOTDB-SO3H was compared to other adsorbents mentioned in Table 2. The TFPOTDB-SO3H's high porosity, which results in a large surface area for Pb(II) adsorption, indicates its significant advantages. This is attributed to its high adsorption capacity of 500 mg/g and rapid removal within 10 min. Consequently, the TFPOTDB-SO3H nano adsorbent shows promise as an effective and selective solution for removing Pb(II).

Adsorbent

Langmuir adsorption capacity qm (mg/g)

References

Ni0.6Fe2.4O4-HT-COF

411.8

(Wang et al., 2023)

Fe3O4@SiO2-NH2

243.9

(Zhang et al., 2013)

MOFs-DHAQ

232.5

(Zhao et al., 2020)

UiO-66-EDTA

357.9

(Wu et al., 2019)

COF-SH

239.0

(Cao et al., 2020)

Amide-COF

185.7

(Li et al., 2019)

SBFB a

57.471

(Praipipat et al., 2023)

Pea peel (biochar)

152.50

(Novoseltseva et al., 2021)

TFPOTDB-SO3H

500.0

This study

4 Conclusion

In summary, COFs have demonstrated an excellent ability in removing heavy metals due to the unique features such as high porosity, stability, large surface area, as well as more accessible active sites. This study presents a simple approach for creating sulfonated covalent organic framework (TFPOTDB-SO3H) as an effective adsorbent to eliminate Pb(II) ions from water samples. The XRD pattern showed a sharp peak at 4.4° which confirm the highly ordered and hexagonal structure in the synthesized COF. In addition, BET results display a high surface area of 190.73 m2/g with a pore size of 2.5 nm. Experimental tests revealed that the optimal adsorption occurred at pH 6.0 for Pb(II) ions. The adsorption behavior of Pb(II) ions onto TFPOTDB-SO3H followed the Langmuir isotherm model and the pseudo-second order model, describing monolayer adsorption on the sorbent surface with a maximum adsorption capacity of 500.0 mg/g at 298 K. Thermodynamic analysis indicated that the adsorption process was spontaneous and exothermic. Complete desorption of adsorbed Pb(II) ions was achieved using 0.1 M EDTA. Reusability investigations demonstrated that TFPOTDB-SO3H maintained over 89 % of its initial efficiency after 4 cycles. The TFPOTDB-SO3H COF has demonstrated its potential as an effective, economical, and eco-friendly adsorbent, with additional benefits such as ease of production and no by-product generation. Therefore, it holds promise as a valuable tool in environmental pollution remediation efforts.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mohammad Khosravani: Data curation, Visualization, Investigation, Software. Mohsen Dehghani Ghanatghestani: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Farid Moeinpour: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Hossein Parvaresh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks are extended to the Islamic Azad University Bandar Abbas Branch for its partial financial support.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Treatment of heavy metals containing wastewater using biodegradable adsorbents: A review of mechanism and future trends. Chemosphere. 2022;295:133724

- [Google Scholar]

- Equilibrium and thermodynamic studies on the removal of basic black dye using calcium alginate beads. Colloids Surf. a: Physicochem. Eng.. 2007;299:232-238.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic MCM-41 silica particles grafted with poly (glycidylmethacrylate) brush: modification and application for removal of direct dyes. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater.. 2017;243:164-175.

- [Google Scholar]

- New trends in removing heavy metals from industrial wastewater. Arab. J. Chem.. 2011;4:361-377.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fast and efficient removal of silver (I) from aqueous solutions using aloe vera shell ash supported Ni0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc.. 2016;26:2238-2246.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sulfhydryl functionalized covalent organic framework as an efficient adsorbent for selective Pb (II) removal. Colloids Surf. a: Physicochem. Eng.. 2020;600:125004

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of heavy metal ions by various low-cost adsorbents: a review. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem.. 2022;102:342-379.

- [Google Scholar]

- Micro–nanocomposites in environmental management. Adv. Mater.. 2016;28:10443-10458.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficient removal of Cr (VI) from aqueous solutions by a dual-pore covalent organic framework. Adv. Sustain. Syst.. 2019;3:1800150.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decontamination of lead and tetracycline from aqueous solution by a promising carbonaceous nanocomposite: Interaction and mechanisms insight. Bioresour. Technol.. 2019;283:277-285.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of heavy metals in water using nano zero-valent iron composites: A review. J. Water Process Eng.. 2023;53:103913

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel N-riched crystalline covalent organic framework as a highly porous adsorbent for effective cadmium removal. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2019;7:102907

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of Cd2+ from contaminated water by nano-sized aragonite mollusk shell and the competition of coexisting metal ions. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2012;367:378-382.

- [Google Scholar]

- Post-synthetic Modification of Covalent Organic Frameworks through in situ Polymerization of Aniline for Enhanced Capacitive Energy Storage. Chem. Asian J.. 2021;16:158-164.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of cadmium and lead ions from aqueous solutions by novel dolomite-quartz@ Fe3O4 nanocomposite fabricated as nanoadsorbent. Environ. Res.. 2023;225:115606

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of lead ions by acid activated and manganese oxide-coated bentonite. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2009;161:677-685.

- [Google Scholar]

- Covalent organic frameworks-based smart materials for mitigation of pharmaceutical pollutants from aqueous solution. Chemosphere. 2022;286:131710

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of heavy metals by covalent organic frameworks (COFs): A review on its mechanism and adsorption properties. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2021;9:105687

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption performance of amino functionalized magnetic molecular sieve adsorbent for effective removal of lead ion from aqueous solution. Nanomaterials. 2021;11:2353.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of Hg (II) from aqueous solution of activated carbon impregnated in copper chloride solution. Asian J. Chem.. 2013;25:10251-10254.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinoptilolite nano-particles modified with aspartic acid for removal of Cu (II) from aqueous solutions: isotherms and kinetic aspects. New J. Chem.. 2015;39:9396-9406.

- [Google Scholar]

- Emerging investigator series: design of hydrogel nanocomposites for the detection and removal of pollutants: from nanosheets, network structures, and biocompatibility to machine-learning-assisted design. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2018;5:2216-2240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thiol-functionalized magnetic covalent organic frameworks by a cutting strategy for efficient removal of Hg2+ from water. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2020;392:122320

- [Google Scholar]

- Stable covalent organic frameworks for exceptional mercury removal from aqueous solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2017;139:2428-2434.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solvent-free, single lithium-ion conducting covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2019;141:5880-5885.

- [Google Scholar]

- Construction of crystalline 2D covalent organic frameworks with remarkable chemical (acid/base) stability via a combined reversible and irreversible route. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2012;134:19524-19527.

- [Google Scholar]

- Postsynthetic Modification of Core-Shell Magnetic Covalent Organic Frameworks for the Selective Removal of Mercury. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2023;15:28476-28490.

- [Google Scholar]

- Carbon nanotubes and graphene-based materials for adsorptive removal of metal ions–A review on surface functionalization and related adsorption mechanism. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv.. 2023;16:100431

- [Google Scholar]

- Palladium-nanoparticle-decorated covalent organic framework nanosheets for effective hydrogen gas sensors. Nano Mater. ACS Appl. 2023

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Indonesian Kaolin supported nZVI (IK-nZVI) used for the an efficient removal of Pb (II) from aqueous solutions: Kinetics, thermodynamics and mechanism. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2021;9:106483

- [Google Scholar]

- Low-level environmental lead exposure and children’s intellectual function: an international pooled analysis. Environ. Health Perspect.. 2005;113:894-899.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of metal interference, pH and temperature on Cu and Ni biosorption by Chlorella vulgaris and Chlorella miniata. Environ. Technol.. 1999;20:953-961.

- [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic effect of functionalization and crystallinity in nanoporous organic frameworks for effective removal of metal ions from aqueous solution. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.. 2022;5:15228-15236.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fabrication of hydrazone-linked covalent organic frameworks using alkyl amine as building block for high adsorption capacity of metal ions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2019;11:11706-11714.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recent advances in the application of water-stable metal-organic frameworks: Adsorption and photocatalytic reduction of heavy metal in water. Chemosphere. 2021;285:131432

- [Google Scholar]

- Amide-based covalent organic frameworks materials for efficient and recyclable removal of heavy metal lead (II) Chem. Eng. J.. 2019;370:822-830.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biogenic reductive preparation of magnetic inverse spinel iron oxide nanoparticles for the adsorption removal of heavy metals. Chem. Eng. J.. 2017;307:74-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- Microenvironment engineering of covalent organic frameworks for the efficient removal of sulfamerazine from aqueous solution. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.. 2022;10:107300

- [Google Scholar]

- A Hydrazone-Based Covalent Organic Framework as an Efficient and Reusable Photocatalyst for the Cross-Dehydrogenative Coupling Reaction of N-Aryltetrahydroisoquinolines. ChemSusChem. 2017;10:664-669.

- [Google Scholar]

- Sorption of copper and lead by citric acid modified wood. Wood Sci. Technol.. 2004;38:629-640.

- [Google Scholar]

- Thermodynamics of solvation of ions. Part 5. —Gibbs free energy of hydration at 298.15 K. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans.. 1991;87:2995-2999.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ultra-high capacity of lanthanum-doped UiO-66 for phosphate capture: Unusual doping of lanthanum by the reduction of coordination number. Chem. Eng. J.. 2019;358:321-330.

- [Google Scholar]

- The studies on the hydration energy and water structures in dilute aqueous solution. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn.. 1986;59:1215-1222.

- [Google Scholar]

- Chemically activated carbon from lignocellulosic wastes for heavy metal wastewater remediation: Effect of activation conditions. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2017;493:228-240.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effective removal of Ni (II) from aqueous solutions by modification of nano particles of clinoptilolite with dimethylglyoxime. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2013;260:339-349.

- [Google Scholar]

- Production of high-performance lead (II) ions adsorbents from pea peels waste as a sustainable resource. Waste Manag. Res.. 2021;39:584-593.

- [Google Scholar]

- Aqueous scavenging of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons using epichlorohydrin, 1, 6-hexamethylene diisocyanate and 4, 4-methylene diphenyl diisocyanate modified starch: Pollution remediation approach. Arab. J. Chem.. 2019;12:2760-12277.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of Pb (II) from aqueous solutions using Acacia Nilotica seed shell ash supported Ni0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles. J. Water Reuse Desalin.. 2016;6:562-573.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diacetylene functionalized covalent organic framework (COF) for photocatalytic hydrogen generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2018;140:1423-1427.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metal-doped graphitic carbon nitride nanomaterials for photocatalytic environmental applications—a review. Nanomaterials. 2022;12:1754.

- [Google Scholar]

- Unique lead adsorption behavior of activated hydroxyl group in two-dimensional titanium carbide. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2014;136:4113-4116.

- [Google Scholar]

- Modification of sugarcane bagasse with iron (III) oxide-hydroxide to improve its adsorption property for removing lead (II) ions. Sci. Rep.. 2023;13:1467.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater: A comprehensive and critical review. npj Clean Water. 2021;4:36.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing a 3D-MoS2 nanocomposite based on the Donnan membrane effect for superselective Pb (II) removal from water. Chem. Eng. J.. 2023;452:139101

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental and modeling process optimization of lead adsorption on magnetite nanoparticles via isothermal, kinetics, and thermodynamic studies. ACS Omega. 2020;5:10826-10837.

- [Google Scholar]

- Mechanistic studies of two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks rapidly polymerized from initially homogenous conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2014;136:8783-8789.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile fabrication of ZIF-8/calcium alginate microparticles for highly efficient adsorption of Pb (II) from aqueous solutions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res.. 2019;58:6394-6401.

- [Google Scholar]

- Solid–liquid–solid extraction of heavy metals (Cr, Cu, Cd, Ni and Pb) in aqueous systems of zeolite–sewage sludge. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2009;161:1377-1383.

- [Google Scholar]

- Phenylthiosemicarbazide-functionalized UiO-66-NH2 as highly efficient adsorbent for the selective removal of lead from aqueous solutions. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2021;413:125278

- [Google Scholar]

- Detection and removal of mercury ions in water by a covalent organic framework rich in sulfur and nitrogen. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater.. 2022;4:849-858.

- [Google Scholar]

- A review on the adsorption of heavy metals by clay minerals, with special focus on the past decade. Chem. Eng. J.. 2017;308:438-462.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fabrication of eco-friendly polyelectrolyte membranes based on sulfonate grafted sodium alginate for drug delivery, toxic metal ion removal and fuel cell applications. Polymers. 2021;13:3293.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fabrication of polyelectrolyte membranes of pectin graft-copolymers with PVA and their composites with phosphomolybdic acid for drug delivery, toxic metal ion removal, and fuel cell applications. Membranes. 2021;11:792.

- [Google Scholar]

- The removal of lead ions from aqueous solution by using magnetic hydroxypropyl chitosan/oxidized multiwalled carbon nanotubes composites. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2015;451:7-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Removal of Pb(II) and methylene blue from aqueous solution by magnetic hydroxyapatite-immobilized oxidized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2017;494:380-388.

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel magnetic covalent organic framework for the selective and effective removal of hazardous metal Pb (II) from solution: Synthesis and adsorption characteristics. Sep. Purif. Technol.. 2023;307:122783

- [Google Scholar]

- An electrochemical aptasensor based on gold-modified MoS2/rGO nanocomposite and gold-palladium-modified Fe-MOFs for sensitive detection of lead ions. Sens. Actuators B Chem.. 2020;319:128313

- [Google Scholar]

- Electrochemical aptasensor based on gold modified thiol graphene as sensing platform and gold-palladium modified zirconium metal-organic frameworks nanozyme as signal enhancer for ultrasensitive detection of mercury ions. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2022;606:510-517.

- [Google Scholar]

- Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) for environmental applications. Coord. Chem. Rev.. 2019;400:213046

- [Google Scholar]

- Sulphonate functionalized covalent organic framework-based magnetic sorbent for effective solid phase extraction and determination of fluoroquinolones. J. Chromatogr. A. 2020;1612:460651

- [Google Scholar]

- Novel magnetic polysaccharide/graphene oxide@ Fe3O4 gel beads for adsorbing heavy metal ions. Carbohyd. Polym.. 2019;216:119-128.

- [Google Scholar]

- Efficient removal of metal contaminants by EDTA modified MOF from aqueous solutions. J. Colloid Interface Sci.. 2019;555:403-412.

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile synthesis of guanidyl-based magnetic ionic covalent organic framework composites for selective enrichment of phosphopeptides. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2020;1099:103-110.

- [Google Scholar]

- Highly crystalline covalent organic frameworks from flexible building blocks. Chem. Commun.. 2016;52:4706-4709.

- [Google Scholar]

- Magnetic covalent organic framework composites for wastewater remediation. Small. 2023;2301044

- [Google Scholar]

- Surface functional groups of carbon-based adsorbents and their roles in the removal of heavy metals from aqueous solutions: a critical review. Chem. Eng. J.. 2019;366:608-621.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enhanced removal of U (VI) from aqueous solution by chitosan-modified zeolite. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem.. 2020;323:1003-1012.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adsorption of heavy metal ions from aqueous solution by carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals. J. Environ. Sci.. 2013;25:933-943.

- [Google Scholar]

- Designing of hydroxyl terminated triazine-based dendritic polymer/halloysite nanotube as an efficient nano-adsorbent for the rapid removal of Pb (II) from aqueous media. J. Mol. Liq.. 2022;360:119407

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of mineral reaction between calcium and aluminosilicate on heavy metal behavior during sludge incineration. Fuel. 2018;229:241-247.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pb (II) removal of Fe3O4@ SiO2–NH2 core–shell nanomaterials prepared via a controllable sol–gel process. Chem. Eng. J.. 2013;215:461-471.

- [Google Scholar]

- Polymer-based nanocomposites for heavy metal ions removal from aqueous solution: a review. Polym. Chem.. 2018;9:3562-3582.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experimental and DFT study of selective adsorption mechanisms of Pb (II) by UiO-66-NH2 modified with 1, 8-dihydroxyanthraquinone. J. Indust. Eng. Chem.. 2020;83:111-122.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of sulfonic acid functionalized covalent triazine framework as a hydrophilic-lipophilic balance/cation-exchange mixed-mode sorbent for extraction of benzimidazole fungicides in vegetables, fruits and juices. J. Chromatogr. A. 2020;1618:460847

- [Google Scholar]

- Facile grafting of imidazolium salt in covalent organic frameworks with enhanced catalytic activity for CO2 fixation and the Knoevenagel reaction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.. 2020;8:18413-18419.

- [Google Scholar]

- Fabrication of synergistic sites on an oxygen-rich covalent organic framework for efficient removal of Cd(II) and Pb(II) from water. J. Hazard. Mater.. 2022;424:127301

- [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.105429.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary data 1

Supplementary data 1