Translate this page into:

Remarkable CO2 photocatalytic reduction enabled by UiO-66-NH2 anchored on flower-like ZnIn2S4

⁎Corresponding author.

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The utilization of renewable solar energy for the photocatalytic transformation of carbon dioxide (CO2) into valuable chemical substances is considered an optimal strategy to simultaneously address climate challenges and tackle energy scarcity. Herein, we prepared heterojunction photocatalysts UiO-66-NH2/ZnIn2S4, which were successfully applied in the photocatalytic reduction of CO2. The yield of the main product CO, for the optimal UiO-66-NH2/ZnIn2S4-2 sample could reach up to 57 μmol g−1h−1 when converting CO2 under the visible light irradiation, which was approximately 3.35 and 2.71 times higher than that achieved by the individual UiO-66-NH2 and ZnIn2S4 samples, respectively. The better photocatalytic performance of the UiO-66-NH2/ZnIn2S4-2 composites can be attributed to its synergistic effect resulting from tight interfacial contacts, special charge transfer pathways and excellent CO2 adsorption capacity. Furthermore, the intimate contact between UiO-66-NH2 and flower-like ZnIn2S4 accelerates electron transmission while effectively suppressing the quenching of photogenerated carriers. This research provides vital knowledge for the rational design of heterostructures aimed at enhancing the efficiency of CO2 photocatalysis for solar fuel production.

1 Introduction

The pressing global energy crisis and escalating environmental concerns caused by climate change, which are attributed to the overconsumption of energy, have brought forth a multitude of puzzles that necessitate attention. To effectively tackle these issues, it is imperative to focus on developing efficient technologies for carbon utilization and recycling (Stolarczyk et al., 2018; Cai et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022). Photocatalysts, which employ solar simulators to reduce CO2 into organic matters or valuable fuels like carbon monoxide, and formic acid, have brought to the forefront from researchers. Until now, a mass of photocatalysts, have been documented for the purpose of CO2 photoreduction, consisting metal oxides, semiconductor materials, metal organic frameworks (MOFs), and quantum dots among others (Wang et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2023a; Wu et al., 2023b; Yu et al., 2023a). However, photocatalysts still have some drawbacks and challenges, caused by the limited light absorption range, poor stability, low catalytic activity and high compounding rate of photoelectrons and holes so on (Gong et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2023). Under these circumstances, improving and enhancing photocatalytic performance remains a major challenge, for which approaches such as the design of materials, interface engineering, and loading materials might be effective strategies.

In various domains of photocatalysis, the exceptional performance exhibited by transition metal sulfide photocatalysts can be attributed to their distinctive optical and electrical properties. Among them, ZnIn2S4 (ZIS) has a prominent layered structure, a tunable forbidden band width, environmental friendliness and simplicity in synthesis (Wu et al., 2023c). Furthermore, the two dimensional nanosheet structure of ZIS also shortens the diffusion distance of charge carriers (Dang et al., 2021). However, limited CO2 adsorption, the fast recombination of photogenerated electron-hole pairs, and restricted migration capability prevent the utilization of ZIS in photocatalysis, which seriously constrains its photocatalytic activity (Xu et al., 2014; Yi et al., 2023). Thus, it is crucial for remarkable CO2 photocatalysis to find a material that exhibits excellent CO2 adsorption, tunable active sites to effectively enhance electron transfer, as well as inhibits electron-hole pair complexation by forming a tight interfacial interaction strategy by complexing with ZIS.

Fortunately, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are a type of porous substance characterized by a crystal structure in three dimensions (3D), comprising clusters of metal–oxygen and ligands derived from organic compounds. Highly stable UiO-66-NH2, characterizes by large surface areas, adjustable porous dimensions, designable porous structures and outstanding gas adsorption performance, which exhibits potential as a candidate for CO2 photoreduction. Nevertheless, the narrow range of light absorption, wide bandgap, and high recombination of electron-hole pairs generated by light hinder the efficiency of photocatalysis when using MOFs as catalysts (Chen et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). Several tactics can be employed to enhance the photocatalytic efficiency of MOFs, such as metal doping (Dai et al., 2022) addition of co-catalysts (Mahmoud et al., 2019). Moreover, One possible method to improve the photocatalytic activity is by combining light-trapping semiconductor materials with MOFs to form heterostructures, which can effectively separate photogenerated carriers, including UiO-66-NH2@TpPa-COF (Yu et al., 2023b), CuO/Ag/UiO-66 (Zhang et al., 2022), UiO-66-NH2/CuZnS (Sun et al., 2023).

Since the physicochemical properties of MOFs and metal sulfide can complement each other in CO2 photocatalytic reduction, the photocatalytic performance could be improved at a large extent. During my research, the heterojunction of UiO-66-NH2/ZnIn2S4 was constructed in-situ using the low-temperature hydrothermal method and utilized for CO2 photoreduction. The optimized sample UiO-66-NH2/ZnIn2S4-2 achieved a CO evolution rate of 57 μmol g−1h−1, surpassing the pure UiO-66-NH2 and ZnIn2S4 samples by approximately 3.35 and 2.71 times, respectively. The improved catalytic property is affiliated to 1) the intimate interaction between UiO-66-NH2 and flower-like ZnIn2S4, which accelerates the transmission of electrons and significantly promotes the separation of photogenerated carriers, 2) the large specific surface area and high CO2 adsorption, which lay the foundation for the next catalysis. Importantly, the randomly stacked UiO-66-NH2 on ZnIn2S4 can avoid particle aggregation. In addition, photoluminescence decay tests and transient photocurrent densities demonstrate that the composites have a strong ability to accept photogenerated electrons and maximize the reactive sites, which facilitates the directed movement of photogenerated excitons towards CO2 reduction, thereby providing persistent electrons.

2 Results and discussion

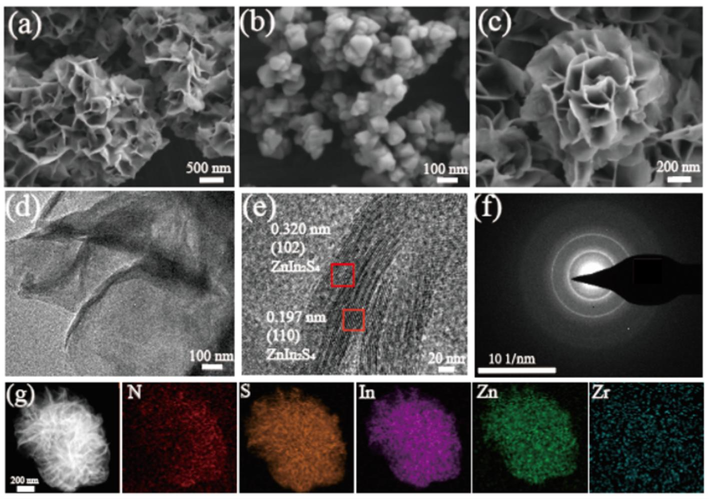

The UiO-66-NH2/ZIS heterojunction materials are obtained through the in-situ assembly of the pre-composited UiO-66-NH2 octahedron onto the three-dimensional flower-like ZIS (refer to the experimental details in the Supporting Information). Fig. 1 demonstrates the morphologies obtained by the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) reflections of UiO-66-NH2, ZIS and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2. A pure ZIS sample is observed to be assembled from many nanosheets into flower-like spheres in Fig. 1a, which exhibit similar morphologies were also reported in other articles (Sun et al., 2021; Raja et al., 2023). In Fig. 1b, it can be observed that the approximate dimensions of the UiO-66-NH2 sample is around 70 nm, and the sample possesses a consistent and symmetrical octahedral structure with uniform shape. In Fig. 1c, for the UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 composite, a flowery spherical shape was primarily investigated, and the nanoparticles allocated to UiO-66-NH2 could be discovered in the sandwich-like structure of the flower-like spherical ZIS. Fig. S1 further demonstrates the morphologies of UiO-66-NH2, ZIS, and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 from different angles.

SEM results of ZIS (a), UiO-66-NH2 (b), UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 (c). TEM results of (d), HR-TEM images of (e), SAED images of (f) and EDX elemental mapping of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 (g).

Fig. 1d and e show the specific marginal morphologies of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 at the nanoscale, as observed through transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-resolution TEM (HR-TEM). The heterojunction UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 exhibited a villiform margin consisting of flower-like spherical ZIS, whereas UiO-66-NH2 nanoparticles were found on the villiform margins (Fig. 1d). In Fig. 1e, the images of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 mainly exhibit the crystal planes (1 0 2) and (1 1 0), corresponding to ZIS lattice spacings of approximately 0.320 nm and 0.197 nm, respectively. Combined with the HR-TEM image, Fig. 1f demonstrates that the UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 possesses a polycrystalline structure, as evidenced by the corresponding selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern.

To determine the chemical composition and distribution of elements in the UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 material synthesized, we conducted the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) measurement. The EDX spectrum confirms the presence of N, S, In, Zn and Zr in the material (Fig. 1g). Furthermore, the images obtained from mapping the corresponding elements indicate a homogeneous distribution of these aforementioned elements on the heterojunction UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 nanoparticles.

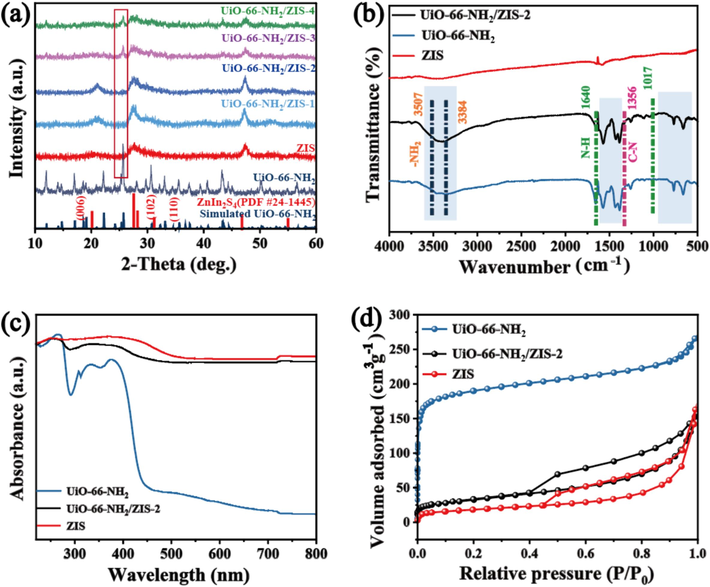

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were performed to obtain the crystal structures of UiO-66-NH2, ZIS and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS (Fig. 2a). The XRD pattern of UiO-66-NH2 is consistent with the simulated diffraction peaks (Wang et al., 2020). For pure ZIS, the three peaks centered at 22.7, 27.6 and 47.20° are indexed to the (0 0 6), (1 0 2) and (1 1 0) planes according to the standard hexagonal phase (PDF#24-1445). No other peaks are detected in the pure samples, indicating successfully prepared of UiO-66-NH2 and ZIS. For the heterojunction UiO-66-NH2/ZIS composite, both UiO-66-NH2 and ZIS peaks are found, with a slight increase in diffraction peak intensity as the proportion of UiO-66-NH2 increases.

(a) XRD patterns of the as-prepared UiO-66-NH2, ZIS and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-y (y = 1, 2, 3, 4) samples. (b) FT-IR spectra patterns, (c) UV–Vis–NIR absorption spectra, (d) Nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms of UiO-66-NH2, ZIS, and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2.

The fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra was employed to evaluate alterations in the surface’s functional groups of the UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 heterostructure. Fig. 2b demonstrates two distinct peaks around 3507 and 3384 cm−1 in UiO-66-NH2, which correspond to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the —NH2 functional groups, respectively (Kandiah et al., 2010). In addition, two distinct peaks are observed at around 1640 and 1356 cm−1, which correspond to the bending vibration of N—H bonds and the characteristic stretching vibration of C—N bonds in aromatic amines. However, in the FT-IR spectrum of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2, the peaks at 3507, 3384 and 1640 cm−1 become obviously weaker compared with UiO-66-NH2, which might be due to the interaction between —NH2 and ZIS. A string of characteristic bands around 1600–1450 and 900–650 cm−1 can be imputed to benzene skeleton stretching and in-plane bending vibrations of the benzene ring respectively, demonstrating that complete MOFs structures are maintained for UiO-66-NH2 within heterojunctions.

The optical properties of ZIS, UiO-66-NH2, and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 were analyzed using UV–Vis–NIR diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) (Fig. 2c). Other UV diagrams of the prepared catalysts are placed in the Supporting Information (Fig. S7). The UiO-66-NH2 exhibited the visible absorption with a slight peak at 395 nm that disappeared around 430 nm. Interestingly, ZIS and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 showed comparable consequences, which was a maximum absorption located at 445 nm with an extended tail reaching to 800 nm, suggesting that the heterojunction UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 provides a solid foundation for light capture in subsequent photocatalytic reduction.

The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) specific surface area and pore size distribution of UiO-66-NH2, ZIS and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 were analyzed using the nitrogen adsorption–desorption method (Fig. 2d). We observe ZIS presents a typical IV-type isotherm with the existence of an H3-type hysteresis loop (Wang et al., 2022). The curve of UiO-66-NH2 shows a typical of a type I isotherm (Fu et al., 2019). The curve of the composites UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 manifests itself as mixture of type I and type IV isotherms. The BET specific surface area of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 (144 m2 g−1) on Table S1 exceeded that of ZIS (63 m2 g−1), yet fell short of UiO-66-NH2 (739 m2 g−1), thereby potentially offering more CO2 reaction sites compared to ZIS. In this study, the BJH (Fig. S2) pore size distribution further confirms the microporous structure of UiO-66-NH2 (Fu et al., 2019), mesoporous structure of ZIS (Peng et al., 2020), and mesoporous structure of the composite UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2.

It is very significant for the CO2 capture capability of a photocatalyst. Thus, CO2 adsorption isotherms were characterized at 298 K (Fig. S9). The isotherm measurement of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 (15 cm3 g−1) exhibits a moderate adsorption amount, which is lower than that of UiO-66-NH2 (33 cm3 g−1) but much higher than that of ZIS (3 cm3 g−1). The results illustrate that the introduction of UiO-66-NH2 was responsible for the enhanced CO2 adsorption of the composite.

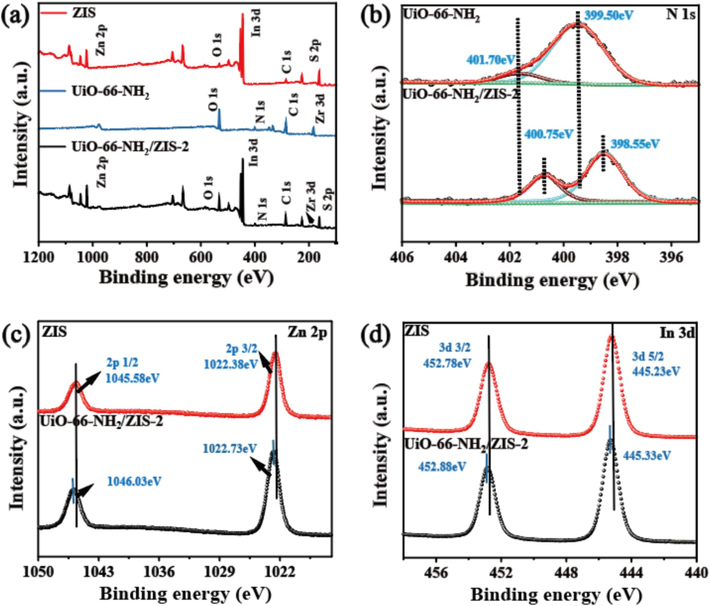

The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to analyze the surface element composition and coordination states of UiO-66-NH2, ZIS and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2. XPS survey spectra indicate that Zr, N, Zn, S, and In elements can be detected in the heterojunction UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2, which are in according with the EDX results (Fig. 3a). The peaks of N 1s in UiO-66-NH2 can be fitted to two peaks at 399.50 eV and 401.70 eV, which are involved in the formation of amino groups and N—C bonds, respectively (Fig. 3b) (Fang et al., 2024). However, N 1s spectra of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 shift to 398.55 and 400.75 eV, respectively, which reveal that the coordination state of N changes obviously, possibly due to the interaction between UiO-66-NH2 and ZIS. While for Zn, the peaks at 1022.73 and 1046.03 eV are corresponding to 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 orbitals, respectively (Fig. 3c), demonstrating the presence of the Zn2+ state (Liu et al., 2018). Fig. 3d depicts the In 3d spectra in UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2, where In 3d5/2 and In 3d3/2 correlate with 445.33 and 452.88 eV, respectively, thus suggesting that its valence state is +3 (Wang et al., 2018). Besides, Fig. S3a and b present the XPS results for Zr and S, respectively (Wang et al., 2023a; Nie et al., 2023). Changes in electron density can be analyzed by the elemental binding energies (Wang et al., 2019). As the above mentioned results, the binding energy of N 1s in UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 shifts to the lower binding energy compared to that of UiO-66-NH2, which implies that UiO-66-NH2 gains electrons. Similarly, the binding energies of S 2p, In 3d and Zn 2p in UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 shift towards the higher binding energies compared to ZIS, indicating a decrease in the electron cloud density of ZIS. The binding energy deviation shows that the electrons in ZIS move toward UiO-66-NH2 until the Fermi energy level reaches equilibrium.

XPS spectra of (a) Survey; (b) N 1s; (c) Zn 2p (d) In 3d of pure UiO-66-NH2, pure ZIS, and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2.

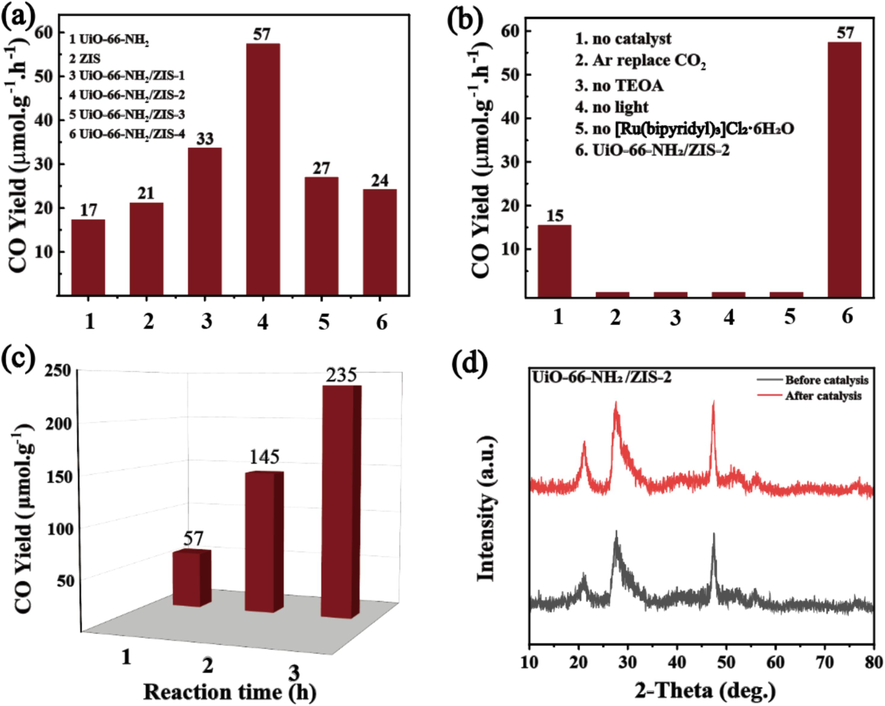

The photocatalytic CO2 reduction reactions are detected using triethanolamine (TEOA) as a hole scavenger and [Ru(bipyridyl)3]Cl2·6H2O as a photosensitizer under visible light irradiation. In Fig. 4a, the UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 photocatalyst achieved the optimum CO yield of 57 μmol g−1h−1, which is approximately 3.35 and 2.71 times higher than those of the pure UiO-66-NH2 (17 μmol g−1h−1) and ZIS (21 μmol g−1h−1), respectively. The CO evolution activity of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 is equivalent or higher than that of the latest findings (Table S2). Such findings highlight that anchoring UiO-66-NH2 on flower-like ZnIn2S4 forming heterostructures greatly improves the CO production efficiency. The excellent performance of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 can be ascribed to the heterojunction between ZIS and UiO-66-NH2, which accelerated the transfer and separation of charge carriers and thus improved the photocatalytic CO2 performance. However, the CO2 reduction activity decreases with the continued increase in the amount of UiO-66-NH2, which could be attributed to the excess UiO-66-NH2 covering part of ZIS and break down the balance of their synergistic effect. The CO2 reduction of the composite catalysts was further investigated through several control experiments to provide a more detailed analysis. In Fig. 4b, blanking experiments were conducted under five conditions: (1) absence of photocatalyst; (2) light and Ar atmosphere; (3) none of sacrificial agent; (4) darkness; and (5) none of photosensitizer. In all blank experiments, no CO products were diagnosed except for condition (1), confirming that reactant of CO2, sacrificial agent of TEOA, light irradiation, photosensitizer of [Ru(bipyridyl)3]Cl2·6H2O and catalyst are crucial in photocatalytic CO2 experiments. In Fig. 4c, the time-dependent experiments demonstrated that UiO-66-NH2(Zr)/ZIS-2 exhibited a significant CO release activity for 3 h, achieving a gross yield of 235 μmol g−1. Besides, to further investigate the stability of catalyst, we performed a round robin test on the best samples and found that the catalytic activity remained high after 3 consecutive reactions (Fig. S5). XRD of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 is the same as the as-synthesized sample (Fig. 4d), which verifies the high structural durability of the photocatalyst.

(a) Photocatalytic CO2 evolution performance of different samples. (b) The CO2 reduction performance under various conditions. (c) CO production as a function of irradiation time. (d) X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) patterns of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 before and after CO2 photoreduction.

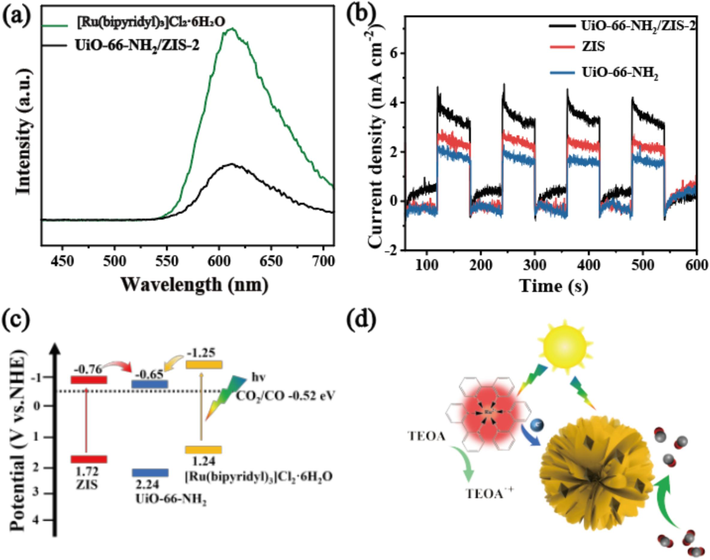

To reveal the enhancement of the photocatalytic activity over UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2, the energy level structure is studied by results of DRS, VB-XPS and Mott-Schottky plots. The bandgap energies (Eg) of UiO-66-NH2, UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2, and ZIS are calculated to be 2.89, 2.62, and 2.48, respectively (Fig. S6a). VB XPS measurements were employed to investigate the valence band edges (EVB). In Fig.S6b and S6c, the EVB values of UiO-66-NH2 and ZIS were observed at 2.75 and 1.78 eV, respectively. The flat-band potentials of ZIS and UiO-66-NH2 were investigated by the Mott-Schottky mapping characterization method and tested them at 1000, 2000, and 3000 Hz (Fig. S7). When the slope of the curve is positive, it indicates that the material belongs to the n-type semiconductor (Wang et al., 2023b). Flat-band potential values were obtained from the intersection of the tangents via the three frequency tests. The flat-band potentials of UiO-66-NH2 and ZIS were −0.75 V and −0.86 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). In other words, the flat-band potentials were −0.55 V and −0.66 V (vs. NHE) for normal hydrogen electrodes, respectively. Since the potential at the edge of the conduction band of the n-type semiconductor is about 0.1eV more negative than the flat band (Liu et al., 2023). Hence, the conduction band minimum (CBM) is −0.65 V vs. NHE for UiO-66-NH2 and −0.76 V vs. NHE for ZIS. Based on the values of ECBM and Eg, one can derive the valence band edges (EVBM) using the subsequent equation:

Accordingly, the EVBM values of UiO-66-NH2 and ZIS are about 2.24 and 1.72 eV, respectively. Significantly, the CB and VB edges of UiO-66-NH2 are found to be lower than those of ZIS, suggesting the possibility of electron transfer from ZIS to UiO-66-NH2 upon photoexcitation. More importantly, the CB values of UiO-66-NH2 and ZIS exhibit greater negativity in comparison to the potential of CO2/CO (−0.52 eV vs. NHE) (Wang et al., 2021). Consequently, it is thermodynamically viable to convert CO2 into CO on the CB of the UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 during the photocatalytic process. The band energy positions of UiO-66-NH2 and ZIS are illustrated in Fig. 5c. The positions of both the conduction and valence bands of UiO-66-NH2 are more positive than those of ZIS, leading to the formation of staggered type Z heterojunctions between them, which is in agreement with previous reports (Mei et al., 2022).

Steady-state PL spectra (a) and photocurrent profiles (b) of the different samples. (c) Energy band structures of ZIS and UiO-66-NH2. (d) Proposed mechanism of the photocatalytic CO2 reduction over UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2.

To understand the catalytic mechanism, the steady-state photoluminescence (PL) spectra display obvious PL quenching compared to photosensitizer of [Ru(bipyridyl)3]Cl2·6H2O (Fig. 5a), indicating the restrained recombination of photoinduced electron-hole pairs and the efficient charge movement from [Ru(bipyridyl)3]Cl2·6H2O to UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 (Wang et al., 2019). To further demonstrate the carrier dynamics, the time-resolved PL spectra were examined under the similar CO2 photocatalytic reduction system with and without catalyst of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 (Fig S10). When there is no UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 in the testing system, the average lifetime of [Ru(bipyridyl)3]Cl2·6H2O is 180.75 ns, which is much longer than that of system with UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 (144.92 ns). The results indicate that the excited [Ru(bipyridyl)3]2+ is quenched by the catalyst of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2, confirming the efficient electron-hole separation and transfer between [Ru(bipyridyl)3]Cl2·6H2O and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2. In order to investigate the efficiency of separating and transferring photogenerated carriers, the transient photocurrent analysis was performed. Fig. 5b illustrates the responses of ZIS, UiO-66-NH2, and UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 under simulated sunlight and several on/off irradiation cycles, and all samples produced stable photocurrent profiles. Among all samples, UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 exhibited the highest photocurrent density, which suggests that the electron-hole pairs are effectively separated and promoted charge transfer in the heterojunction UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2. The photoelectrochemical findings show that the suppressed recombination and enhanced transport efficiency of photoinduced electron-hole pairs in UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2, thus assuring the high CO-producing rate.

Based on the results of activity assessment and photoelectrochemical results, a possible mechanism for CO2 photocatalytic reduction is proposed (Fig. 5c and d). Under visible light irradiation, the photosensitizer of [Ru(bipyridyl)3]Cl2·6H2O is excited from its valence band to conduction band. The photoinduced electrons transfer from [Ru(bipyridyl)3]Cl2·6H2O to UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2 for CO2 photoreduction, while the holes are consumed by TEOA to complete the entire cycle. In addition, due to the excellent visible-light absorption of UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2, it might produce photogenerated carriers that can be directly utilized for CO2 photocatalytic reduction.

3 Conclusion

In summary, ZnIn2S4/UiO-66-NH2 photocatalysts were efficiently synthesized by a facile hydrothermal method in different ratios, and it was found that the best performance of the composite photocatalyst was optimal when 10 mg of UiO-66-NH2 was coupled with ZIS. In my research, the best composite photocatalyst was UiO-66-NH2/ZIS-2, which demonstrated a significantly enhanced photocatalytic activity of 57 μmol g−1h−1, surpassing that of pure UiO-66-NH2 and ZIS samples by approximately 3.35 and 2.71 times respectively. The experimental results demonstrate that this rational design not only effectively accelerates the speed of electron transmission and effectively suppress the quenching of photogenerated carriers, but also provides the large specific surface area and high CO2 adsorption for catalytic reaction. This study provides vital knowledge for the rational design of composite structures for the highly efficient CO2 photocatalysis into solar fuels.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Huimin Yu: Writing – original draft, Data curation. Shaohong Guo: Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Meilin Jia: Supervision. Jingchun Jia: Formal analysis. Ying Chang: Validation. Jiang Wang: Validation.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Inner Mongolia of China (2021BS02019), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Inner Mongolia Normal University (2023JBQN045), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22262026).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Construction of CdLa2S4/MIL-88A(Fe) heterojunctions for enhanced photocatalytic H2-evolution activity via a direct Z-scheme electron transfer. Chem. Eng. J.. 2020;379:122389

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ultrasmall copper nanoclusters in zirconium metal-organic frameworks for the photoreduction of CO2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2022;61:e202211848.

- [Google Scholar]

- The in situ construction of ZnIn2S4/CdIn2S4 2D/3D nano hetero-structure for an enhanced visible-light-driven hydrogen production. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2021;9:14888-14896.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synergistic mediation of dual donor levels in CNS/BOCB-OV heterojunctions for enhanced photocatalytic CO2 reduction. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2024;12:3398-3410.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Temperature modulation of defects in NH2-UiO-66(Zr) for photocatalytic CO2 reduction. RSC Adv.. 2019;9:37733-37738.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Solar fuels: research and development strategies to accelerate photocatalytic CO2 conversion into hydrocarbon fuels. Energ. Environ. Sci.. 2022;15:880-937.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Synthesis and stability of tagged UiO-66 Zr-MOFs. Chem. Mater.. 2010;22:6632-6640.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Research progress on CO2 capture and utilization technology. J. CO2 Utiliz.. 2022;66:102260

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Construction of heterostructured ZnIn2S4@NH2-MIL-125(Ti) nanocomposites for visible-light-driven H2 production. Appl. Catal. B. 2018;221:433-442.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cu atoms on UiO-66-NH2/ZnIn2S4 nanosheets enhance photocatalytic performance for recovering hydrogen energy from organic wastewater treatment. Appl. Catal. B. 2023;330

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hydrothermal synthesis of MoS2/SnS2 photocatalysts with heterogeneous structures enhances photocatalytic activity. Materials. 2023;16(12):4436.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metal-organic framework photocatalyst incorporating bis(4′-(4-carboxyphenyl)-terpyridine)ruthenium(II) for visible-light-driven carbon dioxide reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2019;141:7115-7121.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Facilely fabrication of the direct Z-scheme heterojunction of NH2-UiO-66 and CeCO3OH for photocatalytic reduction of CO2 to CO and CH4. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2022;597

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the role of Zn vacancy induced by sulfhydryl coordination for photocatalytic CO2 reduction on ZnIn2S4. J. Mater. Chem. A. 2023;11:1793-1800.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanohybrid photocatalysts with ZnIn2S4 nanosheets encapsulated UiO-66 octahedral nanoparticles for visible-light-driven hydrogen generation. Appl. Catal. B. 2020;260:118152

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Direct Z-scheme ZnIn2S4 spheres and CeO2 nanorods decorated on reduced-graphene-oxide heterojunction photocatalysts for hydrogen evolution and photocatalytic degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci.. 2023;607:155087

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Challenges and prospects in solar water splitting and CO2 reduction with inorganic and hybrid nanostructures. ACS Catal.. 2018;8:3602-3635.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- O, S-dual-vacancy defects mediated efficient charge separation in ZnIn2S4/Black TiO2 heterojunction hollow spheres for boosting photocatalytic hydrogen production. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021;13:37545-37552.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- S-scheme photocatalyst NH2–UiO-66/CuZnS with enhanced photothermal-assisted CO2 reduction performances. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng.. 2023;11:14827-14840.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- In situ irradiated XPS investigation on S-scheme TiO2@ZnIn2S4 photocatalyst for efficient photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Small. 2021;17:2103447.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Construction of ZnIn2S4–In2O3 hierarchical tubular heterostructures for efficient CO2 photoreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc.. 2018;140:5037-5040.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hollow nanoboxes Cu2-xS@ZnIn2S4 core-shell S-scheme heterojunction with broad-spectrum response and enhanced photothermal-photocatalytic performance. Small. 2022;18:2400652.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chemical bonding of g-C3N4/UiO-66(Zr/Ce) from Zr and Ce single atoms for efficient photocatalytic reduction of CO2 under visible light. ACS Catal.. 2023;13:4597-4610.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Supporting ultrathin ZnIn2S4 nanosheets on Co/N-doped graphitic carbon nanocages for efficient photocatalytic H2 generation. Adv. Mater.. 2019;31:1970291.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cu2O@Cu@UiO-66-NH2 ternary nanocubes for photocatalytic CO2 reduction. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.. 2020;3(10):10437-10445.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spatial separation of redox centers for boosting cooperative photocatalytic hydrogen evolution with oxidation coupling of benzylamine over Pt@UiO-66-NH2@ZnIn2S4. Cat. Sci. Technol.. 2023;13:2517-2528.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Selective CO2-to-C2H4 photoconversion enabled by oxygen-mediated triatomic sites in partially oxidized bimetallic sulfide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2023;62:e202301075.

- [Google Scholar]

- ZnIn2S4-based S-scheme heterojunction photocatalyst. J. Mater. Sci. Technol.. 2023;167:184-204.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spin manipulation in a metal-organic layer through mechanical exfoliation for highly selective CO2 photoreduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2023;62:e202301925.

- [Google Scholar]

- A 1D/2D helical CdS/ZnIn2S4 nano-heterostructure. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.. 2014;53:2339-2343.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Atomic sulfur dissimilation remolding ZnIn2S4 nanosheets surface to enhance built-internal electric field for photocatalytic CO2 conversion to syngas. Appl. Catal. B. 2023;338:123003

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Adaptive lattice-matched MOF and COF core-shell heterostructure for carbon dioxide photoreduction. Cell Reports Phys. Sci.. 2023;4:101657

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Semiconducting quantum dots for energy conversion and storage. Adv. Funct. Mater.. 2023;33:2213770.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Ag cocatalyst on highly selective photocatalytic CO2 reduction to HCOOH over CuO/Ag/UiO-66 Z-scheme heterojunction. J. Catal.. 2022;413:31-47.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A

Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arabjc.2024.105975.

Appendix A

Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:Supplementary Data 1

Supplementary Data 1