Translate this page into:

A comprehensive strategy integrating metabolomics with DNA barcoding for discovery of combinatorial discriminatory quality markers: A case of Cimicifuga foetida and Cimicifuga dahurica

⁎Corresponding authors at: State Key Laboratory of Component-based Chinese Medicine, Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin 301617, China. dkztcm@tjutcm.edu.cn (Kunze Du), Tcmcyx@tjutcm.edu.cn (Yanxu Chang)

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

This article was originally published by Elsevier and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

The multiple species characteristics of traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) are crucial for expanding TCMs sources, meeting the needs of the pharmaceutical industry and ensuring clinical requirements. It’s also one of the significant factors affecting the quality control of TCMs. Systematic differential analysis of original species in TCMs is an important link in achieving comprehensive quality control, ensuring the effectiveness and safety of clinical medication. The study aims to establish a reliable and efficient approach to screen combinatorial discriminatory quality markers for rapid differentiation of original species by metabolomics coupled with DNA barcoding as a case of Cimicifugae Rhizoma. DNA barcoding is used to identify the origin of Cimicifugae Rhizoma. The data-dependent acquisition mode integrated with the computerized intelligent filtering system was established for in-depth characterization of metabolites from Cimicifugae Rhizoma using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography to quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS). The untargeted metabolomics combined with multivariate statistical analysis was performed to screen and identify the potential combinatorial discriminatory quality markers. Finally, quantitative analysis and predictive model of these markers were employed to validate the feasibility of this strategy to distinguish the original species. Based on the scores of variable importance in projection greater than 1.0 and t-test (p < 0.05) in chemometric analysis, caffeic acid, cimifugin, ferulic acid and isoferulic acid were authenticated as combinatorial discriminatory quality markers for the two original species of Cimicifugae Rhizoma. In addition, the Fisher discriminant model successfully classified 56 batches of Cimicifugae Rhizoma with an accuracy of 94.4 %, showcased the practicality and scientific validity of this method. This study has provided a comprehensive strategy for efficient discrimination of multiple species of medicinal materials.

Keywords

Cimicifuga foetida

Cimicifuga dahurica

Data-dependent acquisition

Metabolomics

DNA barcoding

- AdaBoost

-

Adaptive boosting algorithm

- C. dahurica, XSM

-

Cimicifuga dahurica

- C. foetida, SM

-

Cimicifuga foetida

- CIF

-

computerized intelligent filtering

- CR

-

Cimicifugae Rhizoma

- DDA

-

data-dependent acquisition

- DIA

-

data-independent acquisition

- FA

-

formic acid

- HPLC-DAD

-

High Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode-Array Detection

- KNN

-

K-Nearest Neighbor

- K2P

-

Kimura 2-parameter

- LC/MS

-

Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry

- NJ

-

Neighbor-Joining

- PCA

-

Principal Component Analysis

- PILs

-

precursor ion lists

- OPLS-DA

-

Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis

- RSDs

-

relative standard deviations

- TCMs

-

traditional Chinese medicines

- UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS

-

ultra-high performance liquid chromatography to quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry

Abbreviations

1 Introduction

The application of traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs) in clinical practice is gradually expanding due to its abundant species resources, high efficacy, low cost and low toxicity (Wang et al., 2021). However, the quality control standards of TCMs have not been fully unified because of the differences in national, ministerial and local drug inspection standards. The plant species is an important influential factor of TCMs quality. Accurate identification of plant species of TCMs is the primary link in TCMs quality control. The quality can be evaluated to further ensure the efficacy and safety of clinical medication by clearly differentiating the plant species of TCMs (Zhang et al., 2022). Therefore, it is required to establish an efficient and practical approach for investigating the chemical differences of the plant species used as the same TCM.

Cimicifugae Rhizoma (CR), belonging to the Ranunculaceae family, is one of the widely used TCMs for relieving oral ulcers, herpes zoster, chronic pulmonary heart disease and menopause symptoms (Zheng et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2014). Currently, the reported components of CR mainly include triterpenoid saponins (Pang et al., 2021), phenylpropanoids (Lu et al., 2019), chromones (Duan et al., 2021), alkaloids (Thao et al., 2017) and terpenoids (Ma et al., 2013). The CR cultivars are broadly distributed throughout China, encompassing Cimicifuga foetida L., Cimicifuga dahurica (Turcz.) Maxim. and Cimicifuga heracleifolia Kom. (Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission, 2020). The use of multiple species of herbal medicines is convenient for accessing materials from local sources and addressing resource scarcity. The CR species have high similarity in appearance. However, the current method had rarely been reported according to morphological evaluation without objectivity and reliable methods for differentiating the species. In addition, the chemical compositions of CR often vary from varieties and they serve as the basis for its therapeutic effects in clinic. Therefore, it is imperative to develop a new method to investigate the accurate chemical differences of CR species.

DNA barcoding is an effective and accurate technique that identifies the plant species using one or several short DNA gene fragments. Due to the stability of DNA sequence, this technique remains unaffected by variables such as plant growth years, growth environment or plant parts. Therefore, it is widely recognized and applied for identifying the origin (Wang et al., 2021), adulteration (Shi et al., 2017) and authenticity of medicinal herbs (Guo et al., 2017). ITS2, as a non-coding nuclear DNA, can effectively distinguish species in close phylogenetic relationships with the characteristics of easy sequence amplification, high success rate and strong universality. Therefore, the ITS2 was used as the most suitable region for discriminating species. Based on this, a system for TCMs identification was established to facilitate rapid differentiation between the plant species (Gao et al., 2019).

Plant metabolomics is the qualitative and quantitative research of small molecules of secondary metabolites in different species, genotypes or ecological environment at growth stages (Li et al., 2021, Meng et al., 2023). Due to its high applicability and specificity, metabolomics had been employed extensively to quest for the species authentication (Bielecka et al., 2021), the quality evaluation (Yue et al., 2019), the analytical origins (Cao et al., 2021), the bioactivity screening (Qu et al., 2021) and research on mechanism (Fu et al., 2022, Wurihan et al., 2022) in TCMs. A comprehensive insight into the secondary metabolites of various species in TCMs is vital for further differential components analysis. Ultra-high performance liquid chromatography to quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS) offers high sensitivity, high resolution and high accuracy, making it an increasingly important tool for characterizing complex components and uncovering unknown metabolites in TCMs (Li et al., 2020, Chen et al., 2022, Qu et al., 2023). Nowadays, the most commonly used method for untargeted metabolites characterization is Data Dependent Acquisition (DDA). The interference of unrelated ions is evidently reduced and high-quality fragments are obtained favoring the elucidation of structural information in DDA method (Rudt et al., 2023). Premised on this, a segmented collection mode with limited mass range was constructed and a computerized intelligent filtering (CIF) platform was established during the data processing stage to analyze and characterize the chemical components. Therefore, an in-depth metabolites characterization strategy was proposed based on DDA mode and CIF system in this study.

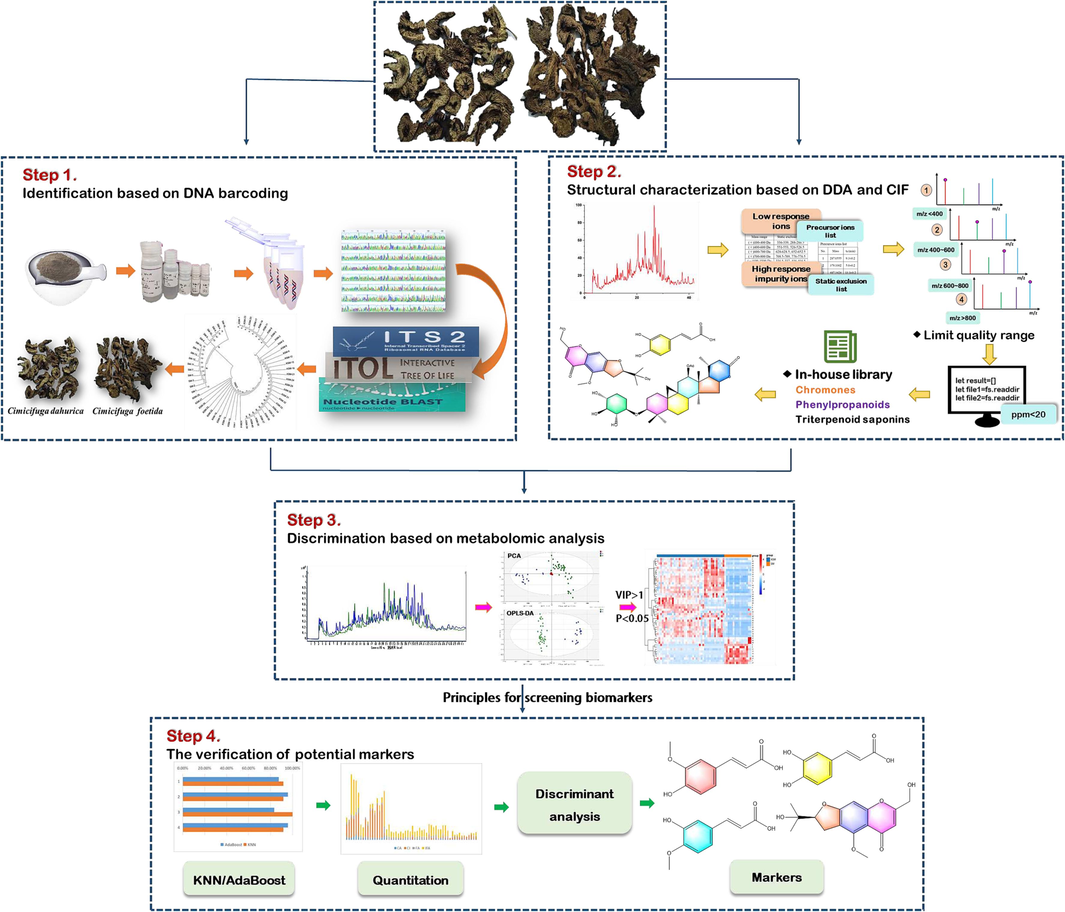

The strategy integrating metabolomics with DNA barcoding was applied to screen combinatorial discriminatory quality markers of Cimicifuga foetida (C. foetida) and Cimicifuga dahurica (C. dahurica) on the basis of the phylogenetic relationships and chemical constituents. Firstly, the ITS2 sequences were completely gained by DNA barcoding to distinguish the two species of CR. Secondly, the in-depth and global characterization of CR was conducted using a combination of DDA and CIF techniques by UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS. Thirdly, the combinatorial discriminatory quality markers were confirmed eventually using metabolomic combined with chemometric methods, including caffeic acid, cimifugin, ferulic acid and isoferulic acid. A comprehensive strategy combining metabolomics with DNA barcoding was applied for the first time in Cimicifugae Rhizoma to screen combinatorial discriminatory quality markers for rapid differentiation. The established strategy showed the ability to distinguish original plants and also provided significant guide for the quality control in TCMs. The schematic diagram illustrates the strategy of screening combinatorial discriminatory quality markers in CR (Fig. 1).

The schematic diagram of the strategy of discriminational investigation in CR.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Plant material and pretreatment

A total of 56 batches of CR (Table S1 in Supplementary materials) were from two species, of which 44 batches were purchased from the markets and 12 batches were collected from wild plants. The purchased batches were mainly from Sichuan, Inner Mongolia and the three northeast provinces of China while the collected batches were obtained from Heilongjiang. All samples were identified by Prof Yanxu Chang (Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine) using morphological authentication. The voucher specimens were deposited in State Key Laboratory of Component-based Chinese Medicine (Tianjin, China). The CR samples were powdered with a pulverizer and filtered through a 50-mesh sieve. Each sample powder (0.100 g) was weighed accurately and extracted by an ultrasonator with 4.0 mL of 50 % methanol (v/v) for 40 min at 50 Hz. The extract was centrifuged at 7300 rpm for 10 min. All the supernatant were filtered through a 0.22 µm filter membrane before UHPLC analysis.

2.2 Chemicals and reagents

HPLC-grade methanol and acetonitrile (Fisher, Pittsburg, PA, USA), HPLC-grade formic acid (FA) (Anaqua™, Wilmington, DE, USA), and ultrapure water was prepared by Milli-Q academic ultra-pure water system (Millipore, Milford, MA, USA). Other reagents were analytical grade. Eleven reference standards, including caffeic acid, ferulic acid, isoferulic acid, cimifugin, cimicifugoside, cimifugin-4′-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, cimigenol xyloside, cimigenol-3-O-α-L-arabinoside, cimicidanol-3-O-α-L-arabinoside, acetylcimigenol-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranside, 26-deoxycimicifugoside were purchased from Chengdu Desite Bio-Technology Co., Ltd (Chengdu, China). 2 × Taq PCR Mix, Plant Genomic DNA kit, ddH2O were obtained from Tiangen Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). DNA marker, 6 × loading buffer and GoldView™ were supplied from Takara Biomedical Technology (Beijing) Co., Ltd. The primer was synthesized by Sangon Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China).

2.3 DNA barcoding analysis

Each sample was sprayed by 75 % ethanol solution and gently wiped with degreased cotton to remove impurities. Each sample (0.080 g) was powdered for 10 min at 70 Hz in a tissue grinder (Servicebio, China). After transferring the sample to a new centrifuge tube, the genomic DNA extraction was isolated by Tiangen Plant Genomic DNA kit (Tiangen Biotech, China) with minor modifications. The extracted samples were quantitatively analyzed by NanoDrop spectrometer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA) and stored at −20 °C for later use.

The ITS2 sequences were amplified from genomic DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using universal primers of ITS2F (5′-GCGATACTTGGTGTGAAT-3′) and ITS3R (5′-GACGCTTCTCCAGACTACAAT-3′) (Ren et al., 2014). The PCR was performed in a total volume of 50 μL, containing approximately 50–200 ng template DNA, forward primer (2.5 mM, 2 μL), reverse primer (2.5 mM, 2 μL), 2 × Taq PCR Mix (25 μL), ddH2O added to 50 μL. The PCR conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 5 min; 40 cycles at 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 45 s; 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products (5 μL of each) were detected by electrophoresis on 1.5 % agarose gel in 1 × TAE buffer for 40 min at 80 V. Purified PCR products were sequenced in both directions.

Sequences were assembled by Geneious 9.0.2. Then, the complete ITS2 sequences were annotated and cut based on the ITS2 Database (https://its2.bioapps.biozentrum.uni-wuerzburg.de/). After final alignment in MEGA 6.0, 56 ITS2 sequences were imported into NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to preliminarily determine the species attribution. Genetic distance was calculated based on Kimura 2-parameter (K2P) model to evaluate intraspecific and interspecific variation. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by Neighbor-joining (NJ) method with 1000 bootstrap replications to summarize the genetic relationships.

2.4 UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS analysis

The metabolic characteristics and composition characterization of herbal samples were collected on a 1290 UHPLC system together with a 6520 Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The samples were separated on a ZORBAX Eclipse Plus C18 column (4.6 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm, Agilent Technologies, MD, USA) at 35 °C. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (0.1 % FA-water) and solvent B (acetonitrile) with a gradient elution. The elution gradient of metabolomics was as follows: 0–8 min, 5 %–35 % B; 8–20 min, 35 %–57 % B; 20–40 min, 57 %–81 % B; 40–42 min, 81 %–90 % B. The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min and the injection volume was 3 μL. The other ion source parameters were set as follows: source temperature, 550 °C; drying gas temperature, 325 °C; skimmer voltage, 65 V; fragmentor voltage, 120 V; capillary voltage, 3.5 kV; ion spray voltage, −4.5 kV; collision energy (CE), 10, 35 and 40 V; nebulizer gas pressure, 40 psig; drying gas, N2; gas flow rate, 10 L/min; detection range, m/z 50–1500 in both positive and negative mode.

The DDA mode containing mass range, precursor ion lists (PILs) and static exclusion range lists were used for component characterization. The main different parameters were as follows. According to the organized compounds database, the mass range were set to 100–400 Da, 400–600 Da, 600–700 Da, 700–800 Da, 800–1200 Da in positive mode in order to acquire as much as possible mass spectrometric information, respectively. Furthermore, the molecular weight of the components in CR was mainly concentrated in the range of 400–800 Da, so 400–600 Da, 600–700 Da and 700–800 Da were set to obtain more compound information. The PILs mainly consist of those with low response and the static exclusion range lists were interfering ions (collected in Table S2). The optimal gradient including 0–15 min, 5 %–100 % B; 15–18 min, 100 % B was adopted for component characterization due to its good peak separation effect and more time-saving.

2.5 Quantitative analysis of chemical markers

The quantitative analysis of the herbal samples were acquired by an Ultimate 3000 High Performance Liquid Chromatography with Diode-Array Detection (HPLC-DAD) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). An Agilent Ultimate AQ-C18 (4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μm, Agilent) was used for subsequent analysis. The mobile phase consisted of 0.1 % FA-water (A) and acetonitrile (B), and the optimal gradient conditions were as follows: 0–10 min, 5 %–20 % B; 10–18 min, 20 %–26 % B, 18–28 min, 26 %B; 28–29 min, 26 %–30 % B, 29–35 min, 30 %B; 35–45 min, 30 %–50 %B. The flow rate was set at 1.0 mL/min, the injection volume was 10.0 μL, the column temperature of 30 °C and the detection wavelength was 310 nm.

The quantification method of the potential markers was validated for linearity, precision, repeatability and recovery according to the guiding principle of the validation of analytical methods of Chinese Pharmacopoeia (Yan et al., 2022). The mixed standard solutions of different concentrations were adopted to gain the standard curves. The precision was evaluated by injecting six consecutive needles of the XSM-14 sample. The repeatability of the method was investigated by inspecting six duplicate samples of the XSM-14. The stability of the samples were computed within 24 h. Furthermore, the recovery was measured by adding half amount of the mixed standard solutions into the samples.

2.6 Multivariate statistical analysis

The multivariate statistical analysis mainly included Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Orthogonal Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (OPLS-DA), K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN), Adaptive boosting algorithm (AdaBoost) and Fisher discriminant analysis. Firstly, the data processing and analysis of UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS were carried out by the Agilent MassHunter software B.07.00. Agilent Mass Profinder software (version B.10.00) was applied to peak identify, peak match and then metabolomics variable information was obtained. Secondly, total metabolic variants were used for PCA and OPLS-DA analysis by SIMCA (14.1 version) to classify the 56 batches. Further screening the differential components between C. foetida and C. dahurica (Han et al., 2022). Thirdly, AdaBoost and KNN algorithms were served to calculate the grouping accuracy of the selected markers. Finally, these markers were performed by Fisher discriminant analysis using SPSS software. This model would be applied to distinguish and identify C. foetida and C. dahurica with unknown origin.

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Discrimination of C. foetida and C. dahurica using ITS2 barcoding

PCR amplification was performed after extracting DNA fragments. The PCR results showed that the ITS2 regions of 56 samples were successfully amplified by the universal primers ITS2F/ITS3R (Fig. S1) and high-quality bidirectional sequencing trace files were obtained. After removing the 5.8 s and 28 s rRNA gene sequences at both ends, a total of 56 ITS2 sequences were acquired. Among them, 16 of 56 batches of CR were identified as C. foetida and the rest were C. dahurica. All the sequences were 219 bp in length. According to the analysis of variable sites, C. foetida can be classified into four main haplotypes (F1 ∼ F4), while C. dahurica has three main haplotypes (D1 ∼ D3) (Table 1). The GC-content of C. foetida and C. dahurica were 51.8 %∼53.0 % and 50.2 %∼50.7 %, respectively (Table S3). Note: * it indicated the same base as the first row. Referring to Molecular identification of DNA barcoding in traditional Chinese medicine.

Latin name

Haplotype

variable sites/bp

3

17

32

70

97

105

117

131

146

162

171

175

210

/

Reference

C

T

G

C

G

C

C

T

G

C

A

C

T

C. foetida

F1

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

F2

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

T

*

F3

*

*

Y

*

A

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

F4

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

C

*

*

*

*

*

C.dahurica

D1

*

C

A

R

A

T

T

*

A

A

C

A

G

D2

T

C

A

*

A

T

T

*

A

A

C

A

G

D3

*

C

A

*

A

T

T

*

A

A

C

A

G

In order to construct a consensus phylogenic tree with bootstrap percentages, the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) algorithm was applied to the ITS2 regions using MEGA 6.0 software (Fig. S2). C. foetida and C. dahurica could be clearly distinguished into two groups. Meanwhile, K2P Genetic distance within and between species were calculated by this software. The intra specific distance of C. foetida and C. dahurica from different regions were 0 ∼ 0.0046 and 0 ∼ 0.0093, with an average intra specific distance of 0.0013 and 0.0021, respectively. It indicated that there was a little variation in the genetic process between different regions and also proved that ITS2 sequence, as a DNA barcoding of CR, exhibited good stability. The interspecific distance between the two cultivars of CR was 0.0485, which was far greater than the intraspecific difference (Table S3).

This study requires correct species identification of C. foetida and C. dahurica to ensure accurate elucidation of the chemical differences between the two plants and to discover the impact of species on the quality of medicinal materials. It is usually difficult for inexperienced researchers to employ morphological authentication methods to confirm the original plant species of CR. Recently, DNA barcoding was used to identify accurately the plant species unaffected by external conditions (Gao et al., 2019). Here, the ITS2 regions of 56 samples were successfully amplified and the sequences were obtained. The results showed that the ITS2 could authenticate the original plant species of CR with 100 % success rate. The ITS2 region had the potential to be a good DNA barcoding for identification of medicinal species of CR. It could not provide differences in composition and its content between the two species. Subsequently, the differential components were screened and verified to lay the foundation for further improvement on the quality evaluation of CR based on metabolomics and chemometrics.

3.2 Identification of chemical composition in CR

3.2.1 Strategy for the rapid discovery and identification of compounds

The integrated DDA method (limited mass range, PILs and static exclusion) with CIF system was applied to thoroughly characterize a variety of compounds from CR using UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS. Firstly, the database about the components of CR was established. This allows for the rapid filtration of potential compounds in CR due to the higher matching score between molecular ions and the database. Next, in order to obtain as much as possible mass spectrometric information on the CR, DDA method was conducted. Subsequently, an intelligent data matching platform was created through node server to achieve automatic output of target data. The obtained mass spectrum information were matched with the self-built database through the platform. Following this, the molecular ions were unequivocally screened using the error formula with ppm less than 20. Finally, the screening results were further validated and the structural characterization was accomplished by characteristic diagnostic ion and neutral loss comparing with in-house library (Huang et al., 2022). The total ion chromatograms (TIC) of CR were obtained both in positive and negative ion mode using UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS (Fig. S3). The information of compounds including accurate mass measurements, molecular ions, fragmentation behavior and retention time were shown in Table 2.

No.

Adduct

tR (min)

Formula

Mass

m/z

Error (ppm)

MS/MS Fragments

Identification

c1

[M−H]-

1.77

C11H12O8

272.0532

271.0459

5.66

253.0345,191.0341,179.0334,135.0426

Fukiic acid

c2

[M−H]-

2.23

C11H12O7

256.0583

255.051

3.23

255.0502,211.0620,193.0492,179.0337,165.0468

Piscidic acid

c3

[M + H]+

2.36

C32H42O16

682.2473

683.2546

8.01

682.2683,641.2519,524.2118

(+)-pinoresinol di-O-β-D-allopyranoside

c4

[M−H]-

2.38

C14H20O8

316.1158

315.1085

−4.93

315.1101,153.0543,123.0446

Cimidahurine

c5

[M−H]-

2.51

C14H20O8

316.1158

315.1085

0.45

315.1084,153.0210,123.0441

3,5-dihydroxy-2-[(4-hydroxy phenyl)methyl]butanedioic acid

c6

[M−H]-

2.52

C15H18O9

342.0951

341.0878

2.94

341.0868,179.0343,135.0433

Caffeic acid 4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

c7

[M−H]-

2.59

C11H12O7

256.0583

255.051

0.49

225.0509,117.0344

(2R,3S)-2,3-dihydroxy-2-(4-hydroxybenzyl)succinic acid

c8

[M−H]-

2.97

C13H16O8

300.0845

299.0772

6.14

299.0654,137.0271

4-hydroxybenzoic acid 4-O-β-D-glucoside

c9

[M + H]+

3.35

C31H41NO15

667.2476

668.2549

−5.1

668.2583,506.2126,177.0543,163.0655

Aristomanoside

c10

[M−H]-

3.38

C16H20O9

356.1107

355.1035

8.58

355.1004,193.0455,149.0577

trans-isoferulic acid 3-O-β-D-allopyranoside

c11

[M−H]-

3.42

C8H8O4

168.0423

167.035

0.49

167.0349,139.8804,65.0400

2-methoxy-5-hydroxybenzoic acid

c12

[M + H]+

3.52

C24H29NO9

475.1842

476.1915

−0.82

476.1919,314.1280,177.0532

trans-feruloyl tyramine-4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

c13

[M−H]-

3.53

C9H8O4

180.0423

179.035

4.35

179.0342,135.0428

Caffeic acid

c14

[M + H]+

3.62

C25H31NO10

505.1948

506.2021

1.33

506.2014,237.0759,177.0524,149.0623

Isocimicifugamide

c15

[M + H]+

3.66

C24H29NO10

491.1791

492.1864

−7.69

492.1902,330.1590,177.0542

Cimicifugamide A

c16

[M + Na]+

3.75

C14H20O8

316.1158

339.105

−8.1

339.1076,177.0551,149.0579

Cimidaurinine

c17

[M + H]+

3.87

C22H28O11

468.1632

469.1704

0.51

469.1072,307.1164,289.1061,261.1194,235.0616

Cimifugin-4′-O-β-D- glucopyranosude

c18

[M−H]-

3.89

C16H20O9

356.1107

355.1035

−1.81

355.1041,193.0507,147.0587

trans-isoferulic acid 3-O-β-D-glucopyranosude

c19

[M + H]+

3.96

C26H30O12

534.1737

535.181

−6.17

535.1843,517.2064,491.2913,163.0660

Cimicifugaside F

c20

[M−H]-

4.02

C27H30O15

594.1585

593.1512

6.55

593.1473,355.0981,193.0494,165.0538

Shomaside G

c21

[M−H]-

4.04

C34H46O18

742.2684

741.2611

5.04

741.2574,579.2155,417.1555

(-)-syringaresinol 4,4′-di-O-β-D-allopyranoside

c22

[M−H]-

4.12

C27H30O15

594.1585

593.1512

−4.22

593.1537,193.0476

Shomaside C

c23

[M + H]+

4.12

C24H29NO10

491.1791

492.1864

−0.77

492.1868,330.1425,177.0520,137.0643

Cimicifugamide B

c24

[M + H]+

4.19

C22 H28 O11

468.1632

469.1704

0.51

469.1702,307.1153,259.0920,235.0565

Cimicifugoside

c25

[M + Na]+

4.35

C32H38O17

694.2109

717.2001

−0.4

717.2004,555.1467,523.1406,699.2299,604.3766

Cimicifugaside A

c26

[M + H]+

4.36

C25H31NO10

505.1948

506.2021

−6.19

506.2052,344.1099,177.0519,145.0289

trans-Feruloyl-(3-O-methyl) dopamine-4-O-β-D allopyranoside

c27

[M−H]-

4.38

C27H30O15

594.1585

593.1512

5.88

593.1477,355.0967,237.0345,193.0502

Shomaside B

c28

[M + H]+

4.54

C20H20O7

372.1209

373.1282

−3.82

373.1296,355.2019,325.1049,293.0848,277.1420,265.0941,233.0808,201.0539

Cimicifugic acid

c29

[M + H]+

4.55

C24H29NO9

475.1842

476.1915

−5.67

476.1969,314.1358,177.0515,163.0391

trans-Feruloyl tyramine-4-O-β-D-allopyranoside

c30

[M + H]+

4.60

C16H18O6

306.1103

307.1176

1.68

307.1156,289.1059,259.0592,235.0587,221.0432,177.0531

Cimifugin

c31

[M + H]+

4.61

C25H31NO10

505.1948

506.2021

−8.37

506.2063,344.1337,177.0487,163.0329,145.0227

Cimicifugamide

c32

[M−H]-

4.65

C10H10O4

194.0579

193.0506

4.29

193.0491,178.0257,149.0604,134.0364

Ferulic acid

c33

[M−H]-

4.69

C10H10O4

194.0579

193.0506

8.93

193.0489,167.0357

methyl caffeate

c34

[M + H]+

4.69

C21H26O11

454.1475

455.1548

1.07

455.1543,293.1050,275.1577

prim-O-glucosylangelicain

c35

[M + H]+

4.71

C25H31NO10

505.1948

506.2021

0.34

506.2019,489.0139,344.1506,177.0545,163.0378

(2E)-3-[4-(β-D-allopyranosyl)-3-methoxy-phenyl]-N-[2-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl) ethyl]-2-propenamide

c36

[M−H]-

4.72

C10H10O4

194.0579

193.0506

2.23

193.0502,178.0258,149.0610,134.0863

Isoferulic acid

c37

[M−H]-

4.87

C20H18O10

418.09

417.0827

−7.37

417.0858,237.0412,193.0492,165.0548,149.0615

Cimicifugic acid C

c38

[M−H]-

4.98

C20H18O10

418.09

417.0827

0.53

417.0825,237.0417,193.0490,165.0537,

Cimicifugic acid D

c39

[M−H]-

5.25

C21H20O11

448.1006

447.0933

1.31

447.0927,253.0352,235.0254,209.0442,191.0347,181.0497,165.0547

Cimicifugic acid A

c40

[M−H]-

5.33

C21H20O11

448.1006

447.0933

−2.27

447.0943,253.0355,235.0234,209.0455,191.0345,181.0502,165.0550

Cimicifugic acid B

c41

[M + H]+

5.44

C20H18O10

418.09

419.0973

−4.85

419.0993,401.0775,373.0912,329.0935,257.0742

2-caffeoyl piscidic acid

c42

[M + Na]+

5.57

C41H64O15

796.4245

819.4137

−0.57

819.4142,559.0613,503.3338

Heracleifolinoside C

c43

[M−H]-

5.59

C21H20O10

432.1056

431.0984

2.94

431.0971,237.0387,209.0438,193.0493,178.0257,165.0550,149.0597

Cimicifugic acid E

c44

[M + H]+

5.63

C15H16O6

292.0947

293.102

3.3

293.1010,275.0821,245.0328,233.0495,221.0452,219.0558,207.0241

Norcimifugin

c45

[M−H]-

5.66

C21H20O10

432.1056

431.0984

0.86

431.0980,237.0387,209.0441,193.0495,165.0551,149.0597

Cimicifugic acid F

c46

[M + Na]+

5.67

C35H54O11

650.3666

673.3558

4.97

673.3526,615.3017

15α-hydroxycimicidol-3-O-β-D-xyloside

c47

[M + H]+

5.72

C32H36O14

644.2105

645.2178

−7.32

645.2225,509.1534,469.1760,307.11122,177.0426

cimifugin-4′-O-[6″-feruloyl]-β-D-glucopyranoside

c48

[M + H]+

5.83

C21H20O10

432.1056

433.1129

−4.57

433.1149,389.1560,355.1377,177.0479

2-feruloyl piscidic acid

c49

[M−H]-

5.90

C27H30O16

610.1534

609.1461

6.08

609.1424,193.0474

Shomaside A

c50

[M + H]+

5.92

C18H19NO4

313.1314

314.1387

2.82

314.1378,177.0465,163.0222,149.0488,145.0189,117.0250

Ferulyltyramine

c51

[M + Na]+

5.98

C41H64O15

796.4245

819.4137

0.81

819.4131,559.1653,541.2964,467.2981

Heracleifolinoside A

c52

[M + H]+

6.05

C24H29NO8

459.1893

460.1966

3.47

460.1950,417.1166,298.1331,177.0596

Cimicifugamide D

c53

[M + H]+

6.37

C37H56O11

676.3823

677.3895

7.01

677.3848,467.3134,377.2423

Cimiracemoside A

c54

[M + H]±

6.42

C35H52O9

616.3611

617.3684

−1.44

617.3693,545.3123,467.3172,395.2528,251.1780

cimicidanol-3-O-α-L-arabinoside

c55

[M + H]+

6.45

C32H48O9

576.3298

577.3371

3.83

577.3349,559.3140,517.1793,445.2995, 427.2795

Cimicifugoside H-3

c56

[M−H]-

6.46

C22H22O10

446.1213

445.114

8.12

445.1104,207.0608,193.0439,165.0531,149.0622

Cimicifugic acid L

c57

[M−H]-

6.53

C18H16O7

344.0896

343.0823

2.69

343.0814,193.0496,178.0262,160.0136,149.0267134.0342

4′-Methoxyl-3′-hydroxy-carboxybenzoyl isoferulic acid anhydride

c58

[M + H]+

6.55

C32H48O9

576.3298

577.3371

2.1

577.3359,559.3140,541.2952,429.2795,517.1793,427.2939

Cimicifugoside H-4

c59

[M−H]-

6.55

C11H12O4

208.0736

207.0663

0.4

207.0662,163.1955

Methyl ferulate

c60

[M + H]+

6.56

C35H54O10

634.3717

635.379

1.38

635.3781,485.0014,467.3081,449.3117,377.2644

Cimicifugoside H-2

c61

[M + H]+

6.56

C30H42O5

482.3032

483.3105

8.09

483.3066,467.3124,449.3060,411.2396,395.2576,377.2521

(20R,24R)-24,25-epoxy-11β-hydroxy-7-en-9,19-cyclolanost-3,16,23-trione

c62

[M−H]-

6.59

C19H18O7

358.1053

357.098

5.24

357.0961,193.0462

Cimiracemate B

c63

[M−H]-

6.61

C19H18O7

358.1053

357.098

6.08

357.0958,193.0473

Cimiracemate A

c64

[M + H]+

6.71

C35H54O10

634.3717

635.379

−1.14

635.3797,485.3227,467.3017,395.2483

12β-hydroxy-7,8-didehydro-cimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylranoside

c65

[M + H]+

6.76

C35H54O9

618.3768

619.3841

1.23

619.3833,469.3291,451.3236,379.2673

(23R,24R)-16β,23;16α,24-diepoxy-cycloart-7-en-3β,11β,25-triol 3-O-β-D-xylranoside

c66

[M−H]-

7.02

C37H58O12

694.3928

693.3856

−0.79

693.3861,651.3833,633.3667

Cimidahuside C

c67

[M + H]+

7.03

C35H54O10

634.3717

635.379

0.59

635.3786,485.3494,467.3076

Tetrahydroxy-9,19-cycloart-7-en-16,23-dione 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

c68

[M + H]+

7.04

C37H56O11

676.3823

677.3895

0.35

677.3893,599.3612,581.3361,467.3121,449.3043,431.2786,421.2654

Actein

c69

[M + H]+

7.11

C35H54O10

634.3717

635.379

2.95

635.3771,599.3557,485.3288,467.3103,395.2479

12β-hydroxy-7,8-didehydrocimi-genol3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

c70

[M + H]+

7.25

C35H54O10

634.3717

635.379

−1.62

635.3800,485.3217,467.3205,395.0831

Cimiside A

c71

[M + Na]+

7.27

C37H58O12

694.3928

717.382

6.26

717.3823,587.3430,543.3204,483.3728

24-acetoxy-15,16-seco-cycloar-tane 3-O-xylopyranoside

c72

[M + H]+

7.45

C22H22O10

446.1213

447.1286

0.61

447.1283,429.1161,385.0902,349.0769,177.0519

2-feruloyl-piscidicacid-1-Methyl-ester

c73

[M + Na]+

7.47

C43H70O16

842.4664

865.4556

−1.65

865.4570,601.3193

3-arabinosyl-24-O-acetylhydroxyshengmanol-15-glucoside

c74

[M + H]+

7.48

C32H48O7

544.34

545.3473

5.48

545.3443,485.3156,467.3100,449.2808,413.2753,395.2456,335.0841

Acetylacteol

c75

[M + H]+

7.50

C37H56O11

676.3823

677.3895

0.8

677.3954,617.3755,599.3394,467.3147,449.3014

Cimiracemoside G

c76

[M + H]+

7.51

C37H56O11

676.3823

677.3895

−1.57

677.3906,659.3783,617.3655,599.3597,467.3135,449.3044

Acetylacteol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

c77

[M + Na]+

7.59

C37H60O11

680.4136

703.4028

1.3

703.4019,645.3986,513.3467,495.3471,435.3216,399.2261

24-epi-O-acetylhydro-shengmanol-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

c78

[M + H]+

7.66

C37H56O10

660.3873

661.3946

0.19

661.3945,529.3335,469.3305,451.3191,397.2725,379.2655

23-O-aectyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

c79

[M + Na]+

7.69

C43H68O16

840.4507

863.44

3.88

863.4367,803.4186,641.2327,623.3464

Cimdalglnoside E

c80

[M + Na]+

7.77

C41H64O14

780.4296

803.4188

0.42

803.4185,561.3389,543.3059

Heracleifolinoside B

c81

[M + Na]+

7.78

C37H60O12

696.4085

719.3977

−0.58

719.3981,643.3837,511.3358,493.3408,433.3139,397.2802,379.2629

24-epi-7β-hydroxy-24-O-acetylhydroshengmanol-3-O-xylopyranoside

c82

[M + Na]+

7.85

C43H70O16

842.4664

865.4556

2.5

865.4535,583.1544

3-xylosyl-24-O-acetylhydroxyshengmanol-15-glucoside

c83

[M + H]+

7.86

C39H58O11

702.3979

703.4052

−3.15

703.4074,643.3759,583.6599

15,23-O-diacetyl-7(8)-ene-shengmanol-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

c84

[M + H]+

7.93

C35H54O9

618.3768

619.3841

1.71

619.3830,451.3103,379.2558

7,8-didehydroshengmanol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

c85

[M−H]-

7.93

C35H56O10

636.3873

635.3801

−1.46

635.381,577.3372

7β-hydroxycimigenol-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

c86

[M + Na]+

8.03

C30H48O6

504.3451

527.3343

9.14

527.3297,469.3289,451.3100

11β-hydroxy-24-epi-cimigenol

c87

[M + Na]+

8.05

C35H56O10

636.3873

659.3766

−3.82

659.3790,469.3275,451.3184,433.3022

(22R)-22β-hydroxycimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

c88

[M + Na]+

8.05

C43H70O16

842.4664

865.4556

2.26

865.4537,825.5850

Cimiside C

c89

[M + H]+

8.07

C39H58O11

702.3979

703.4052

0.27

703.4050,643.3757,451.3096,379.2580

Cimiricaside C

c90

[M + H]+

8.12

C37H56O10

660.3873

661.3946

0.79

661.3941,469.3013,451.3275,379.2492

Cimiricaside A

c91

[M + Na]+

8.13

C28H42O5

458.3032

481.2924

0.54

481.2953,399.1479,281.4802,363.1518

Cimilactone C

c92

[M + H]+

8.15

C30H42O6

498.2981

499.3054

−0.57

499.3057,483.3125,481.2667,465.2915,409.2915

1-en-cimigenol-3,11-dione

c93

[M + H]+

8.22

C35H54O9

618.3768

619.3841

0.42

619.3838,583.3763,451.3201,379.2619

7,8-didehydroshengmanol-3-O-β-D-xylranoside

c94

[M + Na]+

8.23

C35H56O10

636.3873

659.3766

−1.46

659.3775,601.3691,583.3649,451.3247,433.3106

12β-hydroxycimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

c95

[M + Na]+

8.25

C41H66O14

782.4453

805.4345

0.48

805.4341,487.3041,379.0277

Cimifoetiside A

c96

[M + Na]+

8.35

C41H66O14

782.4453

805.4345

−0.54

805.4349,729.7225

Cimifoetiside B

c97

[M + Na]+

8.36

C37H58O11

678.3979

701.3871

2.26

701.3856,643.3735,529.2819,397.2894

12β-Acetylcimigenol-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

c98

[M + H]+

8.39

C37H54O10

658.3717

659.379

0.87

659.3784,599.3584,467.3139

26-dedoxycimifugoside

c99

[M + Na]+

8.40

C43H68O16

840.4507

863.44

5.78

863.4351,643.2825,469.3335,451.3321

Heracleifolinoside F

c100

[M + H]+

8.41

C13H13NO

199.0997

200.107

7.99

200.1054,158.0579,130.0633

(E)/(Z)-3-(3′-methyl-2′-butenylidene)-2-indolinone

c101

[M + Na]+

8.43

C35H56O10

636.3873

659.3766

−4.76

659.3796,583.3684,451.3172,433.3026

12β-hydroxycimigenol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

c102

[M + Na]+

8.46

C41H66O14

782.4453

805.4345

6.36

805.4295,673.8314,511.3910

Cimifoetiside A

c103

[M + H]+

8.47

C38H58O11

690.3979

691.4052

−3.78

691.4078,659.4617,599.3723,559.8526,511.7646,163.1092

25-O-acetylcimigenol-galactopyranoside

c104

[M + H]+

8.52

C32H48O6

528.3451

529.3524

2.02

529.3513,511.3381,469.3312,493.3319,451.3220,397.2712

27-deoxyacetylacteol

c105

[M + H]+

8.62

C37H56O10

660.3873

661.3946

−0.87

661.3952,583.3620,529.3126,469.3300,451.3209

27-deoxyactein

c106

[M + Na]+

8.64

C35H56O9

620.3924

643.3817

1.54

643.3773,585.3712,453.3242,435.3182

Cimigenol-3-O-α-L-arabinoside

c107

[M + Na]+

8.65

C37H58O11

678.3979

701.3871

1.67

701.3875,433.3021

Cimiracemoside D

c108

[M + Na]+

8.72

C41H70O15

802.4715

825.4607

0.49

825.4603,663.4025,441.1997

Foetidinoside E

c109

[M + H]+

8.74

C37H54O9

642.3768

643.3841

−1

643.3847,583.3607,451.3196,73.0299

Asiaticoside B

c110

[M + H]+

8.81

C35H56O9

620.3924

621.3997

8.24

621.3946,603.3767,531.6037,399.7340

Cimidahuside G

c111

[M + Na]+

8.89

C35H56O9

620.3924

643.3817

−4.59

643.3845,511.3371,493.3290,433.3077

9,19-cyclolanostan-15-one,16,23-epoxy-24,25-dihydroxy-3-O-β-D-xylopyranosyloxy

c112

[M + Na]+

8.93

C30H46O6

502.3294

525.3187

−5.25

525.3213,467.3202,449.7901

12β-hydroxy-7(8)-ene-cimigenol

c113

[M + H]+

9.05

C37H56O11

676.3823

677.3895

2.72

677.3877,659.3754,467.3147,395.2513

(23R,24R)-16β;16α,24-diepoxy-3β,15α,24,25-tetrahydroxy-cycloart-7-en-16-one 3-O-β-D-xylranoside

c114

[M + Na]+

9.06

C38H62O12

710.4241

733.4133

0.63

733.4129,521.2268,274.0174

24-O-acetylhydroshengmanol-15-O-β-D-glucopyranoside

c115

[M + Na]+

9.23

C35H54O9

618.3768

641.366

−1.61

641.3670,583.3652,451.3157,433.3131

7,8-didehydrocimigenol-3-O-β-D-xyloside

c116

[M−H]-

9.31

C35H56O10

636.3873

635.3801

−0.52

635.3804,577.3451

7β-hydroxycimigenol-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

c117

[M + Na]+

9.34

C35H54O9

618.3768

641.366

0.65

641.3656,583.3589,451.3095,433.1967

24-epi-7,8-didehydrocimigenol-3-O-β-D-xyloside

c118

[M + H]+

9.40

C35H54O8

602.3819

603.3891

2.07

603.3879,471.3451,453.3358

cimiside E

c119

[M + H]+

9.43

C37H58O10

662.403

663.4103

−1.4

663.4112,585.3743,453.3183,381.2805

25-O-acetylcimigenol-3-O-α-L-arabinoside

c120

[M + H]+

9.52

C35H54O9

618.3768

619.3841

−0.87

619.3846,583.3537,469.3257,451.3184,379.2622

24-epi-7,8-didehydroshengmanol 3-O-β-D-xylranoside

c121

[M + Na]+

9.56

C37H58O11

678.3979

701.3871

−2.01

701.3885,583.3498,451.3028

9,19-cyclocholest-7-en-16-one,23–(acetyloxy)-15,24,25-trihydroxy-4,4,14-trimethyl-3-(β-D-xylopyranoside)

c122

[M + H]+

9.58

C35H52O8

600.3662

601.3735

−0.67

601.3739,469.3987,451.3113

7,8-didehydro-25-anhydrocimigenol-3-O-β-D-xyloside

c123

[M + Na]+

9.61

C37H60O11

680.4136

703.4028

−0.91

703.4034,645.3696,471.7697

24-epi-O-acetylhydroshengmanol-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

c124

[M + H]+

9.62

C37H56O10

660.3873

661.3946

−2.54

661.3963,529.3515,397.2755,379.2629

23-O-aectyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol 3-O-β-D-xylranoside

c125

[M + Na]+

9.64

C35H54O9

618.3768

641.366

1.79

641.3649,583.3639,451.3110,433.2977,361.2561

Cimiaceroside A

c126

[M + Na]+

9.64

C35H56O9

620.3924

643.3814

0.41

643.3773,585.3744,453.3264,435.3205

Cimigenol-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

c127

[M + Na]+

9.67

C30H48O5

488.3502

511.3394

−4.31

511.3415,453.3361,381.2701

Cimiacerin B

c128

[M + Na]+

9.80

C37H58O11

678.3979

701.3871

−3.49

701.3895,643.3696,625.3705,583.3683,469.2717,433.3019,397.2851

24-O-acetyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

c129

[M + H]+

9.83

C37H58O10

662.403

663.4103

−1.4

663.4112,435.3290

25-O-acetylcimigenol-3-O-β-D-xyloside

c130

[M + Na]+

9.98

C37H58O11

678.3979

701.3871

2.41

701.3855,643.3840,625.3740,583.3918,511.2949,451.3176,433.3107

24-epi-24-O-acetyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

c131

[M + H]+

9.99

C35H54O8

602.3819

603.3891

2.9

603.3874,471.3447,453.3337

25-anhydrocimigenol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

c132

[M + Na]+

9.99

C38H60O12

708.4085

731.3977

3.95

731.3949,671.3772,437.2936

Shengmaxinside C

c133

[M + H]+

10.10

C40H58O13

746.3877

747.395

0.69

747.3945,729.3976,663.6121,645.2409,585.1133,399.2086,459.1257

23-O-acetyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol-3-O-(2′-O-malonyl)-xylopyranoside

c134

[M + Na]+

10.14

C37H60O11

680.4136

703.4028

1.89

703.4015,513.6137,453.3278,435.3353

24-O-acetylhydroshengmanol 3-O-β-D-xylranoside

c135

[M + Na]+

10.15

C37H58O10

662.403

685.3922

−3.14

685.3943,417.3166

23-O-aectylshengmanol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

c136

[M + H]+

10.17

C37H56O10

660.3873

661.3946

0.34

611.3944,511.3401,451.3112

25-O-aectyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol 3-O-β-D-xylranoside

c137

[M + Na]+

10.22

C30H48O6

504.3451

527.3343

−0.77

527.3347,451.3041,379.2504

12β-hydroxycimigenol

c138

[M + Na]+

10.25

C30H46O6

502.3294

525.3187

−1.07

525.3192,509.2741,469.3266,451.3043,395.2541,377.2413

25-O-methylisodahurinol

c139

[M + Na]+

10.47

C37H58O10

662.403

685.3922

−0.42

685.3925,585.2524,453.0838,435.3009

23-O-aectylshengmanol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

c140

[M + H]+

10.69

C39H60O11

704.4136

705.4208

0.91

705.4202,687.4135,672.9728,663.4734,654.9314,576.4683,175.0611,97.0278

Cimicifoetiside B

c141

[M + H]+

10.95

C30H46O5

486.3345

487.3418

−1.85

487.3427,451.3097

Acerinol

c142

[M + Na]+

10.98

C38H60O12

708.4085

731.3977

5.22

731.3940,709.3753,671.3772

24-epi-24-O-acetyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol-3-O-β-D-galactopyranoside

c143

[M + Na]+

11.12

C30H46O5

486.3345

509.3237

4.41

509.3216,487.7508,451.3296

7,8-didehydrocimigenol

c144

[M + Na]+

11.32

C30H46O5

486.3345

509.3237

2.36

509.3226,451.3224,433.3098

24-epi-7,8-didehydrocimigenol

c145

[M + H]+

11.32

C37H56O10

660.3873

661.3946

2.01

661.3933,583.3693,511.3364,451.3220,397.2752,379.2606

25-O-aectyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

c146

[M + Na]+

11.47

C30H48O5

488.3502

511.3394

4.5

511.3372,453.3105

Cimigenol

c147

[M + H]+

11.52

C30H46O4

470.3396

471.3469

4.65

471.3447,453.3372,435.3134,399.5863

25-dehydrocimigenol

c148

[M + H]+

11.55

C37H58O10

662.403

663.4103

−1.4

663.4112,585.3681,435.3177,399.2918,363.2552

23-O-acetylcimigenol-3-O-α-L-arabinoside

c149

[M + Na]+

11.57

C30H46O5

486.3345

487.3418

0.62

487.3415,433.2859

24-epi-acerinol

c150

[M + Na]+

11.60

C33H52O7

560.3713

583.3605

0.76

583.3601,565.3556,451.3165,433.3082,415.2965

24-O-acetyl-25-O-methyl-7,8-didehydrohydroshengmanol

c151

[M + H]+

11.87

C30H44O5

484.3189

485.3262

4.65

485.3239,467.3118,449.2977,431.2894,413.2660,395.2549

Cimicidanol

c152

[M + H]+

12.42

C32H48O6

528.3451

529.3524

0.88

529.3519,511.3238,451.3170,379.2641

24-O-acetylshengmanol-7(8)-en-isodahurinol

c153

[M + Na]+

12.77

C30H48O5

488.3502

511.3394

−1.85

511.3403,453.3288

24-epi-cimigenol

c154

[M + H]+

13.22

C30H46O5

486.3345

487.3418

−1.85

487.3427,451.3375,433.3026,379.2639,361.2381

Cimigenol-3-one

c155

[M + H]+

13.52

C32H48O6

528.3451

529.3524

−0.25

529.3525,511.4804,493.2909,469.3150,451.3273,379.2400

25-O-acetyl-7,8-didehydrocimigenol

c156

[M + Na]+

13.52

C32H50O7

546.3557

569.3449

0.69

569.3445,551.3723,491.4781

12β-acetoxycimigenol

c157

[M + Na]+

14.13

C32H50O6

530.3607

553.35

0.3

553.3481,493.3280,439.3307

25-O-acetylcimigenol

3.2.2 Identification of triterpenoid saponins

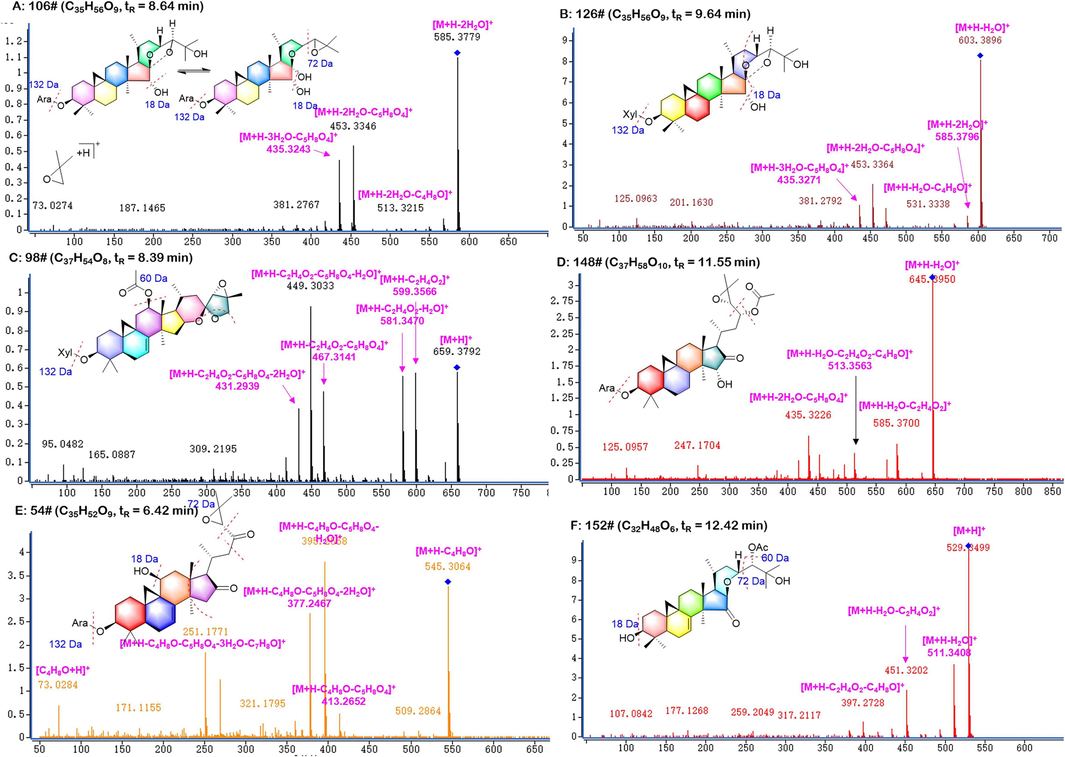

Triterpenoid saponins were the primary bioactive components of CR. Up to date, approximately 400 triterpenoid saponins (mostly 9,19-cycloartane type) had been discovered and characterized from the Cimicifuga genus. In our study, total 101 constituents had been identified by means of UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS based on the above approach. Most triterpenoid saponins were liable to form [M + H]+ ion and [M + Na]+ ion in positive mode. The main cleavage pathways of triterpenoid saponins were prone to lose water, acetyl groups, dimethylethylene oxide and the glycosyl groups, resulting in neutral losses of 18.01 Da, 60.02 Da, 72.01 Da, 132.05 Da, 162.05 Da. The following were examples of the conventional fragmentation pathways for triterpenoid saponins.

The main cleavage pathway of cimigenol-type of triterpenoid saponins was to lose water, the glycosyl groups and was prone to twist to form dimethylethylene oxide. Compound c106 cimigenol-3-O-α-L-arabinoside had a [M + Na]+ peak at m/z 643.38 (1.54 ppm). Then m/z 585.37 ([M + H − 2H2O]+) and m/z 453.32 ([M + H − 2H2O − Ara]+) were formed after successively removing two molecules of water (36.02 Da) and arabinose (132.05 Da). And m/z 435.31 ([M + H − 3H2O − Ara]+) was also detected after removing a molecule of water (Fig. 2). In the positive mode, the precursor ion of compound c126 cimigenol-3-O-β-D-xyloside was m/z 643.38 [M + Na]+, and the molecular formula was presumed to be C35H56O9. m/z 567.36, m/z 495.35, m/z 363.26 were generated successively with continuous water loss, dimethylethylene oxide and xylopyranose. Compound c69 12β-hydroxy-7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside had a [M + H]+ at m/z 635.37 (2.95 ppm). In the secondary mass spectrometry, fragments of m/z 617.37 [M + H − H2O]+, m/z 599.36 [M + H − 2H2O]+, m/z 545.31 [M + H − H2O − C4H8O]+, m/z 467.31 m/z [M + H − 2H2O − Ara]+ and m/z 377.26 [M + H − 3H2O − Ara − C4H8O]+ were produced (Pang et al., 2021).

Illustration for the structural elucidation of triterpenoid saponins CR.

The main feature of 16,23-diketo-type is that the C-16 and C-23 positions both are oxidized to carbonyls, and partially dehydrated to form a ternary oxygen ring structure at C-24 and C-25 positions. Therefore, this type of compounds is extremely easy to remove dimethylethylene oxide and produce highly responsive m/z 73 [C4H8O + H]+. The [M + H]+ peak of compound c54 cimicidanol-3-O-α-L-arabinoside was at m/z 617.36 (−1.44 ppm). Aglycones were produced with dimethylethylene oxide, arabinose and continuous water losses to generate fragments of m/z 545.31 [M + H − C4H8O]+, m/z 467.31 [M + H − H2O − Ara]+, m/z 395.25 [M + H − H2O − C4H8O − Ara]+ and m/z 251.17 [M + H − 3H2O − C4H8O − Ara − C7H8O]+ (Fig. 2). From above, compound c151 was speculated as cimicidanol according to the fragments of m/z 485.32 [M + H]+, m/z 413.27 [M + H − C4H8O]+, m/z 395.25 [M + H − H2O − C4H8O]+. Compound c60 was identified as cimicifugoside H-2 (tR = 6.561, C35H54O10), as lost a xylopyranose (132.05 Da) and a molecule of dimethylethylene oxide (72.01 Da) and continuous water (n∙18.01 Da) at positive conditions (Cao et al., 2005, Li et al., 2007).

Shengmanol-type of Cimicifugae Rhizoma contains acetyl groups and dimethylethylene oxide at the end of carbon chain, which are easily lost in secondary mass spectrometry. The MS2 spectrum of 23-O-acetylcimigenol-3-O-α-L-arabinoside (consistent with peak 148, tR = 11.55 min) was showed the precursor ion at m/z 663.41 [M + H]+. The fragments at m/z 585.36 and 435.31 indicated the elimination of C2H4O2, Ara and three molecules of water. A serious of fragments at m/z 529.3, 469.3, 451.3, 397.2 were both found in peak 78 and 152, indicating that those two compounds had the same skeleton and highly similar in structures. Therefore, they were identified as 23-O-aectyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside and 24-O-acetylshengmanol-7(8)-en-isodahurinol, respectively.

3.2.3 Identified of phenylpropanoids

A total of 49 phenylpropanoids were tentatively identified in the positive and negative mode. The compound of c13, c32 and c36 were orderly identified as caffeic acid, ferulic acid and isoferulic acid by comparing the authentic standards, which cleavage pathways were specified in Fig. 3. The fragment of phenolic acids was characterized by neutral losses of 15.02 Da (–CH3), 18.01 Da (–H2O) and 44.01 Da (–CO2). Based on the same fragment ions m/z 179.03,135.04 as caffeic acid, peak 6 (tR = 2.518 min, C15H18O9) was characterized as caffeic acid 4-O-β-D-glucopyranoside.

Illustration for the structural elucidation of phenylpropanoids and chromones from CR.

Cimicifugic acids mainly generate signal responses in positive ion mode and were prone to neutral losses such as CO2, CO, H2O, and CH3. Due to the carbon chains of these components contained hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, they were easy to fracture on the carboxyl group oxygen in collision energy spectra. A fragment response at m/z 177 was likely to occur when methoxy group was present on the benzene ring at the same time. Peak 19 (tR = 3.96, C26H30O12) was regarded as cimicifugaside F attributing to the fragment ions m/z 535.18, m/z 517.21, m/z 491.29 and m/z 163.07. According to the ions m/z 433.11, m/z 389.16, m/z 355.14, m/z 177.05, peak 48 (tR = 5.83, C21H20O10) was identified as 2-feruloyl piscidic acid. Compared with the literature, peaks 1, 2, 39 and 40 were successively identified as fukiic acid, piscidic acid, cimicifugic acid A and cimicifugic acid B (Werner and Petersen, 2019).

3.2.4 Identification of chromones

The primary type of chromones was furan chromones with methoxy, hydroxyl and glucose substituents. Compound c30 was regarded as cimifugin, displayed a precursor ion [M + H]+ at m/z 307.12; the main fragment ions were observed at m/z 289.11 [M + H − H2O]+, m/z 259.06 [M + H − H2O − 2CH3]+ and m/z 235.06 [M + H − C4H8O]+. The derivatives of cimifugin were liable to remove a molecule of sugar to produce m/z 307. According to the fragment ions m/z 307, m/z 289, m/z 259, m/z 235, peak 17 and 24 were identified as cimifugin-4′-O-β-D-glucose and cimicifugoside consistent with the standards’ ions. In the meantime, 14 Da difference was detected between cimifugin and peak 43 (C15H16O6). It was explicitly identified as norcimifugin with the same natural losses H2O, C3H6O, C2H2, CH2.

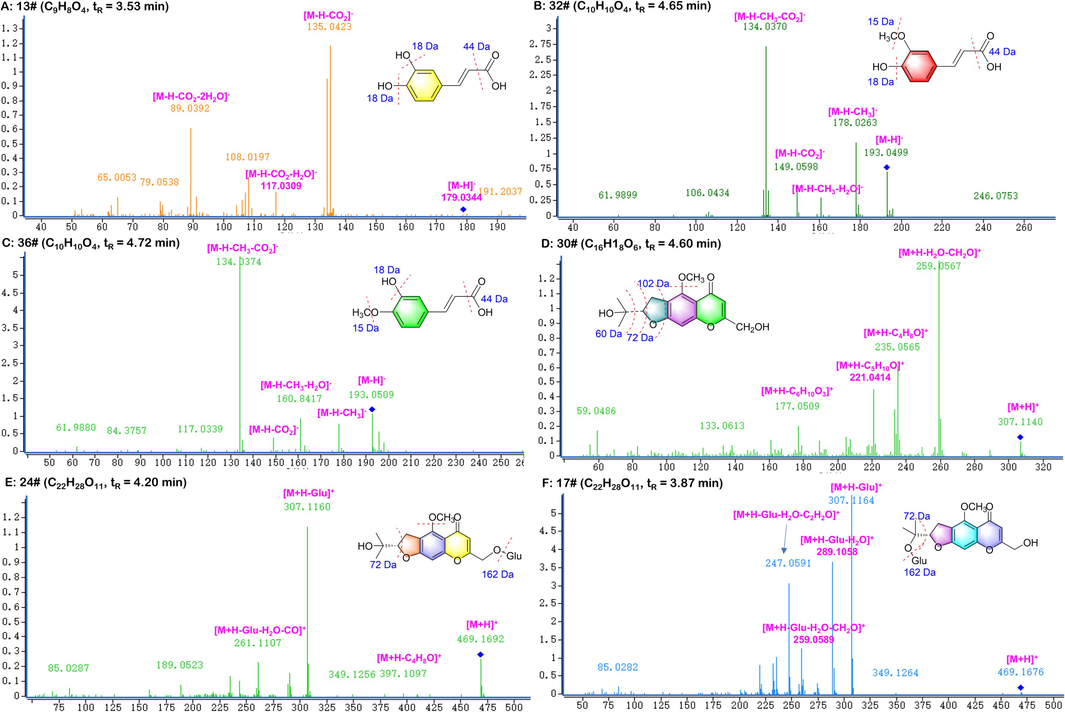

3.2.5 Identification of compounds in C. foetida and C. dahurica

The chemical compositions identification of C. foetida and C. dahurica was a basis for screening potential differential components. The TIC of the two species both in positive and negative modes were shown in Fig. 4. In this work, a total of 88 chemical components were ultimately authenticated in the methodology of metabolomics referring to the above qualitative analysis, including 65 from C. foetida and 75 from C. dahurica (Table S4). According to the constituents identified from the two species, there were significant differences in composition and content between them.

The total ion chromatograms (TIC) of the two species in positive and negative modes. (A) TIC of C. dahurica in positive MS mode; (B) TIC of C. dahurica in negative MS mode; (C) TIC of C. foetida in positive MS mode; and (D) TIC of C. foetida in negative MS mode.

A comprehensive insight into the secondary metabolites of various species in TCMs is vital for further metabolomics analysis. The DDA mode could maximize the MSn information collection, greatly reducing the difficulty of acquiring low abundant components (Zuo et al., 2019). And the CIF platform was established to rapidly analyze and match a compound from a large amount of MSn information during the data processing stage. Based on this, a total of 157 compounds were tentatively characterized in CR, including 101 triterpenoid saponins, 44 phenylpropanoids and 7 chromones. Compared with previous composition analysis methods, this strategy is more rapid, accurate and efficient, which could become the principal method to identify compounds soon. Furthermore, strengthening this method development and application to provide a practical strategy for characterizing non-targeted metabolites in TCMs.

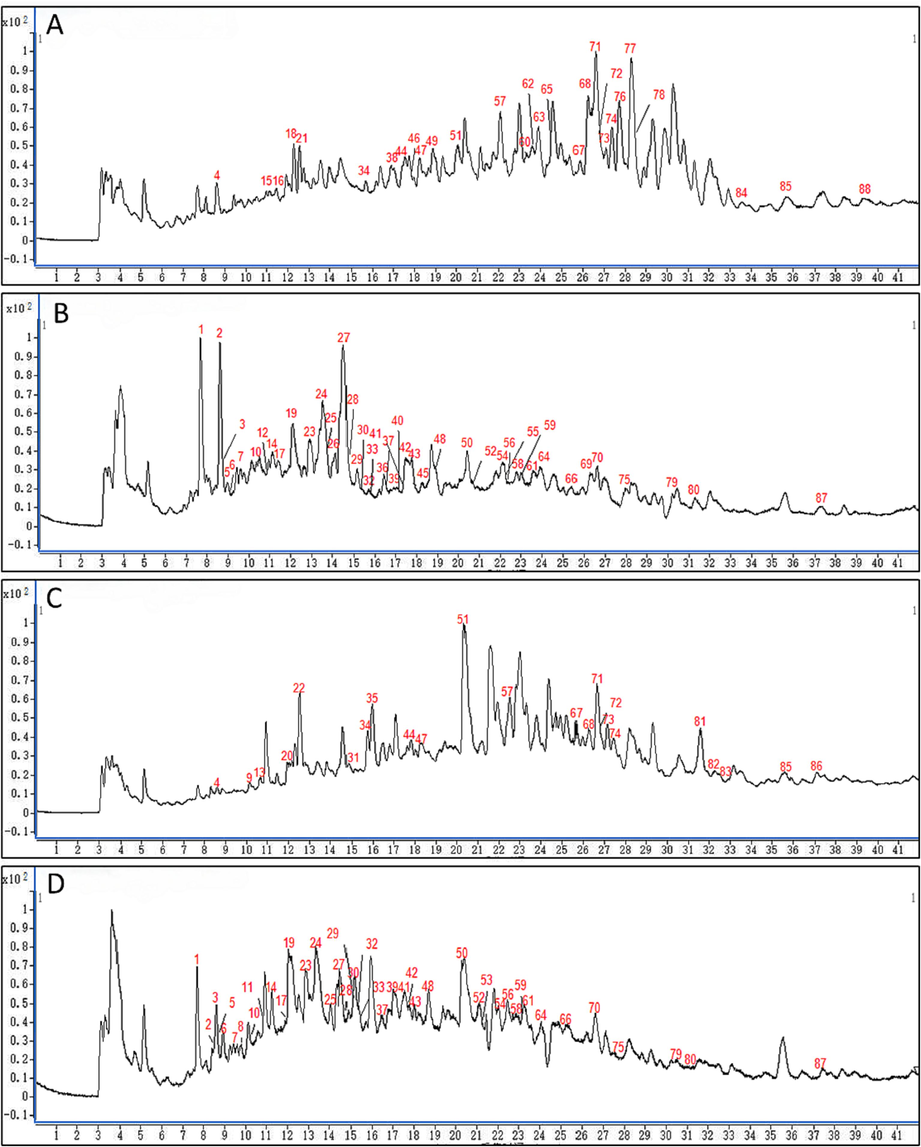

3.3 Metabolomic analysis for discrimination of C. foetida and C. dahurica

The retention time and peak area of ten randomly selected ion pairs in QC samples were acquired to verify the UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS method. The relative standard deviations (RSDs) of them were less than 5.0 %, indicating the accuracy and reliability of this analytical method. All QC samples were closely clustered into a group in PCA, demonstrating the reproducibility of the analytical system (Fig. 5A and B).

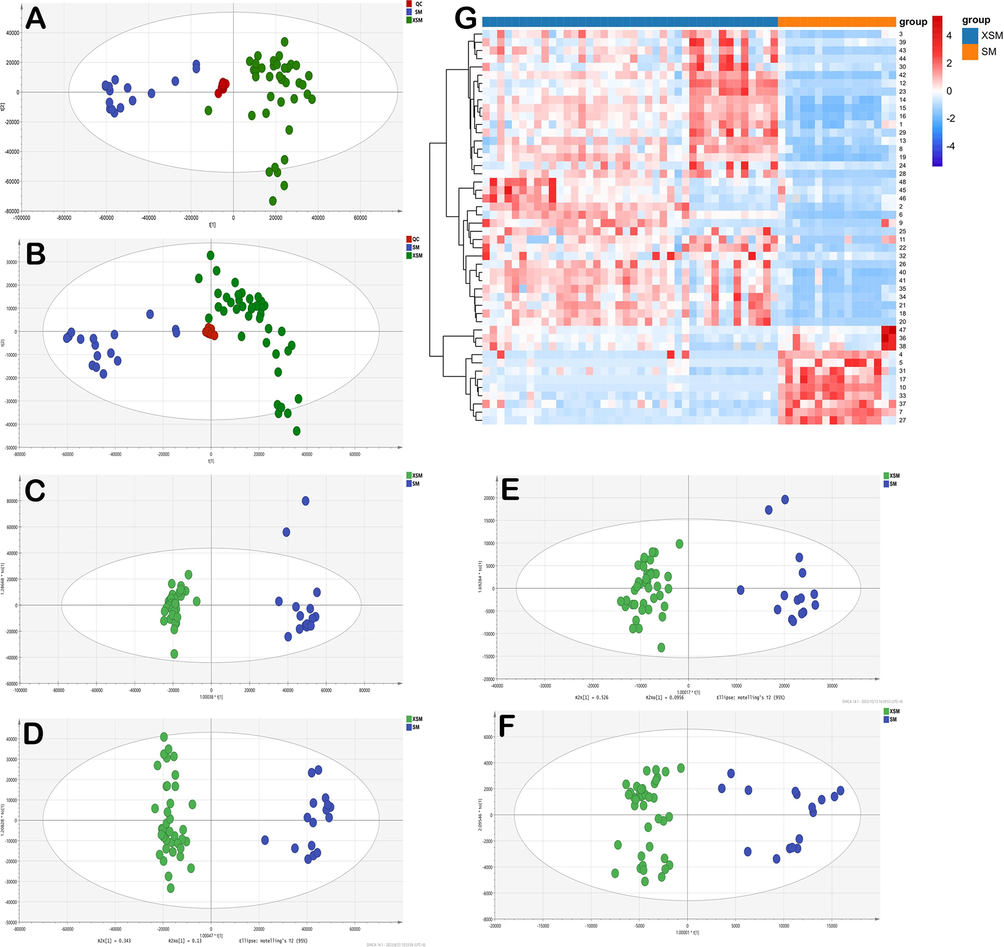

Multivariate statistical analyses of the two species: PCA score plot in positive mode (A); PCA score plot in negative mode (B); OPLS-DA score plot (C: 2955 ionic characteristic variables in positive mode, D: 2976 ionic characteristic variables in negative mode, E: 48 compounds characteristic variables, F: 4 combinatorial discriminatory quality markers); heat-map in two species(G).

Metabolomics analysis exhibited excellent properties on screening the differential components in natural products. Total 2955 and 2976 ionic characteristic variables were obtained in positive and negative mode, respectively. The unsupervised model PCA and supervised model OPLS-DA were performed to differentiate the two species in metabolite levels with high fitting and prediction degree. The results showed that the samples from the two species were successfully separated into two distinct clusters in PCA with high fitting and predictive abilities both in positive and negative mode (Fig. 5A and B). The 2955 metabolic variables in positive mode were evidently classified the samples into two groups with a goodness-of-fit R2Y = 0.983 and goodness-of-prediction Q2 = 0.95 (Fig. 5C). The 2976 metabolic variables in negative mode had the similar result with R2Y = 0.972 and Q2 = 0.935 (Fig. 5D). To better classify and account for the two species, variable importance in projection (VIP) combined with t-test were applied in OPLS-DA mode for significance testing. In this work, about 48 distinctive components were screened and identified between the two species based on analyzing the criteria of VIP > 1 and p < 0.05, including triterpenoid saponins, phenylpropanoids and chromones (Table 3). The 48 compounds characteristic variables could distinguish the samples into two groups in OPLS-DA model (Fig. 5E) and the results were visualized in the Heatmap (Fig. 5G). Among these compounds, the content of 12 components, such as cimifugin-4′-O-β-D-glucose (4), cimicifugoside (5), caffeic acid (7), cimifugin (10), norcimifugin (17) and 26-dedoxycimifugoside (31) were generally higher in C. foetida, while others were higher in C. dahurica. All of the above highlighted significant differences in composition and content between C. foetida and C. dahurica. In addition, relevant studies have shown that C. foetida has significant effects in antidiarrheal, anticomplementary and menopausal syndrome effects (Qiu et al., 2006, Zheng et al., 2013, Zhang et al., 2016), while C. dahurica has better antioxidant, neuroprotective and antibacterial effects (Qin et al., 2016, Lee et al., 2020, Li et al., 2023). Therefore, it is necessary to conduct differential analysis between the two species in order to apply it more clearly in clinical practice.

No.

Component

VIP

p values

1

Fukiic acid

5.36

2.35E-06

2

Methyl caffeate

1.11

1.97E-04

3

Shomaside A

1.47

2.70E-06

4

Cimifugin-4′-O-β-D-glucose

2.39

6.58E-07

5

Cimicifugoside

5.32

1.28E-07

6

Shomaside G

3.06

4.35E-11

7

Caffeic acid

3.08

4.91E-21

8

Isocimicifugamide

1.35

4.61E-10

9

Shomaside B

1.05

1.05E-03

10

Cimifugin

9.99

1.06E-14

11

Cimicifugic acid A/B

3.57

6.83E-03

12

2-feruloyl fukinolic acid-1-metyl ester

1.63

9.27E-06

13

Ferulic acid

3.49

8.31E-06

14

Isoferulic acid

4.03

1.57E-10

15

Cimicifugic acid E/F

7.70

8.67E-16

16

Cimicifugic acid E/F

2.70

1.76E-13

17

Norcimifugin

3.13

2.36E-11

18

12β-acetylcimigenol-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

2.18

3.01E-08

19

Cimicifugic acid L

2.28

4.62E-17

20

9,19-cyclocholest-7-en-16-one,23–(acetyloxy)-15,24,25-trihydroxy-4,4,14-trimethyl-3-(β-D-xylopyranoside)

2.04

7.58E-07

21

Cimicifugoside H-2

3.10

1.06E-08

22

23-O-aectyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol 3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

1.67

4.18E-07

23

Actein

2.19

1.43E-07

24

Cimiracemoside A

1.26

1.87E-02

25

7β-hydroxycimigenol-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

5.34

2.21E-05

26

12β-hydroxycimigenol-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

5.96

8.52E-08

27

24-epi-24-O-acetyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol-3-O-β-D-galactopyranoside

1.43

1.38E-13

28

7,8-didehydrocimigenol 3-O-β-D-xyloside

4.53

5.59E-09

29

7β-hydroxycimigenol-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

2.60

1.65E-05

30

(22R)-22β-hydroxycimigenol 3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

2.12

6.39E-03

31

26-dedoxycimifugoside

3.15

1.14E-08

32

7,8-didehydroshengmanol-3-O-β-D-xylranoside

1.09

1.56E-02

33

Cimiricaside A

5.43

1.26E-12

34

12β-hydroxycimigenol-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

1.06

2.22E-06

35

asiaticoside B

6.55

8.90E-08

36

25-O-acetylcimigenol-3-O-β-D-xyloside

2.69

2.56E-02

37

25-O-acetylcimigenol-3-O-α-L-arabinoside

2.26

8.11E-08

38

Cimiside E

2.24

1.06E-02

39

7,8-didehydro-25-anhydrocimigenol-3-O-β-D-xyloside

5.18

2.00E-02

40

Cimiricaside C

1.78

2.93E-09

41

24-O-acetyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

4.72

2.59E-07

42

23-O-aectyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol 3-O-β-D-xylranoside

1.27

1.06E-12

43

23-O-acetyl-7,8-didehydroshengmanol-3-O-(2′-O-malonyl)-xylopyranoside

6.43

1.19E-06

44

15,23-O-diacetyl-7(8)-ene-shengmanol-3-O-α-L-arabinopyranoside

2.25

1.55E-03

45

11β-hydroxy-24-epi-cimigenol

1.13

2.87E-02

46

24-O-acetylshengmanol-7(8)-en-isodahurinol

2.09

1.56E-02

47

25-O-acetylcimigenol

1.45

9.47E-03

48

12β-acetoxycimigenol

1.40

2.18E-03

Considering the above content differences and the screening principle of biomarkers: 1) the markers are convenient to obtain and quantify; 2) the markers can clearly distinguish between the two original CR; 3) the specific components in CR (Cui et al., 2022, Lu et al., 2022). Caffeic acid, cimifugin, ferulic acid and isoferulic acid were ultimately screened as potential combinatorial discriminatory quality markers. The two species were significantly divided into two groups by the four markers in OPLS-DA model with high fitting and predictive abilities (Fig. 5F). Furthermore, the grouping accuracy were verified based on AdaBoost and KNN algorithms by Matlab R2022A software. The sample SM-1, 4–14, XSM-1, 2, 7–25 were screened as the training set while others were the testing set at random. The accuracy of variables in different groups were above 83.3 %, which proved the correctness of OPLS-DA model grouping and verified the existence of differences between the two Cimicifuga species (Table 4).

Algorithms

Different amounts of variables

2955 (+)

2976 (−)

48

4

AdaBoost

87.5 %

95.8 %

83.3 %

95.8 %

KNN

91.7 %

91.7 %

100 %

91.7 %

3.4 The verification of the potential bioactive markers

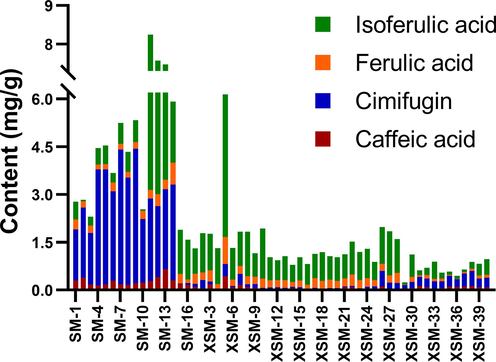

Four combinatorial discriminatory quality markers were quantitatively analyzed by HPLC-DAD with high efficiency and generality. It was indicated that the contents of the four markers from 56 batches were totally different, which may contribute to the differentiation of the species. The repeatability, stability and precision of the four compounds were less than 5.0 % and recoveries were between 96.1 % and 103 % with all RSD values less than or equal to 5.55 %. The correlation coefficients of the linear equations higher than 0.99 and the lower limit of quantitation (LOQ) were 0.08 μg/mL of caffeic acid and cimifugin, 0.048 μg/mL of ferulic acid and 0.16 μg/mL of isoferulic acid, respectively (Table S5). It demonstrated a good linear relationship between these four compounds within their respective concentration ranges. The content of four combinatorial discriminatory quality markers of 56 batches were obtained (Table S6) and the intuitive chart was shown in Fig. 6. In summary, the established HPLC-DAD quantitative analysis for four markers was unequivocally accurate and reliable.

The contents chart of four markers in all batches of samples.

Fisher discriminant model was established to classify unknown samples using SPSS software in terms of the above contents of four combinatorial discriminatory quality markers. The twenty batches (including SM-2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 13, 14, XSM-2, 10, 14, 15, 17, 18, 21, 22, 24, 28) were randomly chosen as training sets and the fifteen batches (SM-1, 10, 15, XSM-1, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 16, 19, 23, 25) were test sets. The discriminant equation was derived as follows: Y = 7.029X1 + 1.637X2 − 0.193X3 − 0.125X4 − 3.613 (Y: discriminant score; X1: caffeic acid; X2: cimifugin; X3: ferulic acid; X4: isoferulic acid). The unknown samples will be classified as C. foetida when the discriminant score is higher than the determination value 0 (the average of 3.188 and −3.188 at the group centroids), if not it will be considered as C. dahurica. In addition, the other 21 batches were utilized to the test sets in order to verify the discrimination ability. The results displayed that the accuracy of classification was 94.4 % in cross-validation group demonstrating high feasibility of this model. The batches were correctly grouped by the discriminant model except two samples. Apart from a little higher content of isoferulic acid, the other three components are generally lower in the two batches.

It was suggested that the four combinatorial discriminatory quality markers could distinguish C. foetida and C. dahurica with high accuracy. The content of ferulic acid in C. foetida was higher than that in C. dahurica, while isoferulic acid was the opposite. Caffeic acid was three times higher in C. foetida than in C. dahurica. Moreover, cimifugin was significantly different between the two species, and it was nearly 16 times higher in C. foetida than in C. dahurica. These differences in the composition of secondary metabolites might be attributed to genetic nuances. Consequently, the contents of four markers will be measured and substituted into the discrimination model so as to differentiate the unknown samples. All above indicated that metabolomics techniques can be applied to distinguish different species from the perspective of compositional differences.

4 Conclusion

This study presented an integrated technique to differentiate closely related TCMs as a case of C. foetida and C. dahurica cultivars based on DNA barcoding and metabolomics by UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS. After obtaining the useable DNA sequences, the sequence similarity of ITS2, genetic distance and phylogenetic tree were examined using DNA barcoding technology. As a result, C. foetida and C. dahurica were identified by the variation sites of ITS2 in terms of genetic features. One hundred and fifty-seven chemical components were characterized by UHPLC-Q-TOF-MS in DDA scanning mode. There were forty-eight differential components between C. foetida and C. dahurica. Four of them were totally screened and validated as combinatorial discriminatory quality markers for the differentiation of the two species. It was concluded that the DNA barcoding combined with metabolomics technique was verified to discriminate the original plant species of CR. The technique provides a method to comprehensively and accurately screen differential components of the similar species of CR, and is expected to play an extremely important role in the classification and identification of TCMs in future research.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Qianqian Zhang: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Data curation. Shujing Chen: Methodology, Software. Jiake Wen: Conceptualization, Data curation. Rui Wang: Validation, Visualization. Jin Lu: Conceptualization. Abdulmumin Muhammad-Biu: Methodology. Shaoxia Wang: Resources. Kunze Du: Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Project administration. Wei Wei: Formal analysis. Xiaoxuan Tian: Resources. Jin Li: Resources. Yanxu Chang: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing, Project administration.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Program of Tianjin in China (23ZYJDSS00030), and Special Program of Talents Development for Excellent Youth Scholars in Tianjin

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Metabolomics and DNA-based authentication of two traditional asian medicinal and aromatic species of Salvia subg. Perovskia. Cells. 2021;10

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Non-target metabolomics based on high-resolution mass spectrometry combined with chemometric analysis for discriminating geographical origins of Rhizoma Coptidis. Microchem. J.. 2021;160

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization and quantification of ginsenosides from the root of Panax quinquefolius L. by integrating untargeted metabolites and targeted analysis using UPLC-Triple TOF-MS coupled with UFLC-ESI-MS/MS. Food Chem.. 2022;384

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission (the first part), 2020. Chinese Pharmacopoeia. PRC. Chinese Medical Science and Techn, Beijing, pp. 75–76.

- A comprehensive strategy integrating metabolomics with multiple chemometric for discovery of function related active markers for assessment of foodstuffs: A case of hawthorn (Crataegus cuneata) fruits. Food Chem.. 2022;383:132464

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cimifugin suppresses NF-kappa B Signaling to prevent osteoclastogenesis and periprosthetic osteolysis. Front. Pharmacol.. 2021;12

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolomics investigation on antiobesity effects of Corydalis bungeana on high-fat high-sugar diet-induced obese rats. Chin. Herb. Med.. 2022;14:414-421.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- DNA mini-barcoding: A derived barcoding method for herbal molecular identification. Front. Plant Sci.. 2019;10:987.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Inspecting the true identity of herbal materials from Cynanchum using ITS2 barcode. Front. Plant Sci.. 2017;8

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Qualitative and quantitative evaluation of Flos Puerariae by using chemical fingerprint in combination with chemometrics method. J. Pharm. Anal.. 2022;12:489-499.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive profiling of Lingzhihuang capsule by liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry-based molecular networking and target prediction. Acupunct. Herb. Med.. 2022;2:58-67.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Protective effects of compounds from Cimicifuga dahurica against amyloid beta production in vitro and scopolamine-induced memory impairment in vivo. J. Nat. Prod.. 2020;83:223-230.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Triterpenoids from Cimicifugae rhizoma, a novel class of inhibitors on bone resorption and ovariectomy-induced bone loss. Maturitas. 2007;58:59-69.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Antibacterial actions of Ag nanoparticles synthesized from Cimicifuga dahurica (Turcz.) Maxim. and their application in constructing a hydrogel spray for healing skin wounds. Food Chem.. 2023;418:135981

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of chemical components of Periplocae Cortex and their metabolites in rats using ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Biomed. Chromatogr.. 2020;34

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Discovery of potential Q-marker of traditional Chinese medicine based on plant metabolomics and network pharmacology: Periplocae Cortex as an example. Phytomedicine. 2021;85

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Multimodal integrated strategy for the discovery and identification of quality markers in traditional Chinese medicine. J. Pharm. Anal.. 2022;12:701-710.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New phenylpropanoid allopyranosides from the rhizomes of Cimicifuga dahurica. ACS Med. Chem. Lett.. 2019;29:1774-1778.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- New monoterpene lactones from Actaea cimicifuga. Planta Med.. 2013;79:308-311.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of chemotypes and their markers in leaves of core collections of Eucommia ulmoides using metabolomics. Front. Plant Sci.. 2023;13

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Three new cycloart-7-ene triterpenoid glycosides from Cimicifuga dahurica and their anti-inflammatory effects. Nat. Prod. Res.. 2021;35:3634-3643.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Systematically identifying the anti-inflammatory constituents of Cimicifuga dahurica by UPLC-Q/TOF-MS combined with network pharmacology analysis. Biomed. Chromatogr.. 2021;35

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Polyphenolic compounds with antioxidant potential and neuro-protective effect from Cimicifuga dahurica (Turcz.) Maxim. Fitoterapia. 2016;115:52-56.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Anticomplement activity of cycloartane glycosides from the rhizome of Cimicifuga foetida. Phytother. Res.. 2006;20:945-948.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of antidepressant activity of Huang-Lian Jie-Du decoction through network pharmacology and metabolomics. Front. Pharmacol.. 2021;12

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Combining multidimensional chromatography-mass spectrometry and feature-based molecular networking methods for the systematic characterization of compounds in the supercritical fluid extract of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F. Analyst. 2023;148:61-73.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Identification of Cimicifugae Rhizoma and its adulterants using ITS2 sequence. China J. Chinese Mater. Med.. 2014;39:2184-2188.